Abstract

Osteoma is a slow growing benign tumor consisting of well differentiated compact or cancellous bone that increases in size by continuous growth. It can be of a central, peripheral, or extraskeletal type. The peripheral type arises from the periosteum and is rarely seen in mandible. Although completely curable with adequate surgical treatment, osteomas precede the clinical radiographic evidence of colonic polyposis/Gardner’s syndrome. Therefore they may be sensitive markers for the disease. Recurrence of peripheral osteoma after surgical excision is extremely rare. However it is appropriate to provide both clinical and radiographic follow up after surgical excision of peripheral osteoma. This article describes the case of a 45 year old male who presented with painless swelling of the right body of mandible and resultant cosmetic facial disfigurement and functional impairment.

Keywords: Peripheral osteoma, Central osteoma, Gardner’s syndrome

Introduction

Osseous lesions develop relatively infrequently in the head and neck region. These lesions are an unwelcome guest and deep are its impact when it is located in the face. An osteoma is a benign slow growing osteogenic neoplasm characterized by proliferation of either compact or cancellous bone [1, 2]. Osteomas of the jaws may arise on the surface of the bone as a polypoid or sessile mass in peripheral type (periosteal, paraosteal or exophytic), in the medullary bone in central type (endosteal) or in the soft tissue (extra skeletal). Osteomas are usually asymptomatic, clinically silent and usually manifest only as focal asymmetry or disfigurement. Various etiopathogenic hypotheses have been proposed for osteoma formation, including congenital anomalies, inflammation, muscular activity, embryogenic changes and trauma [3]. Osteomas are found mainly in the craniofacial bones and are rarely, if ever diagnosed in other bones. Solitary peripheral osteomas of the jaws are a rare entity. They involve the mandible more commonly than the maxilla [4] with the site of greatest predilection being the lingual aspect of the body, the angle and inferior border of the mandible [5]. It has been reported that osteoma can occur at any age and that males are affected more frequent than females. Patient with osteomas should be evaluated for Gardner’s syndrome. Gardner’s syndrome constitutes multiple osteomas, supernumerary teeth, adenomatoid gastrointestinal polyps and tumors of soft tissue and skin. Such polyps in gastrointestinal system usually turn into malignancy. Diagnosing osteoma is therefore important and has life saving potential because these can be seen in the earlier stage of Gardner’s syndrome, the dentist may play an important role in the diagnosis on colonic polyposis. The purpose of this article is to present a large peripheral osteoma originating from buccal surface of the mandible causing asymmetry in 45 year old male patient.

Case Report

A 45 year old male patient reported with a complaint of slowly enlarging swelling in the right lower jaw for the last 15 years. His previous history included trauma to the right mandible region due to a road traffic accident. The lesion was noticed by the patient 10 years ago and had shown slow and progressive growth until a visible deformity could be seen in the right side body of the mandible causing concern to the patient. Cosmetic disfigurement and functional impairment brought the patient for treatment. A discrete facial asymmetry was observed extraorally on right side mandible with lobulated surface of bony consistency, fixed, non tender, non compressible extending anteriorly from commisure of the lip, posteriorly to body of the mandible, inferiorly one cm below the base of the mandible measuring approximately 3 × 6 cm in size (Fig. 1). Intraoral examination revealed a firm, sessile, well circumscribed swelling covered by smooth regular mucosa extending from 43 to 47 regions. There was no painful symptom except facial asymmetry.

Fig. 1.

Clinical photograph—frontal view

Treatment

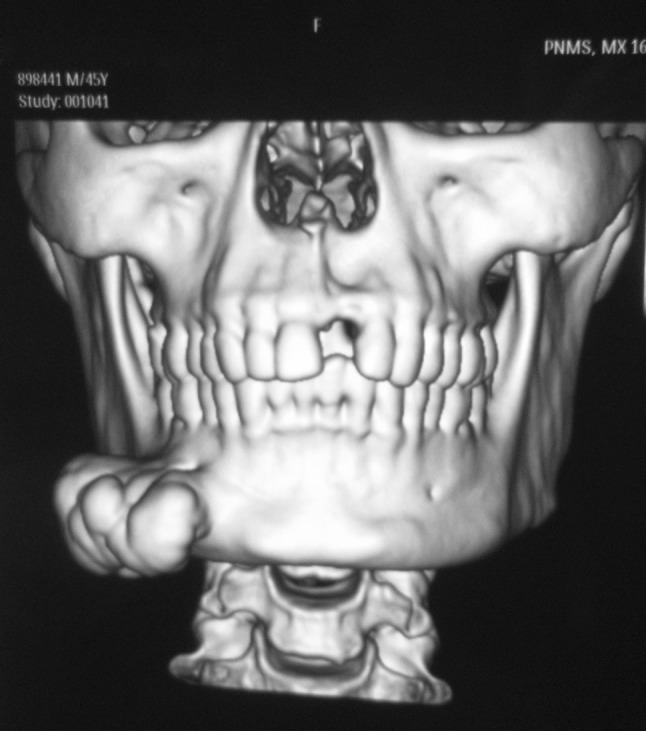

A CT scan with 3D reconstruction was performed for a more accurate diagnosis; it showed a hyperdense, well circumscribed cauliflower-like growth measuring approximately 3 × 6 cm in size with a lobulated surface located in the right body of mandible (Fig. 2). The lesion was provisionally diagnosed as osteoma.

Fig. 2.

3D CT showing cauliflower like growth

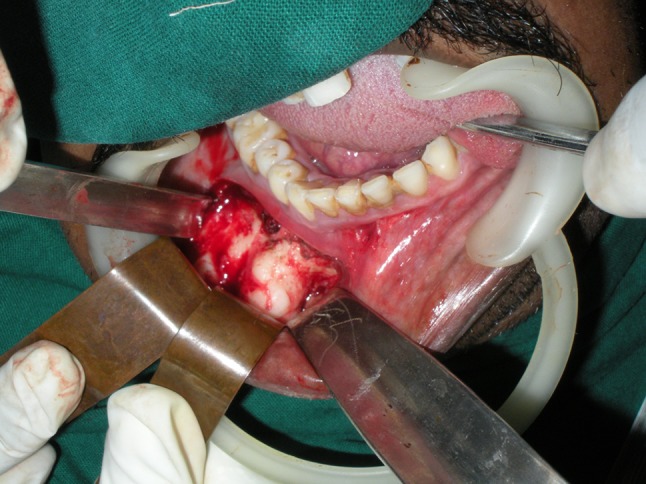

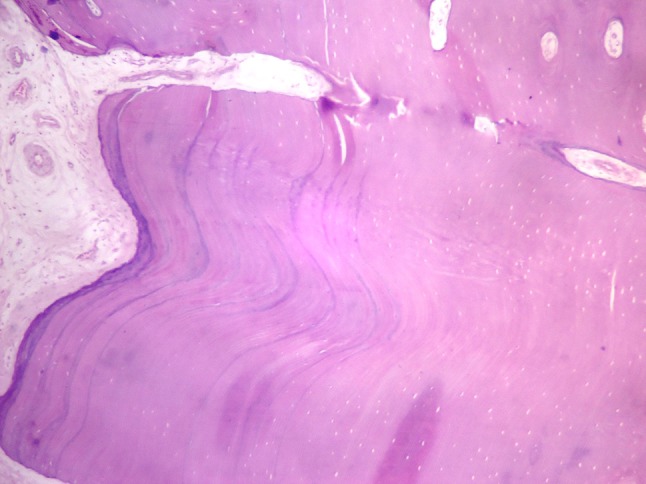

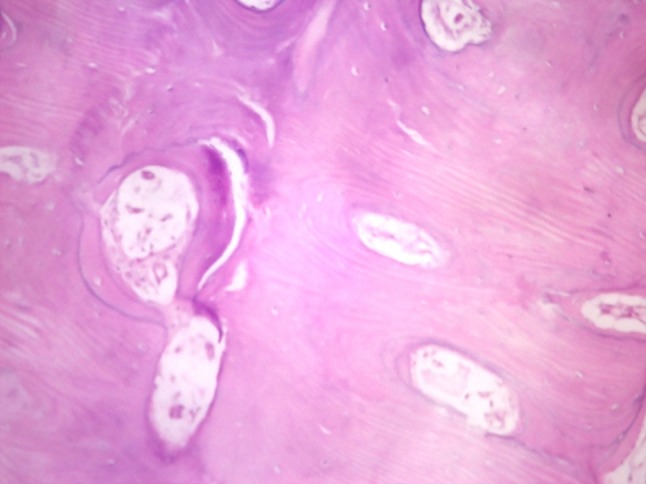

Under GA, the lesion was exposed intraorally by vestibular incision and periosteal elevation (Fig. 3). Bony lesion was completely excised from the base and excised specimen sent for microscopic examination. Histopathology examination showed mature compact bone with lacunae and also marrow spaces filled by loose connective tissue. The compact bone showed lamellar pattern with prominent resting lines (Figs. 4, 5). Based on clinical and laboratory findings a definitive diagnosis of peripheral osteoma compact type was established. The patient did not present any post operative complication (Fig. 6) and 1 year follow-up was uneventful.

Fig. 3.

Intra operative picture showing exposed lesion

Fig. 4.

Histopathologic picture showing mature compact bone with prominent resting lines and marrow spaces in-between (×10 magnification)

Fig. 5.

Histopathologic picture showing compact bone showing lamellar pattern with bone connective tissue in marrow spaces (×40 magnification)

Fig. 6.

Postoperative picture

Discussion

Osteoma is a benign osteogenic neoplasm composed of well differentiated mature bone tissue [5]. Osteomas are essentially tumors of craniofacial bone, rarely affecting the extragnathic skeleton although cases of soft tissue osteoma arising within the bulk of skeletal muscles have been reported [6]. Osteomas of the jaw bones are rare. As far as osteomas occurring in this region is concerned it is reported that most of them have occurred as peripheral type in the jaw bones [7], which are quite rare. Osteomas occur more frequently in the mandible than the maxilla [4]. An osteoma involving the mandibular condyle may cause a slowly progressing shift in the patients occlusion with midline deviation towards unaffected side. Sayan et al. [8] reported 22.8 % and Kaplan et al. [9] and Woldenberg et al. [10] reported 81.3 and 64 % of occurrence respectively in the mandible and 14.28 % of occurrence in maxilla by Sayan et al. [8] in their study. In instances of mandibular involvement the most common locations are the lingual sides [8] of the premolars, the inferior border of the condyle and the inferior and lateral region of the mandibular angle [1]. Males are affected more frequent than females in a ratio of approximately 2:1 [4]. The overall incidence of osteoma is low affecting 0.01–0.04 % of the population. Osteomas comprise 12.1 % of benign bone tumors and 2.9 % of all bone tumors. To the best of our knowledge 87 well documented cases of peripheral osteoma of the lower jaw have been reported in the literature till 2013 (Table 1). Out of 87 cases 41.3 % of cases are from the body of the mandible, 21.83 % from the condyle, 16.09 % from the angle, 11 % from the ascending ramus, 8 % from the coronoid process and 2.2 % from the sigmoid notch.

Table 1.

Review of literature depicting important publications on peripheral osteoma of mandible

| S. no. | Authors | Age | Sex | Size (cm) | Location | Surgical excision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | De Franca et al. [11] | 33 | F | 2.5 | Angle of mandible | + |

| 2 | Youmans et al. [12] | 57 | M | 5.5 | Body of mandible | + |

| 3 | Singhal et al. [13] | 15 | F | 2 | Angle of mandible | + |

| 4 | Tarsitano et al. [1] | 41 | M | – | Body and ramus | + |

| 5 | Kachewar et al. [2] | 50 | F | 10.8 | Body, ramus and angle | − |

| 6 | Khan et al. [14] | 35 | F | – | Body of mandible | − |

| 7 | Kashima et al. [15] | 42 | M | 5.0 | Body of mandible | + |

| 8 | Kashima et al. [15] | 58 | F | 3.5 | Body of mandible | + |

| 9 | Johann et al. [16] | 43 | F | 4.0 | Body of mandible | + |

| 10 | Maclennan et al. [17] | 31 | F | 5.0 | Angle of mandible | + |

| 11 | Rodriguez et al. [3] | 25 | M | 1.5 | Body of mandible | + |

| 12 | Bulut et al. [18] | 37 | F | 3.0 | Body of mandible | + |

| 13 | Cutilli BJ et al. [19] | 22 | F | 4.0 | Angle of mandible | + |

| 14 | Iwai et al. [5] | 78 | F | 3.6 | Mandibular notch | − |

| 15 | Bonder et al. [20] | 16 | F | 4.0 | Ascending ramus | + |

| 16 | Siar CH et al. [21] | 32 | F | 4.8 | Condyle | + |

| 17 | Saati et al. [22] | 26 | F | 3.9 | Angle of mandible | + |

| 18 | Ramaliga et al. [23] | 44 | M | 3.0 | Angle of mandible | + |

| 19 | Ochiai et al. [7] | 33 | M | 2.5 | Angle of mandible | + |

| 20 | Manjunatha et al. [24] | 43 | M | – | Body of mandible | + |

The pathogenesis of osteoma is not completely unknown. They are referred to developmental anomalies, true neoplasm [4], reactive lesions triggered by trauma [4], muscle traction [6, 8] or infection infiltration of interdental bone and abnormal histological bone structure might support the neoplastic nature of this lesion [1]. The clinical signs, symptoms and complications depend on the location, size and growth direction of the lesion, symptoms related directly to an osteoma generally arise from a mass effect as the lesion impinges on normal structures. Osteomas may be solitary or multiple. Multiple osteomas of the facial skeleton may occur in case of Gardner’s syndrome. This is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by intestinal polyposis, multiple osteomas, cutaneous fibromas, epidermoid cyst and impacted teeth. No such lesions were found in our patient.

Radiographically the presence of an oval, radioopaque well circumscribed mass attached by a broad bass or pedicle to the affected cortical bone is a hallmark of peripheral osteoma. CT scan particularly 3D reconstruction scan is useful in defining the exact extension of the tumor and to determine the position of the lesion in relation with adjacent anatomical structures, when removal of lesion is considered. Histologically, osteomas have two distinct variants [8]. The compact osteoma or ivory osteoma consist of normal appearing dense mass of lamellar bone with minimal marrow tissue, and occasional haversian system. The cancellous osteoma contains trabeculae of mature lamellar bone with intervening fatty fibrous marrow with osteoblasts.

The differential diagnosis include peripheral ossifying fibroma, exostoses, periosteal osteoblastoma, osteoid osteoma. Exostoses are bony excrescence considered as hamartomas commonly seen in buccal and lingual regions (torus mandibularis) and hard palate (torus palatinus) that stop growing after puberty, but osteomas may continue to grow after puberty. Peripheral ossifying fibroma-a reactive focal overgrowth, periosteal osteoblastoma and osteoid osteoma are painful destructive mass with rapid growth which usually occur in young patients and are rare in the maxillofacial regions. The appearance and monogenicity of osteoma is not difficult to characterize and diagnose.

Treatment of the osteoma consisting of complete surgical removal from the base where it unites with the cortical bone is preferred. There are no reports of osteoma undergoing malignant transformation. Till now only one case with recurrence has been reported by Bosshardt et al. Both periodic clinical and radiographic follow up after surgical excision of a peripheral osteoma is necessary. Table 1 enlists important publications on similar pathology [11–24].

Conclusion

Peripheral osteomas of jaw bones are rare. They are slow growing, clinically silent and usually manifest only as a focal asymmetry or disfigurement. Indications for surgery are based on degree of disfigurement and functional impairment. After surgical excision of osteomas, recurrences or malignant transformation are quite rare. Peripheral osteomas may be genetic markers for the development of colorectal carcinoma. Patient with peripheral osteomas should be evaluated for Gardner’s syndrome. Diagnosing osteoma is therefore important and has life saving potential because these can be seen in the earlier stage of Gardner’s syndrome.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Tarsitano A, Marchetti C. Unusual presentation of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome due to a giant mandible osteoma: case report and literature review. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2013;33:63–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kachewar, et al. Giant peripheral osteoma of the mandible. Internet J Med Updat. 2012;7(1):66–69. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez Y, Baena R, Rizzo S, et al. Mandibular traumatic peripheral osteoma: a case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:e44–e48. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viswanatha B. Maxillary sinus osteoma: two cases and review of the literature. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2012;32:202–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwai T, Izumi T, Baba J, Maegawa J, Mitsudo K, Tohnai I. Peripheral osteoma of the mandibular notch: report of a case. Iran J Radiol. 2013;10(2):74–76. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janjatov B, Eric M, Sojie D, et al. Osteoma in medial pterygoid muscle: an unusual case. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(6):848–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ochiai S, Kuroyanagi N, Sakuma H, Sakuma H, Miyachi H, Shimozato K, et al. Endoscopic-assisted resection of peripheral osteoma using piezosurgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115:e16–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sayan NB, Ucok C, Karasu HA, et al. Peripheral osteoma of the oral and maxillofacial region: a study of 35 new cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:1299–1301. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.35727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan I, Calderon S, Buchner A. Peripheral osteoma of the mandible: a study of 10 new cases and analysis of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:467–470. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90342-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woldenberg Y, Nash M, Bodner L. Peripheral osteoma of the maxillofacial region. Diagnosis and management: a study of 14 cases. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10(Suppl 2):E139–E142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De França TR, Gueiros LA, De Castro JF, et al. Solitary peripheral osteomas of the jaws. Imaging Sci Dent. 2012;42:99–103. doi: 10.5624/isd.2012.42.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youmans D, Caudle L, Hays L. Peripheral osteoma of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;25:785–791. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singhal P, Singhal A, Ram R, et al. Peripheral osteoma in a young patient: A marker for precancerous condition? J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2012;30:74–77. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.95588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khan, et al. Solitary osteoma of body of the mandible. J Orofac Sci. 2013;5:58–60. doi: 10.4103/0975-8844.113703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kashima K, Ol Rahman, Sakoda S, et al. Unusual peripheral osteoma of the mandible:report of 2 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:911–913. doi: 10.1053/joms.2000.8223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johann AC, De Freitas JB, De Aguiar MC, et al. Peripheral osteoma of the mandible: case report and review of the literature. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2005;33:276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maclennan WD, Brown RD. Osteoma of the mandible. Br J Oral Surg. 1974;12:219–224. doi: 10.1016/0007-117X(74)90128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulut E, Acikgoz A, Ozan B, et al. Large peripheral osteoma of the mandible: a case report. Int J Dent. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/834761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cutilli BJ, Quinn PD. Traumatically induced peripheral osteoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:667–669. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90006-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodner L, Gatot A, Sion-Vardy N, et al. Peripheral osteoma of the mandibular ascending ramus. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1998;56:1446–1449. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(98)90414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siar CH, Jalil AA, Ram S, Ng KH, et al. Osteoma of the condyle as the cause of limited-mouth opening: a case report. J Oral Sci. 2004;46:51–53. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.46.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saati S, Nikkerdar N, Golshah A. Two huge maxillofacial osteoma cases evaluated by computed tomography. Iran J Radiol. 2011;8(4):253–257. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramaglia L, Morges F, Filippella M, Colao A, et al. Oral and maxillofacial manifestations of Gardner’s syndrome associated with growth hormone deficiency: case report and literature review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:e30–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manjunatha BS, Das N, Sutariya R et al. (2013) Peripheral osteoma of the body of mandible. BMJ Case Rep 2013. doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-009857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]