Abstract

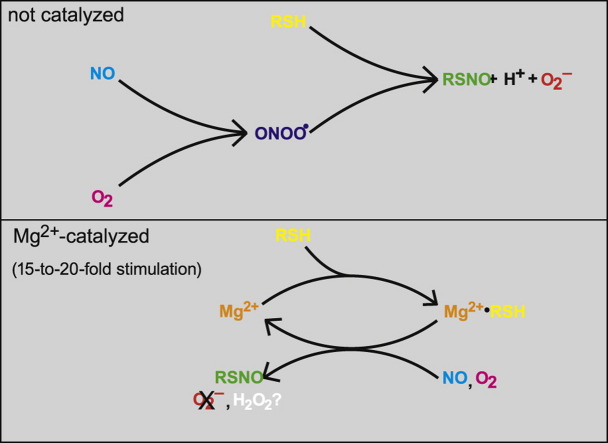

Although different routes for the S-nitrosation of cysteinyl residues have been proposed, the main in vivo pathway is unknown. We recently demonstrated that direct (as opposed to autoxidation-mediated) aerobic nitrosation of glutathione is surprisingly efficient, especially in the presence of Mg2+. In the present study we investigated this reaction in greater detail. From the rates of NO decay and the yields of nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) we estimated values for the apparent rate constants of 8.9±0.4 and 0.55±0.06 M−1 s−1 in the presence and absence of Mg2+. The maximum yield of GSNO was close to 100% in the presence of Mg2+ but only about half as high in its absence. From this observation we conclude that, in the absence of Mg2+, nitrosation starts by formation of a complex between NO and O2, which then reacts with the thiol. Omission of superoxide dismutase (SOD) reduced by half the GSNO yield in the absence of Mg2+, demonstrating O2− formation. The reaction in the presence of Mg2+ seems to involve formation of a Mg2+•glutathione (GSH) complex. SOD did not affect Mg2+-stimulated nitrosation, suggesting that no O2− is formed in that reaction. Replacing GSH with other thiols revealed that reaction rates increased with the pKa of the thiol, suggesting that the nucleophilicity of the thiol is crucial for the reaction, but that the thiol need not be deprotonated. We propose that in cells Mg2+-stimulated NO/O2-induced nitrosothiol formation may be a physiologically relevant reaction.

Abbreviations: RSH, thiol; RS•, thiyl radical; RSNO, nitrosothiol; GSNO, S-nitrosoglutathione ; Alb-SNO, S-nitrosoalbumin ; DEA/NO, diethylamine NONOate (diethylammonium (Z)-1-(N,N-diethylamino)diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate); PROLI/NO, proline NONOate (1-(hydroxyl-N,N,O-azoxy)-L-proline, disodium salt); SPER/NO, spermine NONOate ((Z)-1-[N-[3–aminopropyl]-N-[4-(3-aminopropylammonio)butyl]amino]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate); SOD, Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase; DTPA, diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid; TEA, triethanolamine; DTT, dithiothreitol; NAC, N-acetylcysteine ; PEN, penicillamine; NAP, N-acetylpenicillamine ; 2-ME, 2-mercaptoethanol; DNIC, dinitrosyliron complex

Keywords: S-nitrosation, Nitrosothiol, Glutathione, Nitric oxide, Magnesium, Free radicals

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

NO/O2-induced S-nitrosation below 1 µM NO does not involve autoxidation.

-

•

NO/O2-induced GSNO formation involves reaction of GSH with ONOO•.

-

•

Mg2+ stimulates GSNO formation ≥15-fold.

-

•

Mg2+-catalyzed nitrosation by NO/O2 does not produce superoxide.

-

•

Mg2+ does not stimulate albumin–SNO formation.

Recent years have witnessed a growing interest in the biology of nitrosothiols (RSNOs)1. Because nitrosothiols release nitric oxide (NO) under some conditions and are usually more stable than NO, they are thought to serve as a storage and transport pool, effectively increasing the range and lifetime of NO [1], [2], [3], [4]. Moreover, nitrosation of specific cysteine residues may alter protein function, and evidence is mounting for a physiological role for protein nitrosation in signal transduction [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9].

Whereas a range of enzymatic and nonenzymatic pathways toward nitrosothiol formation has been identified, there is currently no consensus about the way nitrosothiols are generated in vivo [4], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]. Nitrosothiols are known to be formed from NO and thiols (RSHs) under aerobic conditions [15], [16], [17]. This reaction starts with the rate-limiting formation of NO2 (Eq. (1)). After binding another molecule of NO (Eq. (2)), the strong nitrosating agent N2O3 reacts with RSH to form RSNO and nitrite (Eq. (3)) [16], [16]. Alternatively, NO2 may oxidize RSH to produce nitrite and a thiyl radical (RS•) that combines with NO to RSNO (Eqs. (4), (5)) [10], [17], [19]:

| 2NO+O2 →→ 2NO2, | (1) |

| NO2+NO ⇆ N2O3, | (2) |

| N2O3+RSH→RSNO+H++NO2−, | (3) |

| NO2+RSH→RS•+H++NO2−, | (4) |

| NO+RS•→RSNO. | (5) |

Because the rate-limiting first step for both pathways (Eq. (1)) is second order in [NO], autoxidation-mediated nitrosothiol formation is expected to be too slow to make an impact under physiological conditions [3], [4], [5], [10], [12], [13], [17], [20], [21]. At submicromolar NO concentrations a direct reaction between NO and thiols has been reported [22], although later studies (utilizing micromolar NO levels) could not confirm this [11], [23]. Recently, however, we demonstrated that direct nitrosation of glutathione (GSH) by NO occurs at submicromolar concentrations in a reaction that is first order in [NO] (Eq. (6)) and that is enhanced by Mg2+ and other divalent cations [24]:

| NO+O2+GSH→GSNO+O2−+H+. | (6) |

In this paper, by extending these studies to other cations, thiols, and NO donors, we provide more details on the mechanism of the reaction. On the basis of these observations we suggest that direct Mg2+-catalyzed nitrosothiol formation may constitute a physiologically relevant reaction intracellularly but not in the circulation.

Material and methods

Materials

All reagents were obtained from Merck (Vienna, Austria) or Sigma (Vienna, Austria), except for proline NONOate (PROLI/NO), diethylamine NONOate (DEA/NO), spermine NONOate (SPER/NO), and S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), which were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences (Lausen, Switzerland). PROLI/NO, DEA/NO, and SPER/NO were dissolved in 10 mM NaOH; GSH was dissolved in 1 M NaOH; GSNO was dissolved in 10 mM HCl. Other stock solutions were prepared in ultrapure water (Barnstead, resistance >18 MΩ cm−1).

Quantification of NO released by NO donors

To determine the amount of NO released by the NO donors under the applied experimental conditions, we measured the conversion of oxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin spectrophotometrically from the absorbance difference between 420 and 401 nm as published [25], but with 50 mM triethanolamine (TEA; pH 7.4) instead of KPi as the buffer.

Electrochemical determination of NO and GSNO

Nitric oxide was measured with a Clark-type electrode (Iso-NO; WPI, Berlin, Germany) as described previously [26]. Calibration of the electrode was performed daily with NaNO2/KI. All experiments were performed in open, stirred vessels. PROLI/NO was used as a NO donor to investigate the reaction between nitric oxide and GSH. At the start of each experiment 1 µM PROLI/NO was injected in 0.5 ml of 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) containing 0.1 mM diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), 5 mM MgCl2, and 1000 U/ml Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase (SOD). Under these conditions PROLI/NO, which has a half-life of 1.8 s [27], releases NO (1–2 mol/mol) almost instantaneously; subsequently, NO disappears by escape from solution and, to a minor extent, by autoxidation [24]. In our standard procedure 2 mM GSH was added to the solution when the NO concentration dropped to ~0.75 µM. After NO had disappeared, 4 mM CuSO4 was added to measure GSNO formation [28]. Where indicated, the concentrations of GSH and MgCl2 were varied between 0.1 and 5 mM and between 0.05 and 20 mM, respectively. In one series of experiments, GSH was replaced by alternative thiols (cysteine (Cys), N-acetylcysteine (NAC), penicillamine (PEN), N-acetylpenicillamine (NAP), 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME), or dithiothreitol (DTT), Fig. 1); in another series we replaced MgCl2 by alternative salts (CaCl2, NaCl, KCl, ZnSO4, MnSO4, AlCl3, or LaCl3). Where indicated, SOD was omitted from the reaction mixture.

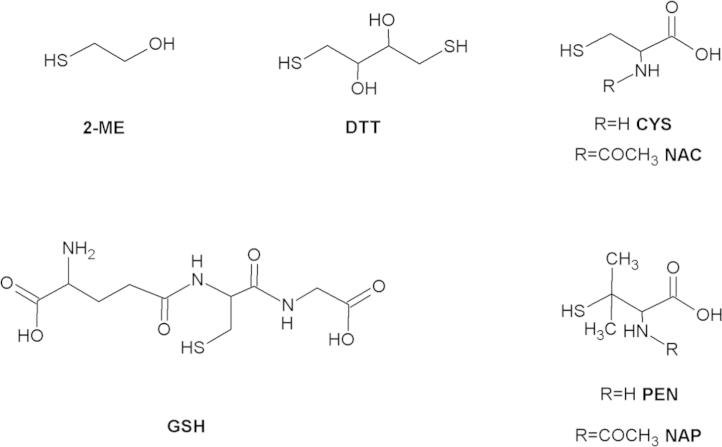

Fig. 1.

Structures of the thiols applied in this study. 2-ME, 2-mercaptoethanol; DTT, dithiothreitol; CYS, cysteine; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; GSH, glutathione; PEN, penicillamine; NAP, N-acetylpenicillamine.

GSNO yields were estimated from the height of the NO peaks that were observed after addition of CuSO4 by comparison with calibration curves obtained with authentic GSNO (0.1–1 µM). In control experiments we affirmed that the various cations and SOD did not affect the height of the NO peak originating from Cu2+-induced GSNO decomposition. Rates for the reaction between NO and GSH were calculated from the data by determining the difference of the NO decay rates immediately before and after addition of GSH (with LabChart 7, ADInstruments). These rates were then divided by the NO concentrations at the time of GSH addition to obtain pseudo-first-order rate constants [24].

Comparison of the efficiencies of nitrosation for PROLI/NO, DEA/NO, and SPER/NO

To compare the efficiencies of nitrosation for various NO donors we used the experimental procedure described in [24]. Accordingly, at the start of the experiment 1 µM PROLI/NO, DEA/NO, or SPER/NO was injected in 0.5 ml of 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) containing 0.1 mM DTPA, 5 mM MgCl2, 1000 U/ml SOD, and 2 mM GSH. The NO concentration was monitored continuously with the electrode. After an incubation time of 2 h, 5 mM CuSO4 was added to determine the GSNO yield.

Determination of GSNO by chemiluminescence

GSNO yields were also determined with a nitric oxide analyzer (NOA 280; Sievers Instruments, Boulder, CO, USA) as published [29]. Samples (500 µl) were incubated with 10% of a solution of sulfanilamide (5% in 1 N HCl) for 1 min to scavenge nitrite. Subsequently, samples were injected in a purging vessel filled with KI/I2 (45 mM/10 mM) in glacial acetic acid. Under these conditions GSNO is reduced to NO, which is then detected by the analyzer. Calibration curves were constructed daily with authentic GSNO (0.1–2 µM) in sample buffer.

Determination of albumin S-nitrosation

Because the addition of high concentrations of albumin interfered with the electrode signal, we determined the nitrosation of albumin essentially according to the method described in [29]. Specifically, at the start of the experiment 1 µM PROLI/NO was injected in 0.5 ml of 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) containing 0.1 mM DTPA, 1000 U/ml SOD, and bovine serum albumin (Sigma–Aldrich Cat. No. A7906 or A5470) at the indicated concentrations in the presence or absence of 5 mM MgCl2. The NO concentration was monitored continuously with the electrode. After NO had disappeared, the S-nitrosoalbumin (Alb-SNO) content of the samples (500 µl) was determined by chemiluminescence as described above for GSNO. Quantification was achieved by comparison with calibration curves of Alb-SNO (0.05–1 µM), which was freshly prepared as described [29]. Albumin contains one free thiol that is partly oxidized in commercial preparations. With Ellman׳s reagent we found the level of free thiols to be only 47.1±1.3 and 42.0±1.2% in Nos. A7906 and A5470 albumin, respectively (n=3). However, because the results were calibrated with Alb-SNO prepared from the same source, this does not lead to underestimation of the level of nitrosation.

Determination of GSNO by HPLC

GSNO was determined by HPLC (Merck-Hitachi D-6000; Vienna, Austria) as published [30]. The mobile phase (20 mM K2HPO4, 50 µM neocuproine, 50 µM DTPA, pH 7.5) was pumped through a Lichrospher column (RP-18; 5 µm) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Samples (100 µl) were injected and measured by UV/Vis absorption at 338 nm. Calibration curves were constructed with authentic GSNO (0.1–2 µM) in sample buffer.

Curve fitting

Concentration-dependent effects on rates and yields were routinely fitted to appropriate linear or hyperbolic functions as detailed in the legend to each figure. These fits are purely empirical, with EC50 values representing the concentrations of the agents that cause half-maximal effects. Physical interpretations of the fitting parameters, if any, are given under Discussion.

Results

Effect of Mg2+ on GSNO formation from nitric oxide and GSH

Injection of 1 µM PROLI/NO into a reaction mixture containing 1000 U/ml SOD, 5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 mM DTPA in 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) gave rise to a strong signal at the NO-sensitive electrode peaking at approximately 1.2 µM, which was followed by single-exponential decay back to baseline (not shown), caused primarily by escape of NO into the atmosphere [24]. When 2 mM GSH was added at the time when the NO concentration had dropped to 0.75 µM NO, NO decay was markedly accelerated, indicative of a direct reaction between GSH and NO ( Fig. 2). Addition of 4 mM CuSO4 to the sample after NO had disappeared gave rise to a peak of ~0.5 µM NO, suggesting that GSNO had formed. Comparison with authentic GSNO yielded a GSNO concentration of ~0.68 µM, corresponding to a nitrosation yield of ~91%.

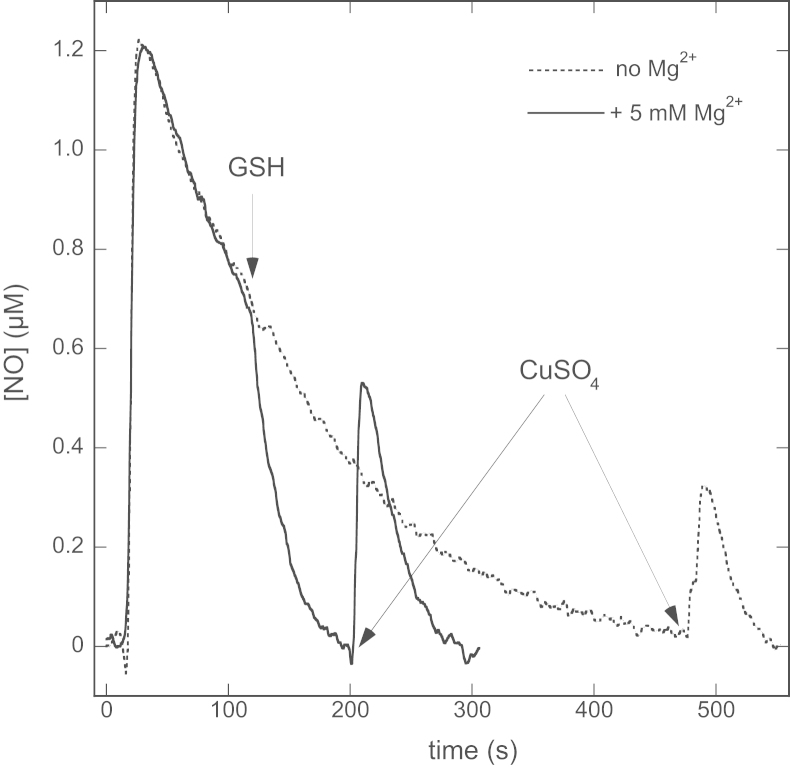

Fig. 2.

Effect of GSH on the NO release curves from PROLI/NO in the absence and presence of 5 mM MgCl2 before and after addition of CuSO4. Shown are the [NO]-progress curves from PROLI/NO added at the start of the trace. When free NO had declined to 0.75 µM, 2 mM GSH was added to the solution. CuSO4 was added after all the NO had disappeared. The times of addition of GSH and CuSO4 are indicated by arrows. Experimental conditions: 1 µM PROLI/NO, 2 mM GSH, 4 mM CuSO4, 1000 U/ml SOD, 0.1 mM DTPA, 0 (dotted line) or 5 (continuous line) mM MgCl2, and 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) at 37 °C.

In contrast, GSH hardly affected the NO decay rate in the absence of Mg2+, suggesting a much slower reaction between GSH and NO. Omission of Mg2+ also diminished the height of the Cu2+-induced NO peak to ~0.25 µM, corresponding to a GSNO concentration of ~0.33 µM, or a nitrosation yield of ~44%.

Detection of GSNO formation with alternative methods

To corroborate the results obtained with the NO electrode, we determined GSNO formation with two additional established methods. In both cases the experimental procedure was the same as described above. However, after the NO had disappeared, the samples were removed from the NO electrode to be measured by HPLC or the NO analyzer. As shown in Table 1, very similar results were obtained with all three methods.

Table 1.

Comparison of GSNO yields determined by various methods.

| Method | GSNO (µM) |

|

|---|---|---|

| +Mg2+ | −Mg2+ | |

| Electrode | 0.76±0.02 | 0.37±0.03 |

| NO analyzer | 0.75±0.03 | 0.35±0.04 |

| HPLC | 0.70±0.05 | 0.29±0.04 |

Experimental conditions: 1 µM PROLI/NO (~0.75 µM NO), 5 mM GSH, 1000 U/ml SOD, 0.1 mM DTPA, 5 mM MgCl2 as indicated, and 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) in 0.5 ml at 37 °C. Data are shown ±SEM (n=3–5).

Effects of GSH concentration on NO consumption and GSNO formation

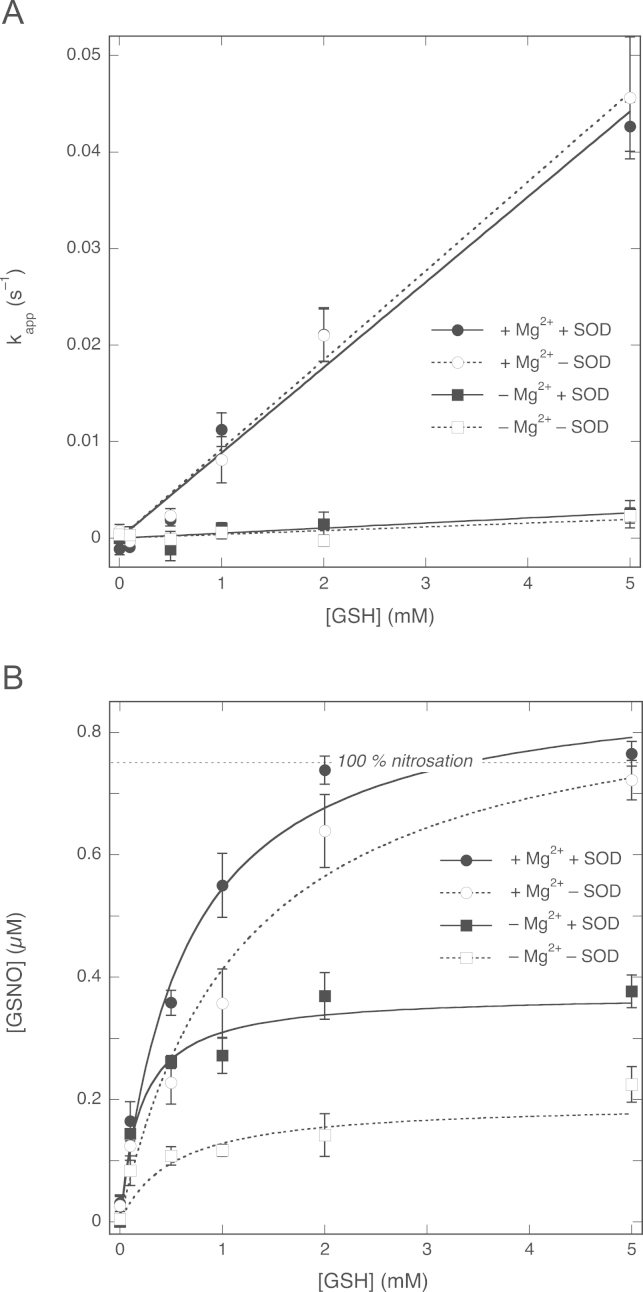

Next we investigated the effects of the GSH concentration on the rate of NO decay and GSNO formation. We determined pseudo-first-order rate constants for the reaction between NO and GSH by dividing the difference between the NO decay rates immediately before and after GSH addition by the NO concentration at the time of GSH addition. In Fig. 3A these apparent rate constants are plotted against the concentration of GSH, showing a linear increase in the rate of NO decay in the presence of Mg2+ in line with direct consumption of NO by GSH; a much smaller increase was observed in the absence of Mg2+. From the slopes of the plots, second-order rate constants of 8.8±0.4 and 0.52±0.13 M−1 s−1 in the presence and absence of Mg2+, respectively, were calculated. The former value is somewhat lower than our previous estimate of 34±6 M−1 s−1 (Fig. 9 of Ref. [24]), but in fair agreement with two other estimates from the same study (~5–15 M−1 s−1 on page 63 and 13.6 M−1 s−1 from Supplementary Figure S9 [24]).

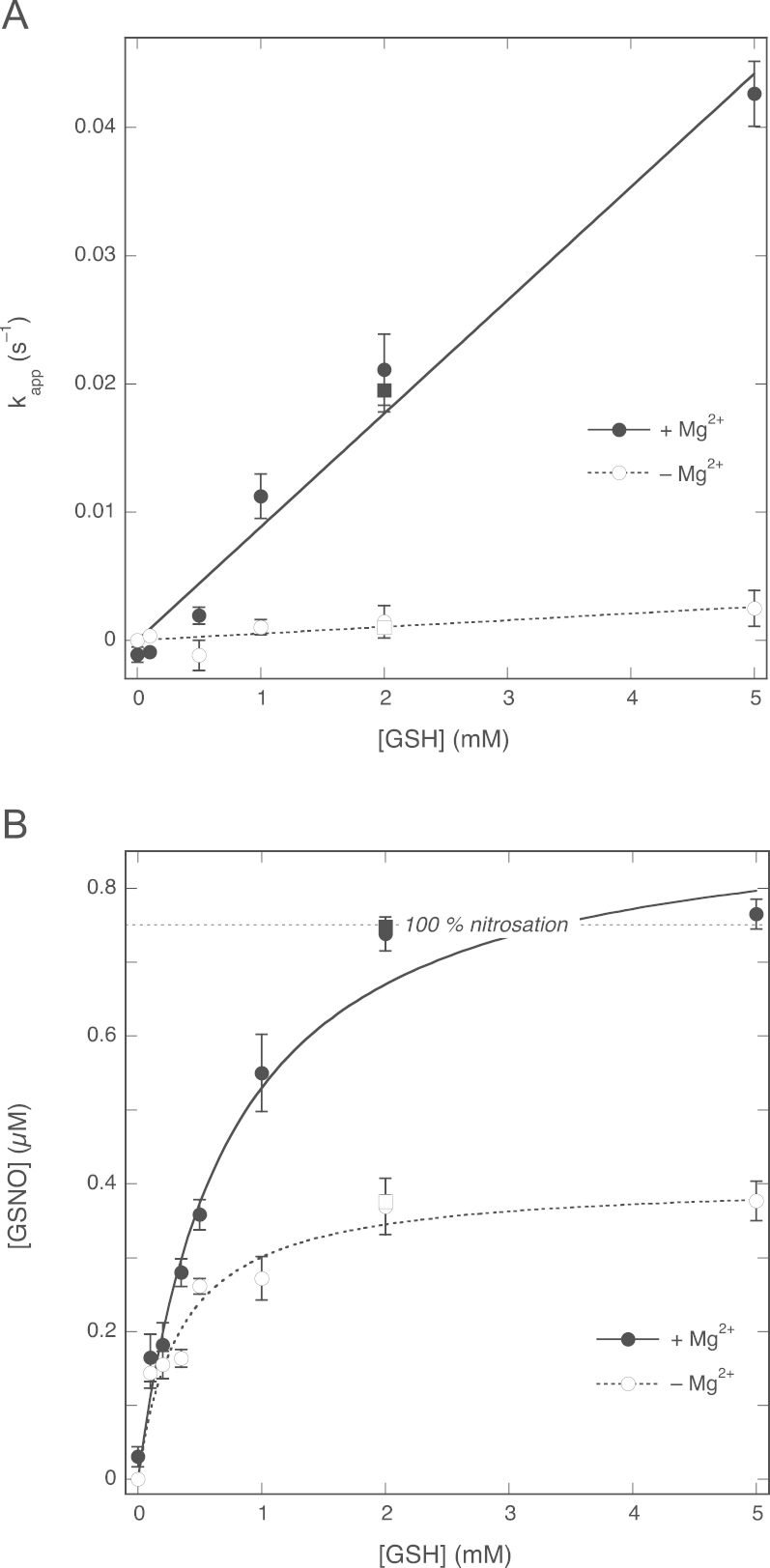

Fig. 3.

Effects of GSH concentration on the NO decay rate and the GSNO yield in the absence and presence of 5 mM MgCl2. (A) Apparent pseudo-first-order rate constants (observed at 0.75 µM NO) as a function of the GSH concentration. The lines are best linear fits (y=ax), with fitting parameters a, representing the apparent second-order rate constants for the reaction between NO and GSH, of 8.8±0.4 M−1 s−1 (R=0.989) and 0.52±0.13 M−1 s−1 (R=0.82) in the presence and absence of Mg2+, respectively. (B) GSNO yields measured as NO released after injection of CuSO4. The lines through the data points are best fits to the hyperbola y=bx/(a+x), with a and b representing the EC50 for GSH and the maximal yield of GSNO, respectively. Fitting parameters: in the presence of Mg2+, EC50 0.72±0.06 mM, [GSNO]max 0.91±0.03 µM (R=0.992); in the absence of Mg2+, EC50 0.34±0.06 mM, [GSNO]max 0.40±0.03 µM (R=0.991). Experimental conditions: 1 µM PROLI/NO, varying concentrations of GSH (0.1–5 mM), 4 mM CuSO4, 1000 U/ml SOD, 0.1 mM DTPA, 0 (white circles, dotted line) or 5 (black circles, continuous line) mM MgCl2, and 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. Also included are the results obtained for 2 mM GSH with authentic NO (0.75 mM) in the absence (white squares) and presence (black squares) of 5 mM MgCl2. Data are shown ±SEM (n=5).

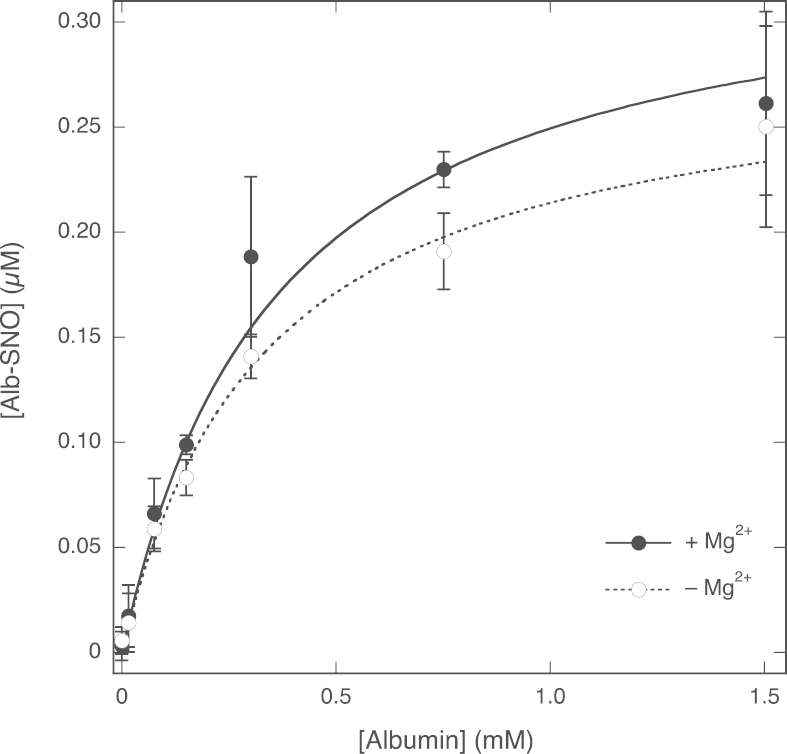

Fig. 9.

Effect of the concentration of albumin on Alb-SNO formation. PROLI/NO was added to samples with varying concentrations of albumin with and without 5 mM Mg2+. Plotted are the yields of Alb-SNO after 10 min incubation, as determined with the NO analyzer. The lines through the data points are best fits to the hyperbola y=bx/(a+x), with a and b representing the EC50 for albumin and the maximal yield of GSNO, respectively. Fitting parameters: in the presence of Mg2+, EC50 0.36±0.05 mM, [GSNO]max 0.34±0.03 µM (R=0.999); in the absence of Mg2+, EC50 0.33±0.09 mM, [GSNO]max 0.28±0.04 µM (R=0.995). Experimental conditions: 1 µM PROLI/NO, varying concentrations of albumin (Sigma–Aldrich No. A7906, 0–1.5 mM), 1000 U/ml SOD, 0.1 mM DTPA, 0 (white circles) or 5 (black circles) mM MgCl2, and 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. Data are shown ±SEM (n=3).

Fig. 3B shows the effect of the GSH concentration in the absence and presence of Mg2+ on the GSNO yield. Increasing the GSH concentration in the presence of Mg2+ gradually resulted in complete conversion of NO to GSNO with an EC50 ~0.72±0.06 mM. Assuming simple competition between NO escape and GSH nitrosation and a rate constant for NO decay in the absence of GSH of ~6.4×10−3 s−1 (results not shown), one can calculate a rate constant for the reaction between GSH and NO of ~8.9 M−1 s−1, in excellent agreement with the value derived from Fig. 3A.

In the absence of Mg2+ the EC50 for GSH was lower (0.34±0.06 mM) and the maximal yield of GSNO was 0.40±0.03 µM, only about half of that observed in the presence of Mg2+. Simple competition between NO escape and nitrosation should result in complete conversion of NO into GSNO at saturating concentrations of GSH (Model A in Scheme 1, see Discussion). Consequently, whereas simple competition can explain the observations in the presence of Mg2+, it fails to do so in the absence of Mg2+.

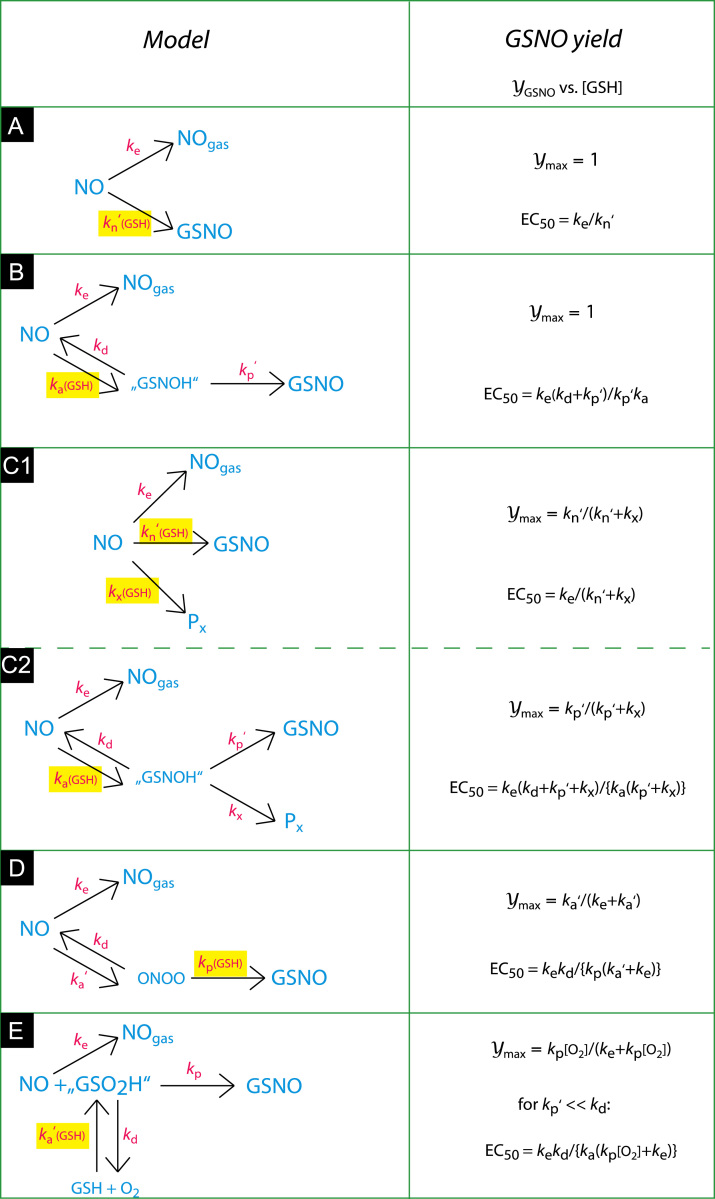

Scheme 1.

Predicted [GSH] dependencies of GSNO yields for several simple mechanisms of GSH nitrosation by NO/O2. Model A assumes competition between NO escape and GSNO formation by NO, O2, and GSH, represented in a single step. Because only the latter reaction is [GSH]-dependent, the GSNO yield will approach 100% as a function of the GSH concentration (Ymax=1). The yield will be half-maximal when the rates of NO escape and GSNO formation are equal (ke=kn′[GSH], with the O2 concentration already incorporated into the apparent second-order rate constant kn′). Accordingly, the concentration of GSH producing half-maximal yields (EC50) will be ke/kn′. Models B, D, and E elaborate Model A to a two-step mechanism with NO and GSH, NO and O2, and O2 and GSH reacting first, respectively. For Model B (initial reaction between NO and GSH) the maximal yield is still 100%, because it is determined by competition between [GSH]-independent NO escape and [GSH]-dependent "GSNOH" formation. For Model D (initial reaction between NO and O2) the maximal yield will be determined by competition between NO escape and "ONOO" formation. Because neither reaction is [GSH]-dependent, the maximal yield will be <100% with Ymax=ka′/(ka′+ke). For Model E (initial reaction between O2 and GSH) the yield will be determined by competition between NO escape and the reaction between NO and “GSO2H". Because the latter rate is limited by the O2 concentration ([GSO2H]max ≤[O2]0), the maximal yield will be <100% with Ymax=kp[O2]/(kp[O2]+ke). Models C1 and C2 are extensions of Models A and B assuming hypothetical reactions resulting in unspecified alternative products Px. Both models yield maximal yields <100% (determined by competition between two [GSH]-dependent reactions for Model C1 and between two [GSH]-independent reactions for Model C2) that are independent of the rate of NO escape. Reactions involving GSH are highlighted in yellow. Reactions involving O2 (not explicitly shown in Models A through D) are characterized by primed (apparent) rate constants.

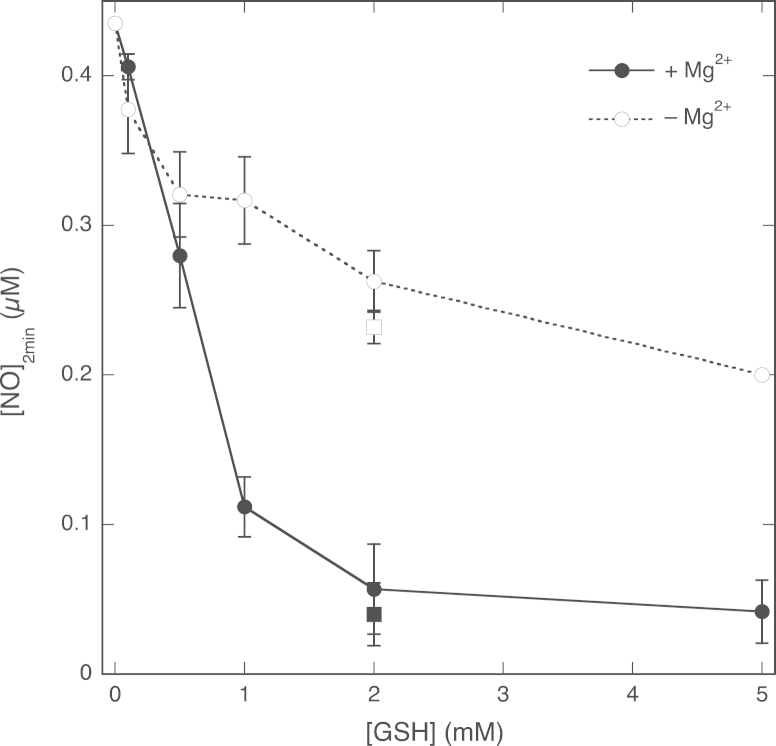

The lack of an effect of GSH on the NO decay rate in the absence of Mg2+ would suggest that there is no direct reaction between GSH and NO under those conditions, although significant amounts of GSNO were formed. To investigate this apparent discrepancy, we determined the concentration of NO that remained 2 min after the start of the reaction as a function of the GSH concentration (see Supplementary Fig. S1). The rationale behind this experiment was that even small increases in the rate of NO decay should result in considerably lower NO levels after that time. Fig. 4 shows that, as expected, very little NO remained 2 min after addition of 2 mM GSH (or higher) in the presence of Mg2+. However, GSH attenuated the NO concentration in the absence of Mg2+ as well (from 0.43 µM in the absence to 0.20 µM in the presence of 5 mM GSH). These results demonstrate that in the absence of Mg2+ a direct reaction between NO and GSH still occurs, but with a rate constant that is too low to cause a clear change in the NO decay rate.

Fig. 4.

Effect of the GSH concentration on the NO concentration 2 min after injection of GSH. The concentration of NO remaining 2 min after GSH addition (see also Supplementary Fig. S1) in the absence and presence of 5 mM MgCl2 is plotted against the GSH concentration. Experimental conditions: 1 µM PROLI/NO, varying concentrations of GSH (0.1–5 mM), 1000 U/ml SOD, 0.1 mM DTPA, 0 (white circles, dotted line) or 5 (black circles, continuous line) mM MgCl2, and 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) in 0.5 ml at 37 °C. Also included are the results obtained for 2 mM GSH with authentic NO (0.75 mM) in the absence (white square) and presence (black square) of 5 mM MgCl2. Data are shown ±SEM (n=5).

Effect of the rate of NO release on the yield of GSNO

To evaluate the contribution of autoxidation-mediated processes to the nitrosation of GSH, we compared GSNO yields obtained with equal concentrations of the rapid, medium, and slow NO-releasing compounds PROLI/NO, DEA/NO, and SPER/NO (t 1/2~39 min at 37 °C and pH 7.4 [31]). As discussed previously [24], autoxidation-mediated nitrosation is expected to diminish in the case of a slow-releasing donor because of the second-order dependence of autoxidation on the NO concentration. The results, presented in Table 2, show that nitrosation actually became more efficient with the slow-releasing donor, which argues strongly against a role for autoxidation in the process.

Table 2.

Yields of GSNO from the reaction of GSH and various NO donors.

| Donora (1 µM) | t1/2 (s) | Pre-Cu2+ NO peak (µM) | GSNO (µM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −Mg2+ | +Mg2+ | |||

| SPER/NO | 1806±6 | n.d. | 0.89±0.05 (~56%) | 1.19±0.09 (~74%) |

| DEA/NO | 67±3 | 0.70±0.03 | 0.47±0.05 (~32%) | 0.94±0.14 (~65%) |

| PROLI/NO | 1–2 | 1.21±0.02 | 0.38±0.01 (~25%) | 0.86±0.15 (~57%) |

Experimental conditions: 1 µM SPER/NO, DEA/NO, or PROLI/NO; 1 mM GSH; 1000 U/ml SOD; 0.1 mM DTPA; 0 or 5 mM MgCl2; and 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) in 0.5 ml at 37 °C.

SPER/NO, DEA/NO, and PROLI/NO released 1.60±0.03, 1.46±0.02, and 1.52±0.06 µM NO under the conditions used as determined by the conversion of oxyhemoglobin to methemoglobin. n.d.: not detectable. Data are shown ±SEM (n=5–7).

We also performed several experiments with authentic NO. The results, included in Fig. 3, Fig. 4 (black and white squares) were virtually indiscernible from those obtained with PROLI/NO.

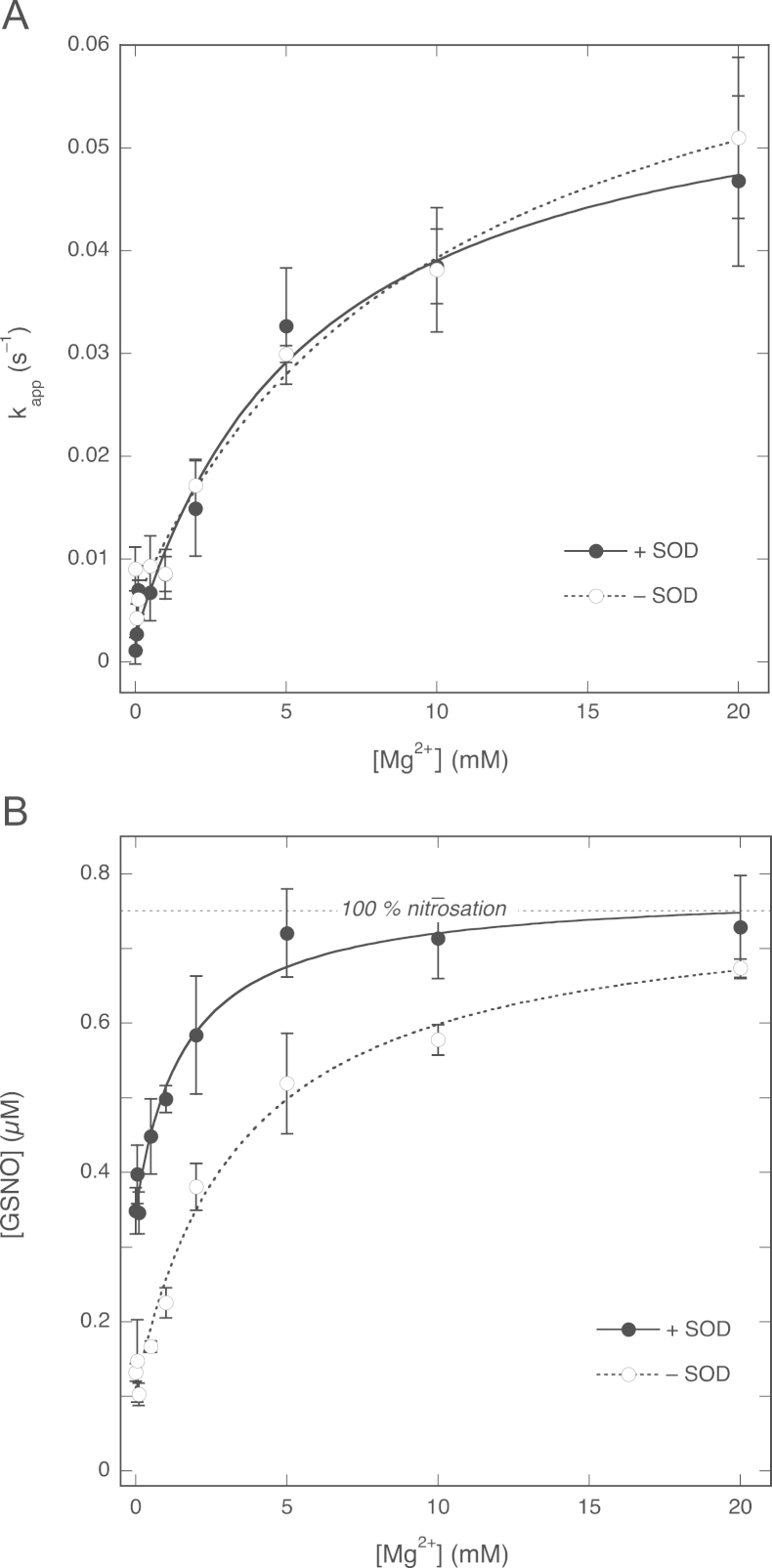

Effect of the Mg2+ concentration on GSNO formation

As illustrated by Fig. 5A, Mg2+ caused a concentration-dependent increase in the rate of NO decay that could be fit to a hyperbola, indicating that, at a concentration of 2 mM GSH, the stimulation by Mg2+ approaches a limiting value with a EC50 ~5.9±1.6 mM and a maximal pseudo-first-order rate constant of (6.1±0.6)×10−2 s−1, with this value corresponding to an apparent second-order rate constant of 30±3 M−1 s−1. The results also suggest a direct reaction between NO and GSH in the absence of Mg2+ with a rate of (2.4±1.4)×10−3 s−1, corresponding to an apparent rate constant of 1.2±0.7 M−1 s−1. As shown in Fig. 5B, the yield of GSNO also increased with the Mg2+ concentration from 0.349±0.018 µM (47±2%) to 0.78±0.03 µM (104±4%), in line with the results presented in Fig. 3B.

Fig. 5.

Effects of the Mg2+ concentration on NO decay and GSNO formation. (A) Apparent pseudo-first-order rate constants for NO decay as a function of the Mg2+ concentration. The lines through the data points are best fits to the hyperbola y=b+(c − b)×x/(a+x), where a represents the EC50 for Mg2+ and b and c are the apparent first-order rate constants in the absence and presence of (saturating) Mg2+, respectively. Fitting parameters: in the presence of SOD, EC50 5.9±1.6 mM, kapp(−)=(2.4±1.4)×10−3 s−1, kapp(+)=(6.1±0.6)×10−2 s−1 (R=0.992); in the absence of SOD, EC50 10±3 mM, kapp(−)=(5.7±1.2)×10−3 s−1, kapp(+)=(7.4±0.9)×10−2 s−1 (R=0.993). (B) GSNO yield as a function of the Mg2+ concentration in the presence and absence of SOD. The results were fitted to the same hyperbolic function as in (A). Fitting parameters: in the presence of SOD, EC50 1.6±0.4 mM, [GSNO](−) 0.349±0.018 µM, [GSNO](+) 0.78±0.03 µM (R=0.988); in the absence of SOD, EC50 3.5±0.8 mM, [GSNO](−) 0.110±0.017 µM, [GSNO](+) 0.77±0.05 µM (R=0.993). Experimental conditions: 1 µM PROLI/NO, 2 mM GSH, 4 mM CuSO4, 0 (white circles) or 1000 (black circles) U/ml SOD, 0.1 mM DTPA, MgCl2 as indicated, and 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. Data are shown ±SEM (n=3).

Effect of SOD on NO decay and GSNO formation

To evaluate the role of superoxide, we carried out some experiments in the absence of SOD. Omission of SOD did not affect the rate of NO decay at any concentration of Mg2+ (Fig. 5A). However, the GSNO yield in the absence of Mg2+ was diminished to 0.110±0.017 µM (15±2% conversion, Fig. 5B). Complete conversion of NO to GSNO was still attained at saturating Mg2+ concentrations, but required more Mg2+ (≥20 mM instead of ~5 mM).

Plots of the apparent rate constant for NO consumption as a function of the GSH concentration confirmed the absence of an effect of SOD on the NO decay rate ( Fig. 6A). There was also no effect of SOD on the NO concentration that remained 2 min after GSH addition (Supplementary Fig. 2). GSNO yields, on the other hand, were consistently lower in the absence of SOD (Fig. 6B). In the presence of Mg2+ this effect disappeared at high GSH concentrations (≥5 mM); under these conditions complete conversion of NO to GSNO was observed both in the absence and in the presence of SOD. In the absence of Mg2+, however, the maximal yield reached was only 0.19±0.03 µM, approximately half of that observed when SOD was present.

Fig. 6.

Effect of SOD on the [GSH] dependence of NO decay rate and GSNO formation. (A) Apparent pseudo-first-order rate constants as a function of the GSH concentration. The lines through the data points are best linear fits (y=ax) with a representing the apparent second-order rate constant. Fitting parameters: +Mg2+, +SOD, 8.8±0.4 M−1 s−1 (R=0.989); +Mg2+, −SOD, 9.2±0.3 M−1 s−1 (R=0.995); −Mg2+, +SOD, 0.52±0.13 M−1 s−1 (R=0.82); −Mg2+, −SOD, 0.39±0.10 M−1 s−1 (R=0.80). (B) GSNO yields for varying concentrations of GSH. The lines through the data points are best fits to the hyperbola y=bx/(a+x), where a represents the EC50 for GSH and b the maximal GSNO yield. Fitting parameters: +Mg2+, +SOD, EC50 0.64±0.08 mM, [GSNO]max 0.89±0.03 µM (R=0.993); +Mg2+, −SOD, EC50 1.2±0.2 mM, [GSNO]max 0.90±0.06 µM (R=0.987); −Mg2+, +SOD, EC50 0.20±0.05 mM, [GSNO]max 0.37±0.02 µM (R=0.998); −Mg2+, −SOD, EC50 0.5±0.3 mM, [GSNO]max 0.19±0.03 µM (R=0.973). Experimental conditions: 1 µM PROLI/NO, GSH as indicated, 4 mM CuSO4, 0 (white symbols) or 1000 (black symbols) U/ml SOD, 0.1 mM DTPA, 0 (squares) or 5 (circles) mM MgCl2, and 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. Data in the presence of SOD are from Fig. 3 and included for easier comparison. Data are shown ±SEM (n=5).

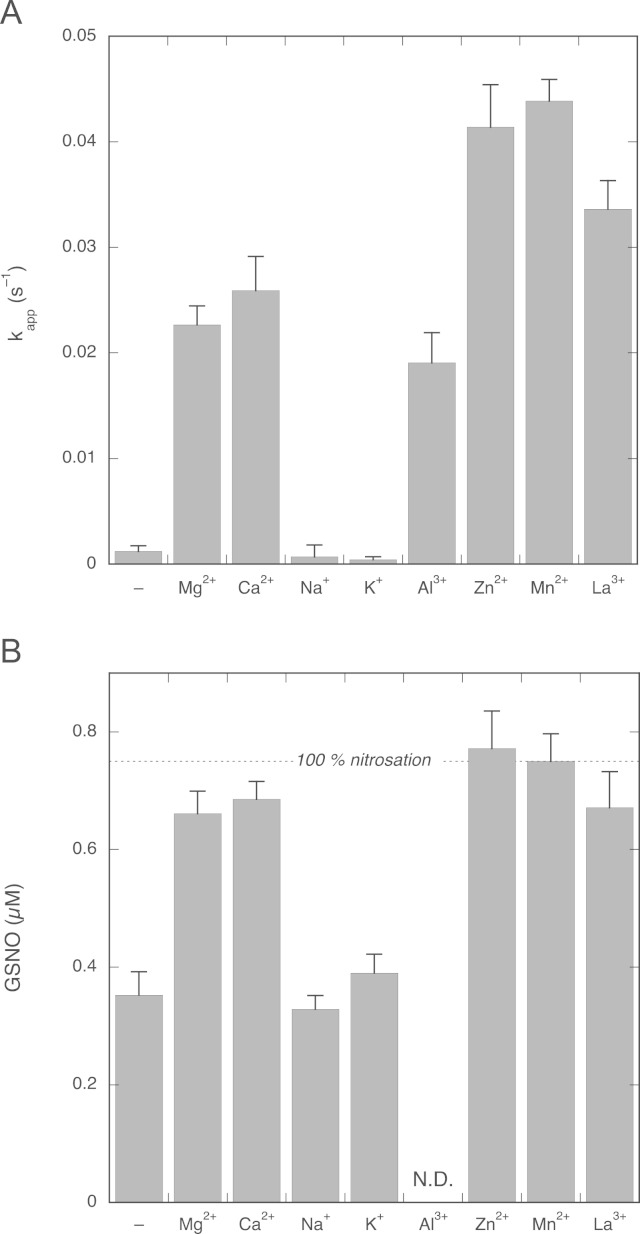

Effects of other cations on NO decay and nitrosothiol formation

In Fig. 7 the effects of Mg2+, Ca2+, and several other cations on the rate of NO decay and the GSNO yield are compared. As illustrated by Fig. 7A, all investigated divalent cations stimulated NO consumption by GSH; Mg2+ and Ca2+ afforded virtually identical apparent rate constants (0.0227±0.0018 and 0.026±0.003 s−1, respectively), whereas somewhat higher rate constants were observed for the divalent transition metals Zn2+ and Mn2+ (0.041±0.004 and 0.044±0.002 s−1, respectively). By contrast, the monovalent cations Na+ and K+ had no effect. The trivalent cations Al3+ and La3+ also stimulated NO consumption.

Fig. 7.

Effects of various cations on NO decay rate and GSNO yield. (A) Apparent pseudo-first-order rate constants in the absence and presence of various cations. (B) Corresponding GSNO yields from 0.75 µM NO and 2 mM GSH. Experimental conditions: 1 µM PROLI/NO, 2 mM GSH, 4 mM CuSO4, 1000 U/ml SOD, 0.1 mM DTPA, 5 mM indicated cation, and 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. N.D., the yield in the presence of Al3+ could not be determined, as Al3+ also stimulated GSNO formation from GSH and nitrite. Data are shown ±SEM (n=5).

Fig. 7B shows the corresponding GSNO yields. In the absence of cations 0.35±0.04 ∝M GSNO was formed from 0.75 µM NO and 2 mM GSH, and similar yields were obtained in the presence of 5 mM Na+ or K+ (0.33±0.02 and 0.39±0.03 µM, respectively). In the presence of the di- and trivalent cations the stimulation of the reaction between NO and GSH resulted in almost complete conversion to GSNO, with yields ranging from 0.66±0.04 to 0.77±0.06 µM (from 88±5 to 103±8%; for Al3+ the nitrosation yield could not be determined).

In the experiments of Fig. 7 the cation concentration was fixed at 5 mM. For Mg2+ and Ca2+ the NO decay rate and the corresponding GSNO yield were also determined for other cation concentrations between 0.1 and 20 mM (Supplementary Fig. 3). The results show that the effects of Mg2+ and Ca2+ were virtually identical at all concentrations tested.

Influence of DTPA

To preclude complications by the inadvertent presence of trace metals, 0.1 mM DTPA was included in all experiments. To assess how this affected the results we performed control experiments in the absence of DTPA, as well as in the presence of 5 mM DTPA (Supplementary Fig. 4). Omission of DTPA resulted in strong stimulation of NO consumption by GSH already in the absence of Mg2+ (k app~0.04 s−1) and an even faster consumption (k app~0.06 s−1) in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+, in both cases accompanied by high GSNO yields (~86 and ~92%, respectively). These observations demonstrate that trace metals are present in our reaction mixture, which without proper chelation will catalyze direct GSH nitrosation by NO, and they suggest that the effects of these trace metals and Mg2+ are additive. By contrast, when the DTPA concentration was increased to 5 mM, no stimulation of NO consumption was apparent even in the presence of 2 mM Mg2+, and GSNO yields (~39 and ~42% in the absence and presence of 2 mM Mg2+, respectively) were similar to those obtained without Mg2+ in the presence of 0.1 mM DTPA (~49%), demonstrating that chelation by DTPA blocks the effects of Mg2+ on NO consumption and GSNO formation.

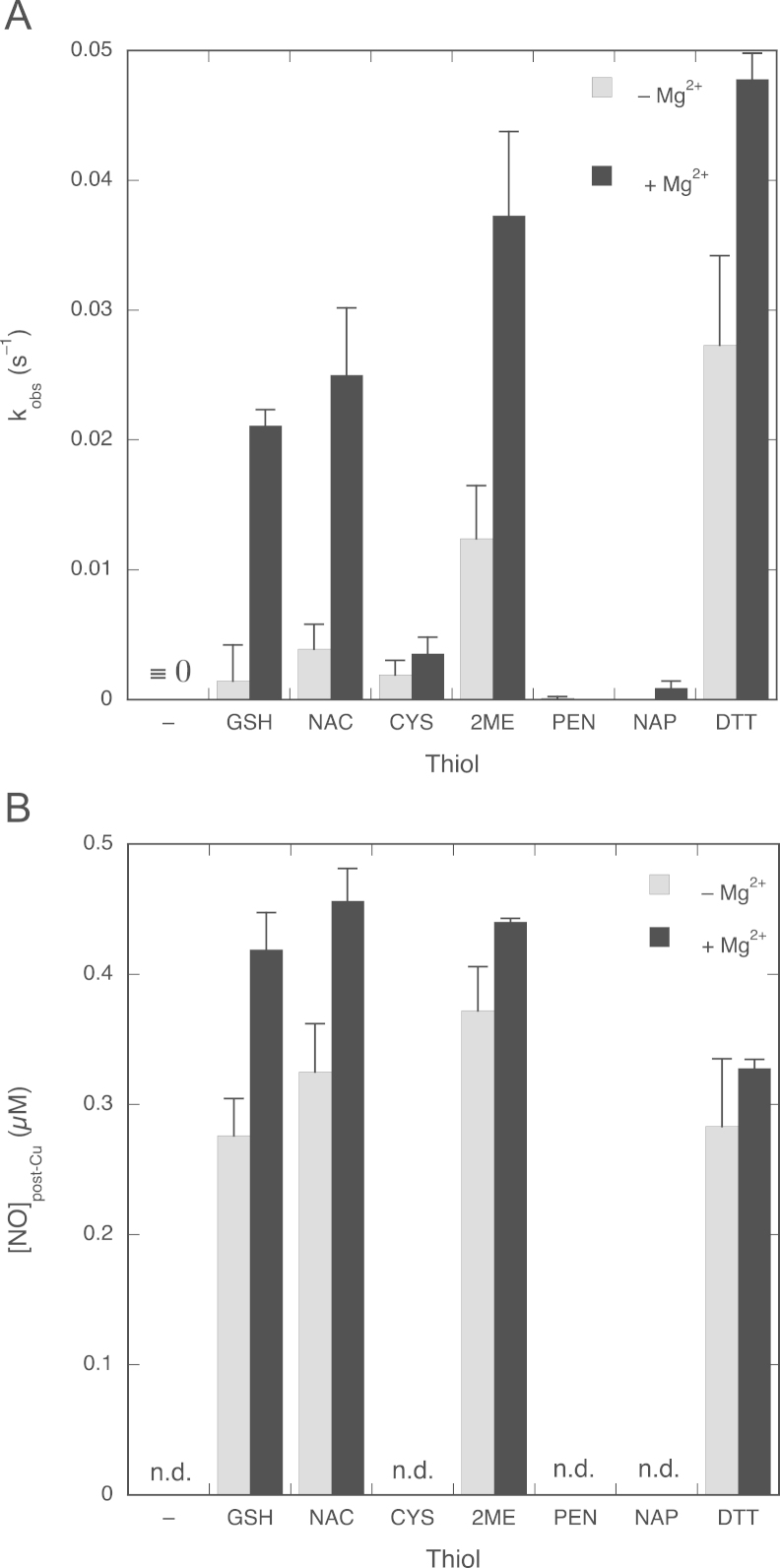

Nitrosation of alternative thiols

Fig. 8A compares the apparent NO decay rate constants with and without Mg2+ for various thiols (structures in Fig. 1). It shows that NAC behaved quite similar to GSH. As with GSH, Mg2+ (5 mM) dramatically increased the apparent first-order rate constants at 2 mM NAC from (3.9±1.9)×10−3 to (2.5±0.5)×10−2 s−1. In addition, the nitrosation yield was significantly increased, reflected in enhanced Cu2+-induced NO release (from 0.33±0.04 to 0.46±0.02 µM). Unlike GSH and NAC, 2-ME and DTT had pronounced effects on the NO decay rate in the absence of Mg2+, with apparent rate constants of (12±4)×10−3 and (27±7)×10−3 s−1, respectively; NO decay in the presence of Mg2+ was also faster, with apparent rate constants of (3.7±0.7)×10−2 and (4.8±0.2)×10−2 s−1 for 2-ME and DTT. Cys, PEN, and NAP, on the other hand, hardly affected NO decay even in the presence of Mg2+. In addition, no nitrosothiol formation was observed with these thiols (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Apparent rate constants for NO decay and yields of nitrosation for various thiols. (A) Apparent pseudo-first-order rate constants with and without 5 mM Mg2+. (B) Nitrosothiol yields from the reaction of 0.75 µM NO and various thiols (2 mM). Shown from left to right are −, no thiol added; GSH, glutathione; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; CYS, cysteine; 2ME, 2-mercaptoethanol; PEN, penicillamine; NAP, N-acetylpenicillamine; DTT, dithiothreitol. Experimental conditions: 1 µM PROLI/NO, 4 mM CuSO4, 1000 U/ml SOD, 0.1 mM DTPA, 2 mM indicated thiol, 0 or 5 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM TEA (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. n.d., not detectable. Data are shown ±SEM (n=3 to 5).

We also compared the effects of the various thiols on the NO concentration 2 min after thiol addition (Supplementary Fig. 5). The results demonstrate that in the absence of Mg2+ all thiols react with NO, with the reactivity decreasing in the order 2-ME≈DTT>GSH≈Cys≈NAC≥PEN≈NAP. Although Mg2+ appears to stimulate the reaction for all thiols, the extent of stimulation differs considerably: for GSH and NAC, for instance, stimulation by Mg2+ is much more pronounced than for Cys (Supplementary Fig. 5).

S-nitrosation of albumin

Whereas cells contain millimolar concentrations of GSH, albumin is the main thiol in plasma (~0.5–0.75 mM). To examine if direct nitrosation might be relevant in the circulation, we investigated the reaction between albumin and PROLI/NO-derived NO. Albumin (1.5 mM), added before PROLI/NO, moderately lowered the NO peak height from 1.198±0.009 to 1.06±0.12 µM in the absence and to 0.923±0.016 µM in the presence of Mg2+ (not shown). The NO concentration 2 min after PROLI/NO addition also decreased from 0.70±0.02 to 0.44±0.06 µM and 0.36±0.04 µM in the absence and presence of Mg2+, respectively (not shown).

Fig. 9 shows that the yield of Alb-SNO for 1 µM PROLI/NO increased with the albumin concentration. The highest observed yields (at 1.5 mM albumin) were 0.26±0.04 and 0.25±0.05 µM with and without 5 mM Mg2+, respectively, and the estimated maximal yields at saturating concentrations of albumin were 0.34±0.03 and 0.28±0.04 µM, respectively. Virtually identical results were obtained when a different commercial preparation of albumin (Sigma–Aldrich No. A5470 instead of A7906) was used (not shown). These results indicate that direct nitrosation of albumin by NO does occur, albeit with lower efficiency than was found for GSH, and without appreciable stimulation by Mg2+.

Discussion

No role for NO autoxidation in GSNO formation at submicromolar [NO]

Recently, we reported that at submicromolar concentrations NO efficiently nitrosates GSH in a direct reaction, rather than via NO autoxidation [24]. Whereas in most of the experiments in that study GSH was present in the reaction mixture before DEA/NO addition, we used PROLI/NO (1 µM) as the NO source in the present study, and we added GSH after the NO concentration had peaked and decreased to ~0.75 µM. Because PROLI/NO has a short half-life (1.8 s [27]), the donor had completely decayed at that time (~120 s), allowing the examination of GSH addition on the NO decay kinetics without interference from continued NO release.

The linear increase in the NO decay rate with the GSH concentration implies a direct reaction between GSH and NO, as the rate of autoxidation-mediated nitrosation should not be affected by GSH. Furthermore, NO autoxidation is expected to be far slower than the observed NO disappearance in the absence of GSH, which is primarily due to escape of NO into the atmosphere (see the simulations in Supplementary Fig. S6). Moreover, NO decayed monoexponentially before and after GSH addition with no sign of second-order kinetics (Supplementary Fig. S7). Finally, in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+ we observed complete conversion of NO to GSNO at saturating GSH concentrations (Fig. 3B), which is twice the theoretical maximal yield for autoxidation-mediated nitrosation (see Eq. (7)):

| 2NO+½O2+GSH →→ GSNO+H++NO2−. | (7) |

As a further test to look into the contribution of autoxidation, we compared the nitrosation yields for equal concentrations (1 µM) of PROLI/NO, DEA/NO, and SPER/NO, which release NO with half-lives of 1–2, 67, and 1800 s, respectively. If autoxidation were involved in GSNO formation, the yield should be highest for PROLI/NO and lowest for SPER/NO, because the peak level of [NO] increases with the rate of NO release, which will favor the second-order process of autoxidation. However, we observed the opposite effect, with nitrosation being most efficient for SPER/NO. This can be explained by the greater impact of autoxidation for the rapid NO-releasing compound PROLI/NO, because under the conditions investigated ([NO] ≪ [GSH]) autoxidation will almost exclusively yield glutathione disulfide and hardly any GSNO [24]. Consequently, a shift away from autoxidation, as occurs when going from PROLI/NO to DEA/NO to SPER/NO, is expected to increase the nitrosation yield.

To estimate under which conditions the direct reaction studied here will take over from the more familiar autoxidation-mediated process, one may compare the respective rates, which are v aut=k aut•[NO]2•[O2] and (probably) v dir=k dir•[NO]•[O2]•[GSH], for the autoxidation-mediated and direct reactions, respectively. The concentrations of NO and GSH at which both reactions contribute equally will therefore be determined by the equality k aut•[NO]=k dir•[GSH], with k aut=6.8×106 M−2 s−1 (for 2 GSNO formed from 4 NO) and k dir=4×104 M−2 s−1 (in the presence of Mg2+). Consequently, for 0.1 ∝M NO the rates of autoxidation and direct nitrosation would be equal at 17 µM GSH. In the absence of Mg2+, the corresponding GSH concentration would still be only ~0.3 mM. These estimations highlight the potential relevance of the direct reaction at physiological NO concentrations.

Taken together, the results of the present study (Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figs. S6 and S7) provide evidence for a direct reaction between GSH and NO both in the absence and in the presence of Mg2+ with apparent rate constants of 8.8±0.4 and 0.52±0.13 M−1 s−1, respectively. Consequently, Mg2+ stimulates the direct reaction between GSH and NO ~17±4-fold.

Mechanistic considerations

Because NO autoxidation is too slow to play a significant role in the submicromolar NO concentration range, close to 100% nitrosation yields (~0.75 µM GSNO) are to be expected in a closed system. However, by allowing NO to escape from the solution, we introduced a competing reaction in our system and, consequently, a [GSH]-dependent GSNO yield. The fractional nitrosation yield (Y with values between 0 and 1) will then be determined by the relative rates of NO escape (v e) and GSH nitrosation (v n) according to Y=v n/(v n+v e). In the case of simple competition, i.e., in a system in which NO escape and nitrosation are both treated as single-step reactions (Scheme 1A), the fractional yield Y will depend on the GSH concentration according to Y=[GSH]/([GSH]+k e/k n′), yielding a hyperbola with Y max=1 and EC50 k e/k n′ (with k e and k n′ representing the rate constant for NO escape and the apparent [O2]-dependent rate constant for nitrosation, respectively). Consequently, maximal yields should still be 100%.

Whereas complete conversion of NO into GSNO was observed in the presence of Mg2+, this was not the case in the absence of Mg2+ (Figs. 3B and 6B). This observation rules out simple competition between NO escape and nitrosation (Scheme 1A) or the more realistic mechanism illustrated by Scheme 1B, in which the reaction between NO and GSH is followed by [GSH]-independent GSNO formation, because both mechanisms predict 100% conversion for infinite [GSH] (see Supplementary Fig. S8).

Incomplete conversion at saturating [GSH] would arise if products other than GSNO were formed from the reaction between NO and GSH (Scheme 1C). In that case the maximal yield of GSNO would be determined by the relative rates at which GSNO and the alternative products are formed and should therefore be independent of the rate of NO escape. However, we found that the maximal yield increased when escape to solution was impeded: when we increased the reaction volume from 0.5 to 2.0 ml and closed the vessel, the maximal yield in the absence of Mg2+ increased from 46±4 to 78±7% (0.75 µM PROLI/NO-derived NO, 5 mM GSH, results not shown). Consequently, Models C1 and C2 (Scheme 1) do not fit the observations.

Alternatively, the reaction may involve a [GSH]-independent step or equilibrium, followed by [GSH]-dependent nitrosothiol formation (Scheme 1D, Supplementary Fig. S8). In this case the maximal yield will be determined by the relative magnitudes of the rate constants for NO escape (k e) and intermediate/complex formation (k a′). This model provides an attractive explanation, because GSNO formation is indeed expected to represent a multistep process.

A third possibility that needs to be considered is a reaction between NO and a preformed complex of GSH with O2. This mechanism would result in a maximal GSNO yield that is limited by the O2 concentration (Scheme 1E, Supplementary Fig. S8). However, with EC50=K d•(1 − Y max) (see Scheme 1E), EC50=0.34 mM, and maximal yield Y max=0.40/0.75=0.53 (from Fig. 3B), one can estimate a K d value of ~0.7 mM for the complex between GSH and O2. This would imply that with GSH in the millimolar range virtually all O2 is bound to GSH, which seems unrealistic.

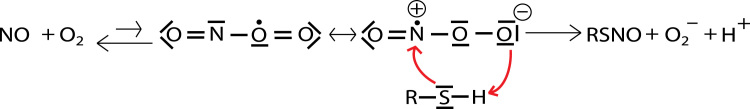

Taken together, the present results strongly suggest that Scheme 1D describes the reaction correctly. Consequently, the reaction does not start with the association of NO and GSH, as was originally proposed [22], but is initiated by the formation of the nitrosyldioxyl radical ONOO•.

The transition toward complete nitrosation in the presence of Mg2+ may be due to an increase in the yield-determining step in the reaction (k n in Scheme 1C1, k p in Scheme 1C2, k a′ in Scheme 1D, k p in Scheme 1E). Alternatively, the mechanism may have changed to that of Scheme 1B, with now GSH and NO reacting first. We routinely fitted all nonlinear results to simple hyperbolae. Essentially, these functions were applied as empirical formulae, but for plots of the GSNO yields vs [GSH], hyperbolic curves are indeed expected for all models discussed above (Scheme 1). However, a closer look at Figs. 3B and 6B suggests that a simple hyperbolic fit is far from perfect for the curves in the presence of Mg2+, because the maximal yields derived from such fits tended to overshoot the level of 100% conversion. This suggests the formation of a complex between GSH and Mg2+ as an initial step in Mg2+-catalyzed nitrosation, because in that case the curving of the plot would become sharper when Mg2+ is present at concentrations above the K d of the Mg2+•GSH complex. We have not been able to find a K d for the Mg2+•GSH complex in the literature, but for the complex with Ca2+, which exhibited virtually identical behavior in the present study and which binds to cysteine with the same affinity as Mg2+ [32], a value of 0.14 mM was reported [33], which would indeed be much lower than the applied Mg2+ concentration of 5 mM. Consequently, we propose that the formation of a Mg2+•GSH complex is an early step in the Mg2+-catalyzed reaction (as opposed to a reaction between GSH and a preformed complex of Mg2+ with NO and/or O2 or between Mg2+ and a preformed complex of GSH with NO and/or O2).

Because the reaction proposed by us results in equimolar formation of GSNO and O2 − (Eq. (6)), omission of SOD was expected to increase the rate of NO decay and to diminish the yield of GSNO by at least 50% because of rapid consumption of NO by the superoxide formed, yielding overall Reaction (8):

| GSH+2NO+O2→GSNO+ONOO−. | (8) |

In the absence of Mg2+ the GSNO yield was indeed decreased by 50% (Fig. 6B); an effect on the NO decay rate could not be verified, as GSH hardly affected the rate in the absence of Mg2+. Surprisingly, however, omission of SOD did not affect the NO decay rate in the presence of Mg2+ (Fig. 6A), nor was the maximal yield of GSNO affected (Fig. 6B). To explain these observations by competition between NO and GSH for O2 −, the reaction between GSH and O2 − should have a rate constant greater than 106 M−1 s−1, whereas values between 102 and 105 M−1 s−1 have been reported [34], [35], which would imply that the Mg2+•GSH complex is far more reactive with O2 − than free GSH. Alternatively, it is conceivable that Mg2+ catalyzes overall Reaction (9), without formation of free O2 −, which would imply recruitment of at least two molecules of GSH, in addition to NO and O2, by the cation:

| GSH+NO+½O2→GSNO+½H2O2. | (9) |

A limitation of the present study is the lack of experiments varying the O2 concentration. We and others previously reported direct nitrosation to be O2-dependent [22], [24], and there seems to be no alternative electron acceptor available in our reaction mixture. Nevertheless, until a thorough investigation of the role of O2 in the reaction has been carried out, the proposed mechanisms remain speculative in this respect.

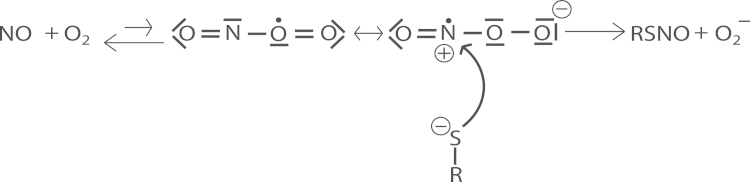

Reflections on the molecular aspects

Whereas the present results allow some conclusions on the overall reaction mechanism(s) of direct nitrosation, the molecular details remain uncertain, especially for the Mg2+-catalyzed reaction. For the reaction in the absence of Mg2+, the present observations support a mechanism whereby a thiolate reacts with a preformed nitrosyldioxyl radical (ONOO•) intermediate. Although the binding constant for ONOO• is probably very low [36], [37], [38], [39], its formation is likely to stimulate nitrosation by enhancing the susceptibility of the nitrogen to nucleophilic attack by the thiolate (see Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Putative mechanism for direct NO/O2-induced nitrosothiol formation.

For the reaction in the presence of Mg2+ the situation is less clear. Conceivably the reaction proceeds by a mechanism similar to that proposed for nitrosothiol formation catalyzed by dinitrosyliron complexes (DNICs) [40]. Although mechanistic details are lacking, the role of the Fe2+ cation in this reaction seems to be restricted to the activation of the NO ligands, with no net change in the Fe redox state. A similar role is feasible for Mg2+ and Ca2+. However, the maximal yield of the DNIC-catalyzed process seems to lie far below 50%, with products other than nitrosothiols being formed simultaneously. Moreover, Mg2+ and Ca2+ have a very strong preference for O and N coordination over S coordination, and theoretical studies consistently predict that thiols will coordinate to these cations with the carboxylate and amine rather than with the thiolate moieties [41]. Nevertheless, the results suggest that the Mg2+-catalyzed reaction starts with the formation of a complex between the cation and the thiol. We therefore propose that the role of the cation consists in assembling the reactants and activating NO for nucleophilic attack by the thiol, acting as a Lewis acid. Because the thiol is probably not coordinated to the Mg2+ by its sulfur atom, the nucleophilicity of the bound thiol will not be diminished, whereas coordination of NO to the Mg2+, most likely by the O atom, might make it more vulnerable to nucleophilic attack. Coordination of at least two thiols and two NO moieties to the metal cation might also explain the apparent lack of superoxide production, because it would allow formation of two equivalents of RSNO to be coupled to the production of one equivalent of H2O2. Mg2+ might facilitate direct H2O2 formation by stabilizing the bound O2 − moiety.

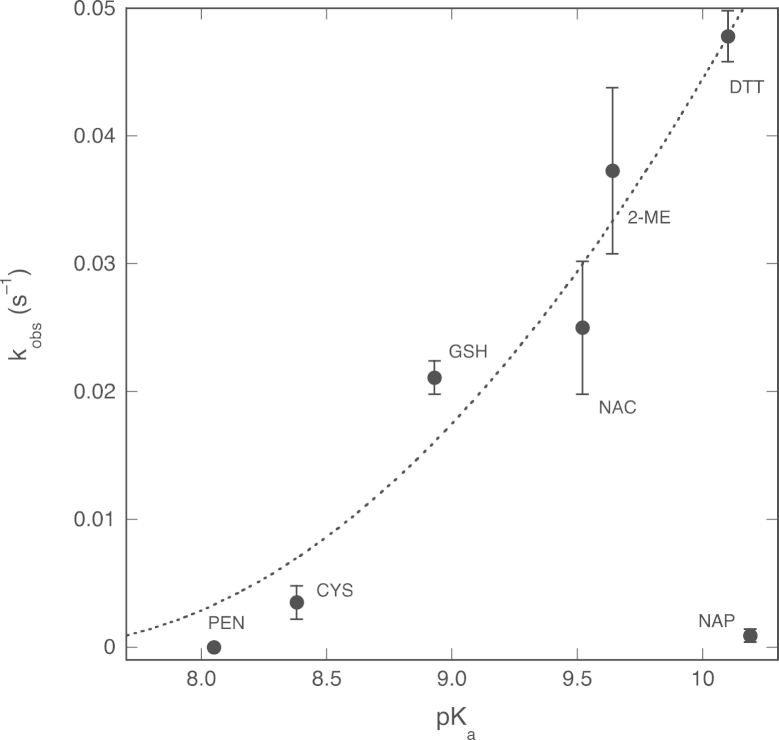

The order of reactivity of the various thiols is about the same for the reactions in the absence and presence of Mg2+. There is no correlation with the redox potential of the thiols, but the reactivity appears to increase with the pK a of the sulfhydryl side chain, apart from the lack of reactivity of penicillamine and N-acetylpenicillamine ( Fig. 10). These results therefore suggest that the nucleophilicity of the thiol is crucial to the reactivity of the compounds, but without a need for deprotonation as a first step ( Scheme 3). The lack of reactivity of penicillamine and especially N-acetylpenicillamine may be due to the fact that these compounds have the sulfhydryl group attached to a tertiary carbon [42]. Similar observations have been reported for the transnitrosation of penicillamine by SNAP [43].

Fig. 10.

Correlation between thiol pKa values and observed rate constants for thiol-induced NO consumption. The observed rate constants for the reaction between NO and various thiols in the presence of Mg2+ (the black columns of Fig. 8A) are plotted against the thiol pKa values. 2-ME, 2-mercaptoethanol, pKa=9.64 [48]; DTT, dithiothreitol, pKa=9.2 and 10.1 [49]; CYS, cysteine, pKa=8.38 [32], [34], [43], [50]; NAC, N-acetylcysteine, pKa=9.52 [34], [42], [43]; GSH, glutathione, pKa=8.93 [33], [45], [51]; PEN, penicillamine, pKa=8.05 [50], [52]; NAP, N-acetylpenicillamine, pKa=10.19 [53], [54]. We plotted the higher of the two pKa values of DTT (10.1) in view of the proposed mechanism (nucleophilic attack without deprotonation, see main text). The dotted line through the data points is a visual aid without specific meaning.

Scheme 3.

Proposed explanation for the relative reactivities of the thiols.

Physiological significance

It has generally been assumed that aerobic S-nitrosation involves NO2 and/or N2O3 as nitrosating agents [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [23]. Because these compounds are formed as short-lived intermediates in NO autoxidation, a reaction that is second order in [NO], aerobic nitrosation has been regarded as too slow to be physiologically relevant [3], [4], [5], [10], [12], [13], [17], [20], [21]. However, we recently demonstrated that at submicromolar concentrations of NO aerobic nitrosothiol formation is first order in [NO] and occurs at a fairly high rate that was stimulated considerably by Mg2+ and Ca2+ [24]. In the present study we demonstrate that this stimulation amounts to an approximately 20-fold increase of the apparent rate constant and that it occurs at cation and thiol concentrations in the low millimolar range. These observations suggest that inside cells Mg2+-catalyzed GSNO formation may be physiologically relevant in view of the intracellular concentrations of free Mg2+ (0.5–1.0 mM depending on cell type [44]) and GSH (1–11 mM [45]).

In contrast, the reaction may play no part in nitrosothiol formation in the circulation, because plasma levels of GSH are extremely low (≤10 µM [45]). Moreover, the present results suggest that aerobic nitrosation of albumin, the main thiol-containing compound in plasma, is not stimulated by Mg2+. This may be partly explained by the capacity of albumin to bind metal cations, which will lower the free Mg2+ concentration, thereby curbing any stimulatory effect of Mg2+. Also, because commercial albumin preparations contain inadvertently bound Mg2+ and Ca2+, in the present studies increasing albumin concentrations may have been associated with increasing concentrations of free Mg2+ and Ca2+, potentially obscuring the effect of added Mg2+. However, the virtually identical results we obtained with two completely different albumin preparations suggest that this effect is negligible. We can also not completely rule out that the presence of oxidized thiols in the albumin (≥50%) somehow affected the reaction. More likely, however, there may be steric impediments to the formation of the catalytic complex of Mg2+ with NO, O2, and the free thiol of albumin.

It should be stressed that, although the Mg2+ effect seems to be absent, substantial nitrosation did occur at physiologically relevant concentrations of NO and albumin. Further research will be required to determine if this reaction is responsible for the previously reported aerobic formation of Alb-SNO by low fluxes of NO in human plasma [46]. We should also point out that, although albumin is the most abundant thiol in the circulation, there are other potential targets to which the apparent lack of catalysis by Mg2+ observed for albumin may not apply.

Whereas the present data show that the reactions studied here should prevail over autoxidation-mediated processes for physiological levels of NO, the situation is less clear for comparisons with some of the other proposed pathways. Although our analysis suggests that aerobic direct S-nitrosation should be physiologically relevant, there are as yet no experimental data in cells or in vivo to support that suggestion. By contrast, Bosworth et al. provided strong evidence for a role of DNICs in protein S-nitrosation in RAW 264.7 macrophages [11]. However, as far as we are aware, it is currently unclear if those data can be extrapolated to other cell types and lower NO doses (experiments were performed with 5 or 10 µM SPER/NO, which constitutes a considerably higher total concentration than studied by us, albeit the actual NO concentrations appear never to have exceeded ~0.9 µM). Direct comparison between the two pathways is currently impossible because of a lack of cellular data for the mechanism proposed here, on the one hand, and of kinetic data for the DNIC-mediated reaction(s) on the other. Interestingly, however, DNIC seems not to mediate the nitrosation of GSH, which is the main target of the reactions studied here.

A second mechanism that was demonstrated in cells is the direct nitrosation of GSH by NO and cytochrome c [21], which may be mechanistically similar to the reaction studied here, with the heme of cytochrome c taking over the role of O2 (and perhaps that of Mg2+ as well). In this case a rough direct comparison with the aerobic reaction is possible, because an apparent rate constant can be estimated from studies with the isolated reactants [47]. Interestingly, these data suggest an apparent rate constant of ~6.6×104 M−2 s−1, which is quite close to the value we can estimate for the aerobic reaction in the presence of Mg2+ (~4×104 M−2 s−1). Consequently, it can be surmised that the relative contributions of both pathways will depend on the respective oxygen level (oxic, hypoxic, anoxic), the subcellular location (mitochondria or cytosol), the mitochondrial respiratory state (only oxidized cytochrome c catalyzes nitrosation), and perhaps the cell type. Cellular studies of the Mg2+-catalyzed process will be required to resolve these issues.

In summary, we demonstrated that NO/O2-mediated nitrosothiol formation probably involves nucleophilic attack of the protonated thiol on a transient ONOO complex and that reaction rates are increased 15- to 20-fold by Mg2+. The physiological impact of this reaction is difficult to predict, as it will critically depend on the intracellular concentrations of thiol (GSH between 1 and 11 mM), O2 (10–100 µM), Mg2+ (0.3–1.0 mM), and NO (physiologically ≤5 nM). Consequently, the actual rate of nitrosation might lie anywhere between 0.2 pM s−1 and 0.2 nM s−1. Higher nitrosation rates might occur under pathophysiological conditions. Additional studies are required to corroborate the physiological relevance of the reaction described here.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund: P23135 (to A.C.F.G.) and P20669, P21693, and P24005 (to B.M.).

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.08.024.

Appendix A. Supplementary materials

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Gorren A.C. F., Schrammel A., Schmidt K., Mayer B. Decomposition of S-nitrosoglutathione in the presence of copper ions and glutathione. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1996;330:219–228. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler A.R., Rhodes P. Chemistry, analysis, and biological roles of S-nitrosothiols. Anal. Biochem. 1997;249:1–9. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaston B. Nitric oxide and thiol groups. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1411:323–333. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00023-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miersch S., Mutus B. Protein S-nitrosation: biochemistry and characterization of protein thiol–NO interactions as cellular signals. Clin. Biochem. 2005;38:777–791. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hogg N. The biochemistry and physiology of S-nitrosothiols. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;42:585–600. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.092501.104328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hess D.T., Stamler J.S. Regulation by S-nitrosylation of protein post-translational modification. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:4411–4418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.285742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marozkina M.V., Gaston B. S-nitrosylation signaling regulates cellular protein interactions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1820:722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez Schulman I., Hare J.M. Regulation of cardiovascular cellular processes by S-nitrosylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1820:752–762. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gould N., Doulias P.-T., Tenopoulou M., Raju K., Ischiropoulos H. Regulation of protein function and signaling by reversible cysteine S-nitrosylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:26473–26479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.460261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrammel A., Gorren A.C. F., Schmidt K., Pfeiffer S., Mayer B. S-nitrosation of glutathione by nitric oxide, peroxynitrite, and •NO/O2•− . Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:1078–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosworth C.A., Toledo J.C., Jr, Zmijewski J.W., Li Q., Lancaster J.R., Jr. Dinitrosyliron complexes and the mechanism(s) of cellular protein nitrosothiol formation from nitric oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:4671–4676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710416106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith B.C., Marletta M.A. Mechanisms of S-nitrosothiol formation and selectivity in nitric oxide signaling. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012;16:498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagababu E., Rifkind J.M. Routes for formation of S-nitrosothiols in blood. Cell. Biochem. Biophys. 2013;67:385–398. doi: 10.1007/s12013-011-9321-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broniowska K.A., Diers A.R., Hogg N. S-nitrosoglutathione. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1830:3173–3181. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wink D.A., Nims R.W., Darbyshire J.F., Christodoulou D., Hanbauer I., Cox G.W., Laval F., Laval J., Cook J.A., Krishna M.C., DeGraff W.G., Mitchell J.B. Reaction kinetics for nitrosation of cysteine and glutathione in aerobic nitric oxide solutions at neutral pH: insights into the fate and physiological effects of intermediates generated in the NO/O2 reaction. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1994;7:519–525. doi: 10.1021/tx00040a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kharitonov V.G., Sundquist A.R., Sharma V.S. Kinetics of nitrosation of thiols by nitric oxide in the presence of oxygen. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;47:28158–28164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.47.28158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein S., Czapski G. Mechanism of the nitrosation of thiols and amines by oxygenated •NO solutions: the nature of the nitrosating intermediates . J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:3419–3425. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keshive M., Singh S., Wishnok J.S., Tannenbaum S.R., Deen W.M. Kinetics of S-nitrosation of thiols in nitric oxide solutions. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1996;9:988–993. doi: 10.1021/tx960036y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jourd׳heuil D., Jourd׳heuil F.L., Feelisch M. Oxidation and nitrosation of thiols at low micromolar exposure to nitric oxide: evidence for a free radical mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15720–15726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300203200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas D.D., Ridnour L.A., Isenberg J.S., Flores-Santana W., Switzer C.H., Donzelli S., Hussain P., Vecoli C., Paolocci N., Ambs S., Colton C.A., Harris C.C., Roberts D.D., Wink D.A. The chemical biology of nitric oxide: implications in cellular signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008;45:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broniowska K.A., Keszler A., Basu S., Kim-Shapiro D.B., Hogg N. Cytochrome c-mediated formation of S-nitrosothiol in cells. Biochem. J. 2012;442:191–197. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gow A.J., Buerk D.G., Ischiropoulos H. A novel reaction mechanism for the formation of S-nitrosothiol in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:2841–2845. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keszler A., Zhang Y., Hogg N. Reaction between nitric oxide, glutathione, and oxygen in the presence and absence of protein: how are S-nitrosothiols formed? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;48:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolesnik B., Palten K., Schrammel A., Stessel H., Schmidt K., Mayer B., Gorren A.C. F. Efficient nitrosation of glutathione by nitric oxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;63:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wenzl M.V., Beretta M., Griesberger M., Russwurm M., Koesling D., Schmidt K., Mayer B., Gorren A.C. F. Site-directed mutagenesis of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 suggests three distinct pathways of nitroglycerin biotransformation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011;80:258–266. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.071704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayer B., Klatt P., Werner E.R., Schmidt K. Kinetics and mechanism of tetrahydrobiopterin-induced oxidation of nitric oxide. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:655–659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saavedra J.E., Southan G.J., Davies K.M., Lundell A., Markou C., Hanson S.R., Adrie C., Hurford W.E., Zapol W.M., Keefer L.K. Localizing antithrombotic and vasodilatory activity with a novel, ultrafast nitric oxide donor. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:4361–4365. doi: 10.1021/jm960616s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pfeiffer S., Schrammel A., Schmidt K., Mayer B. Electrochemical determination of S-nitrosothiols with a Clark-type nitric oxide electrode. Anal. Biochem. 1998;258:68–73. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feelisch M., Rassaf T., Mnaimneh S., Singh N., Bryan N.S., Jourd׳heuil D., Kelm M. Concomitant S-, N-, and heme-nitros(yl)ation in biological tissues and fluids: implications for the fate of NO in vivo. FASEB J. 2002;16:1775–1785. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0363com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayer B., Pfeiffer S., Schrammel A., Koesling D., Schmidt K., Brunner F. A new pathway of nitric oxide/cyclic GMP signaling involving S-nitrosogluathione. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:3264–3270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maragos C.M., Morley D., Wink D.A., Dunams T.M., Saavedra J.E., Hoffman A., Bove A.A., Isaac L., Hrabie J.A., Keefer L.K. Complexes of •NO with nucleophiles as agents for the controlled biological release of nitric oxide: vasorelaxant effects . J. Med. Chem. 1991;34:3242–3247. doi: 10.1021/jm00115a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berthon G. IUPAC Analytical Chemistry Division, Commission on Equilibrium Data. The stability constants of metal complexes of amino acids with polar side chains. Pure Appl. Chem. 1995;67:1117–1240. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krezel A., Bal W. Coordination chemistry of glutathione. Acta Biochim. Pol. 1999;46:567–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winterbourn C.C., Metodiewa D. Reactivity of biologically important thiol compounds with superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;27:322–328. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones C.M., Lawrence A., Wardman P., Burkitt M.J. Electron paramagnetic resonance spin trapping investigation into the kinetics of glutathione oxidation by the superoxide radical: re-evaluation of the rate constant. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;32:982–990. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00791-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koppenol W.H., Moreno J.J., Pryor W.A., Ischiropoulos H., Beckman J.S. Peroxynitrite, a cloaked oxidant formed by nitric oxide and superoxide. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1992;5:834–842. doi: 10.1021/tx00030a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Czapski G., Goldstein S. The role of the reactions of •NO with superoxide and oxygen in biological systems: a kinetic approach . Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995;19:785–794. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)00081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKee M.L. Ab initio study of the N2O4 potential energy surface: computational evidence for a new N2O4 isomer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:1629–1637. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas D.D., Liu X., Kantrow S.P., Lancaster J.R., Jr. The biological lifetime of nitric oxide: implications for the perivascular dynamics of NO and O2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:355–360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011379598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vanin A.F., Malenkova I.V., Serezhenkov V.A. Iron catalyzes both decomposition and synthesis of S-nitrosothiols: optical and electron paramagnetic resonance studies. Nitric Oxide. 1997;1:191–203. doi: 10.1006/niox.1997.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pesonen H., Aksela R., Laasonen K. Density functional complexation study of metal ions with cysteine. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2010;114:466–473. doi: 10.1021/jp905733d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedman M., Cavins J.F., Wall J.S. Relative nucleophilic reactivities of amino groups and mercaptide ions in addition reactions with α,β-unsaturated compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:3672–3682. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu T.-M., Chou T.-C. The kinetics of thiol-mediated decomposition of S-nitrosothiols. AAPS J. 2006;8:E485–E492. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grubbs R.D. Intracellular magnesium and magnesium buffering. BioMetals. 2002;15:251–259. doi: 10.1023/a:1016026831789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schafer F.Q., Buettner G.R. Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;30:1191–1212. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marley R., Patel R.P., Orie N, Ceaser E., Darley-Usmar V., Moore K. Formation of nanomolar concentrations of S-nitrosoalbumin in human plasma by nitric oxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;31:688–696. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00627-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Basu S., Keszler A., Azarova N.A., Nwanze N., Perlegas A., Shiva S., Broniowska K.A., Hogg N., Kim-Shapiro D.B. A novel role for cytochrome c: efficient catalysis of S-nitrosothiol formation. Free Radic. Biol. Chem. 2010;48:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brocklehurst K., Stuchbury T., Malthouse J.P. G. Reactivities of neutral and cationic forms of 2,2′-dipyridyl disulphide towards thiolate anions. Biochem. J. 1979;183:233–238. doi: 10.1042/bj1830233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whitesides G.M., Lilburn J.E., Szajewski R.P. Rates of thiol–disulfide interchange reactions between mono- and dithiols and Ellman׳s reagent. J. Org. Chem. 1977;42:332–338. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reid R.S., Rabenstein D.L. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the solution chemistry of metal complexes. XVII. Formation constants for the complexation of methylmercury by sulfhydryl-containing amino acids and related molecules. Can. J. Chem. 1981;59:1505–1514. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rabenstein D.L. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies of the acid–base chemistry of amino acids and peptides. I. Microscopic ionization constants of glutathione and methylmercury-complexed glutathione. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1973;95:2797–2803. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson E.W., Jr, Martin R.B. Penicillamine deprotonations and interactions with copper ions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1971;142:445–454. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(71)90508-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arnold A.P., Canty A.J. Methylmercury(II) sulfhydryl interactions: potentiometric determination of the formation constants for complexation of methylmercury(II) by sulfhydryl containing amino acids and related molecules, including glutathione. Can. J. Chem. 1983;61:1428–1434. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arnold A.P., Canty A.J., Reid R.S., Rabenstein D.L. Nuclear magnetic resonance and potentiometric studies of the complexation of methylmercury(II) by dithiols. Can. J. Chem. 1985;63:2430–2436. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material