Abstract

Despite significant advancements in the treatment and outcome of hematologic malignancies, prognosis remains poor for patients who have relapsed or refractory disease. Adoptive T-cell immunotherapy offers novel therapeutics that attempt to utilize the noted graft versus leukemia effect. While CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells have thus far been the most clinically successful application of adoptive T immunotherapy, further work with antigen specific T cells and CARs that recognize other targets have helped diversify the field to treat a broad spectrum of hematologic malignancies. This article will focus primarily on therapies currently in the clinical trial phase as well as current downfalls or limitations.

Keywords: antigen-specific T cells, chimeric antigen receptor, cytotoxic T lymphocytes, immunotherapy

Introduction

Significant advancements have been made in terms of survival and treatment modalities for hematologic malignancies in recent decades. Survival rates exceed 90% for many hematologic malignancies. Despite impressive survival rates, patients incur many systemic toxicities and late effects from conventional therapies such as chemotherapy and radiation. Furthermore, outcomes for patients who do not obtain remission or who relapse are generally dismal. These patients often require allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation (HSCT) but may not have a suitable donor source or be a good candidate for HSCT. Prognosis is even worse when relapse occurs following HSCT. Immunotherapy offers novel therapeutics for patients whose disease has failed to respond to conventional treatment modalities including HSCT (or who are unsuitable for HSCT) while also potentially reducing systemic toxicities and late effects.

The therapeutic advantage for T-cell immunotherapy arises from the graft versus leukemia (GVL) effect noted after HSCT. Donor lymphocyte infusions (DLIs) have been used to amplify this effect as first described in 1990 when patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) with relapsed disease post HSCT achieved cytogenetic and molecular remission following DLI [Kolb et al. 1990]. However, DLI carries the risk of graft versus host disease (GVHD) and also has not been as effective in acute leukemia [Nikiforow and Alyea, 2014]. Adoptive T-cell immunotherapy techniques such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and tumor-associated-antigen (TAA) T cells attempt to harness the GVL effect while minimizing the risk of GVHD.

T cell–tumor interaction

T cells’ natural ability to distinguish between self and foreign particles is essential to their role in cancer immunotherapy. If T cells are able to identify tumor cells as foreign and bind tumor antigens with strong avidity, they can then mediate cell lysis and apoptosis. However, many tumor antigens are only weakly immunogenic and thus do not mount a robust T-cell response. Tumors may also downregulate expression of tumor antigens to escape T-cell recognition. Thus, adoptive T-cell immunotherapy enhances T cells’ innate ability through modifications that attempt to overcome tumors’ evasive mechanisms.

Nongene-modified T cells for hematologic malignancies

The basis for adoptive immunotherapy with nongene-modified T cells arises from the use of DLIs for leukemia relapses post HSCT as a way to bolster the GVL effect. While DLIs have induced sustained remissions in patients with CML with relapsing disease post HSCT, this technique has been much less successful in acute leukemias likely secondary to their rapid proliferation while DLI effects take months to achieve full benefit [Deol and Lum, 2010]. Furthermore, very large cell doses are needed in acute leukemias, which dramatically increases the risk of GVHD [Deol and Lum, 2010].

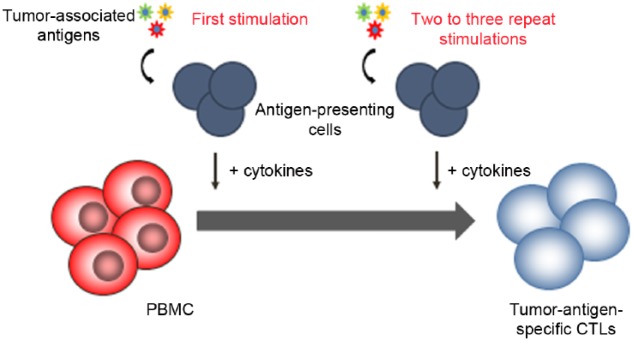

The success of DLI has prompted further work to harness the GVL effect while using T cells more specific than DLI through the use of ex vivo generated tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Ex vivo generated CTLs were initially designed to treat viral infections post HSCT. Building upon these principles, tumor-specific CTLs have emerged through a process that entails repeated stimulations with antigens to expand T cells that are specific for tumor cells [Bollard et al. 2004] (see Figure 1). Antigens used include minor histocompatibility antigens, viral-specific antigens, and leukemia-specific antigens.

Figure 1.

Generation of tumor-antigen specific cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTLs). Antigen-presenting cells are pulsed with peptide mixtures of tumor-associated antigens and used to stimulate T cells in the presence of cytokines to select and expand tumor antigen specific T cells. PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Gene modified T cells for hematologic malignancies

CAR-modified T cells

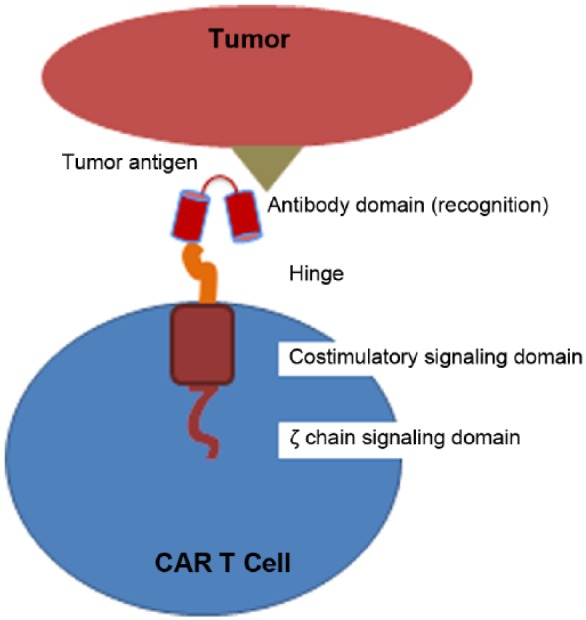

CAR-modified T cells have been used as both a bridge to transplant and as treatment for relapsed disease or as an adjuvant therapy for high-risk patients post-HSCT. CAR-modified T cells as first described by Eshhar and colleagues can theoretically recognize any target (i.e. not only proteins) in an human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-independent manner with significantly enhanced potency [Gross et al. 1989]. These receptors are composed of an extracellular recognition domain (usually derived from the variable regions of an antibody) coupled to intracellular signaling domains that combine both signal 1 (T-cell receptor complex) and signal 2 (costimulatory molecule signaling) from the T cells [Finney et al. 1998; Maher et al. 2002] (see Figure 2). As discussed below, the clinical utility of the CAR approach is highlighted by remarkable clinical responses using CD19-CAR modified T cells, especially for the treatment of pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). However, major concerns exist, including significant and potentially life-threatening toxicities associated especially with CAR-CD19 T cell-mediated cytokine release syndrome in patients with high disease burden and the risk of tumor antigen loss when targeting a single TAA leading to relapse.

Figure 2.

Structure of (second-generation) chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cell. CAR construct comprises an extracellular recognition domain (e.g. single chain variable fragment derived from an antibody) coupled to an intracellular signaling domain (e.g. T-cell receptor ζ signaling chain coupled to a costimulatory signaling domain).

T-cell receptor modified T cells

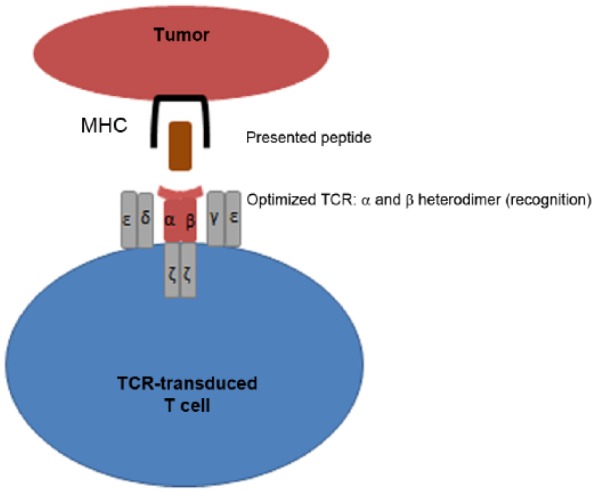

T-cell receptors (TCRs) confer high specificity onto their T cells, and the genetic modification of the TCR complex onto other cells is the basis of αβ TCR gene transfer (see Figure 3). However, concerns with the TCR gene transfer are the limitations of an HLA-restricted approach targeting a single TAA epitope and potential mispairing that may occur between endogenous TCRs and the introduced TCR. Mispairing can either decrease the effectiveness of the therapy, or the new TCR may recognize self proteins and potentially cause harmful alloreactivity [Cameron et al. 2013; Linette et al. 2013; Schumacher, 2002]. Bendle and colleagues demonstrated in a mouse model that lethal transfer-induced GVHD can occur secondary to this cross pairing [Bendle et al. 2010]. However, clinically significant cross-pairing-mediated toxicity has not yet occurred in human clinical trials [Morgan et al. 2006; Johnson et al. 2009; Rosenberg, 2010].

Figure 3.

Structure of T-cell receptor (TCR)-transduced T cell demonstrating modified TCR complex with optimized α and β chains that bind with high affinity and additional modifications to ensure no mispairing with endogenous chains. MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

Clinical experience using T cells for hematologic malignancies

Nongene-modified T cells

Antigen-specific T cells targeting viral antigens

Some tumors express viral antigens with Epstein Barr virus (EBV)-associated lymphomas being the most common. After primary infection, EBV remains in a latent state in B cells in most immune competent hosts, but immunocompromised hosts following solid organ transplant and HSCT are susceptible to an EBV-driven lymphoproliferation termed post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD). While DLIs can restore T-cell immunity and eradicate PTLD, this method carries a high risk of GVHD [O’Reilly et al. 1996]. Donor-derived EBV CTLs were infused prophylactically in 101 patients post transplant to prevent PTLD. None of these patients developed PTLD compared with an incidence of 11.5% in the historical cohort. Furthermore, in 11 of 13 patients who had already developed PTLD, complete remission (CR) was obtained after receiving EBV CTLs [Heslop et al. 2010]. Given the overwhelming effectiveness of EBV CTLs for PTLD, Haque and colleagues investigated whether this therapy could be made more readily available by using third-party, allogeneic EBV CTLs matched through at least one HLA type [Haque et al. 2010]. Early trials found a 52% response rate at 6 months. A good manufacturing practice (GMP)-compliant, third-party, EBV-specific CTL bank was established and in its first 2 years of operation, EBV-specific CTLs were administered to 10 patients with PTLD, 8 of whom have had a CR [Vickers et al. 2014].

EBV-associated malignancies can also occur in the immune-competent host. Tumor cells in around 40% of Hodgkin lymphomas (HLs) and non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) express the type II latency EBV antigens latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) and LMP2. Bollard and colleagues infused LMP CTLs into patients either with persistent disease or at high of relapse [Bollard et al. 2014]. In both patient cohorts, there was no toxicity associated with LMP-CTL infusion. In patients with persistent disease at the time of LMP-CTL infusion, 11 of 21 patients attained CR. For the 29 patients receiving LMP CTLs due to high risk of relapse, 27 patients remained in remission with a CR median of 2.5 years. This study demonstrates both the efficacy and safety of LMP CTLs for EBV-associated malignancies.

Antigen-specific T cells targeting nonviral antigens

However, many hematologic malignancies do not express a viral-associated antigen that can be targeted in adoptive immunotherapy. Tumor antigens are typically self proteins that are mostly weakly immunogenic, and most T cells do not have the receptors capable of avidly binding to self antigens as a means of avoiding possible autoimmune reactions [Janeway et al. 2005]. However, Falkenburg and colleagues [1999] demonstrated that remission could be induced in a patient with CML and leukemia-reactive CTL lines, prompting further work in this field.

As the GVL effect in HLA-identical HSCT is thought to be secondary to T cells that recognize recipient minor histocompatibilty antigens (mHAg), the role of mHAg CTLs in adoptive immunotherapy has been studied [Bleakley and Riddell, 2011]. A phase I study infused seven patients with relapsed leukemia post-HSCT with mHAg-specific CTLs. Five of the infused patients attained CR after cytoreductive chemotherapy, withdrawal, or reduction of immune suppression, and infusion of mHAg-specific CTLs. Of note, three patients had persistent disease after chemotherapy and only obtained remission with CTL infusion. However, all five patients subsequently had relapsing disease. Furthermore, grade 3 or 4 pulmonary toxicities developed in three patients [Warren et al. 2010]. Despite its initial promises, manufacturing mHAg CTLs has proven to be time consuming and expensive, and not readily applicable to a diverse range of patients and malignancies.

Given the limitations of mHAg CTLs, others have sought to create tumor-associated-antigen T cells that would be applicable to a broad range of hematologic malignancies. Wilms Tumor antigen 1 (WT1) is a transcription factor overexpressed by leukemia cells as it is expressed in 70–90% of acute leukemias [Brieger et al. 1994; Menssen et al. 1995; Rezvani et al. 2007]. Chapuis and colleagues infused 11 patients post HSCT with HLA-A*0201-restricted WT1-specific donor-derived CD8+ T cell clones [Chapuis et al. 2013]. Two patients with evidence of disease at the time of CTL infusion had clinical responses, and three patients who were at high risk for relapse remained in CR. Based on previous studies that showed interleukin (IL)-21 may improve T-cell persistence and proliferation by promoting expansion of less terminally differentiated T cells [Hinrichs et al. 2008; Li et al. 2005], T cells for four patients were generated in the presence of IL-21 once it became available for clinical/GMP use. Improved persistence and proliferation was noted in the subset of T-cell lines generated using IL-21 in vitro. However, only a quarter of patients who received T cells generated with IL-21 had detectable leukemia at the time of T cell infusions compared with 5/7 who received T cells generated without IL-21. Though the sample size is too small to draw definitive conclusions, the only patient with a detectable leukemia burden at the time of CTL infusion who remained alive and in remission at the time of follow up received CTLs generated in the presence of IL-21.

To increase the effectiveness and applicability of TAA CTLs, several groups have recognized the advantage of developing polyclonal and polyfunctional T cells that target multiple tumor antigens in a single cell therapy product. Gerdemann and colleagues have been successful in generating T cells from healthy donors and patients with lymphoma that target multiple TAAs [SSX2, melanoma-associated antigen A4 (MAGEA4), survivin, PRAME, and NY-ESO-1)] present in EBV-negative HL and NHL [Gerdemann et al. 2011]. These multi-TAAs CTLs show in vitro cytolytic activity against autologous lymphoma cells but have not yet been tested in a human model. Similarly, Weber and colleagues generated multi-TAA-specific CTLs from healthy donors targeting myeloid malignancy antigens (proteinase 3, preferentially expressed antigen in melanoma, WT1, human neutrophil elastase and melanoma-associated antigen A3) [Weber et al. 2013b]) and T cells specific for WT1, MAGEA3, PRAME, and survivin from patients with ALL on maintenance therapy [Weber et al. 2013a]. In both studies, the multi-TAA specific T cells showed cytolytic activity against leukemia blasts [Weber et al. 2013a, 2013b]. Phase I clinical trials are currently underway: Baylor College of Medicine group using multi-TAA-specific CTLs that target five antigens commonly expressed in lymphoma: PRAME, SSX2, MAGEA4, NY-ESO-1, and survivin [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01333046]; and CNMC using multi-TAA-specific T cells targeting three antigens commonly expressed in leukemias: WT1, survivin, PRAME [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02203903]. Building upon a successful case report of using bcr-abl CTL for CML [Bornhauser et al. 2006], a group in Dresden prophylactically infused 14 patients with CML post HSCT with donor-derived multi-TAA CTLs (WT1, PR1, and bcr-abl). At a median of 45 months follow up, 13 of 14 patients were alive, and 7 patients remained in molecular remission [Bornhauser et al. 2011].

Gene-modified T cells for hematologic malignancies

CD19-chimeric antigen receptor modified T cells for leukemia and lymphoma

Arguably, the most remarkable experience to date is the use of CD19 CAR-modified T cells for the treatment of patients with CD19+ B-cell malignancies (Table 1). Early experiences with CD19 CAR T cells were limited by a general lack of persistence that coincided with poor clinical responses. These cells incorporated so-called ‘first-generation’ CARs, which only used the TCR ζ chain as the sole signaling domain [Jensen et al. 2010]. Subsequent studies suggested that the addition of costimulatory molecules in the construct (i.e. ‘second-generation’ CARs) could provide improved persistence and antitumor activity in vivo [Kowolik et al. 2006]. In a proof of principle study, the group at Baylor College of Medicine infused two populations of T cells: T cells expressing a first-generation CD19 CAR, and T cells expressing a second-generation CD19 CAR including the CD28 costimulatory domain to patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) or NHL. The study conclusively demonstrated that T cells modified with the second-generation CAR persisted longer than T cells modified with the first-generation CAR. Hence, this study showed that costimulation will enhance CAR T-cell proliferation and persistence in vivo. However, the overall efficacy of the CAR T cells in this study was limited [Savoldo et al. 2011].

Table 1.

Current open clinical trials for CD19-targeted CAR therapy.

| ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Center | Indication* |

|---|---|---|

| NCT02134262 | Jichi Medical University (Japan) | Relapsed or refractory B-cell NHL |

| NCT02247609 | Peking University (China), University of Florida (USA) | Relapsed or refractory CD19(+) B-cell lymphoma |

| NCT02051257 | City of Hope Medical Center (USA) | Relapsed or refractory B-Cell NHL |

| NCT01815749 | City of Hope Medical Center (USA) | Recurrent or high-risk B-cell NHL |

| NCT01865617 | Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (USA) | Recurrent or relapsed CLL, NHL, or ALL |

| NCT00924326 | National Cancer Institute (USA) | Any CD19+ B-cell malignancy |

| NCT00586391 | Baylor College of Medicine (USA) | B-cell NHL, ALL, or CLL |

| NCT02050347 | Baylor College of Medicine (USA) | B-cell NHL, ALL, or CLL |

| NCT02081937 | Chinese PLA General Hospital (China) | Relapsed or refractory MCL |

| NCT01683279 | Seattle Children’s Hospital (USA) | Relapsed ALL (pediatric) |

| NCT02153580 | City of Hope Medical Center (USA) | Stratum 1: NHL |

| Stratum 2: CLL, PLL, SLL | ||

| NCT02146924 | City of Hope Medical Center (USA) | ALL |

| NCT01593696 | National Cancer Institute | Refractory or relapsed B ALL or lymphoma |

| NCT00840853 | Baylor College of Medicine | B ALL, NHL, or CLL |

| NCT02028455 | Seattle Children’s Hospital | CD19+ leukemia |

| NCT01864889 | Chinese PLA General Hospital (China) | CD19+ leukemia or lymphoma |

| NCT01853631 | Baylor College of Medicine (USA) | B-cell NHL, ALL, CLL |

| NCT01087294 | National Cancer Institute (USA) | Any B-cell malignancy |

| NCT01475058 | Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (USA) | Any B-cell malignancy |

| NCT01195480 | University College, London (England) | CD19+ precursor B-cell ALL with EBV seropositive HSCT donor |

| NCT00709033 | Baylor College of Medicine (USA) | NHL, CLL |

| NCT02277522 | Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania (USA) | HL |

| NCT02349698 | Southwest Hospital (China) | Relapsed or refractory ALL, CLL, or NHL |

| NCT01430390 | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (USA) | CD19+ leukemia |

| NCT02348216 | Kite Pharma (USA) | DLBCL, PMBCL, TFL |

| NCT02132624 | Uppsala University (Sweden) | Relapsed or refractory CD19+ B-cell leukemia or lymphoma |

| NCT01840566 | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (USA) | Aggressive B-cell NHL |

| NCT01860937 | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (USA) | Refractory or relapsed CD19+ ALL |

| NCT02030847 | Abramson Cancer Center of the University of Pennsylvania (USA) | Refractory or relapsed CD19+ ALL |

| NCT01626495 | Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (USA) | CD19+ leukemia or lymphoma |

| NCT01318317 | City of Hope Medical Center (USA) | High-risk, intermediate grade B-cell NHL |

| NCT00466531 | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (USA) | CLL, low-grade B-cell neoplams |

All trials included inclusion criteria that neoplasm must be CD19+.

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PLL, B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia; PMBCL, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; TFL, transformation follicular lymphoma.

Subsequent studies then evaluated how to improve the efficacy of this approach. The group at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) used a defined lymphodepletion regimen prior to T-cell infusion to enhance persistence of CAR T cells by eliminating competing endogenous cells [Kochenderfer et al. 2010; Rosenberg, 2011]. The lymphodepleting regimen consisted of cyclophosphamide and fludarabine prior to infusion of T cells genetically modified with a retroviral vector expressing the second-generation CD19 CAR containing the CD28 costimulatory domain. Eight patients with progressive B-cell malignancies (CLL and follicular lymphoma) were enrolled with six clinical responses seen [Kochenderfer et al. 2012]. More recently, impressive results have also been seen in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in a follow up to this study in which the same group treated nine patients with DLBCL, two with indolent lymphomas, and four with CLL [Kochenderfer et al. 2015]. Of the 15 patients treated, there were eight CRs (including four patients with DLBCL), four partial remissions, one stable disease, and two not evaluable. Subsequently, the University of Pennsylvania used a lentivirus vector expressing 41BBL instead of CD28 as the costimulatory signaling domain. Infusion of these lentivirus modified T cells following customized ‘dealers choice’ chemotherapy regimens initially showed impressive responses in two-thirds of patients with CLL [Kalos et al. 2011; Porter et al. 2011], suggesting that each CAR-expressing T cell eradicated more than 1000 CLL cells [Kalos et al. 2011]. While these results in CLL have not been sustained, most dramatic are the successes that have been observed using second-generation CD19-CAR T cells for the treatment of pediatric and adult patients with ALL [Grupp et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2015]. Groups at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, NCI, University of Pennsylvania/Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Seattle and BCM have now demonstrated response rates ranging from 70% to 90% in some patients with the poorest prognosis ALL [Brentjens et al.2013; Cruz et al. 2013; Grupp et al. 2013; Kochenderfer et al. 2012]. Despite these highly promising results, it is still difficult to determine the optimal CAR approach since each protocol varies in terms of CAR design, T-cell production, prior conditioning chemotherapy, and tumor burden [Brentjens and Curran, 2012].

A concern with CD19-CAR T cells is antigen loss as many patients have relapsing disease with CD19-negative leukemia. Therefore, attempts to develop CARs targeting other tumor targets are now a substantial focus of this field, and a clinical trial utilizing T cells modified with a CD22 CAR has just opened at the NCI for patients with relapsed ALL [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02315612] [Haso et al. 2013]. In addition, to further improve the efficacy of CAR-modified T cells, groups are incorporating two or more costimulatory domains (third-generation CARs) [Curran et al. 2012; Jena et al. 2010] or combining them with other antibody recognition domains (tandem CARs) [Grada et al. 2013].

CD20 expression occurs in more than 90% of B-cell lymphomas and is commonly retained on the surface of relapsed NHL even in (BCM) the setting of repetitive anti-CD20 antibody exposure which makes it an appealing target for immunotherapy [Budde et al. 2013]. In a proof of concept study, a group from Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center showed that first-generation CD20 CAR therapy was safe and feasible but had modest antitumor effect and disappointing persistence of infused T cells [Till et al. 2008]. A later pilot clinical trial from the same group used third-generation CD20-specific CARs with CD28 and 4-1BB costimulatory domains in three patients with indolent B-cell and mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) [Till et al. 2012]. Infusion was well tolerated in all three patients with only transient symptoms of fever and hypoxemia in one patient. Two patients remained progression free for 12 and 24 months (median time for MCL progression is 6 months), and the third patient had objective partial response but had relapsing disease 12 months after infusion.

Immunotherapy approaches for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) have thus far lagged behind ALL and lymphomas, as determining an appropriate and safe target has been difficult. While CD33 is expressed on 88% of pediatric AML blasts [Creutzig et al. 1995], its presence on maturing hematopoietic progenitor cells and Kupffer cells in the liver is concerning for significant ‘on-target, off-tumor’ toxicity that could cause myelosuppression and hepatotoxicity. However, as CD33 is not expressed on the CD34+ pluripotent hematopoietic stem cell [Dinndorf et al. 1986], it remains a promising target. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (GO), an anti-CD33 monoclonal antibody linked to the cytotoxic antibiotic calicheamicin, was approved in 2000 for relapsed AML in adults following promising phase I and phase II trials [Bross et al. 2001]. GO, however, was voluntarily withdrawn from the US market in 2010 due to increased induction mortality in one adult study although the control group had a notably low induction mortality rate [Petersdorf et al. 2013]. Other groups however continue to investigate CD33 as a target antigen for immunotherapy. Wang and colleagues recently reported the first clinical trial in which one patient with refractory AML received CD33-specific CAR T cells [Wang et al. 2015]. The patient had a transient improvement with a marked decrease in blast percentage in the bone marrow 2 weeks after infusion but developed florid disease progression by week 9 and died 13 weeks after infusion. The patient had significant pancytopenia at baseline, and thus, it is unclear what impact CD33-targeted CAR therapy had on hematopoiesis. Due to the concerns about CD33-targeted therapy, other targets have been sought. LeY is a difucosylated carbohydrate antigen whose function is unclear but known to be expressed by several malignancies including AML. A group in Australia has infused LeY CAR T cells into four patients with relapsed AML, and three patients showed clinical responses [Ritchie et al. 2013]. CAR T cells persisted for up to 10 months, but ultimately all patients developed disease progression. Although not yet tested in humans, CD123 is another promising target as it is overexpressed on AML cells more than on normal hematopoietic cells, and preclinical trials are currently underway [Mardiros et al. 2013].

Non-T cell immunotherapy approaches for hematologic malignancies

Building upon the success of monoclonal antibodies such as rituximab in hematologic malignancies, there has been growing attention to novel antibody-based therapies such as brentuximab vedotin (BV) and blinatomomab. Brentuximab vedotin is a CD30-specific monoclonal antibody–drug conjugate that has improved outcomes in patients with refractory or relapsed HL and systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) as first demonstrated by Younes and colleagues [Younes et al. 2010]. Numerous adult studies are underway using BV for HL and ALCL as well as other CD30-specific malignancies [Ansell, 2014]. In addition, the Children’s Oncology Group as two open pediatric trials incorporating BV for refractory or relapsed HL (AHOD1221, phase I/II) and newly diagnosed ALCL (ANHL12P1, phase II). Bispecific T cell engager (BiTE; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA) antibodies are bispecific monoclonal antibodies that enable binding of T cells to targeted tumor antigens, of which blinatumomab has had the most clinical success. Blinatumomab, a CD3/CD19 BiTE, was first shown to have efficacy in an adult phase I trial for indolent NHL [Bargou et al. 2008] and subsequently in B-cell ALL with relapsed or persistent disease [Topp et al. 2012]. In a multicenter phase I trial, blinatumomab had a 41% overall response rate in pediatric patients with refractory or relapsed B-cell ALL [Von Stackelberg et al. 2013] and is currently a part of a phase III Children’s Oncology Group trial (AALL1331) for patients with relapsed B-cell ALL. While there are numerous other emerging antibody therapies, a detailed discussion is outside the scope of this review.

Challenges with T-cell therapies

Overcoming toxicity

As with all therapies, toxicity is a major concern for adoptive T cell immunotherapy and can be classified as autoimmune toxicity or cytokine-associated toxicity. Autoimmune toxicity is an ‘on target, off-tumor toxicity’ that results when nonmalignant host tissue also expresses the tumor-associated antigen. The ideal antigen will have overexpression in the targeted malignancy but minimal to nonexistent expression in normal tissue as a way of minimizing adverse events. MAGEA3 is commonly expressed in many tumors, including leukemia, making it an appealing antigen for immunotherapy. However, the development of an affinity-enhanced TCR directed to a HLA-A*01-restricted MAGEA3 (EVDPIGHLY) led to significant adverse events, including severe neurologic toxicity due to cross reactivity with an epitope on MAGEA12 expressed in the brain white matter [Morgan et al. 2013] and fatal cardiac toxicity secondary to an unexpected cross reaction with an epitope on the cardiac muscle protein titin [Linette et al. 2013]. B-cell aplasia is an expected ‘on target’ toxicity associated with CD19-targeted CAR therapy as CD19 is expressed not only on malignant but also normal B cells. However, patients can be supported with immunoglobulin infusions during this time of B-cell aplasia [Grillo-Lopez et al. 2000].

Cytokine-associated toxicity, commonly referred to as cytokine release syndrome (CRS), occurs due to overactivation of the immune system and release of inflammatory cytokines. CRS manifests in a variety of ways, but fever is almost always present. Cardiac dysfunction, respiratory distress, rash, renal failure, and neurologic complications are also common. Unlike CRS with monoclonal antibodies which occurs minutes to hours after infusion, CRS associated with T-cell immunotherapy typically occurs days to weeks after infusion and appears to coincide with maximal in vivo T-cell expansion [Lee et al. 2014]. While several cytokines have been associated with CRS, IL-6 appears to play a prominent role. Tocilizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against the IL-6 receptor, has emerged as a promising therapy for severe, life-threatening CRS while corticosteroids remain as a second-line therapy due to their less potent effect on CRS as well as their immunosuppressive effects [Lee et al. 2014]. Safety switches such as the icaspase 9 system have also been incorporated into T cells in an attempt to improve their safety profile. With this approach, in the presence of toxicity mediated by the gene-modified T cells, administration of an inert dimerizing agent brings together two halves of the protease involved in initiating the apoptotic cascade resulting in rapid elimination of the gene modified T cells and reversal of the clinical symptoms [Di Stasi et al. 2011; Zhou et al. 2014].

Overcoming tumor immune evasion

Hematologic malignancies have evolved means of immune evasion, most notably the phenomena of tumor escape and immune editing. Tumor escape involves the loss of antigen presentation through downregulation of MHC and costimulatory molecules or epigenetic downregulation of tumor antigen through demethylation. Immune editing includes T cell suppression through production of cytokines such as transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), recruitment of suppressor cells, and other less defined mechanisms that favor an exhaustion T cell phenotype.

Targeting multiple tumor-associated antigens should decrease immune evasion by tumor variants with antigen loss. However, this may be further enhanced by using epigenetic modifiers to upregulate TAA expression. Goodyear and colleagues showed that azacitidine (AZA) and sodium valproate (VRA) upregulated the expression of MAGE antigens in AML and myeloma [Goodyear et al. 2010]. Furthermore, they showed that while only 1 of 21 patients had a CTL response to MAGE antigen prior to AZA/VPA therapy, a response was induced in 10 patients after therapy with AZA/VPA. Similarly, Cruz and colleagues demonstrated that decitabine, a demethylating agent, upregulates the expression of MAGEA4 in HL [Cruz et al. 2011].

TGFβ is secreted by the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment, which prevents proliferation of both CD4+ T helper type cells and cytotoxic T cells. This effect can be mitigated by rendering T cells resistant to the effects of TGFβ through the use of a mutant dominant negative TGFβ type II receptor (DNR) that is nonfunctional [Bollard et al. 2002]. DNR-transduced CTLs have proven to be resistant to the antiproliferative effects of TGFβ as well as eradication of tumor cells in vivo [Foster et al. 2008]. CTLs expressing the DNR may therefore have a selective advantage in vivo in patients with TGFβ-secreting tumors such as HL. A phase I study has shown stable disease to CR in eight patients receiving DNR-transduced LMP CTLs and persistence of these T cells for over 3 years [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00368082].

While TCR-modified T cells expand the naturally occurring T-cell repertoire to better target tumor antigens, their use is limited not only by the cost and time associated with their generation but also the fact that tumor antigens are frequently weakly immunogenic self antigens. To overcome these limitations, Liddy and colleagues have developed immune-mobilizing monoclonal TCRs against cancer (ImmTACs). ImmTACs are tumor-associated epitope-specific monoclonal TCRs with picomolar affinity combined with a humanized CD3-specific scFv which have demonstrated in vitro and in vivo ability to redirect T cells to target tumor cells even with extremely low surface epitope densities [Liddy et al. 2012]. ImmTACs also offer the advantage of being marketed as an ‘off the shelf’ therapy, making them of being more readily available than many cellular-based therapies that require timely ex vivo manipulation of lymphocytes. A phase I study [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01211262] is currently underway for IMCgp100, an ImmTAC for melanoma, but to date there are no clinical trials for ImmTACs in hematologic malignancies.

Overcoming T-cell exhaustion: improving persistence

Ideally, infused T cells would have long-term persistence in the memory compartment, so that patients may have lifelong protection against recurrence of their malignancies. Virus-specific T cells appear to have significant persistence as latent viruses continue to secrete antigens providing the stimulation necessary for T-cell proliferation and persistence. Tumors, however, tend to downregulate antigens. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that IL-15 and IL-21 may improve -cell persistence as they lead to a memory phenotype [Hoyos et al. 2010; Singh et al. 2011]. Another possible strategy to improve persistence is to generate T cells that are both tumor specific and virus specific [Cruz et al. 2013; Micklethwaite et al. 2010; Rossig et al. 2002; Terakura et al. 2012]. Other groups have focused on the importance of the T cells utilized for gene modification, such as central memory derived [Wang et al. 2012] or naïve derived T cells [Distler et al. 2011; Hinrichs et al. 2011]. In addition, improvements within the CAR construct have also allowed improvements in CAR T cell persistence and efficacy [Jonnalagadda et al. 2014]. Furthermore, building on the success in melanoma and solid tumors, there is growing interest in combing the use of checkpoint inhibitors targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), program cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) to foster T cell persistence in vivo [Pardoll, 2012; Topalian et al. 2015]. Despite significant advances in adoptive T cell immunotherapy, the ability to generate modified T cells quickly and cost effectively remains a limiting factor. Prolonged culture time not only delays availability to patients but also causes cell anergy. The use of novel bioreactors that allow improved gas exchange and surface area may decrease production time [Vera et al. 2010].

Conclusion

Adoptive T-cell immunotherapy is revolutionizing the treatment of hematologic malignancies and offers hope to patients with relapsing disease after HSCT and have few other therapeutic options. While there have been numerous advancements thus far, significant limitations remain. Future directions of research will include optimizing the generation of modified T cells to enhance not only efficacy but also the cost and time of manufacturing so that they may be readily available. Current and future clinical trials will hopefully build upon current successes with the potential to render adoptive T-cell immunotherapies the standard of care for hematologic malignancies for patients with refractory or relapsed disease.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Lauren McLaughlin, Children’s National Health System and The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA.

C. Russell Cruz, Children’s National Health System and The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA.

Catherine M. Bollard, Children’s National Health System and The George Washington University, 111 Michigan Ave, Washington, DC 20010, USA.

References

- Ansell S. (2014) Brentuximab vedotin. Blood 124: 3197–3200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargou R., Leo E., Zugmaier G., Klinger M., Goebeler M., Knop S., et al. (2008) Tumor regression in cancer patients by very low doses of T cell-engaging antibody. Science 321: 974–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendle G., Linnemann C., Hooijkaas A., Bies L., de Witte M., Jorritsma A., et al. (2010) Lethal graft-versus-host disease in mouse models of T cell receptor gene therapy. Nat Med 16: 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley M., Riddell S. (2011) Exploiting T cells specific for human minor histocompatibility antigens for therapy of leukemia. Immunol Cell Biol 89: 396–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollard C., Gottschalk S., Torrando V., Diouf O., Ku S., Hazrat Y., et al. (2014) Sustained complete responses in patients with lymphoma receiving autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes targeting Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane proteins. J Clin Oncol 32: 798–808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollard C., Kuehnle I., Leen A., Rooney C., Heslop H. (2004) Adoptive immunotherapy for posttransplantation viral infections. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 10: 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollard C., Rossig C., Calonge M., Huls M., Wagner H., Massague J., et al. (2002) Adapting a transforming growth factor beta-related tumor protection strategy to enhance antitumor immunity. Blood 99: 3179–3187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornhauser M., Thiede C., Babatz J., Schetelig J., Illmer T., Kiani A., et al. (2006) Infusion of bcr.abl peptide-reactive donor T cells to achieve molecular remission of chronic myeloid leukemia after CD34+ selected allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Leukemia 11: 2055–2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornhauser M., Thiede C., Platzbecker U., Kiana A., Oelschlaegel U., Babatz J., et al. (2011) Prophylactic transfer of BCR-ABL-, PR1-, and WT1-reactive donor T-cells after T cell-depleted allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 117: 7174–7184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brentjens R., Curran K. (2012) Novel cellular therapies for leukemia: CAR-modified T cells targeted to the CD19 antigen. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2012: 143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brentjens R., Davila M., Riviere I., Park J., Wang X., Cowell L., et al. (2013) CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med 5: 177ra38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brieger J., Weidmann E., Fenchel K., Mitrou P., Hoelzer D., Bergmann L. (1994) The expression of the Wilms’ tumor gene in acute myelocytic leukemias as a possible marker for leukemic blast cells. Leukemia 8: 2138–2143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bross P., Beitz J., Chen G., Chen X., Duffy E., Kieffer L., et al. (2001) Approval summary: gemtuzumab ozogamicin in relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 7: 1490–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde L., Berger C., Lin Y., Wang J., Lin X., Frayo S., et al. (2013) Combining a CD20 chimeric antigen receptor and an inducible caspase 9 suicide switch to improve the efficacy and safety of T cell adoptive immunotherapy for lymphoma. PLoS One 8: e82742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron B., Gerry A., Duke J., Harper J., Kannan V., Bianchi F., et al. (2013) Identification of a Titin-derived HLA-A1-presented peptide as a cross-reactive target for engineered MAGE A3-directed T cells. Sci Transl Med 5: 197ra103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapuis A., Ragnarsson G., Nguyen H., Chaney C., Pufnock J., Schmitt T., et al. (2013) Transferred WT1-reactive CD8+ T cells can mediate antileukemic activity and persist in post-transplant patients. Sci Transl Med 5: 174ra27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzig U., Harbott J., Sperling C., Ritter J., Zimmermann M., Loffler H., et al. (1995) Clinical significance of surface antigen expression in children with acute myeloid leukemia results of study AML-BFM-87. Blood 86: 3097–3108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz C., Gerdemann U., Leen A., Shaffer J., Ku S., Tzou B., et al. (2011) Improving T-cell therapy for relapsed EBV-negative Hodgkin lymphoma by targeting upregulated MAGE-A4. Clin Cancer Res 17: 7058–7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz C., Micklethwaite K., Savoldo B., Ramos C., Lam S., Ku S., et al. (2013) Infusion of donor-derived CD19-redirected virus-specific T cells for B-cell malignancies relapsed after allogeneic stem cell transplant: a phase 1 study. Blood 122: 2965–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran K, Pegram H., Brentjens R. (2012) Chimeric antigen receptors for T cell immunotherapy: current understanding and future directions. J Gene Med 14: 405–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deol A., Lum L. (2010) Role of donor lymphocyte infusions in relapsed hematological malignancies after stem cell transplantation revisited. Cancer Treat Rev 36: 528–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinndorf P., Andrews R., Benjamin D., Ridgway D., Bernstein I. (1986) Expression of normal myeloid-associated antigens by acute leukemia cells. Blood 67: 1048–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Stasi A., Tey S., Dotti G., Fujita Y., Kennedy-Nasser A., Martinez C., et al. (2011) Inducible apoptosis as a safety switch for adoptive cell therapy. N Engl J Med 365: 1673–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distler E., Bloetz A., Albrecht J., Asdufan S., Hohberger A., Frey M., et al. (2011) Alloreactive and leukemia-reactive T-cells are preferentially derived from naive precursors in healthy donors: implications for immunotherapy with memory T cells. Haematologica 96: 1024–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburg J., Wafelman A., Joosten P., Smit W., Van Bergen C., Bongaerts R., et al. (1999) Complete remission of accelerated phase chronic myeloid leukemia by treatment with leukemia-reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Blood 94: 1201–1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney H., Lawson A., Bebbington C., Weir A. (1998) Chimeric receptors providing both primary and costimulatory signaling in T cells from a single gene product. J Immunol 161: 2791–2797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster A., Dotti G., Lu A., Khalil M., Brenner M., Heslop H., et al. (2008) Antitumor activity of EBV-specific T lymphocytes transduced with a dominant negative TGF-beta receptor. J Immunother 31: 500–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdemann U., Katari U., Christin A., Cruz C., Tripic T., Rousseau A., et al. (2011) Cytotoxic T lymphocytes simultaneously targeting multiple tumor-associated antigens to treat EBV negative lymphoma. Mol Ther 19: 2258–2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear O., Agathanggelou A., Novitzky-Basso I., Siddique S., Mcskeane T., Ryan G., et al. (2010) Induction of a CD8+ T-cell response to the MAGE cancer testis antigen by combined treatment with azacitidine and sodium valproate in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplasia. Blood 116: 1908–1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grada Z., Hegde M., Byrd T., Shaffer D., Ghazi A., Brawley V., et al. (2013) TanCAR: a novel bispecific chimeric antigen receptor for cancer immunotherapy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2: e105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo-Lopez A., White C., Dallaire B., Varns C., Shen C., Wei A., et al. (2000) Rituximab: the first monoclonal antibody approved for the treatment of lymphoma. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 1: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross G., Waks T., Eshhar Z. (1989) Expression of immunoglobulin-T-cell receptor chimeric molecules as functional receptors with antibody-type specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 10024–10028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grupp S., Kalos M., Barrett D., Aplenc R., Porter D., Rheingold S., et al. (2013) Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for acute lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med 368: 1509–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque T., Mcaulay K., Kelly D., Crawford D. (2010) Allogeneic T-cell therapy for Epstein-Barr virus-positive posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease: long-term follow-up. Transplantation 90: 93–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haso W., Lee D., Shah N., Stetler-Stevenson M., Yuan C., Pastan I., et al. (2013) Anti-CD22-chimeric antigen receptors targeting B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 121: 1165–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop H., Slobod K., Pule M., Hale G., Rousseau A., Smith C., et al. (2010) Long-term outcome of EBV-specific T cell infusions to prevent or treat EBV-related lymphoproliferative disease in transplant recipients. Blood 115: 925–935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs C., Borman Z., Gattinoni L., Yu Z., Burns W., Huang J., et al. (2011) Human effector CD8+ T-cells derived from naive rather than memory subsets possess superior traits for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood 117: 808–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs C., Spolski R., Paulos C., Gattinoni L., Kerstann K., Palmer D., et al. (2008) IL-2 and IL-21 confer opposing differentiation programs to CD8+ T cells for adoptive immunotherapy. Blood 111: 5326–5333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos V., Savoldo B., Quintarelli C., Mahendravada A., Zhang M., Hoyos V., et al. (2010) Engineering CD19-specific T lymphocytes with interleukin-15 and a suicide gene to enhance their anti-lymphoma/leukemia effects and safety. Leukemia 24: 1160–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janeway C., Travers P., Walport M., Schlomchik J. (2005) Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease. New York and London: Garland Science Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Jena B., Dotti G., Cooper L. (2010) Redirecting T-cell specificity by introducing a tumor-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Blood 116: 1035–1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M., Popplewell L., Cooper L., Digiusto D., Kalos M., Osteberg J., et al. (2010) Antitransgene rejection responses contribute to attenuated persistence of adoptively transferred CD20/CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor redirected T-cells in humans. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16: 1245–1256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L., Morgan R., Dudley M., Cassard L., Yang J., Hughes M., et al. (2009) Gene therapy with human and mouse T-cell receptors mediates cancer regression and targets normal tissues expressing cognate antigen. Blood 114: 535–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonnalagadda M., Mardiros A., Urak R., Wang X., Hoffman L., Bernanke A., et al. (2014) Chimeric antigen receptors with mutated IgG4 Fc spacer avoid fc receptor binding and improve T cell persistence and antitumor efficacy. Mol Ther 23: 757–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalos M., Levine B., Porter D., Katz S., Grupp S., Bagg A., et al. (2011) T cells with chimeric antigen receptors have potent antitumor effects and can establish memory in patients with advanced leukemia. Sci Transl Med 3: 95ra73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer J., Dudley M., Feldman S., Wilson W., Spaner D., Maric I., et al. (2012) B-cell depletion and remissions of malignancy along with cytokine-associated toxicity in a clinical trial of anti-CD19 chimeric-antigen-receptor-transduced T cells. Blood 119: 2709–2720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer J., Dudley M., Kassim S., Somerville R., Carpenter R., Stetler-Stevenson M., et al. (2015) Chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and indolent B-cell malignancies can be effectively treated with autologous T cells expressing an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor. J Clin Oncol 33: 540–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer J., Wilson W., Janik J., Dudley M., Stetler-Stevenson M., Feldman S., et al. (2010) Eradication of B-lineage cells and regression of lymphoma in a patient treated with autologous T cells genetically engineered to recognize CD19. Blood 116: 4099–4102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H., Mittermuller J., Clemm C., Holler E., Ledderose G., Brehm G., et al. (1990) Donor leukocyte transfusions for treatment of recurrent chronic myelogenous leukemia in marrow transplant patients. Blood 76: 2462–2465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowolik C., Topp M., Gonzalez S., Pfeiffer T., Olivares S., Gonzalez N., et al. (2006) CD28 costimulation provided through a CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor enhances in vivo persistence and antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred T cells. Cancer Res 66: 10995–11004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D., Gardner R., Porter D., Louise C., Ahmed N., Jensen M., et al. (2014) Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of cytokine release syndrome. Blood 124: 188–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D., Kochenderfer J., Stetler-Stevenson M., Cui Y., Delbrook C., Feldman S., et al. (2015) T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 385: 517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Bleakley M., Yee C. (2005) IL-21 influences the frequency, phenotype, and affinity of the antigen-specific CD8 T cell response. J Immunol 175: 2261–2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddy N., Bossi G., Adams K., Lissina A., Mahon T., Hassan N., et al. (2012) Monoclonal TCR-redirected tumor cell killing. Nat Med 18: 980–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linette G., Stadtmauer E., Maus M., Rapoport A., Levine B., Emery L., et al. (2013) Cardiovascular toxicity and titin cross-reactivity of affinity-enhanced T cells in myeloma and melanoma. Blood 122: 863–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher J., Brentjens R., Gunset G., Riviere I., Sadelain M. (2002) Human T-lymphocytes cytotoxicity and proliferation directed by a single chimeric TCRzeta/CD28 receptor. Nat Biotechnol 20: 70–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardiros A., Dos Santos C., McDonald T., Brown C., Wang X., Buddge L., et al. (2013) T cells expressing CD123-specific chimeric antigen receptors exhibit specific cytolytic effector functions and antitumor effects against human acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 122: 3138–3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menssen H., Renkl H., Rodeck U., Maurer J., Notter M., Schwartz S., et al. (1995) Presence of Wilms’ tumor gene (WT1) transcripts and the WT1 nuclear protein in the majority of human acute leukemias. Leukemia 9: 1060–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micklethwaite K., Savoldo B., Hanley P., Leen A., Demmler-Harrison G., Cooper L., et al. (2010) Derivation of human T lymphocytes from cord blood and peripheral blood with antiviral and antileukemic specificity from a single culture as protection against infection and relapse after stem cell transplantation. Blood 115: 2695–2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R., Dudley M., Wunderlich J., Hughes M., Yang J., Sherry R., et al. (2006) Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science 314: 126–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan R., Chinnasamy N., Abate-Daga D., Gros A., Robbins P., Zheng Z., et al. (2013) Cancer regression and neurological toxicity following anti-MAGE-A3 TCR gene therapy. J Immunother 36: 133–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikiforow S., Alyea E. (2014) Maximizing GVL in allogeneic transplantation: role of donor lymphocyte infusions. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 1: 570–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly R., Lacerda J., Lucas K., Rosenfield N., Small T., Papadopoulos E. (1996) Adoptive cell therapy with donor lymphocytes for EBV-associated lymphomas developing after allogeneic marrow transplants. Important Adv Oncol 149–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardoll D. (2012) The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 12: 252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersdorf S., Kopecky K., Slovak M., Willman C., Nevill T., Brandwein J., et al. (2013) A phase 3 study of gemtuzumab ozogamicin during induction and postconsolidation therapy in younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 121: 4854–4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter D., Levine B., Kalos M., Bagg A., June C. (2011) Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in chronic lymphoid leukemia. N Engl J Med 365: 725–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani K., Yong A., Savani B., Mielke S., Keyvanfar K., Gostick E., et al. (2007) Graft-versus-leukemia effects associated with detectable Wilms tumor-1 specific T lymphocytes after allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 110: 1924–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie D., Neeson P., Khot A., Peinert S., Tai T., Tainton K., et al. (2013) Persistence and efficacy of second generation CAR T cell against the LeY antigen in acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Ther 21: 2122–2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S. (2010) Of mice, not men: no evidence for graft-versus-host disease in humans receiving T-cell receptor-transduced autologous T-cells. Mol Ther 18: 1744–1745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg S. (2011) Cell transfer immunotherapy for metastatic solid cancer—what clinicians need to know. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8: 577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossig C., Bollard C., Nuchtern J., Rooney C., Brenner M. (2002) Epstein-Barr virus-specific human T lymphocytes expressing antitumor chimeric T-cell receptors: potential for improved immunotherapy. Blood 99: 2009–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoldo B., Ramos C., Liu E., Mims M., Keating M., Carrum G., et al. (2011) CD28 costimulation improves expansion and persistence of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in lymphoma patients. J Clin Invest 121: 1822–1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher T. (2002) T-cell-receptor gene therapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2: 512–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H., Figliola M., Dawson M., Huls H., Olivares S., Switzer K., et al. (2011) Reprogramming CD19-specific T cells with IL-21 signaling can improve adoptive immunotherapy of B-lineage malignancies. Cancer Res 71: 3516–3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terakura S., Yamamoto T., Gardner R., Turtle C., Jensen M., Riddell S. (2012) Generation of CD19-chimeric antigen receptor modified CD8+ T cells derived from virus-specific central memory T cells. Blood 119: 72–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till B., Jensen M., Wang J., Chen E., Wood B., Greisman H., et al. (2008) Adoptive immunotherapy for indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma using genetically modified autologous CD20-specific T cells. Blood 112: 2261–2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Till B., Jensen M., Wang J., Qian X., Gopal A., Maloney D., et al. (2012) CD20-specific adoptive immunotherapy for lymphoma using a chimeric antigen receptor with both CD28 and 4-1BB domains: pilot clinical trial results. Blood 119: 3940–3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topalian S., Drake C., Pardoll D. (2015) Immune checkpoint blockage: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell 27: 450–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp M., Gokbuget N., Zugmaier G., Degenhard E., Goebeler M., Klinger M., et al. (2012) Long-term follow-up of hematologic relapse-free survival in a phase 2 study of blinatumomab in patients with MRD in B-lineage ALL. Blood 120: 5185–5187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vera J., Brenner L., Gerdemann U., Ngo M., Sili U., Liu H., et al. (2010) Accelerated production of antigen-specific T cells for preclinical and clinical applications using gas-permeable rapid expansion cultureware (G-Rex). J Immunother 33: 305–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Stackelberg A., Zugmaier G., Handgretinger R., Locatelli F., Rizzari C., Trippett T., et al. (2013) A phase 1/2 study of blinatumomab in pediatric patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 122: 70. [Google Scholar]

- Vickers M., Wilkie G., Robinson N., Rivera N., Haque T., Crawford D., et al. (2014) Establishment and operation of a Good Manufacturing Practice-compliant allogeneic Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-specific cytotoxic cell bank for the treatment of EBV-associated lymphoproliferative disease. Br J Haematol 167: 402–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Naranjo A., Brown C., Bautista C., Wong C., Chang W., et al. (2012) Phenotypic and functional attributes of lentivirus-modified CD19-specific human CD8+ central memory T cells manufactured at clinical scale. J Immunother 35: 689–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Wang Y., Lv H., Han Q., Fan H., Guo B., et al. (2015) Treatment of CD33-directed chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in one patient with relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Mol Ther 23: 184–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren E., Fujii N., Akatsuka Y., Chaney C., Mito J., Loeb K., et al. (2010) Therapy of relapsed leukemia after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with T cells specific for minor histocompatibility antigens. Blood 115: 3869–3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber G., Caruana I., Rouce R., Barrett A., Gerdemann U., Leen A., et al. (2013a) Generation of tumor antigen-specific T cell lines from pediatric patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia–implications for immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 19: 5079–5091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber G., Gerdemann U., Caruana I., Savoldo B., Hensel N., Rabin K., et al. (2013b) Generation of multi-leukemia antigen-specific T cells to enhance the graft-versus-leukemia effect after allogeneic stem cell transplant. Leukemia 27: 1538–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younes A., Bartlett N., Leonard J., Kennedy D., Lynch C., Sievers E., et al. (2010) Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) for relapsed CD30-positive lymphomas. N Engl J Med 363: 1812–1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Di Stasi A., Tey S., Krance R., Martinez C., Leung K., et al. (2014) Long-term outcome after haploidentical stem cell transplant and infusion of T cells expressing the inducible caspase 9 safety transgene. Blood 123: 3895–3905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]