Abstract

By reviewing the recent progress on the elucidation of the structure of gold carbenes and the definitions of metal carbenes and carbenoids, we recommend to use the term gold carbene to describe gold carbene-like intermediates, regardless of whether the carbene or carbocation extreme resonance dominates. Gold carbenes, because of the weak metal-to-carbene π-back-donation and their strongly electrophilic reactivity, could be classified into the broader family of Fischer carbenes, although their behavior and properties are very specific.

Keywords: carbenes, carbenoids, carbocations, Fischer carbenes, gold

Introduction

Over the last decade, the use of gold complexes as carbophilic π-acids has become a powerful tool for building molecular complexity in an atom-economical fashion.[1] Gold carbenes have very often been proposed as the key intermediates in many gold-catalyzed transformations (Scheme 1).[1–3]

Scheme 1.

Carbene and carbocation resonance forms of gold carbenes.

They are structurally related to singlet carbenes and possess somewhat related reactivity. Most general methods for the generation of gold carbene intermediates are summarized in Scheme 2 and include the 1,2-acyloxy migration of propargylic carboxylates (Scheme 2a),[4] cycloisomerization of 1,6-enynes (Scheme 2b),[1b,k, 5] decomposition of diazo compounds (Scheme 2c)[6, 7] and ring cleavage of cyclopropenes (Scheme 2d).[8] Other gold(I)-catalyzed transformations based on the oxidation of alkynes with pyridine N-oxides or sulfoxides (Scheme 2e),[1i, 9, 10] acetylenic Schmidt reactions (Scheme 2f),[11] the formation of gold vinylidene intermediates from (2-ethynylphenyl)alkynes (Scheme 2g),[1h, 12] and the retro-Buchner reaction of cycloheptatrienes (Scheme 2h)[13] have also been proposed to generate gold(I) carbene-type intermediates. Under stoichiometric conditions, the α-hydride abstraction of alkylgold(I) complexes also gives gold(I) carbenes.[14]

Scheme 2.

Most general methods for the generation of gold carbenes.

Despite their central role in gold(I) catalysis, the nature of gold carbenes has remained uncertain and even this very term has been questioned.[15] The term “gold carbenoid” has even been recommended to stress the carbocationic nature of these intermediates.[16] Beyond the terminological debate,[17] the isolation and structural characterization of several well-defined [LAuCR2]+ complexes has provided new insight into the nature of these key gold(I) species. Here we review these findings and discuss the advantages of distinguishing gold carbenes and carbenoids as different species.

The Structure of Gold Carbenes

A fundamental description of the bonding mode of gold carbene was proposed by Toste and Goddard in 2009.[18] Accordingly, the ligand L and carbene can both donate their paired electrons to gold, forming a three-center four-electron σ-hyperbond. The gold center can also form two π-bonds by back-donation of its electrons from two filled 5d orbitals to empty π-acceptors on the ligand and carbene (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Schematic representation of the bonding of gold carbenes.

Considering the competition between ligand and carbene for the electron density from gold, the ligand and substituent have a significant influence on the bonding and reactivity of a given gold carbene. An increase in gold-to-carbon π-bonding and a decrease in the σ-bonding leads to structures with more carbene-like character (Scheme 4). Thus, strongly σ-donating and weakly π-acidic ligands, such as NHCs (N-heterocyclic carbenes), MICs (mesoionic carbenes),[19] or CAACs (cyclic (alkyl)- (amino)carbenes)[20] are expected to increase the carbene-like reactivity (Scheme 5).

Scheme 4.

Influence of the ligand on the carbocation-like or carbene-like properties of gold carbenes.[18]

Scheme 5.

NHC ligands increase the back-donation from gold to carbene.[18]

For example, it was shown that a gold complex with IPr (1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazolidene) as the ligand was the best catalyst for the cyclopropanation of cis-stilbene,[18] which is a typical carbene-type transformation (Scheme 6). In contrast, poor σ-donating and π-acidic ligands, such as phosphites, increase the carbocation-like character[7] of the intermediates by decreasing the electron density around gold and thus the gold-to-carbene π-donation.

Scheme 6.

NHC ligands favor carbene-type transformations.[18]

Gold(I) carbenes have been proposed as intermediates in other types of cyclopropanation reactions.[1] One of the most emblematic examples involves the stereospecific trapping of cyclopropyl gold(I) carbenes by alkenes.[5b, 21, 22] However, cyclopropanation of polarized alkenes, such as styrenes[21] or enol ethers,[3a, b, 23] occur stepwise, although the overall process is still stereospecific, since the second carbon–carbon bond formation occurs through a rather low energy barrier.[21]

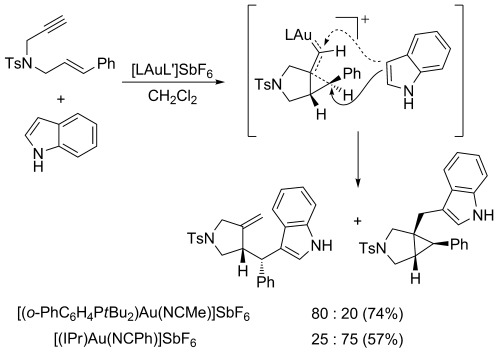

Another illustrative example of a ligand-controlled gold(I)-catalyzed reaction involving a gold(I) carbene-like intermediate is the addition of indole to a 1,6-enyne to give two products (Scheme 7).[24] A gold(I) complex with a strongly electron-donating NHC ligand favors attack at the carbene center of the intermediate, whereas reaction at the cyclopropyl moiety is favored using a phosphine–gold(I) complex. This result can again be explained by the enhancement of the carbene-like character of the cyclopropyl gold(I) carbene intermediate by the strongly donating carbene ligand. Regarding the nature of the intermediates formed in the reactions of 1,6-enynes, according to theoretical calculations, their structures are intermediate between cyclopropyl gold(I) carbenes and gold(I)-stabilized cyclopropylmethyl/cyclobutyl/homoallyl carbocations.[25]

Scheme 7.

Site-selectivity in the gold(I)-catalyzed nucleophilic attack of indole on a 1,6-enyne.[24b]

The reactivity displayed by intermediates formed in the gold(I)-catalyzed retro-Buchner reaction (Scheme 2h) has been shown to be more similar to that of metal carbenes of rhodium or copper, or even free carbenes, than carbocations.[13b] Thus, like free o-biphenylcarbene, 2-cycloheptatrienyl biphenyls give rise to fluorenes,[13b] whereas an o-phenylbenzyl carbocation failed to undergo a similar cyclization (Scheme 8).[26]

Scheme 8.

Formation of fluorenes via retro-Buchner reaction.[13b]

Benzylidene [(NHC)AuCHPh]+ and methoxymethylidene [(NHC)AuCHOMe]+ gold(I) carbenes have been generated in the gas phase by the collision-induced dissociation of ylide precursors and undergo cyclopropanation reactions with electron-rich alkenes.[3, 23] A related study has been carried out in the gas phase on related phosphine complexes of formal [LAuCHR]+.[27] Interestingly, for the series of [(NHC)MCHOMe]+ coinage metal cations, gold(I) and copper(I) stabilize the carbene more significantly than silver(I), which binds weakly to the methoxymethylidene moiety due to a weak π-back-donation.[3d]

A comparison of bond lengths should provide information about the bonding mode of a given metal carbene. Representative bond lengths for the heteroatom-stabilized gold(I) complexes (Table 1, entries 1–5),[16, 28–31] are rather similar with that of a C(sp2)–Au single bond (e.g., the Au–C bond length of gold complex [Ph3PAuC6H5] is 2.045(6) Å[32]). The observation of shortened C–O or C–N bonds demonstrates that the heteroatoms strongly stabilize the carbene center by sharing the electrons of one of their lone pairs, which is characteristic of Fischer carbenes. A similar observation was made for gold–allenylidene species[12e] and for complexes formed in the cyclization of allenoates.[33]

Table 1.

Bond lengths of several gold carbene complexes

| Structure | C–Au bond length [Å] | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

2.02(3) | [28] |

| 2 |  |

2.010(10) | [29] |

| 3 |  |

X=H 2.046(5) | [30] |

| 4 | X=OMe 2.0398(15) | [16] | |

| 5[a] |  |

2.032(4) | [31] |

| 6 |  |

2.039(5) | [16] |

| 7[b] |  |

2.014(6) | [34] |

| 8 |  |

2.035(6) | [40] |

| 9 |  |

1.984(4) | [41] |

[a] L=JohnPhos. [b] For IPr** see Scheme 9.

More recently, Fürstner and co-workers isolated the first gold carbene complex without heteroatom stabilization, which is more closely related to the gold(I) carbene intermediates proposed in many gold(I)-catalyzed reactions (Table 1, entry 6).[16] In this case, the bond between the carbene center and the aryl group is shortened appreciably. The more contracted C–C bond corresponds to an aryl ring that is nearly co-planar with the carbene center to enable efficient orbital overlap, which stabilizes the electron-deficient center. However, since the 4-methoxylphenyl substituent is a very strong electron-donating group, its strong ability to stabilize the carbene center gives gold little opportunity to back-donate electrons to the empty p orbital of carbene.

Predictably, in cases in which the carbene center cannot obtain sufficient stabilization from substituents, the back-donation from gold is a source of stabilization, and the gold carbene bonding model is still a pertinent representation. This prediction was proved by the group of Straub using a sterically demanding NHC ligand (Scheme 9) to form a gold carbene complex (Table 1, entry 7).[34] The Au–CMes2 bond (2.014(6) Å) is slightly shorter than the Au–C(IPr**) bond (2.030(6) Å). According to Bent’s rule,[35] the more electronegative nitrogen atoms in the IPr** ancillary ligand and the larger Au-C-N angles lead to a greater s character in the Au–C(IPr**) σ-bond than in the Au–CMes2 α-bond. Since NHCs are strong σ-donating and very weak π-acidic ligands, the π-back-bonding in Au–C(IPr**) is negligible. Thus, without π-back-bonding, the expected Au–CMes2 bond should have been longer than the Au–C(IPr**) bond; however, the opposite was observed, which was attributed to a significant, although not predominant, double bond character in Au=CMes2. Furthermore, this research group found that the activation energy for the rotation of the mesityl group is approximately 9 kcal mol−1, which also supports the partial double bond character of the Au=CMes2 bond (Scheme 9).[34] It is important to note that, although this barrier is low, a 12.4 kcal mol−1 barrier of rotation was determined for the first Fischer carbene complex [(CO)5Cr=C(OMe)Me].[36] Indeed, typical rotational barriers in a wide variety of alkylidene metal complexes are in the range of 10 to 18 kcal mol−1.[37, 38]

Scheme 9.

Rotation of the mesityl substituents in [IPr**Au=CMes2].[34]

As noted by Toste and Goddard,[18] the overall bond order of gold(I) carbenes is generally less than or equal to one, much like the double “half-bond” model proposed for rhodium carbenes,[39] which is not well represented either by the carbene resonance (bond order=2) or the carbocationic resonance (bond order=1). Straub attributed this phenomenon to the antibonding interaction of gold 5d shell with the sp2-hybridized electron pair of the carbene ligand, which weakens the σ-bond of gold carbene and therefore decreases the observed bond order of gold carbenes.[34]

Back-donation from gold to carbene was also found by the group of Widenhoefer when they compared the bond lengths difference of two distinct C–C bonds of a cyclopropyl group with that of some known cyclopropyl cationic compounds (Table 1, entry 5).[31] These authors concluded that the carbocation stabilizing ability of LAu fragment is similar to that of a cyclopropyl group, and it exceeds that of a methyl or phenyl group. Widenhoefer also synthesized a cycloheptatrienylidene gold(I) complex bearing the bulky phosphine (o-biphenyl)P(tBu)2 (Johnphos) ligand (Table 1, entry 8).[40] Although, as expected, the cycloheptatrienylidene protons were characteristic of a tropylium cation, shifted downfield in the 1H NMR spectrum with respect to the protons of neutral (Johnphos)Au–cycloheptatrienyl complex, the relatively compressed C7-C1-C2 bond angle (123.38°) of the cycloheptatrienylidene ligand suggested a contribution of a gold carbene resonance form. For related gold–allenylidene complexes, DFT calculations supported a higher allenylidene character for species that do not possess other heteroatom stabilization.[12e]

Very recently, the group of Bourissou reported the synthesis and structural characterization of a remarkable diphenylcarbene complex [L2Au=CPh2]+ with an o-carborane diphosphine, which shows the shortest Au–C bond (1.98 Å) to date (Table 1, entry 9).[41] The bending induced by the o-carborane diphosphine ligand substantially raises the energy of the dxz(Au) orbital, increasing significantly the π-back-donation to the carbene ligand. Interestingly, the bonds between the carbene center and the Cipso(Ph) carbon atoms are not contracted and the two phenyl rings are significantly twisted from the carbene plane, implying a very weak π-stabilization of the carbene by these substituents. The related carbonyl complex [L2AuCO]+ was also prepared as the first carbonyl complex of gold with a CO stretching frequency lower than that of free CO (2113 vs. 2143 cm−1), which again is indicative of a substantial Au to CO π-back-donation.[41]

Carbenoids and Carbenes

The IUPAC definition of carbenoids as “complexed carbene-like entities that display the reactivity characteristics of carbenes, either directly or by acting as sources of carbenes”[42] is rather vague and would lead, for example, to classify Fischer carbenes as carbenoids, because of their known involvement in cyclopropanation reactions with electron-rich alkenes.[43] Often, the term carbenoid is used to describe organometallic species [LnMCH2X] that contain a good leaving group and a carbon–metal bond at the same site, such as the Simmons–Smith reagent (iodomethylzinc iodide) and related species.[44]

More general, and didactically useful, is the distinction between carbenoids and carbenes as different species that are, however, related by the addition/elimination of an X− group, regardless of the double bond character of the metal–carbon bond in the carbene (Scheme 10).[45] Thus, [(Ph3P)2M(CH2Cl)Cl] (M=Pd, Pt) are two well-characterized examples of d8 square planar Group 11 metal carbenoids.[46] Indeed, two authentic gold(I) carbenoids have been prepared and structurally characterized.[47] As expected, the metal–carbon bond length in these gold(I) carbenoids (2.09 Å) is longer than in gold(I) carbenes of Table 1.

Scheme 10.

Carbenoid and carbene equilibrium and isolated gold(I) carbenoids.[47b]

The terminological distinction between gold(I) carbenes and carbenoids is also useful in the context of mechanistic discussions. Thus, a recent study in the gas-phase strongly suggests that the gold(I)-catalyzed oxidation of alkynes by pyridine N-oxides actually gives gold(I) carbenoids instead of α-oxo carbenes (Scheme 11).[10] α-Oxo carbenes might be formed by elimination of pyridine from the initially adducts, but presumably react rapidly with pyridine to form the more stable gold(I) carbenoids.

Scheme 11.

Generation of gold(I) carbenoids in the oxidation of alkynes with pyridine N-oxides.[10]

Metal-coordinated carbenes, [LnM=CR2], have traditionally been divided into singlet-derived Fischer carbenes and triplet-derived Schrock carbenes.[48] Fischer carbenes usually contain a π-donating group, such as –OMe or –NMe2,[49] on the carbene carbon atom to stabilize the empty p orbital on the carbene carbon atom by π-donation from one of the heteroatom lone pairs. This stability effect makes the metal-to-carbene π-back-donation weak and the direct carbene-to-metal σ-donation predominates. Therefore, the carbon atom is positively charged, and the carbene behaves as an electrophilic species (Scheme 12).[50] Thus, typical Fischer carbenes can be viewed as metal- and heteroatom-stabilized carbocations or more simply as metalated carbocations.[48b] This is the case for metal carbenes of late transition metals, which show higher electronegativity and more stable metals (dπ). In the case of Schrock carbenes, two covalent bonds between metal and triplet carbene are formed, and each metal–carbon bond is polarized toward the carbon atom because of its higher electronegativity. As a result, the carbon atom tends to be more negatively charged, and the carbene exhibits nucleophilic character. Schrock carbenes can also be viewed as a Fischer carbenes with very strong back-donation.

Scheme 12.

The bonding structure of typical Fischer carbenes.

The back-donation ability is expected to vary depending on the electronegativity of the metal complex, with the σ-bond being stronger and the π-bond becoming weaker as the metal becomes more electrophilic. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that in the case of gold, the most electronegative of all transition metals, the corresponding carbenes also exhibit special characteristics. Thus, from the experiments and data analysis, it is clear that the gold(I)-to-carbene back-donation does exist, especially when the structure is not highly stabilized by strong electron-donating groups (e.g., heteroatoms or electron-rich arenes). Strongly electrophilic cationic gold(I) carbenes are structurally related to the Fischer carbene family and are an extreme case in which the metal-to-carbene π-back-donation is weak. It is important to note that although Fischer carbenes usually have a heteroatom substituent at the carbene center, this is not a necessary condition.[49b, 51]

Although the term carbenoid for [LAuCR2]+ species has been preferred by many authors to underline their carbocationic character and poor π-back-donation from gold(I), this would be less appropriate for complexes such as those characterized by Straub[34] and Bourissou.[41] In our opinion, the term carbenoid should be better applied to metal complexes such as [LAuCH2Cl],[47] which bear a clear structural similarity to well-established zinc carbenoids involved in the Simmons–Smith cyclopropanation. Therefore, to conclude, we agree with the description of gold carbenes formulated by Toste and Goddard:[18] “The reactivity in gold(I)-coordinated carbenes is best accounted for by a continuum ranging from a metal-stabilized singlet carbene to a metal-coordinated carbocation. The position of a given gold species on this continuum is largely determined by the carbene substituents and the ancillary ligand”.

Acknowledgments

We thank MINECO (Severo Ochoa Excellence Accreditation 2014–2018 (SEV-2013-0319) and project CTQ2013-42106-P), the European Research Council (Advanced Grant No. 321066), the AGAUR (2014 SGR 818), and the ICIQ Foundation. M.E.M. acknowledges the receipt of a COFUND (Marie Curie program) postdoctoral fellowship.

References

- 1a.Gorin DJ, Toste FD. Nature. 2007;446:395–403. doi: 10.1038/nature05592. For recent reviews on homogeneous gold catalysis, see. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1b.Jiménez-Núñez E, Echavarren AM. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3326–3350. doi: 10.1021/cr0684319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c.Díaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3379–3394. doi: 10.1021/cr078364y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d.Fürstner A, Davies PW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:3410–3449. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2007;119 [Google Scholar]

- 1e.Fürstner A. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3208–3221. doi: 10.1039/b816696j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1f.Rudolph M, Hashmi ASK. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:2448–2462. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15279c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1g.Obradors C, Echavarren AM. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:16–28. doi: 10.1039/c3cc45518a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1h.Hashmi ASK. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:864–876. doi: 10.1021/ar500015k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1i.Zhang L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:877–888. doi: 10.1021/ar400181x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1j.Wang Y-M, Lackner AD, Toste FD. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:889–901. doi: 10.1021/ar400188g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1k.Obradors C, Echavarren AM. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:902–912. doi: 10.1021/ar400174p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1l.Zhang D-H, Tang X-Y, Shi M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:913–924. doi: 10.1021/ar400159r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1m.Fürstner A. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:925–938. doi: 10.1021/ar4001789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1n.Alcaide B, Almendros P. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:939–952. doi: 10.1021/ar4002558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1o.Fensterbank L, Malacria M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:953–965. doi: 10.1021/ar4002334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1p.Yeom H-S, Shin S. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:966–977. doi: 10.1021/ar4001839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2a.Hashmi ASK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:5232–5241. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2010;122 [Google Scholar]

- 2b.Liu L-P, Hammond GB. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:3129–3139. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15318a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c.Zhang L. In: Contemporary Carbene Chemistry. Moss RA, Doyle MP, editors. Hoboken: Wiley; 2013. pp. 526–551. “Gold Carbenes”. [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Fedorov A, Moret M-E, Chen P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8880–8881. doi: 10.1021/ja802060t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b.Fedorov A, Chen P. Organometallics. 2009;28:1278–1281. [Google Scholar]

- 3c.Fedorov A, Batiste L, Bach A, Birney DM, Chen P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12162–12171. doi: 10.1021/ja2041699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3d.Ringger DH, Chen P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:4686–4689. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2013;125 [Google Scholar]

- 3e.Batiste L, Chen P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:9296–9307. doi: 10.1021/ja4084495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3f.Ringger DH, Kobylianskii IJ, Serra D, Chen P. Chem. Eur. J. 2014;20:14270–14281. doi: 10.1002/chem.201403988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.de Haro T, Gómez-Bengoa E, Cribiú R, Huang X, Nevado C. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:6811–6824. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103472. For reviews and lead references on gold-catalyzed propargylic carboxylate rearrangement. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b.Wang S, Zhang G, Zhang L. Synlett. 2010:692–706. [Google Scholar]

- 4c.Shiroodi RK, Gevorgyan V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:4991–5001. doi: 10.1039/c3cs35514d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d.Correa A, Marion N, Fensterbank L, Malacria M, Nolan SP, Cavallo L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:718–721. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2008;120 [Google Scholar]

- 4e.Marco-Contelles J, Soriano E. Chem. Eur. J. 2007;13:1350–1357. doi: 10.1002/chem.200601522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4f.Amijs CHM, López-Carrillo V, Echavarren AM. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4021–4024. doi: 10.1021/ol701706d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4g.Li G, Zhang G, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3740–3741. doi: 10.1021/ja800001h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4h.Shapiro ND, Shi Y, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11654–11655. doi: 10.1021/ja903863b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4i.Shapiro ND, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9244–9245. doi: 10.1021/ja803890t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4j.Gorin DJ, Dubé P, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:14480–14481. doi: 10.1021/ja066694e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5a.Escribano-Cuesta A, López-Carrillo V, Janssen D, Echavarren AM. Chem. Eur. J. 2009;15:5646–5650. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b.López S, Herrero-Gómez E, Pérez-Galán P, Nieto-Oberhuber C, Echavarren AM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:6029–6032. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2006;118 [Google Scholar]

- 5c.Pérez-Galán P, Martin NJA, Campaña AG, Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. Chem. Asian J. Chem. Asian. J. 2011;6:482–486. doi: 10.1002/asia.201000557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5d.Taduri BP, Sohel SMA, Cheng H-M, Lin G-Y, Liu R-S. Chem. Commun. 2007:2530–2532. doi: 10.1039/b700659d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5e.Brooner REM, Brown TJ, Widenhoefer RA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:6259–6261. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2013;125 [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Fructos MR, Belderrain TR, de Frémont P, Scott NM, Nolan SP, Díaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5284–5288. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2005;117 [Google Scholar]

- 6b.Prieto A, Fructos MR, Díaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ, Pérez-Galán P, Delpont N, Echavarren AM. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:1790–1793. [Google Scholar]

- 6c.Rivilla I, Gómez-Emeterio BP, Fructos MR, Díaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ. Organometallics. 2011;30:2855–2860. [Google Scholar]

- 6d.Pérez PJ, Díaz-Requejo MM, Rivilla I. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011;7:653–657. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.7.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6e.Zhou L, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Wang J. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011;7:631–637. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.7.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Yu Z, Ma B, Chen M, Wu H-H, Liu L, Zhang J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:6904–6907. doi: 10.1021/ja503163k. For two recent examples that took advantage of this carbocation-like reactivity of gold carbenes by using phosphite ligand, see. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Y. Xi, Y. Su, Z. Yu, B. Dong, E. J. McClain, Y. Lan, X. Shi, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014 53 , DOI: [DOI]

- 8a.Hadfield MS, Bauer JT, Glen PE, Lee A-L. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:4090–4095. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00085j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b.Li C, Zeng Y, Wang J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:2956–2959. [Google Scholar]

- 8c.Li C, Zeng Y, Zhang H, Feng J, Zhang Y, Wang J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:6413–6417. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2010;122 [Google Scholar]

- 8d.Miege F, Meyer C, Cossy J. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2011;7:717–734. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.7.82. For a review on gold-catalyzed transformations of cyclopropenes, see. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9a.Shapiro ND, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4160–4161. doi: 10.1021/ja070789e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9b.Ye L, Cui L, Zhang G, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3258–3259. doi: 10.1021/ja100041e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9c.He W, Li C, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8482–8485. doi: 10.1021/ja2029188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9d.Noey EL, Luo Y, Zhang L, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1078–1084. doi: 10.1021/ja208860x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9e.Ji K, Zhang L. Org. Chem. Front. 2014;1:34–38. doi: 10.1039/C3QO00080J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9f.Vasu D, Hung H-H, Bhunia S, Gawade SA, Das A, Liu R-S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6911–6914. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2011;123 [Google Scholar]

- 9g.Nösel P, Nunes dos Santos Comprido L, Lauterbach T, Rudolph M, Rominger F, Hashmi ASK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:15662–15666. doi: 10.1021/ja4085385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9h.Shu C, Liu R, Liu S, Li J-Q, Yu Y-F, He Q, Lu X, Ye L-W. Chem. Asian J. 2015;10:91–95. doi: 10.1002/asia.201403032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz J, Jašíková L, Škríba A, Roithová J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:11513–11523. doi: 10.1021/ja505945d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.Gorin DJ, Davis NR, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11260–11261. doi: 10.1021/ja053804t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b.Lu B, Luo Y, Liu L, Ye L, Wang Y, Zhang L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:8358–8362. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2011;123 [Google Scholar]

- 11c.Yan Z, Xiao Y, Zhang L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:8624–8627. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2012;124 [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Ye L, Wang Y, Aue DH, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:31–34. doi: 10.1021/ja2091992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12b.Hashmi ASK, Braun I, Nösel P, Schädlich J, Wieteck M, Rudolph M, Rominger F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:4456–4460. doi: 10.1002/anie.201109183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2012;124 [Google Scholar]

- 12c.Hashmi ASK, Wieteck M, Braun I, Rudolph M, Rominger F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:10633–10637. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2012;124 [Google Scholar]

- 12d.Hansmann MM, Rudolph M, Rominger F, Hashmi ASK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:2593–2598. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2013;125 [Google Scholar]

- 12e.Hansmann MM, Rominger F, Hashmi ASK. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:1552–1559. [Google Scholar]

- 13a.Solorio-Alvarado CR, Wang Y, Echavarren AM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11952–11955. doi: 10.1021/ja205046h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b.Wang Y, McGonigal PR, Herlé B, Besora M, Echavarren AM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:801–809. doi: 10.1021/ja411626v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13c.Lebœuf D, Gaydou M, Wang Y, Echavarren AM. Org. Chem. Front. 2014;1:759–764. [Google Scholar]

- 13d.Wang Y, Muratore ME, Rong Z, Echavarren AM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:14022–14026. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ung G, Bertrand G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:11388–11391. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2013;125 [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Fürstner A, Morency L. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:5030–5033. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2008;120 [Google Scholar]

- 15b.Hashmi ASK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6754–6756. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2008;120 [Google Scholar]

- 15c.Seidel G, Mynott R, Fürstner A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:2510–2513. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2009;121 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seidel G, Fürstner A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:4807–4811. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Echavarren AM. Nat. Chem. 2009;1:431–433. doi: 10.1038/nchem.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benitez D, Shapiro ND, Tkatchouk E, Wang Y, Goddard WA, Toste FD. Nat. Chem. 2009;1:482–486. doi: 10.1038/nchem.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ung G, Soleilhavoup M, Bertrand G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:758–761. doi: 10.1002/anie.201207961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2013;125 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeng X, Kinjo R, Donnadieu B, Bertrand G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:942–945. doi: 10.1002/anie.200905341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2010;122 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pérez-Galán P, Herrero-Gómez H, Hog DT, Martin NJA, Maseras F, Echavarren AM. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- 22.López-Carrillo V, Huguet N, Mosquera A, Echavarren AM. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:10972–10978. doi: 10.1002/chem.201101749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batiste L, Fedorov A, Chen P. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:3899–3901. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00086h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Amijs CHM, Ferrer C, Echavarren AM. Chem. Commun. 2007:698–700. doi: 10.1039/b615335f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24b.Amijs CHM, López-Carrillo V, Raducan M, Pérez-Galán P, Ferrer C, Echavarren AM. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:7721–7730. doi: 10.1021/jo8014769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nieto-Oberhuber C, López S, Muñoz MP, Cárdenas DJ, Buñuel E, Nevado C, Echavarren AM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:6146–6148. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2005;117 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirmse W, Kund K, Ritzer E, Dorigo AE, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:6045–604. doi: 10.1021/ja00279a066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swift CA, Gronert S. Organometallics. 2014;33:7135–7140. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schubert U, Ackermann K, Aumann R. Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1982;11:591–594. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fañanás-Mastral M, Aznar F. Organometallics. 2009;28:666–668. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seidel G, Gabor B, Goddard R, Heggen B, Thiel W, Fürstner A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:879–882. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooner REM, Widenhoefer RA. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:2420–2423. doi: 10.1039/c3cc48869a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernández EJ, Laguna A, Olmos ME. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 2005;52:77–141. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Döpp R, Lothschütz C, Wurm T, Pernpointer M, Keller S, Rominger F, Hashmi ASK. Organometallics. 2011;30:5894–5903. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hussong MW, Rominger F, Krämer P, Straub BF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:9372–9375. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bent HA. Chem. Rev. 1961;61:275–311. [Google Scholar]

- 36a.Kreiter CG, Fischer EO. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1969;8:761–762. [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 1969;81 [Google Scholar]

- 36b.Fischer EO, Kreiter CG, Kollmeier HJ, Müller J, Fischer RD. J. Organomet. Chem. 1971;28:237–258. [Google Scholar]

- 37a.Kress J, Osborn JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:3953–3960. See, for example. [Google Scholar]

- 37b.Schrock RR, Crowe WE, Bazan GC, DiMare M, O’Regan MB, Schofield MH. Organometallics. 1991;10:1832–1843. [Google Scholar]

- 37c.Grisi F, Costabile C, Gallo E, Mariconda A, Tedesco C, Longo P. Organometallics. 2008;27:4649–4656. [Google Scholar]

- 37d.Castarlenas R, Esteruelas MA, Oñate E. Organometallics. 2007;26:2129–2132. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Temkin ON. Homogeneous Catalysis With Metal Complexes: Kinetic Aspects and Mechanisms. Hoboken: Wiley; 2012. p. 472. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder JP, Padwa A, Stengel T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11318–11319. doi: 10.1021/ja016928o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harris RJ, Widenhoefer RA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:9369–9371. doi: 10.1002/anie.201404882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joost M, Estévez L, Mallet-Ladeira S, Miqueu K, Amgoune A, Bourissou D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:14512–14516. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angew. Chem. 2014;126 [Google Scholar]

- 42. IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology1997, 2nd ed. (the “Gold Book”), Blackwell Science, Oxford.

- 43a.Casey CP, Shusterman AJ. Organometallics. 1985;4:736–744. See, for example. [Google Scholar]

- 43b.Soderberg BC, Hegedus LS. Organometallics. 1990;9:3113–3121. [Google Scholar]

- 43c.Harvey DF, Lund KP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:8916–8921. [Google Scholar]

- 43d.Barluenga J, Suárez-Sobrino AL, Tomás M, García-Granda S, Santiago-García R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:10494–10501. doi: 10.1021/ja010719m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43e.Barluenga J, Suero MG, Pérez-Sánchez I, Flórez J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2708–2709. doi: 10.1021/ja074363b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lebel H, Marcoux J-F, Molinaro C, Charette AB. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:977–1050. doi: 10.1021/cr010007e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bernardi F, Bottoni A, Miscione GP. Organometallics. 2000;19:5529–5532. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCrindle R, Ferguson G, McAlees AJ, Arsenault GJ, Gupta A, Jennings MC. Organometallics. 1995;14:2741–2748. [Google Scholar]

- 47a.Nesmeyanov AN, Perevalova EG, Smyslova EI, Dyadchenko VP, Grandberg KI. Izv. Akad. Nauk SSSR Ser. Khim. 1977:2610–2612. [Google Scholar]

- 47b.Steinborn D, Beckea S, Herzoga R, Günther M, Kircheisen R, Stoeckli-Evans H, Bruhn C. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1998;624:1303–1307. [Google Scholar]

- 48a.Crabtree RH. The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals. 4th Ed. Hoboken: Wiley; 2005. pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- 48b.Schubert U. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1984;55:261–286. [Google Scholar]

- 49a.Bly RS, Bly RK. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1986:1046–1047. [Google Scholar]

- 49b.Hayes JC, Jernakoff P, Miller GA, Cooper NJ. Pure Appl. Chem. 1984;56:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 49c.Barluenga J, Santamaría J, Tomás M. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2259–2284. doi: 10.1021/cr0306079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49d.Dötz KH, Stendel J., Jr Chem. Rev. 2009;109:3227–3274. doi: 10.1021/cr900034e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49e.Fernández I, Cossío FP, Sierra MA. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:479–490. doi: 10.1021/ar100159h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cases M, Frenking G, Duran M, Solà M. Organometallics. 1997;21:4182–4191. For an important DFT study on the influence of the carbene substituents on their molecular and electronic structure of pentacarbonyl chromium Fischer carbene complexes [(CO)5Cr=C(X)R], see: for a detailed study of bonding of chromium Fischer complexes, see. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C-C, Wang Y, Liu H-J, Lin K-J, Chou L-K, Chan K-S. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;101 and references therein. [Google Scholar]

- 51. The key point to distinguish Fischer from Schrock carbenes is the ability of back-donation from metal to carbene center. For a detailed discussion, see reference [44]