Abstract

Although overall HIV rates have declined in the U.S. over the past two decades, these declines have been accompanied by steady growth in infection rates among African Americans, creating persistent racial disparities in HIV infection. News media have been instrumental in educating and informing the public about the epidemic. This content analytic study examines the frequency and content of coverage of HIV/AIDS in national and local U.S. daily newspapers from December 1992 through December 2007 with a focus on the presentation of risk by population subgroups. A computerized search term was used to identify HIV/AIDS-related news coverage from 24 daily U.S. newspapers and one wire service across a 15-year period (N = 53,934 stories). Human and computerized coding methods were used to examine patterns in frequency and content in the sample. Results indicate a decline in coverage of the epidemic over the study period. There was also a marked shift in the portrayal of risk in the U.S., from a domestic to an international focus. When coverage did address HIV/AIDS among groups with disproportionately high risk in the U.S., it typically failed to provide context for the disparity beyond individual behavioral risk factors. The meta-message of news coverage of HIV during this period may have reduced the visibility of the impact of HIV/AIDS on Americans. The practice of reporting the racial disparity without providing context may have consequences for the general public’s ability to interpret these disparities.

More than 30 years after the emergence of AIDS, African Americans account for almost half of new AIDS cases while representing only 12.3% of the total population (CDC 2011). HIV infections rates are particularly high for African American women, youth, and men who have sex with men. Since the beginning of the epidemic, the news media has played an integral role in educating the public about the disease (Backstrom 1998; Brodie et al. 2004). Scholars have criticized media coverage for failing to adequately cover the epidemic’s seriousness among African Americans. Some argue that the media’s silence contributed to the increased prevalence among this population (Cohen 1999; Donovan 1993; Fee and Fox 1992; Levenson 2005). In a Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF, 2011) public opinion survey, 73% of African Americans reported wanting to know more about HIV transmission. Given the growing racial disparities in HIV transmission, the criticisms levied against the press early in the epidemic, and the vital role of news media in communicating the epidemic, this study examines news coverage of HIV/AIDS in the latter half of the epidemic, with a focus on race and attributions of risk.

MEDIA COVERAGE OF HIV/AIDS

Media coverage of HIV/AIDS has influenced public knowledge of, opinion about, and behavioral response toward the disease, as well as public policy regarding research, funding, and education (Brodie et al. 2004; KFF 2011; Shilts 1987). The news media continues to be a vital source of information about HIV/AIDS for most Americans 30 years into the epidemic (KFF 2005; KFF 2011; Brodie et al. 2004). Because of this critical role, scholars have examined how information about HIV/AIDS is communicated (Brodie et al. 2004; Cohen 1999; Donovan 1993; Hertog and Fan 1995; Rogers, Dearing, and Chang 1991; Shilts 1987). In terms of sheer quantity, Brodie and colleagues (2004) reported that HIV/AIDS news coverage peaked in 1987 and has since declined in both print and broadcast media. This decline preceded the decline in new AIDS cases by almost a decade and continued as the cumulative number of AIDS cases rose and disparities widened. In terms of portrayal of the affected population, only 3% of stories overall highlight minorities in the U.S. (Brodie et al. 2004). Cohen’s (1999) analysis of HIV/AIDS coverage in the New York Times from 1981 to 1993 found that only 5% of the stories mentioned African Americans specifically, whereas African Americans constituted 32% of all AIDS cases. Additionally, coverage of HIV/AIDS in the New York Times declined as the number of AIDS cases among African Americans markedly increased (Cohen 1999).

The way news is reported has implications for audience understanding of the importance of the problem and potential solutions. From an agenda-setting perspective, the public perceives as important the issues that are prominently featured in mass media (McCombs and Reynolds 2009). Limited or shallow coverage of HIV can minimize the epidemic in the public’s eye. In addition, how issues are presented in news influences people’s interpretations (Iyengar 1994). Evidence from studies examining the effects of agenda setting and framing demonstrate that the presentation of particular problems influences individuals’ rating of that problem’s importance, interpretation, and potentially viable solutions (McCombs and Reynolds 2009; Tewksbury and Scheufele 2009). Thus, failure to provide adequate coverage of the epidemic among disproportionately affected groups can reduce the extent to which the public sees widening disparities as an important problem. In addition, coverage of HIV/AIDS through an individual or episodic lens can privilege prevention efforts that target individual risk behavior over efforts to influence structural determinants, even though addressing structural drivers of the disease may be more effective in slowing the epidemic (Niederdeppe et al. 2008).

This study aims to extend the previous research by examining the patterns of HIV/AIDS coverage in newspapers using a 15-year sample of 24 national and local daily newspapers. The goal is to gain a more nuanced understanding of coverage by exploring the nature of coverage related to portrayals of race and risk.

Methods

Newspaper Sample

As with similar studies of this nature, we treat newspaper coverage of HIV/AIDS as a proxy for coverage of HIV/AIDS in the national news media (Niederdeppe, Frosch, and Hornik 2008; Smith et al. 2008; J Stryker et al. 2006; Yanovitzky and Stryker 2001). In her validation study, Stryker (2008) reported that content analyses that sample the Associated Press, the New York Times, and the Washington Post provide the most accurate measure of the larger news media environment, including print and broadcast media. In addition, newspapers archives are among the most reliable, consistent measures of the news environment across geographic and time bounds, strengthening construct validity in the study. Consequently, this study includes the Associated Press, the New York Times, and the Washington Post, as well as 22 other U.S. newspapers with high levels of circulation, that were continuously indexed in the Lexis Nexis database during the sample period..

We assessed newspaper coverage with a content analysis of news stories related to HIV or AIDS risk published in the Associated Press wire service and in 24 daily newspapers in the U.S. with high levels of circulation, ranging from 260,000 to 2.5 million in 2006. We chose the newspapers from the top 40 U.S. daily newspapers in circulation that were also archived in the Lexis Nexis database from December 1, 1992 to December 31, 2007. The sample included newspapers with national circulation (such as USA Today, New York Times, Los Angeles Times) and regional and local papers (such as Philadelphia Inquirer, Orlando Sentinel).

Procedure

In order to adequately capture the magnitude and nature of newspaper coverage of HIV/AIDS, we conducted the content analysis in two phases: the first used a computerized coding technique and the second used traditional human coders. The research team developed computerized search terms to cull general HIV/AIDS news stories and HIV/AIDS risk related stories from all of the news stories in the sample. Human coders focused on a subsample of HIV/AIDS risk stories to identify attributions of risk by racial group. The human coders first established high levels of intercoder reliability for initial identification of general HIV/AIDS stories and HIV/AIDS risk stories (general HIV/AIDS: kappa = .859, standard error = 0.067; Z = 12.84; P <.001; HIV/AIDS risk: kappa = .828, standard error = 0.059, Z = 13.97, P < .001).

Computerized Coding

Using a procedure detailed by Stryker, Wray, Hornik, and Yanovitzky (2006), we crafted and tested two validated computerized search terms to identify relevant stories across the large volume of news. We evaluated the quality of the search terms on the basis of recall (the search term’s ability to retrieve all of the relevant stories) and precision (its ability to exclude irrelevant stories from retrieval). We used recall and precision statistics analogous to those described by Yanovitzky and Stryker (2001) to assess the validity of each computerized search term. To correct for the biases related to recall and precision—underestimating and overestimating, respectively, the true number of relevant stories—we adjusted the number of stories captured each month by the proportion of recall to precision.

General HIV/AIDS news stories

The first validated search term identified “general HIV/AIDS news stories,” defined as stories that focused on or discussed HIV/AIDS, including reports of biomedical breakthroughs, celebrities with HIV/AIDS, fundraising events, or HIV/AIDS risk (Appendix A). This variable represents an estimate of the total number of stories each month across the entire newspaper sample that included any focus on or discussion of HIV/AIDS. The computerized search term captured 99.15% (±5%) of all HIV/AIDS related stories (recall) and accurately categorized 96.95% (±5%) captured stories as relevant (precision). The validated general HIV/AIDS search term retrieved a total of 53,934 stories from December 1992 through December 2007. We adjusted the sample by 0.98—the proportion of recall to precision—to correct for oversampling of nonrelevant stories (J Stryker et al. 2006). After the adjustment, the estimated total number of relevant stories was 52,739.

HIV/AIDS risk stories

The second computerized search term captured the HIV/AIDS risk related stories that explicitly discussed individual or population level risk, termed “HIV/AIDS risk stories” (see Appendix B). The language varied greatly but often included epidemiological evidence of prevalence or incidence rates. For example, some stories would explicitly mention case rates and prevalence statistics: “2,514 new HIV cases have been reported in Houston. Of those, 61% were Black. In the 13 to 19 age group, 78% were Black girls.” Other stories used descriptive language over statistics to convey HIV/AIDS risk: “the devastating impact of HIV/AIDS on the Native American Community.” We excluded stories from the analysis if they focused on aspects of HIV/AIDS other than risk, such as funding, policy debates, or biomedical news. Thus, this variable represents a monthly estimate of the number of stories across the newspaper sample that specifically mentioned or discussed HIV/AIDS risk at a population or individual level. The search term captured 78.6% (±5%) of all AIDS/HIV risk related stories and correctly categorized 88.6% (±5%) captured stories as relevant. The validated HIV/AIDS risk search term retrieved 21,906 stories. After the recall to precision adjustment, the HIV/AIDS risk search term yielded 19,453 relevant stories.

Human Coding

Racialized risk stories

The second phase of the content analysis relied on human coders to identify “racialized risk” statements, in which attributions of risk in the news story were related to race. During this phase, the coders hand-coded a random sample of the HIV risk stories, giving particular attention to which groups were presented as at-risk and to patterns in language, news events, and topical focus. We used a stratified random sampling technique to maintain the integrity of monthly quantitative variations, which yielded five-day composite weeks from each month, resulting in 3,166 stories from the total population of 19,453 HIV/AIDS risk stories (16.28%; Riffe, Lacy, and Drager 1996).

African American risk stories and African/Caribbean risk stories

To capture attributions of HIV/AIDS risk, trained human coders coded 16.28% of HIV/AIDS risk stories (n = 3,166). We then used the number of stories coded as indicating African American risk to estimate the number of African American risk stories presented monthly by multiplying the monthly counts by six to approximate a 30-day month. We then divided these monthly estimates by the total number of risk stories each month, creating the percentage of racialized risk stories related to African Americans. We used the same procedure to generate monthly count estimates of racialized risk stories related to African or Caribbean nations. Thus, these variables represent HIV/AIDS risk stories that specifically attribute elevated risk for HIV/AIDS to African Americans or to people from African or Caribbean nations.

To capture trends qualitatively, we analyzed the sample of stories focusing on risk-related statements chronologically. During this phase, we coded which groups were presented as at-risk as well as patterns in language, news events, and shifts in coverage emphasis. We then evaluated the patterns that arose from the qualitative data against the quantitative findings.

For quantitative analysis, we aggregated the data and analyzed shifts in risk portrayals and coverage frequency at the monthly level. We used Stata MP version 12 to conduct independent t tests of racialized risk categories to assess significant fluctuations in coverage across time.

Results

HIV/AIDS Coverage Declines

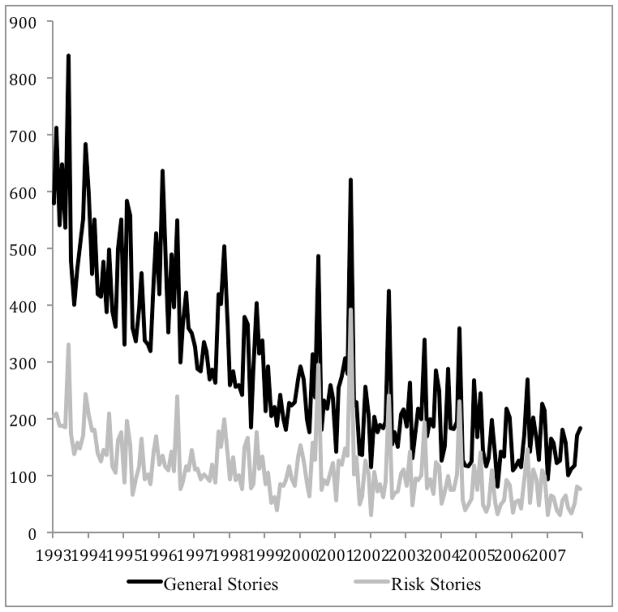

From 1993 to 2007, there was a significant decline in coverage of HIV/AIDS by the mainstream press (see Figure 1). The average monthly number of general HIV/AIDS news stories fell from 578.3 (SD = 122.9) in 1993 to 140.5 (SD = 31.8) in 2007 (t (179) = −26.34, p < .05). HIV/AIDS risk stories also exhibited significant declines, falling from a monthly average of 201.7 (SD = 53.39) in 1993 to 54.6 (SD =18.0) in 2007 (t (179) = −20.09, p<.05). This translates to approximately a 76% decrease in all HIV/AIDS coverage and a 72.9% decrease in risk-related HIV/AIDS coverage. There was also less fluctuation in coverage, evidenced by the substantially smaller standard deviation in 2007 than in 1993.

Figure 1.

General HIV/AIDS Stories and HIV/AIDS Risk Stories, Monthly Counts (n=53,394)

Everyone’s Problem

After 1992, one theme in coverage was to democratize HIV/AIDS, focusing on HIV/AIDS as “everyone’s” problem. In 1993, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced that AIDS had emerged as the leading cause of death among men ages 24–44 in the United States (DHHS 2011). This caused AIDS to be viewed as a universal problem instead of as a disease that only affected gays, Haitians, hemophiliacs, and drug users. By 1994, AIDS was also announced as the leading cause of death among women of the same age group (KFF 2007). As a result of these announcements, news coverage of the disease increased greatly. General coverage of HIV/AIDS peaked in June of 1993, with 840 stories in one month. Risk-related coverage rose, with articles often restating the CDC prevalence statistic, but stories also included discussions of HIV/AIDS risk.

During this period, HIV/AIDS risk stories were regularly framed as human interest pieces that highlighted individual stories of infection. Stories often highlighted infection through nonrisky behavior, such as mother-to-child vertical transmissions and transmission from blood transfusions. The practice of highlighting novel, nonrisky modes of transmission further democratized HIV/AIDS, portraying a larger segment of the population as vulnerable to the disease. This may have disentangled stigmatized sexual and drug use behavior from HIV/AIDS, thereby increasing public attention to the disease.

By 1996, AIDS had moved from a fatal to a chronic disease, and HIV/AIDS news coverage began to take a decidedly optimistic tone. Two significant changes in HIV/AIDS morbidity and mortality were widely reported in 1996–97. For the first time, the number of new AIDS cases in the U.S. declined (DHHS 2011), and in 1997, there were steep declines in AIDS-related deaths following the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) as the standard of HIV care (DHHS 2011). This optimistic tone in coverage was accompanied by a steady decline in the frequency of HIV/AIDS reporting. By 1997 the frequency of reporting on HIV/AIDS decreased by 58.6% from its 1992 levels.

During this period of optimism, there was also a small increase in coverage of HIV/AIDS risk among African Americans and in developing nations, with a particular focus on Africa or African nations. Although they were still featured in a minority of risk stories, African Americans were discussed in 13.19% of risk stories in 1999, compared to 8.23% in 1993. For Africa-related stories, the percentage rose from 3.1% in 1993 to 35.2% in 1999. As AIDS among most Americans was declining, news coverage shifted to communities where the fight against AIDS was less successful.

An African Problem

In addition to overall coverage declines, the 1990s saw precipitous declines in domestic HIV/AIDS risk coverage, with a greater proportion of the coverage focusing on AIDS in Africa (Figure 2). Stories about HIV/AIDS in Africa first began to appear on a limited basis. In 1996, African HIV/AIDS stories accounted for 5.38% (SD = 8.12) of risk-related coverage. The percentage jumped to 36.73% (SD = 20.06) by 1999 and peaked at 48.83% (SD = 23.17) in 2003. These annual increases represent statistically significant increases across the sample period (F(13) = 9.57, p < .05).

Figure 2.

HIV/AIDS Risk Stories, African American & African/Caribbean Risk Stories, Average Monthly Estimated Counts (n=3,166)

Coverage of HIV/AIDS globally extended beyond reporting prevalence and incidence rates. There were several distinct patterns in reporting on the African crisis. International coverage focused on two elements: the actions of the U.S. government and global governing bodies and the epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa.

Increased news interest was generated by national political actors and international governing bodies, like the United Nations with its call for the eradication of HIV/AIDS. Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush made the continent of Africa the explicit focus of HIV/AIDS policy and funding, generating increases in news coverage in the mainstream press. Reporting on presidential actions often failed to mention HIV/AIDS in the United States, treating it exclusively as a problem of other countries. For example, discussions of the HIV/AIDS pandemic included worldwide country and region-specific prevalence statistics but typically excluded prevalence statistics for the U.S., even in tables and charts. Africa emerged as a prominent focus of reporting on AIDS in part because of the ravaging epidemic in several sub-Saharan countries. However, this frame of coverage often neglected to mention that comparably high prevalence rates existed among African Americans. By 1999, African Americans were 12% of the U.S. population and accounted for 47% of newly reported AIDS cases (KFF 2001).

In Africa: The Best and Worst Case Scenarios

Uganda received increased media coverage after President Bush’s 2003 visit to highlight Uganda’s successes controlling the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Chen 2003; Hillman 2003; Onyango-Obbo 2003; Roth 2003). Uganda experienced a dramatic decline in its AIDS case rates, which have been attributed to public education campaigns. The AIDS prevention message in Uganda focused on the ABCs: Abstinence, Be Faithful and Use Condoms (Stoneburner and Low-Beer 2004). Bush’s visit and Uganda’s successful HIV/AIDS prevention policies elicited significant coverage, which Bush used to gain support for funding domestic and international abstinence-only education programs.

AIDS in Africa increasingly became a rhetorical tool that journalists used as an example of the worst-case scenario, such as in the following quotes: “an AIDS epidemic of African proportions” (Harden 2000), “Some AIDS experts have characterized the rates of infection among gay men in San Francisco as ‘sub-Saharan’” (Heredia 2000), referring to the AIDS epidemic sweeping Africa, and “the Nepalese face a full-blown African-style AIDS epidemic and trafficking is a primary cause ”(West 2002). The technique of using AIDS in Africa as a comparison in order to raise the claims of severity of the local epidemic also served to cement the perception of AIDS as a disease with its epicenter in sub-Saharan Africa.

Although HIV/AIDS remained a severe problem for African Americans domestically, much of the mainstream press moved to covering the African AIDS crisis. Before 1999, there was more overall coverage of African Americans than Africans, but coverage of African AIDS eclipsed African American AIDS coverage during that year. Overall, the percentage of risk coverage focused on African AIDS was nearly three times the percentage of coverage focused on African Americans (36.72% vs. 13.19%).

Coverage of HIV/AIDS among African Americans

The percentage of risk coverage of HIV/AIDS among African Americans rose from 8.22% (SD = 8.53) in 1993 to 14.97% (SD = 35.80) in 2006. The trend toward increased coverage was driven primarily by overall declines in risk coverage, not by increased stories on the African American epidemic. Figure 3 shows monthly fluctuations in the percentage of risk coverage focused on African Americans: it declined slightly, with the average monthly coverage falling from 29 stories per month in 1993 to 24 stories per month in 2000 and 22 stories per month in 2006. Meanwhile, the epidemic disproportionately affected this population, with African Americans accounting for 36% of new AIDS cases in 1993 and 51% by 2007 (CDC 2004; CDC 2007; CDC 2011). News coverage failed to be proportional to the growing disease prevalence in the African American community.

Figure 3.

Percentages of African American Stories vs. Africa related Stories, Monthly Average Estimates (n=3,166)

As we previously noted, by 1996, the national decline in new AIDS cases and AIDS deaths led to optimistic HIV/AIDS reporting, although these declines were not uniform. Although AIDS was no longer a top 10 killer of Americans aged 25–44, it remained the number one killer of African Americans in the same age group. Coverage of AIDS among African Americans was limited, but we opted to move beyond quantity to examine dominant themes in the content of the coverage. In 1994, risk-related coverage began to include discussions of HIV/AIDS among women and in communities of color. African American political leaders garnered some news coverage by declaring “a state of emergency,” which led to the establishment of the Minority AIDS initiative (Kaiser Family Foundation 2007). By 1998, news stories and activist alike began to discuss HIV/AIDS in terms of race more explicitly: “The AIDS epidemic in our region is growing blacker, browner, younger and more female” (Savage 1998). In 1998, both St. Louis and Kansas City declared a state of emergency among African Americans with HIV/AIDS. By 1999, news stories begin to include “people of color” in the standard list of at-risk groups, which before this point had typically been gays and intravenous drug users (Vollmer 1999).

One story strikingly exhibited the tension between optimism and disparity. It begins with the headline “Research pays off in the fight against AIDS,” and follows in the body, “The extraordinary drop in number of AIDS deaths. … AIDS has gone from being the 8th leading cause of death to 14th” (“Research Pays Off in Fight Against AIDS” 1998). It addresses disparity: “AIDS is still the leading cause of death among African Americans … and the longer survival rate means a greater chance of infecting others.” The story depicts the positive effect of prolonged life with HAART therapy for African Americans as a negative because the resulting increased life expectancy prolonged the period of time during which infected African Americans remained a threat to society.

The relatively few stories about African Americans often highlighted a state of emergency, using the disparity between African Americans and Whites to highlight the severity of the epidemic (Shaw 2000). Generally, two types of stories related the epidemic to the Black community: those that focused on AIDS among African Americans and those that only alluded to the crisis. Much of the coverage fell into the latter category, providing little context to explain the racial disparities in HIV/AIDS. For example, seven stories from 1994 covered the statistic that 55% of new HIV/AIDS cases were among minorities (Becker 1994; Collins 1994; Cooper 1994; Painter 1994), but only one of the seven contextualized or discussed possible reasons for the disparity. In another instance, six stories explicitly covered a 1995 biomedical report in the journal Science that presented the high rates of HIV/AIDS among Blacks and Hispanics. Half of the stories provided no additional information about the higher rates among Blacks and Hispanics, providing little context, discussion of causation or potential solutions. The other half provided one or two additional sentences beyond the presentation of the prevalence statistics (“AIDS Cases in U.S. Since ’81: 501,310” 1995; “AIDS Virus Infections Estimated; 1 in 92 Young U.S. Men Believed HIV-positive” 1995; “More the 500,00 AIDS Cases Reported in the U.S.” 1995; Neergard 1995). When stories did offer more in-depth discussions about the epidemic among African Americans, the journalists tended to emphasize the role of individual behavior as a cause of the disparity, although much of the research suggests that structural determinants are responsible for much of the AIDS crisis in Black America (Adimora, Schoenbach, and Floris-Moore 2009).

Discussion

This content analysis offers a chronological investigation of news coverage of HIV/AIDS and in the process raises important questions that deserve further study, particularly because newspapers often set the agenda for other news media, as well as for the public (Chapman 2004; Fan 1988; McCombs and Reynolds 2009; Niederdeppe, Frosch, and Hornik 2008; Stryker 2008). The primary mission of the news media is not to educate the public about HIV/AIDS, although it often fills that role. Indeed, the majority of Americans of all age groups and racial backgrounds report that the media is their top source of information about HIV/AIDS (KFF 2011). The industry must continually respond to pressures to provide newsworthy content. However, newsworthiness, often typified by novelty or sensationalism, does not lend itself to contextualized reporting on a topic, particularly when the topic is a disease as complex and persistent as HIV/AIDS (Shoemaker and Mayfield 1987). Still, the larger public agenda is linked to what is and is not reported about HIV/AIDS—what is deemed newsworthy. Although it is beyond the scope of this study to assess the impact of content on the public agenda and subsequent public opinion, it is worthwhile to consider the findings in light of the state of public opinion during the same time frame.

There was a significant decrease in the coverage of HIV/AIDS from 1993 to 2007. News coverage was highest when HIV/AIDS was viewed as a fatal disease that represented a domestic threat for all Americans. Coverage substantiality declined as the perceived severity and susceptibility decreased (KFF 2006). As HIV/AIDS moved from a death sentence to a chronic disease, its novelty declined (Hilgartner and Bosk 1988). As suggested by the results of this study, the number of Americans who receive information about HIV/AIDS in the media or otherwise has also dramatically declined. In 2009, shortly after the end of the study period, 45% of Americans said they had seen, heard, or read at least some information about HIV/AIDS in the U.S. in the past year, compared to 70% in 2004 (KFF 2011). In order for a public issue to retain enough priority to remain a news issue over many years, it must continue to offer new information, which journalists can reframe to make the same issue important in a different way. Newsworthy stories include qualities like sensationalism, conflict, mystery, celebrity, deviance, tragedy, timeliness, and proximity (Shoemaker and Mayfield 1987). However, the disparate prevalence of the disease among African Americans never sustained significant media attention. In contrast, the African AIDS epidemic generated substantial coverage. Although the epidemic raged in both populations, this finding suggests that prevalence alone was not enough to place AIDS on the national agenda. Instead, the prevalence, combined with the significant presidential attention to AIDS in Africa, was instrumental in generating increased news coverage for the global epidemic.

From an agenda-setting perspective, the simultaneous shifts in coverage from HIV/AIDS domestically to AIDS internationally, specifically in Africa, may have signaled to the general population that HIV/AIDS was becoming less important domestically and more important internationally. Public opinion data suggest a dramatic decline in the extent to which Americans report that HIV is the most urgent health problem domestically, falling from 68% in 1987 to 17% by 2006, a trend that persists many years after the study period (7% in 2011). This decline in national perceptions of AIDS as an important problem occurred even as dramatic disparities in HIV continued to widen. At the same time, the number of Americans who report that HIV/AIDS is the most urgent problem for the world is substantially higher (KFF 2011). Although that number has also declined, during the study period it was double the number of Americans who named HIV as the most urgent national health problem. In turn, consideration of HIV/AIDS as a less urgent national problem but more urgent international problem may have reduced support for policies and funding streams that could have more quickly or more effectively addressed the epidemic domestically while encouraging support for international efforts to curb the epidemic both in terms of policy and humanitarian aid resources.

As coverage of HIV/AIDS in Africa increased, coverage of HIV/AIDS among African Americans declined slightly and failed to increase in response to a large shift in the disease burden to African Americans, particularly among women, youth, and men who have sex with men (CDC 2011). This decline in coverage, coupled with the increasing disparity in infection rate, raises concerns about the potential consequences of the silence around disparate transmission. From an agenda-setting perspective, this implies that while the epidemic was gaining steam in the African American community, it was losing the fight for national attention..

Approximately 10% of risk-related news stories directly addressed HIV/AIDS in the African American community. The quantity was minimal, and the coverage that did exist provided little context on how social context and structural determinants influence the trajectory of the disease. This absence of contextual framing may have influenced the interpretation of the problem and, consequently, perceptions of viable solutions. By presenting a decontextualized report of the disparate infection rates in the African American community in the U.S. and neglecting to discuss the social determinants of HIV-related risk, the coverage highlighted individual behavior as the root cause for disparate infection rates. An understanding of health outcomes based in individual responsibility may result in support for individual-level solutions. These can reduce transmission, but reporting that omits discussion of structural and social determinants may reduce or impede support for interventions that are necessary to eradicate disparities. Although HIV/AIDS transmission has declined overall in the U.S. and HAART and other antiretroviral treatments have afforded those infected the potential to live longer, healthier lives, HIV/AIDS remains a prominent health issue in the U.S. and is unlikely to be resolved without a well-resourced effort in support of a cure or vaccine. News media reports of the state of the epidemic should strive to provide contextualized understandings of a disease trajectory. This may promote support for individual, social, and structural level interventions by enabling more contextualized understandings of the causes and potential solutions for disparities, thereby raising structural solutions on the public agenda (Niederdeppe et al. 2008).

On the basis of our findings, we agree with Donovan (1993) that “Unless the American media’s core constituency of middle-class individuals is perceived to be at risk, a rampant disease like AIDS does not constitute a news story with high news value” (p. 13). Although the exclusion of race in coverage early in the epidemic may have been a strategy to gain widespread attention to the epidemic by appealing to a broader audience, the unintended consequences of this exclusion may have contributed to the disparate infection rates among African Americans. As the epidemiological data showed declining morbidity and mortality rates for the U.S. population broadly, we found evidence of deep declines in coverage and less reporting on risks of HIV/AIDS. Domestic disparities in HIV/AIDS became relegated to the margins and the epidemic in the developing world became more prominent. Although we cannot tease out whether coverage of HIV/AIDS declined because it ceased to be a concern for the American public or concern about HIV/AIDS declined (or remained stagnant) in part because it declined in prominence among American mainstream print media, the correlation is clear.

Although we report potential effects of print media coverage of the epidemic, it is appropriate to note that print media are in constant competition with other mass news and entertainment outlets, so the potential consequences of the coverage we describe here may be mitigated or exacerbated by other forms of mass media. In addition, this study only accounts for news coverage in popular print news media outlets, so it cannot be generalized to other print media sources such as magazines or less popular sources, which may provide information tailored to a smaller segment of the population. However, to the extent that popular print news media and the Associated Press set the agenda for other print and television news outlets, these findings may extend beyond the current sample to an unknown extent (Stryker et al. 2006).

Newspapers are a trusted source of information, and as a consequence may be seen as a form of intervention to reduce the impact of HIV/AIDS in the U.S. Journalists may not see themselves as public health practitioners, but news reporting has implications for the problems that receive public attention, the interpretation of problems, viable solutions to problems, and potentially individual behavior (Niederdeppe et al 2013). News reports that provide well-rounded and diverse perspectives on the trajectory of HIV/AIDS and the current state of HIV/AIDS in the U.S. have the potential to help slow the spread of the epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the funding support of the National Cancer Institute’s Center of Excellence in Cancer Communication (CECCR) located at the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania (P50-CA095856-05).

APPENDIX A: Validated General HIV/AIDS Search Term

(HEADLINE(HIV or (plural (AID))) AND atleast1(BODY(HIV or (plural (AID) and caps (AID))))) OR atleast4(BODY(HIV or (plural (AID) and caps (AID)))) OR atleast4(BODY(HIV and (plural (AID) and caps (AID)))) AND NOT section(deaths OR obit! OR obt! OR death notice! OR in memoriam) AND NOT series(deaths OR obit! OR obt! OR death notice! OR in memoriam))

APPENDIX B: HIV/AIDS Risk Search Term

(HEADLINE(HIV or (plural (AID))) AND atleast1(BODY(HIV or (plural (AID) and caps (AID))))) OR atleast4(BODY(HIV or (plural (AID) and caps (AID)))) OR atleast4(BODY(HIV and (plural (AID) and caps (AID)))) AND ( rate! w/5 (AIDS or HIV or H.I.V.)) or ((plural(case) /5 (AIDS or HIV or H.I.V.)) or Cdc or center for disease control or epidemic or pandemic or incidence or prevalence AND NOT section(deaths OR obit! OR obt! OR death notice! OR in memoriam) AND NOT series(deaths OR obit! OR obt! OR death notice! OR in memoriam))

Contributor Information

Robin Stevens, Email: Robin.stevens@rutgers.edu, Assistant Professor, Department of Childhood Studies, Rutgers University-Camden, 405-407 Cooper Street, Camden, NJ 08105, U.S.A. Phone: (1) 856-225-6083, Fax: (1) 856-225-6742.

Shawnika J. Hull, Email: sjhull@wisc.edu, Assistant Professor, School of Journalism & Mass Communication, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 5164 Vilas Hall, 821 University Ave., Madison, WI 53706, U.S.A.

References

- Adimora A, Schoenbach V, Floris-Moore M. Ending the Epidemic of Heterosexual HIV Transmission Among African Americans. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009 Nov;37(5):468–471. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIDS Cases in U.S. Since ’81: 501,310. Chicago Tribune. 1995 Nov 25; [Google Scholar]

- AIDS Virus Infections Estimated; 1 in 92 Young U.S. Men Believed HIV-positive. Dallas Morning News. 1995 Nov 25; [Google Scholar]

- Backstrom C. The Media and AIDS. Journal of Health & Social Policy. 1998;9(March 1):45–69. doi: 10.1300/J045v09n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker M. On The Issue: Informed Opinions On Today’s Topics; Clean Needles: Solution For An Epidemic? Los Angeles Times. 1994 Sep 9; about:blank. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie M, Hamel E, Brady LA, Kates J, Altman DE. AIDS at 21: Media Coverage of the HIV Epidemic 1981–2002. Nation. 2004;49(68) [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. AIDS Among Racial/Ethnic Minorities -- United States, 1994. MMWR. 2004;43(35):644–647. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Disparities in HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STDS, and TB. 2007 http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/healthdisparities/AfricanAmericans.html.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Among African Americans. 2011 Nov; http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/aa/pdf/aa.pdf.

- Chapman S. Advocacy for Public Health: a Primer. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004 May 1;58(5):361–365. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.018051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E. Los Angeles Times. 2003. Jul 12, The World: A Firsthand Look at Battle Against AIDS; On a Visit to a Clinic in Uganda, Bush Praises That Country’s Efforts to Cut the Rate of Infection and Pledges U.S. Help to Fight the Disease. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C. The Boundaries of Blackness: AIDS and the Breakdown of Black Politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Collins H. Times-Picayune. 1994. Sep 9, Study of HIV-2 Offers Hope; Progression Is Slower Than HIV-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. Buffalo News. 1994. Sep 9, AIDS Toll Is Heavier On Blacks. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. A Timeline of AIDS. 2011 http://aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/hiv-aids-101/overview/aids-timeline.

- Donovan M. Social Constructions of People with AIDS: Target Populations and United States Policy, 1981–1990. Review of Policy Research. 1993 Sep 1;12(34):3–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-1338.1993.tb00548.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan D. Predictions of Public Opinion from the Mass Media: Computer Content Analysis and Mathematical Modeling. Greenwood Publishing Group; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fee E, Fox D. AIDS: The Making of a Chronic Disease. University of California Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Harden B. Dallas Morning News. 2000. Nov 19, Trapped in a Painful Past; In What Was Burma, the People Languisg as Junta Preserves Rule. [Google Scholar]

- Heredia C. San Francisco Chronicle. 2000. Sep 19, KGO Refuses to Air Safe-Sex Ads in Daytime. [Google Scholar]

- Hertog J, Fan D. The Impact of Press Coverage on Social Beliefs. Communication Research. 1995 Oct 1;22(5):545–574. doi: 10.1177/009365095022005002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgartner S, Bosk C. The Rise and Fall of Social Problems: A Public Arenas Model. American Journal of Sociology. 1988 Jul 1;94(1):53–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman R. Dallas Morning News. 2003. Jul 12, ‘A Responsibilty to Help’; Bush Looks into the Face of AIDS, Renews Commitment to Fight. [Google Scholar]

- Iyengar S. Is Anyone Responsible?: How Television Frames Political Issues. University of Chicago Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. The HIV/AIDS Epidemic in the United States. Menlo Park, CA: 2001. p. 3029. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Global HIV/AIDS Timeline - Kaiser Family Foundation. 2007 http://www.kff.org/hivaids/timeline/hivtimeline.cfm.

- Levenson J. The Secret Epidemic: The Story of AIDS and Black America. USA: Anchor Books; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McCombs M, Reynolds A. How the News Shapes Our Civic Agenda. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. 2009:1. [Google Scholar]

- More the 500,00 AIDS Cases Reported in the U.S. Los Angeles Times. 1995 Nov 25; [Google Scholar]

- Neergard L. Buffalo News. 1995. Nov 25, Study Tracks AIDS Virsu in Young Men. [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Bu Q, Borah P, Kindig D, Robert S. Message Design Strategies to Raise Public Awareness of Social Determinants of Health and Population Health Disparities. Milbank Quarterly. 2008 Sep 1;86(3):481–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Bigman C, Gonzales A, Gollust S. Communication about Health Disparities in the Mass Media. Journal of Communication. 2013;63(1):8–30. [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Frosch D, Hornik R. Cancer News Coverage and Information Seeking. Journal of Health Communication. 2008;13(2):181–199. doi: 10.1080/10810730701854110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onyango-Obbo C. New York Times. 2003. Jul 12, Poor in Money, Even Poorer in Democracy. [Google Scholar]

- Painter K. USA Today. 1994. Sep 9, Weaker Form of HIV Found. [Google Scholar]

- Research Pays Off in Fight Against AIDS. San Francisco Chronicle. 1998 Oct 12; [Google Scholar]

- Riffe D, Stephen L, Drager M. Sample Size in Content Analysis of Weekly News Magazines. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. 1996;73(3):635–644. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E, Dearing J, Chang S. Journalism Monographs. Columbia, SC: Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication; 1991. Aids in the 1980s: The Agenda-setting Process for a Public Issue; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Roth B. Houston Chronicle. 2003. Jul 12, Bush Applauds Uganda’s President. [Google Scholar]

- Savage D. Supreme Court HIV case tests disability law. 1998 Mar 31; [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M. St Louis Post-Dispatch. 2000. Jun 6, Organizations Work to Educate About, Prevent AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- Shilts R. And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. New York, NY: St. Martins Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker P, Mayfield E. Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. College of Journalism, University of South Carolina; Columbia, SC: 1987. Building a Theory of News Content: A Synthesis of Current Approaches. Journalism Monographs Number 103. http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=ED284240. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Clegg K, Wakefield M, Terry-McElrath Y, Chaloupka F, Flay B, Johnston L, Saba A, Siebel C. Relation Between Newspaper Coverage of Tobacco Issues and Smoking Attitudes and Behaviour Among American Teens. Tobacco Control. 2008 Feb 1;17(1):17–24. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoneburner R, Low-Beer D. Population-Level HIV Declines and Behavioral Risk Avoidance in Uganda. Science. 2004 Apr 30;304(5671):714–718. doi: 10.1126/science.1093166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stryker J, Wray R, Hornik R, Yanovitzky I. Validation of Database Search Terms for Content Analysis: The Case of Cancer News Coverage. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. 2006;83(2):412–430. [Google Scholar]

- Stryker J. Measuring Aggregate Media Exposure: A Construct Validity Test of Indicators of the National News Environment. Communication Methods and Measures. 2008;2(1–2):115–133. doi: 10.1080/19312450802062620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tewksbury D, Scheufele D. News Framing Theory and Research. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. 2009;3:17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath K, Flynt Wallington S, Blake K. Media Processes and Effects. Chapter 21. Los Angeles: Sage; 2009. Media Effects and Population Health. [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T. San Francisco Chronicle. 1999. Jul 9, Disclosure Isn’t the Answer; Condom Code Remains Key to AIDS Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- West M. Seattle Times. 2002. Oct 25, The New Slavery. Human Trafficking for Sex Is the Scourge of Poor Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Yanovitzky I, Stryker J. Mass Media, Social Norms, and Health Promotion Efforts. Communication Research. 2001 Apr 1;28(2):208–239. doi: 10.1177/009365001028002004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]