Abstract

Testosterone supplementation therapy (TST) use has dramatically increased over the past decade, due to the availability of newer agents, aggressive marketing, and an increasing incidence of testosterone deficiency (TD). Despite the increase in TST, a degree of ambiguity remains as to the exact diagnostic criteria of TD, and administration and monitoring of TST. One explanation for this phenomenon is the complex role testosterone plays in multiple physiologic pathways. Numerous medical co-morbidities and medications can alter testosterone levels resulting in a wide range of nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms of TD. The diagnosis is also challenging due to the lack of a definitive serum total testosterone level that reliably correlates with symptoms. This observation is particularly true in the aging male and is exacerbated by inconsistencies between different laboratory assays. Several prominent medical societies have developed guideline statements to clarify the diagnosis, but they differ from each other and with expert opinion in several ways. Aside from diagnostic dilemmas, there are numerous subtle advantages and disadvantages of the various testosterone agents to appreciate. The available TST agents have changed significantly over the past decade similar to the trends in the diagnosis of TD. Therefore, as the usage of TST increases, clinicians will be challenged to maintain an up-to-date understanding of TD and TST. The purpose of this review is to provide a clear description of the current strategies for diagnosis and management of TD.

Keywords: androgens, erectile dysfunction, hormones, hypogonadism, testosterone

INTRODUCTION

Testosterone has now become one of the most widely used medications in the United States. This is partly due to an increasing proportion of the population > 65 years of age and the increasing incidence of medical co-morbidities associated with low testosterone, such as diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease.1,2 It is well documented that the incidence of testosterone deficiency (TD) increases with age, partly due to a 0.4%–2.0% per year decline in testosterone production after age 30.3,4 The incidence of TD in healthy, middle-aged men has been reported as high as 6%, with greater increases associated with age beyond 60, medical co-morbidities, and poor health status.5,6,7 In fact, males in the seventh decade have mean plasma testosterone levels 35% lower than young men.8 Given the nonspecific symptoms and variation in testosterone levels associated with the presentation of this disease, diagnosis and treatment still remain a challenge despite an increasing incidence.9 This is evidenced by the fact that only 12% of clinically symptomatic, hypogonadal males are successfully treated despite access to care.10 Therefore, as the usage of testosterone supplementation therapy (TST) continues to increase, clinicians will be challenged to maintain an up-to-date understanding of the diagnosis and management of TD.

PHYSIOLOGY

Testosterone plays a critical role in modulating male sexual development, adult male reproductive health, and sexual function. In addition, it is critical in maintaining lean muscle mass, bone mineral density, and fat metabolism.11 Testosterone production is regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Testosterone production through the HPG axis is a tightly controlled, multi-phased biochemical process. Initially, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GNRH) is secreted from the hypothalamus in a circadian, pulsatile fashion into the portal vascular system. This system provides connection to the anterior pituitary, where GNRH is rapidly internalized, triggering systemic release of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH targets sertoli cells and spermatogonial membranes that regulate the process of spermatogenesis, whereas LH targets Leydig cells whose role is to produce testosterone.11

Once produced, testosterone is released into the systemic circulation where it is either protein bound or unbound. Approximately 30% is tightly protein bound by sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and physiologically inactive.12,13 SHBG is produced in the liver and circulating levels can be influenced by disease states such as hyperthyroidism, cirrhosis, and HIV, which increase SHBG, whereas hypothyroidism, obesity, and nephrotic syndrome decrease SHBG.14,15 Approximately, 68% of serum testosterone is loosely protein bound by albumin and can be coupled with unbound, free testosterone to deter mine bioavailable testosterone.14 Physiologically active, unbound testosterone that is free to exert cytologic effects comprises approximately 2% of circulating testosterone.12,14,15 Within non-testicular tissue, testosterone can be converted to the more potent dihydrotestosterone via the 5α-reductase enzyme or to other androgens such as estrogen via the aromatase enzyme. Intratesticular testosterone levels (200–1000 ng ml−1) are 80–100 fold higher than serum levels and are critical for spermatogenesis and maintained by androgen binding protein produced by sertoli cells.16 In addition to testosterone, estrogen aromatized from testosterone, other androgens, and inhibin all provide negative feedback inhibition at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary glands modulating production.17

Serum testosterone levels can vary over time due to a variety of factors. Diurnal variation, based upon circadian rhythm-driven, pulsatile hypothalamic release of GNRH, results in peak serum testosterone levels during the morning hours. Blunting of the diurnal peak has been shown to occur with aging,18 however a significant proportion of older men aged 65–80 with low afternoon serum testosterone levels will have normal levels in the morning.19,20 Furthermore, 15% of young, healthy men can demonstrate abnormally low levels within a 24 h period.19 Some of this variation can be explained by assay variation, but a certain amount is due to biologic variation from glucose ingestion, triglyceride levels, diurnal, seasonal variation, and activities performed prior to lab draw.21,22

ETIOLOGY

Classification

TD can be caused by a failure of the testes to produce testosterone, interruption of one or several layers of the HPG axis, androgen target tissue dysfunction, or environmental factors such as medications or chronic medical illness. TD can be classified as secondary (or hypogonadotropic) hypogonadism when disruption of the HPG axis leads to inadequate FSH and LH production.15,17,23,24 One important cause of secondary hypogonadism is pituitary dysfunction from hypopituitarism related to radiation, infection, trauma, hyperprolactinemia from hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas, dopaminergic medications, or medical conditions such as chronic renal failure and hypothyroidism.25 Other causes of secondary hypogonadism are primary GNRH deficiency from Kallmann syndrome, Prader–Willi syndrome, and idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Secondary hypogonadism may also result from GNRH deficiency from medications, radiation, chronic illness or conditions resulting in elevated serum levels of inhibin.25,26

Primary (or hypergonadotropic) hypogonadism refers to testicular failure in production of testosterone and spermatogenesis in presence of elevated gonadotropins.15,17,23,24 Common intratesticular causes include a history of treatment for testicular tumor, prior infection such as orchitis, chemotherapy, medications with gonadotoxic effects, environmental toxins, idiopathic testicular atrophy, or iatrogenic removal for trauma or malignancy.17,23,24 One of the more common intratesticular genetic causes of primary hypogonadism includes Klinefelter's syndrome, affecting 0.2% of the male population and representing the most common numerical chromosomal aberration.27 Klinefelter's is often diagnosed during a male factor infertility evaluation for severe oligospermia or azoospermia, which can reveal other causes of male factor infertility associated with primary hypogonadism. Some such causes are genetic, including Y-chromosome microdeletions, chromosomal aberration, 47 XYY syndrome, gonadal dysgenesis, or 46 XY disorders of sexual development.25 Other such causes are anatomic as with varicoceles.28 Varicoceles cause intratesticular dysfunction secondary to testicular hyperthermia, reflux of venous toxins, and increased reactive oxygen species due to relative hypoxia. Finally, hypogonadism related to defects in androgen target tissue utilization of testosterone such as androgen insensitivity syndrome, which may be partial or complete, and 5α-reductase deficiency are rare.24,29

Mixed gonadal dysfunction, often referred to as late onset hypogonadism (LOH), but also known as androgen deficiency in the aging male, partial androgen deficiency of the aging male, age-associated TD syndrome, male menopause and andropause; has become an increasingly important entity.3,17,24,30 The age-related symptomatic decrease in serum testosterone has been shown to occur in approximately 3% and 5% of men in the sixth and seventh decades, respectively.7 Several physiologic changes can account for this phenomenon. SHBG levels have been shown to increase with age, reducing bioavailable and free serum testosterone levels.14,15 LH may be variably elevated in response to a decrease in the number and function of the Leydig cell population, which also correlates with the age-related decline in spermatogenesis and fertility.8 Some have proposed using LH levels in aging men to distinguish compensated hypogonadism from pure primary hypogonadism to understand disease severity and guide treatment decisions.32 Age-related impairments in the HPG axis are also partly responsible, including reduced LH pulse amplitude, LH pulse frequency and GNRH production.8 Additionally, the gradual increase in co-morbid medical conditions with age can effect the HPG axis centrally resulting in HPG axis feedback impairment.

Medications

Several medications have been associated with TD due to induction of primary hypogonadism, secondary hypogonadism, or both.17 Glucocorticoids are well-known for their multi-system side-effects such as osteoporosis, but they can also induce mixed primary and secondary hypogonadism and decrease SHBG levels.23,33 This process has been found to affect up to 80% of men on long-term glucocorticoid therapy on cross-sectional analysis.34 Such an effect has been shown to occur regardless of dose and can persist for up to 12 months.35,36 Previous exposure to exogenous testosterone or anabolic steroids, at any point in life, has been shown to negatively impact the HPG axis and may cause secondary hypogonadism and infertility, an effect which can endure for up to 2 years and in some cases may be permanent.17,37,38,39 This effect is more common in younger men as evidenced by the recent observation that hypogonadal men < 50 years of age have a 10-fold higher risk of previous anabolic steroid exposure than men older than 50 years of age.40

In addition, GNRH analogs, such as those used for prostate cancer treatment, are potent inhibitors of the HPG axis with effects lasting up to 3–4 months after cessation of therapy.41 Similarly, isolated reports have shown androgen analogs such as megastrol acetate used for appetite stimulation in cachectic cancer patients can also induce symptomatic male hypogonadism.42 Commonly used opioid analgesics have been shown to have suppressive effects on the release of gonadotropins centrally and on production of testosterone peripherally by Leydig cells.43,44,45 The onset of action is quick,46 with duration and severity of opioid effect on the HPG axis appearing to be related to half-life and dose of a particular agent used.47,48 The duration of effect, however, appears to be short regardless of duration of therapy.49 Some studies with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have only shown a statistically significant decrease in serum testosterone levels using paroxetine,50 whereas other studies using fluoxetine have not.51 Finally, statins have also shown a modest but statistically significant decrease in serum testosterone levels.52

Medical Conditions

A number of medical conditions have been associated with low serum testosterone levels.44 Obesity is strongly associated with hypogonadism, with a reported 52% prevalence on large population cross-sectional analysis when controlling for obesity-related declines in SHBG.53 Proposed mechanisms include decreased amplitude of LH pulsatility,54 increased plasma leptin levels having central and peripheral inhibitory effects,55 and peripheral conversion of testosterone to estrogen via adipose tissue-dense aromatase enzyme.56 Often co-morbid with obesity, obstructive sleep apnea has been shown to produce a reversible dysfunction of the HPG axis independent of the effects of obesity.57,58 Type 2 diabetes mellitus has also been shown to be highly prevalent in hypogonadal males independent of obesity, with rates nearing 50%.53 Proposed mechanisms include aforementioned obesity-mediated pathways with addition of increased insulin resistance at the hypothalamic level.59 In sum, the exact relationship between obesity, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and TD has yet to be fully elucidated.57 Available data promote a spectrum of possibilities ranging from low testosterone and SHBG levels being predictive of development of metabolic syndrome60 to metabolic syndrome being a risk factor for development of TD.61

Other chronic medical conditions such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic kidney disease and erectile dysfunction (ED) have all been linked to TD with high prevalence rates.44,53,62 In most cases, the underlying pathways are multifactorial.17 Alcohol abuse has been shown to effect the HPG axis at all levels resulting in TD.63 Acute critical illness has long been known to cause decreases in bioavailable testosterone levels.64 HIV is associated with TD in up to 50% during the preantiretroviral era compared with 20%–25% in the postantiretroviral era.44,65,66 The exact mechanism is unknown, but early recognition is important, as hypogonadism is strongly associated with AIDS wasting syndrome.67,68 Adequate treatment with TST demonstrates mitigation of this risk with improvement in several quality of life parameters.69 Although rare, hemochromatosis can result in TD by causing primary or secondary hypogonadism or both, which is potentially reversible with treatment of the underlying etiology.70 Finally, men with low testosterone have been found to suffer from some form of depression in up to 90% of cases with 17% having severe depression.71

Still somewhat controversial, there is recent evidence that TD may be associated with Peyronie's disease (PD), and TST may improve its symptoms. A causative role is unclear, although a complex relationship likely exists. TD does lead to the down-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor and up-regulation of transforming growth factor beta, resulting in corporal fibrosis.72 Reversal of these findings has been shown with TST in animal models.73 While two studies have shown a significant association between TD and PD,74,75 a large, recent retrospective study found that men presenting with either PD or ED have a similar incidence of TD, suggesting TD has a closer relationship with the ED component of PD.76

DIAGNOSIS

Introduction

Despite the recent surge in usage, the diagnosis of TD remains a challenge. This is partly due to the diagnosis being dependent upon establishing presence of clinical symptoms and low serum testosterone levels.23,24,30 However, achieving these two criteria remains difficult due to a lack of standardization regarding the overall evaluation and management of TD.77 This lack of standardization is due to several factors including wide variation in presenting symptoms, limited clinical correlation between serum androgen levels and symptoms, and various issues with laboratory processing and quantification of serum testosterone levels.77

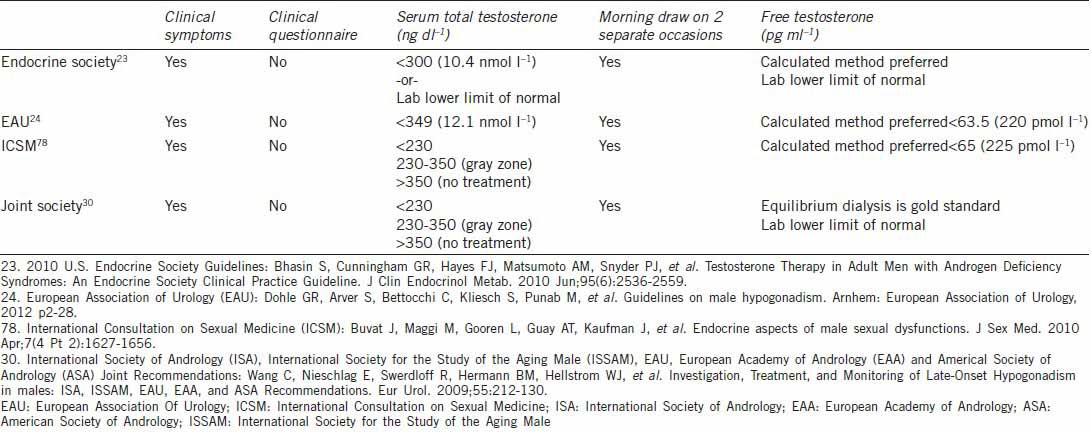

Several specialty societies and expert groups have attempted to standardize the diagnostic process, including the United States Endocrine Society, European Association of Urology, International Consultation on Sexual Medicine (ICSM), and joint guidelines representing numerous international andrology societies (Table 1).23,24,30,77,78 Broadly speaking, these guidelines emphasize the importance of diagnosis in men who first demonstrate clinical signs or symptoms of TD, followed by documentation of a low serum testosterone level only in individuals who do not exhibit easily reversible causes of TD such as medications or acute illness as previously discussed. These guidelines provide a good framework within which clinicians can practice. However, they are partly based upon generally low quality data, especially when defining a low serum testosterone level, and there is some individual expert deviation from these in actual clinical practice.77

Table 1.

Comparison of different society guideline statements on testosterone diagnosis

Clinical Diagnosis

The clinical presentation of TD in adult males can be variable, insidious, and often confused with other clinical conditions.78 Because testosterone is a key regulator in male sexual function pathways, common symptoms of TD include decreased libido, reduced nocturnal erections, ED, and male factor infertility.79,80,81,82 Additional signs and symptoms less specific to TD are reflective of testosterone's broad systemic effects and include decreased energy, decreased cognition, reduced muscle mass, reduced strength, increased adiposity, decreased bone mineral density, hot flashes, sleep disturbance, and depressed mood.23,24,30,78 Hypogonadal symptom screening questionnaires can be sensitive, but are poorly specific for diagnosing TD; accordingly, their use is not strongly recommended. Similarly, general population screening for TD is also discouraged.23,24,30,78

Physical exam is a helpful adjunct to symptom elucidation. Testicular volume < 10 ml is considered a strong predictor of TD, especially with increasing age. However, testicular volume must be interpreted in the context of existing co-morbidities and should prompt questioning as to historical risk factors for primary hypogonadism such as testicular trauma, chemotherapy, or prior surgery.77,82 Testes volumes < 5 ml in setting of elevated gonadotropins are highly suggestive of Klinefelter's syndrome and warrant karyotype testing.77 Other helpful findings during the genital exam include assessment for a testicular asymmetry, varicoceles, or testicular masses. Additional general exam findings of gynecomastia, decreased body hair, visceral obesity, and diminished muscle mass are also helpful findings in the diagnosis of TD. Small, age-adjusted prostate volume has also been implicated as a diagnostic finding but is only corroborated by a few expert clinicians.77,78,82

Laboratory Diagnosis

Once patients are suspected of TD based upon clinical signs and symptoms, the diagnosis should be confirmed with laboratory testing to determine serum testosterone levels. Most agree this should be done initially by drawing a total serum testosterone level on two separate occasions during morning hours. As previously discussed, there is a diurnal variation in serum testosterone levels, and up to 30% of patients with initially abnormal values have normal levels on repeat testing.19,20,83 Joint international society guidelines propose an upper limit of normal as 350 ng dl−1, above which treatment is usually not beneficial.30,78 However, the lower limit of normal, below which all appropriate individuals should undergo treatment, has not clearly been established. These same international society guidelines highlight population-based data from young men with TD undergoing TST that show the greatest benefit from treatment occurs in those with sexual symptoms and total serum testosterone levels < 230 ng dl−1.30,78 Other population-based data demonstrate variable threshold levels of total serum testosterone at presentation among different TD symptoms and individuals. Most symptoms correlate to a testosterone threshold level of 300 ng dl−1 at presentation, which corresponds to most laboratories’ lower limit of normal for young men.5,80,84 Based on this data, the 2006 U.S. Endocrine Society guidelines recommended a total serum testosterone level of 300 ng dl−1 as the diagnostic threshold for treatment. This is also the same value used by the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) to define hypogonadism for clinical trial purposes.22 However, in the 2010 Endocrine Society update, clinicians were instead referred to their individual laboratories reference ranges to guide treatment decisions due to several laboratory issues further adding to the difficulty in determining normal levels of serum testosterone.23,85

One laboratory issue is the preponderance of assays available including radioimmunoassay (RIA), immunoassay (IAs) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). RIA and IA are highly specific but can vary significantly between laboratories based upon antibody type used.22 LC-MS is accurate and precise but requires strict quality control and calibration. All three are plagued by decreased accuracy at testosterone levels below 300 ng dl−1. In addition, standardized laboratory specimen processing and equipment calibration standards do not yet exist.22

Regardless of which assay used, most authors agree that those patients who are clinically symptomatic with confirmed total serum testosterone levels < 230 ng dl−1 will benefit the most from treatment. In symptomatic men with confirmed levels > 350 ng dl−1, several guidelines suggest that these patients may not experience benefit from treatment. However, some experts advocate for treatment in clearly symptomatic men regardless of serum testosterone levels, including those with levels > 350 ng dl−1.77 Within this group, experts attribute benefit of treatment to modulation of the androgen receptor, mediated by genetic polymorphisms in exon one of the androgen receptor gene in the form of increased cysteine adenosine guanine (CAG) repeats. Certain data have shown increased CAG repeats are associated with decreased sensitivity in the receptor to testosterone and manifestation of TD symptoms despite “normal” serum testosterone levels.86,87

Unfortunately, many patients who experience signs and symptoms of TD fall into the “gray area” of 230–350 ng dl−1. This may be due to altered serum SHBG levels as seen in older or obese patients, and SHBG levels should be checked and serum testosterone levels repeated. For these patients, total testosterone levels may not reflect bioavailable levels. In “gray area” patients, expert and guideline statements support the determination of biologically active testosterone by measuring free testosterone.23,30,77 Equilibrium dialysis is the gold standard for free testosterone measurement, but it is complex and not available at many laboratories.78 More commonly available analog assays are not recommended due to lack of sensitivity.13,88 Therefore, most laboratories utilize calculated free testosterone according to Vermeulen method, which is based upon serum total testosterone, SHBG and albumin levels. This has been shown to correlate well with equilibrium dialysis methods.13,89 Some experts, including these authors, advocate for use of calculated free testosterone levels in the diagnosis of all patients to avoid the ambiguity of total serum testosterone levels.77 If clinicians do not have free or bioavailable testosterone levels available at their local laboratory, they can check SHBG and albumin levels and then use an app such as “BioT” or online calculator (www.issam.ch/freetesto.htm) to calculate the levels of free and bioavailable testosterone.

Additional endocrine testing is warranted in those with suspected or confirmed TD. Serum LH levels should be measured to establish primary versus secondary hypogonadism. If LH levels are low and secondary hypogonadotropic hypogonadism is suspected, further testing is important to elucidate the underlying cause. These tests may include serum prolactin levels to rule out hyperprolactinemia, iron saturation studies to rule out the hemochromatosis, and estrogen levels to determine the testosterone to estrogen ratio.7,23,30,90 Some authors advocate for pituitary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if total serum testosterone levels are < 150 ng dl−1 coupled with either severely depressed gonadotropin levels or elevated prolactin levels are present.91 However, despite the dogma of pituitary MRI and the concern for a prolactinoma, the most common cause of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with levels < 100 ng dl−1 is prior exposure to exogenous androgens.40 If primary hypegonadotropic hypogonadism is suspected, consideration should be made to perform karyotype testing for Klinefelter's syndrome.23,92 TD also increases the risk for decreased bone mineral density and osteoporotic fracture.93 This effect is reversible in men of all ages on TST, with some experts recommending all osteoporotic men undergo TD evaluation.94,95,96 Therefore, baseline dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning should be considered in those with severe TD.23,30

TREATMENT

Treatment Goal

The goal of TST is to alleviate hypogonadal symptoms by restoring physiologic levels of serum testosterone. The exact serum testosterone level required to achieve maximal efficacy and safety is currently unknown.30 Many authors often cite low-to-mid level range of serum testosterone levels as a reasonable target in otherwise young, asymptomatic men.86 These authors target a mid-to-high range, due to the lower risk of necessary dosing adjustments and a better chance for immediate symptom improvement resulting in improved compliance. However, there can be variation in what these ranges actually mean due to laboratory variation in assay type and processing, as well as individual variation due to CAG repeats mediating changes in androgen receptor sensitivity as previously discussed.78 Periodic observation of serum hormone concentration and its metabolites should be performed to minimize treatment-associated side-effects.97 Sustained supraphysiologic levels should be avoided.98 Improvement in symptoms should become apparent after 3 months of treatment. However, the results vary with the symptom. Energy and libido improve early, while osteoporosis may require as long as 1 year to improve.

Contraindications

There are certain clinical scenarios in which several specialty society and expert group guideline statements indicate caution or contraindication to TST.23,24,30,78 Breast cancer in men is rare and universally accepted as a clear contraindication.99,100 Presence of prostate cancer, particularly metastatic prostate cancer,101 has historically been considered a contraindication to TST. Several guideline statements still consider this to be a contraindication,20,24,30 including men at increased risk for developing prostate cancer-based upon the presence of a palpable nodule or elevated prostate specific antigen (PSA).102,103 Emergence of the saturation model104 has initiated a paradigm shift away from withholding TST in men with TD over concern for exogenous testosterone promoting development of prostate cancer.105 The 2010 Endocrine Society guidelines acknowledge that men at risk for prostate cancer may be treated with TST if cleared by a urologist after appropriate referral. A robust body of evidence supports this statement, but such men should still be closely monitored for development of prostate cancer while on TST.106,107,108 Furthermore, emerging data suggest TST in patients with a history of successfully treated, organ-confined prostate cancer is most likely safe.109,110,111,112,113,114,115 The most recent ICSM guidelines emphasize this point, stating that men with TD after successfully treated localized prostate cancer, without evidence of disease after a period of observation, are candidates for TST provided they have a thorough discussion of the potential risks and limited safety data.78

A similar paradigm shift has occurred for TST in men with benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH). The Endocrine Society guidelines recommend urology referral for TST in men with TD and significant lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) based upon International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) >19. ICSM guidelines acknowledge demonstrated safety of TST in men with IPSS > 21 based upon numerous studies, particularly after successful treatment of lower urinary tract obstruction.78,116 In addition, baseline hematocrit > 50%, uncontrolled or poorly controlled congestive heart failure, and obstructive sleep apnea are also contraindications.116 Finally, TST is clearly contraindicated in men with TD who still desire fertility and alternate therapies should be pursued.78

Preparations

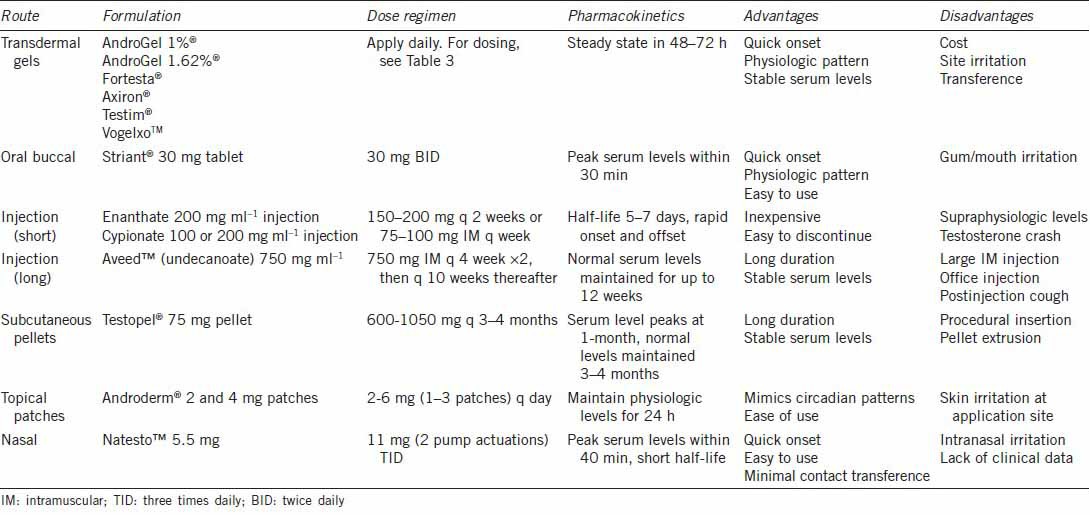

Testosterone supplementation therapy exists as several different preparations administered by various routes, thereby requiring the treating physician to have an adequate understanding of the advantages and drawbacks of each preparation (Table 2). This is also important to facilitate the choice of agent by a shared physician-patient decision-making process.116 Due to the possibility of developing an adverse event during treatment requiring discontinuation, an initial trial of a short-acting agent that can be quickly withdrawn may be warranted, particularly in older patients.24,30

Table 2.

Overview of available testosterone preparations

Although not available in the United States, oral agents are available internationally and provide TST in the convenience of a pill. Oral testosterone undecanoate is esterified to allow lymphatic absorption and partial avoidance of hepatic first-pass metabolism, but systemic absorption is still variable and at best serum levels reach mid-range.117,118 It is usually prescribed as a 2 or 3-dose regimen (40–80 mg) when using capsules or tablets, respectively.97 Oral 17-alpha-alkylated derivatives of testosterone can be more effective, but have been associated with hepatotoxicity and are no longer used clinically.97,118 Buccal and sublingual formulations represent well-tolerated delivery systems with good efficacy due to avoidance of hepatic first-pass metabolism.24 Striant®, available as a 30 mg tablet, is the only buccal formulation available in the United States. The tablet should be applied every 12 h to the gum above the incisor tooth.117 Absorption is rapid, reaching peak serum levels in 30 min, which is comparable to topical gel solutions.117,119 Commonly reported side effects generally occur in < 10% of patients and include a gum edema, gingivitis, gum blistering and bitter taste. Oral and buccal formulations are rarely used in the current management of TD due to better efficacy and lower side effects of newer formulations.

Intramuscular injections via an oil depot first became available in the 1950's and are considered the most cost-effective form of TST. They are available in short and long-acting preparations. The shortest acting agent is testosterone propionate, which requires frequent doses and has led to infrequent usage due to the inconvenience.120 Slightly longer but still relatively short-acting agents testosterone enanthate and testosterone cypionate require injections every 1–2 weeks due to half-lives of 5–7 days, respectively. All of the short-acting agents are plagued by a “roller coaster” effect by achieving supraphysiologic levels within 2–4 days after injection followed by sub-therapeutic levels by 10–14 days.31,78,97,120 A rapid decline in serum levels around 10–14 days has been called “testosterone crash” and is associated with sudden recurrence of TD symptoms.121 To minimize these effects, more frequent dosing from once to twice weekly has been suggested as is preferred by these authors. An additional drawback of injectable testosterone is an increased susceptibility of patients to develop erythrocytosis.122 Longer-acting injectable testosterone undecanoate (Aveed™) recently became USFDA-approved in 2014, with serum levels remaining in mid-normal range for up to 12 weeks after a single injection.

Subcutaneous testosterone pellets represent the longest-acting testosterone preparation, which have been available for decades but were approved as Testopel® by USFDA in 2008.123 The pellets are comprised of testosterone crystals and are inserted in a lateral hip or abdominal location, over time resulting in systemic absorption.124 Eight to fourteen, 75 mg pellets are implanted into adipose tissue (600–1050 mg dose), dissolving in 3–4 months, with demonstrated physiologic levels for up to 4 months.123,125,126 Traditionally, 5% of patients experience local side-effects including bleeding, infection, bruising, pain and pellet expulsion. More recent reports have described pellet extrusion rate to be < 1%.123

Transdermal testosterone preparations are currently the most commonly utilized forms of TST. Transdermal options include adhesive skin patches, topical gels, or topical solutions, all requiring daily or every other daily use to maintain serum levels within normal range.97 Transdermal preparations have a quick onset and a duration < 24–48 h allowing quick discontinuation should an adverse effect be experienced.127

Adhesive patches were initially developed for transcrotal application in the 1990's (Testoderm) but were later discontinued due to significant skin irritation. More recently, nonscrotal patches (Androderm®) have been developed in 2 or 4 mg formulations, providing consistent testosterone delivery with kinetics mimicking normal circadian rhythms when applied nightly. Some earlier data have suggested better efficacy compared to intramuscular preparations, but patches are still plagued by local skin reactions including induration, vesicle formation, and contact dermatitis occurring in up to 37% of patients, leading to poor compliance.127,128 Use of a 0.1% triamcinolone corticosteroid cream at the patch site before patch application has been shown to diminish local skin reactions with minimal impact on testosterone delivery.129 Among transdermal preparations, patches have fallen out of favor due to the high rate of dermatitis.

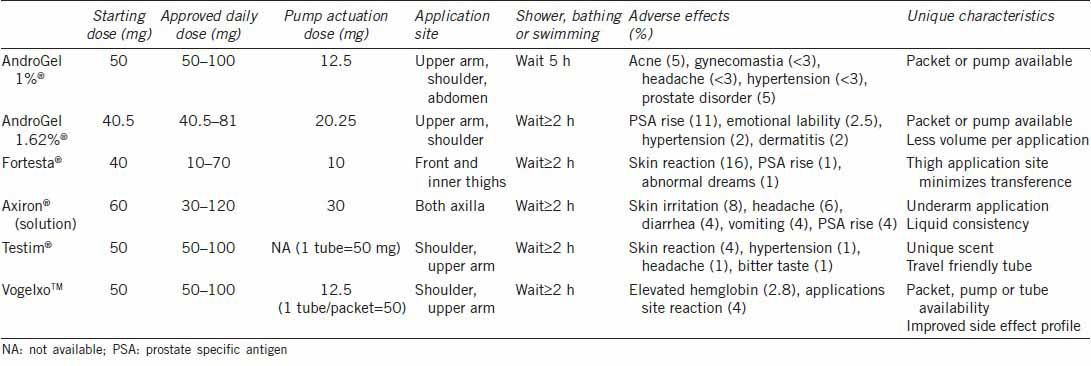

Transdermal gels (AndroGel 1%®, AndroGel 1.62%®, Testim®, Fortesta®, and Vogelxo™) and solutions (Axiron®) were first introduced in the United States in 2000 as an improvement over transdermal patches (Table 3). Dosing can be titrated individually based upon skin absorption rates related to metabolism across the stratum corneum.120 The gels contain ethanol and are mixed with a skin permeation enhancer for application at same skin site daily on the shoulders, upper arms, abdomen or inner thigh during morning hours, with serum steady state levels achieved in 48–72 h.130 Application to multiple sites does not appear to effect overall systemic pharmacokinetics of transdermal gels.131 Axiron® is a topical alcohol-based testosterone (2%) solution applied in a similar way to axillary skin. In all cases, drying usually occurs within 10–15 min and hand washing is necessary to minimize contact spread to other individuals. This has led to recommendations for mandatory residence time at applications site of up to 2 h to minimize the transference.132 The risk of skin-to-skin contact has led to a USFDA black box warning on transdermal gel transference. Similar to patches, gels and solutions provide normal to elevated serum DHT levels due to dermal concentrations of 5-alpha reductase enzyme, which have been associated with hair loss. In general, transdermal gels are very well tolerated by patients with the most commonly reported adverse reactions including acne, headache, emotional lability, nervousness, abnormal dreams, gynecomastia, and mastodynia, all occurring in < 8% of patients. Patients in whom the initial clinical response is unsatisfactory may try switching to an alternate gel or solution to improve serum testosterone levels.133

Table 3.

Topical testosterone gels and solutions

Recently approved by the USFDA on 5/28/2014, intranasal testosterone (Natesto™) represents another alternative route for TST. Recommended dosing is 11 mg 3 times daily, reaching maximum serum levels within 40 min with half-life ranging from 10–100 min.134,135 Phase three clinical trials demonstrated 90% effectiveness within 90 days of use with most commonly reported adverse reactions including PSA increase, headache, and local intranasal symptoms. Intranasal route minimizes close contact transference, but minimal data exist to date regarding overall tolerance and effectiveness outside of a clinical trial context.

The aromatase inhibitor anastrazole has demonstrated benefit in men with TD and infertility, and those with LOH, by improving serum androgen levels and testosterone/estradiol ratio.136,137,138 Due to its similarity to LH, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) has been shown to improve the majority of TD symptoms in men with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.139 In addition, concomitant administration of low dose hCG with TST has been shown to maintain spermatogenesis in hypogonadal men desiring fertility preservation while receiving TST.140 Clomiphene citrate, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, is not USFDA approved for TD but has demonstrated improvement in signs and symptoms, with a favorable safety profile and a protective effect on spermatogenesis, suggesting an important role in younger hypogonadal men wishing to preserve fertility.141,142,143 Both clomiphene citrate and its isomer enclomiphene citrate, which is currently being tested in clinical trials, raise gonadotropins to improve hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Through a positive LH effect endogenous testosterone production is increased, and a positive FSH effect may protect and potentially improve spermatogenesis.144,145 Enclomiphene citrate in is phase 3 trials currently and is poised to be a very impactful treatment alternative to exogenous testosterone.

Monitoring

Several guideline statements agree23,24,30,78 all men diagnosed with TD wishing to undergo TST should be screened for contraindications as described above. All should have a baseline hematocrit, and those at potential risk for prostate cancer development should have a DRE and PSA screening regularly performed according to guideline recommendations.146 Those with LUTS associated with BPH should have symptoms evaluated and addressed at baseline, and those suspected of decreased bone mineral density should have a baseline DEXA scan.

Monitoring after initiation of treatment should occur more frequently initially, every 3–6 months for the first year and every 6–12 months thereafter. At each visit, clinicians should specifically monitor for symptomatic improvement, treatment modality-specific adverse effects, serum total and free testosterone levels, serum hematocrit, and in those men identified at increased risk, DRE, PSA testing, and evaluation of LUTS should be performed. Most TD symptoms should be expected to improve by 3–6 months, but a few may require longer.147 PSA has been shown to have an initial rise after starting TST,148 on average rising 0.3 ng dl−1 in young men and 0.44 ng dl−1 in older men after 6 months of therapy, with a rise > 1.4 ng dl−1 being unusual.149 Subsequent rises in PSA may warrant discontinuation of therapy and prostate biopsy. Elevation in hematocrit is one of the most common adverse effects of TD and tends to occur more commonly in older men and with injectable preparations.116,150 It can take up to 12 months for hematocrit levels to peak, but should they rise to > 54%, treatment should be attenuated and phlebotomy considered.147 Bone mineral density should be monitored every 1–2 years with repeat DEXA scan.

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Traish AM, Saad F, Feeley RJ, Guay A. The dark side of testosterone deficiency: III. Cardiovascular disease. J Androl. 2009;30:477–94. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.007245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Traish AM, Saad F, Guay A. The dark side of testosterone deficiency: II. Type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance. J Androl. 2009;30:23–32. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.108.005751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu FC, Tajar A, Pye SR, Silman AJ, Finn JD, et al. Hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis disruptions in older men are differentially linked to age and modifiable risk factors: the European male aging study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2737–45. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaufman JM, Vermeulen A. The decline of androgen levels in elderly men and its clinical and therapeutic implications. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:833–76. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall SA, Esche GR, Araujo AB, Travison TG, Clark RV, et al. Correlates of low testosterone and symptomatic androgen deficiency in a population-based sample. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3870–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araujo AB, Esche GR, Kupelian V, O’Donnell AB, Travison TG, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic androgen deficiency in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4241–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Araujo AB, O’Donnell AB, Brambilla DJ, Simpson WB, Longcope C, et al. Prevalence and incidence of androgen deficiency in middle-aged and older men: estimates from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5920–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vermeulen A, Kaufman JM. Ageing of the hypothalamo-pituitary-testicular axis in men. Horm Res. 1995;43:25–8. doi: 10.1159/000184233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGill JJ, Shoskes DA, Sabanegh ES. Androgen deficiency in older men: indications, advantages, and pitfalls of testosterone replacement therapy. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:797–806. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.79a.12010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall SA, Araujo AB, Esche GR, Williams RE, Clark RV, et al. Treatment of symptomatic androgen deficiency: results from the Boston Area Community Health Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1070–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.10.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Turek PJ. Male reproductive physiology. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters AP, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier-Saunders; 2012. pp. 591–615. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhasin S, Zhang A, Coviello A, Jasuja R, Ulloor J, et al. The impact of assay quality and reference ranges on clinical decision making in the diagnosis of androgen disorders. Steroids. 2008;73:1311–7. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosner W, Auchus RJ, Azziz R, Sluss PM, Raff H. Position statement: utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: an Endocrine Society position statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:405–13. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braunstein GD. Testes. In: Greenspan FS, Strewler GJ, editors. Basic and Clinical Endocrinology. 5th ed. Stamford Connecticut: Appleton and Lange; 1997. pp. 422–52. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petak SM, Nankin HR, Spark RF, Swerdloff RS, Rodriguez-Rigau JL, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of hypogonadism in adult male patients-2002 update. Endocr Pract. 2002;8:440–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarow JP, Chen H, Rosner TW, Trentacoste S, Zirkin BR. Assessment of the androgen environment within the human testis: minimally invasive method to obtain intratesticular fluid. J Androl. 2001;22:640–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pantalone KM, Faiman C. Male hypogonadism: more than just a low testosterone. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:717–25. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.79a.11174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bremner WJ, Vitiello MV, Prinz PN. Loss of circadian rhythmicity in blood testosterone levels with aging in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;56:1278–81. doi: 10.1210/jcem-56-6-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brambilla DJ, O’Donnell AB, Matsumoto AM, McKinlay JB. Intraindividual variation in levels of serum testosterone and other reproductive and adrenal hormones in men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;67:853–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crawford ED, Barqawi AB, O’Donnell C, Morgentaler A. The association of time of day and serum testosterone concentration in a large screening population. BJU Int. 2007;100:509–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith RP, Coward RM, Kovac JR, Lipshultz LI. The evidence for seasonal variations of testosterone in men. Maturitas. 2013;74:208–12. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paduch DA, Brannigan RE, Fuchs EF, Kim ED, Marmar JL, et al. The laboratory diagnosis of testosterone deficiency. Urology. 2014;83:980–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, Matsumoto AM, Snyder PJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2536–59. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dohle GR, Arver S, Bettocchi C, Kliesch S, Punab M, et al. Arnhem: European Association of Urology; 2012. Guidelines on male hypogonadism; pp. 2–28. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behre HM, Nieschlang E, Meschede D, Partsch CJ. Diseases of the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland. In: Nieschlag E, Behre HM, Nieschlag S, editors. Andrology – Male Reproductive Health and Dysfunction. 3rd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2010. pp. 169–92. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guay A, Seftel AD, Traish A. Hypogonadism in men with erectile dysfunction may be related to a host of chronic illnesses. Int J Impot Res. 2010;22:9–19. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2009.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bojesen A, Juul S, Gravholt CH. Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome: a national registry study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:622–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanrikut C, Goldstein M, Rosoff JS, Lee RK, Nelson CJ, et al. Varicocele as a risk factor for androgen deficiency and effect of repair. BJU Int. 2011;108:1480–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.10030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nieschlag E, Behre HM, Wieacker P. Disorders at the testicular level. In: Nieschlag E, Behre HM, Nieschlag S, editors. Andrology – Male Reproductive Health and Dysfunction. 3rd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2010. pp. 193–238. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang C, Nieschlag E, Swerdloff R, Behre HM, Hellstrom WJ, et al. Investigation, treatment, and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males: ISA, ISSAM, EAU, EAA, and ASA recommendations. Eur Urol. 2009;55:121–30. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morales A, Lunenfeld B. International Society for the Study of the Aging Male. Investigation, treatment and monitoring of late-onset hypogonadism in males. Official recommendations of ISSAM. International Society for the Study of the Aging Male. Aging Male. 2002;5:74–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tajar A, Forti G, O’Neill TW, Lee DM, Silman AJ, et al. Characteristics of secondary, primary, and compensated hypogonadism in aging men: evidence from the European Male Ageing Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1810–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukert BP, Raisz LG. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: pathogenesis and management. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:352–64. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-5-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fraser LA, Morrison D, Morley-Forster P, Paul TL, Tokmakejian S, et al. Oral opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: higher prevalence of hypogonadism in men than in women. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2009;117:38–43. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1076715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrison D, Capewell S, Reynolds SP, Thomas J, Ali NJ, et al. Testosterone levels during systemic and inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Respir Med. 1994;88:659–63. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(05)80062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Axelrod L. Glucocorticoid therapy. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976;55:39–65. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holma PK. Effects of an anabolic steroid (metandienone) on spermatogenesis. Contraception. 1977;15:151–62. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(77)90013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu PY, Swerdloff RS, Christenson PD, Handelsman DJ, Wang C, et al. Rate, extent, and modifiers of spermatogenic recovery after hormonal male contraception: an integrated analysis. Lancet. 2006;367:1412–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68614-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jarow JP, Lipshultz LI. Anabolic steroid-induced hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:429–31. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coward RM, Rajanahally S, Kovac JR, Smith RP, Pastuszak AW, et al. Anabolic steroid induced hypogonadism in young men. J Urol. 2013;190:2200–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tunn UW, Canepa G, Kochanowsky A, Kienle E. Testosterone recovery in the off-treatment time in prostate cancer patients undergoing intermittent androgen deprivation therapy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15:296–302. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2012.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dev R, Del Fabbro E, Bruera E. Association between megestrol acetate treatment and symptomatic adrenal insufficiency with hypogonadism in male patients with cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1173–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daniell HW, Lentz R, Mazer NA. Open-label pilot study of testosterone patch therapy in men with opioid-induced androgen deficiency. J Pain. 2006;7:200–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalyani RR, Gavini S, Dobs AS. Male hypogonadism in systemic disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:333–48. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katz N, Mazer NA. The impact of opioids on the endocrine system. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:170–5. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181850df6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mendelson JH, Inturrisi CE, Renault P, Senay EC. Effects of acetylmethadol on plasma testosterone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1976;19:371–4. doi: 10.1002/cpt1976193371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roberts LJ, Finch PM, Pullan PT, Bhagat CI, Price LM. Sex hormone suppression by intrathecal opioids: a prospective study. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:144–8. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daniell HW. Hypogonadism in men consuming sustained-action oral opioids. J Pain. 2002;3:377–84. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.126790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tanrikut C, Feldman AS, Altemus M, Paduch DA, Schlegel PN. Adverse effect of paroxetine on sperm. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:1021–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bell S, Shipman M, Bystritsky A, Haifley T. Fluoxetine treatment and testosterone levels. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2006;18:19–22. doi: 10.1080/10401230500464612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schooling CM, Au Yeung SL, Freeman G, Cowling BJ. The effect of statins on testosterone in men and women, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med. 2013;11:57. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mulligan T, Frick MF, Zuraw QC, Stemhagen A, McWhirter C. Prevalence of hypogonadism in males aged at least 45 years: the HIM study. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:762–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.00992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vermeulen A, Kaufman JM, Deslypere JP, Thomas G. Attenuated luteinizing hormone (LH) pulse amplitude but normal LH pulse frequency, and its relation to plasma androgens in hypogonadism of obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:1140–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.5.8496304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Isidori AM, Caprio M, Strollo F, Moretti C, Frajese G, et al. Leptin and androgens in male obesity: evidence for leptin contribution to reduced androgen levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3673–80. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roth MY, Amory JK, Page ST. Treatment of male infertility secondary to morbid obesity. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:415–9. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mah PM, Wittert GA. Obesity and testicular function. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:180–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meston N, Davies RJ, Mullins R, Jenkinson C, Wass JA, et al. Endocrine effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure in male patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. J Intern Med. 2003;254:447–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dhindsa S, Miller MG, McWhirter CL, Mager DE, Ghanim H, et al. Testosterone concentrations in diabetic and nondiabetic obese men. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1186–92. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kupelian V, Page ST, Araujo AB, Travison TG, Bremner WJ, et al. Low sex hormone-binding globulin, total testosterone, and symptomatic androgen deficiency are associated with development of the metabolic syndrome in nonobese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:843–50. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goulis DG, Tarlatzis BC. Metabolic syndrome and reproduction: I. testicular function. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2008;24:33–9. doi: 10.1080/09513590701582273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guay AT, Traish A. Testosterone deficiency and risk factors in the metabolic syndrome: implications for erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am. 2011;38:175–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Emanuele MA, Emanuele NV. Alcohol's effects on male reproduction. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22:195–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woolf PD, Hamill RW, McDonald JV, Lee LA, Kelly M. Transient hypogonadotropic hypogonadism caused by critical illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60:444–50. doi: 10.1210/jcem-60-3-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crum NF, Furtek KJ, Olson PE, Amling CL, Wallace MR. A review of hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction among HIV-infected men during the pre- and post-HAART eras: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19:655–71. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rietschel P, Corcoran C, Stanley T, Basgoz N, Klibanski A, et al. Prevalence of hypogonadism among men with weight loss related to human immunodeficiency virus infection who were receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1240–4. doi: 10.1086/317457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grinspoon S, Corcoran C, Lee K, Burrows B, Hubbard J, et al. Loss of lean body and muscle mass correlates with androgen levels in hypogonadal men with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and wasting. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:4051–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.11.8923860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Behler C, Shade S, Gregory K, Abrams D, Volberding P. Anemia and HIV in the antiretroviral era: potential significance of testosterone. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21:200–6. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Grinspoon S, Corcoran C, Askari H, Schoenfeld D, Wolf L, et al. Effects of androgen administration in men with the AIDS wasting syndrome. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:18–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-1-199807010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McDermott JH, Walsh CH. Hypogonadism in hereditary hemochromatosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2451–5. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kelly TM, Edwards CQ, Meikle AW, Kushner JP. Hypogonadism in hemochromatosis: reversal with iron depletion. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:629–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-5-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Khera M, Bhattacharya RK, Blick G, Kushner H, Nguyen D, et al. The effect of testosterone supplementation on depression symptoms in hypogonadal men from the Testim Registry in the US (TRiUS) Aging Male. 2012;15:14–21. doi: 10.3109/13685538.2011.606513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Traish AM, Guay AT. Are androgens critical for penile erections in humans. Examining the clinical and preclinical evidence? J Sex Med. 2006;3:382–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Traish AM, Park K, Dhir V, Kim NN, Moreland RB, et al. Effects of castration and androgen replacement on erectile function in a rabbit model. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1861–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.4.6655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nam HJ, Park HJ, Park NC. Does testosterone deficiency exaggerate the clinical symptoms of Peyronie's disease? Int J Urol. 2011;18:796–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2011.02842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cavallini G, Biagiotti G, Lo Giudice C. Association between Peyronie disease and low serum testosterone levels: detection and therapeutic considerations. J Androl. 2012;33:381–8. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.111.012948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coward RM, Verges D, Smith AB, Carson CC. Testosterone deficiency is similarly prevalent among men presenting with either peyronie's disease or erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2012;9:3–62. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Morgentaler A, Khera M, Maggi M, Zitzmann M. Commentary: who is a candidate for testosterone therapy? A synthesis of international expert opinions. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1636–45. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Buvat J, Maggi M, Gooren L, Guay AT, Kaufman J, et al. Endocrine aspects of male sexual dysfunctions. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1627–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zitzmann M, Faber S, Nieschlag E. Association of specific symptoms and metabolic risks with serum testosterone in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4335–43. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Corona G, Isidori AM, Buvat J, Aversa A, Rastrelli G, et al. Testosterone supplementation and sexual function: a meta-analysis study. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1577–92. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Travison TG, Morley JE, Araujo AB, O’Donnell AB, McKinlay JB. The relationship between libido and testosterone levels in aging men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2509–13. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Corona G, Mannucci E, Ricca V, Lotti F, Boddi V, et al. The age-related decline of testosterone is associated with different specific symptoms and signs in patients with sexual dysfunction. Int J Androl. 2009;32:720–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Diver MJ, Imtiaz KE, Ahmad AM, Vora JP, Fraser WD. Diurnal rhythms of serum total, free and bioavailable testosterone and of SHBG in middle-aged men compared with those in young men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;58:710–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kelleher S, Conway AJ, Handelsman DJ. Blood testosterone threshold for androgen deficiency symptoms. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3813–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bhasin S, Cunningam GR, Hayes FJ, Matsumoto AM, Snyder PJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in adult men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1995–2010. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zitzmann M, Nieschlag E. Androgen receptor gene CAG repeat length and body mass index modulate the safety of long-term intramuscular testosterone undecanoate therapy in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3844–53. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zitzmann M. The role of the CAG repeat androgen receptor polymorphism in andrology. Front Horm Res. 2009;37:52–61. doi: 10.1159/000175843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Swerdloff RS, Wang C. Free testosterone measurement by the analog displacement direct assay: old concerns and new evidence. Clin Chem. 2008;54:458–60. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.101303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3666–72. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Corona G, Mannucci E, Fisher AD, Lotti F, Ricca V, et al. Effect of hyperprolactinemia in male patients consulting for sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1485–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Citron JT, Ettinger B, Rubinoff H, Ettinger VM, Minkoff J, et al. Prevalence of hypothalamic-pituitary imaging abnormalities in impotent men with secondary hypogonadism. J Urol. 1996;155:529–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Handelsman DJ, Liu PY. Klinefelter's syndrome - a microcosm of male reproductive health. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1220–2. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hoppé E, Bouvard B, Royer M, Chappard D, Audran M, et al. Is androgen therapy indicated in men with osteoporosis? Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80:459–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Hannoush P, Berlin JA, Loh L, et al. Effect of testosterone treatment on bone mineral density in men over 65 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1966–72. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.6.5741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kacker R, Conners W, Zade J, Morgentaler A. Bone mineral density and response to treatment in men younger than 50 years with testosterone deficiency and sexual dysfunction or infertility. J Urol. 2014;191:1072–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Spitzer M, Huang G, Basaria S, Travison TG, Bhasin S. Risks and benefits of testosterone therapy in older men. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:414–24. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bassil N, Alkaade S, Morley JE. The benefits and risks of testosterone replacement therapy: a review. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2009;5:427–48. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Buvat J, Shabsigh R, Guay A, Gooren L, Torres LO, et al. Hormones, metabolism, aging and men's health. Standard practice in sexual medicine. In: Porst II, Buvat J, editors. Malden. Massachusetts and Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. pp. 225–86. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Thomas SR, Evans PJ, Holland PA, Biswas M. Invasive breast cancer after initiation of testosterone replacement therapy in a man - a warning to endocrinologists. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:201–3. doi: 10.4158/EP.14.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Medras M, Filus A, Jozkow P, Winowski J, Sicinska-Werner T. Breast cancer and long-term hormonal treatment of male hypogonadism. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;96:263–5. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9074-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Fowler JE, Jr, Whitmore WF., Jr The response of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the prostate to exogenous testosterone. J Urol. 1981;126:372–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)54531-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Thompson IM, Pauler DK, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lucia MS, et al. Prevalence of prostate cancer among men with a prostate-specific antigen level < or=4.0 ng per milliliter. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2239–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:529–34. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Morgentaler A, Traish AM. Shifting the paradigm of testosterone and prostate cancer: the saturation model and the limits of androgen-dependent growth. Eur Urol. 2009;55:310–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Khera M, Crawford D, Morales A, Salonia A, Morgentaler A. A new era of testosterone and prostate cancer: from physiology to clinical implications. Eur Urol. 2014;65:115–23. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Roddam AW, Allen NE, Appleby P, Key TJ Endogenous Hormones and Prostate Cancer Collaborative Group. Endogenous sex hormones and prostate cancer: a collaborative analysis of 18 prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:170–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Muller RL, Gerber L, Moreira DM, Andriole G, Castro-Santamaria R, et al. Serum testosterone and dihydrotestosterone and prostate cancer risk in the placebo arm of the Reduction by Dutasteride of Prostate Cancer Events trial. Eur Urol. 2012;62:757–64. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shabsigh R, Crawford ED, Nehra A, Slawin KM. Testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men and potential prostate cancer risk: a systematic review. Int J Impot Res. 2009;21:9–23. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2008.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Agarwal PK, Oefelein MG. Testosterone replacement therapy after primary treatment for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2005;173:533–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000143942.55896.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kaufman JM, Graydon RJ. Androgen replacement after curative radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer in hypogonadal men. J Urol. 2004;172:920–2. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000136269.10161.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Khera M, Grober ED, Najari B, Colen JS, Mohamed O, et al. Testosterone replacement therapy following radical prostatectomy. J Sex Med. 2009;6:1165–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Morales A, Black AM, Emerson LE. Testosterone administration to men with testosterone deficiency syndrome after external beam radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer: preliminary observations. BJU Int. 2009;103:62–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pastuszak AW, Pearlman AM, Lai WS, Godoy G, Sathyamoorthy K, et al. Testosterone replacement therapy in patients with prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. J Urol. 2013;190:639–44. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sarosdy MF. Testosterone replacement for hypogonadism after treatment of early prostate cancer with brachytherapy. Cancer. 2007;109:536–41. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pastuszak AW, Pearlman AM, Godoy G, Miles BJ, Lipshultz LI, et al. Testosterone replacement therapy in the setting of prostate cancer treated with radiation. Int J Impot Res. 2013;25:24–8. doi: 10.1038/ijir.2012.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Calof OM, Singh AB, Lee ML, Kenny AM, Urban RJ, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone replacement in middle-aged and older men: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1451–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.11.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fabbri A, Giannetta E, Lenzi A, Isidori AM. Testosterone treatment to mimic hormone physiology in androgen replacement therapy. A view on testosterone gel and other preparations available. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2007;7:1093–106. doi: 10.1517/14712598.7.7.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gooren LJ, Bunck MC. Androgen replacement therapy: present and future. Drugs. 2004;64:1861–91. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464170-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang C, Swerdloff R, Kipnes M, Matsumoto AM, Dobs AS, et al. New testosterone buccal system (Striant) delivers physiological testosterone levels: pharmacokinetics study in hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3821–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Corona G, Rastrelli G, Forti G, Maggi M. Update in testosterone therapy for men. J Sex Med. 2011;8:639–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Dobs AS, Meikle AW, Arver S, Sanders SW, Caramelli KE, et al. Pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety of a permeation-enhanced testosterone transdermal system in comparison with bi-weekly injections of testosterone enanthate for the treatment of hypogonadal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:3469–78. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sih R, Morley JE, Kaiser FE, Perry HM, 3rd, Patrick P, et al. Testosterone replacement in older hypogonadal men: a 12-month randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:1661–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.6.3988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.McCullough AR, Khera M, Goldstein I, Hellstrom WJ, Morgentaler A, et al. A multi-institutional observational study of testosterone levels after testosterone pellet (Testopel(®)) insertion. J Sex Med. 2012;9:594–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kelleher S, Conway AJ, Handelsman DJ. Influence of implantation site and track geometry on the extrusion rate and pharmacology of testosterone implants. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;55:531–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Jockenhövel F, Vogel E, Kreutzer M, Reinhardt W, Lederbogen S, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of subcutaneous testosterone implants in hypogonadal men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1996;45:61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1996.tb02061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Pastuszak AW, Mittakanti H, Liu JS, Gomez L, Lipshultz LI, et al. Pharmacokinetic evaluation and dosing of subcutaneous testosterone pellets. J Androl. 2012;33:927–37. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.111.016295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Pfeil E, Dobs AS. Current and future testosterone delivery systems for treatment of the hypogonadal male. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5:471–81. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.4.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Jain P, Rademaker AW, McVary KT. Testosterone supplementation for erectile dysfunction: results of a meta-analysis. J Urol. 2000;164:371–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wilson DE, Kaidbey K, Boike SC, Jorkasky DK. Use of topical corticosteroid pretreatment to reduce the incidence and severity of skin reactions associated with testosterone transdermal therapy. Clin Ther. 1998;20:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Edelstein D, Sivanandy M, Shahani S, Basaria S. The latest options and future agents for treating male hypogonadism. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:2991–3008. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.17.2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Wang C, Berman N, Longstreth JA, Chuapoco B, Hull L, et al. Pharmacokinetics of transdermal testosterone gel in hypogonadal men: application of gel at one site versus four sites: a general clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:964–9. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.3.6437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rolf C, Knie U, Lemmnitz G, Nieschlag E. Interpersonal testosterone transfer after topical application of a newly developed testosterone gel preparation. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2002;56:637–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2002.01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Grober ED, Khera M, Soni SD, Espinoza MG, Lipshultz LI. Efficacy of changing testosterone gel preparations (Androgel or Testim) among suboptimally responsive hypogonadal men. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:213–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mattern C, Hoffmann C, Morley JE, Badiu C. Testosterone supplementation for hypogonadal men by the nasal route. Aging Male. 2008;11:171–8. doi: 10.1080/13685530802351974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Natesto (testosterone) nasal gel. Reference ID: 3514261. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/205488s000lbl .

- 136.Taxel P, Kennedy DG, Fall PM, Willard AK, Clive JM, et al. The effect of aromatase inhibition on sex steroids, gonadotropins, and markers of bone turnover in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:2869–74. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Raman JD, Schlegel PN. Aromatase inhibitors for male infertility. J Urol. 2002;167:624–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)69099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Leder BZ, Rohrer JL, Rubin SD, Gallo J, Longcope C. Effects of aromatase inhibition in elderly men with low or borderline-low serum testosterone levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1174–80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Liu PY, Wishart SM, Handelsman DJ. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of recombinant human chorionic gonadotropin on muscle strength and physical function and activity in older men with partial age-related androgen deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3125–35. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.7.8630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Hsieh TC, Pastuszak AW, Hwang K, Lipshultz LI. Concomitant intramuscular human chorionic gonadotropin preserves spermatogenesis in men undergoing testosterone replacement therapy. J Urol. 2013;189:647–50. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Katz DJ, Nabulsi O, Tal R, Mulhall JP. Outcomes of clomiphene citrate treatment in young hypogonadal men. BJU Int. 2012;110:573–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Moskovic DJ, Katz DJ, Akhavan A, Park K, Mulhall JP. Clomiphene citrate is safe and effective for long-term management of hypogonadism. BJU Int. 2012;110:1524–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.10968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ramasamy R, Scovell JM, Kovac JR, Lipshultz LI. Testosterone supplementation versus clomiphene citrate for hypogonadism: an age matched comparison of satisfaction and efficacy. J Urol. 2014;192:875–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Kaminetsky J, Hemani ML. Clomiphene citrate and enclomiphene for the treatment of hypogonadal androgen deficiency. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:1947–55. doi: 10.1517/13543780903405608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kaminetsky J, Werner M, Fontenot G, Wiehle RD. Oral enclomiphene citrate stimulates the endogenous production of testosterone and sperm counts in men with low testosterone: comparison with testosterone gel. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1628–35. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, Etzioni R, Freedland SJ, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2013;190:419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Saad F, Aversa A, Isidori AM, Zafalon L, Zitzmann M, et al. Onset of effects of testosterone treatment and time span until maximum effects are achieved. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165:675–85. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Coward RM, Simhan J, Carson CC., 3rd Prostate-specific antigen changes and prostate cancer in hypogonadal men treated with testosterone replacement therapy. BJU Int. 2009;103:1179–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Bhasin S, Singh AB, Mac RP, Carter B, Lee MI, et al. Managing the risks of prostate disease during testosterone replacement therapy in older men: recommendations for a standardized monitoring plan. J Androl. 2003;24:299–311. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.2003.tb02676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Tan RS, Salazar JA. Risks of testosterone replacement therapy in ageing men. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2004;3:599–606. doi: 10.1517/14740338.3.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]