Abstract

Aims: The heart responds to physiological and pathophysiological stress factors by increasing its production of nitric oxide (NO), which reacts with intracellular glutathione to form S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO), a protein S-nitrosylating agent. Although S-nitrosylation protects some cardiac proteins against oxidative stress, direct effects on myofilament performance are unknown. We hypothesize that S-nitrosylation of sarcomeric proteins will modulate the performance of cardiac myofilaments. Results: Incubation of intact mouse cardiomyocytes with S-nitrosocysteine (CysNO, a cell-permeable low-molecular-weight nitrosothiol) significantly decreased myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. In demembranated (skinned) fibers, S-nitrosylation with 1 μM GSNO also decreased Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction and 10 μM reduced maximal isometric force, while inhibition of relaxation and myofibrillar ATPase required higher concentrations (≥100 μM). Reducing S-nitrosylation with ascorbate partially reversed the effects on Ca2+ sensitivity and ATPase activity. In live cardiomyocytes treated with CysNO, resin-assisted capture of S-nitrosylated protein thiols was combined with label-free liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry to quantify S-nitrosylation and determine the susceptible cysteine sites on myosin, actin, myosin-binding protein C, troponin C and I, tropomyosin, and titin. The ability of sarcomere proteins to form S-NO from 10–500 μM CysNO in intact cardiomyocytes was further determined by immunoblot, with actin, myosin, myosin-binding protein C, and troponin C being the more susceptible sarcomeric proteins. Innovation and Conclusions: Thus, specific physiological effects are associated with S-nitrosylation of a limited number of cysteine residues in sarcomeric proteins, which also offer potential targets for interventions in pathophysiological situations. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 23, 1017–1034.

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important regulator of cardiac contractility (34). In cardiomyocytes, NO is synthesized primarily by endothelial or neuronal NO synthase isoforms, which convert l-arginine to citrulline and NO, or by the reduction of nitrate and nitrite to NO (9–10). NO can alter cellular function indirectly by activating cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate signaling pathways and cellular kinases or directly by forming S-nitrosothiols (SNOs; i.e., S-nitrosylation) (9, 34, 60). Together with S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial and Ca2+-handling proteins, these post-translational modifications can profoundly alter cardiomyocyte metabolism and contractility (12, 15, 25, 32, 55).

In contrast to the wealth of data on protein S-nitrosylation in metabolic processes and Ca2+ handling, very little is known about the impact of NO and its derivatives on contractile proteins. Properly controlled, low concentrations of NO and its natural metabolites, S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) and S-nitrosocysteine (CysNO), can protect against the oxidative damage caused by ischemia/reperfusion (25, 32, 55, 57). A number of studies have addressed the functional effects of oxidation in this context and some have looked at S-nitrosylation of selected proteins (18, 56), but none has examined specifically the consequences of S-nitrosylation across the entire roster of cardiac contractile proteins.

Innovation.

Under various kinds of stress ranging from strenuous exercise to sepsis, cardiac muscle produces more nitric oxide, leading to S-nitrosylation of protein thiols. The functional consequences of S-nitrosylating sarcomeric proteins on their susceptible cysteine residues are qualitatively similar to those found for oxidative stress, but milder. We infer that low levels of S-nitrosylation initially contribute small decreases in Ca2+ sensitivity to the downregulation of contractile function. As stress intensifies into the realm of pathophysiology, sarcomeric protein S-nitrosylation accumulates and can depress cross-bridge turnover and relaxation. Nevertheless, these modifications protect against permanent damage by virtue of their reversibility.

The concentration of NO and its metabolites, including S-nitrosothiols, varies substantially under physiological conditions and it increases markedly in contracting muscle and myocytes (4, 10, 14, 44). In a previous study, we demonstrated an increase in nitrite and protein-SNO in vertebrate skeletal muscle following exercise and characterized the effects of GSNO-dependent S-nitrosylation on myosin ATPase in vitro (41). Maximum inhibition was 20–30%, attributable to a small population of SNO-cysteines, and it was readily reversible.

Using 0.5–5 μM CysNO as an NO donor for S-nitrosylated myosin-transporting actin filaments, Evangelista et al. (18) found a similar level of inhibition. Different NO donors reduced Ca2+ sensitivity of permeabilized cardiac myocytes and intact fast-twitch fibers at 50 and 250 μM, respectively, with no effect on maximal isometric force; S-nitrosylation was not investigated (3, 50). In humans, S-nitrosylation of cardiac tropomyosin was correlated with end-stage heart failure, but a specific defect at the level of the myofilaments was not identified (11). Thus, it is not yet clear how NO affects sarcomeric proteins, nor whether it is effective over all or part of a range of concentrations that covers physiological and pharmacological doses.

Focusing on S-nitrosylation, we hypothesized that NO can regulate contraction in the heart by modifying sarcomeric protein performance in situ. We sought to investigate these effects in intact cardiomyocytes and skinned cardiac muscle preparations and to identify the repertoire of cysteine targets among sarcomeric proteins. In addition, we determined their overall susceptibility to S-nitrosylation in myofibrils and intact cardiomyocytes and the capacity for reversibility in myofibrils. In general, S-nitrosylation directly modulates cardiac myofilament function, opening new possibilities for intervention in pathological situations.

Results

S-nitrosylation of contractile proteins in cardiomyocytes and demembranated myofibrils

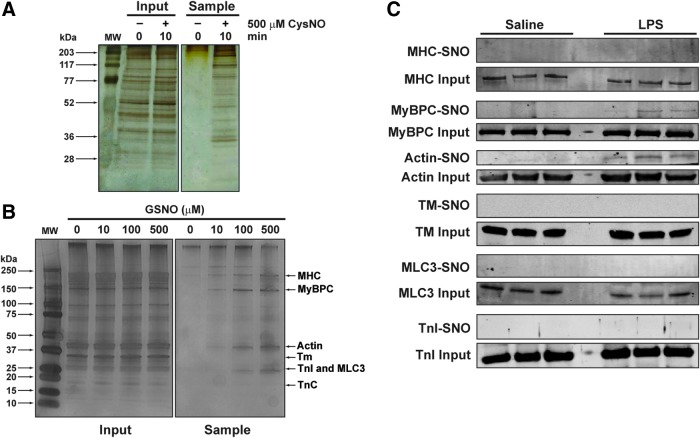

S-nitrosylation of sarcomeric proteins has only been examined using purified proteins or in preparations lacking intact cell membranes (32, 39, 41, 55). To better understand how SNO-proteins occur in a more physiological system, we first examined S-nitrosylation in intact cardiac muscle cells treated with the NO donor, CysNO, for 10 min. A robust increase in S-nitrosylated proteins occurred, as assessed by the resin-assisted capture of S-nitrosothiols (SNO-RAC) technique, which uses thiopropyl sepharose 6B (TPS) to capture SNO-proteins (Fig. 1A). These data are consistent with previous rapid kinetics of S-nitrosylation in other mammalian cell types (20) and they also show that myoglobin, an endogenous NO scavenger, does not interfere.

FIG. 1.

S-nitrosylation of sarcomeric proteins. (A) Protein S-nitrosylation in cardiomyocytes. Intact cardiomyocytes were treated with 500 μM CysNO for 0 or 10 min in Tyrode's buffer with 1.8 mM CaCl2. The cells were lysed with blocking buffer and the homogenates subjected to SNO-RAC (see the Materials and Methods section for further details). Input shows SDS-PAGE and silver staining of homogenates before SNO-RAC. Sample, after SNO-RAC; (B) protein S-nitrosylation in CMFs. CMFs were incubated with 10, 100, and 500 μM GSNO in relaxing solution for 60 min in the dark, then processed for SNO-RAC. SDS-PAGE and silver staining of CMFs on 4–15% acrylamide gels were performed before (input) and after (sample) SNO-RAC; (C) protein S-nitrosylation in hearts from LPS-treated mice. Mice were treated for 12 h with either LPS (10 mg/kg; n = 3 mice) or vehicle (PBS; n = 3 mice). Each heart was excised, homogenized, and then processed for SNO-RAC. SDS-PAGE and silver staining of 10% acrylamide gels performed before (input) and after (sample) SNO-RAC. Proteins: MHC, MyBPC3, actin, Tm, cardiac TnI, MLC3, and cardiac TnC. CMFs, cardiac myofibrils; CysNO, S-nitrosocysteine; GSNO, S-nitrosoglutathione; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MHC, myosin heavy chain; MLC3, myosin essential light chain; MW, molecular weight markers; MyBPC3, myosin-binding protein C; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; SNO-RAC, resin-assisted capture of S-nitrosothiols; Tm, α-tropomyosin; TnC, troponin C; TnI, troponin I. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

The preparation of cardiac myofibrils (CMFs) removes cytosolic protein and most membrane-bound proteins, making this system well suited for studying the S-nitrosylation of only sarcomeric proteins. In this study, we chose a long exposure time (60 min) to visualize results from a wide range of concentrations and examined the dose-dependent S-nitrosylation of CMF proteins by GSNO using SNO-RAC. Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and silver staining of proteins eluted from the resin showed a dose-dependent S-nitrosylation of numerous myofibrillar proteins, including myosin heavy chain, myosin-binding protein C, and actin (Fig. 1B).

To test whether sarcomeric proteins were also S-nitrosylated, but now in cardiac muscle in vivo, mice were treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to produce endotoxemia, followed by euthanasia 12 h later. This insult has been shown to increase the total amount of S-nitrosothiols (from proteins and from low-molecular-weight thiols) in the heart in rodents (17). As shown in Figure 1C, myosin-binding protein C (MyBPC) and actin bands can be detected only in heart homogenate samples from the LPS-treated group (MyBPC-SNO and actin-SNO). These results suggest that cardiac sarcomeric proteins are susceptible to S-nitrosylation in pathological conditions in vivo, such as in a model of acute endotoxemia.

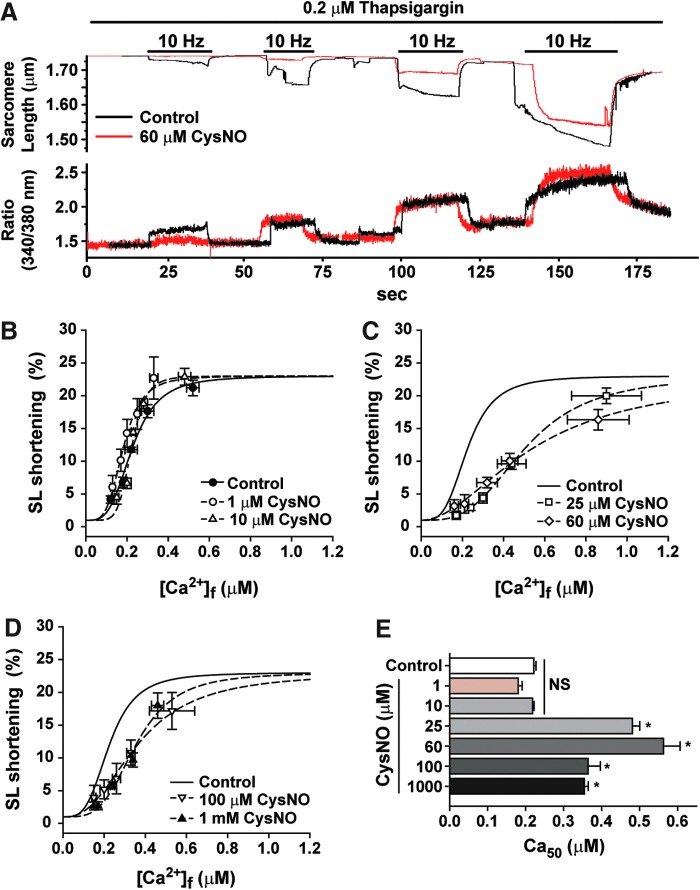

Myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in intact cardiomyocytes

Intact live cardiomyocytes were incubated with different concentrations of CysNO for 10 min and the myofilament Ca2+ responses were recorded as demonstrated in Figure 2A (see the Materials and Methods section). Incubation of cardiomyocytes with 1 and 10 μM CysNO did not affect the sarcomere length (SL) shortening as a function of intracellular [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2B). Cardiomyocytes incubated with 25, 60, 100, and 1000 μM CysNO displayed a statistically significant rightward shift in the SL shortening-[Ca2+]i (μM) relationship (Fig. 2C, D). The Ca50 for each condition, which represents the myofilament Ca2+sensitivity, is shown in Figure 2E, demonstrating a myofilament Ca2+ desensitization at concentrations ≥25 μM CysNO.

FIG. 2.

Myofilament Ca2+ responsiveness is depressed in intact cardiomyocytes incubated with CysNO. (A) Representative traces of an experiment showing the simultaneous measurements of Fura-2 fluorescence (Ratio, which is converted to [Ca2+]i) and SL shortening in a single cardiomyocyte. Chamber contained Tyrode's buffer with 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 5 mM CaCl2. (B–D) Percent change in SL shortening responses to [Ca2+]i in intact cardiomyocytes incubated with different CysNO concentrations (as indicated) for 10 min; (E) myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, represented as Ca50 ([Ca2+]i for half-maximal SL shortening), obtained from the sigmoid equation (as described in the Materials and Methods section) in individual experiments of (B–D). Mean ± SEM.; n = 5. NS, not statistically different from control; *p < 0.01 versus control; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison post-test. SEM, standard error of the mean; SL, sarcomere length. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

It is well known that phosphorylation of troponin I and myosin-binding protein C by protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) alters cardiac myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity. To determine whether the Ca2+ desensitization detected with CysNO treatment was mediated through endogenous PKA or PKC activation, the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was also measured in the presence of inhibitors for these kinases, H-89 and Gö6983, respectively. Incubation of cardiomyocytes with H-89 for 15 min did not affect the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 3A). However, H-89 abolished the effect of 60 μM CysNO on the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, but not 100 μM CysNO (Fig. 3B–D). These results suggest that at low CysNO levels, the majority of the effect on Ca2+ sensitivity is through PKA activation, while at high CysNO levels, the S-nitrosylation of sarcomeric proteins directly modulates the myofilament Ca2+-binding function. Incubation of cardiomyocytes with Gö6983 for 15 min decreased the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 3E, G). The combination of Gö6983 and 60 μM CysNO had a cumulative effect on Ca2+ sensitivity (Fig. 3F, G), suggesting that CysNO does not exert its effect on the myofilament by activating PKC.

FIG. 3.

CysNO decreases myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity in cardiomyocytes preincubated either with the PKA inhibitor, H-89, or the PKC inhibitor, Gö6983. (A) Comparison of the SL shortening versus [Ca2+]i relationship (as shown in Fig. 2B–D) in cardiomyocytes treated with H-89 for 15 min and the control condition (i.e., no CysNO and no H-89; black line); (B, C) SL shortening versus [Ca2+]i relationship in cardiomyocytes treated with H-89 (15 min), followed by 60 μM CysNO (10 min; B) or 100 μM CysNO (10 min; C); (D) myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, represented as Ca50 from the experiments of (A–C) and Figure 2E; Mean ± SEM.; n = 5 mice. *p < 0.0001 versus control, †p < 0.01 versus H-89. NS, not statistically different versus control or versus H-89; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison post-test; (E) comparison of the SL shortening versus [Ca2+]i relationship in cardiomyocytes treated with Gö6983 for 15 min and the control condition (i.e., no CysNO and no Gö6983; black line); (F) SL shortening versus [Ca2+]i relationship in cardiomyocytes treated with Gö6983, followed by 60 μM CysNO (10 min); (G) myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, represented as Ca50 from the experiments of (E, F), and Figure 2E. Mean ± SEM; n = 4 mice. *p < 0.001 versus control, ‡p < 0.01 versus 60 μM GSNO; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison post-test. PKA, protein kinase A; PKC, protein kinase C. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

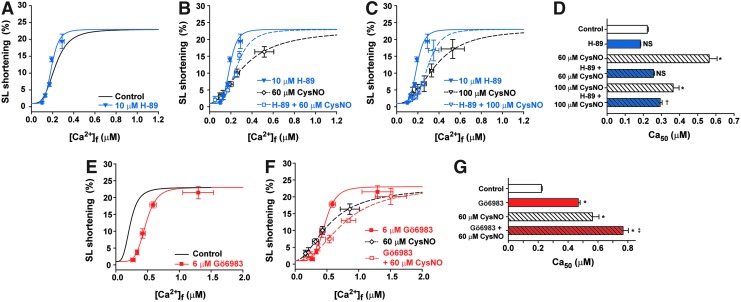

Ca2+ sensitivity and maximal force development in skinned fibers

To ascertain a direct effect of sarcomeric protein S-nitrosylation, Ca2+ sensitivity of force development and maximal isometric force were measured using permeabilized cardiac papillary muscle fiber bundles incubated with 1–100 μM GSNO (Fig. 4). Myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity was significantly decreased throughout this range of GSNO concentrations (Fig. 4A–C and E), while the maximum force development was decreased by ∼10% at ≥10 μM GSNO (Fig. 4D). Ca2+ sensitivity, but not maximal force, partially recovered after 30 min of incubation with 5 mM sodium ascorbate, a specific SNO-reducing agent (Fig. 4D, E) (19, 38). Interestingly, the extent of myofilament Ca2+ desensitization in skinned fibers (approximately −0.3 μM Ca2+) mirrored the extent of myofilament Ca2+ desensitization in intact cardiomyocytes (Fig. 2E).

FIG. 4.

Ca2+ sensitivity and maximal force (P0) are decreased by GSNO and Ca2+ sensitivity is partially restored by AA. (A–C) Skinned cardiac fibers were incubated with GSNO as indicated for 60 min, followed by tests for Ca2+ sensitivity and Po. After 30 min with sodium ascorbate, the measurements were repeated. (D) Maximal force was measured in 100 μM free Ca2+ before and after GSNO and ascorbate. (E) Ca2 + 50 ([Ca2+] for half-maximal force) from the experiments of (A–C). Mean ± SEM.; n = 4 for 1 μM GSNO, n = 7 for 10 μM GSNO, and n = 9 for 100 μM GSNO. *p < 0.05 versus control in the same data set. †p < 0.05 versus GSNO; one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison post-test. AA, ascorbate.

Rate of relaxation

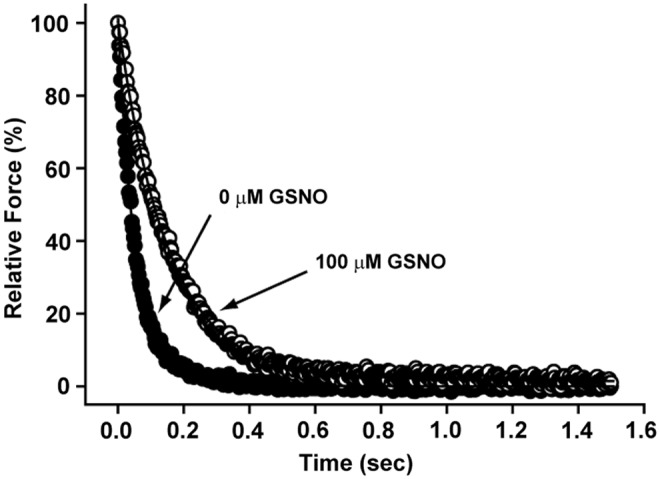

The rate of relaxation was measured in cardiac skinned fibers by photolysis of a caged Ca2+ chelator, diazo-2, with and without prior exposure to GSNO (see the Materials and Methods section). Compared with control, the major kinetic component of fiber relaxation (k1) was statistically slower in fibers preincubated with 100 μM GSNO, but not with 10 μM GSNO (Fig. 5 and Table 1).

FIG. 5.

GSNO slows the rate of relaxation in skinned fibers from cardiac muscle. Relaxation was recorded in skinned cardiac fibers after diazo-2 photolysis. Each trace is from a single experiment in which the fiber was treated with either 0 or 100 μM GSNO for 60 min. Complete data and the equation fit to the decay curve are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relaxation Rate Constants of Cardiac Skinned Fibers Incubated with GSNO

| Concentration of GSNO | A1 (%) | k1 (s−1) | A2 (%) | k2 (s−1) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 85.3 ± 2.0 | 15.3 ± 0.8 | 13.4 ± 2.2 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 13 |

| 0.01 mM | 87.0 ± 4.1 | 13.7 ± 1.1 | 10.2 ± 2.8 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 7 |

| 0.1 mM | 92.2 ± 2.3 | 11.7 ± 1.1a | 7.1 ± 1.8 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 10 |

Each bundle of cardiac skinned fibers was attached to a transducer and preincubated in the dark for 60 min in relaxing solution with the indicated concentration of GSNO, then activated with 2 mM diazo-2 and 0.5 mM CaCl2. At steady state, the bundle was raised into the air and exposed to a UV flash, liberating the Ca2+ chelator and causing relaxation. The time course y was fit with a double exponential y = A1e−k1t + A2e−k2t + C to obtain the amplitude (A) and rate constant (k) of each component. C is the resting (baseline) force. Values are average ± SEM of n preparations.

p < 0.05 compared with 0 GSNO (one-way ANOVA, Tukey's multiple comparison post-test.).

GSNO, S-nitrosoglutathione; SEM, standard error of the mean.

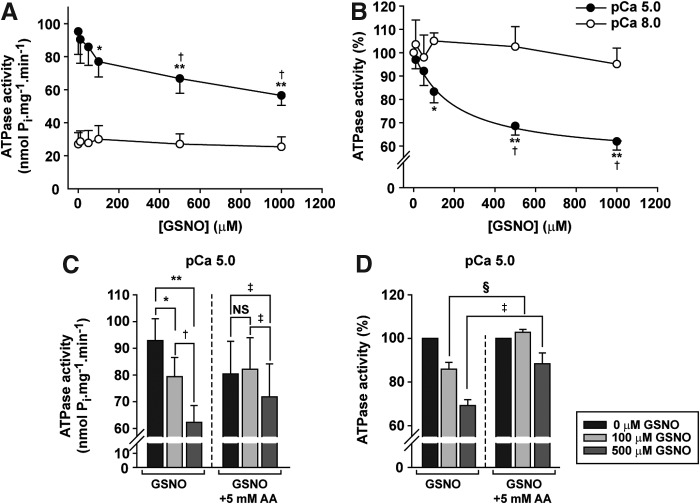

Cardiac myofibril Mg2+ ATPase activity

The effect of GSNO was evaluated by exposing CMFs to 0–1000 μM GSNO in pCa 5.0 (i.e., 10 μM free Ca2+) and pCa 8.0 (0.01 μM free Ca2+) buffers for 60 min. At concentrations ≥100 μM, GSNO inhibited the ATPase activity at pCa 5.0 by ∼20–40% (p < 0.05), while at pCa 8.0, the activity was unaffected by GSNO (Fig. 6A, B). Inhibition tended toward a plateau, with half-maximal inhibition at 195 μM GSNO. Subsequent treatment of myofibrils with 5 mM sodium ascorbate reversed the effect of GSNO on ATPase activity at pCa 5.0, evidence that the effects of GSNO were due to S-nitrosylation of myofibrillar proteins (Fig. 6C, D).

FIG. 6.

AA reverses the effect of GSNO on myofibrillar ATPase activity. (A, B) ATPase activity of CMFs after 60 min with 0–1000 μM GSNO in pCa 8 (0.01 μM free Ca2+) or pCa 5 (10 μM free Ca2+); n = 6. *p < 0.05 versus 0 μM GSNO; **p < 0.001 versus 0 μM GSNO; †p < 0.01 versus 100 μM GSNO; one-way ANOVA, repeated measures, Tukey's post-test. (C, D) ATPase activity of CMFs in pCa 5 after incubation with 0–500 μM GSNO, followed by 30 min with 5 mM AA. Note that data in (B, D) are normalized to 0 GSNO value for each data set. In (C): *p < 0.01 versus 0 μM GSNO; **p < 0.001 versus 0 μM GSNO; †p < 0.01 versus 100 μM GSNO; ‡p < 0.05 versus 0 μM and 100 μM GSNO +5 mM AA; NS, not statistically different; one-way ANOVA, repeated measures, Tukey's post-test. In (D): §p < 0.05 versus 100 μM GSNO; ‡p < 0.001 versus 500 μM GSNO; two-way ANOVA, repeated measures, Bonferroni post-test. Mean ± SEM; n = 6 for (A, B). In (C, D), n = 12 for GSNO and n = 6 for GSNO+AA.

Protein targets of CysNO in cardiomyocytes

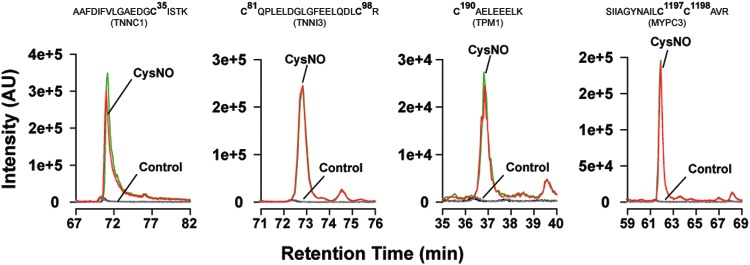

We next sought to identify targets of S-nitrosylation in live cells, with the identification of S-nitrosylated sarcomeric proteins as a primary goal. Following treatment of cardiomyocytes for 10 min with 50 μM CysNO, we coupled SNO-RAC with gel-free label-free mass spectrometry (MS) for the identification and relative quantification of targets of S-nitrosylation. As previously described, trypsinization on resin following SNO-RAC enrichment can be utilized to isolate peptides containing the sites of S-nitrosylation (SNO-sites) when the captured peptides are subsequently eluted (12, 15, 20, 57), but we have also recently proposed that the analysis of the peptides that are released by trypsinization (SNO-sup) can provide additional protein-level qualitative and quantitative information (52).

Figure 7 shows representative extracted ion chromatograms from duplicate runs in a single experiment for the SNO-sites of peptides from TNNC1, TNNI3, TPM1, and MYPC3 in the presence (50 μM) and absence (0 μM, control) of CysNO. In three independent experiments, we quantified SNO-sup peptides after SNO-RAC of lysates from CysNO- versus sham-treated cardiomyocytes. Each sample was analyzed by one-dimensional liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (1D-LC-MS/MS) in duplicate for improved quantitation, and ion mobility-assisted data-independent acquisition (HD-MSE) was employed for improved depth of coverage. Label-free quantitation based on area under the curve of identified peptides was performed after normalization to peptides derived from a yeast alcohol dehydrogenase internal standard, spiked in postdigestion.

FIG. 7.

Extracted ion chromatograms of cysteine-containing SNO-site peptides from selected sarcomere proteins. Intact cardiomyocytes were incubated with 0 or 50 μM CysNO, lysed, processed by SNO-RAC, and analyzed by 1D-LC-MS/MS (see the Materials and Methods section). Extracted ion chromatograms of selected peptides were visualized using Skyline (49). Superimposed traces show duplicate runs from a single experiment in which cells were treated or not with CysNO. Regions showing S-nitrosylated or control peptides from TNNC1, TNNI3, TPM1, and MYPC3 were selected for display. Cardiomyocytes treated with CysNO show a higher intensity compared with control. 1D-LC-MS/MS, one-dimensional liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Protein intensities were expressed as the aggregate sum of peptide intensities (45), and S-nitrosylated proteins were classified as those that had a >2-fold increase in the SNO-sup from CysNO- versus sham-treated cells. Proteins that were identified and quantified by two or more unique peptides were assigned higher confidence. The full set of quantitative peptide- and protein-level data for SNO-sup analysis (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars) and the full set of quantitative data for SNO-site data (Supplementary Table S4), including annotation of peptide and protein scores, are presented as Supplementary Data.

Across the three experiments, we quantified a total of 184 unique SNO-proteins (quantified by ≥2 peptides in at least one analysis and >2-fold vs. control; Supplementary Table S3). Of those, 29 proteins had a >2-fold increase in SNO-treated versus control cardiomyocytes in all three independent analyses, and an additional 69 proteins were S-nitrosylated in two of the three analyses (Supplementary Table S3).

Together, these two data sets included the sarcomeric proteins, actin (ACTC), myosin heavy chain (MYH6) and its essential light chain (MYL3), myosin-binding protein C (MYPC3), troponin C and I (TNNC1, TNNI3), α-actinin (ACTN2), and titin (TITIN), as well as two archetypal SNO-proteins, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2 (AT2A2) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3P). Tropomyosin (TPM1) appeared in one experiment and the Ca2+-handling protein, sarcalumenin (SRCA), appeared in all three. Phospholamban was also identified, but the aggregate peptide signal from this protein was not enhanced by CysNO treatment. Interestingly, a majority of other SNO-proteins quantified across all three groups had mitochondrial localization (Supplementary Table S3).

We also estimated the rank of abundance of each SNO-protein using the average intensity values from the three most intense peptides per protein (1, 58). The S-nitrosylated sarcomeric proteins, cardiac ACTC, MYL3, and MYH6, were among the most abundant proteins quantified by this method (not shown). The peptide-centric SNO-site data provided complementary localization of the sites of S-nitrosylation in most of the in situ S-nitrosylated sarcomeric proteins, including TNNC1, TNNI3, and MYL3 (Supplementary Table S4). Table 2 summarizes the proteomic data for selected sarcomeric cysteine targets in proteins from three independent experiments using 0 and 50 μM CysNO with cardiomyocytes. Two Ca2+-handling proteins (AT2A2, CASQ2) and one cytoplasmic protein (G3P) are included for comparison, showing SNO-sites that have been reported by other laboratories (30, 54).

Table 2.

Sarcomeric Proteins S-nitrosylated in Cardiomyocytes Exposed to CysNO

| Primary mouse protein | Modified peptide sequence | SNO-site | No. of expts | Ave. ratio (50/0) | SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin | |||||

| ACTC/ACTS/ACTA | CDIDIR | 287 | 2 | 2.7 | 2.2 |

| Myosin | |||||

| MYH6 | TECFVPDDKEEYVK | 37 | 3 | 3.2 | 0.7 |

| MYH6 | CIIPNER | 674 | 3 | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| MYH6 | CNGVLEGIR | 697 | 3 | 3.7 | 1.8 |

| MYH6 | HDCDLLR | 1342 | 3 | 1000a | — |

| MYH6 | LEDECSELKK, KLEDECSELKK | 949 | 2 | 1000a | — |

| MYL3 | ITYGQCGDVLR | 85 | 3 | 90.8 | 76.1 |

| MYL3 | LMAGQEDSNGCINYEAFVK | 191 | 2 | 3.8 | 1.2 |

| Troponin | |||||

| TNNC1 | AAFDIFVLGAEDGCISTK | 35 | 2 | 6.7 | 4.9 |

| TNNI3 | CQPLELDGLGFEELQDLCR | 81, 98 | 1 | 226 | — |

| Tropomyosin | |||||

| TPM1 | AELSEGKCAELEEELK, CAELEEELK | 190 | 3 | 16.5 | 11.9 |

| Myosin-binding protein C | |||||

| MYPC3 | LLCETEGR | 715 | 2 | 49.4 | 48.6 |

| MYPC3 | SIIAGYNAILCCAVR | 1197; 1198 | 2 | 27.4 | 16.8 |

| MYPC3 | KPCPYDGGVYVCR | 1240; 1249 | 2 | 19.8 | 16.0 |

| MYPC3 | ATNLQGEAQCECR | 1260; 1262 | 2 | 113.4 | 107.6 |

| Titin | |||||

| TITIN | FECVLTR | 13296 | 2 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| TITIN | YCVVVENSTGSR | 18679 | 2 | 3.6 | 3.3 |

| TITIN | YILTLENSCGK | 21561 | 2 | 12.8 | 12.5 |

| TITIN | DLPDLCYLAK | 21780 | 3 | 36.8 | 25.8 |

| TITIN | VTGLTEGCEYFFR | 22724 | 2 | 23.0 | 22.9 |

| TITIN | VDQLQEGCSYYFR, IDQLQEGCSYYFR | 24890 | 2 | 69.8 | 69.8 |

| TITIN | ACDALYPPGPPSNPK | 26786 | 2 | 3.3 | 3.1 |

| TITIN | DAGFYVVCAK | 32891 | 2 | 20.8 | 20.5 |

| TITIN | LTCAVESSALCAK | 34526, 34534 | 2 | 12.4 | 4.1 |

| Positive controls | |||||

| AT2A2 | SLPSVETLGCTSVICSDK | 344, 349 | 3 | 23.3 | 11.3 |

| AT2A2 | VGEATETALTCLVEK | 447 | 3 | 10.7 | 2.5 |

| CASQ2 | (R)YDLLCLYYHEPVSSDK | 53 | 2 | 12.6 | 9.1 |

| G3P | IVSNASCTTNCLAPLAK | 150, 154 | 3 | 50.5 | 43.4 |

| G3P | VPTPNVSVVDLTCRLEKPAK | 245 | 2 | 84.5 | 72.1 |

Ratios are for duplicate signals from the number of experiments in column 4. Myocytes were exposed to 0 or 50 μM CysNO. Italics in column 2 indicate oxidized M or deamidated N or Q. In each experiment, signals from multiple peptides with the same Cys residue were averaged. In peptides with more than 1 Cys, the SNO-site residue could not be assigned. This does not affect the ratios in column 5. For complete list of peptides, ion scores, and other data, see Supplementary Table S4.

Capped at 1000.

ACTC/ACTS/ACTA, UniProt accession numbers P68033/P68134/P62737, cardiac/skeletal/aortic smooth muscle actin; C, cysteine residues; MYH6/Q02566, α-myosin heavy chain; MYL3/P09542, myosin essential light chain 3 (ventricular); TNNC1/P19123, slow troponin C; TNNI3/P48787, troponin I; TPM1/P58771, α-tropomyosin; MYPC3/O70468, myosin-binding protein C; AT2A2/O55143, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca ATPase 2; CASQ2/O09161, calsequestrin 2; G3P/P16858, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; CysNO, S-nitrosocysteine; SNO, S-nitrosothiol.

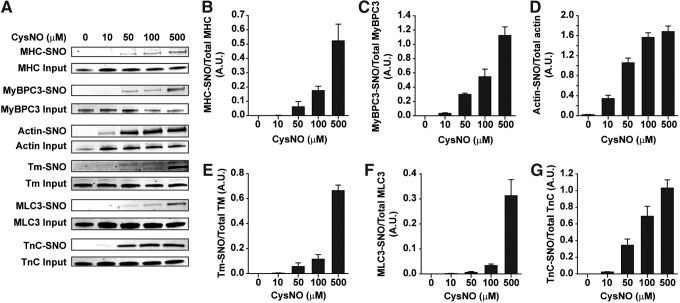

The concentration dependence for S-nitrosylation of sarcomeric proteins by extracellular CysNO is unknown. We investigated this question in isolated cardiomyocytes by SNO-RAC and Western blots after treatment with 10–500 μM CysNO (Fig. 8A). Supraphysiological concentrations were included to ensure at least one robust signal from the nitrosylated cysteines. Within 10 min, four of the six sarcomeric proteins tested exhibited clear signals at 100 and 500 μM CysNO; for two of the six proteins (Tm and MLC3), the -SNO signals were much weaker below 500 μM (Fig. 8B–G).

FIG. 8.

Sarcomeric proteins are targets for S-nitrosylation in isolated cardiomyocytes. After 10 min with 0–500 μM CysNO, cells were lysed and the SNO-RAC protocol was performed. Proteins were detected by immunoblotting with protein-specific antibodies in (A). (B–G) Densitometry of the bands for each of the proteins in (A). Signals for each blot were normalized to the total for that specific protein from the corresponding SDS-PAGE gel. Mean ± SEM, n = 6.

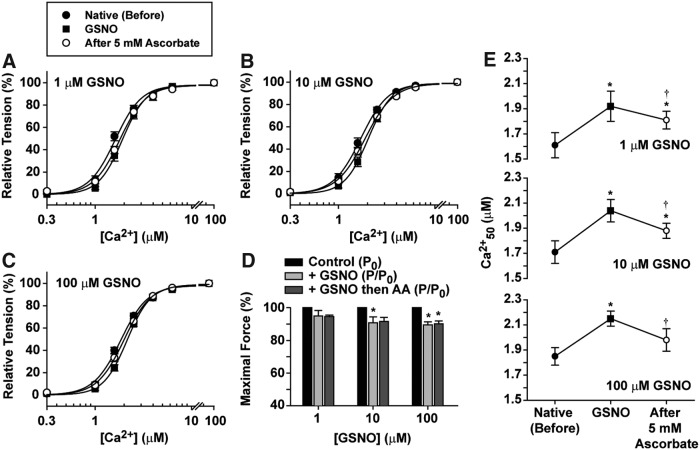

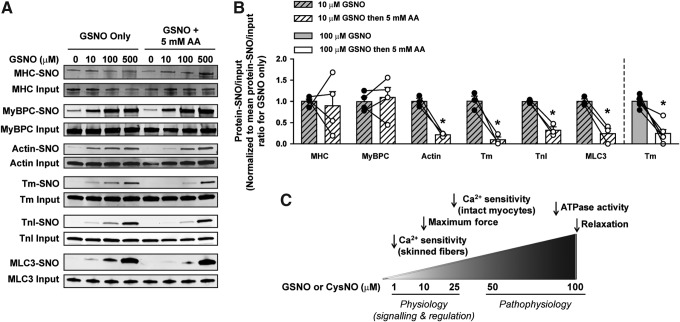

Reversal of sarcomeric protein S-nitrosylation in myofibrils

Since some of the functional assays were performed in demembranated fibers using GSNO, we next examined the S-nitrosylation by GSNO to identify affected sarcomeric proteins in isolated myofibrils. Isolated CMFs were incubated for 60 min with 0–500 μM GSNO, and there was a dose-dependent S-nitrosylation of all sarcomeric proteins of interest (Fig. 9A). Despite the clear-cut reversibility of GSNO effects on Ca2+ sensitivity and ATPase assays with this demembranated preparation (Figs. 4 and 6), the loss of SNO signal on immunoblots when sodium ascorbate was added after GSNO treatment was very heterogeneous for most proteins, except tropomyosin (Fig. 9A). This variability was evident when CMFs were treated with 100 and 500 μM GSNO (data not shown). However, for actin, Tm, TnI, and MLC3, sodium ascorbate significantly reversed S-nitrosylation after 10 μM GSNO (Fig. 9B). Therefore, the reversibility of protein S-nitrosylation occurred primarily at the lowest GSNO concentration tested.

FIG. 9.

CMF protein S-nitrosylation by GSNO is reversed by AA primarily at 10 μM GSNO. After incubation with 0–500 μM GSNO for 60 min, CMFs were homogenized and half of the samples were treated with 5 mM AA for 30 min. After SNO-RAC on all samples, specific proteins were detected by immunoblotting (A) and quantified by densitometry (data not shown). (B) Changes in band density due to 5 mM ascorbate treatment for each protein after CMFs were incubated with 10 μM GSNO (shown for all proteins) or 100 μM GSNO (shown only for Tm), followed by the SNO-RAC procedure. Data are shown as the mean ratio of protein-SNO to input for each protein, normalized to the value for GSNO only. Mean ± SEM, n = 3–4 (for 10 μM GSNO) and n = 6 (for 100 μM GSNO); *p < 0.05 versus control; paired Student's t-test. (C) Schematic of the NO effects on the contractile properties of the myofilament. NO, nitric oxide.

A final calculation aimed at evaluating susceptibility of sarcomeric cysteines toward low-molecular-weight S-nitrosothiols was performed by comparing immunoblot data from the dose–response curves at 500 and 50 μM GSNO (last column, Table 3) using an approach described by Weerapana et al. (59) and Su et al. (54). In this approach, a two-point assay for reactivity is described. Identical samples of protein are exposed to two concentrations of the nitrosylating agent for the same length of time. For a concentration ratio of 10:1, one expects a response ratio of 10:1 if the response merely increases linearly from 50 to 500 μM of the nitrosylating agent. More reactive cysteine sites provide a stronger signal at the lower concentration and thus a lower ratio following exposure to 500/50 μM for the same length of time. Thus, a ratio of 2 means that the site is five times more reactive to nitrosylation than expected on the basis of a linear increase with concentration.

Table 3.

Reactivity Profiles for Protein S-nitrosylation by CysNO and GSNO

| Signal ratio, 500 μM/50 μM | ||

|---|---|---|

| Protein | ImmunoblotaCysNO (cells) | ImmunoblotbGSNO (CMFs) |

| Actin | 1.6 | 3.0 |

| MHC | 8.5 | 3.2 |

| MLC3 | 52.0 | 5.8 |

| TnC | 3.0 | n.d. |

| TnI | n.d. | 5.0 |

| Tm | 11.7 | 4.2 |

| MyBPC | 3.8 | 3.0 |

Cardiomyocytes were treated for 10 min with CysNO.

Myofibrils (CMFs) were treated for 60 min with GSNO. Both sets of proteins were analyzed by Western blot with protein-specific antibodies, following SNO-RAC (Figs. 8 and 9).

CMFs, cardiac myofibril; n.d., not detected; SNO-RAC, resin-assisted capture of S-nitrosothiols.

For all six of the proteins that could be identified consistently (TnC had a very poor immunoblot signal in these experiments), the ratio was well below 10 (3.0–5.8). On this basis, the reactivity profile to GSNO was fairly similar among the different sarcomere proteins.

Interestingly, the ratios for signals from 500 to 50 μM of the S-nitrosylating agent were more variable in the experiments with CysNO (Table 3), ranging from 2 to 4 for three of the proteins, but with much higher values for two of them. The much lower sensitivity indicated by high ratios for MLC3 (52.0) and Tm (11.7) occurred only with intact cells (see the Discussion section). This observation provides both qualitative and quantitative evidence for specificity in the protein S-nitrosylation response since only a few of the available cysteine sites are significantly affected by the CysNO-induced S-nitrosylation.

Discussion

In this study, we report for the first time that S-nitrosylation of cardiac sarcomeric proteins by low-molecular-weight S-nitrosothiols, GSNO and/or CysNO, depresses myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, maximum force development, myofibrillar ATPase activity, and rate of relaxation in intact and skinned cardiac muscle preparations. GSNO and CysNO differ: GSNO does not readily cross cell membranes, but it does act directly on the proteins of demembranated myofibrils. CysNO, on the other hand, can cross cell membranes to release NO or promote transnitrosylation with natural cytoplasmic components, including protein thiols and glutathione (7).

We first measured the myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity using intact cardiomyocytes incubated with CysNO. In this case, the intracellular concentration of CysNO is limited by the l-amino acid transporter in the sarcolemma, with a Km for cysteine of ∼200 μM (29); inside the cell, it can transfer its nitroso group to proteins or to the ample supply of endogenous glutathione to form GSNO.

The concentration of GSNO in cardiomyocytes has not been measured, but can be estimated at 1–30 μM based on recorded Km values for GSNO reductase (Km 5 μM in humans, 7 μM in bovines, 20 μM in mice) and carbonyl reductase 1 (Km 30 μM in humans), two enzymes that are important for GSNO metabolism (8, 36, 48, 53). These values are consistent with a direct estimate of 2.7 μM for the NO concentration near the endocardium in a beating heart (7, 44). Thus, we obtained a significant response at a physiologically relevant concentration only for myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and maximum force, while ATPase activity and relaxation responded to higher, more pharmacologically (or pathophysiologically) relevant concentrations. As shown previously in vitro (41), longer exposures to low concentrations can increase the level of SNO, so the possibility remains open that effective concentrations are even lower in living cells.

S-nitrosylation of proteins from cardiac muscle cells has been studied extensively with respect to cardioprotection, where a conditioning stimulus or an S-nitrosylating agent such as CysNO, GSNO, or S-nitroso-N-acetyl-d,l-penicillamine is used before or during an ischemia/reperfusion challenge. As a result of the induced increase in protein S-nitrosylation, infarct size is reduced and recovery of contractility is more complete than without these pretreatments (25, 57). Although these studies detected primarily mitochondrial and other membrane-bound proteins, they also reported S-nitrosylation of myosin heavy chain, actin, myomesin, creatine kinase, myosin-binding protein C, and titin. Functional assays were confined to metabolic enzymes and calcium-handling systems (55).

Beigi et al. (6) have explored the role of S-nitrosylation in intact cardiomyocytes in which R-SNO is enhanced due to lack of the denitrosylase, GSNO reductase (GSNOR). In response to isoproterenol, when the intracellular levels of NO are increased, the extent of sarcomere shortening is depressed in GSNOR−/− mice compared with wild-type mice, which corroborates our findings for the rate of relaxation and myofibrillar ATPase when S-nitrosylation is enhanced.

In this study, we have focused our attention on sarcomeric proteins, asking how S-nitrosylation itself might affect contraction. We propose that physiological levels of NO can fine-tune the myofilament by relatively modest effects on the Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction and maximal force development in skinned fibers. Furthermore, in this case, low levels of protein S-nitrosylation can be protective against the deleterious effects of irreversible protein oxidation, which can occur during acute events of ischemia–reperfusion (32, 55). However, at supraphysiological concentrations, for example, during sepsis (51), NO may cause an overload of protein S-nitrosylation that substantially inhibits cardiac contractile properties (Fig. 9C). In this case, the decrease in sensitivity to Ca2+ could protect the heart mechanically at the onset of an episode of oxidative/nitrosative stress, but if the situation deteriorated into sepsis, a lower Ca2+ sensitivity might contribute instead to a downhill spiral. Only in the second case would there be an advantage to reducing S-nitrosylation of sarcomeric proteins.

Myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity

The earliest sign of a significant physiological effect of S-nitrosylation in our experiments appeared as a reduction in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity at near-physiological concentrations of GSNO and CysNO (Figs. 2 and 4). The changes in sensitivity were small, but even such small shifts can have a significant physiological impact (2). At higher concentrations, there was no greater effect, indicating saturation near 1 and 25 μM, respectively. A potential limitation to any inference regarding physiological significance arises where S-nitrosylation at the lowest effective concentration of GSNO cannot be distinguished from the baseline level of protein-SNO in immunoblots (Fig. 9).

Other aspects of contractile activity that we measured, for example, rate of relaxation and ATPase activity, were altered at higher GSNO concentrations, where increased S-nitrosylation of individual sarcomeric proteins can be confirmed directly (Fig. 9). These effects are considered within the context of the identified SNO-sites and their possible functional impact, as discussed below.

Troponin C, the main Ca2+ trigger of the thin filament, is a strong candidate for mediating changes in Ca2+ sensitivity, and Cys35 is an SNO-site (Table 2). It is located within the Ca2+-binding loop of defunct Ca2+ site I, where it lies in the middle of a short ß-sheet that is connected to Ca2+ site II via hydrogen bonds. Notably, this region has been identified as critical for conformational changes involved in Ca2+ binding (23). A limitation of our method is the requirement for Cys residues to be located in suitable tryptic peptides, and although Cys84 is relatively more exposed (24), the predicted tryptic peptide it would form during MS analysis (CysMetLys) is only a 3-mer and would likely not be detected.

MyBPC3 also regulates Ca2+ sensitivity of myofilaments, and phosphorylation of sites in the N-domain has this effect (26). MyBPC binds to myosin, actin, and titin and acts as a brake on myosin cross-bridges, affecting force development as well as the kinetics of contraction and myofibrillar relaxation (13, 47). NOS dependence of Ca2+ sensitivity under MyBPC control may mean that the response to phosphorylation, or phosphorylation itself, is modulated by S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues. S-nitrosylation per se has not been explored in physiological experiments, but there is a cluster of MyBPC SNO-sites (Cys1197/98, Cys1240/49, and Cys1260/62, Table 2) in C-terminal regions where binding sites for myosin, titin, and possibly a specific site for actin are found (13).

Myofibrillar ATPase activity

Exposure of myofibrils to GSNO at higher concentrations caused marked inhibition of the ATPase activity, similar to that observed previously with S-nitrosylated skeletal myosin (41, 61). S-nitrosylation of myosin may account for these effects in CMFs as well since five SNO-sites were identified in the myosin heavy chain (MYH6) and two were identified in the essential light chain (MYL3), which is bound to the neck of MYH6 (Table 2). Previously, we reported that inhibition of skeletal myosin by S-nitrosylation is associated with a small population of four to six cysteines that are readily accessible to thiol reagents and may lie on or near the surface (41).

MLC3 has two cysteines, both of them S-nitrosylated in cardiomyocytes (Table 2). These residues sit on the same side of the myosin neck, or lever arm, which is directly linked to the catalytic site by a long α-helix. Cys191 and its homolog in skeletal myosin are rapidly reacting cysteines that cause loss of catalytic activity on reaction with a purine affinity label. Thus, a small number of SNO-sites on myosin heavy chain and its essential light chain (Cys191) can be considered likely sources for the inhibitory effects on the ATPase activity seen in S-nitrosylated CMFs.

In principle, myofilament force and ATPase activity can also be reduced by modifications in actin. Three of actin's six cysteines are S-nitrosylated in vitro (54); however, we found Cys-SNO only at residue 287, which does not appear to be involved in interactions with myosin (42).

Rate of myofibrillar relaxation

Major determinants for the relaxation rate under our conditions include Ca2+ dissociation from TnC, detachment of cross-bridges, and adjustments of the regulatory complex on the thin filament (62). TnI and Tm are key players in the thin-filament response and either protein can dominate the relaxation rate, depending on experimental conditions and the specific mutations involved (35, 62).

Cys190 of Tm, located in one of its two troponin-T binding sites, is conserved as the sole cysteine in the α isoform that predominates in mouse heart. Cys190 was S-nitrosylated in our experiments, and the same modification is found in left ventricles of failing human hearts (11). This cysteine is thus an interesting candidate for slowing the relaxation rate. Cys190 is an essential element in the homodimer, but further experiments will be needed to confirm whether S-nitrosylation at this site has a functional effect.

New evidence for regulatory tasks of cardiac MyBPC suggests a role for this protein in relaxation: mouse hearts and trabeculae with a defective MyBPC relax more slowly. The possibility that a slower relaxation rate reflects changes in the C-domain, where there is a cluster of reactive cysteines (residues Cys1197–1262, Table 2), is reinforced by evidence that there is an effective actin-binding site in this region (46).

Reactivity profiles

Even excluding titin, which has hundreds of cysteines, a tally of identified SNO-sites in Table 2 (23 sites of 66 cysteines) shows that S-nitrosylation in cardiac sarcomeric proteins is a selective event. There is no consensus on the basis for selectivity among cysteine thiols (7). One of our goals was to assess the susceptibility of S-NO targets among the sarcomeric proteins. We did not attempt a kinetic study, but in a situation similar to that used for functional assays, immunoblots were collected after exposure of myofibrils to a 10-fold spread of GSNO concentrations. These values extend well above the physiological range, and indeed we emphasize that the rationale was not to simulate a physiological situation, but to define a reactivity profile, related to the slope of the dose–response curve for S-nitrosylation of these proteins (54, 59). The signal ratio for 500 to 50 μM GSNO varied from 3.0 to 5.8 for the six proteins identified at both of these concentrations (Table 3, last column).

Higher ratios appeared in the assay with intact cardiomyocytes exposed to CysNO for 10 min. Ratios were 1.6 to 3.8 for actin, TnC, and MyBPC, but 12 and 52 for Tm and myosin MLC3, suggesting a lower reactivity for these two proteins. Besides the shorter exposure time in this experiment, there was an intact sarcolemma; CysNO can only cross this barrier by active transport (25). Half-maximal intracellular effects achieved when CysNO is added to the medium require between 20 and 180 μM for different cells from the aorta (8, 33). Thus, the lower sensitivity in our immunoblots for MLC3 and Tm may reflect a kinetic limitation; CysNO had only 10 min to cross the cell membrane and react with thiols rather than the 60 min allotted for GSNO in demembranated myofibrils. In addition, there are many more proteins competing for the CysNO in the cytosol of cardiomyocytes than in isolated myofibrils and some of them (e.g., GSNO reductase) are capable of interfering with the reaction.

Conclusions

Since ascorbate did produce substantial reversal of functional effects (Figs. 4 and 6), the heterogeneity in reversibility of S-nitrosylation on blots may be a consequence of proteins having some SNO-sites that are more stable than others, as we have observed for skeletal myosin (41). Such a signal could mask removal of SNO from any single site in proteins that are polynitrosylated, such as MHC and MyBPC (Table 2).

Collectively, S-nitrosylation of a small number of the many thiols available in sarcomere proteins depressed the contractile activity of cardiac myofilaments. S-nitrosylated sites were identified in the individual polypeptide chains of MHC (5), MLC3 (2), actin (1), Tm (1), TnC (1), TnI (1), MyBPC (4), and titin (9). In both intact and permeabilized preparations, the results support a physiological significance of S-nitrosylation in desensitizing the myofilaments to Ca2+ and possibly also in decreasing the maximal force. At higher concentrations of GSNO, effects extend to the rate of relaxation and cross-bridge turnover and should be relevant for pathophysiological effects.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experiments followed institutional guidelines and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Miami, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, and Florida State University in compliance with NIH standards. The experiments were conducted in adult mice (3–7 months old), C57BL/6 or C57BL/6+SV129.

Reagents

Reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted, including HEPES [4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid], TES [2-[[1,3-dihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)propan-2-yl]amino]ethanesulfonic acid], EGTA, [ethylene glycol-bis (2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid], MOPS [3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid], EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid), neocuproine, Triton X-100, the detergent IGEPAL CA-630 (octylphenoxypolyethoxyethanol), MMTS (S-methyl methane thiosulfonate), GSH (reduced glutathione), l-cysteine, DTT (dithiothreitol), AA (sodium ascorbate), BDM (2,3-butanedione monoxime), PMSF (phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride), H-89 [N-[2-(bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-isoquinoline sulfonamide], and taurine.

Bicinchoninic acid Protein Assay Reagent kit (#23236) was from Thermo Scientific Pierce (Rockford, IL). Thiopropyl sepharose 6B (TPS) was from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Pittsburgh, PA). Diazo-2 [glycine, N-[2-[2-[2-[bis (carboxymethyl) amino]-5-(diazoacetyl) phenoxy]ethoxy]-4-methylphenyl]-N-(carboxymethyl)-, tetrapotassium salt] was from Invitrogen (Grand Island, NY). Gö6983 [3-[1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-5-methoxyindol-3-yl]-4-(1H-indol-3-yl)pyrrole-2,5-dione] was from Cayman Biochemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Synthesis of S-nitrosothiols, GSNO and CysNO, was carried out immediately before each experiment by mixing glutathione or cysteine (acidified with 0.1 M HCl) with an equimolar concentration of NaNO2 (41).

Detection of protein S-nitrosylation during acute endotoxemia in mice

Endotoxemia was induced in C57BL/6J mice (Anilab Animais de Laboratório; Brazil) by a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 10 mg/kg of body weight of LPS from Escherichia coli (055:B5, n=3 mice; Sigma-Aldrich). Control mice (n=3) were treated (i.p.) with vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]: 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.0). Each mouse was anesthetized 12 h after the injection with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine and euthanized by cervical dislocation. After thoracotomy, excess blood was removed from the heart by inserting a catheter into the right ventricle and perfusing the heart with PBS supplemented with 10 mM N-ethylmaleimide and 2.5 mM EDTA (17). After perfusion, the heart was removed and frozen in liquid N2.

Each heart was pulverized in N2 and the resulting powder was homogenized at 1 ml/100 mg tissue, on ice, in HEN (100 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM neocuproine) made up in lysing buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1.0% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS), followed by centrifugation (10,000 g, 4°C, 10 min). The supernatant was used for the SNO-RAC technique (as described below). The S-nitrosylated proteins were detected and identified by immunoblotting.

SDS-gel electrophoresis, silver staining, and immunoblotting

To assess the sarcomeric protein targets for S-nitrosylation, input and TPS-eluted protein samples were mixed with Laemmli buffer and boiled for 2 min before loading onto the gels. In Figure 1A and B, proteins were separated on a 12% SDS polyacrylamide gel and silver stained. For immunoblot analyses, samples were electrophoresed on 4–15% precast SDS-PAGE gels (Criterion; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for Western blots (RPN303D; GE Healthcare, Marlborough, MA) for 1 h in Tris-glycine buffer, blocked for 1 h with LI-COR Odyssey blocking buffer (927–40000), and incubated overnight with the primary antibodies in the same buffer.

Specific antibodies were used to detect myosin-binding protein C (K16, 1:1000, sc-50115; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), myosin heavy chain (MF20, 1:1000; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA), actin (alpha sr-1, ab-28052, 1:2000; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), tropomyosin (CH1, 1:4000, T9283; Sigma-Aldrich), troponin I (H170, 1:1000, sc-15368; Santa Cruz), troponin C (7B9, 1:200, sc-52265; Santa Cruz), and cardiac (ventricular) myosin light chain 3 (MLM527, 1:1000, sc-58804; Santa Cruz). After primary antibody incubation, blots were washed with TBS with 0.05% Tween 20, placed in covered boxes for 1 h, and incubated with secondary fluorescent antibody.

The specific primary antibodies were detected using 1:10,000 IRDye 800CW donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibody (LI-COR 962–32213; LICOR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE), 1:20,000 IRDye 680RD donkey anti-mouse IgG antibody (926–68072; LI-COR), and 1:20,000 IRDye 680RD donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (926–68074; LI-COR) in LI-COR Odyssey blocking buffer. Reactions were quantified by scanning the blots with the Odyssey Infrared Imager (LI-COR), and the band intensities were analyzed using ImageJ 1.46 software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Cardiomyocyte isolation

Cardiomyocytes were isolated after perfusion of hearts from adult mice for 10–15 min with bicarbonate buffer without Ca2+ (in mM, 120 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.2 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 5.6 glucose, 20 BDM, and 5 taurine), previously gassed with 95% O2/5% CO2, followed by enzymatic digestion with collagenase type II (1 mg/ml; Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ) and protease type XIV (0.1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) (6). Cardiomyocytes were then separated by mechanical disruption, filtered, centrifuged, and resuspended at pH 7.4 in calcium-free Tyrode's buffer (in mM, 144 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 5.6 glucose, and 5 KCl). Myocytes were incubated with successively higher concentrations of CaCl2 in Tyrode's solution over a period of 45 min at room temperature until 1.8 mM CaCl2 was reached. Incubation with CysNO was carried out at room temperature in this same solution.

Assessment of myofilament response to Ca2+ in intact cardiomyocytes

Isolated cardiomyocytes from mice (N=4–5) were loaded with the membrane-permeable Ca2+-sensitive dye, Fura-2-AM (Molecular Probes, Grand Island, NY), for 15 min at room temperature as described in (16). SL was recorded with an IonOptix iCCD camera. Ca2+i was measured by dual excitation (340/380 nm) and Fura-2 fluorescence acquired at 510 nm on an IonOptix spectrofluorometer (IonOptix LLC, Milton, MA). The in vivo calibration was performed using solutions containing 10 μM ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) (16). Changes in myofilament responsiveness to Ca2+ were assessed by acquiring pairwise measurements of SL and [Ca2+]i in intact single cardiomyocytes tetanized by high-frequency (10 Hz) stimulation after disabling the reuptake of Ca2+ to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) by using thapsigargin (0.2 μM; Sigma-Aldrich) (16).

High-frequency electrical stimulation after thapsigargin treatment results in the summation of the repetitive transmembrane flux of Ca2+ mainly through L-type Ca2+ channels to achieve a steady-state level of cytosolic Ca2+ substantially elevated above resting levels at the point where Ca2+ influx is balanced by the rate of Ca2+ extrusion (only via Na+/Ca2+ exchange because of the absence of SR Ca2+ sequestration). With this approach, the Ca2+i was reversibly clamped near peak systolic levels during the tetanic contracture for 20 s (or longer), and then rapidly returned to resting levels on cessation of electrical stimulation. The steady-state levels of Ca2+ achieved during tetanization were systematically regulated by bathing cardiomyocytes with Tyrode's buffer made with increasing concentrations of Ca2+ (0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0, and 10 mM CaCl2) to effectively gauge changes in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity.

Experiments were performed after incubating the cells for 10 min at room temperature in the absence or presence of CysNO (1, 10, 25, 60, 100 μM, or 1 mM). To test for a possible PKA- or PKC-dependent effect of CysNO in the intact cardiomyocytes, we also assessed myofilament responsiveness to Ca2+ in the presence and absence of the PKA inhibitor, H-89 (10 μM), and PKC inhibitor, Gö6983 (6 μM), alone or combined with either 60 or 100 μM CysNO. Cardiomyocytes were incubated with the protein kinase inhibitor for 15 min before CysNO incubation. An average of three cells per mouse heart were tested in each condition.

The SL responses at different [Ca2+]i levels were analyzed by fitting the data with the following sigmoid equation: % Change in SL=SL0 + [(SLmax*[Ca2+]in)/(Ca50 + [Ca2+]in)], where Ca50 is the [Ca2+]i that produces 50% change in SL and n is the Hill coefficient. To determine myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity and compare with different CysNO treatments (as shown in Figs. 2 and 3), SL0, which is the % change in SL at 0 μM [Ca2+]i, was fixed as 1%, and SLmax, which is the maximal % change in SL, was fixed as 22%.

Skinned fibers: Ca2+ sensitivity, maximum force, and rate of relaxation

Skinned papillary muscles were prepared from the left ventricles of adult mice. Small bundles of fibers were isolated and treated overnight with a pCa 8.0 relaxing solution (10−8 M [Ca2+]free, 1 mM [Mg2+]free, 7 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM MgATP2−, 20 mM MOPS [pH 7.0], 20 mM creatine phosphate, and 15 U/ml creatine phosphokinase, I=150 mM) containing 1% Triton X-100 and including 50% glycerol at −20°C. Fibers were then transferred to a similar solution without Triton X-100 and kept for up to a week at −20°C (5). Ca2+ sensitivity and maximum force were measured in bundles of 75–125 diameter μm separated by microdissection in relaxing solution at pCa 8.0 and attached to tweezer clips connected to a force transducer. The fibers were treated with relaxing solution containing 1% Triton X-100 for 30 min to ensure complete membrane removal and allow better access to the myofilament proteins. After extensive washing with pCa 8.0 without Triton X-100, the initial maximal force was determined by transferring the fibers into pCa 4.0 solution (identical to pCa 8.0 solution, except that [Ca2+]free was 10−4 M) and then back to pCa 8.0.

To determine the Ca2+ sensitivity of force development, the fibers were exposed stepwise to solutions of increasing Ca2+ concentration from pCa 8.0 to 4.5 based on the program pCa Calculator (5). Data were analyzed using the following equation: % Change in force=100*[Ca2+]n/([Ca2+]n + [Ca2+50]n), where [Ca2+50] is the free [Ca2+] that produces 50% force and n is the Hill coefficient. After the measurements of maximum force and Ca2+ sensitivity, fibers were incubated with GSNO for 60 min in relaxing solution pCa 8.0, and a second maximal force and pCa curve were measured. Then, fibers were incubated with 5 mM sodium ascorbate for 30 min, followed by a third maximal force and pCa curve. All experiments were performed at room temperature and in the dark, as required, to avoid light-induced ascorbate reduction and photolysis of –SNO-sites.

Relaxation rates were measured as previously described (37). A bundle of cardiac skinned fibers was attached to a force transducer as described above and incubated with a solution containing, in mM, 2 diazo-2, 0.5 CaCl2, 60 TES, pH 7.0, 5 MgATP2−, 1 free Mg2+, and 10 creatine phosphate, plus 15 U/ml creatine phosphokinase. The ionic strength was adjusted to 0.2 M by adding K propionate. At the indicated ratio of total added Ca2+ to diazo-2, the force developed to about 80% of the initial maximal force measured at pCa 4.0 (10−4 M [Ca2+]i). This ratio provided the greatest extent of relaxation after photolysis of the diazo-2. When force reached a steady value, the cuvette was moved aside; the fiber (in air) was then exposed to a UV flash (30 mJ over 1 ms) from a xenon lamp beam passing through a UG11 cutoff filter. The photolysis-induced relaxation was measured only once per fiber.

The force transients were recorded in milliseconds and fit with a double exponential decay equation with four parameters. The protocol used after GSNO incubation was the same, with the rate of relaxation measured in a separate fiber for each concentration.

CMFs: ATPase activity

CMFs were prepared from ventricular muscles of adult mice by a modification of (27) as follows: hearts were excised and immediately washed with 0.9% NaCl at 4°C. The muscle was cut into small pieces and processed two to three times for ∼5 s in a Sorvall Omnimixer using two volumes of 0.3 M sucrose containing, in mM, 10 imidazole pH 7.0, 1 DTT, 1 PMSF, and stock protease inhibitor cocktail for mammalian cells (Cat No. P8340; Sigma-Aldrich). After 2 more minutes on ice, the CMF suspension was centrifuged at 1500 g for 2 min. The centrifugation step was repeated once more with the pellet resuspended to the original homogenate volume in 0.3 M sucrose solution. Then, the pellet was resuspended in standard CMF solution (in mM, 30 imidazole pH 7.0, 60 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 1 PMSF, and stock protease inhibitor cocktail) containing 2% EGTA. The homogenate was again centrifuged at 1500 g for 4 min, and the pellet resuspended in ∼4 pellet volumes in the standard CMF solution containing 1% Triton X-100. This step was repeated two more times.

Each Triton X-100 step consisted of 30 min of incubation on ice, followed by 4 min of centrifugation at 1500 g. Finally, CMFs were washed four times in standard CMF solution to remove the Triton X-100 (each wash consisted of resuspending the pellet in ∼4 pellet volumes, followed by 4 min of centrifugation at 1500 g). The first wash included 25% glycerol and subsequent washes had 50% glycerol. The homogenate obtained after this series of steps, termed washed CMFs, was light brown in color and was stored at −20°C. Incubations with and without GSNO for the experiments of Figure 6 and Western blot analyses were carried out at pCa 8.0 (10−8 M [Ca2+]free, 1 mM [Mg2+]free, 7 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM MgATP2−, 20 mM MOPS [pH 7.0], and I=150 mM adjusted with K propionate) without an ATP-regenerating system, at room temperature and in the dark.

For measurements of ATPase activity, CMFs were washed thrice with 13 volumes of H2O and resuspended in either pCa 8.0 or pCa 5.0 (10−5 M [Ca2+]free) without ATP or the ATP-regenerating system, at 4°C. The protein concentration was measured with the Coomassie Plus (Bradford) Protein Assay (Cat No. 23236; Thermo Scientific Pierce) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. CMF concentration was adjusted to 0.1 mg/ml for activity. The reaction, carried out in 96-well plates and initiated by addition of ATP, was terminated by adding trichloroacetic acid always in the dark. The plates were centrifuged at 1700 g for 30 min and the supernatant was then incubated with ferrous molybdate for measuring inorganic phosphate (41). Phosphate was read at 700 nm on a microplate reader and compared with a standard curve. CMFs were incubated with 0–1 mM GSNO for 60 min before ATP addition.

To measure the reversibility of protein S-nitrosylation, CMFs were first incubated for 60 min with GSNO and then 30 min with sodium ascorbate before ATP addition. The incubations and ATPase experiments were carried out at 25°C.

Resin-assisted capture of S-nitrosothiols

The SNO-RAC method (20) was used for capture of S-nitrosylated proteins from cardiomyocytes or CMFs, with the following modifications. Cardiomyocytes (one heart yielded four samples) or CMFs (1 mg/ml) were incubated at room temperature (21°C) with CysNO or GSNO, respectively, for 10 min (Fig. 7, Table 2) or the times indicated in the legends to Figures. 1, 8, and 9. Then, cardiomyocytes were lysed with RIPA buffer/HEN (100 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01 mM neocuproine, 1 mM EDTA, 1.0% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) to solubilize the proteins (this step was omitted for CMFs, which were solubilized with blocking buffer, as shown below). The protein concentration was measured with the Coomassie Plus (Bradford) Protein Assay, as described above. Cardiomyocyte lysate concentration was adjusted to 1 mg/ml.

Both cardiomyocytes and CMF homogenates were incubated with blocking buffer (HEN plus 50 mM MMTS and 2.5% SDS) at 50°C for 40 min with frequent vortexing. After addition of four volumes of cold acetone, the mixture was allowed to precipitate for 20 min at −20°C, followed by centrifugation at 3000 g for 10 min. The pellet was washed thrice in 70% acetone, resuspended in HEN/1%SDS containing 20–200 mM sodium ascorbate, and the mixture was incubated with 25–50 μl of TPS for 3 h at room temperature. Following protein capture, beads were washed with HEN/1%SDS and centrifuged for 6 s at ∼700 g. This step was repeated four times and then three more times with HEN diluted 10-fold plus 1% SDS (HEN/10SDS). All steps were performed in the dark to minimize artifacts involving ascorbate reduction or photolysis. For elution, resins were incubated with 1% β-mercaptoethanol in HEN/10SDS and centrifuged, and the supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Sample preparation for proteomic analysis

Following SNO-RAC as described above, proteins captured on ∼50 μl TPS were washed with ammonium bicarbonate (AmBic), pH 8.0, and resuspended in a 2× bed volume of AmBic containing 0.1% Rapigest SF (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) and 400 ng of sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega Corp., Madison, WI). The beads were agitated overnight at 37°C at 1050 rpm in a Thermomixer R (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY). Following overnight digestion, the supernatant (SNO-sup fraction) was recovered by centrifugation and additional washing of beads 2× with AmBic, and the SNO-sup was adjusted to 2% acetonitrile (ACN) and 1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and heated at 60°C for 2 h to degrade the Rapigest. After centrifugation, the SNO-sup was concentrated to dryness by Speedvac (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and peptides were reconstituted in 20 μl of 2% ACN/1% TFA containing 25 fmol/μl of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase standard (MassPREP ADH; Waters).

For recovery of SNO-site peptides, the trypsin-digested TPS was washed 3× with 1 ml of each of the following [adapted from Kohr et al. (31)]: (a) PBS with 1% SDS; (b) AmBic; (c) 80/20/0.1 (v/v/v) MeCN/H20/TFA; (d) 50/50 (v/v) MeOH/H2O; and (e) AmBic. Peptides were eluted in a 2× resin volume of 10 mM DTT in AmBic with agitation for 30 min, as described above. The eluent fraction was recovered after centrifugation, and the beads were washed 2× with 100 μl AmBic. The combined supernatants were alkylated by addition of iodoacetamide in AmBic (2 molar excess over DTT) and incubation at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. The SNO-site peptides were reduced to dryness by SpeedVac and subjected to C18 Zip Tip (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) cleanup, according to the manufacturer's protocol. The eluent was again dried by SpeedVac and resuspended in 12 μl of 1% TFA/2% MeCN and 5 fmol/μl of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase standard (Waters MassPREP ADH).

Quantitative, label-free 1D-LC-MS/MS analysis

Analysis of the SNO-site fraction was performed essentially as previously described (20). Each sample was analyzed in duplicate using a NanoAcquity UPLC system coupled to a Synapt G2 HDMS mass spectrometer (Waters). Five microliters of peptide was trapped on a 20 μm ×180 mm Symmetry C18 column (Waters) at 20 μL/min for 5 min in water containing 0.1% formic acid (FA), and further separated on a 75 μm ×250 mm column with 1.7 μm C18 ethylene-bridged hybrid particles (Waters) using a gradient of 5–40% ACN/0.1% FA over 90 min at a flow rate of 0.3 μl/min and a column temperature of 45°C. Samples were analyzed in data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode using a 0.6 s precursor scan, followed by MS/MS product ion scans on the top three most intense ions using a dynamic exclusion window of 120 s. SNO-sup samples were analyzed in a similar manner, except that 2 μl (10%) of peptide digested was analyzed. Analyses also used data-independent acquisition (MSE) or HD-MSE, which utilized a 0.6 s cycle time alternating between low collision energy (6 V) and high collision energy ramp in the transfer region (27–50 V).

Following data acquisition, SNO-site or SNO-sup analyses were independently analyzed in Rosetta Elucidator v3.3 (Rosetta Biosoftware, Inc., Seattle, WA) (21, 43, 45). Briefly, samples were first subjected to accurate mass and retention time alignment. Area-under-the-curve measurements were performed to determine intensity for each feature (accurate mass and retention time pair). Due to the large difference in sample abundance across treatment groups, data were scaled to the internal ADH standard. For data acquired in DDA mode, .mgf searchable files were produced in Rosetta Elucidator and searched using Mascot v2.2 (Matrix Science, Inc., Boston, MA). For MSE or HD-MSE data, ProteinLynx Global Server 2.5 (Waters) was used to generate searchable files, which were then submitted to the IdentityE search engine (Waters) (22). Result files were then imported back into Elucidator.

Both DDA and MSE data were searched against the Swissprot database v57.1 with Mus musculus taxonomy (downloaded on April 21, 2012, with 24,013 entries) and contained an equal number of reverse decoys. Mascot searches used 10 ppm precursor and 0.04 Da product ion tolerances, and PLGS 2.5 was searched with autotolerance, resulting in final tolerances of ∼5 and ∼14 ppm for precursor and product ions, respectively. Data were searched with a maximum of two missed tryptic cleavages as well as variable oxidized (M) and deamidation (NQ) modifications, and a fixed carbamidomethyl (C) or methylthio (C) was used to search SNO-site and SNO-sup data, respectively.

For SNO-site data, annotations were made using a Mascot ion score giving a false discovery rate (FDR) of 1% based on the number of Cys-containing reverse hits. SNO-sup data were annotated at a 1% FDR using the PeptideProphet and ProteinProphet algorithms in Elucidator (28, 40). Quantitative SNO-sup and SNO-site data (Supplementary Tables S1, S2, and S4) and additional search result data, including, but not limited to, protein ID, protein molecular weight, number of peptides, number of spectra, sequence coverage, peptide name, and peptide mascot score, are available as Supplementary Table S5.

Statistical analyses

The experimental results are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. For comparisons between multiple groups, one-way or two-way ANOVA were followed by the Tukey or Bonferroni test, respectively. For single comparisons between two groups, Student's t-test was used. Analyses were carried out using PRISM 4® software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA), and p < 0.05 was considered to represent a significant difference.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

Conventional protein abbreviations are used in the text except when referring to Table 2 and other data derived from Supplementary Tables, where protein nomenclature is from Swiss-Prot.

- AA

ascorbate

- ACN

acetonitrile

- ACTC, ACTS, ACTA

cardiac, skeletal, and aortic smooth muscle actin

- ACTN2

α-actinin

- AmBic

ammonium bicarbonate

- AT2A2

sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase 2

- BDM

2,3-butanedione monoxime

- CASQ2

calsequestrin 2

- CMFs

cardiac myofibrils

- CysNO

S-nitrosocysteine

- 1D-LC-MS/MS

one-dimensional liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

- DDA

data-dependent acquisition

- Diazo-2

glycine, N-[2-[2-[2-[bis (carboxymethyl) amino]-5-(diazoacetyl) phenoxy]ethoxy]-4-methylphenyl]-N-(carboxymethyl)-, tetrapotassium salt

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EGTA

ethylene glycol-bis (2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- FA

formic acid

- FDR

false discovery rate

- Gö6983

3-[1-[3-(dimethylamino)propyl]-5-methoxyindol-3-yl]-4-(1H-indol-3-yl)pyrrole-2,5-dione

- G3P

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GSNO

S-nitrosoglutathione

- GSNOR

GSNO reductase

- H-89

N-[2-(bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-isoquinoline sulfonamide

- HD-MSE

ion mobility-assisted data-independent acquisition

- HEN

HEPES/EDTA/neocuproine

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl) piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MHC, MYH6

α-myosin heavy chain, cardiac

- MLC3, MYL3

myosin light chain 3 (also called myosin light chain 1 and essential light chain)

- MMTS

S-methyl methane thiosulfonate

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MSE

data-independent acquisition

- MW

molecular weight

- MyBPC3, MYPC3

myosin-binding protein C, cardiac

- NO

nitric oxide

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PKA, PKC

protein kinase A, protein kinase C

- PMSF

phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride

- RAC

resin-assisted capture

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- SL

sarcomere length

- SNO

S-nitrosothiol

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TES

2-[[1,3-dihydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)propan-2-yl]amino]ethanesulfonic acid

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- Tm, TPM1

tropomyosin α-1 chain

- TnC, TNNC1

troponin C, cardiac

- TnI, TNNI3

troponin I, cardiac

- TPS

thiopropyl sepharose 6B

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH) grants, HL103840 (to J.R.P.); HL106121 (to M.W.F.); and 5R01 HL094849 (to J.H.). Additional support was from the Florida Heart Research Institute (to J.R.P.), Brazilian agencies Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (to M.M.S.), and fellowships from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nivel Superior (CAPES) (to C.F.F.) and CNPq (to M.M.S., A.M.S.Y., and F.L.L.-R.). L.N. was supported by the Programa de Atração de Jovens Talentos (BJT-A/CAPES, Project#A005_2013). J.R.P. acknowledges the generous start-up support from the FSU College of Medicine.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Ahrne E, Molzahn L, Glatter T, and Schmidt A. Critical assessment of proteome-wide label-free absolute abundance estimation strategies. Proteomics 13: 2567–2578, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alves ML, Dias FA, Gaffin RD, Simon JN, Montminy EM, Biesiadecki BJ, Hinken AC, Warren CM, Utter MS, Davis RT, 3rd, Sadayappan S, Robbins J, Wieczorek DF, Solaro RJ, and Wolska BM. Desensitization of myofilaments to Ca2+ as a therapeutic target for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with mutations in thin filament proteins. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 7: 132–143, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrade FH, Reid MB, Allen DG, and Westerblad H. Effect of nitric oxide on single skeletal muscle fibres from the mouse. J Physiol 509: 577–586, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balon TW. and Nadler JL. Nitric oxide release is present from incubated skeletal muscle preparations. J Appl Physiol 77: 2519–2521, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baudenbacher F, Schober T, Pinto JR, Sidorov VY, Hilliard F, Solaro RJ, Potter JD, and Knollmann BC. Myofilament Ca2+ sensitization causes susceptibility to cardiac arrhythmia in mice. J Clin Invest 118: 3893–3903, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beigi F, Gonzalez DR, Minhas KM, Sun QA, Foster MW, Khan SA, Treuer AV, Dulce RA, Harrison RW, Saraiva RM, Premer C, Schulman IH, Stamler JS, and Hare JM. Dynamic denitrosylation via S-nitrosoglutathione reductase regulates cardiovascular function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 4314–4319, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broniowska KA. and Hogg N. The chemical biology of S-nitrosothiols. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 969–980, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broniowska KA, Zhang Y, and Hogg N. Requirement of transmembrane transport for S-nitrosocysteine-dependent modification of intracellular thiols. J Biol Chem 281: 33835–33841, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryan NS, Calvert JW, Elrod JW, Gundewar S, Ji SY, and Lefer DJ. Dietary nitrite supplementation protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 19144–19149, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calvert JW, Condit ME, Aragon JP, Nicholson CK, Moody BF, Hood RL, Sindler AL, Gundewar S, Seals DR, Barouch LA, and Lefer DJ. Exercise protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via stimulation of beta(3)-adrenergic receptors and increased nitric oxide signaling: role of nitrite and nitrosothiols. Circ Res 108: 1448–1458, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canton M, Menazza S, Sheeran FL, Polverino de Laureto P, Di Lisa F, and Pepe S. Oxidation of myofibrillar proteins in human heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 57: 300–309, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chouchani ET, Methner C, Nadtochiy SM, Logan A, Pell VR, Ding S, James AM, Cocheme HM, Reinhold J, Lilley KS, Partridge L, Fearnley IM, Robinson AJ, Hartley RC, Smith RA, Krieg T, Brookes PS, and Murphy MP. Cardioprotection by S-nitrosation of a cysteine switch on mitochondrial complex I. Nat Med 19: 753–759, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coulton AT. and Stelzer JE. Cardiac myosin binding protein C and its phosphorylation regulate multiple steps in the cross-bridge cycle of muscle contraction. Biochemistry 51: 3292–3301, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dedkova EN, Wang YG, Ji X, Blatter LA, Samarel AM, and Lipsius SL. Signalling mechanisms in contraction-mediated stimulation of intracellular NO production in cat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 580: 327–345, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doulias PT, Tenopoulou M, Greene JL, Raju K, and Ischiropoulos H. Nitric oxide regulates mitochondrial fatty acid metabolism through reversible protein S-nitrosylation. Sci Signal 6: rs1, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dulce RA, Yiginer O, Gonzalez DR, Goss G, Feng N, Zheng M, and Hare JM. Hydralazine and organic nitrates restore impaired excitation-contraction coupling by reducing calcium leak associated with nitroso-redox imbalance. J Biol Chem 288: 6522–6533, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyson A, Bryan NS, Fernandez BO, Garcia-Saura MF, Saijo F, Mongardon N, Rodriguez J, Singer M, and Feelisch M. An integrated approach to assessing nitroso-redox balance in systemic inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med 51: 1137–1145, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evangelista AM, Rao VS, Filo AR, Marozkina NV, Doctor A, Jones DR, Gaston B, and Guilford WH. Direct regulation of striated muscle myosins by nitric oxide and endogenous nitrosothiols. PLoS One 5: e11209, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forrester MT, Foster MW, and Stamler JS. Assessment and application of the biotin switch technique for examining protein S-nitrosylation under conditions of pharmacologically induced oxidative stress. J Biol Chem 282: 13977–13983, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Forrester MT, Thompson JW, Foster MW, Nogueira L, Moseley MA, and Stamler JS. Proteomic analysis of S-nitrosylation and denitrosylation by resin-assisted capture. Nat Biotechnol 27: 557–559, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster MW, Thompson JW, Que LG, Yang IV, Schwartz DA, Moseley MA, and Marshall HE. Proteomic analysis of human bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after subsgemental exposure. J Proteome Res 12: 2194–2205, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geromanos SJ, Vissers JP, Silva JC, Dorschel CA, Li GZ, Gorenstein MV, Bateman RH, and Langridge JI. The detection, correlation, and comparison of peptide precursor and product ions from data independent LC-MS with data dependant LC-MS/MS. Proteomics 9: 1683–1695, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grabarek Z. Structural basis for diversity of the EF-hand calcium-binding proteins. J Mol Biol 359: 509–525, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]