Abstract

Lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (NPs), consisting of a polymeric core and a lipid shell, have been intensively examined as delivery systems for cancer drugs, imaging agents, and vaccines. For applications in vaccine particularly, the hybrid NPs need to be able to protect the enclosed antigens during circulation, easily be up-taken by dendritic cells, and possess good stability for prolonged storage. However, the influence of lipid composition on the performance of hybrid NPs has not been well studied. In this study, we demonstrate that higher concentrations of cholesterol in the lipid layer enable slower and more controlled antigen release from lipid-poly(lactide-co-glycolide) acid (lipid-PLGA) NPs in human serum and phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Higher concentrations of cholesterol also promoted in vitro cellular uptake of hybrid NPs, improved the stability of the lipid layer, and protected the integrity of the hybrid structure during long- term storage. However, stabilized hybrid structures of high cholesterol content tended to fuse with each other during storage, resulting in significant size increase and lowered cellular uptake. Additional experiments demonstrated that PEGylation of NPs could effectively minimize fusion-caused size increase after long term storage, leading to improved cellular uptake, although excessive PEGylation will not be beneficial and led to reduced improvement.

Keywords: PLGA, hybrid nanoparticle, lipid layer, cholesterol, delivery system

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

In the past decade, lipid-polymer hybrid NPs have been increasingly recognized as promising drug delivery vehicles due to their multiple advantageous features [1]. Hybrid NPs are capable of carrying both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs with high loading capacity [2]; they also allow step-wise release of multiple drugs of distinct properties and purposes [3]. Furthermore, pharmacokinetics of delivered drugs can be easily modified by tuning physiochemical properties of hybrid NPs [4]. In addition, targeted delivery of drugs can be performed by introducing site specific antibodies or other targeting molecules to the exterior surface of hybrid NPs [5].

Lipid-polymer hybrid NPs consist of two major components. The inner part is a polymer core, which is capable of encapsulating both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs as well as offering rigid support for the hybrid entity. The outer part is a lipid layer coating the external surface of the polymer core, and it can function as (i) a biocompatible shield to avoid fast clearance of NPs by the reticuloendothelial system (RES), (ii) a template for surface modifications, enabling targeted delivery of drugs, and (iii) a barrier to prevent the fast leakage of water-soluble drugs, allowing prolonged and controlled release of drugs [2].

Previous studies mainly focused on developing methods for fabricating hybrid NPs and potential applications of hybrid NPs for delivery of various kinds of drugs [1]. However, the impact of the composition of the lipid layer on the performance of hybrid NPs has not been well studied. It has been clearly elucidated that lipid composition has a significant influence on the efficacy of drugs delivered by liposomes. For example, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE)-based liposomes were markedly more stable in 20% serum than 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DSPE)-based liposomes [6]. It was also reported that the presence or the absence of 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (DSPE–PEG(2000)) had a great impact on lipid transition temperature and drug release, and increasing the molar percentage of 1-myristoyl-2-stearoylsn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (MSPC) in temperature sensitive liposomes led to faster initial doxorubicin release [7].

Among lipid constituents, cholesterol plays an unique as well as essential role as a main membrane-stabilizing material, and has been extensively investigated and utilized in the majority of liposome products on the market [8]. In addition to its ability to improve lipid bilayer stability, cholesterol can also reduce the permeability of liposomal bilayers. For instance, addition of cholesterol in liposomes resulted in increased free energy barriers of the membranes, which were primarily responsible for the reduced water permeability [9]. For anti-cancer drug delivery, reduced permeability of lipid membranes should reduce leakage of enclosed drugs during circulation, minimizing side effects and improving bioavailability of drugs. For vaccine delivery, in addition to the reduced loss of vaccine effector molecules, the bi-directionally lowered permeability should also minimize interactions between antigenic proteins and external water molecules or serum proteinases, avoiding their premature degradation.

In this study, lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs of various cholesterol concentrations were prepared to evaluate the influence of cholesterol content on the stability of long-term stored hybrid NPs, the release of a model antigen, bovine serum albumin (BSA), from NPs in human serum and PBS buffer, and in vitro uptake of NPs by dendritic cells (DCs). DSPE-PEG(2000) amine was later introduced into lipids to reduce aggregation of hybrid NPs at higher concentrations of cholesterol.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Lactel® 50:50 PLGA was purchased from Durect Corporation (Cupertino, CA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) recombinant mouse protein, alpha minimum essential medium, trypsin/EDTA, Alexa Fluor® 647 hydrazide, and tris(triethylammonium) salt were purchased from Life Technologies Corporation (Grand Island, NY). Lipids, including 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (ammonium salt) ((DSPE-PEG(2000)) amine), cholesterol, and 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(7-nitro-2-1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-yl) (ammonium salt) (NBD PE) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. (Alabaster, AL). Poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA, MW 89,000–98,000), dichloromethane (DCM), rhodamine B (Rhod B), and BSA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (Saint Louis, MO). 1-Ethyl-3-[3-dimethylaminopropyl] carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (Rockford, IL). JAWSII (ATCC® CRL-11904™) immature dendritic cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

2.2. Synthesis of BSA-containing PLGA NPs

PLGA NPs were prepared using a reported double emulsion solvent evaporation method with modifications [10]. Briefly, PLGA (100 mg) was dissolved in DCM (3 mL), followed by mixing with 500 μL of BSA (10 mg/mL) for 2 min using a vortex (in the study of uptake of hybrid NP by DCs using TEM, BSA was replaced with iron NP). The resultant mixture was emulsified in Branson B1510DTH Ultrasonic Cleaner (Branson, Danbury, CT) for 10 min. The primary emulsion was added drop-wise into 100 mL PVA (1% (w/v)), and continuously stirred for 10 min at 500 rpm. The above suspension was emulsified through sonication using a sonic dismembrator (Model 500; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA) at 50% amplitude for 120 s. The secondary emulsion was stirred overnight to allow DCM to evaporate. Large particles were removed after the mixture sat undisturbed at room temperature for 30 min. NPs in suspension were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 g, 4 °C for 60 min using an Eppendorf centrifuge. (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY). The pellet was washed 3 times using ultrapure water. The final suspension was freeze-dried using LABCONCO Freezone 4.5 (LABCONCO Kansas City, MO), and NPs were stored at 2 °C for later use. For measurement of encapsulation efficiency of BSA by PLGA NPs, various amounts of BSA (0.5 mg, 1 mg, 5 mg, and 10 mg) were emulsified with 100 mg of PLGA. After the second emulsion, non-encapsulated BSA in PVA solution were separated from PLGA-entrapped BSA through centrifugation at 10,000 g, 4 °C for 60 min, and the concentration of BSA in PVA solution was measured using the Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY). Encapsulation efficiency was calculated using the follow equation: Encapsulation efficiency (%)= [(BSA (mg) initially added-Concentration of BSA in PVA solution (μg/mL)*100 mL*0.001)/BSA (mg) initially added]*100.

2.3. Assembly of lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs

A lipid film (10 mg) containing the lipids identified above was hydrated with 10 mL, 55 °C pre-warmed phosphate buffered saline (PBS) buffer. The resulted liposome suspension was vigorously mixed using a vortex for 2 min, followed by 5 min sonication using a Branson B1510DTH Ultrasonic Cleaner (Branson, Danbury, CT) and cooling to room temperature. PLGA NPs (50 mg) were added into the liposome suspension and pre-homogenized for 15 min using a Branson B1510DTH Ultrasonic Cleaner, followed by 5 min sonication in an ice bath using a sonic dismembrator at 15% amplitude (pulse on 20 s, pulse off 50 s). The formed lipid-PLGA NPs were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 g, 4 °C for 60 min, lyophilized, and stored at 2 °C.

2.4. Labeling BSA with rhodamine B (Rhod B) or Alexa Fluor® 647 Hydrazide

The coupling of fluorescent dyes to BSA was done using a method described in a previous study [11]. Ten mg of EDC dissolved in 700 μL ultrapure water (pH 6.8) were mixed with 300 μL of 2 mg/mL Rhod B. After incubation at 0 °C for 10 minutes, the product was mixed with 10 mg BSA (20 mg/mL) and stirred in darkness at room temperature for 6 h. For Alexa Fluor® 647 Hydrazide labeling, 10 mg of EDC in 800 μL ultrapure water (pH 6.8) was incubated with 10 mg BSA (20 mg/mL) at 0 °C for 10 minutes, followed by reaction with 100 μg Alexa Fluor® 647 Hydrazide in darkness at room temperature for 6 h. Fluorescently labeled BSA was purified using Microcon centrifugal filter units (10,000 MWCO, EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), freeze-dried, and stored at 2 °C.

2.5. Characterization of physicochemical properties of NPs

One mg of NPs was dispersed in 5 mL ultrapure water (pH 7.0), and each sample was diluted by 10 fold using ultrapure water, before the particle size (diameter, nm) and surface charge (zeta potential, mV) were measured at room temperature using a Malvern Nano-ZS zetasizer (Malvern Instruments Ltd, Worcestershire, United Kingdom).

2.6. In vitro BSA release from NPs in human serum and PBS buffer

Ten mg of lipid-PLGA NPs containing Rhod B-labeled BSA were suspended in 10 mL (5% v/v) human plasma (pH 7.4) and continuously stirred at room temperature in darkness. After 24 h incubation, the NPs were centrifuged at 10,000 g, 4 °C for 60 min. The supernatant was transferred to a 50 ml tube, and the NP pellet was suspended in 10 mL (5% v/v) human plasma (pH 7.4). Two hundred μL of supernatant or NP suspension was added into wells of a black 96-well plate, and the fluorescence intensity was measured using a Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT) with excitation at 530 nm and emission at 590 nm. The percentage of released BSA in human serum was calculated using the following equation: BSA released (%) =Fluorescence intensity (supernatant)/[Fluorescence intensity (supernatant) + Fluorescence intensity (pellet suspension)] × 100. For measurement of BSA release in PBS buffer, 20 mg of lipid-PLGA NPs, with enclosed Rhod B-labeled BSA, were suspended in 20 mL PBS buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature in darkness, and the released BSA was separated from NPs via centrifugation at 10,000 g, 4 °C for 60 min at indicated time points. The NPs were re-suspended in PBS buffer and fluorescence intensity of 200 μL of the released BSA in supernatant was measured using a Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT) with excitation at 530 nm and emission at 590 nm. Meanwhile, as a control group, 20 mg of the above Rhod B-labeled BSA containing lipid-PLGA NPs were suspended in 20 mL PBS buffer (pH 7.4), and the fluorescence intensity of 200 μL of the suspension was measured using the method described above. The percentage of released BSA at given time points was calculated using the following equation: BSA released (%) = Fluorescence intensity (supernatant)/Fluorescence intensity (control) × 100.

2.7. Imaging NPs using transmission electrical microscopy (TEM)

NP suspensions (1 mg/mL) were dropped onto a 300-mesh Formvar-coated copper grid. After standing 10 min, the remaining suspension was carefully removed with wipes, and the samples were negatively stained using fresh 1% phosphotunstic acid for 20 s and washed with ultrapure water twice. The dried samples were imaged on a JEOL JEM 1400 Transmission Electron Microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

2.8. Imaging hybrid NPs using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM)

A Zeiss LSM 510 Laser Scanning Microscope (Carl Zeiss, German) was used to image lipid-PLGA NPs containing Alexa Fluor® 647 Hydrazide labeled BSA and NBD PE labeled lipid shells.

2.9. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis of NPs

The spectrum of freeze-dried (i) liposomes with a molar ratio of DOTAP: DSPE-PEG(2000) amine: cholesterol = 80%: 5% : 15%, (ii) PLGA NPs, and (iii) lipid-PLGA NPs with a molar ratio of DOTAP: DSPE-PEG(2000) amine: cholesterol = 80%: 5% : 15% were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet 6700 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). The spectrum was taken from 4000 to 400 cm−1.

2.10. Flow cytometry measurement of endocytosis of lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs by dendritic cells (DCs)

JAWSII (ATCC® CRL-11904™) immature DCs from ATCC were cultured with alpha minimum essential medium (80%v) including ribonucleosides, deoxyribonucleosides, 4 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 5 ng/mL murine GM-CSF, along with fetal bovine serum (20%v) at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in 24 well plates (CORNING, Tewksbury, MA). Alexa Fluor® 647 Hydrazide-labeled lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs of varied lipid compositions were assembled according to the above mentioned method. Two hundred μg of NPs were added into each well containing 2×106 cells, and incubated for 90 min. After incubation, the medium was immediately removed and cells were washed 5 times with ultrapure water. Cells were detached from culture plate using trypsin/EDTA solution and centrifuged at 200 g for 10 min, before cell pellets were re-suspended in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4). Cell samples were immediately analyzed by flow cytometry (BD FACSAria I, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

2.11. Imaging endocytosis of lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs by DCs using CLSM

Cells were cultured in a 4 well chamber slide (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rd, Rockford, IL) using the same method described above. To investigate the effect of the content of cholesterol on the uptake of hybrid NPs by DCs, 100 μg of freshly made hybrid NPs (labeled with Alexa Fluor® 647 Hydrazide) were incubated with 3×105 cells for 5 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. To study the influence of content of DSPE-PEG(2000) amine on endocytosis of hybrid NPs (stored in pH 7.4 PBS for 30 days) by DCs, 100 μg hybrid NPs (labeled with both NBD PE and Alexa Fluor® 647 Hydrazide) were incubated with 3×105 cells for 30 min at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After incubation, the medium was immediately removed and cells were washed 5 times with ultrapure water. Freshly prepared 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (500 μL) was added into each well, and cells were fixed for 15 min. This was followed by washing 3 times with PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4). Fixed cells were permeabilized using 500 μL of 0.1% (v/v) Triton™ X-100 for 15 min at room temperature, and washed 3 times using PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4). Cell samples were covered with a glass cover and sealed by nail polish. Images were acquired using a Zeiss LSM 510 Laser Scanning Microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany).

2.12. Imaging endocytosis of lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs in DCs using transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

To view the uptake of hybrid NPs, which contained various concentrations of cholesterol, petri dishes containing 2×106 immature DCs were supplemented with 200 μg of hybrid NPs. After 90 min incubation, the medium containing un-internalized NPs was removed and cells were washed 5 times with ultrapure water. Cell samples were prepared for TEM using the following procedure: cells were washed 2 times in 0.1 M Na-Cacodylate for 15 minutes each, and then post-fixed in 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M Na-Cacodylate for one hour. OsO4 was discarded, and the samples were washed 2 times for 10 minutes each in 0.1 M Na-Cacodylate. Cell samples were dehydrated in solutions containing increasing ethanol concentration of 15%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 95%, and 100% (15 minutes in each ethanol solution). Dehydration was completed by submerging cell samples in propylene oxide for 15 minutes. Cells were infiltrated with a 50:50 solution of propylene oxide:Poly/Bed 812 for 6–24 hours, then embedded using freshly prepared 100% Poly/Bed 812 in flat embedding molds, and placed in a 60 °C oven for at least 48 hours to cure. Images were acquired using a JEOL JEM 1400 Transmission Electron Microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

2.13. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in at least triplicate. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Tests for significance were conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test (JMP pro 10). Differences were considered significant at P-values that were less than or equal to 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

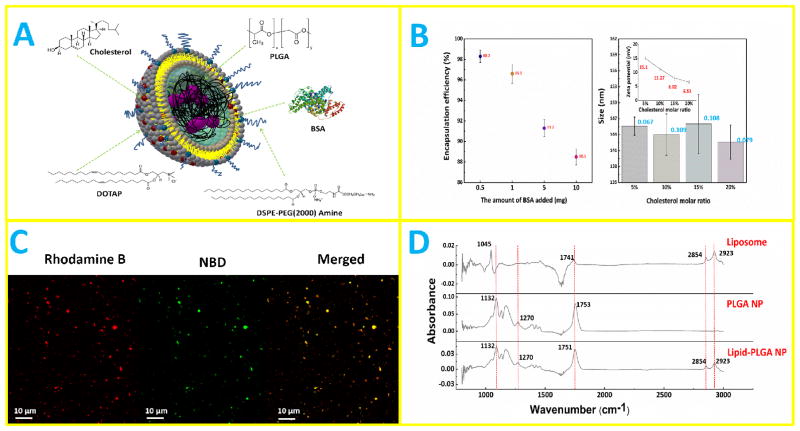

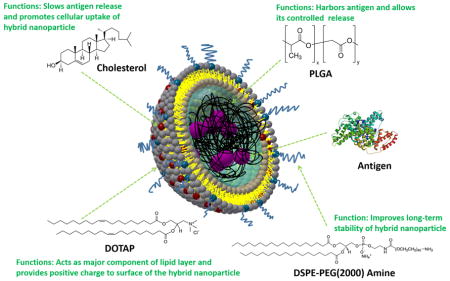

3.1. Fabrication of lipid-PLGA NPs

As shown schematically in Fig. 1A, lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs consisted of a PLGA core, in which BSA as a model antigen was encapsulated, and a lipid layer composed of DOTAP, DSPE-PEG(2000) amine, and cholesterol. Fabrication of lipid-PLGA NPs was performed in two steps. In the first step, PLGA NPs were formed using a widely applied double emulsion and evaporation method [12]. Enclosing antigen into PLGA nanoparticle using ultrasonication is a common approach. Previous studies have demonstrated that this approach does not jeopardize the immunological properties of the enclosed antigens [13]. In addition, a study was specifically conducted to investigate whether ultrasonication would impair the stability of BSA in PLGA nanoparticles, and the results obtained showed that there was no apparent effect of the drastic encapsulation conditions (contact with dichloromethane (DCM), probe sonication, and vigorous shaking) on the structural integrity of the protein [14]. Various amounts of BSA (0.5 mg, 1 mg, 5 mg, and 10 mg) were emulsified with 100 mg PLGA, and the encapsulation efficiency of BSA was measured. As shown in Fig. 1B, encapsulation efficiency amounted to 98.3% when 0.5 mg of BSA was added, and although encapsulation efficiency dropped as the amount of added BAS increased, it was still as high as 88.5% when 10 mg of BSA was added. High encapsulation efficiency is of particular importance for drug or vaccine delivery, because lower amount of NPs is needed to carry certain cargo quantities. It could reduce the potential side effects of NPs, increase treatment efficacy, and lower the overall production cost. In the second step, liposomes consisting of a given molar ratio of lipids were hybridized with PLGA NPs via sonication-aided fusion. The size and zeta potential of hybrid NPs containing various molar ratios of cholesterol (cholesterol ranged from 5% to 20%; the remaining lipid was DOTAP) were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 1B, sizes of all hybrid NPs are around 144 nm, largely attributable to the size of PLGA NPs (the size of PLGA NPs formed using the above mentioned method was around 120 nm). It is worth noting that the polydispersity indexes (shown with blue numbers in Fig. 1B) of all hybrid NPs are very low, indicating that the sizes of hybrid NPs were narrowly distributed and the aforementioned methods for NP fabrication were highly robust. Zeta potential of hybrid NP decreases with the increased concentration of cholesterol, which can be explained by the decreased concentration of positively charged DOTAP in the lipid layer. Nevertheless, even at a cholesterol molar ratio of 20%, the surface of the hybrid NP is still positively charged, which is indicated by the positive value of zeta potential. It has been reported that positively charged NPs were taken up by cells with higher efficiency compared with neutral NPs or those with negative surface charges [15, 16]. To confirm that a hybrid structure was successfully formed, hybrid NPs, in which PLGA core was labeled with Rhod B (red color) and a lipid layer that was labeled with NBD PE (green color), were imaged using confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1C, hybrid NPs display both red color and green color, indicating that PLGA NPs and liposomes were indeed hybridized. Moreover, the vast majority of NPs in Fig. 1C are hybrid NPs, implying the high efficiency of hybridization achieved by the sonication-aided fusion. In addition, by comparing the FTIR spectra of liposomes, PLGA NP, and hybrid NP, liposomes and hybrid NPs evidently share peaks at wavenumbers of 2854 cm−1 and 2923 cm−1, and PLGA NPs show the same peaks at wavenumbers of 1270 cm−1 and 1132 cm−1 as hybrid NPs, further demonstrating that the lipid layer was coated onto the PLGA core.

Fig. 1. Synthesis of lipid-PLGA NPs.

(A) A 3D schematic illustration of the structure of lipid-PLGA NPs showing a lipid layer around a BSA core. (B) (Left graph) encapsulation efficiency of BSA at varied amounts (0.5 mg, 1 mg, 5 mg, and 10 mg) by 100 mg PLGA NPs; (right graph) size and zeta potential of lipid-PLGA NPs containing various molar ratios of cholesterol in the lipid layer (5%, 10%, 15%, 20%). (C) Confocal micrograph of lipid-PLGA NPs, in which lipid layer was labeled with NBD PE (green color) and PLGA core encapsulated Rhod B (red color) stained BSA. The merged image shows that PLGA NPs and liposomes were hybridized (D) FTIR spectra of liposome, PLGA NP, and lipid-PLGA NP. Liposomes and hybrid NPs share peaks, demonstrating that the lipid layer was coated onto the PLGA core.

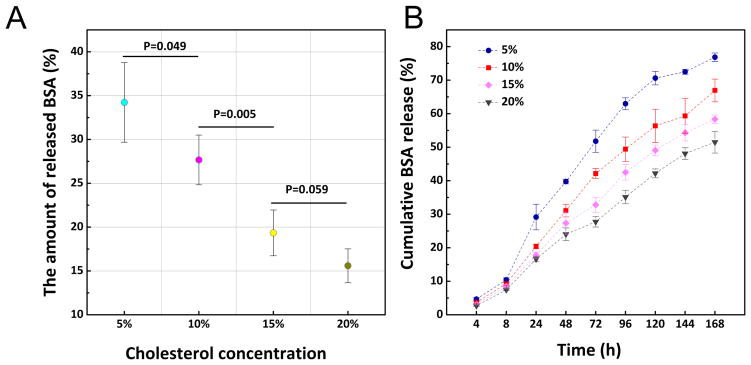

3.2. In vitro release of BSA from hybrid NPs in human serum and PBS buffer

It has been reported that a lipid layer can act as a molecular fence and contribute to keeping anti-cancer drug molecules in a PLGA core while keeping H2O out of the core, decreasing hydrolysis of the PLGA polymer as well as decreasing erosion and undesired drug release [17]. In this study, to investigate how cholesterol concentration in the lipid layer of hybrid NPs influences their performance and subsequent antigen release, hybrid NPs containing a range of cholesterol concentrations (5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%) were fabricated. BSA as a model antigen was enclosed in the PLGA core. Performance of NPs in human serum is an important criterion for their application as a vaccine delivery vehicle in vivo. In human serum, the amount of released BSA was inversely correlated with cholesterol concentration (Fig. 2A). At 5% cholesterol, 34.2% of BSA was released from NPs in 24 h. However, the amount of released BSA was significantly reduced to 27.7% when cholesterol concentration was increased by 5%. At 20% cholesterol level, only 15.6% of BSA was released from NPs. Early studies demonstrated that incorporation of cholesterol in a liposome formulation could remarkably increase the stability and reduce the permeability of liposomal bilayers [18, 19]. In this study, the decreased BSA release in serum from hybrid NPs with higher cholesterol content was probably resulted from slowed diffusion of BSA out of the lipid layer as well as reduced influx of water and serum enzymes into the PLGA core. To compare long-term antigen release among NPs without the confounding factors associated with incubation in serum, hybrid NPs formulated with various concentrations of cholesterol were incubated in PBS buffer. The antigen release profiles (Fig. 2B) show that the rate of BSA release is also reversely correlated with the concentration of cholesterol in the lipid layer. Although sustained BSA release profiles were observed among all tested hybrid NPs, slower and steadier BSA release was achieved by hybrid NPs with higher cholesterol concentrations. After 168 h of incubation in PBS buffer, 51.5% BSA was released from NPs containing 20% cholesterol in its lipid layer. In contrast, 76.8% of BSA was released from NPs with 5% cholesterol, demonstrating a significant impact of cholesterol on retaining antigen in hybrid NPs. Compared to that in PBS buffer, the BSA release rate in human serum was slightly faster. The difference might be attributed to the serum enzymes and proteins that can expedite degradation of the hybrid nanoparticle.

Fig. 2. Release of BSA from lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs.

(A) The release of BSA from hybrid NPs containing various concentrations of cholesterol in lipid layer after incubation in human serum (5% v/v) for 24 h at room temperature. Higher concentrations of cholesterol decreased BSA release. (B) The release profile of BSA from hybrid NPs, which were suspended in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature.

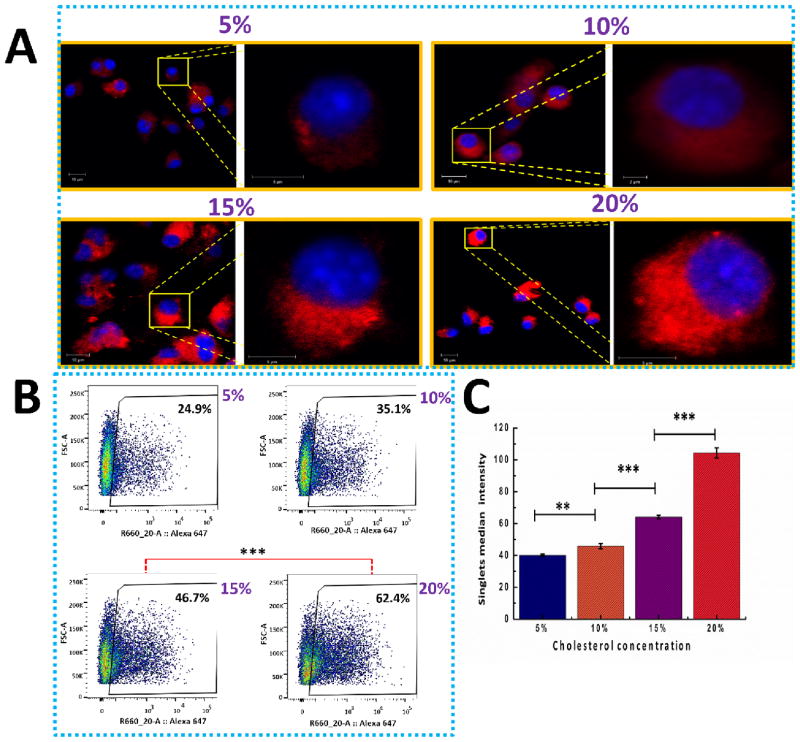

3.3. In vitro uptake into DCs of hybrid NPs with varied cholesterol concentrations

To understand how cholesterol concentration in the lipid layer affects the uptake of lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs by DCs, freshly produced hybrid NPs containing different molar ratios of cholesterol (5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%) in the lipid layer were added to DCs. The in vitro cellular uptake of hybrid NPs by DCs was investigated using confocal microscopy and flow cytometry. In Fig. 3A, fluorescence from the hybrid NPs (labeled with Rhod B) internalized in DCs (nucleus was labeled with DAPI, which displays a blue color) is shown. Qualitative examination of the CLSM images of cellular uptake demonstrated that red fluorescence with wider distribution and brighter color was observed in DCs treated with hybrid NPs containing higher concentrations of cholesterol. This suggests that increasing cholesterol concentration in the lipid layer could remarkably enhance the internalization of hybrid NPs by DCs. A quantitative study of cellular uptake was performed by measuring the percentage of DCs that internalized hybrid NPs (Alexa 647 labeled) as well as the fluorescence intensity of NPs internalized into DCs after incubating 200 μg of NPs with 2×106 cells for 90 min. As shown in Fig. 3B, 24.9%, 35.1%, 46.7%, and 62.4% of DCs have entrapped hybrid NPs with cholesterol concentrations of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%, respectively. The significant increase in the number of DCs that internalized NP at higher cholesterol concentrations demonstrates that increasing cholesterol content in the lipid layer could considerably facilitate the uptake of hybrid NPs by DCs. It has been proposed that in vitro cellular uptake of lipid-polymer hybrid NPs was mediated by carrier endocytosis and cell fusion [20]. In this study, the enhancing effect of cholesterol on cellular uptake may result from the fact that cholesterol can improve the stability of the lipid bilayer [21], and the improved integrity of the hybrid structure promotes NP uptake by DCs. In addition, as shown in Fig. 3C, increasing cholesterol concentrations resulted in significantly higher fluorescent intensities in DCs, suggesting that more NPs of higher cholesterol content were internalized. Analysis of the fluorescence intensity demonstrates that DCs internalized 150% more hybrid NPs of 20% cholesterol concentration than NPs of 5% cholesterol concentration.

Fig. 3. Investigation of endocytosis of freshly made hybrid NPs by DCs using CLSM and flow cytometry.

Increasing cholesterol concentrations resulted in significantly higher fluorescent intensities in DCs, suggesting that more NPs of higher cholesterol content were internalized. (A) Confocal microscopic image of the uptake of hybrid NPs consisting of various molar ratios (5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%) of cholesterol by DCs. 100 μg of Rhod B stained hybrid NP were incubated with 3×105 DCs for 5 h. The scale bars in all lower magnification images are 10 μm. (B) Flow cytometry study on the percentage of cells that had taken up the above mentioned hybrid NPs. 200 μg of Rhod B labeled NPs were cultured with 2×106 DCs for 90 min. (C) Singlet median intensity of the DCs that had endocytosed hybrid NPs with various molar ratios of cholesterol in lipid layer. ** denotes that P-value is less than 0.05, *** denotes that P-value is less than 0.01.

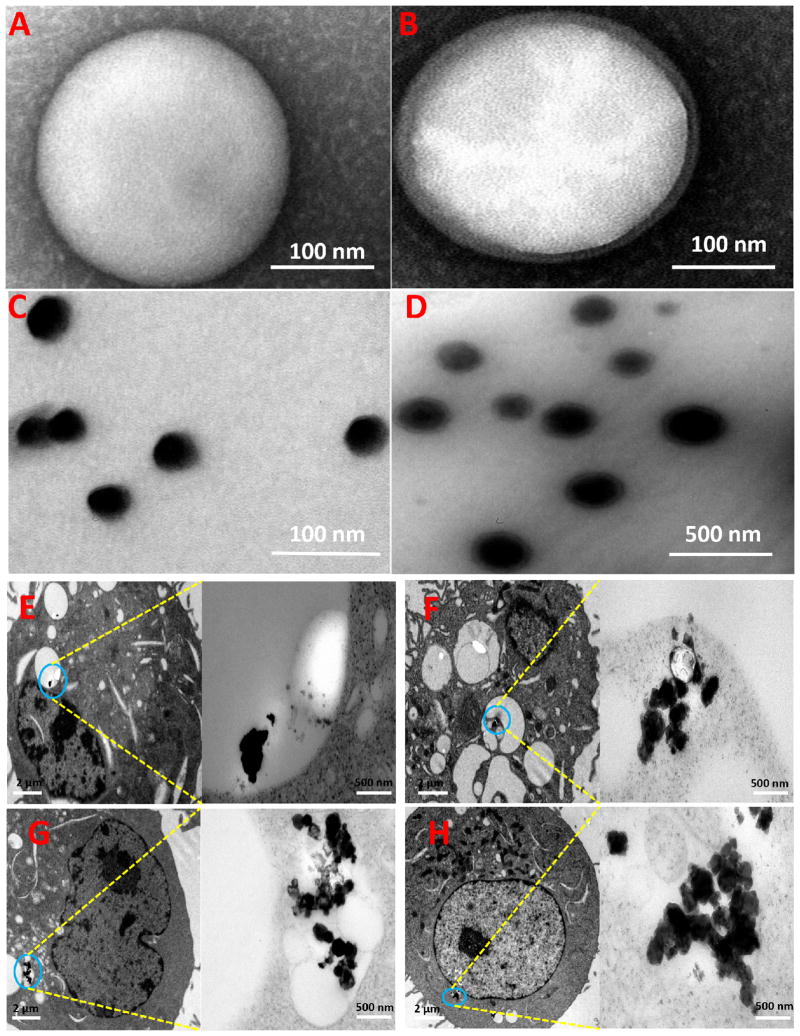

Cellular uptake of hybrid NPs of various cholesterol contents was further examined with TEM. In order to increase the contrast of TEM image and better locate distribution of NPs in DCs, iron NPs were encapsulated in lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs. In addition to the physiochemical characterization of hybrid NP in Fig. 1, the morphologies of PLGA NP and lipid-PLGA hybrid NP were studied using TEM. A representative TEM image of PLGA NP is shown in Fig. 4A. The NP is of a spherical shape with a diameter around 160 nm, and the particle surface is smooth. In previous studies, we have extensively investigated the morphology of liposome using TEM [11, 22]. We found that liposomes with desirable sizes could be readily formed using dehydration-rehydration method. As shown in Fig. 4B, although the size and morphology of lipid-PLGA hybrid NP are highly similar to that of PLGA NP, one lipid layer with thickness of 10–20 nm is seen to closely surround the PLGA core. The comparison of Fig. 4A and Fig. 4B clearly shows that PLGA NP was perfectly hybridized with liposome. Iron NPs (as shown in Fig. 4C) with a diameter of 30 nm were encapsulated in PLGA NPs. After hybridization with liposome, PLGA NPs including iron NPs were incorporated with a lipid layer (Fig. 4D). Consistent with Fig. 4B, a lipid layer can be distinctively observed in iron enclosed lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs. After incubating 2×106 DCs with 200 μg of iron containing lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs of varying lipid compositions for 90 min, uptake of NPs by DCs was viewed using TEM. As shown in Fig. 4E–H (from Fig. 4E to Fig. 4H, the cholesterol content in lipid layers was 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%, respectively), DCs internalized different amounts of hybrid NPs depending on the cholesterol concentration. Consistent with the results from confocal imaging and flow cytometry, TEM images of cellular uptake show that more NPs with higher cholesterol content were internalized by DCs. Remarkably, regardless of lipid composition, all the NPs were enclosed inside endosomes after uptake by cells. From an immunological perspective, such a location of NPs in DCs is beneficial to trigger immune response, especially for inducing humoral response. In endosomes, antigens can be processed by proteinases into antigenic peptides, which are further presented to T helper cells [23]. It is to be noted that the lipid layer of hybrid NP with 5% cholesterol was no longer detected in NPs after internalization by DCs, but in other hybrid NPs with higher cholesterol content, a lipid layer surrounding NPs could still be observed after endocytosis. It is likely that the lipid layer with higher cholesterol content was more stable and able to maintain the core-shell structure during their entrance into DCs.

Fig. 4. TEM images of NPs and cellular uptake of NPs.

(A) PLGA NP, (B) lipid-PLGA hybrid NP, (C) iron NP, (D) lipid-PLGA hybrid NP with enclosed iron NP, (E-H) dendritic cell uptake of iron containing lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs, which have different molar ratios of cholesterol (5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%). 2×106 immature DCs were incubated with 200 μg of hybrid NPs for 90 min. DCs internalized different amounts of hybrid NPs depending on the cholesterol concentration.

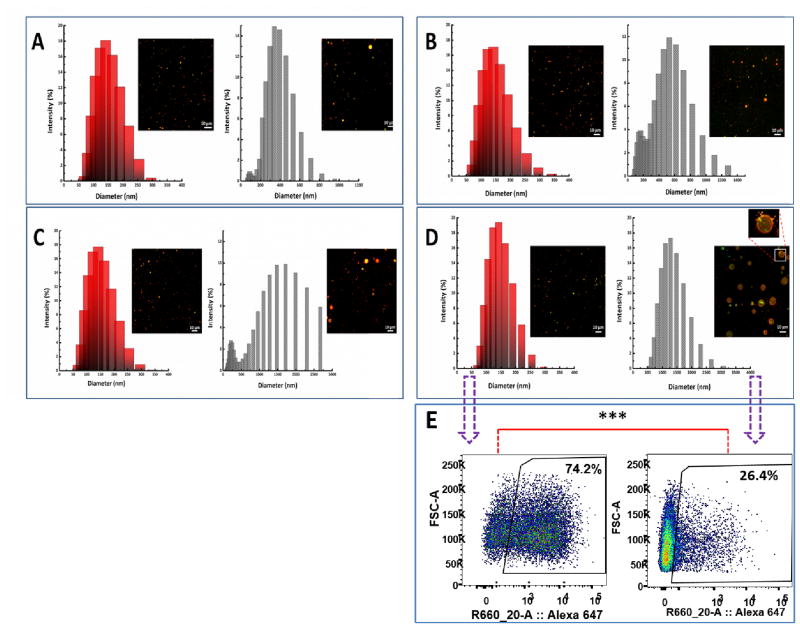

3.4. Stability of hybrid NPs in PBS buffer at 4 °C for 30 days

To assess how cholesterol content could affect long-term stability of hybrid NPs, NPs of varied cholesterol concentrations (5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%) were stored in PBS buffer (pH 7.4, 5 mg/mL) at 4 °C for 30 days, and the size distribution and confocal morphology of the NPs were studied before and after storage. As shown in Fig. 5 A–D, size distributions of all the NPs shifted to the right after 30 days of storage, indicating a general trend toward size increase. It appears that the extent of size increase was correlated with cholesterol content in the lipid layer. For example, the initial central peak of all the NPs was around 150 nm, and after storage, it changed to 300 nm, 500 nm, 1500 nm, and 1250 nm for NPs with cholesterol content of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%, respectively. The size increase of NPs may result from aggregation or fusion of NPs. This assumption was confirmed by analysis of the confocal image of NPs after storage. As shown in the magnified confocal image in Fig. 5D, many small NPs are distributed around and merging with a NP of much bigger size, suggesting that bigger NPs were formed by fusion of smaller NPs. A closer examination of the confocal images of the stored NP revealed that the number of visible NPs decreased with the decrease in cholesterol content in the lipid layer. It is likely that the lipid layer of hybrid NPs with lower cholesterol concentration was not stable, and might disintegrate from the PLGA core over time of storage. PLGA NPs without the protection from a lipid layer can be hydrolyzed more rapidly compared to those shelled with lipid layer, leading to disappearance of previously visible particles. For example, early study on PLGA degradation showed that the half-lives of PLGA structures were less than 4 weeks [24]. The degradation of NPs of lower cholesterol content might result in lower number of visible NPs as well as lead to a reduction in the chance of forming larger NPs. Although NPs with higher cholesterol content were more stable in terms of structural integrity compared to those with lower cholesterol content, the considerable size increase might interfere with antigen delivery. As shown in Fig. 5E, analysis of cellular uptake of NPs with 20% cholesterol content demonstrates that 74.2% of the cell internalized newly prepared NPs in 90 min. In contrast, only 26.4% of cells took up the stored NPs, suggesting that long-term stored NPs with higher cholesterol content may not perform ideally as a vaccine carrier unless the size increase can be minimized.

Fig. 5. Stability of hybrid NPs of different cholesterol content in PBS at 4°C for 30 days.

Size distributions of hybrid NPs were measured before (red columns) and after (grey columns) storage in PBS, and the corresponding confocal images of hybrid NPs were taken. (A) NPs with 5% cholesterol in total lipid content. (B) NPs with 10% cholesterol. (C) NPs with 15% cholesterol. (D) NPs with 20% cholesterol. (E) Cellular uptake of newly prepared NP containing 20% cholesterol and NPs stored for 30 days. The number of visible NPs decreased with the decrease in cholesterol content in the lipid layer over time. Scale bars in confocal images represent 10 μm.

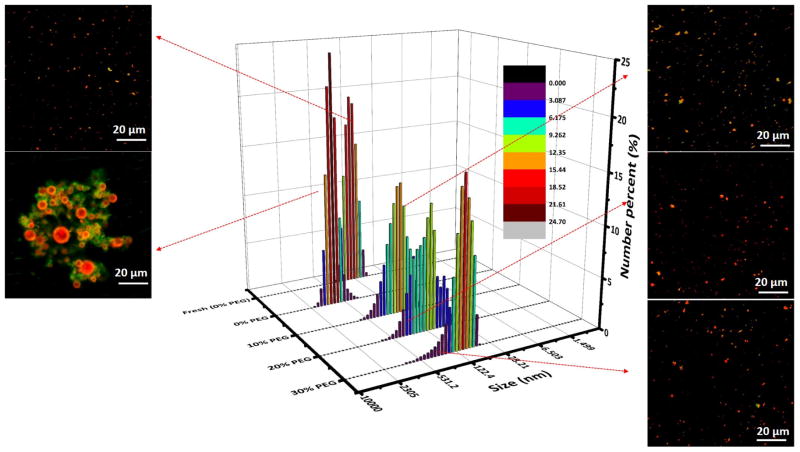

3.5. Minimization of the fusion effect among hybrid NPs through PEGylation

As discussed in the previous section, high concentration of cholesterol in the lipid layer was beneficial to maintaining the integrity of the hybrid structure of NPs. However, an intact lipid shell increased the chance of fusion between NPs, leading to increased particle size and decreased cellular uptake. Therefore, it is necessary to engineer the high cholesterol content hybrid NPs to be fusion resistant. PEGylation has been reported as one of the most successful strategies to improve the delivery of many therapeutic molecules such as proteins, macro-molecular carriers, small drugs, oligonucleotides, and other biomolecules [25]. PEGylation has also been widely used as a stabilizing process for many NP formulations, such as dendrimers and liposomes [26]. It is possible that the steric hindrance offered by PEG molecules may mitigate the fusion problem of lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs. Therefore, in this study, hybrid NPs containing 20% cholesterol were incorporated with various molar ratios (10%, 20%, and 30%) of DSPE-PEG(2000) amine in lipid layer. The zeta potentials were 5.58±0.33 mV, 5.07±0.21 mV, and 4.78±0.22 mV for NPs with PEGylation degree of 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively. The decreasing zeta potential of NPs with increasing degree of PEGylation indicates that PEGylation may shield some positive charges from DOTAP. The size distributions and confocal images of polyethylene glycol (PEG) engineered hybrid NPs were analyzed after 30 days’ storage at 4 °C in PBS buffer. As shown in Fig. 6, the size distributions of PEGylated NPs remained closer to that of newly made hybrid NPs compared to that without PEG, indicating that PEGylation could markedly reduce the fusion problem of hybrid NPs during storage. Confocal images of NPs in Fig. 6 also show that no marked size increase were detected among NPs containing DSPE-PEG(2000) amine compared to newly made NPs. Size distribution of NPs was also related to the concentration of PEG in the lipid layer, and hybrid NPs containing a higher percentage of PEG exhibited less size distribution when compared to newly made NPs.

Fig. 6. Impact of DSPE-PEG(2000) amine on the size distribution of NPs after 30 days’ storage at 4 °C.

Hybrid NP containing 20% cholesterol in lipid layer were introduced with a range of concentrations (10%, 20%, and 30%) of DSPE-PEG(2000) amine. The smaller pictures on both sides of size distribution were confocal images of NPs labeled with NBD and Rhod B. The colors in confocal images were a result of combination of NBD and Rhod B. No marked size increase were detected among NPs containing DSPE-PEG(2000) amine compared to newly made NPs. The scale bars represent 20 μm.

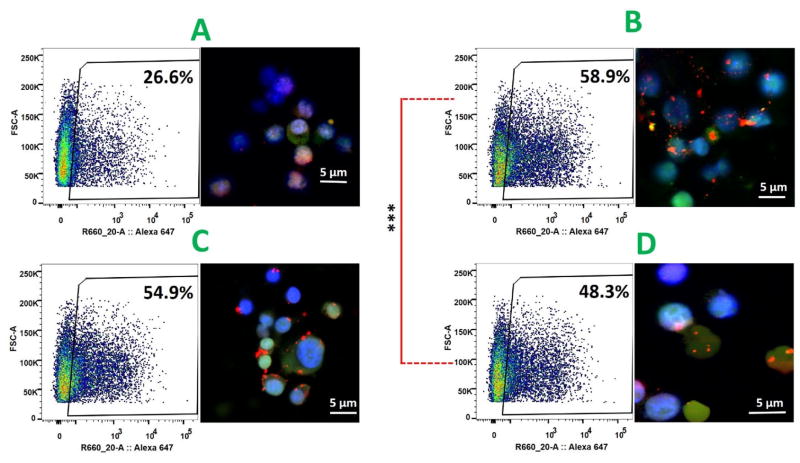

3.6. Influence of PEGylation of hybrid NPs on cellular uptake of NPs

The ultimate goal of introducing DSPE-PEG(2000) amine into the lipid layer was to minimize fusion-caused size increases of NPs, thereby improving uptake of NPs by DCs. To evaluate the effect of PEGylation of NP on cellular uptake, PEGylated NPs after 30 days storage in PBS buffer (5 mg/mL) were mixed with DCs, and internalization of NPs were studied with flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. As shown by flow cytometry data in Fig. 7, after 90 min treatment, 26.6%, 58.9%, 54.9%, and 48.3% of the cells internalized NPs with PEG concentration of 0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%, respectively. The high cellular uptake of PEGylated NPs in a short period of time demonstrates that PEGylated NPs could be rapidly internalized by DCs to minimize antigen loss during circulation and improve antigen utilization efficiency. Confocal microscopic pictures also demonstrate that considerably higher quantities of PEGylated NPs were taken up by DCs compared to non-PEGylated NPs. These results indicate that PEGylation of hybrid NPs could effectively improve cellular uptake of stored NPs. It is very likely that the improved endocytosis of NPs resulted from the relatively unchanged size distribution of PEGylated NPs, because DCs preferably internalize nanoparticles with sizes between 20 nm and 100 nm [27]. However, it should be noticed that among those PEGylated NPs, higher level of PEGylation led to decreased cellular uptake. The percentage of cells that internalized NPs significantly dropped from 58.9% to 48.3% when PEGylation level was raised from 10% to 30%. The decreased cellular uptake of NPs with higher PEG concentration implies that PEGylation of NPs is a double-edged sword: on one hand it can stabilize NPs, but on the other hand, it can impede the interaction between NPs and cells, decreasing cellular uptake efficiency.

Fig. 7. Cellular uptake of PEGylated hybrid NPs.

Hybrid NPs containing 20% cholesterol and a range concentrations (0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%) of DSPE-PEG(2000) amine were stored in PBS at 4 °C for 30 days, and cellular uptake of these stored NPs were investigated using flow cytometry and confocal microscope. (A) NPs with 0% PEG, (B) NPs with 10% PEG, (C) NPs with 20% PEG, and (D) NPs with 30% PEG. Considerably higher quantities of PEGylated NPs were taken up by DCs compared to non-PEGylated NPs. Scale bars represent 5 μm.

4. Conclusion

Lipid-PLGA hybrid NPs with various cholesterol contents were fabricated, and a higher content of cholesterol in lipid layer was found to allow slower and more controlled antigen release in vitro, facilitate cellular uptake of NPs, and protect the integrity of the hybrid nanostructure. The increased particle uptake by dendritic cells may induce more rapid and stronger immune response against target antigen. In addition, higher cholesterol content resulted in slowed antigen release from nanoparticles in human serum, indicating that these particles may minimize antigen release during circulation, increasing the bioavailability of the antigen to immune cells. However, concentrated cholesterol in the lipid layer promoted fusion between hybrid NPs, resulting in significant size increase after long-term storage in PBS buffer, which impeded cellular uptake of NPs. To mitigate the fusion effect during storage, hybrid NPs were PEGylated. It was found that PEGylation of hybrid NPs could considerably minimize fusion-caused size increases for NPs of high cholesterol content. Subsequent study on cellular uptake of stored PEGylated NPs demonstrated that PEGylation could significantly increase internalization of NPs compared to non-PEGylated NPs stored for a similar period of time. However, the level of PEGylation has to be cautiously considered, because although higher concentrations of PEG in lipid layers may improve the long-term stability of hybrid NPs, it also can potentially increase steric hindrance between NPs and cells, undermining cellular uptake efficiency. The improved stability of nanoparticles by PEGylation is favorable for preserving the efficacy of vaccine which undergoes long-term storage.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (R21DA030083 and U01DA036850).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mandal B, Bhattacharjee H, Mittal N, Sah H, Balabathula P, Thoma LA, et al. Core-shell-type lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles as a drug delivery platform. Nanomedicine. 2013;9:474–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheow WS, Hadinoto K. Factors affecting drug encapsulation and stability of lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2011;85:214–20. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong HL, Bendayan R, Rauth AM, Wu XY. Simultaneous delivery of doxorubicin and GG918 (Elacridar) by new polymer-lipid hybrid nanoparticles (PLN) for enhanced treatment of multidrug-resistant breast cancer. J Control Release. 2006;116:275–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ling G, Zhang P, Zhang W, Sun J, Meng X, Qin Y, et al. Development of novel self-assembled DS-PLGA hybrid nanoparticles for improving oral bioavailability of vincristine sulfate by P-gp inhibition. J Control Release. 2010;148:241–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu CM, Kaushal S, Tran Cao HS, Aryal S, Sartor M, Esener S, et al. Half-antibody functionalized lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery to carcinoembryonic antigen presenting pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:914–20. doi: 10.1021/mp900316a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evjen TJ, Nilssen EA, Fowler RA, Rognvaldsson S, Brandl M, Fossheim SL. Lipid membrane composition influences drug release from dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine-based liposomes on exposure to ultrasound. Int J Pharm. 2011;406:114–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Needham D, Park JY, Wright AM, Tong J. Materials characterization of the low temperature sensitive liposome (LTSL): effects of the lipid composition (lysolipid and DSPE-PEG2000) on the thermal transition and release of doxorubicin. Faraday Discuss. 2013;161:515–34. doi: 10.1039/c2fd20111a. discussion 63–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali MH, Kirby DJ, Mohammed AR, Perrie Y. Solubilisation of drugs within liposomal bilayers: alternatives to cholesterol as a membrane stabilising agent. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2010;62:1646–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2010.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito H, Shinoda W. Cholesterol effect on water permeability through DPPC and PSM lipid bilayers: a molecular dynamics study. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:15241–50. doi: 10.1021/jp201611p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang YY, Chia HH, Chung TS. Effect of preparation temperature on the characteristics and release profiles of PLGA microspheres containing protein fabricated by double-emulsion solvent extraction/evaporation method. J Control Release. 2000;69:81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu Y, Zheng H, Huang W, Zhang C. A novel and efficient nicotine vaccine using nano-lipoplex as a delivery vehicle. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10:64–72. doi: 10.4161/hv.26635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar MR, Bakowsky U, Lehr C. Preparation and characterization of cationic PLGA nanospheres as DNA carriers. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1771–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danhier F, Ansorena E, Silva JM, Coco R, Le Breton A, Preat V. PLGA-based nanoparticles: an overview of biomedical applications. J Control Release. 2012;161:505–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igartua M, Hernandez RM, Esquisabel A, Gascon AR, Calvo MB, Pedraz JL. Stability of BSA encapsulated into PLGA microspheres using PAGE and capillary electrophoresis. International journal of pharmaceutics. 1998;169:45–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung TH, Wu SH, Yao M, Lu CW, Lin YS, Hung Y, et al. The effect of surface charge on the uptake and biological function of mesoporous silica nanoparticles in 3T3-L1 cells and human mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials. 2007;28:2959–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verma A, Stellacci F. Effect of surface properties on nanoparticle-cell interactions. Small. 2010;6:12–21. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chan JM, Zhang L, Yuet KP, Liao G, Rhee JW, Langer R, et al. PLGA-lecithin-PEG core-shell nanoparticles for controlled drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1627–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirby C, Clarke J, Gregoriadis G. Effect of the cholesterol content of small unilamellar liposomes on their stability in vivo and in vitro. Biochem J. 1980;186:591–8. doi: 10.1042/bj1860591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregoriadis G, Davis C. Stability of liposomes in vivo and in vitro is promoted by their cholesterol content and the presence of blood cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;89:1287–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)92148-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito J, Kato T, Kamio Y, Kato H, Kishikawa T, Toda T, et al. A cellular uptake of cis-platinum-encapsulating liposome through endocytosis by human neuroblastoma cell. Neurochem Int. 1991;18:257–64. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(91)90193-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson M, Omri A. The effect of different lipid components on the in vitro stability and release kinetics of liposome formulations. Drug Deliv. 2004;11:33–9. doi: 10.1080/10717540490265243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng H, Hu Y, Huang W, Villiers S, Pentel P, Zhang J, et al. Negatively Charged Carbon Nanohorn Supported Cationic Liposome Nanoparticles: A Novel Delivery Vehicle for Anti-Nicotine Vaccine. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2015;11:2197–210. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2015.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dudziak D, Kamphorst AO, Heidkamp GF, Buchholz VR, Trumpfheller C, Yamazaki S, et al. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science. 2007;315:107–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1136080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu L, Peter SJ, Lyman MD, Lai HL, Leite SM, Tamada JA, et al. In vitro and in vivo degradation of porous poly(DL-lactic-co-glycolic acid) foams. Biomaterials. 2000;21:1837–45. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milla P, Dosio F, Cattel L. PEGylation of proteins and liposomes: a powerful and flexible strategy to improve the drug delivery. Curr Drug Metab. 2012;13:105–19. doi: 10.2174/138920012798356934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryan SM, Mantovani G, Wang X, Haddleton DM, Brayden DJ. Advances in PEGylation of important biotech molecules: delivery aspects. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5:371–83. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bachmann MF, Jennings GT. Vaccine delivery: a matter of size, geometry, kinetics and molecular patterns. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:787–96. doi: 10.1038/nri2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]