Abstract

Key points

Short‐term facilitation takes place at GABAergic synapses between cerebellar Purkinje cells (PCs).

By directly patch clamp recording from a PC axon terminal, we studied the mechanism of short‐term facilitation.

We show that the Ca2+ currents elicited by high‐frequency action potentials were augmented in a [Ca2+]i‐dependent manner.

The facilitation of synaptic transmission showed 4–5th power dependence on the Ca2+ current facilitation, and was abolished when the Ca2+ current amplitude was adjusted to be identical.

Short‐term facilitation of Ca2+ currents predominantly mediates short‐term facilitation at synapses between PCs.

Abstract

Short‐term synaptic facilitation is critical for information processing of neuronal circuits. Several Ca2+‐dependent positive regulations of transmitter release have been suggested as candidate mechanisms underlying facilitation. However, the small sizes of presynaptic terminals have hindered the biophysical study of short‐term facilitation. In the present study, by directly recording from the axon terminal of a rat cerebellar Purkinje cell (PC) in culture, we demonstrate a crucial role of [Ca2+]i‐dependent facilitation of Ca2+ currents in short‐term facilitation at inhibitory PC–PC synapses. Voltage clamp recording was performed from a PC axon terminal visualized by enhanced green fluorescent protein, and the Ca2+ currents elicited by the voltage command consisting of action potential waveforms were recorded. The amplitude of presynaptic Ca2+ current was augmented upon high‐frequency paired‐pulse stimulation in a [Ca2+]i‐dependent manner, leading to paired‐pulse facilitation of Ca2+ currents. Paired recordings from a presynaptic PC axon terminal and a postsynaptic PC soma demonstrated that the paired‐pulse facilitation of inhibitory synaptic transmission between PCs showed 4–5th power dependence on that of Ca2+ currents, and was completely abolished when the Ca2+ current amplitude was adjusted to be identical. Thus, short‐term facilitation of Ca2+ currents predominantly mediates short‐term synaptic facilitation at synapses between PCs.

Abbreviations

- AAV

adeno‐associated virus

- AHP

afterhyperpolarization

- AP

action potential

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- CaM

calmodulin

- Cm

membrane capacitance

- DCN

deep cerebellar nuclei

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- GC

granule cell

- IN

inhibitory interneuron

- PC

Purkinje cell

- PPD

paired‐pulse depression

- PPF

paired‐pulse facilitation

- PPR

paired‐pulse ratio

- PSC

postsynaptic current

Introduction

At many synapses in the central and peripheral nervous system, repetitive activation induces short‐term plasticity of the transmission efficacy for tens of milliseconds to minutes, which has been considered to play an important role in neural information processing (Zucker & Regehr, 2002; Abbott & Regehr, 2004; Fioravante & Regehr, 2011; Regehr, 2012). Different forms of short‐term plasticity have been reported at different synapses. For example, excitatory synapses on a cerebellar Purkinje cell (PC) from a granule cell exhibit paired‐pulse facilitation (PPF) of transmission efficacy (Perkel et al. 1990; Atluri & Regehr 1996; Dittman et al. 2000), whereas those from a climbing fibre show paired‐pulse depression (PPD) (Perkel et al. 1990; Atluri & Regehr 1996; Dittman et al. 2000). Dynamic changes of presynaptic intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and the downstream process of transmitter release have been considered to mediate short‐term plasticity. Subsequent to the pioneering studies conducted at the neuromuscular junction by Katz and Miledi (1968), PPF has been extensively studied and several mechanisms have been suggested, such as temporal summation of residual Ca2+ (Katz & Miledi, 1968; Kamiya & Zucker, 1994), modification of action potential (AP) waveform (Jackson et al. 1991; Geiger & Jonas, 2000), saturation of Ca2+ buffer proteins (Neher, 1998; Rozov et al. 2001; Matveev et al. 2004), facilitated Ca2+ currents through voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels (Forsythe et al. 1998; Borst & Sakmann, 1998; Cuttle et al. 1998), recruitment of an extra pool or reluctant vesicles (Valera et al. 2012; Brachtendorf et al. 2015) and Ca2+‐dependent positive modulation of transmitter release machinery (Bertram et al. 1996; Atluri & Regehr 1998). However, the relative contribution of each mechanism to PPF still remains unclear, especially at inhibitory synapses, mainly as a result of difficulty in precisely measuring the Ca2+ dynamics and vesicular exocytosis in a presynaptic terminal (but see excitatory mossy fibre works by Vyleta & Jonas, 2014). In the present study, using direct patch clamp recording from an axon terminal of the cultured cerebellar PC, we have clarified the mechanism of PPF at GABAergic synapses between PCs.

PCs are the sole output neurons of the cerebellar cortical circuit, and they form synapses not only on deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN) neurons, but also on neighbouring PCs through axon collaterals. PC synapses on another PC show PPF upon high frequency activation (Orduz & Llano, 2007; Bornschein et al. 2013), whereas those on DCN neurons exhibit potent short‐term depression (Telgkamp & Raman, 2002; Pedroarena & Schwarz, 2003). It remains to be clarified how the PC output synapses on a PC and those on a DCN neuron show opposite forms of short‐term plasticity. Regarding the candidate mechanism for PPF, high expression of two Ca2+ buffering proteins, calbindin and parvalbumin, in a PC might possibly cause a supralinear increase of free cytosolic Ca2+ by saturation of Ca2+ buffers during repetitive stimulation, leading to facilitated transmitter release. However, this possibility was excluded by a recent study showing resistance of PPF to the genetic ablation of calbindin and parvalbumin in PCs (Bornschein et al. 2013). Thus, the mechanism of PPF at PC terminals still remains unclear. Direct patch clamp recording from PC axon terminals recently showed that frequency‐dependent attenuation of APs underlies the depression of PC output synapses on DCN neurons (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015). In the present study, using the direct recording technique from a small presynaptic terminal (1–3 μm), we attempted to clarify the mechanism of PPF at PC–PC synapses in culture. We demonstrate that the main factor driving synaptic facilitation at the PC terminals is the [Ca2+]i‐dependent facilitation of Ca2+ current (Forsythe et al. 1998; Borst & Sakmann, 1998; Cuttle et al. 1998).

Methods

Ethical approval

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the principles of UK regulations, as well as the guidelines regarding care and use of animals for experimental procedures of the National Institutes of Health, USA and Doshisha University, and were approved by the local committee for handling experimental animals in Doshisha University.

Culture

The method for preparing cerebellar neuronal culture was similar to that employed in previous studies (Kawaguchi & Hirano, 2007). Briefly, newborn rats of both sexes were decapitated and their cerebella were obtained, followed by incubation in Ca2+ and Mg2+‐free Hanks’ balanced salt solution containing 0.1% trypsin and 0.05% DNase for 15 min at 37ºC. Cells were then dissociated by trituration and seeded on poly‐d‐lysine‐coated cover slips in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/Ham's F12‐based medium, with 1% fetal bovine serum. One day after seeding, 75% of the medium was replaced with serum‐free Eagle's basal medium. One week after seeding, PCs were infected with adeno‐associated virus (AAV) vector carrying enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) under the control of CAG promoter (AAV‐CAG‐EGFP) (Kaneko et al. 2011). PCs could be visually identified by their large cell bodies and thick dendrites, as well as EGFP fluorescence that preferentially labelled PCs by relatively specific AAV (serotype 2) infection. Immunocytochemistry confirmed that almost all of EGFP‐positive neurons were positive for calbindin, a molecular marker of PCs in the cerebellum (data not shown). An axon of PC was clearly different from dendrites that have a high density of spines. We selected PC axon terminals for patch clamp recording based on the EGFP fluorescence. Each week after seeding, half of the medium was replaced with fresh one containing 4 μm cytosine β‐d‐arabino‐furamoside to inhibit glial proliferation. Electrophysiological experiments were performed 3–6 weeks after seeding.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological experiments were performed similarly to previous studies (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015) at room temperature (20–24°C). Whole‐cell patch clamp recording from a cultured PC was performed with an amplifier (EPC10; HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany) in an extracellular solution containing (in mm) 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes and 10 glucose (pH 7.3). In some experiments, 2,3‐dioxo‐6‐nitro‐1,2,3,4‐tetrahydrobenzo[f]quinoxaline‐7‐sulfonamide (NBQX, 10 μm; Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK), tetraethylammonium (2 mm) and TTX (1 μm; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Tokyo, Japan) were used to inhibit glutamatergic EPSCs, K+ channels and APs, respectively.

We searched for a synaptically connected PC pair based on axonal paths of a PC visualized by EGFP, showing clear several contacts on the soma and/or dendrites of another PC. PC pairs with a relatively short soma‐to‐soma distance (∼200 μm) were selected for the experiments, as in slice preparation (Orduz & Llano, 2007). Presynaptic PC soma was whole‐cell voltage clamped with a patch pipette (3–5 MΩ) filled with 140 (in mm) potassium‐d‐gluconate, 7 KCl, 5 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 2 ATP and 0.2 GTP. The postsynaptic PC was voltage clamped at –70 mV using a patch pipette (3–5 MΩ) filled with 147 (in mm) CsCl, 5 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 15 CsOH, 2 ATP, 0.2 GTP and 2 QX‐314. The postsynaptic PC was visualized by applying CF568 or CF633 fluorescent dye (100 μm; Biotium, Hayward, CA, USA). Synaptic transmission was triggered by depolarizing the presynaptic PC soma (−70 mV to 0 mV, 1–2 ms) and the postsynaptic currents (PSCs) were recorded from the postsynaptic PC. We analysed recordings in which the series resistance for postsynaptic PC was <25 MΩ and the leak current lower than –200 pA. The paired pulse ratio of PSCs was calculated by dividing the amplitude of the second PSC by that of the first one applied at different frequencies (200, 100, 50 and 20 Hz). The second PSC amplitude was obtained by measuring the difference between the peak and the residual current of the first PSC, which was estimated by extrapolation based on the decay time constant. The paired pulse stimulation was applied every 2 s. The time difference between the onset of presynaptic PC soma stimulation and the visually identified onset of PSC was measured as the onset delay.

For terminal recordings, EGFP‐labelled varicosities impinging on the soma or the proximal dendrites of other PC were selected. We recorded from a terminal using a patch pipette (16–18 MΩ) filled with 147 or 152 (in mm) CsCl, 10 Hepes, 2 ATP, 0.2 GTP and either 5 or 0.5 EGTA. The Ca2+ current into the presynaptic terminal was recorded in the presence of 1 μm TTX and 2 mm tetraethylammonium to avoid activation of neighbouring terminals. The effective space clamp at the PC terminal on a PC in culture was estimated by recording capacitive transients in response to a small depolarizing or hyperpolarizing pulse (10 mV) to an axon terminal. Capacitive transients at an axon terminal followed a dual exponential with time constants of 0.15 ± 0.01 ms and 3.4 ± 0.7 ms (n = 11 cells). Assuming that the terminal was connected to a cylinder shape of axon, the terminal size was estimated to be 1.5 ± 0.3 pF, and a clamped axonal region had 4.6 ± 0.8 pF of capacitance. These membrane capacitances corresponded to a terminal with a diameter of 3 μm and an axon of length 20 μm interconnected through a resistance of ∼700 MΩ. Considering the relatively sparse synaptic formation between PCs, the area controlled by the voltage command was probably confined to the patched terminal. This idea was supported by simulation of the electrical circuit consisting of a terminal and an axon. In some experiments, EGTA was replaced with 20 mm BAPTA accompanied with appropriate reduction of CsCl to adjust osmolality. Basal membrane capacitance (Cm) was 2–3 pF, and series resistance of the terminal recordings (typically 70 MΩ) was compensated for by ∼30–80%. Measurements of Cm were carried out using the sine + DC technique (Neher & Marty, 1982) implemented via Patchmaster software (HEKA). Presynaptic terminals were held at –80 mV and the sine wave (1000 Hz and peak amplitude of 30 mV) was applied on the holding potential. Because of large conductance changes during the depolarizing pulse, capacitance was usually measured between 200 and 300 ms after the pulse.

Ca2+ imaging

To record the Ca2+ increase at the presynaptic terminals, we applied CF633 (100 μm; Biotium) and either Oregon Green BAPTA‐1 (OGB‐1, 200 μm, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA; K d = 0.2 μm) or Oregon Green BAPTA‐6 (OGB‐6, 200 μm, Invitrogen; K d = 3 μm) to the soma of a granule cell (GC), an inhibitory interneuron(IN) or a PC through a patch pipette. The dyes were allowed to diffuse throughout the cell for 25 min before recording started. Axonal varicosities were identified by CF633 fluorescence. The Ca2+ increase upon an AP, which was triggered at the soma by a depolarizing pulse (0 mV, 2 ms), was detected as the fluorescence increase of OGB‐1/OGB‐6. Five to twenty trails were performed per cell, with a 1 min interval between trails. Images of PC axon terminals were obtained with a Zyla sCMOS camera (Andor Technology Ltd, Belfast, UK) and analysed with SOLIS (Andor) or Image J software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using a paired t test, an unpaired Students’ t test, the Mann–Whitney U test or ANOVA.

Results

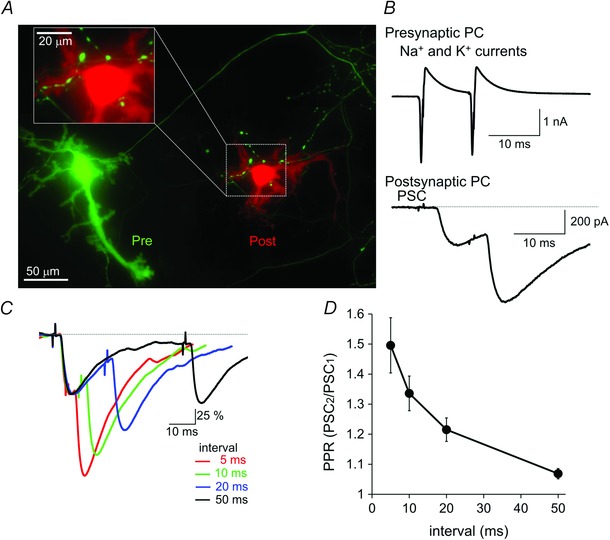

PPF of synaptic transmission at PC–PC synapses in culture

We first tested whether short‐term facilitation takes place at inhibitory synapses between cultured PCs as in slice preparation (Orduz & Llano, 2007). Some of PCs were fluorescence labelled with EGFP using AAV vector (Kaneko et al. 2011), which allowed us to identify a synaptically connected pair of PCs (Fig. 1 A). PCs tend to form synapses on a DCN neuron (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015) and synaptically connected PC–PC pairs were rarely found in culture. We performed whole‐cell patch clamp recordings from a pair of PCs that were located relatively near, as in slice preparation (Orduz & Llano, 2007), and the postsynaptic PC was visualized by fluorescence using CF568 or CF633 applied through a patch pipette. The distance from the axon hillock to the first branching point of the axon collateral was 130 ± 20 μm, and the distance between the presynaptic PC soma and the closest synapse was 530 ± 99 μm (n = 8 pairs).

Figure 1. PPF of synaptic transmission at the cultured PC–PC synapse .

A, fluorescence image of a synaptically‐connected PC–PC pair. Green: a presynaptic PC expressing EGFP. Red: a postsynaptic PC visualized by CF633 applied through a patch pipette (removed when the image acquisition). To show several synapses around the postsynaptic PC soma and proximal dendrites, the area surrounded by a white rectangle is presented as an enlarged image. B, representative traces of presynaptic Na+ and K+ currents and PSCs upon paired pulse stimulation at a 10 ms interval (depolarization pulses to 0 mV for 2 ms). Presynaptic currents through voltage‐dependent channels were isolated by subtracting the 7‐fold capacitive currents upon the 10 mV depolarization pulse. C, normalized PSC traces upon paired‐pulse stimulation at 5, 10, 20 or 50 ms intervals. D, averaged ratio of PSC amplitudes (PSC2/PSC1) is plotted against the interval of paired pulse stimulation (n = 6–7 pairs).

Both pre‐ and postsynaptic PCs were voltage clamped at −70 mV. Paired pulse stimulation consisting of two depolarization pulses (to 0 mV, 2 ms) was applied to the presynaptic PC soma (to elicit APs) at different intervals (5, 10, 20 and 50 ms) and synaptic transmission was recorded from the postsynaptic PC. The PSC was recorded as inward currents because of a high concentration of internal Cl−, and had an average amplitude of 409 ± 153 pA (n = 8 pairs with six synaptic contacts on average), onset delay of 2.6 ± 0.2 ms, 10–90% rise time of 2.0 ± 0.2 ms and half‐height width of 15 ± 2 ms. As shown in Fig. 1 B, the amplitude of the second PSC was larger than that of the first one, and the extent of facilitation depended on the stimulation interval (50 ms, 107 ± 2%; 20 ms, 122 ± 4%; 10 ms, 134 ± 6%; 5 ms, 150 ± 9%; n = 6–7 cells) (Fig. 1 C and D). The time course of PPF was comparable to that reported in slice preparation (Orduz & Llano, 2007). Thus, the facilitation property of GABAergic synapses between PCs is preserved in the dissociated culture.

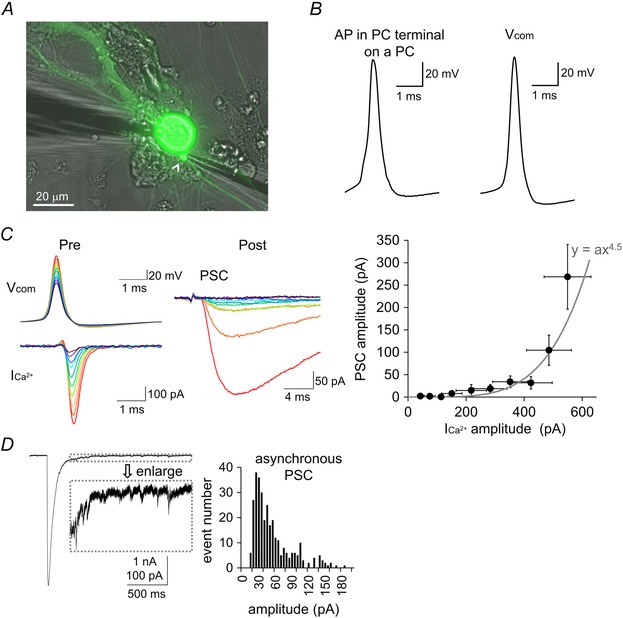

Short‐term facilitation of Ca2+ currents in a PC terminal

To study the mechanism underlying short‐term facilitation at PC–PC synapses, we directly recorded from the EGFP‐positive presynaptic terminal (1–3 μm in diameter) impinging on the soma or proximal dendrite of a PC (Fig. 2 A). By taking advantage of direct voltage clamp recording from a presynaptic terminal, we first recorded the presynaptic Ca2+ currents through voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels upon an AP and the resultant postsynaptic response. Accordingly, the terminal was stimulated by a voltage command with an AP waveform that was recorded from a PC terminal on a DCN neuron in a previous study (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015), which was similar to the AP waveform recorded from a PC terminal on a PC (Fig. 2 B). To restrict the stimulation to the patched terminal, we patch clamp recorded from a relatively isolated terminal in the presence of 1 μm TTX. Paired recordings from a PC axon terminal and a postsynaptic PC soma showed that the presynaptic AP command evoked the PSCs with mean amplitude of 116 ± 32 pA (n = 10 pairs). When the amplitude of a single AP command to the presynaptic terminal was changed to elicit different amplitudes of Ca2+ current, the amplitude of PSC also changed. As the AP command became larger in amplitude, the Ca2+ current almost linearly increased (Fig. 2 C). On the other hand, the PSC amplitude changed supralinearly, and showed 4–5th power dependenceon the Ca2+ current amplitude (Fig. 2 C). Because PCs receive inputs from many neurons, miniature PSCs were isolated by analyzing asynchronous events following a strong pulse to the terminal. Miniature PSCs, observed as asynchronous releases after a square pulse to the terminal, had a mean amplitude of 52 ± 3 pA (n = 6 pairs) (Fig. 2 D). Thus, a few synaptic vesicles are exocytosed upon the AP command, which is consistent with a previous study (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015). In addition, the amplitude of PSCs was in a reasonable range considering that a PC pair showing the mean PSC amplitude (409 pA) under somatic paired recordings had approximately six synaptic connections located at various postsynaptic compartments (Fig. 1). Taken all of these observations together, the AP voltage command to the PC axon terminal causes synaptic transmission compatible with the physiologically evoked one.

Figure 2. PC–PC synaptic transmission upon an AP voltage command at a terminal .

A, representative image for paired recordings from the presynaptic PC terminal (highlighted by a white arrowhead) and the postsynaptic PC soma. Both pre‐ and postsynaptic PCs are EGFP‐positive in this case. B, AP waveform recorded from a PC terminal impinging on a PC (left) and the AP waveform used for voltage command in the present study that was recorded from a PC terminal on a DCN (right). C, left: representative traces of different amplitudes of AP commands (V com), the Ca2+ currents (ICa2+) in a presynaptic PC terminal and the PSCs simultaneously recorded from the postsynaptic PC. Right: PSC amplitudes upon various amplitudes of AP commands were plotted against the ICa2+ amplitudes. The grey line represents the 4.5th power relationship between x‐ and y‐axis. D, left: a representative trace of PSC evoked by the 5 ms depolarization pulse to 0 mV in the presynaptic terminal. For hundreds of milliseconds after the large PSC, asynchronous events could be observed. These events were used for sampling mPSCs because this is the most reliable way of collecting miniature events from a given presynaptic PC terminal. Right: amplitude histogram of asynchronous PSCs. Pooled data from six cells are shown.

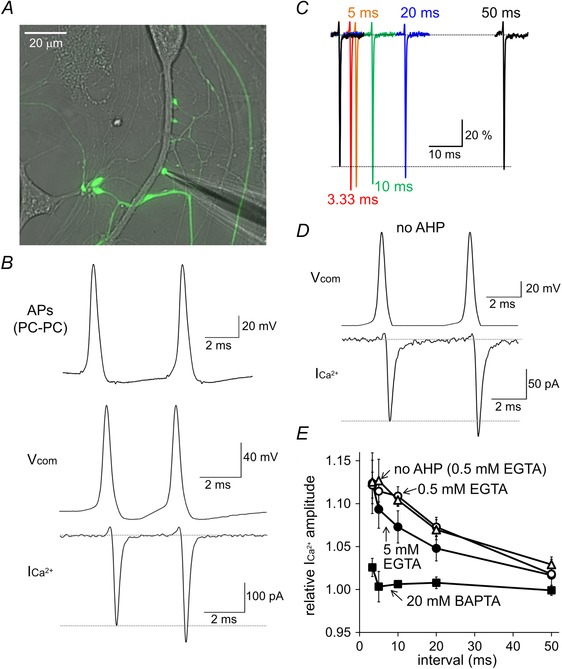

To examine whether the Ca2+ currents are modulated by high‐frequency AP arrivals, we stimulated the presynaptic terminal by paired pulses of the AP command (Fig. 3 A). As shown in Fig. 3 B, the waveform of an AP pair recorded from a PC terminal upon somatic high frequency stimulation showed afterhyperpolarization (AHP) between two APs. Therefore, we used a similar voltage command with AHP for the paired pulse stimulation of the PC terminal, unless otherwise stated. The amplitude of Ca2+ current upon the second AP waveform was larger than that upon the first one, showing PPF dependent on the stimulation interval (3.33 ms, 112 ± 2%; 5 ms, 111 ± 2%; 10 ms, 111 ± 1%; 20 ms, 107 ± 1%; 50 ms, 102 ± 2%) (Fig. 3 B, C and E). There are two possible candidate mechanisms for the Ca2+ current facilitation upon the paired‐pulse stimulation of the AP command. One is that AHP between the first and the second AP commands may recover some fractions of voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels from inactivation at resting membrane potential (Brachaw et al. 1997), leading to increased availability of Ca2+ channels at the second stimulation. To test this possibility, we omitted AHP between two AP commands and measured the PPF of Ca2+ currents (Fig. 3 D). As shown in Fig. 3 D and E, the PPF of Ca2+ currents without AHP was similar to that observed in the presence of AHP (3.33 ms, 113 ± 3%; 5 ms, 113 ± 2%; 10 ms, 109 ± 1%; 20 ms, 107 ± 1%; 50 ms, 103 ± 1%). The other candidate mechanism is the Ca2+‐dependent facilitation of Ca2+ current, which is caused by direct modulation of voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels by Ca2+‐binding proteins such as calmodulin (CaM) and neuronal Ca2+ sensor (Catterall & Few, 2008; Ben‐Johny & Yue, 2014). To test this possibility, the PPF of Ca2+ current was measured in the presence of higher concentration of Ca2+ chelator in the intracellular solution. Increase of intracellular concentration of EGTA (from 0.5 mm to 5 mm) did not suppress the PPF of Ca2+ current at short intervals but tended to accelerate the recovery of the PPF of Ca2+ current (3.33 ms, 112 ± 4%; 5 ms, 109 ± 2%; 10 ms, 107 ± 2%; 20 ms, 105 ± 1%; 50 ms, 102 ± 0%) (Fig. 3 E). Application of BAPTA (20 mm) was necessary to completely abolish the Ca2+ current facilitation (3.33 ms, 103 ± 1%; 5 ms, 100 ± 2%; 10 ms, 101 ± 0%; 20 ms, 101 ± 1%; 50 ms, 100 ± 1%) (Fig. 3 E). Taking all of these results together, it was suggested that the Ca2+ current through voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels is facilitated upon high‐frequency stimulation depending on the increase in [Ca2+]i.

Figure 3. Ca2+‐dependent facilitation of presynaptic Ca2+ currents at PC–PC synapses .

A, image of direct patch clamp recording from an EGFP‐positive axon terminal on a proximal dendrite of another PC. B, pair of APs recorded from a PC terminal on a PC (top), representative traces of paired‐pulse voltage commands with an AP waveform (middle, V com) and the resultant Ca2+ currents (bottom, ICa2+). C, normalized Ca2+ currents upon paired‐pulse AP commands at 3.33, 5, 10, 20 or 50 ms interval. The dotted line represents the average peak amplitude of the first Ca2+ current. D, representative traces of the paired‐pulse voltage command with an identical AP waveform without AHP and the resultant Ca2+ currents. E, averaged Ca2+ current facilitation upon various intervals of paired‐pulse AP waveforms in the presence of 0.5 or 5 mm EGTA or of 20 mm BAPTA.The data obtained without AHP of the AP waveform in the presence of 0.5 mm EGTA are also shown (no AHP) [n = 4 (0.5 mm EGTA, 5 mm EGTA and 20 mm BAPTA); n = 5 (no AHP)].

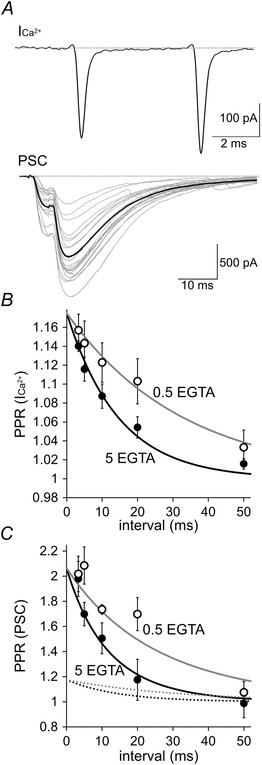

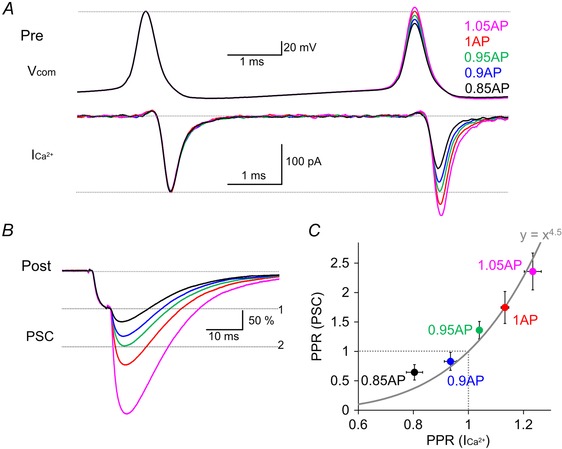

PPF of synaptic transmission is determined by that of Ca2+ currents

Taking into consideration that transmitter release is highly sensitive to the [Ca2+]i (Fig. 2 C), the PPF of Ca2+ current might be a powerful mechanism leading to the short‐term facilitation of synaptic transmission. To study the quantitative relationship between the PPF of Ca2+ current and the PPF of synaptic transmission, we performed paired recordings from a presynaptic PC axon terminal and a postsynaptic PC soma. Paired‐pulse AP waveforms with different intervals caused facilitation in both the presynaptic Ca2+ current amplitude (3.33 ms, 116 ± 2%; 5 ms, 114 ± 2%; 10 ms, 112 ± 2%; 20 ms, 110 ± 2%; 50 ms, 103 ± 2%) and synaptic transmission (3.33 ms, 202 ± 14%; 5 ms, 209 ± 8%; 10 ms, 174 ± 3%; 20 ms, 170 ± 20%; 50 ms, 108 ± 14%) (Fig. 4 A–C). The facilitation of PSC could be fitted to the 4–5th power of the facilitation of Ca2+ currents (Fig. 4 B and C). When the recovery from Ca2+ current facilitation was accelerated by the presence of 5 mm intracellular EGTA (3.33 ms, 114 ± 1%; 5 ms, 112 ± 1%; 10 ms, 109 ± 1%; 20 ms, 105 ± 1%; 50 ms, 102 ± 1%), the PPF of PSC also recovered faster (3.33 ms, 198 ± 14%; 5 ms, 170 ± 9%; 10 ms, 151 ± 12%; 20 ms, 118 ± 16%; 50 ms, 99 ± 11%), showing 4–5th power dependence of the PSC facilitation on the Ca2+ current facilitation (Fig. 4 C). Thus, the PPF of PSC was tightly correlated with that of the Ca2+ currents. The time course of the PSC facilitation observed by paired terminal‐soma recordings in the presence of 5 mm rather than 0.5 mm EGTA was similar to that observed under paired soma–soma recordings from synaptically‐connected PCs (Fig. 1). Thus, the strong Ca2+ buffering capacity of PC terminals containing calbindin and parvalbumin (Bornschein et al. 2013) might be somewhat similar to the situation containing a millimolar‐order of EGTA.

Figure 4. Tight coupling of Ca2+ current facilitation and synaptic facilitation at PC–PC synapses .

A, representative traces of ICa2+ (average of 20 traces) and PSCs upon paired pulse voltage commands consisting of an identical AP waveform. Black PSC trace is the average of 20 PSC traces shown in grey. B and C, averaged PPR of ICa2+ (B) and that of PSC (C) in the presence of intracellular 0.5 or 5 mm of EGTA are plotted against the interstimulus interval. Grey or black continuous lines in (C) are the 4.5th power of ICa2+ (shown as dotted lines, which are same as continuous lines in B) [n = 6 pairs (5 mm EGTA); n = 4 pairs) (0.5 mm EGTA)].

To study the causal relationship between the PPF of Ca2+ current and that of PSC, we next changed the amplitude of Ca2+ currents during the second AP by systematically altering the AP amplitude (to 1.05, 1, 0.95, 0.9 or 0.85 times) (Fig. 5 A). As the amplitude of the second AP command decreased, that of the Ca2+ current was also decreased (1.05AP, 123 ± 3%; 1AP, 113 ± 1%; 0.95AP, 104 ± 1%; 0.9AP, 93 ± 2%; 0.85AP, 80 ± 3%) (Fig. 5 A and C). As a result of the decreased Ca2+ current, PPF of synaptic transmission changed into PPD (1.05AP, 236 ± 31%; 1AP, 175 ± 27%; 0.95AP, 136 ± 15%; 0.9AP, 83 ± 15%; 0.85AP, 64 ± 13%)(Fig. 5 B and C). When the paired‐pulse ratio (PPR) of PSC was plotted against that of Ca2+ current, their relation matched to the 4–5th power dependence (Fig. 5 C). This result, together with that shown in Fig. 4, indicates that the paired pulse ratio of PSCs critically depends on the 4–5th power of Ca2+ current, and the PSC amplitude does not change when the presynaptic Ca2+ current is identical between the first and second pulses. Thus, it appears that the PPF of synaptic transmission is predominantly brought about by the PPF of Ca2+ currents at the PC–PC synapses.

Figure 5. ICa2+ facilitation determines the synaptic facilitation .

A and B, representative traces of voltage commands consisting of paired‐pulse AP waveforms (V com) and the Ca2+ currents (ICa2+) in a presynaptic PC terminal (A) and of PSCs (B). The second AP amplitude was changed (1.05, 1, 0.95, 0.9 or 0.85 times that of the first) to alter the second Ca2+ current amplitude. The PSC amplitudes were normalized to the first one. C, the averaged PPR of PSCs was plotted against that of ICa2+. The data were obtained from (A) and (B) (n = 6 pairs).

Marginal residual Ca2+ in a PC terminal

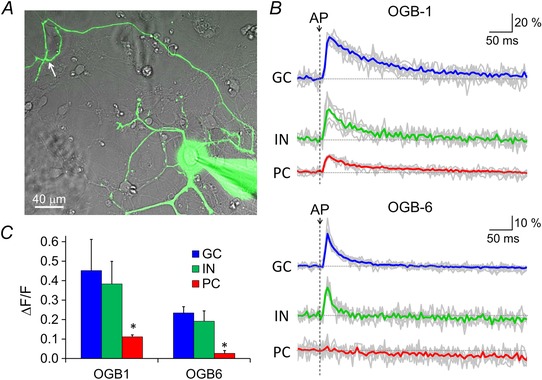

The above results precluded the contribution of other mechanisms of facilitation, such as the residual Ca2+ hypothesis, which suggested that temporal summation of [Ca2+]i during paired AP arrivals increases the transmitter release probability (Katz & Miledi, 1968). To test this issue further, we performed Ca2+ imaging using OGB‐1 (200 μm, K d = 0.2 μm) or OGB‐6 (200 μm, K d = 3 μm) applied into the soma through a patch pipette (Fig. 6 A). After 25 min of dye diffusion, we evoked an AP by applying a single depolarization pulse in the PC soma (to 0 mV, 2 ms) and the fluorescence changes in the axonal varicosities were recorded. The Ca2+ influx into the varicosity resulted in the increase in fluorescence signal of OGB‐1 or OGB‐6, and the relative fluorescence increase (ΔF/F) reflected the amplitude of Ca2+ increases. The ΔF/F upon a single AP was very small in a PC terminal (OGB‐1, 0.11 ± 0.01) compared to the varicosities of an IN (0.38 ± 0.12) or a GC (0.45 ± 0.16). An IN is known to express parvalbumin but not calbindin, whereas a GC lacks both but expresses calretinin (Bastianelli, 2003). The ΔF/F was extremely small in a PC terminal when using OGB‐6 (PC: 0.03 ± 0.01; IN: 0.19 ± 0.05; GC: 0.23 ± 0.03) (Fig. 6 B and C). Thus, the residual [Ca2+]iincrease is tiny in a PC terminal compared to axon terminals of an IN or a GC. The small change of OGB‐1 and OGB‐6 fluorescence upon a single AP in a PC terminal corresponded to an∼10–20 nm of [Ca2+]i increase, which is similar to the value estimated in previous slice studies (Schmidt et al. 2003; Orduz & Llano, 2007). A high expression level of Ca2+ buffer proteins, calbindin and parvalbumin, is probably responsible for the low residual [Ca2+]i increase (Bornschein et al. 2013). Considering our previous estimate of local [Ca2+]i during a single AP as 5–10 μm in a PC terminal (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015), the residual Ca2+ increase by 20 nm is estimated to increase the transmitter release by ∼1% assuming 4–5th power Ca2+ dependence. Thus, in line with the idea that the PPF of PSC is predominantly mediated by that of Ca2+ current, the temporal summation of residual Ca2+probably plays no role in the PPF at PC–PC synapses.

Figure 6. Residual Ca2+ increase at PC terminals .

A, representative fluorescence image of a PC loaded with 200 μm OGB‐1. At an axon varicosity (highlighted by an white arrow), fluorescence change was measured before and after the action potential evoked at the soma. B, time courses of normalized fluorescence intensity change of OGB‐1 or OGB‐6 recorded from an axon varicosity from a PC, an IN or a GC. Representative traces for each condition are also shown in grey. C, ΔF/F upon single AP in a GC (n = 6 cells for OGB‐1 and 8 for OGB‐6), IN (n = 5 cells for OGB‐1 and 6 for OGB‐6) or PC (n = 7 cells for OGB‐1 and 5 for OGB‐6). *P < 0.05.

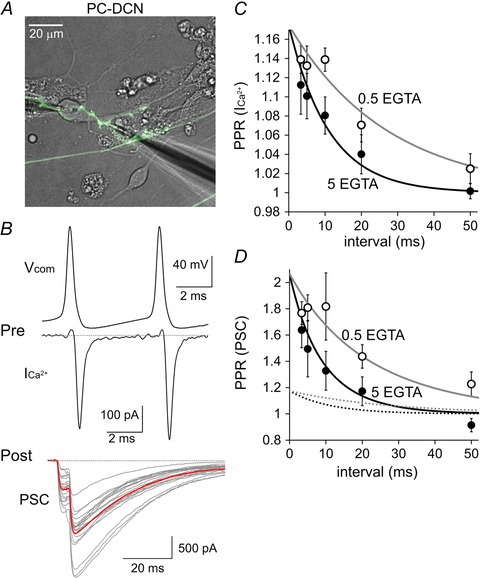

Release properties of PC axon terminals on a PC similar to those on a DCN neuron

The above results indicated that the facilitative property of PC synapses on another PC is predominantly mediated by Ca2+‐dependent facilitation of Ca2+ currents through voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels. On the other hand, PC synapses on a DCN neuron show depression upon high frequency activation (Telgkamp & Raman, 2002) as a result of AP attenuation around terminals (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015). To study the mechanism underlying the target‐dependent opposite forms of short‐term plasticity, we next examined whether the facilitation of Ca2+ current and the resultant enhancement of transmitter release is a unique mechanism of PC synapses on another PC but not on DCN neurons. As shown in Fig. 7, cultured PC axons preferentially formed high density of synapses around a type of neuron, which is estimated to be a potential DCN neuron based on morphology, electrophysiological properties and molecular marker expression (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015). We performed paired whole‐cell recordings from the presynaptic PC axon terminal and the postsynaptic DCN cell. Similar to PC–PC synapses, paired‐pulse voltage commands of an AP waveform to the presynaptic terminal caused facilitation of presynaptic Ca2+ currents (3.33 ms interval, 114 ± 1%; 5 ms, 113 ± 2%; 10 ms, 114 ± 1%; 20 ms, 107 ± 2%; 50 ms, 103 ± 2%) (Fig. 7 B and C). Consequently, the synaptic transmission also exhibited PPF rather than depression (3.33 ms, 177 ± 9%; 5 ms, 181 ± 10%; 10 ms, 182 ± 26%; 20 ms, 144 ± 9%; 50 ms, 123 ± 9%) (Fig. 7 B and D). Interestingly, the extents of facilitation of Ca2+ current and that of PSC were similar to those observed at PC–PC synapses, and the relationship between facilitation of Ca2+ currents and that of PSCs also showed 4–5th power dependence. In addition, the Ca2+ current facilitation at PC synapses on DCN cells was shortened by increasing the EGTA concentration (3.33 ms interval, 111 ± 3%; 5 ms, 110 ± 2%; 10 ms, 108 ± 2%; 20 ms, 104 ± 2%; 50 ms, 100 ± 1%), as for PC–PC synapses (Fig. 7 C). Consequently, the PPF of synaptic transmission was also shortened (3.33 ms, 164 ± 13%; 5 ms, 149 ± 21%; 10 ms, 133 ± 15%; 20 ms, 117 ± 11%; 50 ms, 91 ± 5%) (Fig. 7 D). Thus, the Ca2+‐dependent facilitation of Ca2+ current causing short‐term facilitation is a common feature in PC axon terminals, irrespective of the target neuron type, as long as identical APs are elicited.

Figure 7. Ca2+‐dependent PPF of Ca2+ currents and PSCs at PC–DCN synapses .

A, representative image for paired recordings from a presynaptic PC terminal and a postsynaptic DCN neuron. B, representative traces of the paired‐pulse AP command (V com) and the Ca2+ currents (ICa2+) in a presynaptic PC terminal (top) and the PSCs simultaneously recorded from a postsynaptic DCN neuron (bottom). Red trace is the averaged PSC from 20 PSC traces (grey). C and D, averaged PPR of ICa2+ (C) and that of PSC (D) in the presence of intracellular 0.5 or 5 mm of EGTA are plotted against the interstimulus interval. Black or grey lines in (D) are the 4.5th power of ICa2+ (shown as dotted lines, which is same as the continuous lines in C) (n = 5 and 6 for 5 and 0.5 mm EGTA, respectively).

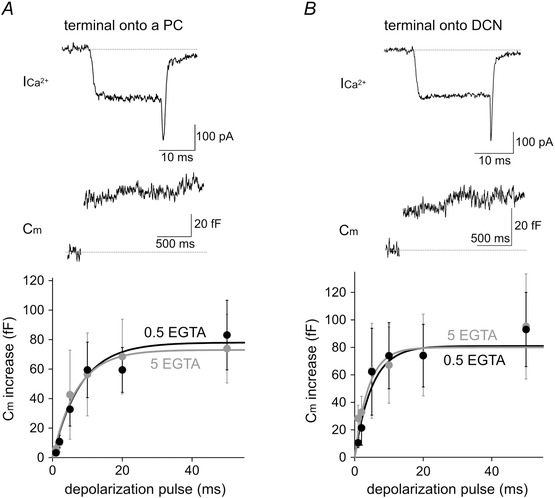

In addition, the size of total readily releasable pool of synaptic vesicles was also similar when measured by a change of Cm. Ca2+ influx into the PC terminal caused by different durations (1–50 ms) of square depolarization pulses increased Cm reflecting exocytosis of synaptic vesicles (Fig. 8). The amplitude of Cm increase could be fitted by a single exponential curve. The PC–PC presynaptic terminal showed 83 ± 24 fF increase upon the 50 ms depolarization pulse, whereas the PC–DCN terminal showed 93 ± 27 fF (P > 0.39). Thus, assuming the Cm of single synaptic vesicle to be ∼70 aF (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015), ∼1000 releasable synaptic vesicles are contained in each terminal. Consistent with the previous data (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015), the Cm increase was not suppressed by increasing the intracellular EGTA concentration from 0.5 to 5 mm in PC terminals (74 ± 23 fF at terminals on PC and 95 ± 38 fF on DCN neuron, respectively) (Fig. 8), suggesting that transmitter release is tightly coupled to the Ca2+ influx.

Figure 8. Cm increases at a PC terminal on a PC or DCN neuron .

Top: representative traces of presynaptic ICa2+ and Cm recorded from a PC terminal on a PC (A) or that on a DCN neuron (B). Bottom: Cm increases recorded with intracellular 0.5 or 5 mm EGTA were plotted against the depolarization pulse duration [n = 7 (0.5 mm EGTA) and n = 13 (5 mm EGTA) terminals on a PC; n = 7 (0.5 mm EGTA) and n = 5 (5 mm EGTA) terminals on a DCN neuron].

Taken all of these results together, we conclude that the Ca2+‐dependent transmitter release mechanisms and the facilitative property relying on the Ca2+‐dependent facilitation of Ca2+ current are common in all PC axon terminals. However, because of AP attenuation, PC–DCN synapses exhibit depression rather than facilitation (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015).

Discussion

By direct patch clamp recording from inhibitory presynaptic terminals of cultured cerebellar PCs, we have studied a mechanism of PPF at GABAergic synapses between PCs. This technique allowed us to reveal that (1) voltage‐gated Ca2+ current was facilitated in a Ca2+‐dependent manner in PC axon terminals and (2) short‐term facilitation of Ca2+ currents almost exclusively determines the short‐term facilitation of synaptic transmission between PCs. We conclude that PC–PC synapses show short‐term facilitation of transmitter release predominantly depending on the Ca2+‐dependent Ca2+ current facilitation. Our data further indicated that the synaptic facilitating property relying on the Ca2+ current facilitation was common at PC output synapses, irrespective of the target cells, when identical paired AP commands were applied to the terminal.

Ca2+ current facilitation

In the present study, we demonstrated that Ca2+ current in PC axon terminals is facilitated by ∼10% in a Ca2+‐dependent manner upon high‐frequency paired APs. Previous studies on PPF at PC–PC synapses in slice preparation could not detect facilitated increase in [Ca2+]i by fluorescence imaging (Orduz & Llano, 2007; Bornschein et al. 2013). Considering the tiny fluorescence change by single AP‐triggered Ca2+ influx as a result of the strong Ca2+ buffering (Fig. 6), it appears to be hard to detect a small facilitation of Ca2+ influx of ∼10% by Ca2+ imaging. Similar Ca2+‐dependent facilitation of Ca2+ currents has been reported at glutamatergic presynaptic terminal in the calyx of Held (Forsythe et al. 1998; Borst & Sakmann, 1998; Cuttle et al. 1998), which partly contributes to short‐term facilitation of synaptic transmission when the basal release probability is lowered (Felmy et al. 2003; Müller et al. 2008; Hori & Takahashi, 2009).

CNS neurons have several types of voltage‐gated Ca2+ channels, such as N, L, P/Q and R‐types. Among these, mature PCs express P/Q type of Ca2+ channels abundantly, and its genetic ablation results in severe ataxia (Jun et al. 1999) and reduced synaptic facilitation (Inchauspe et al. 2004). The detailed mechanism of Ca2+‐dependent Ca2+ current facilitation has been studied using a heterologous expression system (Lee et al. 2003; DeMaria et al. 2001; Catterall & Few, 2008; Ben‐Johny & Yue, 2014). Similar to other types of Ca2+ channels, the P/Q type has a CaM binding site. The Ca2+ binding to C‐lobe of CaM is reported to rapidly (<1 ms) facilitate the Ca2+ currents by increasing the channel open probability. On the other hand, CaM bound with Ca2+ at N‐lobe has been shown to inactivate the P/Q type Ca2+ channels relatively slowly (tens of milliseconds). In addition, neuronal Ca2+ sensor protein was also suggested to mediate the Ca2+‐dependent facilitation of Ca2+ currents in a similar manner to CaM but with stronger Ca2+ affinity (Tsujimoto et al. 2002). If the Ca2+ current is facilitated by a mechanism coupled loosely with the Ca2+ influx, an increase of exogenous buffering by EGTA is expected to weaken the Ca2+ current facilitation (Neher, 1998). However, as shown in Figs 3 and 7, a high concentration of EGTA accelerated the recovery but did not change the peak amplitude of Ca2+ current facilitation in PC terminals (Alturi & Regehr, 1998). Thus, the Ca2+ current facilitation appears to be tightly coupled with local Ca2+ influx, which is consistent with the idea that Ca2+‐binding to CaM associated with the P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels at rest contributes to Ca2+ current facilitation (Erickson et al. 2001; Ben‐Johny & Yue, 2014).

Interestingly, the Ca2+ current facilitation by Ca2+/CaM is specific to P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels, and other types of Ca2+ channels are rather inactivated by Ca2+/CaM association (Catterall & Few, 2008; Ben‐Johny & Yue, 2014). The types of Ca2+ channels contributing to transmitter release in presynaptic terminals developmentally change at some synapses, including PC output synapses, excitatory synapses in the calyx of Held and thalamic inhibitory synapses (Iwasaki et al. 2000; Miki et al. 2013). Thus, short‐term plasticity by Ca2+ channel modulation might also developmentally change. Indeed, in contrast to PPF at synapses between PCs in slices prepared from postnatal day 7–19 mice (Orduz & Llano, 2007; Bornschein et al. 2013), PPD was observed in younger mice (postnatal day 4–6 mice) (Watt et al. 2009). A developmental switch of Ca2+ channels in the PC terminal from mixture of N‐, R‐ and P/Q‐type to P/Q‐type‐specific (Iwasaki et al. 2000) might be responsible for the age‐dependent differences in short‐term plasticity.

Mechanisms of PPF

The averaged PSC amplitude (409 pA) at a PC pair with approximately six synaptic contacts and the miniature PSC amplitude (52 pA) imply that one or two synaptic vesicles are exocytosed at each presynaptic terminal. This estimation is in accordance with the number of exocytosed vesicles (∼2) based on the PSC amplitude (116 pA) upon an AP command at single terminal. Thus, the release probability per synapse is almost 1 in PC terminals. On the other hand, the Cm measurement suggests that ∼1000 vesicles are readily releasable in a single terminal within 10 ms if a strong Ca2+ increase takes place (Fig. 8). Thus, the release probability per each RRP vesicle is estimated to be very low (∼0.2%). It should be noted that the number of synaptic vesicles exocytosed upon a square depolarization pulse might be larger than the releasable vesicle pool upon high frequency APs. In addition, if the vesicle replenishment is very fast (i.e. several milliseconds) (Valera et al. 2012; Brachtendorf et al. 2015), the capacitance measurement might overestimate the RRP size by 2‐ to 3‐fold. In any cases, a PC axon terminal has a large amount of RRP vesicles and the release probability of each release‐ready vesicle upon an AP is low. The large RRP and low release probability are typical properties of facilitating synapses (Dittman et al. 2000) and the increase of either RRP size or release probability leads to PPF.

Paired recordings from a PC axon terminal and a postsynaptic PC soma demonstrated that PPF is almost exclusively mediated by the Ca2+‐dependent facilitation of Ca2+ current into a presynaptic terminal (Figs 4 and 5). Using the expression of mutant Ca2+ channels in cultured superior cervical ganglion neurons, a tight correlation between Ca2+ current modulation and short‐term plasticity was demonstrated (Mochida et al. 2008). When the release probability is decreased to suppress depletion of the releasable synaptic vesicle pool, the calyx of Held synapses also show short‐term facilitation, ∼50% of which relies on the Ca2+‐dependent Ca2+ current facilitation (Felmy et al. 2003; Müller et al. 2008; Hori & Takahashi, 2009). Thus, Ca2+‐dependent Ca2+ current facilitation may contribute to synaptic facilitation at many synapses. However, our data do not necessarily exclude other mechanisms suggested in PPF at other synapses. The residual Ca2+ hypothesis is the simplest one arising from studies on short‐term facilitation at the neuromuscular junction (Katz & Miledi, 1968). It was postulated that the summation of residual Ca2+ remaining in the cytoplasm after the first AP and the local Ca2+ during the following AP contributes to the facilitated transmitter release as a result of 4th power dependence of transmitter release on [Ca2+]i. However, in most cases, the residual [Ca2+]i increase is estimated to be too small compared to the local [Ca2+]i to account for facilitation. This is particularly the case for PC axon terminals (Fig. 6) (Orduz & Llano, 2007), presumably as a result of very high expression of high affinity Ca2+ buffer calbindin. We estimated that the residual [Ca2+]i increase accounts for only 1–2% facilitation at PC–PC synapses.

Saturation of mobile Ca2+ buffer proteins in presynaptic terminals has also been considered as a candidate mechanism for short‐term facilitation. If Ca2+ entering into the terminal upon the first AP remains bound to the large part of Ca2+ buffer molecules, free [Ca2+]i is expected to become higher upon the following APs, leading to larger transmitter release. Indeed, calbindin was shown to contribute to the PPF at inhibitory synapses in the cerebral cortex and excitatory mossy fibre–CA3 synapses in the hippocampus (Blatow et al. 2003). On the other hand, despite extensive expression of calbindin in cerebellar PCs throughout the cell, it was recently demonstrated that PPF at PC–PC synapses was not affected by the genetic ablation of either calbindin or parvalbumin, another Ca2+ buffer protein (Bornschein et al. 2013). The lack of effect by calbindin ablation on PPF might be a result of the limited amount of Ca2+ influx into the presynaptic terminal upon a single AP (half‐width of ∼0.4 ms) (Fig. 3), which might be far from saturating the abundant calbindin. Also, the buffer saturation model requires loose coupling between Ca2+ channels and vesicles (Neher 1998; Rozov et al. 2001; Vyleta and Jonas, 2014), which is not the case at this (Fig. 8) and other inhibitory synapses (Bucurenciu et al. 2008).

Another hypothesis is that Ca2+ causes facilitation acting at presynaptic release sensors (Atluri & Regehr, 1998; Bertram et al. 1996; Regehr, 2012). If there is a Ca2+‐binding site for release with high Ca2+ affinity and slow kinetics, the site is expected to be occupied with Ca2+ during the small increase of residual Ca2+, resulting in facilitated release upon the following stimulation. However, the identity of the molecule playing this role remains obscure. Using a kinetic simulation based on the five‐site Ca2+ sensor model (Schneggenburger & Neher, 2000), the slow and high‐affinity Ca2+ sensor for vesicular release was suggested to underlie the PPF observed at PC–PC synapses (Bornschein et al. 2013). By contrast, we now show that the PPF of PSCs is suppressed when the amplitude of Ca2+ current upon the second AP is identical to that upon the first (Fig. 5), indicating that the first Ca2+ influx exerts little positive effect on the release machinery remaining at the time of next AP arrival. Alternatively, we demonstrate that the Ca2+‐dependent Ca2+ current facilitation plays a role as a ‘Ca2+ sensor’ for the PPF at PC–PC synapses.

Activity‐dependent recruitment of an extra pool or reluctant vesicles to the RRP is also a possible mechanism for PPF (Valera et al. 2012; Brachtendorf et al. 2015). However, our Cm measurement data showing the uniform releasable vesicle pool in PC terminals imply that RRP size change may not be implicated in the PPF at PC–PC synapses.

Target‐dependent plasticity and physiological implication

We demonstrated that the Ca2+‐dependent facilitation of Ca2+ currents and the resultant synaptic short‐term facilitation are a common property of PC terminals irrespective of their target neurons (i.e. another PC or DCN cells) when the amplitudes of APs are identical (using AP commands). In accordance with a previous study on PC terminals on a DCN neuron (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015), PC terminals on another PC also exhibited the large readily releasable synaptic vesicle pool (∼1000 vesicles) and the low release probability (<1%) upon an AP arrival, which are typical properties of facilitating synapses (Dittman et al. 2000). However, PC–PC synapses exhibit short‐term facilitation (Orduz & Llano, 2007; Bornschein et al. 2013), whereas PC–DCN synapses undergo short‐term depression in situ (Telgkamp & Raman, 2002). These apparently opposite directions of plasticity dependent on the target neurons can simply be explained by the difference in AP conduction fidelity. Direct recordings from an axon and/or a terminal previously demonstrated that AP amplitudes attenuated around axon terminals on DCN neurons located far from the PC soma in both culture and slice preparation (Kawaguchi & Sakaba, 2015). On the other hand, previous studies have shown that axonal AP conduction from the soma to the proximal region of axon is reliable up to 200 Hz (Khaliq & Raman, 2005; Monsivais et al. 2005). Consistently, our preliminary data suggest that an AP train at 100 Hz faithfully propagates from the soma to the proximal terminal on a PC with little attenuation of amplitude (Takeshi Sakaba and Shin‐ya Kawaguchi, unpublished observation). Consequently, the PC–PC synapses exhibit short‐term facilitation through the facilitated Ca2+ current. On the other hand, taking the 4th power dependence of synaptic transmission on the Ca2+ current (Fig. 2) into consideration, a small decrease of Ca2+ influx caused by a slight AP amplitude change has a large impact on synaptic efficacy, converting the intrinsically facilitating synapses to depressing synapses at PC–DCN synapses.

Target‐dependent short‐term synaptic plasticity has been reported at various synapses, such as those in neocortex, cerebellum and hippocampus (Markram et al. 1998; Rozov et al. 2001; Koester & Johnston, 2005; Pelkey et al. 2006; Beierlein et al. 2007; Bao et al. 2010). For example, excitatory synapses from a cortical pyramidal neuron on basket cells exhibit short‐term depression, whereas those on Martinotti cells show facilitation (Markram et al. 1998). It is generally assumed that synapses usually contain both the mechanisms for facilitation and those for depression, and transmitter release probability is considered to determine which of the two mechanisms prevails. Fluorescence imaging techniques have shown that the facilitating presynaptic varicosities tend to show a small Ca2+ increase and low synaptic release probability, whereas the depressing ones show larger Ca2+ transients and higher release probability (Koester & Johnston, 2005). Considering the large impact of AP amplitude on the presynaptic Ca2+ influx and the resultant synaptic transmission, we suggest that slight differences of membrane excitability in presynaptic terminals may also play a role in the target‐dependent plasticity. To test this idea at various synapses in the future, direct recording from the terminals and/or development of voltage‐sensitive dyes are essential (Hoppa et al. 2014; Vyleta & Jonas, 2014).

Additional Information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author contributions

SK and TS designed the study. FD and SK performed the experiments. FD, TS and SK interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the JSPS/MEXT, Japan (KAKENHI grant numbers 15K06722 and 15KT0082 to SK; 15H04261, 15K14321, 26110720 and Core‐to‐Core Program A Advanced Research Networks to TS) and the Naito Science Foundation to SK.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Tomoyuki Takahashi and Dr Mitsuharu Midorikawa for critically reading the manuscript and for making helpful comments.

References

- Abbott LF & Regehr WG (2004). Synaptic computation. Nature 431, 796–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri PP & Regehr WG (1996). Determinants of the time course of facilitation at the granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci 16, 5661–5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atluri PP & Regehr WG (1998). Delayed release of neurotransmitter from cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci 18, 8214–8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao J, Reim K & Sakaba T (2010). Target‐dependent feedforward inhibition mediated by short‐term synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum. J Neurosci 30, 8171–8179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastianelli E (2003). Distribution of calcium‐binding proteins in the cerebellum. Cerebellum 2, 242–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben‐Johny M & Yue DT (2014). Calmodulin regulation (calmodulation) of voltage‐gated calcium channels. J Gen Physiol 143, 679–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein M, Fioravante D & Regehr WG (2007). Differential expression of posttetanic potentiation and retrograde signaling mediate target‐dependent short‐term synaptic plasticity. Neuron 54, 949–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram R, Sherman A & Stanley EF (1996). Single‐domain/bound calcium hypothesis of transmitter release and facilitation. J Neurophysiol 75, 1919–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornschein G, Arendt O, Hallermann S, Brachtendorf S, Eilers J & Schmidt H (2013). Paired‐pulse facilitation at recurrent Purkinje neuron synapses is independent of calbindin and parvalbumin during high‐frequency activation. J Physiol 591, 3355–3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JG & Sakmann B (1998). Facilitation of presynaptic calcium currents in the rat brainstem. J Physiol 513, 149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatow M, Caputi A, Burnashev N, Monyer H & Rozov A (2003). Ca2+ buffer saturation underlies paired pulse facilitation in calbindin‐D28k‐containing terminals. Neuron 38, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchaw JL, Banks MI & Jackson MB (1997). Ca2+‐ and voltage‐dependent inactivation of Ca2+ channels in nerve terminals of the neurohypophysis. J Neurosci 17, 5772–5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brachtendorf S, Eilers J & Schmidt H (2015). A use‐dependent increase in release sites drives facilitation at calretinin‐deficient cerebellar parallel‐fiber synapses. Front Cell Neurosci. 9, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucurenciu I, Kulik A, Schwaller B, Frotscher M & Jonas P (2008). Nanodomain coupling between Ca2+ channels and Ca2+ sensors promotes fast and efficient transmitter release at a cortical GABAergic synapse. Neuron 57, 536–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA & Few AP (2008). Calcium channel regulation and presynaptic plasticity. Neuron 59, 882–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuttle MF, Tsujimoto T, Forsythe ID & Takahashi T (1998). Facilitation of the presynaptic calcium current at an auditory synapse in rat brainstem. J Physiol 512, 723–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMaria CD, Soong TW, Alseikhan BA, Alvania RS & Yue DT (2001). Calmodulin bifurcates the local Ca2+ signal that modulates P/Q‐type Ca2+ channels. Nature 411, 484–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittman JS, Kreitzer AC & Regehr WG (2000). Interplay between facilitation, depression, and residual calcium at three presynaptic terminals. J Neurosci 20, 1374–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MG, Alseikhan BA, Peterson BZ & Yue DT (2001). Preassociation of calmodulin with voltage‐gated Ca(2+) channels revealed by FRET in single living cells. Neuron 31, 973–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felmy F, Neher E & Schneggenburger R (2003). Probing the intracellular calcium sensitivity of transmitter release during synaptic facilitation. Neuron 37, 801–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioravante D & Regehr WG (2011). Short‐term forms of presynaptic plasticity. CurrOpinNeurobiol 21, 269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID, Tsujimoto T, Barnes‐Davies M, Cuttle MF & Takahashi T (1998). Inactivation of presynaptic calcium current contributes to synaptic depression at a fast central synapse. Neuron 20, 797–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger JR & Jonas P (2000). Dynamic control of presynaptic Ca2+ inflow by fast‐inactivating K(+) channels in hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. Neuron 28, 927–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppa MB, Gouzer G, Armbruster M & Ryan TA (2014). Control and plasticity of the presynaptic action potential waveform at small CNS nerve terminals. Neuron 84, 778–789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori T & Takahashi T (2009). Mechanisms underlying short‐term modulation of transmitter release by presynaptic depolarization. J Physiol 587, 2987–3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inchauspe CG, Martini FJ, Forsythe ID & Uchitel OD (2004). Functional compensation of P/Q by N‐type channels blocks short‐term plasticity at the calyx of held presynaptic terminal. J Neurosci 24, 10379–10383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki S, Momiyama A, Uchitel OD & Takahashi T (2000). Developmental changes in calcium channel types mediating central synaptic transmission. J Neurosci 20, 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MB, Konnerth A & Augustine GJ (1991). Action potential broadening and frequency‐dependent facilitation of calcium signals in pituitary nerve terminals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 88, 380–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun K, Piedras‐Rentería ES, Smith SM, Wheeler DB, Lee SB, Lee TG, Chin H, Adams ME, Scheller RH, Tsien RW & Shin HS (1999). Ablation of P/Q‐type Ca(2+) channel currents, altered synaptic transmission, and progressive ataxia in mice lacking the alpha(1A)‐subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96, 15245–15250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya H & Zucker RS (1994). Residual Ca2+ and short‐term synaptic plasticity. Nature 371, 603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M, Yamaguchi K, Eiraku M, Sato M, Takata N, Kiyohara Y, Mishina M, Hirase H, Hashikawa T & Kengaku M (2011). Remodelling of monoplaner Purkinje cell dendrites during cerebellar circuit formation. Plos ONE e20108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S & Hirano T (2007). Sustained structural change of GABAA receptor‐associated protein underlies long‐term potentiation at inhibitory synapses on a cerebellar Purkinje neuron. J Neurosci 27, 6788–6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S & Sakaba T (2015). Control of inhibitory synaptic outputs by low excitability of axon terminals revealed by direct recording. Neuron 85,1273‐1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B & Miledi R (1968). The role of calcium in neuromuscular facilitation. J Physiol 195, 481–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaliq ZM6 Raman IM (2005). Axonal propagation of simple and complex spikes in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci 25, 454–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koester HJ & Johnston D (2005). Target cell‐dependent normalization of transmitter release at neocortical synapses. Science 308, 863–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Zhou H, Scheuer T & Catterall WA (2003). Molecular determinants of Ca(2+)/calmodulin‐dependent regulation of Ca(v)2.1 channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 16059–16064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Wang Y & Tsodyks M. (1998). Differential signaling via the same axon of neocortical pyramidal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95, 5323–5328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveev V, Zucker RS & Sherman A (2004). Facilitation through buffer saturation: constraints on endogenous buffering properties. Biophys J 86, 2691–2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Hirai H & Takahashi T (2013). Activity‐dependent neurotrophin signaling underlies developmental switch of Ca2+ channel subtypes mediating neurotransmitter release. J Neurosci 33, 18755–18763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida S, Few AP, Scheuer T & Catterall WA (2008). Regulation of presynaptic Ca(V)2.1 channels by Ca2+ sensor proteins mediates short‐term synaptic plasticity. Neuron 57, 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsivais P, Clark BA, Roth A & Häusser M (2005). Determinants of action potential propagation in cerebellar Purkinje cell axons. J Neurosci 25, 464–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Felmy F & Schneggenburger R (2008). A limited contribution of Ca2+ current facilitation to paired‐pulse facilitation of transmitter release at the rat calyx of Held. J Physiol 586, 5503–5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E (1998). Vesicle pools and Ca2+ microdomains: new tools for understanding their roles in neurotransmitter release. Neuron 20, 389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neher E & Marty A (1982). Discrete changes of cell membrane capacitance observed under conditions of enhanced secretion in bovine adrenal chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 79, 6712–6716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orduz D & Llano I (2007). Recurrent axon collaterals underlie facilitating synapses between cerebellar Purkinje cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, 17831–17876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedroarena CM & Schwarz C (2003). Efficacy and short‐term plasticity at GABAergic synapses between Purkinje and deep cerebellar nuclei neurons. J Neurophys 89, 704–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, Topolnik L, Lacaille JC & McBain CJ (2006). Compartmentalized Ca2+ channel regulation at divergent mossy‐fiber release sites underlies target cell‐dependent plasticity. Neuron 52, 497–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkel DJ, Hestrin S, Sah P & Nicoll RA (1990). Excitatory synaptic currents in Purkinje cells. Proc Biol Sci. 241, 116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regehr WG (2012). Short‐term synaptic plasticity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4, a005702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozov A, Burnashev N, Sakmann B & Neher E (2001). Transmitter release modulation by intracellular Ca2+ buffers in facilitating and depressing nerve terminals of pyramidal cells in layer 2/3 of the rat neocortex indicates a target cell‐specific difference in presynaptic calcium dynamics. J Physiol 531, 807–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H, Stiefel KM, Racay P, Schwaller B & Eilers J (2003). Mutational analysis of dendritic Ca2+ kinetics in rodent Purkinje cells: role of parvalbumin and calbindin D28k. J Physiol 551, 13–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R & Neher E (2000). Intracellular calcium dependence of transmitter release rates at a fast central synapse. Nature 406, 889–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telgkamp P & Raman IM (2002). Depression of inhibitory synaptic transmission between Purkinje cells and neurons of the cerebellar nuclei. J Neurosci 22, 8447–8457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto T, Jeromin A, Saitoh N, Roder JC & Takahashi T (2002). Neuronal calcium sensor 1 and activity‐dependent facilitation of P/Q‐type calcium currents at presynaptic nerve terminals. Science 295, 2276–2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valera AM, Doussau F, Poulain B, Barbour B & Isope P (2012). Adaptation of granule cell to Purkinje cell synapses to high‐frequency transmission. J Neurosci 32, 3267–3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyleta NP & Jonas P (2014). Loose coupling between Ca2+ channels and release sensors at a plastic hippocampal synapse. Science 343, 665–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt AJ, Cuntz H, Mori M, Nusser Z, Sjöström PJ & Häusser M (2009). Traveling waves in developing cerebellar cortex mediated by asymmetrical Purkinje cell connectivity. Nat Neurosci 12, 463–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RS & Regehr WG (2002). Short‐term synaptic plasticity. Ann Rev Physiol 64, 355–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]