Abstract

Background:

This study aimed to determine if associations of pre-diagnostic percent breast density, absolute dense area, and non-dense area with subsequent breast cancer risk differ by the tumour's molecular marker status.

Methods:

We included 1010 postmenopausal women with breast cancer and 2077 matched controls from the Nurses' Health Study (NHS) and the Nurses' Health Study II (NHS II) cohorts. Breast density was estimated from digitised film mammograms using computer-assisted thresholding techniques. Information on breast cancer risk factors was obtained prospectively from biennial questionnaires. Polychotomous logistic regression was used to assess associations of breast density measures with tumour subtypes by the status of selected tissue markers. All tests of statistical significance were two sided.

Results:

The association of percent density with breast cancer risk appeared to be stronger in ER− as compared with ER+ tumours, but the difference did not reach statistical significance (density ⩾50% vs <10% odds ratio (OR)=3.06, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.17–4.32 for ER+ OR=4.61, 95% CI 2.36–9.03 for ER−, Pheterogeneity=0.08). Stronger positive associations were found for absolute dense area and CK5/6− and EGFR− as compared with respective marker-positive tumours (Pheterogeneity=0.002 and 0.001, respectively). Stronger inverse associations of non-dense area with breast cancer risk were found for ER− as compared with ER+ tumours (Pheterogeneity=0.0001) and for AR+, CK5/6+, and EGFR+ as compared with respective marker-negative tumours (Pheterogeneity=0.03, 0.005, and 0.009, respectively). The associations of density measures with breast cancer did not differ by progesterone receptor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status.

Conclusions:

Breast density influences the risk of breast cancer subtypes by potentially different mechanisms.

Keywords: breast density, molecular tissue markers, breast cancer subtypes

Mammographic breast density is a well-established and strong predictor of breast cancer risk (McCormack and dos Santos Silva, 2006). Appearance of the breast on the mammogram is a reflection of the amount of fat, connective tissue, and epithelial tissue in the breast (Tamimi et al, 2007). Women with 75% or greater percent breast density (proportion of the total breast area that appears dense on the mammogram) are at four- to six-fold greater risk of breast cancer compared with women with predominantly fatty breasts (Boyd et al, 1995, Byrne et al, 1995, Tamimi et al, 2007). Absolute dense area of the breast that represents fibroglandular tissue has been shown to be positively associated with breast cancer risk while findings for the association between non-dense area of the breast (representing adipose tissue) and breast cancer risk have been conflicting (Pettersson et al, 2014).

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease; different molecular subtypes of breast cancer have distinct clinico-morphological features and biomarker expression that influence patient survival (Arpino et al, 2004, Putti et al, 2005, Phipps et al, 2010). We have recently reported a stronger association of percent breast density with the risk of more unfavourable oestrogen receptor-negative breast tumours (ER−) as compared with oestrogen receptor-positive tumours (ER+) among postmenopausal women (Yaghjyan et al, 2011). Also, a large pooled analysis showed a stronger association of percent density with ER− tumours among younger women suggesting that high density may play an important role in tumour aggressiveness (Bertrand et al, 2013). Whether the associations of breast density with breast cancer risk differ by status of other tissue markers implicated in breast cancer aetiology and prognosis is unknown. Understanding these differences might help to identify biological pathways linking high density to specific breast cancer subtypes. We analysed prospective data in postmenopausal women from the Nurses' Health Study (NHS) and the Nurses' Health Study II (NHS II) cohorts to determine if there are differences in the associations of percent breast density, absolute dense area, and non-dense area with subsequent risk of breast cancer according to the tumour's status of the following tissue markers involved in cellular proliferation, differentiation, and angiogenesis that have been shown to influence tumour aggressiveness: oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), proliferation marker Ki67, androgen receptor (AR), cytokeratins 5/6 (CK5/6), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Materials and Methods

Study population and design

Women included in this study were selected from participants of the NHS and NHS II cohorts. These prospective cohorts followed registered nurses in the United States who were 30–55 years (NHS) or 25–42 years old (NHS II) at enrolment. After administration of the initial questionnaire, the information on breast health risk factors and any cancer diagnoses was updated biennially. More detailed description of the cohort has been published elsewhere (Colditz and Hankinson, 2005).

We used a nested case-control study design to examine the association between three breast density measures with breast tumour subtypes defined based on the selected marker's status. Details of this nested case-control study have been previously described (Yaghjyan et al, 2011). Briefly, using incidence density sampling, women who did not have any type of cancer at the time of the cases' breast cancer diagnosis (controls) were matched with women diagnosed with in situ or invasive breast cancer (cases) during the follow-up period from 1 June 1989 through 30 June 2004 for NHS and from 1 June 1996 to 30 June 2007 for NHS II (Colditz and Hankinson, 2005). Breast cancer cases were confirmed through medical record review by trained personnel. Because the original study was designed to evaluate associations between circulating biomarkers and breast cancer risk, the cases were matched with controls on age, menopausal status, postmenopausal hormone use (current vs not current) at blood collection, and day and time of blood collection. This study was approved by the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects in Research at Brigham and Women's Hospital. All participants provided written informed consent.

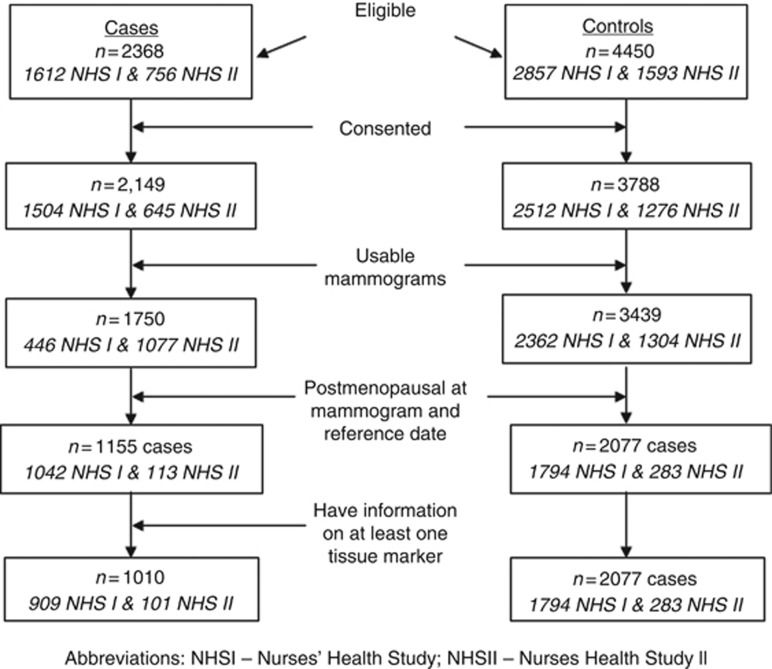

We attempted to obtain mammograms closest to the time of blood collection from 2368 eligible cases and 4450 controls. Of the 5189 women with available mammograms, 3234 cases and controls combined (62%) were postmenopausal at the time of both the mammogram and the reference date (date of diagnosis for cases and their matched controls). Owing to the limited number of premenopausal women with available marker data we were unable to evaluate the associations of density with breast cancer subtypes in premenopausal women. We further restricted our analysis to postmenopausal cases with information on at least one of the tissue markers. The final study population included 1010 cases and 2077 controls (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of participant selection.

Mammographic breast density

The screening mammogram before the reference date was used for density measurements. The average time between the mammogram date and the date of breast cancer diagnosis was 4.8 years (interquartile range (IQR)=2–7 years) for NHS I and 3.0 years (IQR=1–5 years) for NHS II. The average time between mammogram and the reference date of controls was 4.2 years (IQR=1–7 years) for NHS I and 1.5 years (IQR=0–5 years) for NHS II. All mammograms in the study were film (analogue) mammograms. To quantify mammographic density, the craniocaudal views of both breasts were digitised at 261 μm per pixel with a Lumisys 85 laser film scanner (Lumisys, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The Cumulus software (University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada) was used for computer-assisted determination of the absolute dense area, non-dense area, and percent density (Byng et al, 1996). During this assessment, the observer was blinded to the participant's case-control status. As reported previously, the measure of mammographic breast density from NHS I mammograms was highly reproducible (within-person intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.93) (Tamimi et al, 2007). All NHS II images were read by a single reader in two batches of mammograms ∼3 years apart. Cases and their matched controls were included in the same batch. Although within batch reproducibility was high (interclass correlation coefficient 0.90 and greater) (Pettersson et al, 2011), density measures varied across the two NHS II batches. We included a small subset of identical mammograms in both batches to account for batch drift in density measurement readings. The density measures from the second batch of NHS II mammograms were adjusted to account for the effect of batch on density measurements, as previously described (Bertrand et al, 2012).

Because breast densities of the right and left breast for an individual woman are strongly correlated (correlation coefficient=0.92–0.96 for density estimated from right vs left craniocaudal views) (Byng et al, 1996), the average density of both breasts was used in this analysis.

Breast cancer tissue markers

Information on the tumour's ER, PR, and HER2 status was obtained primarily from pathology reports and medical records. For breast cancers with missing receptor data from pathology reports, the receptor status was obtained from immunohistochemical staining performed on paraffin sections of the tumour tissue microarray (TMA) according to a standard protocol (Tamimi et al, 2008). Of all cases in the study, information on ER, PR, and HER2 status was available for 94% (n=933), 93% (n=916), and 71% (n=701), respectively. Among women with receptor status information, ER, PR, and HER2 receptor status was available from the pathology reports for 94%, 93%, and 44% of the tumours, respectively. Information on Ki67, AR, CK5/6, EGFR, and VEGF status was obtained from TMA only and was available for 16% (n=160), 41% (n=406), 29% (n=285), 30% (n=297), and 18% (n=182) of cases, respectively.

Variation in the number of cases with available marker data is explained by the source of marker data (pathology reports and TMA (ER, PR, HER2) vs TMA only (all other markers)) as well as funding support for quantification for each of the markers. Currently, tissue blocks have been obtained and TMAs created for ∼0% of all eligible cases in the cohort. However, as quantification of each of the markers is supported by a different grant, not every TMA are stained and scored at the same time for all of these markers resulting in variation in the number of cases with available marker data across the markers.

Immunostained TMA sections were reviewed by an expert pathologist and visually scored for the percentage of cells that stained positively for each of the markers. For ER and PR, positivity from TMA was defined as >1% of tumour cell nuclei staining (Hefti et al, 2013). For AR, positivity from TMA was defined as >10% of tumour cell nuclei staining. (Tamimi et al, 2008) Moderate (2+) or strong (3+) membrane staining (as opposed to low (1+) or none (0)) for HER2 in more than 10% of the tumour cells was used as the cut-off for tumour's HER2 positivity (Tamimi et al, 2008). Cases were considered CK5/6-positive or EGFR-positive if any staining was detected in the tumour cells, including only focal (Collins et al, 2011). VEGF-positivity was defined as any staining in the cytoplasm of tumour cells (Liu et al, 2011).

We quantified Ki67 expression with the aid of computational image analysis, implemented with Definiens Tissue Studio (Munich, Germany). For each core, we computed the number of total nuclei and the number of Ki67-positive nuclei. We aggregated counts of Ki67-positive nuclei and total nuclei across a patient's TMA cores, and cases were considered Ki67-positive if the sum of the percentage of Ki67-positive nuclei across cores was 14% or greater (Cheang et al, 2009).

Covariates

Information on breast cancer risk factors was obtained from the biennial questionnaires before the reference date. Women were considered to be postmenopausal if they reported: (1) no menstrual periods within the 12 months before blood collection with natural menopause, (2) bilateral oophorectomy, or (3) hysterectomy with one or both ovaries retained and were 54 years or older for ever smokers or 56 years or older for never smokers (Willett et al, 1983).

Statistical analysis

We used Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test to analyse the difference in breast density distributions in cases and controls. We used unconditional logistic regression to analyse the association between breast density measures and breast cancer risk, while adjusting for the following potential confounders in the fully adjusted logistic regression models: age at diagnosis (continuous, years), body mass index (continuous, kg m−2), age at menarche (<12, 12, 13, >13 years), parity and age at first birth (nulliparous, 1–4 children/<25 years, 1–4 children/25–29 years, 1–4 children/ ⩾30 years, ⩾5 children/<25 years, ⩾5 children/⩾25 years), postmenopausal hormone use (never, ever, unknown), age at menopause (<46, 46–<50, 50–<55, ⩾55 years, unknown), family history of breast cancer (yes, no), alcohol consumption (0, <5, 5 to <15, ⩾15 g per day), and study cohort (NHS, NHS II).

Percent breast density was categorised as <10% (referent), 10–24%, 25–49%, and ⩾50%. Absolute dense and non-dense areas were categorised as quartiles based on their distribution in controls (absolute dense area: <19 cm2 (referent), 19–<35 cm2, 35–<61 cm2, ⩾61 cm2; non-dense area: <83 cm2 (referent), 83–<138 cm2, 138–<208 cm2, ⩾208 cm2).

Differences in the association of breast density with receptor-specific tumour subtypes were investigated using polychotomous logistic regression (Tamimi et al, 2007). In this analysis, the outcome has three levels that include controls and two breast cancer subtypes defined based on the receptor status (receptor-positive and receptor-negative, for e.g., ER+ and ER− breast cancer). In additional analysis, we also compared these associations in ER+/PR+ and ER−/PR− tumours. We did not analyse the association between breast density and breast cancer risk by combined ER, PR, and HER2 (ER/PR/HER2) status or by combined CK5/6/EGFR status because the small number of tumours in some subsets did not provide sufficient power to draw meaningful conclusions. For example, defining subtypes based on ER, PR, and HER2 resulted in the following numbers: ER+/PR+/ HER2− n=356; ER+/PR+/HER2+ n=82; ER−/PR−/HER2+ n=39, ER−/PR−/HER2− n=57. The numbers further became much smaller when CK5/6, EGFR and Ki67 were considered. We used a likelihood ratio test to compare a model with separate mammographic density slopes in each case group with a model with a common slope. This method has been described in detail elsewhere (Yaghjyan et al, 2011). In this analysis, the density measures were modelled using respective medians within each of the density categories. For all analyses, the level of statistical significance was assessed at α=0.05. All tests were two sided.

Because the ER and PR status were moderately correlated, in a secondary analysis we used previously published method to examine associations of percent density with breast cancer by ER status while adjusting for PR (Rosner et al, 2013). All analyses except the test of heterogeneity were performed using SAS software (version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The test of heterogeneity from polychotomous logistic regression models was done using STATA version 11.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

In this nested case-control study of 1010 postmenopausal women diagnosed with breast cancer and 2077 matched controls, cases had a higher median percent breast density (28.1% vs 21.6%, P<0.0001), higher median absolute dense area (45.1 vs 35.4 cm2, P<0.0001) and smaller median area of non-dense breast tissue (120.5 vs138.5 cm2, P<0.0001) as compared with controls. Distribution of breast cancer risk factors in this study population is presented in Table 1. Cases were more likely to have a history of postmenopausal hormone use (76.1% vs 71.6% P=0.01), a family history of breast cancer (19.6% vs 14.4% P<0.001), a confirmed benign breast disease (33.4% vs 25.8% P<0.0001), and older age at natural menopause (48.9 vs 48.4; P=0.02) as compared with controls. Cases and controls did not differ significantly with respect to other risk factors.

Table 1. Characteristics of postmenopausal women in the study, by disease status.

| Characteristic | Cases (N=1010) | Controls (N=2077) | P-for difference between cases and controlsa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median % mammographic breast density | 28.1 | 21.6 | <0.001 |

| Median absolute dense area, cm2 | 45.1 | 35.4 | <0.001 |

| Median non-dense area, cm2 | 120.5 | 138.5 | <0.001 |

|

Mean (s.d.) | |||

| Age at mammogram, years | 59.2 (7.3) | 59.2 (7.5) | 0.88 |

| Age at menarche, years | 12.5 (1.6) | 12.5 (1.4) | 0.42 |

| Age at natural menopause, years | 48.9 (5.1) | 48.4 (5.6) | 0.02 |

| Body mass index at diagnosis, kg m−2 | 26.4 (4.9) | 26.5 (5.3) | 0.57 |

| Alcohol use at diagnosis, g per day | 5.5 (9.2) | 5.2 (8.8) | 0.30 |

|

Frequency (%) | |||

| Parity and age at first child's birthb | 0.38 | ||

| Nulliparous | 92 (9.1) | 156 (7.5) | |

| 1–4 children with age at first birth <25 years | 346 (34.3) | 771 (37.1) | |

| 1–4 children with age at first birth of 25–29 years | 308 (30.5) | 620 (30.0) | |

| 1–4 children with age at first birth of ⩾30 years | 100 (9.9) | 199 (9.6) | |

| ⩾5 children with age at first birth of <25 years | 88 (8.7) | 207 (10.0) | |

| ⩾5 children with age at first birth of ⩾25 years | 60 (5.9) | 112 (5.4) | |

| Postmenopausal hormone therapy | 0.01 | ||

| Never used hormones | 213 (21.1) | 538 (25.9) | |

| Ever used hormones | 769 (76.1) | 1486 (71.6) | |

| With unknown hormone use status | 28 (2.8) | 53 (2.6) | |

| Family history of breast cancer | 198 (19.6) | 298 (14.4) | <0.001 |

| Benign breast disease | 337 (33.4) | 535 (25.8) | <0.001 |

P-values for Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test (density), two-sample t-test (continuous variables), or χ2-test (categorical variables).

Twenty-eight women (12 controls and 16 cases) have missing values.

In the multivariable analysis, higher percent density was associated with breast cancer risk increase (⩾50% vs <10%, odds ratio (OR)=3.18, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.32–4.35, Ptrend <0.0001). Larger absolute dense area was associated with an increase in breast cancer risk (4th vs 1st quartile, OR=1.93, 95% CI 1.52–2.45, Ptrend <0.0001), while larger non-dense area was associated with breast cancer risk decrease (4th vs 1st quartile, OR=0.52, 95% CI 0.40–0.68, Ptrend <0.0001) (Supplementary table 1).

Breast density and breast cancer risk according to the marker status

Correlations of tissue markers with each other are presented in Table 2. We observed a positive moderate correlation of ER with PR (correlation coefficient r=0.54, P<0.0001) and AR (r=0.41, P<0.0001) and negative moderate correlation with EGFR (r=−0.44, P<0.0001). CK5/6 was moderately correlated with EGFR (r=0.58, P<0.0001). None of the other markers were correlated with each other.

Table 2. Correlations between eight tissue markers evaluated among 1010 cases included in the study.

|

Spearman correlation coefficient (P-value),

n |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (n=916) | HER2 (n=701) | AR (n=406) | CK5/6 (n=285) | EGFR (n=297) | VEGF (n=182) | Ki67 (n=160) | |

| ER (n=933) | 0.54 (<0.0001) 915 | −0.19 (<0.0001) 671 | 0.41 (<0.0001) 382 | −0.10 (0.08) 285 | −0.44 (<0.0001) 299 | −0.09 (0.27) 160 | −0.31 (0.0001) 150 |

| PR | – | −0.16 (<0.0001) 657 | 0.27 (<0.0001) 371 | −0.12 (0.03) 288 | −0.24 (<0.0001) 301 | −0.03 (0.73) 147 | −0.21 (0.01) 145 |

| HER2 | – | – | −0.08 (0.10) 405 | −0.06 (0.31) 282 | 0.14 (0.02) 295 | 0.01 (0.89) 178 | 0.02 (0.83) 159 |

| AR | – | – | – | 0.08 (0.27) 202 | −0.13 (0.06) 202 | −0.19 (0.01) 177 | −0.29 (0.0007) 134 |

| CK5/6 | – | – | – | – | 0.58 (<0.0001) 274 | NEa | 0.13 (0.24) 78 |

| EGFR | – | – | – | – | – | NEb | 0.13 (0.25) 79 |

| VEGF | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.21 (0.07) 76 |

Abbreviations: AR=androgen receptor; CK5/6=cytokeratins 5/6; EGFR=epidermal growth factor receptor; ER=oestrogen receptor; HER2=human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; Ki67=proliferation marker; PR=progesterone receptor; VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor.

Non estimable: all tumours CK5/6.

Non estimable: all tumours EGFR– and VEGF.

Percent breast density

Percent density was positively associated with all marker-defined subtypes of breast cancer (Table 3). The association of percent density with breast cancer risk appeared to be stronger in ER− tumours as compared with ER+ tumours, as we reported previously.(Yaghjyan et al, 2011) This difference in associations by ER status, however, did not reach statistical significance (density ⩾50 vs <10% OR=3.06, 95% CI 2.17–4.32 for ER+ tumours; OR=4.61, 95% CI 2.36–9.03 for ER− tumours, Pheterogeneity=0.08). In the analysis of associations by ER status adjusted for PR status (915 cases), the difference in the association by ER status did not reach statistical significance (Pheterogeneity=0.20). In the additional analysis comparing ER+/PR+ and ER−/PR− tumours, the association of percent density appeared to be stronger in ER−/PR− tumours (OR=4.59, 95% CI 2.15–9.83 vs OR=3.03, 95% CI 2.07–4.43); the difference, however, did not reach statistical significance (Pheterogeneity=0.35).

Table 3. Association of percent breast density with the risk of marker-defined subtypes of breast cancer in postmenopausal womena.

|

Tumor subtype by receptor status |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Marker-positive |

Marker-negative |

||||

| Tumour Marker | Percent density category | No. cases/controls | OR (95% CI) | No. cases/controls | OR (95% CI) | P-valueb |

| ER | Total | 768/2052 | 165/2052 | |||

| <10% | 112/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 17/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 0.08 | |

| 10–24% | 224/727 | 1.36 (1.04–1.77) | 48/727 | 1.78 (1.00–3.17) | ||

| 25–49% | 312/651 | 2.39 (1.82–3.14) | 65/651 | 2.75 (1.53–4.95) | ||

| ⩾50 | 120/213 | 3.06 (2.17–4.32) | 35/213 | 4.61 (2.36–9.03) | ||

| Ptrend | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| PR | Total | 633/2052 | 283/2052 | |||

| <10% | 94/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 32/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 0.63 | |

| 10–24% | 176/727 | 1.27 (0.95–1.69) | 96/727 | 1.91 (1.25–2.94) | ||

| 25–49% | 261/651 | 2.37 (1.77–3.18) | 102/651 | 2.37 (1.52–3.72) | ||

| ⩾50 | 102/213 | 3.04 (2.10–4.40) | 53/213 | 3.95 (2.34–6.65) | ||

| Ptrend | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| HER2 | Total | 164/2052 | 537/2052 | |||

| <10% | 21/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 76/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 0.43 | |

| 10–24% | 51/727 | 1.56 (0.91–2.68) | 161/727 | 1.38 (1.01–1.87) | ||

| 25–49% | 74/651 | 2.89 (1.68–4.98) | 210/651 | 2.16 (1.57–2.96) | ||

| ⩾50 | 18/213 | 2.39 (1.16–4.89) | 90/213 | 2.99 (2.02–4.42) | ||

| Ptrend | 0.001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Ki67 | Total | 42/2052 | 118/2052 | |||

| <10% | 5/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 14/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 0.47 | |

| 10–24% | 10/727 | 1.43 (0.47–4.39) | 32/727 | 1.69 (0.88–3.26) | ||

| 25–49% | 18/651 | 3.48 (1.17–10.39) | 55/651 | 3.74 (1.95–7.20) | ||

| ⩾50 | 9/213 | 6.74 (1.90–23.83) | 17/213 | 3.96 (1.76–8.93) | ||

| Ptrend | 0.0003 | <0.0001 | ||||

| CK5/6 | Total | 50/2052 | 235/2052 | |||

| <10% | 9/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 30/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 0.46 | |

| 10–24% | 13/727 | 1.05 (0.44–2.55) | 74/727 | 1.58 (1.00–2.49) | ||

| 25–49% | 23/651 | 2.43 (1.03–5.78) | 94/651 | 2.47 (1.55–3.93) | ||

| ⩾50 | 5/213 | 2.26 (0.67–7.62) | 37/213 | 3.29 (1.85–5.84) | ||

| Ptrend | 0.03 | <0.0001 | ||||

| AR | Total | 301/2052 | 105/2052 | |||

| <10% | 49/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 18/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 0.35 | |

| 10–24% | 82/727 | 1.10 (0.75–1.61) | 26/727 | 0.99 (0.53–1.86) | ||

| 25–49% | 119/651 | 1.83 (1.24–2.70) | 36/651 | 1.70 (0.90–3.21) | ||

| ⩾50 | 51/213 | 2.53 (1.56–4.10) | 25/213 | 4.27 (2.06–8.86) | ||

| Ptrend | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| EGFR | Total | 48/2052 | 249/2052 | |||

| <10% | 8/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 35/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 0.36 | |

| 10–24% | 16/727 | 1.37 (0.57–3.32) | 73/727 | 1.36 (0.88–2.10) | ||

| 25–49% | 19/651 | 1.97 (0.79–4.93) | 105/651 | 2.48 (1.60–3.86) | ||

| ⩾50 | 5/213 | 1.89 (0.55–6.55) | 36/213 | 2.97 (1.70–5.19) | ||

| Ptrend | 0.18 | <0.0001 | ||||

| VEGF | Total | 145/2052 | 37/2052 | |||

| <10% | 26/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 4/461 | 1.00 (referent) | 0.35 | |

| 10–24% | 40/727 | 1.08 (0.64–1.84) | 8/727 | 1.10 (0.32–3.85) | ||

| 25–49% | 51/651 | 1.53 (0.89–2.61) | 18/651 | 2.52 (0.76–8.33) | ||

| ⩾50 | 28/213 | 2.68 (1.41–5.12) | 7/213 | 3.01 (0.74–12.29) | ||

| Ptrend | 0.0009 | 0.04 | ||||

Abbreviations: AR=androgen receptor; CI=confidence interval; CK5/6=cytokeratins 5/6; EGFR=epidermal growth factor receptor; ER=oestrogen receptor; HER2=human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; Ki67=proliferation marker; OR=odds ratio; PR=progesterone receptor; SE=standard error; VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor.

Polychotomous multivariable logistic regression model adjusted for age (continuous), body mass index (continuous), age at menarche (<12, 12, 13, or >13 years), parity and age at first birth (nulliparous, 1–4 children with age at first birth <25 years, 1–4 children with age at first birth of 25–29 years, 1–4 children with age at first birth of ⩾30 years, ⩾5 children with age at first birth of <25 years, or ⩾5 children with age at first birth of ⩾25 years), age at menopause (<46, 46–<50, 50–<55, ⩾55, unknown), postmenopausal hormone use (never, ever, unknown), family history (yes or no), confirmed history of benign breast disease (yes or no), alcohol consumption (0, <5, 5 to <15, or ⩾15 g per day), and NHS cohort (NHS II vs NHS).

P-values for the test of heterogeneity of odds ratios were calculated using a two-sided likelihood ratio test.

No differences across the subtypes were observed for any of the other markers (Table 3).

Absolute dense area

In the analyses by the tumour's ER, PR, and HER2 status, absolute dense area was positively associated with increased breast cancer risk in both marker-positive and marker-negative tumours and these subset-specific associations were similar (Table 4). The association of absolute dense area was similar while comparing ER+/PR+ and ER−/PR− tumours (Pheterogeneity=0.32).

Table 4. Association of absolute dense area and non-dense area with the risk of marker-defined subtypes of breast cancer in postmenopausal womena.

|

Absolute dense area |

Non-dense area |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Marker-negative subtype |

Marker-positive subtype |

Marker-positive subtype |

Marker-negative subtype |

|||||||

| Tumor marker | Density category | No. cases/controls | OR (95% CI) | No. cases/controls | OR (95% CI) | P-valueb | No. cases/controls | OR (95% CI) | No. cases/controls | OR (95% CI) | P-valueb |

| ER | Total | 768/2052 | 165/2052 | 0.27 | 768/2052 | 165/2052 | 0.0001 | ||||

| 1st quartile | 131/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 31/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 225/518 | 1.00 (referent) | 74/518 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| 2nd quartile | 141/503 | 1.09 (0.83–1.43) | 34/503 | 1.03 (0.62–1.72) | 199/506 | 0.85 (0.67–1.08) | 42/506 | 0.56 (0.36–0.85) | |||

| 3rd quartile | 236/524 | 1.75 (1.35–2.25) | 51/524 | 1.46 (0.91–2.36) | 178/512 | 0.70 (0.54– 0.90) | 26/512 | 0.32 (0.19–0.53) | |||

| 4th quartile | 260/515 | 2.06 (1.59–2.67) | 49/515 | 1.48 (0.90–2.44) | 166/516 | 0.60 (0.45–0.80) | 23/516 | 0.26 (0.14–0.46) | |||

| Ptrend | <0.0001 | 0.07 | 0.0003 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| PR | Total | 633/2052 | 283/2052 | 0.98 | 633/2052 | 283/2052 | 0.46 | ||||

| 1st quartile | 113/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 45/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 192/518 | 1.00 (referent) | 99/518 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| 2nd quartile | 120/503 | 1.05 (0.79–1.41) | 53/503 | 1.14 (0.75–1.75) | 167/506 | 0.83 (0.65–1.07) | 69/506 | 0.70 (0.50–0.99) | |||

| 3rd quartile | 185/524 | 1.56 (1.18–2.04) | 94/524 | 1.93 (1.31–2.84) | 145/512 | 0.66 (0.50–0.87) | 57/512 | 0.55 (0.37–0.80) | |||

| 4th quartile | 215/515 | 1.94 (1.47–2.56) | 91/515 | 1.92 (1.29–2.87) | 129/516 | 0.53 (0.39–0.73) | 58/516 | 0.53 (0.35–0.80) | |||

| Ptrend | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | |||||||

| HER2 | Total | 164/2052 | 537/2052 | 0.49 | 164/2052 | 537/2052 | 0.97 | ||||

| 1st quartile | 25/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 85/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 48/518 | 1.00 (referent) | 146/518 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| 2nd quartile | 35/503 | 1.42 (0.83–2.42) | 93/503 | 1.09 (0.79–1.51) | 48/506 | 0.88 (0.57–1.36) | 133/506 | 0.90 (0.68–1.19) | |||

| 3rd quartile | 47/524 | 1.79 (1.07–2.99) | 156/524 | 1.74 (1.29–2.34) | 23/512 | 0.38 (0.22–0.66) | 141/512 | 0.90 (0.68–1.20) | |||

| 4th quartile | 57/515 | 2.16 (1.29–3.61) | 203/515 | 2.33 (1.73–3.15) | 45/516 | 0.67 (0.40–1.13) | 117/516 | 0.73 (0.53–1.01) | |||

| Ptrend | 0.003 | <0.0001 | 0.07 | 0.06 | |||||||

| Ki67 | Total | 42/2052 | 118/2052 | 0.43 | 42/2052 | 118/2052 | 0.31 | ||||

| 1st quartile | 9/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 19/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 13/518 | 1.00 (referent) | 49/518 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| 2nd quartile | 9/503 | 0.96 (0.37–2.49) | 26/503 | 1.43 (0.77–2.65) | 11/506 | 0.85 (0.37–2.00) | 33/506 | 0.65 (0.40–1.06) | |||

| 3rd quartile | 7/524 | 0.80 (0.29–2.21) | 43/524 | 2.34 (1.32–4.13) | 12/512 | 0.96 (0.40–2.34) | 19/512 | 0.33 (0.18–0.61) | |||

| 4th quartile | 17/515 | 2.42 (1.03–5.69) | 30/515 | 2.03 (1.10–3.72) | 6/516 | 0.44 (0.14–1.38) | 17/516 | 0.26 (0.13–0.52) | |||

| Ptrend | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.19 | <0.0001 | |||||||

| CK5/6 | Total | 50/2052 | 235/2052 | 0.002 | 50/2052 | 235/2052 | 0.005 | ||||

| 1st quartile | 14/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 36/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 19/518 | 1.00 (referent) | 49/518 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| 2nd quartile | 9/503 | 0.68 (0.29–1.60) | 36/503 | 0.96 (0.59–1.57) | 15/506 | 0.65 (0.32–1.35) | 69/506 | 1.31 (0.88–1.96) | |||

| 3rd quartile | 16/524 | 1.18 (0.56–2.51) | 59/524 | 1.51 (0.97–2.36) | 9/512 | 0.35 (0.14–0.86) | 51/512 | 0.93 (0.60–1.45) | |||

| 4th quartile | 11/515 | 1.09 (0.48–2.50) | 104/515 | 2.61 (1.71–3.99) | 7/516 | 0.23 (0.08–0.68) | 66/516 | 1.11 (0.70–1.77) | |||

| Ptrend | 0.57 | <0.0001 | 0.004 | 0.94 | |||||||

| AR | Total | 301/2052 | 105/2052 | 0.07 | 301/2052 | 105/2052 | 0.03 | ||||

| 1st quartile | 67/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 22/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 123/518 | 1.00 (referent) | 37/518 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| 2nd quartile | 76/503 | 1.11 (0.78–1.59) | 16/503 | 0.73 (0.38–1.43) | 82/506 | 0.64 (0.47–0.89) | 25/506 | 0.67 (0.39–1.16) | |||

| 3rd quartile | 78/524 | 1.10 (0.77–1.58) | 30/524 | 1.36 (0.76–2.43) | 54/512 | 0.39 (0.27–0.57) | 18/512 | 0.46 (0.25–0.86) | |||

| 4th quartile | 80/515 | 1.25 (0.87–1.82) | 37/515 | 1.88 (1.06–3.34) | 42/516 | 0.27 (0.17–0.43) | 25/516 | 0.62 (0.33–1.19) | |||

| Ptrend | 0.26 | 0.004 | <0.0001 | 0.15 | |||||||

| EGFR | Total | 48/2052 | 249/2052 | 0.001 | 48/2052 | 249/2052 | 0.009 | ||||

| 1st quartile | 13/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 38/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 16/518 | 1.00 (referent) | 51/518 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| 2nd quartile | 11/503 | 0.84 (0.37–1.92) | 32/503 | 0.83 (0.51–1.37) | 18/506 | 1.05 (0.51–2.15) | 70/506 | 1.26 (0.85–1.87) | |||

| 3rd quartile | 13/524 | 1.03 (0.46–2.31) | 69/524 | 1.71 (1.11–2.62) | 6/512 | 0.36 (0.13–0.99) | 58/512 | 0.98 (0.64–1.50) | |||

| 4th quartile | 11/515 | 1.18 (0.51–2.74) | 110/515 | 2.72 (1.80–4.11) | 8/516 | 0.45 (0.16–1.25) | 70/516 | 1.09 (0.69–1.71) | |||

| Ptrend | 0.58 | <0.0001 | 0.05 | 0.92 | |||||||

| VEGF | Total | 145/2052 | 37/2052 | 0.17 | 145/2052 | 37/2052 | 0.09 | ||||

| 1st quartile | 35/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 11/510 | 1.00 (referent) | 70/518 | 1.00 (referent) | 22/518 | 1.00 (referent) | |||

| 2nd quartile | 47/503 | 1.41 (0.88–2.25) | 7/503 | 0.52 (0.20–1.40) | 40/506 | 0.57 (0.37–0.89) | 10/506 | 0.52 (0.22–1.20) | |||

| 3rd quartile | 46/524 | 1.28 (0.80–2.06) | 9/524 | 0.66 (0.26–1.67) | 23/512 | 0.29 (0.17–0.51) | 4/512 | 0.20 (0.06–0.66) | |||

| 4th quartile | 17/515 | 0.64 (0.35–1.18) | 10/515 | 1.00 (0.40–2.53) | 12/516 | 0.13 (0.06–0.28) | 1/516 | 0.05 (0.01–0.43) | |||

| Ptrend | 0.10 | 0.69 | <0.0001 | 0.0005 | |||||||

Abbreviations: AR=androgen receptor; CI=confidence interval; CK5/6=cytokeratins 5/6; EGFR=epidermal growth factor receptor; ER=oestrogen receptor; HER2=human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; Ki67=proliferation marker; OR=odds ratio; PR=progesterone receptor; SE=standard error; VEGF=vascular endothelial growth factor.

Polychotomous multivariable logistic regression model adjusted for age (continuous), body mass index (continuous), age at menarche (<12, 12, 13, or >13 years), parity and age at first birth (nulliparous, 1–4 children with age at first birth <25 years, 1–4 children with age at first birth of 25–29 years, 1–4 children with age at first birth of ≥30 years, ≥5 children with age at first birth of <25 years, or ≥5 children with age at first birth of ≥25 years), age at menopause (<46, 46–<50, 50–<55, ≥55, unknown), postmenopausal hormone use (never, ever, unknown), family history (yes or no), confirmed history of benign breast disease (yes or no), alcohol consumption (0, <5, 5 to <15, or ≥15 g per day), and NHS cohort (NHS II vs NHS I). Quartiles are defined as follows: absolute dense area: 1st: <19 cm2, 2nd: 19–<35 cm2, 3rd: 35–<61 cm2; 4th: ≥61 cm2; non-dense area: 1st: <83 cm2, 2nd: 83–<138 cm2, 3rd: 138–<208 cm2; 4th: ≥208 cm2.

P-values for the test of heterogeneity of odds ratios were calculated using a two-sided likelihood ratio test.

In the analysis by AR, CK5/6, and EGFR, the differences in subset-specific associations were significant for CK5/6 (Pheterogeneity=0.002) and EGFR (Pheterogeneity=0.001) and were marginally significant for AR (Pheterogeneity=0.07).

Associations of absolute dense area with Ki67+ and Ki67− tumours were similar. Absolute dense area was not associated with the risk of breast cancer subtypes defined by VEGF status.

Non-dense area

In the analyses by tumour ER and PR status, non-dense breast area was inversely associated with breast cancer risk in both marker-positive and marker-negative tumours (Table 4). The magnitude of the association was stronger in ER− (4th vs 1st quartile OR=0.26, 95% CI 0.14–0.46) as compared with ER+ tumours (OR=0.60, 95% CI 0.45–0.80; Pheterogeneity<0.0001). In the additional analysis comparing ER+/PR+ and ER−/PR− tumours, the association of percent density was stronger in ER−/PR− tumours (4th quartile vs 1st quartile: OR=0.30, 95% CI 0.16–0.56 vs OR=0.56, 95% CI 0.41–0.77, Pheterogeneity=0.0073).

The difference in the associations of non-dense area with breast cancer in Ki67+ and Ki67− tumours did not reach statistical significance, but the risk estimates suggested a possible stronger inverse association in Ki67− tumours (4th vs 1st quartile OR=0.44 for Ki67+ and OR=0.26 for Ki67− tumours). The association between non-dense area and breast cancer risk was stronger in AR+ (4th vs 1st quartile OR=0.27, 95% CI 0.17–0.43) as compared with AR− tumours (OR=0.62, 95% CI 0.33–1.19, Pheterogeneity=0.03). We found significant differences in the association of non-dense area with breast cancer by status of CK5/6 and EGFR (Pheterogeneity=0.005 and 0.009, respectively) (Table 4). In the analyses by tumour's PR, HER2, and VEGF status, the inverse associations of non-dense breast area with breast cancer risk were similar.

In an additional analysis, we mutually adjusted the risk estimates for absolute dense and non-dense areas by including both of the density measures in the model simultaneously. The risk estimates for both absolute dense area and non-dense area remained essentially unchanged suggesting independent nature of the observed associations (data not shown). We found no correlation between absolute dense are and non-dense area (correlation coefficient=0.02).

In secondary analyses, we excluded women diagnosed with breast cancer within 2 years of their mammogram from the current analysis; the results were not affected. We also used ASCO/CAP clinical definition of HER2 positivity (as 3+ membrane staining as opposed to 2+, 1+ or none) in additional analysis by HER2 status; the results were similar (data not shown). Finally, the results for all three density measures were similar when the analysis was restricted to invasive cancers only (data not shown).

Discussion

In this nested case-control study, we investigated the associations of percent breast density, absolute dense area, and non-dense area with breast cancer risk according to the status of selected tissue markers among 1010 postmenopausal breast cancer cases and 2077 matched controls. The strength of the associations of absolute dense area and non-dense area with breast cancer risk varied by ER, CK5/6, AR, and EGFR status. Stronger positive associations were noted for absolute dense area and CK5/6− and EGFR− tumours. Stronger inverse associations of non-dense area with breast cancer risk were observed in ER−, AR+, CK5/6+, and EGFR+ tumours. We did not find differences in the associations of density measures with breast cancer risk according to the status of other markers.

We have previously reported a stronger association of percent breast density with ER− tumours (Yaghjyan et al, 2011, Bertrand et al, 2013). Similar to our previous results, we observed suggestive stronger associations in ER− than ER+ tumours with percent density, though this difference did not reach statistical significance. Findings on the association of breast density with receptor status of the tumour from previous studies are inconsistent (Yaghjyan et al, 2011, Antoni et al, 2013, Pollan et al, 2013), although one of the largest studies to date showed a stronger association of percent density with ER− than ER+ breast cancer among younger women (Bertrand et al, 2013). Our findings suggest that regulatory factors other than oestrogen may play an important role in the origins of ER− tumours in denser breasts. Finally, it appears that this association is being driven in large part by non-dense area rather than absolute dense area.

We found a stronger inverse association between non-dense breast area and ER− tumours compared with ER+ tumours. Similarly, a recent pooled analysis of 4095 breast cancers and 8558 controls have reported a stronger inverse association of non-dense area with ER− tumours among younger women (age <55 years) (Bertrand et al, 2015). As recently discussed, non-dense area that represents breast adipose tissue may influence breast cancer risk through both direct and indirect mechanisms (Pettersson and Tamimi, 2012). The stronger inverse association observed for ER− tumours, suggests that breast adipose tissue (as measured by non-dense area) could be reducing risk through non-oestrogen mediated pathways.

We describe, for the first time, a stronger positive association of absolute dense area with CK5/6−, EGFR−, and AR− tumours, and stronger inverse associations of non-dense area with CK5/6+, EGFR+, and AR+ tumours. The association patterns observed in our study could only in part be explained by the moderate positive correlations of ER with AR and inverse correlations with EGFR. It has been suggested that the amount of stromal matrix and glandular elements and their interaction with each other are implicated in breast carcinogenesis (Shepherd and Kerlikowske, 2012). On the other hand, expression of certain tissue markers could be reflective of the tissue composition. Thus, in the studies investigating associations of breast density with molecular subtypes of breast cancer absolute dense and non-dense areas appear to be more relevant density measures that would allow detection of differences in subtype-specific associations. As CK5/6 and EGFR are predominantly expressed in stromal and epithelial cells, the protective effect of non-dense tissue on CK5/6+ and EGFR+ subtypes could be the result of interaction between fibroglandular and adipose elements in the breast tissue. The underlying biological mechanisms by which absolute dense and non-dense areas could differentially affect the risk of specific molecular subtypes of breast cancer yet need to be elucidated.

To our knowledge, this is the first large study to investigate the association of three quantitative measures of breast density with several tissue markers. The analysis used data from the NHS, an established cohort with more than 30 years of follow-up, disease status ascertainment, and comprehensive information on breast cancer risk factors, tumour characteristics, and breast density. The current analysis was restricted to women who were postmenopausal at the time of both mammogram and diagnosis, which constitutes the majority of the population assembled for the nested case-control study (62%). Our findings are thus limited to postmenopausal breast cancer subtypes and do not necessarily apply to premenopausal breast cancer. In addition, we did not investigate the associations between breast density and breast cancer risk by combined ER/PR/HER2 status or by combined CK5/6/EGFR status because the small numbers of tumours in the subsets did not provide sufficient statistical power to draw meaningful conclusions. Finally, as the marker data for Ki67, AR, CK5/6, EGFR, and VEGF were available on a small subset of cases, these exploratory findings should be interpreted with caution.

Breast cancer is a heterogeneous disease. Previous studies suggested aetiological heterogeneity of ER+ and ER− tumours (Colditz et al, 2004, Rusiecki et al, 2005, Yang et al, 2007, Kwan et al, 2009). Some recent studies suggest that clinical outcomes and patient survival can differ by tumour CK5/6, EGFR, VEGF, and AR status (Collins et al, 2011, Dawood et al, 2011, Hu et al, 2011, Liu et al, 2011). While expression of CK5/6, EGFR, and VEGF involved in cellular proliferation, differentiation, and angiogenesis has been linked to a more aggressive tumour phenotype and poorer survival, AR+ tumours seem to have more favourable outcomes (Collins et al, 2011, Hu et al, 2011), perhaps due to the inhibition of growth of breast cancer cells through the androgen signalling pathway (Birrell et al, 2007). Identifying risk factors specific to certain molecular subtypes of breast tumours would help researchers to understand the aetiology of those breast cancer subtypes and develop subtype-specific risk prediction models.

In conclusion, we investigated the association of breast density with tissue marker-defined breast cancer subtypes in postmenopausal women. Our results suggest that breast density influences the risk of breast cancer subtypes by potentially different mechanisms. Further studies are warranted to explain underlying biological processes and elucidate the possible pathways from high breast density to the specific subtypes of breast carcinomas.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses' Health Study (NHS) and the Nurses' Health Study II (NHS II) cohorts for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, and WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA131332, CA 124685 to RMT, CA087969, UM1CA186107 to M.S., UM1CA176726 to W.W., R01 CA 140286 to C.V.); AVON Foundation for Women (to RMT); Susan G. Komen For the Cure (to RMT); and the American Cancer Society (to GAC).

Author contributions

GAC, RMT, and LY designed the study. LCC, SJS, and AHB assessed tissue markers. LY, RMT, GAC, and BR analysed the data and LY performed the statistical analyses. LY and RMT wrote the manuscript with final approval from all authors.

GAC has advisory role with Orion Genomics and royalties from UpToDate. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on British Journal of Cancer website (http://www.nature.com/bjc)

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License.

Supplementary Material

References

- Antoni S, Sasco AJ, dos Santos Silva I, McCormack V (2013) Is mammographic density differentially associated with breast cancer according to receptor status? A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137: 337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arpino G, Bardou VJ, Clark GM, Elledge RM (2004) Infiltrating lobular carcinoma of the breast: tumor characteristics and clinical outcome. Breast Cancer Res 6: R149–R156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand K, Eliassen AH, Hankinson S, Gierach G, Xu X, Rosner B, Ziegler R, Tamimi R (2012) Urinary estrogens and estrogen metabolites and mammographic density in premenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 136: 277–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand KA, Scott CG, Tamimi RM, Jensen MR, Pankratz VS, Norman AD, Visscher DW, Couch FJ, Shepherd J, Chen Y-Y, Fan B, Wu F-F, Ma L, Beck AH, Cummings SR, Kerlikowske K, Vachon CM (2015) Dense and nondense mammographic area and risk of breast cancer by age and tumor characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24(5): 798–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand KA, Tamimi RM, Scott CG, Jensen MR, Pankratz VS, Visscher D, Norman A, Couch F, Shepherd J, Fan B, Chen YY, Ma L, Beck AH, Cummings SR, Kerlikowske K, Vachon CM (2013) Mammographic density and risk of breast cancer by age and tumor characteristics. Breast Cancer Res 15: R104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell SN, Butler LM, Harris JM, Buchanan G, Tilley WD (2007) Disruption of androgen receptor signaling by synthetic progestins may increase risk of developing breast cancer. FASEB J 21: 2285–2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd NF, Byng JW, Jong RA, Fishell EK, Little LE, Miller AB, Lockwood GA, Tritchler DL, Yaffe MJ (1995) Quantitative classification of mammographic densities and breast cancer risk: results from the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 670–675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byng JW, Boyd NF, Little L, Lockwood G, Fishell E, Jong RA, Yaffe MJ (1996) Symmetry of projection in the quantitative analysis of mammographic images. Eur J Cancer Prev 5: 319–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne C, Schairer C, Wolfe J, Parekh N, Salane M, Brinton LA, Hoover R, Haile R (1995) Mammographic features and breast cancer risk: effects with time, age, and menopause status. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 1622–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheang MCU, Chia SK, Voduc D, Gao D, Leung S, Snider J, Watson M, Davies S, Bernard PS, Parker JS, Perou CM, Ellis MJ, Nielsen TO (2009) Ki67 index, HER2 status, and prognosis of patients with luminal B breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 101: 736–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Hankinson SE (2005) The Nurses' Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer 5: 388–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Chen WY, Holmes MD, Hankinson SE (2004) Risk factors for breast cancer according to estrogen and progesterone receptor status. J Natl Cancer Inst 96: 218–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LC, Cole KS, Marotti JD, Hu R, Schnitt SJ, Tamimi RM (2011) Androgen receptor expression in breast cancer in relation to molecular phenotype: results from the Nurses' Health Study. Mod Pathol 24: 924–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawood S, Hu R, Homes MD, Collins LC, Schnitt SJ, Connolly J, Colditz GA, Tamimi RM (2011) Defining breast cancer prognosis based on molecular phenotypes: results from a large cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 126: 185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefti MM, Hu R, Knoblauch NW, Collins LC, Haibe-Kains B, Tamimi RM, Beck AH (2013) Estrogen receptor negative/progesterone receptor positive breast cancer is not a reproducible subtype. Breast Cancer Res 15: R68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu R, Dawood S, Holmes MD, Collins LC, Schnitt SJ, Cole K, Marotti JD, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA, Tamimi RM (2011) Androgen receptor expression and breast cancer survival in postmenopausal women. Clin Cancer Res 17: 1867–1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan M, Kushi L, Weltzien E, Maring B, Kutner S, Fulton R, Lee M, Ambrosone C, Caan B (2009) Epidemiology of breast cancer subtypes in two prospective cohort studies of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res 11: R31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Tamimi R, Collins L, Schnitt S, Gilmore H, Connolly J, Colditz G (2011) The association between vascular endothelial growth factor expression in invasive breast cancer and survival varies with intrinsic subtypes and use of adjuvant systemic therapy: results from the Nurses' Health Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 129: 175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I (2006) Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15: 1159–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson A, Graff RE, Ursin G, Santos Silva ID, McCormack V, Baglietto L, Vachon C, Bakker MF, Giles GG, Chia KS, Czene K, Eriksson L, Hall P, Hartman M, Warren RM, Hislop G, Chiarelli AM, Hopper JL, Krishnan K, Li J, Li Q, Pagano I, Rosner BA, Wong CS, Scott C, Stone J, Maskarinec G, Boyd NF, van Gils CH, Tamimi RM (2014) Mammographic density phenotypes and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 106: pii dju078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson A, Hankinson SE, Willett WC, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Tamimi RM (2011) Nondense mammographic area and risk of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 13: R100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson A, Tamimi RM (2012) Breast fat and breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 135: 321–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps AI, Li CI, Kerlikowske K, Barlow WE, Buist DS (2010) Risk factors for ductal, lobular, and mixed ductal-lobular breast cancer in a screening population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19: 1643–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollan M, Ascunce N, Ederra M, Murillo A, Erdozain N, Ales-Martinez J, Pastor-Barriuso R (2013) Mammographic density and risk of breast cancer according to tumor characteristics and mode of detection: a Spanish population-based case-control study. Breast Cancer Res 15: R9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putti TC, El-Rehim DM, Rakha EA, Paish CE, Lee AH, Pinder SE, Ellis IO (2005) Estrogen receptor-negative breast carcinomas: a review of morphology and immunophenotypical analysis. Mod Pathol 18: 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner B, Glynn RJ, Tamimi RM, Chen WY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Hankinson SE (2013) Breast cancer risk prediction with heterogeneous risk profiles according to breast cancer tumor markers. Am J Epidemiol 178: 296–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusiecki JA, Holford TR, Zahm SH, Zheng T (2005) Breast cancer risk factors according to joint estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor status. Cancer Detect Prev 29: 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd JA, Kerlikowske K (2012) Do fatty breasts increase or decrease breast cancer risk? Breast Cancer Res 14: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamimi RM, Baer HJ, Marotti J, Galan M, Galaburda L, Fu Y, Deitz AC, Connolly JL, Schnitt SJ, Colditz GA, Collins LC (2008) Comparison of molecular phenotypes of ductal carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 10: R67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamimi RM, Byrne C, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE (2007) Endogenous hormone levels, mammographic density, and subsequent risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst 99: 1178–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett W, Stampfer MJ, Bain C, Lipnick R, Speizer FE, Rosner B, Cramer D, Hennekens CH (1983) Cigarette smoking, relative weight, and menopause. Am J Epidemiol 117: 651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghjyan L, Colditz GA, Collins LC, Schnitt SJ, Rosner B, Vachon C, Tamimi RM (2011) Mammographic breast density and subsequent risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women according to tumor characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst 103: 1179–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XR, Sherman ME, Rimm DL, Lissowska J, Brinton LA, Peplonska B, Hewitt SM, Anderson WF, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Bardin-Mikolajczak A, Zatonski W, Cartun R, Mandich D, Rymkiewicz G, Ligaj M, Lukaszek S, Kordek R, Garcia-Closas M (2007) Differences in risk factors for breast cancer molecular subtypes in a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 16: 439–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.