Abstract

Depression and anxiety disorders have a substantial impact on the quality of life, the functioning and mortality of older adults with Parkinson’s disease (PD). The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the factors associated with the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders among individuals with PD aged 60 years and older. Following a literature search in PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and EMBASE, 5 articles met the inclusion criteria (adults aged 60 years and older, individuals with PD, and with depression and anxiety disorders, and English-language peer reviewed articles) and were included in this review. These studies were conducted in the U.S (n=3), in Italy (n=1) and the U.K (n=1). Findings indicated that autonomic symptoms, motor fluctuations, severity and frequency of symptoms, staging of the disease, and PD onset and duration were associated with the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders among older adults suffering from PD. Despite the limited number of studies included in the review, depression and anxiety disorders are often unrecognized and untreated and the comorbidity greatly exacerbates PD symptoms. The identification of factors associated with the development of depression and anxiety disorders could help in designing preventive interventions that would decrease the risk and burden of depression and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD.

Keywords: Parkinson’s Disease, depression, anxiety disorders, factors, older adults, systematic review

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder associated with high prevalence of neuropsychiatric features, which are disabling and often have an adverse impact over the course of the disease [1]. Depression and anxiety disorders are common neuropsychiatric syndromes among individuals with PD [2], with a prevalence ranging from 26% to 65% [3], [4], and [5]. Depression and anxiety disorders contribute to PD motor symptoms, motor complications, gait difficulties, freezing episodes, on-off fluctuations, cognitive impairment, disability, worsening quality of life and poor self-perceived health status [6], [7], [4], and [5]. Many studies have solely focused on the impact of depression in individuals with PD while overlooking the role of anxiety disorders [5]. According to Yamanishi et al. [5], and Quelhas & Costa [8], anxiety disorders, more so than depression, have a greater impact on the quality of life in PD. Recognizing that depression and anxiety disorders commonly co-occur in PD is essential since both conditions have been associated with negative PD health outcomes and increased mortality [9].

The literature on factors involved in the occurrence of depressive and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD is mixed and lacking with no consensus on which factors are the most important. Nègre-Pagès et al. [10] found that the factors most strongly related to anxiety symptoms in PD patients were female gender, younger age, and the presence of depressive symptoms. However, Quelhas & Costa [8] did not find any significant association between depression and anxiety disorders and demographic features, such as age and sex, or clinical features of PD, such as severity of motor symptoms or degree of disability. Other risk factors have also been mentioned in the literature relative to the development of depression and anxiety disorders among individuals with PD, including disease severity, impaired cognition, and older age, as well as social and personal factors [11]. Furthermore, two conflicting hypotheses have been suggested to explain the coexistence of depression and anxiety disorders in PD. One of the hypotheses indicated that there might be a common pathophysiological mechanism shared by depression and anxiety disorders since both conditions frequently co-occur, whereas the second hypothesis asserted that both conditions might have different mechanisms since they are not linked to the same PD features [12].

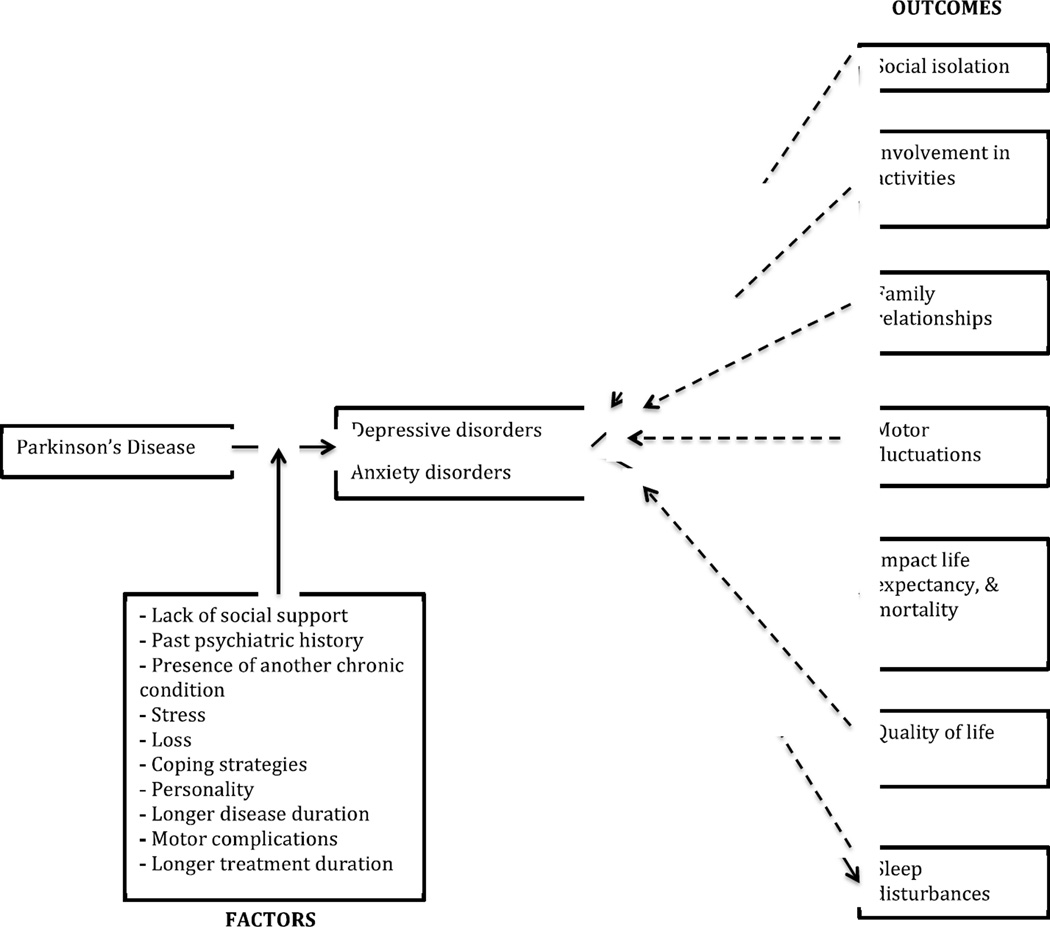

Given the difficulties in determining the factors associated with the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD, a model has been proposed (Figure 1) as a conceptual framework to outline a range of potential factors that may be involved in the development of depression and anxiety disorders in this population, as well as the possible outcomes resulting from the comorbidity of depression and anxiety disorders in PD. The development of depression and anxiety disorders may be triggered by various factors such as biological factors (comorbidity with another chronic illness, motor symptoms of PD), psychosocial factors (lack of social support, past psychiatric history, stressful life events, poor coping mechanisms), and personality types as well. The presence of depression and anxiety disorders in PD may lead to social isolation, reduced involvement in day-to-day activities, disruption in family relationships, increased motor fluctuations, sleep disturbances and mortality, and lower life expectancy and quality of life. The outcomes could in turn impact the disorders by exacerbating depression and anxiety symptoms, which may lead to a deterioration of PD condition.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for older adults with Parkinson’s disease: Probable factors and outcomes

Despite the growth of research dedicated to the non-motor symptomatology of PD, literature focused on the comorbidity between depression and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD remains sparse. Depression and anxiety disorders are the most common causes of psychosocial and functional impairment in late life; however, they are often undetected and untreated in older adults [13] and [14]. The difficulties in diagnosing these disorders are related not only to the atypical presentation of clinical features but also to the frequent presence of several medical disorders [15] and [16] including but not limited to PD. According to Pachana et al. [5], depression and anxiety disorders are frequently under-recognized and under-treated in PD, possibly due to clinical attention being focused mainly on motor symptoms of the disease, which may mask the psychiatric aspects of PD. Additional barriers to the recognition and treatment, highlighted in the literature, include the overlapping of the depression and anxiety symptoms with PD features [1], as well as social barriers like stigma.

The purpose of this review was to examine the literature in order to capture both the most common and distinguishing factors associated with the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD. Identifying the factors involved in the comorbidity of depression and anxiety disorders will help optimize the level of care of older adults with PD and improve their quality of life through appropriate and timely recognition and treatment of these disorders, or prevention.

Methods

A systematic review of research-based literature cataloged in PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and EMBASE was performed to identify the articles assessing the factors associated with depression and anxiety disorders among older adults, 60 years and older, suffering from PD. In addition, the reference lists of included studies as well as previous review studies were examined for inclusion of additional studies. The review was carried out from January 25 to March, 31 2013 and included the following subject terms and key words: ‘Parkinson’s Disease’, ‘Paralysis Agitans’, ‘anxiety disorder’, ‘anxiety neuroses’, ‘depressive disorder’, ‘depression’, ‘aged’, ‘elderly’, ‘risk factors’ to help identify the most pertinent literature (Cf. appendix which provides full search terms and strategies).

English language peer-reviewed studies analyzing factors associated with the manifestation of depression and anxiety disorders symptoms in older adults (aged 60 years and older) with a confirmed diagnosis of PD were included. Articles were excluded if they considered anxiety and depression disorders separately, if they were focused on therapeutic interventions and management of the disorders, or if they included other psychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders that could influence the presentation of depression and anxiety disorders in the research population.

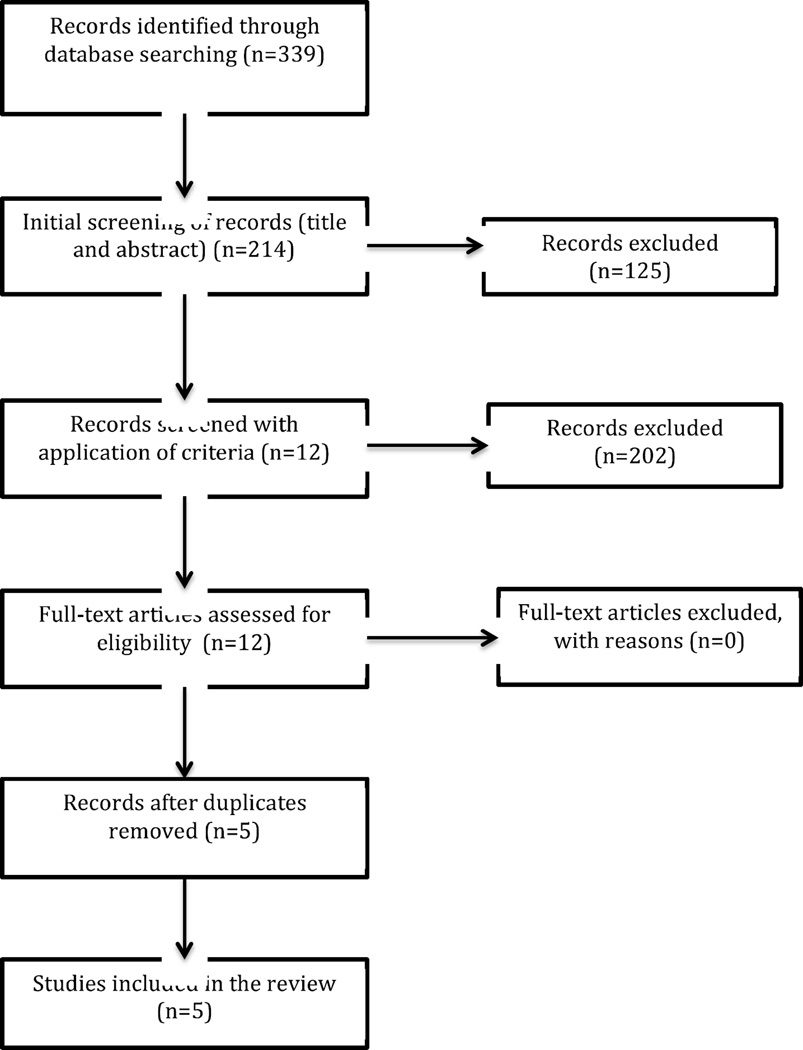

Inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to obtain the relevant articles are presented in Table 1. The electronic database searches identified 332 possible studies that were refined through the search process. Figure 1 outlines the full process for the selection of articles based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement [28]. In all, 125 articles were excluded based on the non-relevance of their titles and abstracts to the present review. After application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria and after removing duplicates, five studies were included in this review.

Table 1.

Literature search - Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Adults aged 60 years and older Individuals with Parkinson’s Disease, and with anxiety and depressive disorders English-language peer reviewed articles only |

Books, review articles, non published articles, editorials, (n=37) Case studies and studies with sample size less than 20 participants, (n=7) Studies with onset of depression and anxiety disorders before and after treatment, (n=5) Articles focused on anxiety exclusively, (n=25) Articles focused on depression exclusively, (n=17) Studies focused on therapies, interventions and management of depression and anxiety and/or on disorders scales, (n=51) Articles taking into account other psychiatric disorders and/or other neurodegenerative disorders (n=42) Articles on families/caregivers (n=5) Articles in other languages (n=13) |

Results

From the literature search, a total of 339 articles were identified using various search strategies with 28 in Embase, 26 in CINAHL, 111 in PsycINFO, and 174 in PubMed. An analysis and hand searching were performed to identify eligible papers based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Despite the small number of articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, conducted in the USA (n=3), Italy (n=1) and the UK (n=1), the studies displayed considerable heterogeneity in terms of participants characteristics, measurement tools and methods of analysis. Findings of the review are summarized based on the measures used (Table 2) and also based on the associated factors (Table 3).

Table 2.

Summary of Psychological and Parkinson’s Disease Measures

| Reference | Purpose | Sample Size and Characteristics |

Depression and Anxiety Measures | Parkinson’s Disease Measures |

Other Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nuti et al (2004) | Evaluate the rate of comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders in PD Correlate the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders with age, sex, laterality of motor symptomatology, clinical features, severity of disease, age of onset and PD duration and anti- Parkinson therapy. |

90 patients with idiopathic PD (48 men and 42 women, mean age 63.5±10.5, disease duration mean 5.3±1.7) 90 controls (sex, education and age matched and were healthy) MMSE>=23 |

|

H/Y mean 2.4±0.5 |

|

| Berrios et al (1995) | Identify significant associations between autonomic dysfunction and anxiety and depression |

32 subjects with PD (mean age 67.4 ±5.6) 32 age- and sex- matched healthy controls |

|

|

|

| Menza et al (1993) | Study the comorbidity of anxiety and depression in PD |

42 patients with PD (20 women and 22 men, mean age 66±11, disease duration 9.7±7.1) 21 control subjects with chronic debilitating osteoarthritis (9 women and 12 men) MMSE>= 24 |

|

H/Y mean 2.4±0.8 |

|

| Henderson et al (1992) | Investigate the prevalence, severity and relationship of depression and anxiety in PD patients |

164 PD patients (88 men and 76 women, mean age 67.1±9.2, duration of illness 8.6±5.7) 150 comparison subjects (patient’s spouse or close relative or neighbor of similar age) |

|

||

| Foster et al (2011) | Examine the relationship between the side of onset and the duration of PD on the development of anxiety and depression |

66 PD patients:

|

|

UPDRS mean 24.82±7.74 (LHO) and 27.66±11.67 (RHO) |

MMSE => Cognitive Impairment |

Note. ASS=Autonomic Symptoms Scale; BDI-II= Beck Depression Inventory-II; DSM-III-R= Diagnostic and Statistical Manual III Revised; DSSI= Delusions-Symptoms States Inventory; GDS= Geriatric depression scale; HAM-A= Hamilton Anxiety Scale; HAM-D= Hamilton Depression scale; HRSA= Hamilton Rating Scales for Anxiety; HRSD= Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression; H/Y staging= Hoehn and Yahr staging system; LHO= left hemibody onset of symptoms; MAACL-DYS= Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist - Dysphoria; MAACL-PASS= Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist - Positive Affect Sensation Seeking; MMSE= Mini Mental State Examination; RDRS-2=Rapid Disability Rating Scale-2; RHO= right hemibody onset of symptoms; SAS= Zung Self-Administered Anxiety Questionnaire; STAI= State-Trait Anxiety Inventory State; UPDRS – part III= Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III; Zung=Zung Depression Questionnaire

Table 3.

Summary of Findings by Psychosocial and Clinical Factors

| Author | Study Design, Country |

Subjects | Strength of Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| LATERALITY OF MOTOR SYMPTOMS | |||

| Nuti et al (2004) | Quantitative case control study Italy |

Outpatients of the Movement Disorders Unit | No correlation was found between laterality of motor signs and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders |

| Foster et al (2011) | Case control study USA |

Patients of the Movement Disorders Center | Patients of the Movement Disorders Center |

| CLINICAL FEATURES | |||

| Nuti et al (2004) | Quantitative case control study Italy |

Outpatients of the Movement Disorders Unit | No correlation was found between PD clinical features (akinetic rigid vs. tremor dominant) and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders |

| Henderson et al (1992) | Empirical study with self report questionnaire USA |

Community –dwelling older adults | Motor fluctuations associated with increase likelihood of depression and anxiety self report Association found between motor state and depression and anxiety disorders (r= 0.56, p<0.001) |

| SEVERITY OF PD | |||

| Nuti et al (2004) | Quantitative case control study Italy |

Outpatients of the Movement Disorders Unit | No correlation was found between the severity of the disease and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders |

| Menza et al (1993) | Case control study USA |

Outpatients of the Movement Disorders Clinic | Significant correlations were found between RDRS-2 and GDS (r= 0.48, p<0.01), Zung (r= 0.59, p<0.001), and SAS (r= 0.50, p<0.001) Correlation found between H/Y and SAS (r= 0.36, p<0.05), GDS (r= 0.41, p<0.01), and Zung (r= 0.39, p<0.01) |

| Henderson et al (1992) | Empirical study with self report questionnaire USA |

Community –dwelling older adults | Association found between frequency of symptoms and depression and anxiety disorders (r= 0.66, p<0.0001) |

| PD ONSET | |||

| Nuti et al (2004) | Quantitative case control study Italy |

Outpatients of the Movement Disorders Unit | No correlation was found between age of PD onset and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders |

| Henderson et al (1992) | Empirical study with self report questionnaire USA |

Community –dwelling older adults | Association found between PD onset and depression and anxiety disorders (r= 0.74, p<0.001) |

| PD DURATION | |||

| Nuti et al (2004) | Quantitative case control study Italy |

Outpatients of the Movement Disorders Unit | No correlation was found between disease duration and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders |

| Foster et al (2011) | Case control study USA |

Patients of the Movement Disorders Center | Significant positive correlations between PD duration and severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms [GDS (r=0.496, p=0.002), BDI-II (r=0.439, p=0.006) and the STAIS (r=0.417, p=0.009)] among RHO patients |

| ANTIPARKINSON THERAPY | |||

| Nuti et al (2004) | Quantitative case control study Italy |

Outpatients of the Movement Disorders Unit | No correlation was found between PD pharmacological therapy and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders |

| Menza et al (1993) | Case control study USA |

Outpatients of the Movement Disorders Clinic | No significant association was found between anti- Parkinson medications and depression and anxiety disorders |

| AUTONOMIC SYMPTOMS | |||

| Berrios et al (1995) | Prospective case control study Great Britain |

Subjects from the University of Cambridge Department of Psychiatry Parkinson’s Disease Project Database | Significant correlations were found between autonomic symptoms and depression (HRSD, P<0.01) and anxiety disorders (HRSA, P<0.01) |

Note. BDI-II= Beck Depression Inventory-II; GDS= Geriatric depression scale; HRSA= Hamilton Rating Scales for Anxiety; HRSD= Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression; H/Y staging= Hoehn and Yahr staging system; LHO= left hemibody onset of symptoms; RDRS-2=Rapid Disability Rating Scale-2; RHO= right hemibody onset of symptoms; SAS= Zung Self-Administered Anxiety Questionnaire; STAI or STAIS= State-Trait Anxiety Inventory State; Zung= Zung Depression Questionnaire

Study designs

The majority of the studies were case control studies focused on community-dwelling older adults with a confirmed diagnosis of PD and who were treated in Movement disorders clinics. The mean age of participants ranged from 63 years [17] to 68 years [18]. The sample sizes varied from 63 to 314 participants including the comparison groups.

Measures of psychological outcomes

Although the main outcomes of the studies were depression and anxiety disorders, the authors used different outcome measurement scales, composed of patient-rated and clinician-administered symptoms rating scales (Table 2). To confirm the classification of depression and anxiety disorders based on the measures mentioned in Table 2, formal psychiatric evaluation of the study participants was carried out in two studies using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) diagnostic criteria [20] and [17].

Measures of Parkinson’s disease

Four of the five studies assessed either motor symptoms severity or staging of PD using standard scales such as the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) – part III [19] and [17] and the Hoehn and Yahr (H/Y) [18], [20] and [17] respectively, while the Northwestern disability scale [18] was used to assess disability in activities of daily living (Table 2). However, the authors did not consistently report the scales preventing comparison between studies, and Henderson et al. [7] did not use any of these PD measures since his study design was based on self-report questionnaires.

Other measures

Prior to the enrollment, subjects in four of the studies were evaluated using different cognitive tests to screen for cognitive impairment [19], [20], [18] and [17] (Table 2).

Factors associated with depression and anxiety disorders

Factors related to the development of depression and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD were examined in this review (Table 3). Laterality of motor symptomatology was examined in two studies, [19] and [17]; however no significant association was found between the laterality of motor symptoms and the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders among PD subjects. Moreover, no significant association was observed between akinetic rigid and tremor dominant PD symptoms and the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders [17]. However, motor fluctuations were found to be associated with increased likelihood of depression and anxiety in self-reports [7]. While no association was observed between the severity of the disease and the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in Nuti et al. [17], Henderson et al. [7] and Menza et al. [20] found significant correlations with the severity of motor symptoms, H/Y stage of PD and the frequency of depression and anxiety disorders. PD onset, before age 60, was associated with increased prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms in Henderson et al. [7] but no such association was found in Nuti et al. [17]. Also, no correlations were found between PD duration and depression and anxiety disorders in one study [17], whereas a positive association was observed between the duration of the disease and the development of depression and anxiety disorders in Foster et al. [19]. Antiparkinsonian therapy was not correlated with the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders [20] and [17], but autonomic symptoms were associated with depression and anxiety disorders [18].

Discussion

The literature evaluating the factors associated with the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD remains relatively limited. Our systematic review identified five studies meeting the inclusion criteria with a study population comprised of participants with a mean duration of PD varying from 5.27 years to 9.7 years. Four studies used a case-control design study while one study used an empirical study design with self-report questionnaires. The main outcome of the studies was based on the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders. The results obtained regarding the association between influencing factors and the presence of depression and anxiety disorders in PD were mixed, which may be due to a combination of study factors including but not limited to the different assessment tools used, the statistical methods used, the type of study conducted, the sample size of the subjects, and the various PD measures utilized.. However, a general consistency in the data across studies was that variables related to PD, rather than demographics or pharmacologic treatments for PD, were associated with the presence of depression and anxiety disorders.

The analysis revealed that there was a significant association between autonomic symptoms, motor fluctuations, severity and frequency of motor symptoms, H/Y stage of the disease, age at PD onset and PD duration and the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD (Table 3). Not all studies reported each factor involved; one study addressed six factors out of seven [17] while another study addressed one out of seven factors [18]. Some studies have indicated that depression and anxiety disorders were associated with increased severity of the illness [21] and [12], younger PD onset age [21], [12], and [22] and longer disease duration [21] and [22], which support our analysis. Also, depression and anxiety disorders were found to be positively related to motor fluctuations and H/Y stage [6], [5], [23] and [24], which support the findings of our review. In addition, Verbaan et al. [25] reported that severe autonomic symptoms were associated with depression and psychiatric complications. Berrios et al. [18] suggested that anxiety and depressive disorders might be a proxy or “phenocopy” of autonomic dysfunction known to occur in PD, suggesting a shared or overlapping pathological basis. The possibility that there may be a shared pathological basis between PD and depression and anxiety disorders has growing support from many studies. The most persuasive include epidemiologic studies that show depression and anxiety are risk factors for PD [29], [30], [31] and [32]; pathology studies by Braak et al. [33] that demonstrate brain nuclei known to be involved in the production of dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine - the main chemical targets for pharmacological treatments of anxiety and depression - are systematically affected as PD progresses; and in vivo functional neuroimaging studies that show deficits in these same chemical pathways in subjects with PD [34] and [35]. Therefore, the findings in this review of an association between PD severity, motor fluctuations, and depression and anxiety disorders could be a consequence of a shared pathological process.

The measurement tools used to assess the outcome of interest were diverse (n=10) for depression and anxiety combined (Table 2). The scales used for assessing anxiety as well as depression yielded different results, and the discrepancy may be due to the fact that the scales measured different symptoms of the disorders and have different cut-off values. However, most of the anxiety measurement scales used in the studies are considered appropriate [26] for the screening of anxiety in the PD population by Lentjeens et al. [26], and in many recent studies, the State –Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) has been found as a useful screening assessment for both transient and ongoing anxiety in individuals with PD [5]. The scales used in the studies to measure depression among individuals with PD, particularly the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) and Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), have been found to be reliable and suitable scales in the context of PD [5], [21] and [36]. However, the measurement of depression and anxiety disorders using questionnaires [7] can be difficult as many standardized questionnaires contain questions that overlap with features of PD. In addition, there is also an overlapping content between depression and anxiety scales [5]. For these reasons, specific tools should be used to assess for depression and anxiety disorders in older adults with PD [9].

Furthermore, the studies in the review have used different methods of statistical analysis to assess the association between physiological factors and depression and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD, including logistic regression [17], correlational analyses [19], [7] and [20], Mann-Whitney test analysis [18], and ANOVA [7], and reported different magnitude of the association with different interpretations of the results. While the statistical tests used were appropriate for the designs of the studies, the differences in methodology and interpretations prevent direct comparison between studies..

Similarly, the reviewed studies used different control and comparison groups (Table 2), which were dependent on specific study questions and hypotheses and may not be free from selection bias. The differences observed between the study and comparison groups may be related to the fact that eligibility criteria of the studies were not uniformly applied across the groups, which could distort the association between the studied factors and the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders. In some cases the participants in the control groups may be less likely to be exposed to the factors studied than the participants in the study groups. For instance, in Berrios et al. [18], the control subjects, the healthy volunteers from the Medical Research Center, may be less prone to have autonomic symptoms compared to PD patients, which could distort the association between autonomic failure and depression and anxiety disorders since there may be a difference in the level of exposure between the two groups. Therefore, further studies on depression and anxiety disorders in PD using a population based study design or a national registry may be needed.

Variability in methods used could influence the generalizability of the studies. The results of the studies included in the review may not be generalizable because the sample sizes may not be representative of the PD population or of the non-PD population; patients who did not participate in the studies may have different characteristics compared to those who participated in the studies. Non-participants were likely to be sicker with declined function and worsening PD symptoms or greater PD severity than the subjects who took part in the studies. The samples were clinic-based samples, which may also create a bias; in clinic-based samples, it is not known whether the clinic attendance has any association with the factor being studied. The context of care may be different between clinics and the type of patients may also differ between clinics. The accessibility of care may vary between participants; probably participants from the clinics had different sociodemographic characteristics compared to PD individuals living in the communities. The limitation of the applicability of the studies is also related to the variability between countries because of the differences in the healthcare systems while taking into account the types of patients they are dealing with. Moreover, Henderson et al. [7] used self-report questionnaires that are subject to recall bias as well as reporting bias leading to a misclassification; PD patients may be misclassified as being more exposed to some factors than the participants in the control group or they may be more likely to report symptoms of depression and anxiety disorders than the control group.

The studies have also used diverse PD measures to assess PD severity and staging and motor symptoms (Table 2). Only Nuti et al. [17] differentiated between patients with and without on-off fluctuations, which is known to be a significant contributor to depression and anxiety disorders in PD [27]. The use of different PD measurement scales may have a differential impact on the relationship between the associated factors and the development of depression and anxiety in PD.

Our review highlights the scarcity of research on depression and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD. Moreover, the association of PD features with depression and anxiety disorders identified in this review is consistent with previous research that suggests an overlap in pathological features and neurochemical changes between disorders. Despite the challenges in identifying risk factors for depression and anxiety disorders in PD due to the complex interaction between disorders, opportunities exist for prevention. It is clear that depression and anxiety disorders co-occur commonly in older adults with PD and may occur at any stage of the illness. Up to 40% of individuals with PD suffer from anxiety disorders, which frequently coexist with depression [11]. Yet, depression and anxiety disorders among patients with PD are most often unrecognized and inadequately treated. Depression and anxiety are not identified in 50% of consultations on patients with PD done by neurologists: psychiatric symptoms may be missed when clinicians’ priorities are directed towards motor impairment [12]. PD patients may also be reluctant to report psychological symptoms, which in turn may contribute to the reduced diagnosis of depression and anxiety disorders in this population [12]. The co-occurrence of depression and anxiety disorders adversely affects the course of the disease, and leads to poor health related quality of life and increased mortality [9]. An awareness of the multiple factors associated with depression and anxiety disorders among older adults with PD could help in determining where and how to intervene, and to promote discussion about depression and anxiety disorders with individuals suffering from PD who may be at risk.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram based on PRISMA statement

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Dr. Jeanine Parisi for her thoughtful comments on the preliminary draft of this paper.

No funds were received for the study and no financial benefits have been derived by the authors from this study. This study has not been presented in any other form, and all the authors provided revisions of the paper and approved the final manuscript.

Appendix

Search Terms

Concept 1: Parkinson’s Disease

PubMed

Search terms: (Parkinson's Disease[MeSH Terms]) OR Parkinson Disease[Title/Abstract]) OR Paralysis Agitans[Title/Abstract])

PsycINFO

Search terms: (DE "Parkinson's Disease")

CINAHL

Search terms: (DE "Parkinson's Disease")

Concept 2: Anxiety Disorders

PubMed

Search terms: (anxiety disorders[MeSH Terms]) OR anxiety disorder[Title/Abstract]) OR anxiety neuroses[Title/Abstract]) OR anxiety states[Title/Abstract]) OR anxiety state[Title/Abstract]) OR neurotic anxiety state[Title/Abstract]) OR neurotic anxiety states[Title/Abstract])

PsycINFO

Search terms: (DE "Anxiety Disorders" OR DE "Acute Stress Disorder" OR DE "Castration Anxiety" OR DE "Death Anxiety" OR DE "Generalized Anxiety Disorder" OR DE "Obsessive Compulsive Disorder" OR DE "Panic Disorder" OR DE "Phobias" OR DE "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder" OR DE "Separation Anxiety")

CINAHL

Search terms: (DE "Anxiety Disorders" OR DE "Acute Stress Disorder" OR DE "Castration Anxiety" OR DE "Death Anxiety" OR DE "Generalized Anxiety Disorder" OR DE "Obsessive Compulsive Disorder" OR DE "Panic Disorder" OR DE "Phobias" OR DE "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder" OR DE "Separation Anxiety")

Concept 3: Depressive disorders

PubMed

Search terms: (depressive disorders[MeSH Terms]) OR depressive disorder[Title/Abstract]) OR depression[Title/Abstract]) OR depressions[Title/Abstract]) OR melancholia[Title/Abstract]) OR melancholias[Title/Abstract]) OR endogenous depression[Title/Abstract]) OR depressive neuroses[Title/Abstract]) OR depressive syndrome[Title/Abstract]) OR depressive syndromes[Title/Abstract]) OR neurotic depression[Title/Abstract]) OR neurotic depressions[Title/Abstract]) OR unipolar depression[Title/Abstract]) OR unipolar depressions[Title/Abstract])

PsycINFO

Search terms: (DE "Major Depression" OR DE "Anaclitic Depression" OR DE "Dysthymic Disorder" OR DE "Endogenous Depression" OR DE "Postpartum Depression" OR DE "Reactive Depression" OR DE "Recurrent Depression" OR DE "Treatment Resistant Depression")

CINAHL

Search terms: DE "Major Depression" OR DE "Anaclitic Depression" OR DE "Dysthymic Disorder" OR DE "Endogenous Depression" OR DE "Postpartum Depression" OR DE "Reactive Depression" OR DE "Recurrent Depression" OR DE "Treatment Resistant Depression"

Concept 4: Risk factors

PubMed

Search terms: (risk factors[MeSH Terms]) OR risk factor[Title/Abstract])

PsycINFO

Search terms: (DE "Risk Factors" OR DE "Predisposition" OR DE "Protective Factors" OR DE "Psychosocial Factors" OR DE "Risk Assessment" OR DE "Sociocultural Factors")

CINAHL

Search terms: DE "Risk Factors" OR DE "Predisposition" OR DE "Protective Factors" OR DE "Psychosocial Factors" OR DE "Risk Assessment" OR DE "Sociocultural Factors"

Concept 6: Older adults

PubMed

Search terms: (Aged[MeSH Terms]) OR elderly[Title/Abstract]

PsycINFO

Search terms: DE "Aging" OR DE "Aging in Place" OR DE "Physiological Aging"

CINAHL

Search terms

DE "Aging" OR DE "Aging in Place" OR DE "Physiological Aging"

EMBASE

Search terms: (“Parkinson disease” AND “Anxiety Disorders” AND “Depressive Disorders”)

Search strategies

PubMed

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 AND Concept 3 => 103 articles

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 AND Concept 3 AND Concept 4 => 11 articles

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 AND Concept 3 AND Concept 6 => 53 articles

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 AND Concept 3 AND Concept 4 AND Concept 6 => 7 articles

PsycINFO

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 => 82 results

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 AND Concept 3 => 27 articles

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 AND Concept 3 AND Concept 4 => 2 articles

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 AND Concept 3 AND Concept 4 AND Concept 6 => 0 article

CINAHL

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 => 20 results

Concept 1 AND Concept 3 => 4 articles

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 AND Concept 3 => 1 article

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 AND Concept 4 => 1 article

Concept 1 AND Concept 2 AND Concept 3 AND Concept 4 AND Concept 6 => 0 article

EMBASE

(“Parkinson disease” AND “Anxiety Disorders” AND “Depressive Disorders”) => 28 articles

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest/Financial disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Qureshi SU, Amspoker AB, Calleo JS, Kunik ME, Marsh L. Anxiety disorders, physical illnesses, and health care utilization in older male veterans with Parkinson disease and comorbid depression. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2012 Dec;25(4):233–239. doi: 10.1177/0891988712466458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernandez HH. Updates in the medical management of Parkinson disease. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012 Jan;79(1):28–35. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.78gr.11005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leentjens AF, Dujardin K, Marsh L, Martinez-Martin P, Richard IH, Starkstein SE. Symptomatology and markers of anxiety disorders in Parkinson's disease: a cross-sectional study. Mov Disord. 2011 Feb 15;26(3):484–492. doi: 10.1002/mds.23528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pontone GM, Williams JR, Anderson KE, Chase G, Goldstein SA, Grill S, et al. Prevalence of anxiety disorders and anxiety subtypes in patients with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2009 Jul 15;24(9):1333–1338. doi: 10.1002/mds.22611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamanishi T, Tachibana H, Oguru M, Matsui K, Toda K, Okuda B, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with Parkinson's disease. Intern Med. 2013;52(5):539–545. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.8617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dissanayaka NN, Sellbach A, Matheson S, O'Sullivan JD, Silburn PA, Byrne GJ, et al. Anxiety disorders in Parkinson's disease: prevalence and risk factors. Mov Disord. 2010 May 15;25(7):838–845. doi: 10.1002/mds.22833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson R, Kurlan R, Kersun JM, Como P. Preliminary examination of the comorbidity of anxiety and depression in Parkinson's disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1992 Summer;4(3):257–264. doi: 10.1176/jnp.4.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quelhas R, Costa M. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009 Fall;21(4):413–419. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2009.21.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pachana NA, Egan SJ, Laidlaw K, Dissanayaka N, Byrne GJ, Brockman S, et al. Clinical issues in the treatment of anxiety and depression in older adults with Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2013 Dec;28(14):1930–1934. doi: 10.1002/mds.25689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Negre-Pages L, Grandjean H, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Montastruc JL, Fourrier A, Lepine JP, et al. Anxious and depressive symptoms in Parkinson's disease: the French cross-sectionnal DoPaMiP study. Mov Disord. 2010 Jan 30;25(2):157–166. doi: 10.1002/mds.22760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schrag A. Psychiatric aspects of Parkinson’s disease - an update. J Neurol. 2004 Jul;251(7):795–804. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kano O, Ikeda K, Cridebring D, Takazawa T, Yoshii Y, Iwasaki Y. Neurobiology of depression and anxiety in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2011;2011:143547. doi: 10.4061/2011/143547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agronin ME, Maletta GJ. Principle and practice of geriatric psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mellilo KD, Houde SC. Geropsychiatric and mental health nursing. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003 Mar;58(3):249–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaudreau SA, O’Hara R. Late-life anxiety and cognitive impairment: a review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008 Oct;16(10):790–803. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31817945c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuti A, Ceravolo R, Piccinni A, Dell'Agnello G, Bellini G, Gambaccini G, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in a population of Parkinson's disease patients. Eur J Neurol. 2004 May;11(5):315–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2004.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berrios GE, Campbell C, Politynska BE. Autonomic failure, depression and anxiety in Parkinson's disease. Br J Psychiatry. 1995 Jun;166(6):789–792. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foster PS, Drago V, Crucian GP, Sullivan WK, Rhodes RD, Shenal BV, et al. Anxiety and depression severity are related to right but not left onset Parkinson’s disease duration. J Neurol Sci. 2011 Jun 15;305(1–2):131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menza MA, Robertson-Hoffman DE, Bonapace AS. Parkinson’s disease and anxiety: comorbidity with depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1993 Oct 1;34(7):465–470. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dissanayaka NN, O’Sullivan JD, Silburn PA, Mellick GD. Assessment methods and factors associated with depression in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2011 Nov 15;310(1–2):208–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pontone GM, Williams JR, Anderson KE, Chase G, Goldstein SR, Grill S, et al. Anxiety and self-perceived health status in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2011 May;17(4):249–254. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menza MA, Sage J, Marshall E, Cody R, Duvoisin R. Mood changes and “on-off” phenomena in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008 Oct 30;23(14):2015–2025. doi: 10.1002/mds.870050210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Storch A, Schneider CB, Wolz M, Sturwald Y, Nebe A, Odin P, et al. Nonmotor fluctuations in Parkinson disease: severity and correlation with motor complications. Neurology. 2013 Feb 26;80(9):800–809. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318285c0ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verbaan D, Marinus J, Visser M, van Rooden SM, Stiggelbout AM, van Hilten JJ. Patient-reported autonomic symptoms in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007 Jul 24;69(4):333–341. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266593.50534.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leentjens AF, Dujardin K, Marsh L, Martinez-Martin P, Richard IH, Starkstein SE, et al. Anxiety rating scales in Parkinson's disease: critique and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2008 Oct 30;23(14):2015–2025. doi: 10.1002/mds.22233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leentjens AF, Dujardin K, Marsh L, Martinez-Martin P, Richard IH, Starkstein SE. Anxiety and motor fluctuations in Parkinson's disease: a cross-sectional observational study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2012 Dec;18(10):1084–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009 Jul 21;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiba M, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, McDonnell SK, Peterson BJ, Ahlskog JE, et al. Anxiety disorders and depressive disorders preceding Parkinson's disease: a case-control study. Mov Disord. 2000 Jul;15(4):669–677. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200007)15:4<669::aid-mds1011>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weisskopf MG, Chen H, Schwarzschild MA, Kawachi I, Ascherio A. Prospective study of phobic anxiety and risk of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2003 Jun;18(6):646–651. doi: 10.1002/mds.10425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bower JH, Grossardt BR, Maraganore DM, Ahlskog JE, Colligan RC, Geda YE, et al. Anxious personality predicts an increased risk of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010 Oct 15;25(13):2105–2113. doi: 10.1002/mds.23230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shen CC, Tsai SJ, Perng CL, Kuo BI, Yang AC. Risk of Parkinson disease after depression: a nationwide population-based study. Neurology. 2013 Oct 22;81(17):1538–1544. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a956ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Braak H, Ghebremedhin E, Rub U, Bratzke H, Del Tredici K. Stages in the development of Parkinson's disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 2004 Oct;318(1):121–134. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-0956-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Remy P, Doder M, Lees A, Turjanski N, Brooks D. Depression in Parkinson's disease: loss of dopamine and noradrenaline innervation in the limbic system. Brain. 2005 Jun;128(Pt 6):1314–1322. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Black KJ, Hershey T, Hartlein JM, Carl JL, Perlmutter JS. Levodopa challenge neuroimaging of levodopa-related mood fluctuations in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005 Mar;30(3):590–601. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams JR, Hirsch ES, Anderson K, Bush AL, Goldstein SR, Grill S, et al. A comparison of nine scales to detect depression in Parkinson disease: which scale to use? Neurology. 2012 Mar 27;78(13):998–1006. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824d587f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]