Abstract

Psychosocial factors among overweight, obese, and morbidly obese women in Delhi, India were examined. A follow-up survey was conducted of 325 ever-married women aged 20–54 years, systematically selected from 1998–99 National Family Health Survey samples, who were re-interviewed after 4 years in 2003. Information on day-to-day problems, body image dissatisfaction, sexual dissatisfaction, and stigma and discrimination were collected and anthropometric measurements were obtained from women to compute their current body mass index. Three out of four overweight women (BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2) were not happy with their body image, compared to four out of five obese women (BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater), and almost all (95 percent) morbidly obese women (BMI of 35 kg/m2 or greater) (p < .0001). It was found that morbidly obese and obese women were five times (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 5.29, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.02–13.81, p < .001) and two times (aOR 2.30, 95% CI 1.20–4.42, p < .001), respectively, as likely to report day-to-day problems; twelve times (aOR 11.88, 95% CI 2.62–53.87, p < .001) and three times, respectively, as likely (aOR 2.92, 95% CI 1.45–5.88, p = .001) to report dissatisfaction with body image; and nine times (aOR 9.41, 95% CI 2.96–29.94, p < .001) and three times (aOR 2.93, 95% CI 1.03–8.37, p = .001), respectively, as likely to report stigma and discrimination as overweight women.

KEYWORDS: follow-up, India, obesity, psychosocial factors, women

INTRODUCTION

Obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2) has been identified as a major public health challenge of the twenty-first century across the globe (WHO 2003). An estimated 205 million men and 297 million women over the age of 20 years were recently estimated to be obese—a total of more than half a billion adults worldwide (Finucane et al. 2011). Even in countries like India, which are typically known for a high prevalence of under nutrition, a significant proportion of overweight and obese people now coexists with those who are undernourished (Subramanian and Smith 2006). Most available recent data from India showed 12.6 percent of women were either overweight or obese, while a similar percentage of women were underweight and overweight or obese in urban India (25 percent underweight and 23.5 percent overweight or obese) (IIPS and Macro International 2007). In addition to several health-risk factors (Fabricatore and Wadden 2003; WHO 2009, 2010; Finucane et al. 2011), obesity may be related to several short-term problems, such as social discrimination and lower quality of life (Kushner and Foster 2000; Kolotkin, Meter, and Williams 2001; Puhl and Brownell 2001; Fabricatore and Wadden 2003; Jia and Lubetkin 2005; Puhl and Heuer 2010) among others. Persons with obesity have been found to have a significantly lower health-related quality of life than those who were normal weight, even for persons without chronic diseases known to be linked to obesity (Jia and Lubetkin 2005). Obesity has often been described as a major social prejudice (Sobal, 1991; Stunkard and Sobal 1995), with a significant social tendency to stigmatize overweight individuals (Muennig 2008). In light of the increases in obesity in India, it is worthwhile to examine the adverse psychosocial conditions associated with excess weight gain specifically among adult women in India who have experienced larger proportionate weight gain than men (IIPS & Macro International 2007).

Studies from developed countries have shown that obese individuals often face obstacles in society and in their day-to-day lives, far beyond health risks (Jia and Lubetkin 2005; van der Merwe 2007). Psychological suffering may be one of the most painful parts of obesity (Carr and Friedman 2005; Markowitz, Friedman, and Arent 2008). Young overweight and obese women are at particular risk for developing sustained depressive mood, which is an important gateway symptom for a major depressive disorder (van der Merwe 2007). Society often emphasizes the importance of physical appearance. As a result, people who are obese often face prejudice or discrimination in the job market, at school (Shin and Shin 2008), and in social situations (Stunkard and Sobal 1995; Nieman and LeBlanc 2012). The very few studies that have examined the psychological issues associated with obesity have been consistent in showing that those with a history of weight cycling have significantly more psychological problems, such as lower levels of satisfaction with life, and more eating disorder symptoms than those who are weight stable (Elfhag and Rössner 2005).

In western countries, obesity, particularly among women and children, is often associated with social prejudice and discrimination (Ali and Lindström 2005). Prejudices regarding obesity have also been experienced in some Asia-Pacific countries. However, in some regions, such as the Pacific Islands, obesity is still considered desirable and a symbol of wealth among those of higher social standing (Dowse et al. 1995). As the obesity rates in these countries continue to increase, these populations may become increasingly affected by cultural values more common in industrialised countries.

A further important risk factor for impaired psychological health is the degree of overweight. The problems of the severely or morbidly obese (BMI of 40+) have often been described in terms of stupidity, laziness, dishonesty, lack of ambition, lack of self-confidence or low self-esteem, and emotional complications (Owens 2003). A study by Carpenter et al. (2000) indicated that overweight women and underweight men were at higher risk of suicide. Further, obese women were 26 percent more likely to think about suicide and 55 percent more likely to have attempted suicide than women of average weight.

In view of the above discussion, in this study we aimed to describe the different psychosocial factors associated with overweight and obesity among women in Delhi, representing urban India, highlighting those aspects of the problem that are frequently overlooked in nutritional and medical research.

METHODS

Study Location and Population

The present article used data collected for the Doctoral dissertation by the first author (Agrawal 2004). Full details of the study methods have been published elsewhere (Agrawal 2004; Agrawal et al. 2013, 2014). Briefly, during May–June 2003, a follow-up survey was carried out in Delhi using the same sample derived for India’s second round of the National Family Health Survey-2 (NFHS-2) conducted during 1998–99. Delhi was chosen as the preferred location for this study because it represented a heterogeneous, multicultural urban population in India. NFHS-2 collected demographic, socio-economic, and health information from a nationally representative sample of 90,303 ever-married women aged 15–49 years in all states of India (except the union territories), which covers more than 99 percent of the country’s population with a response rate of 98 percent. Details of sample design, including sampling frame, are provided in the national survey report (IIPS & ORC Macro 2000).

From the 1998–99 NFHS-2 Delhi samples, 325 women aged 15–49 years were chosen by stratified systematic sampling (described below) and re-interviewed in a follow-up survey after 4 years in 2003. Because in the NFHS-2 only ever-married women were sampled and interviewed, we also restricted our samples to ever married women. Women’s weights and heights were recorded again in the follow-up study using the same equipment used in NFHS-2 to compute their current body mass index (BMI). In addition, detailed information was collected on their dietary habits, lifestyle behaviors, along with other socio-demographic characteristics using a face-to-face interview with a structured questionnaire. Self-reported information on women’s day-to-day problems, body image dissatisfaction, sexual dissatisfaction, stigma, and discrimination (collectively known as psychosocial factors), which were the main response variables in this study, were sought only from those women who were overweight and obese, after obtaining their current height and weight and computing their current BMI during the course of their anthropometric measurements. Thus, normal weight women were deterred from being interviewed about the psychosocial factors related to weight gain.

Sample Selection, Response Rate, and Sample Size

Earlier studies on obesity in India and other developing countries had shown that overweight and obesity were predominant in urban areas and among women (Gopinath et al. 1994; Agrawal & Mishra 2004; Agrawal, Mishra, and Agrawal 2012). Therefore, only urban primary sampling units (PSUs) were chosen for the follow-up survey in Delhi. The sample frame for the follow-up survey was fixed to include women from all BMI categories and literacy levels. The aim was to have a sample size of at least 300 women, 100 from each of the three BMI categories (normal, overweight, and obese). At the time of revisit, several issues, such as migration, change of address, non-response, and non-availability of respondents tended to reduce the sample size. Potential loss during follow-up (WHO 1995; Altman 2009) was dealt with by increasing the initial sample size (double than required) to obtain the desired sample size for the study.

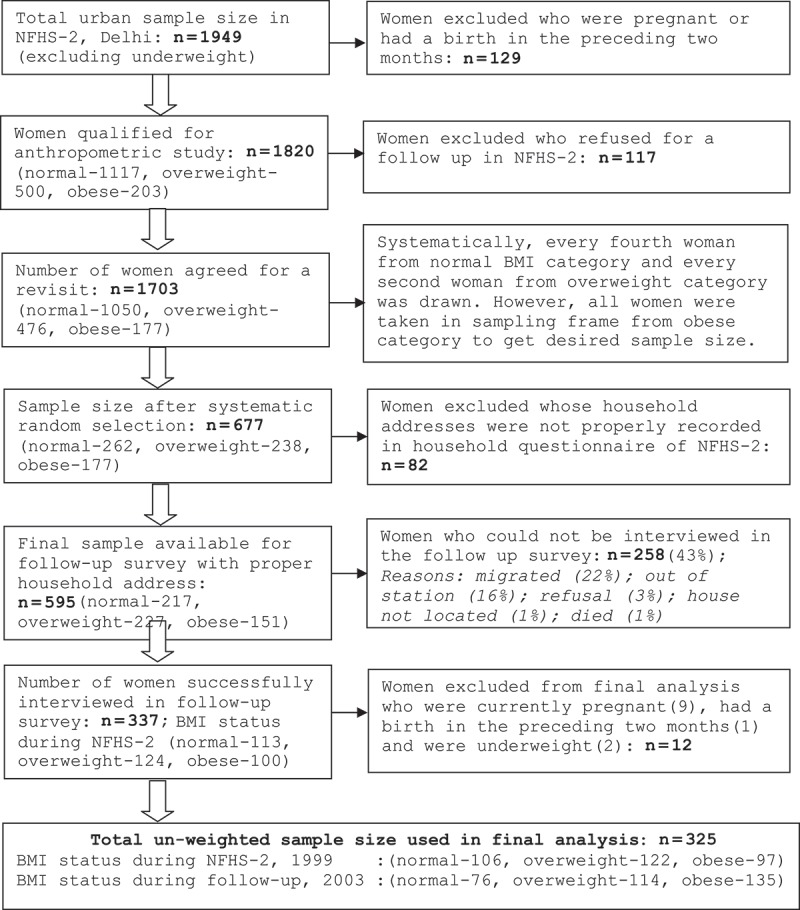

In the NFHS-2 Delhi sample, 1,117, 500, and 203 women were found to be normal weight, overweight, and obese, respectively. In the NFHS-2 survey questionnaire, respondents were asked, “Would you mind if we come again for a similar study at some future date after a year or so?” Those women who objected to a revisit were excluded from the follow-up survey, leaving 1,050 normal weight, 476 overweight, and 177 obese women in the sampling frame. Samples were drawn from each of these three categories through stratified systematic selection. From the normal weight category every fourth woman and from the overweight category every second woman was drawn for the interview. In the obese category, all women were included in the sample to obtain the desired sample size. Thus, a total of 677 women were selected according to these criteria—262 normal, 238 overweight, and 177 obese. For the follow-up survey, the addresses of the selected women were obtained from the NFHS-2 Household Questionnaires. The sample size was further reduced due to non-availability of some questionnaires and non-identified addresses. Finally, a total of 595 women—217 normal, 227 overweight, and 151 obese were included in the follow-up survey. Details of the sample selection and response rate are illustrated in the schematic diagram (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1 .

Selection and participation of sample in the follow-up survey.

In the follow-up survey, 57 percent of the eligible women (n = 337) were successfully interviewed—113 normal weight, 124 overweight, and 100 obese women. A total of 43 percent of the sample (258 women) could not be interviewed as they were away on the day of interview as well as after three revisits (16 percent), had migrated (22 percent), residence could not be located (1 percent), died (1 percent), or refused an interview (3 percent). Women who were pregnant (n = 9) at the time of the follow-up survey, women who had given birth during the 2 months preceding the survey (n = 2), and underweight women (n = 1) were excluded from the final analysis. The findings are thus based on the remaining 325 respondents. A separate analysis using NFHS-2 data confirmed that socio-demographic characteristics of women interviewed and those who could not be interviewed in the follow-up survey were very similar (data not shown) so that the follow-up sample was representative of the NFHS-2 sample population.

Anthropometric Measurements

In NFHS-2 as well as in the follow-up survey, each ever-married woman was weighed in light clothes with shoes off using a solar-powered digital scale with an accuracy of ±100 gms. Their height was also measured using an adjustable wooden measuring board, specifically designed to provide accurate measurements (to the nearest 0.1 cm) in a developing country field situation. These data were used to calculate the individual BMIs, computed by dividing weight (in kilograms) by the square of height (in meters) [kg/m2] (WHO 1995). A woman with a BMI between 25 and 29.9 was considered to be overweight; a BMI of 30 or greater was considered to be obese; a BMI of 35 or greater was considered to be morbidly obese. However, a woman with a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 was considered normal weight, and a woman was considered as underweight if the BMI was below 18.5 (WHO 1995).

Variables Studied

To understand overweight and obese women’s psychosocial factors, a series of questions were developed for this survey and asked of the overweight and obese respondents during the time of personal interview. The questions were: Do you have problems in walking?; Do you have problems while climbing a staircase?; Do you have problems in doing household chores?; Do you have problems squatting?; Does you/your husband feel sexual dissatisfaction at any time?; Do people make fun of you in your presence?; Do people make fun of you in your absence?; Do people pass comments upon you?; What types of comments do they pass?; Do you react to those comments?, etc. Based on the responses to the above questions, four psychosocial factors were considered: day-to-day problems, body image dissatisfaction, sexual dissatisfaction, and stigma and discrimination.

Characteristics of the respondents that were included as potential confounders in the study (which were selected on the basis of previous knowledge of their association with the study outcome) were: age group in years (20–34, 35–54), education (illiterate, literate but < middle school complete, middle school complete, high school complete, and above), religion (Hindu, Muslims, Sikh, and Others), caste/tribe status (Scheduled caste/tribes, Other class, Others), household standard of living (low/medium, high), employment status (not working, working), and media exposure (never reads newspaper, reads newspaper occasionally, reads newspaper daily) (Table 1).

TABLE 1 .

Characteristics of the Study Population (n = 236) Aged 20–54 Years, Delhi, 2003

| Characteristics | Percent | Number of women |

|---|---|---|

| Current body mass index1 | ||

| Overweight (BMI 25.0–29.99 kg/m2) | 43.6 | 103 |

| Obese (BMI 30.0–34.99 kg/m2) | 39.4 | 93 |

| Morbidly obese (BMI ≥35.0 kg/m2) | 16.9 | 40 |

| Current age (years) | ||

| 20–34 | 33.1 | 78 |

| 35–54 | 66.9 | 158 |

| Mean age (years) | 41.2 | 236 |

| Education2 | ||

| Illiterate | 13.6 | 32 |

| Literate, < middle school complete | 15.3 | 36 |

| Middle school complete | 13.6 | 32 |

| High school complete and above | 57.6 | 136 |

| Religion | ||

| Hindu | 79.7 | 188 |

| Muslim | 8.5 | 20 |

| Sikh or others3 | 11.9 | 28 |

| Caste/tribe status4 | ||

| Scheduled caste/tribes | 8.1 | 19 |

| Other class | 8.1 | 19 |

| Others | 83.9 | 198 |

| Standard of living index5 | ||

| Low/medium | 13.5 | 31 |

| High | 86.5 | 199 |

| Employment status | ||

| Not working | 92.3 | 217 |

| Working | 7.7 | 18 |

| Media exposure | ||

| Never reads newspapers | 53.4 | 126 |

| Reads newspapers occasionally | 11.0 | 26 |

| Reads newspapers daily | 35.6 | 84 |

| Total | 100.0 | 236 |

1Women who were pregnant at the time of the survey, or who had given birth during the 2 months preceding the survey, were excluded from these anthropometric measurements.

2Illiterate–-0 years of education; literate but less than middle school complete–-1–5 years of education, middle school complete–-6–8 years of education, high school complete or more–-9+ years of education.

3Buddhist, Christian, Jain, Jewish, or Zoroastrian.

4Scheduled castes and Scheduled tribes are identified by the Government of India as socially and economically backward and needing protection from social injustice and exploitation. Other class category is a diverse collection of intermediate castes that were considered low in the traditional caste hierarchy but are clearly above SC. Others’ is a default residual group that enjoys higher status in the caste hierarchy.

5Standard of living (SLI) was defined in terms of household assets and material possessions and these have been shown to be reliable and valid measures of household material well-being (Filmer and Pritchett 2001). It is an index (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro 2000), which is based on ownership of a number of different consumer durables and other household items. It is calculated by adding the following scores: house type: 4 for pucca, 2 for semi pucca, 0 for kachha; toilet facility: 4 for own flush toilet, 2 for public or shared flush toilet or own pit toilet, 1 for shared or public pit toilet, 0 for no facility; source of lighting: 2 for electricity, 1 for kerosene, gas, or oil, 0 for other source of lighting; main fuel for cooking: 2 for electricity, liquefied natural gas, or biogas, 1 for coal, charcoal, or kerosene, 0 for other fuel; source of drinking water: 2 for pipe, hand pump, or well in residence/yard/plot, 1 for public tap, hand pump, or well, 0 for other water source; separate room for cooking: 1 for yes, 0 for no; ownership of house: 2 for yes, 0 for no; ownership of agricultural land: 4 for 5 acres or more, 3 for 2.0–4.9 acres, 2 for less than 2 acres or acreage not known, 0 for no agricultural land; ownership of irrigated land: 2 if household owns at least some irrigated land, 0 for no irrigated land; ownership of livestock: 2 if own livestock, 0 if do not own livestock; durable goods ownership: 4 for a car or tractor, 3 each for a moped/scooter/motorcycle, telephone, refrigerator, or color television, 2 each for a bicycle, electric fan, radio/transistor, sewing machine, black and white television, water pump, bullock cart, or thresher, 1 each for a mattress, pressure cooker, chair, cot/bed, table, or clock/watch. Index scores range from 0–14 for low SLI to 15–24 for medium SLI to 25–67 for high SLI.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were reported, and the study hypotheses were evaluated using multivariate methods. All reported p values were based on two-sided tests, mainly the Pearson’s chi-squared test. The associations between overweight/obesity and the four psychosocial factors were estimated using multivariable logistic regression models, adjusting for socio-economic and demographic factors and examining for the independent effects of possible covariates (see the appendix for details). The parameters in the logistic regression models were estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation method, and a Likelihood Ratio Test was conducted to assess the significance of the overall model with p values for the coefficients for the independent variables included. The goodness of fit was assessed through pseudo R 2 statistics. We, however, did not test for any interactions in any of the models presented in this study. Results are presented in the form of odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The estimation of confidence intervals takes into account the design effects due to clustering at the level of the primary sampling unit. Before carrying out the multivariate models, we tested for the possibility of multicolinearity between the studied variables. In the correlation matrix, all pairwise Pearson correlation coefficients were <0.5, which suggested that multicolinearity was not a problem. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 19.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Chicago, IL, USA).

Ethical Approval

The study protocol received ethical approval from the International Institute for Population Science’s Ethical Review Board. Informed consent, which was read to the respondents verbally, was obtained from all respondents in both NFHS-2 and the follow-up survey before starting the interview and before obtaining measurements of their height and weight.

RESULTS

The study population had almost equal percentages of overweight (43.6 percent) and obese (39.4 percent) women, whereas 17 percent were morbidly obese (Table 1). Almost one-third of the respondents were below the age of 35 years; the mean age of the respondents was 41.2 years. Over half of the study population (58 percent) had completed high school, while one-seventh was illiterate. Almost 80 percent of the respondents were Hindu, the rest being Muslim, Sikh, and Others. Regarding caste/tribe distribution, “Others” was the predominant category (84 percent), and the sample had an equal percentage of Scheduled Castes/Tribes (8 percent) and Other class (8 percent). A majority of the respondents (87 percent) belonged to households with a higher standard of living, whereas less than 14 percent of women belonged to households with a medium or lower standard of living. An overwhelming majority of women (92 percent) were not working.

Regarding day-to-day problems, problems in walking was reported by significantly more morbidly obese women (58 percent), followed by 44 percent of obese women and 28 percent of overweight women (all p values < .0001) (Table 2). Problems in climbing stairs was reported by two in five overweight women, three in five obese women, and three in four morbidly obese women (p < .0001). Likewise, problems doing household chores was reported by 17 percent, 30 percent, and 45 percent (p < .0001) of the overweight, obese, and morbidly obese women, respectively. Problems squatting was reported by 17 percent, 28 percent, and 40 percent (p < .0001) of the overweight, obese, and morbidly obese women, respectively. Almost three out of four overweight women were not happy with their body image compared to four out of five obese women and almost all (95 percent) morbidly obese women (p < .0001).

TABLE 2 .

Percentage of Women Reporting Psychosocial Factors by Level of Their BMI, Delhi, 2003

| Current Body Mass Index |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problems | Overweight (25.0–29.99 kg/m2) | Obese (30.0–34.99 kg/m2) | Morbidly obese (>35 kg/m2) | Total | χ2p values |

| Day-to-day problems | |||||

| Walking | 28.2 | 43.5 | 57.5 | 39.1 | <0.0001 |

| Climbing staircase | 39.8 | 61.3 | 75.0 | 54.2 | <0.0001 |

| Doing household chores | 16.5 | 30.1 | 45.0 | 26.7 | <0.0001 |

| Squatting | 39.8 | 61.3 | 75.0 | 54.2 | <0.0001 |

| Dissatisfaction with body image | 59.4 | 80.4 | 95.0 | 73.8 | <0.0001 |

| Sexual dissatisfaction | |||||

| Husband feel sexual dissatisfaction | 4.9 | 5.7 | 10.0 | 6.1 | |

| Woman feel sexual dissatisfaction | 3.9 | 6.8 | 7.7 | 5.7 | |

| Stigma and discrimination | |||||

| People makes fun in her presence | 3.9 | 12.9 | 20.5 | 10.2 | <0.0001 |

| People makes fun behind her back | 2.9 | 6.5 | 27.5 | 8.5 | <0.0001 |

| Teasing | 2.9 | 10.8 | 22.5 | 9.3 | <0.0001 |

| Number of women | 103 | 93 | 40 | 236 | |

Sexual dissatisfaction of women and their husbands increased as the BMI of the women increased. Participants’ reports indicated that husbands of about 5 percent overweight women felt sexual dissatisfaction compared to 6 percent of husbands of obese women and one out of ten husbands of morbidly obese women. A higher percentage of women with a higher BMI faced stigma and discrimination. About 4 percent of overweight women reported that people made fun of them compared to 13 percent of obese women and 21 percent of medically obese women (all p values < .0001). Moreover, a substantially higher percentage of the morbidly obese women reported that people made fun of them behind their backs (27 percent) (p < .0001).

Day-to-day problems, dissatisfaction with body image, and stigma and discrimination were significantly associated with level of BMI (Table 3). As expected, a majority of morbidly obese women reported having day-to-day problems (80 percent) compared to 63 percent of obese women and 47 percent of overweight women. Similarly, almost all morbidly obese women (95 percent) reported dissatisfaction with their body image compared to 80 percent of obese women and 59 percent of overweight women. Also, one out of three morbidly obese women faced stigma and discrimination compared to 18 percent obese and 6 percent overweight women. However, one out of ten morbidly obese women reported sexual dissatisfaction compared to 7 percent obese and 5 percent overweight women, a statistically non-significant difference. A significantly (p < .0001) higher proportion of women over 35 years of age (70 percent compared to 37 percent among 20–34 year-olds) and those who did not read a newspaper (67 percent compared to 50 percent who read a newspaper) reported day-to-day problems. A higher proportion of non-working women (75 percent compared to 53 percent working) reported dissatisfaction with their body image (p < .0001). A significantly higher proportion of younger women (age below 35 years) (23 percent compared to 11 percent among 35–53 years) and women who were not working (16 percent compared to those who worked) reported stigma and discrimination problems.

TABLE 3 .

Percentage of Women Reporting Day-to-day Problems, Body Image Dissatisfaction, Sexual Dissatisfaction, and Stigma and Discrimination by Level of BMI and Background Characteristics, Delhi, 2003

| Day-to-day problems |

Dissatisfaction with body image |

Sexual dissatisfaction |

Stigma and discrimination |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women’s characteristics | % | χ2p values | % | χ2p values | % | χ2p values | % | χ2p values |

| Current body mass index (kg/m2) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.256 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Overweight (25.0–29.99) | 46.6 | 59.4 | 4.9 | 5.8 | ||||

| Obese (30.0–34.99) | 63.4 | 80.4 | 6.8 | 18.3 | ||||

| Morbidly obese (>35) | 80.0 | 95.0 | 10.0 | 32.5 | ||||

| Current age (years) | <0.0001 | 0.452 | 0.356 | <0.0001 | ||||

| 20–34 | 37.2 | 77.9 | 5.1 | 23.1 | ||||

| 35–53 | 69.6 | 71.8 | 7.2 | 11.4 | ||||

| Education | 0.569 | 0.478 | 0.965 | 0.214 | ||||

| Illiterate | 71.9 | 68.8 | 13.3 | 12.5 | ||||

| Literate, < middle school complete | 63.9 | 69.4 | 5.7 | 19.4 | ||||

| Middle school complete | 68.8 | 86.7 | 3.3 | 9.4 | ||||

| High school complete and above | 52.2 | 73.3 | 5.9 | 16.2 | ||||

| Religion | 0.254 | 0.257 | 0.587 | 0.635 | ||||

| Hindu | 57.4 | 70.8 | 6.0 | 14.9 | ||||

| Muslim | 75.0 | 90.0 | 15.8 | 25.0 | ||||

| Others | 57.1 | 82.1 | 3.6 | 10.7 | ||||

| Caste/tribe status | 0.368 | 0.457 | 0.789 | 0.245 | ||||

| Scheduled caste/tribes | 52.6 | 63.2 | 10.5 | 15.8 | ||||

| Other class | 68.4 | 73.7 | 11.1 | 21.1 | ||||

| Others | 58.6 | 74.9 | 5.7 | 14.6 | ||||

| Standard of living index | 0.547 | 0.659 | 0.234 | 0.125 | ||||

| Low/medium | 64.5 | 74.2 | 3.3 | 22.6 | ||||

| High | 58.3 | 73.0 | 7.2 | 13.6 | ||||

| Employment status | 0.241 | <0.0001 | 0.524 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Not working | 59.9 | 75.3 | 7.1 | 16.6 | ||||

| Working | 44.4 | 52.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||||

| Media exposure | <0.0001 | 0.254 | 0.421 | 0.354 | ||||

| Read a newspaper | 50.0 | 75.2 | 3.6 | 15.5 | ||||

| Never read a newspaper | 66.7 | 72.6 | 9.1 | 15.1 | ||||

| Total | 58.9 | 73.8 | 6.5 | 15.3 | ||||

Morbidly obese (aOR 5.29, 95% CI 2.02–13.81, p < .001) and obese (aOR 2.30, 95% CI 1.20–4.42, p = .001) women were significantly more likely to report day-to-day problems than overweight women, adjusting for socio-economic characteristics (Table 4). Additionally, except for age (aOR 1.11, 95% CI 1.06–1.16, p = .001), no other factors were significantly related to day-to-day problems. Furthermore, morbidly obese (aOR 11.88, 95% CI 2.62–53.87, p < .001) and obese (aOR:2.92, 95% CI 1.45–5.88, p = .001) women were significantly more likely to report dissatisfaction with body image, while morbidly obese (aOR 9.41, 95% CI 2.96–29.94, p < .001) and obese (aOR 2.93, 95% CI 1.03–8.37, p = .001) women were more likely to report stigma and discrimination than overweight women adjusting for socio-economic characteristics. However, in the case of sexual dissatisfaction, none of the factors were statistically significantly related in the adjusted model.

TABLE 4 .

Adjusted Odds Ratios With 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) for BMI and Other Characteristics Related to Women’s Day-to-Day Problems, Body Image Dissatisfaction, Sexual Dissatisfaction, and Problem of Stigmatization and Discrimination, Delhi, 2003

| Day-to-day problem | Dissatisfaction with body image | Sexual dissatisfaction | Stigma and discrimination | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women’s characteristics | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

| Current body mass index | ||||

| OverweightR | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Obese | 2.30 (1.20–4.42) | 2.92 (1.45–5.88) | 1.48 (0.41–5.35) | 2.93 (1.03–8.37) |

| Morbidly obese | 5.29 (2.02–13.81) | 11.88 (2.62–53.87) | 2.08 (0.46–9.40) | 9.41 (2.96–29.94) |

| Age (years) squared | 1.11 (1.06–1.16) | 0.96 (0.92–1.01) | 0.97 (0.89–1.05) | 0.94 (0.89–1.00) |

| Education | ||||

| IlliterateR | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Literate, < middle school complete | 0.55 (0.17–1.82) | 1.10 (0.33–3.69) | 0.45 (0.07–3.10) | 2.10 (0.47–9.51) |

| Middle school complete | 0.60 (0.17–2.16) | 2.56 (0.59–11.10) | 0.24 (0.02–2.88) | 0.59 (0.08–4.32) |

| High school complete and above | 0.42 (0.13–1.32) | 1.15 (0.36–3.65) | 0.58 (0.11–3.20) | 1.88 (0.43–8.27) |

| Religion | ||||

| HinduR | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Muslim | 1.38 (0.41–4.57) | 2.89 (0.57–14.69) | 2.57 (0.50–13.09) | 1.73 (0.46–6.52) |

| Others | 1.05 (0.41–2.73) | 1.90 (0.62–5.83) | 0.53 (0.06–4.69) | 0.55 (0.13–2.23) |

| Caste/tribe status | ||||

| Scheduled caste/ tribesR | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Other class | 1.10 (0.25–4.79) | 1.99 (0.42–9.52) | 0.60 (0.06–5.70) | 1.57 (0.24–10.41) |

| Others | 1.04 (0.33–3.24) | 1.60 (0.50–5.17) | 0.42 (0.07–2.59) | 0.84 (0.18–3.85) |

| Standard of living index | ||||

| Low/MediumR | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| High | 0.89 (0.34–2.34) | 0.96 (0.34–2.71) | 5.89 (0.63–55.01) | 0.69 (0.21–2.21) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Not workingR | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Working | 0.64 (0.21–1.98) | 0.49 (0.16–1.51) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) |

| Media exposure | ||||

| Read a newspaperR | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) |

| Never read a newspaper | 1.41 (0.76–2.64) | 0.71(0.35–1.44) | 2.20 (0.61–7.95) | 0.89 (0.38–2.11) |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.117 | 0.121 | 0.118 | 0.198 |

| Constant | 0.118 | 0.130 | 0.120 | 0.116 |

| Number of women | 229 | 226 | 224 | 229 |

RDenotes reference category.

DISCUSSION

Our study systematically examined the psychosocial factors related to being overweight or obese among overweight, obese, and morbidly obese married women in India. This study makes an important contribution by examining weight stigma in Indian women because most of the published research on the social and psychological factors related to obesity has been conducted in western countries, and thus less information is known about the psychosocial conditions associated with obesity in other regions of the world. This is the first empirical evidence of which we are aware of, that studied psychosocial factors associated with obesity among women in a developing country, such as India, which has faced an increasing prevalence of obesity in its adult female population during the last decade. We found that day-to-day problems, dissatisfaction with body image, sexual dissatisfaction, and stigma and discrimination were significantly associated with increased BMI. Our findings suggest that morbidly obese and obese women have several psychological and social problems and calls for public health interventions in obesity care.

Previous studies have found that more obese women reported problems with all activities of daily living except eating. The greatest differences in limitations by body size were seen for activities involving mobility, such as walking, transferring, climbing stairs, and lifting (Himes 2000). In this study, we also found a considerably higher proportion of morbidly obese women reporting problems, such as walking, climbing stairs, squatting, doing household chores, sexual dissatisfaction, mockery, and comments because of their physique. In addition to reporting more problems in their day to day life, sexual life, and being made fun of and facing the derogatory comments of people, women with higher BMI were not happy with their physique. Even most of the morbidly obese women replied during the time of the personal interview that their physique was the root cause of every problem and thus they had a very poor self image. Studies in the west have reported that overweight people frequently had a poor self image (Colman and Dodds 2000; Makara-Studzińska and Zaborska 2009). An earlier Swedish obesity study in 1993 demonstrated the impact of severe obesity in more formal terms (Sullivan et al. 1993). Measures of psychosocial functioning were collected from nearly 2,000 obese individuals before therapeutic surgery. Body image was found to be the major factor related to depression and obesity-related problems in their social life.

Prejudice and discrimination can be conceptualized as chronic stressors that could have deleterious effects on emotional well-being (Fabricatore and Wadden 2003; Wardle and Cooke 2005). Given society’s bias against them, obese individuals might be expected to experience more psychological distress than their average-weight peers but early studies of the psychosocial status of obese individuals in the general population yielded inconsistent results. Some studies have found that obesity was related to greater emotional distress (Ozmen et al. 2007), whereas others reported that obese people displayed less psychological disturbance (Carr, Friedman, and Jaffe 2007). When considering psychological aspects of obesity, most psychological disturbances are more likely to be consequences rather than causes of obesity (Wardle and Cooke 2005; Ali and Lindström 2005). One of the most convincing illustrations of the psychological implications of obesity (Rand and Macgregor 1991) was based on interviews of morbidly obese participants after they had lost weight by surgical means. Most patients reported that they would prefer to be normal weight with a major handicap (deaf, dyslexic, diabetic, legally blind) than to be obese again.

Certain social circumstances might be predisposing to development of weight problems, while obesity appears to create conditions leading to psychosocial disturbances. In combination with the associated health risks, obesity should be considered as a priority public health problem for women. Regarding the evidence that obesity is related to psychosocial disabilities, mitigation in key psychological and social areas could be undertaken (Maclean et al. 2009). Specifically, current attitudes toward ideal body weight need to be re-examined, including part of the education of health professionals (Wang and Brownell 2005). Moreover, the advertising industry, which has played a major role in creating the extremely lean aesthetic ideal body size in modern society (Andersen and DiDomenico 1992), has the potential for influencing future attitudes in a positive and more realistic direction. Stereotypic negative attitudes toward obese individuals are not only prevalent, but socially acceptable to a much larger extent than, for example, racial and religious prejudices (Puhl and Heuer 2009). Thus, the problem of downward social mobility as a consequence of obesity is a public consciousness issue (Puhl and Brownell 2006). In developed countries where obesity rates are high and rising, special laws safeguard the protection of obese individuals’ rights (Federal Reporter 1993), but such arrangements are lacking in India. Another practical consequence of recognizing severe obesity as a disability might be to provide improved resources for psychological and medical treatment for obesity, e.g., eating disorders clinics, surgery, etc. (Shaw et al. 2005).

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

Some strengths of our study deserve comment. First, our study was based in the national capital territory of Delhi, which typifies a multicultural and multiethnic population representing India’s growing urban populations. Second, few studies have been conducted in India or developing countries that have examined the psychosocial factors related to excess weight among overweight and obese women at the population level. Our study used actual measured weights and heights to construct current BMI without relying on self-reported values, which could otherwise be over- or under-estimated. For these reasons this study is an important contribution to address this existing gap in knowledge in India.

Some limitations of this study also deserve attention. The poor response rate was a limitation in this study because it could have introduced participation bias, resulting in inaccuracy and lack of generalizability of the results. Although rigorous methods were used, including cross-checks and back-checks to achieve high quality data, some measurement errors cannot be ruled out (International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro 2000). Secondly, although we adjusted for several key socio-demographic factors, other potentially confounding characteristics and behaviors that were not measured in our study may have confounded our results. For example, we could not capture discrimination at workplace (if any) because more than 90 percent of our respondents were not working at the time of survey. Furthermore, because of the cross-sectional nature of our study and the interdependency of many of the variables, no definite statement on temporality or causal directions among the independent and dependent variables can be made. Lastly, we did not use any standard instruments for collecting data on the variables studied, and thus the questions were developed for this study. This could have resulted in misclassification of information and makes the information non-comparable to other studies that did use standard instruments.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, psychological and behavioral issues play significant roles in obesity. A multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of obesity that addresses psychological and social factors is critical to ensure comprehensive care, as well as best practices and outcomes. The importance of addressing the psychological aspects of obesity has become more explicit over the last two decades. Our findings suggest that being morbidly obese may be associated with serious psychological and social factors and thus calls for imperative measures for public health interventions in obesity care in India. The psychosocial problems of women, if repeated day after day and for years, may lead to depression, anxiety, or low self-esteem. Truly morbid obesity is a chronic medical illness, and it is thus important to educate the society and lay people alike of the seriousness of this disease and the need to change the way it is viewed and treated.

FUNDING

Sutapa Agrawal is supported by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award Grant No. WT084674 to Prof. Shah Ebrahim.

APPENDIX

Logistic Regression—Estimating Model Parameters, Comparing Models, and Assessing Model Fit

To adjust for potentially confounding factors, we used multivariate logistic regression models, as follows:

where b1, b2, …, bi represent the coefficient of each of the independent variables included in the model, and ei is an error term. Ln[p/(1 − p)] represents the natural logarithms of the odds of the outcome variable or dependent variable, which in this case are the four psychosocial conditions. The odds ratios are thus the measures of odds of four psychosocial conditions, such as day-to-day problems, dissatisfaction with body image, sexual dissatisfaction, and stigma and discrimination (response variables) as indicated by the main independent variable, such as current body mass index (0 = overweight, 1 = obese, 2 = morbidly obese) and other socioeconomic and demographic confounders. This model has been used to elicit the net effects of each of the explanatory variables while accounting for the other independent variables under analysis on the likelihood of reporting four psychosocial conditions. The response variable (four psychosocial conditions) was categorized into two mutually exclusive and exhaustive categories: respondents reporting any of the four psychosocial conditions (coded as 1) or respondents not reporting any of the four psychosocial conditions (coded as 0). With regard to the direction of logit coefficients, odds greater than 1 indicated an increased probability that women reported any condition, whereas odds greater than 1 indicated a decreased probability. The logistic regression equation estimates the effect of one unit change in the independent variable (when x is discrete) on the logarithm of odds (log-odds) that the dependent variable takes when controlled for the effects of other independent variables (Allison 1984; Retherford and Choe 1993; Yamaguchi 1991).

We used the Maximum Likelihood Estimation method to estimate the logistic regression model coefficients for categorical variables (available at http://www.moresteam.com). This method yields values of α and β, which maximize the probability of obtaining the observed set of data. To find the values of the parameters that maximize the above function, we differentiated this function with respect to α and β and set the two resulting expressions to zero. An iterative method was used to solve the equations, and the resulting values of α and β are called the maximum likelihood estimates of those parameters. The same approach is used in the multiple predictor case where we would have (p + 1) equations corresponding to the p predictors and the constant α.

Once we fit a particular logistic regression model, the first step was to assess the significance of the overall model with p coefficients for the independent variables included. This was done via a Likelihood Ratio Test, which tests the null hypothesis H0: β1 = β2 … = βp = 0.

In assessing model fit, we also examined how well the model described (fit) the observed data. One way to assess goodness of fit (GOF) is to examine how likely the sample results are, given the parameter estimates. The pseudo R 2 statistics can be used to assess the fit of the chosen model. This statistic is slightly analogous to the coefficient of determination statistic from linear regression analysis, in that it takes values in the range 0 to 1 and larger values indicate a better fit. However, it cannot be interpreted as the amount of variance in Y explained by the variable X.

Funding Statement

Sutapa Agrawal is supported by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award Grant No. WT084674 to Prof. Shah Ebrahim.

REFERENCES

- Agrawal P. K. Dynamics of obesity among women in India: A special reference to Delhi. International Institute for Population Sciences; Mumbai, India: 2004. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal P., Gupta K., Mishra V. Agrawal S. Effects of sedentary lifestyle and dietary habits on body mass index change among adult women in India: Findings from a follow-up study. Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 2013;52(5):387–406. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2012.719346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal P., Gupta K., Mishra V. Agrawal S. A study on body-weight perception, future intention and weight-management behaviour among normal-weight, overweight and obese women in India. Public Health Nutrition. 2014;17(4):884–95. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal P., Mishra V. East West Center Working Papers. 2004;116 http://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/handle/10125/3748/POPwp116.pdf?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal P., Mishra V. Agrawal S. Covariates of maternal overweight and obesity and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes: Findings from a nationwide cross sectional survey. Journal of Public Health. 2012;20:387–97. doi: 10.1007/s10389-011-0477-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S. M. Lindström M. Socioeconomic, psychosocial, behavioural, and psychological determinants of BMI among young women: Differing patterns for underweight and overweight/obesity. European Journal of Public Health. 2005;16(3):324–30. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison P. D. Event history analysis: Regression for longitudinal event data. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1984. Series on quantitative applications in the social sciences; pp. 07–046. No. [Google Scholar]

- Altman D. G. Missing outcomes: Addressing the dilemma. Open Medicine. 2009;3:e21–e23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen A. E. DiDomenico L. Diet vs. shape content of popular male and female magazines: A dose-response relationship to the incidence of eating disorders? The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1992;11:283–87. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1098-108X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blundell J. E., Burley V. J., Cotton J. R. Lawton C. L. Dietary fat and the control of energy intake: Evaluating the effects of fat on meal size and post meal satiety. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1993;57:772s–78s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.5.772S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter K. M., Hasin D. S., Allison D. B. Faith M. S. Relationships between obesity and DSM-IV major depressive disorder, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts: Results from a general population study. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:251–57. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. Friedman M. A. Is obesity stigmatizing? Body weight, perceived discrimination, and psychological well-being in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46(3):244–59. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D., Friedman M. A. Jaffe K. Understanding the relationship between obesity and positive and negative affect: The role of psychosocial mechanisms. Body Image. 2007;4(2):165–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman R., Dodds C. 2000 http://www.gpiatlantic.org/pdf/health/obesity/que-obesity.pdf Cost of obesity in qubec. In Genuine progress index: Measuring sustainable development, pp. 1–53. Glen Haven, NS: GPI Atlantic. (accessed May 16, 2013).

- Dowse G. K., Hodge A. M. Zimmet P. Z. Paradise lost: Obesity and diabetes in Pacific and Indian Ocean populations. In: Angel A., Anderson H., Bouchard C., editors. In Progress in obesity research. London, UK: John Libbey & Co; 1995. pp. 227–238. Vol. et al., pp. [Google Scholar]

- Elfhag K. Rössner S. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? A conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obesity Reviews. 2005;6(1):67–85. doi: 10.1111/obr.2005.6.issue-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabricatore A. N. Wadden T. A. Psychological functioning of obese individuals. Diabetes Spectrum. 2003;16(4):245–52. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.16.4.245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Reporter Bonnie cook vs. state of Rhode Island Department of Mental Health, Retardation and Hospitals. 1st Circuit Court of Appeals. 1993;10(3):17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Filmer D. Pritchett L. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data—Or tears: An application to educational enrolments in states of India. Demography. 2001;37:155–74. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane M. M., Stevens G. A., Cowan M. J., Danaei G., Lin J. K., Paciorek C. J., Singh G. M. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: Systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. The Lancet. 2011;377:557–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopinath N., Chadha S. L., Jain P., Shekhawat S. Tandon R. An epidemiological study of obesity in adults in the urban population of Delhi. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 1994;42:212–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himes C. L. Obesity, disease, and functional limitation in later life. Demography. 2000;37(1):73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), and Macro International . National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) I. Mumbai, India: IIPS; 2007. 2005–06: India-vol. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), and ORC Macro . National Family Health Survey (NFHS-2) Mumbai, India: IIPS; 2000. 1998–99: India. [Google Scholar]

- Jia H. Lubetkin E. I. The impact of obesity on health-related quality-of-life in the general adult US population. Journal of Public Health. 2005;27(2):156–64. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolotkin R. L., Meter K. Williams G. R. Quality of life and obesity. Obesity Reviews. 2001;2(4):219–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789X.2001.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner R. F. Foster G. D. Obesity and quality of life. Nutrition. 2000;16(10):947–52. doi: 10.1016/S0899-9007(00)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissner L., Levitsky D. A., Strupp B. J., Kalkwarf H. J. Roe D. A. Dietary fat and the regulation of energy intake in human subjects. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1987;46:886–92. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/46.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean L., Edwards N., Garrard M., Sims-Jones N., Clinton K. Ashley L. Obesity, stigma and public health planning. Health Promotion International. 2009;24(1):88–93. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dan041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makara-Studzińska M. Zaborska A. Obesity and body image. Psychiatria Polska. 2009;43(1):109–14. in Polish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz S., Friedman M. A. Arent S. M. Understanding the relation between obesity and depression: Causal mechanisms and implications for treatment. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Muennig P. The body politic: The relationship between stigma and obesity-associated disease. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman P. LeBlanc C. M. A. Psychosocial aspects of child and adolescent obesity. Canadian paediatric society healthy active living and sports medicine committee abridged version. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2012;17(3):205–06. doi: 10.1093/pch/17.4.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens T. M. Morbid obesity: The disease and comorbidities. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly. 2003;26(2):162–65. doi: 10.1097/00002727-200304000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozmen D., Ozmen E., Ergin D., Cetinkaya A. C., Sen N., Dundar P. E. Taskin E. O. The association of self-esteem, depression and body satisfaction with obesity among Turkish adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2007;16(7):80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl R. Brownell K. D. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obesity Research. 2001;9:788–805. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl R. M. Brownell K. D. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: An investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity. 2006;14(10):1802–15. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl R. M. Heuer C. A. The stigma of obesity: A review and update. Obesity. 2009;17(5):941–64. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhl R. M. Heuer C. A. Obesity stigma: Important considerations for public health. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1019–28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand C. S. W. Macgregor A. M. C. Successful weight loss following obesity surgery and the perceived liability of morbid obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 1991;15:577–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retherford R. D. Choe M. K. Statistical models for causal analysis. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen A. M., Heliövaara M., Knekt P., Reunanen A. Aromaa A. Determinants of weight gain and overweight in adult Finns. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1991;45:419–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J. Determinants of body fat and its implications for health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1992;14:275–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw K. A., O’Rourke P., Del Mar C. Kenardy J. Psychological interventions for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003818.pub2. Art No: CD003818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin N. Y. Shin M. S. Body dissatisfaction, self-esteem, and depression in obese Korean children. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;152(4):502–06. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J. Obesity and socioeconomic status: A framework for examining relationships between physical and social variables. Medical Anthropology. 1991;13:231–47. doi: 10.1080/01459740.1991.9966050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard J. Sobal J. Psychological consequences of obesity. In: Brownwell K. D., editor; Fairburn C. G., editor. Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 1995. p. 417. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian S. V. Smith G.-D. Patterns, distribution, and determinants of under- and overnutrition: A population-based study of women in India. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;84(3):633–40. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.3.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M., Karlsson J., Sjöström L., Backman L., Bengtsson C., Bouchard C., Dahlgren S., et al. Swedish obese subjects (SOS) - an intervention study of obesity. Baseline evaluation of health and psychosocial functioning in the first 1743 subjects examined. International Journal of Obesity. 1993;17:503–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Merwe M.-T. Psychological correlates of obesity in women. International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31:S14–S18. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadden T. A. Stunkard A. J. The psychological and social complications of obesity. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1985;103:1062–67. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-6-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. S. Brownell K. D. Public policy and obesity: The need to marry science with advocacy. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;28:235–52. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J. Cooke L. The impact of obesity on psychological well-being. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2005;19(3):421–40. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Physical status: The use and interpretation of anthropometry. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 1995. Report of a WHO Expert Committee, WHO Technical Report Series 854. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2003 http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/gs_obesity.pdf Global strategy of diet, physical activity and health (obesity and overweight). London, UK. (accessed October 22, 2012)

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global health risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global status report on non communicable disease. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K. 1991 http://www.moresteam.com Event history analysis, vol 28. Applied Social Research Methods Series. London, UK: Sage Publications. (accessed May 12, 2013).