Abstract

Alzheimer's disease is a neurodegenerative condition believed to be initiated by production of amyloid-beta peptide, which leads to synaptic dysfunction and progressive memory loss. Using a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (3xTg-AD), an 8-arm radial maze was employed to assess spatial working memory. Unexpectedly, the younger (3 month old) 3xTg-AD mice were as impaired in the spatial working memory task as were the older (8 month old) 3xTg-AD mice when compared with age-matched NonTg control animals. Field potential recordings from the CA1 region of slices prepared from the ventral hippocampus were obtained to assess synaptic transmission and capability for synaptic plasticity. At 3 months of age, the NMDA receptor-dependent component of LTP was reduced in 3xTg-AD mice. However, the magnitude of the non-NMDA receptor-dependent component of LTP was concomitantly increased, resulting in a similar amount of total LTP in 3xTg-AD and NonTg mice. At 8 months of age, the NMDA receptor-dependent LTP was again reduced in 3xTg-AD mice, but now the non-NMDA receptor-dependent component was decreased as well, resulting in a significantly reduced total amount of LTP in 3xTg-AD compared with NonTg mice. Both 3 and 8 month old 3xTg-AD mice exhibited reductions in paired-pulse facilitation and NMDA receptor-dependent LTP that coincided with the deficit in spatial working memory. The early presence of this cognitive impairment and the associated alterations in synaptic plasticity demonstrate that the onset of some behavioral and neurophysiological consequences can occur before the detectable presence of plaques and tangles in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Transgenic mouse model, Radial Maze, Hippocampal slice, Amyloid-beta, Synaptic Plasticity

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a disease of aging characterized by progressive memory loss and dementia. It is differentiated from other forms of dementia based on two pathological hallmarks, amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (Hardy, 2006). Amyloid plaques are derived from the aggregation of the amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptide, which is generated through sequential cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein by beta and gamma-secretase (Dyrks, Weidemann, Multhaup, Salbaum, Lemaire, Kang, Muller-Hill, Masters, and Beyreuther, 1988; Glenner and Wong, 1984; Hardy, 2006; Kang, Lemaire, Unterbeck, Salbaum, Masters, Grzeschik, Multhaup, Beyreuther, and Muller-Hill, 1987). During disease progression, the microtubule associated protein tau is subject to extensive post-translational modification including hyper-phosphorylation and acetylation. These modifications are prerequisites to tau aggregation and formation of neurofibrillary tangles (Bancher, Grundke-Iqbal, Iqbal, Fried, Smith, and Wisniewski, 1991; Cohen, Guo, Hurtado, Kwong, Mills, Trojanowski, and Lee, 2011; Grundke-Iqbal, Iqbal, Quinlan, tung, Zaidi, and Wisniewski, 1986; Kosik, Joachim, and Selkoe, 1986; Noble, Olm, Takata, Casey, Mary, Meyerson, Gaynor, LaFrancois, Wang, Kondo, Davies, Burns, Veeranna, Nixon, Dickson, Matsuoka, Ahlijanian, Lau, and Duff, 2003). The exact mechanisms linking these pathologies to memory impairment are unclear, however a growing body of evidence suggests the inability of neurons to maintain calcium homeostasis may be as an underlying factor during the early events of Alzheimer's disease (Berridge, 2011; Yu, Cahng, and Tan, 2009).

One aspect of calcium signaling related to learning and memory involves the cellular mechanisms underlying long-term potentiation (LTP) of synaptic strength. LTP is a model for information storage within the brain, and synaptic plasticity is thought to play an important role in cognitive processes such as learning and memory (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Peng, Zhang, Zhang, Wang, and Ren, 2011). Large, transient increases in intracellular calcium and subsequent activation of calcium-mediated responses lead to the induction and expression of LTP (Citri and Malenka, 2008). At least two different mechanisms of LTP are known to coexist at hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses, N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-dependent LTP (NMDAR LTP) (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993) and a non-NMDA receptor-dependent LTP (non-NMDAR LTP), which is mediated via activation of L-type voltage dependent calcium channels (VDCC) (Grover and Teyler, 1990). Pharmacological evidence indicates that both forms of LTP can contribute to spatial memory as either NMDAR antagonists (Morris, Anderson, Lynch, and Baudry, 1986) or calcium channel antagonists (Maurice, Bayle, and Privat, 1995) can impair spatial learning and memory.

NMDA receptors play an important role in assessments of spatial working memory using the radial arm maze (Bolhuis and Reid, 1992; Butelman, 1989; Ward, Mason, and Abraham, 1990). More recent experiments, in which the NMDAR subunits NR2B and NR2A are specifically blocked by bilateral infusion of antagonists directly into the CA1 region of hippocampus, show a significant reduction in spatial working memory using a T-maze delayed alternation task (Zhang, Liu, Yi, Zhuo, and Li, 2013). NR2A−/− mice show impairments in spatial working memory but not spatial reference memory in the 6-arm radial maze (Niewoehner, Single, Hvalby, Meyer zum Alten Borgloh, Seeburg, Rawlins, Sprengel, and Bannerman, 2007), demonstrating the contribution of specific NMDARs to specific memory functions. Finally, studies in humans have also shown that blockage of NMDARs with ketamine have decreased accuracy on spatial working memory tests (Driesen, McCarthy, Bhagwagar, Bloch, Calhoun, D'Souza, Gueorguieva, He, Lueung, Ramani, Anticevic, Suckow, Morgan, and Krystal, 2013).

A triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease (3xTg-AD) (Oddo, Caccamo, Shepherd, Murphy, Golde, Kayed, Metherate, Mattson, Akbari, and LaFerla, 2003b) has been developed that produces both amyloid plaques and tau tangles (Billings, Oddo, Green, McGaugh, and LaFerla, 2005; Oddo, Caccamo, Kitazawa, Tseng, and LaFerla, 2003a; Oddo et al., 2003b). We have further characterized this AD mouse model using both behavioral (spatial working memory using an 8-arm radial maze) and neurophysiological (extracellular recording from ex vivo slices in the CA1 region of ventral hippocampus) assessments. Our results demonstrate that 3xTg-AD mice have significant impairments in spatial working memory and significant alterations in neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity at both 3 and 8 months of age.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals and euthanasia

All animals used in this study were male mice and consisted of either non-transgenic (NonTg) control mice (B6129SF2/J) from Jackson Laboratories (101045 JAX, Bar Harbour, ME), or Alzheimer's model mice (3xTg-AD) homozygous for three mutant alleles: APPSwe, PsenI, and tauP301L, (B6/129-Psen1tm1Mpm Tg(APPSwe, tauP301L)1Lfa/Mmjax) obtained from the MMRRC (ID 034830-JAX). Mice were housed individually in an AAALAC accredited facility on a 12 hour light/dark timed schedule and had ad libitum access to food (except during behavioral studies, see below) and water during this study. Mice began testing in the radial arm maze at approximately 2.5 and 7.5 months old. After completion of radial arm maze testing, 10 days elapsed before electrophysiological studies commenced to reduce any potential temporary enrichment from the maze environment. Euthanasia of mice occurred under deep anesthesia with halothane followed by decapitation. The University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee approved all animal protocols and experiments.

2.2. Radial arm maze apparatus and animal preparation

Learning and memory assessments were conducted using an 8-arm radial maze (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) as described previously for rats (Babb and Crystal, 2006). This maze consists of a central chamber with 8 equally spaced arms extending outward. The central chamber is equipped with motorized guillotine doors positioned at the interface of the central chamber and arms. Each arm has two sets of photosensors to track movement of the animals into and out of the arms. At the distal end of each arm is a food trough with a 20 mm food dispenser activated by a photosensor to detect mouse head entries. The sides and top of each arm are composed of clear plastic to allow mice to use external visual cues to spatially navigate the maze. A computer in an adjacent room controls the maze events and data collection. Photosensor, food, and door data were collected using MED-PC software 4.0 (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) with a resolution of 10 ms. A video camera was mounted above the maze to visualize the mice during the procedure.

Behavioral assessments in the radial arm maze were measured at either 3 or 8 months of age. Thirteen days prior to the start of behavioral testing, mice were individually housed and a 3 day average of individual animal body weight was determined. Mice were diet restricted to reduce and maintain a body weight of ~87.0% of their free fed body weight for the duration of the behavioral testing. Mice were behaviorally shaped to associate a single head entry with obtaining a single sucrose-flavored food reward (Bio-Serve F0071, Frenchtown, NJ) by allowing each animal free access to 4 of the 8 arms until one food reward from each arm was retrieved. Behavioral shaping was carried out once a day for 4 consecutive days prior to testing.

The maze was cleaned between subjects with 1/1250 diluted Coverage Plus NPD disinfectant (Steris Life Sciences, Mentor, OH) to prevent a previous mouse's scent from interfering with a subsequent mouse's performance. To further prevent a mouse from using scent cues, the entire maze was scent saturated using cotton bedding from the mouse's home cage after cleaning the maze.

2.3. Radial arm maze testing to assess spatial short-term working memory

Spatial short-term working memory was assessed using a standard 8-arm uninterrupted task. Each mouse was placed in the central chamber for a 2 minute acclimation period, after which all 8 doors simultaneously opened allowing free access to all arms for the duration of the testing session (8 arms open, 8 arms baited). Only one food reward is delivered per baited arm, and a revisit to a previously visited food trough is considered an error in spatial short-term working memory. After collecting the last food reward, or after 15 minutes of elapsed time, the session ends and the doors close. For this task, the dependent variable is the number of errors in the first 8 choices. Comparisons are results obtained from the first 2 days and last 2 days of testing. The experiments are performed once a day, at the same time of day for 10 consecutive days. All mice achieved the criterion of no more than 2 errors within the first 10 choices for 3 consecutive days by the 10th day of testing and were continued in the study. Following 10 consecutive days of spatial short-term memory testing, animals proceeded directly to the spatial long-term working memory task containing a retention interval delay.

2.4. Radial arm maze testing to assess spatial long-term working memory

On the following day after completion of spatial short-term working memory testing, spatial long-term working memory was tested using a modified delayed spatial win-shift assay. This is a 2-phase procedure similar to a standard 8-arm task with an interposed delay. This test consisted of a study phase and test phase, conducted in the same day for 10 consecutive days. For the initial study phase, the mouse was placed in the central chamber of the maze for a 2 minute acclimation period. After acclimation, only 4 of the 8 doors simultaneously opened, allowing free access to all open arms for the duration of the testing session (4 arms open, 4 arms baited). The 4 arm sequence during this phase was randomly chosen for each mouse on each day. Only one food reward is delivered per baited arm, and a revisit to a previously visited food trough is considered an error in spatial short-term working memory. After collecting the last food reward, or after 15 minutes of elapsed time, the session ends and the doors close. The mouse was then subjected to a retention interval by returning to the home cage for 3 minutes while the maze is cleaned of any urine or feces that could potentially serve as visitation cues. The mouse was then returned to the central chamber to begin the subsequent test phase. After a 1 minute acclimation period (i.e. 4 minutes total interval), all 8 doors simultaneously opened allowing free access to all open arms for the duration of the testing session. Only arms that were previously closed during the study phase were baited during the test phase (8 arms open, 4 arms baited). Each animal must collect the food reward available at the end of each of the 4 newly baited arms. Only one food reward is delivered per baited arm, and a visit to a previously baited food trough from the study phase was considered an error in spatial long-term working memory (maximum of 4 errors), and a revisit to any food trough during the test phase (whether baited in the training or test phase), was considered an error in spatial short-term working memory. As all animals tested made only negligible short-term working memory errors during the test phase (NonTg, 0.09 errors in 4; 3xTg, 0.13 errors in 4, for both 3 and 8 months, data not shown) both short-term and long-term working memory errors were combined into a total working memory error variable that we report herein as working memory errors. . After collecting the last food reward, or after 15 minutes of elapsed time, the session ends and the doors close. In the test phase, the dependent variable is the number of errors in the first 4 choices. Comparisons are results obtained from the first 2 days and last 2 days of testing.

2.5. Chemicals and reagents

Except where noted, specialty chemicals and antibodies were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

2.6. Immunohistochemistry

Tissue from naive animals not used in behavioral or electrophysiological testing was fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C, embedded with paraffin, and cut into 6-10 μm sections using a Leica RM2155 microtome. Mounted sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated in an ethanol gradient prior to antigen retrieval in boiling 50 mM sodium citrate plus 0.01% Tween 20 for 25 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase activity was inhibited by incubating sections in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes prior to washing with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and blocking with 10 mg/ml bovine serum albumin in PBS overnight. The primary antibodies Beta-Amyloid Monoclonal antibody-10 (BAM-10), pTau-199/202, pTau231 (Acris Antibodies, San Diego, CA), and pTau396 were used at a concentration of 1/250, 1/200, 1/450, and 1/300, respectively. Secondary biotinylated goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit antibodies were used at 1/450 dilution. Slices were incubated with 1/1000 streptavidin-HRP polymer complex (Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA). Slices were washed 3 times for 5 minutes each between antibody and enzyme incubations with 0.02% Tween-20 in PBS. Diaminobenzidine enhanced substrate system was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. After washing off excess diaminobenzidine substrate, slides were counterstained with Gill's No. 2 hematoxylin prior to mounting coverslips. Sections were viewed with a Leica DM6000 B microscope (Wetzlar, Germany) with Hamamatsu ORCA-ER digital camera (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ).

2.7. Amyloid-beta extraction

Aβ extraction was performed as previously described (Hemming, Selkoe, and Farris, 2007). Briefly, ventral hippocampal tissue from behaviorally tested animals taken at the time of sacrifice for electrophysiological testing was obtained and stored at −80°C. The tissue was transferred to a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer containing 4 brain volumes of 6.25 M guanidine HCl in 50 mM Tris buffered saline (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 2 mM 1,10-phenathroline) with 5 μL protease inhibitor cocktail (5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μL/mL pepstatin, 0.1 M PMSF, 0.1 M benzamidine, and 0.5 M ε–aminocaproic acid). After homogenization, samples were transferred to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube and rocked on a platform for 2 hours at room temperature before centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 minutes. The supernatant was collected and stored at −80°C until the ELISA.

2.8. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

ELISAs were performed as previously described (Hemming and Selkoe, 2005; Hemming et al., 2007; Johnson-Wood, Lee, Motter, Gordon, Barbour, Khan, Gordon, Tan, Games, Lieberburg, Schenk, Seubert, and McConlogue, 1997). Briefly, 96-well Costar plates were coated with 4.0 μg/mL BAM-10 for capture of all Aβ isoforms. Aβ 1-42 (Aβ42) levels were detected using a 1/250 dilution (2.5 μg/mL) of rabbit Aβ42 antibody. Wells were subsequently incubated with 100 μL of 1/500 biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody followed by incubation with (1/1000) Avidin D-horseradish peroxidase (Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA). Wells were washed 3 times for 1 minute each with Tris buffered saline plus 0.05% Tween 20 after each incubation step. QuantaBlu substrate kit was used according to the manufacturers protocol (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) and fluorescence of the HRP-substrate reaction was measured on a Biotek Synergy 2 plate reader (EX 320, EM 460) (Winooski, VT).

2.9. Extracellular field recording

Hippocampal slices were prepared from behaviorally tested 3 and 8 month old 3xTg-AD and NonTg control mice 10-17 days after completion of radial arm maze testing. Mice were deeply anesthetized with halothane prior to decapitation. The brain was removed and submerged in ice-cold, oxygenated (95% O2 / 5% CO2) dissection artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing: 120 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 26 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM glucose. The brain was sectioned using a vibratome through the horizontal plane into 400 μm thick slices. The hippocampus was dissected free from slices obtained between the levels of Bregma −4.0 mm to Bregma −2.4 mm. We estimate such slices were from the ventral 35-40% of the hippocampus with respect to the longitudinal axis. We also excluded slices from the extreme 10% of the ventral pole, where it is difficult to clearly distinguish the CA1 pyramidal region from the CA2/3 and subicular regions. Slices were placed in a submersion recording chamber and perfused at approximately 1 ml/min with oxygenated (95% O2 / 5% CO2) standard ACSF containing: 120 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM glucose at room temperature. Slices recovered for 45 minutes at room temperature and an additional 45 minutes at 30°C. A bipolar stimulating electrode (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) was placed within the stratum radiatum of CA1 and an extracellular recording microelectrode (1.0 MΩ tungsten recording microelectrode, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) was positioned in the same layer of CA1. Field excitatory post-synaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded at Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses using a stimulus pulse consisting of a single square wave of 270 μs duration. Data were digitized at 10 kHz, low-pass filtered at 1 kHz, and analyzed with pCLAMP 10.2 software (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA). The initial slope of the population fEPSP was measured by fitting a straight line to a 1 ms window immediately following the fiber volley. Stimulus response curves were obtained at the beginning of each experiment with stimulus pulses delivered at 40, 50, 60, 75, 90, 110, 130, and 150 μA once every 60 s (0.0167 Hz). For baseline recording, the stimulation intensity was adjusted to obtain a fEPSP of approximately 35-40% of the maximum response. Paired-pulse responses were performed at intervals of 50, 100, 200, and 500 ms. The average of five pairs of pulses was obtained for each interval. Synaptic responses for long-term potentiation (LTP) experiments were normalized by dividing all fEPSP slope values by the average of the five responses recorded during the 5 minutes immediately prior to high frequency stimulation (HFS). The HFS protocol used to induce LTP in all experiments consisted of four episodes of 200 Hz/0.5 s stimulus trains (100 pulses) administered at 5 s inter-train intervals. In order to pharmacologically isolate the NMDAR from the non-NMDAR component of LTP, the NMDAR antagonist D,L-AP5 (50 μM) (Tocris Bioscience, Minneapolis, MN) was bath applied for 30 minutes prior to HFS, continued for 5 minutes post-HFS and washed out for the remainder of recording. LTP values for the 1 hour time point were determined by averaging 5 minutes of normalized slope values at 55-60 minutes post-HFS. Reported n-values (x(y)) indicate the number of slices (x) and the number of mice (y) assessed.

2.10. Statistics

Test of significance were performed using either ANOVA, or paired and unpaired t-tests as appropriate.

3. Results

Spatial working memory was evaluated in NonTg and 3xTg-AD mice at 3 and 8 months of age. Electrophysiological recordings of synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity in the ventral hippocampal CA1 region of these same mice were obtained as well as quantification of total Aβ42 levels.

3.1. Spatial memory testing

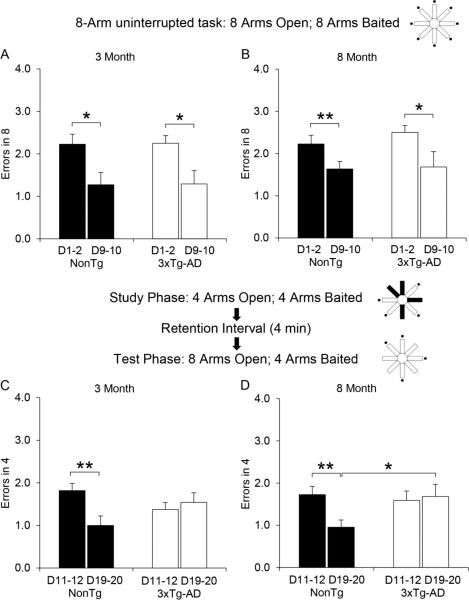

Spatial memory was tested in an 8-arm radial maze utilizing two different protocols. The first tested spatial short-term working memory utilizing an 8-arm uninterrupted task (see schematic diagram of Figure 1). The data shown in Figure 1A & 1B were subjected to a 2 genotype (NonTg versus 3xTg-AD) × 2 training levels (first 2 versus last 2 days) × 2 ages (3 versus 8 months) mixed ANOVA. Within-subjects analysis show there was a significant effect of training (F(1,41)=26.472, p < 0.001). None of the other factors were significant (all p values > 0.2). No significant effects were observed between-subjects. This indicates that both NonTg mice (3 month old, n=11; 8 month old, n=11) and 3xTg-AD mice (3 month old, n=12; 8 month old, n=11) performed similarly during the 10 days of testing, showing significant improvement from initial to terminal days, and demonstrating intact learning acquisition and spatial short-term working memory function.

Figure 1.

Short-term and working memory results in the 8-arm radial maze. The Schematic above each data set illustrates the protocol used for testing. (•) represents baited arms. Blacked out arms represent inaccessible arms. A and B) 8-arm uninterrupted task results for 3xTg-AD and NonTg control mice at 3 and 8 months. A) NonTg (black bars, n=11) and 3xTg-AD (open bars, n=12) mice at 3 months old. B) NonTg (black bars, n=11) and 3xTg-AD (open bars, n=11) at 8 months old. Both the NonTg and 3xTg-AD mice significantly improved their performance as the number of training sessions increased. C and D) Test phase results of the delayed spatial win-shift protocol for 3xTg-AD and NonTg control mice at 3 and 8 months. C) NonTg (black bars, n=11) and 3xTg-AD (open bars, n=12) mice at 3 months old. D) NonTg (black bars, n=11) and 3xTg-AD (open bars, n=11) mice at 8 months old. The NonTg mice significantly improved their performance as the number of training sessions increased. In contrast, the 3xTg-AD mice do not improve at either 3 or 8 months. In addition, there is a significant difference between the performance of the NonTg and the 3xTg-AD mice at days 19-20 at 8 months. Bar graph values represent the mean ± SEM of the first 2 days or the last 2 days of testing. Significance was determined using a mixed ANOVA or independent t-test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

Beginning on day 11, the same mice were evaluated using a delayed spatial win-shift protocol as shown in the middle schematic diagram of Figure 1. In the study phase (4 arms open, 4 arms baited), mice at both 3 and 8 months of age showed no difference between genotypes (data not shown), as this task is a simplified version (4-arm uninterrupted task) of the 8-arm uninterrupted task depicted in the top schematic diagram of Figure 1. Upon completion of the study phase, a 4 minute retention interval occurred before the subsequent test phase (8 arms open, 4 arms baited). Data from the test phase (shown in Figure 1C & D) were subjected to a 2 genotype (NonTg versus 3xTg-AD) × 2 training levels (first 2 versus last 2 days) × 2 ages (3 versus 8 months) mixed ANOVA. Within-subjects analysis indicates there was a significant effect of training (F(1,41)=7.906, p < 0.01) and a significant interaction of training x genotype (F(1,41)=15.195, p < 0.001). The significant interaction within-subjects demonstrates that the NonTg mice benefited from training more than did the 3xTg-AD mice. NonTg mice produced fewer errors as a consequence of training (p < 0.01 at both 3 and 8 months of age), whereas errors for 3xTg-AD mice remained unchanged despite training (p > 0.05 at both 3 and 8 months of age). Notably, the inability of 3xTg-AD mice to improve is not age dependent. The mixed ANOVA showed no significant between-subjects effects, however a follow up between-subjects comparison using an independent t-test evaluating terminal performance (days 19-20) shows NonTg mice make fewer spatial working memory errors than 3xTg-AD mice at 8 months (*p < 0.05; Figure 1D). This trend is also present at 3 months, but is not statistically significant (p = 0.104, Figure 1C). These results demonstrate that the onset of impairment of spatial working memory performance can be observed as early as 3 months of age in 3xTg-AD mice, but only after increasing memory load requirements using a rigorous delayed spatial win-shift protocol that involves long-term working memory mechanisms.

3.2. Characterization of 3xTg-AD pathology and progression

To verify the pathological state of our 3xTg-AD mice, immunohistochemical analysis at 3 and 8 months was performed (Supplemental Figure S1). Using a nonisoform specific Aβ antibody (BAM-10), intraneuronal Aβ localization was detected in CA1 pyramidal neurons at both 3 and 8 months in 3xTg-AD mice, but not in NonTg mice. BAM-10 localization also revealed small disperse plaque deposits in the hippocampus of 8 month old 3xTg-AD mice, but not in NonTg or 3 month old 3xTg-AD mice. To determine relative levels of tau hyper-phosphorylation, three antibodies that recognize site-specific phosphorylation of tau at Ser199/202, Thr231, and Ser396 were utilized. No detectable phospho-tau within CA1 pyramidal neurons of NonTg or 3 month 3xTg-AD mice was found. However, in 8 month 3xTg-AD mice, phospho-tau was readily detectable in CA1 pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus with all antibodies.

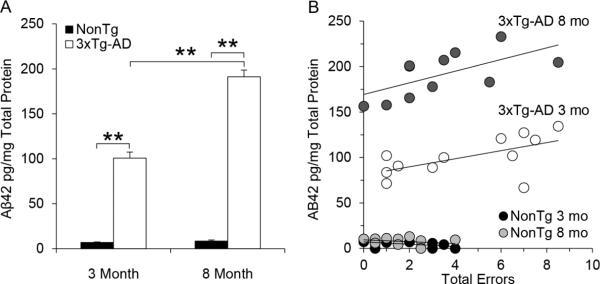

To test whether Aβ correlated with behavioral measurements of spatial working memory, Aβ from ventral hippocampal brain tissue was extracted from the same mice that were tested in the radial arm maze. Since soluble Aβ (40 or 42), as well as total Aβ40, has been shown to remain relatively stable with age in 3xTg-AD mice (Billings et al., 2005; Oddo et al., 2003a), ELISAs were used to measure total Aβ42 since it is the most abundant species in 3xTg-AD mice, and because of its more aggressive nature during disease progression (Hardy, 2006; Oddo et al., 2003a; Oddo et al., 2003b). The total Aβ42 data (shown in Figure 2A) were subjected to a 2 genotype (NonTg versus 3xTg-AD) × 2 ages (3 versus 8 months) ANOVA. There was a significant effect of age (F(1,37)=68.4, p < 0.001), genotype (F(1,37)=616.6, p < 0.001), and interaction of age × genotype (F(1,37)=63.9, p < 0.001). As can be seen in Figure 2A, the interaction confirms the visual impression that Aβ42 accumulation significantly increased as a function of age for the 3xTg-AD mice but not for the NonTg mice, which is consistent with the immunohistochemistry. At both 3 and 8 months of age, 3xTg-AD mice show a significant correlation between total Aβ42 and spatial working memory as measured by the number of errors that occurred in the test phase before visiting the last baited arm (Figure 2B) (3 months: r2 = 0.354; Pearson correlation coefficient 0.6, p < 0.05; 8 months: r2 = 0.404, Pearson correlation coefficient 0.8, p < 0.01). The results suggest that within a given age cohort, increased levels of total Aβ42 correlated with decreased cognitive performance. Additional comparisons between total LTP, NMDAR LTP, or non-NMDAR LTP and maze performance or Aβ42 levels were also conducted but did not result in any significant correlations (Data not shown).

Figure 2.

Aβ42 quantification and relation to maze performance in 3xTg-AD and NonTg control mice. A) Comparison of total Aβ42 levels in ventral hippocampal tissue at 3 and 8 months of age for 3xTg-AD (open bars, 3 months n=12, 8 months n=11) and NonTg (black bars, 3 months n=8, 8 months n=10) mice. Bar graph values represent the mean ± SEM, significance was determined using ANOVA (** p < 0.01). B) Scatter plot showing the relationship between total Aβ42 and total errors in the test phase at 3 and 8 months in 3xTg-AD (open/dark grey circles) and NonTg (black/light grey circles) mice. Significance was determined using ANOVA. Both 3 (p < 0.05) and 8 (p < 0.01) month 3xTg-AD mice show a significant correlation between total Aβ42 and total errors.

3.3. Electrophysiology

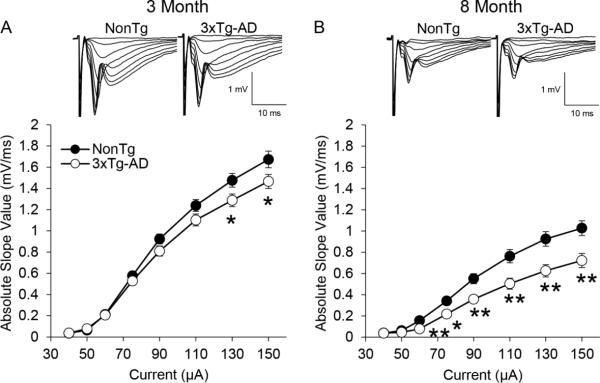

To determine if neurophysiological differences exist between 3xTg-AD and NonTg mice, fEPSPs from the CA1 stratum radiatum in ventral hippocampal slices were recorded. Stimulus response curves were generated for 3xTg-AD and NonTg mice at both 3 and 8 months of age to evaluate the functional range of synaptic activity (Figure 3). At 3 months of age, baseline fEPSPs for both groups were largely similar. The 3xTg-AD mice (n=54(12)) exhibited significantly lower fEPSP slope values than NonTg mice (n=56(11)) at the highest stimulus intensities (Figure 3A, 130 and 150 μA, p < 0.05). At 8 months of age, fEPSP slopes at intensities greater than 60 μA were significantly reduced (p < 0.01) in 3xTg-AD mice (n=39(11)) compared to NonTg mice (n=47(11)) (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Field Excitatory Post Synaptic Potentials (fEPSP) recorded from the CA1 region of ventral hippocampus in 3xTg-AD and NonTg control mice. A) Stimulus response curves for 3xTg-AD (open circles, n=54(12)) and NonTg (black circles, n=56(11)) control mice at 3 months of age. Input intensities are 40, 50, 60, 75, 90, 110, 130, and 150 μA. The averaged fEPSP sweeps are shown above the stimulus response curves. B) Same as panel A except at 8 months of age for 3xTg-AD (n=39(11)) and NonTg (n=47(11)) control mice. The values represent the mean ± SEM from n slices. Significance between genotypes was determined using an independent t-test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

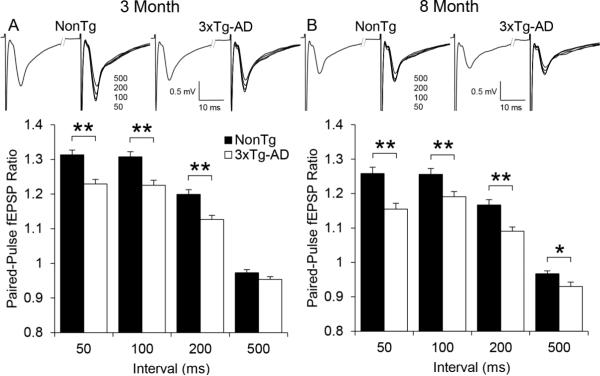

A paired-pulse stimulus protocol was utilized to evaluate short-term synaptic plasticity. At 3 months of age, both 3xTg-AD and NonTg mice showed paired-pulse facilitation at all intervals tested except 500 ms (Figure 4A). The 3xTg-AD mice (n=54(12)) showed significantly less facilitation (p < 0.01) than NonTg mice (n=58(11)). Paired-pulse facilitation in 8 month old mice showed similar results, as the 3xTg-AD mice (n=36(11)) showed significantly less facilitation (p < 0.01) than NonTg mice (n=42(11)) at stimulus intervals of 50,100, and 200 ms (Figure 4B). In addition, a modest but significant difference (p < 0.05) in the 500 ms paired-pulse response was also present between 3xTg-AD and NonTg mice at 8 months of age.

Figure 4.

Paired-pulse Field Excitatory Post-Synaptic Potentials (fEPSP) recorded from the CA1 region of ventral hippocampus in 3xTg-AD and NonTg control mice. A) Paired-pulse ratios at 50, 100, 200, and 500 ms intervals in 3xTg-AD (open bars, n=54(12)) and NonTg (black bars, n=58(11)) control mice at 3 months of age. The averaged fEPSP sweeps are shown above the paired-pulse ratios. B) Same as panel A except at 8 months of age for 3xTg-AD (n=36(11)) and NonTg (n=42(11)) control mice. Bar graph values represent the mean ± SEM from n slices. Significance between genotypes was determined using an independent t-test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

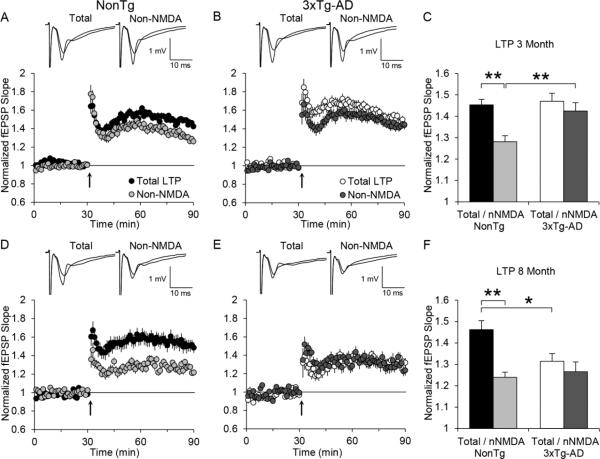

Long-term synaptic plasticity was induced using a multiple train stimulus induction protocol previously shown to elicit a compound potentiation consisting of both NMDAR and non-NMDAR components of LTP (Grover and Teyler, 1990). The non-NMDAR component of LTP was measured utilizing the selective NMDAR antagonist D,L-AP5 to block the NMDAR component of LTP. LTP data were subjected to a 2 genotype (NonTg versus 3xTg-AD) x 2 treatment group (No drug (total LTP) versus D,L-AP5 (non-NMDAR LTP)) ANOVA for multiple group comparisons at each age. The ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype (F(1,94)=5.879, p < 0.05) and treatment (F(1,94)=10.926, p < 0.01) at 3 months. While there was no statistical interaction of genotype with treatment, it was close to significance (F(1,94)=3.730, p= 0.056). At 8 months of age, there was a significant effect of treatment (F(1,71)=13.366, p < 0.01) and a significant interaction of genotype with treatment (F(1,71)=5.533, p < 0.05). ANOVAs were followed by Tukey's post-hoc analysis.

At 3 months of age, there was no significant difference in total LTP between 3xTg-AD mice (47 ± 4%, n=23(12)) and NonTg mice (45 ± 2%, n=25(10)) (Figure 5A-C). However, in the presence of D,L-AP5 (50 μM), the potentiated fEPSP slope value was significantly reduced in NonTg mice (28 ± 3%, n=25(10)) but not significantly altered in 3xTg-AD mice (42 ± 4%, n=25(12)) as compared with their respective total LTP values (Figure 5C). In addition, the non-NMDAR component of LTP was significantly greater in 3xTg-AD mice than in the NonTg mice (p < 0.01, Figure 5C). At 8 months, total LTP was significantly reduced (p < 0.05) in 3xTg-AD mice (31 ± 4%, n=15(11)) compared to NonTg mice (46 ± 4%, n=19(9)) (Figure 5D-F). These results agree with a previous report describing the timing of impairment in total LTP magnitude in the 3xTg-AD mice (Oddo et al., 2003b). In the presence of D,L-AP5 (50 μM), the potentiated fEPSP slope value was again significantly reduced (p < 0.01) in NonTg mice (24 ± 2%, n=23(11)), and was not significantly altered in 3xTg-AD mice (27 ± 5%, n=18(11)) as compared to their respective total LTP values (Figure 5F). Note that the significant difference in the magnitude of the non-NMDAR component of LTP observed between the two genotypes at 3 months is not evident at 8 months of age (Figure 5C & F). Thus, the significant decrease in total LTP at 8 months of age in the 3xTg-AD mice is most likely due to the decrease in the non-NMDAR component of LTP.

Figure 5.

Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) of Field Excitatory Post-Synaptic Potentials (fEPSP) recorded from the CA1 region of ventral hippocampus in 3xTg-AD and NonTg control mice. A) Summary plot of normalized fEPSP slope values in 3 month old NonTg mice for total LTP (black circle, (n=25(10)) and bath applied D,L-AP5 (50 μM) representing non-NMDAR LTP (light grey circle, n=25(10)), before and after high frequency stimulation (HFS) (4 x 200Hz/0.5 s at 5 s intervals) indicated by the arrow at 30 minutes. The averaged fEPSP sweeps before and after HFS for total LTP and non-NMDAR LTP are shown above the plot. B) Same as panel A except in 3 month old 3xTg-AD mice for total LTP (open circle, (n=23(12)) and non-NMDAR LTP (dark grey circle, n=25(12)). C) Summary quantification of total LTP and non-NMDAR LTP for NonTg and 3xTg-AD mice at 1 hr post-HFS. D, E, & F) Same as A, B, & C above except at 8 months of age. For NonTg (total LTP, n=17(9); non-NMDAR LTP, n=23(11)) control mice, and 3xTg-AD (total LTP, n=15(11); non-NMDAR LTP, n=18(11)) mice. Bar graph values represent the mean ± SEM from n slices. Significance was determined using a 2 way ANOVA (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

Separate cohorts of behaviorally naïve NonTg and 3xTg-AD mice provided a tissue source for additional ex vivo fEPSP recordings, including assessments of baseline NMDAR-mediated responses and their sensitivity to antagonism with D,L-AP5. No significant differences were observed in these measures between the two genotypes (Supplemental Figure S2). Thus under these conditions, NMDARs are physiologically and pharmacologically equivalent in NonTg and 3xTg-AD mice at 3 months of age in the CA1 stratum radiatum layer.

4. Discussion

In this study, behavioral deficiencies in spatial working memory were found in the 3xTg-AD mouse model using the 8-arm radial maze. At both 3 and 8 months of age, these mice failed to demonstrate improvements in spatial working memory performance in the test phase of a delayed spatial win-shift assay, compared to their NonTg counterparts (Figure 1C & D). This is in contrast to results from the 8-arm uninterrupted task, which assesses spatial short-term working memory and yielded similar improvement across session days in both 3xTg-AD and NonTg mice (Figure 1A & B). A significant decrease in paired-pulse facilitation was consistently observed in the 3xTg-AD mice at both 3 and 8 months of age (Figure 4), and although the total magnitude of LTP in the CA1 region of the hippocampus was equivalent for the NonTg and 3xTg-AD mice at 3 months, the contribution of non-NMDAR LTP was significantly greater in 3xTg-AD than NonTg mice (Figure 5). The impairment in spatial working memory in the test phase of our delayed spatial win-shift assay was concurrent with alterations in both short-term presynaptic plasticity and the NMDAR-dependent component of LTP in 3xTg-AD mice at both 3 and 8 months. In addition, impairments in spatial working memory of individual 3xTg-AD mice were positively correlated with total Aβ42 levels in both of these age groups (Figure 2).

The results from the 8-arm uninterrupted task demonstrate that both NonTg and 3xTg-AD mice have intact spatial learning and navigation (i.e., they show equivalent levels of learning the rules required to complete the radial maze task, equivalent perception of spatial cues, equivalent levels of motivation and locomotor control). Due to the continuous nature of this task the working memory load is low, making the procedure dependent upon immediately accessible information from short-term memory (Baddeley, 2010; Floresco, Seamans, and Phillips, 1997). In order to specifically examine spatial working memory involving a long-term component, the mice were tested in a 2-phase delayed spatial win-shift assay, which included a retention interval delay of 4 minutes. The incorporation of a time delay forces retention of trial-unique spatial information (i.e., the mice must remember which arms were visited in phase 1 in order to successfully complete phase 2), which increases working memory load beyond the capability of short-term memory. This allowed discrimination in performance between NonTg and 3xTg-AD mice, as the NonTg mice showed improvement across sessions but the 3xTg-AD mice did not. The test phase results suggest that 3xTg-AD mice have impaired spatial working memory (i.e., memory for daily item-specific locations) when long-term working memory mechanisms are required. This is likely a profound impairment specifically for this type of spatial working memory, since the 8-arm uninterrupted task results indicated intact acquisition of the maze rules (making a general impairment in learning capability unlikely).

Assessments of spatial learning and memory depend upon intact hippocampal function (Becker, Walker, and Olton, 1980; Floresco et al., 1997; Jarrard, 1993; Olton and Papas, 1979). From analysis of anatomical, genetic, and functional data from primarily animal models, it was proposed that the dorsal and ventral sectors of the hippocampus are distinct entities, both anatomically and functionally (Fanselow and Dong, 2010). However, there is some controversy to ascribing particular functions solely to the dorsal or ventral hippocampus (reviewed in (Poppenk, Evensmoen, Moscovitch, and Nadel)). More recently, a primary role for the ventral sector of the hippocampus in spatial working memory has been reported (O'Neill, Gordon, and Sigurdsson, 2013), as well as a report of vH involvement in goal-directed spatial learning (Ruediger, Spirig, Donato, and Caroni, 2012). Both of these observations are consistent with the presence of a direct anatomical connection between the ventral hippocampus and the medial prefrontal cortex (Degenetais, Thierry, Glowinski, and Gioanni, 2003; Tripathi, Schenker, Spedding, and Jay, 2015). Finally, with respect to the possible relevance of the vH for being involved in early AD deficits, evidence indicates that early loss of hippocampal tissue in Alzheimer's disease patients is more prominent in the anterior (ventral) sector (Frisoni, Ganzola, Canu, Rub, Pizzini, Alessandrini, Zoccatelli, Beltramello, Caltagirone, and Thompson, 2008; Qiu, Fennema-Notestine, Dale, Miller, and I, 2009). Therefore, in the current studies we have obtained electrophysiological recordings in hippocampal slices taken from the ventral third of the hippocampus to determine if synaptic function is altered in the 3xTg-AD mice when behavioral impairments were evident in a spatial working memory task dependent upon intact ventral hippocampal function.

Basal synaptic transmission is largely similar between genotypes at 3 months of age, but at 8 months a reduction in the fEPSP responses were observed in both NonTg and 3xTg-AD mice, with the 3xTg-AD mice being significantly less responsive than the NonTg mice (Figure 3). This reduction in NonTg mice at 8 months is most likely due to a normal age related decline of synaptic AMPAR activity, possibly related to reduced postsynaptic AMPAR activity (Barnes, Rao, and Orr, 2000; Kumar and Foster, 2007). In the 8 month old 3xTg-AD mice, this age related decline in synaptic transmission may be exaggerated due to Aβ-induced AMPAR trafficking (Hsieh, Boehm, Sato, Iwatsubo, Tomita, Sisodia, and Malinow, 2006) or changes in calcium homeostasis (Chakroborty, Kim, Schneider, Jacobson, Molgo, and Stutzmann, 2012). Previous investigations of short-term synaptic plasticity have reported that measurements of paired-pulse facilitation in the CA1 region of both 1 and 6 month old 3xTg-AD mice are not significantly different from NonTg mice (Chakroborty, Goussakov, Miller, and Stutzmann, 2009; Oddo et al., 2003b). In contrast, our results demonstrate the paired-pulse facilitation ratio is significantly decreased in 3xTg-AD mice at both 3 and 8 months of age (Figure 4). Other work has shown dysregulation of calcium homeostasis in 3xTg-AD mice resulting in higher resting calcium levels as early as 6 weeks of age (Stutzmann, Smith, Caccamo, Oddo, LaFerla, and Parker, 2006). Alterations in presynaptic calcium levels would be expected to affect paired-pulse facilitation (Zucker and Regehr, 2002), however the specific underlying mechanism at work here is uncertain. Our observation of a reduction in paired-pulse ratio in ventral hippocampal slices from 3xTg-AD mice may be an early neurophysiological indicator of a functional synaptic abnormality that is consistent with the dysregulation of calcium homeostasis and excitatory neurotransmission (Paula-Lima, Brito-Moreira, and Ferreira, 2013).

In addition to evaluating short-term synaptic plasticity, we also investigated a form of long-term synaptic plasticity, long-term potentiation. At least two forms of LTP are known to coexist at CA3-CA1 synapses, NMDAR LTP (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993) and non-NMDAR LTP (Grover and Teyler, 1990), both of which have been shown to be involved in spatial learning and memory (Borroni, Fichtenholtz, Woodside, and Teyler, 2000; Davis, Butcher, and Morris, 1992). Our results demonstrate that NMDAR LTP was significantly reduced in 3xTg-AD mice at both 3 and 8 months of age, coinciding with the spatial working memory failure in the test phase of our delayed spatial win-shift assay. Interestingly, while the NMDAR component of LTP was reduced in 3xTg-AD mice, the non-NMDAR component of LTP increased. As a result, the combination of NMDAR LTP with non-NMDAR LTP yielded a total LTP that was not significantly different between 3xTg-AD and NonTg mice at 3 months of age. At 8 months however, 3xTg-AD mice showed a significant reduction in total LTP compared to NonTg mice. These results (i.e. no difference at 3 months, reduction at 8 months) are consistent with previous work (Oddo et al., 2003b).

The importance of NMDAR function in spatial working memory has been demonstrated in numerous studies. NMDARs that are pharmacologically blocked prior to behavioral tests of working memory (Bolhuis and Reid, 1992; Borroni et al., 2000; Butelman, 1989; Enomoto and Floresco, 2009; Ward et al., 1990), or knock-out mice with non-functional NMDARs due to missing NR2A or NR2BΔFb subunits (Bannerman, Niewoehner, Lyon, Romberg, Schmitt, Taylor, Sanderson, Cottam, Sprengel, Seeburg, Kohr, and Rawlins, 2008; von Engelhardt, Doganci, Jensen, Hvalby, Gongrich, Taylor, Barkus, Sanderson, Rawlins, Seeburg, Bannerman, and Monyer, 2008), show profound deficits in spatial working memory. Pharmacological blockade of NMDARs in wild type animals assessed for short-term and working memory performance in spatial tasks similar to our own have impairments in working memory, but not short-term memory (Enomoto and Floresco, 2009). Together these results suggest a specific role for NMDAR LTP in spatial working memory (Bannerman et al., 2008; Bolhuis and Reid, 1992; Boric, Munoz, Gallagher, and Kirkwood, 2008; Borroni et al., 2000; Butelman, 1989; Enomoto and Floresco, 2009; Rosenzweig and Barnes, 2003; Shankar, Teyler, and Robbins, 1998; von Engelhardt et al., 2008; Ward et al., 1990). In light of these findings, the reduction in NMDAR LTP we observed in 3xTg-AD mice at both 3 and 8 months of age appears likely to play a causative role in the spatial working memory impairment we have observed in the current study. This impairment did not appear to be related to a deficiency in NMDAR activity, as measurements of NMDAR-mediated fEPSPs in behaviorally naïve animals demonstrated a normal level of synaptic NMDAR response in 3 month old 3xTg-AD mice (Supplemental Figure S2). Others have reported reduced NMDAR currents in CA1 pyramidal cells of either PS1 (Wang, Greieg, Yu, and Mattson, 2009) or APP (Tozzi, Sclip, Tantucci, de Iure, Ghiglieri, Costa, Di Filippo, Borsello, and Calabresi, 2015) mutant mice and reported reductions in LTP. Interestingly, in an APP/PS1 mutant mouse the loss of NMDAR-mediated cGMP production occurred without an associated loss of NMDAR density, demonstrating that a change in receptor expression is not required for altered signal transduction (Duszczyk, Kuszczyk, Guridi, Lazarewicz, and Sadowski, 2012).

In unimpaired aged rats performing a reference memory task, the loss of NMDAR LTP was accompanied by a compensatory increase in non-NMDAR LTP (Boric et al., 2008). In the current study, 3xTg-AD mice had increased non-NMDAR LTP at 3 months, an age they were thought to be cognitively unimpaired. This could account for previous findings which demonstrated that 3xTg-AD mice were unimpaired at 2 months in the MWM (Billings et al., 2005), as the MWM is primarily a test of spatial reference memory as opposed to spatial working memory (Morris, 1984; Wenk, 2004). Furthermore, our studies indicated the majority of LTP in 3xTg-AD mice is non-NMDAR LTP at both 3 and 8 months of age. Thus the reduction in total LTP at 8 months is possibly due to reduced activation of VDCCs, as the majority of non-NMDAR LTP in wild type animals is VDCC dependent (Grover and Teyler, 1990). Interestingly, it has been reported that APP/PS1 mutant mice have reduced somatic Na+ currents resulting in reduced VDCC activation (Brown, Chin, Leiser, Pangalos, and Randall, 2011), this potentially could result in the decreased non-NMDAR LTP we observed in our 8 month old 3xTg-AD animals. Other possibilities for mechanisms involved in non-NMDAR LTP include synaptic plasticity mediated by Aβ and metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling (Li, Hong, Shepardson, Walsh, Shankar, and Selkoe, 2009; Wang, Walsh, Rowan, Selkoe, and Anwyl, 2004), and NR2B containing NMDARs (Li, Jin, Koeglsperger, Shepardson, Shankar, and Selkoe, 2011).

The 3xTg-AD mice used in our study are homozygous for three mutant transgenes: APPSwe, Psen1, and tauP301, with expression driven by the Thy1.2 promoter. In contrast to exogenously applied Aβ42, neurons in 3xTg-AD mice are continuously exposed to Aβ42 from a very young age and potential compensatory mechanisms to synaptic dysfunction could therefore develop as the mouse ages. The increased non-NMDAR LTP observed in the 3 month old mice of the current study may be an example of such compensation. It is important to note that such effects are likely not observed in acute slice studies. For example, the effects of acutely applied exogenous Aβ42 to ex vivo slices are probably manifested via alterations of NMDAR LTP, but without the associated increase in non-NMDAR LTP.

The effect of Aβ42 on synaptic loss and its consequences for memory functions are complex. The increase in Aβ42 levels at 3 and 8 months in our mice coincides with the behavioral and electrophysiological alterations we have also observed at these ages, and a comparison of Aβ42 levels with the total number of errors accrued in the test phase from individual mice show there is a significant relationship between total Aβ42 levels and spatial working memory performance. At 8 months, total Aβ42 was significantly higher than at 3 months, but without concomitantly increased detriment to maze performance. Given that soluble Aβ42 levels remain constant over a period of 2-6 months in this 3xTg-AD model (Billings et al., 2005), the continued increase in total Aβ42 measured at 8 months is likely due to its accumulation within insoluble depositions. This may explain why an increase in total Aβ42 levels at 8 months does not result in further decrement of maze performance if the age-associated accumulation of insoluble Aβ42 is extraneous. In contrast, a correlation between individual Aβ42 burden and spatial reference memory performance in the MWM was identified only at a time when amyloid plaque was present in 2xTg-AD (APP/PS1) mice (Puolivali, Wang, Heikkinen, Heikkila, Tapiola, van Groen, and Tanila, 2002). In human AD patients, the total amount of cortical Aβ42 was positively correlated with mild clinical dementia prior to tau pathology (Naslund, Haroutunian, Moha, Davis, Davies, Greengard, and Buxbaum, 2000). Transgenic mice that produce high levels of Aβ42 but do not form amyloid plaques or tau pathology show significant synaptic loss and behavioral impairments similar to mice that do (Koistinaho, Ort, Cimadevilla, Vondrous, Cordell, Koistinaho, Bures, and Higgins, 2001). These observations add further support to the suggestion that soluble Aβ42 may be important for early synaptic deficits associated with the disease state (Mucke, Masliah, Yu, Mallory, Rockenstein, Tatsuno, Hu, Kholodenko, Johnson-Wood, and McConlogue, 2000). However, the total Aβ load may also be important, depending upon the behavioral endpoint being assessed. A multimetric statistical analysis of four transgenic mouse lines differing in Aβ deposition was assessed by a large battery of behavioral tests (Leighty, Nilsson, Potter, Costa, Low, Bales, Paul, and Arendash). The results of this analysis showed impaired acquisition and memory retention in the MWM were correlated with the “diffuse” and “compact” Aβ deposition in the brain, respectively. While relationships between Aβ42 levels and spatial working memory performance were evident in the current study, correlations between Aβ42 and other measures of electrophysiology were not found. For example, LTP values were not correlated with spatial working memory performance in the current study, although other forms of memory, such as spatial reference memory, have been shown to correlate to LTP (Boric et al., 2008).

In the current series of studies, we have characterized early behavioral and electrophysiological alterations, and total Aβ42 in 3xTg-AD model mice. Our findings of behavioral impairment in spatial working memory at 3 months of age is at least 3 months before the observation of plaque formation in the hippocampus of these mice (Billings et al., 2005; Oddo et al., 2003b). Our findings of altered synaptic plasticity, such as decreased paired-pulse facilitation and decreased NMDAR LTP in the ventral hippocampus, coincided with significant impairments in radial arm maze performance. The linear relationship between Aβ42 levels and spatial working memory errors demonstrates that individuals producing more Aβ42 suffered greater memory impairment. These observations in 3xTg-AD mice show that physiological and behavioral deficiencies are present at an age previously referred to by many investigators as presymptomatic in these animals. Our additional finding that 3xTg-AD mice also exhibited increased non-NMDAR LTP at 3 months of age is intriguing, and warrants further investigation into this potentially adaptive mechanism during the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. Such observations regarding the early functional and behavioral consequences of Aβ42 in a mouse model of AD provides new insight at the mechanistic level for potentially understanding the early cognitive impairments observed in Alzheimer's disease patients.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-Spatial working memory was impaired in 3 & 8 month old 3xTg-AD mice.

-Short-term synaptic plasticity (paired-pulse facilitation) was reduced in 3xTg-AD mice.

-The NMDA receptor-mediated component of LTP was reduced in 3xTg-AD mice.

-The alterations in synaptic plasticity coincide with a deficit in spatial working memory.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by NIH R01 N5046451 (www.ninds.nih.gov) to R. Furukawa and M. Fechheimer. Disclosure statement: There are no conflicts of interest. All animal protocols and experiments were approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Animal Care Committee.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Babb SJ, Crystal JD. Episodic-like memory in the rat. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:1317–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A. Working memory. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:R136–R140. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancher C, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Fried VA, Smith HT, Wisniewski HM. Abnormal phosphorylation of tau precedes ubiquitination in neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer disease. Brain Res. 1991;539:11–18. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90681-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Niewoehner B, Lyon L, Romberg C, Schmitt WB, Taylor A, Sanderson DJ, Cottam J, Sprengel R, Seeburg PH, Kohr G, Rawlins JN. NMDA receptor subunit NR2A is required for rapidly acquired spatial working memory but not incremental spatial reference memory. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:3623–3630. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3639-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes CA, Rao G, Orr G. Age-related decrease in the Schaffer collateral-evoked EPSP in awake, freely behaving rats. Neural Plast. 2000;7:167–178. doi: 10.1155/NP.2000.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JT, Walker JA, Olton DS. Neuroanatomical bases of spatial memory. Brain Res. 1980;200:307–320. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90922-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Calcium signalling and Alzheimer's disease. Neurochem. Res. 2011;36:1149–1156. doi: 10.1007/s11064-010-0371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billings LM, Oddo S, Green KN, McGaugh JL, LaFerla FM. Intraneuronal Ab causes the onset of early Alzheimer's disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron. 2005;45:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis JJ, Reid IC. Effects of intraventricular infusion of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist AP5 on spatial memory of rate in a radial arm maze. Behav. Brain Res. 1992;47:151–157. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boric K, Munoz P, Gallagher M, Kirkwood A. Potential adaptive function of altered long-term potentiation mechanisms in aging hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8034–8039. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2036-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borroni AM, Fichtenholtz H, Woodside BL, Teyler TJ. Role of voltage-dependent calcium channel long-term potentiation (LTP) and NMDA LTP in spatial memory. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:9272–9276. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09272.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JT, Chin J, Leiser SC, Pangalos MN, Randall AD. Altered intrinsic neuronal excitability and reduced Na+ currents in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2011;2109;32:e2101–2114. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butelman ER. A novel NMDA antagonist, MK-801, impairs performance in a hippocampal-dependent spatial learning task. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 1989;34:13–16. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(89)90345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakroborty S, Goussakov I, Miller MB, Stutzmann GE. Deviant ryanodine receptor-mediated calcium release resets synaptic homeostasis in presymptomatic 3xTg-AD mice. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9458–9470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2047-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakroborty S, Kim J, Schneider C, Jacobson C, Molgo J, Stutzmann GE. Early presynaptic and postsynaptic calcium signaling abnormalities mask underlying synaptic depression in presymptomatic Alzheimer's disease mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8341–8353. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0936-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citri A, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity: multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:18–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen TJ, Guo JL, Hurtado DE, Kwong LK, Mills IP, Trojanowski J, Lee VM. The acetylation of tau inhibits its function and promotes pathological tau aggregation. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:252. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Butcher SP, Morris RG. The NMDA receptor antagonist D-2- amino-5-phophonopentanoate (D-AP5) impairs spatial learning and LTP in vivo at intracerebral concentraitons comparable to those that block LTP in vitro. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:21–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-01-00021.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenetais E, Thierry AM, Glowinski J, Gioanni Y. Synaptic influence of hippocampus on pyramidal cells of the rat prefrontal cortex: an in vivo intracellular recording study. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:782–792. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driesen NR, McCarthy G, Bhagwagar Z, Bloch MH, Calhoun VD, D'Souza DC, Gueorguieva R, He G, Lueung HC, Ramani R, Anticevic A, Suckow RF, Morgan PT, Krystal JH. The impact of NMDA receptor blockade on human working memory-related prefrontal function and connectivity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:2613–2622. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duszczyk M, Kuszczyk M, Guridi M, Lazarewicz JW, Sadowski MJ. in vivo hippocampal microdialysis reveals impairment of NMDA receptor-cGMP signaling in APP(SW) and APP(SW)/PS1(L166P) Alzheimer's transgenic mice. Neurochem. Int. 2012;61:976–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrks T, Weidemann A, Multhaup G, Salbaum JM, Lemaire HG, Kang J, Muller-Hill B, Masters CL, Beyreuther K. Identification, transmembrane orientation and biogenesis of the amyloid A4 precursor of Alzheimer's disease. EMBO J. 1988;7:949–957. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02900.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto T, Floresco SB. Disruptions in spatial working memory, but not short-term memory, induced by repeated ketamine exposure. Prog. Neuropsychopharmcol Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;33:668–675. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanselow MS, Dong HW. Are the dorsal and ventral hippocampus functionally distinct structures? Neuron. 2010;65:7–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Seamans JK, Phillips AG. Selective roles for hippocampal, prefrontal cortical, and ventral striatal circuits in radial-arm maze tasks with or without a delay. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:1880–1890. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01880.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisoni GB, Ganzola R, Canu E, Rub U, Pizzini FB, Alessandrini F, Zoccatelli G, Beltramello A, Caltagirone C, Thompson PM. Mapping local hippocampal changes in Alzheimer's disease and normal ageing with MRI at 3 Tesla. Brain Pathol. 2008;131:3266–3276. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer's disease: initital report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984;120:885–890. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover LM, Teyler TJ. Two components of long-term potentitation induced by different patterns of afferent activation. Nature. 1990;347:477–479. doi: 10.1038/347477a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Quinlan M, tung YC, Zaidi MS, Wisniewski HM. Microtubule-associated protein tau. A component of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 1986;261:6084–6089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J. A hundred years of Alzheimer's disease research. Neuron. 2006;52:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemming ML, Selkoe D. Amyloid beta-protein is degraded by cellular angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and elevated by an ACE inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:37644–37650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508460200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemming ML, Selkoe D, Farris W. Effects of prolonged angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor treatment on amyloid beta-protein metabolism in mouse models of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007;26:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H, Boehm J, Sato C, Iwatsubo T, Tomita T, Sisodia S, Malinow R. AMPAR removal underlies Abeta-induced synaptic depression and dendritic spine loss. Neuron. 2006;52:831–843. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrard LE. On the role of the hippocampus in learning and memory in the rat. Behav. Neural Biol. 1993;60:9–26. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(93)90664-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Wood K, Lee M, Motter R, Gordon G, Barbour R, Khan K, Gordon M, Tan H, Games D, Lieberburg I, Schenk D, Seubert P, McConlogue L. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Aβ42 deposition in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:1550–1555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Muller-Hill B. The precursor of Alzheimer's disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987;325:733–736. doi: 10.1038/325733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koistinaho M, Ort M, Cimadevilla JM, Vondrous R, Cordell B, Koistinaho J, Bures J, Higgins LS. Specific spatial learning deficitis become severe with age in beta-amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice that harbor diffuse beta-amyloid deposits but do not form plaques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:14675–14680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261562998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosik KS, Joachim CL, Selkoe D. Microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) is a major antigenic component of paired helical filaments in Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1986;83:4044–4048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Foster TC. Neurophysiology of Old Neurons and Synapses. In: Riddle DR, editor. Brain Aging: Models, Methods, and Mechanisms. Boca Raton (FL): 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighty RE, Nilsson LNG, Potter H, Costa DA, Low MA, Bales KR, Paul SM, Arendash GW. Use of mulimetric statistical analysis to characterize and discriminate between the performance of four Alzheimer's transgenic mouse lines differing in Ab deposition. Behav. Brain Res. 2004;153:107–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Hong S, Shepardson NE, Walsh DM, Shankar GM, Selkoe D. Soluble oligomers of amyloid Beta protein facilitate hippocampal long-term depression by disrupting neuronal glutamate uptake. Neuron. 2009;62:788–801. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Jin M, Koeglsperger T, Shepardson NE, Shankar GM, Selkoe DJ. Soluble Abeta oligomers inhibit long-term potentiation through a mechanism involving excessive activation of extrasynaptic NR2B-containing NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6627–6638. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0203-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice T, Bayle J, Privat A. Learning impairment following acute adminstration of the calcium channel antogonist nimodipine in mice. Behav. Pharmacol. 1995;6:167–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RG. Developments of a water-maze procedure for studying spatial learning in the rat. J. Neurosci. Meth. 1984;11:47–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RG, Anderson E, Lynch GS, Baudry M. Selective impairment of learning and blockade of long-term potentiation by an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, AP5. Nature. 1986;319:774–776. doi: 10.1038/319774a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucke L, Masliah E, Yu G-Q, Mallory M, Rockenstein EM, Tatsuno G, Hu K, Kholodenko D, Johnson-Wood K, McConlogue L. High-level neuronal expression of Abeta 1-42 in wild type human amyloid protein precursor transgenic mice: synaptotoxicity without plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4050–4058. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04050.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naslund J, Haroutunian V, Moha R, Davis KL, Davies P, Greengard P, Buxbaum JD. Correlation between elevated levels of amyloid b-peptide in the brain and cognitive decline. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2000;283:1571–1577. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.12.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niewoehner B, Single FN, Hvalby OJ, V., Meyer zum Alten Borgloh S, Seeburg PH, Rawlins JN, Sprengel R, Bannerman DM. Impaired spatial working memory but spared spatial reference memory following functional loss of NMDA receptors in the dentate gyrus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;25:837–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05312.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble W, Olm V, Takata K, Casey E, Mary O, Meyerson J, Gaynor K, LaFrancois J, Wang L, Kondo T, Davies P, Burns M, Veeranna, Nixon R, Dickson D, Matsuoka Y, Ahlijanian M, Lau LF, Duff K. Cdk5 is a key factor in tau aggregation and tangle formation in vivo. Neuron. 2003;38:555–565. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill PK, Gordon JA, Sigurdsson T. Theta oscillations in the medial prefrontal cortex are modulated by spatial working memory and synchronize with the hippocampus through its ventral subregion. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:1411–1424. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2378-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Kitazawa M, Tseng BP, LaFerla FM. Amyloid deposition precedes tangle formation in a triple transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003a;24:1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S, Caccamo A, Shepherd JD, Murphy MP, Golde TE, Kayed R, Metherate R, Mattson MP, Akbari Y, LaFerla FM. Triple- transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease with plaques and tangles: intracellular Abeta and synaptic dysfunction. Neuron. 2003b;39:409–421. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olton DS, Papas BC. Spatial memory and hippocampal function. Neuropsychologia. 1979;17:668–682. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(79)90042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paula-Lima AC, Brito-Moreira J, Ferreira ST. Deregulation of excitatory neurotransmission underlying synapse failure in Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 2013;126:191–2002. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng S, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Wang H, Ren B. Glutamate receptors and signal transduction in learning and memory. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011;38:453–460. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppenk J, Evensmoen HR, Moscovitch M, Nadel L. Long-axis specialization of the human hippocampus. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013;17:230–240. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puolivali J, Wang JZ, Heikkinen T, Heikkila M, Tapiola T, van Groen T, Tanila H. Hippocampal abeta 42 levels correlate with spatial memory deficit in APP and PS1 double trangenic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;9:339–347. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu A, Fennema-Notestine C, Dale AM, Miller MI, I A. s. D. N. Regional shape abnormalities in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. NeuroImage. 2009;45:656–661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig ES, Barnes CA. Impact of aging on hippocampal function: plasticity, network dynamics, and cognition. Prog. Neurobiol. 2003;69:143–179. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruediger S, Spirig D, Donato F, Caroni P. Goal-oriented searching mediated by ventral hippocampus early in trial-and-error learning. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1563–1571. doi: 10.1038/nn.3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar S, Teyler TJ, Robbins N. Aging differentially alters forms of long- term potentiation in rat hippocampal area CA1. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:334–341. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.1.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzmann GE, Smith I, Caccamo A, Oddo S, LaFerla FM, Parker I. Enhanced rynaodine receptor recruitment contributes to Ca2+ disruptions in young, adult, and ages Alzheimer's disease mice. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:5180–5189. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0739-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozzi A, Sclip A, Tantucci M, de Iure A, Ghiglieri V, Costa C, Di Filippo M, Borsello T, Calabresi P. Region- and age-dependent reductions of hippocampal long-term potentiation and NMDA to AMA ratio in a genetic model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi A, Schenker E, Spedding M, Jay TM. The hippocampal to prefrontal cortex circuit in mice: a promising electrophysiological signature in models for psychiatric disorders. Brain Struct Funct. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Engelhardt J, Doganci B, Jensen V, Hvalby O, Gongrich C, Taylor A, Barkus C, Sanderson DJ, Rawlins JN, Seeburg PH, Bannerman DM, Monyer H. Contribution of hippocampal and extra-hippocampal NR2B containing NMDA receptors to performance on spatial learning tasks. Neuron. 2008;60:846–860. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Walsh DM, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ, Anwyl R. Block of long- term potentiation by naturally secreted and synthetic amyloid beta-peptide in hippocampal slices is mediated via activation of the kinases c-Jun N-terminal kinase, cyclin-dependent kinase 5, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase as well as metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3370–3378. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1633-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Greieg NH, Yu Q-S, Mattson MP. Presenilin-1 mutation impairs cholinergic modulation of synaptic plasticity and suppresses NMDA currents in hippocampus slices. Neurobiol. Aging. 2009;30:1061–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward L, Mason SE, Abraham WC. Effects of the NMDA antagonists CPP and MK-801 on radial arm maze performancein rats. Pharm. Biochem. Behav. 1990;35:785–790. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90359-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk GL. Assessment of spatial memory using the radial arm maze and Morris water maze. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2004;8 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0805as26. unit 8.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JT, Cahng RC, Tan L. Calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer's disease: from mechanisms to therapeutic opportunitites. Prog. Neurobiol. 2009;89:240–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XH, Liu SS, Yi F, Zhuo M, Li BM. Delay-dependent impairment of spatial working memory with inhibition of NR2B-containing NMDA receptors in hippocampal CA1 region of rats. Mol. Brain. 2013;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS, Regehr WG. Short-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2002;64:355–405. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.092501.114547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.