Abstract

Primary carcinoma of the vagina is rare, accounting for 1–3% of all gynaecological malignancies. MRI has an increasing role in diagnosis, staging, treatment and assessment of complications in gynaecologic malignancy. In this review, we illustrate the utility of MRI in patients with primary vaginal cancer and highlight key aspects of staging, treatment, recurrence and complications.

The incidence of primary vaginal cancer increases with age, with approximately 50% of patients presenting at age greater than 70 years and 20% greater than 80 years.1 Around 2890 patients are currently diagnosed with vaginal carcinoma in the USA each year, and almost 30% die of the disease.2 The precursor for vaginal cancer, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN) and invasive vaginal cancer is strongly associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection (93%).3,4 In situ and invasive vaginal cancer share many of the same risk factors as cervical cancer, such as tobacco use, younger age at coitarche, HPV and multiple sexual partners.5–7 In fact, higher rates of vaginal cancer are observed in patients with a previous diagnosis of cervical cancer or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.7,8

As is true for other gynaecologic malignancies, vaginal cancer diagnosis and staging rely primarily on clinical evaluation by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).9 Pelvic examination continues to be the most important tool for evaluating local extent of disease, but this method alone is limited in its ability to detect lymphadenopathy and the extent of tumour infiltration. Hence, FIGO encourages the use of imaging. Fluorine-18 fludeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET), a standard imaging tool for staging and follow-up in cervical cancer, can also be used for vaginal tumours, with improved sensitivity for nodal involvement compared to CT alone.10 In addition to staging for nodal and distant disease, CT [simulation with three dimensional (3D) conformations] is particularly useful for treatment planning and delivery of external beam radiation. MRI, with its excellent soft tissue resolution, is commonly used in gynaecologic malignancies and has been shown to be accurate in diagnosis, local staging and spread of disease in vaginal cancer.11,12 While no formal studies are available for vaginal cancer, in cervical cancer MRI actually alters the stage in almost 30% of patients.13–15

Treatment planning in primary vaginal cancer is complex and requires a detailed understanding of the extent of disease. Because vaginal cancer is rare, treatment plans remain less well defined, often individualized and extrapolated from institutional experience and outcomes in cervical cancer.1,16–19 There is an increasing trend towards organ preservation and treatment strategies based on combined external beam radiation and brachytherapy, often with concurrent chemotherapy,14,20,21 surgery being reserved for those with in situ or very early-stage disease.22 Increasing utilization of MR may provide superior delineation of tumour volume, both for initial staging and follow-up, to allow for better treatment planning.23

ANATOMY

The vagina is a 3- to 4- inch fibromuscular tube extending from the lower aspect of the cervix to the vulva, situated behind the urethra and bladder and in front of the rectum. The vagina is divided into three segments, important for classifying tumour location and lymphatic drainage (Figure 1). The lower third is below the level of the bladder base with the urethra anteriorly. The middle third is adjacent to the bladder base, and the upper third at the level of the vaginal fornices. The vaginal fornices are denoted as anterior, posterior and lateral with respect to the cervix (Figure 1).

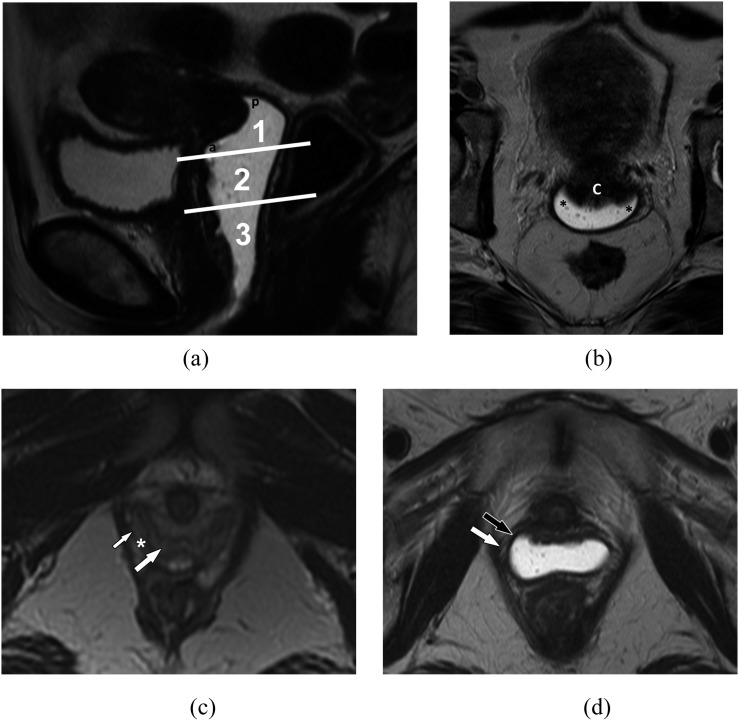

Figure 1.

Anatomy of the vagina. (a) Anatomic division into segments. Sagittal T2 weighted MR image delineates the three anatomic divisions of the vagina: (1) upper third, (2) middle third and (3) lower third. Within the upper third of the vagina, the anterior (labelled a) and posterior (labelled p) fornices can be seen. (b) Axial T2 weighted MR image delineates the lateral vaginal fornices (asterisk) separated by the cervix, denoted with a c. (c) Vagina without gel. Axial T2 weighted image shows three layers of the vaginal wall: the mucosa (large white arrow), the muscularis and submucosa (asterisk) and the adventitia (small white arrow). (d) Vagina with gel. Axial T2 weighted image shows only two appreciable layers of the vaginal wall: the muscularis and submucosa (black arrow) and the adventitia (white arrow).

Lymph node drainage is important as vaginal cancer commonly involves lymph nodes even in early-stage disease, with reported rates 6–14% for Stage I and 26–32% for Stage II disease.24,25 Moreover, inguinal lymph node involvement has been implicated in aggressive tumour behaviour and lower rates of survival.26 Theoretically, the upper third of the vagina drains into the external iliac and para-aortic chain, the middle third into the common and internal iliac chains and the lower third into the superficial inguinal, femoral and perirectal nodal chains. However, these ascribed patterns of lymphatic drainage are highly variable and unreliable; hence, in patients undergoing surgery, sentinel lymph node mapping can be performed prior to lymph node dissection.21

PATHOLOGY

The most common tumour of the vagina is metastasis. Primary vaginal cancer, though, has two major histopathology types: squamous cell carcinoma (80%) and adenocarcinoma (15%). Melanoma, lymphoma and sarcoma are highly unusual, comprising the remaining 5%.1,27 Squamous cell carcinoma arises from the vaginal mucosa, which is composed of oestrogen-sensitive stratified squamous epithelium. It is more common in postmenopausal females (median age, 60 years) and frequently involves the proximal third of the vagina.12 Squamous cell carcinoma can also be multifocal when developing in a background of VAIN and has been reported in vulvovaginal lichen planus.28 Adenocarcinoma, unlike squamous cell carcinoma, commonly affects younger patients (median age, 19 years) and is more likely to metastasize to the lungs and lymph nodes.5 One subtype, clear cell adenocarcinoma, is classically associated with in utero exposure to diethylstilboestrol and is found in 2% of exposed females.29 The staging and treatment of vaginal cancer in this review will focus on squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma, the two most common histologic types.

CLINICAL STAGING AND PROGNOSIS

Vaginal cancer is staged and classified according to guidelines of the FIGO and the American Joint Committee on Cancer.9 The FIGO system is most commonly used and is summarized in Table 1.9 According to FIGO, tumours involving the cervix and vulva are considered cervical and vulvar malignancies, respectively, regardless of whether the epicentre of the tumour is in the vagina.

Table 1.

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging of vaginal cancer

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ, intraepithelial carcinomaa |

| Stage I | Confined to the vagina |

| Stage II | Involvement of paravaginal tissue but not pelvic sidewall |

| Stage III | Extension to pelvic sidewall |

| Stage IV | Extension beyond true pelvis or bladder and/or rectal involvement |

| IVA | –Extension beyond pelvis, bladder or rectal invasion |

| IVB | –Distant organ metastases |

Compiled from FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology staging information.9

No current role for imaging.

Prognosis correlates strongly with stage of disease. Relative 5-year survival in larger series range from 96% for Stage 0, 64–84% for Stage I, 53–58% for Stage II, 36% for Stage III and 18–36% for Stage IV.16,30 In patients treated with definitive radiation, cause-specific survival ranges from 40 to 92% for Stage I, 35 to 78% for Stage II, 23 to 59% for Stage III and 0 to 25% for Stage IV.16,31–37 Factors negatively associated with survival include advanced stage, larger tumour size, lower and middle vaginal tumours and older age (greater than 60 years), though tumour position has conflicting evidence.25,31,38–40 Recent studies have found that age, FIGO stage and MIB-1 are the primary independent prognostic factors for 5-year disease-free survival.41 MIB-1 index, or tumour expression of the proliferation-associated antigen Ki-67, is an immunocytochemical marker of mitotic rate and has been shown to be important in other gynaecologic cancers, specifically endometrial and cervical cancers.30,42,43

Histologic type and primary tumour characteristics are also predictive of survival. For females with squamous cell carcinoma, 5-year survival is approximately 54%. For adenocarcinoma overall, survival is similar at 60%, though significantly lower for those with non-diethylstilbestrol-associated adenocarcinoma, 34%.44 Vaginal melanoma, however, has much lower 5-year survival at 13%.45 With regard to the primary tumour, tumours >4 cm, tumour ulceration and tumour infiltration into the rectovaginal septum are associated with significantly poorer prognosis compared with smaller exophytic tumours.26 Tumour grade, however, had been shown to correlate with the development of distant metastases but not local disease.34

MRI TECHNIQUE AND STAGING

MRI technique

MRI of the pelvis for vaginal cancer is similar to that for cervical cancer. The patient should be imaged supine with a torso- or pelvic-phased array coil. At some institutions, glucagon can be administered to decrease artefacts from bowel peristalsis. A partially filled bladder also helps displace bowel loops out of the pelvis. The utilization of a dry tampon or vaginal gel (Surgilube, Fougera; Melville, NY) provides better distension and visualization of the vagina, although not universally used.46 For optimal tumour assessment, instillation of a dry tampon or vaginal gel into the vagina prior to the MR may be helpful (Figure 1).

Suggested guidelines from our institution, a dedicated cancer hospital, are as follows and summarized in Table 2. On a 1.5-T magnet, T1 weighted images using a spin-echo pulse sequence with repetition time (TR) of 400–500 ms, echo time (TE) of 12 ms and k-space matrix size 256 × 192 in axial planes are obtained. Coronal T2 weighted single shot fast spin echo images should include the kidneys to evaluate for hydronephrosis. T2 weighted fast spin-echo images with a small field of view (24 cm) with thin sections (thickness, 5 mm; interslice gap, 0 mm) are acquired with TR 4000–6000 ms, TE 100–120 ms, in axial and sagittal planes. 3D dynamic gadolinium-enhanced images are acquired in a sagittal plane with a temporal resolution of 12 s, gradient echo TR 4.1 ms and TE 1.5 ms and matrix 320 × 200 with thin sections (thickness, 2 mm; no interslice gap, 1 signal average) over a period of 9 min.

Table 2.

MRI parameters for gynaecologic pelvisa

| Parameter | Cor SSFSE or haste | Ax T1 fast spin echo | Ax T2 fast spin echo | Sag T2 fast spin echo | 3D Sag fat saturation dynamicb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repetition time (ms) | 2000 | 400–500 | 4000–6000 | 4000–6000 | 3.9–4.1 |

| Echo time (ms) | 102–140 | 10–12 | 100–120 | 100–120 | 1.5 |

| Flip angle (°) | 167 | 158 | 152 | 160 | 15 |

| Field of view (mm) | 340–440 | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 5 | 4–5 | 4–5 | 4–5 | 2–3 |

| Acquisition matrix | 256 × 160 | 256 × 192 | 384 × 224 | 512 × 256 | 320 × 192 |

| Signal averages | 1 | 2–3 | 3 | 3–4 | 1–2 |

| Bandwidth (Hz per pixel) | 698 | 178 | 200 | 199 | 410 |

| Dimension (two dimensional/3D) | 2D | 2D | 2D | 2D | 3D |

3D, three dimensional; Ax, axial; Cor, coronal; SSFSE, single-shot fast spin-echo.

Suggested guidelines for MRI of the gynaecologic pelvis using a 1.5 T.

Includes precontrast, followed by dynamic postintravenous contrast acquisitions.

On MRI, the three layers of the vaginal wall can be appreciated on T2 weighted images, similar to the zonal anatomy of the uterus: the mucosa is hyperintense, the submucosal (consisting of collagen and elastic fibres) and muscularis layer hypointense, and the adventitia hyperintense due to a well-developed venous plexus (Figure 1).47 With the use of vaginal gel, only two layers are evident, the hypointense muscularis and the hyperintense adventitia; the hyperintense mucosal layer is obscured by the hyperintense gel (Figure 1). The tumour itself is best assessed on T2 weighted images, where it is of intermediate to high signal intensity relative to the submucosal and muscularis layer, which creates the hypointense peripheral band of the vaginal wall. Similar to cervical cancer, extension through the hypointense muscularis is important in staging. T2 weighted images optimize tumour contrast from adjacent structures (bladder and rectal wall) and extension through the low-signal vaginal wall.48

A fat-suppressed T1 weighted sequence before and after administration of intravenous gadolinium can be utilized to assess tumour enhancement, particularly in evaluating recurrence and/or in patients who have received prior radiation. While no dedicated studies have been carried out on vaginal cancer, studies in cervical and endometrial cancer have shown that dynamic contrast enhancement may be helpful in differentiating tumour type (squamous vs adenocarcinoma), evaluating extent of tumour invasion/involvement, and distinguishing recurrence from fibrosis in treated patients.49–51 Tumour recurrence, however, can often be detected on T2 weighted images; typically, the tumour has a higher signal intensity compared with fibrosis, which has a low signal on the T2 weighted images.52 Kinkel et al51 showed that the use of dynamic contrast-enhanced MR images in cervical cancer increased specificity, accuracy, positive and negative-predictive values from 22%, 68%, 70% and 57% to 67%, 83%, 86% and 86%, respectively. We believe that the addition of contrast administration and dynamic imaging may have a similar value in vaginal cancer, both for initial staging and follow-up. The use of diffusion-weighted imaging is promising and has shown potential for improving tumour detection in cervical cancer,53,54 but its current role in vaginal cancer is unknown.

MR staging

Table 3 highlights MRI findings by stage and key imaging sequences.

Table 3.

MR staging of vaginal cancer

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Stage I | Preservation of low-signal vaginal wall on T2 weighted images (axiala) |

| Stage II | Disruption of low-signal vaginal wall on T2 weighted images (axiala); extension into the parametrial fat on T1 or T2 weighted images (axiala) |

| Stage III | Extension to pelvic sidewall; abnormally high signal of the musculature on T2 weighted images |

| Stage IV | Extension beyond the true pelvis or bladder and/or rectal involvement |

| IVA | –Extension beyond the pelvis or bladder or rectal invasion; disruption of the low-signal bladder or rectal wall on T2 weighted images or abnormal enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images with fat suppression |

| IVB | –Distant organ metastases (lungs and liver) |

MR image planes that may be the most helpful.

Stage I

For Stage I, tumour is limited to the vagina and has not extended into the paravaginal fat (Figure 2). On T2 weighted images, the normal low T2 signal of the vaginal wall (submucosal and muscularis) is intact (Figure 2b). This is analogous to the preservation of the T2 hypointense fibromuscular stromal ring in cervical cancer, which has documented accuracy of 88–97% and a negative-predictive value of 94–100% on MRI.55–57

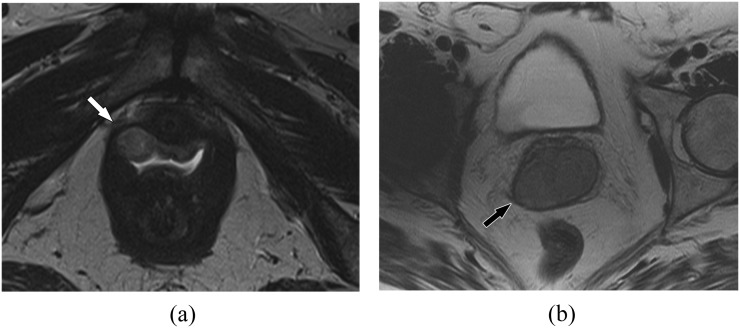

Figure 2.

Stage I vaginal cancer. (a) A 62-year-old female with Stage I vaginal cancer. Axial T2 weighted MR image shows a small mildly hyperintense mass confined to the right anterolateral vagina (arrow). (b) A 79-year-old female with Stage I vaginal cancer. Axial T2 weighted MR image shows a larger Stage I tumour confined to the vagina with an intact low T2 signal vaginal wall (muscularis) around the tumour (arrow). Biopsy confirmed squamous cell carcinoma.

Stage II

In Stage II, the low T2 signal intensity of the vaginal wall is disrupted by the extension of tumour into the paravaginal fat (Figure 3). Similar to tumour detection in cervical cancer, axial images, perpendicular to the orientation of the vagina, are best for evaluating local spread beyond the vaginal wall. In cervical cancer, large or bulky tumours may result in the loss of the hypointense T2 signal of the vaginal stroma and may mimic parametrial invasion; we suspect that this is also true and advise similar caution when assessing large or bulky vaginal tumours.57

Figure 3.

A 57-year-old female with Stage II vaginal cancer. Axial T2 weighted MR image shows the mass involving the paravaginal tissues (black arrow). The low T2 signal vaginal muscularis is completely disrupted by tumour bilaterally. Biopsy confirmed squamous cell carcinoma.

Stage III

In Stage III, tumour extends locally to the pelvic sidewall (Figure 4a). Pelvic sidewall involvement is generally defined as tumour spread within 3 mm of the internal obturator, levator ani or piriformis muscles or iliac vessels.58 On T2 weighted images, one can observe abnormal signal with increased T2 signal related to oedema or direct invasion of the tumour into the musculature itself (Figure 4b). Tethering of the musculature is also sometimes observed. In tumours with paravaginal and pelvic sidewall extension, evaluation of the coronal T2 weighted images is particularly important to evaluate the kidneys for hydronephrosis.

Figure 4.

Vaginal cancer, pelvic sidewall involvement. (a) A 45-year-old female with Stage III vaginal cancer. Axial T2 weighted MR image shows infiltrative mass at the vaginal fornix extending into the left pelvic sidewall (white arrow), involving the piriformis and the sciatic region. Biopsy confirmed poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. (b) A 53-year-old female with Stage IV vaginal cancer. Axial T2 weighted MR image shows infiltrative vaginal mass extending into the left pelvic sidewall (black arrow). Note the T2 hyperintensity reflecting oedema within the obturator internus muscle (white arrow). Urethral involvement in this patient, however, established Stage IV disease.

Stage IV

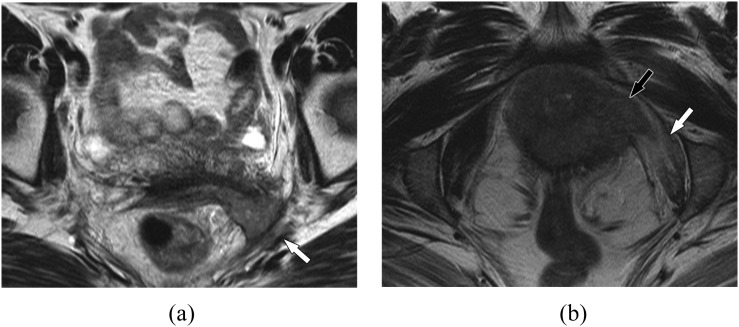

For Stage IV, tumour extends beyond the true pelvis or may invade the bladder or rectum (Figures 5 and 6). Stage IV has been divided into Stage IVA, disease that has directly spread beyond the true pelvis and/or invaded the rectum or bladder, and Stage IVB, disease with distant metastases. MRI has high accuracy for detecting the bladder and rectal invasion, ranging from 96% to 99% with an excellent negative predictive value and interobserver agreement.48,59–61 T2 weighted images are important for evaluating loss of the fat planes and loss of normal low-signal intensity of the bladder or rectal wall (Figures 5 and 6).62 In addition to abnormal T2 signal, contour abnormality such as irregularity and nodularity along the wall is also suspicious for invasion.48 When suspecting invasion, evaluating an additional imaging plane is often helpful to verify the presence or absence of invasion (Figure 5b,c). Contrast-enhanced T1 weighted images may improve accuracy. The presence of abnormal enhancement of the bladder or rectal wall or direct extension of soft tissue into the bladder or rectum is the sign of invasion on contrast-enhanced images.63 In general, MRI can overstage bladder involvement as it is difficult to differentiate peritumoural oedema (bullous oedema) and inflammation from tumour infiltration; correlation with cystoscopy is suggested for confirmation in cases of suspected invasion.12 Given the close proximity to the bladder and urethra anteriorly and the rectum posteriorly, invasion into the lower aspect of these structures may result in bladder outlet obstruction and urinary retention (Figure 5a) or rectal symptoms, respectively.

Figure 5.

Vaginal cancer, assessing bladder invasion. (a) A 60-year-old female with Stage IV vaginal cancer. Sagittal T2 weighted MR image shows infiltrative vaginal mass involving the urethra and bladder base (arrow). Note the markedly distended bladder (asterisk) related to bladder outlet obstruction. Biopsy confirmed squamous cell carcinoma. (b) An 87-year-old female with vaginal cancer, pitfall for bladder invasion. Sagittal T2 weighted MR image demonstrates tumour bulging into the posterior aspect of the bladder (arrow). This can mimic bladder invasion and is a common pitfall. (c) Axial T2 weighted MR image in the same patient in (b) shows no bladder invasion and preserved low T2 signal of the bladder wall (arrow). The tumour indents the posterior bladder wall but does not invade, making this Stage II rather than Stage IV; this was confirmed by cystoscopy.

Figure 6.

A 57-year-old female with Stage IV vaginal cancer invading the rectum. Axial T2 weighted MR image shows a T2 hyperintense vaginal mass invading the anterior rectal wall (arrow) and involving the left puborectalis muscle (asterisk).

TREATMENT

Treatment of vaginal cancer is guided by the FIGO stage and is summarized in Table 4. Because vaginal cancer is rare, there is much discussion and controversy over preferred treatment. Many guidelines are in fact extrapolated from treatments of cervical cancer and individualized to many centres. If diagnosed and staged early, both surgical resection and radiation can be curative in vaginal cancer.31,64 In the majority of patients and especially more advanced stages, radiation plays a central role in vaginal cancer treatment, consisting of external beam radiation and brachytherapy.31 Radiation is advantageous due to preservation of the vagina.31,65 External beam radiation to the pelvis utilizes CT simulation for 3D conformal treatment planning for more effective tumour dose. Inclusion of external, iliac and obturator nodes in the radiation field is standard. In addition, inguinal nodes are included in the radiation field for distal vaginal tumours, and perirectal and presacral nodes for tumours of the superior posterior vagina or those involving the rectovaginal septum. Cylinder brachytherapy and interstitial implants are reserved for smaller volume or residual disease. MRI is often used to assess response after external beam radiation or to assess and localize initial tumour volume prior to brachytherapy, guide brachytherapy placement and evaluate subsequent response. We briefly describe and summarize key treatment strategies by stages. Figure 7 documents imaging during the course of treatment for a patient with Stage II vaginal cancer.

Table 4.

Treatment of vaginal cancer by International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage

| Stage | Tumour extent | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| I | Confined to vagina | EBRT with BT. Consider surgery for small (<2 cm), minimally invasive exophytic tumours |

| II | Paravaginal tissues but not pelvic wall | Combination of BT and EBRT |

| III | Pelvic wall | EBRT with or without brachytherapy |

| IVA | Extension beyond true pelvis and/or invasion of bladder or rectum | EBRT with or without brachytherapy |

| IVB | Distant metastasis | Chemotherapy with palliative EBRT as indicated |

BT, brachytherapy; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy.

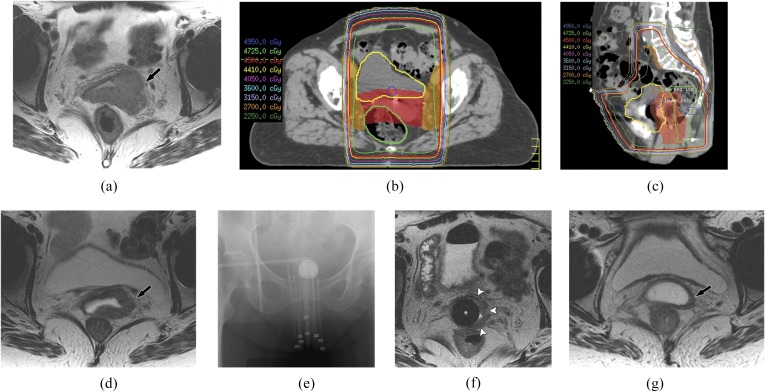

Figure 7.

Imaging at different stages of treatment for a 71-year-old female with Stage II vaginal cancer. (a) Axial T2 weighted MR image shows tumour extending into the paravaginal space with loss of the normal hypointense T2 vaginal wall (arrow). (b, c) Axial and sagittal images from three-dimensional CT simulation treatment plan show targeting of the primary vaginal tumour and iliac and obturator nodal chains for external beam radiation. (d) Axial T2 weighted MR image after external beam radiation shows marked decrease in initial vaginal tumour volume (arrow). (e, f) Localized radiation with brachytherapy. Frontal pelvic radiograph and axial T2 weighted MR image show placement of brachytherapy cylinder [asterisk in (f)] with radiation needles into the vagina for administration of localized therapy. Note the residual tumour of the left lateral aspect of the vagina [white arrowheads in (f)]. (g) Axial T2 weighted MR image following brachytherapy shows continued decrease and near resolution of vaginal tumour (arrow).

Stage I

Radiation therapy is the most common treatment for Stage I vaginal cancer, but surgery may play a role in very early and minimally invasive lesions.65 Typically, combined brachytherapy and external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) are used although some authors report favourable outcomes with brachytherapy alone.31,66 For tumours of the lower vagina, intracavitary and EBRT are preferred. In tumours of the upper vagina, external beam with brachytherapy or surgery (partial or radical vaginectomy, radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection) can be considered. Adjuvant radiation (external beam) can treat residual tumour deposits in patients with positive margins or lymph node-positive disease. Due to the close proximity of critical structures and risk of complications, larger tumours are rarely suitable for surgery.67

Stage II

Radiotherapy is the most common treatment for Stage II disease. Standard radiation treatment consists of a combination of EBRT and brachytherapy (Figure 7).66 Radical surgery (radical vaginectomy or pelvic exenteration) with or without radiotherapy is also an option but is highly morbid so radiation therapy is generally preferred.18,68,69 Concurrent chemotherapy is often recommended as a radiosensitizer for Stage II–IVA vaginal cancer, based on randomized data in cervical cancer, and high incidence of distant metastases reported in one of the larger studies on vaginal cancer by Perez et al,34 30% in patients with Stage II and 50% in Stage III.

Stages III/IV

For Stage III disease, EBRT alone or in combination with brachytherapy is the treatment of choice. Combined chemoradiation has shown high clinical and metabolic responses in females with advanced (Stages III and IV) vaginal cancer.70 Treatment for Stage IVA disease is the same as for Stage III, EBRT with or without brachytherapy.31,36,40,66,71 For patients with Stage IVB disease, chemotherapy with palliative radiation is generally recommended.20,72,73

POST-TREATMENT MRI: RECURRENCE AND COMPLICATIONS

Locoregional recurrences in vaginal cancer are the most common, seen in 23–26% of patients at 5 years and accounting for 68% of relapses in early-stage (Stage I/II) disease and 83% in later stage (Stages III/IV).31,40 Most local recurrences are seen within the first few years, almost 80% by 2 years and 90% by 5 years.31,40 Staging has been shown to be the principal predictive variable for recurrence, reported at 24% for Stage I, 31–32% for Stage II, 53% for Stage III and 73–83% for Stage IV.40 There has been conflicting evidence for lesion location, grade, and HPV status as predictors of recurrence.74 A study by Tarraza et al75 (n = 41), however, found that recurrence site varied with location of the initial tumour, upper vaginal lesions more commonly recurring locally, and lower vaginal lesions more commonly associated with pelvic sidewall or even distant recurrence. A larger study by Chyle et al40 (n = 301) found that both locoregional and metastatic recurrence were more common in larger lesions (>5 cm), lower vaginal (middle and distal third of the vagina) and posterior wall lesions. In patients with recurrence, survival is particularly poor, overall 12% at 5 years and again varies according to stages: 12–18% for Stages I/II and 0–3% for Stages III/IV.40 Patients with local recurrence generally do better than those with regional or distant spread, 20% 5-year survival compared with 4%, respectively.40

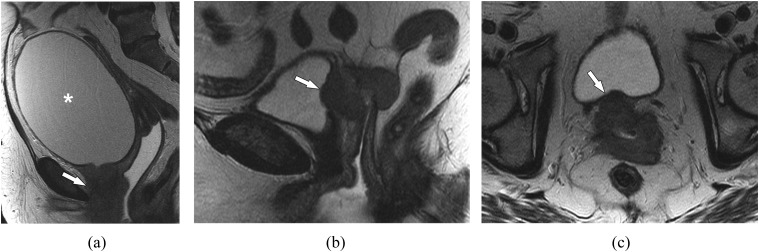

MRI is useful in staging patients with vaginal recurrence, with reported accuracy of 82–95%.11,76 Following pelvic irradiation, the vaginal wall shows T2 hyperintense signal during the first 6 months due to mucosal and intramuscular oedema, making detection of residual or recurrent disease difficult.62 Decrease in tumour size, though, is easily assessed. In these patients, contrast-enhanced 3D dynamic sequences are particularly helpful (Figure 8). Scar or treated tumour will be hypointense on T2 and will not show early avid enhancement on contrast-enhanced T1 weighted imaging. Tumour, however, will be hyperintense on T2 and enhance early and avidly (Figure 8).77 When recurrence is suspected more than 6 months after treatment, MRI readily differentiates between scar tissue and cancer; by this point, radiation-induced oedema should have resolved. A previous study by Ebner et al52 suggested that distinction between fibrosis and recurrent disease can be made solely on T2 weighted imaging at 12–18 months after treatment (Figures 8 and 9). 18F-FDG-PET/CT can also be helpful in assessing for recurrent disease, but the extent of local tumour infiltration and tumour volume will be better assessed on MRI.

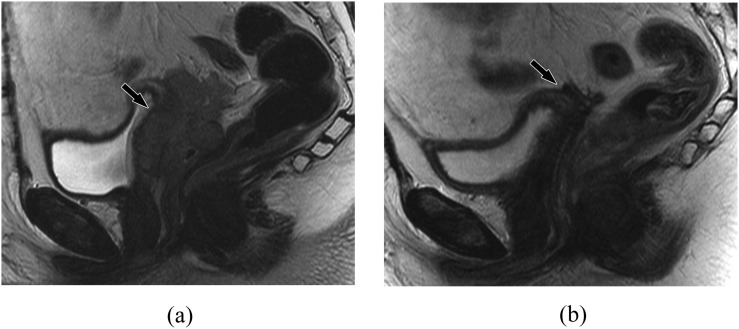

Figure 8.

A 69-year-old female, status after partial vaginectomy with recurrent tumour 1 year later. (a) Sagittal T2 weighted MR image shows diffuse thickening of the residual vagina (arrow). (b) Sagittal fat-suppressed T1 weighted contrast-enhanced MR image shows diffuse enhancement compatible with locally recurrent tumour (arrow). Note that the uterus is surgically absent.

Figure 9.

A 47-year-old female with a history of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia, status after upper vaginectomy with recurrent vaginal mass 15 months later. (a) Sagittal T2 weighted MR image shows a mass involving the vaginal cuff and upper half of the remaining vagina (arrow). Biopsy confirmed squamous cell carcinoma. (b) Sagittal T2 weighted MR image following treatment with chemoradiation shows resolution of the vaginal mass. Mild residual very low T2 signal (arrow) is compatible with fibrosis.

Reported common clinical complications include radiation-induced bladder, rectal and vaginal toxicity; the latter is proportional to the extent of vaginal invasion and FIGO stage.16 Increasing stage, tumour size and total radiation dose predict higher likelihood of complications.36 For instance, the 10-year complication incidence for Stages I/II is reported at 8–14% and for Stages III/IV 23–40%.40 Complications most commonly present within 5 years of treatment but can be seen up to 20 years later.40

On imaging, complications after radiation are common, reported in up to 30% of patients with rectovaginal and vesicovaginal fistulas (Figure 10) seen in 21%.29 Cystitis, proctitis, bowel stricture and perforation, pelvic bone osteonecrosis and stress fractures also occur. Various imaging modalities can be utilized to assess for complications, including MRI. MRI is particularly helpful in depicting and delineating fistulas, with reported accuracy of 91% in vaginal fistulas.78 The appearance of fistulas on MRI is best assessed on T2 weighted images, where a fluid-filled fistula may be seen as a tract of high-signal intensity and an air-filled tract of low-signal intensity. The sagittal plane can be used to optimize localization of the fistula, assessing for disruption or discontinuity of the vaginal, bladder or rectal wall (Figure 10).49,79 In addition to detecting complications such as fistulae in these patients, MRI also readily demonstrates the presence of residual or recurrent tumour, as we have previously described.

Figure 10.

A 55-year-old female with vaginal cancer complicated by radiation-induced vesicovaginal fistula. Sagittal T2 weighted MR image shows communication between the lower vagina and bladder neck/urethra (arrow).

CONCLUSION

Primary vaginal cancer is a rare, yet important, gynaecologic malignancy. Knowledge and familiarity with the MRI features in primary vaginal cancer is useful in diagnosis, local staging, treatment planning and assessment of complications.

Contributor Information

C S Gardner, Email: CSGardner@mdanderson.org.

J Sunil, Email: Sunil.jeph@nychhc.org.

A H Klopp, Email: AKlopp@mdanderson.org.

C E Devine, Email: Catherine.Devine@mdanderson.org.

T Sagebiel, Email: TSagebiel@mdanderson.org.

C Viswanathan, Email: Chitra.Viswanathan@mdanderson.org.

P R Bhosale, Email: Priya.Bhosale@mdanderson.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Creasman WT, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cancer of the vagina. Cancer 1998; 83: 1033–40. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19980901)83:53.0.CO;2-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2013; 63: 11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JS, Backes DM, Hoots BE, Kurman RJ, Pimenta JM. Human papillomavirus type-distribution in vulvar and vaginal cancers and their associated precursors. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113: 917–24. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819bd6e0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinno AK, Saraiya M, Thompson TD, Hernandez BY, Goodman MT, Steinau M, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype prevalence in invasive vaginal cancer from a registry-based population. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 123: 817–21. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herbst AL, Robboy SJ, Scully RE, Poskanzer DC. Clear-cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix in girls: analysis of 170 registry cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1974; 119: 713–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitrović-Jovanović A, Stanimirović B, Nikolić B, Zamurović M, Perisić Z, Pantić-Aksentijević S. Cervical, vaginal and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasms. Vojnosanit Pregl 2011; 68: 1051–6. doi: 10.2298/VSP1112051M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Schwartz SM, Shera KA, Carter JJ, McKnight B, et al. A population-based study of squamous cell vaginal cancer: HPV and cofactors. Gynecol Oncol 2002; 84: 263–70. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strander B, Hällgren J, Sparén P. Effect of ageing on cervical or vaginal cancer in Swedish women previously treated for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3: population based cohort study of long term incidence and mortality. BMJ 2014; 348: f7361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Current FIGO staging for cancer of the vagina, fallopian tube, ovary, and gestational trophoblastic neoplasia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009; 105: 3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lamoreaux WT, Grigsby PW, Dehdashti F, Zoberi I, Powell MA, Gibb RK, et al. FDG-PET evaluation of vaginal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 62: 733–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang YC, Hricak H, Thurnher S, Lacey CG. Vagina: evaluation with MR imaging. Part II. Neoplasms. Radiology 1988; 169: 175–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.1.3420257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor MB, Dugar N, Davidson SE, Carrington BM. Magnetic resonance imaging of primary vaginal carcinoma. Clin Radiol 2007; 62: 549–55. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stenstedt K, Hellström AC, Fridsten S, Blomqvist L. Impact of MRI in the management and staging of cancer of the uterine cervix. Acta Oncol 2011; 50: 420–6. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.541932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhoot NM, Kumar V, Shinagare A, Kataki AC, Barmon D, Bhuyan U. Evaluation of carcinoma cervix using magnetic resonance imaging: correlation with clinical FIGO staging and impact on management. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2012; 56: 58–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9485.2011.02333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraljević Z, Visković K, Ledinsky M, Zadravec D, Grbavac I, Bilandzija M, et al. Primary uterine cervical cancer: correlation of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging and clinical staging (FIGO) with histopathology findings. Coll Antropol 2013; 37: 561–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Crevoisier R, Sanfilippo N, Gerbaulet A, Morice P, Pomel C, Castaigne D, et al. Exclusive radiotherapy for primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. Radiother Oncol 2007; 85: 362–70. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otton GR, Nicklin JL, Dickie GJ, Niedetzky P, Tripcony L, Perrin LC, et al. Early-stage vaginal carcinoma—an analysis of 70 patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2004; 14: 304–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891X.2004.014214.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tjalma WA, Monaghan JM, de Barros Lopes A, Naik R, Nordin AJ, Weyler JJ. The role of surgery in invasive squamous carcinoma of the vagina. Gynecol Oncol 2001; 81: 360–5. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tewari KS, Cappuccini F, Puthawala AA, Kuo JV, Burger RA, Monk BJ, et al. Primary invasive carcinoma of the vagina: treatment with interstitial brachytherapy. Cancer 2001; 91: 758–70. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010215)91:43.0.CO;2-U [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalrymple JL, Russell AH, Lee SW, Scudder SA, Leiserowitz GS, Kinney WK, et al. Chemoradiation for primary invasive squamous carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2004; 14: 110–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1048-891x.2004.014066.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Dam P, Sonnemans H, van Dam PJ, Verkinderen L, Dirix LY. Sentinel node detection in patients with vaginal carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2004; 92: 89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman MS, DeCesare SL, Roberts WS, Fiorica JV, Finan MA, Cavanagh D. Upper vaginectomy for in situ and occult, superficially invasive carcinoma of the vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1992; 166: 30–3. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91823-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khoo VS, Joon DL. New developments in MRI for target volume delineation in radiotherapy. Br J Radiol 2006; 79: S2–15. doi: 10.1259/bjr/41321492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Kurdi M, Monaghan JM. Thirty-two years experience in management of primary tumours of the vagina. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1981; 88: 1145–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1981.tb01770.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis KP, Stanhope CR, Garton GR, Atkinson EJ, O'Brien PC. Invasive vaginal carcinoma: analysis of early-stage disease. Gynecol Oncol 1991; 42: 131–6. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90332-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hellman K, Lundell M, Silfverswärd C, Nilsson B, Hellström AC, Frankendal B. Clinical and histopathologic factors related to prognosis in primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006; 16: 1201–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grigsby PW. Vaginal cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2002; 3: 125–30. doi: 10.1007/s11864-002-0058-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiu TL, Jones RW. Multifocal multicentric squamous cell carcinomas arising in vulvovaginal lichen planus. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2011; 15: 246–7. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31820bad90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melnick S, Cole P, Anderson D, Herbst A. Rates and risks of diethylstilbestrol-related clear-cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina and cervix. An update. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 514–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198702263160905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suthipintawong C, Wejaranayang C, Vipupinyo C. Prognostic significance of ER, PR, Ki67, c-erbB-2, and p53 in endometrial carcinoma. J Med Assoc Thai 2008; 91: 1779–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank SJ, Jhingran A, Levenback C, Eifel PJ. Definitive radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 62: 138–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kirkbride P, Fyles A, Rawlings GA, Manchul L, Levin W, Murphy KJ, et al. Carcinoma of the vagina—experience at the Princess Margaret Hospital (1974–1989). Gynecol Oncol 1995; 56: 435–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kucera H, Vavra N. Radiation management of primary carcinoma of the vagina: clinical and histopathological variables associated with survival. Gynecol Oncol 1991; 40: 12–16. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(91)90076-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Garipagaoglu M, Mutch DG, Lockett MA. Factors affecting long-term outcome of irradiation in carcinoma of the vagina. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1999; 44: 37–45. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00530-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pingley S, Shrivastava SK, Sarin R, Agarwal JP, Laskar S, Deshpande DD, et al. Primary carcinoma of the vagina: Tata Memorial Hospital experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000; 46: 101–8. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00360-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran PT, Su Z, Lee P, Lavori P, Husain A, Teng N, et al. Prognostic factors for outcomes and complications for primary squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina treated with radiation. Gynecol Oncol 2007; 105: 641–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Urbański K, Kojs Z, Reinfuss M, Fabisiak W. Primary invasive vaginal carcinoma treated with radiotherapy: analysis of prognostic factors. Gynecol Oncol 1996; 60: 16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gunderson CC, Nugent EK, Yunker AC, Rocconi RP, Graybill WS, Erickson BK, et al. Vaginal cancer: the experience from 2 large academic centers during a 15-year period. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2013; 17: 409–13. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182800ee2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shah CA, Goff BA, Lowe K, Peters WA, 3rd, Li CI. Factors affecting risk of mortality in women with vaginal cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2009; 113: 1038–45. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819fe844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chyle V, Zagars GK, Wheeler JA, Wharton JT, Delclos L. Definitive radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vagina: outcome and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1996; 35: 891–905. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)02394-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blecharz P, Reinfuss M, Ryś J, Jakubowicz J, Skotnicki P, Wysocki W. Radiotherapy for carcinoma of the vagina. Immunocytochemical and cytofluorometric analysis of prognostic factors. Strahlenther Onkol 2013; 189: 394–400. doi: 10.1007/s00066-012-0291-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ancuţa E, Ancuţa C, Cozma LG, Iordache C, Anghelache-Lupaşcu I, Anton E, et al. Tumor biomarkers in cervical cancer: focus on Ki-67 proliferation factor and E-cadherin expression. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2009; 50: 413–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konstantinos K, Marios S, Anna M, Nikolaos K, Efstratios P, Paulina A. Expression of Ki-67 as proliferation biomarker in imprint smears of endometrial carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol 2013; 41: 212–17. doi: 10.1002/dc.21825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frank SJ, Deavers MT, Jhingran A, Bodurka DC, Eifel PJ. Primary adenocarcinoma of the vagina not associated with diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure. Gynecol Oncol 2007; 105: 470–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kosary CL. FIGO stage, histology, histologic grade, age and race as prognostic factors in determining survival for cancers of the female gynecological system: an analysis of 1973-87 SEER cases of cancers of the endometrium, cervix, ovary, vulva, and vagina. Semin Surg Oncol 1994; 10: 31–46. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980100107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown MA, Mattrey RF, Stamato S, Sirlin CB. MRI of the female pelvis using vaginal gel. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 185: 1221–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hricak H, Chang YC, Thurnher S. Vagina: evaluation with MR imaging. Part I. Normal anatomy and congenital anomalies. Radiology 1988; 169: 169–74. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.1.3420255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim SH, Han MC. Invasion of the urinary bladder by uterine cervical carcinoma: evaluation with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997; 168: 393–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.2.9016214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel S, Liyanage SH, Sahdev A, Rockall AG, Reznek RH. Imaging of endometrial and cervical cancer. Insights Imaging 2010; 1: 309–28. doi: 10.1007/s13244-010-0042-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He H, Bhosale P, Wei W, Ramalingam P, Iyer R. MRI is highly specific in determining primary cervical versus endometrial cancer when biopsy results are inconclusive. Clin Radiol 2013; 68: 1107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.05.095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kinkel K, Ariche M, Tardivon AA, Spatz A, Castaigne D, Lhomme C, et al. Differentiation between recurrent tumor and benign conditions after treatment of gynecologic pelvic carcinoma: value of dynamic contrast-enhanced subtraction MR imaging. Radiology 1997; 204: 55–63. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.1.9205223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ebner F, Kressel HY, Mintz MC, Carlson JA, Cohen EK, Schiebler M, et al. Tumor recurrence versus fibrosis in the female pelvis: differentiation with MR imaging at 1.5 T. Radiology 1988; 166: 333–40. doi: 10.1148/radiology.166.2.3422025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Malayeri AA, El Khouli RH, Zaheer A, Jacobs MA, Corona-Villalobos CP, Kamel IR, et al. Principles and applications of diffusion-weighted imaging in cancer detection, staging, and treatment follow-up. Radiographics 2011; 31: 1773–91. doi: 10.1148/rg.316115515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Charles-Edwards EM, Messiou C, Morgan VA, De Silva SS, McWhinney NA, Katesmark M, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging in cervical cancer with an endovaginal technique: potential value for improving tumor detection in stage Ia and Ib1 disease. Radiology 2008; 249: 541–50. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2491072165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheu MH, Chang CY, Wang JH, Yen MS. Preoperative staging of cervical carcinoma with MR imaging: a reappraisal of diagnostic accuracy and pitfalls. Eur Radiol 2001; 11: 1828–33. doi: 10.1007/s003300000774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sahdev A, Sohaib SA, Wenaden AE, Shepherd JH, Reznek RH. The performance of magnetic resonance imaging in early cervical carcinoma: a long-term experience. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2007; 17: 629–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00829.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaur H, Silverman PM, Iyer RB, Verschraegen CF, Eifel PJ, Charnsangavej C. Diagnosis, staging, and surveillance of cervical carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180: 1621–31. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.6.1801621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hricak H, Yu KK. Radiology in invasive cervical cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996; 167: 1101–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.5.8911159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim WY, Chang SJ, Chang KH, Yoo SC, Lee EJ, Ryu HS. Reliability of magnetic resonance imaging for bladder or rectum invasion in cervical cancer. J Reprod Med 2011; 56: 485–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rockall AG, Ghosh S, Alexander-Sefre F, Babar S, Younis MT, Naz S, et al. Can MRI rule out bladder and rectal invasion in cervical cancer to help select patients for limited EUA? Gynecol Oncol 2006; 101: 244–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Donati OF, Lakhman Y, Sala E, Burger IA, Vargas HA, Goldman DA, et al. Role of preoperative MR imaging in the evaluation of patients with persistent or recurrent gynaecological malignancies before pelvic exenteration. Eur Radiol 2013; 23: 2906–15. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2875-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Griffin N, Grant LA, Sala E. Magnetic resonance imaging of vaginal and vulval pathology. Eur Radiol 2008; 18: 1269–80. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-0865-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hawighorst H, Knapstein PG, Weikel W, Knopp MV, Schaeffer U, Brix G, et al. Cervical carcinoma: comparison of standard and pharmacokinetic MR imaging. Radiology 1996; 201: 531–9. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.2.8888254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Creasman WT. Vaginal cancers. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2005; 17: 71–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lilic V, Lilic G, Filipovic S, Visnjic M, Zivadinovic R. Primary carcinoma of the vagina. J BUON 2010; 15: 241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perez CA, Camel HM, Galakatos AE, Grigsby PW, Kuske RR, Buchsbaum G, et al. Definitive irradiation in carcinoma of the vagina: long-term evaluation of results. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1988; 15: 1283–90. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(88)90222-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jang WI, Wu HG, Ha SW, Kim HJ, Kang SB, Song YS, et al. Definitive radiotherapy for treatment of primary vaginal cancer: effectiveness and prognostic factors. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2012; 22: 521–7. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31823fd621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rubin SC, Young J, Mikuta JJ. Squamous carcinoma of the vagina: treatment, complications, and long-term follow-up. Gynecol Oncol 1985; 20: 346–53. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(85)90216-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stock RG, Chen AS, Seski J. A 30-year experience in the management of primary carcinoma of the vagina: analysis of prognostic factors and treatment modalities. Gynecol Oncol 1995; 56: 45–52. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kunos CA, Radivoyevitch T, Waggoner S, Debernardo R, Zanotti K, Resnick K, et al. Radiochemotherapy plus 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone (3-AP, NSC #663249) in advanced-stage cervical and vaginal cancers. Gynecol Oncol 2013; 130: 75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lian J, Dundas G, Carlone M, Ghosh S, Pearcey R. Twenty-year review of radiotherapy for vaginal cancer: an institutional experience. Gynecol Oncol 2008; 111: 298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Donato V, Bellati F, Fischetti M, Plotti F, Perniola G, Panici PB. Vaginal cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2012; 81: 286–95. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Samant R, Lau B, E C, Le T, Tam T. Primary vaginal cancer treated with concurrent chemoradiation using Cis-platinum. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007; 69: 746–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miyamoto DT, Viswanathan AN. Concurrent chemoradiation for vaginal cancer. PLoS One 2013; 8: e65048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tarraza MH, Jr, Muntz H, Decain M, Granai OC, Fuller A, Jr. Patterns of recurrence of primary carcinoma of the vagina. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 1991; 12: 89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gray HJ. Advances in vulvar and vaginal cancer treatment. Gynecol Oncol 2010; 118: 3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Alt CD, Brocker KA, Eichbaum M, Sohn C, Arnegger FU, Kauczor HU, et al. Imaging of female pelvic malignancies regarding MRI, CT, and PET/CT: part 2. Strahlenther Onkol 2011; 187: 705–14. doi: 10.1007/s00066-011-4002-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Healy JC, Phillips RR, Reznek RH, Crawford RA, Armstrong P, Shepherd JH. The MR appearance of vaginal fistulas. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996; 167: 1487–9. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.6.8956582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Narayanan P, Nobbenhuis M, Reynolds KM, Sahdev A, Reznek RH, Rockall AG. Fistulas in malignant gynecologic disease: etiology, imaging, and management. Radiographics 2009; 29: 1073–83. doi: 10.1148/rg.294085223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]