Abstract

Gene therapy approaches delivering neurotrophic factors have offered promising results in both preclinical and clinical trials of Parkinson's disease (PD). However, failure of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in phase 2 clinical trials has sparked a search for other trophic factors that may retain efficacy in the clinic. Direct protein injections of one such factor, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, in a rodent model of PD has demonstrated impressive protection of dopaminergic neurons against 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) toxicity. However, protein infusion is associated with surgical risks, pump failure, and significant costs. We therefore used lentiviral vectors to deliver Igf-1, with a particular focus on the novel integration-deficient lentiviral vectors (IDLVs). A neuron-specific promoter, from the human synapsin 1 gene, excellent for gene expression from IDLVs, was additionally used to enhance Igf-1 expression. An investigation of neurotrophic effects on primary rat neuronal cultures demonstrated that neurons transduced with IDLV-Igf-1 vectors had complete protection on withdrawal of exogenous trophic support. Striatal transduction of such vectors into 6-OHDA-lesioned rats, however, provided neither protection of dopaminergic substantia nigra neurons nor improvement of animal behavior.

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) results from a gradual loss of neurons within the dopaminergic substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and their projections to the striatum.1 Therapeutic strategies using trophic factors have offered encouraging results in both preclinical and open-label clinical trials of PD.2–6 However, administration of the most promising factor, glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), was unsuccessful in double-blind, phase 2 clinical trials.7 Hence, the search for other neurotrophic factors has been stepped up.4–6,8 One such factor is insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1.

IGF-1 is well known as a peripheral growth factor (secreted mainly by hepatocytes) that regulates cell metabolism and tissue remodeling.9 A role for IGF-1 within the CNS has been identified, appearing to be both neuroprotective and neurotrophic, and important in the maintenance of adult CNS homeostasis.10,11 IGF-1 is also considered a prosurvival factor, upregulated in all types of brain injuries.12 IGF-1 exerts its multiple effects through binding to IGF-1 receptors, phosphorylation of which activates multiple downstream signaling pathways, resulting in inhibition of apoptosis and regulation of both cell differentiation and cell proliferation.13–15

The exact role of IGF-1 in PD remains unclear, with studies reporting a decrease in plasma levels associated with cognitive decline.16 Conversely, in postmortem PD samples, an increase in plasma IGF-1 levels was observed,17 suggesting that there may be a compensatory increase in IGF-1 levels due to the ongoing cell loss. Guan and colleagues18 and Offen and colleagues19 demonstrated IGF-1 neuroprotection against 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) toxicity in rat brain and dopamine toxicity in human neuroblastoma and rodent neuronal cell cultures, respectively. Other studies using intracerebral injections of IGF-1 protein, after 6-OHDA lesioning of the nigrostriatal pathway, have suggested that IGF-1 administration can prevent dopaminergic cell loss and behavioral deficits in this preclinical animal model of PD.18,20,21 However, direct protein infusion via a surgically implanted pump has a number of disadvantages, including limited distribution, device-related side effects, and activation of the immune response.7,22 An alternative approach, which may overcome these disadvantages, is the use of gene therapy to deliver the gene for IGF-1 through a viral vector system.

Numerous reports have shown both efficient and stable expression of GDNF from lentiviral vectors (LVs) in preclinical animal models of PD.23–27 We have previously demonstrated that the novel integration-deficient LVs (IDLVs) are as efficient as their standard integration-proficient counterparts (IPLVs) at transducing rodent eye and brain cells in vivo28 but have enhanced biosafety due to their reduced risk of insertional mutagenesis.28,29 Our data have confirmed efficient and long-lasting in vivo transduction with IDLV-hGDNF, mediating therapeutic effects in a PD rat model.30

In the present study, the potential neuroprotective effects of IGF-1 were investigated through IDLV-mediated expression, with IPLV-Igf-1 vectors used as controls. To maximize the levels of transgene expression, which can be addressed by the choice of promoters specific to target cells,31–33 we initially examined transduction efficiency and cell-type specificity of LVs through expression of the gene encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP). We compared vectors driven by the cytomegalovirus promoter (CMVp), human glial fibrillary acidic protein promoter (GFAPp), and human synapsin 1 promoter (SYNp). In particular, LV-mediated in vivo eGFP expression from IDLV-SYNp vectors was shown to be efficient and long-term, comparable to that of their integrating counterparts. After vector transduction in rat primary ventral mesencephalic cell cultures and 6-OHDA-lesioned rats, the neuronal specificity of LV-SYNp vectors, beneficial to enhance Igf-1 expression,34 was ascertained. Further investigation of LV-mediated IGF-1 neuroprotection demonstrated enhanced in vitro survival of rat cortical neurons against withdrawal of exogenous trophic factors. Igf-1 expression from LVs was subsequently confirmed in a 6-OHDA rat model of PD, although neither dopaminergic cell survival nor animal behavioral recovery were improved after vector transduction.

Materials and Methods

Lentiviral vector production and titration

Concentrated stocks of the third-generation lentiviral vectors, both IPLVs and IDLVs, were produced by calcium phosphate transfection in HEK-293T cells as previously described.28 Lentiviral transfer plasmids used in this study were pRRLsc-CMVp-eGFP-W, pRRLsc-hGFAPp-eGFP-W, pRRLsc-hSYNp-eGFP-W, pRRLsc-CMVp-Gdnf-IRES-eGFP-W, pRRLsc-SFFVp-eGFP-CMVp-Igf-1-W, and pRRLsc-SFFVp-eGFP-hSYNp-Igf-1-W; Gdnf and Igf-1 cDNAs were from rat. All vectors were self-inactivating, contained a central polypurine tract/central termination sequence (cPPT/cTS) and woodchuck hepatitis virus posttranscriptional regulatory element (WPRE, abbreviated as W in plasmid names), and were pseudotyped with the vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G) envelope. Viral titers were quantified by flow cytometry with a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences, Oxford, UK), qPCR with a Rotor-Gene Q (Qiagen, Manchester, UK) as described,28 or with a p24 ELISA kit (SAIC, Frederick, MD) in accordance with the manufacturers' instructions.

Animals

Animal procedures were performed in accordance with the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986. Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Margate, UK) were maintained in a standard 12-hr light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. For primary cell cultures, embryonic day 14 (E14)–E15 embryos were used for ventral mesencephalic (VM) cultures, and E17–E18 embryos were harvested for cortical neuronal cultures. For in vivo work, 35 male rats weighing 250–300 g at the beginning of the study were housed (two or three rats per cage) and were split randomly into experimental groups, either for the 5-month eGFP experiment or the 6-week IGF-1 experiment.

Preparation of primary cultures of embryonic brain cells

Rat embryos were rapidly removed and kept in ice-cold dissection buffer containing 1 × Hanks' balanced salt solution (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific, Paisley, UK), penicillin (100 units/ml; PAA, Cambridge, UK), streptomycin (100 μg/ml; PAA), and 100 μM ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK). The ventral mesencephalons containing the substantia nigra or cortices were dissected under a Wild M3Z dissecting microscope (Wild Heerbrugg, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) with illumination support by a KL 2500 LCD instrument (Schott UK, Stafford, UK). Brain tissues were dissociated in 0.05% trypsin–EDTA (PAA) supplemented with 0.02% DNase I (Promega, Southampton, UK) for 5–20 min at 37°C. Tissues were washed twice in culture medium before deaggregation by repeated pipetting (p1000, p200, p20, and p10 pipettors). VM or cortical neuronal culture medium included neurobasal medium (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2% B-27 (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.25% GlutaMAX (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS; PAA), and 100 μM ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich); 10 ng/ml transforming growth factor (TGF)-βIII was also added to VM neuronal cultures. VM astroglial culture medium included Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; PAA), 1% N-2 (Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 10% FBS. The cell suspension was then passed through a 40- to 100-μm (pore size) cell strainer and subsequently centrifuged at 80–200 × g for 5 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in prewarmed culture medium. Live cells were counted by 0.2% trypan blue staining (Sigma-Aldrich). For VM neuronal cultures, 100-μl cell suspensions containing 105 live cells were plated onto 13-mm coverslips (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which had been precoated overnight with poly-d-lysine (50 μg/ml), and placed inside the wells of a 24-well plate. After 30 min for cell adhesion, each well was carefully topped up with 500 μl of culture medium. For VM astroglial cultures, 500-μl cell suspensions containing 5 × 104 live cells per well were plated in uncoated 24-well plates and cultured at 37°C for 48 hr. The supernatant, containing clumps of unattached cells (most of those were dead neurons), was aspirated and replaced with fresh medium. For cortical neuronal cultures, cells (density, 3 × 106 live cells per well) were plated in 24-well plates precoated with poly-d-lysine (50 μg/ml). Cell cultures were maintained by changing the medium every 1–3 days. The methods described in this section were amended from published methodologies of Pruszak and colleagues for VM neuronal cultures35; Takeshima and colleagues for VM astroglial cultures36; and Boulos and colleagues for cortical neuronal cultures.37

LV transduction in vitro

Cell culture medium was changed 2 hr before vector transduction. Concentrated vector stocks were diluted in medium for an optimized multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 (eGFP transducing units/ml) or an MOI of 30 (qPCR vector units/ml) and added gently to the wells; mock-treated cells received no vector.

Trophic support withdrawal strategy

The medium of cortical neuronal cultures was changed on day 1 in vitro, 2 hr before transduction with IDLVs at an MOI of 30 (qPCR vector units/ml); IDLVs included CMVp-eGFP, CMVp-Gdnf-IRES-eGFP, SFFVp-eGFP-CMVp-Igf-1, and SFFVp-eGFP-SYNp-Igf-1 vectors. Cells were maintained for 3 days before withdrawal of exogenous trophic factors. For this, the medium was aspirated; normal culture medium was added to trophic factor-supported groups whereas only neurobasal medium was added to trophic factor-free groups. Cell viability was assessed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay after an additional 3 days.

MTT assay

Cell viability was evaluated by using a colorimetric assay employing MTT (Sigma-Aldrich). A final MTT concentration of 0.5 mg/ml was added to cell cultures, which were subsequently incubated at 37°C for 3 hr. Formazan crystals produced in this reaction were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (VWR, Lutterworth, UK). The optical cell density in each well was then measured by spectrometric analysis at OD570 (the optical density at a wavelength of 570 nm), using Gen5 data analysis software (BioTek, Swindon, UK).

Immunocytochemistry

For characterization of VM cell cultures, cells were gently washed in ice-cold 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10–15 min. Fixed cells were washed twice in 1 × PBS, permeabilized in 1 × PBS-T (1 × PBS containing 0.25% Triton-X 100) for 10 min, and incubated in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) blocking buffer (in 1 × PBS-T) for 30 min. Primary antibodies were separately added and incubated at 4°C overnight. The antibody was either mouse anti-neuronal nuclei (NeuN, diluted 1:500; Millipore, Livingston, UK) or rabbit anti-Tuj1 (diluted 1:3000; Sigma-Aldrich) for neurons; rabbit anti-GFAP (diluted 1:500; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) for astrocytes; rabbit anti-Iba1 (diluted 1:500; Wako Chemicals, Osaka, Japan) for microglia; rabbit anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH, diluted 1:1000; Millipore) for dopaminergic neurons; rabbit anti-vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1, diluted 1:500; Synaptic Systems, Göttingen, Germany) for glutamatergic neurons; or rabbit anti- glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD67, diluted 1:50; Synaptic Systems) for GABAergic neurons. After three washes in 1 × PBS, cells were incubated at room temperature, for 1 hr, in the dark with the corresponding secondary antibodies diluted in 1% BSA blocking buffer. The antibody (diluted 1:500; Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific) was either goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 or goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555. After another three washes in 1 × PBS, cells were incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; 1 μg/ml) for 15 min, in the dark. Three washes in 1 × PBS were then performed. Images of cells were subsequently captured and counted. Cells incubated with only primary or secondary antibody were used as negative controls for the staining. For estimation of the percentage of eGFP-producing cells in primary cell cultures transduced with LV-eGFP vectors, cells were washed in ice-cold 1 × PBS and fixed in 4% PFA for 10–15 min. After three washes in 1 × PBS, cells were incubated with DAPI (1 μg/ml) for 15 min to stain nuclei. Another three washes in 1 × PBS were performed before cell capture.

Intrastriatal injection of LVs

Animals were kept under isoflurane-induced anesthesia (5% in 100% O2 for induction and 2.5% in 100% O2 for maintenance). The nose bar was set at −3.3 mm. All injections were made with a 25-μl Hamilton syringe held within an automated UltraMicroPump III (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL); the injection rate was 0.5 μl/min. Two burr holes were made into the skull above the right striatum with an Ideal Micro-Drill (Harvard Apparatus, Cambridge, UK). Equivalent vector titers (5 μl/hole, 109 qPCR vector copies/ml or 2 × 104 ng p24/ml) were injected according to the following stereotactic coordinates: (1) anteroposterior (AP), +1.8 mm; mediolateral (ML), −2.5 mm relative to bregma; and dorsoventral (DV), −5.0 mm relative to dura; (2) AP, 0.0 mm; ML, −3.5 mm relative to bregma; and DV, −5.0 mm relative to dura. The needle was left in place for 3 min before being retracted. In the eGFP experiment, animal groups included IPLV-SYNp-eGFP (n = 5) and IDLV-SYNp-eGFP (n = 5). In the IGF-1 experiment, animal groups (n = 5 per group) were as follows: (1) mock (0.9% sterile saline); (2) IPLV-CMVp-Igf-1; (3) IDLV-CMVp-Igf-1; (4) IPLV-SYNp-Igf-1; and (5) IDLV-SYNp-Igf-1.

6-OHDA lesioning

Two weeks after vector transduction, animals were injected with a combined solution of pargyline (5 mg/kg, intraperitoneal) and desipramine (25 mg/kg, intraperitoneal). Thirty minutes later, 6-OHDA dissolved in a solution containing 0.9% saline and 0.02% ascorbic acid was injected into the same positions as for vector administration (2 μl/site, 2.5 μg/μl). All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Drug-induced rotational asymmetry tests

In the IGF-1 experiment, animal behavior was tested weekly, from 1 week after 6-OHDA lesioning, for a period of 4 weeks. Amphetamine-induced rotational tests were carried out first, followed by apomorphine tests 3 days later. In each test, animals were acclimatized in 40-cm-diameter bowls for 30 min before injection with amphetamine (5 mg/kg, intraperitoneal; Sigma-Aldrich) or apomorphine (1 mg/kg, intraperitoneal; Tocris, Birmingham, UK). Net rotational asymmetry was assessed for 90 min postinjection as one whole head-to-tail revolution, with contralateral and ipsilateral turns being scored separately.

IGF-1/GDNF detection by ELISA

In the in vitro experiment, cortical neuronal cultures were collected on days 3 and 6 posttransduction with IDLV-Igf-1 or IDLV-Gdnf vector. In the in vivo experiment, rats receiving IPLV-Igf-1 or IDLV-Igf-1 vector, or mock-treated animals, were killed with CO2 followed by cervical dislocation. The striata were dissected and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was homogenized in complete lysis buffer (Roche, Welwyn Garden City, UK) and centrifuged at 14,000 × g, 4°C for 15 min. Levels of IGF-1 or GDNF that were produced in either cell cultures or rat striata were determined with a rat IGF-1 ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) or a human GDNF ELISA kit (Promega) in accordance with the manufacturers' instructions.

Immunohistochemistry

Rats were killed as described previously. Whole brains were fixed in 4% PFA for 3 days at 4°C. Coronal striata-containing sections from the eGFP experiment or SN-containing sections from the IGF-1 experiment were sliced on a vibrating microtome (Campden Instruments, Loughborough, UK) at a thickness of 50 μm and kept in ice-cold 1 × PBS. Sections were subsequently incubated in 1% BSA blocking buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 hr. Striata-containing sections were incubated with primary antibody, that is, mouse anti-NeuN (diluted 1:500; Millipore), rabbit anti-GFAP (diluted 1:500; Dako), or rabbit anti-Iba1 (diluted 1:500, Wako Chemicals); SN-containing sections were incubated with rabbit anti-TH (diluted 1:1000; Millipore) overnight at 4°C, followed by three washes in 1 × PBS. Sections were then incubated with goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555 antibody (diluted 1:500; Invitrogen/Thermo Fisher Scientific) as appropriate for 1 hr, in the dark. After three washes in 1 × PBS, sections were incubated with DAPI (1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min and mounted onto SuperFrost (VWR, Lutterworth, UK) slides.

Image capture

Both cultured cells and brain sections were visualized under an inverted fluorescence Axio Observer.D1 microscope. Images were taken with an AxioCam combined with AxioVision software. Equipment and software were purchased from Carl Zeiss (Cambridge, UK).

Cell counting

Because cultured cells dispersed unevenly, 9 fields per well were selected manually at the same positions in all wells to avoid bias and for more accurate statistical analysis. An image was captured from each field and the cell numbers were counted manually using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). DAPI+ cell nuclei were scored to obtain the total cell number. The DAPI channel was subsequently merged with another fluorescence channel to score the total number of a specific cell type. Averages of cell numbers from the nine fields were then used to obtain the total and marker-positive cell numbers within each well. For brain sections containing the SN, overlapping images from each section were captured and stitched automatically with AxioVision software to create a mosaic image of the section. According to The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates,38 two hemispheres of the SNpc were identified on each section. Only TH+ cells within these regions were counted (using ImageJ software), separately between the left and right hemispheres. Cell counts from approximately 30 SNpc-containing serial sections were subsequently averaged to obtain the total TH+ cell number per section of the SNpc in the corresponding brain hemisphere.

Measurement of eGFP intensity

For cultured cells, 9 fields per well of 24-well plates were selected and each field was individually captured as described previously. The intensity of eGFP in each field was scored by AxioVision software. An average of intensity from the nine fields was then taken and expressed as arbitrary units per square micrometer (a.u./μm2). For brain sections containing the striatum, after image capture the area of the striatum on each section was identified according to The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates.38 The intensity of eGFP within this area was quantified with AxioVision software and expressed as arbitrary units per square micrometer. The values from approximately 60 striatal sections from each brain were then averaged to obtain the value for the corresponding brain.

Statistical analysis

Using Prism 5 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA), data were analyzed and are shown as means ± SEM, with error bars representing the SEM. In vitro experiments were done in triplicate. Comparisons of statistical significance were assessed by one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc tests. Significance levels were set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Results

Lentiviral transduction efficiency and cell-type specificity in rat primary ventral mesencephalic cell cultures

We initially investigated transduction efficiency and transcriptional targeting of LVs through eGFP expression in rat primary VM cell cultures. IPLV- and IDLV-eGFP vectors driven by the CMVp, GFAPp, or SYNp promoter were used to transduce VM neuronal or astroglial cultures at an optimized MOI of 10 (Supplementary Fig. S1; supplementary data are available online at http://online.liebertpub.com/hum). The number of eGFP-expressing cells and eGFP intensity were evaluated 3 days after vector transduction. The types of cells expressing eGFP were studied through fluorescence colocalization with TH (for dopaminergic neurons), NeuN/Tuj1 cells (for total neurons), or GFAP (for total astrocytes).

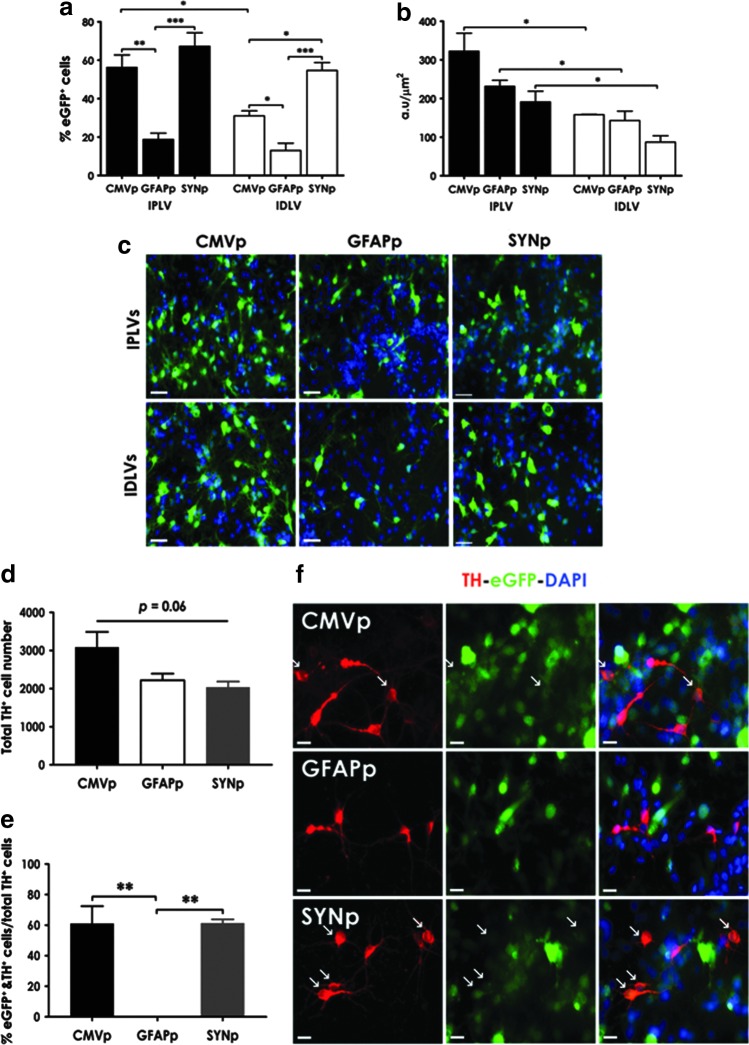

In cultures containing 60% neurons (including 4% TH+ neurons) and 13% astrocytes (as characterized in Supplementary Fig. S2a), we identified a highly significant reduction in the percentage of cells expressing eGFP from LV-GFAPp compared with LV-CMVp and LV-SYNp vectors, regardless of vector integration proficiency (Fig. 1a); and an up to 2-fold difference in eGFP intensity between IPLVs and IDLVs (Fig. 1b). Transduction efficiency of IPLV-SYNp and IPLV-CMVp vectors was comparable, but the percentage of eGFP-expressing cells after transduction with IDLV-SYNp vectors was almost double the percentage observed in cells transduced with IDLV-CMVp vectors. Representative images are shown in Fig. 1c. We also quantitated the percentage of dopaminergic neurons (TH+) expressing eGFP. Despite no significant difference in the total TH+ cell number between groups (p = 0.06; Fig. 1d), 60% of TH+ cells were transduced by either IPLV-CMVp or IPLV-SYNp vectors (Fig. 1e). The expression of eGFP was moderate in TH+ cells transduced with IPLV-CMVp or IPLV-SYNp whereas no eGFP expression in TH+ cells was observed after IPLV-GFAPp vector transduction (Fig. 1f).

Figure 1.

Lentiviral vector (LV)-mediated eGFP expression in ventral mesencephalic (VM) neuronal cultures. Rat primary VM neuronal cultures were transduced with integration-proficient (IPLV)- or integration-deficient (IDLV)-eGFP vectors at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 (eGFP transducing units), 1 day after cell seeding. (a) The percentage of total cells expressing eGFP and (b) the intensity of eGFP fluorescence were evaluated 3 days after vector transduction. (c) Representative images are shown; scale bars, 50 μm; nuclei were stained blue with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). In cultures transduced with IPLVs, (d) the total tyrosine hydroxylase-positive (TH+) cell number per well and (e) the percentage of TH+ cells expressing eGFP were additionally quantified. Total TH+ cell number was not significantly different between groups; however, efficient eGFP expression by cytomegalovirus promoter (CMVp) and human synapsin 1 promoter (SYNp), and not human glial fibrillary acidic protein promoter (GFAPp), was observed. (f) Representative images illustrate fluorescence colocalization of TH+ and eGFP+ cells. Nuclei were stained blue with DAPI; TH+ cells were stained red; eGFP+ cells produced green fluorescence. Arrows indicate TH+/eGFP+ cells; scale bars, 20 μm. Statistical analysis was by two-way analysis of variance [ANOVA; in (a) and (b)] or one-way ANOVA [in (d) and (e)] followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. Error bars represent the SEM; n = 3; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

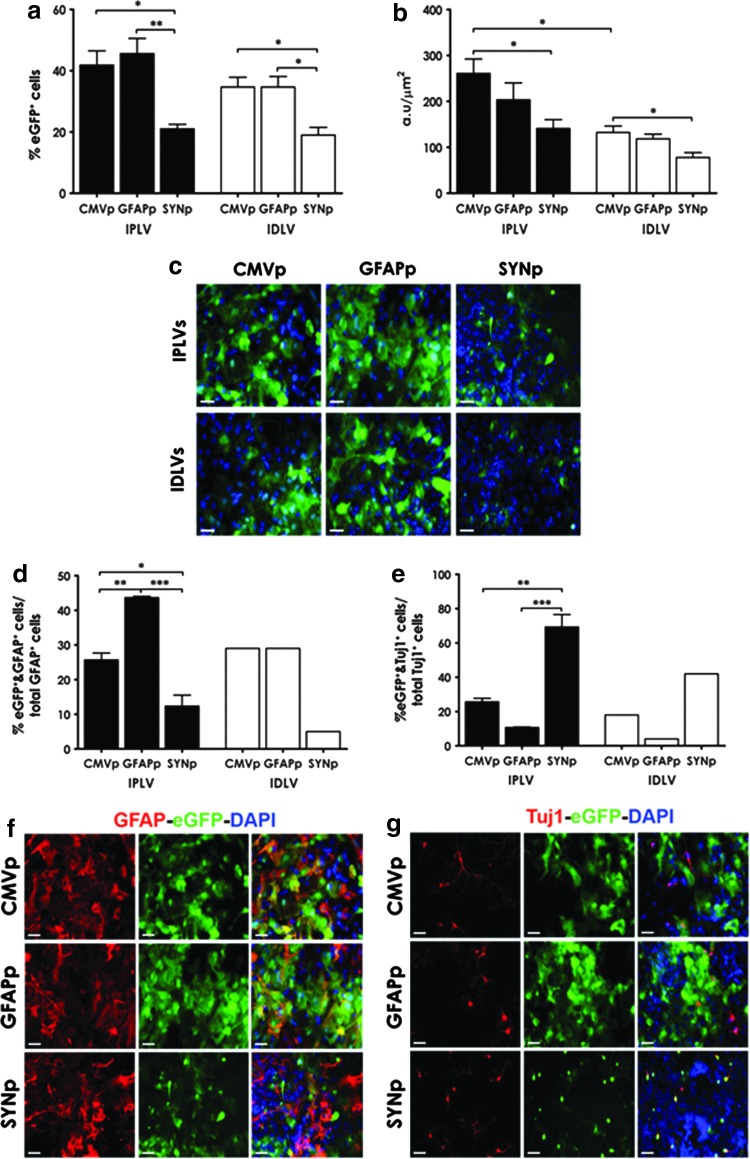

In astroglial cultures containing 36% astrocytes and 1% neurons (as characterized in Supplementary Fig. S2b), the cell-type specificity of LV-SYNp vectors was significantly different from that observed with the other vectors in both the total number of cells expressing eGFP and eGFP intensity. Significantly higher transduction efficiency of IPLVs compared with IDLVs was observed only in eGFP intensity from CMVp-eGFP vectors (Fig. 2a and b). Representative images are shown in Fig. 2c. We subsequently quantified specific cell types expressing eGFP in the transduced astroglial cultures, with a focus on astrocytes and neurons. Although there was no statistically significant difference in the number of total astrocytes (p = 0.14) or neurons (p = 0.15) between cultures (Supplementary Fig. S3), the percentage of eGFP-expressing cells from the various promoters used was significantly different (Fig. 2d and e). eGFP was preferentially expressed in astrocytes (GFAP+) after LV-GFAPp vector transduction, whereas LV-SYNp vectors mediated eGFP expression in the majority of neurons (Tuj1+). Illustrative images are shown in Fig. 2f and g.

Figure 2.

LV-mediated eGFP expression in VM astroglial cultures. Cell cultures were transduced with IPLVs (n = 3) or IDLVs (n = 3) at an MOI of 10 (eGFP transducing units) 3 days after plating the cells. (a) Percentage of cells expressing eGFP and (b) intensity of eGFP fluorescence were evaluated 3 days posttransduction. Significant differences were observed in cell-type specificity between SYNp and other promoters whereas the difference between IPLVs and IDLVs was only significant in eGFP intensity expressed from CMVp-eGFP vectors. (c) Representative images are shown; scale bars, 50 μm; nuclei were stained blue with DAPI. (d) Astrocytes or (e) neurons expressing eGFP were quantified as percentages of total astrocytes or neurons, as appropriate, showing significantly different cell-type specificity of the vectors, with LV-GFAPp predominantly targeting astrocytes and LV-SYNp predominantly targeting neurons. (f and g) Representative images from cultures transduced with IPLVs (as an example) illustrating the types of cells transduced. (f) Astrocytes were identified by GFAP+ staining, whereas (g) neurons were identified through Tuj1+ staining. Nuclei were stained blue with DAPI; GFAP+ or Tuj1+ cells were stained red; scale bars, 50 μm. Data were analyzed by one- or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. Error bars represent the SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Hence, our in vitro data demonstrated that the cell-type specificity of eGFP expression was promoter-type dependent, with expression induced predominantly in neurons, astrocytes, or both neurons and astrocytes after transduction with LV-SYNp, LV-GFAPp, or LV-CMVp vectors, respectively. The results from quantifying eGFP intensity moreover indicated higher transduction efficiency of IPLVs compared with IDLVs in most cases.

In vivo neuronal specificity of LV-SYNp vectors

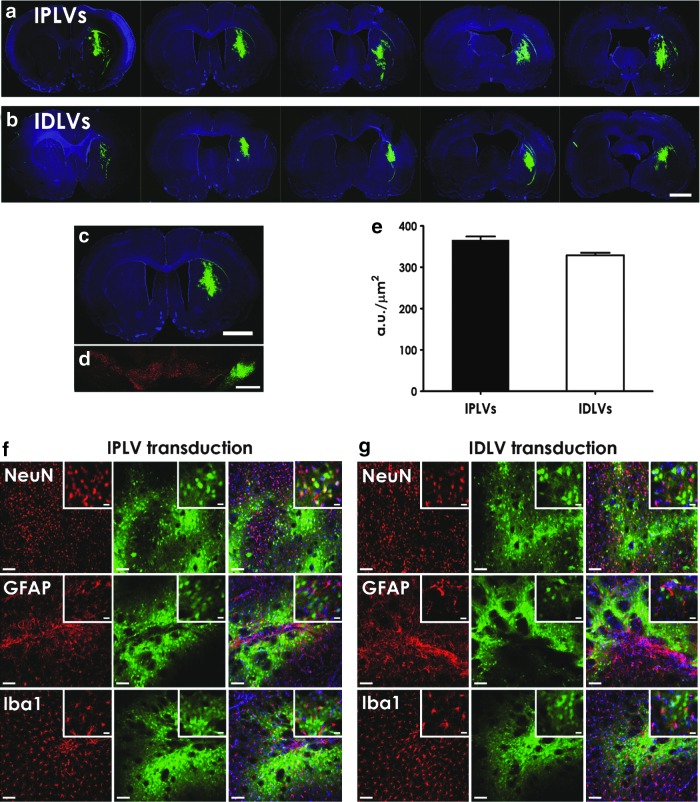

In a bid to determine whether the neuronal specificity of LV-SYNp vectors was maintained in vivo, in particular in the PD animal model, IPLV- or IDLV-SYNp-eGFP vector was injected into the right striatum of rats, followed by 6-OHDA lesioning 2 weeks later. Brains were harvested 5 months after vector injection. Successful transduction with widespread eGFP expression within the striatum was demonstrated (Fig. 3a and b). No eGFP expression was detected in the noninjected striatal hemispheres (Fig. 3c); however, there was an anterograde presence of eGFP in the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNpr), from the striatal injection site (Fig. 3d). Quantification of levels of eGFP intensity showed no significant differences in transduction efficacy between IPLV- and IDLV-SYNp vectors (p = 0.12; Fig. 3e). Further cell identification by morphology and marker expression confirmed that the majority of neurons were transduced; no significant astrocyte or microglial transduction was noticed (Fig. 3f and g). These results are consistent with the in vitro findings, confirming the neuronal specificity of LV-SYNp vectors. The data in particular demonstrated comparable transduction efficiency of IDLVs with their counterparts in the postmitotic CNS environment.

Figure 3.

Neuronal specificity of LV-SYNp vectors in 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-treated rat striata. The right striata were injected with IPLV- or IDLV-SYNp-eGFP vector 2 weeks before unilateral 6-OHDA lesioning at the same positions as for vector administration. Animal brains were harvested 5 months later. Representative serial striatal sections from (a) IPLV-eGFP-injected and (b) IDLV-eGFP-injected animals show both vector injection site and area of vector spread. (c) No eGFP expression in the noninjected left striatal hemisphere but (d) anterograde eGFP presence in the corresponding substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNpr; costained in red for TH+ cells) was detected. (e) An evaluation of eGFP levels indicated no significant difference in vector transduction efficiency between IPLVs and IDLVs. (f and g) Representative high-magnification images from IPLV- and IDLV-eGFP-injected striata, respectively, are shown. Cell-type identification by morphology and marker expression demonstrated that the majority of eGFP+ cells were neurons (NeuN+); no significant astrocyte (GFAP+) or microglia (Iba1+) transduction was observed. Nuclei were stained blue with DAPI; scale bars: (a–c) 2000 μm; (d) 500 μm; (f and g) 100 μm (insets, 20 μm). Data in (e) were analyzed for statistical significance by two-tailed Student t test; error bars represent the SEM; n = 3 per group.

IGF-1 protective effects on rat primary cortical neuronal cultures

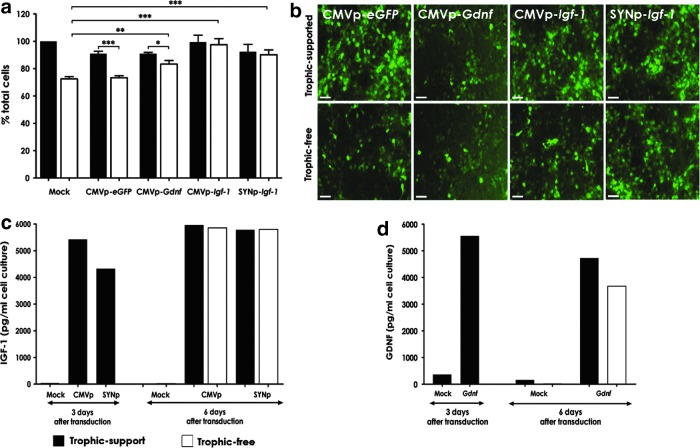

After the confirmation of LV transduction efficiency and cell-type specificity (through eGFP expression in vitro and in vivo), we investigated the neuroprotective effect of IGF-1, using trophic factor withdrawal on primary rat cortical neuronal cultures. Because neurons have been reported as the main source of brain IGF-1,34 IDLVs expressing Igf-1 were driven by SYNp or CMVp to enhance Igf-1 expression. IDLVs carrying either CMVp-eGFP, CMVp-Gdnf-IRES-eGFP, SFFVp-eGFP-CMVp-Igf-1, or SFFVp-eGFP-SYNp-Igf-1 were added to cell cultures 24 hr after cell plating. The culture medium was replaced with normal cortical neuronal medium (trophic factor-supported cultures) or with medium from which supplements had been withdrawn (trophic factor-free cultures), 3 days after vector transduction. Cell viability was determined by MTT assay 3 days afterward and the results are shown in Fig. 4a. Transduction efficiency was assessed by eGFP fluorescence (Fig. 4b). Survival of cells in trophic factor-supported cultures was not significantly different between groups (p = 0.08). However, withdrawal of exogenous trophic factors led to the death of 20–30% of total cells in the nontransduced group (mock) and the CMVp-eGFP-transduced group (negative control). Such reduction was significantly different (p < 0.001) when compared with IDLV-Igf-1 and -Gdnf groups. Indeed, transduction with IDLV-Gdnf vectors rescued more than 90% cells in trophic factor-free cultures, although a significant difference (p = 0.02) in the survival of Gdnf-treated cells between trophic-supported and trophic factor-free cultures was still observed. LV-Igf-1 vector transduction provided complete protection, with similar cell survival regardless of trophic support in the cultures transduced with either CMVp-Igf-1 (p = 0.77) or SYNp-Igf-1 (p = 0.75) vector. Moreover, IDLVs expressing Igf-1 displayed similar transduction efficiency (p = 0.23) regardless of promoter type (CMVp or SYNp) (Fig. 4a–c).

Figure 4.

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 protection of rat primary embryonic cortical neurons. Neuronal cultures were transduced with IDLVs expressing Igf-1, Gdnf (positive control), or eGFP (negative control) 1 day after cell plating. Trophic factor withdrawal was applied 3 days posttransduction and cells were cultured for an additional 3 days. (a) Results from an MTT assay indicated that cell survival in trophic-supported cultures was not significantly different between groups, whereas in trophic-free cultures, IDLV-Igf-1 or IDLV-Gdnf displayed enhanced survival. Data are shown as percentages compared with the mock (nontransduced group) in trophic-support cultures. Statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett's post hoc test; error bars represent the SEM; n = 3. (b) Representative images illustrate efficient transduction of the cortical cell cultures through eGFP expression; scale bars, 50 μm. (c and d) ELISA results presenting levels of (c) IGF-1 and (d) glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) produced in transduced cortical neuronal cultures on days 3 and 6 after IDLV transduction. Samples were run in duplicate with n = 2. Solid columns, trophic-support groups; open columns, trophic-free groups. Error bars represent the SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Using commercially available ELISA kits, we measured the level of IGF-1 (Fig. 4c) and GDNF (Fig. 4d) produced in the transduced neuronal cultures. Transgenic production of IGF-1 was efficient and independent of trophic support and vector promoter (4.3–5.5 ng/ml on day 3, and 5.8–6.0 ng/ml on day 6). GDNF production was similarly efficient at 3 days posttransduction (∼5.6 ng/ml), but seemed slightly reduced on day 6 (∼4.7 ng/ml) and even lower in the absence of trophic support (∼3.7 ng/ml), matching the culture viability as shown by MTT assay (Fig. 4a).

Our results indicated efficient transgene expression from IDLVs in transduced primary neuronal cultures. A clear neuroprotective effect of IGF-1 on cultured neurons was observed, more potent than that observed with GDNF in parallel experiments, encouraging further testing of in vivo IGF-1 neuroprotection.

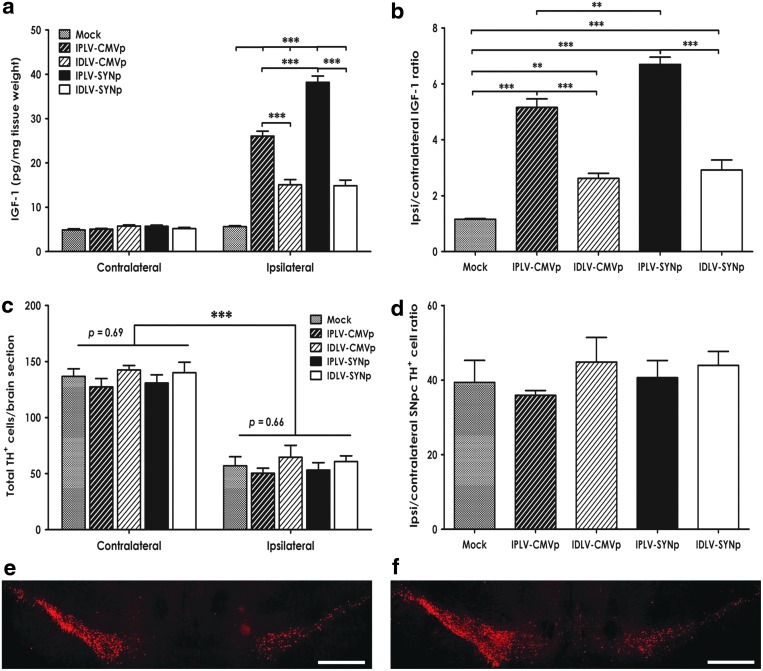

Lack of IGF-1 protective effects on dopaminergic neurons of 6-OHDA-lesioned rats

We subsequently investigated LV-Igf-1 transduction in a 6-OHDA rat model of PD. IPLVs or IDLVs expressing Igf-1 were injected into the right striatum of rats, which then received a partial unilateral lesion with 6-OHDA 2 weeks after vector transduction. The amount of IGF-1 produced in the striatum, determined by ELISA 6 weeks after vector administration (Fig. 5a), showed no significant differences in the levels of IGF-1 in the contralateral hemispheres between groups (p =0.92). As expected, the levels in LV-Igf-1-injected hemispheres were significantly higher than in contralateral hemispheres and mock-treated animals, regardless of vector integration proficiency or promoter type (p < 0.001). Differences in efficacy between vectors were noticed, with IPLVs being more efficient than IDLVs, and SYNp being particularly efficient in the IPLV configuration. IPLVs boosted IGF-1 levels 5- to 7-fold, whereas IDLVs provided about 2.5-fold increases (Fig. 5a and b).

Figure 5.

Igf-1 expression in rat striata does not mediate protective effects on substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) dopaminergic neurons. CMVp-Igf-1 and SYNp-Igf-1 vectors, either IPLVs or IDLVs, were injected into the right striatum of rats 2 weeks before 6-OHDA lesioning; mock-treated animals received 0.9% saline. (a) Quantification of IGF-1 production showing no significant difference in contralateral hemispheres between groups; in contrast, significant vector-mediated IGF-1 production was observed in the ipsilateral hemispheres. (b) Ratios of IGF-1 levels between ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. Data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test; error bars represent the SEM; n = 5 per group. (c) Total TH+ cell numbers (per brain section) in the SNpc were counted 6 weeks after vector transduction. (d) Ratio of remaining SNpc TH+ cells between ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. The lesion caused a reduction to about 40–50% in all groups, with no significant difference in TH+ cell survival observed between Igf-1-treated and mock-treated groups. Statistical analysis by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni's post hoc test; error bars represent the SEM; n = 5 per group. (e and f) Representative images of SN sections demonstrate the depletion of TH+ cells in the ipsilateral hemisphere (right) compared with the contralateral hemisphere (left), with no difference between (e) mock and (f) Igf-1-treated groups; scale bars, 500 μm. Error bars represent the SEM; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

We further examined the potential neuroprotective effects of IGF-1 on dopaminergic neurons by quantifying the total number of dopaminergic (TH+) cells remaining in the SNpc after 6-OHDA lesioning. After intrastriatal injection of 6-OHDA, a depletion of 50–60% of dopaminergic cell bodies was detected in the ipsilateral hemispheres of mock-treated animals, as expected (Fig. 5c). The increased levels of IGF-1 did not appear to affect dopaminergic cell survival, as there was no significant difference in the number of TH+ cells remaining in the ipsilateral hemisphere between Igf-1-treated and mock-treated groups (p = 0.66; Fig. 5c). Furthermore, the ratios of remaining TH+ cell number in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres were not statistically different between groups (p = 0.69; Fig. 5d). Illustrative images are shown in Fig. 5e and f.

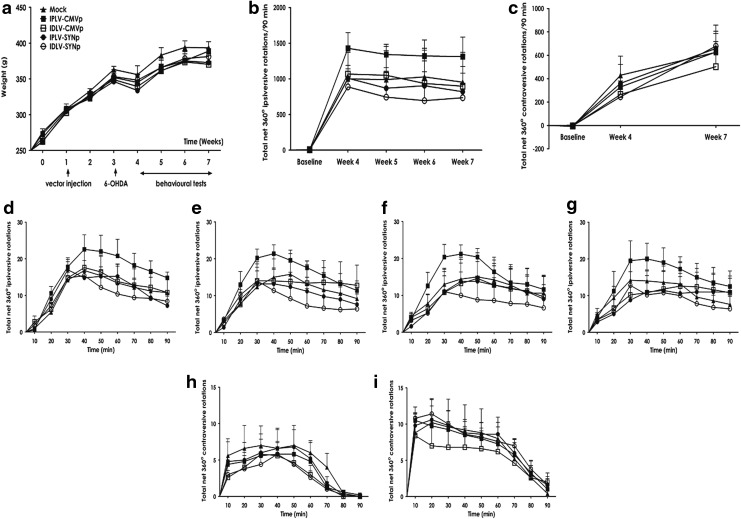

The potential of IGF-1 exerting beneficial behavioral effects in PD rats was also examined. Figure 6a shows a weight chart and the experimental schedule for this behavioral experiment, in which amphetamine- or apomorphine-induced rotations were scored. Animals gained weight as expected, with a transient reduction after 6-OHDA lesioning and no significant differences between groups. Net rotational asymmetry scores induced by amphetamine or apomorphine are summarized in Fig. 6b and c, respectively. There was no significant difference between groups in response to either amphetamine (p = 0.20) or apomorphine (p = 0.88). We further analyzed whether small differences might occur during the tests by comparing the number of rotations between groups at 10-min intervals. Neither amphetamine (Fig. 6d–g) nor apomorphine (Fig. 6h and i) mediated any significant difference. These in vivo results did not succeed in showing an effect of transgenic IGF-1 on dopaminergic neuron survival or behavioral recovery of 6-OHDA-lesioned rats, despite increased levels of IGF-1.

Figure 6.

Drug-induced rotational behavior tests. (a) Experimental design and weight of animals are shown. Animals had normal weight gain, with no significant difference between groups, except for a reduction in the week after 6-OHDA lesioning. (b and c) Summaries of net rotational asymmetry induced by (b) amphetamine or (c) apomorphine. After 30 min of acclimation (baseline), rats were injected with the corresponding drug. Net 360-degree rotations were scored for 90 min. For amphetamine, ipsilateral turns were given positive values and contralateral turns were counted as negative values; for apomorphine, contralateral turns were scored as positive and ipsilateral as negative. No significant behavioral changes between animal groups were detected in either test. (d–i) The number of rotations per 10-minute interval was scored. (d–g) Amphetamine-induced rotational tests at weeks 4, 5, 6, and 7, respectively; (h and i) apomorphine-induced rotational tests at weeks 4 and 7. No significant difference between groups was observed. Statistical analysis by two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni's post hoc test; error bars represent the SEM; n = 5 per group.

Discussion

LVs can transduce both dividing and nondividing CNS cells, with stable long-term expression of the transgene.39 The development of IDLVs offers significantly reduced risk of insertional mutagenesis while maintaining similar transduction efficiency to the classical IPLVs in a range of cell types.28,29 We have already demonstrated neuroprotection mediated by IDLV-hGDNF in the 6-OHDA rodent model of PD,30 supporting the feasibility of the use of IDLVs for Igf-1 delivery in the present study. Our work demonstrates that (1) LV-SYNp vectors provided efficient, long-lived, and neuron-specific expression of transgene (through eGFP expression), with IDLVs as efficient as IPLVs; (2) delivery of IDLV-Igf-1 vectors to primary cortical neuronal cells in vitro provided complete neuroprotection; and (3) LV-mediated Igf-1 expression in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats, however, did not improve survival of dopaminergic cells or behavior of treated animals.

For many years PD was considered a pure motor disorder with symptoms attributed to the loss of SNpc dopaminergic neurons and subsequent depletion of striatal dopamine. However, studies have indicated that the impairment affects other areas of the brain, leading to a variety of nonmotor symptoms.40 One such symptom is cognitive dysfunction, occurring in one-third of patients with PD.41 Although the underlying pathology has not been elucidated, impaired pathways connecting the basal ganglia and the frontal cortex, which may subsequently cause a degeneration of cortical neurons, have been suggested to contribute to this decline.40 IGF-1, with its mitogenic properties exerted through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway, improved survival of rat cortical neurons.42,43 Our in vitro data confirm the protective effects of IGF-1 on these neurons, although we obtained effective protection at much lower levels of IGF-1 and by transduction with IDLVs rather than direct administration of IGF-1 protein.

In normal CNS tissue, IGF-1 is secreted by neurons,34 unlike other neurotrophic factors produced by glia, and acts on nearby IGF-1 receptors in an autocrine manner. The use of neuronal-specific promoters, such as SYNp, to drive Igf-1 expression is therefore rational.31 Indeed, SYNp has been extensively used to target expression of transgenes to neurons in vitro and in vivo.31,44 As shown, IPLV- and IDLV-SYNp-eGFP vectors transduced predominantly neurons in both primary cell cultures and PD rat striata. Importantly, the in vivo data, consistent with other studies,44,45 demonstrated that striatal administration of vectors driven by SYNp led to eGFP detection in the SN, possibly due to anterograde axonal trafficking. At present, it is unclear whether the vectors or transgene-induced proteins are transported. However, an involvement of endocytosis likely explains the transsynaptic transfer from neuron to neuron.46 This appears as an advantage in PD therapy because a transgene can be administered into the striatum but provide therapeutic effects to both the striatum and the SN. Technically, intrastriatal injection of vectors is simpler and safer than intranigral injection47 although a possible higher dose (volume) of vectors is required for intrastriatal injection.

The most likely explanation for the failure of transgenic Igf-1 to mediate in vivo neuroprotection in our study is the insufficient levels of IGF-1 achieved. IGF-1 was previously used at 30–150 ng/ml in embryonic mesencephalic neuronal cultures,8,48 whereas we obtained an ∼5-ng/ml concentration of IGF-1 by transgenic expression in vitro, but still achieved complete neuroprotection. However, in vivo neuroprotection in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats has been shown with continuous intracerebroventricular IGF-1 infusion for 1 week at 100 μg/ml (10 μg in total),21 which is many orders of magnitude higher than the IGF-1 concentration of 15–35 pg/mg obtained in the current study. Ebert and colleagues49 have previously reported the protective effects of IGF-1 on 6-OHDA-lesioned rats, which were achieved after striatal transplantation of neural progenitor cells expressing LV-IGF-1. The authors did not show at which levels IGF-1 provided such protection, and it could not be ruled out that other factors provided by the progenitor cells were involved. Indeed, in some systems progenitor cells can improve both cell survival and animal behavior in PD models against both 6-OHDA and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) toxicity.50,51 It is also noteworthy that to obtain similar protection on dopaminergic cell survival, previous investigators have used purified IGF-1 at concentrations about 30 times higher than that of GDNF.8,52 This is probably necessary because the half-life of IGF-1 is less than 10 min whereas GDNF can last for 6–8 days.53,54 Because the doses of Igf-1-expressing vectors used in this study are similar to those used previously for delivery of other neurotrophic factor (i.e., GDNF) with demonstrated therapeutic benefits,30 insufficient in vivo expression of Igf-1 as presented here is an obvious challenge for the application of IGF-1 gene therapy in PD. A vector dosing study should be carried out to determine the doses of Igf-1-expressing vectors that can mediate neuroprotection. The use of more concentrated vector stocks, stronger transcription regulation sequences, codon optimization of the transgene, and stabilization of the transgenic IGF-1 protein should be explored to develop an Igf-1 vector of demonstrated preclinical efficacy.

In summary, our studies provide evidence for efficient transgenic delivery by IDLVs in PD and support their use in the CNS as a safer delivery system. Our data, moreover, confirm neuroprotection by IGF-1 on cultured cortical neurons, resulting from efficient IDLV-Igf-1 delivery. However, IGF-1-mediated protection through transgenic Igf-1 expression was unsuccessful in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Further studies are required to develop an effective Igf-1 delivery system and to ascertain the benefit of IGF-1 gene therapy for PD treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the EU FP7 program (project NEUGENE: grant agreement n. 222925), Royal Holloway, University of London, and University of Medicine and Pharmacy at Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam for financial support. Author contributions: R.J.Y.-M. conceived and directed the project; R.J.Y.-M. and M.B. designed the experiments; N.-B.L.-N. and M.B. performed all experiments; N.-B.L.-N., M.B., and R.J.Y.-M. analyzed the data; N.-B.L.-N., M.B., and R.J.Y.-M. wrote the manuscript.

Author Disclosure

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Chen Q, He Y, and Yang K. Gene therapy for Parkinson's disease: progress and challenges. Curr Gene Ther 2005;5:71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gill SS, Patel NK, Hotton GR, et al. Direct brain infusion of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in Parkinson disease. Nat Med 2003;9:589–595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marks WJ, Jr., Ostrem JL, Verhagen L, et al. Safety and tolerability of intraputaminal delivery of CERE-120 (adeno-associated virus serotype 2-neurturin) to patients with idiopathic Parkinson's disease: an open-label, phase I trial. Lancet Neurol 2008;7:400–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun M, Kong L, Wang X, et al. Comparison of the capability of GDNF, BDNF, or both, to protect nigrostriatal neurons in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Brain Res 2005;1052:119–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindholm P, Voutilainen MH, Lauren J, et al. Novel neurotrophic factor CDNF protects and rescues midbrain dopamine neurons in vivo. Nature 2007;448:73–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voutilainen MH, Back S, Porsti E, et al. Mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor is neurorestorative in rat model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci 2009;29:9651–9659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang AE, Gill S, Patel NK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of intraputamenal glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor infusion in Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol 2006;59:459–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knusel B, Michel PP, Schwaber JS, et al. Selective and nonselective stimulation of central cholinergic and dopaminergic development in vitro by nerve growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, epidermal growth factor, insulin and the insulin-like growth factors I and II. J Neurosci 1990;10:558–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan C, and Xu Q. Roles of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding proteins in regulating IGF actions. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2005;142:44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandez S, Fernandez AM, Lopez-Lopez C, et al. Emerging roles of insulin-like growth factor-I in the adult brain. Growth Horm IGF Res 2007;17:89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russo VC, Gluckman PD, Feldman EL, et al. The insulin-like growth factor system and its pleiotropic functions in brain. Endocr Rev 2005;26:916–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandez AM, and Torres-Aleman I. The many faces of insulin-like peptide signalling in the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci 2012;13:225–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Avila-Gomez IC, Velez-Pardo C, and Jimenez-Del-Rio M. Effects of insulin-like growth factor-1 on rotenone-induced apoptosis in human lymphocyte cells. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2010;106:53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun X, Huang L, Zhang M, et al. Insulin like growth factor-1 prevents 1-methyl-4-phenylphyridinium-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells through activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β. Toxicology 2010;271:5–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Yang HJ, Xia YY, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 protects human neuroblastoma cells SH-EP1 against MPP+-induced apoptosis by AKT/GSK-3β/JNK signaling. Apoptosis 2010;15:1470–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Landi F, Capoluongo E, Russo A, et al. Free insulin-like growth factor-I and cognitive function in older persons living in community. Growth Horm IGF Res 2007;17:58–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong M, Dong M, and de la Monte SM. Brain insulin-like growth factor and neurotrophin resistance in Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies: potential role of manganese neurotoxicity. J Alzheimers Dis 2009;16:585–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan J, Krishnamurthi R, Waldvogel HJ, et al. N-terminal tripeptide of IGF-1 (GPE) prevents the loss of TH positive neurons after 6-OHDA induced nigral lesion in rats. Brain Res 2000;859:286–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Offen D, Shtaif B, Hadad D, et al. Protective effect of insulin-like-growth-factor-1 against dopamine-induced neurotoxicity in human and rodent neuronal cultures: possible implications for Parkinson's disease. Neurosci Lett 2001;316:129–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quesada A, Lee BY, and Micevych PE. PI3 kinase/Akt activation mediates estrogen and IGF-1 nigral DA neuronal neuroprotection against a unilateral rat model of Parkinson's disease. Dev Neurobiol 2008;68:632–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quesada A, and Micevych PE. Estrogen interacts with the IGF-1 system to protect nigrostriatal dopamine and maintain motoric behavior after 6-hydroxdopamine lesions. J Neurosci Res 2004;75:107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salvatore MF, Ai Y, Fischer B, et al. Point source concentration of GDNF may explain failure of phase II clinical trial. Exp Neurol 2006;202:497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dowd E, Monville C, Torres EM, et al. Lentivector-mediated delivery of GDNF protects complex motor functions relevant to human Parkinsonism in a rat lesion model. Eur J Neurosci 2005;22:2587–2595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emborg ME, Moirano J, Raschke J, et al. Response of aged parkinsonian monkeys to in vivo gene transfer of GDNF. Neurobiol Dis 2009;36:303–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Georgievska B, Kirik D, and Bjorklund A. Overexpression of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor using a lentiviral vector induces time- and dose-dependent downregulation of tyrosine hydroxylase in the intact nigrostriatal dopamine system. J Neurosci 2004;24:6437–6445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kordower JH, Emborg ME, Bloch J, et al. Neurodegeneration prevented by lentiviral vector delivery of GDNF in primate models of Parkinson's disease. Science 2000;290:767–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palfi S, Leventhal L, Chu Y, et al. Lentivirally delivered glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor increases the number of striatal dopaminergic neurons in primate models of nigrostriatal degeneration. J Neurosci 2002;22:4942–4954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yáñez-Muñoz RJ, Balaggan KS, MacNeil A, et al. Effective gene therapy with nonintegrating lentiviral vectors. Nat Med 2006;12:348–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wanisch K, and Yáñez-Muñoz RJ. Integration-deficient lentiviral vectors: a slow coming of age. Mol Ther 2009;17:1316–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu-Nguyen NB, Broadstock M, Schliesser MG, et al. Transgenic expression of human glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor from integration-deficient lentiviral vectors is neuroprotective in a rodent model of Parkinson's disease. Hum Gene Ther 2014;25:631–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hioki H, Kameda H, Nakamura H, et al. Efficient gene transduction of neurons by lentivirus with enhanced neuron-specific promoters. Gene Ther 2007;14:872–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jakobsson J, Ericson C, Jansson M, et al. Targeted transgene expression in rat brain using lentiviral vectors. J Neurosci Res 2003;73:876–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li M, Husic N, Lin Y, et al. Optimal promoter usage for lentiviral vector-mediated transduction of cultured central nervous system cells. J Neurosci Methods 2010;189:56–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mashayekhi F, Mirzajani E, Naji M, et al. Expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Parkinson's disease. J Clin Neurosci 2010;17:623–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pruszak J, Just L, Isacson O, et al. , Isolation and culture of ventral mesencephalic precursor cells and dopaminergic neurons from rodent brains. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol 2009;Chapter 2:Unit 2D.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takeshima T, Shimoda K, Sauve Y, et al. Astrocyte-dependent and -independent phases of the development and survival of rat embryonic day 14 mesencephalic, dopaminergic neurons in culture. Neuroscience 1994;60:809–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulos S, Meloni BP, Arthur PG, et al. Assessment of CMV, RSV and SYN1 promoters and the woodchuck post-transcriptional regulatory element in adenovirus vectors for transgene expression in cortical neuronal cultures. Brain Res 2006;1102:27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paxinos G, and Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 6th ed. Elsevier/Academic Press, New York: 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartus RT, Herzog CD, Bishop K, et al. Issues regarding gene therapy products for Parkinson's disease: the development of CERE-120 (AAV-NTN) as one reference point. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2007;13 Suppl 3:S469–S477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chaudhuri KR, Healy DG, and Schapira AH. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease: diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindgren HS, and Dunnett SB. Cognitive dysfunction and depression in Parkinson's disease: what can be learned from rodent models? Eur J Neurosci 2012;35:1894–1907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hodge RD, D'Ercole AJ, and O'Kusky JR. Insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) inhibits neuronal apoptosis in the developing cerebral cortex in vivo. Int J Dev Neurosci 2007;25:233–241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mairet-Coello G, Tury A, and DiCicco-Bloom E. Insulin-like growth factor-1 promotes G1/S cell cycle progression through bidirectional regulation of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in developing rat cerebral cortex. J Neurosci 2009;29:775–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Drinkut A, Tereshchenko Y, Schulz JB, et al. Efficient gene therapy for Parkinson's disease using astrocytes as hosts for localized neurotrophic factor delivery. Mol Ther 2012;20:534–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson RM, Kells AP, Rosenbluth KH, et al. Interventional MRI-guided putaminal delivery of AAV2-GDNF for a planned clinical trial in Parkinson's disease. Mol Ther 2011;19:1048–1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desplats P, Lee HJ, Bae EJ, et al. Inclusion formation and neuronal cell death through neuron-to-neuron transmission of α-synuclein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:13010–13015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manfredsson FP, Tumer N, Erdos B, et al. Nigrostriatal rAAV-mediated GDNF overexpression induces robust weight loss in a rat model of age-related obesity. Mol Ther 2009;17:980–991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zawada WM, Kirschman DL, Cohen JJ, et al. Growth factors rescue embryonic dopamine neurons from programmed cell death. Exp Neurol 1996;140:60–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ebert AD, Beres AJ, Barber AE, et al. Human neural progenitor cells over-expressing IGF-1 protect dopamine neurons and restore function in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Exp Neurol 2008;209:213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Redmond DE, Jr., Bjugstad KB, Teng YD, et al. Behavioral improvement in a primate Parkinson's model is associated with multiple homeostatic effects of human neural stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:12175–12180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sadan O, Shemesh N, Cohen Y, et al. Adult neurotrophic factor-secreting stem cells: a potential novel therapy for neurodegenerative diseases. Isr Med Assoc J 2009;11:201–204 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin LF, Doherty DH, Lile JD, et al. GDNF: a glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor for midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Science 1993;260:1130–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohick WS, and Clemmons DR. The insulin-like growth factors. Annu Rev Physiol 1993;55:131–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Granholm AC, Reyland M, Albeck D, et al. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor is essential for postnatal survival of midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 2000;20:3182–3190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.