Abstract

Background

Previous research has linked polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) exposure to poor birth outcomes and altered thyroid hormone levels.

Objectives

We examined whether maternal PBDE serum levels were associated with infant birth weight (g), head circumference (cm), birth length (cm), and birth weight percentile for gestational age. We explored the potential for a mediating role of thyroid hormone levels.

Methods

During 2008–2010, we recruited 140 pregnant women in their third trimester as part of a larger clinical obstetrics study known as Healthy Pregnancy, Healthy Baby. Blood samples were collected during a routine pre-natal clinic visit. Serum was analyzed for PBDEs, phenolic metabolites, and thyroid hormones. Birth outcome information was abstracted from medical records.

Results

In unadjusted models, a two-fold increase in maternal BDE 153 was associated with an average decrease in head circumference of 0.32 cm (95% CI: −0.53, −0.12); however, this association was attenuated after control for maternal risk factors. BDE 47 and 99 were similarly negatively associated but with 95% confidence intervals crossing the null. Associations were unchanged in the presence of thyroid hormones.

Conclusions

Our data suggest a potential deleterious association between maternal PBDE levels and infant head circumference; however, confirmatory studies are needed in larger sample sizes. A mediating role of thyroid hormones was not apparent.

Keywords: Birth outcomes, Birth weight, Head circumference, Infant length, Polybrominated diphenyl ethers, Thyroid hormone

1. Introduction

Polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) are a class of chemicals that have historically been used to decrease the flammability of consumer products. As additives, these chemicals are not chemically bound to consumer products and ultimately leach out over time, contaminating the environment. Due to their high volume use over the past several decades, PBDEs are now ubiquitous contaminants in most environments, especially in the United States (Hale et al., 2003; Law et al., 2006a; de Wit et al., 2006). In addition, due to their physicochemical properties, PBDEs are persistent in the environment, and several PBDEs are highly bioaccumulative. In the United States, it is estimated that more than 97% of the general population has PBDEs circulating in their bloodstream (Sjodin et al., 2008), and infants and toddlers have higher concentrations than adults (Rose et al., 2010; Stapleton et al., 2012a). Commercial production of two of the three PBDE mixtures ceased in 2005 in the United States following a voluntary phase-out by manufacturers (Tullo, 2003), and the third commercial mixture was phased-out in 2013 (EU-Commission, 2008). Despite these phase-outs, products containing PBDEs are still found in homes; (Stapleton et al., 2011a; Stapleton et al., 2012b) therefore, exposure among the general population is likely to continue for some time.

Fetuses are believed to be particularly vulnerable to the effects of environmental pollutants because of their relatively immature organs, which are in sensitive developmental stages, and because they have less well developed detoxification systems (Barr et al., 2007). PBDEs are known to cross the placenta, and maternal exposures can therefore lead to fetal exposure as evidenced by measurements of PBDEs in fetal cord serum (Foster et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2009; Vizcaino et al., 2011). Over the past few years, human health studies have found associations between PBDE body burdens and adverse health outcomes including reduced fecundity in women, failed embryo implantation (Johnson et al., 2012), reductions in infant birth weight and length, decreased neurodevelopmental scores in children, and changes in circulating thyroid hormone levels in pregnant women (Herbstman et al., 2010; Chevrier et al., 2010; Roze et al., 2009; Harley et al., 2010; Stapleton et al., 2011b; Turyk et al., 2008). PBDEs in maternal breast milk were also associated with the incidence of cryptorchidism in newborn boys (Main et al., 2007). In a Taiwanese cohort study of 20 women, Chao et al. (2007) found that increased PBDEs in breast milk were related to decreased birth weight and birth length, chest circumference, and Quetelet’s index of infants, following adjustment for maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), and parity (Chao et al., 2007). In an e-waste recycling region in China, significant differences in PBDEs in umbilical cord blood were found between samples from normal births and those with adverse birth outcomes including premature delivery, low birth weight, and still birth, whereby median PBDE levels in the adverse birth outcome group were significantly higher than those in the normal birth group (Wu et al., 2010). While some studies have found associations between PBDEs and birth outcomes, other studies have not (Tan et al., 2009). In addition to small sample numbers, multiple chemical exposures, both to other contaminants and different mixtures of PBDEs, could explain some of the differences across these studies.

Due to these observations in human epidemiological studies, and animal exposure studies demonstrating effects both on thyroid hormone regulation and neurodevelopment, researchers have started questioning whether the observed associations between PBDE body burdens and adverse birth outcomes and neurodevelopment may be mediated through thyroid hormone dysregulation (Dingemans et al., 2011). A number of animal exposure studies using different animal models have demonstrated that exposure to PBDEs can result in reductions in the circulating levels of thyroxine (T4), and sometimes triiodothyronine (T3) (Zhou et al., 2002; Fernie et al., 2005; Law et al., 2006b). However, in human epidemiological studies, one using the same cohort reported on here and two using additional cohorts, both positive and negative associations between serum PBDEs and T4 have been observed (Stapleton et al., 2011b; Turyk et al., 2008; Vuong et al., 2015; Zota et al., 2011). One study found positive associations between PBDEs and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) among pregnant women (Chevrier et al., 2010). The specific pathways by which PBDEs alter circulating levels of T4 and T3 are currently unclear (Harley et al., 2011), and may vary depending on the age, sex, and developmental stage of the exposed individual. An in vitro study using human liver tissues demonstrated that PBDE metabolites (OH-BDEs) can inhibit thyroid deiodinase (dio) activity (Butt et al., 2011), which may influence the circulating levels of thyroid hormones. Another study further demonstrated that OH-BDEs can competitively bind to serum proteins that transport thyroid hormones (Meerts et al., 2000), while another study found that PBDEs can lead to upregulation of hepatic enzymes that metabolize and clear thyroid hormones from the body (Szabo et al., 2009). Regardless of the mechanism and direction of change, alterations in thyroid hormone regulation during pregnancy can impact developing fetuses (Hulbert, 2000). Therefore, examining the potential for interaction of PBDEs and thyroid hormone levels on birth outcomes is important.

In the current study, we build on our previous research (Stapleton et al., 2011b) that examined the relationships between PBDE exposure during pregnancy and maternal circulating thyroid hormone levels. We previously reported positive associations between maternal serum PBDEs and free and total thyroxine (T4) during the third trimester of pregnancy in a cohort of predominantly low-income, non-Hispanic black women in Durham County, North Carolina (Stapleton et al., 2011b). Using the same PBDE and thyroid hormone data set collected from pregnant women from the Healthy Pregnancy, Healthy Baby (HPHB) cohort, we extend this research by conducting an exploratory analysis of our hypothesis that PBDEs may interfere with fetal growth regulation either directly or by disrupting thyroid hormone levels or thyroid hormone homeostasis. We first examine whether maternal PBDE serum levels are adversely associated with infant birth weight, head circumference, birth length, and birth weight percentile for gestational age in this cohort. We then explore the potential mediating role of thyroid hormones in the association of birth outcomes with PBDEs/OH-BDEs. We examine: a) how observed PBDE/OH-BDE-birth outcome associations change in the presence of thyroid hormone levels; and b) the potential for interaction between PBDEs and thyroid hormone levels on birth outcomes. Our examination of the possible mediating role of thyroid hormones builds on Harley et al.’s (2011)) recent investigation of this hypothesis based on TSH.

2. Material and methods

Detailed information regarding the participant recruitment, sample collection, extraction, and analysis are presented in our previous publication (Stapleton et al., 2011b). Outlined below is a brief summary of the methods.

2.1. Participant recruitment

Participants in this study were recruited from the HPHB Study in Durham County, North Carolina (Swamy, 2011; Burgette and Reiter, 2010; Miranda et al., 2010), a prospective cohort study that aimed to assess the joint effect of social, environmental, and host factors on pregnancy outcomes. All patients >34 weeks of gestation who were enrolled in the HPHB study and who were routine patients at the Durham County Health Department’s Prenatal Clinic at the Lincoln Community Health Center (Durham, NC) were eligible to participate in the present study. HPHB study eligibility required women to be residents of Durham County, at least 18 years of age, and English literate. Women with multiple gestation or any known fetal genetic or congenital anomalies were not eligible. All 140 women who were approached during their routine third trimester laboratory visit (35–36 weeks) agreed to participate. After women gave informed consent, samples were collected during the third trimester of pregnancy (>34 weeks of gestation). All aspects of this study were carried out in accordance with a human subjects research protocol approved by the Duke and University of Michigan Institutional Review Boards.

2.2. Sample collection

Blood samples (~8 mL for PBDEs and ~4 mL for thyroid hormones) were collected for flame retardant analysis during a routine third trimester prenatal clinic visit, centrifuged to isolate serum, and stored at −20 °C until analysis. At birth, information related to birth outcomes was abstracted from participant medical records.

2.3. Chemicals analysis

Five hormones, including free and total thyroxine (FT4 and TT4, respectively), free and total triiodothyronine (FT3 and TT3, respectively), and TSH, were analyzed in serum by the Duke University Hospital clinical laboratory. All Access assays were paramagnetic particle, chemiluminescent immunoassays manufactured by Beckman Coulter Inc. (Fullerton, CA). Estimates of imprecision (%CV) ranged from 3.7–9.2% in all assays except FT3, which was 10.4%. More details are provided in Stapleton et al. (Stapleton et al., 2011b) PBDE/OH-BDE analyses were analyzed by mass spectrometry and information on the specific internal, recovery, and quantitative standards used for the analyses can be found in Stapleton et al. (Stapleton et al., 2011b) All serum samples (approximately 3–5 g) were extracted and analyzed for a suite of 27 PBDE congeners using a previously published method (Stapleton et al., 2008). A subset of 60 samples were further analyzed for 246 TBP (2,4,6-tribromophenol) and four different hydroxylated PBDEs, including 6′-OH-BDE 49, 6-OH-BDE 99, 4′-OH-BDE 49, and 6′-OH-BDE 47, by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. 6′-OH-BDE 49 and 6-OH-BDE 99 were less than the method detection limit (MDL) in all samples and were thus not included in further statistical analysis. Lipids were determined in serum using an enzymatic assay. All PBDE/OH-BDE values are reported on a lipid weight basis (e.g. ng/g lipid).

2.4. Outcomes

Infant outcomes including birth weight (g), head circumference (cm), birth length (cm), and birth weight percentile for gestational age were analyzed as continuous variables. Birth weight percentile for gestational age was determined by comparing the birth weight for each birth in our study population with a national sex-specific reference distribution (Anthopolos et al., 2013).

2.5. Exposures

For statistical modeling, we included PBDEs and hydroxylated PBDEs detected in >50% of serum, namely, BDE 47, BDE 99, BDE 100, BDE 153, along with the hydroxylated PBDEs 4′-OH-BDE 49 and 6′-OH-BDE 47. We calculated a summed PBDE variable (ΣPBDE) from the PBDE compounds with detection frequencies of at least 50%. An analogous summed phenolic metabolite variable was derived (ΣOH-BDE). Thyroid hormones considered in the analysis were TT4, FT4, TT3, FT3, and TSH.

To assess the functional form of the association of each birth outcome with PBDE/OH-BDE congeners, we constructed nonparametric localized regression plots (LOESS) of each birth outcome and PBDE/ OH-BDE overlaid with the ordinary least squares regression line and corresponding 95% confidence bands. In addition, we visually assessed plots of standardized residuals versus each PBDE/OH-BDE congener from adjusted linear regression models of each birth outcome for potential violations of the linear modeling assumption of constant variance. This exploratory analysis led us to apply a log base 2 transformation of serum concentrations of PBDE/OH-BDE congeners. Coefficient estimates for individual PBDEs/OH-BDEs are thus interpreted as the expected change in a given birth outcome associated with a 2-fold increase (or doubling) of the exposure. PBDEs/OH-BDEs were centered on the log scale in statistical models.

We used analogous techniques to characterize the functional form of the association between each birth outcome with thyroid hormones. With the exception of TT4, thyroid hormones were also log base 2 transformed and centered on the log scale in statistical modeling. TT4 was centered at its mean and scaled to represent a change from the 25th to the 75th percentile of the distribution, henceforth referred to as an interquartile (IQR) increase.

2.6. Covariates

Our objective was to conduct an exploratory analysis of the potential mediating role of thyroid hormones in the association of birth outcomes with PBDEs/OH-BDEs. To determine control variables in regression modeling, we developed a conceptual model on the basis of directed acyclic graphs with thyroid hormones intervening along the causal pathway between PBDEs/OH-BDEs and birth outcomes. Potential confounders of the PBDE- and OH-BDE-birth outcome association and the thyroid hormone-birth outcome were identified from previous work. We controlled for maternal age, non-Hispanic black race, and maternal educational attainment level (Sjodin et al., 2008; Stapleton et al., 2012a). In addition, we controlled for parity, infant sex, and maternal smoking during pregnancy. While previous research has controlled for gestational age and pre-pregnancy BMI (Chao et al., 2007; Harley et al., 2011), in our conceptual model, adjustment for gestational age may introduce collider bias in estimating the associations with birth outcomes (Wilcox et al., 2011). While pre-pregnancy BMI may act as a confounder to the PBDE/OH-BDE-birth outcome association, in the main model specifications, we did not control for this variable because it may also be an intermediary along the causal pathway between thyroid hormones and birth outcomes. We originally sought to control for health insurance status; however, 100% of the cohort did not have private insurance. Maternal age was centered at its mean and scaled to represent an IQR increase in multivariable modeling.

2.7. Statistical analysis

In initial descriptive analysis, we computed summary statistics for maternal and infant characteristics, PBDEs and OH-BDEs, and thyroid hormones. Using simple linear regression, we examined unadjusted associations between each birth outcome and PBDE/OH-BDE.

We used multivariable linear regression to investigate our hypothesis that PBDEs/OH-BDEs were adversely associated with each birth outcome. We regressed each birth outcome on each PBDE/OH-BDE in separate models, controlling for maternal and infant characteristics. To explore the role of thyroid hormones in the relationship between birth outcomes and PBDEs/OH-BDEs, we fit analogous linear regression models (adjusting for the same potential confounders as previously indicated) that also individually controlled for each thyroid hormone. A subsequent set of regression models model added a PBDE/OH-BDE by thyroid hormone interaction term. In a sensitivity analysis, we reran our analysis controlling for pre-pregnancy BMI.

For the purposes of regression modeling, we conducted multiple imputation for values that were below detection limit for PBDEs, OH-BDEs, and thyroid hormones with at least 50% detection frequency, in addition to missing values in maternal and infant-level covariates, using the Amelia package (Honaker et al., 2011) in R 3.2.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2015). Multiple imputation is predicated on the assumption that missing values are missing at random (MAR) – so that the likelihood of missing values depends only on observed covariates but not on unobserved data. The Amelia package (Honaker et al., 2011) builds a multiple imputation model based on the assumption of multivariate normality, employing an expectation-maximization bootstrap algorithm to capture uncertainty in the complete data parameters before drawing new imputed values. We applied log and square root transformations to skewed distributions and count variables, respectively, in the imputation model. Below detection limit values were imputed by using the detection limit as the upper bound (Gelman and Hill, 2006). The maximum detection limit was used for exposure measurements with multiple detection limits. The multiple imputation model was visually assessed for abnormalities by comparing the densities of the mean imputations and observed values (Honaker et al., 2011). In addition, we assessed the accuracy of the multiple imputation model by generating imputations of observed values − as if they had been missing. We then examined whether observed values fell within the 90% confidence interval of what the imputed value would have been – had the observed value been missing. This is an indication of model accuracy (Honaker et al., 2011). We generated 25 imputations (White et al., 2011) over which parameter estimates from regression models were averaged and corresponding standard errors were adjusted for variability due to the imputation model using Rubin’s formula (Harrell, 2013).

All statistical analysis was performed using R 3.2.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing). The statistical significance level was set at α <0.05 except for testing hypotheses relating to interaction, for which we used α < 0.10.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive analysis

Thyroid hormone measurements were available for 137 of the 140 study participants. The three participants without thyroid hormone measurements were removed from all subsequent analysis. Due to problems with laboratory measurements of some hormones in a few samples, we had 136 women with thyroid measurements available per individual hormone. Among the subset of 60 women who were analyzed for metabolites, all measurements were available for 4′-OH-BDE 49 and 6′-OH-BDE, but only 58 were available for 246 TBP due to a labeling error during laboratory analysis.

3.1.1. Maternal and infant-level characteristics

The majority of women were non-Hispanic black (80%) with at least a high school level education (85%) (Table 1). Mean birth weight was just under 3300 g (SD 418), above the clinical threshold for low birth weight of 2500 g, with average head circumference and birth length measuring 34 cm (SD 1 cm) and 49 cm (SD 2 cm), respectively. The average birth weight percentile for gestational age was 40 (SD 25).

Table 1.

Maternal and infant characteristics of pregnancy cohort, Durham, North Carolina (N = 137).

| Covariate | Descriptive statistic

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. missing | Mean (SD) | IQR | |

| Continuous variables | |||

| Birth weight, g | 4 | 3261 (418) | 3005–3570 |

| Birth length, cm | 17 | 49 (2) | 48–51 |

| Head circumference, cm | 15 | 34 (1) | 33–35 |

| Birth weight percentile for gestational age | 4 | 40 (25) | 19–59 |

| Maternal age, years | 0 | 23 (4) | 20–25 |

| Covariate | Descriptive statistic

|

||

| No. missing | n | % | |

|

| |||

| Categorical variables | |||

| Male infant sex | 2 | 63 | 47 |

| First birth | 0 | 69 | 50 |

| Maternal race | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 0 | 12 | 9 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 0 | 109 | 80 |

| Hispanic | 0 | 13 | 9 |

| Other race/ethnicity | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Maternal educational attainment | |||

| Less than high school | 0 | 20 | 15 |

| High school diploma | 0 | 73 | 53 |

| More than high school | 0 | 44 | 32 |

| No private insurance | 0 | 137 | 100 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Non-smoker | 0 | 89 | 65 |

| Smoker | 0 | 20 | 15 |

| Quit smoking | 0 | 28 | 20 |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range.

3.1.2. PBDEs, OH-BDEs, and thyroid hormones

Of the 27 PBDE congeners measured, eight were found above MDLs (Table 2). Only four BDE congeners (47, 99, 100 and 153) were detected in more than 50% of the samples analyzed. BDE 153 (2,2′,4,4′,5,5′-hexabromodiphenyl ether) and BDE 47 (2,2′,4,4′-tetrabromodiphenyl ether) were detected most frequently – in approximately 96% and 95% of serum samples, respectively. The congener found in the highest concentration was BDE 47 with 25th, median, 75th, and 95th percentiles each higher than those of other congeners. In the subset of 60 samples further analyzed for metabolites, 246 TBP, 4′-OH-BDE 49, and 6′-OH-BDE 47 were detected in 38, 72, and 67% of the serum samples analyzed, respectively. Relative to 4′-OH-BDE 49 and 6′-OH-BDE 47, 246 TBP was detected at the highest concentrations, despite having a detection frequency under 50%. Thyroid hormone data are also summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

PBDE and metabolite concentrations (nanograms per gram lipid) and thyroid hormone measurements in serum from pregnancy cohort, Durham, North Carolina (N = 137).

| N | MDL | % > MDL | Percentile

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 50 | 75 | 95 | ||||

| PBDEs | |||||||

| BDE 28 | 137 | 1.2–3.0 | 38.69 | <DL | <DL | 2.58 | 4.9 |

| BDE 47 | 137 | 2.0–4.5 | 94.89 | 8.98 | 18.87 | 30.64 | 111.36 |

| BDE 66 | 137 | 1.2 | 2.19 | <DL | <DL | <DL | <DL |

| BDE 99 | 137 | 2.0–4.5 | 64.23 | <DL | 5.5 | 12.59 | 46.33 |

| BDE 100 | 137 | 1.2 | 89.05 | 2.27 | 4.61 | 7.2 | 21.33 |

| BDE 85, 155 | 137 | 1.2 | 16.06 | <DL | <DL | <DL | 3.35 |

| BDE 153 | 137 | 1.2 | 96.35 | 3.82 | 5.65 | 9.82 | 31.97 |

| BDE 154 | 137 | 1.2 | 48.18 | <DL | <DL | 2.4 | 6.99 |

| Phenolic metabolites | |||||||

| 246 TBP | 55 | 1.4–2.5 | 38.18 | <DL | <DL | 14.94 | 101.67 |

| 4′-OH-BDE-49 | 57 | 0.01–0.03 | 71.93 | <DL | 0.12 | 0.27 | 2.04 |

| 6′-OH-BDE-47 | 57 | 0.01–0.03 | 66.67 | <DL | 0.19 | 0.57 | 4.9 |

| Thyroid hormones | |||||||

| TSH (μIU/mL) | 136 | 100 | 0.89 | 1.28 | 1.75 | 2.88 | |

| TT4 (μg/dL) | 136 | 0.5 | 98.53 | 5.18 | 6.9 | 8.5 | 10.33 |

| FT4 (ng/dL) | 136 | 100 | 0.59 | 0.66 | 0.75 | 0.89 | |

| TT3 (ng/dL) | 136 | 100 | 165.25 | 187.5 | 220.25 | 324.25 | |

| FT3 (pg/dL) | 136 | 100 | 2.47 | 2.71 | 2.97 | 3.35 | |

Abbreviations MDL, method detection limit; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; TT4, total thyroxine; FT4, free thyroxine; TT3, total triiodothyronine; FT3, free triiodothyronine.

3.1.3. Relationships among birth outcomes and PBDEs/OH-BDEs

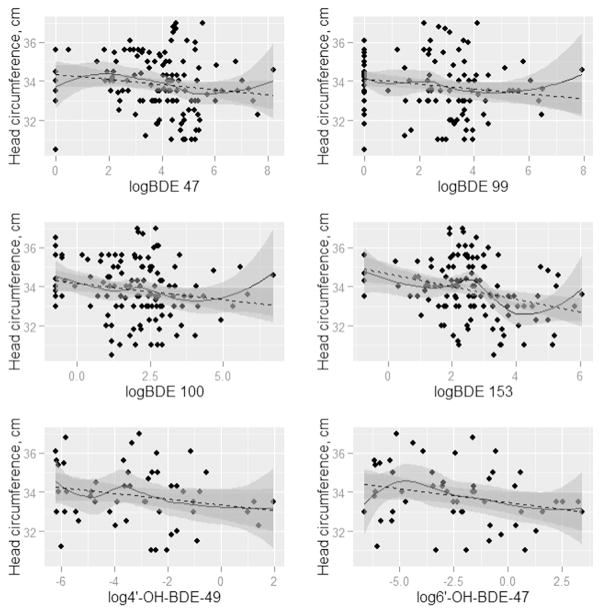

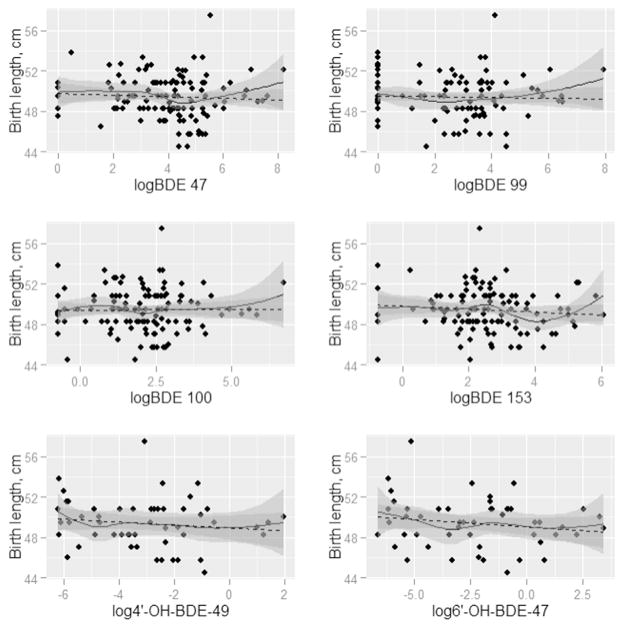

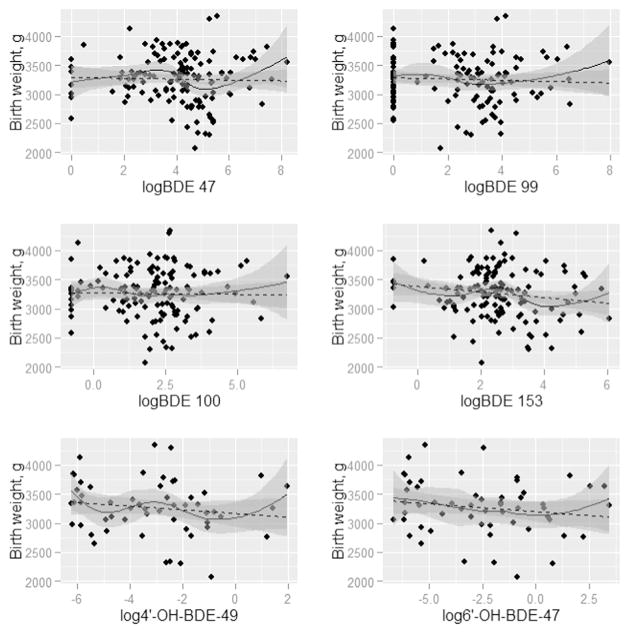

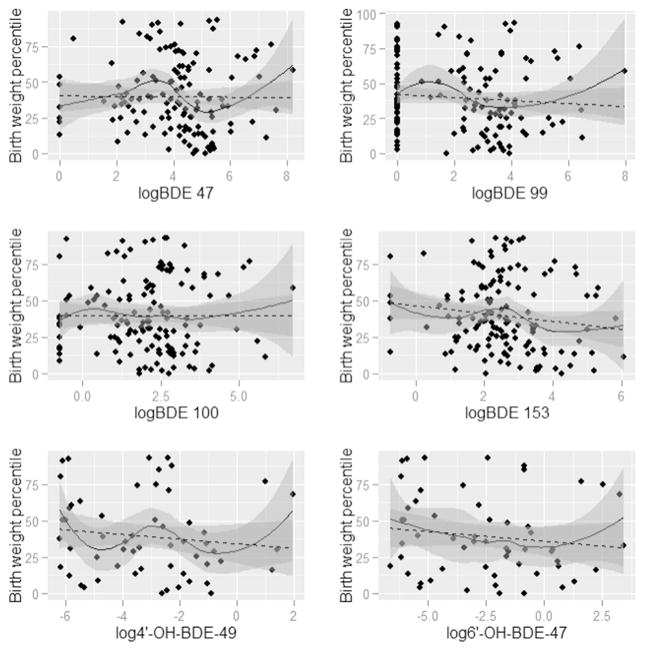

Figs. 1–4 present the nonparametric LOESS smoothed curves (solid line) between each individual PBDE/OH-BDE (with at least 50% detection frequency) on the log scale and head circumference, birth weight, birth weight percentile for gestational age, and birth length, respectively, overlaid on a scatter plot of the data. The dashed line is the ordinary least squares fitted line. Corresponding 95% confidence bands are represented in gray shading. Head circumference appeared inversely associated with BDE 100 and 153, along with OH-BDEs (Fig. 1). In Figs. 2–3, birth weight and birth weight percentile for gestational age decreased slightly with BDE 153 and each OH-BDE. Birth length generally did not appear associated with PBDEs or OH-BDEs (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

LOESS smoothed curves between each PBDE1 (nanograms per gram lipid) and head circumference (cm), overlaid on a scatter plot of the observed values (N = 1372). 1Each PBDE was log base 2 transformed. 2The N for phenolic metabolites (6′-OH-BDE-47, 4′-OH-BDE-49, and ΣOH-BDE) is 57.

Fig. 4.

LOESS smoothed curves between each PBDE1 (nanograms per gram lipid) and birth length (g), overlaid on a scatter plot of the observed values. (N = 1372). 1Each PBDE was log base 2 transformed. 2The N for phenolic metabolites (6′-OH-BDE-47, 4′-OH-BDE-49, and ΣOH-BDE) is 57.

Fig. 2.

LOESS smoothed curves between each PBDE1 (nanograms per gram lipid) and birth weight (g), overlaid on a scatter plot of the observed values (N = 1372). 1Each PBDE was log base 2 transformed. 2The N for phenolic metabolites (6′-OH-BDE-47, 4′-OH-BDE-49, and ΣOH-BDE) is 57.

Fig. 3.

LOESS smoothed curves between each PBDE1 (nanograms per gram lipid) and birth weight percentile for gestational age, overlaid on a scatter plot of the observed values. (N = 1372). 1Each PBDE was log base 2 transformed. 2The N for phenolic metabolites (6′-OH-BDE-47, 4′-OH-BDE-49, and ΣOH-BDE) is 57.

In unadjusted linear models of each birth outcome and PBDE/OH-BDE (Tables 3–4), BDE 153 and ΣPBDE were negatively associated with head circumference (coefficient = −0.32, 95% CI: −0.53, −0.12; coefficient = −0.23, 95% CI: (−0.44, −0.02), while the coefficients for BDE 47, 99, and 100 were each negative but did not obtain statistical significance at the 5% level (e.g., coefficient for BDE 47 = −0.17, 95% CI: −0.36, 0.01). In other words, for example, a doubling of BDE 153 was associated with an average decrease of 0.32 cm in head circumference, not accounting for other risk factors. In unadjusted models, OH-BDEs displayed similar negative associations but with 95% confidence intervals that barely covered the null (e.g., coefficient for 4′-OH-BDE-49 = −0.08, 95% CI: −0.23, 0.08). Birth weight, birth weight percentile for gestational age, and birth length were not associated with PBDEs/ OH-BDEs.

Table 3.

Unadjusted associations of each birth outcome with PBDEs (nanograms per gram lipid)a (N = 136).

| BDE 47

|

BDE 99

|

BDE 100

|

BDE 153

|

ΣPBDE

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Head circumference, cm | −0.17 (−0.36, 0.01) | −0.16 (−0.34, 0.03) | −0.1 (−0.32, 0.12) | −0.32 (−0.53, −0.12) | −0.23 (−0.44, −0.02) |

| Birth weight, g | −24.75 (−74.77, 25.28) | −13.17 (−65.59, 39.24) | −16.15 (−73.82, 41.51) | −50.73 (−110.5, 9.03) | −31.9 (−89.2, 25.41) |

| Birth weight percentile for gestational age | −1.19 (−4.23, 1.85) | −1.39 (−4.66, 1.87) | −0.75 (−4.27, 2.78) | −2.95 (−6.59, 0.69) | −1.85 (−5.35, 1.65) |

| Birth length, cm | −0.1 (−0.37, 0.17) | −0.02 (−0.29, 0.25) | 0.03 (−0.28, 0.33) | −0.13 (−0.44, 0.18) | −0.11 (−0.41, 0.2) |

Abbreviations: Coef., coefficient; CI, confidence interval.

Simple linear regression models estimating the relationship between PBDEs and each birth outcome. The logarithm base 2 was taken for all PBDEs. Log transformed PBDEs were centered at their mean.

Table 4.

Unadjusted associations of each birth outcome with OH-BDEs (nanograms per gram lipid)a (N = 56).

| 4′-OH-BDE-49

|

6′-OH-BDE-47

|

ΣOH-BDE

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Head circumference, cm | −0.08 (−0.23, 0.08) | −0.07 (−0.24, 0.09) | −0.13 (−0.33, 0.07) |

| Birth weight, g | −5.01 (−55.7, 45.68) | −6.39 (−48.28, 35.49) | −10.61 (−70.94, 49.72) |

| Birth weight percentile for gestational age | 0.02 (−3.23, 3.27) | −0.13 (−2.74, 2.48) | −0.36 (−4.01, 3.28) |

| Birth length, cm | −0.05 (−0.27, 0.18) | −0.04 (−0.26, 0.18) | −0.1 (−0.37, 0.18) |

Abbreviations: Coef., coefficient; CI, confidence interval.

Simple linear regression models estimating the relationship between OH-BDEs and each birth outcome. The logarithm base 2 was taken for all OH-BDEs. Log transformed OH-BDEs were centered at their mean.

3.2. Multivariable modeling of the associations among birth outcomes, PBDEs/OH-BDEs, and thyroid hormones

3.2.1. Head circumference, PBDEs/OH-BDEs, and thyroid hormones

Tables 5–6 show the models of head circumference, each PBDE/OH-BDE, and TT3, after accounting for maternal and infant risk factors including infant sex, parity, and maternal age, race, educational attainment and smoking status. In the models with PBDE only (Table 5), while BDE 47, 99, 153, and ΣPBDE were negatively associated with head circumference, ranging in magnitude from −0.08 (e.g., BDE 47, 95% CI: −0.26, 0.11) to −0.20 (BDE 153, 95% CI: −0.42, 0.02), none of the associations reached statistical significance at the 5% level. TT3 was consistently negatively associated with head circumference (see Models with PBDE and TT3). For example, in the ΣPBDE model, a 2-fold increase in TT3 was associated with an average 0.63 cm decrease (95% CI: −1.26, 0) in head circumference, holding other factors constant. In models with PBDE, TT3, and their interaction, only the BDE 99 by TT3 term appeared suggestive of interaction; while this relationship did not obtain statistical significance based on a 90% confidence interval (coefficient = −0.45, 90% CI: −0.91, 0.01), the findings are still suggestive of an interaction with this particular PBDE. Similar patterns were present among the hydroxylated PBDEs (Table 6). Coefficients for PBDEs were substantively unchanged in models with and without control for TT3.

Table 5.

Adjusted associations of head circumference (cm) with PBDEs (nanograms per gram lipid) and TT3a (N = 136).

| BDE controlled | BDE 47

|

BDE 99

|

BDE 100

|

BDE 153

|

ΣPBDE

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Models with PBDE only | |||||

| BDE | −0.08 (−0.26, 0.11) | −0.08 (−0.27, 0.11) | 0.01 (−0.21, 0.22) | −0.2 (−0.42, 0.02) | −0.11 (−0.32, 0.11) |

| Models with PBDE and TT3 only | |||||

| BDE | −0.07 (−0.25, 0.12) | −0.09 (−0.28, 0.1) | 0 (−0.21, 0.22) | −0.19 (−0.41, 0.02) | −0.1 (−0.32, 0.11) |

| TT3 | −0.62 (−1.25, 0.02) | −0.64 (−1.27, −0.01) | −0.63 (−1.26, 0) | −0.61 (−1.24, 0.01) | −0.63 (−1.26, 0) |

| Models with PBDE, TT3, and their interaction | |||||

| BDE | −0.1 (−0.28, 0.09) | −0.13 (−0.32, 0.06) | 0.01 (−0.21, 0.22) | −0.2 (−0.42, 0.03) | −0.14 (−0.35, 0.08) |

| TT3 | −0.61 (−1.24, 0.03) | −0.58 (−1.21, 0.04) | −0.63 (−1.28, 0.01) | −0.61 −1.24, 0.02) ( | −0.62 (−1.25, 0.01) |

| BDE × TT3 | −0.31 (−0.84, 0.22) | −0.45 (−1.01, 0.1) | 0 (−0.57, 0.58) | −0.04 (−0.64, 0.57) | −0.32 (−0.93, 0.28) |

Abbreviations: Coef., coefficient; CI, confidence interval; TT3, total triiodothyronine.

Multiple linear regression models estimating the relationship between PBDEs, TT3, and head circumference controlled for non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity, maternal age, maternal educational attainment level, first birth, infant sex, and maternal smoking status. The logarithm base 2 was taken for TT3 and all PBDEs. Log transformed PBDEs and TT3 were centered at their mean.

Table 6.

Adjusted associations of head circumference (cm) with OH-BDEs (nanograms per gram lipid) and TT3a (N = 56).

| OH-BDE controlled | 4′-OH-BDE-49

|

6′-OH-BDE-47

|

ΣOH-BDE

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | Coef. (95% CI) | |

| Models with OH-BDE only | |||

| OH-BDE | −0.06 (−0.2, 0.09) | −0.08 (−0.23, 0.06) | −0.11 (−0.29, 0.07) |

| Models with OH-BDE and TT3 only | |||

| OH-BDE | −0.07 (−0.21, 0.07) | −0.08 (−0.23, 0.06) | −0.13 (−0.31, 0.05) |

| TT3 | −1.11 (−2.05, −0.17) | −1.03 (−1.94, −0.12) | −1.09 (−2.01, −0.18) |

| Models with OH-BDE, TT3, and their interaction | |||

| OH-BDE | −0.06 (−0.21, 0.09) | −0.09 (−0.23, 0.06) | −0.13 (−0.32, 0.06) |

| TT3 | −0.98 (−2.02, 0.06) | −1.08 (−2.03, −0.14) | −1.11 (−2.08, −0.15) |

| OH-BDE × TT3 | −0.18 (−0.63, 0.27) | 0.09 (−0.24, 0.41) | 0.04 (−0.44, 0.52) |

Abbreviations: Coef., coefficient; CI, confidence interval; TT3, total triiodothyronine.

Multiple linear regression models estimating the relationship between OH-BDEs, TT3, and head circumference controlled for non-Hispanic black race/ethnicity, maternal age, maternal educational attainment level, first birth, infant sex, and maternal smoking status. The logarithm base 2 was taken for TT3 and all OH-PBDEs. Log transformed OH-BDEs and TT3 were centered at their mean.

In separate modeling with TT4, FT4, FT3, and TSH (data not shown), thyroid hormones did not appear associated with PBDEs. Estimated coefficients for PBDEs/OH-BDEs were consistent with those presented in the TT3 models.

In a sensitivity analysis, adjustment for pre-pregnancy BMI did not substantively change estimated associations (data not shown).

3.2.2. Other birth outcomes, PBDEs/OH-BDEs, and thyroid hormones

Consistent with the unadjusted models of birth weight, birth weight percentile for gestational age, and birth length, we did not observe an association of these birth outcomes with PBDEs/OH-BDEs in models adjusted for maternal and infant characteristics (data not shown). Controlling for each of thyroid hormones did not alter these findings (data not shown). Estimated associations remained unchanged after adjusting for pre-pregnancy BMI (data not shown).

4. Discussion

This study suggests that in a cohort of predominantly African American low-income pregnant women, certain maternal serum PBDE levels may be adversely associated with infant head circumference; however, confirmatory studies are needed in larger sample sizes. The association between head circumference and thyroid hormone levels also depended on the specific thyroid hormone. We did not find evidence to support our hypothesis of a potential mediating role of thyroid hormones in the association between head circumference and PBDE/ OH-BDE levels; nor did we find evidence of interaction between PBDE/OH-BDE levels and thyroid hormones. Birth weight, birth length, and birth weight percentile for gestational age did not appear associated with PBDEs/OH-BDEs in our study sample.

We found suggestive evidence of a relationship between certain maternal PBDE levels and head circumference consistent with previous research while in the context of a predominantly non-occupationally exposed African-American cohort of pregnant women. The maternal PBDE levels in our cohort were within the national range of exposures based on levels reported in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004 (Woodruff et al., 2011) and were similar to those reported in previous work (Harley et al., 2011). Previously, PBDEs have been associated with various pregnancy-related health measures, including reduced gestational age, birth weight, birth length, and head circumference, among others (Foster et al., 2011; Chao et al., 2007; Harley et al., 2011). The Harley et al. (Harley et al., 2011) cohort comprises primarily low-income Mexican women with higher exposure to agricultural pesticides, and observed associations centered on birth weight. For example, in adjusted models, a 10-fold increase in BDE 47 was associated with a decrease in birth weight of 115 g (95% CI: −229, −2). Unlike our study, Harley et al. (2011)), who controlled for maternal weight gain in addition to gestational age, did not observe an association with head circumference; however, both of our studies present associations with birth outcomes that are characterized by wide confidence intervals. Other studies presenting associations with birth outcomes (but also not head circumference) measured PBDEs in umbilical cord serum or breast milk.

Fetuses exclusively rely upon maternal thyroid hormone levels during the first half of pregnancy, and partly during the second half of pregnancy; therefore, mechanisms that alter the supply of thyroid hormone levels reaching the fetus can negatively impact development (Zhang et al., 2011; Chan et al., 2009). We previously found a positive association between maternal serum PBDE levels and thyroid hormones in this cohort, and moreover, TT3 appeared to correlate with head circumference. Despite the compelling biological framework, and the aforementioned associations observed in separate analytical work, in the current multivariable modeling, we did not find evidence that suggests thyroid hormones are intermediaries in the pathway between PBDE exposure and head circumference. This agrees with Harley et al., who report that accounting for TSH only marginally reduced the magnitude of the association between BDE 47 and birth weight. (Harley et al., 2011) Alternatively, PBDEs may have a greater influence on thyroid regulation in the fetus, rather than the mother. Previous research by our laboratory has demonstrated that PBDEs and OH-BDEs can significantly inhibit thyroid hormone deiodinase (Dio) activity, both in vivo and in vitro, and thyroid hormone sulfotransferase activity in vitro (Butt et al., 2011; Butt and Stapleton, 2013; Noyes et al., 2011). A specific Dio isoform, Dio3, is highly expressed in the placenta, and its activity is critical in buffering the supply of thyroid hormones to the developing fetus (Chan et al., 2009). Studies conducted with Dio3 knock-out mice have shown that the loss of DI activity can result in restrictions on fetal growth, increased perinatal activity, and alterations in circulating thyroid hormone levels (Chan et al., 2009; Hernandez et al., 2006; Hernandez et al., 2007). Therefore, inhibition of Dio3 activity in placental tissues by PBDEs/OH-BDEs may be a contributing factor to reductions in infant growth and subsequent birth outcomes. Several studies have also demonstrated that PBDEs or OH-BDEs can inhibit several additional processes that regulate thyroid hormones in the body, such as hepatic thyroid hormone glucuronidation activity and serum transport. (Butt et al., 2011; Meerts et al., 2000; Szabo et al., 2009) However, tissue specific effects of PBDEs on thyroid hormone regulation, particularly in placental tissues, are largely unexplored and require further research.

While we found a suggestive negative association of head circumference with certain PBDE levels, the clinical significance of the smaller head circumferences is unclear, as measurements in our sample were generally within the clinically normal range. However, at the population level, small effects can have large impacts particularly when exposures are common — as in the case of PBDEs (Weiss, 1988). Children at the lower tail of the distribution may suffer significant consequences, such as disability. Head circumference is increasingly being used as a measure of infant health (Taal et al., 2012; Brantsaeter et al., 2012; Kallen, 2000; Lunde et al., 2007), and scientific inquiry is increasingly being directed at the clinical implications of impacts on head circumference (Barker et al., 1993; Osmond and Barker, 2000; Barker et al., 1992; Veena et al., 2010; Elder et al., 2008). The potential clinical implications of the link between head circumference and PBDE levels warrant further investigation.

This study has several limitations. Concerning measurement of thyroid hormones and PBDEs/OH-BDEs, we measured free thyroid hormone levels using an immunoassay. Free hormone levels may be biased by the concentration of proteins that bind the thyroid hormones. In addition, immunoassays have generally been validated using non-pregnant adults. Because the concentrations of protein-bound T4 are often lower among non-pregnant adults compared to pregnant women in their third trimester, our data may not be fully consistent with how the immunoassays were designed to be used. In addition, because we only measured PBDEs during the third trimester, we do not have a clear sense of how PBDE body burden changed over the course of pregnancy. However, the lower molecular weight of PBDE compounds measured here tend to have very long half-lives on the order of years (Geyer et al., 2004). Thus, third trimester levels likely are representative of levels throughout pregnancy. Finally, because we are assessing measurement of lipid soluble chemicals, observed associations could be an effect of the variations in lipid levels, even after “correcting” for lipid variability.

Our study was also hindered by data limitations. While we had a larger sample size than is typical for this area of research (apart from recently published work by Harley et al. (N = 286)) (Harley et al., 2011), our sample size remained a limiting factor. For example, in conducting a formal mediation analysis assuming no interaction between exposure and outcome, a sample size of over 500 would be necessary to detect partial mediation of moderate effect size (assuming 80% power and type I error of 0.05) (Fritz and Mackinnon, 2007). We thus conducted an exploratory analysis to provide preliminary data on a research area that has received little attention to date. Due to data limitations, we were not able to account for suspected confounders that have been controlled in previous work, such as alcohol and drug use (Harley et al., 2011). Our cohort included only women who were >34 weeks gestation, which may have limited our ability to detect a relationship between birth weight and PBDEs. Finally, concerns about multiple testing are valid. Using a five percent statistical significance level, we can expect to wrongly reject the null hypothesis in one of every 20 hypothesis tests – assuming independence among hypothesis tests. We have consequently emphasized a cautious interpretation of associations, with focus on patterns of associations across models rather than singling out any one relationship in particular.

5. Conclusion

This research contributes to the growing body of research on PBDEs and birth outcomes both nationally and outside the United States. We add to the nascent literature exploring the potential relationships among PBDEs/OH-BDEs, thyroid hormone levels, and birth outcomes. Future research is needed with larger sample sizes, and in addition, more sophisticated methods for combining multiple exposure measurements. More generally, future research may focus on identifying intermediate variables along the pathway between PBDEs and birth outcomes that might help shape clinical interventions now that PBDEs have been phased out.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (RD-83329301). H.M.S. was also partially supported by grant R01 ES016099 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and by funds from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The article’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the state and city health departments of the authors.

The authors wish to thank Dr. Ellen Cooper for the LC/MSMS analysis. We would also like to thank all of our clinical recruiters and participants. Special thanks are extended to Dr. Pamela Maxson for managing the recruitment effort for this project and to Claire Osgood for data management support.

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- FT4

free thyroxine

- FT3

free triiodothyronine

- HPHB

Healthy Pregnancy, Healthy Baby

- PBDE

polybrominated diphenyl ether

- OH-BDE

polybrominated diphenyl ether metabolite

- TSH

thyroid stimulating hormone

- T4

thyroxine

- TT4

total thyroxine

- TT3

total triiodothyronine

- T3

triiodothyronine

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Anthopolos R, Edwards SE, Miranda ML. Effects of maternal prenatal smoking and birth outcomes extending into the normal range on academic performance in fourth grade in North Carolina, USA. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2013;27:564–574. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Godfrey KM, Osmond C, Bull A. The relation of fetal length, ponderal index and head circumference to blood pressure and the risk of hypertension in adult life. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1992;6:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1992.tb00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Osmond C, Simmonds SJ, Wield GA. The relation of small head circumference and thinness at birth to death from cardiovascular disease in adult life. BMJ. 1993;306:422–426. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6875.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr DB, Bishop A, Needham LL. Concentrations of xenobiotic chemicals in the maternal-fetal unit. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;23:260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brantsaeter AL, Birgisdottir BE, Meltzer HM, Kvalem HE, Alexander J, Magnus P, et al. Maternal seafood consumption and infant birth weight, length and head circumference in the norwegian mother and child cohort study. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:436–444. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511003047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgette LF, Reiter JP. Multiple imputation for missing data via sequential regression trees. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172:1070–1076. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt CM, Stapleton HM. Inhibition of thyroid hormone sulfotransferase activity by brominated flame retardants and halogenated phenolics. Chem Res Toxicol. 2013;26:1692–1702. doi: 10.1021/tx400342k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt CM, Wang D, Stapleton HM. Halogenated phenolic contaminants inhibit the in vitro activity of the thyroid-regulating deiodinases in human liver. Toxicol Sci. 2011;124:339–347. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SY, Vasilopoulou E, Kilby MD. The role of the placenta in thyroid hormone delivery to the fetus. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2009;5:45–54. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HR, Wang SL, Lee WJ, Wang YF, Papke O. Levels of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in breast milk from central Taiwan and their relation to infant birth outcome and maternal menstruation effects. Environ Int. 2007;33:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevrier J, Harley KG, Bradman A, Gharbi M, Sjodin A, Eskenazi B. Polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) flame retardants and thyroid hormone during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1444–1449. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1001905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit CA, Alaee M, Muir DC. Levels and trends of brominated flame retardants in the Arctic. Chemosphere. 2006;64:209–233. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingemans MM, van den Berg M, Westerink RH. Neurotoxicity of brominated flame retardants: (in)direct effects of parent and hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers on the (developing) nervous system. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:900–907. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder LM, Dawson G, Toth K, Fein D, Munson J. Head circumference as an early predictor of autism symptoms in younger siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38:1104–1111. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0495-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EU-Commission. Communication from the Commission on the results of the risk evaluation of chlorodifluoromethane, bis(pentabromophenyl)ether and methenamine and on the risk reduction strategy for the substance methenamine (2008/C131/04) Off J Eur Union. 2008:C 131/7–C 131/12. [Google Scholar]

- Fernie KJ, Shutt JL, Mayne G, Hoffman D, Letcher RJ, Drouillard KG, et al. Exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs): changes in thyroid, vitamin a, glutathione homeostasis, and oxidative stress in American kestrels (falco sparverius) Toxicol Sci. 2005;88:375–383. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster WG, Gregorovich S, Morrison KM, Atkinson SA, Kubwabo C, Stewart B, et al. Human maternal and umbilical cord blood concentrations of polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Chemosphere. 2011;84:1301–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, Mackinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol Sci. 2007;18:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Hill J. Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models. Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Geyer HJ, Schramm KW, Darnerud PO, Aune M, Fecht EA, Fried KW, et al. Terminal Elimination Half-Lives of the Brominated Flame Retardants TBBPA, HBCD, and Lower Brominated PBDEs in Humans. Berlin: 2004. pp. 3820–3825. [Google Scholar]

- Hale RC, Alaee M, Manchester-Neesvig JB, Stapleton HM, Ikonomou MG. Polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants in the North American environment. Environ Int. 2003;29:771–779. doi: 10.1016/S0160-4120(03)00113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley KG, Marks AR, Chevrier J, Bradman A, Sjodin A, Eskenazi B. PBDE concentrations in women’s serum and fecundability. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:699–704. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harley KG, Chevrier J, Aguilar SR, Sjodin A, Bradman A, Eskenazi B. Association of prenatal exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers and infant birth weight. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:885–892. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. Springer Science & Business Media; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Herbstman JB, Sjodin A, Kurzon M, Lederman SA, Jones RS, Rauh V, et al. Prenatal exposure to PBDEs and neurodevelopment. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:712–719. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Fiering S, Galton VA, St GD. Type 3 deiodinase is critical for the maturation and function of the thyroid axis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:476–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI26240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Martinez ME, Liao XH, Van SJ, Refetoff S, Galton VA, et al. Type 3 deiodinase deficiency results in functional abnormalities at multiple levels of the thyroid axis. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5680–5687. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M. Amelia II: A program for missing data. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hulbert AJ. Thyroid hormones and their effects: a new perspective. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2000;75:519–631. doi: 10.1017/s146479310000556x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PI, Altshul L, Cramer DW, Missmer SA, Hauser R, Meeker JD. Serum and follicular fluid concentrations of polybrominated diphenyl ethers and in-vitro fertilization outcome. Environ Int. 2012;45:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallen K. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and infant head circumference at birth. Early Hum Dev. 2000;58:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(00)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TH, Lee YJ, Lee E, Patra N, Lee J, Kwack SJ, et al. Exposure assessment of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDE) in umbilical cord blood of Korean infants. J Toxic Environ Health A. 2009;72:1318–1326. doi: 10.1080/15287390903212436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law RJ, Allchin CR, de Boer J, Covaci A, Herzke D, Lepom P, et al. Levels and trends of brominated flame retardants in the European environment. Chemosphere. 2006a;64:187–208. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law K, Halldorson T, Danell R, Stern G, Gewurtz S, Alaee M, et al. Bioaccumulation and trophic transfer of some brominated flame retardants in a lake winni-peg (Canada) food web. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2006b;25:2177–2186. doi: 10.1897/05-500r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunde A, Melve KK, Gjessing HK, Skjaerven R, Irgens LM. Genetic and environmental influences on birth weight, birth length, head circumference, and gestational age by use of population-based parent-offspring data. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:734–741. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main KM, Kiviranta H, Virtanen HE, Sundqvist E, Tuomisto JT, Tuomisto J, et al. Flame retardants in placenta and breast milk and cryptorchidism in newborn boys. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1519–1526. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meerts IA, van Zanden JJ, Luijks EA, van Leeuwen-Bol I, Marsh G, Jakobsson E, et al. Potent competitive interactions of some brominated flame retardants and related compounds with human transthyretin in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 2000;56:95–104. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/56.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda ML, Edwards SE, Swamy GK, Paul CJ, Neelon B. Blood lead levels among pregnant women: historical versus contemporaneous exposures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2010;7:1508–1519. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7041508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes PD, Hinton DE, Stapleton HM. Accumulation and debromination of decabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-209) in juvenile fathead minnows (pimephales promelas) induces thyroid disruption and liver alterations. Toxicol Sci. 2011;122:265–274. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmond C, Barker DJ. Fetal, infant, and childhood growth are predictors of coronary heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension in adult men and women. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 3):545–553. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose M, Bennett DH, Bergman A, Fangstrom B, Pessah IN, Hertz-Picciotto I. PBDEs in 2–5 year-old children from California and associations with diet and indoor environment. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:2648–2653. doi: 10.1021/es903240g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roze E, Meijer L, Bakker A, Van Braeckel KN, Sauer PJ, Bos AF. Prenatal exposure to organohalogens, including brominated flame retardants, influences motor, cognitive, and behavioral performance at school age. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117:1953–1958. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjodin A, Wong LY, Jones RS, Park A, Zhang Y, Hodge C, et al. Serum concentrations of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) and polybrominated biphenyl (PBB) in the United States population: 2003–2004. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:1377–1384. doi: 10.1021/es702451p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Sjodin A, Jones RS, Niehoser S, Zhang Y, Patterson DG. Serum levels of polyhrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) in foam recyclers and carpet installers working in the United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:3453–3458. doi: 10.1021/es7028813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Klosterhaus S, Keller A, Ferguson PL, van Bergen S, Cooper E, et al. Identification of flame retardants in polyurethane foam collected from baby products. Environ Sci Technol. 2011a;45:5323–5331. doi: 10.1021/es2007462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Eagle S, Anthopolos R, Wolkin A, Miranda ML. Associations between polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE) flame retardants, phenolic metabolites, and thyroid hormones during pregnancy. Environ Health Perspect. 2011b;119:1454–1459. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Eagle S, Sjodin A, Webster TF. Serum PBDEs in a North Carolina toddler cohort: associations with handwipes, house dust, and socioeconomic variables. Environ Health Perspect. 2012a;120:1049–1054. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapleton HM, Sharma S, Getzinger G, Ferguson PL, Gabriel M, Webster TF, et al. Novel and high volume use flame retardants in US couches reflective of the 2005 PentaBDE phase out. Environ Sci Technol. 2012b;46:13432–13439. doi: 10.1021/es303471d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swamy G, Garrett ME, Miranda ML, Ashley-Koch A. Maternal Vitamin D Receptor Genetic Variation Contributes to Infant Birthweight among Black Mothers. Am J Med Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo DT, Richardson VM, Ross DG, Diliberto JJ, Kodavanti PR, Birnbaum LS. Effects of perinatal PBDE exposure on hepatic phase I, phase II, phase III, and deiodinase 1 gene expression involved in thyroid hormone metabolism in male rat pups. Toxicol Sci. 2009;107:27–39. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taal HR, St PB, Thiering E, Das S, Mook-Kanamori DO, Warrington NM, et al. Common variants at 12q15 and 12q24 are associated with infant head circumference. Nat Genet. 2012;44:532–538. doi: 10.1038/ng.2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Loganath A, Chong YS, Obbard JP. Exposure to persistent organic pollutants in utero and related maternal characteristics on birth outcomes: a multivariate data analysis approach. Chemosphere. 2009;74:428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tullo A. Great lakes to phase out flame retardants. Chem Eng News. 2003;81:13. [Google Scholar]

- Turyk ME, Persky VW, Imm P, Knobeloch L, Chatterton R, Anderson HA. Hormone disruption by PBDEs in adult male sport fish consumers. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116:1635–1641. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veena SR, Krishnaveni GV, Wills AK, Kurpad AV, Muthayya S, Hill JC, et al. Association of birthweight and head circumference at birth to cognitive performance in 9- to 10-year-old children in south India: prospective birth cohort study. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:424–429. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181d00b45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcaino E, Grimalt JO, Lopez-Espinosa MJ, Llop S, Rebagliato M, Ballester F. Polybromodiphenyl ethers in mothers and their newborns from a non-occupationally exposed population (Valencia, Spain) Environ Int. 2011;37:152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong AM, Webster GM, Romano ME, Braun JM, Zoeller RT, Hoofnagle AN, et al. Environ Health Perspect. Cincinnati, USA: 2015. Maternal Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether (PBDE) Exposure and Thyroid Hormones in Maternal and Cord Sera: The HOME Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B. Neurobehavioral toxicity as a basis for risk assessment. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1988;9:59–62. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(88)90118-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30:377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Basso O. On the pitfalls of adjusting for gestational age at birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;174:1062–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff TJ, Zota AR, Schwartz JM. Environmental chemicals in pregnant women in the United States: NHANES 2003–2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:878–885. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K, Xu X, Liu J, Guo Y, Li Y, Huo X. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers in umbilical cord blood and relevant factors in neonates from guiyu, China. Environ Sci Technol. 2010;44:813–819. doi: 10.1021/es9024518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Tian Y, Yang XF, Cui C, Gao Y, Wang XJ, et al. Concentration of polybrominated diphenyl ethers in umbilical cord serum and the influence on newborns birth outcomes in Shanghai. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;45:490–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Taylor MM, DeVito MJ, Crofton KM. Developmental exposure to brominated diphenyl ethers results in thyroid hormone disruption. Toxicol Sci. 2002;66:105–116. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/66.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zota AR, Park JS, Wang Y, Petreas M, Zoeller RT, Woodruff TJ. Polybrominated diphenyl ethers, hydroxylated polybrominated diphenyl ethers, and measures of thyroid function in second trimester pregnant women in California. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:7896–7905. doi: 10.1021/es200422b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]