Abstract

The prevalence of kidney stones is increasing worldwide. Various etiologies may in part explain this observation including increased prevalence of diabetes, obesity and the metabolic syndrome, increased dietary protein and salt content, and decreased dietary dairy products. We hypothesize an additional and novel potential contributor to increasing kidney stone prevalence: migration to urban settings, or urbanization, and resultant exposure of the population to the higher temperatures of urban heat islands (UHIs). Both urbanization and exposure to UHIs are worldwide, continuous trends. Because the difference in temperature between rural and urban settings is greater than the increase in temperature caused by global warming, the potential effect of urbanization on stone prevalence may be of greater magnitude. However, demonstration of a convincing link between urbanization and kidney stones is confounded by many variables simultaneously affected by migration to cities, such as changes in occupation, income, and diet. No data have yet been published supporting this proposed association. We explore the plausibility and limitations of this possible etiology of increasing kidney stone prevalence.

Introduction

Kidney stones are highly prevalent in the world’s population. More than 10% of some male populations and 5–10% of some female populations will be affected, and evidence demonstrates that the prevalence of kidney stones is increasing in the United States and possibly worldwide as well [1,2]. The cause of this increase in kidney stone prevalence is not certain but has been linked to increasing prevalence of diabetes, obesity and the metabolic syndrome, increased dietary protein and salt content, and decreased dietary calcium intake. The relative contribution of any of these etiologic variables has been difficult to quantitate, if not to prove.

The United Nations has called urbanization, the increase in the size of urban populations, “the greatest human migration in history”. This urbanization has occurred on a worldwide basis. The magnitude of this phenomenon would seem to be a worthy subject for study as it has the potential to change many variables related to health, including those relevant to kidney stone formation. None of the many potential effects of urbanization has yet been studied using appropriate databases to elucidate any effects it may have on kidney stone incidence or prevalence (or many other health-related disorders).

We propose here a plausible mechanism to link urbanization to kidney stone formation. Urbanization exposes much of Earth’s population to an increased ambient temperature due to the existence of urban heat islands (UHIs). We hypothesize that migration from cooler, rural environments, to warmer, urban environments may account in part for the increasing prevalence of kidney stones. While global warming has been proposed as a stimulus to kidney stone incidence, the potential effect of urbanization on ambient temperature far exceeds that accounted for by global warming per se, although global warming does contribute to the difference in temperature observed in rural and urban environments.

Our hypothesis is not easily supported or studied. First, there are currently few data demonstrating incidence or prevalence of kidney stones in urban versus rural populations; we review two studies and note that neither considers temperature variation. Second, urbanization is potentially associated with many changes in kidney stone risk factors, such as changes in diet, activity and occupation, that would make dissection of ambient temperature from among the relevant and confounding variables difficult. Third, exposure to heat is modified by many variables such as race, income and age that could affect stone formation as well. However we think the worldwide scale on which urbanization is occurring, and the already evident impact of urban heat islands (UHI) on health, make this hypothesis worth proposing.

Urbanization

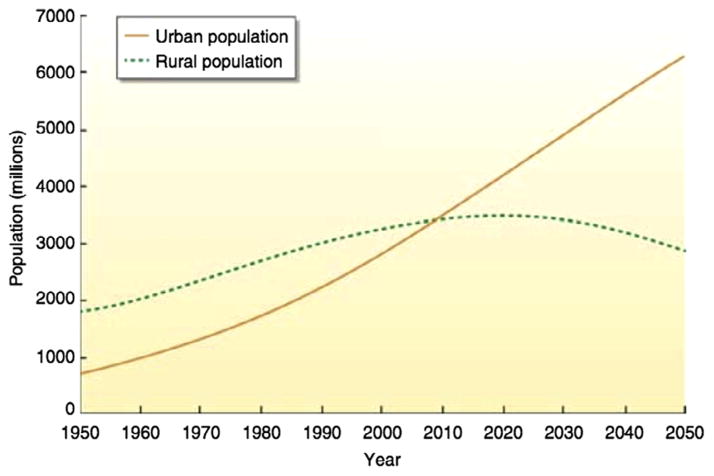

The United Nations Population Division predicts that in the next 40 years the world’s population will increase by 2.3 billion people, to 9.3 billion by 2050 [3]. The majority of the increase will take place in urban areas which will not only incorporate most of the increase in population attributed to reproduction, but will simultaneously receive the migrating rural population. This migration to urban areas and increasing urban population size is called urbanization [4]. In 2008, for the first time, more than half the world’s population (3.3 billion people at that time) lived in urban rather than rural areas (Fig. 1) [3].

Fig. 1.

Urban and rural global population growth over time and predictions based on population trends [4]. The proportion of the population of Earth living in urban settings now surpasses that living in rural settings. The latter is projected to decrease.

Urbanization has transformed the global landscape by replacing open land and vegetation with buildings and other non-green infrastructure. These developments are responsible for the formation of UHIs and an important source of urban climate change [5].

Urban heat islands

UHIs are urban areas with elevated temperatures as compared to their rural surroundings. During the day, the annual mean air temperature in a city can be 1–3 °C warmer than the rural surroundings. This difference becomes greater in the evening, when city temperatures can be as much as 12 °C warmer than rural surroundings, which typically become cooler at night [6].

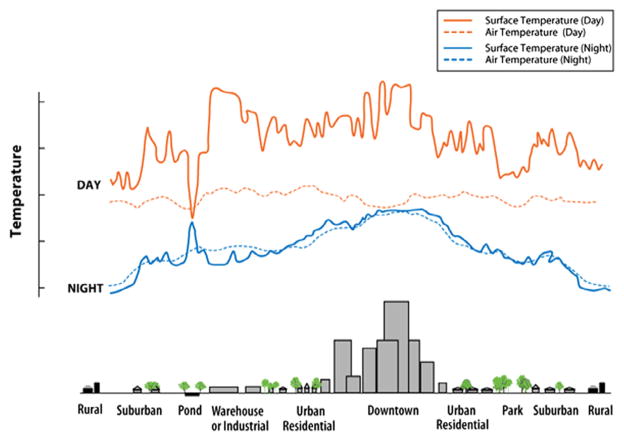

There are two main components of UHIs: surface heat islands and atmospheric heat islands [5]. Surface heat islands are areas with increased daytime heat on exposed urban surfaces, like roofs and pavements. Atmospheric heat islands are the areas with higher mean air temperature in the layer of air from the ground to below the tops of trees or roofs [5]. Surface heat islands affect atmospheric heat islands, as heat from surface islands increases the atmospheric air temperature. As Fig. 2 demonstrates, both components of urban heat islands cause temperature to be higher during the day and at night as compared to rural areas.

Fig. 2.

Surface and air temperature fluctuations in urban and rural areas [5]. Both surface and air temperatures are higher in dense urban areas as compared to rural counterparts. Surface temperature rises higher during the daytime and both rise during the night. The temperatures displayed above do not represent absolute temperature values or any one particular measured heat island. Reprinted with permission.

In rural landscapes, naturally vegetated surfaces promote evapotranspiration [7]. As water is absorbed and released by plant roots, soil, and leaves (transpiration), it absorbs solar or atmospheric heat that converts it from a liquid to a gas (evaporation). These processes together lower atmospheric and surface temperature. However, urban landscapes are dominated by less reflective surfaces such as buildings and pavement that cannot absorb water. Water then mostly becomes runoff, and the diminished evapotranspiration contributes to the higher surface and atmospheric air temperatures of UHIs [5].

Furthermore, urban building materials absorb more heat than rural surroundings, which, after absorbing heat, can also release it because of the water content of soil and vegetation. “Urban geometry”, such as the presence of obstructing nearby buildings, also impedes release of stored heat in the evenings in urban settings. Additionally, many building materials have higher heat capacities than soil or sand, and thus store more solar energy [8].

Urbanization is the cause of UHIs as population size and urban temperature rise simultaneously. UHI intensity, the difference in maximum temperature between urban and rural areas [9,10], is strongly correlated with the log of population. Evidence of the effect requires population growth surpassing as few as 1000 people [6].

Ambient temperature, UHIs and health

Elevated temperatures have directly affected human health by inducing heat stroke, cardiovascular disease, and asthma, and are likely to have many other effects [11]. In the past 30 years, excessive heat has caused over 8000 deaths in the United States alone [12]. There is a significant ongoing effort by many public health organizations to monitor the adverse health effects of global warming [13]. An important example of observational data demonstrating the health effects of UHIs, as distinct from global warming, is a study showing that areas in Shanghai with more hot days and longer heat waves than nearby suburban areas have significantly higher heat-related mortality [14]. People who live in areas in the United States whose zipcodes correlate with less greenspace had significantly greater cardiovascular mortality during extreme heat events [15].

Heat and kidney stones

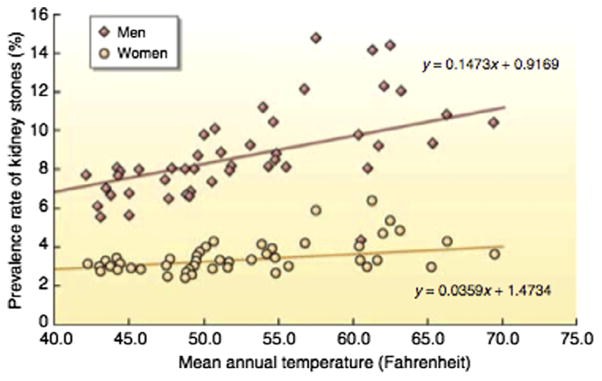

Ambient temperature is associated with an increased prevalence of kidney stones [16,17]. The mechanism of heightened temperatures leading to kidney stones begins with stimulation of heat-induced perspiration. Serum osmolality increases, which stimulates the release of vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone) from the posterior pituitary. Vasopressin increases urinary osmolality and decreases urine volume, increasing the concentration of relatively insoluble salts such as calcium oxalate, the most common constituent of kidney stones, which then precipitate in the kidneys [18]. The effect of temperature has a greater effect on stone prevalence in males than in females for reasons that have not been studied (Fig. 3) [16]. A variety of observations (but not all) also support a relationship between season and stone incidence with more stones in warmer months [19]. An important corollary to the relationship of greater heat-related urinary concentration to stone formation is that increasing fluid intake is associated with fewer stones. Observational studies, randomized controlled trials and a meta-analysis support that effect [20–22]. Ample physiology then supports the association of greater ambient temperature with lower urine volume, which should be associated with more kidney stones.

Fig. 3.

Scatter plot of kidney stone prevalence in the USA, by gender, as compared to the mean annual temperature of the states [16]. Kidney stone prevalence increases for both men and women as mean ambient temperature increases. Men have higher prevalence of stones than women, and a greater effect of heat on stone prevalence. Reprinted with permission.

Stone prevalence in the southeastern United States is nearly 50% higher than in the northeast where mean annual temperature is on average 8 °C lower [17,23]. A recent projection suggests that as global warming progresses, the “kidney stone belt,” or highest risk areas for stones, will expand northward [23]. Every 1 °C temperature increase will cause a 4.2% increase in stone risk [23]. By 2050, the mean increase in warming of 2.4 °C across the US would cause 2.25 million new stones and require an additional $1.3 billion in treatment costs.

While this projection of the effect of a 1 °C increase in temperature appears to be consequential, the Earth’s mean atmospheric temperature has increased by only 0.74 °C over the last 100 years [24]. Kidney stone prevalence is documented to have increased over at least the last 30 years [1]. This period corresponds to a time of significant urbanization (Fig. 1) which would lead to a greater exposure of the world’s population to hotter ambient temperature than that attributable to global warming.

A new hypothesis

We first posit, as many investigators have demonstrated, that urbanization, a worldwide phenomenon of massive scale, has been, and will continue to be associated with many effects on health. The potential role of urbanization in promoting kidney stone formation among other disorders is worth exploring. We also suggest that one possible explanation linking urbanization to observed increases in kidney stone prevalence is the increased ambient temperature due to urbanization and UHIs to expose Earth’s populations to significantly warmer temperatures. Urbanization has brought people from cooler, rural settings to increasingly warmer, urban settings. The change in temperature of 1–3 °C during the daytime and up to 12 °C at night due to UHIs is of a greater magnitude than that of global warming thus far.

Evaluation

We searched Pubmed.gov for urbanization and {kidney stones or urolithiasis or nephrolithiasis}. We found one paper describing relevant results. We were aware of a second paper that considered stone incidence in rural and urban settings. Neither study was prospective and neither took into account regional differences in temperature. In a prospective study of children under age 18 years in Taiwan, the key independent variable was the urbanization level of residence [25]. Urbanization was graded at 8 levels based on a scoring system developed by Taiwan’s Institute of Occupational Safety and Health which included: population density (person/km2), percentage of people with at least college education, percentage of people greater than 65 years old, the percentage of agricultural workers and the number of physicians per 100,000 population. The rate of new diagnosis of stones was 0.39% in the most metropolitan regions compared with 0.52% in the most rural settings (P < 0.004). The authors did not speculate regarding an explanation for this result. Ambient temperature and exposure to it were not considered among the relevant variables.

In a second paper the incidence of stones was examined in a state-wide database of emergency department visits in South Carolina, United States [26]. Definitions of “rural” and “urban” counties were not provided. There was a significant increase in the incidence of kidney stones in children between 1996 and 2007. However, there was no statistical difference in incidence of stones between rural and urban counties of residence when the study period began (7.9 versus 8.2 per 100,000 children, respectively). However in 2007 the rate was statistically greater at 26.7 in rural counties compared with 17.4 per 100,000 children in urban counties. There were no adjustments made for possible confounding variables and no explanation was proffered regarding the result.

In summary, 2 papers attempted to make observations regarding the incidence or prevalence of stones in rural versus urban settings. Neither was designed to examine the variables we propose to be relevant here and neither could adjust for a variety of potential confounders. Both studies showed slightly higher rates in more rural populations.

Limitations

The major limitation of our hypothesis is that we currently lack any prospective data from well-designed studies to support it. An ideal database to confirm that migration from rural to urban settings accounts for increased kidney stone incidence and prevalence would prospectively track kidney stone formation and other outcomes, as people experience urbanization. Epidemiologic techniques currently being applied to study the expected health effects of climate change and heat events have recently been reviewed [11]. Most related studies have concentrated on acute events rather than more chronic effects such as heat-induced kidney stones. Few, if any, studies will produce longitudinal observations of migrating populations.

In addition, there are many confounders that make such an analysis daunting. If appropriate databases demonstrated that migration to urban settings was associated with more stones, the potential responsible variables would be plentiful. People migrating from rural to urban settings, or living in one versus the other, experience changes in income, diet, activity and occupation that may be strong modifiers of risk for kidney stones. In addition, access to medical care and imaging modalities and intensity of medical surveillance likely differ and affect the reporting of outcomes. Any demonstration of increased stone prevalence could then be attributed to more detection rather than a true increase in prevalence.

On the other hand, as people move to cities they may spend more time in air-conditioned, cooler office spaces and less time outdoors, perhaps mitigating the effect of UHIs. Urban settings may provide more reliable access to potable water in some communities. UHIs have greater effects at night than during the day and time-averaged exposure to higher temperatures may be difficult to gauge. More widespread availability of air-conditioning (both at work or at home, and in the developing world) may make such observations even more difficult. For instance, Fig. 3 shows that despite a good linear correlation, the extreme hottest US states did not have the highest kidney stone prevalence, perhaps suggesting that heat exposure was modified by other factors [16,17]. Vulnerability to heat exposure and heat-related events varies with income, age, race, socioeconomic status, all of which may be variables relevant to kidney stone incidence and prevalence as well [27].

Surprisingly, as we have reviewed, the available cross-sectional data linking heat to stones are not completely persuasive [16]. In some studies lower urine volume and higher urinary concentration did not correlate with hotter climate or occupation [18]. Regional dietary differences and racial and other genetic differences may also be important confounders, with appropriate adjustment difficult. In one large, prospective study of men, age- and nutrient-adjusted incidence of stones was higher in the northeastern United States, while the prevalence of stones was, as expected, higher in the southeast [28].

One alternative hypothesis, the attribution of kidney stones to ultraviolet light-induced increases in intradermal vitamin D synthesis at lower (and warmer) latitudes, thereby increasing intestinal absorption of calcium and urinary calcium excretion, has not been borne out by observational data [16]. Despite these limitations, the epidemiologic observations are supportive of a role for heat to cause increasing stone incidence and prevalence, while the biology of urinary concentration is indisputable. The fact of urbanization and the existence of UHIs are also not in doubt.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we think it likely, but cannot prove, that urbanization is responsible for increased kidney stone prevalence. The trends of urbanization and development of UHIs are inexorable. The nations of the world are attempting to develop and implement strategies to mitigate the grave consequences of global warming. However effective or ineffective such strategies may be, they will not address progressive urbanization. Exposure to UHIs seems certain to increase and rising kidney stone incidence and prevalence will likely result. Urban design adaptation strategies may address and may be able to counteract rising temperatures due to UHIs, and offset a portion of anticipated greenhouse gas-driven warming as well [29]. The implications for heat-related disorders in general and kidney stones specifically may be enormous.

Acknowledgments

D.S.G. gratefully acknowledges support of the Rare Kidney Stone Consortium (U54KD083908), a part of NIH Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), funded by the NIDDK and the NIH Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Contributions of the authors

Both authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Disclosures

No external funding sources contributed to this study.

References

- 1.Scales CD, Smith AC, Hanley JM, Saigal CS. Prevalence of kidney stones in the United States. Eur Urol. 2012;62(1):160–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romero V, Akpinar H, Assimos DG. Kidney stones: a global picture of prevalence, incidence, and associated risk factors. Rev Urol. 2010;12(2–3):e86–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World urbanization prospects: the 2009 revision. New York: United Nations; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vlahov D, Galea S. Urbanization, urbanicity, and health. J Urban Health. 2002;79(4 suppl 1):S1–S12. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.suppl_1.S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reducing urban heat islands: compendium of strategies. Washington, D.C: EPA’s Office of Atmospheric Programs; 2008. Urban heat island basics. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oke TR. The energetic basis of the urban heat island. QJ Roy Meteorol Soc. 1982;108:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung M, Reichstein M, Ciais P, Seneviratne SI, Sheffield J, Goulden ML, et al. Recent decline in the global land evapotranspiration trend due to limited moisture supply. Nature. 2010;467(7318):951–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christen A, Vogt R. Energy and radiation balance of a central European city. Int J Climatol. 2004;24:1395–421. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karl TR, Diaz HF, Kukla G. Urbanization: its detection and effect in the United States climate. J Clim. 1988;1:1099–123. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tokairin T, Sofyan A, Kitada T. Numerical study on temperature variation in the Jakarta area due to urbanization. The seventh international conference on urban climate; Yokohama, Japan: Toyohashi University of Technology, Institute of Technology; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Neill MS, Ebi KL. Temperature extremes and health: impacts of climate variability and change in the United States. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51 (1):13–25. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318173e122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CDC. Extreme heat: a prevention guide to promote your personal health and safety center for disease control and prevention. Atlanta: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haines A, Patz JA. Health effects of climate change. JAMA. 2004;291(1):99–103. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan J, Zheng Y, Tang X, Guo C, Li L, Song G, et al. The urban heat island and its impact on heat waves and human health in Shanghai. Int J Biometeorol. 2010;54(1):75–84. doi: 10.1007/s00484-009-0256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gronlund CJ, Berrocal VJ, White-Newsome JL, Conlon KC, O’Neill MS. Vulnerability to extreme heat by socio-demographic characteristics and area green space among the elderly in Michigan, 1990–2007. Environ Res. 2015;136:449–61. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fakheri RJ, Goldfarb DS. Ambient temperature as a contributor to kidney stone formation: implications of global warming. Kidney Int. 2011;79(11):1178–85. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soucie JM, Thun MJ, Coates RJ, McClellan W, Austin H. Demographic and geographic variability of kidney stones in the United States. Kidney Int. 1994;46(3):893–9. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borghi L, Meschi T, Amato F, Novarini A, Romanelli A, Cigala F. Hot occupation and nephrolithiasis. J Urol. 1993;150(6):1757–60. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35887-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boscolo-Berto R, Dal MF, Abate A, Arandjelovic G, Tosato F, Bassi P. Do weather conditions influence the onset of renal colic? A novel approach to analysis. Urol Int. 2008;80(1):19–25. doi: 10.1159/000111724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curhan GC, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ. A prospective study of dietary calcium and other nutrients and the risk of symptomatic kidney stones. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(12):833–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199303253281203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borghi L, Meschi T, Amato F, Briganti A, Novarini A, Giannini A. Urinary volume, water and recurrences in idiopathic calcium nephrolithiasis: a 5-year randomized prospective study. J Urol. 1996;155(3):839–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheungpasitporn W, Rossetti S, Friend K, Erickson SB, Lieske JC. Treatment effect, adherence, and safety of high fluid intake for the prevention of incident and recurrent kidney stones: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephrol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s40620-015-0210-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brikowski TH, Lotan Y, Pearle MS. Climate-related increase in the prevalence of urolithiasis in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(28):9841–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709652105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pachauri RK, Reisinger A, editors. Contribution of working groups I, II, and III to the fourth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Intergov Panel Clim Change; Geneva, Switzerland: 2007. Climate change 2007: synthesis report, summary for policymaker. core writing team. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang WY, Chen YF, Chen SC, Lee YJ, Lan CF, Huang KH. Pediatric urolithiasis in Taiwan: a nationwide study, 1997–2006. Urology. 2012;79(6):1355–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sas DJ, Hulsey TC, Shatat IF, Orak JK. Increasing incidence of kidney stones in children evaluated in the emergency department. J Pediatr. 2010;157 (1):132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gronlund CJ. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in heat-related health effects and their mechanisms: a review. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2014;1 (3):165–73. doi: 10.1007/s40471-014-0014-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curhan GC, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ. Regional variation in nephrolithiasis incidence and prevalence among United States men. J Urol. 1994;151(4):838–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Georgescu M, Morefield PE, Bierwagen BG, Weaver CP. Urban adaptation can roll back warming of emerging megapolitan regions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(8):2909–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322280111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]