Background—

The mechanisms underlying pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) are multifactorial. The efficacy of pulmonary artery denervation (PADN) for idiopathic PAH treatment has been evaluated. This study aimed to analyze the hemodynamic, functional, and clinical responses to PADN in patients with PAH of different causes.

Methods and Results—

Between April 2012 and April 2014, 66 consecutive patients with a resting mean pulmonary arterial pressure ≥25 mm Hg treated with PADN were prospectively followed up. Target drugs were discontinued after the PADN procedure. Hemodynamic response and 6-minute walk distance were repeatedly measured within the 1 year post PADN follow-up. The clinical end point was the occurrence of PAH-related events at the 1-year follow-up. There were no PADN-related complications. Hemodynamic success (defined as the reduction in mean pulmonary arterial pressure by a minimal 10% post PADN) was achieved in 94% of all patients, with a mean absolute reduction in systolic pulmonary arterial pressure and mean pulmonary arterial pressure within 24 hours of −10 mm Hg and −7 mm Hg, respectively. The average increment in 6-minute walk distance after PADN was 94 m. Worse PAH-related events occurred in 10 patients (15%), mostly driven by the worsening of PAH (12%). There were 8 (12%) all-cause deaths, with 6 (9%) PAH-related deaths.

Conclusions—

PADN was safe and feasible for the treatment of PAH. The PADN procedure was associated with significant improvements in hemodynamic function, exercise capacity, and cardiac function and with less frequent PAH-related events and death at 1 year after PADN treatment. Further randomized studies are required to confirm the efficacy of PADN for PAH.

Clinical Trial Registration—

URL: http://www.chictr.trc.com.cn. Unique identifier: chiCTR-ONC-12002085.

Keywords: arterial pressure, denervation, hemodynamics, familial primary pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary artery

WHAT IS KNOWN

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is characterized by reduced survival from the time of diagnosis, and there are a limited number of drugs that have therapeutic efficacy in the disease.

Overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system and its direct effects on pulmonary artery vasoconstriction play a critical role in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

A proof-of-concept study testing pulmonary artery denervation was completed in a limited number of patients with low-risk pulmonary arterial hypertension.

WHAT THE STUDY ADDS

The pulmonary artery denervation procedure was safely and feasibly performed in 66 consecutive patients with different forms of pulmonary hypertension.

A randomized study with a larger patient population is required to determine whether there is therapeutic efficacy of pulmonary artery denervation in patients with pulmonary hypertension.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a debilitating condition that results in dyspnea and fatigue, impaired exercise capacity, and reduced survival.1 Modest improvements in 6-minute walk distance (6MWD) can be achieved with endothelial-receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors, and prostacyclin analogs,1–3 although the extent of improvement varies according to the cause of PAH,2 and the effects on morbidity and mortality are less certain.4 Combination therapy with multiple drugs targeting different pathways has been recommended, increasing the likelihood of side effects.5,6

See Editor’s Perspective by Leopold

Sympathetic overactivation has been reported, and the effect of β-blockers in PAH patients has been assessed.1 Pulmonary artery nerve denervation could completely resolve the increase in pulmonary arterial pressure (PAP) induced by an expandable device in the left lobar artery.7,8 Furthermore, we reported short-term clinical results of pulmonary artery denervation (PADN) without the use of PAH target drugs, which was associated with significant reductions in PAP and improvement in 6MWD at the 3-month follow-up in patients with idiopathic PAH (IPAH) who were unresponsive to medication.9 Since this report, questions have arisen on the procedural safety, long-term results, and potential for aneurysm and thrombus formation.9 In addition, the effects of PADN on other causes of PAH are unknown. Therefore, we sought to further investigate the hemodynamic, functional, and clinical responses to PADN (stand-alone therapy) in patients with PAH of different causes in this phase II report from the PADN-1 study.

Methods

PADN-I Registry and Patient Population

PADN-I phase I began in March 2012 and ended in May 20129 and was a first-in-man study that tested the safety and efficacy of PADN in 13 patients with IPAH who were unresponsive to standard medication. PADN-I phase II began in April 2012 and ended in April 2014, during which time PADN was performed in 66 consecutive patients with PAH.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients with a resting mean PAP (mPAP) ≥25 mm Hg, as measured by right heart catheterization, were included, although they were receiving PAH expert–based standard medical treatment. In patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) caused by left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, an additional requirement was pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) ≥3 Wood units. An adenosine vasodilator test8 was performed during right heart catheterization in all patients. Exclusion criteria included active infection, cancer, toxin- or anorexia-induced PH, portal hypertension, chronic thromboembolic PH without surgical treatment, intolerance to the PADN procedure (caused by the use of an 8-F-long sheath that occludes blood flow in the orifice of the tricuspid and pulmonary valves, resulting in severe dyspnea), and inability to provide consent.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Nanjing First Hospital (Nanjing, China), and all patients provided written inform consent.

Right Heart Catheterization

Resting right atrial (RA) pressure, right ventricular (RV) pressure, PAP, pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP), and thermodilution cardiac output were obtained with a 7-F flow-directed Swan-Ganz catheter. PVR ([mPAP−PAOP]/cardiac output) and transpulmonary gradient (mPAP−PAOP) were then derived. All measurements were taken at end expiration. If the PAOP measurement was unreliable,1,3,10 the LV end-diastolic pressure was used rather than the PAOP. Blood samples from the RA, RV, and PA were obtained, and if the oxygen saturation measurements varied by >7% between chambers, further sampling was performed to identify the location of the left-to-right shunt.

PADN Procedure

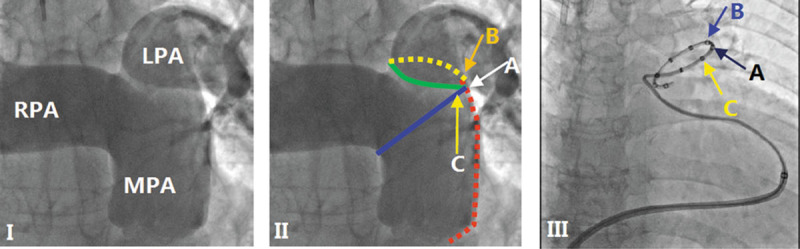

PA ablation was performed using a dedicated 7-F temperature-sensing ablation catheter. The details of the device and the PADN procedure have been previously described.7,8 Briefly, PADN was thereafter performed only in the periconjunctional area between the distal main trunk and the ostial left branch (points A, B, and C in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pulmonary arterial angiography, position of electrodes, and pulmonary artery denervation (PADN) procedure. (I) Anterior-posterior and cranial (200) view of the pulmonary arterial angiograph. (II) The red line represents the lateral wall of the main pulmonary artery (MPA), the blue line represents the anterior wall of the left pulmonary artery (LPA), and the point where the 2 lines intersect is point A; the intersection of the yellow (posterior wall of the LPA) and red lines is point B, which is 1 to 2 mm posterior to point A; the green line starts from the inferior wall of the right pulmonary artery (RPA) and ends at point A, and point C localizes at this level and 1 to 2 mm anterior to point A. (III) A pulmonary artery denervation catheter with 10 electrodes is positioned at the distal MPA, with electrodes A, B, and C at points A, B, and C, respectively.

The following ablation parameters were programmed at each point: temperature ≥45°C, energy ≤20 W, and time 120 s (for point C) or 240 s (for points A and B). The procedure was interrupted for 10 s if the patient reported severe chest pain. Electrocardiography and hemodynamic function were monitored and recorded continuously throughout the procedure.

Periprocedural Medication

A 5000-U heparin bolus was administered after the insertion of the venous sheath. Additional 2000- to 3000-U heparin boluses were administered if the procedural time was >1 hour. After the procedure, oral warfarin was prescribed and adjusted to an international normalized ratio of 1.5 to 2.5 for all patients. Aspirin (100 mg per day) and clopidogrel (75 mg per day) were indefinitely prescribed in the presence of contraindications for warfarin. Immediately after the PADN procedure, all target drugs (endothelial-receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors, and prostacyclin analogs) were discontinued. Diuretics were prescribed at a dosage less than or equal to that at baseline. Oxygen therapy was used according to patients’ symptoms, as assessed by a physician.

Assessment of Functional Capacity

Functional capacity was determined using a standard 6MWD protocol1,4 before PADN and at 1 week, 1 month, 2 months, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year after the procedure. Dyspnea was assessed by using the Borg scale.11 The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of dyspnea at rest and during exercise was recorded by a physician blinded to the study design.1 Baseline blood samples were obtained to measure N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide levels before each exercise test.

Echocardiographic Measurements

Transthoracic echocardiography (Vivid 7, General Electric Co, Easton Turnpike, CT) was performed immediately after the procedure and at 24 hours, 1 week, 1 month, 2 months, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year and was analyzed at the Nanjing Medical University Echocardiographic Laboratory. Digital echocardiographic data that contained a minimum of 3 consecutive beats (or 5 beats in cases of atrial fibrillation) were acquired and stored. RV systolic pressure was set equal to systolic PAP (sPAP) in the absence of pulmonary stenosis. sPAP was calculated as the sum of RA pressure and the RV to RA pressure gradient during systole. RA pressure was estimated based on the echocardiographic features of the inferior vena cava and assigned a standard value. The RV to RA pressure gradient was calculated as 4vt2 using the modified Bernoulli equation, where vt is the velocity of the tricuspid regurgitation jet in m/s. The mPAP was estimated according to the velocity of the pulmonary regurgitation jet in m/s. The tricuspid excursion index is defined as (A−B)/B, where A is the time interval between the end and the onset of tricuspid annular diastolic velocity and B is the duration of tricuspid annular systolic velocity (or the RV ejection time).12

Follow-Up

Patients were monitored in the critical care unit for at least 24 hours post procedure. Hemodynamic measurements, 6MWD, and echocardiographic measurements were repeated at 24 hours, 1 month, 2 months, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. Clinical follow-up was extended to 1 year. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomographic imaging of the pulmonary artery were performed before the PADN procedure and at 6 months.

Study End Points and Definitions

The primary end points were changes in hemodynamic, functional, and clinical responses within the 1-year follow-up. PAH-related clinical events were defined as those caused by worsening of PAH, initiation of treatment with intravenous or subcutaneous prostanoids, lung transplantation, atrial septostomy, or all-cause mortality. Worsening of PAH was defined as the occurrence of all 3 of the following: ≥15% decrease in 6MWD from baseline, confirmed by a second 6MWD performed on a different day within 14 days; worsening PAH symptoms; and the need for additional treatment for PAH. Worsening PAH symptoms were defined as a change from baseline to a higher WHO functional class (or no change in WHO functional class IV from that at baseline) plus the appearance or worsening signs of right heart failure not responsive to oral diuretic therapy. An independent clinical event committee adjudicated all deaths and reported events with respect to their relationship with PAH. Additional secondary end points included changes in 6MWD, WHO functional class, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide levels, PAH-related or all-cause mortality, echocardiographic measurements, and rehospitalization rates for PAH in the long term. The prespecified definition of PADN procedural hemodynamic success was reduction in mPAP immediately after PADN by ≥10, without the occurrence of any intraprocedural complications.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean±SD. Normality was examined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Data having unequal variances at different times were transferred to log data. Differences in continuous variables between 2 different timing points (baseline versus 6 months or 6 months versus 1 year) were analyzed with paired t tests. Categorical variables between group I, group II, and chronic thromboembolic PH groups or between 2 different timing points were compared by using Fisher exact or McNemar test, as appropriate. Event-free survival rate at 1 year was estimated by using the Kaplan–Meier method. Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P value of <0.05. All analyses were performed with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Institute Inc, Chicago, IL).

Data and Materials Availability

All raw data are available on request. PADN devices are available from Pulmo Co. Ltd (Wuxi, China).

Results

Patient Population

In all, 70 patients with qualifying PAH/PH were screened during the study period. Four patients were excluded: 2 patients with IPAH could not lie flat for 20 minutes, 1 with WHO group II PAH died in the ward after consent while waiting for the procedure, and 1 with WHO group IV PAH died of temporary pacing catheter-induced RV perforation before the PADN procedure. Thus, the study population consisted of 66 patients in whom PADN was attempted.

Cause and Baseline Characteristics

Among the 66 patients, 39 (59.1%) had WHO group I PAH (IPAH in 20 patients; 11 had PH secondary to connective tissue disorders; and 8 had PH secondary to congenital heart disease after surgical repair), 18 (27.3%) had group II PAH (PH secondary to LV dysfunction), and 9 (13.6%) had chronic thromboembolic PH after surgery. Of the 11 connective tissue disorders patients, 7 had systemic lupus erythematosus, 2 had mixed connective tissue disease, and 2 had primary Sjogren syndrome; of the 8 congenital heart disease after surgical repair patients, 5 had an atrial septal defect and 3 had patent ductus arteriosus. Of the patients with group II PAH, 15 had a previous myocardial infarction, and 3 had dilated cardiomyopathy.

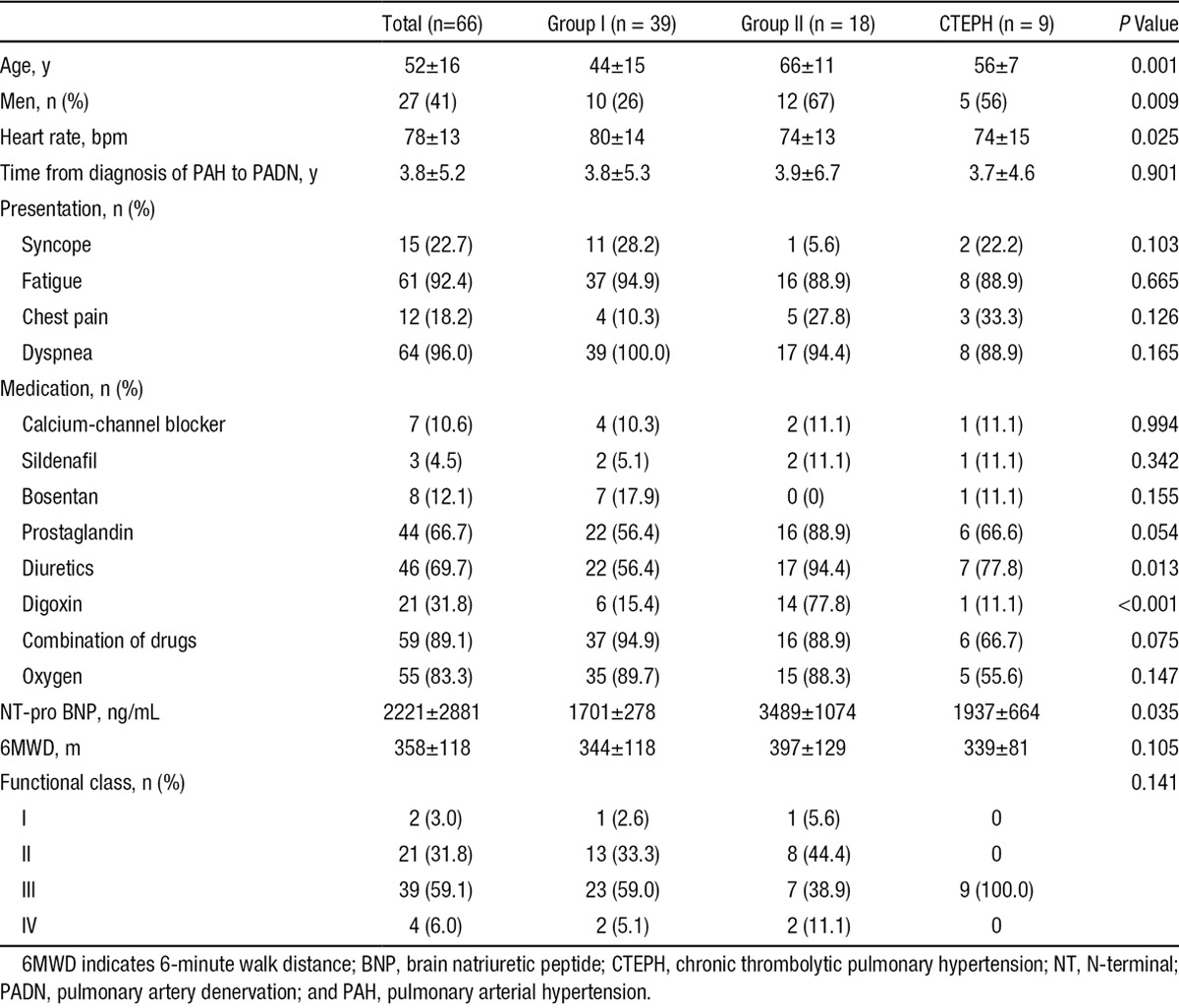

Baseline clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The average time from diagnosis of PAH to the PADN procedure was 3.8 years. A combination of drugs was required for 89.1% of patients. Most patients (90.9%) had WHO function classes II and III. In all, 55 patients (83.3%) were administered oxygen therapy. In all, 37 (56.1%) had pericardial effusion (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics of All Patients

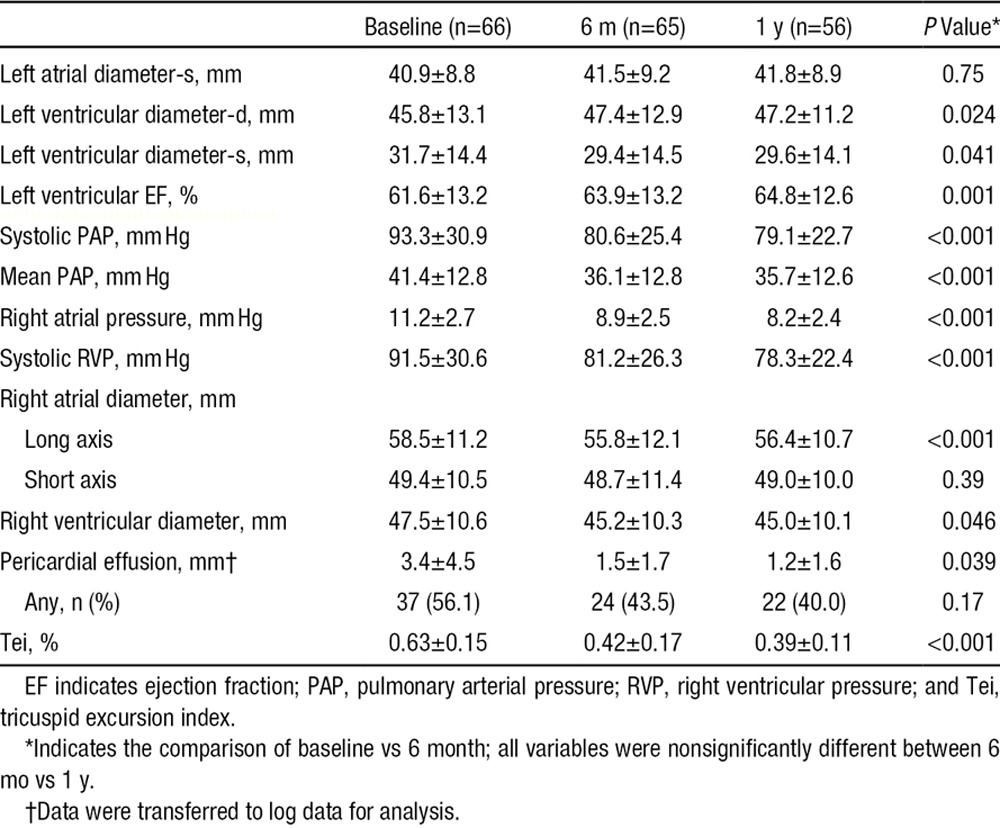

Table 2.

Echocardiographic Measurements at Baseline and 1 Year After PADN

Procedural Outcomes and Safety

The median (interquartile range) duration of ablation at 2.8±0.3 sites during the PADN procedure was 22 (11–38) minutes. During the procedure, 47 patients (71.2%) complained of chest pain (including 3 patients [4.5%] with severe chest pain), and 15 patients (22.7%) complained of a vague chest discomfort. All patients tolerated these symptoms without the need for additional sedative or analgesic agents. One patient developed sinus bradycardia from 88 to 43 bpm during the first ablation; the patient recovered after 3 minutes. A second PADN was attempted in 3 patients 2 to 4 days after the first attempt, during which patients were intolerable to dyspnea.

Hemodynamic Responses to the PADN Procedure

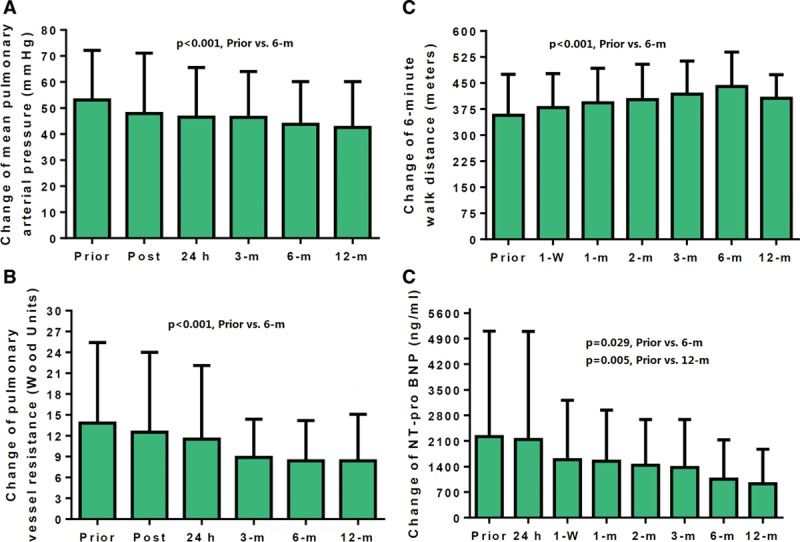

As shown in Figure 2A, the mean absolute reduction in mPAP was −5 mm Hg (12.8±9.2% reduction) immediately post PADN procedure and −6.6 mm Hg (12.2±2.6%) at 24 hours after PADN. Hemodynamic success was achieved in 62 patients (93.9%). On the basis of univariable analysis, the predictors of hemodynamic failure were sPAP (P=0.022), mPAP (P=0.011), and pericardial effusion (P=0.036).

Figure 2.

Dynamic changes in mean pulmonary arterial pressure (A), pulmonary vessel resistance (B), 6-minute walk distance (C), and N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT pro-BNP; D, after transferred to log data) levels. All variables improved significantly at the 6-month follow-up, without any additional significant change between the 6-month and the 1-year follow-up.

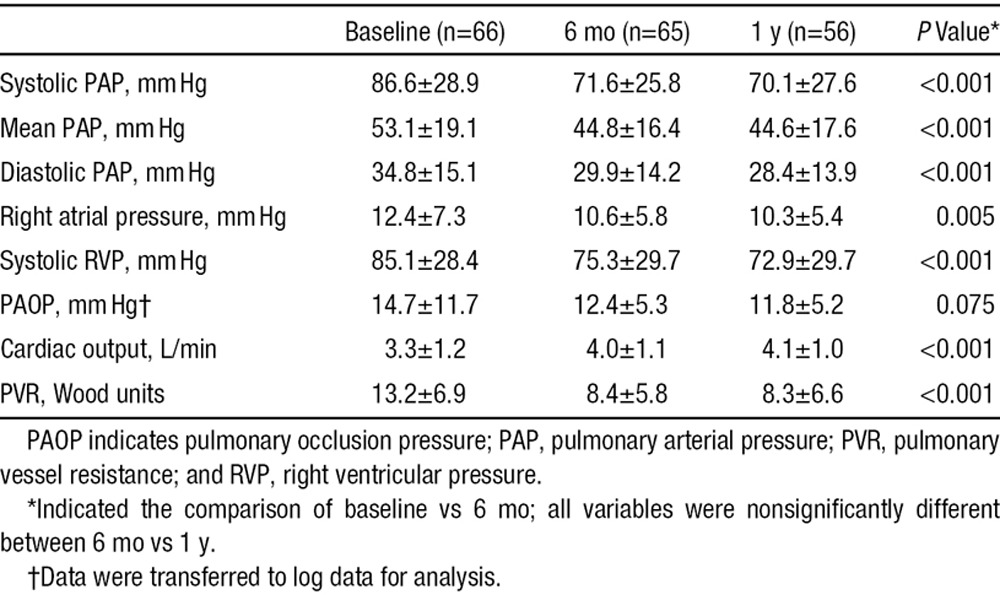

During the 6-month follow-up, there were significant reductions in sPAP, mPAP, diastolic PAP, RA pressure, and RV systolic pressure; and increment in cardiac output (all P<0.05) measured by either echocardiography (Table 2) or right heart catheterization (Table 3) all of which led to a significant decrease in PVR (Table 3; Figure 2B). However, there were no further improvements in values at 1-year follow-up compared with values at the 6-month follow-up (Table 3).

Table 3.

Right Heart Catheterization Measurements at Baseline and 6-Month and 1-Year Follow-Up

Exercise Capacity, Functional Class, and Cardiac Function

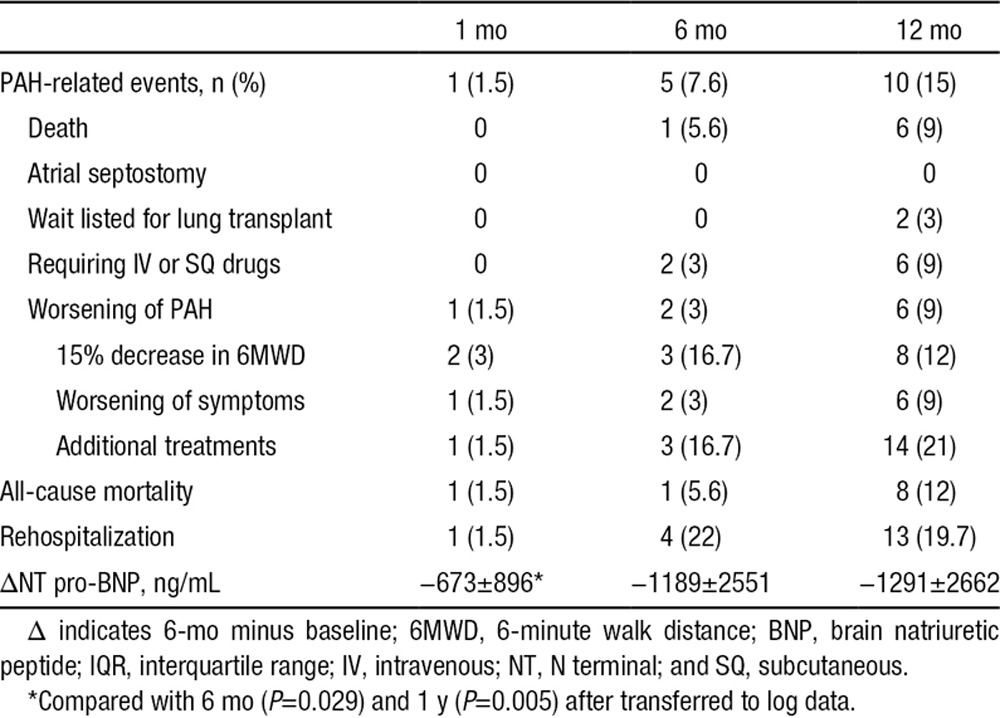

The 6MWD increased by a mean of 94±73 m (Figure 2C). The N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide value decreased from 2229±2922 ng/mL at baseline to 917±947 ng/mL at the 1-year follow-up (P<0.001; Figure 2D; Table 4). During the 6-month follow-up, the WHO functional class improved in 42 patients (63.6%); among 56 patients who survived for 1 year, the mean paired WHO class was 2.7±0.6 at baseline and 1.9±0.7 at the last follow-up (P<0.001).

Table 4.

Clinical Outcomes at the 1-Year Follow-Up in 66 Patients

Table 2 shows the average reduction in RA (the long axis but not the short axis) and RV diameter at the 6-month follow-up, and these were 1.98 and 2.21 mm, respectively, with simultaneously significant absorption of pericardial effusion and reduction of tricuspid excursion index. Notably, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension and LV ejection fraction increased from 45.8±13.1 mm and 61.6±13.2% at baseline to 47.4±12.9 mm (P=0.024) and 63.9±13.2% (P=0.001) at 6-month follow-up, respectively. In contrast, left ventricular end-systolic dimension decreased from 31.7±14.4 mm at baseline to 29.4±14.5 mm at the 6-month follow-up (P=0.041). Similar to changes in hemodynamics, no further improvements in right heat size and cardiac function were noted at the 1-year follow-up compared with values at the 6-month follow-up.

During the follow-up, PAH target drugs were prescribed in 9 patients (3 in group I, 5 in group II, and 1 chronic thromboembolic PH) according to patients’ expectation because of a slight nonsignificant increase in PVR after 6 months, and these drugs were then stopped after an average of 2.6 months since prescription.

Procedural Safety, Morbidity, and Mortality

There were no PA perforations or other major cardiac or vascular complications. On the magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography at the 6-month follow-up in 58 patients, no signs of thrombus or aneurysm formation were observed.

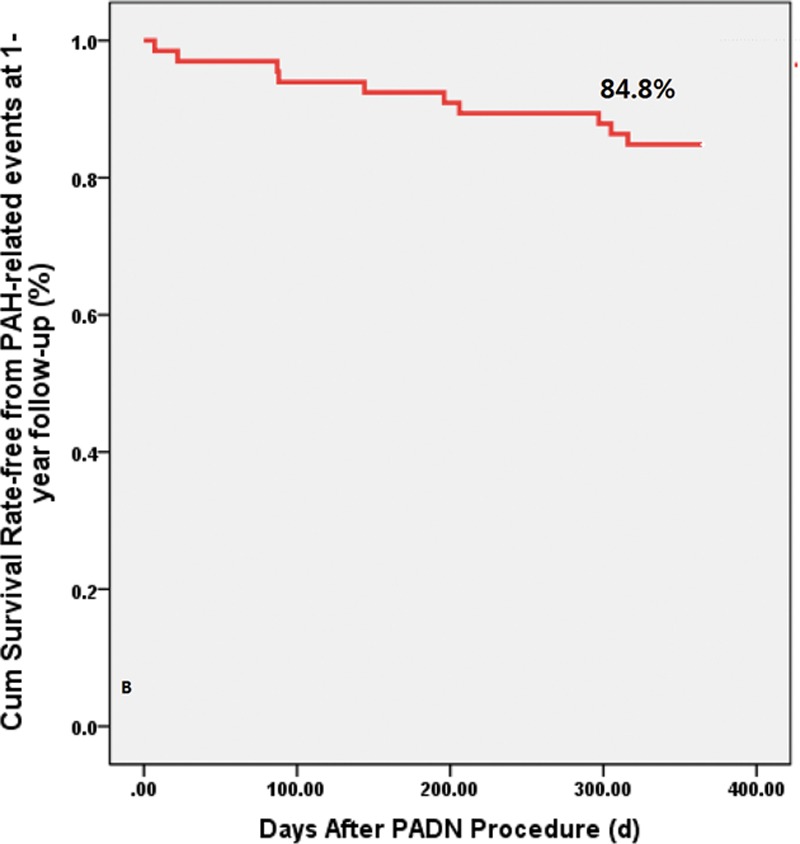

The 1-month and 6-month PAH-related event rates were 1.5% and 7.6%, respectively (Table 4). The median (interquartile range) follow-up was 652 (279–1130) days. As shown in Figure 3, PAH-related adverse events occurred in 10 patients during the 1-year follow-up (1-year 15.2% Kaplan–Meier estimated rate; Figure 3; Table 4). All-cause mortality occurred in 8 patients (1-year 12.1% Kaplan–Meier estimated rate) during the follow-up. Of the 8 deaths, 7 patients with group I PAH died after PADN: 1 with IPAH died of septic shock at 87 days, 2 with IPAH died of RV failure at 378 or 406 days, 1 with connective tissue disorders died of cerebral hemorrhage at 7 days, 2 with connective tissue disorders died of RV failure at 392 or 437 days, and 1 with congenital heart disease after surgical repair died of a traffic accident at 206 days. One patient with group II PAH died of RV failure at 433 days after the indexed procedure.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis. The 1-year Kaplan–Meier–estimated rate of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)–related events was 15.2%. PADN indicates pulmonary artery denervation.

Univariable analysis showed that patients without an event at the 1-year follow-up had a slower resting heart rate (P=0.043), lower PAP values (based on either right heart catheterization or echocardiography), less pericardial effusion (P=0.010), and higher 6MWD values (P=0.041) than the patients with events at the 1-year follow-up.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report hemodynamic, functional, and clinical responses to PADN in patients with PAH of different causes. The major finding is that the PADN procedure was associated with favorable 1-year outcomes, as evidenced by improvements in WHO functional class, 6MWD, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide levels, and a low rate of PAH-related events.

Neurohumoral activation in PAH is evidenced by increased circulating catecholamine levels,13 abnormally high muscle sympathetic nerve activity,13,14 and impaired heart rate variability,13–15 which forms the theoretical basis of using β-blockers16 and PADN7,8 to treat PAH. As a result, the success of PAH therapies has been measured in terms of reduction in PAP and PVR. The hemodynamic response to medication using target drugs within 4 weeks to 6 months varies widely,2,17,18 with a mean reduction in mPAP to <3 mm Hg. Compared with renal denervation, which did not result in immediate reduction in blood pressure,19 PADN results in an immediate reduction in PAP; the current results confirm our previous finding.7,9 Furthermore, we found that post-PADN reductions in sPAP (−8 mm Hg) and mPAP (−5 mm Hg) were sustained throughout the follow-up period. This implies that PADN might be beneficial for a wide variety of PAH causes. Notably, we also found no further reduction in PAP or further improvement in 6MWD after the 6-month follow-up, which might indicate that significant improvement in PA remodeling20 was achieved within 6 months after PADN treatment; however, this is not supported by extensive evidence. Repeated PADN combined with target drugs is postulated to provide more beneficial in patients with PAH.

The predictors of nonresponsiveness after medical treatment in patients with PAH have been poorly characterized. In our study, the nonresponder rate was 6.1% (n=4). Furthermore, we found that sPAP, mPAP, and pericardial effusion correlated with PADN procedure failure. An excessive increase in PAP reflects the severity of PAH.1 Pericardial fluid accumulation results in diastolic dysfunction because of impaired relaxation.15 In the 4 nonresponders, a gradual reduction in PAP was noted after the absorption of pericardial effusion for 3 months, suggesting an important role of pericardial effusion in treating PAH.7,15 However, given the small number of patients who did not respond to PADN in this study, additional data are required to determine the correlation of procedural outcomes with this novel approach to PAH.

Improvement in 6MWD has been used as the primary end point in most of the previous studies on PAH therapeutics, and a 15% reduction in 6MWD is one criterion of PAH worsening.1–6 Previous studies have reported a mean increase of +34 m in the 6MWD at a median 14.5-week follow-up,1–6,21 which is lower than that in our study (+94 m). In addition to improvements in hemodynamic function, WHO functional class, and cardiac function, our results demonstrated that PADN resulted in improvement in PA remodeling and exercise capacity. Importantly, there was no additional increase in 6MWD after the 6-month follow-up, as already discussed. Nonetheless, obtaining similar results from other centers and results from randomized trials may further support that patients with PH could benefit from PADN.

Clinical end points should be the primary goal of such studies,4,18 as reflected in a recent trial.21 However, the rate of PAH-related events after medication has not been clearly reported. The most recent study21 on the use of macitentan in group I PAH patients reported that the 6-month PAH-related event and all-cause mortality rates were 34.7% and 16.6%, respectively, significantly higher than those (12.8% and 5.1%, respectively) at 6 months after PADN. In this study, the 1-year Kaplan–Meier–estimated PAH-related event and mortality rates after PADN were 15.0% and 12.1%, still lower than those in previous trials, despite the enrollment of a high-risk cohort that was nonresponsive to numerous pharmacological agents. However, a randomized trial will ultimately be required to determine whether PADN provides meaningful clinical benefit to patients with group I PAH.

The innervation of the pulmonary artery is predominantly sympathetic22; the PA receives innervation from the right cardiac recurrent nerve, with branches forming an adventitial nerve plexus.22,23 The innervation starts at the bundles of large nerve trunks that diminish in size such that at the level of the arterioles, there is only a single fiber,23 a finding that reflects the methodology underlying PADN that involves ablation at 3 points around the distal main PA level in our consecutive patients.

Since the first report on surgical PA denervation by Juratsch et al8 in 1980, PADN was confirmed in our study7 and in the study by Rothman et al.20 Given the negative results after renal denervation for resistant hypertension, 1 merit of PADN was the immediate reduction in PAP after the procedure, which was sustained throughout the follow-up period. Furthermore, all PAH target drugs were discontinued after PADN because no improvement was observed in this patient population, and our results showed the net effects of PADN on the end points. Unfortunately, given the lack of a control group, any benefit observed in this study may be negated in larger randomized controlled, adequately powered trials.

Risk models for patients with PAH treated with medications have been established previously.24–27 A high on-treatment sPAP,25 elevated RA pressure,25 pericardial effusion,26 and resting heart rate cutoffs of 80 to 82 bpm for patients with IPAH27 are independently associated with increased mortality. Because of the small number of patients and only 10 PAH-related events in our report, the results of the univariable analysis showed that disease severity predicted the likelihood of increased rate of adverse events after PADN.

Limitations

This study was a nonrandomized and open-label study that may have a possible bias; the study also lacked a control group. Nonetheless, the favorable clinical outcomes after PADN are supported by objective improvements in PAPs, exercise capacity, and clinical events. Second, the small number of patients precluded detailed analysis of whether there were differential responses to PADN based on the PAH mechanism. Finally, all the PADN procedures were performed by 1 surgeon; nonetheless, our results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that in a high-risk patient population, PADN was safe and effective in reducing PAP and improving 6MWD and was associated with favorable clinical outcomes throughout the 1-year follow-up. Multicenter randomized trials are warranted to determine the use of PADN in patients with PAH.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance of Dr Duan, who worked as the Director of the Independent Clinical Event Committee. We also thank Ling Lin, Hai-Mei Xue, and Ying-Ying Zhao who collected all of the data for the study.

Sources of Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and Jiangsu Provincial Special Program of Medical Science (BL2013001), Nanjing, Jiangsu, China.

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Anderson JR, Nawarskas JJ. Pharmacotherapeutic management of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiol Rev. 2010;18:148–162. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181d4e921. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181d4e921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galiè N, Manes A, Negro L, Palazzini M, Bacchi-Reggiani ML, Branzi A. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:394–403. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp022. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galiè N, Brundage BH, Ghofrani HA, Oudiz RJ, Simonneau G, Safdar Z, Shapiro S, White RJ, Chan M, Beardsworth A, Frumkin L, Barst RJ Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Response to Tadalafil (PHIRST) Study Group. Tadalafil therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2009;119:2894–2903. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.839274. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.839274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaughlin VV, Badesch DB, Delcroix M, Fleming TR, Gaine SP, Galiè N, Gibbs JS, Kim NH, Oudiz RJ, Peacock A, Provencher S, Sitbon O, Tapson VF, Seeger W. End points and clinical trial design in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1 suppl):S97–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.007. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonneau G, Rubin LJ, Galiè N, Barst RJ, Fleming TR, Frost AE, Engel PJ, Kramer MR, Burgess G, Collings L, Cossons N, Sitbon O, Badesch DB PACES Study Group. Addition of sildenafil to long-term intravenous epoprostenol therapy in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:521–530. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-8-200810210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barst RJ, Oudiz RJ, Beardsworth A, Brundage BH, Simonneau G, Ghofrani HA, Sundin DP, Galiè N Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Response to Tadalafil (PHIRST) Study Group. Tadalafil monotherapy and as add-on to background bosentan in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:632–643. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.11.009. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SL, Zhang FF, Xu J, Xie DJ, Zhou L, Nguyen T, Stone GW. Pulmonary artery denervation to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension: the single-center, prospective, first-in-man PADN-1 study (first-in-man pulmonary artery denervation for treatment of pulmonary artery hypertension). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1092–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.075. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juratsch CE, Jengo JA, Castagna J, Laks MM. Experimental pulmonary hypertension produced by surgical and chemical denervation of the pulmonary vasculature. Chest. 1980;77:525–530. doi: 10.1378/chest.77.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen SL, Zhang YJ, Zhou L, Xie DJ, Zhang FF, Jia HB, Wong SS, Kwan TW. Percutaneous pulmonary artery denervation completely abolishes experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension in vivo. EuroIntervention. 2013;9:269–276. doi: 10.4244/EIJV9I2A43. doi: 10.4244/EIJV9I2A43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonelli AR, Mubarak KK, Li N, Carrie R, Alnuaimat H. Effect of balloon inflation volume on pulmonary artery occlusion pressure in patients with and without pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2011;139:115–121. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0981. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tei C, Nishimura RA, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. Noninvasive Doppler-derived myocardial performance index: correlation with simultaneous measurements of cardiac catheterization measurements. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1997;10:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(97)70090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breda AP, Pereira de Albuquerque AL, Jardim C, Morinaga LK, Suesada MM, Fernandes CJ, Dias B, Lourenço RB, Salge JM, Souza R. Skeletal muscle abnormalities in pulmonary arterial hypertension. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114101. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velez-Roa S, Ciarka A, Najem B, Vachiery JL, Naeije R, van de Borne P. Increased sympathetic nerve activity in pulmonary artery hypertension. Circulation. 2004;110:1308–1312. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140724.90898.D3. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140724.90898.D3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grigioni F, Potena L, Galiè N, Fallani F, Bigliardi M, Coccolo F, Magnani G, Manes A, Barbieri A, Fucili A, Magelli C, Branzi A. Prognostic implications of serial assessments of pulmonary hypertension in severe chronic heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:1241–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.06.015. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernandez AF, Hammill BG, O’Connor CM, Schulman KA, Curtis LH, Fonarow GC. Clinical effectiveness of beta-blockers in heart failure: findings from the OPTIMIZE-HF (Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure) Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.031. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW. 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009;119:1977–2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galiè N, Simonneau G, Barst RJ, Badesch D, Rubin L. Clinical worsening in trials of pulmonary arterial hypertension: results and implications. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010;16(suppl 1):S11–S19. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000370206.61003.7e. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000370206.61003.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O’Neill WW, D’Agostino R, Flack JM, Katzen BT, Leon MB, Liu M, Mauri L, Negoita M, Cohen SA, Oparil S, Rocha-Singh K, Townsend RR, Bakris GL SYMPLICITY HTN-3 Investigators. A controlled trial of renal denervation for resistant hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393–1401. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothman A, Arnold N, Chang W, Suvarna S, Elliot C, Condliffe R, Kiely D, Gunn J, Lawire A. Pulmonary artery denervation reduced pulmonary artery pressure and induces histological changes in an acute porcine model of pulmonary hypertension. Circulation Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e002569. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.002569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pulido T, Adzerikho I, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Galiè N, Ghofrani HA, Jansa P, Jing ZC, Le Brun FO, Mehta S, Mittelholzer CM, Perchenet L, Sastry BK, Sitbon O, Souza R, Torbicki A, Zeng X, Rubin LJ, Simonneau G SERAPHIN Investigators. Macitentan and morbidity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:809–818. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verity MA, Bevan JA. Fine structural study of the terminal effecror plexus, neuromuscular and intermuscular relationships in the pulmonary artery. J Anat. 1968;103(pt 1):49–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson JB. Nerve supply to the lungs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;119:785–802. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.119.5.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg-Maitland M, Frantz RP, Foreman AJ, Coffey CS, Frost A, Barst RJ, Badesch DB, Elliott CG, Liou TG, McGoon MD. Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL). Circulation. 2010;122:164–172. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.898122. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.898122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Tourneau T, Richardson M, Juthier F, Modine T, Fayad G, Polge AS, Ennezat PV, Bauters C, Vincentelli A, Deklunder G. Echocardiography predictors and prognostic value of pulmonary artery systolic pressure in chronic organic mitral regurgitation. Heart. 2010;96:1311–1317. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.186486. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.186486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinderliter AL, Willis PW, IV, Long W, Clarke WR, Ralph D, Caldwell EJ, Williams W, Ettinger NA, Hill NS, Summer WR, de Biosblanc B, Koch G, Li S, Clayton LM, Jöbsis MM, Crow JW. Frequency and prognostic significance of pericardial effusion in primary pulmonary hypertension. PPH Study Group. Primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84:481–484. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hildenbrand FF, Fauchère I, Huber LC, Keusch S, Speich R, Ulrich S. A low resting heart rate at diagnosis predicts favourable long-term outcome in pulmonary arterial and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. A prospective observational study. Respir Res. 2012;13:76. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-76. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]