Abstract

Background:

This analysis compared the quality-adjusted survival and clinical outcomes of albumin-bound paclitaxel+carboplatin (nab-PC) vs solvent-based paclitaxel+carboplatin (sb-PC) as first-line therapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in older patients.

Methods:

Using age-based subgroup data from a randomised Phase-3 clinical trial, nab-PC and sb-PC were compared with respect to overall response rate (ORR), overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), quality of life (QoL), safety/toxicity, and quality-adjusted time without symptoms or toxicity (Q-TWiST) with ages ⩾60 and ⩾70 years as cut points.

Results:

Among patients aged ⩾60 years (N=546), nab-PC (N=265) significantly increased ORR and prolonged OS, despite a non-significant improvement in PFS, vs sb-PC (N=281). Nab-PC improved QoL and was associated with less neuropathy, arthralgia, and myalgia but resulted in more anaemia and thrombocytopenia. Nab-PC yielded significant Q-TWiST benefits (11.1 vs 9.8 months; 95% CI of gain: 0.2–2.6), with a relative Q-TWiST gain of 10.8% (ranging from 6.4% to 15.1% in threshold analysis). In the ⩾70 years age group, nab-PC showed similar, but non-significant, ORR, PFS, and Q-TWiST benefits and significantly improved OS and QoL.

Conclusion:

Nab-PC as first-line therapy in older patients with advanced NSCLC increased ORR, OS, and QoL and resulted in quality-adjusted survival gains compared with standard sb-PC.

Keywords: albumin-bound (nab) paclitaxel, solvent-based paclitaxel, non-small-cell lung cancer, quality-adjusted survival, Q-TWiST

Non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 85% of all lung cancer cases and typically presents at advanced stage (Molina et al, 2008). First-line therapy for patients with advanced stage generally consists of platinum-based doublet chemotherapy, that is, carboplatin or cisplatin in combination with a third-generation agent such as paclitaxel, albumin-bound -paclitaxel, docetaxel, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, or pemetrexed (Ettinger et al, 2012; Peters et al, 2012; Socinski et al, 2013a). Although older patients account for a majority of patients, they are often undertreated with standard chemotherapy regimens, largely due to a perception of poorer performance status, comorbidities, and anticipated intolerance to toxicity from platinum-based chemotherapy (Hardy et al, 2009; Davidoff et al, 2010; Langer, 2011). In addition, few studies have assessed treatment effects on quality of life (QoL) in elderly advanced NSCLC patients, and research on tolerability and toxicity profiles of chemotherapies in this population is similarly limited (Jang et al, 2009; Wildiers et al, 2013). Evidence, however, exists to show that platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is preferable to single-agent therapy for elderly, advanced NSCLC patients with good performance status who are likely to tolerate such therapy (Quoix et al, 2011; Qi et al, 2012).

Albumin-bound paclitaxel (nab-paclitaxel (nab-P), Celgene, Summit, NJ, USA) was initially developed to improve the clinical activity and tolerability profile of solvent-based paclitaxel (sb-P) as well as delivery of paclitaxel to tumours. Nab-paclitaxel has been shown to be active and tolerable as a single agent (Rizvi et al, 2008) and in combination with carboplatin (Socinski et al, 2010, 2012) for the treatment of advanced NSCLC. A phase III clinical trial compared nab-paclitaxel/carboplatin (i.e., nab-PC) with solvent-based (sb) paclitaxel (Taxol, Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY, USA) plus carboplatin (i.e., sb-PC) as first-line therapy for advanced NSCLC (Socinski et al, 2012). Nab-PC treatment resulted in a significantly higher overall response rate (ORR) (33% vs 25%, P=0.005), the primary end point of the study, vs sb-PC (Socinski et al, 2012). Among elderly patients (age ⩾70 years), nab-PC treatment significantly improved overall survival (OS) with trends towards improved ORR and progression-free survival (PFS) and was associated with significantly lower rates of neutropenia, neuropathy, and arthralgia (Socinski et al, 2013b) but higher rates of anaemia and thrombocytopenia. In addition, grade ⩾3 sensory neuropathy resolved more quickly in the nab-PC vs the sb-PC arms (Socinski et al, 2013b). This suggests that, among elderly NSCLC patients, nab-PC as first-line therapy is well tolerated and is associated with improved ORR, PFS, and significantly prolonged OS compared with sb-PC. However, these data on survival and AEs in the elderly did not take into account duration of all clinically significant AEs or AE effects on QoL. It is unclear whether this apparent survival benefit in older patients for nab-PC extends to QoL or whether trade-offs exist between survival and QoL.

Recognising the need for a comprehensive benefit vs risk assessment of nab-PC in elderly patients with advanced NSCLC, this analysis examined quality-adjusted time without symptoms or toxicity (Q-TWiST) using data collected from the aforementioned phase III clinical trial (Socinski et al, 2012). The Q-TWiST is a simultaneous assessment of time without toxicity or disease progression, which essentially examines the trade-off between AEs and treatment benefits (Goldhirsch et al, 1989). As part of a prespecified exploratory analysis, clinical outcomes for the trial subgroup ⩾60 years (not previously published) are reported herein.

Materials and Methods

Data source

Data for this analysis were collected in an open-label phase III randomised clinical trial comparing nab-PC to sb-PC as first-line therapy in adult patients with advanced NSCLC (CA031; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00540514) (Socinski et al, 2012). Patients were randomised (1 : 1) to a combination of nab-paclitaxel (100 mg m−2) and carboplatin (nab-PC) or sb-paclitaxel (200 mg m−2) and carboplatin (sb-PC). Enrollment required nonresectable stage IIIB or IV NSCLC measurable by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumour (RECIST), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1, and a life expectancy of >12 weeks. Although prior adjuvant chemotherapy was permitted if completed ⩾12 months prior to enrollment, patients who received previous treatments for metastatic disease or radiotherapy within 4 weeks of enrollment were excluded. Untreated or symptomatic brain metastasis, preexisting neuropathy grade >1 (per National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for AEs (NCI-CTCAE) v3.0) (Trotti et al, 2003), and history of allergy or hypersensitivity to the study drugs were key exclusion criteria (Socinski et al, 2012).

The primary clinical trial efficacy end point was ORR according to RECIST (Therasse et al, 2000), defined as the rate of objective-confirmed complete responses and/or partial responses determined by independent, blinded, centralised radiological review. Key secondary efficacy end points included PFS determined by independent review and OS. Survival was assessed for 18 months posttreatment, and tumour imaging was performed every 6 weeks until disease progression. Safety end points included the incidence of treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) (graded according to NCI-CTCAE v3.0). The taxane subscale of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Taxane (FACT-Taxane) questionnaire (Cella et al, 2003) was completed at baseline, on day 1 of each treatment cycle, and at the end of study treatment visit to assess QoL. The FACT-Taxane subscores for peripheral neuropathy, neuropathic pain in the hands and feet, hearing loss, and oedema were calculated as previously reported (Cella et al, 2003; Hirsh et al, 2014). Additional details, including a more comprehensive description of efficacy/safety assessments and FACT-Taxane (QoL) analysis, have been reported in previous publications (Socinski et al, 2012, 2013b).

The current analysis focused on the older patient population in the Phase III trial, for which assessment of both age ⩾60 and ⩾70 years subgroups were conducted. The stratification factors of randomisation included age (<70 vs ⩾70 years), and the evaluation of age effect, with 70 years as cutoff, has been reported previously (Socinski et al, 2013b) as one of the prespecified subgroup analysis. The analysis of patients aged ⩾60 years is relevant since 60 years was the median age of the trial population, and this population was included as one of the prespecified exploratory analyses. The clinical outcomes of the ⩾60-year-old population have not been reported previously. In addition, supplemental analyses were conducted for the younger populations, including subgroups aged <60, 60–69, and <70 years.

Analysis

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population (all randomised patients regardless of whether the patient received any study drug or had any efficacy assessments collected) was used in all the analyses, except for the safety and FACT-Taxane analysis, which evaluated only those who received at least one dose of the study drug (treated population).

For ORR, chi-square test was used to compare the treatment difference and relative response ratio was calculated. PFS and OS were estimated using Kaplan–Meier approach, with difference between the groups tested using stratified log-rank test, stratified by geographic region and histology. Cox proportional hazards model were calculated to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) while adjusting for the stratification factors. For safety evaluation, Fisher's exact test and Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel test were used to compare the TRAEs between treatments in the older patient population (treated population). Mean change from baseline scores of the FACT-Taxane were compared between treatments using two-sample t test by visit or repeated measurement across all visits.

The Q-TWiST method was used to combine measures of survival interval and QoL to estimate and compare the overall effects of nab-PC vs sb-PC (Goldhirsch et al, 1989) in terms of quality-adjusted survival. The area under OS curves was partitioned into periods of three distinct health states: (1) time with toxicity (TOX), that is, the period with clinically reported grade ⩾3 AEs after randomisation and before disease progression or censoring for progression (of note, non-clinically reported abnormal laboratory values for haemoglobin, neutrophil, and platelet count were assumed to be asymptomatic and not to affect patient's health-related QoL); (2) time without symptoms of progression or toxicity (TWiST); and (3) relapse time after progression (REL), that is, the period following disease progression and ending with death or censoring at the end of follow-up.

The Q-TWiST analysis used the standard approach and made the following assumptions (Goldhirsch et al, 1989; Gelber et al, 1993): (1) the four health states (TOX, TWiST, REL, and death) are distinct; (2) each health state is associated with a utility that does not vary over time (utility independence); (3) the utility associated with TOX was the same regardless of the type or severity of the AEs (with grade ⩾3); (4) there is a natural progression from TOX/TWiST to REL then death, allowing for transition from TOX/TWiST directly to death directly without going through disease progression; (5) AE duration was truncated when the disease progressed even if the AE continued after disease progression; and (6) patients could switch between TOX and TWiST, but all TOX time was grouped and modeled together at the beginning of therapy, regardless of when the TOX prior to REL actually occurred (the time spent with AEs grade ⩾3 were summed for every patient, of which the days with multiple AEs only counted once).

Kaplan–Meier method was used to graph the partitioned survival plots, which include the transitional survival curves for TOX, PFS, and OS. Although the cumulative area under a Kaplan–Meier survival curve represented the mean time of the responding health state, the mean duration of TWiST was calculated as the difference in area under PFS and TOX curves, and the mean duration of REL was calculated as the difference in area under OS and PFS curves. Q-TWiST values were calculated by multiplying times spent in each health state by their respective utility weights and then summing up to estimate the quality-adjusted survival (Q-TWiST=UTWiST × TWiST+UTOX × TOX+UREL × REL). Consistent with other Q-TWiST studies (Gelber et al, 1993; Sherrill et al, 2011; Corey-Lisle et al, 2012), the utility of TWiST was set as 1, while utilities for TOX and REL were set as 0.5 in the base case and were varied from 0 to 1 in a threshold utility analysis. Nonparametric bootstrap 95 percentile confidence intervals (95% CI) were derived to assess the statistical significance of treatment differences in TOX, TWiST, REL, and Q-TWiST. The percentage of improvement in Q-TWiST for nab-PC was calculated as the gain in Q-TWiST divided by mean OS time in the sb-PC group. A relative gain in Q-TWiST of ⩾10% was defined as clinically important (Revicki et al, 2006).

Total survival time up to 24 months of follow-up was used in the primary Q-TWiST analysis, with different cutoffs of follow-up length examined in the sensitivity analysis. The 24-month period was chosen because little information existed for the nab-PC group after 24 months—the longest observed duration of PFS was 24 months in patients receiving nab-PC, and most of the nab-PC patients who survived ⩾24 months were lost to follow-up thereafter for their OS outcome.

Although the base case scenario and threshold utility analysis both assumed the UTWiST to be 1.0, different utility values have been reported for advanced NSCLC patients with or without disease progression and toxicity (Nafees et al, 2008; Chouaid et al, 2013). To understand how the utility weight of TWiST affects the results, a sensitivity analysis was conducted wherein previously reported utility values of 0.71 for TWiST, 0.67 for REL, and 0.65 for TOX were used.

Results

Patients

The CA031 pivotal Phase III ITT population included 1052 patients (nab-PC: n=521, sb-PC: n=531). A total of 51.9% (n=546) of the ITT population were ⩾60 years: 265 were randomised to nab-PC and 281 to sb-PC (Table 1). Among these patients, 261 and 276 received at ⩾1 dose of nab-PC and sb-PC treatment, respectively. The majority of patients were ⩾60 years, male (71%), Caucasian (73%), with a past history of cigarette smoking (73%), baseline ECOG performance status of 1 (74%), and stage IV disease at randomisation (82%). Fifty-five percent of the patients were from Eastern Europe, 22% from North America, 21% from Asia, and 2% from Australia. Adenocarcinoma was the most common histology (51%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (40%), and large cell carcinoma or other. Fewer than 9% and 4% of patients received radiation therapy and chemotherapy, respectively, before randomisation. The baseline characteristics were balanced between treatment arms (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline demographics and characteristics in advanced NSCLC patients with ages ⩾60 and ⩾70 years.

|

Age ⩾60 years |

Age ⩾70 years |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nab-PC (N=265) | sb-PC (N=281) | P-valuea | nab-PC (N=74) | sb-PC (N=82) | P-valuea | |

| Age (years) | 0.47 | 0.63 | ||||

| Mean (s.d.) | 66.6 (5.0) | 66.9 (4.8) | 73.0 (3.0) | 72.8 (3.0) | ||

| Median (Min, Max) | 66 (60, 8) | 67 (60, 84) | 72 (70, 81) | 72 (70, 84) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | 0.55 | 0.62 | ||||

| Male | 192 (72.5) | 197 (70.1) | 55 (74.3) | 58 (70.7) | ||

| Race, n (%) | 0.50b | 0.25b | ||||

| Asian | 64 (24.2) | 57 (20.3) | 15 (20.3) | 18 (22.0) | ||

| Black, of African Heritage | 8 (3.0) | 5 (1.8) | 5 (6.8) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Caucasian | 187 (70.6) | 213 (75.8) | 50 (67.6) | 61 (74.4) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 (1.5) | 3 (1.1) | 3 (4.1) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| North American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Smoking status, n (%)c | 0.61 | 0.51 | ||||

| Never smoked | 68 (25.7) | 79 (28.5) | 18 (24.3) | 25 (31.3) | ||

| Smoked and quit smoking | 108 (40.8) | 102 (36.8) | 35 (47.3) | 31 (38.8) | ||

| Smoked and currently smokes | 89 (33.6) | 96 (34.7) | 21 (28.4) | 24 (30.0) | ||

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | 0.28b | 0.78b | ||||

| 0 (Fully active) | 74 (27.9) | 66 (23.5) | 21 (28.4) | 20 (24.4) | ||

| 1 (Restrictive but ambulatory) | 191 (72.1) | 214 (76.2) | 53 (71.6) | 61 (74.4) | ||

| 2 (Ambulatory but unable to work) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Region, n (%) | 0.30b | 0.73b | ||||

| North America | 62 (23.4) | 59 (21.0) | 28 (37.8) | 26 (31.7) | ||

| Eastern Europe | 138 (52.1) | 162 (57.7) | 30 (40.5) | 37 (45.1) | ||

| Asia/Pacific | 62 (23.4) | 53 (18.9) | 15 (20.3) | 16 (19.5) | ||

| Australia/New Zealand | 3 (1.13) | 7 (2.5) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (3.7) | ||

| Stage at randomisation, n (%) | 0.75 | 0.73 | ||||

| IIIb | 48 (18.1) | 48 (17.1) | 12 (16.2) | 15 (18.3) | ||

| IV | 217 (81.9) | 233 (82.9) | 62 (83.8) | 67 (81.7) | ||

| Histology of primary diagnosis, n (%) | 0.97b | 0.25b | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 135 (50.9) | 145 (51.6) | 33 (44.6) | 43 (52.4) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 106 (40.0) | 110 (39.2) | 35 (47.3) | 30 (36.6) | ||

| Large cell carcinoma | 5 (1.9) | 7 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.7) | ||

| Other | 19 (7.2) | 19 (6.8) | 6 (8.1) | 6 (7.3) | ||

|

Prior therapy,

n

(%) | ||||||

| Radiation therapy | 22 (8.3) | 25 (8.9) | 0.80 | 8 (10.8) | 6 (7.3) | 0.58b |

| Chemotherapy | 10 (3.8) | 9 (3.2) | 0.82b | 5 (6.8) | 3 (3.7) | 0.48b |

Abbreviations: ECOG=Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; nab-PC=nab-paclitaxel+carboplatin; NSCLC=non-small-cell lung cancer; sb-PC=solvent-based paclitaxel+carboplatin.

P-values were based on t-test for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables (for the stratified groups).

Using Fisher's exact test.

Included a few missing values.

Fifteen percent (156 out of 1052) of the ITT patients were ⩾70 years, with 74 and 82 randomised to nab-PC and sb-PC, respectively (Table 1). Baseline characteristics were similar between both arms in this population, except for a higher percentage of patients diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma in the nab-PC arm than in the sb-PC arm (47% vs 37%, P=0.25). In both the older age groups, >99% and >94% treated patients completed the FACT-Taxane questionnaire at baseline and at the end of study visit, respectively.

For the populations aged <60 years (n=506) and <70 years (n=896), the majority were male (79% and 75%), Caucasian (91% and 84%), with a smoking history (73% and 73%), and stage IV disease at randomisation (76% and 79%), respectively. Among patients aged 60–69 years (n=390), the majority were male (71%), Caucasian (75%), and with stage IV disease (82%). There were no significant difference in the baseline characteristics between treatments for younger populations aged <60, 60–69 and <70 years.

Treatment exposure

In total, 537 patients aged ⩾60 years (261 nab-PC, 276sb-PC) and 154 patients aged ⩾70 years (73 nab-PC, 81sb-PC) received at least one dose of chemotherapy in the study (treated population). Among the treated population with an age ⩾60 years, the median number of cycles administered was five and six in patients treated with nab-PC and sb-PC, respectively. The median cumulative paclitaxel dose was 1200 mg m−2 in the nab-PC arm and 1000 mg m−2 in the sb-PC arm (P<0.001), and the respective median dose intensities were 75.5 mg m−2 week−1 and 65.5 mg m−2 week−1 (P<0.001). Among the ⩾60-years population, 53% of the nab-PC patients and 25% of the sb-PC patients required a paclitaxel dose reduction (P<0.001). The median cumulative carboplatin dose was 2773 mg in the nab-PC arm and 2971.5 mg in the sb-PC arm, with the median dose intensity of 142.5 vs 188.4 mg week−1, respectively. A similar pattern of higher paclitaxel cumulative dose/dose intensity and lower carboplatin dose intensity in the nab-PC-treated arm were also observed in patients who were ⩾70 years.

Safety results

Among patients aged ⩾60 years, those treated with nab-PC experienced significantly less sensory neuropathy, arthralgia, and myalgia, whereas the rates of anaemia and thrombocytopenia were significantly higher than the sb-PC arm (Table 2). Similar trends were observed in patients aged ⩾70 years, except that the occurrence of myalgia was not significantly different between the two treatment arms, as previously reported (Socinski et al, 2013b).

Table 2. Treatment-emergent clinical reported adverse events (AEs) with grade ⩾3 (according to NCI CTCAE) in patients with ages ⩾60 and ⩾70 yearsa.

|

Age ⩾60 years |

Age ⩾70 years |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

nab-PC (N=261) |

sb-PC (N=276) |

nab-PC (N=73) |

sb-PC (N=81) |

|||||||||||

| AE, % | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | P-value | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 5 | P-value |

| All | 52.5 | 23.4 | 3.1 | 39.5 | 31.2 | 4.4 | 0.32 | 56.2 | 21.9 | 1.4 | 35.8 | 43.2 | 3.7 | 0.06 |

|

Haematological | ||||||||||||||

| Anaemia | 23.8 | 4.6 | 0 | 5.8 | 0 | 0 | <0.0001b | 28.8 | 1.4 | 0 | 9.9 | 0 | 0 | 0.0003b |

| Neutropenia | 34.9 | 16.5 | 0 | 26.1 | 29.0 | 0 | 0.63 | 39.7 | 13.7 | 0 | 21.0 | 42.0 | 0 | 0.21 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.76 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.18 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 14.9 | 2.7 | 0 | 6.2 | 1.1 | 0 | <0.0001b | 20.6 | 4.1 | 0 | 8.6 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.054 |

|

Non-haematological | ||||||||||||||

| Sensory neuropathy | 3.5 | 0 | 0 | 15.6 | 0.4 | 0 | <0.0001c | 6.9 | 0 | 0 | 22.2 | 1.2 | 0 | 0.001c |

| Fatigue | 8.8 | 0.4 | 0 | 9.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.10 | 6.9 | 0 | 0 | 17.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.15 |

| Anorexia | 3.5 | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.53 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.098 |

| Nausea | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0.19 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.84 |

| Arthralgia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | <0.0001c | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.042c |

| Myalgia | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 2.2 | 0 | 0 | 0.0009c | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0.73 |

Abbreviations: nab-PC=nab-paclitaxel+carboplatin; NCI-CTCAE=National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for AEs; sb-PC=solvent-based paclitaxel+carboplatin.

Only the AEs reported by the patients or health professionals were analysed; AEs defined simply based on laboratory data were not included.

Statistically significant in favour of sb-PC based on the Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel test for all grades.

Statistically significant in favour of nab-PC based on the Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel test for all grades.

In addition, in older patients aged ⩾60 or ⩾70 years receiving nab-PC, the rates of grade ⩾3 treatment-emergent AEs, especially neutropenia, significantly declined during later cycles of chemotherapy, whereas these remained high in patients treated with sb-PC. This is consistent with previous reports (Socinski et al, 2013b).

Efficacy results

In patients ⩾60 years, independent radiological assessment revealed a significantly higher ORR in the nab-PC arm, compared with sb-PC arm (34.0% vs 25.6%, P=0.03) (Table 3). The median PFS was 6.9 months (95% CI 5.6–8.0) in the nab-PC arm vs 5.7 months (95% CI 5.4–6.8) in the sb-PC arm (P=0.09, HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.65–1.03). The median OS was significantly improved in the patients treated with nab-PC, relative to sb-PC (13.8 vs 11.0 months, P=0.009, HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.62–0.94). In patients aged ⩾70 years, ORR and PFS were not significantly different between the treatments, although the trend for higher ORR and PFS in the nab-PC arm remained. The median OS benefit of nab-PC was more pronounced in patients aged ⩾70 years (19.9 vs 10.4 months, P=0.009, HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.39–0.88). Among patients aged <70 years, a significant difference favouring nab-PC was also observed in the overall response status (response rate ratio (RRR): 1.30, P=0.013). However, there was no significant difference between treatments in median PFS (6.0 vs 5.8 months, P=0.44) and median OS (11.4 vs 11.3 months, P=0.96) for this subgroup. No significant difference in ORR, median PFS, or median OS were found between treatments among patients aged <60 years (RRR: 1.30, P=0.068; median PFS: 5.7 vs 5.9 months, P=0.89; median OS: 10.6 vs 11.9 months, P=0.12) or patients aged 60–69 years (RRR: 1.30, P=0.089; median PFS: 6.1 vs 5.6 months, P=0.16; median OS: 12.6 vs 11.1 months, P=0.11).

Table 3. Overall response rate, PFS, and OS among patients with ages ⩾60 and ⩾70 years.

| nab-PC | sb-PC | Response rate ratio/hazard ratio (95% CI)a | P-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ⩾60 years | n=265 | n=281 | ||

| Patients with confirmed complete or partial overall response, n (%) | 90 (34.0) | 72 (25.6) | RRR=1.33 (1.02, 1.72) | 0.03 |

| 95% CIc | 28.3, 39.7 | 20.5, 30.7 | ||

| Complete response | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | ||

| Partial response | 90 (34.0) | 71 (25.3) | ||

| PFS, median months | 6.9 | 5.7 | HR 0.82 (0.65, 1.03) | 0.09 |

| 95% CI | 5.6, 8.0 | 5.4, 6.8 | ||

| OS, median months | 13.8 | 11.0 | HR 0.76 (0.62, 0.94) | 0.009 |

| 95% CI | 11.8, 16.8 | 9.6, 13.0 | ||

| Age ⩾70 years | n=74 | n=82 | ||

| Patients with confirmed complete or partial overall response, n (%) | 25 (33.8) | 20 (24.4) | RRR 1.39 (0.84, 2.28) | 0.20 |

| 95% CIc | 23.0, 44.6 | 15.1, 33.7 | ||

| Complete response | 0 (0) | 1 (1.2) | ||

| Partial response | 25 (33.8) | 19 (23.2) | ||

| PFS, median months | 8.0 | 6.8 | HR 0.69 (0.42, 1.12) | 0.13 |

| 95% CI | 6.0, 11.0 | 4.2, 9.5 | ||

| OS, median months | 19.9 | 10.4 | HR 0.58 (0.39, 0.88) | 0.009 |

| 95% CI | 11.8, 22.3 | 8.4, 13.6 |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; HR=hazard ratio; nab-PC=nab-paclitaxel+carboplatin; OS=overall survival; PFS=progression-free survival; RRR=response rate ratio; sb-PC=solvent-based paclitaxel+carboplatin.

The 95% CI for RRR was calculated according to the asymptotic 95% CI of the relative risk of nab-PC to sb-PC; HR<1 and RRR>1 favour nab-PC.

P-values were based on chi-square test for overall response rate and stratified log-rank test for PFS and OS.

95% CI of response rate (of complete or partial overall response).

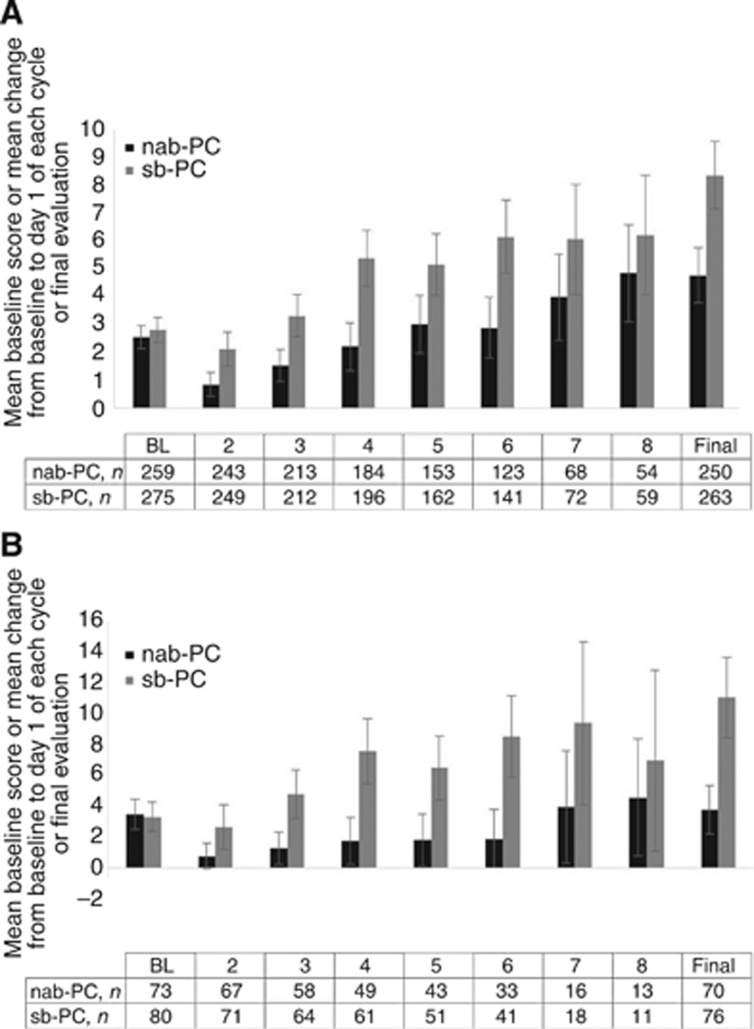

In older patients aged ⩾60 or ⩾70 years, there was a significant difference favouring nab-PC over sb-PC in the total score of FACT-Taxane (all 16 items, Figure 1, P<0.001) patient-reported QoL questionnaire over the entire course of treatment, as well as in the subscores of neuropathy, pain, and hearing loss. The oedema subscore change over the course of treatment did not differ significantly between nab-PC and sb-PC.

Figure 1.

Composite change from baseline for the 16-item FACT-Taxane. Symptoms were reported prior to dosing on day 1 of each cycle. Note that larger bars represent greater deteriorations from baseline as perceived by patients. Composite change (A) in patients aged ⩾60 years and (B) in patients aged ⩾70 years. BL, baseline; nab-PC, nab-paclitaxel+carboplatin; sb-PC, solvent-based paclitaxel+carboplatin.

It was found that within all three young populations, nab-PC-treated patients experienced better total FACT-Taxane score (lower score) compared with sb-PC at the final evaluation (age <60 years: 3.9 vs 5.6, P=0.014; age 60–69 years: 5.1 vs 7.2, P=0.021; age <70 years: 4.4 vs 6.4, P<0.001).

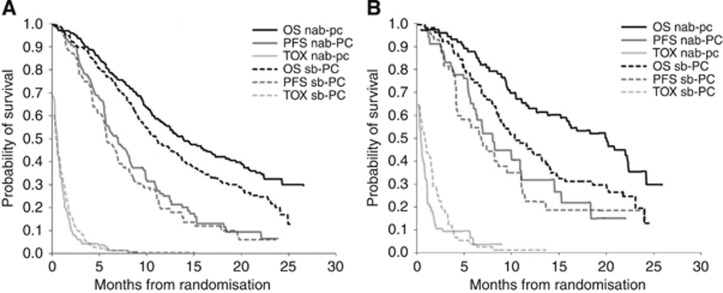

Q-TWiST

Figure 2 shows the partitioned survival curves for the nab-PC and sb-PC groups. The mean duration of OS using trial data was significantly prolonged in the nab-PC arm vs sb-PC arm (difference of 1.8 and 3.5 months in patients aged ⩾60 and ⩾70, respectively; Table 4). Although nab-PC resulted in a shorter duration of TOX and longer TWiST and REL durations, these differences were not statistically significant except for the longer REL in the nab-PC group among patients aged ⩾70 years (with difference of 3.4 months; 95% CI 0.6–6.2).

Figure 2.

Partitioned survival plots showing the mean times in TOX, TWiST, and REL states. The area under TOX curves represents the mean time in TOX state. The difference in area under PFS and TOX curves represent the mean time in TWiST state. The difference in area under OS and PFS curves represents the mean time in REL state. Partitioned survival plots (A) in patients aged ⩾60 years and (B) in patients aged ⩾70 years. nab-PC, nab-paclitaxel+carboplatin; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; sb-PC, solvent-based paclitaxel+carboplatin; TOX, toxicity with adverse event grade ⩾3.

Table 4. Duration of health states through 24 months.

| Survival time in months | nab-PC, mean time (95% CI) | sb-PC, mean time (95% CI) | Difference, mean time (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ⩾60 years | n=265 | n=281 | |

| TOX | 0.8 (0.7, 1.0) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | −0.1 (−0.4, 0.1) |

| TWiST | 7.7 (6.6, 8.7) | 6.8 (5.7, 7.6) | 1.0 (−0.4, 2.5) |

| REL | 6.0 (5.0, 7.1) | 5.0 (4.2, 6.1) | 1.0 (−0.5, 2.4) |

| PFS | 8.6 (7.4, 9.6) | 7.7 (6.6, 8.6) | 0.8 (−0.6, 2.4) |

| OS | 14.6 (13.5, 15.6) | 12.8 (11.8, 13.7) | 1.8 (0.4, 3.2) |

| Age ⩾70 years | n=74 | n=82 | |

| TOX | 0.9 (0.5, 1.2) | 1.4 (0.9, 1.9) | −0.5 (−1.2, 0.1) |

| TWiST | 8.3 (6.2, 10.1) | 7.7 (5.3, 9.8) | 0.6 (−2.3, 3.2) |

| REL | 6.8 (4.6, 9.1) | 3.3 (1.3, 5.4) | 3.4 (0.6, 6.2) |

| PFS | 9.2 (6.9, 11.0) | 9.2 (6.7, 11.4) | 0.0 (−2.9, 2.9) |

| OS | 16.0 (13.8, 17.6) | 12.5 (10.7, 14.1) | 3.5 (0.9, 5.7) |

| Age <60 years | n=256 | n=250 | |

| TOX | 0.6 (0.4, 0.7) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.7) | 0.0 (−0.2, 0.2) |

| TWiST | 6.8 (6, 7.6) | 7.1 (6.0, 8.1) | −0.2 (−1.6, 1.1) |

| REL | 4.7 (3.9, 5.6) | 5.4 (4.3, 6.4) | −0.7 (−2.0, 0.6) |

| PFS | 7.4 (6.5, 8.2) | 7.6 (6.5, 8.6) | −0.2 (−1.6, 1.2) |

| OS | 12.1 (11.1, 13) | 13.0 (11.9, 14) | −0.9 (−2.4, 0.5) |

| Age <70 years | n=447 | n=449 | |

| TOX | 0.7 (0.5, 0.8) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 0.0 (−0.1, 0.2) |

| TWiST | 7.2 (6.4, 7.9) | 6.8 (6.1, 7.4) | 0.4 (−0.6, 1.4) |

| REL | 5.1 (4.4, 5.9) | 5.5 (4.9, 6.2) | −0.4 (−1.4, 0.5) |

| PFS | 7.8 (7.0, 8.6) | 7.4 (6.7, 8.1) | 0.4 (−0.6, 1.4) |

| OS | 13.0 (12.2, 13.7) | 13.0 (12.2, 13.7) | 0.0 (−1.0, 1.1) |

| Age 60–69 years | n=191 | n=199 | |

| TOX | 0.8 (0.6, 0.9) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.8) | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.3) |

| TWiST | 7.3 (6.1, 8.4) | 6.3 (5.3, 7.1) | 1.0 (−0.4, 2.6) |

| REL | 5.9 (4.7, 7.2) | 5.8 (4.9, 6.9) | 0.0 (−1.6, 1.6) |

| PFS | 8.1 (6.8, 9.2) | 7.0 (6.0, 7.8) | 1.1 (−0.4, 2.6) |

| OS | 14.0 (12.7, 15.1) | 12.8 (11.6, 13.9) | 1.1 (−0.5, 2.7) |

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval; nab-PC=nab-paclitaxel+carboplatin; OS=overall survival; PFS=progression-free survival; REL=time to disease progression/relapse; sb-PC=solvent-based paclitaxel+carboplatin; TOX=time during toxicity; TWiST=time without symptoms of disease progression or toxicity of treatment. The values in bold indicate statistically significant differences between treatments in the corresponding end point.

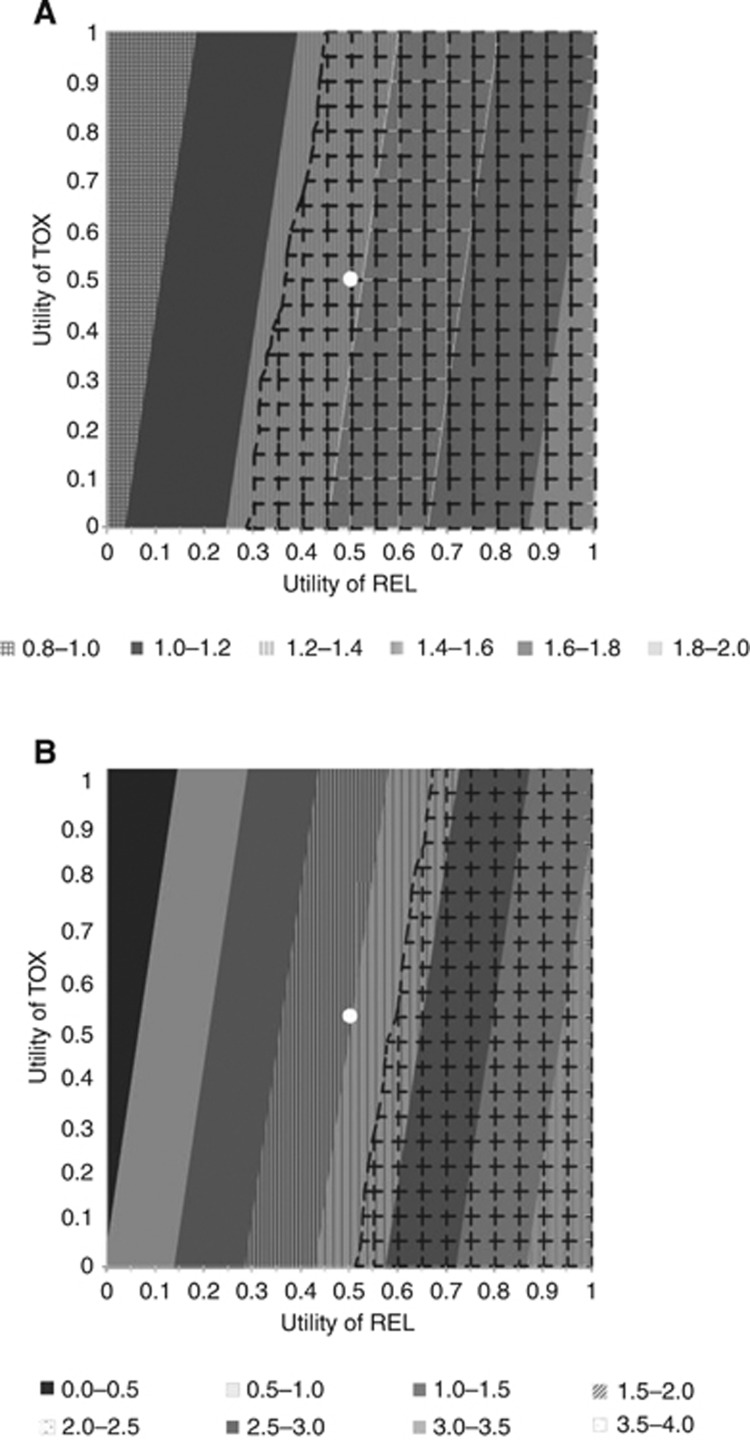

Among patients age ⩾60 years, in the base case when utility weights for the TOX and REL health states were both set equal to 0.5, nab-PC patients (vs sb-PC) experienced a significant mean Q-TWiST gain of 1.4 months (11.1 vs 9.8 months; 95% CI of difference: 0.2–2.6) (Figure 3). The percent gain in Q-TWiST (relative to the OS of sb-PC) was 10.8% and ranged from 6.4% to 15.1% across all possible utility weights for REL and TOX in the threshold utility analysis. In patients aged ⩾70 years, a trend toward Q-TWiST gain in favour of nab-PC was also found in the base case (mean difference 2.0 months), although the difference was not statistically significant (nab-PC 12.1 vs sb-PC 10.1 months; 95% CI of difference: −0.3, 4.3). The relative Q-TWiST gain was 16.2%, ranging from 0.3% to 32.1% in the threshold utility analysis. Figure 3 indicates the magnitude of absolute Q-TWiST gain, along with significance level, given different combinations of utility values for TOX and REL.

Figure 3.

Utility threshold plot through 24 months of follow-up. In these plots, the utility of TWiST was fixed at 1, and the utility for toxicity (UTOX) and utility for time after disease progression (UREL) both varied from 0 to 1. The base-case scenario (UTOX=UREL=0.5) was marked with a white dot. The diagonal bands of different shading indicate the magnitude of absolute Q-TWiST gain from nab-PC (vs sb-PC). The grid-shaded area indicates pairs of utility weights with statistically significant (P<0.05) Q-TWiST differences in favour of nab-PC. (A) Patients with an age ⩾60 years; (B) patients with an age ⩾70 years.

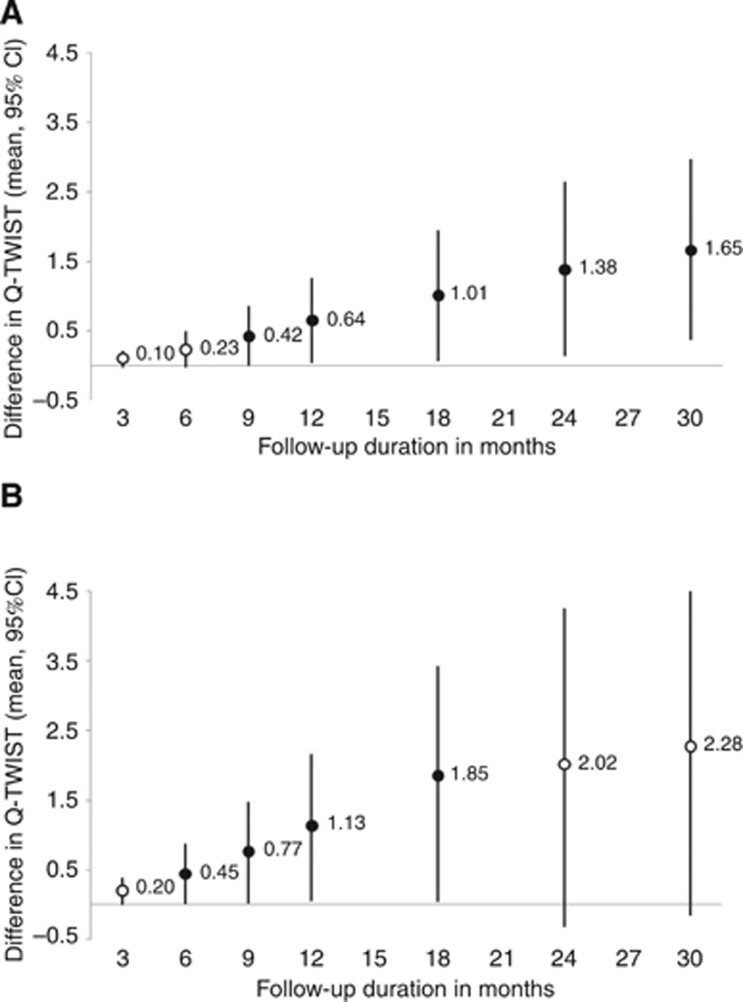

In sensitivity analyses varying the length of follow-up period (Figure 4), the observed Q-TWiST differences between treatment arms declined when patients were followed up at a shorter time point (as would be expected). However, in patients aged ⩾60 years, the Q-TWiST was significantly better for the nab-PC arm when a total follow-up period of ⩾9 months was considered (mean Q-TWiST difference at 9 months, 0.4 months, 95% CI: 0.02–0.8). Although the Q-TWiST gain for nab-PC was not statistically significant in patients aged ⩾70 years in the base case of 24-month follow-up, the mean difference in Q-TWiST was significant at shorter follow-ups, including 6, 9, 12, and 18 months.

Figure 4.

Differences in the Q-TWiST at various follow-up durations. Differences in the Q-TWiST (A) in patients aged ⩾60 years and (B) in patients aged ⩾70 years. Note: The solid circle sign represents significant difference in Q-TWiST (P<0.05) and the hollow circle sign represents non-significant difference in Q-TWiST.

In the sensitivity analyses where alternative utility weights were set as 0.71 for the TWiST state, 0.65 for TOX, and 0.67 for REL, nab-PC, relative to sb-PC, was associated with a significant mean Q-TWiST gain of 1.2 months (10.1 vs 8.8 months, 95% CI of difference: 0.3–2.2) and a relative gain of 9.7%. The Q-TWiST gain in this sensitivity analysis from nab-PC was also significant in patients aged ⩾70 years, with an absolute mean difference of 2.4 (95% CI: 0.6–3.9) and a relative gain of 18.9% as compared with sb-PC.

In the supplemental analysis of younger populations, no significant differences in the mean OS, PFS, and TWiST was found between treatments (Table 4). Nab-PC-treated patients (vs sb-PC) had no statistically significant differences in quality-adjusted survival time among populations aged <60 years (difference: −0.6 month (95% CI: −1.8, 0.7)), aged 60–69 years (difference: 1.1 months (95% CI: −0.2, 2.4)), and aged <70 years (difference: 0.2 month (95% CI: −0.7, 1.1)).

Discussion

This Q-TWiST analysis indicated that first-line therapy with nab-PC yielded longer quality-adjusted survival vs sb-PC in advanced NSCLC patients ⩾60 years and reflected proven benefits in ORR, OS, QoL, and AEs. The 1.4 quality-adjusted month benefit, representing a 10.8% relative gain, was statistically significant and clinically meaningful when TOX and REL utilities were both 0.5. The corresponding Q-TWiST difference among patients with an age ⩾70 (i.e., 2.0 months, +16.2%) also favoured nab-PC, albeit without statistical significance, perhaps due to smaller number of patients. Median OS gains of 2.8 months in patients aged ⩾60 years and 9.5 months in patients aged ⩾70 years correspond to relative improvements of 25% and 91%, respectively; however, the Q-TWiST benefits were less pronounced in the population aged ⩾70 years compared with ⩾60 years because the latter population had a greater difference in the mean duration of PFS (TOX+TWiST). The younger populations generally had non-significant differences in Q-TWiST compared with corresponding older populations.

Utilities used in the base case of the current analysis (TWiST (1.0), TOX (0.5), and REL (0.5)) were based on conventions reported in the Q-TWiST literature (Goldhirsch et al, 1989; Reni et al, 2014). Several studies have reported utility values for advanced NSCLC patients in different health states (Nafees et al, 2008; Chouaid et al, 2013). A prospective cross-sectional survey of advanced NSCLC patients in real-world treatment settings indicated that progression-free patients on first-line treatment had a mean utility of 0.71, and the mean utility was 0.67 for those on first-line therapy who had progressive disease (Chouaid et al, 2013). Another study elicited societal-based preferences among the general public in the United Kingdom for different disease stages and toxicity grades among metastatic NSCLC patients on second-line treatment (Nafees et al, 2008). In that study, various grade III–IV toxicities were associated with disutilities ranging from 0.03 to 0.09. Sensitivity analysis using alternative utility weights (0.71 for TWiST, 0.65 for TOX (0.71−0.06; with 0.06 as the mean disutility due to grade III–IV toxicities), 0.67 for REL) based on the aforementioned studies showed similarly favourable findings for nab-PC, supporting the robustness of the base case analysis.

Treatment options for elderly NSCLC patients are limited by anticipated toxicity (both perceived and real) and under-representation in clinical trials (Lichtman et al, 2007; Quoix, 2011). Poor performance status, higher risk of comorbidities, and concomitant medication use are additional factors predisposing these patients to toxic effects and drug interactions, which complicate disease management (Tas et al, 2013). Elderly lung cancer patients tend to experience similar or less favourable survival and tumour response rates to chemotherapy relative to younger patients (Tas et al, 2013), and thus the impact of nab-PC in improving OS, which was notable in the elderly, particularly those aged ⩾70 years, is encouraging. Although elderly patients may tolerate nab-PC as well as younger patients (Socinski et al, 2013b), associated toxicity remains an important consideration. The Q-TWiST approach applied herein incorporated toxicity, disease progression, and OS into a comprehensive framework to assess quality-adjusted survival benefits. To the best of the authors' knowledge, few studies have presented the quality-adjusted survival benefit of chemotherapy for NSCLC patients using Q-TWiST (Jang et al, 2009). Traditional oncological end points such as response rate and OS are limited in that they do not consider QoL, which is known to be important to patients. Q-TWiST is a robust means to bridge that gap.

Nab-PC treatment confers significant survival benefit and Q-TWiST gain compared with sb-PC among older NSCLC patients. It is possible that the improved toxicity profiles related to nab-PC regimen, including less grade 3–4 neuropathy, arthralgia, neuropathic pain, and hearing loss (Table 4), less neutropenia in later cycles of chemotherapy (Socinski et al, 2013b), and less total time in the TOX state allowed for higher paclitaxel total dose and dose intensity, which may have contributed to the survival advantage. In addition, older NSCLC patients on the nab-PC regimen were more likely to receive second-line therapy compared with those receiving sb-PC (Socinski et al, 2013b), perhaps because of performance status preservation owing to better disease control and improved tolerability with nab-PC treatment (Table 4). Second-line therapy, including erlotinib and docetaxel, has been shown to confer survival benefit over supportive care in NSCLC patients (Shepherd et al, 2000, 2005). The better survival and tolerability observed with the nab-PC regimen, compared with sb-PC, may also be attributed to the improved pharmacokinetic profile of albumin-bound paclitaxel particles, which is postulated to allow paclitaxel to reach tumour cells more efficiently and produce better antitumour activity (Sparreboom et al, 2005; Kratz, 2008; Chen et al, 2014). Cremophor, the solvent present in sb-PC, is known to cause neuropathy (Authier et al, 2000); the lack of cremophor in nab-PC alone, therefore, may have helped reduce the incidence of neuropathy. Finally, the weekly schedule of paclitaxel in the nab-PC regimen, compared with the episodic every 3-week paclitaxel schedule in the sb-PC regimen, may confer advantages in sustaining optimal dose intensity through dose adjustments, while refining toxicity monitoring and management, thus contributing to better tolerability. Theoretically, this advantage, if real, should translate into equally beneficial impact in all the age groups, which, however, was not observed (Socinski et al, 2013b). More research is needed to confirm the current findings.

The current analysis has several limitations. First, it is an exploratory subgroup analysis, albeit preplanned, utilising data from older patients in a trial with no age limit. Although elderly specific prospective studies are rare, subgroup analyses on elderly patients from age-unspecified trials may highlight the potential risk and benefits of treatments in this population (Jatoi et al, 2005). However, caution should be exercised when generalising the conclusions to all elderly patients as the elderly patients who participate in age-unspecified clinical trials could be in better health to satisfy inclusion criteria (Jatoi et al, 2005; Tas et al, 2013). Second, randomisation was stratified by age <70 vs ⩾70 years and other variables, which can enhance similarity of baseline prognostic factors between treatment arms (Dijkman et al, 2009). Thus the analysis of the ⩾70 years age group may have lower chance of type I and II errors than the analysis of ⩾60 years age group. Although the ⩾60 years age group was not intended to be stratified for randomisation, the sample size was larger in this subgroup, and the treatment arms were at least as balanced as the ⩾70 years age subgroup. Third, the Q-TWiST analysis assumed the utility weight for TOX to be the same regardless of AE type or severity. Although the approach may affect the accuracy measuring the impact of treatment toxicity, the threshold analysis helps to address the uncertainty by providing a range of estimates between the extreme cases. Finally, the Q-TWiST analysis was limited to a maximum follow-up duration of 24 months, because little information was provided for treatment comparison afterwards. Although more pronounced Q-TWiST differences between treatments could possibly be observed with a longer follow-up interval (as indicated in the sensitivity analyses), it is yet unknown how the benefits of nab-PC treatment could preserve, extend, or even recede after 2 years. Nevertheless, this limitation is expected to have a minimal impact on the conclusions as less than approximately 30% of patients on nab-PC and less than approximately 15% of sb-PC remained alive at 24 months. A prospective Phase IV, randomised, open-label, multicentre study in elderly advanced NSCLC patients (ABOUND.70+, NCT02151149) is currently ongoing to confirm the risk and benefits of nab-PC treatment seen in this analysis.

In conclusion, this analysis confirms the favourable benefit/risk of first-line nab-PC treatment in older population (patients aged ⩾60 or ⩾70 years) with good baseline performance status, including superiority in terms of OS, QoL, safety/toxicity, and Q-TWiST. A benefit in ORR for nab-PC treatment was also found in patients aged ⩾60 years.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Celgene Corporation. We thank John Carter for editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author contributions

F-JL, YW, SW, and MFB participated in the design of the analysis, data interpretation and manuscript writing. F-JL and YW conducted the data analysis. Other co-authors contributed in the data interpretation and manuscript revision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

CJL received honorarium/consulting fee and has served as an advisor for Celgene Corporation. VH is a consultant for Celgene Corporation. F-JL, YW, and MFB are employees, and MFB is also a shareholderof Pharmerit International, an independent contract research organisation that received research funding from Celgene Corporation. SW, TJO, and MFR are employees of Celgene Corporation. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Authier N, Gillet JP, Fialip J, Eschalier A, Coudore F (2000) Description of a short-term Taxol-induced nociceptive neuropathy in rats. Brain Res 887(2): 239–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Peterman A, Hudgens S, Webster K, Socinski MA (2003) Measuring the side effects of taxane therapy in oncology: the functional assesment of cancer therapy-taxane (FACT-taxane). Cancer 98(4): 822–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Li Y, Ye Y, Palmisano M, Chopra R, Zhou S (2014) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of nab-paclitaxel in patients with solid tumors: disposition kinetics and pharmacology distinct from solvent-based paclitaxel. J Clin Pharmacol 54(10): 1097–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouaid C, Agulnik J, Goker E, Herder GJ, Lester JF, Vansteenkiste J, Finnern HW, Lungershausen J, Eriksson J, Kim K, Mitchell PL (2013) Health-related quality of life and utility in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a prospective cross-sectional patient survey in a real-world setting. J Thorac Oncol 8(8): 997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey-Lisle PK, Peck R, Mukhopadhyay P, Orsini L, Safikhani S, Bell JA, Hortobagyi G, Roche H, Conte P, Revicki DA (2012) Q-TWiST analysis of ixabepilone in combination with capecitabine on quality of life in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer 118(2): 461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff AJ, Tang M, Seal B, Edelman MJ (2010) Chemotherapy and survival benefit in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 28(13): 2191–2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkman B, Kooistra B, Bhandari M Evidence-Based Surgery Working Group (2009) How to work with a subgroup analysis. Can J Surg 52(6): 515–522. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger DS, Akerley W, Borghaei H, Chang AC, Cheney RT, Chirieac LR, D'Amico TA, Demmy TL, Ganti AK, Govindan R, Grannis FW Jr., Horn L, Jahan TM, Jahanzeb M, Kessinger A, Komaki R, Kong FM, Kris MG, Krug LM, Lennes IT, Loo BW Jr., Martins R, O'Malley J, Osarogiagbon RU, Otterson GA, Patel JD, Pinder-Schenck MC, Pisters KM, Reckamp K, Riely GJ, Rohren E, Swanson SJ, Wood DE, Yang SC, Hughes M, Gregory KM Nccn (2012) Non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 10(10): 1236–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelber RD, Goldhirsch A, Cole BF (1993) Evaluation of effectiveness: Q-TWiST. The International Breast Cancer Study Group. Cancer Treat Rev 19(Suppl A): 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Simes RJ, Glasziou P, Coates AS (1989) Costs and benefits of adjuvant therapy in breast cancer: a quality-adjusted survival analysis. J Clin Oncol 7(1): 36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy D, Liu CC, Xia R, Cormier JN, Chan W, White A, Burau K, Du XL (2009) Racial disparities and treatment trends in a large cohort of elderly black and white patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer. Cancer 115(10): 2199–2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsh V, Okamoto I, Hon JK, Page RD, Orsini J, Sakai H, Zhang H, Renschler MF, Socinski MA (2014) Patient-reported neuropathy and taxane-associated symptoms in a phase 3 trial of nab-paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus solvent-based paclitaxel plus carboplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 9(1): 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang RW, Le Maitre A, Ding K, Winton T, Bezjak A, Seymour L, Shepherd FA, Leighl NB (2009) Quality-adjusted time without symptoms or toxicity analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: an analysis of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group JBR.10 trial. J Clin Oncol 27(26): 4268–4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jatoi A, Hillman S, Stella P, Green E, Adjei A, Nair S, Perez E, Amin B, Schild SE, Castillo R, Jett JR North Central Cancer Treatment Group (2005) Should elderly non-small-cell lung cancer patients be offered elderly-specific trials? Results of a pooled analysis from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. J Clin Oncol 23(36): 9113–9119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratz F (2008) Albumin as a drug carrier: design of prodrugs, drug conjugates and nanoparticles. J Control Release 132(3): 171–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer CJ (2011) Clinical evidence on the undertreatment of older and poor performance patients who have advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: is there a role for targeted therapy in these cohorts? Clin Lung Cancer 12(5): 272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman SM, Wildiers H, Chatelut E, Steer C, Budman D, Morrison VA, Tranchand B, Shapira I, Aapro M International Society of Geriatric Oncology Chemotherapy Taskforce (2007) International Society of Geriatric Oncology Chemotherapy Taskforce: evaluation of chemotherapy in older patients—an analysis of the medical literature. J Clin Oncol 25(14): 1832–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA (2008) Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc 83(5): 584–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nafees B, Stafford M, Gavriel S, Bhalla S, Watkins J (2008) Health state utilities for non small cell lung cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 6: 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters S, Adjei AA, Gridelli C, Reck M, Kerr K, Felip E Group EGW (2012) Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 23(Suppl 7): vii56–vii64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi WX, Tang LN, He AN, Shen Z, Lin F, Yao Y (2012) Doublet versus single cytotoxic agent as first-line treatment for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung 190(5): 477–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quoix E (2011) Optimal pharmacotherapeutic strategies for elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Drugs Aging 28(11): 885–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quoix E, Zalcman G, Oster JP, Westeel V, Pichon E, Lavole A, Dauba J, Debieuvre D, Souquet PJ, Bigay-Game L, Dansin E, Poudenx M, Molinier O, Vaylet F, Moro-Sibilot D, Herman D, Bennouna J, Tredaniel J, Ducolone A, Lebitasy MP, Baudrin L, Laporte S, Milleron B Intergroupe Francophone de Cancerologie Thoracique (2011) Carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel doublet chemotherapy compared with monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: IFCT-0501 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 378(9796): 1079–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reni M, Wan Y, Solem C, Whiting S, Ji X, Botteman M (2014) Quality-adjusted survival with combination nab-paclitaxel+gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone in metastatic pancreatic cancer: a Q-TWiST analysis. J Med Econ 17(5): 338–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revicki DA, Feeny D, Hunt TL, Cole BF (2006) Analyzing oncology clinical trial data using the Q-TWiST method: clinical importance and sources for health state preference data. Qual Life Res 15(3): 411–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi NA, Riely GJ, Azzoli CG, Miller VA, Ng KK, Fiore J, Chia G, Brower M, Heelan R, Hawkins MJ, Kris MG (2008) Phase I/II trial of weekly intravenous 130-nm albumin-bound paclitaxel as initial chemotherapy in patients with stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 26(4): 639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, Mattson K, Gralla R, O'Rourke M, Levitan N, Gressot L, Vincent M, Burkes R, Coughlin S, Kim Y, Berille J (2000) Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 18(10): 2095–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Campos D, Maoleekoonpiroj S, Smylie M, Martins R, van Kooten M, Dediu M, Findlay B, Tu D, Johnston D, Bezjak A, Clark G, Santabarbara P, Seymour L National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group (2005) Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 353(2): 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrill B, Sherif B, Amonkar MM, Maltzman J, O'Rourke L, Johnston S (2011) Quality-adjusted survival analysis of first-line treatment of hormone-receptor-positive HER2+ metastatic breast cancer with letrozole alone or in combination with lapatinib. Curr Med Res Opin 27(12): 2245–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socinski MA, Bondarenko I, Karaseva NA, Makhson AM, Vynnychenko I, Okamoto I, Hon JK, Hirsh V, Bhar P, Zhang H, Iglesias JL, Renschler MF (2012) Weekly nab-paclitaxel in combination with carboplatin versus solvent-based paclitaxel plus carboplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: final results of a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 30(17): 2055–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socinski MA, Evans T, Gettinger S, Hensing TA, Sequist LV, Ireland B, Stinchcombe TE (2013. a) Treatment of stage IV non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 143(5 Suppl): e341S–e3468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socinski MA, Langer CJ, Okamoto I, Hon JK, Hirsh V, Dakhil SR, Page RD, Orsini J, Zhang H, Renschler MF (2013. b) Safety and efficacy of weekly nab(R)-paclitaxel in combination with carboplatin as first-line therapy in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 24(2): 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Socinski MA, Manikhas GM, Stroyakovsky DL, Makhson AN, Cheporov SV, Orlov SV, Yablonsky PK, Bhar P, Iglesias J (2010) A dose finding study of weekly and every-3-week nab-Paclitaxel followed by carboplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 5(6): 852–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparreboom A, Scripture CD, Trieu V, Williams PJ, De T, Yang A, Beals B, Figg WD, Hawkins M, Desai N (2005) Comparative preclinical and clinical pharmacokinetics of a cremophor-free, nanoparticle albumin-bound paclitaxel (ABI-007) and paclitaxel formulated in Cremophor (Taxol). Clin Cancer Res 11(11): 4136–4143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tas F, Ciftci R, Kilic L, Karabulut S (2013) Age is a prognostic factor affecting survival in lung cancer patients. Oncol Lett 6(5): 1507–1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC, Gwyther SG (2000) New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst 92(3): 205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotti A, Colevas AD, Setser A, Rusch V, Jaques D, Budach V, Langer C, Murphy B, Cumberlin R, Coleman CN, Rubin P (2003) CTCAE v3.0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment. Semin Radiat Oncol 13(3): 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildiers H, Mauer M, Pallis A, Hurria A, Mohile SG, Luciani A, Curigliano G, Extermann M, Lichtman SM, Ballman K, Cohen HJ, Muss H, Wedding U (2013) End points and trial design in geriatric oncology research: a joint European organisation for research and treatment of cancer—Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology—International Society Of Geriatric Oncology position article. J Clin Oncol 31(29): 3711–3718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]