Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to collect evidence with respect to perception and practice of unmarried women toward the use of emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs).

Materials and Methods:

Non-probability purposive sampling was used to select respondents. A total of 250 respondents were administered the tools for the study, of which 228 were considered for analysis.

Results and Discussion:

Descriptive statistics showed that nearly 87% of the respondents were aware of ECPs and there was a significant difference in the knowledge of ECP of the respondents by type of the institution they had studied. More than half of the (52%) respondents admitted to have boyfriends of which 16% were sexually involved and were using some form of contraception. Nearly 84% of the respondents used ECP, which superseded the use of other contraceptives. It was further found that around two-third respondents were using ECP regularly. The reason that “ECP did not hinder pleasure” and that it was handy in case of “unplanned contact” were the most cited reasons for using ECP as a regular contraceptive.

Conclusion:

The fact that ECPs was preferred over condom and was used regularly shows that the respondents were at a risk of sexually transmitted infection/human immunodeficiency virus. Health-care providers could be the most authentic source of information for orienting young women toward the use of safe sexual practices.

Keywords: Contraceptives, emergency contraceptive pill, risk of sexually transmitted infection/human immunodeficiency virus, unmarried women

Introduction

The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act helped in legalizing abortions in India as early as 1972.[1] Despite the legalization, the number of unsafe abortions did not show any substantial improvement.[2] Though there are no yearly estimates of the number of induced abortions, data collected from different nationwide sources from early 1966 to 1994 shows somewhat uncoordinated picture. The number of induced abortions were around 3.9 million in 1966,[3] which rose to 6.5 million in 1970.[3] A decline was registered in 1976 with the number of induced abortions going down to around 4.6 million.[4] In 1991, as per a study done by United Nations Children's Fund the number had again increased to 5 million, another study conducted by the Government of India (GoI) around the same period cites the number of induced abortions just around 0.6 million. In 1994, a study stated the number of induced abortions to be as high as 6.7 million.[5]

Though, limited data exist on the number of maternal deaths from abortion in India, the Survey of Causes of Death from 1991 to 1995 reported that nearly 18% of maternal deaths resulted from abortion (Office of the Registrar General of India, n.d.). The social taboo attached to rape, domestic abuse and sex without or outside marriage can result in unwanted pregnancy and puts a woman in a situation where she wishes to get confidential abortion services. This needs to drive women toward illegal abortion services to get rid of the unintended/unwanted pregnancy and thus risk her health and life.

Under the National Family Welfare Program, emergency contraceptive pill (ECP) was introduced as a prescription drug by the GoI in 2003 as one of the tools to fight against unintended pregnancy. This however, did not fulfill the desired expectations of substantially decreasing unsafe and illegal abortions. The GoI therefore converted ECP over the counter drug in 2005.[6]

The life-style among the youth in India is fast changing. Increasing number of youth are relocating to bigger cities for study or work and are exposed to new life style and cosmopolitan culture, which attracts or sometimes pushes them to new ways of life which may or may not be approved by the society. Although pre-marital sexual behavior among adolescents and youth remain poorly explored topics in India, the available evidence suggests that up to 10% of all females are sexually active during adolescence before marriage.[7] Some teenagers with unintended pregnancies resort to abortions, which are often performed under unhygienic and potentially life-threatening conditions.[8] While others bear their pregnancies to term, incurring the risk of morbidity and mortality related to pregnancy and delivery, together with serious social risks.[9]

The fact that one of the technical strategies of the Reproductive and Child Health II program of the GoI is adolescent reproductive sexual health which focuses on reorganizing the existing public health system to meet the needs of adolescents (10-19 years) through preventive, promotive, curative and counseling services, shows that there is a clear recognition of the role of health workers in ensuring sexual health of the younger population.

Various unpublished sources indicated that awareness of ECP had led to its irrational use by unmarried women.[10] The objective of this study was to collect scientific evidence with respect to perception and practice of unmarried women toward the use of emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs).

Methodology

Non-probability purposive sampling technique was used to select the respondents. The sites were randomly selected. A list was prepared for the popular places among youths — including malls, eating joints and parks. Of the list, eight places were randomly selected and respondents were contacted for the interview at these places. A quantitative schedule was developed to collect the required information from the respondents. A total of 250 unmarried women were approached, however responses of 228 respondents could only be considered as the rest were discarded due to incomplete or inconsistent data. Once the data was collected and cleaned it was further processed and analyzed using descriptive statistics and tests of association.

Results and Discussion

Demographic profile of the respondents

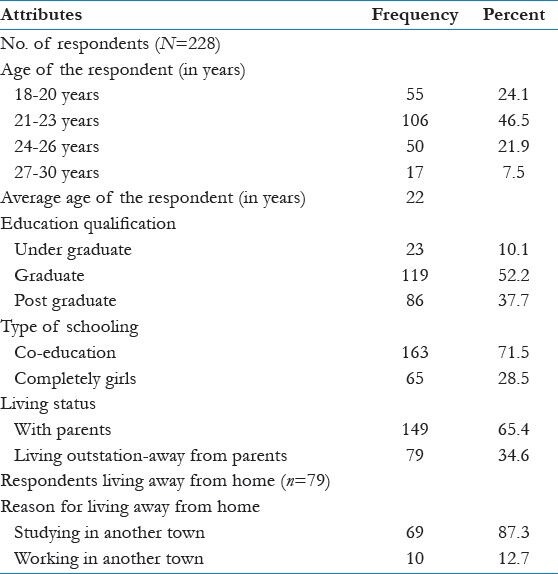

All the unmarried women who were interviewed fell in the age group of 18-30 years. Around one-fourth (24%) of the respondents were 18-20 years of age and around half of the respondents (47%) were between the age group of 21 and 23 years. About 22% fell in the age group of 24-26 years and the remaining around 8% were between 27 and 30 years of age. The mean age of the respondents was about 22 years. Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the respondents.

Table 1.

Profile of the respondents

All the respondents were literate. The minimum level of education of the respondents was higher secondary. Around 52% had completed their graduation and about 38% had completed their post-graduation degree. About 10% of the respondents were undergraduates. More than three-fourth (72%) of the respondents were from co-educational schools. Around 65% of the respondents were living with their parents, whereas about 35% were living away in hostels, on rent or other accommodations away from their native place. Of the respondents who were living away from their parents about 87% relocated to complete their studies and about 13% were working.

Knowledge of family planning methods and source of knowledge about ECP

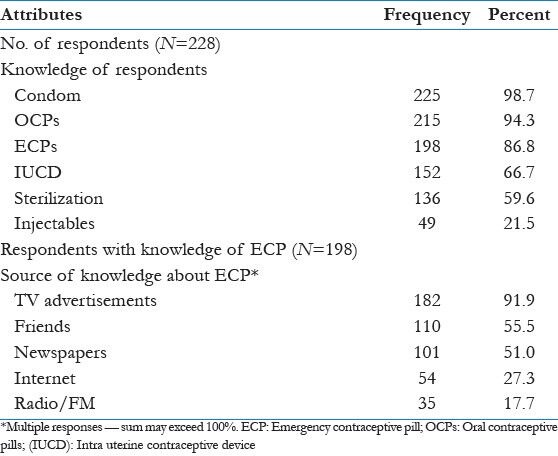

The respondents were asked if they knew of any family planning method, it was found that nearly 99% of the respondents were aware of condoms and about 95% of the respondents were aware of oral contraceptive pill (OCP) followed by ECPs which was known to about 87% of the respondents. Other methods like intra-uterine contraceptive device (IUCD), sterilization and injectable were known to about 67%, 60% and 22% respondents respectively.

The respondents who had knowledge of ECP were further asked about the source of their knowledge. Almost 92% of the respondents reported that they had received the knowledge in regard to ECP from the television advertisements. The second highest percentage was the knowledge gathered from the peer group or friends (56%).

Newspapers followed suit as about 51% of the respondents had gained knowledge about ECP through print media. Internet was also among the top five sources, which were quoted by the respondents. Nearly 27% of the respondents came to know about ECP from the internet. Table 2 given below shows the knowledge of family planning methods and from where did the respondent procure the same.

Table 2.

Knowledge of family planning methods and source of knowledge of ECP

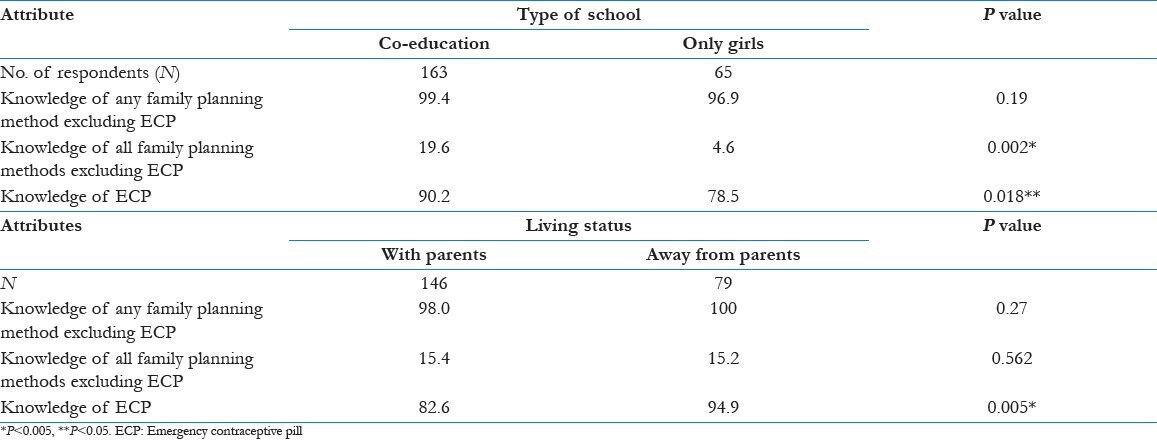

In order to further categorize the responses and understand if there is some significant difference between the responses made by respondents from co-educational institutions in contrast with those respondents who were educated from an all girl's institution, Chi-square was calculated on three indicators namely - knowledge of any family planning method, knowledge of all family planning methods and knowledge of ECP.

As mentioned above, about 72% of the respondents had been educated in co-educational institutions, of them about 99% had knowledge of some or the other method to avoid pregnancy and 90% had knowledge about ECP. The remaining, i.e., around 28% of the respondents came from all girls schools, and of them nearly 97% reported to have the knowledge to prevent pregnancy, whereas about 79% had knowledge of ECP. It was observed that the respondents who have studied in co-educational institutions had better knowledge about contraceptives than those who have studied in all girls schools. The difference was found significant for knowledge of all family planning methods (P < 0.01) and knowledge of ECP (P < 0.05).

To understand if living away from parents is also associated with the awareness level, the respondents were compared. Table 3 shown below depicts that the respondents who were living away from their parents had cent per cent knowledge of regular family planning methods and 95% had knowledge about ECP. On the other hand of the respondents who were living with their parents, about 83% had knowledge about ECP. The difference between the two groups was found significant for knowledge of ECP (P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Knowledge of contraceptives and ECPs by type of school and status of living-with or away from parents

Perception and practice: Boyfriends and pre-marital sexual relationship

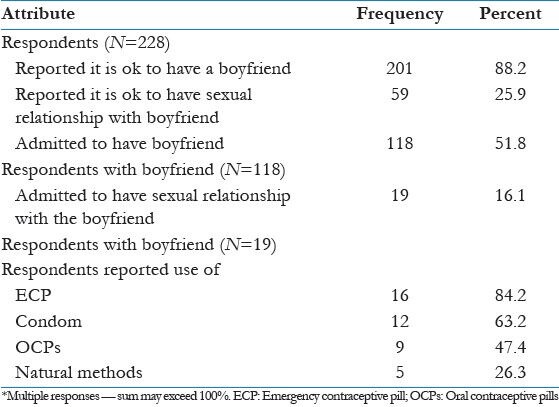

The respondents were further probed to understand their perceptions toward relationships. On asking if they thought it was all right to have a boyfriend, nearly 88% of the respondents felt that there was nothing wrong in having a boyfriend. More than one-fourth of such respondents (26%) reported sexual relationship with the boyfriend to be fine.

The respondents were further probed about their relationship status. Of the total respondents, more than half (52%) admitted to have boyfriends. Of these, around 16% admitted to be sexually involved with their partners. It was also found that all the respondents who were sexually involved were aware of ECP. Studies done in the past also claim that “sexually exposed” girls are more likely to be aware of ECP.[11,2]

Use of contraceptives including ECP

Of the total number of respondents who were sexually involved all of them were using some form of contraception. It was found that four out of five respondents (84%) had used ECP, which superseded the use of other contraceptives. Condoms had been used by only about 63% of the respondents. It is also important to note that the respondents had knowledge of condoms, but did not prefer to use them, which was a rather unexpected result of the study as methods like condoms, which safeguard against sexually transmitted diseases and human immunodeficiency virus-acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV-AIDS) were not being considered. OCPs were used by around 47% respondents, which was an interesting piece of finding as OCPs are to taken on a daily basis. The intake of OCPs may also be attributed to couples living together. The rest, i.e., around 26% of the respondents had used natural methods [Table 4].

Table 4.

Percent respondents on their perception of sexual relationships, their relationship status and the contraceptives used by them

Frequency of use of ECP and its reasons

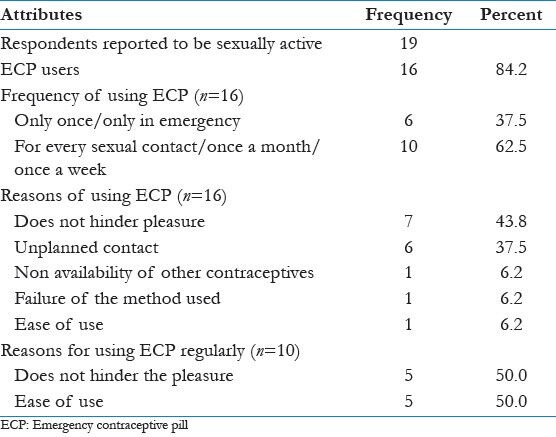

As per ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2006)[12] ECP is not recommended as a routine family planning method; however, it is a very useful method after unprotected sexual intercourse to reduce the chance of unwanted pregnancies. It was found that around two-third respondents who were using ECP, were regular users which made them susceptible to higher risks associated with sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV. Only about 38% of the respondents reported to have used ECP only in case of emergency.

In order to understand the reasons for considering ECP over the other methods the respondents who had used ECP were asked about the reasons for the same. More than two out of every five respondents reported that ECP did not hinder pleasure. It was followed by 38% of the respondents who reported that the contact was unplanned. About 6% used ECP as they could not gain access to other contraceptives at that point of time.

Condom breakage/method failure was reported by about 6% of the respondents and another 6% stated that they took ECP for the sheer ease of use. When the same analysis was performed for those respondents who had reported for ECP use on a regular basis, half of the respondents reported to be using ECP as it did not hinder pleasure and the other found ECP as an easy alternative [Table 5].

Table 5.

Percent distribution of respondents by frequency of use of ECP and its reasons

Conclusion

The youth at this stage in a country like India are in a phase of transition. While the independence is being sought, taken and experienced at the individual level by the youth, the societal norms continue to hold its importance. The thoughts and ways of living life are changing faster at the individual level than they are changing at the societal level. There is a deep rooted stigma attached for pregnancy before marriage and hence while independence experienced at the individual level does not inhibit indulgence in pre-marital sexual activities, pregnancy in case of unmarried women continues to be a taboo. This is coupled with the perceived inhibition regarding use of condom, particularly by the male partners.[13]

More than four out of five respondents (84%) were in favor of use of ECP and preferred it over other contraceptives. Nearly, 44 of the respondents were using ECP as it did not hinder pleasure and they could easily escape from the fear of pregnancy in times of unplanned contact. ECP, however is not a regular contraceptive and does not safeguard against STIs and HIV. The fact that ECPs was preferred over condom shows that the danger of pregnancy superseded danger of STI/HIV.

A study emphasized that the strategy for marketing of condoms should be aimed at prevention of STIs and HIV so that the availability of ECPs do not discourage the use of condoms,[14] and niether does it influence patterns of sexual risk taking behavior.[15] Awareness generation is the key to the promotion of safe sex and so is the rational use of ECP. While ECP needs to be promoted so that women do not have to suffer unintended pregnacies, it is equally important that promotion programs presents the disadvantage of ECP of not being able to provide protection against STI and HIV/AIDS.

Health providers, both doctors and paramedicals and the counsellors could be the best source of providing authentic and complete information to adolescents and youth about sexual health, however a few studies have revealed that the knowledge of health-care providers is limited in this arena. A knowledge, attitude and practice study among health-care providers in North India showed that only about 41% of general practioners were vaguely aware of ECP and its concept.[16]

For the purpose of giving correct knowledge and decreasing pre-judices, it is important that health-care providers - both doctors and parademics, especially in the public health sector are provided training on both contraception, particularly emergency contrception and counselling on adolescents and youth. This will in turn result in the dissemination of knowledge and may help in developing an enough trust and self confidence in the adoloscents and youth to enable them to take wise decisions with regard to their sexual health.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Funding provided by ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research).

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Government of India. The Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act. Act No. 34. 1971. http://dc-siwan.bih.nic.in/mtp%20Act.pdf .

- 2.Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2001. WHO. The World Health Report 2001 - Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston HB. Santacruz (East), Mumbai: CEHAT; 2002. Abortion Practice in India. Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT) Research Centre of Anusandhan Trust. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sood M, Juneja Y, Goyal U. Maternal mortality and morbidity associated with clandestine abortions. J Indian Med Assoc. 1995;93:77–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chhabra R, Nuna SC. New Delhi, India: Veerendra Printers; 1994. Abortion in India: An Overview. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MOHFW). District Household Survey (Phase I) 2008. [Last accessed on 2013 May 10]. Available from: http://mohfw.nic.in/breakfile2.html .

- 7.Jejeebhoy S, Ramasubban R. Women's Reproductive Health in India Jaipur. Rawat Publications; 2000. Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive behavior: A review of the evidence from India. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganatra B, Hirve S. Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharashtra, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2002;10:76–85. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(02)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sychareun V, Hansana V, Phengsavanh A, Phongsavan K. Awareness and attitudes towards emergency contraceptive pills among young people in the entertainment places, Vientiane City, Lao PDR. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-13-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NDTV. iPod, iPhone, iPill? NDTV news. [2010 May 8] [Accessed on March 6, 2013]. http://www.ndtv.com/video/player/secret-lives/ipod-iphoneipill/141586 .

- 11.Narzary PK. Sexual exposure and awareness of emergency contraceptive pills among never married adolescent girls in India. J Soc Dev Sci. 2013;4:164–73. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elizabeth RG, Felicia S, Mark W, Charles M, Barbara VDP. Impact of Increased Access to Emergency Contraceptive Pills: A Randomized Controlled Trial, Amercian College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2006 Nov;108(5):1098–1106. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000235708.91572.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner MJ, Cates W, Jr, Warner L. The real problem with male condoms is nonuse. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:459–62. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199909000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Relwani N, Saoji A, Kasturwar NB, Nayse J, Junaid M, Dhatrak P. Emergency contraception: Exploring the knowledge, attitude and practices of engineering college girls in Nagpur district of central India. Natl J Community Med. 2012;3:14–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahiya K, Mann S. Women's knowledge and opinion regarding emergency contraception. J S Asian Fed Obstet Gynaecol. 2012;4:151–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tripathi R, Rathore AM, Sachdeva J. Emergency contraception: Knowledge, attitude, and practices among health care providers in North India. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2003;29:142–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1341-8076.2003.00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]