Abstract

In this study we evaluated the effect chronic helminth infection has on allergic disease in mice previously sensitized to ovalbumin (OVA). 10 weeks of infection with Litomosoides sigmodontis reduced immunological markers of type I hypersensitivity, including OVA-specific IgE, basophil activation, and mast cell degranulation. Despite these reductions, there was no protection against immediate clinical hypersensitivity following intradermal OVA challenge. However, late phase ear swelling, due to type III hypersensitivity, was significantly reduced in chronically infected animals. Levels of total IgG2a, OVA-specific IgG2a, and OVA-specific IgG1 were reduced in the setting of infection. These reductions were likely due to increased antibody catabolism as ELISPOT assays demonstrated that infected animals do not have suppressed antibody production. Ear histology 24 hours after challenge showed infected animals have reduced cellular infiltration in the ear, with significant decreases in numbers of neutrophils and macrophages. Consistent with this, infected animals had less neutrophil-specific chemokines CXCL-1 and CXCL-2 in the ear following challenge. Additionally, in vitro stimulation with immune-complexes resulted in significantly less CXCL-1 and CXCL-2 production by eosinophils from chronically infected mice. Expression of FcγRI was also significantly reduced on eosinophils from infected animals. These data indicate that chronic filarial infection suppresses eosinophilic responses to antibody-mediated activation and has the potential to be used as a therapeutic for pre-existing hypersensitivity diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Despite numerous epidemiologic and animal studies suggesting helminth infections are protective against allergy, the two prospective human clinical trials that have tested the efficacy of infection as a therapeutic have failed to show clinical benefit (1, 2). Lack of protection may be due to a variety of factors, including the possibility that helminth infections are better at preventing allergy than treating it. Interestingly, while over 30 animal studies have demonstrated that helminth infection established prior to sensitization protects against the development of allergy, very few have investigated the use of helminths as therapeutics for pre-existing allergic disease (reviewed in (3)).

In this study, we sought to determine whether Litomosoides sigmodontis, a tissue-invasive filarial nematode that establishes chronic infection in immunocompetent BALB/c mice (4), protects against local hypersensitivity responses after sensitization has taken place. Similar to other helminths, L. sigmodontis induces systemic immunomodulation (5-7), and a previous study demonstrated that L. sigmodontis can inhibit the development of allergic disease when infection is established prior to allergic sensitization (8). As we recently demonstrated that chronic L. sigmodontis infection suppresses the IgE-mediated activation of basophils (9), we hypothesized that infection may also protect against allergic disease in previously sensitized mice.

Our results demonstrate that while 10 weeks of L. sigmodontis infection suppresses numerous immunologic markers of type I hypersensitivity, including allergen-specific IgE as well as basophil and mast cell degranulation in response to allergen exposure, it does not confer clinical benefit as measured by increases in local vascular permeability. Interestingly, though, we did find that infection protects the host from ear swelling due to type III (immune complex-mediated) hypersensitivity. This protection is associated with reduced neutrophil-specific chemokine production, fewer neutrophils trafficking to the site of immune complex deposition, reduced chemokine production by eosinophils after immune complex stimulation, and decreased Fc gamma receptor I (FcγRI) expression on eosinophils.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

4-6 week old female BALB/c mice (National Cancer Institute Mouse Repository, Frederick, MD), IgE-deficient mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), C57BL/6 mice (The Jackson Laboratory), mast cell deficient Wsh mice (The Jackson Laboratory), eosinophil deficient ΔdblGATA mice (The Jackson Laboratory), and antibody deficient JH−/− mice (Taconic, Hudson, NY) were housed at the Uniformed Services University Center for Laboratory Animal Medicine. All experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Uniformed Services University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Ovalbumin sensitization

Mice were sensitized as previously described (10). In brief, mice received i.p. injections of 50 μg of ovalbumin (Sigma-Aldrich) adsorbed to 2 mg aluminum hydroxide (Pierce) in PBS on days 0, 7, and 14. Mock sensitization groups received i.p. injections of 2 mg aluminum hydroxide in PBS. Mice were given a 2-6 week rest period before infection or ovalbumin (OVA) challenge.

Litomosoides sigmodontis infection

Infectious L3-stage larvae were isolated from the pleural cavity of infected jirds (Meriones unguiculatus, obtained from TRS Laboratory, Athens, GA) as previously described (11). Mice were infected by subcutaneous injection of 40 L3 larvae in RPMI-1640. Mock treatment groups were given a subcutaneous injection of RPMI-1640 (Mediatech, Inc.). Worm counts, OVA challenge and immunological assays were performed 10 weeks post-infection.

Intradermal OVA challenge

The local anaphylaxis assay was performed as previously described (10). Mice were given an intradermal injection of 20 μg OVA in 10 μl of PBS in one ear and 10 μl of vehicle alone (PBS) in the other ear. 3 minutes after challenge, 200 μl of 0.5% Evans Blue dye (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected into the tail vein. 10 minutes later, animals were euthanized with CO2 and ears were removed and placed in formamide (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at 63°C. Extracted dye was measured at an absorbance of 620 nm. The O.D. of the vehicle challenged ear was then subtracted from the O.D. of the OVA challenge ear for each animal.

For the ear thickness assay, a micrometer was used to measure baseline ear thickness prior to intradermal injection of 20 μg OVA or vehicle. Ear thickness was then measured at 1, 2, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours post challenge.

Basophil, CD4 cell, and platelet depletions

For basophil depletion, mice received an i.p. injection of 50 μg of anti-CD200R3 clone Ba103 (Hycult Biotech) or rat IgG2b isotype control clone A95-1(BD Biosciences) 24 hours before challenge. For CD4+ T cell depletion, mice received an i.p. injection of 500 μg of anti-CD4 clone GK1.5 (BioXcell) or rat IgG2b isotype control 24 hours before challenge. Depletion of basophils and CD4+ T cells was confirmed via flow cytometry 4 days after challenge. For platelet depletion, mice received an i.p. injection of 4 μg of anti-CD41 clone MWReg30 (provided by John Semple M.D., University of Toronto) or rat IgG1 isotype control clone R3-34 (BD Biosciences) 24 hours before challenge. Platelet depletion was confirmed by complete blood count (CBC) 24 hours after administration of the antibody.

Histology

10 weeks post-infection, animals were challenged with PBS in one ear and 20 μg OVA in the other. 3 and 24 hours after challenge, animals were euthanized and ears were fixed in 10% formalin. H&E and toluidine blue staining was performed by Histoserv (Rockville, MD). Slides were digitized with a 20X objective on a 2.0-RS NanoZoomer (Hamamatsu) using NDP.scan software version 2. Digitized slides were analyzed with NDP.view software version 1. Mast cell degranulation was assessed 24 hours after challenge via toluidine blue stain. Based on the assumption that left and right ears contain a similar number of mast cells for each mouse, cells staining positive for toluidine blue for an entire ear section were enumerated. The number of toluidine-positive cells for the OVA challenge ear was then subtracted from the PBS challenge ear for each mouse to quantify the difference in mast cell degranulation as a result of OVA challenge. To assess ear pathology, a blinded pathologist (BKM) scored H&E sections for each ear using four parameters (hemorrhage, edema, necrosis and cellularity) on the basis of severity (0-absent, 1-mild, 2-moderate, or 3-severe) and focality (0-absent, 1-focal, 2-intermediate, and 3-diffuse) for a total maximum inflammation score of 24.

Immunohistochemistry

10 weeks post-infection, animals were challenged with PBS in one ear and 20 μg OVA in the other. 3 hours after challenge, animals were euthanized and ears were frozen with liquid nitrogen. Immunohistochemistry was performed by Histoserv (Rockville, MD). Ears were stained with anti-IgG FITC (Sigma) or DAPI, anti-C3 FITC (Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Inc.), and anti-IgG Texas Red (Life Technologies). Confocal images of the entire ear were obtained with a 10X objective using a Zeiss 710 microscope and Zen software. Prior to analysis, TIFF files were exported to Adobe Photoshop and non-specific staining by anti-C3 FITC along the outline of the ear was masked to ensure proper immune complex identification (Supplement 1A). Analysis of immune complexes was performed using the Puncta Analyzer plugin v2.0 (https://github.com/physion/puncta-analyzer) in ImageJ (imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

ELISAs and ELISpot assays

ELISAs were performed on plasma samples from 10-week infected mice. Total IgE (eBioscience), total IgG (eBioscience), total IgG2a (Kamiya Biomedical Company), OVA-specific IgE (MD Bioproducts), OVA-specific IgG1 (Caymen Chemical), and OVA-specific IgG2a (Alpha Diagnostic) ELISAs were performed according to manufacturer instructions. L. sigmodontis-specific IgE ELISAs were performed by coating flat-bottom Immulon 4 plates (Thomas Scientific) with 20 μg/ml L. sigmodontis antigen overnight at 4°C. Plates were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS for 1 hour. Prior to adding samples to the plate, IgG was adsorbed by incubating serum with GammaBind plus Sepharose (GE Healthcare) overnight at 4°C, and diluted 1:8. Plates were then incubated with biotinylated rat anti-mouse IgE clone R35-118 (BD), followed by 1:1000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (BD). Nitrophenyl phosphate disodium (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as substrate. Absorbance was detected with a Victor3 V microplate reader (PerkinElmer).

For ELISpot assays, single cell suspensions of splenocytes were prepared for each animal at 10 weeks post-infection. Spleens were removed, homogenized through a 0.7 μm cell strainer (BD), and RBCs were lysed with ACK lysing buffer (Quality Biological, Inc.). Cells were frozen in RPMI-1640 containing 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 25 mM Hepes buffer, 30% fetal calf serum and 10% DMSO. Total and OVA-specific IgG2a ELISpots (U-CyTech Biosciences) were performed according to manufacturer instructions. Spots were counted manually with a dissecting microscope.

CBCs

10 weeks post-infection, whole blood was collected into EDTA tubes (BD) and complete blood counts (CBCs) were obtained by BioReliance (Rockville, MD)

Obtaining cells from ear tissue

Tissue processing methodology was adapted from Shannon et al. 2013 (12). Both ears were challenged by intradermal injection of 20 μg OVA. 24 hours later, mice were euthanized and a terminal bleed was performed. Then, animals were perfused with 5 ml PBS by intracardiac injection, after which ears were removed and rinsed with 70% ethanol. The dorsal and ventral dermal layers of both ears were then separated and placed in a 35 × 10 mm non-tissue culture treated petri dish (BD) containing 3 ml digestion buffer (RPMI-1640, 25 mM HEPES [Mediatech, Inc.], 1.5 g/L NaHCO3, 100 U/ml DNase I [Roche], and 170 μg/ml Liberase TM [Roche]). Ear tissue was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes and homogenized through a 0.7 um cell strainer to create a single cell suspension. 4 ml of PBS was used to rinse the strainer and additional 3 ml of PBS was added to bring the final sample volume to 10 ml. Cell counts were obtained with a Countess automated cell counter (Life Technologies) using trypan blue exclusion.

Basophil activation assay

10 weeks post-infection, whole blood was collected into heparinized tubes (BD). Samples were centrifuged at 600 × g for 10 minutes, plasma was removed, and remaining cells were washed with RPMI-1640. Washed cells from two animals were pooled for each sample. Samples were stimulated with RPMI-1640 and 40, 10, 2.5 and 0.625 μg/ml ovalbumin for 1 hour at 37°C and 5% CO2. GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) was added and cells were incubated for an additional 2 hours at 37°C. Cells were washed twice with PBS, lysed, and fixed with a whole blood lysing kit (Beckman Coulter). Basophil activation was assessed by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry

To measure basophil activation, fixed cells were blocked with 1% PBS/BSA for 1 hour at 4°C and then incubated with Perm/Wash buffer (BD Biosciences) for 15 minutes at 4°C. Cells were stained with anti-IgE FITC clone R35-72 (BD Biosciences), anti-CD4 PerCP clone RM4-5 (BD Biosciences), anti-B220 PerCP clone RA3-6B2 (BD Biosciences), and anti-IL-4 APC clone 11B11 (BD Biosciences). Basophils were gated as CD4−B220−IgE+, and activated basophils were gated as IL-4+. 1 × 105 events were analyzed per sample.

To determine cell types recruited to the ear following OVA challenge, single cell suspensions of ear tissue were centrifuged at 290 × g for 5 minutes and resuspended in 500 μl of 1% PBS/BSA for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were stained with anti-Ly6G APC-efluor780 clone RB6-8C5 (eBioscience), anti-F4/80 pacific blue clone BM8 (eBioscience), anti-CD19 PE-Cy5 clone eBio1D3 (eBioscience), anti-CD11c BV421 clone N418 (Biolegend), anti-SiglecF PE-CF594 clone E50-2440 (BD Bioscience), and anti-CD45 APC-Cy7 clone 30-F11 (Biolegend), and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Eosinophils were gated as CD11c−CD45+SiglecF+, dendritic cells were gated as CD11c+, B cells were gated as CD19+, macrophages were gated as F4/80+, and neutrophils were gated as F4/80−Ly6G+. 1.5 × 104 events were analyzed for Mock treated animals, 3 × 104 events for Infected animals, 4 × 104 events for Sensitized animals, and 4 × 104 events for Sensitized + Infected animals.

To measure FcγR expression, aliquots of previously prepared frozen splenocytes were thawed and resuspended in 500 μl of 1% PBS/BSA for 30 min at 4°C. Samples were stained with the aforementioned antibodies used to determine cell types recruited to the ear. Additionally, samples were also stained with anti-CD64 PE clone X54-5/7.1 (Biolegend), anti-CD32 (Biorbyt) conjugated to FITC (EasyLink FITC conjugation kit, Abcam), anti-CD16 clone EPR4333 (Abcam) conjugated to APC (Lightning-Link APC antibody labeling kit, Novus Biologicals), and anti-FcεRI PE clone MAR-1 (eBioscience). Cell types were gated as previously described. Each cell type was then assessed for FcγRI (CD64), FcγRII (CD32), FcγRIII (CD16), and FcεRI positivity. 1 × 106 events were analyzed per sample.

For all flow cytometric experiments, antibodies were individually titrated using splenocytes from naïve BALB/c mice and OneComp eBeads (eBioscience) were used to calculate compensation for each flow cytometry run. Gates were established using the fluorescence-minus-one technique. Flow cytometric data was collected with a BD LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software version 7 (TreeStar).

Chemokine production

10 weeks post-infection, both ears were challenged with 20 μg OVA. 6 hours later, mice were euthanized and ears were removed and cut into pieces approximately 1.5 cm in size. Ears were pooled for each mouse and added to Lysing Matrix D FastPrep tubes. One Complete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Roche) was dissolved in 10 ml PBS, and 500 μl was added to each tube. Samples were homogenized with a FastPrep-24 instrument (MP Biomedicals) set at speed 5 for 20 seconds. Homogenization was repeated 3 times with a 30-second break between runs. Tubes were then centrifuged at 16,100 × g for 10 minutes, and supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C. Samples were tested for the presence of chemokines with a Proteome Profiler Mouse Chemokine Array Kit (R&D Systems, Inc.) according to manufacturer instructions. Membranes were developed for 10 minutes, and digitized for analysis on ImageJ. Densitometry was performed using particle analysis, with measurements for each sample spot averaged and then normalized to membrane reference spots.

In vitro immune complex stimulation

Peritoneal macrophages were isolated by performing a peritoneal lavage with 10 ml HBSS. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 20 mM Hepes buffer. 2.5 × 105 peritoneal cells in 500 μl RPMI were aliquoted to 48 well plates. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours to allow macrophages to adhere. Non-adherent cells were removed by washing 3X with 1 ml PBS. 500 μl of fresh RPMI media was added to each well.

A single cell suspension of splenocytes was prepared by homogenizing spleens through a 0.7 μm cell strainer and removing contaminating RBCs by hypotonic lysis. Splenocytes were then used to generate an eosinophil-enriched cell suspension via negative selection. Splenocytes were incubated with CD45R (B220) and CD90 (Thy1.2) magnetic beads (MACS, Miltenyi Biotec) and applied to LD columns as per manufacturer instructions. 2 × 105 recovered cells in 500 μl RPMI were aliquoted to 48 well plates. A cytospin and DiffQuick stain was performed to assess the composition of recovered cells. Preparations typically resulted in 33% eosinophils, 57% PMNs, and 10% monocytes.

Rabbit anti-ovalbumin antibody (Polysciences, Inc.) was resuspended in ultra-pure H2O and passed through a Mustang E endotoxin removal filter (Pall Corporation). OVA was resuspended in RMPI-1640 and also passed through a Mustang E filter. Immune complexes were generated by incubating 1 μg OVA with 100 μg rabbit anti-ovalbumin antibody, with the total volume brought to 25 μl with RMPI-1640. OVA and anti-ovalbumin antibody were incubated 37°C for 30 minutes, after which 25 μl of immune complexes were added per well of 2 × 105 cells. As a control, additional cells were stimulated with 25 μl of 1 μg of OVA in RMPI-1640. Cells were stimulated with OVA or immune complexes at 37°C for 6 hours, after which plates were centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 minutes. Supernatants were collected and assayed with mouse KC and MIP-2 ELISAs (Ray Biotech) as per manufacturer instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software version 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected groups were analyzed using the Mann Whitney test. p values < 0.05 was considered significant. Unless otherwise noted, data is representative of two individual experiments with 4-5 animals per group.

RESULTS

Chronic Litomosoides sigmodontis infection does not protect against cutaneous type I hypersensitivity

To determine whether chronic helminth infection protects against type I, IgE-mediated hypersensitivity, BALB/c mice were sensitized to OVA for 3 weeks, given a rest period, infected with the rodent filarial parasite Litomosoides sigmodontis for 10 weeks, and then assessed for local anaphylaxis after intradermal injection of OVA (Fig. 1A). L. sigmodontis is a chronic tissue-invasive nematode in which adult worms reside in the pleural cavity and microfilariae circulate in the blood. In all experiments, sensitization did not affect worm burdens, which were assessed at the study endpoint (data not shown).

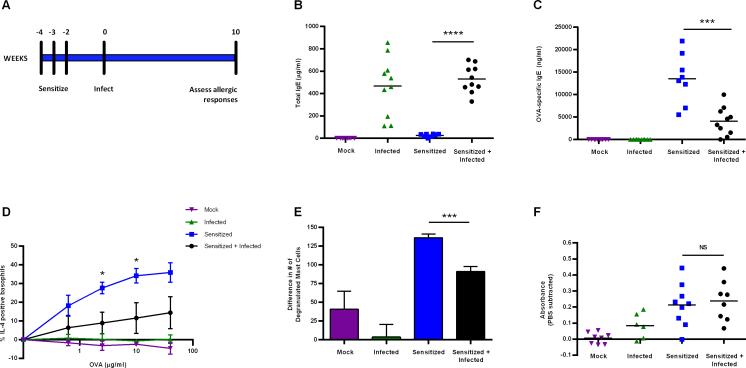

Figure 1.

Chronic L. sigmodontis infection did not protect against clinical type I hypersensitivity. (A) Experimental design for the use of L. sigmodontis as a therapeutic agent for pre-existing allergic disease. Levels of circulating total IgE (B) and OVA-specific IgE (C) were assessed by ELISA at 10 weeks post-infection. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of basophil activation in response to increasing concentrations of OVA stimulation. Basophils were gated as CD4−B220−IgE +, and activation was determined by intracellular IL-4 staining using fluorescence minus one controls. Values plotted represent % IL-4+ basophils after OVA stimulation minus % IL-4+ basophils after culture in media alone. Flow data are representative of two independent experiments with two animals pooled per sample and media levels subtracted. Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected groups were compared at each concentration by the Mann Whitney test. (E) Differences in mast cell degranulation between PBS and OVA challenged ears. Non-degranulated mast cells were enumerated by toluidine blue stain of ear tissue 24 hours after challenge. The total number of toluidine-positive staining cells for the OVA challenge ear was subtracted from the PBS challenge ear to quantify differences in mast cell degranulation. (F) Local anaphylaxis assay (LAA) quantification of cutaneous type I hypersensitivity reactions in response to OVA challenge, with PBS values subtracted. Unless otherwise noted, data are representative of two independent experiments with 4-5 BALB/c mice per group. Error bars represent ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

OVA sensitized animals had elevated total and OVA-specific IgE levels compared to Mock animals (Fig. 1B, C), confirming that OVA sensitization successfully elicited a type 2 immune response. As expected, all infected animals had high levels of total IgE (Fig 1B), and levels of L. sigmodontis-specific IgE levels were the same for Infected and Sensitized + Infected animals (data not shown). Despite having higher levels of total IgE than Sensitized mice, Sensitized + Infected animals had significantly lower levels of OVA-specific IgE compared to Sensitized animals (Fig. 1C).

Basophils and mast cells are two major allergy effector cells that release histamine and other pro-inflammatory mediators in response to IgE cross-linking. To determine if basophils were suppressed in response to allergen, whole blood was stimulated with increasing concentrations of OVA and basophil activation was assessed by measurement of IL-4 production by intracellular flow cytometry. Basophils, identified as CD4−B220−IgE+ cells, had reduced IL-4 production in Sensitized + Infected animals compared to Sensitized animals (Fig. 1D).

To evaluate whether mast cell function was reduced in the setting of chronic L. sigmodontis infection, mast cell degranulation was measured by enumerating total and degranulated mast cells in ear tissue 24 hours after intradermal challenge with OVA or PBS. The number of mast cells in the OVA challenge ear was then subtracted from the PBS challenge ear. As seen in Figure 1E, chronically infected animals had significantly fewer degranulated mast cells after OVA challenge than Sensitized animals.

Given that Sensitized + Infected animals had lower levels of OVA-specific IgE, decreased IL-4 production by basophils, and reduced mast cell degranulation following OVA challenge, we next tested whether infection protected against clinical allergic responses using a local anaphylaxis assay (LAA). The LAA monitors changes in vascular permeability by quantifying dye extravasation in the tissue following allergen challenge (10). Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected animals did not show any difference in dye extravasation (Fig. 1F), indicating that 10 weeks of infection with L. sigmodontis does not protect against the symptoms of type I hypersensitivity in previously sensitized mice. These results suggest that although L. sigmodontis suppresses several immunological drivers of type I hypersensitivity (allergen-specific IgE, basophil activation, and mast cell degranulation), the extent to which it does so is not sufficient to appreciably alter clinical responses that occur after local allergen challenge.

Chronic L. sigmodontis infection protects against late phase ear swelling due to type III hypersensitivity

We next assessed the effect chronic helminth infection had on late phase inflammation after intradermal allergen exposure. Animals were challenged with 20 μg OVA in the right ear and PBS in the left ear, and ear thickness was serially measured over a period of four days using a micrometer.

Unsensitized animals (Infected and Mock groups) did not respond to OVA challenge and had negligible ear swelling throughout the time course (Fig. 2A). During the early time points, 1 and 2 hours after challenge, Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected animals exhibited the same degree of swelling, confirming results from the LAA that infection does not suppress immediate allergic responses. However, at all of the late phase time points (12-96 hours post-challenge) Sensitized + Infected animals had significantly less ear swelling than Sensitized animals (Fig. 2A).

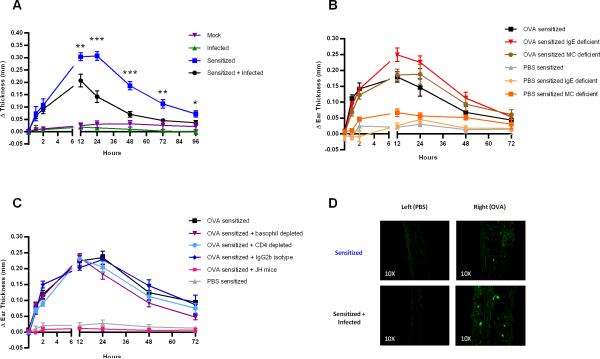

Figure 2.

Immune complex-mediated ear swelling was significantly reduced Sensitized + Infected animals. (A) Ear swelling was measured by micrometer for four days following OVA and PBS challenge at 10 weeks post-infection. Data points for Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected groups were compared at each time point by the Mann Whitney test. Data are representative of two independent experiments composed of 4-5 BALB/c mice per group. (B) Ear swelling for uninfected OVA and PBS sensitized mice on C57BL/6 background, including IgE deficient, mast cell deficient (Wsh), and C57BL/6 control mice. Data are representative of two independent experiments composed of three animals per group. (C) Ear swelling for uninfected OVA and PBS sensitized mice on BALB/c background, including antibody deficient JH and BALB/c control mice. Basophils and CD4 cells were depleted from BALB/c mice by administration of anti-CD200R and anti-CD4, respectively, 24 hours prior to challenge. Depletion was confirmed 72 hours post-challenge by flow cytometry. Data are representative of two independent experiments composed of three animals per group. Δ Thickness represents differences in ear thickness between PBS and OVA challenged ears (OVA-PBS) for each animal. (D) Visualization of immune complexes in OVA sensitized BALB/c mice by immunohistochemistry 3 hours after PBS or OVA challenge by staining with anti-mouse IgG-FITC. Error bars represent ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

To determine whether late phase ear swelling was due to type I hypersensitivity, we performed the ear thickness assay on mast cell deficient (Wsh, C57BL/6 background), IgE deficient (C57BL/6 background), and C57BL/6 control mice. When OVA sensitized mice from each strain were challenged with OVA, they exhibited increases in ear thickness comparable to sensitized wild-type mice (Fig. 2B). These data indicate that neither IgE nor mast cells are required for late phase swelling.

Because previous studies have implicated basophils as important mediators of late phase swelling in type I hypersensitivity (13), we next evaluated whether basophils were contributing to the late phase swelling observed in our allergy model. To deplete basophils, BALB/c mice were given 50 μg anti-CD200R3 24 hours prior to OVA challenge. Flow cytometry demonstrated that this approach resulted in >85% basophil depletion for the duration of the monitoring period (data not shown). As seen in Figure 2C, basophil depletion did not reduce late phase ear swelling in response to intradermal OVA challenge, indicating that basophils were not important for swelling in our allergy model. Similar results were found for OVA sensitized BALB/c mice that were depleted of CD4 T cells, indicating that late phase swelling was not due to type IV hypersensitivity (Fig. 2C). Finally, platelet depletion by i.p. administration of anti-CD41 24 hours prior to challenge also had no effect on ear swelling (Supplement 2).

It was only when antibody-deficient JH mice (BALB/c background) were used that we observed complete abrogation of the late phase response (Fig. 2C). This result suggests that late phase ear swelling is due to immune complex-mediated type III hypersensitivity.

To assess for this, we performed immunohistochemistry on ears from Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected animals 3 hours after OVA challenge. Anti-mouse IgG conjugated to FITC was then used to visualize immune complex deposition in the ear tissue via confocal microscopy (Fig. 2D). Immune complexes were readily visible in both groups, confirming that late phase ear swelling in our model is due to type III hypersensitivity. Indeed, the time course of the swelling observed in our model is most consistent with that of immune complex-mediated inflammation.

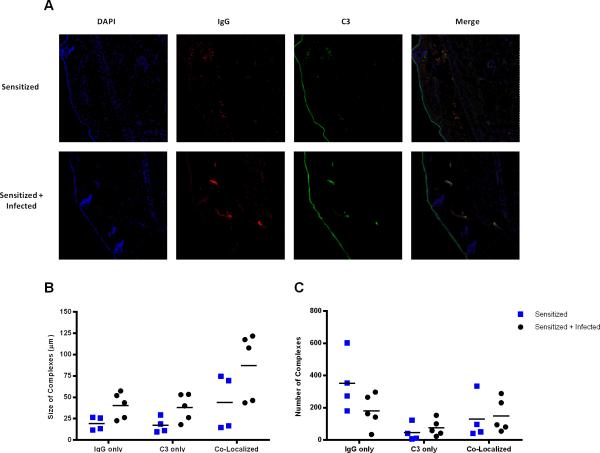

Infection does not affect immune complex size, number, or complement activation

To evaluate whether infection induces changes in immune complex morphology, we performed immunohistochemistry for IgG and C3 and visualized immune complexes via confocal microscopy. Both Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected animals showed IgG, C3, and co-localized immune complex staining (Fig 3A). There were no significant differences between groups with regards to immune complex size or number (Fig. 3B, C). These results suggest that the mechanism by which infection protects against ear swelling due to type III hypersensitivity likely occurs downstream of immune complex formation.

Figure 3.

Chronic L. sigmodontis infection does not alter immune complex morphology. Immunohistochemistry was performed on ears 3 hours after OVA challenge. Ear sections were stained with DAPI, anti-mouse IgG-Texas Red and anti-mouse C3-FITC to visualize immune complexes. Data are from two independent experiments with 2-3 BALB/c mice per group. (A) Representative images taken with a Zeiss 710 confocal microscope at 10X with 50% zoom to show detail. For each animal, the entire ear was imaged and analyzed using the Puncta Analyzer plugin on ImageJ. (B) Average size of IgG only, C3 only, and co-localized complexes. (C) Number of IgG only, C3 only, and co-localized complexes.

Chronic L. sigmodontis infection reduces levels of allergen-specific IgG

Total IgG, total IgG2a, OVA-specific IgG2a, and OVA-specific IgG1 antibody levels were measured by ELISA at 10 weeks post-infection. Sensitized + Infected animals had elevated levels of total IgG (Fig. 4A) but a significant reduction in total IgG2a (Fig. 4B), the predominant IgG subclass that participates in immune complex formation. Furthermore, OVA-specific IgG2a levels were also significantly lower in Sensitized + Infected animals compared to Sensitized animals. The reduction in OVA-specific IgG was not subclass-dependent, as OVA-specific IgG1, an anti-inflammatory IgG subclass associated with tolerance (14), was also lower in Sensitized + Infected animals compared to the Sensitized group. (Fig. 4D.)

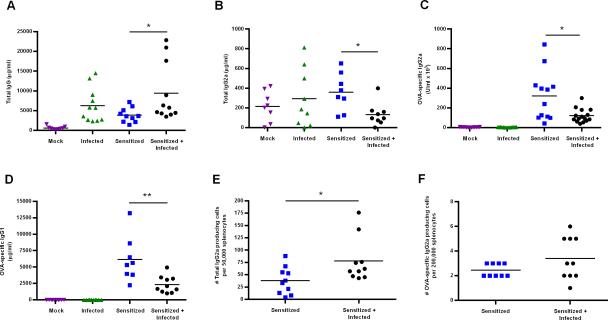

Figure 4.

Chronically infected animals had reduced levels of allergen-specific antibodies. Levels of circulating total IgG (A), total IgG2a (B), OVA-specific IgG2a (C), and OVA-specific IgG1 were detected by ELISA at 10 weeks post-infection. ELISPOT assays for total IgG2a (E) and OVA-specific IgG2a (F) were performed on live, frozen splenocytes that were isolated from animals at the 10 week time point. Data are representative of two independent experiments with 4-5 BALB/c mice per group. Statistical differences between Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected groups were determined by the Mann Whitney test. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

To ascertain whether the reduction in OVA-specific IgG2a was due to a defect in antibody production, ELISPOT assays were performed. Sensitized + Infected animals had higher numbers of total IgG2a (Fig. 4E) and similar numbers of OVA-specific IgG2a (Fig. 4F) producing cells as Sensitized animals. These data indicate that antibody production is not compromised during chronic infection, suggesting that the reduction in OVA-specific antibody levels in infected animals may be due to increased antibody catabolism.

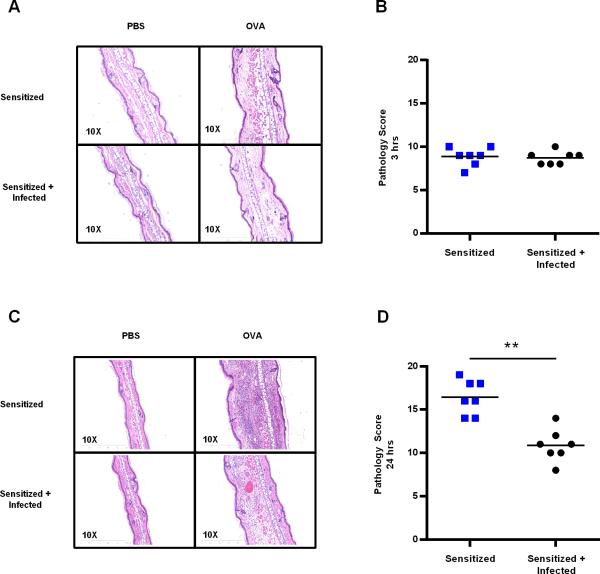

Infection significantly reduces pathology at 24 hours post challenge

Ear pathology was assessed by H&E stain at 3 hours post challenge (Fig. 5A), the time point at which immune complexes were visualized by immunohistochemistry, and 24 hours post challenge (Fig. 5C), the time point of maximal ear swelling. A blinded pathologist scored the tissue sections based on severity and focality of edema, hemorrhage, necrosis, and cellularity. Scores for OVA challenged ears were comparable between Sensitized + Infected and Sensitized animals at the 3 hour time point (Fig. 5B). At 24 hours post challenge, ears of Sensitized animals exhibited marked cellular infiltration. As seen in figure 5C, cellular infiltration was also present in Sensitized + Infected animals, but to a much lower degree. Sensitized + Infected animals had a significant reduction in pathology score at 24 hours post challenge (Fig. 5D), confirming the protective effect observed when performing the ear thickness assay.

Figure 5.

Sensitized + Infected animals exhibited reduced ear pathology 24 hours post-challenge. (A) H&E stain of ear tissue at 3 hours post-challenge, the time point at which immune complexes were detected by immunohistochemistry. (B) Pathology score for 3 hour time point. Four parameters were measured (hemorrhaging, edema, necrosis, and cellularity) on the basis of severity (0-absent, 1-mild, 2-moderate, or 3-severe) and focality (0-absent, 1-focal, 2-intermediate, and 3-diffuse) for a total maximum score of 24. (C) H&E stain of ear tissue 24 hours post-challenge, the time point at which there was the greatest difference in ear swelling between groups. (D) Pathology score for 24 hour time point. Data are representative of two independent experiments with 3-4 BALB/c mice per group. Statistical differences between groups were analyzed by the Mann Whitney test. ** p < 0.01.

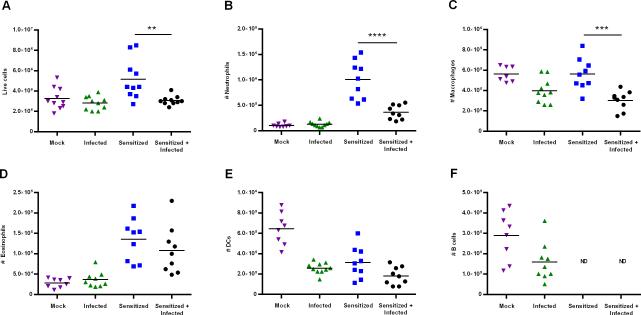

Infection reduces neutrophil and macrophage recruitment following OVA challenge

After observing reduced swelling and cellularity in Sensitized + Infected animals, we quantified the specific cell types recruited to the ear tissue after allergen exposure. A single cell suspension of ear tissue was prepared 24 hours after OVA challenge. Cells were enumerated on a hemacytometer and then stained for flow cytometry to determine the cell types present. The number of live cells in the ear tissue was significantly reduced in Sensitized + Infected animals compared to Sensitized animals (Fig. 6A), however there was no difference in the number or percentage of dead cells between groups (data not shown).

Figure 6.

Sensitized + Infected animals showed impaired neutrophil and macrophage recruitment to the ear following allergen challenge. (A) 24 hours after OVA challenge, a single cell suspension ear tissue was generated and live cell counts were obtained by hemacytometer. Flow cytometry was then performed on the cell suspensions to determine the number of (B) neutrophils [F4/80−Ly6G+], (C) macrophages [F4/80+], (D) eosinophils [CD11c−CD45+SiglecF+], (E) dendritic cells [CD11c+], and (F) B cells [CD19+] present. Gates were determined using fluorescence minus one controls. Data are representative of two independent experiments with 4-5 BALB/c mice per group. Statistical differences between groups were analyzed by the Mann Whitney test. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Neutrophils are the primary cell type that participates in immune complex-mediated inflammation, and the severity of type III hypersensitivity reactions can be correlated to the number of neutrophils present (15). We found a significant reduction in the number of neutrophils recruited in Sensitized + Infected animals following OVA challenge (Fig. 6B). Macrophages were also present in lower numbers in infected animals (Fig. 6C). There was no difference in the numbers of eosinophils (Fig. 6D) or dendritic cells (Fig. 6E) between Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected groups. B cell numbers were below the limit of detection for Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected mice (Fig. 6F).

To ensure that differences in cellular infiltration were not due to reduced availability of circulating white blood cells, we performed a CBC analysis on animals 10 weeks post-infection. Sensitized + Infected animals had equal or higher numbers of circulation lymphocytes and granulocytes, including neutrophils and monocytes (data not shown). These data indicate that helminth infection suppresses neutrophil and monocyte recruitment to immune complexes.

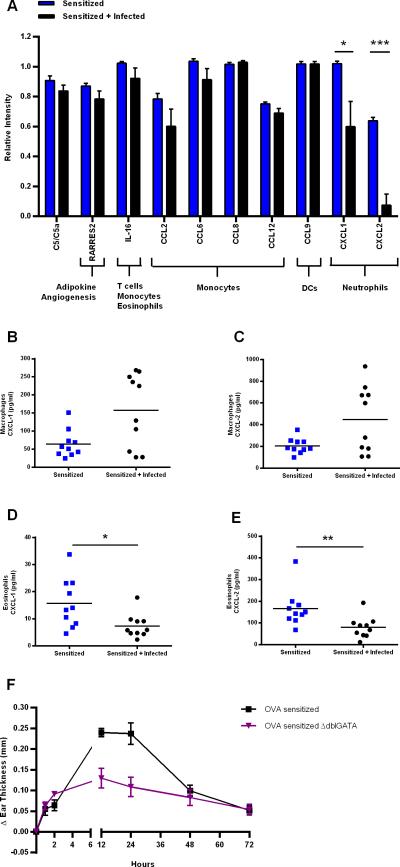

Infection suppresses neutrophil-specific chemokine production by eosinophils

To investigate the underlying mechanism driving impaired cell recruitment in Sensitized + Infected animals, we used a chemokine profiler array to measure relative concentrations of chemokines present in the ear 6 hours after OVA challenge. Of the 25 chemokines assayed by the array, 10 were present at detectable levels in the ear tissue 6 hours after challenge. Of these, only neutrophil-specific chemokines CXCL-1 (KC) and CXCL-2 (MIP-2) were significantly reduced in Sensitized + Infected animals (Fig. 7A). These data correlate with the reduced neutrophil recruitment observed in Figure 6B. The remaining chemokines, including monocyte-specific chemokines CCL-2, CCL-6, and CCL-12, tended to be only slightly lower in Sensitized + Infected animals compared to Sensitized animals. While other time points may have elicited a more robust difference between groups, the slight reduction in multiple monocyte-specific chemokines in infected animals may have had a cumulative effect on macrophage recruitment following OVA challenge (Fig. 6C).

Figure 7.

Neutrophil-specific chemokine production by eosinophils was reduced in Sensitized + Infected animals. (A) Chemokine array performed on ear tissue 6 hours after OVA challenge. Both ears were challenged with OVA and pooled for each animal. Tissues were homogenized with FastPrep lysing matrix D beads in the presence of protease inhibitors, and supernatants assayed for the presence of 25 distinct chemokines. To determine the cell types responsible for neutrophil-specific chemokine production, macrophages were isolated from the peritoneal cavity and an eosinophil-enriched cell fraction was derived from splenocytes. Cells were stimulated with immune complexes for 6 hours in vitro and supernatants were harvested to assess macrophage production of CXCL-1 (B) and CXCL-2 (C), and eosinophil production of CXCL-1 (D) and CXCL-2 (E) by ELISA. Data are representative of two independent experiments with 4-5 BALB/c mice per group. (F) Ear swelling for uninfected OVA sensitized eosinophil-deficient ΔdblGATA (BALB/c background) and control BALB/c mice. Data are representative of two independent experiments composed of 3 animals per group. Error bars represent ± SEM. Significant differences between groups were analyzed by the Mann Whitney test. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Two cell types that release CXCL-1 and CXCL-2 in response to immune complex activation are macrophages and eosinophils (15, 16). To test the effect chronic helminth infection has on chemokine production by these cells, we next stimulated enriched populations of macrophages and eosinophils from Sensitized and Sensitized + Infected mice with immune complexes in vitro. Immune complexes were generated by combining polyclonal rabbit anti-OVA IgG antibody with OVA at a ratio of 100:1. This resulted in the formation of large, precipitating immune complexes after a 30 minute incubation at 37°C.

As seen in Figures 7B and 7C, CXCL-1 and CXCL-2 production by macrophages was greater in Sensitized + Infected animals than Sensitized animals, though the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, eosinophil production of CXCL-1 (Fig. 7D) and CXCL-2 (Fig. 7E) was markedly reduced in chronically infected mice compared to Sensitized mice (P values < 0.05 and <0.01, respectively). The suppression of CXCL-2 production by eosinophils in Sensitized + Infected animals was more robust than suppression of CXCL-1 production, consistent with the data obtained by the chemokine array (Fig. 7A). These results suggest that the suppression of neutrophil-specific chemokine production in chronically infected mice may be due to suppression of eosinophil function.

Although eosinophils are known to produce chemokines, the role eosinophils play during type III hypersensitivity responses has yet to be defined. To determine whether eosinophils were required for type III hypersensitivity we sensitized ΔdblGATA (eosinophil deficient) mice to OVA, challenged the ears with OVA and PBS, and monitored ear thickness over time. As seen in Figure 7F, eosinophil deficient animals exhibit reduced ear swelling compared to BALB/c control animals. This indicates eosinophils are important for eliciting immune responses to immune complex deposition.

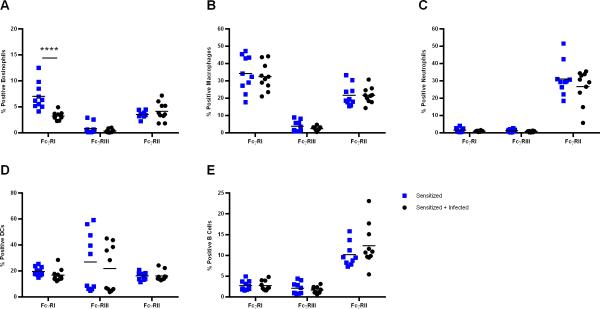

Eosinophil expression of FcγRI is suppressed in chronically infected animals

To understand why eosinophils from chronically infected animals produced lower levels of neutrophil-specific chemokines, we measured the surface expression of activating Fc gamma receptors I (FcγRI) and III (FcγRIII), and inhibitory Fc gamma receptor II (FcγRII) on multiple cell types by flow cytometry.

Sensitized + Infected animals showed a significant reduction in the percentage of eosinophils expressing FcγRI compared to Sensitized animals (Fig. 8A). There was no difference in the percentage of eosinophils expressing the other activating receptor FcγRIII, or the inhibitory receptor FcγRII. Furthermore, there was no difference between groups with regard to the percentage of macrophages (Fig. 8B), neutrophils (Fig. 8C), dendritic cells (Fig. 8D) or B cells (Fig. 8E) expressing FcγRI, FcγRII, or FcγRIII. The only appreciable difference in receptor expression levels on the surface of any cell type was a reduction in FcγRI on eosinophils, as indicated by MFI values (Supplement 3). We have also observed that eosinophils from Sensitized + Infected animals have decreased expression of FcεRI (data not shown), indicating that filariae may be exerting global suppression of eosinophil function by decreasing important antibody receptors on the cell surface. Notably, the absence of neutrophils expressing FcγRI or FcγRIII (Fig. 8C) signifies that neutrophils are not likely to be major contributors to the chemokine production observed from the eosinophil-enriched cell fraction (Figure 7).

Figure 8.

Infection results in decreased percentage of eosinophils expressing FcγRI. Flow cytometry was used to assess the percentage of cells expressing activating Fc gamma receptors I and III, and inhibitory Fc gamma receptor II. Single cell suspensions of live splenocytes were first gated as (A) eosinophils [CD11c−CD45+SiglecF+], (B) macrophages [F4/80+], (C) neutrophils [F4/80−Ly6G+], (D) dendritic cells [CD11c+], or (E) B cells [CD19+]. Each cell type was then gated on the basis of FcγRI [CD64+], FcγRIII [CD16+] and FcγRII [CD32+] positivity using fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls. Data are representative of two independent experiments with 4-5 BALB/c mice per group. Error bars represent ± SEM. Significant differences between groups were analyzed by the Mann Whitney test. ****p < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that chronic helminth infection with the filarial parasite L. sigmodontis protects against type III, but not type I, hypersensitivity in a murine ear challenge model. Protection was associated with reduced neutrophil influx into the ear, decreased local levels of the CXCL-1 and CXCL-2 neutrophil chemokines, and diminished production of these chemokines by eosinophils in response to immune complex stimulation.

In our first experiment, we evaluated whether chronic L. sigmodontis infection protects against type I hypersensitivity in mice previously sensitized against ovalbumin (OVA). Even though 10 weeks of infection resulted in lower OVA-specific IgE levels, reduced basophil activation in response to OVA, and decreased numbers of degranulated tissue mast cells after intradermal OVA challenge, no clinical protection against immediate local anaphylaxis was observed using an Evans Blue assay to measure changes in vascular permeability. Future work will address whether infection can protect against systemic anaphylaxis. Both local and systemic anaphylaxis are type I hypersensitivity responses, however local anaphylaxis is primarily due to mast cell activation whereas systemic anaphylaxis is due to the activity of basophils and/or IgG-mediated activation of inflammatory macrophages (17).

Although numerous studies have shown helminths protect against allergy when given prior to sensitization, the few animal studies that have infected after sensitization have produced mixed results (18-21). Given that L. sigmodontis was shown to be beneficial when given prior to allergic sensitization (8), it is likely that helminth infections are more effective at blunting sensitization than preventing symptoms after sensitization has occurred. Thus, these results support the conclusion that helminth infections may not readily protect against immediate hypersensitivity reactions in previously sensitized individuals. Indeed, to date the only two clinical studies that have prospectively tested whether helminth infections can be given to protect against allergic disease have been negative (1, 2).

That said, the results of our experiment do not completely rule out the possibility that helminth infections can have beneficial effects on individuals with established immediate hypersensitivities. Indeed, the major immunologic correlates of type I hypersensitivity (allergen-specific IgE as well as basophil activation and mast cell degranulation in response to allergen) were decreased in the setting of L. sigmodontis infection. We speculate that these decreases did not translate into clinical protection because either A) they were not of sufficient magnitude for the dose of allergen given, or B) infection did not occur for a long enough period of time. With regards to magnitude of change, the decrease in OVA specific-IgE may not have been great enough to decrease mast cell sensitivity to IgE cross-linking. In terms of duration, a 10 week infection may not be long enough to substantially alter the repertoire of IgE antibodies on the surface of tissue-resident mast cells. Because these are long-lived cells with slow turnover at tissue sites (22), it is possible that decreases in circulating levels of allergen-specific IgE may take months to result in substantial reductions in mast cell sensitivity to allergen. Testing whether a longer exposure to helminths can provide clinical protection against immediate hypersensitivity will be the focus of future studies.

Interestingly, while we did not observe clinical protection against type I hypersensitivity, we did see significant protection against late ear swelling due to type III hypersensitivity. Type III hypersensitivity is driven by immune complex deposition and is a major pathogenic mechanism for diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (23), serum sickness (24), and post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (25). To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically demonstrate that helminth infection can protect against immune complex-mediated hypersensitivity.

While immune complexes were visualized at 3 hours post-challenge and showed no difference in size or number between groups, a reduction in pathology and cellular infiltration was observed at 24 hours post-challenge (Fig. 5). This difference in pathology was associated with fewer neutrophils and macrophages trafficking to the site of allergen challenge (Fig. 6).

To determine why Sensitized + Infected animals had fewer cells recruited to the ear, we monitored chemokine production after OVA challenge and in vitro immune complex stimulation. We observed a reduction in the neutrophil attractant chemokines CXCL-1 and CXCL-2, and noted that eosinophils were specifically impaired in their ability to secrete these chemokines (Fig. 7). Conversely, macrophage production of chemokines was not suppressed, and in some animals was even exacerbated. Although macrophages are considered to be the primary cell type responsible for neutrophil-specific chemokine production, eosinophils have the capacity to produce large volumes of these chemokines in response to stimulation (26). Confirming this, eosinophil-deficient ΔdblGATA mice exhibit attenuated inflammation following OVA challenge. To our knowledge, this is the first time eosinophils have been shown to be important contributors to immune complex-mediated inflammation, likely through the production of neutrophil-specific chemokines.

In addition to neutrophils, the number of macrophages present in the ear tissue was significantly suppressed in chronically infected animals (Fig 6), although this was not reflected by a substantial suppression of monocyte-specific chemokines produced 6 hours post challenge (Fig. 7). While assessing chemokine production at other time points may reveal more distinct differences, reduced monocyte recruitment may have been due to an impaired ability of monocytes to respond to chemokines, rather than reduced chemokine production. Indeed, macrophages and neutrophils from mice infected with Echinococcus multilocularis lost their ability to migrate in response to stimulation with worm antigen or endotoxin-activated mouse serum (27). Interestingly, this inhibitory effect was observed for chronic, but not acute, infection. Furthermore, Taeniaestatin, a protease inhibitor isolated from Taenia taeniaeformis, prevented neutrophil chemotaxis in response to C5a (28).

The activation of cells by immune complexes involves ligation of activating (FcγRI and FcγRIII) and inhibitory (FcγRII) receptors. The ratio of activating and inhibitory receptor binding plays an integral role in determining whether cellular responses will be pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory. While the number of circulating eosinophils was not decreased in Sensitized + Infected mice, the percentage of eosinophils expressing FcγRI was reduced by 50% compared to Sensitized animals (Fig. 8). Furthermore, the amount of FcγRI expressed on the surface of eosinophils was also reduced, as indicated by MFI data (Supplement 3). This suggests that chronic L. sigmodontis infection lowers the propensity for eosinophils to express FcγRI, which in turn reduces the ability of this cell type to produce chemokines upon immune complex stimulation (Supplement 4).

In addition to establishing systemic immunoregulatory networks, helminths release immune-modulatory factors in the form of excretory-secretory products. Because only eosinophils displayed a marked difference in FcγRI expression, it is possible that L. sigmodontis worms release factors that directly suppress eosinophils. Previous studies have already shown that worm products are associated with altered eosinophil function and reduced chemotaxis (29-31). The selective suppression of FcγRI expression on eosinophils during the course of infection would be advantageous to the parasite, as eosinophils are known to mediate worm clearance through antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) (32).

The fact that eosinophils were the only cell type to display decreased FcγRI expression and chemokine production suggests that we may be able to develop medications that specifically suppress eosinophil function. Because eosinophils exhibited enhanced immunoregulation during infection, worm-mediated therapies may be particularly well-suited for eosinophil-driven diseases.

Interestingly, even though they did not play a mechanistic role in protecting mice against the allergic responses evaluated in this study, both OVA-specific IgG and IgE levels were lower in the setting of chronic L. sigmodontis infection. The reduction in allergen-specific antibody levels is an interesting phenomenon, as other groups have reported similar results when infection is given prior to sensitization (8, 33, 34). In contrast to reductions in antibodies specific to environmental or self-antigens, levels of L. sigmodontis-specific and non-specific antibodies rise throughout the course of infection (35). Indeed, our ELISA and ELISPOT data (Fig. 4) confirm that infected animals are not compromised in their ability to elicit humoral immune responses.

We therefore hypothesize that decreases in allergen-specific antibodies is due to increased antibody catabolism. We speculate that the host increases antibody catabolism in an effort to counterbalance the high levels of antibodies produced during infection. To this effect, infection may be providing an endogenous source of antibodies that produces beneficial effects similar to intravenous immunoglobulin administration. To test this, future studies would likely investigate the role of FcRn for IgG catabolism, or CD23 for IgE catabolism (36), during the course of infection.

In summary, we have shown that chronic infection with the rodent filarial worm L. sigmodontis protects the host from type III hypersensitivity. The mechanisms by which this occurs appears to be multifactoral, with protection being associated with fewer neutrophils and macrophages infiltrating the site of allergen challenge, reduced neutrophil-specific chemokine production, and a decrease in eosinophil expression of FcγRI. Because the immunological markers of type I hypersensitivity were decreased in chronically infected animals, L. sigmodontis may have the potential to protect against immediate hypersensitivity reactions under some experimental conditions. Future studies would likely investigate the use of repeated infections to extend the length of infection, as this would allow for mast cell turnover to occur in an immune-regulated setting. Furthermore, future experiments using worm antigen preparations in place of live worm infection would allow for the characterization of the specific antigens responsible for host protection from hypersensitivity diseases. From a translational perspective, the finding that L. sigmodontis infection protects against type III hypersensitivity in previously sensitized animals suggests that helminth-derived products may potentially be developed as therapeutics for immune-complex mediated diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Cara Olsen for help with statistical analyses, and Kateryna Lund and Dr. Dennis McDaniel from the Uniformed Services University Biomedical Instrumentation Center for flow cytometry and confocal microscopy assistance. We thank Dr. John Semple from the Keenan Research Centre in the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute at St. Michaels Hospital in Toronto for the generous donation of anti-CD41 antibody. We also acknowledge Dr. John Atkinson and Dr. Xiaobo Wu from Washington University for their insightful discussions on complement activation in this model.

Funding: This work was supported by NIAID grant 1R01AI076522 and Uniformed Services University grant R073UE247414.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bager P, Arnved J, Rønborg S, Wohlfahrt J, Poulsen LK, Westergaard T, Petersen HW, Kristensen B, Thamsborg S, Roepstorff A, Kapel C, Melbye M. Trichuris suis ova therapy for allergic rhinitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010;125:123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feary JR, Venn AJ, Mortimer K, Brown AP, Hooi D, Falcone FH, Pritchard DI, Britton JR. Experimental hookworm infection: a randomized placebo-controlled trial in asthma. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 2010;40:299–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03433.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans H, Mitre E. Worms as therapeutic agents for allergy and asthma: Understanding why benefits in animal studies have not translated into clinical success. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;135:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann W, Petit G, Schulz-Key H, Taylor D, Bain O, Le Goff L. Litomosoides sigmodontis in mice: Reappraisal of an old model for filarial research. Parasitol. Today. 2000;16:387–389. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01738-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfaff AW, Schulz-Key H, Soboslay PT, Taylor DW, MacLennan K, Hoffmann WH. Litomosoides sigmodontis cystatin acts as an immunomodulator during experimental filariasis. Int. J. Parasitol. 2002;32:171–178. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor MD, LeGoff L, Harris A, Malone E, Allen JE, Maizels RM. Removal of regulatory T cell activity reverses hyporesponsiveness and leads to filarial parasite clearance in vivo. J. Immunol. 2005;174:4924–4933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor MD, van der Werf N, Harris A, Graham AL, Bain O, Allen JE, Maizels RM. Early recruitment of natural CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells by infective larvae determines the outcome of filarial infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:192–206. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dittrich AM, Erbacher A, Specht S, Diesner F, Krokowski M, Avagyan A, Stock P, Ahrens B, Hoffmann WH, Hoerauf A, Hamelmann E. Helminth infection with Litomosoides sigmodontis induces regulatory T cells and inhibits allergic sensitization, airway inflammation, and hyperreactivity in a murine asthma model. J. Immunol. 2008;180:1792–1799. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larson D, Hübner MP, Torrero MN, Morris CP, Brankin A, Swierczewski BE, Davies SJ, Vonakis BM, Mitre E. Chronic helminth infection reduces basophil responsiveness in an IL-10–dependent manner. J.Immunol. 2012;188:4188–4199. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans H, Killoran KE, Mitre E. Measuring local anaphylaxis in mice. e5200. 2014 doi: 10.3791/52005. Epub2014/10/14/ (doi:10.3791/52005) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hübner MP, Torrero MN, McCall JW, Mitre E. Litomosoides sigmodontis: A simple method to infect mice with L3 larvae obtained from the pleural space of recently infected jirds (Meriones unguiculatus). Exp. Parasitol. 2009;123:95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shannon JG, Hasenkrug AM, Dorward DW, Nair V, Carmody AB, Hinnebusch BJ. Yersinia pestis subverts the dermal neutrophil response in a mouse model of bubonic plague. MBio. 2013;4:e00170. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00170-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukai K, Matsuoka K, Taya C, Suzuki H, Yokozeki H, Nishioka K, Hirokawa K, Etori M, Yamashita M, Kubota T, Minegishi Y, Yonekawa H, Karasuyama H. Basophils play a critical role in the development of IgE-mediated chronic allergic inflammation independently of T cells and mast cells. Immunity. 2005;23:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pandey MK. Molecular basis for downregulation of C5a-mediated inflammation by IgG1 immune complexes in allergy and asthma. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013;13:596–606. doi: 10.1007/s11882-013-0387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jönsson F, Mancardi DA, Albanesi M, Bruhns P. Neutrophils in local and systemic antibody-dependent inflammatory and anaphylactic reactions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013;94:643–656. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1212623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakajima H, Gerald GJ, Kita H. Constitutive production of IL-4 and IL-10 and stimulated production of IL-8 by normal peripheral blood eosinophils. J. Immunol. 1996;156:4859–4866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelman F. Anaphylaxis: Lessons from mouse models. J. Immunol. 2007;120:516–517. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Negrão-Corrêa D, Silveira MR, Borges CM, Souza DG, Teixeira MM. Changes in pulmonary function and parasite burden in rats infected with Strongyloides venezuelensis concomitant with induction of allergic airway inflammation. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:2607–2614. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2607-2614.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson MS, Taylor MD, Balic A, Finney CAM, Lamb JR, Maizels RM. Suppression of allergic airway inflammation by helminth-induced regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1199–1212. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wohlleben G, Trujillo C, Muller J, Ritze Y, Grunewald S, Tatsch U, K., Erb J. Helminth infection modulates the development of allergen-induced airway inflammation. Int. Immunol. 2004;16:585–596. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarrett E, Mackenzie S, Bennich H. Parasite-induced ‘nonspecific’ IgE does not protect against allergic reactions. Nature. 1980;283:302–304. doi: 10.1038/283302a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiernan JA. Production and life span of cutaneous mast cells in young rats. J. Anat. 1979;128:225–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pieterse E, van der Vlag J. Breaking immunological tolerance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:164. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko JH, Chung WH. Serum sickness. Lancet. 2013;381:e1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman J, van de Rijn I, Ohkuni H, Fischetti VA, Zabriskie JB. Immunological studies of post-streptococcal sequelae. Evidence for presence of streptococcal antigens in circulating immune complexes. J. Clin. Invest. 1984;74:1027–1034. doi: 10.1172/JCI111470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rose CE, Lannigan JA, Kim P, Lee JJ, Fu SM, Sung SSJ. Murine lung eosinophil activation and chemokine production in allergic airway inflammation. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2010;7:361–374. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2010.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alkarmi T, Behbehani K. Echinococcus multilocularis: Inhibition of murine neutrophil and macrophage chemotaxis. Exp. Parasitol. 1989;69:16–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(89)90166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leid RW, Grant RF, Suquet CM. Inhibition of equine neutrophil chemotaxis and chemokinesis by a Taenia taeniaeformis proteinase inhibitor, taeniaestatin. Parasite Immunol. 1987;9:195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1987.tb00500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rzepecka J, Donskow-Schmelter K, Doligalska M. Heligmosomoides polygyrus infection down-regulates eotaxin concentration and CCR3 expression on lung eosinophils in murine allergic pulmonary inflammation. Parasite Immunol. 2007;29:405–413. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2007.00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin MH, Kita H, Park HY, Seoh JY. Cysteine protease secreted by Paragonimus westermani attenuates effector functions of human eosinophils stimulated with immunoglobulin G. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:1599–1604. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1599-1604.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park SK, Cho MK, Park HK, Lee KH, Lee SJ, Choi SH, Ock MS, Jeong HJ, Lee MH, Yu HS. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor homologs of Anisakis simplex suppress Th2 response in allergic airway inflammation model via CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cell recruitment. J. Immunol. 2009;182:6907–6914. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makepeace BL, Martin C, Turner JD, Specht S. Granulocytes in helminth infection - Who is calling the shots? Curr. Med. Chem. 2012;19:1567–1586. doi: 10.2174/092986712799828337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bashir MEH, Andersen P, Fuss IJ, Shi HN, Nagler-Anderson C. An enteric helminth infection protects against an allergic response to dietary antigen. J. Immunol. 2002;169:3284–3292. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Price P, Turner KJ. Immunological consequences of intestinal helminth infections. Humoral responses to ovalbumin. Parasite Immunol. 1984;6:499–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1984.tb00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torrero MN, Hubner MP, Larson D, Karasuyama H, Mitre E. Basophils amplify type 2 immune responses, but do not serve a protective role, during chronic infection of mice with the filarial nematode Litomosoides sigmodontis. J. Immunol. 2010;185:7426–7434. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng LE, Wang ZE, Locksley RM. Murine B cells regulate serum IgE levels in a CD23-dependent manner. J. Immunol. 2010;185:5040–5047. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.