Abstract

Recombination has an impact on genome evolution by maintaining chromosomal integrity, affecting the efficacy of selection, and increasing genetic variability in populations. Recombination rates are a key determinant of the coevolutionary dynamics between hosts and their pathogens. Historic recombination events created devastating new pathogens, but the impact of ongoing recombination in sexual pathogens is poorly understood. Many fungal pathogens of plants undergo regular sexual cycles, and sex is considered to be a major factor contributing to virulence. We generated a recombination map at kilobase-scale resolution for the haploid plant pathogenic fungus Zymoseptoria tritici. To account for intraspecific variation in recombination rates, we constructed genetic maps from two independent crosses. We localized a total of 10,287 crossover events in 441 progeny and found that recombination rates were highly heterogeneous within and among chromosomes. Recombination rates on large chromosomes were inversely correlated with chromosome length. Short accessory chromosomes often lacked evidence for crossovers between parental chromosomes. Recombination was concentrated in narrow hotspots that were preferentially located close to telomeres. Hotspots were only partially conserved between the two crosses, suggesting that hotspots are short-lived and may vary according to genomic background. Genes located in hotspot regions were enriched in genes encoding secreted proteins. Population resequencing showed that chromosomal regions with high recombination rates were strongly correlated with regions of low linkage disequilibrium. Hence, genes in pathogen recombination hotspots are likely to evolve faster in natural populations and may represent a greater threat to the host.

Keywords: recombination hotspots, pathogen evolution, restriction site–associated DNA sequencing, population genomics, linkage disequilibrium

RECOMBINATION is a fundamental process that shapes the evolution of genomes. Crossover between homologous chromosomes ensures proper segregation during meiosis (Mather 1938; Baker et al. 1976; Hassold and Hunt 2001), and the integrity of chromosomal structure over evolutionary time is affected by the frequency of recombination. Sex chromosomes in plants and animals and mating-type regions of fungi experience degeneration, including significant gene loss and sequence rearrangements, after cessation of recombination between homologs (Bull 1983; Charlesworth and Charlesworth 2000; Brown et al. 2005; Menkis et al. 2008; Wilson and Makova 2009). Recombination breaks up linkage between alleles of different loci and creates novel haplotypes and phenotypic diversity. Through this process, recombination promotes adaptation because selection acting across multiple loci becomes more efficient as the linkage between loci decreases (Hill and Robertson 1966; Otto and Barton 1997; Otto and Lenormand 2002).

Recombination also plays a major role in the coevolutionary dynamics of hosts and their pathogens. A major driver to maintain sexual reproduction in hosts was proposed to be the constant selection to evade disease caused by pathogens (Hamilton 1980; Lively 2010; Morran et al. 2011). However, pathogens are also under strong selection to overcome newly evolved host resistance mechanisms. Recombination in pathogens plays a central role in disease outbreaks caused by viruses, bacteria, and eukaryotic microorganisms. Epidemic influenza is driven by annual recurring outbreaks of recombined viral strains (Nelson and Holmes 2007). The highly virulent lineage of Salmonella enterica, which causes typhoid fever (Didelot et al. 2007; Holt et al. 2008), emerged from recombination with the related paratyphi A lineage. Recombination between ancestral lineages of Toxoplasma created hypervirulent clones of the protozoan human pathogen T. gondii (Grigg et al. 2001), and ongoing outcrossing and clonal expansion contribute to extant Toxoplasma outbreaks (Wendte et al. 2010). Some of the most threatening fungal pathogen lineages were generated by historic recombination events between lineages. Reshuffling between different genotypes may have contributed to the emergence of the hypervirulent human pathogen Cryptococcus gattii in the Pacific Northwest (Fraser et al. 2005; Byrnes et al. 2011), where same-sex mating was suggested to have enabled the creation of a recombinant hypervirulent genotype (Fraser et al. 2005). The chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis is causing a global epidemic in a wide range of amphibians (Fisher et al. 2009). The pathogen is comprised of a complex set of lineages. However, the outbreak is overwhelmingly caused by a single hypervirulent lineage that was created by hybridization and subsequent recombination of two distinct allopatric Batrachochytrium lineages (Rosenblum et al. 2008; Farrer et al. 2011).

In contrast to the evidence that historic recombination events led to the creation of novel fungal pathogens, the impact of frequent recombination on genome evolution in extant sexual pathogens is poorly understood (Awadalla 2003). Because the extent of recombination correlates with the evolutionary potential of a population, the occurrence of sexual reproduction was suggested to be a predictor of a pathogen’s capacity to overcome host resistance mechanisms (McDonald and Linde 2002; Stukenbrock and McDonald 2008). Pathogenic fungi of plants span a broad range of lifestyles from asexual to mainly sexual or mixed reproduction and can include multiple sexual cycles per year (McDonald and Linde 2002). Hence, these fungi are ideal models to study the impact of recombination on pathogen evolution. Loci contributing to virulence in pathogens undergo rapid allele frequency changes in response to changes in host populations (Barrett et al. 2009; Thrall et al. 2012), and fungal pathogenicity is often found to be encoded by a large number of virulence loci distributed throughout the genome (Karasov et al. 2014). Recombination enables the emergence of pathogen strains that carry novel combinations of virulence alleles that may increase virulence in specific hosts.

A key determinant of the speed of adaptation of a pathogenic organism may be intragenomic variation in recombination rates that locally increase the efficacy of selection. Strong signatures of selection at linked sites were found in nematodes and humans, but evidence for such signatures was weak or absent in plants and the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Cutter and Payseur 2013). Nevertheless, recombination rates in a genome can vary dramatically. In some model organisms, most crossovers occurring during meiosis are focused in narrow chromosomal regions termed recombination hotspots (Kong et al. 2002; Jensen-Seaman et al. 2004; Myers et al. 2005; Arnheim et al. 2007). Hotspots can have a profound effect on the recombination landscape of a genome. In the human genome, hotspots with a mean width of 2.3 kb accounted for 70–80% of all recombination events (1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al. 2010). Hotspots were preferentially located near telomeres in humans, plants, and the yeast S. cerevisiae (Drouaud 2005; Myers et al. 2005; Tsai et al. 2010). Recombination hotspots are thought to be inherently unstable because of a “hotspot drive” mechanism that continuously replaces alleles favoring higher recombination rates (Webster and Hurst 2012). Genomic signatures of elevated recombination rates comprised increased GC content, likely resulting from the preferential incorporation of C and G during the mismatch repair process initiated by the pairing of homologous sequences (Duret and Galtier 2009).

We aimed to identify recombination rate heterogeneity and its impact on the genome of a pathogenic fungus. Zymoseptoria tritici is a globally occurring pathogen of wheat that causes severe yield losses (O’Driscoll et al. 2014). The fungus undergoes sexual reproduction at least once per wheat-growing season (Kema et al. 1996; Cowger et al. 2002, 2008). Recombination between isolates was suggested to facilitate the evolution of virulence on previously resistant wheat varieties (Zhan et al. 2007). The genetic basis of virulence was shown to have a strong quantitative component (Zhan et al. 2005). Z. tritici populations undergo rapid allele frequency shifts in response to the application of fungicides (Torriani et al. 2009). The genome is haploid and was assembled into 21 complete chromosomes including telomeres (Goodwin et al. 2011). Eight chromosomes were termed accessory because they were not present in all isolates. Meiosis frequently contributed to the loss, fusion, or rearrangement of these accessory chromosomes (Wittenberg et al. 2009; Croll et al. 2013).

We generated a high-density SNP-based recombination map of two large progeny populations of Z. tritici. First, we used the map to precisely locate recombination hotspots, identified correlations with genome characteristics, and tested whether hotspots were conserved between crosses. We then compared recombination rates between the small accessory and large core chromosomes in Z. tritici to determine whether recombination differently affects the two chromosomal classes. Next, we investigated whether hotspots were enriched in specific sequence motifs and whether hotspots were more likely to contain specific functional categories of genes. Finally, we tested whether recombination hotspots identified in the mapping populations predicted local breakdowns in linkage disequilibrium in a resequenced natural pathogen population.

Materials and Methods

Establishment of controlled sexual crosses

We performed two sexual crosses between four different Z. tritici isolates collected from two wheat fields separated by ∼10 km in Switzerland. All isolates were previously characterized phenotypically and genetically (Zhan et al. 2005; Croll et al. 2013). The two crosses were performed between the isolates ST99CH1A5 and ST99CH1E4 (abbreviated 1A5 and 1E4) and ST99CH3D1 and ST99CH3D7 (abbreviated 3D1 and 3D7), respectively. The parental isolates were used to co-infect wheat leaves according to a protocol established for Z. tritici (Kema et al. 1996). Shooting ascospores were collected, grown in vitro, and genotyped by microsatellite markers to confirm that progeny genotypes were recombinants of the parental genotypes.

SNP genotyping based on restriction site–associated DNA sequencing (RAD-seq)

We chose a high-throughput genotyping method originally developed for animal and plant population genomics (Baird et al. 2008). We adapted the RAD-seq protocol (Etter et al. 2011) for Z. tritici by using PstI for the digestion of 1.3 µg of genomic DNA per progeny. After DNA digestion, shearing, and adapter ligation, we performed 100-bp Illumina paired-end sequencing on pooled samples. Progeny were identified by combining 24 distinct inline barcodes located in the P1 adapter and 6 index sequences in the P2 adapter.

Illumina data analysis and reference alignment

Raw Illumina reads were quality trimmed with Trimmomatic v. 0.30 (Bolger et al. 2014) and split into unique sets for each progeny with the FASTX Toolkit v. 0.0.13 (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/). We used the short-read aligner Bowtie v. 2.1.0 (Langmead and Salzberg 2012) to align the read set of each progeny to the reference genome IPO323 [assembly version MG2, September 2008 (Goodwin et al. 2011)]. We used the default settings for a sensitive end-to-end alignment (-D 15; -R 2; -L 22; -i S,1,1.15). The whole genomes of all four parental isolates were previously resequenced (Torriani et al. 2011) and are available under the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) SRA accession numbers SRS383146 (3D1), SRS383147 (3D7), SRS383142 (1A5), and SRS383143 (1E4). We used identical trimming and assembly parameters to align the whole-genome sequencing data set to the reference genome IPO323. All Illumina sequence data generated for progeny resequencing are available under NCBI BioProject accession numbers PRJNA256988 (cross 3D1 × 3D7) and PRJNA256991 (cross 1A5 × 1E4).

Variant calling and filtration

SNPs were identified based on the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) v. 2.6-4-g3e5ff60 (DePristo et al. 2011). SNPs were called separately for each cross with the GATK UnifiedGenotyper. Each UnifiedGenotyper run combined all progeny and their two respective parents. For UnifiedGenotyper runs, we set the sample-level ploidy to 1 (haploid) and permitted a maximum of two alternative alleles compared to the reference genome. The genotype likelihood model was set to the SNP general ploidy model.

We used the GATK filtering and variant selection tools to remove spurious SNP calls from the data set. We set the following requirements for a SNP to pass the filtering: overall quality score (QUAL ≥ 100), mapping quality (MQ ≥ 30), haplotype score (HaplotypeScore ≤ 13), quality by depth (QD ≥ 5), read position rank-sum test (ReadPosRankSumTest ≥ −8), and Fisher’s exact test for strand bias (FS ≤ 40). After a joint SNP locus filtering, we filtered genotypes for each parental isolate and progeny at each retained locus. We required that each included isolate have a minimum mean genotyping depth of five high-quality reads. We retained individual genotypes if the Phred-scaled genotype quality (GQ) assigned by the GATK UnifiedGenotyper was at least 30.

Genetic map construction and quality assessment

We constructed a genotype matrix containing all progeny that were genotyped at a minimum of 90% of all SNPs. Subsequently, we removed all SNP markers that were genotyped in fewer than 90% of the progeny. We assessed the clonal fraction among the progeny in the offspring populations using the r/qtl package in R (Arends et al. 2010). If two progeny were identical at 90% or more of the SNPs, we randomly excluded one of the two likely clones. We inspected the quality of the progeny genotype set for problematic double crossovers at very closely spaced markers. For this, we calculated error LOD scores (Lincoln and Lander 1992) as implemented in the r/qtl package. The error LOD score compares likelihoods for a correct genotype vs. an erroneous genotype based on pairwise linkage. We excluded genotypes exceeding an error LOD score of 2 from the data set. We filtered the progeny genotype data for random genotyping errors. We required that any double-crossover event in a progeny must be spanned by at least three consecutive SNPs. Furthermore, any double-crossover event had to span at least 500 bp. These filtering steps ruled out the erroneous production of double-crossover events by a single stack (i.e., restriction site) of RAD sequencing reads. In addition, we visually inspected the genotype grid for potential erroneous read mapping or translocation events indicated by switched genotypes in all progeny of a cross. We identified three potential erroneous locations in the cross of 3D1 × 3D7, with each spanning a maximum physical distance of 650 bp. In the 1A5 × 1E4 cross, we found three potential erroneous locations with SNP loci spanning a maximum of 50 bp for each region. SNP loci within an erroneous mapping location were excluded from further analysis.

In summary, we retained 23,563 SNPs in 227 progeny of the cross between parental isolates 3D1 and 3D7. We analyzed 214 progeny at 23,284 SNP markers for the cross between parental isolates 1A5 and 1E4. The SNP marker density was 0.6 SNP/kb. The genotyping rate averaged 96.5% (chromosomal averages 93.7–97.3%) for the cross 3D1 × 3D7 and 95.0% (chromosomal averages 90.9–98.3%) for the cross 1A5 × 1E4 (Table 1). SNP markers covered the entire length of all core chromosomes with the exception of telomeric regions. Marker densities were similarly distributed along chromosomes in both crosses.

Table 1. Summary of restriction-associated DNA sequencing (RAD-seq) SNP markers used for the construction of genetic maps.

| Cross 3D1 × 3D7 (227 progeny) | Cross 1A5 × 1E4 (214 progeny) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | No. of SNPs | Genotyping rate (%) | No. of SNPs | Genotyping rate (%) |

| 1 | 4697 | 96.16 | 4629 | 96.15 |

| 2 | 2486 | 97.26 | 2290 | 96.28 |

| 3 | 2299 | 97.31 | 2233 | 96.02 |

| 4 | 1614 | 96.87 | 1447 | 96.08 |

| 5 | 1634 | 95.62 | 1778 | 96.16 |

| 6 | 1398 | 97.03 | 1349 | 96.28 |

| 7 | 1379 | 97.27 | 1401 | 96.16 |

| 8 | 1576 | 96.54 | 1537 | 96.10 |

| 9 | 1448 | 97.08 | 1309 | 95.62 |

| 10 | 1013 | 97.09 | 1115 | 95.95 |

| 11 | 920 | 97.26 | 982 | 96.08 |

| 12 | 923 | 96.90 | 775 | 95.50 |

| 13 | 806 | 96.95 | 721 | 95.94 |

| 14 | — | — | 118 | 90.97 |

| 15 | — | — | 461 | 93.93 |

| 16 | 193 | 95.49 | 109 | 92.37 |

| 17 | 395 | 93.72 | — | — |

| 18 | — | — | 110 | 90.93 |

| 19 | 461 | 97.06 | 411 | 94.13 |

| 20 | 321 | 94.25 | 271 | 94.63 |

| 21 | — | — | 238 | 93.58 |

The average genotyping rate of the SNP markers is shown as an average per chromosome and cross. Chromosomes 1–13 are core chromosomes found in all strains of the species; chromosomes 14–21 are accessory.

We calculated recombination fractions among all pairs of retained markers using the r/qtl package. We set the maximum of iterations to 10,000 and the tolerance for recombination fraction estimates to 0.0001. Using identical settings, we calculated genetic distances for marker pairs on each chromosome.

Genetic map reconstruction of chromosome 13

Based on pairwise recombination fractions, we identified one problematic region located on chromosome 13 (Supporting Information, Figure S1). In both crosses, the pattern of recombination fractions suggested that the parental isolates differed from the reference genome used for read mapping. To generate the correct marker order on chromosome 13, we produced the genetic map using r/rqtl. We used 10,000 iterations and a tolerance of 0.0001 for centimorgan estimates between markers. The recalculated marker order showed that the problematic region contains a large, weakly recombining region (Figure S1). Because the marker order in weakly recombining regions is difficult to confirm with a high degree of confidence, we excluded chromosome 13 from analyses requiring exact physical locations of markers.

Correlations of recombination rates and genome characteristics

We downloaded the reference genome IPO323 [assembly version MG2, September 2008 (Goodwin et al. 2011)] from http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Mycgr3/Mycgr3.home.html (accessed March 2014). Gene annotations of Z. tritici related to the RefSeq Assembly ID GCF_000219625.1 were accessed in January 2014. SignalP annotations for gene models of IPO323 were retrieved from http://genome.jgi-psf.org/Mycgr3/Mycgr3.home.html (accessed March 2014). Enrichment for SignalP secretion signals (probability > 0.9) was tested using a hypergeometric test in R.

Motif search in recombination hotspots

We searched recombination hotspots for enriched sequence motifs with HOMER v 4.3 (Heinz et al. 2010). For this, we divided the chromosome sequences into nonoverlapping 10-kb segments. For each cross, we identified segments showing at least 10 crossover events. We used the HOMER findMotifsGenome module to identify enriched oligonucleotides in the hotspot segments compared to the genomic background divided into equally long segments of 10 kb. We used GC-content autonormalization to correct for bias in sequence composition. The motif length search was restricted to 8, 10, and 12 bp. The top-scoring motif then was used to detect chromosomal regions containing the motif using the annotatePeaks tool included in HOMER.

Population genomic analyses of linkage disequilibrium

We analyzed Illumina whole-genome sequence data from all 4 parental isolates and 21 additional isolates (data available under NCBI BioProject accession number PRJNA178194) from the same Swiss population (Torriani et al. 2011). We used identical reference genome alignment and SNP quality filtering procedures as described earlier for the RAD-seq analyses. To correlate recombination rates and linkage disequilibria, we retained SNP positions for the population data set if these positions were included in the genetic map construction. Adjacent SNP marker pairs were omitted if markers were separated by fewer than 500 bp. All linkage disequilibria calculations were made with VCFtools v. 0.1.12a (Danecek et al. 2011).

Data availability

NCBI BioSample accession numbers for parental strains are SRS383146, SRS383147, SRS383142, and SRS383143. Progeny sequence data are deposited under NCBI BioProject accession numbers PRJNA256988 (cross ST99CH3D1xST99CH3D7) and PRJNA256991 (cross ST99CH1A5xST99CH1E4).

Results

High-throughput progeny genotyping and crossover detection

Four parental isolates (3D1, 3D7, 1A5, and 1E4) collected from Swiss wheat fields in 1999 were used to construct two independent genetic maps. Progeny were genotyped based on RAD-seq (Etter et al. 2011), which consists of Illumina sequencing of DNA fragments immediately adjacent to a defined restriction site in the genome (generated by PstI in this study). Illumina reads obtained from each progeny were aligned to the reference genome of Z. tritici for SNP genotyping and filtering. The reference genome IPO323 is completely assembled, including telomeres and centromeres (Goodwin et al. 2011). Whole-genome resequencing data from the parental isolates (Torriani et al. 2011) was used to validate segregating SNPs among progeny.

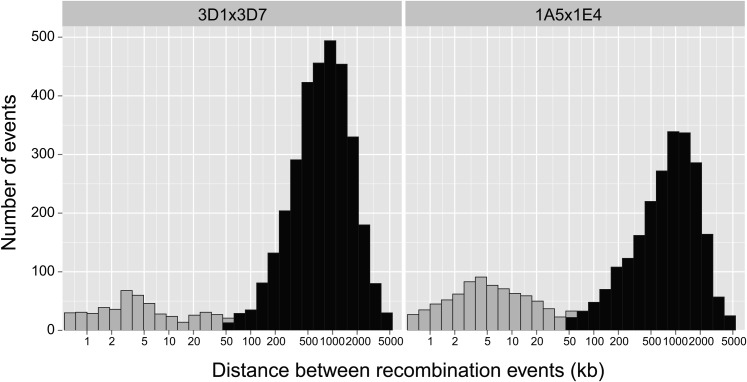

Recombination between homologs can result in either a crossover or a noncrossover. Crossovers result in the exchange of alleles over long chromosomal intervals. Noncrossovers lead to short intervals of unidirectional transfer among homologs (i.e., gene conversion). Distinguishing between noncrossover and crossover events is important because only the latter increase genetic diversity and break up haplotypes. In the model fungus S. cerevisiae, tracts of gene conversions resulting from noncrossover span a median of 1.8 kb and a maximum observed tract length of 40.8 kb (Mancera et al. 2008). Hence, we investigated the interval length between recombination events for all progeny and chromosomes. We observed a bimodal distribution of recombination event interval lengths (Figure 1). In both crosses, we found two modes corresponding to recombination event interval distances of 3–4 and ∼1000 kb, respectively.

Figure 1.

Physical distance between all detected recombination events per progeny summarized for each of the two analyzed crosses (3D1 × 3D7 and 1A5 × 1E4). A short distance between recombination events in a progeny may indicate a potential noncrossover. In this case, the two recombination events would be boundaries of a gene conversion tract. To conservatively identify true crossovers, a minimum distance of 50 kb was required for a recombination event to be considered a crossover (shaded in black) instead of a putative noncrossover event (shaded in gray). All analyses of recombination rates and hotspots are based on recombination events at least 50 kb from the nearest neighboring recombination event.

Genetic map construction and recombination rate variation among chromosomes

To conservatively estimate genetic map lengths based on crossover events, we required a minimum distance of 50 kb between recombination events. Genetic maps were constructed using the marker order known from physical positions of the SNP markers based on the reference genome sequence. The consistency of the physical and genetic marker distances and marker order was evaluated. A single problematic region was found on chromosome 13, so this chromosome was excluded from analyses requiring physical positions on the chromosome (see Materials and Methods and Figure S1).

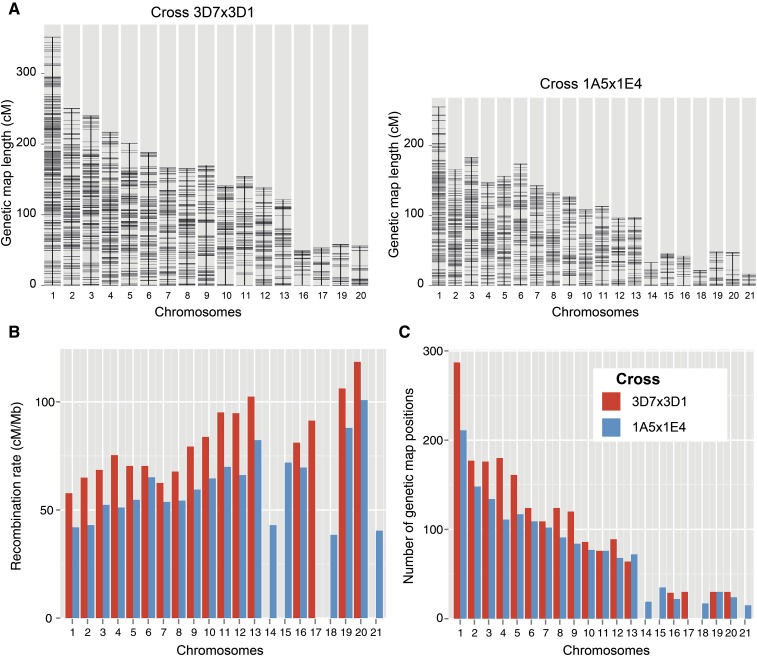

The total genetic map constructed for the cross 3D1 × 3D7 was based on 227 progeny and spanned 2723.6 cM. For the cross 1A5 × 1E4, the total map was based on 214 progeny and was slightly smaller (2158.9 cM). The number of genotyped SNP markers greatly exceeded (by ∼12–15 times) the number of genetic map positions (the minimal set of markers separated by at least one crossover). This shows that the SNP markers largely saturate the number of genetic map positions in the two crosses (Table 1, Table 2, and Figure 2). Recombination rates were inversely related to the length of the chromosome (Figure 2).

Table 2. Overview of genetic maps constructed in two crosses of Z. tritici.

| Cross 3D1 × 3D7 (227 progeny) | Cross 1A5 × 1E4 (214 progeny) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | Physical length (kb) | Genetic map length (cM) | Recombination rate (cM/Mb) | Genetic map positions | Genetic map length (cM) | Recombination rate (cM/Mb) | Genetic map positions |

| 1 | 6,088.8 | 351.58 | 57.74 | 287 | 255.62 | 41.98 | 211 |

| 2 | 3,860.1 | 250.74 | 64.96 | 177 | 165.97 | 43.00 | 148 |

| 3 | 3,505.3 | 240.19 | 68.52 | 176 | 183.56 | 52.37 | 134 |

| 4 | 2,880.0 | 217.03 | 75.36 | 180 | 147.23 | 51.12 | 111 |

| 5 | 2,861.8 | 201.39 | 70.37 | 161 | 156.52 | 54.69 | 117 |

| 6 | 2,675.0 | 188.22 | 70.36 | 124 | 174.2 | 65.12 | 109 |

| 7 | 2,665.3 | 166.57 | 62.50 | 109 | 143.18 | 53.72 | 102 |

| 8 | 2,443.6 | 165.56 | 67.75 | 124 | 132.77 | 54.33 | 91 |

| 9 | 2,142.5 | 169.94 | 79.32 | 120 | 127.35 | 59.44 | 84 |

| 10 | 1,682.6 | 140.97 | 83.78 | 86 | 108.63 | 64.56 | 77 |

| 11 | 1,624.3 | 154.48 | 95.11 | 76 | 113.57 | 69.92 | 76 |

| 12 | 1,462.6 | 138.58 | 94.75 | 89 | 96.74 | 66.14 | 68 |

| 13 | 1,185.8 | 121.46 | 102.43 | 64 | 97.56 | 82.28 | 72 |

| 14 | 773.1 | — | — | — | 33.22 | 42.97 | 19 |

| 15 | 639.5 | — | — | — | 45.98 | 71.90 | 35 |

| 16 | 607.0 | 49.24 | 81.11 | 29 | 42.26 | 69.62 | 22 |

| 17 | 584.1 | 53.34 | 91.32 | 30 | — | — | — |

| 18 | 573.7 | — | — | — | 22.08 | 38.49 | 17 |

| 19 | 549.9 | 58.39 | 106.19 | 30 | 48.36 | 87.95 | 30 |

| 20 | 472.1 | 55.94 | 118.49 | 30 | 47.58 | 100.78 | 24 |

| 21 | 409.2 | — | — | — | 16.54 | 40.42 | 15 |

| All | 39,686.3 | 2723.6 | 1892 | 2158.9 | 1592 | ||

For each chromosome, the physical length (kb), genetic map length (cM), and number of genetic map positions (minimal number of markers separated by at least one crossover) are shown for each chromosomal map. The recombination rate per chromosome is indicated in cM/Mb.

Figure 2.

Summary statistics of the genetic maps constructed for the two crosses 3D1 × 3D7 and 1A5 × 1E4. (A) Genetic map length per chromosome. Horizontal hatches show the positions of genetic markers in the genetic maps. In the cross 3D1 × 3D7, four accessory chromosomes were shared between the parental isolates and therefore could be used for map construction. In the cross 1A5 × 1E4, seven accessory chromosomes were shared between the parental isolates. (B) Recombination rates per chromosome expressed as cM/Mb. Genetic maps for the two crosses are distinguished by color. See C for color legend. (C) Number of genetic map positions per chromosome (minimal set of markers separated by at least one crossover).

The two crosses contained different sets of accessory chromosomes (i.e., chromosomes not present in all isolates of the species). In the cross 3D1 × 3D7, both parents carried a copy of accessory chromosomes 16, 17, 19, and 20. In the cross 1A5 × 1E4, accessory chromosomes 14–16 and 18–21 were present in both parents. Accessory chromosome 17 in the cross 1A5 × 1E4 was found to undergo spontaneous chromosomal fusion (Croll et al. 2013), but no other chromosomal rearrangements were documented in the two crosses. Accessory chromosomes are significantly shorter than core chromosomes, and this is reflected in genetic map lengths. Chromosomes 14 (33.2 cM), 18 (22.1 cM), and 21 (16.5 cM) showed the shortest genetic maps (Table 2 and Figure 2). Chromosomes 18 and 21 also were found to have the lowest recombination rates of any chromosome (38.5 and 40.4 cM/Mb).

Infrequent crossovers on some accessory chromosomes

We assessed the minimal number of crossover events that generated each progeny genotype. Average crossover counts decreased as expected with chromosome length (Figure S2 and Table 3). Crossover counts for a given core chromosome followed a Poisson-like distribution, and for each core chromosome we identified progeny with zero crossovers. We found that accessory chromosomes 16, 17, 19, and 20 of the cross 3D1 × 3D7 had crossover counts of 0.45–0.54 per progeny. Average crossover counts were lower in the cross 1A5 × 1E4. The lowest average crossover counts were 0.15 and 0.2 for chromosomes 21 and 18, respectively. The low crossover counts per accessory chromosome resulted in a large proportion of progeny that did not show a single crossover event (Figure S2). Most crossover events on accessory chromosomes occurred in narrow segments of the chromosome, as shown by large linked chromosomal segments among progeny (Figure S3). Chromosome 14 was found to recombine only in two narrow subtelomeric chromosomal sections.

Table 3. Overview of crossover counts per chromosome in progeny of the crosses 1A5 × 1E4 and 3D1 × 3D7.

| Cross 3D1 × 3D7 | Cross 1A5 × 1E4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromosome | Median crossover count | Mean crossover count | Crossing over count/Mb | Median crossover count | Mean crossover count | Crossing over count/Mb |

| 1 | 3 | 3.34 | 0.55 | 2 | 2.46 | 0.40 |

| 2 | 2 | 2.42 | 0.63 | 2 | 1.62 | 0.42 |

| 3 | 2 | 2.30 | 0.65 | 2 | 1.76 | 0.50 |

| 4 | 2 | 2.10 | 0.73 | 1 | 1.43 | 0.49 |

| 5 | 2 | 1.89 | 0.66 | 1 | 1.51 | 0.53 |

| 6 | 2 | 1.79 | 0.67 | 2 | 1.67 | 0.63 |

| 7 | 2 | 1.61 | 0.60 | 1 | 1.39 | 0.52 |

| 8 | 2 | 1.59 | 0.65 | 1 | 1.29 | 0.53 |

| 9 | 2 | 1.61 | 0.75 | 1 | 1.22 | 0.57 |

| 10 | 1 | 1.33 | 0.79 | 1 | 1.04 | 0.62 |

| 11 | 1 | 1.45 | 0.90 | 1 | 1.08 | 0.66 |

| 12 | 1 | 1.33 | 0.91 | 1 | 0.92 | 0.63 |

| 13 | 1 | 1.14 | 0.96 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.79 |

| 14 | — | — | — | 0 | 0.29 | 0.37 |

| 15 | — | — | — | 0 | 0.43 | 0.67 |

| 16 | 0 | 0.45 | 0.75 | 0 | 0.38 | 0.62 |

| 17 | 0 | 0.48 | 0.83 | — | — | — |

| 18 | — | — | — | 0 | 0.20 | 0.34 |

| 19 | 1 | 0.54 | 0.99 | 0 | 0.45 | 0.82 |

| 20 | 0 | 0.48 | 1.03 | 0 | 0.42 | 0.89 |

| 21 | — | — | — | 0 | 0.15 | 0.38 |

Recombination rate heterogeneity on chromosomes

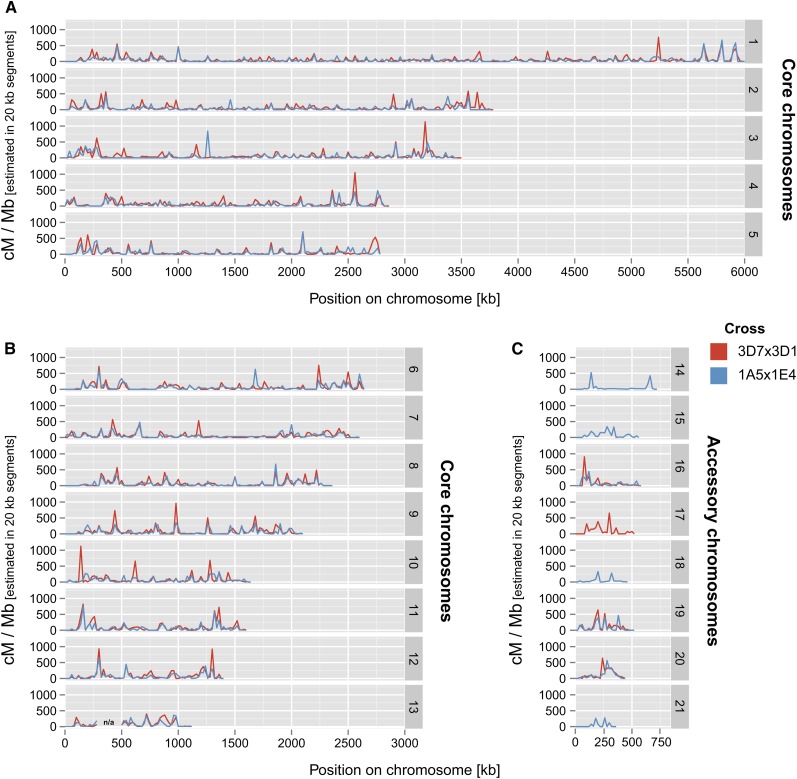

To identify variation in recombination rates, we estimated recombination rates in nonoverlapping 20-kb segments along chromosomes. Recombination rates in these segments were highly heterogeneous and varied between 0 and 1135 cM/Mb (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Recombination landscape of the plant pathogenic fungus Z. tritici. Recombination rates were estimated in two crosses by calculating genetic map distances (in cM) for nonoverlapping segments of 20 kb along chromosomes. Variations in recombination rates are shown for the crosses 1A5 × 1E4 (blue) and 3D1 ×3D7 (red). Recombination rates on accessory chromosomes are shown only for chromosomes that were found in both parental isolates of a cross. Chromosome 13 contains a region for which recombination rate variations could not be accurately determined (see Materials and Methods).

Central tracts of the chromosomes that were devoid of any recombination signal may indicate centromere locations. Recombination rates estimated per 20-kb segments were significantly correlated between the two crosses (Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficient r = 0.61, P < 2.2 × 10−16). We tested whether recombination rate heterogeneity along chromosomes was significantly different from expected for a random distribution of crossovers. For this, we tested whether the observed crossover counts per chromosomal segment deviated significantly from a predicted random distribution of crossovers. We found that crossovers were nonrandomly distributed in both crosses and at two different chromosomal scales (counting crossovers in 10- and 200-kb segments) (detailed statistics are reported in Figure S4). In addition, we found that crossovers were nonrandomly distributed on all core chromosomes when analyzed individually. On accessory chromosomes for which statistical analyses could be performed, crossovers were also nonrandomly distributed (see Table S1 for details on the statistical tests).

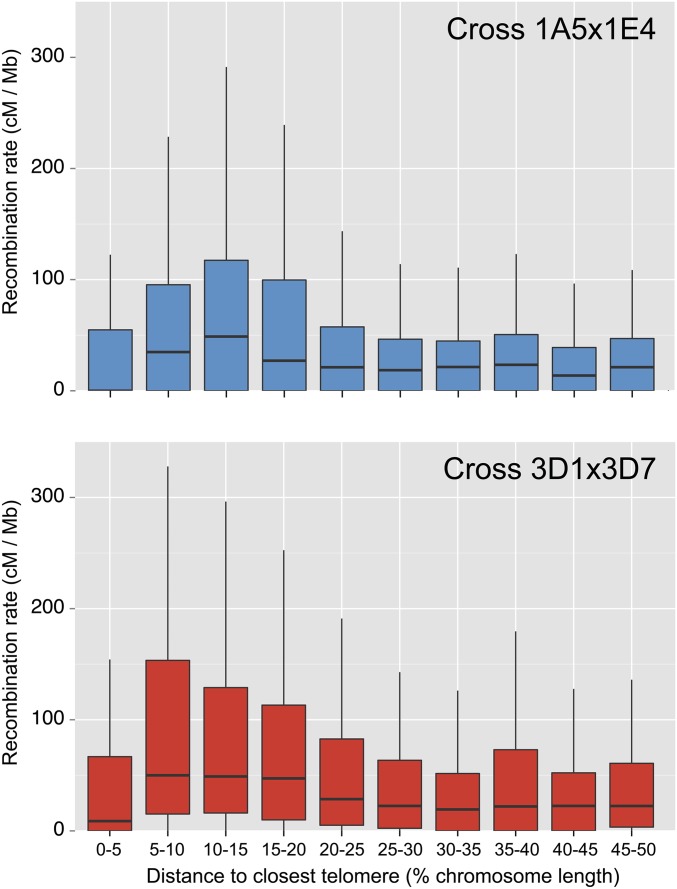

To identify systematic variations in recombination rates depending on chromosomal position, we summarized recombination rates on core chromosomes according to the relative distance to the closest telomere (Figure 4). Visual trends suggest that median recombination rates were highest in subtelomeric regions of chromosomes in both crosses (5–15% distance to the telomere). The lowest median recombination rates were found closest to the telomeres (within 5% distance). However, individual core chromosomes differed significantly for the distribution of recombination rates in relation to telomere distance (Figure S5).

Figure 4.

Recombination rate variations in relation to telomere distance. Recombination rates were calculated in nonoverlapping 10-kb segments for core chromosomes. Recombination rates then were summarized into 5% bins representing the relative distance to the telomere end. The box plot shows the median recombination rate (horizontal bar), the 25 and 75% quartiles as a solid box, and the 5 and 95% quantiles as vertical lines. Recombination rates were highest in both crosses for subtelomeric distances of 10–15% of the chromosome length. Core chromosomes vary from 1.19 to 6.09 Mb in length.

Localization of recombination hotspots

We aimed to identify narrow sequence tracts with the highest rates of exchange. For this, we counted the observed number of crossover events in nonoverlapping 10-kb sequence segments in both crosses. The average recombination rates per segment were 1.1 and 1.46 crossover events in the crosses 1A5 × 1E4 and 3D1 × 3D7, respectively. In the cross 1A5 × 1E4, we found that 76 segments showed 10 or more crossovers, representing 1.9% of the genome but 27.8% of all crossovers (Table S2). Similarly, in the cross 3D1 × 3D7, 130 hotspot segments were found, representing 3.3% of the genome and 38.2% of all crossovers (Table S3). The probability of observing 10 or more crossovers by chance was P < 4.3 × 10−7 (Poisson distribution with λ = 1.1 and 1.46, respectively, for 1A5 × 1E4 and 3D1 × 3D7). Hence, these hotspot segments represent highly unusual regions in the genome. The rate of exchange in the hotspots ranged from 4.4–17.6% of all progeny showing evidence of a crossover event. Hotspot locations were shared between the crosses 1A5 × 1E4 and 3D1 × 3D7 in 35 segments. The overlap between hotspots corresponds to 46.1% of all hotspots identified in 1A5 × 1E4 and 26.9% of all hotspots identified in 3D1 × 3D7.

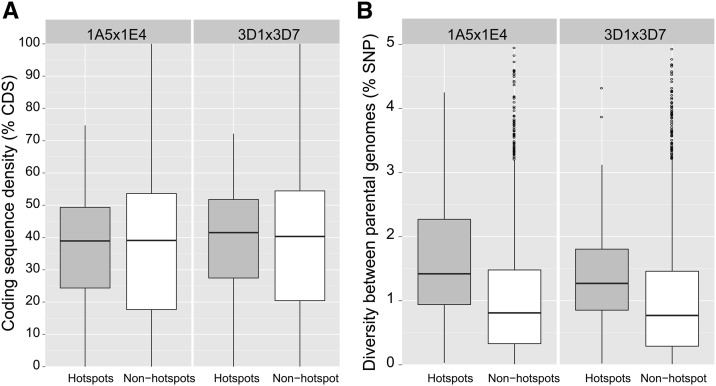

Association of recombination hotspots with genome characteristics

The Z. tritici genome is gene dense (31.5% coding sequences) and GC rich (51.7%). Chromosomal sequences contain long sections of high GC content interspersed with short sections of low GC content and low gene density (Goodwin et al. 2011). To test for genome characteristics associated with the presence of hotspots, we divided the entire genome into nonoverlapping 10-kb sequence segments and assessed differences between 10-kb sequences identified as hotspots (see earlier) vs. all other 10-kb segments. GC content was slightly but significantly higher in hotspots vs. the genomic background (53.6 vs. 52.2%, Student’s t-test, t = 3.42 and 5.17 and P = 0.0009 and 6.2 × 10−7 for the crosses 1A5 × 1E4 and 3D1 × 3D7, respectively). Coding sequence densities were not significantly different between the hotspots and the genomic background (Student’s t-test, P = ∼0.8) (Figure 5A). However, hotspot segments were significantly more polymorphic between parental genomes than in the genomic background. The mean SNP densities were 1.37 and 1.60% for the crosses 1A5 × 1E4 and 3D1 × 3D7, respectively, vs. the genomic background diversity of 1.01% (Student’s t-test, t = 4.50 and 5.45 and P = 1.41 × 10−5 and 6.27 × 10−7 for the crosses 1A5 × 1E4 and 3D1 × 3D7, respectively) (Figure 5B). Relationships between recombination rates and GC content, gene density, and polymorphism between parental genomes, respectively, are shown in Figure S6, Figure S7, and Figure S8.

Figure 5.

Differences in gene density and sequence diversity in the recombination hotspots and nonhotspots of the crosses 3D1 × 3D7 and 1A5 × 1E4. For both panels, the box plots show the median of the distribution (horizontal bar), the 25 and 75% quartiles as a solid box, and the 5 and 95% quantiles as vertical lines. (A) Differences in coding sequence density between hotspot segments (each 10 kb) and segments of the genomic background (nonhotspots) divided into 10-kb segments. (B) Differences in diversity between the two parental genomes (% SNP) assessed for hotspot segments (each 10 kb) and segments of the genomic background (nonhotspots) divided into 10-kb segments.

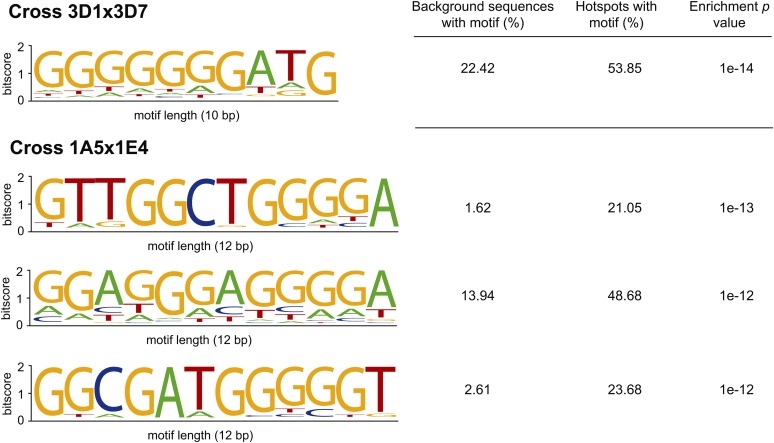

Recombination hotspots are enriched with GC-rich sequence motifs

Recombination hotspots were found to be enriched in short sequence motifs in animals and protozoa (Arnheim et al. 2007; Myers et al. 2008; Jiang et al. 2011). Evidence for motifs from fungi is species dependent. A simple sequence motif predicted recombination hotspots in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Steiner and Smith 2005), but no association was found for S. cerevisiae (Mancera et al. 2008). To identify potential motifs associated with recombination hotspots in Z. tritici, we analyzed 10-kb sequence segments showing 10 or more crossover events, as described earlier, using HOMER. We restricted the search to any possible 8-, 10-, and 12-bp motifs to avoid confounding effects of overlapping motifs. In the cross 3D1 × 3D7, the 10-bp (GGGGGGGATG) GC-rich motif was found in 53.9% of the hotspots compared to 22.4% of sequence segments not containing hotspots. After accounting for differences in GC content between hotspots and the genomic background, we found that hotspots were significantly enriched in this motif (P = 1 × 10−14) (Figure 6). Similarly, three GC-rich motifs were found to be significantly enriched in hotspots of the cross 1A5 × 1E4. The most significant motif was 12 bp (GTTGGCTGGGGA) and was found in 21.1% of all hotspot sequences compared to 1.6% in the genomic background (P = 1 × 10−13) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The top enriched oligonucleotide motifs that were identified by a de novo motif search in the recombination hotspots of the crosses 3D1 × 3D7 and 1A5 × 1E4. The enrichment of sequence motifs in recombination hotspots was tested using a hypergeometric test. The genomic background was segmented and binned according to GC content. Enrichment tests were performed using weighted background sequences reflecting the GC content distribution found in hotspots. Weighting background sequences avoided spurious enrichments as a result of differences in GC content between the genomic background and hotspots.

Recombination hotspots are enriched in genes encoding secreted proteins

Genes located in recombination hotspots may be subject to both increased mutation rates and higher rates of reshuffling of allelic variants in the population. Hence, the mutagenic potential and higher rates of adaptive evolution of recombination hotspots may lead to an enrichment in fast-evolving gene categories near hotspots. As earlier, we defined recombination hotspots as 10-kb segments showing 10 or more crossover events. Protein secretion is an important component of virulence in plant pathogenic fungi. We tested whether recombination hotspots were more likely to contain genes encoding secreted proteins. We used the data set of predicted secretory signal peptides to test for enrichment in hotspots. We found that in the cross 3D7 × 3D1, hotspots were significantly enriched for genes encoding secreted proteins (hypergeometric test, P = 0.0076). In the cross 1A5 × 1E4, hotspots also were enriched in genes encoding secreted proteins (P = 0.021).

We screened genes overlapping recombination hotspots for previously identified virulence candidate genes (Goodwin et al. 2011; Morais do Amaral et al. 2012; Brunner et al. 2013). We identified several categories of genes underlying important components of virulence in plant pathogenic fungi. Three small secreted proteins were found in hotspots overlapping in both crosses (Table 4). In cross 3D1 × 3D7 hotspots, we identified genes encoding cell wall degrading enzymes: the cutinase MgCUT4, the β-xylosidase MgXYL4, and an α-l-arabinofuranosidase.

Table 4. Genes with a predicted function in virulence located in recombination hotspots of Z. tritici.

| Cross | Protein ID | Protein characteristics | Chromosome and position | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D1 × 3D7 | 107758 | Small secreted tandem-repeat protein (TRP18) | 1 | 5652012–5653092 |

| 1A5 × 1E4 | 90262 | Small secreted protein | 1 | 5790864–5792208 |

| 3D1 × 3D7 | 99331 | Cutinase MgCUT4 under diversifying selection in Z. tritici for evasion of host | 2 | 3479067–3479856 |

| 3D1 × 3D7 and 1A5 × 1E4 | 104283 | Small cysteine-rich secreted protein | 4 | 2371447–2372597 |

| 3D1 × 3D7 | 42164 | Small secreted protein (ZPS1 family) | 5 | 224006–225198 |

| 1A5 × 1E4 | 105351 | Small secreted protein | 8 | 444217–444909 |

| 3D1 × 3D7 | 105728 | β-Xylosidase MgXYL4 under purifying selection in Z. tritici for substrate optimization | 9 | 989316–990401 |

| 3D1 × 3D7 and 1A5 × 1E4 | 110790 | Small secreted protein | 9 | 1270903–1271945 |

| 3D1 × 3D7 and 1A5 × 1E4 | 95797 | Small secreted protein | 9 | 1274185–1275470 |

| 3D1 × 3D7 | 111130 | Hemicellulase (ABFa α-l-arabinofuranosidase-A) | 10 | 1379647–1381988 |

| 3D1 × 3D7 | 111451 | Secreted α-1,2-mannosyltransferase ALG | 12 | 554075–555902 |

| 1A5 × 1E4 | 97702 | Aspartic protease | 16 | 71035–72069 |

Functional predictions and population genetic analyses of cell wall degrading enzymes and small secreted proteins are summarized where available (Goodwin et al. 2011; Morais do Amaral et al. 2012; Brunner et al. 2013)

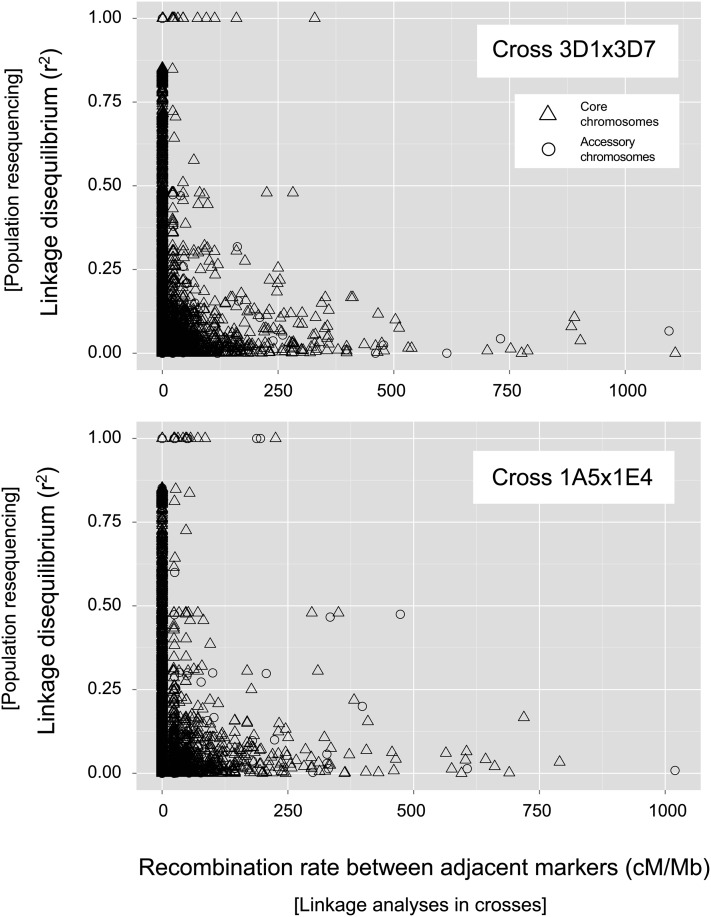

Recombination rates are correlated with population linkage disequilibrium

The extent of linkage disequilibrium (LD) among markers is a defining characteristic of genetic variation in a population. High LD is indicative of partial selective sweeps or population substructure. Recombination rates are expected to influence the extent of LD in populations because high recombination rates may reduce LD among markers. We tested whether recombination rates were correlated with LD in a natural Z. tritici population. For this, we resequenced 25 isolates from the same field population (including the parental isolates in this study). All isolates were genotyped at the same marker positions that were used in the recombination rate analyses. We calculated both the LD in the population and the recombination rate between all adjacent markers that were separated by at least 500 bp. We found that the recombination rate was negatively correlated with LD in both crosses (Spearman’s rank correlation, P < 2.2 × 10−16 and ρ = −0.213 and −0.184 for 3D1 × 3D7 and 1A5 × 1E4, respectively) (Figure 7). Adjacent markers with the highest LD in the natural field population were among the markers with the lowest recombination rates in the crosses.

Figure 7.

Recombination rates estimated from linkage analyses in crosses compared to linkage disequilibrium estimated from population resequencing data. Recombination rates between adjacent SNP markers were calculated as cM/Mb in the crosses 3D1 × 3D7 and 1A5 × 1E4. Resequencing data of field isolates from the same regional population as the parents were used to calculate linkage disequilbria (r2). For this, whole-genome sequencing data were analyzed for SNPs segregating at identical positions in the genome as in the SNP data set generated for the two crosses. Different symbols are used to show data points from core and accessory chromosomes.

Discussion

We established a dense map of recombination rates in the genome of a fungal plant pathogen based on two independent crosses. The SNP marker density was ∼12–15 times greater than the number of unique marker positions in the genetic map; hence, crossover events could be precisely localized to narrow chromosomal tracts. Because genomic analyses of all four meiotic products are currently not feasible in Z. tritici, we used a conservative approach to avoid confounding effects resulting from noncrossover events. By requiring a minimum distance of 50 kb between recombination events in a progeny, a small number of double crossovers occurring in a narrow interval may have been missed.

Recombination rates were highly heterogeneous and highest in subtelomeric recombination hotspots. The genetic maps produced for the two crosses were substantially larger than previously published maps for Z. tritici (2158.9–2723.6 vs. 1216–1946 cM) (Kema et al. 2002; Wittenberg et al. 2009). The larger map lengths likely were due to denser marker coverage in subtelomeric regions and larger progeny populations. Furthermore, in contrast to this study, no recombination was previously detected on accessory chromosomes (Wittenberg et al. 2009). The new genetic map of Z. tritici also was substantially longer than the map of the model fungi Coprinus cinereus [948 cM (Stajich et al. 2010)] and Neurospora crassa [1000 cM (Lambreghts et al. 2009)]. The genetic map of S. cerevisiae was estimated to be 4900 cM (Barton et al. 2008). The genetic maps differed between the two analyzed crosses by 565 cM. The genetic distance between the parental genomes, number of analyzed progeny, number of genotyped markers, and genotyping rates differed only marginally between the two crosses. Hence, these parameters are unlikely to explain differences in estimated genetic map lengths. However, analyzing physical distances between recombination events showed that the cross 1A5 × 1E4 had a lower proportion of long-distance (>50-kb) recombination events compared to the cross 3D1 × 3D7. Unknown recombination modifiers could be responsible for differences in crossover rates between crosses.

Low recombination rates and noncanonical meiosis on accessory chromosomes

We found that the frequency of reciprocal recombination (or crossover) per chromosome was positively correlated with chromosomal length. However, the recombination rate expressed per megabase was higher for smaller core chromosomes. The inverse relationship between recombination rate and chromosomal length is well established in S. cerevisiae (Mortimer et al. 1989; Cherry et al. 1997; Kaback et al. 1999). Crossover counts per chromosome reached 0.94–1.14 for the smallest core chromosomes. The occurrence of at least one crossover event per chromosome and meiosis promotes proper homologous segregation (Mather 1938; Hassold and Hunt 2001). Nondisjunction of chromosomes leads to aneuploidy (Baker et al. 1976). We found that some Z. tritici accessory chromosomes had unusually low crossover rates: approximately half the progeny of the cross 3D1 × 3D7 showed no crossovers, and in the cross 1A5 × 1E4, per-progeny crossover counts ranged from 0.15 to 0.45 per chromosome. Failure to undergo crossovers may contribute to frequent nondisjunction of particular accessory chromosomes (Wittenberg et al. 2009; Croll et al. 2013). Accessory chromosomes were frequently found to be lost or disomic following meiosis, indicative of nondisjunction (Wittenberg et al. 2009; Croll et al. 2013).

Lower than expected recombination rates (in cM/Mb) on some accessory chromosomes are expected to lead to substantial linkage disequilibrium among genetic variants in a population. The purging of deleterious mutations critically depends on sufficient recombination between loci. Therefore, some accessory chromosomes may be subject to more rapid mutation accumulation and decay. Reduced levels of gene density and shorter transcript lengths (Goodwin et al. 2011) may be indicative of a degeneration process operating on accessory chromosomes. Degeneration and rearrangements, in turn, may lead to further recombination suppression—a process similar to the one observed in sex chromosome evolution.

Recombination rate heterogeneity and hotspots

Recombination rates were highly heterogeneous along chromosomes. A large fraction of all crossover events was restricted to narrow chromosomal bands or hotspots of recombination. In the strongest hotspots, 18.5% of all progeny showed a crossover event within a 10-kb region. Recombination rates tended to be highest in subtelomeric regions of the chromosomes. Increased recombination rates in the chromosomal periphery were widely reported in animals (see, e.g., Backström et al. 2010; Bradley et al. 2011; Auton et al. 2012; Roesti et al. 2013) and plants (see, e.g., Akhunov et al. 2003; Anderson et al. 2003). In fungi, hotspot associations with subtelomeric regions were found in C. cinereus and S. cerevisiae (Barton et al. 2008; Stajich et al. 2010). Peripheral clustering of chromosomes (bouquet formation) during prophase I of meiosis is thought to favor proper homologous pairing and, by this process, to promote crossovers (Brown et al. 2005; Naranjo and Corredor 2008).

Recombination hotspots showed no strong difference in GC content or coding sequence density compared to the genomic background. However, associations of GC content and recombination rates are ubiquitous in eukaryotes (Gerton et al. 2000; Jensen-Seaman et al. 2004; Duret and Arndt 2008; Backström et al. 2010; Muyle et al. 2011; Auton et al. 2012). In S. cerevisiae, experimentally introduced GC-rich regions generate novel recombination hotspots (Wu and Lichten 1995). Hotspots in Z. tritici were enriched in G/C mononucleotide repeats compared to the genomic background. Similarly, S. cerevisiae hotspots were found to be enriched in 20- to 41-bp poly(A) stretches (Mancera et al. 2008). Z. tritici hotspots were in regions of higher diversity between the parental genomes compared to the genomic background. A potential explanation is that if hotspot locations persist over many generations, frequent gene conversion events may cause a higher mutation rate in hotspots and, hence, higher sequence diversity (Hurles 2005). Reduced diversity in regions of low recombination rates is well supported both by theory and by empirical data (Begun and Aquadro 1992; Nachman 2002; Cutter and Payseur 2013).

Divergent hotspot locations within a species

Hotspots are thought to be ephemeral in genomes because of their inherent self-destructive properties. A crossover is initiated by a double-strand break on one chromosome. The homologous chromosome serves as a template to repair the crossover initiator sequence. Therefore, the conversion process continually replaces any allele that favors increased recombination with its homolog. Studies of humans and chimpanzees showed that hotspot locations are rarely conserved, consistent with rapid turnover (Coop and Myers 2007; Auton et al. 2012). In contrast, hotspots were frequently conserved among a pair of divergent Saccharomyces species (Tsai et al. 2010). The unexpected conservation was attributed to the low frequency of sex, reducing the opportunity for biased gene conversion to erode hotspots. Z. tritici undergoes sexual reproduction very frequently (Zhan et al. 2002). Hotspot locations were only partially conserved (27–46%) between the two crosses established from isolates of the same regional population. A lack of overlap in hotspot locations may be due to the fact that not all hotspot locations were used during specific rounds of meiosis. However, each of the two analyzed crosses contained a large number of individual meiosis events reflecting the large number of analyzed ascospore progeny. Hence, stochastic variations in hotspot occupancies should be minimal.

Functional enrichment of genes in recombination hotspots

Plant pathogenic fungi rely on secretion to deliver effectors and toxins into the host, and genes encoding short secreted polypeptides were found to evolve very rapidly in pathogen genomes (Raffaele et al. 2010; Petre and Kamoun 2014). Recombination hotspots in Z. tritici were enriched in genes encoding secreted proteins. This may indicate that the localization of these genes in hotspots was favored by selection. We also screened hotspots in both crosses for the presence of candidate effector genes likely to play a role in pathogenesis (Table 4). Hotspots overlapping in both crosses contained genes encoding small, cysteine-rich secreted proteins. This gene category was found to be upregulated during host infection, and gene products likely modulate the host resistance response (Morais do Amaral et al. 2012; Mirzadi Gohari et al. 2014). Two cell wall degrading enzymes (MgCUT4 and MgXYL4) were specifically upregulated during host infection and showed evidence for selection in the pathogen population (Brunner et al. 2013). However, MgCUT4 and MgXYL4 were located in hotspots exclusive to the 3D1 × 3D7 cross, suggesting that associations of virulence genes and hotspots may be ephemeral over evolutionary time.

Consequences of recombination hotspots for genome evolution of pathogens

Regions of the genome with high recombination rates showed significantly lower levels of linkage disequilibrium in the natural population. This suggests that the effects of demography, periods of clonal reproduction, and selection were insufficient to affect the inverse relationship between recombination rates and linkage disequilibrium in the population. An emerging paradigm in the study of pathogenic organisms is that the genome organization reflects the intense selection pressure faced by pathogens (Croll and McDonald 2012; Raffaele and Kamoun 2012). The observed genome compartmentalization was termed the two-speed genome (Raffaele et al. 2010). The genome of the causative agent of the Irish potato famine, the oomycete Phytophthora infestans, contains fast-evolving, repeat-rich compartments hosting an abundance of pathogenicity genes (Raffaele et al. 2010). In contrast, genes encoding essential functions are preferentially located in GC-rich gene-dense compartments. However, the enrichment of effector genes in repeat-rich regions is not universal among pathogens. Many pathogen genomes are neither repeat rich nor contain large tracts of low GC content. Our findings in Z. tritici suggest that genome organization can evolve to compartmentalize gene functions correlated with variations in recombination rates. Recombination hotspots may constitute a previously unrecognized genomic compartment that favors the emergence of fast-evolving virulence genes in pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Christine Grossen, Sam Yeaman, Alan Brelsford, and Jessica Purcell for helpful comments on previous versions of the manuscript. The Genetic Diversity Center and the Quantitative Genomics Facility at ETH Zurich were used to generate sequence data. Funding was provided by Swiss National Science Foundation grants to D.C. (PA00P3_145360) and B.A.M. (31003A_134755) and an ETH Zurich grant (ETH-03 12) to D.C. and B.A.M.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: B. A. Payseur

Supporting information is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.115.180968/-/DC1

NCBI BioSample accession numbers for parental strains are SRS383146, SRS383147, SRS383142, and SRS383143. Progeny sequence data are deposited under NCBI BioProject accession numbers PRJNA256988 (cross ST99CH3D1 × ST99CH3D7) and PRJNA256991 (cross ST99CH1A5 × ST99CH1E4).

Literature Cited

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. Abecasis G. R., Altshuler D., Auton A., Brooks L. D., Durbin R. M., et al. , 2010. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 467: 1061–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhunov E. D., Goodyear A. W., Geng S., Qi L.-L., Echalier B., et al. , 2003. The organization and rate of evolution of wheat genomes are correlated with recombination rates along chromosome arms. Genome Res. 13: 753–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L. K., Doyle G. G., Brigham B., Carter J., Hooker K. D., et al. , 2003. High-resolution crossover maps for each bivalent of Zea mays using recombination nodules. Genetics 165: 849–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arends D., Prins P., Jansen R. C., Broman K. W., 2010. R/qtl: high-throughput multiple QTL mapping. Bioinformatics 26: 2990–2992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnheim N., Calabrese P., Tiemann-Boege I., 2007. Mammalian meiotic recombination hot spots. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41: 369–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auton A., Fledel-Alon A., Pfeifer S., Venn O., Ségurel L., et al. , 2012. A fine-scale chimpanzee genetic map from population sequencing. Science 336: 193–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awadalla P., 2003. The evolutionary genomics of pathogen recombination. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4: 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backström N., Forstmeier W., Schielzeth H., Mellenius H., Nam K., et al. , 2010. The recombination landscape of the zebra finch Taeniopygia guttata genome. Genome Res. 20: 485–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird N. A., Etter P. D., Atwood T. S., Currey M. C., Shiver A. L., et al. , 2008. Rapid SNP discovery and genetic mapping using sequenced RAD markers. PLoS One 3: e3376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker B. S., Carpenter A. T., Esposito M. S., Esposito R. E., Sandler L., 1976. The genetic control of meiosis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 10: 53–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett L. G., Thrall P. H., Dodds P. N., Linde C. C., 2009. Diversity and evolution of effector loci in natural populations of the plant pathogen Melampsora lini. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26: 2499–2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton A. B., Pekosz M. R., Kurvathi R. S., Kaback D. B., 2008. Meiotic recombination at the ends of chromosomes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 179: 1221–1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun D. J., Aquadro C. F., 1992. Levels of naturally occurring DNA polymorphism correlate with recombination rates in D. melanogaster. Nature 356: 519–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B., 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley K. M., Breyer J. P., Melville D. B., Broman K. W., Knapik E. W., et al. , 2011. An SNP-based linkage map for zebrafish reveals sex determination loci. G3 1: 3–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. W., Judis L., Chan E. R., Schwartz S., Seftel A., et al. , 2005. Meiotic synapsis proceeds from a limited number of subtelomeric sites in the human male. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 77: 556–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner P. C., Torriani S. F. F., Croll D., Stukenbrock E. H., McDonald B. A., 2013. Coevolution and life cycle specialization of plant cell wall degrading enzymes in a hemibiotrophic pathogen. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30: 1337–1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull J. J., 1983. Evolution of Sex Determining Mechanisms. Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco. [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes E. J., Li W., Ren P., Lewit Y., Voelz K., et al. , 2011. A diverse population of Cryptococcus gattii molecular type VGIII in southern Californian HIV/AIDS patients. PLoS Pathog. 7: e1002205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B., Charlesworth D., 2000. The degeneration of Y chromosomes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355: 1563–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry J. M., Ball C., Weng S., Juvik G., Schmidt R., et al. , 1997. Genetic and physical maps of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 387: 67–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coop G., Myers S. R., 2007. Live hot, die young: transmission distortion in recombination hotspots. PLoS Genet. 3: e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowger C., McDonald B. A., Mundt C. C., 2002. Frequency of sexual reproduction by Mycosphaerella graminicola on partially resistant wheat cultivars. Phytopathology 92: 1175–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowger C., Brunner P. C., Mundt C. C., 2008. Frequency of sexual recombination by Mycosphaerella graminicola in mild and severe epidemics. Phytopathology 98: 752–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll D., McDonald B. A., 2012. The accessory genome as a cradle for adaptive evolution in pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 8: e1002608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croll D., Zala M., McDonald B. A., 2013. Breakage-fusion-bridge cycles and large insertions contribute to the rapid evolution of accessory chromosomes in a fungal pathogen. PLoS Genet. 9: e1003567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutter A. D., Payseur B. A., 2013. Genomic signatures of selection at linked sites: unifying the disparity among species. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14: 262–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P., Auton A., Abecasis G., Albers C. A., Banks E., et al. 1000 Genomes Project Analysis Group , 2011. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27: 2156–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo M. A., Banks E., Poplin R., Garimella K. V., Maguire J. R., et al. , 2011. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat. Genet. 43: 491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didelot X., Achtman M., Parkhill J., Thomson N. R., Falush D., 2007. A bimodal pattern of relatedness between the Salmonella Paratyphi A and Typhi genomes: convergence or divergence by homologous recombination? Genome Res. 17: 61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouaud J., 2005. Variation in crossing-over rates across chromosome 4 of Arabidopsis thaliana reveals the presence of meiotic recombination “hot spots.” Genome Res. 16: 106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret L., Arndt P. F., 2008. The impact of recombination on nucleotide substitutions in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret L., Galtier N., 2009. Biased gene conversion and the evolution of mammalian genomic landscapes. Annu Rev Genom Hum G 10: 285–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etter P. D., Bassham S., Hohenlohe P. A., Johnson E. A., Cresko W. A., 2011. SNP discovery and genotyping for evolutionary genetics using RAD sequencing. Methods Mol. Biol. 772: 157–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrer R. A., Weinert L. A., Bielby J., Garner T. W. J., Balloux F., et al. , 2011. Multiple emergences of genetically diverse amphibian-infecting chytrids include a globalized hypervirulent recombinant lineage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 18732–18736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M. C., Garner T. W. J., Walker S. F., 2009. Global emergence of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and amphibian chytridiomycosis in space, time, and host. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63: 291–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser J. A., Giles S. S., Wenink E. C., Geunes-Boyer S. G., Wright J. R., et al. , 2005. Same-sex mating and the origin of the Vancouver Island Cryptococcus gattii outbreak. Nature 437: 1360–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerton J. L., DeRisi J., Shroff R., Lichten M., Brown P. O., et al. , 2000. Global mapping of meiotic recombination hotspots and coldspots in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 11383–11390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin S. B., M’Barek S. Ben, Wittenberg A. H. J., Crane C. F., Hane J. K., et al. , 2011. Finished genome of the fungal wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola reveals dispensome structure, chromosome plasticity, and stealth pathogenesis. PLoS Genet. 7: e1002070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg M. E., Bonnefoy S., Hehl A. B., Suzuki Y., Boothroyd J. C., 2001. Success and virulence in Toxoplasma as the result of sexual recombination between two distinct ancestries. Science 294: 161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton W. D., 1980. Sex vs. non-sex vs. parasite. Oikos 35: 282–290. [Google Scholar]

- Hassold T., Hunt P., 2001. To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2: 280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S., Benner C., Spann N., Bertolino E., Lin Y. C., et al. , 2010. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38: 576–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill W. G., Robertson A., 1966. The effect of linkage on limits to artificial selection. Genet. Res. 8: 269–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt K. E., Parkhill J., Mazzoni C. J., Roumagnac P., Weill F.-X., et al. , 2008. High-throughput sequencing provides insights into genome variation and evolution in Salmonella typhi. Nat. Genet. 40: 987–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurles M., 2005. How homologous recombination generates a mutable genome. Hum. Genomics 2: 179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Seaman M. I., Furey T. S., Payseur B. A., Lu Y., Roskin K. M., et al. , 2004. Comparative recombination rates in the rat, mouse, and human genomes. Genome Res. 14: 528–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Li N., Gopalan V., Zilversmit M. M., Varma S., et al. , 2011. High recombination rates and hotspots in a Plasmodium falciparum genetic cross. Genome Biol. 12: R33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaback D. B., Barber D., Mahon J., Lamb J., You J., 1999. Chromosome size-dependent control of meiotic reciprocal recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the role of crossover interference. Genetics 152: 1475–1486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasov T. L., Horton M. W., Bergelson J., 2014. Genomic variability as a driver of plant-pathogen coevolution? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 18C: 24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kema G. H. J., Verstappen E. C. P., Todorova M., Waalwijk C., 1996. Successful crosses and molecular tetrad and progeny analyses demonstrate heterothallism in Mycosphaerella graminicola. Curr. Genet. 30: 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kema G. H. J., Goodwin S. B., Hamza S., Verstappen E. C. P., Cavaletto J. R., et al. , 2002. A combined amplified fragment length polymorphism and randomly amplified polymorphism DNA genetic linkage map of Mycosphaerella graminicola, the septoria tritici leaf blotch pathogen of wheat. Genetics 161: 1497–1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong A., Gudbjartsson D. F., Sainz J., Jonsdottir G. M., Gudjonsson S. A., et al. , 2002. A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nat. Genet. 31: 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambreghts R., Shi M., Belden W. J., Decaprio D., Park D., et al. , 2009. A high-density single nucleotide polymorphism map for Neurospora crassa. Genetics 181: 767–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Salzberg S. L., 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9: 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln S. E., Lander E. S., 1992. Systematic detection of errors in genetic linkage data. Genomics 14: 604–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lively C. M., 2010. A review of red queen models for the persistence of obligate sexual reproduction. J. Hered. 101: S13–S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancera E., Bourgon R., Brozzi A., Huber W., Steinmetz L. M., 2008. High-resolution mapping of meiotic crossovers and non-crossovers in yeast. Nature 454: 479–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather K., 1938. Crossing-over. Biol. Rev. 13: 252–292. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald B. A., Linde C., 2002. Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40: 349–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menkis A., Jacobson D. J., Gustafsson T., Johannesson H., 2008. The mating-type chromosome in the filamentous ascomycete Neurospora tetrasperma represents a model for early evolution of sex chromosomes. PLoS Genet. 4: e1000030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzadi Gohari A., Mehrabi R., Robert O., Ince I. A., Boeren S., et al. , 2014. Molecular characterization and functional analyses of ZtWor1, a transcriptional regulator of the fungal wheat pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15: 394–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais do Amaral A., Antoniw J., Rudd J. J., Hammond-Kosack K. E., 2012. Defining the predicted protein secretome of the fungal wheat leaf pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. PLoS One 7: e49904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morran L. T., Schmidt O. G., Gelarden I. A., Parrish R. C., Lively C. M., 2011. Running with the red queen: host-parasite coevolution selects for biparental sex. Science 333: 216–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortimer R. K., Schild D., Contopoulou C. R., Kans J. A., 1989. Genetic map of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, edition 10. Yeast 5: 321–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyle A., Serres-Giardi L., Ressayre A., Escobar J., Glémin S., 2011. GC-biased gene conversion and selection affect GC content in the Oryza genus (rice). Mol. Biol. Evol. 28: 2695–2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers S., Bottolo L., Freeman C., McVean G., Donnelly P., 2005. A fine-scale map of recombination rates and hotspots across the human genome. Science 310: 321–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers S., Freeman C., Auton A., Donnelly P., McVean G., 2008. A common sequence motif associated with recombination hot spots and genome instability in humans. Nat. Genet. 40: 1124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachman M. W., 2002. Variation in recombination rate across the genome: evidence and implications. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12: 657–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo T., Corredor E., 2008. Nuclear architecture and chromosome dynamics in the search of the pairing partner in meiosis in plants. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 120: 320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M. I., Holmes E. C., 2007. The evolution of epidemic influenza. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8: 196–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll A., Kildea S., Doohan F., Spink J., 2014. The wheat-Septoria conflict: a new front opening up? Trends Plant Sci. 19: 602–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto S. P., Barton N. H., 1997. The evolution of recombination: removing the limits to natural selection. Genetics 147: 879–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto S. P., Lenormand T., 2002. Resolving the paradox of sex and recombination. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3: 252–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petre B., Kamoun S., 2014. How do filamentous pathogens deliver effector proteins into plant cells? PLoS Biol. 12: e1001801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaele S., Kamoun S., 2012. Genome evolution in filamentous plant pathogens: why bigger can be better. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10: 417–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaele S., Farrer R. A., Cano L. M., Studholme D. J., MacLean D., et al. , 2010. Genome evolution following host jumps in the Irish potato famine pathogen lineage. Science 330: 1540–1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesti M., Moser D., Berner D., 2013. Recombination in the threespine stickleback genome: patterns and consequences. Mol. Ecol. 22: 3014–3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum E. B., Stajich J. E., Maddox N., Eisen M. B., 2008. Global gene expression profiles for life stages of the deadly amphibian pathogen Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105: 17034–17039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajich J. E., Wilke S. K., Ahrén D., Au C. H., Birren B. W., et al. , 2010. Insights into evolution of multicellular fungi from the assembled chromosomes of the mushroom Coprinopsis cinerea (Coprinus cinereus). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 11889–11894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner W. W., Smith G. R., 2005. Natural meiotic recombination hot spots in the Schizosaccharomyces pombe genome successfully predicted from the simple sequence motif M26. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 9054–9062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stukenbrock E. H., McDonald B. A., 2008. The origins of plant pathogens in agro-ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46: 75–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrall P. H., Laine A.-L., Ravensdale M., Nemri A., Dodds P. N., et al. , 2012. Rapid genetic change underpins antagonistic coevolution in a natural host-pathogen metapopulation. Ecol. Lett. 15: 425–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torriani S. F., Brunner P. C., McDonald B. A., Sierotzki H., 2009. QoI resistance emerged independently at least 4 times in European populations of Mycosphaerella graminicola. Pest Manag. Sci. 65: 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torriani S. F. F., Stukenbrock E. H., Brunner P. C., McDonald B. A., Croll D., 2011. Evidence for extensive recent intron transposition in closely related fungi. Curr. Biol. 21: 2017–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai I. J., Burt A., Koufopanou V., 2010. Conservation of recombination hotspots in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 7847–7852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster M. T., Hurst L. D., 2012. Direct and indirect consequences of meiotic recombination: implications for genome evolution. Trends Genet. 28: 101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendte J. M., Miller M. A., Lambourn D. M., Magargal S. L., Jessup D. A., et al. , 2010. Self-mating in the definitive host potentiates clonal outbreaks of the apicomplexan parasites Sarcocystis neurona and Toxoplasma gondii. PLoS Genet. 6: e1001261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. A., Makova K. D., 2009. Genomic analyses of sex chromosome evolution. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 10: 333–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg A. H. J., van der Lee T. A. J., Ben M’Barek S., Ware S. B., Goodwin S. B., et al. , 2009. Meiosis drives extraordinary genome plasticity in the haploid fungal plant pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. PLoS One 4: e5863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T. C., Lichten M., 1995. Factors that affect the location and frequency of meiosis-induced double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 140: 55–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan J., Kema G., Waalwijk C., McDonald B. A., 2002. Distribution of mating type alleles in the wheat pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola over spatial scales from lesions to continents. Fungal Genet. Biol. 36: 128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan J., Linde C. C., Jürgens T., Merz U., Steinebrunner F., et al. , 2005. Variation for neutral markers is correlated with variation for quantitative traits in the plant pathogenic fungus Mycosphaerella graminicola. Mol. Ecol. 14: 2683–2693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan J., Mundt C. C., McDonald B. A., 2007. Sexual reproduction facilitates the adaptation of parasites to antagonistic host environments: evidence from empirical study in the wheat-Mycosphaerella graminicola system. Int. J. Parasitol. 37: 861–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

NCBI BioSample accession numbers for parental strains are SRS383146, SRS383147, SRS383142, and SRS383143. Progeny sequence data are deposited under NCBI BioProject accession numbers PRJNA256988 (cross ST99CH3D1xST99CH3D7) and PRJNA256991 (cross ST99CH1A5xST99CH1E4).