Abstract

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are important small non-coding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression in cellular processes related to the pathogenesis of cancer. Genetic variation in miRNA genes could impact their synthesis and cellular effects and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are one example of genetic variants studied in relation to breast cancer. Studies aimed at identifying miRNA SNPs (miR-SNPs) associated with breast malignancies could lead towards further understanding of the disease and to develop clinical applications for early diagnosis and treatment.

Methods

We genotyped a panel of 24 miR-SNPs using multiplex PCR and chip-based matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) analysis in two Caucasian breast cancer case control populations (Primary population: 173 cases and 187 controls and secondary population: 679 cases and 301 controls). Association to breast cancer susceptibility was determined using chi-square (X2) and odds ratio (OR) analysis.

Results

Statistical analysis showed six miR-SNPs to be non-polymorphic and twelve of our selected miR-SNPs to have no association with breast cancer risk. However, we were able to show association between rs353291 (located in MIR145) and the risk of developing breast cancer in two independent case control cohorts (p = 0.041 and p = 0.023).

Conclusions

Our study is the first to report an association between a miR-SNP in MIR145 and breast cancer risk in individuals of Caucasian background. This finding requires further validation through genotyping of larger cohorts or in individuals of different ethnicities to determine the potential significance of this finding as well as studies aimed to determine functional significance.

Keywords: Association analysis, Breast cancer, microRNA, miR-SNPs, MIR145

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding single stranded RNA molecules (21 – 25 nucleotides) involved in negative regulation of gene expression [1, 2]. miRNAs are transcribed from long microRNA primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs) containing miRNA precursors (pre-miRNA, stem-loop molecules of 55 – 70 nucleotides). Pre-miRNAs are usually generated via the canonical pathway [3], where pri-miRNAs are cleaved by the complex formed by the nuclear ribonuclease (RNase) III DROSHA and the RNA-binding protein DCGR8 (DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8) [4]. Following transport to the cytoplasm by XPO5 (exportin5) and the nuclear protein ran-GTP, they are processed by DICER1 [5, 6]. The resultant duplex molecule contains both a single-stranded mature miRNA sequence and a complementary miRNA* strand which is released and degraded while the mature miRNA is loaded into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and merged into the Argonaute/EIFC2C (Ago) proteins [7, 8]. Each miRNA may bind to up to 200 gene targets and multiple binding sites for different miRNAs, making a highly complex web of interactions affecting a variety of biological pathways [9, 10].

miRNAs are very likely to play an important role in cancer biology due to their role in the regulation of important cellular processes including growth, differentiation and cell survival [11–16]. Several mechanisms result in changes in miRNA synthesis and expression in relation to cancer including: point mutations in miRNA and mRNA sequences, loss or mutation in the promoter regions for specific miRNA clusters, epigenetic changes and alterations in pathway related to dsRBD proteins [17–19]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in miRNA genes (miR-SNPs) are one example of point mutation (albeit one occurring in the past) that could affect miRNA function in one of three possible ways: altering transcription of the primary miRNA transcript; processing of the pri-miRNA and pre-miRNA and; through their effects on modulation of miRNA-mRNA interactions [20–23]. As a result miR-SNPs have been associated with different types of cancer, including chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, gastric, lung and thyroid carcinoma [24–27].

Breast cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide (1.67 million new cases, 25%) and the most common type of cancer for women in developed countries (793,684 new cases, 28%) [28]. Recent evidence suggests a role for miR-SNPs in breast cancer susceptibility including work by Hu et al. where the presence of mutant alleles of MIR196A2 rs11614913 and MIR499A rs3746444 significantly increased breast cancer risk in Chinese women [29]. However in genetic association analysis of Caucasian populations and functional studies in breast cancer cell lines performed by Hoffman et al. the presence of SNP in MIR196A2 rs11614913 was significantly associated with reduced risk of breast cancer, as well as less efficient processing of MIR196A2 and reduced capacity to regulate target genes, indicating additional factors may be at work in this SNP’s effect on breast cancer [30]. Additionally, Kontorovich et al. found 2 SNPs, rs6505162 and rs895819 located in MIR423 and MIR27A precursors respectively, to be significantly associated with decreased risk of breast cancer in BRCA2 mutation carriers from a Jewish population [31]. rs895819 was also significantly associated with reduced risk of developing breast cancer in families with a history of non-BRCA related breast cancer in a later study performed by Yang et al [32]. Finally rs2910164, a miR-SNP located in the 3p strand of MIR146A, was found to be associated with a younger age of diagnosis in familial breast cancer for BRCA1 mutation carriers [33].

In this study, we have investigated a panel of miR-SNPs present in miRNA genes previously identified to be involved in the pathophysiological mechanisms of breast cancer. Our initial selection included 24 variants located in 10 miRNA genes or in close proximity which were genotyped using multiplex PCR and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) analysis. Genotyping results of the 19 miR-SNPs successfully genotyped and included in this study identified six previously reported microRNA SNPs as non-polymorphic. From the remaining polymorphisms twelve miR-SNPs showed no significant differences between cases and controls and one variant in MIR145 was identified to be associated with breast cancer susceptibility in both of our Australian Caucasian breast cancer case-control populations.

Methods

Study populations

Two independent Australian Caucasian breast cancer case populations were available for our study: The Genomics Research Centre Breast Cancer (GRC-BC) population and part of the Griffith University-Cancer Council Queensland Breast Cancer Biobank (GU-CCQ BB). We conducted single nucleotide polymorphism genotyping in the GRC-BC population initially. This consisted of DNA samples from 173 breast cancer patients from South East Queensland and DNA samples from 187 healthy age and sex matched females with no personal and/or familial history of breast, ovarian or any other type of cancer collected at the Genomics Research Centre Clinic, Southport, with research approved by Griffith University’s Human Ethics Committee (Approval: MSC/07/08/HREC and PSY/01/11/HREC) and the Queensland University of Technology Human Research Ethics Committee (Approval: 1400000104). Breast cancer samples comprised prevalent breast cancer cases diagnosed previous to their inclusion in this study. All participants supplied informed written consent. Average age of test population was 57.52 years and 57 years for cases and controls respectively.

Further validation of genotyping results was performed on a subset of the GU-CCQ BB population. 679 DNA samples from breast cancer patients residing in Queensland with a diagnosis of invasive breast cancer confirmed histologically were used to validate genotyping of miR-SNPs. Patient samples had been collected by the Genomics Research Centre in collaboration with the Cancer Council of Queensland as part of a 5-year population-based longitudinal study since January 2010. Patients included in this study were between 33 and 80 years of age, with an average age of 60.16 and they were screened for personal and/or familial history of breast, ovarian or any other type of cancer. Control population for the GU-CCQ BB was established from 2 sources: The control group for this cohort was comprised of genotyping result data taken from 201 healthy females belonging to the phase 1 European population from the 1000Genomes project. Efforts were made to select a subgroup of individuals that were comparable to the case group in terms of age, ethnicity and sex [34].

Genomic DNA sample preparation from whole human blood

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood samples using a modified salting out method described previously [35, 36]. DNA samples were evaluated by spectrophotometry using the Thermo Scientific NanoDrop™ 8000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Wilmington, DE. USA) to determine DNA yield and 260/280 ratios [37–39]. Samples with a reading below 1.7 for their 260/280 ratio were purified using an ethanol precipitation protocol to guarantee DNA sample purity [40].

miRNA SNP selection

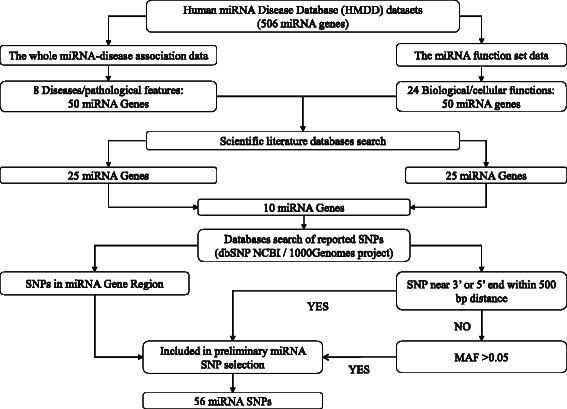

Figure 1 shows the selection process we followed to determine miRNA SNPs (miR-SNPs) that could be included in our study. Two datasets, “The whole miRNA-disease association data” and “The miRNA function set data” from the human miRNA disease database (HMMDD) created by Lu et al. [41] and updated in January 2012, were used to select 8 diseases and/or pathological characteristics and 24 biological and/or cellular functions related to breast cancer (See Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1, we picked the 50 miRNA genes from each dataset that were present in the majority of selected features for inclusion in the following steps. This list was narrowed down to the 25 miRNA genes on each dataset with the strongest evidence in order to maximise the potential for identification of biologically relevant molecules using two main criteria: miRNAs involved in the largest number of selected features from each group followed by a literature search to confirm the number of publications showing significant relationships to cancer biology or the possession of known functional effects of polymorphisms within the miRNA itself. Following this, we chose 10 miRNA genes from the 25 genes on both lists, again prioritising by number of functions and publications, and conducted a search to identify SNPs using both dbSNP database from The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [42] and 1000 Genomes project browser [43]. Final selection of SNPs was done using this algorithm: All microRNA-SNPs located inside the pre-miRNA gene were automatically included in the SNP selection. However, SNPs located outside of the pre-miRNA gene were assessed using the following criteria: miR-SNPs located up to 500bp upstream or downstream from pre-miRNA were automatically included in the SNP selection. On the other hand, SNPs located more than 500bp from the 3’ or 5’ end were chosen only if they had a previously reported minor allele frequency higher than 5% in Caucasian populations. As a result 56 microRNA SNPs were identified in this preliminary selection (Data not shown) (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

MicroRNA SNP (miR-SNP) selection algorithm using the Human miRNA Disease Database (HMDD). This flow chart shows workflow for selection of preliminary miR-SNPs included in genotyping study. Abbreviations: dbSNP, single nucleotide polymorphism database; MAF, minor allele frequency; miRNA, microRNA; NCBI National Center for Biotechnology Information; SNP, Single nucleotide polymorphisms

Table 1.

Selected features from the Human miRNA disease database (HMDD) included in present study

| Selected diseases and/or pathological features related to breast cancer | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA-disease association dataset | Human miRNA genes in dataset | 1. Adenocarcinoma | 5. Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| 503 | 2. Breast Neoplasms | 6. Neoplasms | |

| 3. Carcinoma | 7. Germ cell and embryonal neoplasm | ||

| Human Diseases in dataset | 4. Ductal breast carcinoma | 8. Squamous cell neoplasms | |

| 396 | |||

| Selected biological and/or cellular function in relation to Cancer | |||

| miRNA function dataset | Human miRNA genes in dataset | ||

| 503 | 1. Activation of caspases cascade | 13. Cell proliferation | |

| 2. Akt pathway | 14. Chemosensitivity of tumour cells | ||

| 3. Angiogenesis | 15. Chemotaxis | ||

| 4. Anti-cell proliferation | 16. Chromatin remodelling | ||

| 5. Apoptosis | 17. DNA Repair | ||

| 6. Cell cycle related | 18. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition | ||

| Biological and cellular functions in dataset | 7. Cell death | 19. Human embryonic stem cell (hESC) regulation | |

| 8. Cell differentiation | 20 Immune response | ||

| 9. Cell division | 21. Immune system | ||

| 10. Cell fate determination | 22. Inflammation | ||

| 43 | 11. Cell motility | 23 miRNA tumour suppressors | |

| 12. Cell proliferation | 24. Onco-miRNAs | ||

Primer design

Using the MassARRAY® Assay Design Suite v1.0 software (SEQUENOM Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) we were able to create a single multiplex PCR genotyping assay containing 24 miR-SNPs from our preliminary selection (See Table 2). We designed forward and reverse PCR primers and one iPLEX® (extension) primer and verified that the mass of extension primers differed by at least 30 Da among different SNPs and by 5 Da between alternative alleles of the same marker to achieve successful marker and allele identification by mass spectrometry analysis. Primers were manufactured by Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT®) Pte. Ltd. (Baulkham Hills, NSW 2153, Australia) and primer information is shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

List of the miRNA SNPs included in multiplex primer design using the MassARRAY® Assay Design Suite v1.0 software (SEQUENOM Inc., San Diego, CA, USA)

| miRNA | Locus | Location | SNPs in gene region | MAF | Location | SNPs near 3' end | MAF | Location | SNPs near 5' end | MAF | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIR210 | 11p15.5 | 568,089 - 568,198 | rs1062099 | 0.1877 | 567,627 | rs7395206 | 0.5000 | 568,211 | |||

| rs10902173 | 0.4835 | 570,072 | |||||||||

| MIR34A | 1p36.22 | 9,211,727 - 9,211,836 | rs35301225 | NA | 9,211,802 | rs77585961 | 0.0247 | 9,211,468 | |||

| MIR155 | 21q21.3 | 26,946,292 - 26,946,356 | rs2829801 | 0.4707 | 26,944,305 | rs1547354 | 0.0810 | 26,946,709 | |||

| MIR221 | Xp11.3 | 45,605,585 - 45,605,694 | rs7050391 | 0.0133 | 45,605,273 | rs2858061 | 0.4352 | 45,606,132 | |||

| rs2858060 | 0.4991 | 45,607,008 | |||||||||

| rs2858059 | 0.4786 | 45,607,190 | |||||||||

| MIR222 | Xp11.3 | 45,606,421 - 45,606,530 | rs2858061 | 0.4352 | 45,606,132 | rs2858060 | 0.4991 | 45,607,008 | |||

| rs2858059 | 0.4786 | 45,607,190 | |||||||||

| MIR21 | 17q23.1 | 57,918,627 - 57,918,698 | rs112394324 | 0.0032 | 57,918,251 | rs1292037 | 0.2440 | 57918908 | |||

| rs3851812 | 0.0371 | 57,918,370 | rs13137 | 0.2440 | 57919031 | ||||||

| MIRLET7A1 | 9q22.32 | 96,938,239 - 96,938,318 | rs10761322 | 0.4588 | 96,937,478 | ||||||

| rs10739971 | 0.2601 | 96,937,680 | |||||||||

| MIRLET7A2 | 11q24.1 | 122,017,230 - 122,017,301 | rs629367 | 0.1451 | 122,017,014 | rs1143770 | 0.4867 | 122,017,598 | |||

| rs562052 | 0.3265 | 122,018,550 | |||||||||

| rs693120 | 0.3265 | 122,019,011 | |||||||||

| MIR145 | 5q32 | 148,810,209 - 148,810,296 | rs55945735 | 0.2010 | 148,809,158 | rs353291 | 0.3324 | 148,810,746 | |||

| rs73798217 | 0.0545 | 148,809,918 |

Table 3.

Primer sequences for the miRNA SNPs included in genotyping study using multiplex PCR reaction and MALDI-TOF MS

| SNP | Forward primer sequence | Reverse primer sequence | iPLEX® (Extension) primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs2829801 | ACGTTGGATGTTCCCACTCAGGCATATAGC | ACGTTGGATGTGGAGTCTATGTCCACTTCC | TGGGCTAAGCAACCA |

| rs7395206 | ACGTTGGATGTCGGACGCCCAAGTTGGAG | ACGTTGGATGTCACACGCACAGTGGGTCT | GGTGGGCGGGCGGAG |

| rs73798217 | ACGTTGGATGACTGGAGGTTATCAGAGAGG | ACGTTGGATGATGTGTATTCCCCAGTCTCC | ACCATTCAGTTCCTAGC |

| rs353291 | ACGTTGGATGGTAGAGATGCCACAAGAGGG | ACGTTGGATGAAACCTTAAGTCTTCGTTCG | GGTTGTTCTCTGGCTGC |

| rs55945735 | ACGTTGGATGGGTCTCAAACTCCTGACTTC | ACGTTGGATGCTGCATCTGAGCACTTCAAG | TGATGCCTGGCGGGGCG |

| rs10902173 | ACGTTGGATGTCACAGGCACCTTTTCTCAG | ACGTTGGATGGAAGCCTGGGTATTAGGATG | ACCTTTTCTCAGCATCTG |

| rs112394324 | ACGTTGGATGACTGGAGAGAGAAATTACCC | ACGTTGGATGGTTGAAACCAGAGTACATGC | CAGATACGACAGAGTGTG |

| rs1292037 | ACGTTGGATGTACAGCTAGAAAAGTCCCTG | ACGTTGGATGGGAGGGAGGATTTTATGGAG | AACCTTTTCAAAACCCACA |

| rs562052 | ACGTTGGATGCTCCAGGCTAGTGGAATAAC | ACGTTGGATGCTACTGCACTGATCGTGTTC | CAGATTCAAATGCCATAGCA |

| rs2858059 | ACGTTGGATGCAGTAAGTATTTCTGGGGTG | ACGTTGGATGCTCCCATGATACAATGAAGG | TGGGGTGGATAAATGAATAG |

| rs1062099 | ACGTTGGATGGACCCGGTCCTGATTTTAAC | ACGTTGGATGTGTGTTTCTGCCGCTTCAGT | TTTAACAGTAGACTTGAGAAG |

| rs10739971 | ACGTTGGATGCCTAATAAGACCACTTAGTGT | ACGTTGGATGATGCACTAACATACAACGAG | CCACCTACTCATTTATCCCATG |

| rs2858060 | ACGTTGGATGACTGTATTATCCTCAGTTC | ACGTTGGATGACTTGGGTAATCTAGCAATG | GTATTATCCTCAGTTCGTAACA |

| rs2858061 | ACGTTGGATGGCTTTCAATACTACAAGGG | ACGTTGGATGAATGATACCTTTCATAGGGG | GTAAAACAAAAACAGGTAAGAG |

| rs35301225 | ACGTTGGATGGGCAGTATACTTGCTGATTG | ACGTTGGATGGCTGTGAGTGTTTCTTTGGC | GGATTATTGCTCACAACAACCAG |

| rs1547354 | ACGTTGGATGTTGCAGGTTTTGGCTTGTTC | ACGTTGGATGGGAGGTTAGTAGTCCTTCTA | TTTGATTCAACTGTTAGAAATGTG |

| rs13137 | ACGTTGGATGAGGTGAAAGAGATGAACCAC | ACGTTGGATGAAAGCATTCCCAAAATGCTC | TCCCAAAATGCTCTATTTTAGATAG |

| rs10761322 | ACGTTGGATGGCTTTTGGTTACTAAATCAC | ACGTTGGATGCTTCATATTTAGGAGGTAGC | GGCATATTTAGGAGGTAGCTACTAC |

| rs693120 | ACGTTGGATGGTAGATGGCACATATAGAAA | ACGTTGGATGCATCCCTTAACTGTAAGTTC | GATTGTCAAATGAAAAGAAGAATAT |

| rs1143770 | ACGTTGGATGCTGAACAATTTAATGCCTTC | ACGTTGGATGTTCAGTTTTACCAGAGGAAC | CCCCCATGCCTTCTGATATCTGTTGA |

| rs77585961 | ACGTTGGATGGTTTCCTTCTCTGCAAGACG | ACGTTGGATGCACTTACTATGCAGGAAGGC | CCTACATGATGTAATACACTTACAATA |

| rs7050391 | ACGTTGGATGGTAAGGCAGTATGATTAGGC | ACGTTGGATGGCCTCAACTGTCAAAGATTG | TGTTCATAATTATTATCAGAAGGCATA |

| rs3851812 | ACGTTGGATGTTTTCCTCCCAAGCAAAAC | ACGTTGGATGTTCTTGCCGTTCTGTAAGTG | GGTGGAAGTGTTTTATTCTTAGTGTGA |

| rs629367 | ACGTTGGATGTATGCAGCATTTTTGTGAC | ACGTTGGATGATTCTGTTTCCTCGGGTTAG | GGGGTCAGCATTTTTGTGACAATGGACA |

Primary multiplex PCR

Genotyping was undertaken following the iPLEX™ GOLD genotyping protocol using the iPLEX® Gold Reagent Kit (SEQUENOM Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Primer extension reactions were performed according to the instructions for the SEQUENOM linear adjustment method included in the iPLEX™ GOLD genotyping protocol (SEQUENOM Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All reactions were performed using Applied Biosystems® MicroAmp® EnduraPlate™ Optical 96-Well Clear Reaction Plates with Barcode (Life Technologies Australia Pty Ltd., Mulgrave, VIC, Australia) and an Applied Biosystems® Veriti® 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Life Technologies Australia Pty Ltd., Mulgrave, VIC, Australia).

MALDI-TOF MS analysis and data analysis

A total of 12-16 nl of each iPLEX® reaction product were transferred onto a SpectroCHIP® II G96 (SEQUENOM Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) using SEQUENOM® MassARRAY® Nanodispenser (SEQUENOM Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). SpectroCHIP® analysis was carried out by SEQUENOM® MassArray® Analyzer 4 and the SpectroAcquire software Version 4.0 (SEQUENOM Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Finally data analysis for genotype determination was done using the MassARRAY® Typer software version 4.0 (SEQUENOM Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). In order to confirm the genotypes obtained, randomly selected samples (5 each for case and control cohorts) from each genotype (n = 240) were validated by Sanger Sequencing to ensure accuracy of genotyping results. In all cases, the Sanger Sequencing confirmed the genotyping obtained using MassARRAY.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of genotypes and alleles was conducted using Plink software version 1.07 (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/) [44]. The α for p-values was set at 0.05 to determine statistically significant association with breast cancer. Genotype and allele frequencies for each miRNA SNP in our case and control populations were established and we used Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) to evaluate deviation between observed and expected frequencies for identification of unexpected population or genotyping biases [45, 46]. We performed Chi square analysis to evaluate differences in genotype and allele frequencies between cases and controls for each independent population [47]. Finally we calculated odds ratio (OR) and obtained 95% confidence interval (CI) 95% to assess disease risk.

Results and discussion

MicroRNAs are some of the small non-coding RNA molecules responsible for gene regulation at the translational level. They require a very complex series of nuclear and cytoplasmic processes for their synthesis and to achieve their functional effects on genes involved in key cellular functions like replication and cell differentiation [7, 10, 13]. As a result they are likely to play a role in the development and progression of cancer due to the important biological mechanisms they regulate [12, 15, 16]. They have been shown to have different roles in various types of cancer including breast cancer [18, 24]. Breast cancer is a cause for concern since recent reports by the IARC show it has very high incidence and mortality rates around the world [28]. Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms in well-defined case control cohorts has provided information on miR-SNPs involved in the pathophysiology of different types of cancer including breast cancer [25–27, 29–33]. Therefore we selected a panel of 24 miR-SNPs related to 9 miRNA genes previously identified to play a role in breast cancer to genotype in our Australian Caucasian breast cancer case control populations. Genotyping of our selected miRNA variants in the GRC-BC cohort showed six of them to be non-polymorphic (rs73798217, rs112394324, rs35301225, rs1547354, rs7050391 and rs3851812) and another five of the chosen miR-SNPs failed to successfully deliver genotypes (rs2829801, rs7395206, rs2858059, rs1143770 and rs77585961).

On the other hand, genotype and allele frequencies of the remaining 13 miR-SNPs in the GRC-BC cases and controls showed these to be closely similar to those found in Hapmap for Caucasian populations and they were also in Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) (p > 0.05). Ultimately, however, chi-square analysis of genotyping results of 12 SNPs located in relation to seven miRNAs (MIR210, MIR221, MIR222, MIR21, MIRLET7A1, MIRLET7A2 and MIR145) showed no significant differences for genotype and allele frequencies between cases and controls in our GRC-BC population (See Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9).

Table 4.

Allele and genotype frequencies for miRNA SNPs in MIR210 obtained from the GRC-BC population

| rs1062099 | rs10902173 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Genotype | Allele | Genotype | |||||||||||

| G (%) | C (%) | p-value | GG (%) | CG (%) | CC (%) | p-value | C (%) | T (%) | p-value | CC (%) | TC (%) | TT (%) | p-value | |

| Control | 300 (83.3) | 60 (16.7) | 0.36 | 126 (70.0) | 48 (26.7) | 6 (3.3) | 0.61 | 203 (59.0) | 141 (41.0) | 0.93 | 63 (36.6) | 90 (49.5) | 29 (15.9) | 0.64 |

| Cases | 263 (80.7) | 63 (19.3) | 106 (65.0) | 51 (31.3) | 6 (3.7) | 216 (59.3) | 148 (40.7) | 63 (34.6) | 77 (44.8) | 32 (18.6) | ||||

| Hapmap (%) | 81.7 | 18.3 | 66.8 | 29.8 | 3.4 | 60.4 | 39.6 | 34.8 | 51.2 | 14.0 | ||||

Table 5.

Allele and genotype frequencies for miRNA SNPs in MIR221 and MIR222 from the GRC-BC Population

| rs2858061 | rs2858060 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Genotype | Allele | Genotype | |||||||||||

| G (%) | C (%) | p-value | GG (%) | CG (%) | CC (%) | p-value | C (%) | G (%) | p-value | CC (%) | GC (%) | GG (%) | p-value | |

| Control | 323 (87.8) | 45 (12.2) | 0.43 | 142 (77.2) | 39 (21.2) | 3 (1.6) | 0.38 | 219 (69.3) | 97 (30.7) | 0.75 | 81 (51.3) | 57 (36.1) | 20 (12.7) | 0.35 |

| Cases | 295 (85.8) | 49 (14.2) | 130 (75.6) | 35 (20.3) | 7 (4.1) | 218 (68.1) | 102 (31.9) | 74 (46.3) | 70 (43.8) | 16 (10.0) | ||||

| Hapmap (%) | 86.2 | 13.8 | 80.2 | 12.4 | 7.4 | 72.8 | 27.2 | 62.3 | 20.6 | 17.2 | ||||

Table 6.

Allele and genotype frequencies for miRNA SNPs in MIR21 obtained from the GRC-BC population

| rs1292037 | rs13137 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Genotype | Allele | Genotype | |||||||||||

| A (%) | G (%) | p-value | AA (%) | GA (%) | GG (%) | p-value | T (%) | A (%) | p-value | TT (%) | AT (%) | AA (%) | p-value | |

| Control | 300 (80.6) | 72 (19.4) | 0.86 | 122 (65.6%) | 56 (30.1) | 8 (4.3) | 0.95 | 299 (80.8) | 71 (19.2) | 0.85 | 122 (65.9) | 55 (29.7) | 8 (4.3) | 0.94 |

| Cases | 274 (80.1) | 68 (19.9) | 110 (64.3) | 54 (31.6) | 7 (4.1) | 276 (80.2) | 68 (19.8) | 111 (64.5) | 54 (31.4) | 7 (4.1) | ||||

| Hapmap (%) | 81.0 | 19.0 | 65.4 | 31.1 | 3.4 | 81.0 | 19.0 | 65.4 | 31.1 | 3.4 | ||||

Table 7.

Allele and genotype frequencies for miRNA SNPs in MIRLET7A1 obtained from the GRC-BC cohort

| rs10761322 | rs10739971 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Genotype | Allele | Genotype | |||||||||||

| T (%) | C (%) | p-value | TT (%) | TC (%) | CC (%) | p-value | G (%) | A (%) | p-value | GG (%) | AG (%) | AA (%) | p-value | |

| Control | 225 (61.8) | 139 (38.2) | 0.73 | 76 (41.8) | 73 (40.1) | 33 (18.1) | 0.08 | 243 (67.5) | 117 (32.5) | 0.39 | 89 (49.4) | 65 (36.1) | 26 (14.4) | 0.36 |

| Cases | 207 (60.5) | 135 (39.5) | 59 (34.5) | 89 (52.0) | 23 (13.5) | 223 (64.5) | 123 (35.5) | 74 (42.8) | 75 (43.4) | 24 (13.9) | ||||

| Hapmap (%) | 61.9 | 38.1 | 40.9 | 42.0 | 17.2 | 68.1 | 31.9 | 46.4 | 43.3 | 10.3 | ||||

Table 8.

Allele and genotype frequencies for miRNA SNPs in MIRLET7A2 obtained from the GRC-BC population

| rs629367 | rs562052 | rs693120 | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Genotype | Allele | Genotype | Allele | Genotype | ||||||||||||||||

| A (%) | C (%) | p-value | AA (%) | CA (%) | CC (%) | p-value | G (%) | A (%) | p-value | GG (%) | AG (%) | AA (%) | p-value | G (%) | A (%) | p-value | GG (%) | AG (%) | AA (%) | p-value | |

| Control | 302 (82.5) | 64 (17.5) | 0.72 | 125 (68.3) | 52 (28.4) | 6 (3.3) | 0.88 | 242 (65.4) | 128 (34.6) | 0.76 | 81 (43.8) | 80 (43.2) | 24 (13.0) | 0.57 | 230 (67.3) | 112 (32.7) | 0.77 | 82 (48.0) | 66 (38.6) | 23 (13.5) | 0.21 |

| Cases | 289 (83.5) | 57 (16.5) | 122 (70.5) | 45 (26.0) | 6 (3.5) | 230 (66.5) | 116 (33.5) | 74 (42.8) | 82 (47.4) | 17 (9.8) | 225 (66.2) | 115 (33.8) | 72 (42.4) | 81 (47.6) | 17 (10.0) | ||||||

| Hapmap (%) | 84.6 | 15.4 | 75.4 | 18.5 | 6.2 | 68.1 | 31.9 | 46.2 | 43.8 | 10.0 | 68.1 | 31.9 | 46.2 | 43.8 | 10.0 | ||||||

Table 9.

Allele and genotype frequencies for rs55945735 located in MIR145 obtained from the GRC-BC population

| rs55945735 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Genotype | ||||||

| A (%) | G (%) | p-value | AA (%) | GA (%) | GG (%) | p-value | |

| Control | 193 (59.9) | 129 (40.1) | 0.29 | 61 (37.9) | 71 (44.1) | 29 (18.0) | 0.58 |

| Cases | 182 (64.1) | 102 (35.9) | 60 (42.3) | 62 (43.7) | 20 (14.1) | ||

| Hapmap (%) | 62.8 | 37.2 | 38.3 | 49.1 | 12.7 | ||

In contrast, we were able to determine significant differences at the allelic level for rs353291 after chi-square analysis in our GRC-BC cohort (p = 0.041) although no significant difference in genotype frequencies (p = 0.09) (See Table 10). We then proceeded to genotype this SNP in the GU-CCQ BB population and we also found the genotype and allele frequencies closely matched Hapmap frequencies for Caucasian populations and cases and controls were in HWE. Statistical analysis of genotyping in our replication population showed similar findings to those obtained in the GRB-BC cohort shown in Table 10. We were able to find significant differences in allele frequencies between cases and controls in the GU-CCQ BB population (p = 0.006) and also statistically significant differences at the genotype level (p = 0.02). Finally we calculated odds ratios for alleles in the GRC-BC and GU-CCQ BB populations to be 1.37 (CI 95%: 1.01–1.84) and 1.31 (CI 95%: 1.04–1.70) respectively, suggesting the presence of the C allele at this locus increases the risk of developing breast cancer. However it should be noted that if we consider multiple testing, our finding for the analysis of allele frequencies for both populations for this variant is not significant if we determine Bonferroni correction of the α for p-value to be 2.08 x 10−3. However these results are still potentially interesting particularly considering the similarity of allelic significance in both independent case-control cohorts and point to the need for further genotyping in extended populations.

Table 10.

Allele and genotype frequencies for SNP rs353291 located in MIR145 obtained from the GRC-BC and GU-CCQ BB cohorts

| GRC-BC population | GU-CCQ BB population | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Genotype | Allele | Genotype | |||||||||||

| A (%) | G (%) | p-value | AA (%) | GA (%) | GG (%) | p-value | A (%) | G (%) | p-value | AA (%) | GA (%) | GG (%) | p-value | |

| Control | 211 (58.6) | 149 (41.4) | 0.041 | 61 (33.9) | 89 (49.4) | 30 (16.7) | 0.09 | 386 (62.7) | 230 (37.3) | 0.023 | 128 (41.6) | 130 (42.2) | 50 (16.2) | 0.07 |

| Cases | 171 (50.9) | 165 (49.1) | 40 (23.8) | 91 (54.2) | 37 (22.0) | 769 (57.2) | 575 (42.8) | 229 (34.1) | 311 (46.3) | 132 (19.6) | ||||

| Hapmap (%) | 62.7 | 37.3 | 40.6 | 44.1 | 15.3 | 62.7 | 37.3 | 40.6 | 44.1 | 15.3 | ||||

miR-SNP rs353291 is located 450 bp upstream from the MIR145 gene, inside the miRNA 143 host gene transcript, in the long arm of chromosome 5 region 32 at position 148,810,746. To the best of our knowledge there are no previous association studies in relation to this miR-SNP and breast cancer risk in Caucasians or any populations of other ethnicities. However, MIR145 has been previously reported to play a role in cancer biogenesis and progression. Downregulation of MIR145 is a common finding previously reported in colorectal [48, 49], bladder [50], lung [51, 52] and oesophageal [53] cancers possibly leading to poor prognosis. Similarly, it has also been found to have a tumour suppressor role in breast tissue particularly in the myoepithelial/basal cell compartment and it is found to be downregulated in breast cancer tissue samples [54–56]. Research using breast cancer cell lines showed it regulates genes involved in modulation of apoptosis [57, 58]. Finally downregulation of MIR145 has been associated with a more aggressive behaviour of breast malignancies based on results performed in both breast cancer cell line and tissue samples [59, 60]. However the molecular mechanisms leading to decreased expression of MIR145 still remain unknown and our finding could potentially help to provide further knowledge on these mechanisms through further functional validation on breast cancer cell culture and/or animal/models. It is also possible that rs353291 is linked to a different nearby SNP not considered in this research that may have direct functional effects on MIR145, so additional sequencing/genotyping studies may need to be performed prior to functional assessment of the link between rs353291 and breast cancer.

Conclusions

We were able to determine that the presence of a polymorphism in miR-SNP rs353291 is associated with an increased risk of developing breast cancer based on our findings. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on breast cancer risk association for this variant in individuals of Caucasian background. This finding could potentially explain the previously described role that MIR145 plays in breast cancer documented in the literature, but it requires confirmation via functional studies using cell culture or animal models. It also requires further validation on larger Caucasian population as well as in cohorts of individuals with different ethnical backgrounds before it can be translated into clinical applications used in breast cancer diagnosis or treatment.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by research grants from the Griffith Health Institute, the Cancer Council Queensland and funding from the national Health and Medical Research Council. Blood samples from the Griffith University-Cancer Council Queensland Biobank were collected from patients enrolled in Cancer Council Queensland’s Breast Cancer Outcomes Study funded by a Cancer Australia grant (#1006339). Dr Youl is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Research Fellowship (#1054038). We thank Professor Suzanne K. Chambers for her assistance in the development of this project. In addition, this study used infrastructure provided by the Australian government EIF Super Science Funds as part of the Therapeutic Innovation Australia – Queensland node project.

Abbreviations

- 3’-UTR

3’ untranslated region

- CI

Confidence interval

- DCGR8

DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- dNTP

Deoxynucleoside triphosphate

- ddNTP

Dideoxynucleoside-5’-triphosphate

- dsRBD

Double-stranded RNA binding domain

- HMMDD

Human miRNA disease database

- HWE

Weinberg equilibrium

- IARC

International Agency for Research on Cancer

- mM

Milimolar

- mRNA

Messenger RNA

- miRNAS

MicroRNAs

- miR-SNP

MicroRNA single nucleotide polymorphism

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- MALDI-TOF

Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- RNA

Ribonucleic Acid

- RNase

Ribonuclease

- SAP

Shrimp alkaline phosphatase

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphisms

- XPO5

Exportin-5

- μM

Micromolar

- μl

Microlitres

- °C

Celsius

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors’ declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Diego Chacon-Cortes performed most experimental work and produced the primary script for the paper. Robert A. Smith assisted in assay design and optimisation and provided advice on manuscript editing. Rodney A. Lea assisted in statistical analysis and provided advice on manuscript editing. Larisa M Haupt assisted in data interpretation, manuscript editing and finalisation. Philippa H Youl assisted in recruitment of the replication population and provided organisation for replicate data entry for control matching. Lyn R. Griffiths provided advice on study design, laboratory oversight, recruited the primary population and provided advice on manuscript editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75(5):843–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403(6772):901–6. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westholm JO, Lai EC. Mirtrons: microRNA biogenesis via splicing. Biochimie. 2011;93(11):1897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Rådmark O, Kim S et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. In., vol. 425: Nature. 2003;425(6956):415-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003;17(24):3011–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E, Norman J, Cooch N, Nishikura K, Shiekhattar R. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature. 2005;436(7051):740–4. doi: 10.1038/nature03868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee JT, Kim S, Kim VN. MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 2002;21(17):4663–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khvorova A, Reynolds A, Jayasena SD. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell. 2003;115(2):209–16. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajewsky N. microRNA target predictions in animals. Nat Genet. 2006;38 Suppl:S8-13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Target Recognition and Regulatory Functions. Cell. 2009;136(2):215–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281–97. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang B, Pan X, Cobb GP, Anderson TA. microRNAs as oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Dev Biol. 2007;302(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang B, Wang Q, Pan X. MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in animals and plants. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210(2):279–89. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu Z, Baserga R, Chen L, Wang C, Lisanti MP, Pestell RG. microRNA, Cell Cycle, and Human Breast Cancer. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(3):1058–64. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robbins SL, Kumar V, Cotran RS. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farazi TA, Spitzer JI, Morozov P, Tuschl T. miRNAs in human cancer. J Pathol. 2011;223(2):102–15. doi: 10.1002/path.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim VN. MicroRNA biogenesis: coordinated cropping and dicing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(5):376–85. doi: 10.1038/nrm1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynam-Lennon N, Maher SG, Reynolds JV. The roles of microRNA in cancer and apoptosis. Biol Rev. 2009;84(1):55–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2008.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ha M, Kim VN. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(8):509–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duan S, Mi S, Zhang W, Dolan ME. Comprehensive analysis of the impact of SNPs and CNVs on human microRNAs and their regulatory genes. RNA Biol. 2009;6(4):412–25. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.4.8830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun G, Yan J, Noltner K, Feng J, Li H, Sarkis DA, Sommer SS, Rossi JJ. SNPs in human miRNA genes affect biogenesis and function. RNA. 2009;15(9):1640–51. doi: 10.1261/rna.1560209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan BM, Robles AI, Harris CC. Genetic variation in microRNA networks: the implications for cancer research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(6):389–402. doi: 10.1038/nrc2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee H-C, Yang C-W, Chen C-Y, Au L-C. Single point mutation of microRNA may cause butterfly effect on alteration of global gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;404(4):1065–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(11):857–66. doi: 10.1038/nrc1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jazdzewski K, Murray EL, Franssila K, Jarzab B, Schoenberg DR, Chapelle A. Common SNP in Pre-miR-146a Decreases Mature miR Expression and Predisposes to Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(20):7269–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802682105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun Q, Gu H, Zeng Y, Xia Y, Wang Y, Jing Y, Yang L, Wang B. Hsa-mir-27a genetic variant contributes to gastric cancer susceptibility through affecting miR-27a and target gene expression. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(10):2241–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Z, Chen J, Tian T, Zhou X, Gu H, Xu L, Zeng Y, Miao R, Jin G, Ma H, et al. Genetic variants of miRNA sequences and non–small cell lung cancer survival. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(7):2600–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI34934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer [http://globocan.iarc.fr].

- 29.Hu Z, Liang J, Wang Z, Tian T, Zhou X, Chen J, Miao R, Wang Y, Wang X, Shen H. Common genetic variants in pre-microRNAs were associated with increased risk of breast cancer in Chinese women. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(1):79–84. doi: 10.1002/humu.20837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoffman AE, Zheng T, Yi C, Leaderer D, Weidhaas J, Slack F, Zhang Y, Paranjape T, Zhu Y. microRNA miR-196a-2 and Breast Cancer: A Genetic and Epigenetic Association Study and Functional Analysis. Cancer Res. 2009;69(14):5970–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kontorovich T, Levy A, Korostishevsky M, Nir U, Friedman E. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in miRNA binding sites and miRNA genes as breast/ovarian cancer risk modifiers in Jewish high-risk women. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(3):589–97. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang R, Schlehe B, Hemminki K, Sutter C, Bugert P, Wappenschmidt B, Volkmann J, Varon R, Weber BH, Niederacher D, et al. A genetic variant in the pre-miR-27a oncogene is associated with a reduced familial breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;121(3):693–702. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0633-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shen J, Ambrosone CB, DiCioccio RA, Odunsi K, Lele SB, Zhao H. A functional polymorphism in the miR-146a gene and age of familial breast/ovarian cancer diagnosis. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(10):1963–6. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, Kang HM, Marth GT, McVean GA. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491(7422):56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chacon-Cortes D, Haupt LM, Lea RA, Griffiths LR. Comparison of genomic DNA extraction techniques from whole blood samples: a time, cost and quality evaluation study. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(5):5961–6. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1408-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nasiri H, Forouzandeh M, Rasaee MJ, Rahbarizadeh F. Modified salting-out method: high-yield, high-quality genomic DNA extraction from whole blood using laundry detergent. J Clin Lab Anal. 2005;19(6):229–32. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chacon-Cortes D, Griffiths LR. Methods for extracting genomic DNA from whole blood samples: current perspectives. J Biorepository Sci Appl Med. 2014;2:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huberman JA. Importance of measuring nucleic acid absorbance at 240 nm as well as at 260 and 280 nm. Biotechniques. 1995;18(4):636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahota A, Brooks AI, Tischfield JA, King IB. Preparing DNA from blood for genotyping. CSH Protoc. 2007;2007:pdb.prot4830. doi:10.1101/pdb.prot4830 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbour, New York 2001.

- 41.Lu M, Zhang Q, Deng M, Miao J, Guo Y, Gao W, Cui Q. An Analysis of Human MicroRNA and Disease Associations. PLoS One. 2008;3(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholodov M, Baker J, Phan L, Smigielski EM, Sirotkin K. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(1):308–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Consortium GP. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature. 2012;491(7422):56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo SW, Thompson EA. Performing the exact test of Hardy-Weinberg proportion for multiple alleles. Biometrics. 1992;361–372. [PubMed]

- 46.Hardy GH. Mendelian proportions in a mixed population. Science. 1908;28(706):49–50. doi: 10.1126/science.28.706.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fisher SRA, Yates F. Statistical Tables for Biological, Agricultural and Medical Research… revised and enlarged: Oliver & Boyd; 1963.

- 48.Arndt G, Dossey L, Cullen L, Lai A, Druker R, Eisbacher M, Zhang C, Tran N, Fan H, Retzlaff K, et al. Characterization of global microRNA expression reveals oncogenic potential of miR-145 in metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9(1):374. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michael MZ, O' Connor SM, van Holst Pellekaan NG, Young GP, James RJ. Reduced Accumulation of Specific MicroRNAs in Colorectal Neoplasia. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1(12):882–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chiyomaru T, Enokida H, Tatarano S, Kawahara K, Uchida Y, Nishiyama K, Fujimura L, Kikkawa N, Seki N, Nakagawa M. miR-145 and miR-133a function as tumour suppressors and directly regulate FSCN1 expression in bladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(5):883–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho WCS, Chow ASC, Au JSK. Restoration of tumour suppressor hsa-miR-145 inhibits cancer cell growth in lung adenocarcinoma patients with epidermal growth factor receptor mutation. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(12):2197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cho WCS, Chow ASC, Au JSK. MiR-145 inhibits cell proliferation of human lung adenocarcinoma by targeting EGFR and NUDT1. RNA Biol. 2011;8(1):125–31. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.1.14259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kano M, Seki N, Kikkawa N, Fujimura L, Hoshino I, Akutsu Y, Chiyomaru T, Enokida H, Nakagawa M, Matsubara H. miR-145, miR-133a and miR-133b: Tumor-suppressive miRNAs target FSCN1 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2804–14. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Liu C-G, Veronese A, Spizzo R, Sabbioni S, Magri E, Pedriali M, Fabbri M, Campiglio M, et al. MicroRNA Gene Expression Deregulation in Human Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65(16):7065–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sempere LF, Christensen M, Silahtaroglu A, Bak M, Heath CV, Schwartz G, Wells W, Kauppinen S, Cole CN. Altered MicroRNA Expression Confined to Specific Epithelial Cell Subpopulations in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67(24):11612–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu C-G, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(7):2257–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spizzo R, Nicoloso MS, Lupini L, Lu Y, Fogarty J, Rossi S, Zagatti B, Fabbri M, Veronese A, Liu X, et al. miR-145 participates with TP53 in a death-promoting regulatory loop and targets estrogen receptor-alpha in human breast cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17(2):246–54. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang S, Bian C, Yang Z, Bo Y, Li J, Zeng L, Zhou H, Zhao RC. miR-145 inhibits breast cancer cell growth through RTKN. Int J Oncol. 2009;34(5):1461–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goette M, Mohr C, Koo CY, Stock C, Vaske AK, Viola M, Ibrahim SA, Peddibhotla S, Teng YHF, Low JY, et al. miR-145-dependent targeting of Junctional Adhesion Molecule A and modulation of fascin expression are associated with reduced breast cancer cell motility and invasiveness. Oncogene. 2010;29(50):6569–80. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Radojicic J, Zaravinos A, Vrekoussis T, Kafousi M, Spandidos DA, Stathopoulos EN. MicroRNA expression analysis in triple-negative (ER, PR and Her2/neu) breast cancer. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(3):507–17. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.3.14754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]