Abstract

Background:

Nausea and vomiting are the most common complicated issues in pregnancy period, but they have not been paid much attention. Herb based formulations can be effectively used for the treatment nausea and vomiting observed during pregnancy.

Aim:

To investigate the effect of ginger in nausea and vomiting during pregnancy in comparison with vitamin B6 and placebo.

Materials and Methods:

This is a randomized and double-blind clinical trial. The women who had nausea and vomiting and did not take any medications were included in this study. 120 women were selected by simple random sampling method, and divided into three groups and were given vitamin B6, placebo, and ginger, respectively. 97 women completed the treatment. They were given treatment for 4 days and were followed after a week. The instrument used in this study was a questionnaire, including demographic characteristic and determining severity nausea and vomiting based on the analog visual scale. Data were analyzed with SPSS software and t-test and Kruskal-Wallis test.

Results:

There was significant difference between groups in severity of nausea and frequency of vomiting (P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Ginger was effective in treating nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, but its use needs further studies to determine the proper dosage and the confirmation about the safety of this drug for a pregnant mother and her fetus.

Keywords: Ginger, nausea, placebo, pregnancy, vitamin B6, vomiting

Introduction

Nausea and vomiting are the most common complaints during pregnancy and are approximately experienced by 70–80% of pregnant women.[1,2,3] This condition usually begins at week 4–8 after menstruation and is more severe at 9th week. It starts to decrease in the following weeks and in most cases, improves until the 14th week; however, it continues during the whole pregnancy in 2% of the cases.[4,5]

Although the disorder is mild to moderate in most cases, it causes undesirable condition and discomfort. In recent times, maternal mortality for this cause is extremely rare and has a prevalence of about 0.5%; however, it is the most common reason for mothers’ hospitalization in the first few weeks of the pregnancy.[4] In spite of the fact that nausea and vomiting are considered to be gestational complications, the remarkable point is a good pregnancy outcome in subjects with these complications that they are less likely to undergo abortion and/or low birth weight.[6]

Since gestational nausea and vomiting can be gradually decreased and improved, the treatment takes longer in most women and is usually symptomatic.[7] Depends on the severity of symptoms, management course will be different, and it can be different from a simple change on diet to hospitalization and even receiving total parenteral nutrition.[6] Different methods of treatment are available. Vitamin B6, antihistamines or H1 -receptor antagonists (diphenhydramine, diphenhydranate), dopamine blockers (metoclopramide) and corticosteroids, as the last step of treatment in severe cases, are used.[8] Given the fear of teratogenicity effects, pregnant women do not have the tendency to use of chemical drugs during pregnancy. Following the thalidomide tragedy and the incidence of major malformations, limitations have been taken seriously during pregnancy, although the rational use of drugs seems to be necessary and sensible in many cases.[9]

Recently, much attention has been paid to herbal medicine as a therapeutic approach. Garlic, chamomile, peppermint, sea oak and ginger are used to treat gestational nausea and vomiting.[1,2,10] As a spice, ginger (Zingiber officinale) has a long history in food and pharmaceutical applications and is widely used in traditional medicine, especially in China, Japan, India, and Iran to treat various diseases, particularly nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.[11,12] In different studies, ginger has been used as a treatment for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.[13,14] No cases of abortion or increase in birth deficit and maternal complications have been observed following ginger administration.[2,4,12,13,14,15]

Among the available forms of ginger, ginger tea, biscuits, and capsule can be enumerated.[2] Consumption of the latter is easier for stomach and contains dry form of ginger which is more effective than its fresh root.[12]

In this regard, the present study was conducted to compare the effects of vitamin B6, ginger and placebo in treatment of gestational nausea and vomiting among pregnant women.

Materials and Methods

The present randomized double-blind clinical trial was conducted on 120 pregnant women who were referring to health centers in Amol/Iran. Selection was by simple random sampling method. This trial was approved by Institutional Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University of Babol/Iran (Vide reference number: 1025-12/14/2010). A consent letter based on subject's willingness and interest to participate in the study and continue strictly for four consecutive days was obtained.

Inclusion criteria

Subjects of age 18–35 years, gestational age <20 weeks and experiencing nausea with or without vomiting were included.

Exclusion criteria

Pregnant women with specific diseases or problems such as high blood pressure, epilepsy, diabetes, known sensitivity to ginger, and the ones in need of hospitalization due to severe nausea and vomiting and also those with no possibility to be followed-up were excluded from the study.

Test drug and posology

Ginger capsule (Zintoma, 250 mg), Vitamin B6 (40 mg) orally and placebo (sugar 40 mg) were coded and packed in similar coverings in Pharmacology Laboratory. Zintoma contains dry powder zingiber rhizome. The active ingredients of zintoma are: Alkaloids (e.g. Gentialutine, gentianine), glycosides (anaroswerin, amaropanin), volatile oils (bisabolene, zingiberene, gingerols, zingiberole).[10]

Then the codes were given to the laboratory coordinator, so that the patients and the investigator could not be aware of the types of the medicines which were used. The selected subjects for intervention were assigned to three groups.

The medicines were given to the participants and they were instructed by investigators to take one capsule each 6 h in day for 4 consecutive days. They were also given required information regarding their proper diet and avoiding of high-fat food intake.

Assessment criteria

The intervention study was done based on pre- and post-assessment for the following parameters: Preliminary assessment included assessment for severity of nausea and vomiting. Nausea as a subjective symptom was investigated using two scales including visual analogue and Likert scale. Visual analog scale (VAS) is a 10-cm line divided from 0 (indicating no nausea) to 10 (severe nausea) that participant showed the severity of their nausea.

The frequency of nausea and vomiting was also determined based on recording the plus sign (+) 24 h before and during the treatment period. One week after the drug administration, the response to the treatment was evaluated by Likert scale. The mean daily nausea in three groups was compared before and after treatment using Kruskal-Wallis test.

Data were analyzed by SPSS statistical software version # 16 using t-test, Kruskal-Wallis, and Fisher's tests at P < 0.05 level.

Observations and Results

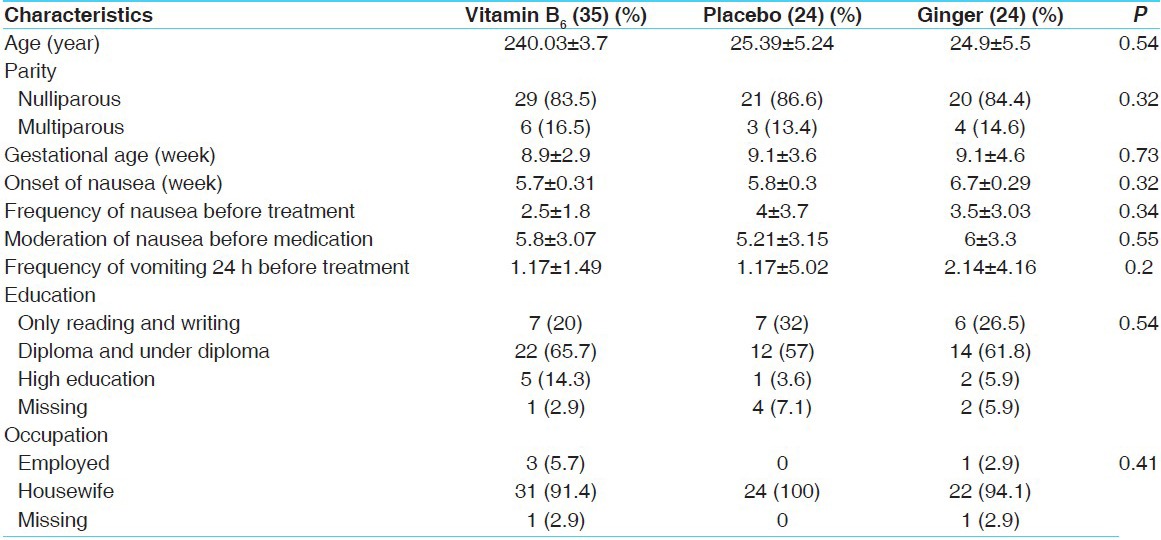

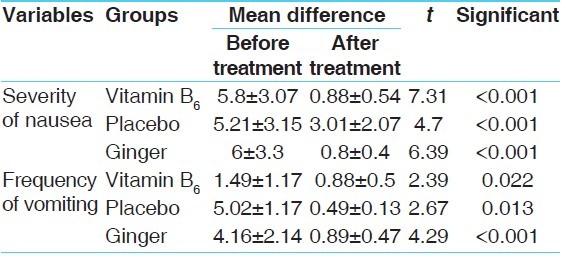

Initially, 120 women selected and divided into three groups (40 women in each groups), but 23 women dropped out from the study because they did not continue treatment. 97 women (vitamin B6 = 35, placebo = 28, ginger [zintoma] =24) were included in the study. The participants’ demographic characteristics were determined in three groups and there was no significant difference. The mean nausea and vomiting was determined before intervention in all three study groups. The severity and the frequency of nausea as well as the frequency of vomiting showed no remarkable difference before treatment in three groups [Table 1]; whereas, the mean severity and the frequency of nausea and vomiting revealed significant reduction in all three groups after intervention [Table 2].

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the intervention groups

Table 2.

Comparison of the severity of nausea and vomiting before and after treatment period

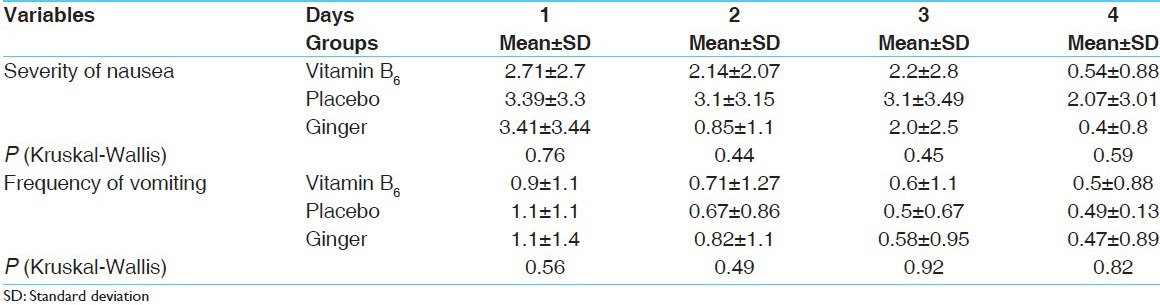

Comparison of the severity of nausea and vomiting during the treatment days did not show significant difference between the three groups; however, the severity of nausea in placebo group was higher than that of the ginger and vitamin B6 groups during the treatment [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of the severity of nausea and vomiting during treatment period among different groups

One week after the treatment initiation, participants’ treatment status was evaluated by Likert scale. It is evident from the results that severity of symptoms reduced dramatically in 60.6, 42.7 and 61% of ginger, placebo and B6 group, respectively; although, severity of the symptoms in some of the subjects worsened (32.2, 8.8 and 18.3% in placebo, B6 and ginger group respectively). 46% of placebo recipients versus 16% of B6 and 27.6% of ginger recipients developed problems such sever nausea and vomiting, stomachache and heartburn during the treatment. Severity of nausea and vomiting in placebo group in some cases led to medicines discontinuation and the use of other treatment methods. Stomachache, heartburn and increased nausea were also reported in 10.2% of ginger recipients.

Discussion

The history of migraine headaches, fatty-food intake before pregnancy, female fetus, early gestational age, first pregnancy, obesity, stress, history of nausea in previous pregnancies in mother and sisters, and housework are predisposing factors for the nausea in pregnancy.[7]

Being concerned about the occurrence of abnormalities in fetus due to drug administration, especially during the first month of pregnancy, the pregnant women and their families have been led to higher tendency toward the use of herbal medications.[11,16] Dissatisfaction toward the new medical treatments in terms of the adverse effects of chemical drugs is notable on the other hand using traditional methods contributes to significant reduction in medical costs, easy access and a descend in terms of the side-effects.[17]

According to the results of present study, a safe 4 days treatment with 1000 mg of ginger daily improved the signs of nausea and vomiting in pregnant women. Doses ranging from 1000 to 1500 mg ginger have been used during pregnancy.[3,18,19] A safe dose of 1000 mg daily proposed in previous studies[20,21] for the treatment of pregnancy-related nausea and vomiting. In present investigation no significant difference has been observed between the effectiveness of ginger, vitamin B6 in reducing nausea and vomiting of pregnancy (P = 0.59). The findings are consistent with other clinical studies.[9,15,22]

It seems that impact of ginger in treating nausea and vomiting is caused by anti-cholinergic as well as anti-histamine properties.[10,16]

The most common side-effect in administration of ginger rhizome is the gastrointestinal effect, because increased in desquamation of gastric epithelial cells.[9] The components of ginger responsible for its medicinal value–gingetol and shogaol–have only local effects on the gastrointestinal system, whereas many pharmaceutical anti-nausea agents have effects on the central nervous system (CNS).[23] In this study, 10.2% of ginger recipients were affected during the treatment. Stomachache and heartburn were the main problems identified immediately after administration of ginger. In previous research work stomachache and dizziness was reported as the side effects of ginger in 6% of recipients.[24] Similarly, stomachache was reported in 9.4% of ginger recipients in another study.[18]

It seems pungent odor and taste medicinal form of many herbal medicines such as ginger is a problem in consuming; hence, applying more appropriate forms of medication (e.g., tablets) may facilitate the use of these compounds.

Conclusion

According to the results ginger is as effective as B6 in reducing gestational nausea and vomiting which can be used as a simple, accessible, and convenient approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank of all the pregnant women that participated in this study. Special thanks go to Mr. Akbar Nattaj and Mrs. Mohamad Khaniha and Babaei for their cooperation in collecting data.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Abolghasemi S, Razmjoo N. Effectiveness of ginger in nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2004;6:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jewell D, Young G. WITHDRAWN: Interventions for nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;8(9):CD000145. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000145.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vutyavanich T, Kraisarin T, Ruangsri R. Ginger for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy: Randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:577–82. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrelli F, Capasso R, Aviello G, Pittler MH, Izzo AA. Effectiveness and safety of ginger in the treatment of pregnancy-induced nausea and vomiting. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:849–56. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000154890.47642.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacroix R, Eason E, Melzack R. Nausea and vomiting during pregnancy: A prospective study of its frequency, intensity, and patterns of change. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:931–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70349-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Portnoi G, Chng LA, Karimi-Tabesh L, Koren G, Tan MP, Einarson A. Prospective comparative study of the safety and effectiveness of ginger for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1374–7. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00649-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis M. Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy: An evidence-based review. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2004;18:312–28. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conover EA. Over-the-counter products: Nonprescription medications, nutraceuticals, and herbal agents. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45:89–98. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200203000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ozgoli G, Goli M, Simbar M. Effects of ginger capsules on pregnancy, nausea, and vomiting. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:243–6. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Samsam Shariat H. 1st ed. Isfahan: Maney Publisher; 1995. Medicinal Plant; pp. 183–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant KL, Lutz RB. Ginger. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2000;57:945–7. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/57.10.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pizzorno J, Murray M. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. Text Book of Natural Medicine; pp. 1025–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammadbeigi R, Shahgeibi S, Soufizadeh N, Rezaiie M, Farhadifar F. Comparing the effects of ginger and metoclopramide on the treatment of pregnancy nausea. Pak J Biol Sci. 2011;14:817–20. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2011.817.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heitmann K, Nordeng H, Holst L. Safety of ginger use in pregnancy: Results from a large population-based cohort study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69:269–77. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1331-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willetts KE, Ekangaki A, Eden JA. Effect of a ginger extract on pregnancy-induced nausea: A randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43:139–44. doi: 10.1046/j.0004-8666.2003.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Achi A. A current look at ginger use. [Last retrieved on 2007 Aug 02]. Available from: http://www.uspharmacist.com .

- 17.Nasseri M. Development of traditional medicine based on W.H.O guidance. Daneshvar Med J. 2004;11:53–66. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sripramote M, Lekhyananda N. A randomized comparison of ginger and vitamin B6 in the treatment of nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86:846–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer-Rasmussen W, Kjaer SK, Dahl C, Asping U. Ginger treatment of hyperemesis gravidarum. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991;38:19–24. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90202-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzotta P, Magee LA. A risk-benefit assessment of pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments for nausea and vomiting of pregnancy. Drugs. 2000;59:781–800. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hollyer T, Boon H, Georgousis A, Smith M, Einarson A. The use of CAM by women suffering from nausea and vomiting during pregnancy. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2002;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith C. Ginger reduces severity of nausea in early pregnancy compared with vitamin B6, and the two treatments are similarly effective for reducing number of vomiting episodes. Evid Based Nurs. 2010;13:40. doi: 10.1136/ebn1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blumental M. Austin: American Botanical Council; 1998. The Complete German Commission E Monographs; p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharifi A. Survey of effective of ginger cookies on nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy. The Thesis of Medicine. Babol University of Medical Science. 2003 [Google Scholar]