Abstract

Here, we illustrate the complexity of ILC subsets, we discuss novel functions, focusing on emerging ILCs crosstalk with other immune cells and the microbiota. Furthermore, we highlight recent insights into the development of ILCs, the common pathways they share as well as points of divergence between ILC groups and subsets.

Introduction

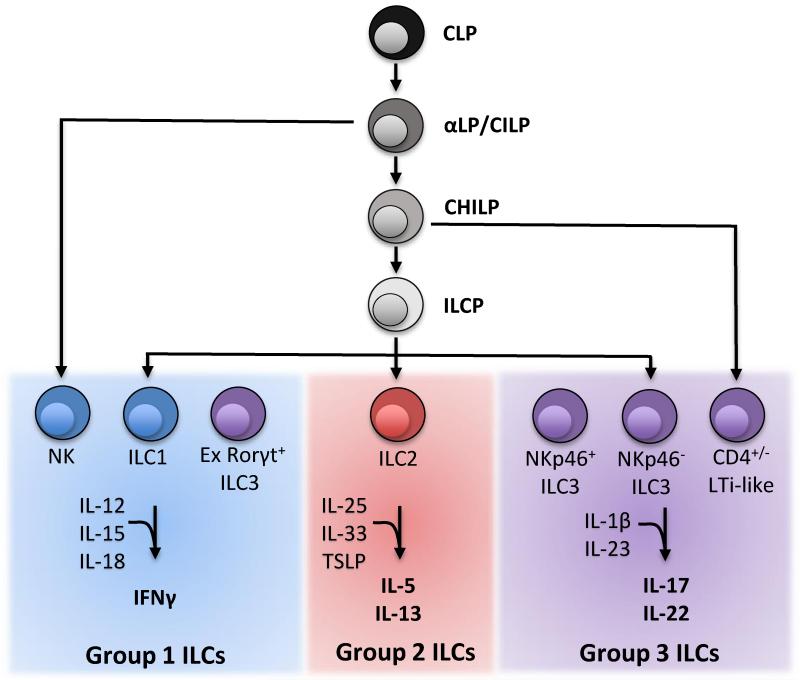

Innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are a heterogeneous population of immune cells with two defining characteristics: 1) they have lymphoid origin, differentiating from the common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) and dependent on IL-2Rγc signaling. 2) They lack antigen-specific receptors and therefore do not require the RAG proteins for development. Present throughout the body and enriched at mucosal surfaces in both human and mouse, ILCs promptly produce effector cytokines in response to stimulation with STAT-activating cytokines and alarmins of the IL-1 family [1, 2, and 3]. Based upon similarities in effector cytokine secretion and developmental requirements, ILCs can be divided into three populations: group 1 ILCs, group 2 ILCs, and group 3 ILCs (Figure 1). IL-12, IL-21 IL-15 and IL-18 activate group 1 ILCs to produce interferon γ (IFN-γ); this group includes subsets such as T-bet+Eomes+ NK cells and T-bet+Eomes− ILC1. IL-25, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), and IL-33 trigger GATA-3+ ILC2 to produce type 2 cytokines such as IL-5 and IL-13. IL-23 and IL-1 prompt Rorγt+ ILC3 to produce IL-22 and/or IL-17. In adult, ILC3 subsets include lymphoid tissue-inducer like (LTi-like) cells and others that express the NK cell marker NKp46. As potent innate cytokine producers that respond to changes in the cytokine microenvironment, ILCs have demonstrated roles in early infection control, adaptive immune regulation, lymphoid tissue development, and in tissue homeostasis and repair [1, 2, and 3].

Figure 1.

ILC developmental tree with known restricted progenitors and the differentiated cell populations they give rise to. ILCs are divided into group 1, group 2, and group 3 based upon common effector cytokine production.

Group 1 ILCs

Group 1 ILC are composed of cell populations functionally defined by their capacity to produce IFN-γ. In mouse, cells within this group uniformly express the surface receptors NKp46 and NK1.1, markers characteristic of NK cells [2]. However, NKp46+NK1.1+IFN-γ+ cells include a population, termed ILC1, which is developmentally and transcriptionally distinct from NK cells. ILC1, reported in the spleen, liver, intestine, and peritoneal cavity, can be discriminated from NK cells by the expression of the transcription factors (TF) T-bet and Eomes: NK cells are T-bet+Eomes+ while ILC1 are T-bet+Eomes− [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9]. It was previously thought that T-bet+Eomes− cells were immature NK cells that acquire Eomes upon maturation [10]. However, it was recently shown that T-bet+Eomes− cells do not give rise to T-bet+Eomes+ cells in steady state, suggesting that these cells are not immature but terminally differentiated [5]. In further support of this conclusion, an ILC progenitor in the bone marrow was capable of reconstituting T-bet+Eomes− ILC1 cells but not T-bet+Eomes+ NK cells. Additionally, conditional Eomes−/− mice maintained ILC1 populations and lacked mature NK cells, while Tbx21−/− mice lack ILC1 but maintained mature NK cells in the BM and gut [4 and 10].]. Also, the transcription factor PLZF is important for liver ILC1 but not liver NK cell development [11]. Finally, the transcription factor GATA-3 has been shown to be critical for ILC1 development [12, 13, and 14], yet whether it is also important for NK cell development [15] remains to be clarified.

In addition to developmental differences, some ILC1 have been shown to be tissue resident, contrasting with NK cells, which recirculate in the blood [7 and 9]. Surface markers can distinguish ILC1 and NK cells, although they may be variable depending upon the tissue examined. ILC1 have been found to be CD122+CD49a+CD49b− TRAIL+CD127+CD69+CXCR3+CXCR6+ while NK cells are CD122+CD49a−CD49b+TRAIL− CD127−CD69−CXCR3−CXCR6− (Table 1) [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9]. Importantly, although ILC1 express the IL-7Rα (CD127) they do not require IL-7 for their development and are present in Il7−/− mice. Instead, like NK cells, ILC1 critically require IL-15 signaling and are absent in Il15−/− mice [4 and 5].

Table 1.

Surface markers and transcription factor expression used to differentiate ILC precursors ILC populations.

| Phenotypic Markers | Transcription Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Progenitors | CLP | Lin−, cKitlow, CD127+, Sca1low, Flt3+, α4β7− | |

| aLP/CILP | Lin−, cKitlow, CD127+, Sca1low, Flt3−,α4β7+, CXCR6+ | Id2−, PLZF−, GATA-3− | |

| CHILP | Lin−, CD127+, Flt3−, α4β7+, CD25− | Id2+/−, PLZF+/−, GATA-3− | |

| ILCP | Lin−, cKit+, CD127+, α4β7high, CXCR6− | Id2+, PLZFhigh, GATA-3+/− | |

| Group 1 ILCs | NK cells | NK1.1+, NKp46+, CD49a−, CD49b+, TRAIL−, CD127−, CD69−, CXCR6−, CXCR3− | T-bet+, Eomes+ |

| ILC1 | NK1.1+, NKp46+, CD49a+, CD49b−, TRAIL+, CD127+/−, CD69+, CXCR6+, CXCR3+ | T-bet+, Eomes− | |

| Group 2 ILCs | ILC2 | Lin−, CD127+, CD25+, Sca1+, KLRG1+, ST2+ | GATA-3+ |

| Group 3 ILCs | NKp46+ ILC3 | NK1.1−, NKp46−, CD127+ | Rorgt+, T-bet+ |

| NKp46− ILC3 | NK1.1−, NKp46+, CD127+ | Rorgt+, T-bet+ | |

| LTi Like | NK1.1−, NKp46−, CD127+, CD4+/−, CCR6+ | Rorgt+, T-bet− | |

Although IFN-γ is the defining cytokine of both NK cells and ILC1, ILC1 are more proficient in the production of TNF-α, and in the liver preferentially produce IL-2 [5 and 7]. NK cells are well known for their capacity to kill target cells through the release of granules containing granzymes and perforin, but whether ILC1 also have cytotoxic capabilities is currently unclear. Compared to liver NK cells, liver ILC1 show differential expression of granzymes and reduced expression of perforin, yet are equally capable of cytolytic degranulation and inducing target cell death in vitro [5, 7, and IMN Robinette et al., unpublished]. Given the phenotypic and functionally similarity between NK cells and ILC1, it will be important to see if these two cell subsets play complementary or distinct roles during antiviral and antitumor immunity.

Additionally, there are still other cell types that do not exactly fit into the NK cell/ILC1 dichotomy among various tissues. For example, the small intestine contains an intraepithelial ILC1 population which is developmentally T-bet dependent but only partially IL-15 dependent [16]. The small intestine lamina propria (siLP) also contains a plastic subset of former Rorγt+ ILC3 that converts to IFN-γ-producing cells with surface markers difficult to distinguish from ILC1 (‘ex-Rorγt ILC3’) [2]. The salivary gland maintains a large population of cells which are both T-bet+Eomes+ yet poor producers of IFN-γ [17]. In the uterus, there are also NK cells that are still present in both T-bet and Eomes deficient mice [7]. Finally, human tissues contain an ILC1 population that lacks any NK cell marker [18]. More work is needed to delineate the developmental relations of these cell populations to each other and most importantly the functional role they may play during the immune response within the tissue where they reside. Based on current evidence, group 1 ILCs are a spectrum of overlapping cell subsets that produce IFN-γ rather than bimodal, well defined cell lineages.

Group 2 ILCs

ILC2 are the most homogenous ILC class, expressing largely conserved markers in all tissues, such as IL-7Ra, IL2Ra (CD25), Sca-1, KLRG1, and the IL-33 receptor ST2 (Table 1) [2]. An additional innate IL-25 responsive and type 2 cytokine producing population, called MPPType2, has also been reported. However, unlike ILC2, this IL-7Rα and ST2 negative population retains the ability to differentiate into myeloid cells [19 and 20] and is thus not strictly an ILC population. ILC2 are dependent on the TFs GATA-3, Rorα, TCF-1 and Notch for their development, which has recently been reviewed [2 and 21]. Functionally, ILC2 are well known to produce IL-5, IL-13, and Amphiregulin in a GATA-3 dependent manner [12] as well as GATA-3 independent IL-4 [12 and 22]. Recent research has focused on the how ILC2 contribute to the normal immune response through crosstalk with stromal and other immune cells, both in the innate and adaptive responses.

The first emerging mechanism that position ILC2 in the normal immune response is through positive feedback loops with other innate immune cells. Early in the immune response, various cellular sources including stroma, macrophages, NKT cells [23], and mast cells [24] produce IL-33, a danger signal produced during necrosis and downstream of danger associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [25] that has recently been reviewed [26]. IL-33 directly activates ILC2 and mast cells through its receptor ST2, enhancing their recruitment [27]. Activated mast cells further enhance ILC2 activity through the secretion of the non-caspase proteases chymase and tryptase, which increase IL-33 potency [27], and production of the strong ILC2 activator PDG2 [26]. This positive feedback cycle is fortified by ILC2 proliferative signals from basophils via IL-4 production [29 and 30]. In turn, ILC2 produced IL-5 feedback on eosinophils to promote innate effector responses, by regulating their recruitment and activity [31 and 32]. Interestingly, the helminth H. polygyrus has developed mechanisms to circumvent this pathway, as its secretory products prevent IL-33 release and subsequent ILC2 activation and eosinophil recruitment [33]. Thus, crosstalk between other innate immune cells and ILC2 promote an early feed forward type 2 response.

A second theme investigated recently has been the role of ILC2 in the priming and development of an appropriate TH2 response. Mechanisms of ILC2-TH2 crosstalk are both indirect and direct. ILC2 indirectly promote TH2 differentiation through early type 2 cytokine production. For example, in a papain model of allergic lung inflammation, ILC2-produced IL-13 induces DC migration to the mediastinal lymph node, which was a key event responsible for TH2 priming [34]. Similarly, ILC2 harvested from an atopic dermatitis model and adoptively transferred intradermally into wildtype mice led to enhanced TH2 responses in the draining lymph node [29]. ILC2 also directly lead to TH2 responses via expression of MHC II, which facilitates antigen presentation to T cells at a similar capacity to B cell [35 and 36]. Functionally, this interaction is relevant, as mice depleted of ILC2 or lacking ILC2 expression of MHC II had impaired ability to mount appropriate T cell responses during N. brasiliensis infection [36]. ILC2 can also directly activate CD4+ T cells via IL-4 production and OX40L costimulation [37]. Thus, ILC2 priming of the adaptive immune responses is an important component of their physiologic function and a mechanism of deregulation during pathology.

Group 3 ILCs

This group of ILCs is highly complex and includes many reported subsets in adult mice, as well as additional fetal and neonatal LTi subsets that have been long recognized as a key factor for lymphoid organogenesis. ILC3 are grouped together based on shared expression of the transcription factor Rorγt, but vary in their expression of T-bet, cell surface markers, and cytokine production profiles. In the adult, these subsets include 4 populations found at greatest frequency in the siLP (Table 1): CD4+ and a CD4− subsets of CCR6+ Nkp46− Rorγt+ LTi-like cells [38]; NKp46− Rorγt+ T-bet+ ILC3 progenitors [38]; NKp46+ Rorγt+ T-bet+ Notch-dependent ILC3 [39, 40, 41, and 42]. One additional subset of IL-17 and IFN-γ producing Rorγt+ Nkp46− ILC3 is present in the large intestine [43]. Similar to group 1 ILCs, group 3 ILCs are particularly complicated due to evidence of diverging progenitors for different subsets that share many of the same functions and cell surface markers. A current, simplified model of differentiation posits that there is progressive differentiation from NKp46− ILC3, to NKp46+ ILC3, and finally to NKp46+ NK1.1+ ex-Rorγt ILC3 [2]. In contrast, CCR6+ NKp46− LTi-like do not give rise to NKp46+ ILC3 after transfer [40]. Recent gene expression profiling in our lab demonstrate that CD4+ and CD4− NKp46− LTi-like subsets have minimal transcriptional differences and are unlikely to be functionally distinct (IMN Robinette et al., unpublished). It remains possible that the diversity of these subsets depends on the microenvironment or their origin from either fetal or adult progenitors.

As all Rorγt+ ILC3 can produce IL-22, many recent studies have described new ways that this cytokine mediates barrier integrity during homeostatic conditions and mucosal remodeling during injury and infection. IL-22 is a member of the IL-10 family of cytokines, which acts through an IL-22 dimeric receptor only expressed by non-immune stromal cells. IL-22 is produced by ILC3 in response to IL-23 stimulation by CX3CR1+ inflammatory monocytes and CD11b+ DC [44 and 45]. This ILC3-DC priming has recently been shown to be dependent on CXCR6-CXCL16 [45] and defects in CXCR6 lead to loss of protection from Citrobacter rodentium, an attaching and effacing pathogen well known to be controlled by IL-22. Within the GI tract, ILC3 locally regulate commensals and pathogens by inducing intestinal epithelial fucosylation via IL-22 in response to microbial signals [46 and 47]. Systemic IL-22 protects the gastrointestinal epithelium from potentially pathogenic symbionts, or pathobionts, after prior injury by inducing complement factor C3 production from the liver [48]. Additionally, IL-22 in concert with IL-18 are critical to the prevention and resolution of intestinal norovirus infection, demonstrating novel antiviral functions of this cytokine [49]. Although IL-22 signaling appears to be mostly beneficial to the host, it can become pathogenic in certain circumstances, such as the anti-CD40 model of colitis in RAG deficient animals, mediated in part by IL-22-induced secretion of neutrophil chemoattractants by epithelial cells and dysregulated recruitment of neutrophils [50]. Another potential pathological effect of ILC3-mediated IL-22 production is tumorigenesis, which occurs downstream of sustained STAT3 activation in epithelial cells in mice. Indeed, cells with ILC3 consistent phenotypes (CD3− IL22+) can be found in human adenocarcinomas [51]. Notably, this defect may be due in part to IL-17, as loss of IL-17 in RAG deficient mice diminishes adenoma development [52]. Thus, ILC3 produced IL-22 has both host protective and pathological roles within the gastrointestinal tract.

Beyond IL-22, ILC3 also respond to the microbiome and host micronutrient status to modulate the immune response. In response to commensal flora driven IL-1β, ILC3 produce GM-CSF, which expands colonic DCs and macrophages that support T-reg development. Thus, ILC3 may also contribute to oral tolerance [53]. Furthermore, recent functional analyses of ILC3 have demonstrated that their expression of MHC II facilitates antigen presentation, which combined with the absence of costimulatory molecules, enables ILC3 to induce T cell tolerance [54]. Interestingly, recent evidence demonstrates that the immune response can also be modified through micronutrients availability. In this vein, vitamin A deficiency leads to a blunted ILC3 but enhanced ILC2 response [55], while vitamin D deficiency enhances the ILC3 response [56]. As the availability of some micronutrients is directly regulated by the microbiome, this may represent a conserved pathway important for immunoregulation.

ILC Development from a Common Progenitor

Within the bone marrow, the common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) gives rise to all ILC lineages, as well as B and T cells [2]. The earliest progenitor with restricted lineage potential all ILCs has recently been identified as the CXCR6+ αLP (α4β7 expressing CLP; also known as the common innate lymphoid progenitor-CILP) (Figure 1 and Table 1) [57]. The αLP shows multi-lineage differentiation, including NK, ILC1, ILC2, and all ILC3 both in vitro and upon transplantation in vivo. This progenitor is dependent on the basic leucine zipper TF NFIL3, consistent with other reports describing a lack of all ILCs in Nfil3−/− mice [58 and 59]. Of note, the NFIL3 requirement for Group 1 ILC development can be bypassed following some infections [60] and/or environmental factors [7 and 17]. Moreover, Group 1 ILC subsets in the salivary gland, uterus, and possibly liver appear to develop independently of NFIL3. Therefore the αLP may not be completely dependent on NFIL3 or some ILC may develop from a non-αLP progenitor.

After the αLP, lineage divergence of ILC populations has recently been demonstrated by two reports [4 and 11]. One study used reporter mice for the TF Id2 (a transcriptional repressor of E2-family TFs) to identify a Id2+Lin−IL-7Ra+α4β7+CD25−PLZF+/− Common Helper-Like Innate Lymphoid Progenitor (CHILP). Upon transfer, the CHILP gave rise to Eomes− ILC1, ILC2, NKp46+ ILC3 and NKp46− ILC3 including the CD4+ LTi-like subset, but not Eomes+ NK cells. Although the CHILP was identified by Id2 expression, the importance of this TF may not be limited to this progenitor as Id2−/− mice lack NK cells and some ILC1, ILC2, and ILC3 [61 and 62]. Moreover, Id2 identifies an early NK cell restricted progenitor, the pre-pro NK [63].

In another study, lineage tracing with combined PLZFGFPCre × Rosa26-YFP reporter mice revealed that most ILCs were GFP− (thus not expressing PLZF) [11]. However, these cells were YFP+ (expressed PLZF at some point) and found to derive from a PLZFhighLin−IL-7Ra+cKit+ α4β7high CXCR6− progenitor, called the innate lymphoid cell progenitor (ILCP). Transfer of these ILCPs with competitor CLPs demonstrated that ILCP cells gave rise to greater frequencies of ILCs, corresponding to a progenitor skewed toward ILC development. ILCPs efficiently generated ILC1, ILC2, and some ILC3, but were poor at generating NK cells or LTi-like subsets. One caveat is that this study identified ILC1s by the lack of expression of CD49b and not Eomes expression, a more definitive maker. Given the more restricted differentiation of the ILCP, the current model of ILC development would place it downstream of the CHILP. PLZF deficiency causes some defects in ILC1 and ILC2 development, suggesting that it is not essential for all ILC development. Interestingly, GATA-3 is first expressed in the ILCP and some models of GATA-3 deficiency lead to selective reduction of ILC1, ILC2, and some ILC3, but not NK cells or LTi-like cells, in agreement with the progenitor capacity of the ILCP [11, 12, 13,14, and 15].

Concluding remarks

With the increasing complexity of ILC subsets, it becomes important to clearly define the developmental origin and the functional impact of each of these subsets. While there may be redundancy among subsets, it is clear that each ILC group and some subsets within each group have specialized functions. Many studies have shown the beneficial roles of ILC in host defense against pathogens. Current studies are shifting the focus on the interaction of ILC with the commensal flora, the relevance of this interaction in tolerance and, when interaction is deregulated, in the immune-mediated disease pathogenesis, including IBD, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and asthma. While ILCs were originally studied in gut, lung and lymphoid organs, more studies are investigating their roles in other organs and tissues, such as skin, liver and exocrine glands. It will be interesting to see how the developmental stages of tissues analyzed promotes the plasticity and activation of a given ILC population. Better understanding of ILC cell biology will likely reveal new mechanisms of immunity and immunopathology and avenues of intervention in many human diseases.

Highlights.

Group 1 ILC comprise diverse subsets producing IFN-γ

Group 2 ILC crosstalk with TH2 for immune responses

Group 3 ILC modulate immune response to the microbiome and micronutrient status

Bone marrow progenitors give rise to multiple ILC lineages

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Brian Kim, Tyler Ull, and Nick Huntington for valuable discussion and editing of the manuscript. The Colonna laboratory is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (1U01AI095542, R01DE021255, and R21CA16719). V.S. Cortez was supported by the Infectious Disease Training Grant T32 AI 7172-34. M.L. Robinette was supported by the MSTP Training Grant T32 GM07200.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.McKenzie AN, Spits H, Eberl G. Innate lymphoid cells in inflammation and immunity. Immunity. 2014;41:366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diefenbach A, Colonna M, Koyasu S. Development, Differentiation, and Diversity of Innate Lymphoid Cells. Immunity. 2014;41:354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cella M, Miller H, Song C. Beyond NK cells: the expanding universe of innate lymphoid cells. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:00282. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4••.Klose CS, Flach M, Möhle L, Rogell L, Hoyler T, Ebert K, Fabiunke C, Pfeifer D, Sexl V, Fonseca-Pereira D, et al. Differentiation of type 1 ILCs from a common progenitor to all helper-like innate lymphoid cell lineages. Cell. 2014;157:340–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.030. This study identifies an ILC progenitor, the CHILP, lineage restricted to ILC1, ILC2, and ILC3 but not NK cells.

- 5•.Daussy C, Faure F, Mayol K, Viel S, Gasteiger G, Charrier E, Bienvenu J, Henry T, Debien E, Hasan UA, et al. T-bet and Eomes instruct the development of two distinct natural killer cell lineages in the liver and in the bone marrow. J Ex Med. 2014;211(3):563–577. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131560. This work shows that T-bet+Eomes− cells do not give rise to T-bet+Eomes+ NK cells, demonstrating they are not immature NK cells but a distinct population, the ILC1.

- 6.Siellet C, Huntington D, Gangatirkar P, Axelsson E, Minnich M, Brady HJM, Busslinger M, Smyth MJ, Belz GT, Carotta S. Differential requirement for NFIL3 during NK cell development. J Immunol. 2014;192:2667–276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sojka DK, Plougastel-Douglas B, Yang L, Pak-Wittel MA, Artyomov MN, Ivanova Y, Zhong C, Chase JM, Rothman PB, Yu J, Riley J, et al. Tissue-resident natural killer (NK) cells are cell lineages distinct from thymic and conventional splenic NK cells. eLife. 2014:e01659. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crotta S, Gkioka A, Male V, Duarte JH, Davidson S, Nisoli I, Brady HJM, Wack A. The transcription factor E4BP4 is not required for extramedullary pathways of NK cell development. J Immunol. 2014;192:2677–288. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzaga R, Matzinger P, Perez-Diez A. Resident Peritoneal NK cells. J Immunol. 2011;187(12):6235–6242. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon SM, Chaix J, Rupp LJ, Wu J, Madera S, Sun JC, Lindsten T, Reiner SL. The transcription factors T-bet and Eomes control key checkpoints of natural killer cell maturation. Immunity. 2012;36:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11••.Constantinides MG, McDonald BD, Verhoef PA, Bendelac A. A committed precursor to innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2014;508:397–401. doi: 10.1038/nature13047. The first study to identify a progenitor restricted to multiple ILC lineages.

- 12.Yagi R, Zhong C, Northrup DL, Yu FF, Bouladoux N, Spencer S, Hu G, Barron L, Sharma S, Nakayama T, Belkaid Y, Zhao K, Zhu J. The transcription factor GATA3 is critical for the development of all IL-7Rα-expressing innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2014;40:378–388. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoyler T, Klose CS, Souabni A, Turqueti-Neves A, Pfeifer D, Rawlins EL, Voehringer D, Busslinger M, Diefenbach A. The Transcription factor GATA-3 controls cell fate and maintenance of type 2 innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2012;37:634–648. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vosshenrich CAJ, Carcia-Ojeda ME, Samson-Villeger SI, Pasqualetto V, Enault L, Le Goff OR, Corcuff E, Guy-Grand D, Rocha B, Cumano A, Rogge L, Ezine S, Di Santo JP. A thymic pathway of mouse natural killer cell development characterized by expression of GATA-3 and CD127. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(11):1217–1224. doi: 10.1038/ni1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samson SL, Richard o, Tavian M, Ranson T, Vosshenrich CA, Colucci F, Buer J, Grosveld F, Godin I, Di Santo JP. GATA-3 promotes maturation, IFN-gamma production, and liver-specific homing of NK cells. Immunity. 2003;19(5):701–711. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuchs A, Vermi W, Lee JS, Lonardi S, Gilfillan S, Newberry RD, Cella M, Colonna M. Intraepithelial Type 1 Innate Lymphoid Cells Are a Unique Subset of IL-12- and IL-15-Responsive IFN-g-Producing Cells. Immunity. 2013;38:769–781. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cortez VS, Fuchs A, Cella M, Gilfillan S, Colonna M. Cutting edge: Salivary gland NK cells develop independently of Nfil3 in steady-state. J Immunol. 2014;192:4487–4491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernink JH, Peters CP, Munneke M, Velde AA, Meijer SL, Weijer K, Hreggvidsdottir HS, Heinsbroek SE, Legrand N, Buskens JCJ, et al. Human type 1 innate lymphoid cells accumulate in inflamed mucosal tissues. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:221–229. doi: 10.1038/ni.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saenz SA, Siracusa MC, Perrigoue JG, Spencer SP, Urban JF, Tocker JE, Budelsky AL, Kleinschek MA, Kastelein RA, Kambayashi T, Bhandoola A, Artis D. IL25 elicits a multipotent progenitor cell population that promotes T(H)2 cytokine responses. Nature. 2010;464:1362–1366. doi: 10.1038/nature08901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saenz SA, Siracusa MC, Monticelli LA, Ziegler CGK, Kim BS, Brestoff JR, Peterson LW, Wherry EJ, Goldrath AW, Bhandoola A, Artis D. IL-25 simultaneously elicits distinct populations of innate lymphoid cells and multipotent progenitor type 2 (MPPtype2) cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1823–1837. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Q, Monticelli LA, Saenz SA, Chi AWS, Sonnenberg GF, Tang J, Obaldia ME, Bailis W, Bryson JL, Toscano K, Huang J, Haczku A, Pear WS, Artis D, Bhandoola A. T cell factor 1 is required for group 2 innate lymphoid cell generation. Immunity. 2013;38:694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drake LY, Iijima K, Kita H. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4+ T cells cooperate to mediate type 2 immune responses in mice. Allergy. 2014;69:1300–1307. doi: 10.1111/all.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorski SA, Hahn YS, Braciale TJ. Group 2 Innate lymphoid cell production of Il-5 is regulated by NKT cells during influenza virus infection. PLOS Pathogens. 2014;9:e1003615. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu CL, Neilsen CV, Bryce PJ. IL-33 is produced by mast cells and regulates IgE-dependent inflammation. Plos One. 2010:0011944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel N, Wu W, Mishra PK, Chen F, Millman A, Csóka B, Koscsó B, Eltzschig HK, Haskó G, Gause WC. A2B adenosine receptor induces protective antihelminth type 2 immune response. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;14:339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cayrol C, Girard JP. IL-33: an alarmin cytokine with crucial roles in innate immunity, inflammation and allergy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014;31:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.LeFrançais E, Duval A, Mirey E, Roga S, Espinosa E, Cayrol C, Girard JP. Central domain of IL-33 is cleaved by mast cell proteases for potent activation of group-2 innate lymphoid cells. PNAS. 2014;111:15502–15507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410700111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue L, Salimi M, Panse I, Mjösberg JM, McKenzie ANJ, Spits H, Klenerman P, Ogg G. Prostaglandin D2 activates group 2 innate lymphoid cells through chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecules expressed in TH2 cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014;133:118–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim BS, Wang K, Siracusa MC, Saenz SA, Brestoff JR, Monticelli LA, Noti M, Wojno EDT, Fung TC, Kubo M, Artis D. Basophils promote innate lymphoid cell response in inflamed skin. J Immunol. 2014;193:3717–3725. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motomura Y, Morita H, Moro K, Nakae S, Artis D, Endo TA, Kuroki Y, Ohara O, Koyasu S, Kuba M. Basophil-derived interleukin-4 controls the function of natural helper cells, a member of ILC2s, in lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:758–771. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roediger B, Kyle R, Yip KH, Sumaria N, Guy TV, Kim BS, Mitchell AJ, Tay SS, Jain R, Forbes-Blom E, Chen X, Tong PL, et al. Cutaneous immunosurveillance and regulation of inflammation by group 2 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:564–573. doi: 10.1038/ni.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nussbaum JC, Van Dyken SJ, von Moltke J, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, Molofsky AB, Thornton EE, Krummel MF, Chawla A, Liang HE, Locksley RM. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 2013;502:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McSorley HJ, Blair NF, Smith KA, McKenzie AN, Maizels RM. Blockade of IL-33 release and suppression of type 2 innate lymphoid cell response by helminth secreted products in airway allergy. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:1068–1078. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halim TY, Steer CA, Mathä L, Gold MJ, Martinez-Gonzalez I, McNagny KM, McKenzie AN, Takei F. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are critical for the initiation of adaptive T helper 2 cell-mediated allergic lung inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:425–435. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirchandani AS, Besnard AG, Yip E, Scott C, Bain CC, Cerovic RJ, Salmond RJ, Liew FY. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells drive CD4+ Th2 cell responses. J Immunol. 2014;192:2442–2448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliphant CJ, Hwang YY, Walker JA, Wong SH, Brewer JM, Englezakis A, Barlow JL, Hams E, Scanion ST, Ogg GS, Fallon PG, McKenzie AN. MHCII-mediated dialog between group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4(+) T cells potentiates type 2 immunity and promotes parasitic helminth expulsion. Immunity. 2014;41:283–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Drake LY, Iijima K, Kita H. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells and CD4+ T cells cooperate to mediate type 2 immune responses in mice. Allergy. 2014;69:1300–1307. doi: 10.1111/all.12446. Collectively, these studies show that ILC2 are directly able to stimulate TH2 responses in ways other than innate cytokine production.

- 38.Sawa S, Cherrier M, Lochner M, Satoh-Takayama N, Fehling HJ, Langa F, Di Santo JP, Eberl G. Lineage relationship analysis of RORgt+ innate lymphoid cells. Science. 2010;29:665–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1194597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JS, Cella M, McDonald KG, Garlanda C, Kennedy GD, Nukaya M, Mantovani A, Kopan R, Bradfield CA, Newberry RD, Colonna M. AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:144–151. doi: 10.1038/ni.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klose CS, Kiss EA, Schwierzeck V, Ebert K, Hoyler T, d’Hargues Y, Göppert N, Croxford AL, Waisman A, Tanriver Y, Diefenbach A. A T-bet gradient controls the fate and function of CCR6−Rorgt+ innate lymphoid cells. Nature. 2013;494:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature11813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sciumé G, Hirahara K, Takahashi H, Laurence A, Villarino AV, Singleton KL, Spencer SP, Wilhelm C, Poholek AC, Vahedi G, et al. Distinct requirements for T-bet in gut innate lymphoid cells. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:2331–2338. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rankin LC, Groom JR, Chopin M, Herold MJ, Walker JA, Mielke LA, McKenzie AN, Carotta S, Nutt SL, Belz GT. The transcription factor T-bet is essential for the development of NKp46+ innate lymphocytes via the Notch pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:389–395. doi: 10.1038/ni.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buonocore S, Ahern PP, Uhlig HH, Ivanov II, Littman DR, Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Innate lymphoid cells drive interleukin-23-dependent innate intestinal pathology. Nature. 2010;464:1371–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature08949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Longman RS, Diehl GE, Victorio DA, Huh JR, Galan C, Miraldi ER, Swaminath A, Bonneau R, Scherl EJ, Littman DR. CX3CR1+ mononuclear phagocytes support colitis-associated innate lymphoid cell production of IL-22. J Exp Med. 2014;211:1571–1583. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Satoh-Takayama N, Serafini N, Verrier T, Rekiki A, Renauld JC, Frankel G, Di Santo JP. The chemokine receptor CXCR6 controls the functional topography of IL-22 producing intestinal innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2014;41:776–788. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goto Y, Obata T, Kunisawa J, Sato S, Ivanov II, Lamichhane A, Takeyama N, Kamioka M, Sakamoto M, Matsuki T, et al. Innate lymphoid cells regulate intestinal epithelial cell glycoslyaltion. Science. 2014;345:6202. doi: 10.1126/science.1254009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pickard JM, Maurice CF, Kinnebrew MA, Abt MC, Schenten D, Golovkina TV, Bogatyrev SR, Ismagilov RF, Pamer EG, Turnbaugh PJ, Chervonsky AV. Rapid fucosylation of intestinal epithelium sustains host-commensal symbiosis in sickness. Nature. 2014;514:638–641. doi: 10.1038/nature13823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hasegawa M, Yada S, Liu MZ, Kamada N, Muñoz-Planill R, Do N, Núñez G, Inohara N. Interleukin-22 regulates the complement system to promote resistance against pathobionts after pathogen-induced intestinal damage. Immunity. 2014;41:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang B, Chassaing B, Shi Z, Uchiyama R, Zhang Z, Denning TL, Crawford SE, Pruijssers AJ, Iskarpatyoti JA, Estes MK, Dermody TS, Ouyang W, William IR, Vijay-Kumar M, Gewirtz AT. Prevention and cure of rotavirus infection via TLR5/NLRC4-mediated production of IL-22 and IL-18. Science. 2014;346(6211):861–865. doi: 10.1126/science.1256999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eken A, Singh AK, Treuting PM, Oukka M. IL-23R+ innate lymphoid cells induce colitis via interleukin-22-dependent mechanism. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:143–154. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirchberger S, Royston DJ, Boulard O, Thornton E, Franchini F, Szabady RL, Harrison O, Powrie F. Innate lymphoid cells sustain colon cancer through production of interleukin-22 in a mouse model. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:917–931. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chan IH, Jain R, Tessmer MS, Gorman D, Mangadu R, Sathe M, Vives F, Moon C, Penaflor E, Turner S, et al. Interleukin-23 is sufficient to induce rapid de novo gut tumorigenesis, independent of carcinogens, through activation of innate lymphoid cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:842–856. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mortha A, Chudnovskiy A, Hashimoto D, Bogunovic M, Spencer SP, Belkaid Y, Merad M. Microbiota-dependent crosstalk between macrophages and ILC3 promotes intestinal homeostasis. Science. 2014;343(6178):1249288. doi: 10.1126/science.1249288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54•.Hepworth MR, Monticelli LA, Fung TC, Ziegler CG, Grunberg S, Sinha R, Mantegazza AR, Ma HL, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, Wherry EJ, et al. Innate lymphoid cells regulate CD4+ T-cell responses to intestinal commensal bacteria. Nature. 2013;498:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature12240. 42, 43, 52, and 53 show the larger context of ILC produced IL-22 in regards to cross talk with other immune cells, the intestinal epithelium, and the microbiota.

- 55.Spencer SP, Wilhelm C, Hall JA, Bouladoux N, Boyd A, Nutman TB, Urban JF, Wang J, Ramalingam TR, Bhandoola A, Wynn TA, Belkaid Y. Adaptation of innate lymphoid cells to a micronutrient deficiency promotes type 2 barrier immunity. Science. 2014;343:432–437. doi: 10.1126/science.1247606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen J, Waddell A, Lin YD, Cantorna MT. Dysbiosis caused by vitamin D receptor deficiency confers colonization resistance to Citrobacter rodentium through modulation of innate lymphoid cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.94. mi.2014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57••.Yu X, Wang Y, Deng M, Li Y, Ruhn KA, Zhang CC, Hooper LV. The basic leucine zipper transcription factor NFIL3 directs the development of a common innate lymphoid cell progenitor. eLife. 2014;10:e04406. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04406. This study identifies a progenitor, the αLP/CILP, capable of giving rise to all known ILC populations.

- 58.Seillet C, Rankin LC, Groom JR, Mielke LA, Tellier J, Chopin M, Huntington ND, Belz GT, Carotta S. Nfil3 is required for the development of all innate lymphoid cell subsets. J Exp Med. 2014;9:1733–1740. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Geiger TL, Abt MC, Gasteiger G, Firth MA, O’Conner MH, Geary CD, O’Sullivan TE, van der Brink MR, Pamer EG, Hanash AM, Sun JC. Nfil3 is crucial for development of innate lymphoid cells and host protection against intestinal pathogens. J Exp Med. 2014;9:1723–1731. doi: 10.1084/jem.20140212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60•.Firth MA, Madera S, Beaulieu AM, Gasteiger G, Castillo EF, Schluns KS, Kubo M, Rothman PB, Vivier E, Sun JC. Nfil3-independent lineage maintenance and antiviral response of natural killer cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2981–2990. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130417. These studies demonstrate that populations of group 1, 2, and 3 ILCs are critically dependent upon the transcription factor NFIL3.

- 61.Boos MD, Yokota Y, Eberl G, Kee BL. Mature natural killer cell and lymphoid tissue-inducing cell development requires Id2-mediated protein activity. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1119–1130. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yokota Y, Mansouri A, Mori S, Sugawara S, Adachi S, Nishikawa SI, Gruss P. Development of peripheral lymphoid organs and natural killer cells depends on the helix-loop-helix inhibitor Id2. Nature. 1999;397:702–706. doi: 10.1038/17812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carotta S, Pang SH, Nutt SL, Belz GT. Identification of the earliest NK-cell precursor in the mouse BM. Blood. 2011;117(20):5449–5452. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-318956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]