Abstract

Investigations were carried out on the carbon-dots (C-dots) based fluorescent off - on (Fe3 + - S2O32−) and on - off (Zn2 + - PO43−) sensors for the detection of metal ions and anions. The sensor system exhibits excellent selectivity and sensitivity towards the detection of biologically important Fe3 + , Zn2 + metal ions and S2O32−, PO43− anions. It was found that the functional group on the C-dots surface plays crucial role in metal ions and anions detection. Inspired by the sensing results, we demonstrate C-dots based molecular logic gates operation using metal ions and anions as the chemical input. Herein, YES, NOT, OR, XOR and IMPLICATION (IMP) logic gates were constructed based on the selection of metal ions and anions as inputs. This carbon-dots sensor can be utilized as various logic gates at the molecular level and it will show better applicability for the next generation of molecular logic gates. Their promising properties of C-dots may open up a new paradigm for establishing the chemical logic gates via fluorescent chemosensors.

Recently, chemical based molecular logic gates received extensive attention due to its fascinating significance for the development of molecular-scale electronic devices, which perform Boolean logic operations in response to chemical inputs. So far several groups have demonstrated the construction of the molecular logic gates by using different materials such as nucleic acids1,2,3,4,5,6, proteins7,8, and organic molecules9,10,11,12. Recently, Feng et al. reported that spermine-functionalized C-dots can influence DNA structure to induce DNA B-Z transition and perform DNA logic operations13. Despite the promising performance of the DNA molecule, it is necessary to investigate the new materials which show better applicability for the next generation molecular logic gates. Herein we report the new C-dots based logic gates and illustrate their application for the logic functions of OR, XOR and IMP. C-dots exhibits tremendous characteristics such as non-toxicity, biocompatibility, photostability, facile, rapid and low cost for synthesis, easy for surface modification, and excellent luminescence properties14,15,16,17,18. Due to these unique properties, developing C-dots as a new material to perform logic operations should be worthwhile.

Among several methods (e.g. luminescence, colorimetric and electrochemical), photoluminescence is a broadly used characterization technique for logic devices because of its characteristics such as high sensitivity, simple and fast response5,10,19,20,21. We establish the C-dots based fluorescence off-on and on-off sensors which sense the metal ions as well as anions in pH 7.2 HEPES-buffered water solution. In this study, carboxylate and amine functionalized C-dots (for convenience, C-dots/COOH and C-dots/NH2 named as C-dots1 and C-dots2, respectively, thereafter) are acted as fluorescent probes and several metal ions (Ti2 + , Cr2 + , Mn2 + , Fe2 + , Fe3 + , CO2 + , Ni2 + , Cu2 + , Zn2 + , Sn2 + , Cd2 + , Hg2 + and Pb2 + ) and anions (F−, Cl−, Br−, I−, CH3COO−, SO32−, SO42−, S2O32−, NO2−, NO3−, PO43− and HPO42−) are tested. The obtained results reveal that the C-dots1 shows selectivity towards Fe3 + and S2O32− whereas C-dots2 shows selectivity towards Zn2 + and PO43− ions. Fe3 + and Zn2 + are involved in major functions of complex chemistry and biology of the human brain and also play vital role in various biological systems such as in cellular metabolism, gene expression and neurotransmission22,23,24,25. Similarly, the anions also play predominant roles in biological, chemical and environmental processes26. Thiosulphate have many important physiological features and are used in medicine and industry applications27,28,29, and the phosphate anions are one of most important constituents of living systems and their derivatives play pivotal roles in biological systems30,31. Thus, there is an essential task to the developing a facile detection method for metal ions and anions in biological media to better understand its physiological roles in chemistry and biological studies. Based on the sensing results we implemented the molecular logic gates behavior by observing the fluorescence response, i.e., change in the fluorescence intensity with varying the chemical inputs such as metal ions and anions. In comprehensive, the most important observation is the construction of different logic functions which mainly depend on the functional group present on the C-dots surface, interaction between the C-dots and metal ions/anions, and the reaction between the metal ions and anions.

Results and Discussion

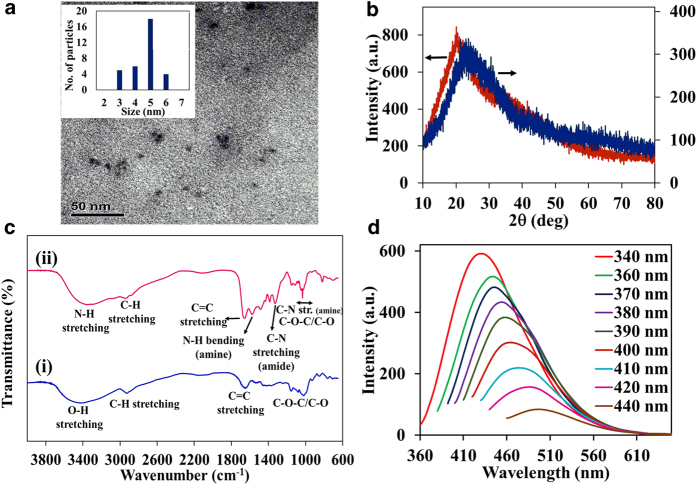

The C-dots1 and C-dots2 were prepared through carbonization of rice as a carbon precursor by a one-step microwave-assisted method. The estimated quantum yield of C-dots1 and C-dots2 are 3 and 11% respectively obtained by using quinine sulphate as the reference. The size and morphology of C-dots were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The TEM image clearly indicates that the formed C-dots were spherical in shape with average diameters of 5 nm and well dispersed to each other (Fig. 1a). The XRD pattern (Fig. 1b) showed a broad diffraction peak appeared at ~20 ° (d = 0.45 nm) and ~24 ° (d = 0.38 nm) for C-dots1 and C-dots2 respectively. The calculated interlayer distance is lower than that of graphite (d = 0.34 nm). The diffraction peak of C-dots1 shifted to a lower degree may be attributed to the reduction of lattice parameters of a unit cell of the C-dots. Further, the FTIR spectrum was recorded to determine the surface functional groups of C-dots (Fig. 1c). Both C-dots exhibit a broad peak with the maxima at ~3400 cm−1 corresponding to the O-H and N-H stretching vibration of carboxylic acid and amine groups respectively. In addition, both C-dots display C-H vibration at ~2930 cm−1, C = C vibration at ~1650 cm−1 and C-O-C vibration at ~1100 cm−1. In C-dots2, three strong absorption peaks observed at 1575, 1385 and 1111 cm−1 indicate the presence of N-H bending vibration (amine), amide C-N and amine C-N stretching bands, thereby revealing that ethylenediamine (EDA) in reaction with carboxylic groups on the surface results in the formation of amide group32. FTIR results confirm that the C-dots have various surface functional groups such as hydroxyl, carbonyl, epoxy, carboxylic and amine groups. The elemental analysis reveals that the C-dots1 is composed of C 40.25, H 6.50, N 1.66 and O 51.54%, whereas the C-dots2 is composed of C 38.40, H 6.80, N 11.34 and O 41.81%. A decrease in an oxygen content of C-dots2 further confirms the reaction occurs between -COOH and EDA on the surface of C-dots2.

Figure 1.

(a) TEM image of C-dots2, inset shows size distributions; (b) XRD patterns of the C-dots1 (red line) and C-dots2 (blue line); and (c) FTIR spectra of C-dots1 (i) and C-dots2 (ii); (d) Fluorescence spectra of C-dots2 with different excitation wavelengths.

The absorption spectrum of C-dots1 shows strong absorption band peaking at ~280 nm with a tail extended to 500 nm. Besides, the C-dots2 exhibits strong absorbance in the region of above 300 nm compared with that of C-dots1. In both C-dots, the observed band at ~280 nm is attributed to the π–π* transition corresponding to carbon core C = C units whereas the shoulder at ~350 nm is due to the n–π* transition corresponding to the carbonyl/amine functional groups on the surface14,32. Fluorescence spectra of C-dots were recorded at different excitation wavelength and the resultant fluorescence spectra obviously represent that C-dots have multi-emission nature and depending on the excitation wavelength (Fig. 1d). Moreover, the fluorescence maximum and intensity was found to be dependent on the excitation wavelengths. Upon C-dots excitation varying from 320 to 450 nm, the emitted fluorescence maximum was red shifted from ~420 to 520 nm and higher fluorescence intensity was observed at 340 nm excitation.

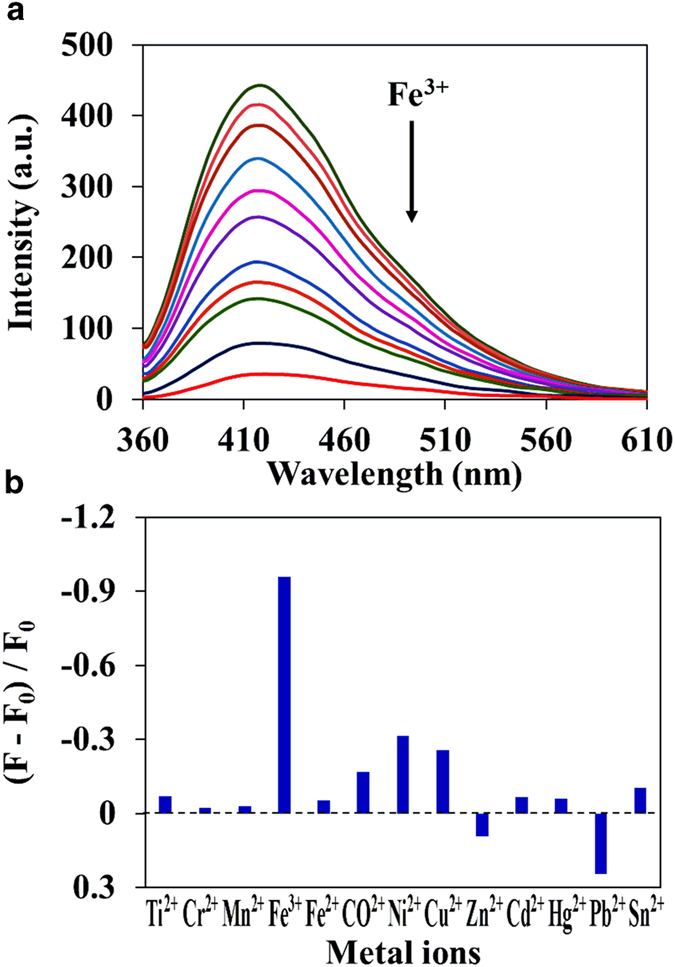

Next, we determined the influence of metal ions on the C-dots fluorescence intensity by using fluorescence titration method. The fluorescence titration of C-dots with different concentration of metal ions in pH 7.2 HEPES-buffered water was used throughout all the experiments. Despite the same experimental conditions, the two different functionalized C-dots exhibits different sensitivity and selectivity for metal ions. For C-dots1, Fe3+ ions show significant effect on fluorescence quenching among the metal ions studied. The fluorescence intensity was found to decrease with increasing concentration of Fe3+ ions, but peaking at the same position even in the presence of highest concentration of Fe3+ ions (Fig. 2). The observed fluorescence quenching of C-dots1 may be due to non-radiative electron transfer from the excited state of the C-dots to the d-orbital of Fe3+ ion18,33. The fluorescence quenching process was analyzed by using Stern-Volmer (S-V) relation (F0/F = 1 + KSV [Q] = 1 + kq τ0 [Q])34. The S-V plot shows linearity in the concentration range of 0 – 100 μM, yielding KSV of 2.5 × 104 M−1. The quenching rate constant kq was calculated to be 5.15 × 1012 M−1 s−1, which reveals that the high efficiency of quenching process in the excited state. The determined kq value is much higher than the diffusion-controlled quenching limit, suggesting that the Fe3+ ions plausibly coordinate with -COOH groups on the surface of C-dots118,33. When the concentration keeps increasing, the S-V plot begins to deviate from linearity, indicating that the observed quenching process may be due to both dynamic and static process.

Figure 2.

a) Fluorescence spectra of C-dots1 (0.002 mg mL−1) with different concentration of Fe3 + (0 to 2.5 × 10−4 M) in pH 7.2 HEPES-buffered water solution. (b) Fluorescence response of C-dots1 in the presence of different metal ions. λex = 340 nm.

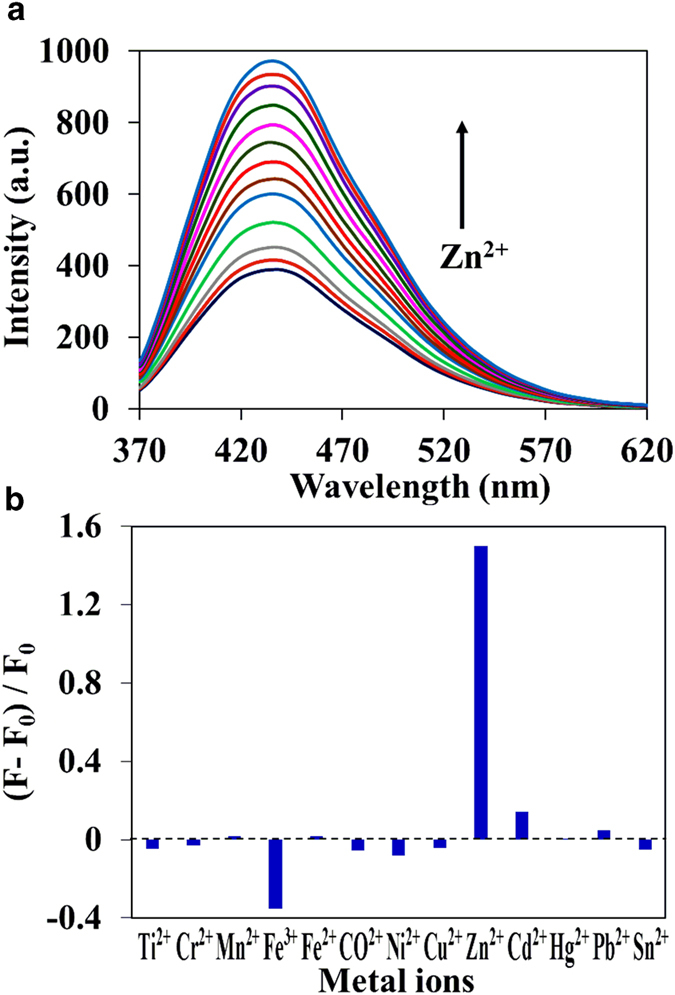

In the case of C-dots2, drastic enhancement of fluorescence intensity was observed in the presence of Zn2+ ions (Fig. 3). The fluorescence intensity increased with increasing the concentration of Zn2 + , but the peak position did not change. The observed fluorescence enhancement is probable due to the higher affinity of Zn2+ with the nitrogen atoms of amine groups on the C-dots surface. Upon addition of other metal ions including Fe2+, Cr2+, Ni2+, CO2+, Cu2+, Hg2+, Pb2+, Ti2+, Mn2+, Cd2+ and Sn2+, the fluorescence intensity and maximum of both C-dots do not altered much even in the presence of highest concentration of metal ions (2.5 × 10−4 M).

Figure 3.

a) Fluorescence spectra of C-dots2 (0.002 mg mL−1) with different concentration of Zn2 + (0 to 2.5 × 10−4 M) in pH 7.2 HEPES-buffered water solution. (b) Fluorescence response of C-dots2 in the presence of different metal ions. λex = 340 nm.

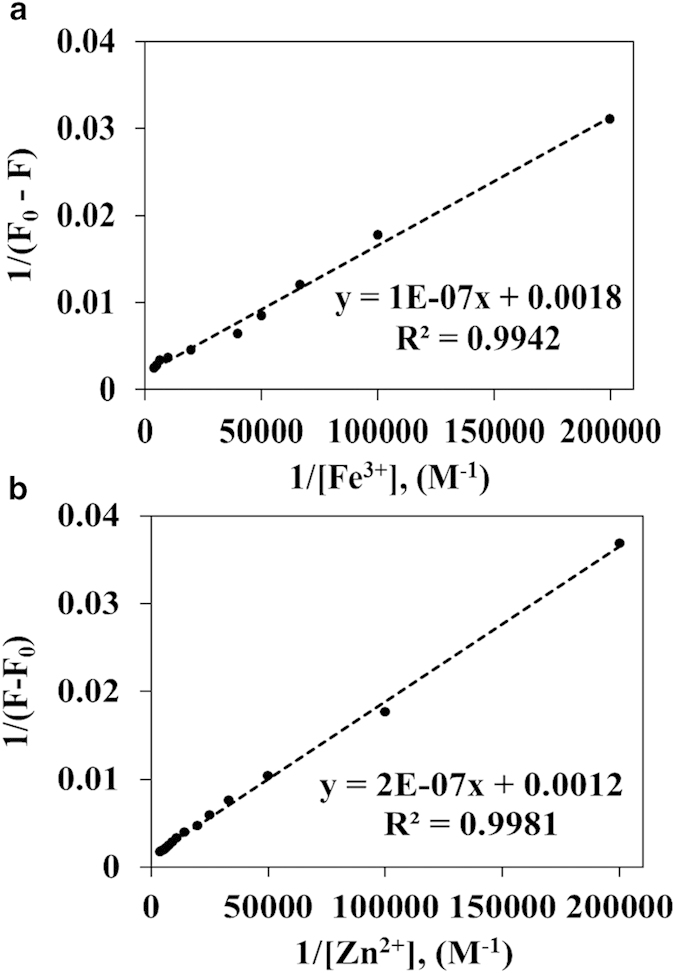

Further, the stoichiometry for interaction of C-dots with metal ions and the association constant was determined by using the Benesi-Hildebrand method based on the changes in the fluorescence intensity35. The Benesi-Hildebrand plot of 1/(F − F0) versus 1/[Mn+] exhibits a straight line for both C-dots, which confirms the 1:1 stoichiometry of C-dots with metal ions (Fig. 4). The association constant (log Ka) was determined by dividing the intercept by the slope of the straight line, yielding value of 4.05 and 3.78 for C-dots1/Fe3+ and C-dots2/Zn2+ systems respectively. The detection limit of the C-dots was determined on the relation 3(σ/slope), where σ is the standard deviation of the response. A good linear correlation was observed over the concentration range of 0 – 50 μM. The measured detection limits are 0.78 × 10−7 and 1.63 × 10−7 M for C-dots1/Fe3 + and C-dots2/Zn2 + systems, respectively. From the obtained results, the C-dots sensors appear to be highly selective and sensitive for the detection of metal ions. In particular, C-dots1 shows more affinity towards Fe3+ detection which is similar to previously reported literatures18,33,36,37,38. Recently, Zhang et al. reported that the quinolone derivative-functionalized carbon dots exhibited good response towards the sensing of Zn2+ ion39. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of using C-dots for label-free detection of Zn2+ with high selectivity.

Figure 4.

Benesi-Hildebrand plot of 1/F−F0 versus 1/[Mn + ] for the (a) C-dots1/Fe3 + and (b) C-dots2/Zn2 + systems.

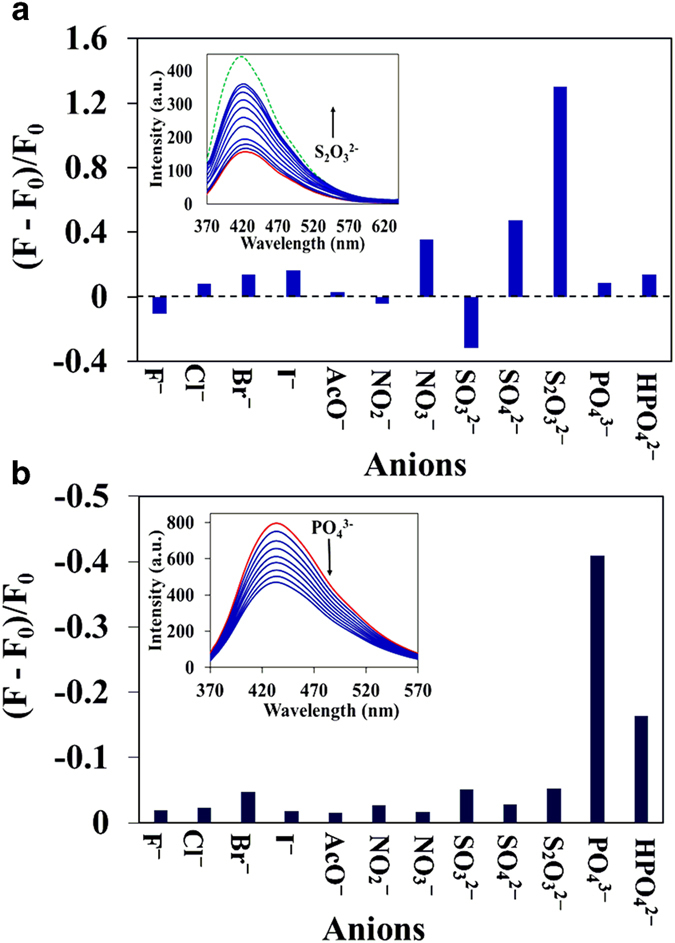

In addition to the sensing of metal ions, we examined the sensing of anions for both C-dots/Mn + systems based on the fluorescence on-off and off-on method. To investigate the selectivity of anion detection, the fluorescence spectra of C-dots/Mn + systems in the presence of biological relevant anions including F−, Cl−, Br−, I−, CH3COO−, SO32−, SO42−, S2O32−, NO2−, NO3−, PO43− and HPO42− were recorded (Fig. 5). Interestingly, upon addition of anions the quenched fluorescence was recovered for C-dots1/Fe3+ system whereas the enhanced fluorescence was quenched for C-dots2/Zn2+. It was found that the quenched fluorescence of C-dots1/Fe3+ gradually recovers with increasing concentration of S2O32− ion (Fig. 5a). Approximately 80% of the fluorescence at 420 nm was recovered by the addition of 1.25 M S2O32−, and this recovery percentage can be increased with further increase of the concentration. The detection limit of the C-dots1/Fe3+ for S2O32− was calculated to be about 8.47 × 10−6 M. Similarly, to study the selectivity and sensitivity of C-dots2/Zn2+ for anion detection, the fluorescence spectra of C-dots2/Zn2+ were recorded in the presence of various anions and the plot of selectivity is shown in Fig. 5b. The results demonstrate that this sensor system displays good selectivity towards PO43− anions. The fluorescence intensity of the ensemble solution was quenched on the addition of PO43−. The detection limit of C-dots2/Zn2+ system for the sensing of PO43− was calculated to be 6.89 × 10−6 M. In contrast, other anions show very minor influence on the fluorescence intensity of the C-dots2/Zn2+ system except for HPO42− which shows moderate response.

Figure 5.

a) Fluorescence response of C-dots1/Fe3 + in the presence of different anions; Inset: Fluorescence spectra of C-dots1/Fe3 + in the absence (red line) and presence (blue lines) of different concentration of S2O32− (0 to 1.25 × 10−3 M); Green dotted line: fluorescence spectrum of C-dots1 alone. (b) Fluorescence response of C-dots2/Zn2 + in the presence of different anions; Inset: Fluorescence spectra of C-dots2/Zn2 + in the absence (red line) and presence (blue lines) of different concentration of PO43− (0 to 1.25 × 10−3 M). λex = 340 nm.

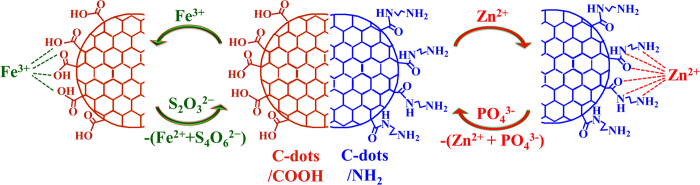

The detection process of metal ions and anions is shown in Fig. 6. The C-dots1 contains ample amount of carboxylate groups on the surface and Fe3+ ions shows a certain affinity to the oxygen atoms which resulted in the association between the Fe3+ ions and carboxylate groups. On the other hand, owing to strong interaction between Fe3 + and S2O32− ions, the associated Fe3 + ions react with S2O32− to forms free C-dots1. Due to above two facts, the C-dots1 system exhibited off-on fluorescence behavior. Similarly, Zn2 + displays an affinity with nitrogen and oxygen atoms; as a consequence the C-dots2 fluorescence was enhanced due to association between Zn2 + and amine groups present on the surface. Then, the associated C-dots2/Zn2 + moieties could be disassociated by the addition of PO43− due to affinity between Zn2 + and oxygen atoms of PO43−, which leads to turn-off fluorescence of C-dots2. These results proved that this off-on and on-off fluorescence process depend on the functional groups present on the C-dots surface and affinity nature of metal ion with anions.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation for the sensing process of metal ions and anions with C-dots.

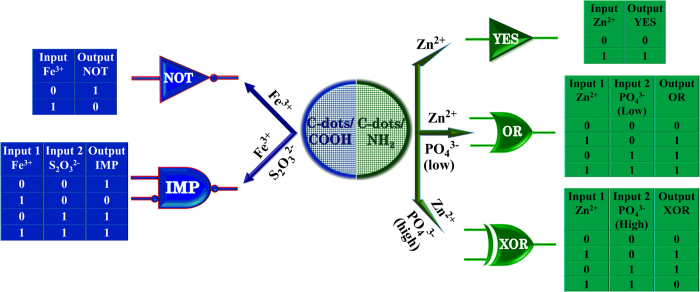

Based on the observations in the sensing studies of metal ions and anions by C-dots, we demonstrate individual logic gates such as YES, NOT, IMP, OR and XOR. The performance of various logic gate functions depend on the association and dissociation of metal ions (Fe3 + or Zn2 + ) and anions (S2O32− or PO43−) with C-dots and their corresponding fluorescence intensity emitted by C-dots. Experiments were performed on C-dots with the four possible input combinations (0,0; 1,0; 0,1; 1,1) for multiple logic gate operations. In logic gates implementation, metal ion (Fe3 + or Zn2 + ) and anion (S2O32− or PO43−) are used as input 1 and input 2 respectively, and the fluorescence signal as output. The absence and association of these ionic inputs with C-dots defines as 0 and 1 states respectively. The output defined as 1 and 0 corresponds to strong and weak fluorescence response9. The simplest logic gates NOT and YES were achieved by giving metal ions (Fe3 + or Zn2 + ) as input 1 to the C-dots, in the absence of input 2 (anions), and producing a low or high fluorescence output signal. The fluorescence of C-dots1 quenched in the presence of Fe3 + indicates that the output is 0 (low), on the contrary, fluorescence of C-dots2 enhanced in the presence of Zn2 + indicates that the output is 1 (high). These results correlate well with the function of NOT and YES logic gates respectively9.

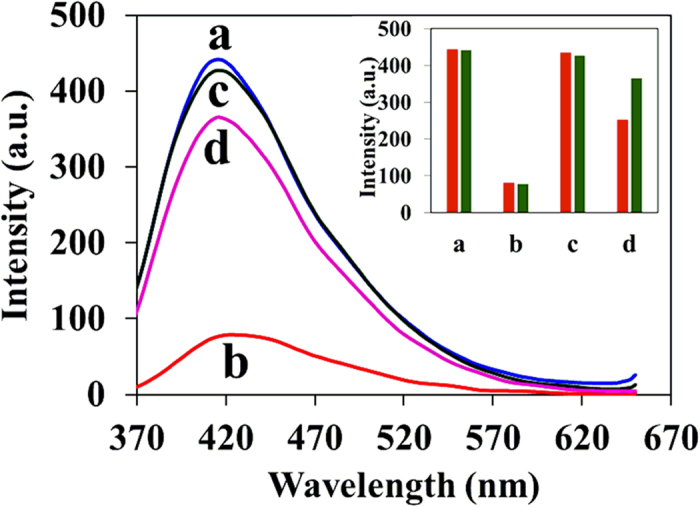

Further, we demonstrated the construction of IMP logic gate by using Fe3 + (fixed concentration) and S2O32− (varying concentration) as input 1 and 2 to the C-dots1. Before obtaining the IMP logic gate with the presence of input 1 and 2, it is essential to examine the influence of individual input on C-dots and their corresponding output fluorescence intensity signal while the absence of other input. The fluorescence intensity of the C-dots1 was quenched in the presence of individual Fe3 + input and not much varied by the addition of low or high concentration of individual S2O32− input (Fig. 7). Interestingly, in the presence of both inputs, the decrease in the fluorescence intensity upon addition of Fe3 + is recovered by the addition of S2O32− (low or high concentration). These observations clearly confirm the IMP logic gate behavior40,41 according to truth table (Fig. 8).

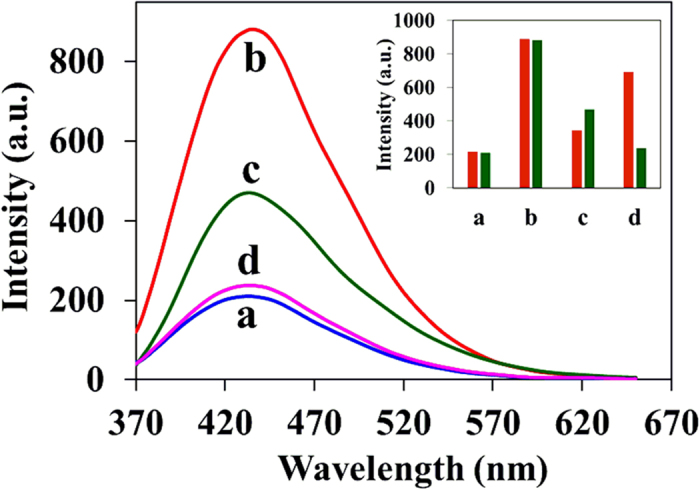

Figure 7.

Fluorescence response of C-dots1 in the absence and presence of Fe3 + (2.5 × 10−4 M) and S2O32− (3.0 × 10−3 M); a: C-dots1, b: C-dots1/Fe3 + , c: C-dots1/S2O32−, d: C-dots1/Fe3 + /S2O32−. Inset: Bar diagram showing the fluorescence intensity changes for different combination of inputs, Red color: in the presence of low concentration of S2O32− (2 × 10−4 M), Green color: in the presence of high concentration of S2O32− (3.0 × 10−3 M).

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of logic gates obtained for C-dots1/Fe3 + /S2O32− and C-dots2/Zn2 + /PO43− systems.

Similarly, we demonstrated the construction of the OR and XOR logic gates with C-dots2 in the presence of Zn2 + (fixed concentration) as input 1 along with PO43− (low and high concentration) as input 2 (Fig. 9). It was observed that, the fluorescence intensity of C-dots2 was enhanced in the presence of individual inputs Zn2 + or different (low or high) concentration of PO43−. Surprisingly, in the presence of both inputs (Zn2 + and low concentration of PO43−), the enhanced fluorescence intensity of C-dots2 due to Zn2 + input was slightly decreased due to sequential addition of low concentration of PO43−. However, the quenched fluorescence intensity was still higher compared to that of C-dots2 without any individual inputs, i.e., the output is 1 (high), these results confirm the operation of OR gate. On the contrary, the fluorescence intensity was quenched drastically upon addition of high concentration of PO43− indicating that the output is 0 (low) in contradiction to the function of OR gate. These results show that the use of low or high concentration of PO43− as input 2 along with Zn2 + as input 1 generated OR or XOR logic gate functions42,43 respectively (Fig. 8), revealing that the different logic operation can be achieved by varying the concentration of inputs. We have repeatedly performed each logic gate operation for at least four times and the efficiency varied between 80–85% depending upon the chemical inputs. Based on all these results, we propose that the role of C-dots will be of great importance in the field of molecular electronic and nanodevices.

Figure 9.

Fluorescence response of C-dots2 in the absence and presence of Zn2 + (2.5 × 10−4 M) and PO43− (3.50 × 10−3 M); a: C-dots2, b: C-dots2/Zn2 + , c: C-dots2/PO43−, d: C-dots2/Zn2 + /PO43−. Inset: Bar diagram showing the fluorescence intensity changes for different combination of inputs, Red color: in the presence of low concentration of PO43− (1.0 × 10−4 M), Green color: in the presence of high concentration of PO43− (3.50 × 10−3 M).

Conclusions

We performed the detection of metal ions and anions done by carboxylate/amine functionalized C-dots sensors in pH 7.2 HEPES-buffered water solution. It was found that the functional groups present on the C-dots surface showed certain association affinity towards specific metal ions. The results revealed that both C-dots exhibit highly selective and sensitive towards the detection of metal ions such as Fe3 + and Zn2 + , and anions like S2O32− and PO43−. We have also demonstrated C-dots based molecular logic gates operation using metal ions and anions as the chemical input. The multiple logic gates such as YES, NOT, IMP, OR and XOR were constructed by the consecutive processes of association of metal ion with C-dots, and dissociation by anion. This carbon-dots sensor can be utilized as various logic gates at the molecular level and it will show better applicability for the next generation of molecular logic gates. Their promising properties of C-dots may open up a new paradigm for establishment of the chemical logic gates via fluorescent chemosensors.

Methods

Materials

Rice was purchased from the local market of Taipei, Taiwan. Ethylenediamine and 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid were purchased from ACROS. Metal chlorides/nitrates and sodium salt of anions were purchased from Aldrich and ACROS. All commercially available organic and inorganic reagents were used without further purification. Milli-Q ultrapure water was used throughout the experiments.

Instrumentations

UV–Visible absorption spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific evolution 220 UV-Visible spectrophotometer. Fluorescence spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer LS45 spectrophotometer. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS5 FT-IR Spectrometer. TEM observations were conducted on a Hitachi H-7100 transmission electron microscope. Wide-angle X-ray powder diffraction patterns were recorded on a PANalytical (X’Pert PRO) diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (wavelength λ = 0.1541 nm). Elemental analysis was conducted on Elementar Vario EL-III (for NCH) and EL cube (for O). All measurements were recorded at ambient temperature.

Synthesis of C-dots

C-dots were synthesized from rice (as carbon source) by using microwave-assisted method. In a typical procedure, certain amount of rice was rinsed (rinsed repeatedly until the rinse water is clear) with Millipore water to remove the dust particles. Then that rice was added into Millipore water; stirred well for 1 h and filtered using Whatmann filter paper. The filtrated solution (rice water) was used as a precursor. The solution (10 mL) was heated in a domestic microwave oven (Panasonic, NN-ST342) at varying the power (220, 550 and 800 W) and time (5, 10 and 15 min). During microwave heating, the solution color was changed from colorless to pale brown color which results in the formation of C-dots. The obtained product was dispersed in Millipore water and then centrifuged (10000 rpm, 15 min) to remove large size particles. The supernatant solution was dialyzed against Millipore water using a dialysis membrane with MWCO of 3.5 – 5.0 kD (Spectra/Por Float-A-Lyzer G2) for two days. Finally the obtained pure C-dots were used for characterization and experimental studies. For the synthesis of amine functionalized C-dots, EDA was added into rice water and stirred well. This solution was used as a precursor and rest of synthesis procedure is same as above mentioned. Here we optimized the synthesis conditions such as heating power and reaction time to obtain the high fluorescence efficiency of C-dots. The synthesis conditions were optimized based on the fluorescence quantum yield and the higher quantum yield was obtained for the condition of 550 W and 15 min.

General procedure for sensing of metal ion and anions

C-dots, metal ions and anions stock solutions were prepared in pH 7.2 HEPES-buffered water. The fluorescence titration measurements were carried out by adding small volumes (up to 5 μl) of the metal ion/anions to the C-dots solution in a quartz cuvette. After an addition of metal ion to the cuvette, the solution was shaken well and kept 1 min before measurement.

Quantum yield calculation

Quinine sulphate (0.1 M H2SO4 as solvent, Φ = 0.54) was chosen as a standard to measure the quantum yield (Φ) of the C-dots. The quantum yield was determined at an excitation wavelength of 360 nm by the equation,

|

where Φ is the quantum yield, I is the fluorescence intensity, A is the absorbance at excitation wavelength and η is the refractive index of the solvent. The subscript st refers to standard with known quantum yield and x refers to the sample. The absorbance of standard and carbon dots solutions were kept below 0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Dhenadhayalan, N. and Lin, K.-C. Chemically Induced Fluorescence Switching of Carbon-Dots and Its Multiple Logic Gate Implementation. Sci. Rep. 5, 10012; doi: 10.1038/srep10012 (2015).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, Republic of China under contract no. NSC 99-2113-M-002-010-MY3.

Footnotes

Author Contributions N. D performed all the experiments and wrote the manuscript. K.-C. L discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Li T., Lohmann F. & Famulok M. Interlocked DNA nanostructures controlled by a reversible logic circuit. Nat. Commun. 5, 4940 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D. et al. Nucleic acid based logical systems. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 5866–5873 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Qu Z.-B., Ma H.-Y., Zhou T. & Shi G. DNA-based sensitization of Tb3+ luminescence regulated by Ag+and cysteine: use as a logic gate and a H2O2 sensor. Chem. Commun. 50, 4677–4679 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carell T. Molecular computing: DNA as a logic operator. Nature 469, 45–46 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D.-L., He H.-Z., Chan D. S.-H. & Leung C.-H. Simple DNA-based logic gates responding to biomolecules and metal ions. Chem. Sci. 4, 3366–3380 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.-M., Zhang L., Liang R.-P. & Qiu J.-D. DNA electronic logic gates based on metal-ion-dependent induction of oligonucleotide structural motifs. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 6961–6965 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentili P. L. Boolean and fuzzy logic gates based on the interaction of flindersine with bovine serum albumin and tryptophan. J. Phys. Chem. A. 112, 11992–11997 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu S., Kinbara K., Taguchi H., Ishii N. & Aida T. Semibiological molecular machine with an implemented AND logic gate for regulation of protein folding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 3764–3769 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva A. P. [Molecular logic gates] Supramolecular chemistry: From molecules to nanomaterials. [ Gale P. A. & Steed J. W. (Ed.) ] (John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Ecik E. T. et al. Modular logic gates: Cascading independent logic gates via metal ion signals. Dalton Trans. 43, 67–70 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou S. et al. Fluorescent molecular logic gates using microfluidic devices. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 872–876 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnlaugsson T., Mac Donail D. A. & Parker D. Luminescent molecular logic gates: The two-input inhibit (INH) function. Chem. Commun. 93–94 (2000). DOI: 10.1039/A908951I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Zhao A., Ren J. & Qu X. Lighting up left-handed Z-DNA: Photoluminescent carbon dots induce DNA B to Z transition and perform DNA logic operations. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 7987–7996 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. & Hu A. Carbon quantum dots: Synthesis, properties and applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2, 6921–6939 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Baker S. N. & Baker G. A. Luminescent carbon nanodots: Emergent nanolights. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 6726–6744 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu S., Behera B., Maiti T. K. & Mohapatra S. Simple one-step synthesis of highly luminescent carbon dots from orange juice: Application as excellent bio-imaging agents. Chem. Commun. 48, 8835–8837 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. Water-soluble fluorescent carbon quantum dots and photocatalyst design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 4430–4434 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S. et al. Highly photoluminescent carbon dots for multicolor patterning, sensors, and bioimaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 3953–3957 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pu F., Ren J. & Qu X. Plug and play logic gates based on fluorescence switching regulated by self-assembly of nucleotide and lanthanide ions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 9557–9562 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J. et al. Multiple logic functions based on small molecular fluorene derivatives and their application in cell imaging. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 9368–9376 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava P. et al. Selective naked-eye detection of Hg2+through an efficient turn-on photoinduced electron transfer fluorescent probe and its real applications. Anal. Chem. 86, 8693–8699 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. et al. A quantum dot-based off–on fluorescent probe for biological detection of zinc ions. Analyst 138, 2181–2191 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Que E. L., Domaille D. W. & Chang C. J. Metals in neurobiology: Probing their chemistry and biology with molecular imaging. Chem. Rev. 108, 1517–1549 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter K. P., Young A. M. & Palmer A. E. Fluorescent sensors for measuring metal ions in living systems. Chem. Rev. 114, 4564–4601 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P. & Guo Z. Fluorescent detection of zinc in biological systems: Recent development on the design of chemosensors and biosensors. Coord. Chem. Rev. 248, 205–229 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Beer P. D. & Hayes E. J. Transition metal and organometallic anion complexation agents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 240, 167–189 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Fisher C. R., Childress J. J., Oremland R. S. & Bidigare R. R. The importance of methane and thiosulfate in the metabolism of the bacterial symbionts of two deep-sea mussels. Mar. Biol. 96, 59–71 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Dahwak S. W. Thiosulfate. J. Chem. Ed. 70, 12–14 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Ravot G. et al. Thiosulfate reduction, an important physiological feature shared by members of the order thermotogales. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 2053–2055 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han M. S. & Kim D. H. Naked-eye detection of phosphate ions in water at physiological pH: A remarkably selective and easy-to-assemble colorimetric phosphate-sensing probe. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 3809–3811 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. X. et al. Highly selective detection of phosphate in very complicated matrixes with an off–on fluorescent probe of europium-adjusted carbon dots. Chem. Commun. 47, 2604–2606 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q. et al. Capillary electrophoretic study of amine/carboxylic acid-functionalized carbon Nanodots. J. Chromatogr. A 1304, 234–240 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y. et al. Investigation into the fluorescence quenching behaviors and applications of carbon dots. Nanoscale 6, 4676–4682 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhenadhayalan N. & Selvaraju C. Role of photoionization on the dynamics and mechanism of photoinduced electron transfer reaction of coumarin 307 in micelles. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 4908–4920 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benesi H. A. & Hildebrand J. H. A spectrophotometric investigation of the interaction of iodine with aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 71, 2703–2707 (1949). [Google Scholar]

- Qu S., Chen H., Zheng X., Cao J. & Liu X. Ratiometric fluorescent nanosensor based on water soluble carbon nanodots with multiple sensing capacities. Nanoscale. 5, 5514–5518 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.-L. et al. Graphitic carbon quantum dots as a fluorescent sensing platform for highly efficient detection of Fe3+ions. RSC Adv. 3, 3733–3738 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Qu K., Wang J., Ren J. & Qu X. Carbon dots prepared by hydrothermal treatment of dopamine as an effective fluorescent sensing platform for the label-free detection of iron(III) ions and dopamine. Chem. Eur. J. 19, 7243–7249 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. et al. Quinoline derivative-functionalized carbon dots as a fluorescent nanosensor for sensing and intracellular imaging of Zn2+. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2, 5020–5027 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J.-H., Kong D.-M. & Shen H.-X. Design of a fluorescent DNA IMPLICATION logic gate and detection of Ag + and cysteine with triphenylmethane dye/G-quadruplex complexes. Biosens. Bioelectron. 26, 327–332 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Zhang L., Li T., Dong S. & Wang E. Enzyme-free unlabeled DNA logic circuits based on toehold-mediated strand displacement and split G-quadruplex enhanced fluorescence. Adv. Mater. 25, 2440–2444 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D.-L. et al. Crystal violet as a fluorescent switch-on probe for i-motif: Label-free DNA-based logic gate. Analyst 136, 2692–2696 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K. S., Seo M. W., Jung C., Lee J. Y. & Park H. G. Simple and universal platform for logic gate operations based on molecular beacon probes. Small 8, 2203–2212 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]