Abstract

Plant pathogen infection is a critical factor for the persistence of Salmonella enterica on plants. We investigated the mechanisms responsible for the persistence of S. enterica on diseased tomato plants by using four diverse bacterial spot Xanthomonas species that differ in disease severities. Xanthomonas euvesicatoria and X. gardneri infection fostered S. enterica growth, while X. perforans infection did not induce growth but supported the persistence of S. enterica. X. vesicatoria-infected leaves harbored S. enterica populations similar to those on healthy leaves. Growth of S. enterica was associated with extensive water-soaking and necrosis in X. euvesicatoria- and X. gardneri-infected plants. The contribution of water-soaking to the growth of S. enterica was corroborated by an increased growth of populations on water-saturated leaves in the absence of a plant pathogen. S. enterica aggregates were observed with bacterial spot lesions caused by either X. euvesicatoria or X. vesicatoria; however, more S. enterica aggregates formed on X. euvesicatoria-infected leaves as a result of larger lesion sizes per leaf area and extensive water-soaking. Sparsely distributed lesions caused by X. vesicatoria infection do not support the overall growth of S. enterica or aggregates in areas without lesions or water-soaking; S. enterica was observed as single cells and not aggregates. Thus, pathogen-induced water-soaking and necrosis allow S. enterica to replicate and proliferate on tomato leaves. The finding that the pathogen-induced virulence phenotype affects the fate of S. enterica populations in diseased plants suggests that targeting of plant pathogen disease is important in controlling S. enterica populations on plants.

INTRODUCTION

The phyllosphere, the above-ground part of plants, is a physically diverse habitat with a complex microbiome containing phytopathogens, epiphytes, saprophytes, and opportunistic pathogens as residents. Periodically included among these microbes are human enteric bacterial pathogens. Recent recurrent salmonellosis outbreaks associated with the consumption of contaminated fresh produce indicate that human pathogens use plants as vectors to move between omnivorous hosts, including humans (1). Habitation of the phyllosphere by Salmonella enterica involves active colonization of plant tissue (2, 3). Despite the common occurrence of S. enterica in the phyllosphere, little is known about the effect of resident microbes on and the role of the host in S. enterica colonization and survival.

As a symbiont, S. enterica is nonpathogenic on plants, and populations normally decline in the phyllosphere, indicating that it is less fit than common phyllosphere inhabitants (3). Fundamental knowledge of how different ecological and biological factors influence the colonization efficiency of these human pathogens is lacking. Upon immigration to the leaf surface, attachment, survival, and/or growth in the phyllosphere determines the fate of human enteric bacterial pathogens in and on plants and influences their ability to cause foodborne infections in humans. The plant host and phyllosphere microbes influence the population sizes of bacterial plant pathogens as well as human enteric bacterial pathogens. Plant pathogens and epiphytes respond to low nutrient availability in the phyllosphere by forming alliances, i.e., interactions with other leaf colonizers, resulting in enhanced fitness and ecological success (4). The presence of common epiphytic bacteria such as Pseudomonas syringae and Erwinia herbicola in the phyllosphere has been shown to protect S. enterica from stresses such as exposure to desiccation (5). Such an interaction with resident epiphytic bacteria was shown to be one of the factors contributing to the increased fitness of S. enterica on plants. During initial immigration events, pathogens and other phyllosphere colonizers that land at protected sites, such as veins, trichomes, and stomata, manage to avoid some stresses. S. enterica has been shown to preferentially colonize trichomes (6) and has been found near stomata (7), which might offer them sites for protection against stresses as well as make resources available.

The presence of plant pathogens in the phyllosphere has been suggested to be a human illness risk factor due to the increased survival of S. enterica (7, 8–12). Plant pathogens carry a set of virulence factors that inhibit the plant innate immune responses so that bacteria can grow on and colonize the phyllosphere. Recently, we discovered that Xanthomonas perforans influences S. enterica survival in the tomato phyllosphere (7). Via the type 3 secretion system, virulent X. perforans modifies the phyllosphere, resulting in susceptibility, which in turn increases the persistence of S. enterica on infected leaves. In contrast, avirulent X. perforans initiates effector-triggered immunity and thus activates plant defenses, which result in reduced survival of S. enterica (7). The main objective of this study was to identify the mechanism for how plant disease susceptibility contributes to the persistence of S. enterica on bacterial spot-infected leaves. We hypothesize that the host response to the plant pathogen during disease development changes the phyllosphere and influences S. enterica colonization. To dissect changes in the host, we initially examined the effect on S. enterica populations of a single disease, bacterial spot of tomato, caused by four distinct Xanthomonas species, which show differences in symptoms and extent of tissue modification (13). Once we established differential responses of S. enterica to individual Xanthomonas species, we examined the role of host susceptibility with a single Xanthomonas species. We also analyzed the survival of S. enterica on water-saturated leaves in the absence of a plant pathogen and examined leaf colonization by the human pathogen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and plant material.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Both S. enterica strains are clinical isolates from salmonellosis outbreaks caused by the consumption of contaminated raw tomatoes. These S. enterica serovars are commonly associated with outbreaks originating from produce (S. enterica serovar Baildon on tomato in 2010 and 1999 and S. enterica serovar Enteritidis on tomato in 2012 and 2005, pine nuts in 2011, and sprouts in 2011; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [http://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/outbreaks.html]). Each S. enterica strain was transformed with a stable vector, pKT-Kan (14), containing green fluorescent protein (GFP) (Table 1) to select for kanamycin-resistant S. enterica in population dynamics studies. Pathogenic Xanthomonas strains were cultured on nutrient agar (NA) (Difco), and S. enterica strains were cultured on Luria-Bertani agar (15) amended with 50 μg/ml kanamycin (LB-Kan). For confocal microscopy experiments, GFP-labeled Xanthomonas euvesicatoria and X. vesicatoria were obtained by triparental mating using plasmid pUFZ75-gfp (16) constitutively expressing GFP. Each S. enterica strain was transformed with a stable vector, pWM1009, containing cyan fluorescent protein (CFP) (17).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or referencea |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. enterica serovar Enteritidis 05x-02123/pKT-Kan | Clinical isolate, tomato outbreak strain from 2005; Kmr | CSHL, Berkeley |

| S. enterica serovar Baildon 99A 23/pKT-Kan | Clinical isolate, tomato outbreak strain from 1999; Kmr | CSHL, Berkeley |

| S. enterica serovar Enteritidis 05x-02123/pWM1009 | CFP constitutive; Kmr | 8 |

| S. enterica serovar Baildon 99A 23/pWM1009 | CFP constitutive; Kmr | 8 |

| X. euvesicatoria 85-10 | Virulent on tomato cv. NIL216 and genotype Pearson | Jones laboratory collection |

| X. vesicatoria 1111 | Virulent on tomato cv. NIL216 | Jones laboratory collection |

| X. perforans 2010 | Virulent on tomato cv. NIL216 | Jones laboratory collection |

| X. gardneri 444 | Virulent on tomato cv. NIL216 | Jones laboratory collection |

| X. euvesicatoria 85-10/pUFZ75 | Transconjugant GFP constitutive; Kmr | This study |

| X. vesicatoria 1111/pUFZ75 | Transconjugant GFP constitutive; Kmr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pKT-Kan | GFP constitutive; Kmr | 15 |

| pUFZ75 | GFP constitutive; pUFR034 ΔlacZΩ[(T1)4-Ptac-gfp-T1]; Kmr | 17 |

| pWM1009 | pMW10 ΔlacZΩ[(T1)4-Pc-cfp-T1]; Kmr | 18 |

CSHL, California State Health Laboratory.

Tomato cv. NIL216 was used in the initial plant experiments, including those with xanthomonad saprophytes. Tomato genotypes Pearson (wild type) and Never-ripe (ethylene-insensitive mutant) (18) were used to dissect the role of tissue necrosis in supporting or enhancing S. enterica populations. Tomatoes of all genotypes were grown in a greenhouse at 26°C/16°C with a 12-h-light/12-h-dark cycle.

In planta population studies.

For plant inoculum preparations in all experiments, cultures of Xanthomonas spp. and S. enterica grown overnight were resuspended in sterile tap water and adjusted to optical densities (600 nm) of 0.3 for Xanthomonas and 0.2 for S. enterica, i.e., to a concentration of ∼108 CFU/ml for both species. S. enterica serovars Enteritidis and Baildon, both tomato outbreak strains, were combined at a 1:1 ratio prior to inoculum dilution, and this cocktail was used for all experiments. Five-week-old tomato cv. NIL216 plants were inoculated with S. enterica alone or in combination with X. euvesicatoria, X. vesicatoria, X. perforans, and X. gardneri, with three replicates for each treatment. For experiments with the Pearson and Never-ripe genotypes, 5-week-old plants were inoculated with X. euvesicatoria and S. enterica or S. enterica alone. Inoculations were performed by dipping the plants for 30 s in a sterile-tap-water suspension with a 1:1 ratio of the Xanthomonas strain (106 CFU/ml) and the S. enterica cocktail (106 CFU/ml) or the S. enterica cocktail alone (106 CFU/ml) amended with 0.025% (vol/vol) Silwet 77. The initial inoculum along with day 0 samples were plated onto NA (Difco) for Xanthomonas and LB-Kan for S. enterica to confirm a 1:1 ratio of Xanthomonas and S. enterica concentrations, respectively. Inoculated plants were kept in a growth chamber at 25°C with a 12-h-light/12-h-dark cycle with 95% humidity for 2 days postinoculation (dpi). Thereafter, plants were kept at low humidity (10 to 20%) for 12 h in light and at high humidity (>90%) for 12 h in the dark for the remainder of the experiment. Experiments were repeated at least three times.

Bacterial populations were measured every 48 h by using each of three leaflets from middle leaves from three plants per treatment. In previous work, we found that S. enterica populations in the presence or absence of X. perforans were similar on old and middle leaves and that middle leaves showed consistent bacterial spot symptom development (7). Old leaves displayed significant variation among leaves in symptom development; thus, in this study, we assayed only middle leaves, where we sampled three leaflets at each time point. A 2-cm2 area of leaf tissue was removed from each leaflet with a sterile cork borer. By using sterile forceps, two leaf disks were then placed into a sterile tube containing 1 ml sterile tap water and homogenized with a microDremel tool (Dremel, PA). Standard 10-fold dilution plating of the homogenate was carried out, and suspensions were plated onto NA and LB-Kan to estimate the sizes of Xanthomonas and S. enterica populations, respectively, from each sample. NA plates were incubated at 28°C for 3 days, and LB-Kan plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Colonies were counted, and bacterial populations were calculated as CFU per square centimeter of leaf area.

Electrolyte leakage.

Cell damage from infected leaf tissue was assessed by quantifying electrolyte leakage, as described previously (19). Leaf discs (3 cm2) were obtained from each of three leaflets from three plants per treatment per time point and placed into clean, dry tubes containing 3 ml of deionized water. The conductivity of the leaf disc was measured immediately after sampling (0-h time point) and again 1 h later. The value for the conductivity measurement at the 0-h time point served as a blank reading to take into account the tissue damage caused during sampling, a vacuum (−25 lb/in2) was applied to the samples for 1 min, and the tubes were placed at 28°C with constant shaking (170 rpm). After 1 h, tubes were vortexed briefly before conductivity measurements (measured in microsiemens [μS]) were taken. The change in conductivity (expressed as μS/hour) was used to calculate the mean electrolyte leakage and standard errors for each treatment. The experiment was repeated three times.

Effect of artificial water-soaking on S. enterica population dynamics.

The entire leaves of 5-week-old tomato cv. NIL216 plants were infiltrated with sterile tap water. Upon infiltration, plants were dip inoculated in 106 CFU/ml of the S. enterica inoculum for 30 s, as described above. A set of plants infiltrated with water, followed by dip inoculation with S. enterica, was kept bagged under high humidity. This ensured continuous water-soaking for the duration of the experiment. The other set, with the same treatment as the one described above, was kept unbagged and under low humidity (10 to 20%). This set of plants without water-soaking also served as a control to account for wounding damage during infiltration. The experiment was repeated at least three times.

Statistical analysis.

Values for bacterial populations were log transformed to obtain normal distributions for analyses. To determine differences in bacterial populations over time, a linear mixed model was used. The model incorporated the experiment as a random effect to account for correlation of counts in the same experiment, and an autoregressive correlation structure was applied to residuals to account for multiple measurements being taken on the same plants over time. The least-square means were used for all statistical analyses. To determine whether the average population of S. enterica differed between treatments or over time, Holm-Tukey multiple-comparison adjustments were used to test the potential effects of Xanthomonas infection or cocolonization of leaves on S. enterica populations with treatment and time (days postinoculation) as covariates. The same analysis was used to analyze Xanthomonas populations. Repetitions of the experiment were considered block factors. S. enterica populations (log CFU/square centimeter of leaf tissue) were compared between treatments at specific time points (dpi) by using an adjustment-of-comparisons test according to the Holm-Tukey method. Linear trends in bacterial counts were tested for post hoc by using linear contrasts. All statistical analyses were performed by using SAS software (SAS release 9.3; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Confocal laser scanning microscopy.

The effects of pathogen-induced water-soaking and plant disease symptoms on the colonization of S. enterica were evaluated by observing X. euvesicatoria-infected and X. vesicatoria-infected leaf samples and leaves inoculated with S. enterica alone by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) (TCS-SP5; Leica, Germany) at 12 dpi. Sample preparation and microscopy settings for excitation and emission filters for GFP and CFP signals were performed according to procedures described previously (7). The experiment was repeated at least three times.

RESULTS

Survival and growth of S. enterica are influenced by the degree of disease severity caused by bacterial spot xanthomonads.

To further examine the interactions between human enteric pathogens and phytobacterial pathogens in planta, we measured S. enterica and Xanthomonas populations over a 2-week period. Four Xanthomonas species cause a single disease, bacterial spot of tomato, with differential disease severities (13, 20). These four species cause various amounts and types of disease symptoms (15), which include brown-black necrotic lesions, coalesced lesions with a blighted appearance, and water-soaking. Examination of S. enterica populations on leaves infected with each Xanthomonas species would give us a better understanding of the effect of phytobacterial infection on S. enterica survival and growth on leaves. At 2 days postinoculation (dpi), S. enterica populations were similar among treatments. By as early as 8 dpi, sizes of S. enterica populations were different among treatments: X. euvesicatoria = X. gardneri > X. perforans ≥ X. vesicatoria = S. enterica alone (P < 0.05) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). S. enterica population sizes on leaves infected with X. euvesicatoria and X. gardneri increased over time (P = 0.02 for S. enterica populations on leaves infected with X. euvesicatoria and P = 0.001 for populations on leaves infected with X. gardneri, based on contrast for linear trends) (Fig. 1A). By 14 dpi, S. enterica populations were 50- to 75-fold larger on X. perforans-infected plants than on plants inoculated with S. enterica alone (Fig. 1A); however, net growth was not found for S. enterica on X. perforans-infected plants from days 2 to 14 postinoculation (P = 0.59, based on contrast for linear trends). In contrast, S. enterica populations on X. vesicatoria-infected plants declined over the 2-week period examined (P > 0.60, based on contrast for linear trends) (Fig. 1A) although with a slower decline than on plants inoculated with S. enterica alone. Xanthomonas populations were similar among X. euvesicatoria, X. gardneri, and X. perforans (Fig. 1B) over the duration of the experiment, even though the sizes of the S. enterica populations differed among these treatments (Fig. 1A).

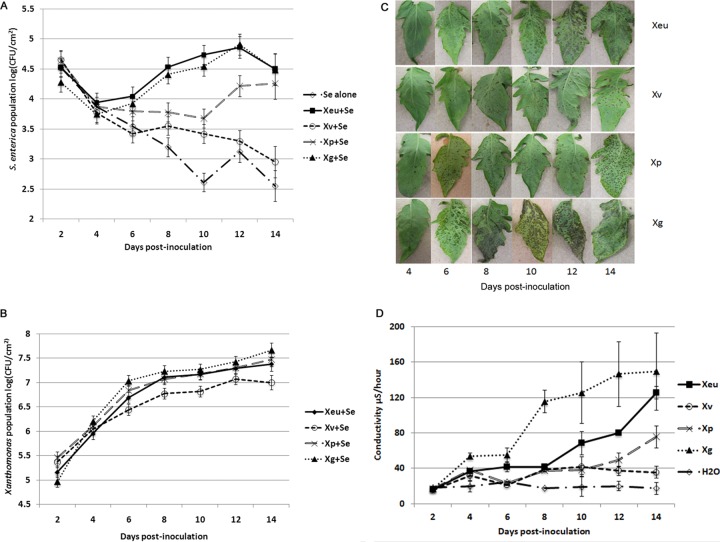

FIG 1.

S. enterica population growth is associated with extensive plant cell necrosis, as measured by electrolyte leakage on leaves of bacterial spot-infected tomato plants and disease symptomology. (A and B) Salmonella enterica (A) and Xanthomonas (B) population dynamics on tomato plants infected with different species of Xanthomonas. Tomato leaves were sampled every 2 days for 14 days postinoculation to determine the sizes of S. enterica and Xanthomonas populations (log CFU per square centimeter). Plants were dip inoculated with S. enterica (Se) and Xanthomonas euvesicatoria (Xeu), S. enterica and X. vesicatoria (Xv), S. enterica and X. perforans (Xp), S. enterica and X. gardneri (Xg), or S. enterica alone. The data represent results from seven independent experiments combined. The points represent least-square means, and the vertical bars are the standard errors calculated from the linear mixed model. (C) Xanthomonas species that cause bacterial spot of tomato show differences in disease severity on tomato cv. NIL216 plants. Disease symptoms begin with circular water-soaked lesions, which later develop into greasy dark-brown-to-black lesions. During later stages of disease development, primary lesions expand and form secondary lesions, which often coalesce and are due to extensive necrosis. Widespread tissue necrosis is seen with X. gardneri and X. euvesicatoria. Slower symptom development and less disease are seen with X. vesicatoria. (D) Electrolyte leakage, measured by conductance, from tomato leaves inoculated with different Xanthomonas species or sterile water alone. The conductance data (μS/hour at 28°C) are from a representative experiment, due to variation in disease development on leaves in different experimental sets. The points represent means of data from three measurements for three samples during a single experiment, and the vertical bars are the standard errors. The experiment was repeated three times.

Differences in disease severity were observed for four bacterial spot Xanthomonas species, as estimated visually based on symptom type and extent of symptom spread. Initial disease symptoms appeared by day 6 postinoculation. X. gardneri was the most aggressive among the four species, showing the most severe and extensive water-soaking and necrosis, followed by X. euvesicatoria and X. perforans (Fig. 1C). Disease development was slower, and plants exhibited the least severe symptoms when infected with X. vesicatoria. To quantify plant cell damage as a result of differential disease severities due to the different xanthomonads during disease development, an electrolyte leakage assay was performed. Electrolyte leakage is a quantitative measure of plant cell injury or death resulting from pathogen infection and, in turn, of disease severity (21). Electrolyte leakage (measured as conductance) (19) began to increase at between days 6 and 8 postinoculation in X. gardneri-infected leaves and at days 10 and 12 postinoculation for X. euvesicatoria- and X. perforans-infected leaves, respectively (Fig. 1D). In contrast, X. vesicatoria caused little cell damage during the 14-day experiment. These results support the conclusion that plant cell necrosis starts early in X. gardneri-infected leaves and is most extensive compared to infection with the other Xanthomonas species, followed by X. euvesicatoria and X. perforans. Furthermore, the growth and survival of S. enterica on infected leaves were associated with electrolyte leakage caused by X. gardneri, X. euvesicatoria, and X. perforans.

Pathogen-induced water-soaking is responsible for growth of S. enterica on bacterial spot-infected leaves of tomato.

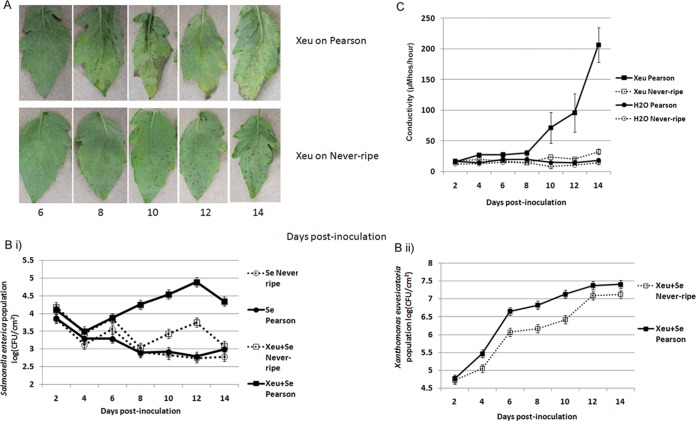

To independently confirm our supposition that S. enterica growth is independent of Xanthomonas populations but dependent on disease symptoms as a result of pathogen infection, we examined the role of the host in this interaction. We measured S. enterica populations on tomato plants of genotypes that were shown previously to support similar plant pathogen population levels with different degrees of host susceptibility (18). The Never-ripe genotype is an ethylene-insensitive mutant of the Pearson genotype (wild type). X. euvesicatoria infection of Pearson and Never-ripe plants causes primary bacterial spot lesions (circular brown lesions) by 6 dpi. However, only X. euvesicatoria-infected Pearson plants develop the secondary stages of disease, which include extensive water-soaking and merged chlorotic lesions with necrosis. In X. euvesicatoria-infected Never-ripe plants, primary lesions do not expand; thus, for the duration of our experiment, water-soaking was limited (Fig. 2A). X. euvesicatoria populations were 5-fold larger on Pearson than on Never-ripe plants at 6, 8, and 10 dpi (P = 0.001) (Fig. 2Bi); however, there was no significant difference in X. euvesicatoria populations at 12 and 14 dpi (P = 0.20) (Fig. 2Bii). Primary bacterial spot lesions appeared on plants of both genotypes at 6 dpi, at which point there was no significant difference between S. enterica populations on X. euvesicatoria-infected Pearson and Never-ripe plants (P = 1.00). Coalescing, secondary lesions leading to necrosis were observed on X. euvesicatoria-infected Pearson plants at 8 dpi but not on Never-ripe plants. At this time, S. enterica populations were 50-fold larger on X. euvesicatoria-infected Pearson plants than on X. euvesicatoria-infected Never-ripe plants or with S. enterica alone on plants of either genotype (P < 0.0001). S. enterica populations increased on X. euvesicatoria-infected Pearson leaves (P < 0.0001, based on contrast for linear trends), and by 14 dpi, these populations were 50- to 100-fold larger than populations with S. enterica alone. While S. enterica populations on X. euvesicatoria-infected Never-ripe plants were10-fold larger at 12 dpi than on plants without X. euvesicatoria infection, there was no significant difference in S. enterica populations with and without X. euvesicatoria on Never-ripe plants by 14 dpi (P = 0.46) (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). There was an overall decline in S. enterica populations on X. euvesicatoria-infected Never-ripe plants, as was observed for either genotype with S. enterica alone (P < 0.0001, based on contrast for linear trends). Conductivity measurements to quantify electrolyte leakage of plant cells showed increased conductivity in X. euvesicatoria-infected Pearson leaves, but no increase was found for X. euvesicatoria-infected Never-ripe plants compared to mock-inoculated Never-ripe or Pearson plants (Fig. 2C).

FIG 2.

Growth of Salmonella enterica on Xanthomonas euvesicatoria-infected plants is supported by pathogen-induced water-soaking. (A) Xanthomonas euvesicatoria shows differences in disease severity on tomato plants of two genotypes, Pearson and Never-ripe. Water-soaking appears on both Pearson and Never-ripe plants by day 6 postinoculation. Secondary lesion development, seen as coalescing primary lesions and extended necrotic water-soaked lesions, was observed on Pearson plants by day 8 postinoculation. Secondary lesions did not appear on Never-ripe plants for the duration of the experiment. (B) S. enterica populations (log CFU per square centimeter) (i) and X. euvesicatoria populations (log CFU per square centimeter) (ii) were enumerated every 2 days until day 14 postinoculation. (C) Electrolyte leakage was measured by using a conductivity meter every 2 days until day 14 postinoculation. Plants were dip inoculated with S. enterica and Xanthomonas euvesicatoria or S. enterica alone. The S. enterica and X. euvesicatoria population data represent results from four independent experiments combined. The points represent least-square means, and the vertical bars are the standard errors calculated from the model. The conductance data (μS/hour at 28°C) are from a representative experiment, due to variation in disease development on leaves in different experimental sets. The points represent means of data from three measurements for three samples during a single experiment, and the vertical bars are the standard errors. The experiment was repeated three times.

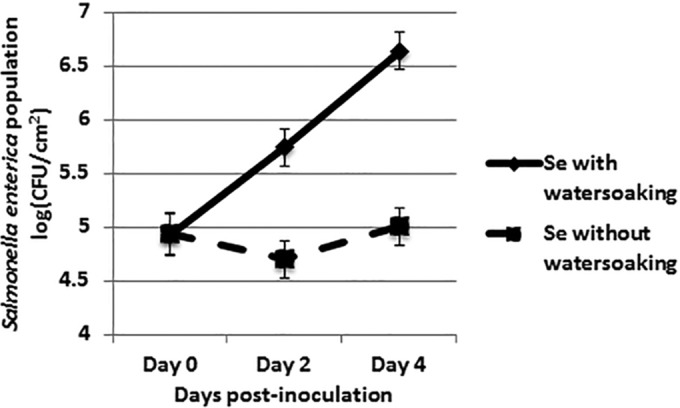

To confirm the effect of water-soaking on the growth of S. enterica, we simulated water-soaking caused by xanthomonad infection in the absence of Xanthomonas. We wanted to avoid apoplastic water stress by maintaining a water-saturated environment. S. enterica populations grew to 100-fold-higher levels by day 4 postinoculation on leaves with continuous water-soaking than on plants that were held at a low relative humidity (P = 0.001) (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Artificial water-soaking promotes S. enterica growth in the absence of a plant pathogen. Leaves of tomato cv. NIL216 plants were infiltrated with sterile deionized water followed by dip inoculation with S. enterica. A set of inoculated plants was kept under high humidity (to maintain continuous water-soaking), and another set was kept under low humidity. S. enterica populations (log CFU per square centimeter) were enumerated every 2 days for 4 dpi. The data represent results from three independent experiments combined. The points represent least-square means, and the vertical bars are the standard errors calculated from the model.

S. enterica aggregates form in areas of bacterial spot lesions and water-soaked areas.

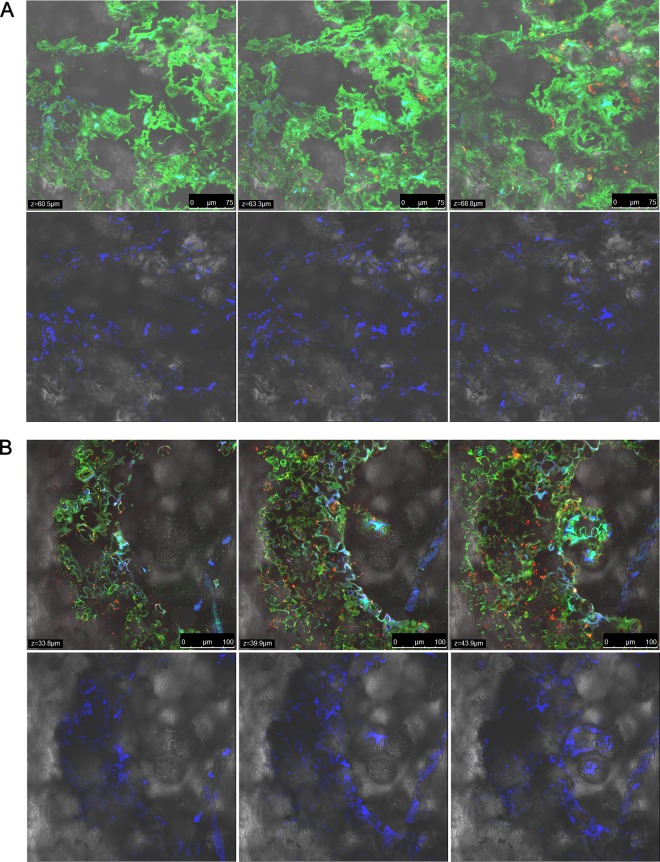

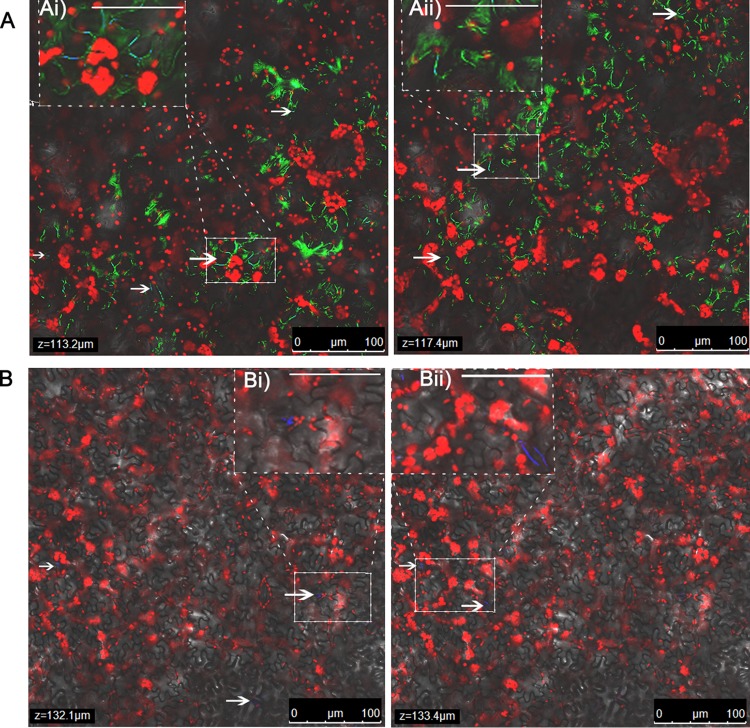

To further understand the mechanism of growth of S. enterica in X. euvesicatoria-infected leaves and no growth in X. vesicatoria-infected leaves, we examined leaf samples collected from infected plants along with leaves inoculated with S. enterica alone at 12 dpi by CLSM. As mentioned above, the two treatments (X. euvesicatoria infection and X. vesicatoria infection) differed in the extent of tissue damage. At 12 dpi, X. euvesicatoria-infected leaves showed extensive necrotic tissue with coalesced, water-soaked bacterial spot lesions spanning entire leaflets at times, while X. vesicatoria-infected leaves displayed a sparse distribution of brown-black bacterial spot lesions with defined margins, without any water-soaking or extensive necrosis. S. enterica aggregates were found in substomatal chambers and lining epidermal cells in the interior of the tissue in areas of bacterial spot lesions in either X. euvesicatoria- or X. vesicatoria-infected plants (Fig. 4A and B). However, rare S. enterica aggregates were observed in areas without bacterial spot symptoms on X. vesicatoria-infected plants, similar to leaves inoculated with S. enterica alone (Fig. 5A and B). This indicates that although necrotic tissue supports greater proliferation of S. enterica, irrespective of the species causing the infection, the difference in the extents of necrosis and water-soaking between X. euvesicatoria- and X. vesicatoria-infected leaves correlates with the differences in S. enterica populations.

FIG 4.

Salmonella enterica aggregates in areas of bacterial spot lesions caused by both X. euvesicatoria (A) and X. vesicatoria (B). Shown are representative photomicrographs of bacterial spot lesions containing GFP-labeled Xanthomonas aggregates and corresponding CFP-labeled S. enterica aggregates along a Z stack overlaid with Nomarski differential interference contrast images under a ×40 magnification. Corresponding images from the CFP channel containing CFP-labeled S. enterica cells from the same Z stacks are represented in the second row. Leaf autofluorescence is indicated by a red signal. Z values represent the distance in micrometers from the abaxial leaf surface. As shown in the CFP channel, the extent of S. enterica colonization is similar in the area of the bacterial spot lesion regardless of the Xanthomonas species present.

FIG 5.

Salmonella enterica is rare in asymptomatic areas of leaves infected with X. vesicatoria or leaves in the absence of xanthomonads. Discrete microcolonies/individual cells of S. enterica are found in areas without bacterial spot lesions on leaves inoculated with X. vesicatoria (A) or in the absence of a plant pathogen (B) along a Z stack, as indicated by arrows. Panels Ai, Aii, Bi, and Bii represent images observed at a higher magnification for the marked area in the respective Z stack (bars for Ai, Aii, Bi, and Bii, 50 μm), where CFP-labeled cells (blue) are observed. Leaf autofluorescence is indicated by the red signal.

DISCUSSION

At least two mechanisms were proposed previously for the survival and persistence of S. enterica on the leaf surface: protection from stress by forming aggregates with resident bacteria (5) and increased survival due to the suppression of plant defense responses by a plant pathogen (7, 9). Bacteria modify the phyllosphere at local sites and create conditions that are more suitable for the survival of immigrant enteric pathogens. S. enterica survival of leaf surface stresses, such as poor nutritional conditions and desiccation, appears to depend on other bacteria. The presence of epiphytes such as Pseudomonas syringae and Erwinia herbicola on lettuce and cilantro supported larger populations of S. enterica than those on plants that were not precolonized by such indigenous bacteria (5). One of the mechanisms for the increased persistence of S. enterica was suggested to be the formation of aggregates on leaves precolonized by a pathogen or epiphyte that could protect the human pathogen from desiccation stress. Although our studies found aggregates of S. enterica in close proximity to aggregates of bacterial spot xanthomonads, we never observed mixed aggregates of the two bacteria. We found that although S. enterica can colonize substomatal chambers in leaves cocolonized by X. perforans, which could offer them protective sites for survival, it failed to colonize the leaf apoplast along with X. perforans (7). Thus, the interactions of S. enterica and Xanthomonas are distinct from the interactions of S. enterica with epiphytes such as P. syringae and E. herbicola.

Indeed, our previous work showed how the immune-suppressing ability of a plant pathogen increases the survival of S. enterica (7). We observed S. enterica aggregate formation near bacterial spot disease lesions, indicating proliferation of S. enterica in X. perforans-infected leaves even in the absence of net growth. On the other hand, effector-triggered immunity activated by an avirulent plant pathogen effectively reduced S. enterica populations to levels below those observed on leaves inoculated with S. enterica alone. Based on our present findings, we propose the following mechanisms by which pathogen-induced water-soaking can promote the growth and persistence of S. enterica on leaves of tomato infected by plant pathogens such as Xanthomonas.

First, virulent bacterial spot pathogens provide a continuum of bioavailable resources across the leaf surface and alleviate osmotic stress and apoplastic growth limitations of S. enterica. The phyllosphere is generally inhospitable for bacteria, with few sites, such as trichomes, stomata, and veins, with ample water and nutrient availability to support the growth of immigrants (4). Virulent plant pathogens can modify the phyllosphere by increasing host cell leakage of water and nutrients and suppressing host defenses, permitting the growth of the pathogen and nonpathogenic immigrants (22, 23). S. enterica grew on leaves infected with either X. euvesicatoria or X. gardneri, and S. enterica bacteria were found across symptomatic leaves near bacterial spot lesions with extensive water-soaking caused by X. euvesicatoria. Bacterial spot lesions serve as a niche with water and nutrients that have leaked from cells and could allow S. enterica to replicate. We further confirmed cell leakage by determining conductance and the contribution of water-soaking to the growth of S. enterica independent of plant pathogen populations. Growth of S. enterica was observed on leaves under continuous water-soaking, compared to leaves that were allowed to dry and kept under low humidity. Incubation of plants at a high relative humidity and continuous water-soaking have been shown to promote the growth of saprophytes (24, 25). Young showed that free water, and not the availability of nutrients, supported the growth of nonpathogenic bacteria on leaf surfaces (24). Recently, a X. gardneri virulence factor, AvrHah1, that is responsible for water-soaking was identified (26). Thus, water limitation, commonly experienced by S. enterica on leaf surfaces, can be overcome by allowing the human pathogen access to apoplastic water via ingress to the leaf interior and by pathogen-induced water-soaking. Such water-soaking can make apoplastic resources more locally bioavailable by creating a continuum of free water and by solubilizing and dispersing these resources from within the plant cell to the leaf apoplast and across the leaf surface.

Further evidence for the contribution of specific disease symptoms, such as expansive secondary lesions, to the growth of S. enterica on X. euvesicatoria-infected plants comes from our study of the Never-ripe ethylene-insensitive mutant host. With an increased tolerance to virulent pathogens (27), Never-ripe plants infected with X. euvesicatoria display minimal tissue necrosis. Ethylene contributes to the regulation of symptom development (27); in wild-type plants, ethylene promotes the spread of necrosis that occurs during secondary stages of disease development, and this results in the expansion of primary lesions leading to confluent necrosis (18, 28). The secondary stages of spread of water-soaked necrotic lesions were not observed in infected Never-ripe plants. Nonetheless, X. euvesicatoria populations were similar between infected Pearson and Never-ripe plants. Differences in S. enterica populations on X. euvesicatoria-infected hosts further support the contribution of disease symptoms to the proliferation of the human pathogen on leaves.

In contrast, on X. vesicatoria-infected leaves, disease symptoms include individual spots sparsely distributed across the leaf, with only local necrosis around the lesions areas. S. enterica aggregates were rarely observed outside necrotic areas of X. vesicatoria-infected leaves, suggesting that S. enterica failed to replicate. Our data support this line of thought, as S. enterica populations on X. vesicatoria-infected leaves were similar to those on plants inoculated with S. enterica alone. Limited areas of bacterial spot lesions on X. vesicatoria-infected leaves would mean limited bioavailable resources for S. enterica to use. Although with our experimental design, X. vesicatoria caused minimal tissue damage, as indicated by conductivity measurements, X. vesicatoria can cause severe disease at lower temperatures (20°C) (20). Under such conditions, X. vesicatoria-infected plants could pose a risk of supporting S. enterica growth. These results support the conclusion that the primary mechanisms for the proliferation of S. enterica in Xanthomonas-infected plants are the symptoms of water-soaking and expansion of primary lesions leading to confluent necrosis.

Second, pathogen-induced water-soaking could suppress pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immune (PTI) responses, and plants fail to recognize S. enterica. Previously, we and others found that S. enterica triggers PTI responses (9, 29) and that PTI responses and effector-triggered immunity (ETI) limit S. enterica replication and survival (7, 9). One of the defense mechanisms developed by plants is localized desiccation at a pathogen infection site (30), essentially the opposite of water-soaking, which restricts pathogen replication in the apoplast. Water-soaking has been defined as confluent water in the apoplast (31). High water content in leaf intercellular spaces or apoplasts suppresses effector-triggered defenses, shown by preventing a hypersensitive reaction (HR) under conditions of continuous water-soaking (31). Incubation of plants with high relative humidity and continuous water-soaking promoted the growth of nonpathogens such as S. enterica, perhaps by diluting PTI signals, as well as avirulent bacteria by suppressing HR-associated restriction of growth (24, 25). Pathogens have evolved various virulence factors, including type 3 effectors, that can alter the hormonal responses and manipulate water relations by increasing the water content in the intercellular spaces for their colonization, such as WtsE in Pantoea stewartii (32), HopAM1 in Pseudomonas syringae (33), and AvrHah1 in X. gardneri (26). Thus, suppression of plant defenses by pathogen-induced water-soaking would allow S. enterica to thrive in the leaf interior by suppressing plant defenses.

Our results here indicate that plant pathogen virulence leading to water-soaking and necrosis but not Xanthomonas populations per se confers specific benefits to S. enterica, allowing growth on the leaves of tomato. Differential levels of S. enterica populations, which are supported on leaves infected by specific, virulent xanthomonads, would be of ecological and epidemiological significance, since bacterial spot disease is prevalent in tomato fields worldwide, although the causal agents can be geographically distinct (34). Water-soaking conditions or long periods of leaf wetness are common in fields during periods of high humidity and rain. Such conditions are ideal for the growth of S. enterica not only in the presence of bacterial spot pathogens but also in the absence of a plant pathogen. High humidity and rain also enhance water-soaking induced by xanthomonads during disease progression. Thus, water-soaking in the field aggravates plant disease severity and at the same time provides conditions suitable for nonpathogen growth, thereby increasing the risk that S. enterica can grow to high levels and can access the leaf interior to persist in tissues. The findings here would demand that attention be paid to the human health risk imposed by these causal agents of bacterial spot in infected tomato fields, since greater chances of fruit contamination may eventually lead to increases in salmonellosis outbreak potential. In order to achieve the goal of decreasing the incidences of human pathogens on plants, targeting phytopathogen populations would be a vital key.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the USDA NIFA (grant no. 2011-670137-30166) and the Food Research Institute, University of Wisconsin—Madison.

We thank Kimberly Cowles for helpful discussions of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01926-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berger CN, Sodha SV, Shaw RK, Griffin PM, Pink D, Hand P, Frankel G. 2010. Fresh fruit and vegetables as vehicles for the transmission of human pathogens. Environ Microbiol 12:2385–2397. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barak JD, Liang AS. 2008. Role of soil, crop debris, and a plant pathogen in Salmonella enterica contamination of tomato plants. PLoS One 3:e1657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barak JD, Schroeder BK. 2012. Interrelationships of food safety and plant pathology: the life cycle of human pathogens on plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol 50:241–266. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-081211-172936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monier JM, Lindow SE. 2004. Frequency, size, and localization of bacterial aggregates on bean leaf surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:346–355. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.346-355.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poza-Carrion C, Suslow T, Lindow SE. 2013. Resident bacteria on leaves enhance survival of immigrant cells of Salmonella enterica. Phytopathology 103:341–351. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-12-0221-FI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barak JD, Kramer LC, Hao L. 2011. Colonization of tomato plants by Salmonella enterica is cultivar dependent, and type 1 trichomes are preferred colonization sites. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:498–504. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01661-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potnis N, Soto-Arias JP, Cowles KN, van Bruggen AHC, Jones JB, Barak JD. 2014. Xanthomonas perforans colonization influences Salmonella enterica in the tomato phyllosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3173–3180. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00345-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells JM, Butterfield JE. 1997. Salmonella contamination associated with bacterial soft rot of fresh fruits and vegetables in the marketplace. Plant Dis 81:867–872. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.1997.81.8.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng F, Altier C, Martin GB. 2013. Salmonella colonization activates the plant immune system and benefits from association with plant pathogenic bacteria. Environ Microbiol 15:2418–2430. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwan G, Charkowski AO, Barak JD. 2013. Salmonella enterica suppresses Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum population and soft rot progression by acidifying the microaerophilic environment. mBio 4:e00557-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00557-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pollard S, Barak JD, Boyer R, Reiter M, Gu G, Rideout S. 2014. Potential interactions between Salmonella enterica and Ralstonia solanacearum in tomato plants. J Food Prot 77:320–324. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simko I, Zhou Y, Brandl M. 2015. Downy mildew disease promotes the colonization of romaine lettuce by Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica. BMC Microbiol 15:19. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potnis N, Krasileva K, Chow V, Almeida NF, Patil PB, Ryan RP, Sharlach M, Behlau F, Dow JM, Momol M, White FF, Preston JF, Vinatzer BA, Koebnik R, Setubal JC, Norman DJ, Staskawicz BJ, Jones JB. 2011. Comparative genomics reveals diversity among xanthomonads infecting tomato and pepper. BMC Genomics 12:146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller WG, Leveau JH, Lindow SE. 2000. Improved gfp and inaZ broad-host-range promoter-probe vectors. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13:1243–1250. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.11.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller J. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y, Callaway E, Jones J, Wilson M. 2009. Visualisation of hrp gene expression in Xanthomonas euvesicatoria in the tomato phyllosphere. Eur J Plant Pathol 124:379–390. doi: 10.1007/s10658-008-9423-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller WG, Bates AH, Horn ST, Brandl MT, Wachtel MR, Mandrell RE. 2000. Detection on surfaces and in Caco-2 cells of Campylobacter jejuni cells transformed with new gfp, yfp, and cfp marker plasmids. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:5426–5436. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.12.5426-5436.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ciardi JA, Tieman DM, Lund ST, Jones JB, Stall RE, Klee HJ. 2000. Response to Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria in tomato involves regulation of ethylene receptor gene expression. Plant Physiol 123:81–92. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook AA, Stall RE. 1968. Effect of Xanthomonas vesicatoria on loss of electrolytes from leaves of Capsicum annuum. Phytopathology 58:617–619. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Araújo ER, Pereira RC, Moita AW, Ferreira MASV, Café-Fiho AC, Quezado-Duval AM. 2011. Effect of temperature on pathogenicity components of tomato bacterial spot and competition between Xanthomonas perforans and X. garnderi. Acta Hortic 914:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stall RE, Hall CB. 1984. Chlorosis and ethylene production in pepper leaves infected with Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria. Phytopathology 74:373–375. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-74-373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundin GW. 2006. Host-pathogen interactions of relevance to the phyllosphere, p 201–208. In Bailey MJ, Lilley AK, Timms-Vilson TM, Spencer-Phillips PTN (ed), Microbial ecology of aerial plant surfaces. CAB International, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beattie GA, Lindow SE. 1995. The secret life of foliar bacterial pathogens on leaves. Annu Rev Phytopathol 33:145–172. doi: 10.1146/annurev.py.33.090195.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Young JM. 1973. Effect of water on bacterial multiplication in plant tissue. N Z J Agric Res 17:115–119. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cook AA, Stall RE. 1977. Effects of watersoaking on response to Xanthomonas vesicatoria in pepper leaves. Phytopathology 67:1101–1103. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schornack S, Minsavage GV, Stall RE, Jones JB, Lahaye T. 2008. Characterization of AvrHah1, a novel AvrBs3-like effector from Xanthomonas gardneri with virulence and avirulence activity. New Phytol 178:546–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lund ST, Stall RE, Klee HJ. 1998. Ethylene regulates the susceptible response to pathogen infection in tomato. Plant Cell 10:371–382. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.3.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malamy J, Carr JP, Klessig DF, Raskin I. 1990. Salicylic acid: a likely endogenous signal in the resistance response of tobacco to viral infection. Science 250:1002–1004. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4983.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roy D, Panchal S, Rosa BA, Melotto M. 2013. Escherichia coli O157:H7 induces stronger plant immunity than Salmonella enterica Typhimurium SL1344. Phytopathology 103:326–332. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-12-0230-FI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beattie GA. 2011. Water relations in the interaction of foliar bacterial pathogens with plants. Annu Rev Phytopathol 49:533–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stall RE, Cook AA. 1979. Evidence that bacterial contact with the plant cell is necessary for the hypersensitive reaction but not the susceptible reaction. Physiol Plant Pathol 14:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0048-4059(79)90027-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ham JH, Majerczak DR, Arroyo-Rodriguez AS, Mackey DM, Coplin DL. 2006. WtsE, an AvrE-family effector protein from Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii, causes disease-associated cell death in corn and requires a chaperone protein for stability. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 19:1092–1102. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goel AK, Lundberg D, Torres MA, Matthews R, Akimoto-Tomiyama C, Farmer L, Dangl JL, Grant SR. 2008. The Pseudomonas syringae type III effector HopAM1 enhances virulence on water-stressed plants. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 21:361–370. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-21-3-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones JB, Stall RE, Bouzar H. 1998. Diversity among Xanthomonas pathogenic on pepper and tomato. Annu Rev Phytopathol 36:41–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.36.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.