Abstract

Background:

Best supportive care (BSC) as a control arm in clinical trials is poorly defined. We conducted a review to evaluate clinical trials' concordance with published, consensus-based framework for BSC delivery in trials.

Methods:

A consensus-based Delphi panel previously identified four key domains of BSC delivery in trials: multidisciplinary care; supportive care documentation; symptom assessment; and symptom management. We reviewed trials including BSC control arms from 2002 to 2014 to assess concordance to BSC standards and to selected items from the CONSORT 2010 guidelines.

Results:

Of 408 articles retrieved, we retained 18 after applying exclusion criteria. Overall, trials conformed to the CONSORT guidelines better than the BSC standards (28% vs 16%). One-third of articles offered a detailed description of BSC, 61% reported regular symptom assessment, and 44% reported using validated symptom assessment measures. One-third reported symptom assessment at identical intervals in both arms. None documented evidence-based symptom management. No studies reported educating patients about symptom management or goals of therapy. No studies reported offering access to palliative care specialists.

Conclusions:

Reporting of BSC in trials is incomplete, resulting in uncertain internal and external validity. Such studies risk systematically over-estimating the net clinical effect of the comparator arms.

Keywords: research design, health services research, randomized controlled trial, palliative care, symptom assessment

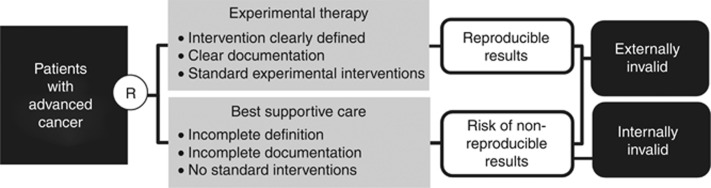

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for patients with advanced cancer often use a best supportive care (BSC) control arm, whereby patients randomized to this control arm receive supportive care exclusive of anti-neoplastic treatment (Macdonald, 1998; Cullen, 2001; Ahmed et al, 2004; Zafar et al, 2008; Cherny et al, 2009). However, supportive care interventions provided to patients in BSC control arms are often poorly described in protocols and manuscripts (Cullen, 2001; Cherny et al, 2009; Zafar et al, 2012). A prior systematic review found poor reporting of the components of the BSC arm and a lack of BSC standardization among trial participants (Cherny et al, 2009). As a result of this lack of rigor in defining and standardizing BSC, studies including BSC control arms may have problems with internal and external validity (Figure 1). These validity concerns may lead to biased outcomes or flawed conclusions.

Figure 1.

Poorly designed BSC can produce trial results that are internally and externally invalid.

A panel of international experts developed consensus-based standards for delivering BSC in clinical trials (Zafar et al, 2012). The authors of this framework described four key domains that should be included in BSC delivery: (1) multidisciplinary care; (2) documentation of supportive care; (3) symptom assessment at least as often as the intervention arm; and (4) guideline-based symptom management (Zafar et al, 2012). Thus, this framework is intended to guide standardization of BSC in clinical trials similar to the way other frameworks improve consistency of RCTs and their reporting. For example, study interventions are described with great detail in the protocol; the CONSORT statement outlines a consistent approach for documentation and reporting of patient eligibility criteria, study settings, intervention components, and generalizability of the trial findings (Schulz et al, 2010).

Although accepted standards for the delivery of BSC in RCTs exist, the literature has not described how well these standards reflect contemporary trial design. We conducted a review of the literature to determine whether the consensus-based framework for BSC delivery in RCTs reflects the design and documentation of recently published BSC RCTs.

Materials and methods

We searched the MEDLINE/PubMed database from 2002 to 2014 using the following search strings: ‘cancer' ‘best supportive care' ‘randomized' or ‘random allocation' and ‘supportive' or ‘palliative.' We used the following exclusion criteria: no BSC arm, non-human trial, not randomized, not English, not advanced cancer, or not including anti-cancer therapy.

We assessed each article for conformance to the consensus-based guidelines for BSC delivery by determining the presence or absence of the guideline criteria in the study publication (Table 1). Similarly, we evaluated each RCT's concordance to selected methodological items derived from the updated CONSORT 2010 guidelines for the reporting of RCTs. We selected relevant items from the CONSORT 2010 guidelines that most closely resemble the BSC domains. Two reviewers evaluated each article to determine how well the consensus-based frameworks were reflected in the documentation of BSC in each trial. Two additional reviewers resolved any discrepancies to ensure consensus agreement on each particular guideline.

Table 1. BSC and CONSORT domains assessed.

| BSC domains |

| Did the trial enroll patients across more than one site? |

| If yes, was the delivery of BSC standardized across all sites? |

| Was the delivery of supportive care within the clinical trial documented in a standardized manner for all patients on trial? |

| Does publication resulting from the trial offer a clear description of what best supportive care entailed? |

| Were symptoms are assessed at baseline and at regular intervals throughout trial participation? |

| Were symptoms assessed with concise, globally-accessible, validated tools? |

| Was symptom assessment undertaken at identical intervals in both arms? |

| Was symptom management conducted in concordance with evidence-based guidelines? |

| Were patients offered education specific to symptom management and assessment? |

| Were patients offered education specific to the goals of anti-cancer therapy? |

| Were patients offered access to palliative care specialists? |

| Did patients have access to other support services, including high-quality nursing, social work, financial counseling, and spiritual counseling? |

| Were patients educated on the goals of anti-cancer therapy, the importance of symptom assessment, and the role of symptom management within a clinical trial? |

| CONSORT domains |

| Does the study state eligibility criteria for patients? |

| Does the study document the settings and locations where the data were collected? |

| Are the interventions for each group described with sufficient details to allow replication, including how and when they were actually administered? |

| Does the trial provide adequate information for the results to be generalizable? |

Abbreviation: BSC=best supportive care.

Results

Search results

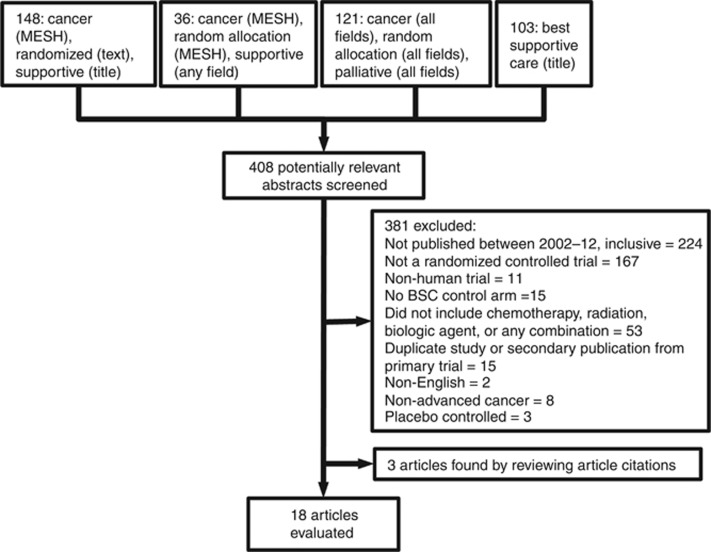

Of the 408 articles retrieved for potential review, we retained 18 after applying exclusion criteria (Figure 2). Most of the trials involved gastrointestinal (39% 7 out of 18) and lung (39% 7 out of 18) malignancies and most were phase III trials (78% 14 out of 18) (Table 2). The majority of trials used overall survival as their primary endpoint (72% 13 out of 18) and most concluded that their intervention showed an advantage over BSC (56% 10 out of 18).

Figure 2.

Literature review exclusion tree.

Table 2. Articles with BSC control arm.

| Study | Disease | Treatment added to SC | Phase of trial | Line of Therapy | Total no. of patients | No. who received intervention | No. who received BSC | Primary End Point | Outcome | Conformance to BSC | Conformance to CONSORT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Thuss-Patience et al, 2011 | Gastric | Irinotecan | III | Second | 40 | 21 | 19 | Survival | Advantage | 17% | 25% |

| 2 | Pelzer et al, 2011 | Pancreas | Oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-FU | III | Second | 46 | 23 | 23 | Survival | Advantage | 25% | 25% |

| 3 | Machiels et al, 2011 | H and N squamous | Zalutumumab | III | Second | 286 | 191 | 95 | Survival | No Advantage | 0% | 25% |

| 4 | Sharma et al, 2010 | Gallbladder | Fluorouracil or gemcitabine plus oxaliplatin | Does not state | Not specified | 81 | 54 | 27 | Survival | Advantage | 0% | 50% |

| 5 | Harousseau et al, 2009 | Acute Myeloid Leukemia | Tipifarnib | III | First | 457 | 228 | 229 | Survival | No Advantage | 0% | 25% |

| 6 | Ciuleanu et al, 2009 | Pancreas | Glufosfamide | III | Second | 303 | 148 | 155 | Survival | No Advantage | 17% | 25% |

| 7 | Bellmunt et al, 2009 | Bladder | Vinflunine | III | Second | 370 | 253 | 117 | Survival | Advantage | 25% | 25% |

| 8 | Jassem et al, 2008 | Malignant pleural mesothelioma | Pemetrexed | III | Second | 243 | 123 | 120 | Survival | No Advantage | 33% | 25% |

| 9 | Van Cutsem et al, 2007 | Colorectal | Panitumumab | III | Third or fourth | 463 | 231 | 232 | Progression-free survival | Advantage | 0% | 25% |

| 10 | O'Brien et al, 2006 | Small cell lung cancer | Topotecan | III | Second | 141 | 71 | 70 | Survival | Advantage | 33% | 25% |

| 11 | Brodowicz et al, 2006 | Non-small cell lung cancer | Gemcitabine | III | Maintenance after first line | 206 | 138 | 68 | Time to progression | Advantage | 17% | 25% |

| 12 | Spiro et al, 2004 | Non-small cell lung cancer | Cisplatin-based combination | Does not state | Not specified | 725 | 364 | 361 | Survival | Advantage | 17% | 25% |

| 13 | Muers et al, 2008 | Malignant pleural mesothelioma | Mitomycin, vinblastine, and cisplatin (MVP) or vinorelbine | Does not state | First | 409 | 273 | 136 | Survival | No Advantage | 25% | 25% |

| 14 | Jonker et al, 2007 | Colorectal | Cetuximab | III | Second and beyond | 572 | 287 | 285 | Survival | Advantage | 33% | 25% |

| 15 | Kang et al, 2012 | Gastric | Docetaxel or irinotecan | III | Second or Third | 202 | 133 | 69 | Survival | Advantage | 33% | 50% |

| 16 | Mubarak et al, 2012 | Non-small cell lung cancer | Pemetrexed | II | Maintenance after first line | 55 | 28 | 27 | Progression-free survival | No Advantage | 8% | 25% |

| 17 | Reichardt et al, 2012 | Gastrointestinal stromal tumors | Nilotinib | III | Third and beyond | 248 | 165 | 83 | Progression-free survival | No Advantage | 0% | 25% |

| 18 | Buikhuisen et al, 2013 | Malignant pleural or peritoneal mesothelioma | Thalidomide | III | Maintenance after first line | 221 | 111 | 110 | Time to progression | No Advantage | 0% | 25% |

Abbreviations: BSC=best supportive care; SC=supportive care.

Conformance to BSC Delphi standards

Overall, trials conformed to 16% of the BSC Delphi standards. Although most of the studies were multisite trials (94%), none of them reported standardized BSC across study sites (Table 3). Only one of the studies reported standardized delivery of BSC for the participants assigned to this arm (6%). The authors of this study discussed standardizing supportive care in their methods section under the intervention subheading (O'Brien et al, 2006).

Table 3. Clinical trial conformance to BSC statements and CONSORT guidelines.

| Domain assessed | Yes |

|---|---|

|

Conformance to BSC consensus standards in clinical trials | |

| Standardized BSC across sites if multisite | 0% |

| BSC delivery standardized | 6% |

| Clear description of BSC | 33% |

| Symptom assessment at regular intervals | 61% |

| Symptom assessment with valid tools | 44% |

| Symptom assessment identical both arms | 33% |

| Symptom management is evidence based | 0% |

| Reported educating patients about symptom management | 0% |

| Reported educating patients about goals of therapy | 0% |

| Provided access to palliative specialists | 0% |

| Provided access to support services | 11% |

| Education about goals, importance of symptom assessment/management | 0% |

|

Conformance to consort checklist for RCT's | |

| Eligibility criteria | 100% |

| Documentation of settings | 11% |

| Interventions described sufficiently | 0% |

| Generalizable results (must have met all three of the above CONSORT criteria) | 0% |

Abbreviations: BSC=best supportive care; RCT=randomized controlled trial.

Two-thirds of the articles did not provide a clear description of what BSC entailed for the patients on the BSC arm. For example, a common description of care provided in the BSC arm included details about the patients receiving structured physical, psychological, and social assessments with a clear explanation of symptom management (Muers et al, 2008). Most of the articles described symptom assessment at regular intervals (61%), but fewer reported the assessment of symptoms at identical intervals for both arms (33%), or used validated symptom assessment tools (44%). None of the articles described the use of evidence-based symptom management and none of the articles mentioned the provision of education to patients regarding how symptoms would be managed. Similarly, we found that none of the articles discussed educating patients about the importance of symptom assessment and management.

Furthermore, none of the articles reported offering education specific to the goals of the trial and the anti-cancer therapy. None of the articles mentioned that palliative care specialists were accessible to patients while receiving therapy. A minority of trials reported that patients in their study had access to support services that included social work, financial counseling, or spiritual counseling (11%).

Conformance to CONSORT

Overall, trials conformed to the selected CONSORT 2010 guidelines for trial reporting better than they did to the BSC standards (28% vs 16%). All of the articles reported eligibility criteria for patients on study. A minority of articles documented setting and locations of all trial sites (11%). None of the articles described interventions for each study arm with sufficient detail to allow replication. Similarly, none of the trials provided adequate information for the results to be generalizable.

Discussion

In our review of the cancer clinical trial literature, we found inconsistent reporting of supportive care provided to trial participants. In contrast to efforts to standardize intervention arms, our findings are consistent with prior studies (Ahmed et al, 2004; Cherny et al, 2009) demonstrating that RCTs poorly define and standardize BSC as a clinical trial control arm. A systematic review published in 2004 sought to examine the outcomes of RCTs that compared BSC vs chemotherapy in gastrointestinal cancer clinical trials (Ahmed et al, 2004). This review concluded that trial design and reporting needed improvements, and it highlighted the need for more clearly defined BSC as an RCT control arm (Ahmed et al, 2004). Similarly, a 2009 systematic review of the BSC literature called for improvements to the methodological and ethical validity of BSC studies (Cherny et al, 2009). In response, consensus-based recommendations for BSC delivery were published in 2012 which sought to improve the internal and external validity of BSC trials for patients with advanced cancer (Zafar et al, 2012).

Using the recently published consensus-based framework for the delivery of BSC in clinical trials, we aimed to determine how well this framework reflects reporting standards for recently published trials. Our current assessment of how well RCTs reflect these published BSC guidelines demonstrates potential avenues to improve the standardized delivery and documentation of supportive care in these trials. Most of the studies reported assessing patients' symptoms at regular intervals, but fewer reported using validated tools or standardizing these assessments across both arms. Furthermore, none of the articles discussed educating patients about the importance of symptom management, nor did they mention providing symptom management according to evidence-based standards. This lack of facilitation to access BSC, and poor standardization of symptom assessment and management in BSC trials merits attention, as BSC trials should deliver consistent, standardized supportive care according to published guidelines and evidence-based practice.

Standardization of supportive and palliative care in BSC trials is particularly important, as recent studies have found that patients with advanced cancer who receive palliative care experience improved quality of life, mood, and possibly even survival (Bakitas et al, 2009; Temel et al, 2010; El-Jawahri et al, 2011; Zimmermann et al, 2014). Access to palliative care should be provided early in the course of illness for patients with advanced cancer (Smith et al, 2012), especially those assigned to BSC in a clinical trial. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (Ferris et al, 2009) and the European Society of Medical Oncology (Cherny et al, 2003) both recommend the appropriate provision of supportive and palliative care services to patients with cancer. Our review of the BSC literature found that none of the recent trials document that patients had access to palliative care specialists. Additionally, these trials rarely report that patients had access to other support services, including nursing, social work, financial and spiritual counseling. Given that studies continue to show the benefits of providing optimal supportive care, BSC trials must aim to deliver care that complies with these accepted standards.

When BSC trials do not deliver standardized supportive care, researchers risk systematically over-estimating the net clinical effect of the comparator arms. This threat to internal validity calls into question the conclusions derived from the data. Notably, over half of the studies we analyzed found an advantage for the intervention arm compared with the BSC arm, but the use of substandard control arms may have inflated the effect sizes of the interventions. Furthermore, inconsistent reporting of the interventions received by the BSC control arm generates irreproducible data. Trial results that do not generalize to routine clinical practice lack external validity. Thus, in order for BSC trials to prove clinically meaningful results, researchers must provide consistent, evidence-based, and standardized BSC to all trial participants.

We recognize that all of the studies reviewed were published between 2002 and 2014. Thus, the study protocols were mostly written and implemented prior to the publication of the BSC Delphi recommendations. Hence, this current review serves as a ‘line in the sand' documenting the current state and heralding an opportunity for improvement. Monitoring uptake of the standardized BSC framework over time will be illustrative, as perhaps the impact of the consensus recommendations will reverberate more with future BSC studies.

Proper trial design does not allow for poorly defined interventions and variation between sites. Consequently, our results show that studies complied with the selected CONSORT guidelines better than they did with the BSC consensus guidelines. Previously, a literature review of oncology trial compliance to the CONSORT checklist has shown that compliance improved over time, with the most recently published studies showing better reporting (Rodrigues et al, 2011). Although the included articles in our current review were reported after the publication of the BSC consensus statements, we did not specifically aim to track compliance with those standards. Rather, we aimed to determine how well those standards reflected contemporary clinical trial design. Therefore, just as compliance to the CONSORT checklist has improved over time, we hope compliance to the published BSC standards will improve in future BSC trials. Meanwhile, researchers, review boards, medical editors, and their peer reviewers should ensure that BSC trials adhere to accepted BSC standards.

In conclusion, inconsistent reporting of supportive care in BSC trials persists. In light of the recently published BSC consensus guidelines, our literature review highlights the need to improve the standardized delivery and documentation of supportive care in BSC trials. Patients with advanced cancer enrolled on clinical trials expect care based on the best available evidence, but too often BSC studies fail to standardize BSC delivery across trial sites, lack evidence-based symptom management, and do not provide access to palliative or supportive care services. These problems with trial design threaten internal and external validity, resulting in biased outcomes and potentially flawed conclusions. Researchers can overcome these threats by integrating the published BSC standards into their BSC RCTs, and improving their subsequent documentation of the components of their BSC control arm. Future efforts to improve BSC trial design will need to determine the feasibility of implementing the current BSC standards, and continue to adapt subsequent recommendations according to the standard of care and in concordance with the best available evidence.

References

- Ahmed N, Ahmedzai S, Vora V, Hillam S, Paz S (2004) Supportive care for patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD003445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, Hull JG, Li Z, Tosteson TD, Byock IR, Ahles TA (2009) Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 302: 741–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellmunt J, Theodore C, Demkov T, Komyakov B, Sengelov L, Daugaard G, Caty A, Carles J, Jagiello-Gruszfeld A, Karyakin O, Delgado FM, Hurteloup P, Winquist E, Morsli N, Salhi Y, Culine S, Von der Maase H (2009) Phase III trial of vinflunine plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone after a platinum-containing regimen in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract. J Clin Oncol 27: 4454–4461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodowicz T, Krzakowski M, Zwitter M, Tzekova V, Ramlau R, Ghilezan N, Ciuleanu T, Cucevic B, Gyurkovits K, Ulsperger E, Jassem J, Grgic M, Saip P, Szilasi M, Wiltschke C, Wagnerova M, Oskina N, Soldatenkova V, Zielinski C, Wenczl M Central European Cooperative oncology group CECOG (2006) Cisplatin and gemcitabine first-line chemotherapy followed by maintenance gemcitabine or best supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III trial. Lung Cancer 52(2): 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buikhuisen WA, Burgers JA, Vincent AD, Korse CM, van Klaveren RJ, Schramel FM, Pavlakis N, Nowak AK, Custers FL, Schouwink JH, Gans SJ, Groen HJ, Strankinga WF, Baas P (2013) Thalidomide versus active supportive care for maintenance in patients with malignant mesothelioma after first-line chemotherapy (NVALT 5): an open-label, multicentre, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 14(6): 543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherny NI, Abernethy AP, Strasser F, Sapir R, Currow D, Zafar SY (2009) Improving the methodologic and ethical validity of best supportive care studies in oncology: lessons from a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 27: 5476–5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherny NI, Catane R, Kosmidis P ESMO Taskforce on Supportive & Palliative Care (2003) ESMO takes a stand on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol 14: 1335–1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciuleanu TE, Pavlovsky AV, Bodoky G, Garin AM, Langmuir VK, Kroll S, Tidmarsh GT (2009) A randomised Phase III trial of glufosfamide compared with best supportive care in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma previously treated with gemcitabine. Eur J Cancer 45(9): 1589–1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen M (2001) 'Best supportive care' has had its day. Lancet Oncol 2: 173–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS (2011) Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. J Support Oncol 9: 87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, Cummings C, Currow D, Dudgeon D, Janjan N, Strasser F, Von Gunten CF, Von Roenn JH (2009) Palliative cancer care a decade later: accomplishments, the need, next steps–from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 27: 3052–3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harousseau JL, Martinelli G, Jedrzejczak WW, Brandwein JM, Bordessoule D, Masszi T, Ossenkoppele GJ, Alexeeva JA, Beutel G, Maertens J, Vidriales MB, Dombret H, Thomas X, Burnett AK, Robak T, Khuageva NK, Golenkov AK, Tothova E, Mollgard L, Park YC, Bessems A, De Porre P, Howes AJ FIGHT-AML-301 Investigators (2009) A randomized phase 3 study of tipifarnib compared with best supportive care, including hydroxyurea, in the treatment of newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia in patients 70 years or older. Blood 114: 1166–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jassem J, Ramlau R, Santoro A, Schuette W, Chemaissani A, Hong S, Blatter J, Adachi S, Hanauske A, Manegold C (2008) Phase III trial of pemetrexed plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care in previously treated patients with advanced malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 26: 1698–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonker DJ, O'Callaghan CJ, Karapetis CS, Zalcberg JR, Tu D, Au HJ, Berry SR, Krahn M, Price T, Simes RJ, Tebbutt NC, van Hazel G, Wierzbicki R, Langer C, Moore MJ (2007) Cetuximab for the treatment of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 357(20): 2040–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim Do H, Park KW, Oh SY, Kwon HC, Hwang IG, Lee SC, Nam E, Shin DB, Lee J, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY, Kang WK, Park SH (2012) Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol 30: 1513–1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald N (1998) Best supportive care. Cancer Prev Control 2: 191–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machiels JP, Subramanian S, Ruzsa A, Repassy G, Lifirenko I, Flygare A, Sørensen P, Nielsen T, Lisby S, Clement PM (2011) Zalutumumab plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy: an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 12(4): 333–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mubarak N, Gaafar R, Shehata S, Hashem T, Abigeres D, Azim HA, El-Husseiny G, Al-Husaini H, Liu Z (2012) A randomized, phase 2 study comparing pemetrexed plus best supportive care versus best supportive care as maintenance therapy after first-line treatment with pemetrexed and cisplatin for advanced, non-squamous, non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer 12: 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muers MF, Stephens RJ, Fisher P, Darlison L, Higgs CM, Lowry E, Nicholson AG, O'brien M, Peake M, Rudd R, Snee M, Steele J, Girling DJ, Nankivell M, Pugh C, Parmar MK MS01 Trail Management Group (2008) Active symptom control with or without chemotherapy in the treatment of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma (MS01): a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 371: 1685–1694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien ME, Ciuleanu TE, Tsekov H, Shparyk Y, Cucevia B, Juhasz G, Thatcher N, Ross GA, Dane GC, Crofts T (2006) Phase III trial comparing supportive care alone with supportive care with oral topotecan in patients with relapsed small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 24: 5441–5447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelzer U, Schwaner I, Stieler J, Adler M, Seraphin J, Dörken B, Riess H, Oettle H (2011) Best supportive care (BSC) versus oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil (OFF) plus BSC in patients for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III-study from the German CONKO-study group. Eur J Cancer 47(11): 1676–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt P, Blay JY, Gelderblom H, Schlemmer M, Demetri GD, Bui-Nguyen B, Mcarthur GA, Yazji S, Hsu Y, Galetic I, Rutkowski P (2012) Phase III study of nilotinib versus best supportive care with or without a TKI in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors resistant to or intolerant of imatinib and sunitinib. Ann Oncol 23: 1680–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues G, Arra I, Velker V, Rotenberg B, Sexton T (2011) Two decades of oncology randomized controlled trials: factors associated with CONSORT clinical trial reporting checklist compliance. J Clin Oncol 29(Suppl): ): abstr 6126. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D GROUP, C. (2010) CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 152: 726–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Dwary AD, Mohanti BK, Deo SV, Pal S, Sreenivas V, Raina V, Shukla NK, Thulkar S, Garg P, Chaudhary SP (2010) Best supportive care compared with chemotherapy for unresectable gall bladder cancer: a randomized controlled study. J Clin Oncol 28: 4581–4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, Abernethy AP, Balboni TA, Basch EM, Ferrell BR, Loscalzo M, Meier DE, Paice JA, Peppercorn JM, Somerfield M, Stovall E, Von Roenn JH (2012) American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 30: 880–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro SG, Rudd RM, Souhami RL, Brown J, Fairlamb DJ, Gower NH, Maslove L, Milroy R, Napp V, Parmar MK, Peake MD, Stephens RJ, Thorpe H, Waller DA, West P Big Lung Trial participants (2004) Chemotherapy versus supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: improved survival without detriment to quality of life. Thorax 59(10): 828–836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ (2010) Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363: 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D, Deist T, Hinke A, Breithaupt K, Dogan Y, Gebauer B, Schumacher G, Reichardt P (2011) Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer—a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Eur J Cancer 47(15): 2306–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Cutsem E, Peeters M, Siena S, Humblet Y, Hendlisz A, Neyns B, Canon JL, Van Laethem JL, Maurel J, Richardson G, Wolf M, Amado RG (2007) Open-label phase III trial of panitumumab plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone in patients with chemotherapy-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 25: 1658–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafar SY, Currow D, Abernethy AP (2008) Defining best supportive care. J Clin Oncol 26: 5139–5140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafar SY, Currow DC, Cherny N, Strasser F, Fowler R, Abernethy AP (2012) Consensus-based standards for best supportive care in clinical trials in advanced cancer. Lancet Oncol 13: e77–e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, Moore M, Rydall A, Rodin G, Tannock I, Donner A, Lo C (2014) Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 383: 1721–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]