Abstract

Purpose/Objective(s)

ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235 demonstrated that standardized uptake value (SUV) on post-treatment [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) correlates with survival in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This secondary analysis determines if SUV of regional lymph nodes (RLNs) on post-treatment FDG-PET correlates with patient outcomes.

Methods and Materials

Included for analysis were patients treated with concurrent chemoradiation therapy using radiation doses ≥60 Gy, with identifiable FDG-avid RLNs (distinct from primary tumor) on pre-treatment FDG-PET, and post-treatment FDG-PET data. ACRIN Core Laboratory SUV measurements were used. Event time was calculated from the date of post-treatment FDG-PET. Local-regional failure was defined as failure within the treated RT volume and reported by the treating institution. Statistical analyses included Wilcoxon signed-rank test, Kaplan-Meier curves (log rank test), and Cox proportional hazards regression modeling.

Results

Of 234 trial-eligible patients, 139 (59%) had uptake in both primary tumor and RLNs on pre-treatment FDG-PET, and had SUV data from post-treatment FDG-PET. Maximum SUV was greater for primary tumor than for RLNs before treatment (p<0.001), but not different post-treatment (p=0.320). Post-treatment SUV of RLNs was not associated with overall survival. However, elevated post-treatment SUV of RLNs, both the absolute value and the percent residual activity compared to the pre-treatment SUV, were associated with inferior local-regional control (p<0.001).

Conclusions

High residual metabolic activity in RLNs on post-treatment FDG-PET is associated with worse local-regional control. Based on these data, future trials evaluating a radiotherapy boost should consider inclusion of both primary tumor and FDG-avid RLNs in the boost volume to maximize local-regional control.

Introduction

Outcomes with concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy (CRT) for Stage III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remain poor, with the highest reported prospective median survival of 28.7 months after 60 Gy of radiation with concurrent chemotherapy(1). Current clinical trial efforts to improve survival include targeted systemic therapy for patients with actionable mutations and hypofractionated radiation dose escalation to residual [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid tumor sub-volumes, such as is being tested in Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) trials 1308 and 1106, respectively.

Another approach is to apply stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) as a boost following CRT for inoperable Stage III disease. One published retrospective series delivered SBRT as a boost to the primary tumor only, leaving involved nodes outside of the boost volume(2). Surgical data from several clinical trials involving induction CRT for advanced-stage NSCLC support the notion that pathologic clearance of regional lymph nodes (RLNs) is associated with significantly improved local-regional control (LRC) and improved overall survival (OS)(3). For patients who receive definitive CRT, it is not known if the response of the RLNs (defined as mediastinal and hilar nodes) differs compared to the response of the primary lung tumor, and if lack of complete response in RLNs correlates with worse outcomes. Knowing this information would help to formulate clinical trials using SBRT to target residual disease after CRT.

The American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) (now ECOG-ACRIN) and RTOG (now NRG Oncology) performed a cooperative, prospective Phase II clinical trial (ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235) in which patients with locally advanced NSCLC receiving definitive CRT underwent both pre-treatment and post-treatment positron emission tomography (PET) with FDG. The primary objective of the trial was to determine the relationship between post-treatment SUV of the primary tumor and overall survival(4). The initial results of this trial were reported previously and demonstrated that residual tumor maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) >5 on post-treatment FDG-PET was prognostic for decreased OS(4). Here, we present a subset analysis of ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235, with the intent to compare the metabolic response of the RLNs versus the primary lung tumor as measured by FDG-PET, and to determine the relative prognostic value of RLN SUVmax as assessed by post-treatment FDG-PET.

Methods and Materials

Patients and Trial Design

ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235 was a phase II prospective study that accrued 250 patients with inoperable Stage IIB/III NSCLC. Details of CRT, FDG-PET technique and PET image assessment were described previously(4). Briefly, treatment consisted of definitive, concurrent, platinum-based doublet CRT with radiation to doses ≥ 60 Gy. Patients underwent pre-treatment FDG-PET (which could have been up to 6 weeks prior to enrollment), and post-treatment FDG-PET at approximately 14 weeks (range 12 to 16 weeks) after radiotherapy (and at least 4 weeks after the completion of adjuvant chemotherapy, if applicable). Each participating institution obtained institutional review board approval prior to enrolling patients, and all patients provided written, study-specific informed consent. All participating centers performed FDG-PET on ACRIN-qualified scanners, using pre-specified protocols, which have been previously described(4).

FDG-PET Image Evaluation

In ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235, both local interpretations performed at the participating institution and central interpretations performed by an expert nuclear medicine physician at the ACRIN Core Laboratory were collected. For purposes of our analysis, the core laboratory SUV measurements specific to the primary lung tumor and RLNs were used. For each region, the maximum SUV (SUVmax) within the region of interest (ROI) was reported. Peak SUV (SUVpeak) measurements are not reported because the primary trial results showed that SUVmax and SUVpeak were highly correlated and yielded similar primary endpoint findings(4).

The reporting schema of the central review from the ACRIN Core Laboratory was such that pre-treatment FDG-PET scans where RLN involvement could not be distinguished from the primary tumor, or where RLNs were judged to be “definitely not tumor” or “probably not tumor” did not have RLN SUV recorded. Therefore, because the goal of this analysis was to evaluate RLN metabolic activity, quantified using SUV, only those patients with identifiable FDG-avid RLNs, distinct from the primary tumor, on pre-treatment FDG-PET were included for analysis.

Patient Outcomes

The outcomes tested in this analysis are overall survival (OS) and local-regional control (LRC). In ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235, LRC was determined by the treating institution. A local-regional failure was defined as a failure within the irradiated volume. For the purposes of this analysis, outcome information was correlated with the post-treatment RLN FDG PET results.

Statistical Analysis

Distributional summaries of primary tumor and RLN SUVmax were prepared for pre-treatment, post-treatment, and percent (%) residual SUVmax. Percent residual SUVmax was defined as the post-treatment value divided by the pre-treatment value multiplied by 100. Comparisons of these SUV measures between the primary tumor and RLNs were conducted using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves (using the log-rank test) and Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to examine the association between RLN SUVmax and patient outcomes, with separate results reported by SUV measure (post-treatment vs. % residual) and outcome (OS vs. LRC). Of note, post-treatment RLN SUVmax was the primary PET parameter of interest and % residual RLN SUVmax was the secondary parameter of interest. For both outcomes, event time was calculated from the date of the post-treatment FDG-PET scan. Both univariate and multivariate models were fit. In the multivariate models, potential confounders were adjusted for, including age, sex, baseline Zubrod performance status, baseline clinical stage, chemotherapy regimen and radiation dose (Gy). Model diagnostics related to the Cox model were assessed, and appropriate interaction terms with time were included in the model for variables that violated the proportional hazards assumption(5).

In addition to continuous post-treatment RLN SUVmax, binary thresholds of 3.5, 5 and 7 were used in order to align with results reported previously for the trial(4). For both post-treatment RLN SUVmax and % residual RLN SUVmax, an optimal binary threshold was also identified by means of recursive partitioning in a conditional inference framework(6).

As two patient outcomes (OS and LRC) and two SUV measures (post-treatment RLN SUVmax and % residual RLN SUVmax) were examined, time to event analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons by means of the Bonferroni correction in order to control the family-wise error rate. P-values below the adjusted threshold of 0.05/4=0.0125 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R v3.1.0 (R project, http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Patients

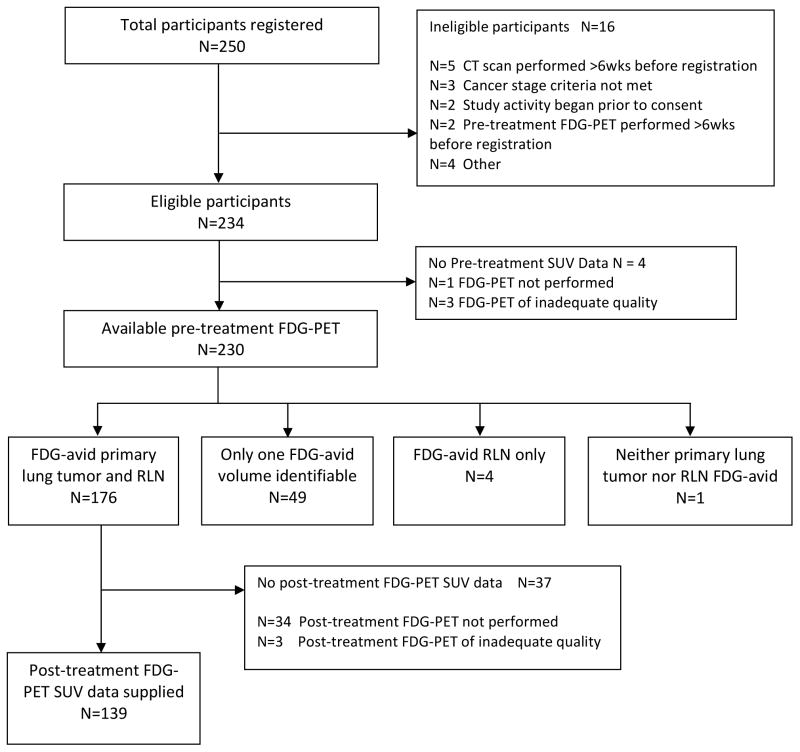

250 patients were accrued to ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235. Of these, 233 eligible participants underwent pre-treatment FDG-PET, 176 (76%) of whom were identified as having distinct FDG uptake within the primary tumor and identifiable RLNs. Those patients whose nodal tumor volumes were not distinguishable from primary tumor volumes on pre-treatment FDG-PET (i.e., central primary tumors), such that only one FDG-avid volume was identifiable, were excluded from analysis (Figure 1). Among patients with identifiable FDG-avid primary tumor and RLNs, 139 (79%) also underwent post-treatment FDG-PET and had available SUV data. Reasons for not having evaluable post-treatment FDG-PET can be found within appendix materials of the initial publication, with the most common reason being patient death (4). These 139 patients comprise the current analysis set (Figure 1). Note that 6 patients (4%) were excluded from LRC analyses because of unavailable LRC outcome (n=4) or because local-regional failure occurred before post-treatment PET (n=2). Patient demographics and treatment details are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Analysis flowchart of patients included in the current study.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and clinical characteristics, both for all eligible participants and for the subset of analyzed participants.

| Demographic or clinical characteristic | Eligible cases (N=234) | Analysis set (N=139) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | ||||

| Median | 65 | 65 | ||

| Range | (36–85) | (36–82) | ||

|

| ||||

| N | % | N | % | |

|

| ||||

| Gender | ||||

|

| ||||

| Male | 150 | 64.10 | 87 | 62.59 |

|

| ||||

| Female | 84 | 35.90 | 52 | 37.41 |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 7 | 2.99 | 4 | 2.88 |

|

| ||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 217 | 92.74 | 132 | 94.96 |

|

| ||||

| Unknown | 10 | 4.27 | 3 | 2.16 |

|

| ||||

| Race 1 | ||||

|

| ||||

| White | 171 | 73.08 | 110 | 79.14 |

|

| ||||

| African American | 27 | 11.54 | 10 | 7.19 |

|

| ||||

| Asian | 31 | 13.25 | 18 | 12.95 |

|

| ||||

| Other | 9 | 3.85 | 4 | 2.88 |

|

| ||||

| Clinical stage 2 | ||||

|

| ||||

| IIB | 9 | 3.85 | 3 | 2.16 |

|

| ||||

| IIIA | 118 | 50.43 | 81 | 58.27 |

|

| ||||

| IIIB | 107 | 45.73 | 55 | 39.57 |

|

| ||||

| Performance status | ||||

|

| ||||

| 0 (fully active) | 102 | 43.59 | 71 | 51.08 |

|

| ||||

| 1 (ambulatory, capable of light work) | 132 | 56.41 | 68 | 48.92 |

|

| ||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||

|

| ||||

| Carboplatin/paclitaxel | 95 | 40.60 | 54 | 38.85 |

|

| ||||

| Cisplatin/etoposide | 35 | 14.96 | 26 | 18.71 |

|

| ||||

| Other | 89 | 38.03 | 59 | 42.45 |

|

| ||||

| Data not available | 15 | 6.41 | 0 | 0.00 |

|

| ||||

| Radiation dose, Gy | ||||

|

| ||||

| <50 | 9 | 3.85 | 0 | 0.00 |

|

| ||||

| 50–60 Gy | 11 | 4.70 | 5 | 3.60 |

|

| ||||

| 60–70 Gy | 146 | 62.39 | 104 | 74.82 |

|

| ||||

| >=70 Gy | 52 | 22.22 | 28 | 20.14 |

|

| ||||

| Data not available | 16 | 6.84 | 2 | 1.44 |

Multiple races could be endorsed by a single participant, such that the total over all options may sum to greater than 100%.

One participant with clinical stage recorded only as stage III was grouped into the stage IIIB row.

SUV Measurements

Pre-treatment SUVmax was significantly higher in primary tumors compared to the RLNs (median of 12.5 vs. 9.8, p<0.001) (Supplementary Table 1). In contrast, there was no difference in the post-treatment SUVmax measurements (median of 2.9 vs. 2.8, p=0.320). SUVmax decreased significantly for both the primary tumor and the RLNs after definitive CRT, with a lower % residual SUVmax observed in the primary tumor (Supplementary Table 1).

Post-treatment RLN SUV and Patient Outcomes

Among this set of patients with identifiable pre-treatment FDG-avid primary tumors and RLNs, who also had available post-treatment FDG-PET, a statistically significant association was identified between post-treatment RLN SUVmax and LRC, even after adjusting for potentially important confounders (Table 2). % residual RLN SUVmax was also significant in the multivariate model using the adjusted significance threshold (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the results of univariate and multivariate Cox regression models.

| Patient Outcome | Post-treatment RLN SUV measure | N | Hazard ratio 1 (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Overall Survival | SUVmax (continuous) 2 | 139 | 1.051 (0.962, 1.148) | 0.273 |

| 137 | 1.053 (0.964, 1.150) | 0.249 | ||

|

| ||||

| % Residual SUVmax 3 (continuous) | 139 | 1.052 (0.981, 1.129) | 0.153 | |

| 137 | 1.061 (0.984, 1.144) | 0.121 | ||

|

| ||||

| Local-Regional Control | SUVmax (continuous) 2 | 133 | 1.145 (1.048, 1.252) | 0.003 † |

| 131 | 1.214 (1.094, 1.346) | <0.001 † | ||

|

| ||||

| % Residual SUVmax 3 (continuous) | 133 | 1.122 (1.016, 1.238) | 0.023 | |

| 131 | 1.149 (1.037, 1.275) | 0.008† | ||

In each cell, univariate hazard ratios are presented above and multivariate hazard ratios are presented below. The multivariate model adjusted for the following covariates: age, sex, baseline performance status, baseline clinical stage, chemotherapy regimen and radiation dose.

Hazard ratios correspond to a 1-unit increase in RLN SUVmax.

% Residual RLN SUVmax is defined as (post/pre)*100. Hazard ratios correspond to a 10% increase in the % Residual RLN SUVmax.

Analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons. P-value is below the adjusted significance threshold of 0.0125.

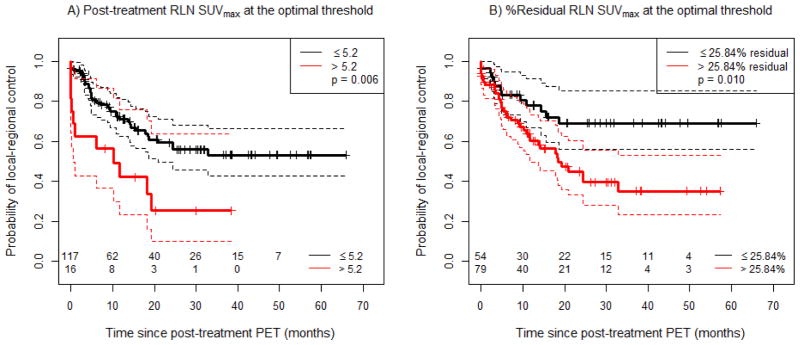

Recursive partitioning analysis identified the optimal threshold for post-treatment RLN SUVmax as 5.2. Patients with post-treatment RLN SUVmax above this threshold exhibited significantly worse LRC compared with patients with lower values (p=0.006) (Figure 2A). Using the thresholds identified as significant for survival that were published in the original ACRIN6668/RTOG 0235 report(4), we found that RLN SUVmax greater than 5 (p=0.019), and greater than 7 (p=0.050) were of marginal significance for poorer LRC at the adjusted significance threshold (Supplemental Figure 2A, B). Using a threshold of 3.5, we found no significant association with LRC (p=0.193), and thus these data are not shown.

Figure 2.

Local-regional control (LRC) as a function of post-treatment RLN SUVmax, using varying cut-offs. A) Post-treatment RLN SUVmax with a cut-off at the optimal threshold, and B) % Residual RLN SUVmax with a cut-off at the optimal threshold. Solid lines correspond to the respective Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves, and dashed lines correspond to 95% confidence intervals of the respective curves.

For % residual RLN SUVmax, the optimal threshold identified on recursive partitioning analysis was 25.84%. Patients with % residual RLN SUVmax above this threshold exhibited significantly worse LRC compared with patients who had a lower % residual RLN SUVmax (p=0.010, Figure 2B). Interestingly, while patients with post-treatment RLN SUVmax >5.2 had the worst local-regional control, we found that patients with RLN SUVmax ≤5.2 could be further stratified by % residual RLN SUVmax above or below 25.84% (p = 0.004, Supplementary Figure 1).

Dichotomized post-treatment RLN SUVmax remained a significant predictor of LRC after adjustment for potential confounders in a multivariate Cox model (Table 3). Patients with RLN SUVmax above the optimal threshold of 5.2 had a 2.7-fold increase in the risk of local-regional failure over the observed follow-up period compared to those with SUVmax below the threshold (p=0.005). A similar multivariate Cox model using % residual RLN SUVmax is shown in Supplementary Table 2, and demonstrates a 2.8-fold increase in the risk of local-regional failure for patients with % residual RLN SUVmax >25.84%, compared to those with % residual RLN SUVmax ≤25.84% (p = 0.004).

Table 3.

Summary for local-regional control (LRC) of the results of a multivariate Cox regression model with post-treatment RLN SUVmax dichotomized at the optimal threshold.

| Parameter | Estimate (SE) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): continuous | 0.015 (0.019) | 1.015 (0.978, 1.053) | 0.434 |

| Sex: female (vs. male) | 0.009 (0.301) | 1.009 (0.560, 1.821) | 0.975 |

| Baseline performance status: ambulatory, capable of light work (vs. fully active) | 0.841 (0.460) | - 1 | 0.068 |

| Baseline performance status * Time (months) | −0.095 (0.047) | - 1 | 0.045 |

| Baseline clinical stage: IIIB (vs. IIB/IIIA) | 1.351 (0.596) | - 1 | 0.023 |

| Baseline clinical stage * sqrt(Time) (months) | −0.582 (0.217) | - 1 | 0.007 |

| Radiotherapy dose (Gy): continuous | 0.096 (0.065) | - 1 | 0.141 |

| Radiotherapy dose (Gy) * sqrt(Time) (months) | −0.057 (0.027) | - 1 | 0.034 |

| Chemotherapy regimen: Cisplatin + Etoposide (vs. Carboplatin + Paclitaxel) | −0.442 (0.540) | 0.643 (0.223, 1.852) | 0.413 |

| Chemotherapy regimen: Other (vs. Carboplatin + Paclitaxel) | −0.398 (0.594) | - 1 | 0.503 |

| Chemotherapy regimen: Other * sqrt(Time) (months) | 0.351 (0.198) | - 1 | 0.076 |

| Post-treatment RLN SUVmax: > 5.2 (vs. ≤ 5.2) | 0.994 (0.353) | 2.702 (1.352, 5.402) | 0.005 † |

A single hazard ratio is not reported as the specified covariate is time-varying, thus implying that the hazard ratio varies over time.

Analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons. P-value is below the adjusted significance threshold of 0.0125.

sqrt = Square root transformation

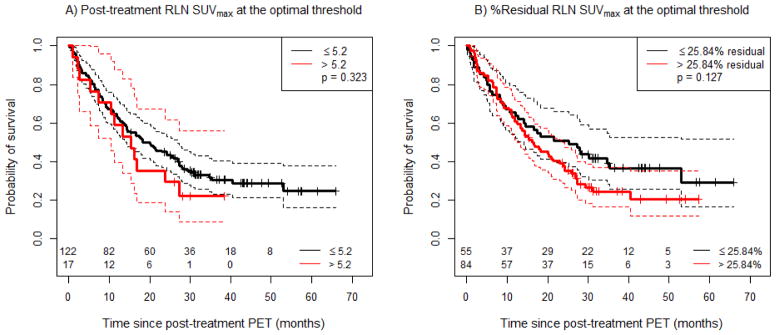

No statistically significant association was observed between post-treatment RLN SUVmax and OS. This held for RLN SUVmax as a continuous variable (Table 2), as well as across the variously defined thresholds of 3.5 (not shown), 5 and 7 (Supplemental Figure 2C, D). There was also no association observed between % residual RLN SUVmax and overall survival (Table 2). As no threshold for post-treatment SUVmax or % residual RLN SUVmax existed that provided significant separation in overall survival (and thus the optimal threshold by recursive binary partitioning is undefined), the same optimal thresholds identified for the LRC outcome (RLN SUVmax of 5.2 and % residual RLN SUVmax of 25.84%) were used for OS for comparison (Figure 3A, B).

Figure 3.

Overall survival (OS) as a function of post-treatment RLN SUVmax, using various cut-offs. A) Post-treatment RLN SUVmax with a cut-off at the same optimal threshold derived for local-regional control, and B) % Residual RLN SUVmax with a cut-off at the same optimal threshold derived for local-regional control. Solid lines correspond to the respective Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves, and dashed lines correspond to 95% confidence intervals of the respective curves.

Discussion

ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235 was a non-randomized Phase II study in which patients with locally advanced NSCLC received pre-treatment FDG-PET, definitive concurrent CRT with RT doses of ≥60 Gy and then underwent FDG-PET between 12 and 16 weeks post therapy. The initial report of this trial confirmed the prognostic value of elevated post-therapy tumor FDG uptake in predicting overall survival. However, the initial analysis considered the primary lung tumor SUV and response, and did not evaluate pre- or post-treatment SUV of the RLNs. The current study presents prospective evidence that metabolic response—specifically of involved RLNs—is an important risk factor for local-regional failure after definitive CRT in patients with locally advanced NSCLC.

In this secondary analysis, we found that high post-treatment RLN SUVmax was associated with worse LRC but not with overall survival. Although recursive partitioning analysis revealed specific optimal cut-offs of post-treatment RLN SUVmax of 5.2 and % residual RLN SUVmax of 25.84%, we caution against the use of these exact cut-offs in clinical decision making until they are prospectively validated. Based on our results, thresholds of 5 for post-treatment RLN SUVmax and 25% for %residual RLN SUVmax would be sensible values to use in confirmatory studies. In contrast to the original report, which showed that primary tumor SUVmax on post-treatment FDG-PET is associated with overall survival, the current analysis included a smaller number of patients who had both pre- and post-treatment primary lung tumor and RLNs volumes reported, and therefore may not have had sufficient statistical power to detect a difference in overall survival.

Because we were interested in ascertaining the importance of RLN response to chemoradiation as determined by FDG-PET, the current analysis included only patients who had SUV values recorded for distinct RLN volumes on pre-treatment FDG-PET. The current analysis was thus limited in patient number by having to exclude those patients with only one FDG-avid tumor volume identifiable on pre-treatment FDG-PET (i.e., central primary tumors).

Complete pathologic tumor response and LRC after definitive CRT for locally advanced NSCLC are known to be associated with improved overall survival(7–10). LRC with current doses employed for definitive treatment of locally advanced NSCLC remains suboptimal, with 25–35% of patients experiencing local-regional failure as a part of disease recurrence(1, 11). In the current study, local-regional recurrence was reported as an aggregate, and did not specify whether failure was in the primary tumor or RLNs. Therefore, we were not able to determine the association between post-treatment RLN SUV and control of local disease, regional nodal disease, or both. Nevertheless, because post-treatment RLN SUV remained significantly associated with LRC on multivariate analysis, these data show that better metabolic response of the previously involved RLNs is an important outcome for definitive CRT. These data support those in a retrospective report by Guerra et al demonstrating a similar association between high post-RT SUVmax specifically of the RLNs and higher risk of death and recurrence(12). Supplemental Table 3 shows the primary findings of prior published studies evaluating the prognostic value of FDG-PET in patients with locally advanced NSCLC treated with definitive CRT(4, 12–24). Studies published prior to 2000 are nicely summarized in a review by deGeus-Oei et al (25).

Efforts to improve LRC and therefore overall survival include radiation dose-escalation. RTOG 0617, a phase III randomized trial, which tested the efficacy of dose-escalated 74 Gy versus standard 60 Gy with concurrent chemotherapy with or without cetuximab for patients with Stage III NSCLC, paradoxically showed lower disease-free survival, overall survival, and LRC in the experimental higher-dose arm(1). The explanation for this wholly unexpected result is being meticulously sought. It may relate to toxicity associated with large radiation volumes resulting in inadvertently high doses of radiation to normal organs including the heart, in a unique population of patients who, because of the same risk factors predisposing many of them to develop NSCLC (most notably smoking), also have significant cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities.

Knowing that radiation dose escalation using conventional fractions is not beneficial, current trials in development include other methods of escalating radiation dose. One approach is SBRT, a technique that delivers high doses of radiation to well-defined volumes, with millimeter precision and steep gradients, allowing rapid fall-off of dose away from the tumor. SBRT has revolutionized the use of radiotherapy for early stage NSCLC, with local control rates as high as 95% and low toxicity rates(26–28).

Given the success of SBRT in patients with early-stage lung cancers, many investigators are currently considering the use of an SBRT boost following an initial course of conventionally fractionated radiation therapy as a means to improve LRC in locally-advanced disease. Feddock et al. reported results of a prospective trial of 26 patients with Stage II or III NSCLC who received a median of 59.4 Gy to the primary tumor and involved nodes followed by an SBRT boost to the residual primary tumor volume(2). The intent of this prospective trial was to deliver biological equivalent doses of 100 Gy10 and to assess toxicity. The results indicate that SBRT can be safely delivered to peripheral primary tumors following CRT, with hilar tumors requiring more careful fractionation schemes to avoid excess toxicity. Local control with short follow-up was 82.9%, though the authors caution that follow up data are pre-mature. A phase I institutional trial was recently launched at Emory University, delivering 44 Gy in 2 Gy daily fractions with concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy, to be followed by an SBRT boost to both the primary tumor and RLNs(29). This trial is in its early phases.

RTOG 1106 is an ongoing Phase II randomized trial comparing standard definitive CRT versus adapted dose-escalated hypofractionated radiotherapy using mid-course FDG-PET to adapt radiotherapy volumes(30). The investigational arm of this trial delivers at least 60 Gy to the initially involved nodal clinical target volume, and dose-escalated radiation to as high as 80.4 Gy to persistently metabolically active nodal regions on mid-therapy FDG-PET. This trial is designed to demonstrate the utility, or lack thereof, of adapting radiotherapy based on response to therapy using mid-treatment FDG-PET.

Evidence exists that pathological complete response in the RLNs is important for overall survival. Emami et al. showed improved in-field control when nodal regions with gross disease were adequately covered with radiation doses >60 Gy(31). Results of the Intergroup 0139 trial in which patients with stage IIIA lymph node-positive NSCLC were randomized to receive either induction CRT with 45 Gy prior to surgical resection, or definitive CRT to 60 Gy demonstrated that patients in the induction therapy arm with pathologic clearance of the lymph nodes at the time of surgery had significantly better survival than those with persistent nodal disease. RTOG 0229, in which patients received full-dose radiation (60.2 Gy) to areas of gross disease and chemotherapy prior to surgery demonstrated similar findings with improved survival in patients with nodal clearance(3). This trial, in which involved lymph node regions received the higher dose of radiation, had an increased rate of pathologic nodal clearance (63%) compared to Intergroup 0139 (40%), supporting the notion that higher doses to involved lymph nodes may result in better nodal clearance rates(3, 11). Based on these data and this secondary analysis of ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235, eradicating tumor within regional lymph nodes is important for LRC and, most likely, for overall survival as well.

Conclusions

These data from a prospective Phase II multi-institutional trial with central imaging review suggest that persistent regional nodal FDG uptake on post-treatment PET is a marker of poor LRC. Clinical trials to escalate radiation dose in locally advanced NSCLC are currently being defined, and these data support the inclusion of FDG-avid regional nodes.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Local-regional control (LRC) as a function of both post-treatment RLN SUVmax, and percent residual RLN SUV max, dichotomized at ≤ or > 5.2, and ≤ or > 25.84%, respectively. Solid lines correspond to the respective Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves, and dashed lines correspond to 95% confidence intervals of the respective curves.

Supplemental Figure 2. (A and B) Local-regional control (LRC) as a function of post-treatment RLN SUVmax, using varying cut-offs. A) Post-treatment RLN SUVmax with a cut-off of 5, B) Post-treatment RLN SUVmax with a cut-off of 7; and (C and D) overall survival (OS) as a function of post-treatment RLN SUVmax, using various cut-offs. C) Post-treatment RLN SUVmax with a cut-off of 5, D) Post-treatment RLN SUVmax with a cut-off of 7. Solid lines correspond to the respective Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves, and dashed lines correspond to 95% confidence intervals of the respective curves.

Supplementary Table 1. Distributional summary of SUV data based on timing of PET for both the primary tumor and RLNs.

Supplementary Table 2. Summary for local-regional control (LRC) of the results of a multivariate Cox regression model with percent (%) residual RLN SUVmax dichotomized at the optimal threshold.

Supplementary Table 3. Prior published studies evaluating the prognostic value of FDG-PET in patients with locally advanced NSCLC undergoing definitive CRT.

Summary.

Patients with locally advanced NSCLC continue to have poor outcomes. ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235 is a prospective non-randomized trial in which patients with locally advanced NSCLC received pre-treatment FDG-PET, definitive chemoradiation and post-treatment FDG-PET. In this secondary analysis, we found that high SUV in the regional lymph nodes on post-treatment FDG-PET was independently associated with poor local-regional control. These data support future efforts to improve metabolic response of the RLNs as one means of improving LRC.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the American College of Radiology Imaging Network grants U01 CA079778 and CA080098 and Radiation Therapy Oncology Group U10 CA21661 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

The manuscript’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Conflicts of Interest: None

This work was presented in abstract form as an oral presentation at the 2014 Annual ASTRO Meeting in San Francisco, CA.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bradley JD, Paulus R, Komaki R, et al. A randomized phase III comparison of standard-dose (60 Gy) versus high-dose (74 Gy) conformal chemoradiotherapy with or without cetuximab for stage III non-small cell lung cancer: Results on radiation dose in RTOG 0617. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feddock J, Arnold SM, Shelton BJ, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy can be used safely to boost residual disease in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:1325–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suntharalingam M, Paulus R, Edelman MJ, et al. RTOG 0229: A Phase II Trial of Neoadjuvant Therapy with Concurrent Chemotherapy and Full Dose Radiotherapy (XRT) followed by Resection and Consolidative Therapy for LA-NSCLC. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:S111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machtay M, Duan F, Siegel BA, et al. Prediction of survival by [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer undergoing definitive chemoradiation therapy: results of the ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235 trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3823–3830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.5947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anonymous. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hothorn T, Hornik K, Zeileis A. Unbiased recursive partitioning: A conditional inference framework. J Comput Graph Stat. 2006;15:651–674. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez CA, Bauer M, Edelstein S, et al. Impact of tumor control on survival in carcinoma of the lung treated with irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1986;12:539–547. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(86)90061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaake-Koning C, Schuster-Uitterhoeve L, Hart G, et al. Prognostic factors of inoperable localized lung cancer treated by high dose radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1983;9:1023–1028. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(83)90392-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saunders MI, Barltrop MA, Rassa PM, et al. The relationship between tumor response and survival following radiotherapy for carcinoma of the bronchus. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1984;10:503–508. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(84)90030-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mauguen A, Pignon J-P, Burdett S, et al. Surrogate endpoints for overall survival in chemotherapy and radiotherapy trials in operable and locally advanced lung cancer: a re-analysis of meta-analyses of individual patients’ data. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:619–626. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70158-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albain KS, Swann RS, Rusch VW, et al. Radiotherapy plus chemotherapy with or without surgical resection for stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:379–386. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60737-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez Guerra JL, Gladish G, Komaki R, et al. Large decreases in standardized uptake values after definitive radiation are associated with better survival of patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2012;53:225–233. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.096305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Baardwijk A, Bosmans G, Dekker A, et al. Time trends in the maximal uptake of FDG on PET scan during thoracic radiotherapy. A prospective study in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Radiother Oncol J Eur Soc Ther Radiol Oncol. 2007;82:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Yu J, Meng X, et al. Prognostic value of serial [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT uptake in stage III patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated by concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Eur J Radiol. 2011;77:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Massaccesi M, Calcagni ML, Spitilli MG, et al. 18F-FDG PET-CT during chemo-radiotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: the early metabolic response correlates with the delivered radiation dose. Radiat Oncol Lond Engl. 2012;7:106. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Usmanij EA, de Geus-Oei L-F, Troost EGC, et al. 18F-FDG PET early response evaluation of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer treated with concomitant chemoradiotherapy. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 2013;54:1528–1534. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.116921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeong J-U, Chung W-K, Nam T-K, et al. Early metabolic response on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron-emission tomography/computed tomography after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for advanced stage III non-small cell lung cancer is correlated with local tumor control and survival. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:2517–2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulger S, Demirci NY, Eroglu FN, et al. High FDG uptake predicts poorer survival in locally advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer patients undergoing curative radiotherapy, independently of tumor size. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140:495–502. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1591-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vera P, Mezzani-Saillard S, Edet-Sanson A, et al. FDG PET during radiochemotherapy is predictive of outcome at 1 year in non-small-cell lung cancer patients: a prospective multicentre study (RTEP2) Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41:1057–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2687-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang W, Liu B, Fan M, et al. The early predictive value of a decrease of metabolic tumor volume in repeated (18)F-FDG PET/CT for recurrence of locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer with concurrent radiochemotherapy. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84:482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtipek E, Çayc M, Düzgün N, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT Mean SUV and Metabolic Tumor Volume for Mean Survival Time in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2015 doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohri N, Duan F, Machtay M, et al. Pretreatment FDG-PET Metrics in Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: ACRIN 6668/RTOG 0235. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toma-Dasu I, Uhrdin J, Lazzeroni M, et al. Evaluating tumor response of non-small cell lung cancer patients with 18F-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography: potential for treatment individualization. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91:376–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yossi S, Krhili S, Muratet J-P, et al. Early Assessment of Metabolic Response by 18F-FDG PET During Concomitant Radiochemotherapy of Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Is Associated With Survival: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Clin Nucl Med. 2015;40:e215–221. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000000615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Geus-Oei L-F, van der Heijden HFM, Corstens FHM, et al. Predictive and prognostic value of FDG-PET in nonsmall-cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Cancer. 2007;110:1654–1664. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanic S, Paulus R, Timmerman RD, et al. No clinically significant changes in pulmonary function following stereotactic body radiation therapy for early- stage peripheral non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG 0236. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:1092–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timmerman R, Paulus R, Galvin J, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy for inoperable early stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303:1070–1076. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsen JR, Robinson CG, El Naqa I, et al. Dose-response for stereotactic body radiotherapy in early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:e299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anonymous. Standard Radiation Therapy Combined With High Dose, Ablative Radiation in Patients With Advanced Lung Cancer That Cannot be Removed by Surgery - Full Text View. ClinicalTrials.gov.

- 30.Anonymous. Study of Positron Emission Tomography and Computed Tomography in Guiding Radiation Therapy in Patients With Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer - Full Text View. ClinicalTrials.gov.

- 31.Emami B, Mirkovic N, Scott C, et al. The impact of regional nodal radiotherapy (dose/volume) on regional progression and survival in unresectable non-small cell lung cancer: an analysis of RTOG data. Lung Cancer Amst Neth. 2003;41:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Local-regional control (LRC) as a function of both post-treatment RLN SUVmax, and percent residual RLN SUV max, dichotomized at ≤ or > 5.2, and ≤ or > 25.84%, respectively. Solid lines correspond to the respective Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves, and dashed lines correspond to 95% confidence intervals of the respective curves.

Supplemental Figure 2. (A and B) Local-regional control (LRC) as a function of post-treatment RLN SUVmax, using varying cut-offs. A) Post-treatment RLN SUVmax with a cut-off of 5, B) Post-treatment RLN SUVmax with a cut-off of 7; and (C and D) overall survival (OS) as a function of post-treatment RLN SUVmax, using various cut-offs. C) Post-treatment RLN SUVmax with a cut-off of 5, D) Post-treatment RLN SUVmax with a cut-off of 7. Solid lines correspond to the respective Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves, and dashed lines correspond to 95% confidence intervals of the respective curves.

Supplementary Table 1. Distributional summary of SUV data based on timing of PET for both the primary tumor and RLNs.

Supplementary Table 2. Summary for local-regional control (LRC) of the results of a multivariate Cox regression model with percent (%) residual RLN SUVmax dichotomized at the optimal threshold.

Supplementary Table 3. Prior published studies evaluating the prognostic value of FDG-PET in patients with locally advanced NSCLC undergoing definitive CRT.