Summary

Phosphopantetheinyl transferases (PPTase) Sfp and AcpS catalyze a highly efficient reaction that conjugates chemical probes of diverse structures to proteins. PPTases have been widely used for site-specific protein labeling and live cell imaging of the target proteins. Here we describe the use of PPTase catalyzed protein labeling in protein engineering by facilitating high throughput phage selection.

1. Introduction

Protein labeling with small molecules expands the diversity of the functional groups anchored on the peptide chain. The labelled proteins can function as reporters to register their locations in the cell, to reveal their partnerships with other cellular proteins, and to record their life cycle including expression, posttranslational modification, and degradation in various cellular processes. A good protein labeling method prefers site specific attachment of the small molecule labels to the target proteins so that the position and stoichiometry of the label can be precisely defined. A good labeling method should also be versatile so that the labels of diverse chemical structures and functionalities can be attached to the target proteins based on their tasks in studying cell biology. A good labeling method should also be fast and of high efficiency so that the labeled proteins can be tracked in real time and in the live cell.

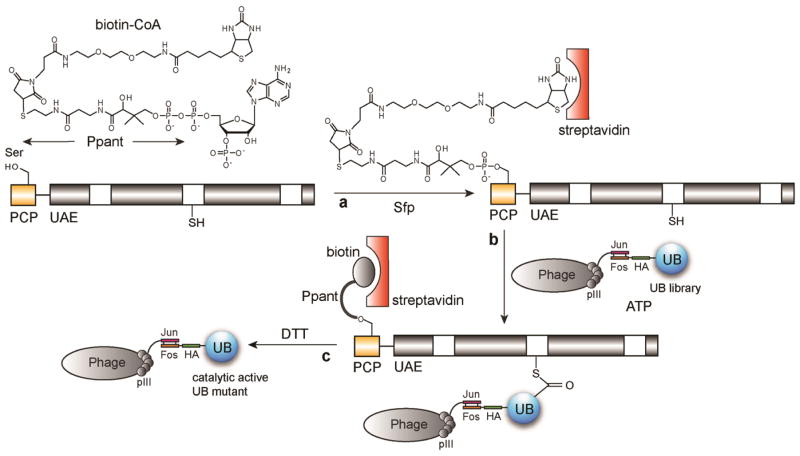

The protein labeling reaction catalyzed by Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase can fulfill all these criterions (1). The native activity of Sfp is to transfer the phosphopantetheinyl (Ppant) group of coenzyme A (CoA) to a specific serine residue of the peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) domains embedded in the nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS). The Ppant modification of PCP activates NRPS for natural product biosynthesis (2). Sfp was found to be very promiscuous with the chemical functionalities attached to the terminal thiol of CoA; besides the Ppant arm itself, the enzyme can recognize small molecule - CoA conjugates as substrates and attach small molecule labels to PCP through the Ppant linker (Fig. 1) (3, 4). Sfp-catalyzed protein labeling is also fast, nearly of quantitative yield, and can be performed on the surface of live cells. All these features make Sfp a very useful tool for site-specific protein labeling.

Fig. 1.

Sfp catalyzed labeling of PCP-UAE fusion protein with the biotin-CoA conjugate and phage selection with the UAE enzyme immobilized on the streptavidin plate. (a) Biotin-Ppant group is transferred from biotin-CoA by Sfp to a Ser residue in the PCP domain fused to the N-terminus of UAE. Biotin-labelled UAE is then immobilized on the streptavidin plate. (b) Phage library displaying UB variants reacts with UAE on the plate to form UB~UAE conjugates. (c) After washing the plate, phage displaying catalytic active UB variants are eluted by DTT that cleaves the thioester bond.

We previously demonstrated that Sfp can be used to conjugate diverse chemical labels to the target proteins (4, 5), to image cell surface proteins by fluorescent resonance transfer (FRET) (6), and to profile natural product biosynthetic clusters in a single bacteria or in the metagenome (7). We have also developed small peptide tags named ybbR and S6 that are 11-residue long for protein labeling by Sfp (8, 9). We later identified an A1 peptide tag that can be specifically labeled with AcpS, a phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) from E. coli (8). The A1-AcpS pair and the S6-Sfp pair are orthogonal to each other so that distinctive cell surface receptors can be labeled with different fluorophores to track their movements in the same cell (8). Other researchers have used Sfp and AcpS to image polarized secretion of proteins on the yeast cell wall (10), to immobilize proteins on the hydrogel or glass slides or on nanoparticles (11–13), to attach fluorescent labels to neurotoxins, chemokins, and Hedgehog receptors to reveal their trafficking in the cell (14–16). We have compiled a detailed protocol for Sfp catalyzed protein labeling for cell imaging studies and it has been reported elsewhere (1). We recently developed efficient methods for protein engineering by phage display and yeast cell surface display using biotin-labeled proteins generated by Sfp (17–19). In this chapter, we present the methods of using Sfp to label proteins to facilitate phage selection.

Our research demonstrated that Sfp catalyzed protein labeling is especially suitable for conjugating affinity probes to proteins to facilitate protein engineering by phage and yeast cell selection. This is because Sfp-catalyzed protein labeling is very fast and is almost of quantitative yield. Target proteins can be freshly labeled with biotin or other chemical probes and used directly for phage or yeast selection without an additional purification step. This significantly increases the selection efficiency and the likelihood of success of the protein engineering experiment. We previously showed that we can use Sfp to label Nrf2 with biotin to select for Keap1 variants that have high affinity for cancer related Nrf2 mutants by yeast cell sorting (20). Here we provide an example to use Sfp labeled protein for phage selection. We use Sfp to site-specifically label ubiquitin (UB) activating enzyme (UAE) with biotin-Ppant to select for phages displaying UB variants that are reactive with UAE (Fig. 1) (17, 18).

UAE is the first enzyme in the UB transfer cascade for protein ubiquitination (21, 22). It activates the C-terminal carboxylate of UB so that UB can be covalently conjugated to the amino group of the Lys side chain on the cellular proteins. In the activation reaction, UAE binds to both UB and ATP to catalyze the condensation reaction between the C-terminal carboxylate of UB and ATP to form UB-AMP conjugate. A catalytic Cys residue of UAE then reacts with UB-AMP to form UB~UAE thioester in which the C-terminal carboxylate of UB is covalently bound to the catalytic Cys of UAE (Fig. 1). UAE bound UB can then be further transferred to E2 and E3 in the enzymatic cascade on its way to be attached to substrate proteins. In this protocol, we use phage display to profile the interaction between UB C-terminal sequences with UAE. We construct a fusion protein with the PCP domain fused to the N-terminus of UAE. We then use Sfp and biotin-CoA conjugate to label the PCP-UAE fusion with the biotin-Ppant group and immobilize biotin labeled UAE on the streptavidin plate (Fig. 1). We add the phage library to PCP-UAE coated plate in the presence of ATP to initiate the activation reaction. UB variants that can be recognized by UAE for the activation reaction would form UB~UAE thioester conjugate. This covalent interaction retains the catalytically active phage particles on the plate and they can then be eluted by dithiothreitol (Fig. 1). Following such a procedure, we identified UB variants with alternative C-terminal sequences that are reactive with UAE (17).

Based on this protocol, readers can develop their own methods to label the target proteins with various chemical probes by Sfp for phage selection.

2. Materials

The materials needed for the synthesis and purification of biotin-CoA conjugate, expression of Sfp, labeling target proteins with Sfp, and phage selection are covered below. All aqueous solutions were prepared with deionized water from a commercial water purifier with a conductivity of 18 MΩ or higher.

2.1. Materials for the synthesis of biotin-CoA conjugate

Biotin maleimide powder. Store at 4°C until use.

Coenzyme A powder in the form of trilithium salt. Store at −20 °C until use.

Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), analytical grade.

Conjugation reaction buffer (50 mM MES acetate, pH 6.0). Dissolve 9.76 g MES acetate in 1 L water and adjust pH to 6.0.

2.2. Materials for the purification of biotin-CoA conjugate by HPLC

Solution A, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water.

Solution B, 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile (ACN). HPLC grade ACN is used.

High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) machine equipped with a preparation scale C18 reverse phase column.

2.3. Materials for the expression and purification of the Sfp enzyme

-

1

The plasmid for Sfp expression. The Sfp gene was cloned into the pET29 expression plasmid with a C-terminal 6×His tag. The plasmid also has a kanamycin resistant marker.

-

2

Luria-Bertani (LB) media. Dissolve 25 g LB powder in 1 L water. Autoclave the media with a liquid cycle for 20 minutes.

-

3

LB-Agar plate supplemented with kanamycin. Mix 25 g LB and 15 g agar in 1 L water. Autoclave the media with a liquid cycle for 20 minutes. After the solution is cooled down to around 50°C, add kanamycin to a final concentration of 50 μg/mL. Mix melted LB-agar well and pour approximately 40 mL media to each plate. Close the lid and leave the plates at room temperature to cool off. Inverse the plates and store the plates at 4°C after the agar solidifies.

-

4

Kanamycin solution (50 mg/mL). Dissolve 50 mg of kanamycin in 1 mL water. Filter sterilize the solution and store the solution in a −20 °C freezer.

-

5

Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (0.1 M). Dissolve 1.2g IPTG in deionized water to a final volume of 50ml. Filter sterilize and store in aliquots at −20°C.

-

5

Lysis buffer for Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, and 5 mM imidazole). Dissolve 6.9 g NaH2PO4, 17.6 g NaCl and 0.34 g imidazole in 1 L water. Adjust pH to 8.0.

-

6

Wash buffer for Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, and 20 mM imidazole). Dissolve 6.9 g NaH2PO4, 17.6 g NaCl and 1.36 g imidazole in 1 L water. Adjust pH to 8.0.

-

7

Elution buffer for Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, and 200 mM imidazole). Dissolve 6.9 g NaH2PO4, 17.6 g NaCl and 13.6 g imidazole in 1 L water. Adjust pH to 8.0.

-

8

Dialysis buffer for Sfp (50 mM TrisHCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5% (v/v) glycerol). Dissolve 6.1 g TrisOH, 2.1 g MgCl2, 0.77 g DTT and 50 mL glycerol in 1 L water. Adjust pH to 8.0.

-

9

Sfp labeling reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5). Dissolve 11.9 g HEPES and 0.95 g MgCl2 in 1 L water. Adjust pH to 7.5.

2.4. Materials for phage preparation and selection

-

1

2YT medium. Dissolve 31 g of 2YT powder in 1 L water. Autoclave the media with a liquid cycle for 20 minutes.

-

2

Ampicillin (100 mg/mL). Dissolve 1 g ampicillin power in 10 mL water. Filter sterilize the solution and store the aliquots in −20°C freezer.

-

3

PEG solution. Dissolve 100 g PEG 8000 and 75 g NaCl in 500 mL H2O. Filter sterilize the solution and store it at room temperature.

-

4

TBS buffer (10 mM TrisHCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5). Dissolve 8.8 g NaCl in 1 L water with the addition of 10 mL 1M TrisHCl, pH 7.5.

-

5

TBS-T buffer (10 mM TrisHCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, 0.05% (v/v)Tween 20, and 0.05% (v/v) Triton X-100). Dissolve 0.5 mL Tween 20 and 0.5 mL Triton X-100 in 1 L TBS.

-

6

UAE reaction buffer (1.5% BSA, 1 mM ATP, and 50 mM MgCl2 in TBS). Dissolve 0.15 g bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5.5 mg ATP, and 47.6 mg MgCl2 in 10 mL TBS.

-

8

Phage elution buffer (20 mM DTT in TBS). Dissolve 0.31 g DTT in TBS. filter sterilize the solution and store the solution at 4°C.

3. Methods

3.1. Synthesizing Biotin-CoA conjugate

Dissolve biotin maleimide (10 mg, 0.019 mmol) in 300 μL DMSO.

Dissolve Coenzyme A trilithium salt (18.2 mg, 0.023 mmol) in 2 ml conjugation reaction buffer.

Mix the biotin maleimide and coenzyme A solution and stir the solution at room temperature for overnight.

Purify the biotin-CoA product by preparative HPLC on a reversed-phase C18 column. Wash the column with a gradient 0–60% ACN (solution B) in 0.1% TFA/water (solution A) over 35 minutes.

Lyophilyze the fraction with the biotin-CoA product.

Use Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) operating in the positive ion mode to confirm the identity of biotin-CoA.

Dissolve biotin-CoA in water to a concentration of 10 mM. Aliquot and store the solution at −20°C before use.

3.2. Expressing and purifying the Sfp enzyme

Transform the pET29-Sfp expression plasmid into E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS chemical competent cells. Plate out the transformation mixture on a LB Agra plate supplemented with 50 μg/mL kanamycin. Incubate the plates at 37°C for overnight.

Pick a single colony and inoculate 10 mL LB culture with 50 μg/mL kanamycin. Incubate the culture in a 37°C shaker for overnight.

Use the overnight culture to inoculate 1 L LB with kanamycin. Shack the culture at 37°C for 4–6 hours until the OD600 of the culture reaches 0.5.

Reduce the temperature of the shaker to 20°C. Shake for an additional 30 minutes. Add IPTG to the culture to a final concentration of 1 mM. Incubate the culture overnight.

On the next day, harvest the cells by centrifugation (4000g, 15 min). Pour out the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellets in 6 mL lysis buffer with 1 unit/mL DNAse I.

Lysis the cell by passing the cell suspension twice through a French press machine at a pressure of 16,000 psi.

Collect the lysate and precipitate the cell debris by high speed centrifugation (95,000g, 30 min).

Save the clarified supernatant from the centrifugation bottle. Incubate the supernatant with 1 mL Ni-NTA resin for 3–4 h at 4°C.

Load the supernatant with Ni-NTA resin onto a gravity column. Drain the cell lysate through the column. Wash the resin twice, each time with 10 mL lysis buffer. Wash the resin once with 10 mL wash buffer.

Elute the Sfp protein from the column with 6 mL elution buffer. Adjust the flow to 1 drop/second during elution.

Add the elution factions to a dialysis tube with a molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) of 10 kD and dialyze the eluent against the dialysis buffer for Sfp. Allow 4 hours or more to equilibrate. Put the dialysis tube into fresh solution and dialyze again for 4 hours or more.

Concentrate the Sfp solution to more than 5 mg/mL by a Centriprep concentrator. Store the aliquots at −80°C.

3.3. Labeling PCP-UAE protein with biotin-CoA catalyzed by Sfp and immobilizing biotin-labeled protein on the streptavidin plate

Set up 100 μL labeling reaction with 5 μM PCP-UAE, 5 μM biotin-CoA, and 0.3 μM Sfp in the Sfp reaction buffer.

Incubate the reaction at room temperature for 1 hour.

Add 1/3 volume of 3% BSA in TBS to the labeling reaction so that the final concentration of BSA is 1% in the reaction mixture.

Add 100 μL labeling reaction mixture with 1% BSA to each well of the streptavidin plate.

Equilibrate the plate for 1 hour at room temperature to allow the binding of biotin-labeled protein to the plate.

Wash the plate with TBS for three times, each time with 250 μL TBS for each well in the plate.

Add 150 μL TBS to each well of the plate. Cover the plate with parafilm. Store the plate at 4°C before use.

3.4. Preparing the phage library for selection

The phage selection experiment takes two days. In day one, the DNA of the phagemid library is transformed into E coli cells and the production of the UB variants is induced for overnight for their display on the phage surface. On the second day, phage library is harvested, and PCP-UAE coated streptavidin plate is used for the selection of catalytically active UB variants.

Transform the phagemid library of UB into SS320 super competent cells infected with M13KO7 helper phage. Add the transformed cells to the SOC media and grow for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking.

Use the cell culture to inoculate 100 mL 2YT supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and kanamycin (50 μg/mL). Shake the cell culture overnight at 37 °C.

On the next day, spin down the cells with centrifugation at 2,795 g. Pour the supernatant into a 500 mL centrifuge bottle. Add ¼ volume of PEG solution to the bottle. Mix the PEG thoroughly with the supernatant. Incubate the bottle on ice for 1 hour.

Centrifuge the bottle at 9,055 g for 30 minutes to precipitate the phage particles. Discard the supernatant. Drain the residue PEG solution from the bottle.

Resuspend the phage pellet in 2 mL TBS.

Add the phage solution to Eppendorf tubes and centrifuge at 11,336 g to remove the cell debris.

Save the supernatant from the tube as the phage solution for the selection reaction. Store the phage solution at 4°C.

3.5. Phage selection with biotin-labeled PCP-UAE immobilized on the streptavidin plate

Empty solution in the wells of the streptavidin plate immobilized with biotin-labeled PCP-UAE.

Dilute phage solution in the UAE reaction buffer to about 1 × 1011 phage /mL.

Add 100 μL phage solution to each well of the streptavidin plate. Incubate the UB displayed phage with immobilized UAE for 1 hour to allow the formation of UB~UAE conjugate.

Remove the supernatant in the well by pipetting and wash the wells with TBS-T for 30 times, each time with 250 μL TBS-T for each well.

Wash the wells with TBS for an additional 30 times.

Add 100 μL phage elution buffer containing DTT to each well and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes.

Add the eluent to 10 mL of log phase E. coli XL1-Blue cells and shaken at 37°C for one hour to allow phage infection of the cells.

Plate out the cell culture on LB agar plate supplemented with 2% (w/v) glucose and 100 μg/mL ampicillin. Incubate the plates overnight at 37°C.

On the next day, scrape the colonies on the plate with a sterilized spatula.

Extract plasmid DNA from the cells with a QIAprep Plasmid Miniprep kit. The phagemid DNA is then used for the next round of phage amplification and selection.

In parallel to the selection reaction, also set up control reactions excluding key components such as ATP or PCP-UAE immobilization on the streptavidin plate. After each round of selection, titer phage particles eluted from the selection and the control reactions. Successful phage selection should show stepwise enrichment of the phage particles from the eluent of the selection reaction comparing to the controls. During iterative rounds of selection, the number of the input phage particles, the concentration of E1 enzymes, and the reaction time can also be decreased in each round to increase the stringency of phage selection.

4. Notes

4.1

Because Sfp catalyzed protein labeling is highly specific, the biotin-labeled protein in the reaction mixture can be directly used for binding to the streptavidin plate despite the presents of other components of the labeling reaction such as the Sfp enzyme, excess biotin-CoA, and AMP, etc. To increase the selection efficiency and avoid nonspecific binding of biotin-CoA with proteins on the phage or yeast cell surface, the labeling reaction mixture can be purified by desalting with a Centriprep concentrator or by passing through a desalting column.

4.2

We typically use freshly labeled biotin-UAE conjugate for the selection of UB variants by phage display. In this way the enzymatic activity of UAE would be the highest for the selection reaction. On the other hand the biotin-Ppant conjugate attached to the PCP tag is very stable and the labeled protein can be stored for years in a −20°C freezer without losing the label on the protein.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a National Science Foundation CAREER award (1057092) and a National Institute of Health grant 1R01GM104498 to J.Y.

References

- 1.Yin J, Lin AJ, Golan DE, Walsh CT. Site-specific protein labeling by Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase. Nature Protocols. 2006;1:280–285. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambalot RH, Gehring AM, Flugel RS, Zuber P, LaCelle M, Marahiel MA, Reid R, Khosla C, Walsh CT. A new enzyme superfamily - the phosphopantetheinyl transferases. Chem Biol. 1996;3:923–936. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.La Clair JJ, Foley TL, Schegg TR, Regan CM, Burkart MD. Manipulation of carrier proteins in antibiotic biosynthesis. Chem Biol. 2004;11:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin J, Liu F, Li X, Walsh CT. Labeling proteins with small molecules by site-specific posttranslational modification. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7754–7755. doi: 10.1021/ja047749k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yin J, Liu F, Schinke M, Daly C, Walsh CT. Phagemid encoded small molecules for high throughput screening of chemical libraries. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:13570–13571. doi: 10.1021/ja045127t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin J, Lin AJ, Buckett PD, Wessling-Resnick M, Golan DE, Walsh CT. Single-cell FRET imaging of transferrin receptor trafficking dynamics by Sfp-catalyzed, site-specific protein labeling. Chem Biol. 2005;12:999–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin J, Straight PD, Hrvatin S, Dorrestein PC, Bumpus SB, Jao C, Kelleher NL, Kolter R, Walsh CT. Genome-wide high-throughput mining of natural-product biosynthetic gene clusters by phage display. Chem Biol. 2007;14:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Z, Cironi P, Lin AJ, Xu Y, Hrvatin S, Golan DE, Silver PA, Walsh CT, Yin J. Genetically encoded short peptide tags for orthogonal protein labeling by Sfp and AcpS phosphopantetheinyl transferases. ACS Chem Biol. 2007;2:337–346. doi: 10.1021/cb700054k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin J, Straight PD, McLoughlin SM, Zhou Z, Lin AJ, Golan DE, Kelleher NL, Kolter R, Walsh CT. Genetically encoded short peptide tag for versatile protein labeling by Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15815–15820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507705102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George N, Pick H, Vogel H, Johnsson N, Johnsson K. Specific labeling of cell surface proteins with chemically diverse compounds. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8896–8897. doi: 10.1021/ja048396s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waichman S, Bhagawati M, Podoplelova Y, Reichel A, Brunk A, Paterok D, Piehler J. Functional immobilization and patterning of proteins by an enzymatic transfer reaction. Anal Chem. 2010;82:1478–1485. doi: 10.1021/ac902608a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong LS, Okrasa K, Micklefield J. Site-selective immobilisation of functional enzymes on to polystyrene nanoparticles. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:782–787. doi: 10.1039/b916773k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong LS, Thirlway J, Micklefield J. Direct site-selective covalent protein immobilization catalyzed by a phosphopantetheinyl transferase. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12456–12464. doi: 10.1021/ja8030278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Band PA, Blais S, Neubert TA, Cardozo TJ, Ichtchenko K. Recombinant derivatives of botulinum neurotoxin A engineered for trafficking studies and neuronal delivery. Protein Expression Purif. 2010;71:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawamura T, Stephens B, Qin L, Yin X, Dores MR, Smith TH, Grimsey N, Abagyan R, Trejo J, Kufareva I, Fuster MM, Salanga CL, Handel TM. A general method for site specific fluorescent labeling of recombinant chemokines. PLoS One. 2014;9:e81454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Zhou Z, Walsh CT, McMahon AP. Selective translocation of intracellular Smoothened to the primary cilium in response to Hedgehog pathway modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2623–2628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812110106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao B, Bhuripanyo K, Schneider J, Zhang K, Schindelin H, Boone D, Yin J. Specificity of the E1-E2-E3 Enzymatic Cascade for Ubiquitin C-terminal Sequences Identified by Phage Display. ACS Chemical Biology. 2012;7:2027–2035. doi: 10.1021/cb300339p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao B, Bhuripanyo K, Zhang K, Kiyokawa H, Schindelin H, Yin J. Orthogonal Ubiquitin Transfer through Engineered E1-E2 Cascades for Protein Ubiquitination. Chem Biol. 2012;19:1265–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang K, Li H, Bhuripanyo K, Zhao B, Chen TF, Zheng N, Yin J. Engineering new protein-protein interactions on the beta-propeller fold by yeast cell surface display. Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology. 2013;14:426–430. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang K, Li H, Bhuripanyo K, Zhao B, Zheng N, Yin J. Engineering new protein-protein interactions on the beta-propeller fold by yeast cell surface display. ChemBioChem. 2013;14:426–430. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee I, Schindelin H. Structural insights into E1-catalyzed ubiquitin activation and transfer to conjugating enzymes. Cell. 2008;134:268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulman BA, Harper JW. Ubiquitin-like protein activation by E1 enzymes: the apex for downstream signalling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:319–331. doi: 10.1038/nrm2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]