Abstract

Impaired biosynthesis of Allopregnanolone (ALLO), a brain endogenous neurosteroid, has been associated with numerous behavioral dysfunctions, which range from anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors to aggressive behavior and changes in responses to contextual fear conditioning in rodent models of emotional dysfunction. Recent animal research also demonstrates a critical role of ALLO in social isolation. Although there are likely aspects of perceived social isolation that are uniquely human, there is also continuity across species. Both human and animal research show that perceived social isolation (which can be defined behaviorally in animals and humans) has detrimental effects on physical health, such as increased hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) activity, decreased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression, and increased depressive behavior. The similarities between animal and human research suggest that perceived social isolation (loneliness) may also be associated with a reduction in the synthesis of ALLO, potentially by reducing BDNF regulation and increasing HPA activity through the hippocampus, amygdala, and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), especially during social threat processing. Accordingly, exogenous administration of ALLO (or ALLO precursor, such as pregnenolone), in humans may help alleviate loneliness. Congruent with our hypothesis, exogenous administration of ALLO (or ALLO precursors) in humans has been shown to improve various stress-related disorders that show similarities between animals and humans i.e., post-traumatic stress disorders, traumatic brain injuries. Because a growing body of evidence demonstrates the benefits of ALLO in socially isolated animals, we believe our ALLO hypothesis can be applied to loneliness in humans, as well.

Keywords: Social neuroscience, Allopregnanolone, Pharmacological treatment, Social pain, Loneliness, Social Pain, Perceived Social Isolation

Introduction

Evolutionary model of loneliness

People often think about humans as unique compared to other species and ourselves as unique and independent relative to those around us. At first glance, other individuals certainly look distinct, independent, self-vicinities with no forces binding them together. We are, however, connected across our lifespan to one another, through a myriad of invisible forces that, like gravity, are ubiquitous and powerful [1-2]. Like other social species, we, humans, create emergent structures that extend beyond our own organism -- structures that range from couples and families to schools and nations and cultures. For our species to survive, infants must, for instance, instantly engage their parents in protective behavior, and the parents must care enough about these offspring to protect and nurture them. Even once grown, our survival depends on our collective abilities, not our individual might [3].

The superorganismal structures and processes that define social species are varied [4] but all have evolved hand in hand with neural, hormonal, and genetic mechanisms to support them because the consequent social behavior helps these organisms survive, reproduce and leave a genetic legacy. For a social species, including humans, to become an adult is not to become autonomous and solitary – it is to become a conspecific on whom others can depend [3]. Whether we are aware of it or not, our brain and biology have been shaped to favor this outcome. Across our biological heritage [5], our brain and biology have been sculpted to incline us to certain ways of feeling and behaving. For instance, we have a number of biological mechanisms that capitalize on aversive signals to motivate us to act in ways that are essential for our survival [3, 5-6]. Hunger, for instance, is triggered by low blood sugar, an important early and automatic warning signal that motivates you to eat. Similarly, thirst is an aversive signal that motivates you to search for drinkable water prior to fall victim to dehydration. Like hunger and thirst, loneliness (the aversive feeling of loneliness) is an aversive signal that motivates us to maintain, repair, or replace our social body, which members of a social species need to survive, prosper, and leave a genetic legacy [3, 5-9].

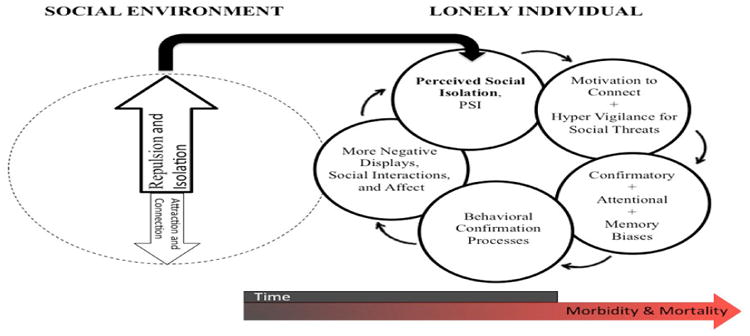

According to this evolutionary model of loneliness [5, 10-11], being on the social perimeter is not only sad it is dangerous. Accordingly, loneliness increases both an explicit motivation to connect with others an implicit motivation for self-preservation. Loneliness increases an automatic (non-conscious) hyper-vigilance for social threats, which then can introduce attentional, confirmatory, and memory biases, impulse control, and poor sleep salubrity [5, 10-14]. Given the effects of attention and expectation on anticipated social interactions, behavioral confirmation processes then can incline an individual who feels isolated to have or to place more import on negative social interactions, which if unchecked can reinforce withdrawal, negativity, and feelings of loneliness [10-12] (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Evolutionary model of loneliness, From [11].

In turn, loneliness can contribute to a constellation of health issues [e.g., 6-8, 11, 12, 15-26]. Human and animal research provides significant evidence that social species do not fare well when there is a discrepancy between the presence of a preferred and an actual conspecific – i.e., when perceived social isolation is relatively high (for reviews across phylogeny see [7, 8, 15]). The isolation from significant others has long been recognized as a risk factor for broad based morbidity and mortality. Although the focus has been on objective social roles and health behavior, the brain is the key organ for forming, monitoring, maintaining, repairing, and replacing salutary connections with others. Accordingly, population-based longitudinal research indicates that loneliness (perceived social isolation) is a risk factor for morbidity and mortality independent of objective social isolation and health behavior.

In humans, loneliness contributes to a broad variety of physical and mental disorders that mirror those observed in animals [7]. These disorders include depressive symptomatology [27-29], aggressive behaviors, social anxiety, and impulsivity [7, 8, 15, 17, 19]. In addition, loneliness is a risk factor for recurrent stroke [15], obesity [18], increased vascular resistance [16], elevated blood pressure [16], an under-expression of genes bearing anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid response elements and an upregulation of pro-inflammatory gene transcripts [20-21], abnormal ratios of circulating white blood cells (e.g., neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes; [30], premature mortality [22], decreased sleep salubrity [23-24], diminished immunity [24], and increased hypothalamic pituitary adrenocortical (HPA) activity [8, 25]. As the prevalence of loneliness rises, evidence accrues that loneliness is a major risk factor for poor physical and mental health outcomes. Therefore, there is a crucial need to find a therapy against loneliness. To date, however, there is no pharmacological treatment for loneliness. Animal research may shed promising light on this issue, however, and it is the evidence from this animal literature that constitutes the rationale for the proposed medical hypothesis.

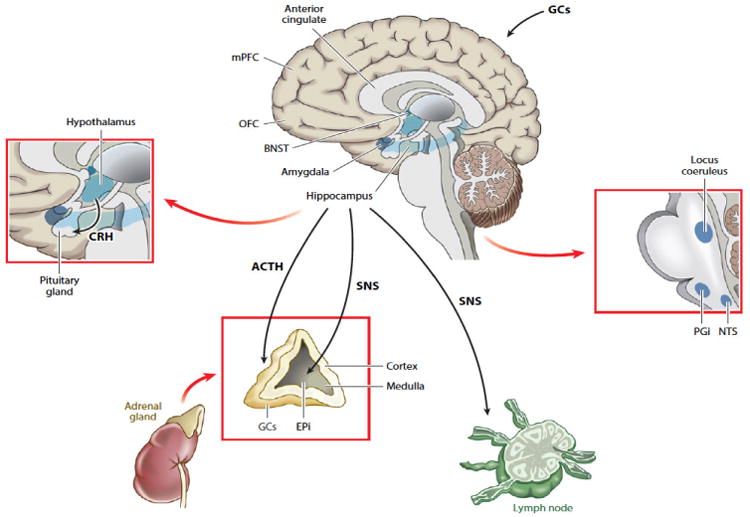

Loneliness and HPA axis

To the extent that the brain is the central organ for evaluating relationships with others, the neuroendocrine system becomes an important system through which perceived social isolation may operate, at least in part, to affect morbidity and mortality. Research suggests that loneliness and social threats are associated most consistently with activity of the HPA axis [8 for review]. Human and animal investigations of social isolation and the neuroendocrine system suggest that: (a) chronic social isolation increases the activation of the HPA axis, and (b) these effects are more dependent on the disruption of a social bond between a significant pair than objective isolation per se [8 for review]. A cascade of signals travels from the prefrontal cortex and limbic regions (e.g., amygdala, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis or BNST) to the brainstem (e.g., locus coeruleus) and to the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus. The sympathetic nervous system includes both sympathetic nerve fibers that directly innervate most major organ systems and locally release the catecholamine neurotransmitter norepinephrine, as well as an adrenal-medullary (SAM) component. The direct innervation of the adrenal medulla by the sympathetic nervous system permits rapid neuroendocrine responses to acute stressors. On the other hand, the HPA axis is sensitive to the interpretation by the brain of threats and stressors, as well, and influences a wide range of physiological, behavioral, and health outcomes [8]. Schematics of the SAM and HPA axes are depicted in Figure 2. Unlike the adrenal medulla of the SAM axis, the adrenal cortex of the HPA axis is necessary for survival and the HPA axis includes a negative feedback mechanism to limit its circulating hormonal outputs.

Figure 2.

Schematics of the SAM and HPA axes, From [8].

The limbic system permits the modulation of HPA activity by the resulting environmental appraisals, including appraisals of the quality of companionship and mutual assistance available in the social environment – a strong determinant of perceived social isolation [8]. Within the limbic system, the central and medial nuclei of the amygdala and the BNST are connected by cells throughout the stria terminalis, and both the amygdala and the BNST project to hypothalamic and brainstem areas that mediate autonomic, neuroendocrine, and behavioral responses to aversive or threatening stimuli [8, 31]. The BNST, which receives inputs from the hypothalamus and amygdala, is associated with anger-related emotional processing [32], is comprised of multiple distinct subnuclei (like the amygdala), which differentially regulate HPA activation [33-34]. The amygdala and the BNST are involved in fear and anxiety conditioning, respectively [35] – two acquired behaviors that permit anticipatory responses to a potentially threatening situation. The amygdala appears to be especially important for rapid-onset, short-duration behaviors which occur in response to specific threats, whereas the BNST appears to mediate slower-onset, longer-lasting responses that frequently accompany sustained threats (or the surveillance for threats) and that may persist even after threat termination [8, 36].

Allopregnanolone and HPA axis

Allopregnanolone, also known as 3 α, 5 αtetrahydroprogesterone (THP) is (as its name applies) a neuroactive steroid derived from progesterone, and specific enzymes in the brain are involved in the biosynthesis of allopregnanolone (ALLO; [37, 38 for reviews]). Produced in both sexes (males and females) by the adrenal glands [39], ALLO is synthesized within the nervous system from progesterone by two sequential enzymatic reactions: First, progesterone is converted into 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP) by the enzyme 5α-reductase. 5α-DHP is then converted into ALLO by NADPH-dependent cytosolic aldoketo reductases (AKR, including one of its isoforms 3 α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 3 α-HSD [37-40]). In contrast to progesterone and 5α-DHP, ALLO does not bind to progesterone receptors, but is rather a positive modulator of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptors [39]. Accordingly, ALLO can play a dual role in the nervous system.

First, like progesterone (via classical steroid receptors) from which it is derived, ALLO can exert a protective and regenerative role on the brain and the spinal cord [37 for review, 41-45]. For instance, both progesterone and ALLO have beneficial effects in the recovery of traumatic brain injury, in reducing inflammation, and increasing antioxidant activity [35 for review]. Interestingly, ALLO is more effective than progesterone in reducing cortical infarct volume, apoptosis, and in reducing neuron loss [46, see also 37 for review].

Second, unlike progesterone, ALLO1 can reduce neuroendocrine stress responses [8, 37, 47-48]. In turn, the down regulation of ALLO biosynthesis in the serum/plasma has been described as a potential contributor to various emotional and psychiatric disorders, such as major depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, post-partum depression, negative symptoms in schizophrenia, or impulsive aggression [38, 49]. The role of ALLO in psychiatric disorders has been mainly driven by a growing body of evidence that demonstrates that some (not all2) antidepressants, such as selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline [49] as well as some antipsychotic drugs (e.g., olanzapine), or mood stabilizers (e.g., carbamazepine) may enhance the formation of ALLO through increased efficiency of conversion of DHP to ALLO [38, 49]. Over the past 15 years, two mechanisms of action for this specific role of ALLO on emotion regulation and stress reduction have been suggested:

ALLO enhances the inhibitory signals of the neurotransmitter GABA via a prolonged opening time of chloride channels within GABAA receptors [37, 41-45, 48] – receptors that are widely distributed in the glutamatergic neurons of brain areas that are involved in emotion and stress responses (e.g. limbic areas, such as the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the BNST). As a potent positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptor complex, ALLO is a powerful anxiolytic, anesthetic, and anticonvulsivant agent [38, 48, 49]. Interestingly, this ALLO-related GABAergic mechanism differs from other GABAergic effects observed with standard psychoactive drugs, as the GABAA binding sites of ALLO are distinct from the GABA sites of benzodiazepines and barbiturates [38, 48].

ALLO has specific regulatory effects on the HPA axis functions [38, 47]. While acute stress increases ALLO levels, which negatively modulates the stress-induced HPA axis activation and facilitates the recovery post-stressful events, repeated or chronic [physical or emotional] stress leads to a significant reduction in serum concentration of ALLO [37-38 for reviews]. This suggests that chronic stress alters ALLO synthesis, which in turn leads to the hyperactivation of the HPA axis [38, 50].

Interestingly for the present hypothesis on the potential role of ALLO on perceived social isolation (loneliness), social stressors can also modulate ALLO. For instance, studies in adult mice socially isolated for at least four weeks, compared to group housed male mice, show reductions in levels of ALLO in hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons and glutamatergic granular cells of the dentate gyrus, cortical pyramidal neurons (layers V-VI), and neurons in the basolateral amygdala –reductions that are attributable to the effects of social isolation on a specific enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of ALLO [46-48]. Pre-clinical studies indicates that: i) the exaggerated contextual fear response expressed by socially-isolated mice can be normalized with a single injection of ALLO [49]; ii) HPA dysfunction and impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis respectively can be normalized or prevented with the administration of exogenous ALLO (or ALLO precursors) either during or following a period of chronic stress; iii) contextual fear conditioning and aggression can be regulated with ALLO [50]; iv) socially isolated animals exhibited reduced HPA responsiveness, which was either prevented or normalized with ALLO treatment [42]; v) the establishment of depressive/anxiety-like behaviors in rats can be precluded also with administration of exogenous ALLO [8, 15, 45, 48, 50].

Combined, these results in animals indicate that administration of exogenous ALLO (or ALLO precursors) either during or following a period of chronic stress can prevent or normalize HPA dysfunction and impairment of hippocampal neurogenesis respectively, precluding the establishment of depressive/anxiety-like behaviors. In line with this, clinical studies show that decreases in the serum, plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid content of ALLO are associated with several psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety spectrum disorders, posttraumatic stress disorders, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, schizophrenia, and impulsive aggression [37-38, 51-61]. Together, these findings provide a strong rationale for our ALLO hypothesis of loneliness.

Our Hypothesis

Based on the above animal literature, we hypothesize that ALLO plays a crucial role in loneliness in humans. The similarities between animal and human research suggest that perceived social isolation (loneliness) may be associated with a reduction in the synthesis of ALLO, potentially by reducing BDNF regulation and increasing HPA activity through the hippocampus, amygdala, and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), especially during social threat processing. Even if of course it is clear that animal literature does not address the loneliness (subjective social isolation) per se (but rather objective social isolation), there is a large literature in which social animals are randomly assigned either to normal social living conditions or to socially isolated living conditions. Select studies of mammals also have contrasted the effects of social isolation from a preferred partner and social isolation from a non-preferred conspecific, which permits parsing the effects of perceived from objective social isolation ([7, 8 for reviews]). Mechanistic animal studies in which adult animals are experimentally assigned to normal or socially isolated housing conditions are important for evaluating the causal effects of an individual being deprived of mutual assistance and companionship on the role of ALLO on HPA activity.

We, therefore, hypothesize that perceived social isolation in humans shares with social isolation in animals/humans a common mechanism i.e., a block in the synthesis of ALLO, potentially by increasing the HPA activity through the hippocampus, BNST, and the amygdala, especially during social threat processing. We also posit that these low ALLO levels then reduce BDNF expression.

This ALLO hypothesis of loneliness is in line with the hypothesis that ALLO and its “precursors” (such as pregnenolone) can affect brain circuits involved in emotion regulation and depression [37-38]. It is, however, noteworthy that depression and loneliness are distinct (yet related) phenomena [27-29]. For instance, despite a correlation between loneliness and depression ranging from .38 to .71 [27], there is now considerable evidence that loneliness and depression are separable and that loneliness increases the risk for depression [27-29]. Compared to lonely individuals, depressed patients show a more complex disequilibrium of neuroactive steroids with decreased levels of ALLO and increased levels of similar substances (isopregnanolone) [38]. Based on recent studies suggesting that the effects of some SSRIs (e.g., fluoxetine) that can improve the behavioral effects of social isolation do not occur through the inhibition of selective serotonin reuptake (as in it is the case in depression), but rather through elevated cortico-limbic levels of ALLO and BDNF mRNA expression [47], we hypothesize that administration of ALLO precursors can normalize ALLO regulation in chronically lonely individuals, which in turns may provide a novel therapeutic target for the treatment of loneliness. Moreover, based on the premise that loneliness leads to depression [27-29], we further hypothesize that early administration of ALLO precursors in the early stages of loneliness could mitigate its effects on depression.

Testing the Hypothesis

Our ALLO hypothesis of loneliness suggests that low corticolimbic ALLO levels and diminished ALLO regulation play a crucial role in loneliness. Even if it is of course clear that feeling lonely is not a prerequisite to de-activate the ALLO system, we postulate the existence of a shared mechanism for both loneliness and the ALLO system. If this hypothesis is correct, one would expect that the exogenous administration of ALLO (or ALLO precursors) in lonely individuals to increase cortico-limbic levels of ALLO and BDNF mRNA expression and to decrease subjective feelings of loneliness and the associated deleterious physiological effects (e.g., elevated HPA activation, impaired sleep salubrity) in comparison with a placebo.

The subjective character of loneliness can make it difficult to assess definitively. The tools of social neuroscience make it possible to approach loneliness not only by the analysis of subjective self-reports (e.g., UCLA loneliness scale), but also by approaching the automatic (non-conscious) self-preservation mechanisms of loneliness, for instance, using high performance electrical neuroimaging and evoked microstate analyses [13-14]. In lonely individuals, recent studies have shown that the perception of social threat (compared to non-social threat) activates the para-hippocampal and amygdala regions during the early (non-conscious) period (between 116 ms and 136 ms) of information processing [13-14], and the amygdala region (including BNST) modulates the neural responses to social stimuli in the temporo-parietal junction [14]. In turn, loneliness is known to be inversely related to the level of activation of the temporo-parietal region bilaterally in response to social threat (compared to non-social threat notably between 116 ms and 124 ms post-stimulus onset; [14]), possibly reflecting a disorder in reading others' intentions, feelings, and others' behaviours or a less focus on others and more on one's own self-preservation in negative social contexts [5, 14, 92].

Based on these neural findings, exogenous administration of ALLO (or an ALLO precursor that can cross the blood brain barrier i.e., pregnenolone), with event-related functional and/or electrical neuroimaging in a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover design in lonely individuals should make it possible to observe a modulation of this cascade of activation and deactivation in the amygdala region and temporo-parietal junction observed in response to social threat. Based on a recent fMRI study showing the modulation of the amygdala and the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex (two regions rich in GABAA receptors) two hours after a single dose of 400 mg pregnenolone in healthy subjects while they were performing an attention emotion appraisal task [63], we expect the exogenous administration of a single dose of 400 mg pregnenolone to reduce [and normalize] the amplitude response of the amygdala that is known to be increased in lonely individuals. In turns, the reduction of amygdala activity should lead to an increased response of (and an increased connectivity with) the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex and the temporo-parietal junction in the early stages of information processing.

Because of some pharmacokinetic limitations, such as bioavailability [37-38], and the uncertainty of the long-term effects of such exogenous administration on loneliness, longitudinal studies would need to be performed. The systematic study of the ALLO hypothesis in individuals who are chronically lonely will provide critical insights on the role of ALLO on social threat processing and on how to reduce loneliness and its related behaviors, such as hypervigilance for social threat impulse control, and poor sleep salubrity.

Conclusion

We hypothesize here that ALLO reduction is involved in loneliness in humans, notably through its corresponding reductions in its facilitative effects on GABA and its modulating effects on HPA activity and BDNF expression. Recent meta-analysis and reviews suggest that cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) designed to modify maladaptive social cognition associated with loneliness in humans may be especially worth pursuing [11 for review]. Such interventions can, however, be expensive and time-consuming, and the client's lack of openness to changing their thoughts about and interactions with others can be an obstacle to effective treatment focusing on the subjective, conscious aspects of loneliness [11]. While CBT alone might be sufficient to treat acute loneliness, the use of CBT in the case of chronic loneliness might be more effective (or effective for a greater proportion of individuals) if an appropriate ALLO pharmacological treatment acting on the HPA axis and the BDNF expression and reducing hypervigilance to social threat associated with loneliness within the non-conscious (within the first 140 ms) stages of information processing is used in parallel and in the early stages of CBT after diagnostic.

Although the neurobiology of loneliness is now well admitted, the systematic study of our new and potentially testable explanation of loneliness might provide an adjunctive therapeutic target early in CBT interventions to help alleviate chronic loneliness, which in turns might open a new avenue towards understanding the social brain.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by the National Institute on Aging Grant No. R37AG033590. The authors thank James Estaver from the HPEN laboratory.

Footnotes

Similar effects have been reported with 3α 5β trtrahydroprogesterone, also known as pregnanolone, which is another 3 α –reduced progesterone metabolite and a precursor of ALLO.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest that could have biased our current medical hypothesis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cacioppo JT. The social nature of human kind. In: The Chicago Social Brain Network, editor. Invisible forces and powerful beliefs: Gravity, gods, and minds. Upper Saddle River, NJ: FT Press; 2011. pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cacioppo S, Cacioppo JT. Decoding the invisible forces of social connections. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2012;6(Article 51):1–7. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cacioppo JT. The lethality of loneliness. TEDX Des Moines. 2013 Sep 9; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0hxl03JoA0. Retrieved on August 3, 2015.

- 4.Kapheim KM, Pan H, Li C, Salzberg SL, et al. Genomic signatures of evolutionary transitions from solitary to social living. Science. 2015;348(6239):1139–1143. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Boomsma DI. Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cognition and Emotion. 2014;28:3–21. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2013.837379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cacioppo JT, Patrick B. Loneliness: Human nature and the need for social connection. New York: W.W Norton & Company; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Cole SW, Capitanio JP, Goossens L, Boomsma DI. Loneliness Across Phylogeny and a Call for Comparative Studies and Animal Models. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10:202–212. doi: 10.1177/1745691614564876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, Cole SW. The Neuroendocrinology of Social Isolation. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:733–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goossens L, van Roekel E, Verghaen M, Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Maes M, Boomsma DI. The genetics of loneliness: Linking evolutionary theory to genome-wide genetics, epigenetics, and social science. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10:213–226. doi: 10.1177/1745691614564878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cacioppo JT, Hawley LC. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13(10):447–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT. (2015) Loneliness: Clinical Import and Interventions. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2015;10:238–249. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S. Social Relationships and Health: The Toxic Effects of Perceived Social Isolation. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2014;8(2):58–72. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cacioppo S, Balogh S, Cacioppo JT. Implicit attention to negative social, in contrast to nonsocial, words in the Stroop task differs between individuals high and low in loneliness: Evidence from event-related brain microstates. Cortex. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cacioppo S, Bangee M, Balogh S, Cardenas-Iniguez C, Qualter P, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness and implicit attention to social threat: A high performance electrical neuroimaging study. Cognitive Neuroscience. 2015 doi: 10.1080/17588928.2015.1070136. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, Cacioppo JT. Toward a neurology of loneliness. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(6):1464–504. doi: 10.1037/a0037618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cacioppo JT, Hawley LC, Crawford LE, et al. Loneliness and health: potential mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(3):407–17. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearns A, Whitley E, Tannahill C, Ellaway A. Loneliness, social relations and health and well-being in deprived communities. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(3):332–44. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2014.940354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauder W, Mummery K, Jones M, Caperchione C. A comparison of health behaviours in lonely and non-lonely populations. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(2):233–45. doi: 10.1080/13548500500266607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst JM, Cacioppo JT. Lonely hearts: Psychological perspectives on loneliness. App & Prev Psych. 1998;8:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cole SW, Hawkley LC, Arevalo JM, Sung CY, Rose RM, Cacioppo JT. Social regulation of gene expression in human leukocytes. Genome Biol. 2007;8(9):R189. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole SW, Hawkley LC, Arevalo JM, Cacioppo JT. Transcript origin analysis identifies antigen-presenting cells as primary targets of social regulated gene expression in leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(7):3080–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014218108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Y, Hawkley LC, Waite LJ, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: a national longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(6):907–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Berntson GG, et al. Do lonely days invade the nights? Potential social modulation of sleep efficiency. Psychol Sci. 2002;13(4):384–7. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pressman SD, Cohen S, Miller GE, Barkin A, Rabin BS, Treanor JJ. Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psychol. 2005;24(3):297–306. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steptoe A, Owen N, Kunz-Ebrecht SR, Brydon L. Loneliness and neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory stress responses in middle aged men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29(5):593–611. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(03)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cacioppo JT, Ernst JM, Burleson MH, et al. Lonely traits and concomitant physiological processes: the MacArthur social neuroscience studies. Int J Psychophysiol. 2000;35(2-3):143–54. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(99)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol Aging. 2006;21(1):140–51. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cacioppo JT, Hawley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(2):453–63. doi: 10.1037/a0017216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holvast F, Burger H, de Waal MM, van Marwijk HW, Comijs HC, Verhaak PF. Loneliness is associated with poor prognosis in late-life depression: Longitudinal analysis of the Netherlands study of depression in older persons. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cole SW. Social regulation of leukocyte homeostasis: The role of glucocorticoid sensitivity. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(7):1049–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker DL, Davis M. Role of the extended amygdala in short-duration versus sustained fear: a tribute to Dr. Lennart Heimer. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213(1-2):29–42. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siegel A, Brutus M. Neural substrate of aggression and rage in the cat. Prog Psychob Physiol. 1990;14:135–233. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Choi DC, Furay AR, Evanson NK, Ostrander MM, Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Bed nucleus of the stria terminalis subregions differentially regulate hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity: implications for the integration of limbic inputs. J Neurosci. 2007;27(8):2025–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4301-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(6):397–409. doi: 10.1038/nrn2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis M. Are different parts of the extended amygdala involved in fear versus anxiety? Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44(12):1239–47. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walker DL, Toufexis DJ, Davis M. Role of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis versus the amygdala in fear, stress, and anxiety. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463(1-3):199–216. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01282-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melcangi RC, Panzica GC. Allopregnanolone: State of the art. Progress in Neurobiology. 2014;113:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schüle C, Nothdurfter C, Rupprecht R. The role of allopgrenanolone in depression and anxiety. Progress in Neurobiology. 2014;113:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schumacher M, Mattern C, Ghoumari A, Oudinet JP, et al. Revisiting the roles of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the nervous system: Resurgence of the progesterone receptors. Progress in Neurobiology. 2014;113:6–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robinson JA, Karavolas HJ. Conversion of progesterone by rat anterior pituitary tissue to 5 alpha-pregnane-3,20-dione and 3 alpha-hydroxy-5 alpha-pregnan-20-one. Endocrinology. 1973 Aug;93(2):430–435. doi: 10.1210/endo-93-2-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puia G, Santi MR, Vicini S, et al. Neurosteroids act on recombinant human GABA-A receptors. Neuron. 1990;4(5):759–65. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90202-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Puia G, Mienville JM, Matsumoto K. On the putative physiological role of allopregnanolone on GABA(A) receptor function. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00341-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lambert JJ, Belelli D, Peden DR, Vardy AW, Peters JA. Neurosteroid modulation of GABA-A receptors. Progress in Neurobiology. 2003;71(1):67–80. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lambert JJ, Cooper MA, Simmons RD, Weir CJ, Belelli D. Neurosteroids: endogenous allosteric modulators of GABA(A) receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(Suppl 1):S48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belelli D, Lambert JJ. Neurosteroids: endogenous regulators of the GABA(A) receptor. Nature Review Neuroscience. 2005;6(7):565–75. doi: 10.1038/nrn1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sayeed I, Guo Q, Hoffman SW, Stein DG. Allopregnanolone, a progesterone metabolite, is more effective than progesterone in reducing cortical infarct volume after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Biggio G, Pisu MG, Biggio F, Serra M. Allopregnanolone modulation of HPA axis function in the adult rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231(17):3437–44. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3521-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunton PJ, Russell JA, Hirst JJ. Allopregnanolone in the brain: Protecting pregnancy and birth outcomes. Progress in Neurobiology. 2014;113:106–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griffin LD, Mellon SH. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13512–13517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reddy DS. Physiological role of adrena deoxycorticosterone-derived neuroactive steroids in stress-sensitive conditions. Neuroscience. 2006;138:911–920. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Evans J, Sun Y, McGregor A, Connor B. Allopregnanolone regulates neurogenesis and depressive/anxiety-like behavior in a social isolation rodent model of chronic stress. Neuropharmacology. 2012;63(8):1315–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agís-Balboa RC, Pinna G, Pibiri F, Kadrui B, Costa E, Guidotti A. Down-regulation of neurosteroid biosynthesis in corticolimbic circuits mediates social isolation-induced behavior in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(47):18736–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709419104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nin MS, Martinez LA, Pibiri F, Nelson M, Pinna G. Neurosteroids reduce social isolation-induced behavioral deficits: a proposed link with neurosteroid-mediated upregulation of BDNF expression. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2011;2:73. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pinna G. In a mouse model relevant for post-traumatic stress disorder, selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSS) improve behavioral deficits by normalizing allopregnanolone biosynthesis. Behav Pharmacol. 2010;21(5-6):438–50. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32833d8ba0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pibiri F, Nelson M, Guidotti A, Costa E, Pinna G. Decreased corticolimbic allopregnanolone expression during social isolation enhances contextual fear: A model relevant for posttraumatic stress disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(14):5567–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801853105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nelson M, Pinna G. S-norfluoxetine microinfused into the basolateral amygdala increases allopregnanolone levels and reduces aggression in socially isolated mice. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60(7-8):1154–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rapkin AJ, Morgan M, Goldman L, Brann DW, Simone D, Mahesh VB. Progesterone metabolite allopregnanolone in women with premenstrual syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(5):709–14. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00417-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Romeo E, Ströhle A, Spaletta G, et al. Effects of antidepressant treatment on neuroactive steroids in major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(7):910–3. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.7.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Uzunova V, Sheline Y, Davis JM, et al. Increase in the cerebrospinal fluid content of neurosteroids in patients with unipolar major depression who are receiving fluoxetine or fluvoxamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(6):3239–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bloch M, Schmidt PJ, Danaceau M, Murphy J, Nieman L, Rubinow DR. Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):924–30. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nappi RE, Petraglia F, Luisi S, Polatti F, Farina C, Genazzani AR. Serum allopregnanolone in women with postpartum “blues”. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(1):77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cacioppo JT, Norris CJ, Decety J, Monteleone G, Nusbaum H. In the eye of the beholder: Individual differences in perceived social isolation predict regional brain activation to social stimuli. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2009;21:83–92. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sripada RK, Marx CE, King AP, Rampton JC, Ho S, Liberzon I. Allopregnanolone elevations following pregnenolone administration are associated with enhanced activation of emotion regulation neurocircuits. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;73(11):1045–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]