Abstract

Excision and integration of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) are mediated by cassette chromosome recombinases (Ccr), which play a crucial role in the worldwide spread of methicillin resistance in staphylococci. We report a novel ccr gene, ccrC2, in the SCCmec of a Staphylococcus aureus isolate, BA01611, which showed 62.6% to 69.4% sequence identities to all published ccrC1 sequences. A further survey found that the ccrC2 gene was mainly located among coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) and could be found in staphylococcal isolates from China, the United States, France, and Germany. The ccr gene complex harboring the ccrC2 gene was designated a type 9 complex, and the SCCmec of BA01611 was considered a novel type and was designated type XII (9C2). This novel SCCmec element in BA01611 was flanked by a pseudo-SCC element (ΨSCCBA01611) carrying a truncated ccrA1 gene. Both individual SCC elements and a composite SCC were excised from the chromosome based on detection of extrachromosomal circular intermediates. We advocate inclusion of the ccrC2 gene and type 9 ccr gene complex during revision of the SCCmec typing method.

INTRODUCTION

The worldwide emergence of health care-associated, community-associated, and livestock-associated (LA) methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains emphasizes the importance of understanding the genetic basis for acquisition of a methicillin resistance determinant (1). MRSA is generated when a methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) strain exogenously acquires a mobile genetic element, staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec), which carries the mecA gene (2, 3). Excision and integration of SCCmec elements are mediated by cassette chromosome recombinases (Ccr), which are large serine recombinases of the resolvase/invertase family (4). Ccr recombinases are encoded by three phylogenetically distinct ccr genes, ccrA, ccrB, and ccrC, with nucleotide similarities among them below 50%. In general, ccr genes with nucleotide identities of more than 85% are assigned to a same allotype. Until now, five ccrA allotypes and seven ccrB allotypes had been described. In contrast, there has been only one known ccrC allotype since its first description in 2004 (5), because all identified ccrC variants to date have shared identities of more than 87% and are described as different alleles. On the basis of different ccr allotypes and their combinations, eight types of the ccr gene complex have been identified in staphylococcal species (3, 6).

SCCmec elements are highly diverse in their structural organization and genetic content and have been classified into 11 types (6), based on different combinations of ccr gene complexes and mec gene complexes. Among them, nine SCCmec elements carry the ccrA and ccrB genes (ccrAB), whereas only type V and type VII SCCmec elements carry the ccrC gene. It is now a common practice to define MRSA clones by the combination of the SCCmec type and the chromosomal background (3). However, we failed to determine the SCCmec type of a MRSA isolate, BA01611, using the latest SCCmec typing strategy (6), because we could not amplify any known ccr genes from the bacterium. To gain insights into genetic characteristics of this MRSA isolate, we sequenced and characterized its SCCmec element in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibiotic resistance, genotyping, and genome sequencing.

MRSA strain BA01611 was isolated from a milk sample of a Holstein cow with clinical mastitis in northwest China and was identified as S. aureus according to the results of 16S rRNA gene sequencing and the coagulase test. MICs for various antimicrobial agents were determined for BA01611, using an agar dilution method recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (7). Multilocus sequence type (MLST) analysis and a spa typing assay were carried out according to previously described methods (8, 9).

The whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of BA01611 was carried out employing Solexa paired-end-sequencing technology. A genomic DNA library with an insertion size of 500 bp was prepared. WGS sequence data were de novo assembled into contigs using SOAPdenovo software (version 2.21). Furthermore, the contigs were joined into scaffolds using paired-end information. The order of the scaffolds was determined by alignment to a reference genome of S. aureus strain VC40 (GenBank accession no. NC_016912) using SOAPaligner software (version 2.21).

Assembly and identification of SCC elements in BA01611.

To map SCC elements, every scaffold of BA01611 was searched against marker genes, including orfX, mec gene complexes, and ccr gene complexes, using BLASTN (10). Positive scaffolds were aligned to SCC elements of S. aureus strain JCSC6690 (GenBank accession no. AB705453) to reveal their genetic organization. Gaps were closed by PCR amplification, followed by cloning into a pEASY-Blunt Zero vector (Transgen, China) for Sanger sequencing. Gene prediction and annotation for BA01611 were performed using the Rapid Annotations Subsystems Technology (RAST) server (11). The nucleotide sequences of predicted genes and their deduced amino acid sequences were subsequently compared to the nucleotide collection (nr/nt) database and the nonredundant protein database provided by NCBI, respectively.

PCR for excision of SCC elements and for determination of the presence of ccrC2 in staphylococcal isolates.

A set of PCRs were performed for investigating excision of SCC elements according to the method described by Ito et al. (2). Extracted genomic DNA of BA01611 from logarithmic-phase cultures was used as the template. The products were then cloned into a pEASY-Blunt Zero vector (Transgen, China) for Sanger sequencing. Primer sequences are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

A local collection of 97 staphylococcal isolates in our laboratory was used for determining the presence of ccrC2, using the specific primers listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The primer set can discriminate ccrC2 from ccrC1 with an amplicon size of 761 bp. These staphylococci were isolated from bovine mastitis milk in northwest China and have been subjected to 16S rRNA gene sequencing, the coagulase test, and the oxacillin susceptibility test.

Bioinformatics analyses.

In order to determine phylogenetic relations between this novel SCCmec and other reported SCCmec, the NCBI nucleotide blast software was used for genome alignments in the nr/nt and wgs databases with default parameters (accessed on 30 April 2015). The query sequence was the identified nucleotide sequence of Composite Island (CIBA01611), with a length of 49.3 kb. The top matched sequences with both a maximum score of greater than 10,000 and a total score of greater than 30,000 were chosen for detailed analyses.

The comparison of different SCCmec elements was conducted using BLASTN with Mauve software (12) and Easyfig software (13). For the phylogenetic analysis, ccrC genes were aligned by the ClustalX 2.1 program. A phylogenetic tree was constructed employing the MEGA program (version 6.0) with the neighbor-joining method. Bootstrap values were obtained from 1,000 repetitions and are listed as percentages at the nodes.

The existence of ccrC2 in staphylococcal species in GenBank was determined by searching the nr/nt and wgs databases from NCBI, utilizing the nucleotide sequence of the ccrC2 gene as the query.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of this composite SCC, designated Composite Island CIBA01611 (described below), has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. KR187111.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

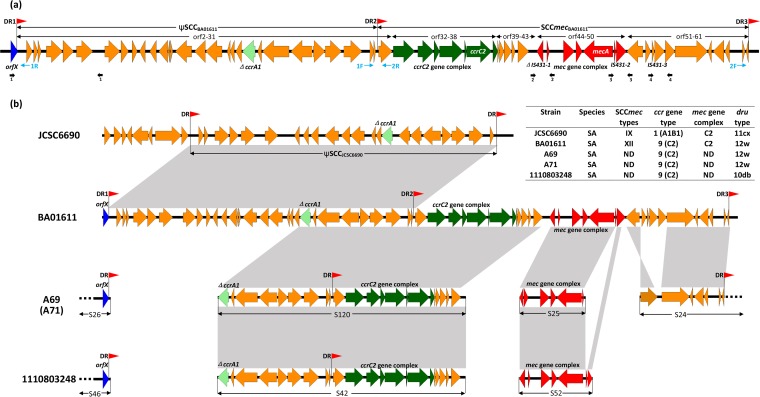

WGS was carried out in order to understand the genetic background of MRSA isolate BA01611. A total of 360 Mb of sequencing data from BA01611 were obtained and assembled into 50 scaffolds (GenBank accession no. LIRC00000000). Among those scaffolds, five were identified as containing SCC elements. Four PCRs were performed to close these gaps. Finally, a composite SCC, designated Composite Island (CIBA01611), with a total length of 49.3 kb was revealed. It consisted of a pseudo-SCC element named ΨSCCBA01611 and an intact SCCmec designated SCCmecBA01611 (Fig. 1a). In addition, three integration site sequences (ISS) comprising directly repeated (DR) sequences were identified in CIBA01611.

FIG 1.

(a) Schematic representation of the composite SCC elements (CIBA01611) in S. aureus BA01611. ORFs are shown as arrows indicating the transcription direction, and the colors of the arrows represent different fragments. Red arrowheads (DR1, DR2, and DR3) indicate the locations of integration site sequences (ISSs). Blue thin arrows indicate primers used to detect excisions. Black thick arrows indicate primers used to close gaps. (b) Comparative structure analyses of CIBA01611 against SCC elements of S. aureus strains JCSC6690, A69, A71, and 1110803248. Homologous gene clusters in different strains are shaded in gray. The characteristics of aligned SCC elements are showed in the inserted table.

BA01611 showed multidrug resistance to oxacillin (MIC = 32 μg/ml), kanamycin (MIC > 256 μg/ml), gentamicin (MIC = 256 μg/ml), penicillin (MIC = 32 μg/ml), erythromycin (MIC > 256 μg/ml), cefoxitin (MIC = 128 μg/ml), neomycin (MIC > 256 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (MIC = 32 μg/ml), and sulfamethoxazole (MIC > 256 μg/ml). However, it was susceptible to vancomycin. In addition, the composite SCC (CIBA01611) in BA01611 did not contain any antibiotic resistance gene other than mecA. This phenomenon seems contradictory to previous reports that composite SCC elements usually contain more resistance genes (14–16). Nevertheless, antibiotic resistance genes such as blaZ, tetL, aacA-aphD, aadD, aadE, lnuB, isaE, and tcaA were found elsewhere to be carried by many insertion sequences (IS256 and IS431) or recombinant plasmids located in the chromosome of BA01611 (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

In order to study the structural organization and genetic contents of the SCCmec in BA01611, predicted open reading frames (ORFs) were analyzed. SCCmecBA01611 was estimated to be 25 kb in size with 31 ORFs and to be demarcated by DR2 and DR3 (Fig. 1a). A novel ccrC allotype (orf37) was identified in SCCmecBA01611, which shared nucleotide identities of 62.6% to 69.4% with the ccrC1 alleles (see Table S3 in the supplemental material). Results from the phylogenetic tree also confirmed that this novel ccrC allotype was phylogenetically distinct from all ccrC1 genes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). According to the proposed criteria from International Working Group on the Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome Elements (3), we gave the novel ccr gene the designation ccrC2. The ccr gene complex (orf32 to orf38) was consequently designated a type 9 complex. This complex had nucleotide identity of 66.2% with the type 5 ccrC gene complex of S. aureus strain JCSC6082 (GenBank accession no. AB373032). This novel ccrC gene complex was further classified as a group 1 ccrC gene complex, according to an additional ccrC classification scheme (17). A class C2-like mec gene complex (orf44 to orf50), composed of ΔIS431-1, ΔmvaS, ugpQ, maoC, mecA, ΔmecR1, and IS431-2 genes, was located downstream of the ccrC gene complex. Unlike the class C2 mec gene complex, the IS431-1 gene was truncated in BA01611. On the basis of the results presented above, SCCmecBA01611 was identified as a novel type XII SCCmec (9C2). The discovery of ccrC2 added a new member to the ccr gene family. Since this novel allotype cannot be detected by the latest SCCmec typing strategy (6), we advocate revision of the SCCmec typing method to include ccrC2 and the type 9 ccr gene complex.

Two type III restriction-modification (RM) system methylation subunits (Mod) (orf51 and orf55) were identified in the SCCmec of BA01611. Defensive systems such as restriction-modification systems are frequently reported in SCCmec of staphylococci and play a crucial role in the stability of certain regions of the S. aureus chromosome (5). While type I and type II RM systems other than the composite SCC (CIBA01611) existed in regions of the chromosome of BA01611, there was no type IV RM system in its chromosome. Type III RM systems appear to be extremely rare in S. aureus and to date have been identified in only two S. aureus isolates, KLT6 and 118 (18).

The ΨSCCBA01611 pseudo-SCC element, carrying 30 ORFs, was immediately downstream of orfX with a length of 24.3 kb and was delineated by DR1 and DR2 (Fig. 1a). ΨSCCBA01611 shared 99.9% nucleotide sequence identity with ΨSCCJCSC6690 in S. aureus strain JCSC6690 (Fig. 1b). An incomplete type 1 ccr gene complex which contained a truncated ccrA1 was identified in ΨSCCBA01611 (Fig. 1a).

CcrAB or CcrC1 can carry out both excision and integrative recombination. Moreover, a CcrA protein has little or no recombination activity on its own and requires a CcrB protein for its functions (19). Interestingly, CcrAB recombinases can excise different types of SCCmec elements, while a CcrC1 recombinase is specific to the type of SCCmec element that contains it (5). Previous research found recombination between two phylogenetically close ccr genes, ccrC1 allele 8 and ccrC1 allele 10, causing loss of the mec gene complex (20). In order to investigate whether excision of SCC elements occurred in BA01611, extrachromosomal circular intermediates of each element situated between DRs were identified by PCR using primer sets of 1R and 1F, 2R and 2F, and 1R and 2F (Fig. 1a). DNA fragments giving positive results were successfully amplified by all primer sets, indicating formation of the circular intermediates from both single SCC elements (SCCmecBA01611 and ΨSCCBA01611) and the composite SCC (CIBA01611). Nucleotide sequencing confirmed that excision of these elements occurred precisely at the DR sites. These results suggest that CcrC2 is functional and responsible for the potential spread of SCC elements in BA01611. Recent studies indicated that horizontal spread of SCCmec is more frequent than was believed before (21, 22). It has been suggested that an increase in expression of the ccrAB genes might be associated with a high frequency of SCCmec excision (14). Higgins et al. (23) found upregulated expression of ccrA in S. aureus under conditions of exposure to β-lactam antibiotics. An in vivo transfer of the SCCmec into a MSSA isolate after β-lactams were used was also observed (24). Therefore, treatment with β-lactams has the potential to promote the transfer of SCCmec. The involvement and regulation of ccrC2 in horizontal transmission of SCCmec need to be further investigated.

A local collection of 97 staphylococcal isolates in our laboratory was used for examining the presence of ccrC2. As shown in Table 1, 26 isolates were positive for ccrC2. The ccrC2 gene was mainly carried by coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), especially S. epidermidis and S. haemolyticus, and was present in both oxacillin-resistant and oxacillin-susceptible isolates. The existence of ccrC2 in staphylococcal species whose data are available in GenBank was also determined by searching the NCBI nr/nt and wgs databases, utilizing the nucleotide sequence of ccrC2 gene as the query. Results showed that the ccrC2 gene was present in eight staphylococcal isolates (3 S. aureus and 5 S. epidermidis), with sequence identities of 90% to 100% to the ccrC2 gene in BA01611 (Table 2). These bacteria were collected from China (2 isolates), the United States (4 isolates), France (1 isolate), and Germany (1 isolate). Among them, S. aureus isolates A69 (China), A71 (China), and 1110803248 (United States) shared 99.9% nucleotide sequence identity with part of CIBA01611 (Fig. 1b), suggesting that the SCC elements in these three isolates as well as in BA01611 shared a closely related ancestor.

TABLE 1.

Staphylococcal isolates which carried the ccrC2 gene from a local collection

| Isolate | Species | ccrC2 | mecA | MIC of oxacillin (μg/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA01611a | S. aureus | + | + | 32 |

| BC03632 | S. aureus | + | − | <0.5 |

| BA00841 | S. epidermidis | + | − | <0.5 |

| BA00821 | S. epidermidis | + | − | <0.5 |

| BA01221 | S. epidermidis | + | − | <0.5 |

| BA01211 | S. epidermidis | + | − | <0.5 |

| BB02612 | S. epidermidis | + | + | 16 |

| BB02622 | S. epidermidis | + | + | 16 |

| BB02632 | S. epidermidis | + | + | 16 |

| BB02642 | S. epidermidis | + | + | 16 |

| BB02441 | S. epidermidis | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC02711 | S. epidermidis | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC03831 | S. epidermidis | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC03841 | S. epidermidis | + | + | 16 |

| BC05311 | S. epidermidis | + | − | <0.5 |

| BA00142 | S. haemolyticus | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC03531 | S. haemolyticus | + | + | 16 |

| BC04121 | S. haemolyticus | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC04131 | S. haemolyticus | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC04141 | S. haemolyticus | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC04821 | S. haemolyticus | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC04531 | S. haemolyticus | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC04621 | S. haemolyticus | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC04631 | S. haemolyticus | + | − | <0.5 |

| BA01931 | S. agnetis | + | − | <0.5 |

| BC04632 | S. warneri | + | − | <0.5 |

BA01611 was coagulase positive, while all of the other isolates were coagulase negative.

TABLE 2.

The presence of ccrC2 in staphylococcal strains represented in GenBank

| Strain | Species | % sequence identity | Country | GenBank accession no |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A69 | S. aureus | 100 | China | JJOP00000000.1 |

| A71 | S. aureus | 100 | China | JJOO00000000.1 |

| 1110803248 | S. aureus | 100 | United States | JJDZ00000000.1 |

| VCU013 | S. epidermidis | 96 | United States | JHTZ00000000.1 |

| VCU014 | S. epidermidis | 96 | United States | JHQB00000000.1 |

| NIH05001 | S. epidermidis | 96 | United States | AKHE00000000.1 |

| 1057 | S. epidermidis | 96 | Germany | JHTZ00000000.1 |

| 12142587 | S. epidermidis | 90 | France | AMSJ00000000.1 |

BA01611 belonged to spa type t899 and ST9. ST9-t899 MRSA isolates predominated in swine farms from four Chinese provinces and could be isolated from two swine workers, indicating its interspecies transmission (25). ST9-t899 MRSA is the major livestock-associated MRSA (LA-MRSA) strain in pigs in China (26). On the other hand, ST398 strains are the most frequently found LA-MRSA strains in human and animal hosts in European countries and North America (27, 28) and have been reported less frequently in China (29). Considering the fact that LA-MRSA ST9 appears to be capable of spreading the resistance phenotype to humans, proliferation of ST9 MRSA isolates carrying type XII SCCmec in staphylococci from cows could pose a threat to both animal and human health.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation of China (grant number 31372282), by the China Thousand Talents program, and by two University Scientific Research Fund projects (Fund number Z111021305 and Fund number Z109021431). This work was also partially supported by a discovery grant from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01692-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chatterjee SS, Otto M. 2013. Improved understanding of factors driving methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus epidemic waves. Clin Epidemiol 5:205–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ito T, Katayama Y, Hiramatsu K. 1999. Cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the entire mec DNA of pre-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus N315. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43:1449–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Working Group on the Classification of Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome Elements (IWG-SCC). 2009. Classification of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec): guidelines for reporting novel SCCmec elements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4961–4967. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00579-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Archer GL. 2010. Roles of CcrA and CcrB in excision and integration of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec, a Staphylococcus aureus genomic island. J Bacteriol 192:3204–3212. doi: 10.1128/JB.01520-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito T, Ma XX, Takeuchi F, Okuma K, Yuzawa H, Hiramatsu K. 2004. Novel type V staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec driven by a novel cassette chromosome recombinase, ccrC. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:2637–2651. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2637-2651.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito T, Kuwahara-Arai K, Katayama Y, Uehara Y, Han X, Kondo Y, Hiramatsu K. 2014. Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) analysis of MRSA. Methods Mol Biol 1085:131–148. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-664-1_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2004. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals; informational supplement. M31-S1. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saunders NA, Holmes A. 2014. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) of Staphylococcus aureus. Methods Mol Biol 1085:113–130. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-664-1_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harmsen D, Claus H, Witte W, Rothganger J, Claus H, Turnwald D, Vogel U. 2003. Typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a university hospital setting by using novel software for spa repeat determination and database management. J Clin Microbiol 41:5442–5448. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.12.5442-5448.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z, Schwartz S, Wagner L, Miller W. 2000. A greedy algorithm for aligning DNA sequences. J Comput Biol 7:203–214. doi: 10.1089/10665270050081478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD, Reich C, Stevens R, Vassieva O, Vonstein V, Wilke A, Zagnitko O. 2008. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. 2010. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One 5:e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. 2011. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer. Bioinformatics 27:1009–1010. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito T, Katayama Y, Asada K, Mori N, Tsutsumimoto K, Tiensasitorn C, Hiramatsu K. 2001. Structural comparison of three types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec integrated in the chromosome in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:1323–1336. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1323-1336.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lulitanond A, Ito T, Li S, Han X, Ma XX, Engchanil C, Chanawong A, Wilailuckana C, Jiwakanon N, Hiramatsu K. 2013. ST9 MRSA strains carrying a variant of type IX SCCmec identified in the Thai community. BMC Infect Dis 13:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xue H, Wu Z, Li L, Li F, Wang Y, Zhao X. 2015. Coexistence of heavy metal and antibiotic resistance within a novel composite staphylococcal cassette chromosome in a Staphylococcus haemolyticus isolate from bovine mastitis milk. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:5788–5792. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04831-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chlebowicz MA, van Dijl JM, Buist G. 2011. Considerations for the distinction of ccrC-containing staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1823–1824. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00107-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadykov MR. 3 February 2015, posting date. Restriction-modification systems as a barrier for genetic manipulation of Staphylococcus aureus. Methods Mol Biol doi: 10.1007/7651_2014_180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misiura A, Pigli YZ, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum RS, Boocock MR, Rice PA. 2013. Roles of two large serine recombinases in mobilizing the methicillin-resistance cassette SCCmec. Mol Microbiol 88:1218–1229. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chlebowicz MA, Nganou K, Kozytska S, Arends JP, Engelmann S, Grundmann H, Ohlsen K, van Dijl JM, Buist G. 2010. Recombination between ccrC genes in a type V (5C2&5) staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) of Staphylococcus aureus ST398 leads to conversion from methicillin resistance to methicillin susceptibility in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:783–791. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00696-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanssen AM, Ericson Sollid JU. 2006. SCCmec in staphylococci: genes on the move. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 46:8–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2005.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson DA, Enright MC. 2003. Evolutionary models of the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:3926–3934. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3926-3934.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins PG, Rosato AE, Seifert H, Archer GL, Wisplinghoff H. 2009. Differential expression of ccrA in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type II and IVa elements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4556–4558. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00395-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wielders CL, Vriens MR, Brisse S, de Graaf-Miltenburg LA, Troelstra A, Fleer A, Schmitz FJ, Verhoef J, Fluit AC. 2001. In-vivo transfer of mecA DNA to Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1674–1675. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04832-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui S, Li J, Hu C, Jin S, Li F, Guo Y, Ran L, Ma Y. 2009. Isolation and characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from swine and workers in China. J Antimicrob Chemother 64:680–683. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho PL, Chow KH, Lai EL, Law PY, Chan PY, Ho AY, Ng TK, Yam WC. 2012. Clonality and antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus isolates from food animals and other animals. J Clin Microbiol 50:3735–3737. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02053-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith TC, Male MJ, Harper AL, Kroeger JS, Tinkler GP, Moritz ED, Capuano AW, Herwaldt LA, Diekema DJ. 2009. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain ST398 is present in midwestern U.S. swine and swine workers. PLoS One 4:e4258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witte W, Strommenger B, Stanek C, Cuny C. 2007. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in humans and animals, Central Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 13:255–258. doi: 10.3201/eid1302.060924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chuang YY, Huang YC. 2015. Livestock-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Asia: an emerging issue? Int J Antimicrob Agents 45:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.