Abstract

The breadth of anatomical and functional diversity among amniote external genitalia has led to uncertainty about the evolutionary origins of the phallus. In several lineages, including the tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus, adults lack an intromittent phallus, raising the possibility that the amniote ancestor lacked external genitalia and reproduced using cloacal apposition. Accordingly, a phallus may have evolved multiple times in amniotes. However, similarities in development across amniote external genitalia suggest that the phallus may have a single evolutionary origin. To resolve the evolutionary history of amniote genitalia, we performed three-dimensional reconstruction of Victorian era tuatara embryos to look for embryological evidence of external genital initiation. Despite the absence of an intromittent phallus in adult tuataras, our observations show that tuatara embryos develop genital anlagen. This illustrates that there is a conserved developmental stage of external genital development among all amniotes and suggests a single evolutionary origin of amniote external genitalia.

Keywords: macroevolution, penis, hemipenis, amniote

1. Introduction

The evolution of internal fertilization was a critical step towards the diversification of amniotes. In most amniotes, internal fertilization is facilitated by intromission of the male phallus into the female's cloaca (or mammalian vagina) to deliver sperm. However, some lineages lack an intromittent phallus and copulate through cloacal apposition [1–3]. The striking diversity of phallus form and function among amniotes, and the absence of a phallus in several unrelated lineages, have led to competing hypotheses regarding their evolutionary origins [4–9]. Whether the phallus evolved once at the origin of amniotes or independently among amniote lineages remains debated. Although adult anatomy provides relatively little information regarding the relationship of the phallus among different clades, an understanding of the embryonic origins of the phallus is shedding new light on its evolutionary ancestry [10].

Phallus position, number and gross anatomy differ among amniote clades (table 1). Mammals, some birds (Palaeognathae, the most basal clade, and Anseriformes, water fowl), crocodilians and chelonians (turtles) have a single midline phallus. Squamates (lizards and snakes) have paired, lateral hemipenes, whereas an intromittent phallus is reduced or absent in the majority of birds (97%) and in the tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus [2,3,11,12]. The phallus of birds, crocodilians and turtles has an endodermally derived open groove, known as the sulcus spermaticus, on the ventral side of the phallus, which channels sperm towards the phallus tip [2,13–15]. Squamates also possess an open sulcus on each hemipenis, but the squamate sulcus forms as an invagination of surface ectoderm [16,17]. Mammals possess a closed urethral tube that is derived from endoderm; however, in some species (e.g. rabbit and human) the penis passes through a stage with an open sulcus-like groove that later closes [18,19].

Table 1.

Variation among amniote phalluses. *, this study.

| external genital swellings number and position | phallus number and position | open sulcus or closed urethra | germ layer contributing to sulcus/urethra | primary erectile mechanism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphenodon | paired, lateral buds* | no mature phallus | |||

| Squamata | paired, lateral buds | paired, lateral hemipenes | open sulcus | ectoderm | blood/lymph |

| Chelonia | paired, lateral buds | single, midline phallus | open sulcus | endoderm | blood |

| Crocodilia | paired, lateral buds | single, midline phallus | open sulcus | endoderm | muscle/blood |

| Mammalia | paired, lateral buds | single, midline phallus | tubular urethra | endoderm | blood |

| Aves (Palaeognathae, Anseriformes) | paired, lateral buds | single, midline phallus | open sulcus | endoderm | lymph |

| Aves (Neoaves, Galiformes) | paired, lateral buds | no mature intromittent phallus | |||

Amniotes also possess a range of functional anatomical differences in their phalluses. For example, all clades use some degree of hydrostatic pressure for phallic erection, but the fluid that engorges the phallus varies. Mammals and turtles use blood to achieve an erection [6,7], birds use lymph [2] and squamates use a combination of lymph and blood to erect their hemipenes [20].

Despite the diversity of adult forms, the phallus has a similar developmental origin in all amniotes examined to date. Recent studies in birds [5,21] and squamates [5] show that external genitalia are derived from two populations of progenitor cells adjacent to (and perhaps overlapping with) the progenitors of the left and right hindlimb buds. In clades with a single, midline phallus, these cells give rise to paired genital swellings (figure 1a) that expand towards the midline, where they merge to form the genital tubercle, the precursor to the phallus [12,14,15,19]. The squamate hemiphallus also forms from paired swellings, but rather than merging at the midline, they remain separate to form two discrete phalluses [9,16,17]. In reptiles (including birds), additional cloacal swellings emerge and fuse to form cloacal lips, although there are subtle differences in their number and position [10]. Furthermore, comparative analyses of gene expression and function show that similarities of external genital development among amniotes extend to the molecular mechanisms [10,12,19].

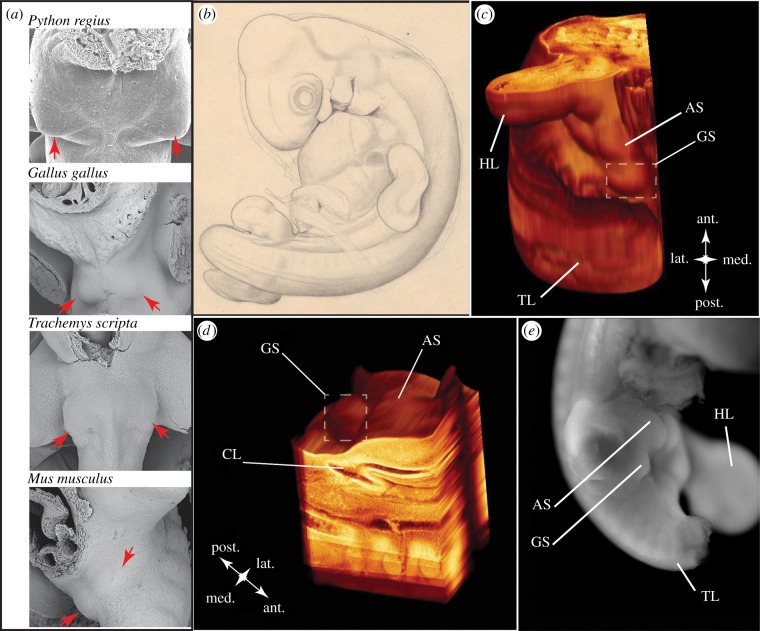

Figure 1.

Initiation of amniote external genitalia consistently begins as paired genital swellings (a, red arrows); specimens taken from [10,12,15,17,19]. (b) Illustration of tuatara embryo 1491 from the Harvard Embryological Collection (HEC). (c,d). This embryo possesses genital swellings (GS) and anterior swellings (AS) adjacent to the cloaca (CL) at a stage comparable with when other amniote species are undergoing external genital morphogenesis (HL, hindlimb; TL, tail). This morphology is remarkably similar to what is observed in squamates, such as Anolis carolinensis (e; tail and right hindlimb removed).

The phylogenetic distribution of shared embryological and molecular characters associated with amniote external genital morphogenesis suggests the phallus may have a single evolutionary origin. Under this evolutionary scenario, lineage-specific modifications underlie phallus diversity, including repeated phallus loss. This hypothesis is complicated, however, by the phylogenetic position of S. punctatus as the sister group to squamates, as S. punctatus lacks an intromittent phallus as an adult and reproduces through cloacal apposition [1]. This raises the possibility that S. punctatus represents the ancestral amniote condition and that embryological similarities (e.g. paired genital swellings) are secondarily derived. To help resolve the evolutionary history of amniote external genitalia, we assessed whether S. punctatus embryos undergo early stages of external genital initiation, despite the absence of an intromittent phallus in adults. If evidence of paired genital swellings is found in tuatara embryos, then this would be indicative of an evolutionarily conserved stage of external genital development among amniotes. Phylogenetic continuity of this developmental character state would be consistent with the hypothesis that external genitalia evolved once, at least as early as the amniote common ancestor.

2. Material and methods

As the sister group to squamates, S. punctatus occupies an important phylogenetic position for resolving amniote genital evolution (electronic supplementary material, §S1.2); however, acquisition of new embryological material is difficult owing to the close management of this species [11]. The most comprehensive collection of S. punctatus embryos was performed by Arthur Dendy between 1896 and 1897 [22]. In 1909, Dendy transferred four embryos to Charles Minot, curator of the Harvard Embryological Collection (HEC) (electronic supplementary material, §S1.2, figure S2.1), where they were prepared histologically. We examined the historical records and concluded that of the four S. punctatus embryos sent to Minot, one embryo, specimen 1491, is the ideal stage at which to examine the cloacal region for evidence of genital swellings (figure 1b).

Minot histologically prepared embryo 1491 into 8 µm thick sagittal sections relative to the head (electronic supplementary material, figure S2.3), but the relative positioning of the limb buds, cloaca and any presumptive genital swellings is obscured because of the embryo's body torsion (figure 1b). Therefore, we performed three-dimensional reconstruction of the cloacal region of 1491 on a series of 82 serial sections (see electronic supplementary material, §S1.3).

To prepare sections for reconstruction, slides were cleaned and photographed, and debris from damaged tissue was removed digitally (electronic supplementary material, figure S2.3). We then aligned the sections in Amira 5.0 (FEI Visualization Sciences Group) and imaged them through a series of digital filters [23] to create a three-dimensional model of the embryo's posterior right side. Additional slides that presumably included the left side of the body are no longer held by the HEC.

3. Results and discussion

Genital swellings are visible in the three-dimensional reconstruction of the S. punctatus embryo 1491 between the hindlimb bud (figure 1c) and cloaca (figure 1d), which can also be observed in the original histological sections (electronic supplementary material, figure S2.4). To better understand the positional relationship of the genital swellings to the cloaca and hindlimb, we prepared a second reconstruction that focused on the cloacal region (figure 1d). In this model, one genital swelling is visible immediately lateral to the cloacal urodeum, at the same position where one finds the right genital swelling in other amniotes [10,19]. A second swelling is observed anterior to the cloaca, in the position appropriate for the anterior cloacal swelling of squamates (figure 1e; electronic supplementary material, S2.5, [9,16,17]). Thus, the reconstruction of the S. punctatus cloacal region reveals the presence of the right genital and anterior cloacal swellings, indicating that although this species lacks an intromittent phallus as an adult, development of a phallus and cloacal lip is initiated in the embryo.

Our observations suggest that S. punctatus undergoes a similar developmental progression to galliform birds that lack an intromittent phallus. In the chicken, Gallus gallus, and quail, Coturnix coturnix, outgrowth of paired genital swellings initiates morphogenesis of the resultant genital tubercle, which later regresses owing to programed cell death [12]. Our data indicate that the early stages of external genital development occur in S. punctatus embryos, and we suggest that the absence of an intromittent phallus in adult tuatara could result from a similar process of programmed cell death or diminished proliferation at stages later than embryo 1491.

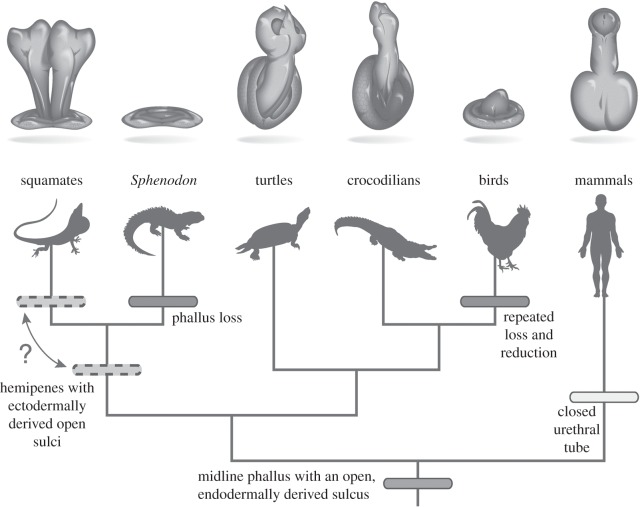

The presence of external genital swellings in S. punctatus suggests that, despite wide diversity in adult anatomy, there is a conserved developmental program controlling early phallus development in amniotes. The phylogenetic continuity of this developmental character—paired external genital swellings adjacent to the cloaca—across amniotes suggests that paired genital swellings are plesiomorphic and that independent convergence is not parsimonious. We propose that the amniote common ancestor likely had a single, midline phallus with an open endodermally derived sulcus (figure 2). Hemipenes form from a modification to the ancestral developmental program wherein the paired genital swellings fail to merge at the midline, instead maturing independently as two discrete phallic structures. Mammals evolved a urethral tube when the sulcus-like urethral groove gained the ability to undergo tubulogenesis and internalization. The data presented here, along with previous developmental studies of galliform birds [12,21], suggest that the absence of an intromittent phallus in tuataras and birds are homoplasies that resulted from independent evolutionary reductions. These new developmental data support earlier proposals that a midline phallus was lost in lepidosaurs [8,25].

Figure 2.

A resolved hypothesis regarding the evolution of amniote external genitalia. Our observations suggest that the phallus evolved once and diversified among amniote lineages. We cannot determine if the lepidosaur ancestor possessed mature hemipenes, but the embryological programs that pattern the cloaca and hemipenes of extant squamates likely evolved before the divergence of Rhynchocephalia and Squamata. Phylogeny after Chiari et al. [24].

Taken together with previous studies of external genital development, the data from tuatara support the hypothesis that the amniote phallus had a single evolutionary origin that was followed by lineage-specific modifications that underlie the diversity observed in extant amniotes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, Department of Herpetology, for access to the HEC. We thank F. Leal, C. Larkins, A. Herrera, and C. Perriton for the specimens used in figure 1a.

Data accessibility

The original and digitally restored images used for reconstruction have been archived with the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, the holder of the original histological slides.

Authors' contributions

T.J.S. conceived of this project. T.J.S., M.L.G., M.J.C. designed the study. T.J.S. photographed specimens and performed reconstructions with assistance from M.L.G. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript and approve the information presented within.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Funding

This project was funded by NSF (IOS-0 843 590) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to M.J.C.).

References

- 1.Gans C, Gillingham JC, Clark DL. 1984. Courtship, mating and male combat in tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus. J. Herpetol. 18, 194–197. ( 10.2307/1563749) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King A. 1981. Phallus. In Form and function in birds (eds King A, McLelland J), pp. 107–148. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briskie JV, Montgomerie R. 1997. Sexual selection and the intromittent organ of birds. J. Avian Biol. 28, 73–86. ( 10.2307/3677097) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wake MH. 1972. Evolutionary morphology of the caecilian urogenital system. IV. The cloaca. J. Morphol. 136, 353–365. ( 10.1002/jmor.1051360308) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tschopp P, Sherratt E, Sanger TJ, Groner AC, Aspiras AC, Hu JK, Pourquié O, Gros J, Tabin CJ. 2014. A relative shift in cloacal location repositions external genitalia in amniote evolution. Nature 516, 391–394. ( 10.1038/nature13819) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly DA. 2004. Turtle and mammal penis designs are anatomically convergent. Proc. R. Soc. B 271, S293–S295. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0161) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly DA. 2002. The functional morphology of penile erection: tissue designs for increasing and maintaining stiffness. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42, 216–221. ( 10.1093/icb/42.2.216) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gauthier J, Klugel AG, Rowe T. 1988. Amniote phylogeny and the importance of fossils. Cladistics 4, 105–209. ( 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1988.tb00514.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raynaud A, Pieau C. 1985. Embryonic development of the genital system. In Biology of the Reptilia, vol. 15 (eds Gans C, Billett F), pp. 149–300. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gredler ML, Larkins CE, Leal F, Lewis AK, Herrera AM, Perriton CL, Sanger TJ, Cohn MJ. 2014. Evolution of external genitalia: insights from reptilian development. Sex Dev. 8, 311–326. ( 10.1159/000365771) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cree A. 2014. Tuatara: biology and conservation of a venerable survivor. Christchurch, New Zealand: Canterbury University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herrera AM, Shuster SG, Perriton CL, Cohn MJ. 2013. Developmental basis of phallus reduction during bird evolution. Curr. Biol. 23, 1065–1074. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.062) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wake MH. 1979. Hymans's comparative vertebrate anatomy, 3rd edn Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gredler ML, Seifert AW, Cohn MJ. 2015. Morphogenesis and patterning of the phallus and cloaca in the American alligator, Alligator mississippiensis. Sex Dev. 9, 53–67. ( 10.1159/000364817) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larkins CE, Cohn MJ. 2015. Phallus development in the turtle Trachemys scripta. Sex Dev. 9, 34–42. ( 10.1159/000363631) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gredler ML, Sanger TJ, Cohn MJ. 2015. Development of the cloaca, hemipenes, and hemiclitores in the green anole, Anolis carolinensis. Sex Dev. 9, 21–33. ( 10.1159/000363757) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leal F, Cohn MJ. 2015. Development of hemipenes in the ball python snake Python regius. Sex Dev. 9, 6–20. ( 10.1159/000363758) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurzrock EA, Jegatheesan P, Cunha GR, Baskin LS. 2000. Urethral development in the fetal rabbit and induction of hypospadias: a model for human development. J. Urol. 164, 1786–1792. ( 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67107-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perriton CL, Powles N, Chiang C, Maconochie MK, Cohn MJ. 2002. Sonic hedgehog signaling from the urethral epithelium controls external genital development. Dev. Biol. 247, 26–46. ( 10.1006/dbio.2002.0668) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnold EN. 1986. The hemipenis of lacertid lizards (Reptilia: Lacertidae): structure, variation and systematic implications. J. Nat. Hist. 20, 1221–1257. ( 10.1080/00222938600770811) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrera AM, Cohn MJ. 2014. Embryonic origin and compartmental organization of the external genitalia. Sci. Rep. 4, 6896 ( 10.1038/srep06896) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dendy A. 1899. Outlines of the development of the tuatara, Sphenodon punctatus. Q. J. Microsc. Sci. s2–S42, 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handschuh S, Schwaha T, Metscher BD. 2010. Showing their true colors: a practical approach to volume rendering from serial sections. BMC Dev. Biol. 10, 41 ( 10.1186/1471-213X-10-41) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chiari Y, Cahais V, Galtier N, Delsuc F. 2012. Phylogenomic analyses support the position of turtles as the sister group of birds and crocodiles (Archosauria). BMC Biol. 10, 65 ( 10.1186/1741-7007-10-65) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Evans SE. 1988. The early history and relationships of the Diapsida. In The phylogeny and classification of the tetrapods (ed. Benton MJ.), pp. 221–260. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original and digitally restored images used for reconstruction have been archived with the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, the holder of the original histological slides.