Abstract

Objective:

Glioma classification and characterization may be facilitated by a multiparametric approach of perfusion metrics, which could not be achieved by conventional MRI alone. Our aim is to explore the potential of relative percentage signal intensity recovery (rPSR) values, in addition to relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) and relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) of first-pass T2* dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) perfusion MRI, in differentiating high- and low-grade glioma.

Methods:

This prospective study included 39 patients with low-grade and 25 patients with high-grade glioma. rPSR, rCBV and rCBF were calculated from the first-pass T2* DSC perfusion MRI. rPSR was calculated using standard software and validated with dedicated perfusion metrics analysis software. The statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

Results:

Variation in rPSR, rCBV and rCBF values between low- and high-grade gliomas were statistically significant (p < 0.005). The ROC curve analysis for each of them yielded 96% sensitivity and 71.8% specificity; 88% sensitivity and 69.2% specificity; and 72% sensitivity and 66.7% specificity. The area under the curve (AUC) from the ROC curve analysis yielded 0.893, 0.852 and 0.702 for rPSR, rCBV and rCBF, respectively. The rPSR calculation with the validation software yielded 92.3% sensitivity and 72% specificity with an AUC of 0.864.

Conclusion:

rPSR inversely correlates while rCBV and rCBF values directly correlate with the tumour grade. Furthermore, the overall diagnostic performance of rPSR is better than rCBV and rCBF values.

Advances in knowledge:

rPSR of T2* DSC perfusion is an indicator of blood–brain barrier status and lesion leakiness, which has not been explored yet compared with the usual haemodynamic parameters, rCBV and rCBF.

Gliomas, the most common primary brain tumour of the brain, are heterogeneous, showing highly varied histopathological features during malignant transformation of the tumour reflecting alterations in the tumour vasculature.1 The broad category of glioma represents approximately 30% of all the tumours. Low-grade astrocytomas (60–70%) and oligodendrogliomas (10–30%) are two common subtypes of low-grade gliomas. Among them, glioblastoma and astrocytoma account for 75% of gliomas.2 With the advent of advanced imaging technologies, heterogeneity in gliomas such as neovascularization, angiogenesis, loss of blood–brain barrier (BBB) integrity, tortuousness, disorganized and highly permeable vessels may be non-invasively measured with the help of perfusion imaging.3–5 Dynamic susceptibility contrast (DSC) perfusion MRI is a widely accepted tool for evaluating the haemodynamic characteristics of the brain, which are of great interest since it helps in assessing the malignancy of the tumour. The common haemodynamic parameters assessed using perfusion MRI are relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) and relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF).6–8 In this study, we use a comparatively newer parameter, relative percentage signal intensity recovery (rPSR), whose potential has not been exploited to its best for haemodynamic calculations, even though this parameter has shown promise in the differentiation of brain tumours.9–11 PSR is the percentage of the signal intensity recovered at the end of the first pass of the contrast agent with respect to the pre-contrast baseline signal intensity. After the administration of the contrast agent, there is a sudden decrease in the signal intensity owing to the variation in the local magnetic field leading to T2* decay, which is seen as a dip in the mean signal intensity–time curve, and then the signal returns towards the baseline.9–11

The tumour rCBV provides information about the tumour blood levels and degree of angiogenesis but fails to provide information regarding capillary permeability. This drawback of DSC-MR perfusion imaging can be addressed by evaluating the rPSR obtained from the signal intensity–time curve formed at the end of the first pass of contrast agent in DSC-MR perfusion imaging.9,10 Previous studies have observed that the contrast agent leakage, size of the extravascular space and the rate of blood flow that reflects the alterations in capillary permeability are related to rPSR.10,11 There are reports which state that information regarding capillary permeability and lesion leakiness can be gathered from the signal intensity–time curve obtained from the first-pass T2* DSC perfusion. Usually, this is performed using dynamic contrast-enhanced perfusion MRI, which involves additional scan time and also post-processing assumptions and extrapolations.9–11

Lupo et al4 was the first to report the characterization of high-grade gliomas using the PSR and peak height. rPSR is the only parameter among the different perfusion metrics which takes into account the leakage factor for the characterization of heterogeneity of brain tissues, compared with the other two parameters rCBV and rCBF where the leakage is neglected during the evaluation. The rPSR values of lower grade gliomas have not been explored, and hence an effort to differentiate between high- and low-grade gliomas using this new parameter will be advantageous. Hence, in the present study, we have evaluated all the parameters rPSR, rCBV and rCBF of low- and high-grade gliomas to find the potential of rPSR to differentiate different grades of glioma over the other two conventionally used parameters rCBV and rCBF. rPSR values were evaluated using two different standard software programs. Furthermore, we have performed a test for correlation between these parameters.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients

64 patients with a mean age of 38.5 years ranging from 18 to 67 years with gliomas were prospectively scanned before surgery. Patients who had undergone chemotherapy and radiation therapy prior to imaging and those having tumour exclusively located in the ventricles were excluded from the analysis. Post-surgically, the tumours were pathologically identified as 25 high-grade gliomas (7 glioblastomas, 13 grade III astrocytomas and 5 grade III oligoastrocytomas) and 39 low-grade gliomas (24 grade I astrocytomas, 7 grade II astrocytomas and 8 low-grade oligoastrocytomas). The age, sex and pathology details of the patients included in this study are given in Table 1. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology, Trivandrum, kerala, India. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients who have participated in the study.

Table 1.

Age, sex and pathology details of patients in the study

| Patient no. | Age (years) | Sex | Tumour pathology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 | F | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| 2 | 28 | M | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| 3 | 34 | F | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| 4 | 48 | M | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| 5 | 26 | F | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| 6 | 57 | M | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| 7 | 23 | F | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| 8 | 21 | M | Left posterior frontal high-grade glioma |

| 9 | 49 | M | Right temporoparietal high-grade glioma |

| 10 | 32 | F | Right angular gyrus and right parietal high-grade glioma |

| 11 | 48 | M | Right frontal high-grade glioma |

| 12 | 55 | M | Right occipital high-grade glioma |

| 13 | 37 | M | Left frontotemporal high-grade glioma |

| 14 | 43 | M | Left frontoparietotemporal high-grade glioma |

| 15 | 43 | M | Right temporal high-grade glioma |

| 16 | 43 | F | Left frontal high-grade glioma |

| 17 | 42 | M | Left frontal high-grade glioma |

| 18 | 40 | F | Left frontal high-grade glioma |

| 19 | 58 | M | High-grade glioma |

| 20 | 23 | M | High-grade glioma |

| 21 | 63 | M | Left thalamic oligoastrocytoma with anaplastic changes grade III |

| 22 | 56 | M | Left temporal high-grade mixed glioma |

| 23 | 67 | F | High-grade mixed glioma |

| 24 | 50 | M | Left supramarginal gyrus high-grade mixed glioma |

| 25 | 33 | M | High-grade mixed oligoastrocytoma |

| 26 | 27 | F | Left temporal low-grade astrocytoma |

| 27 | 37 | F | Left frontal astrocytoma |

| 28 | 20 | M | Right temporal astrocytoma |

| 29 | 26 | M | Corpus callosum low-grade astrocytoma |

| 30 | 18 | F | Right frontal gemistocytic low-grade astrocytoma |

| 31 | 29 | M | Low-grade astrocytoma |

| 32 | 26 | F | Left temporal low-grade fibrillary astrocytoma |

| 33 | 32 | F | Pineal region low-grade astrocytoma |

| 34 | 42 | M | Thalamic low-grade astrocytoma |

| 35 | 37 | F | Low-grade astrocytoma |

| 36 | 28 | F | Right frontal low-grade astrocytoma |

| 37 | 19 | F | Right temperoinsular low-grade astrocytoma |

| 38 | 18 | F | Low-grade pontine astrocytoma |

| 39 | 28 | M | Right frontal lobe low-grade astrocytoma |

| 40 | 28 | F | Low-grade astrocytoma |

| 41 | 32 | M | Right frontal low-grade fibrillary astrocytoma |

| 42 | 28 | M | Left frontal pilocytic and fibrillary astrocytoma |

| 43 | 29 | M | Left frontal astrocytoma |

| 44 | 21 | M | Low-grade astrocytoma |

| 45 | 34 | M | Low-grade astrocytoma |

| 46 | 33 | M | Low-grade astrocytoma |

| 47 | 31 | M | Low-grade fibrillary astrocytoma |

| 48 | 36 | F | Low-grade fibrillary astrocytoma |

| 49 | 35 | M | Low-grade fibrillary astrocytoma |

| 50 | 57 | M | Fibrillary astrocytoma grade II |

| 51 | 34 | M | Left frontal astrocytoma grade II |

| 52 | 57 | M | Right frontoparietal astrocytoma grade II |

| 53 | 44 | M | Astrocytoma grade II |

| 54 | 46 | F | Astrocytoma grade II |

| 55 | 47 | M | Fibrillary astrocytoma grade II |

| 56 | 37 | M | Fibrillary astrocytoma grade II |

| 57 | 50 | F | Corpus callosum low-grade mixed oligoastrocytoma |

| 58 | 43 | F | Right temporal mixed low-grade oligoastrocytoma |

| 59 | 36 | F | Frontoparietal low-grade mixed oligoastrocytoma |

| 60 | 33 | M | Right frontoparietal low-grade mixed oligoastrocytoma |

| 61 | 35 | M | Right frontal low-grade mixed oligoastrocytoma |

| 62 | 56 | F | Right posterior frontal low-grade mixed oligoastrocytoma |

| 63 | 45 | F | Left frontal low-grade mixed oligoastrocytoma |

| 64 | 46 | M | Left frontal low-grade mixed oligoastrocytoma |

F, female; m, male.

MRI and first-pass T2* dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging

The imaging of all patients was performed on a 1.5 T MR system (Avanto Total Imaging Matrix; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using a 12-channel phased-array head coil. Each patient underwent conventional MRI with T1, T2 and post-contrast T1 sequences. Perfusion imaging was performed using the T2* weighted gradient echo, echo planar imaging sequence with repetition time = 1800 ms, echo time = 43 ms, slice thickness = 5 mm, interslice gap = 1.5 mm, matrix = 128 × 128 and average = 1. 50 dynamic scans with a time resolution of 1.35 s per 20 slices were performed. In order to obtain a pre-contrast baseline, the first 10 acquisitions were performed before the administration of the contrast agent. At the end of the 10th image volume acquisition, an intravenous bolus injection of 0.2 mmol kg−1 of body weight of gadolinium–diethylene triamine penta-acetic acid at a flow rate of 5-ml s−1 followed by a 20-ml saline flush was applied.

rCBV, rCBF and rPSR evaluation

T2* weighted DSC-MR images were transferred to a separate MRI workstation (Leonardo; Siemens) for generating CBV, CBF maps and the T2* weighted signal intensity curves using the perfusion software. Small regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn under the supervision of an experienced neuroradiologist to make sure that the ROIs were placed accurately over the solid tumour region of the lesion. The whole tumour delineations are not considered for the analysis to avoid the errors that would arise from regions of necrosis, haemorrhagic regions etc. The solid tumour area was identified using conventional MRI sequences. Circular ROIs of size 5–40 mm were drawn on multiple regions on the CBV map of the solid tumour area, and the region with maximum CBV was identified and measured. CBV values were also calculated from the contralateral normal-appearing white matter. rCBV was calculated as the ratio of maximum CBV from the tumour area to CBV from the contralateral normal area. Similarly, to get rCBF values, multiple ROIs of 5–40 mm were placed on the solid tumour tissue and maximum CBF was measured from the CBF maps. CBF values from contralateral normal-appearing white matter were taken to find out the rCBF as the ratio between the two. In the T2* DSC perfusion MR image, the slices corresponding to the maximum CBV on rCBV maps were identified, and all the slices having the same slice number obtained at different times were sorted to get the mean signal intensity time image. ROIs of 5–40 mm diameter were drawn on the T2* DSC perfusion MR image in the area having maximum CBV in the solid tumour to get the mean signal intensity–time curves for the tumour. ROIs were placed in the contralateral normal regions to get the corresponding mean signal intensity–time curve from the contralateral area (Figure 1). The post-contrast T2* weighted signal intensity S1, the pre-contrast signal intensity S0 and the minimum T2* weighted signal intensity Smin were found from the mean signal intensity–time curves obtained from the tumour region and the contralateral normal regions, respectively.

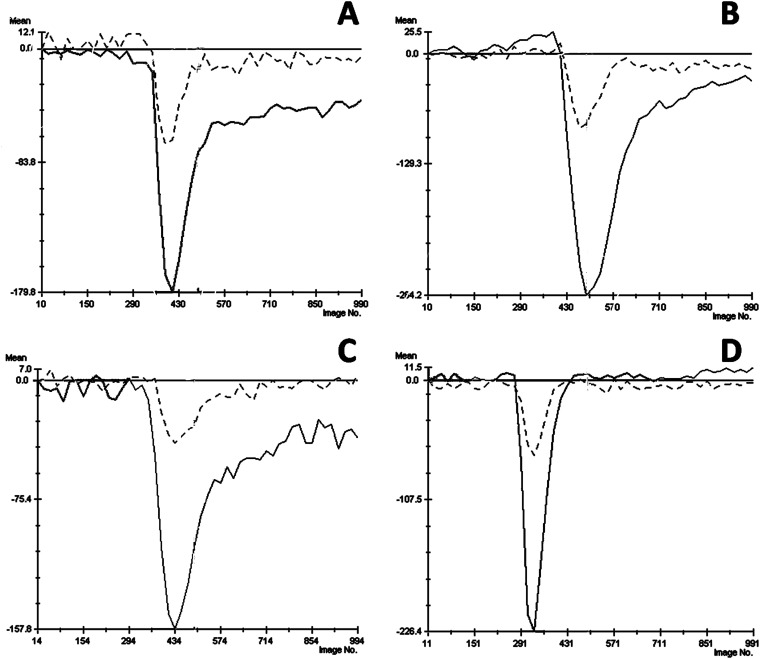

Figure 1.

The mean signal intensity–time curves for the regions of interest (ROIs) drawn on the solid tumour area (darker line) and contralateral normal area (dashed line) of grade IV (A), grade III (B), grade II (C) and grade I (D) gliomas using the perfusion software of the Leonardo workstation.

Likewise, rPSR for all patients was calculated using the following equation.

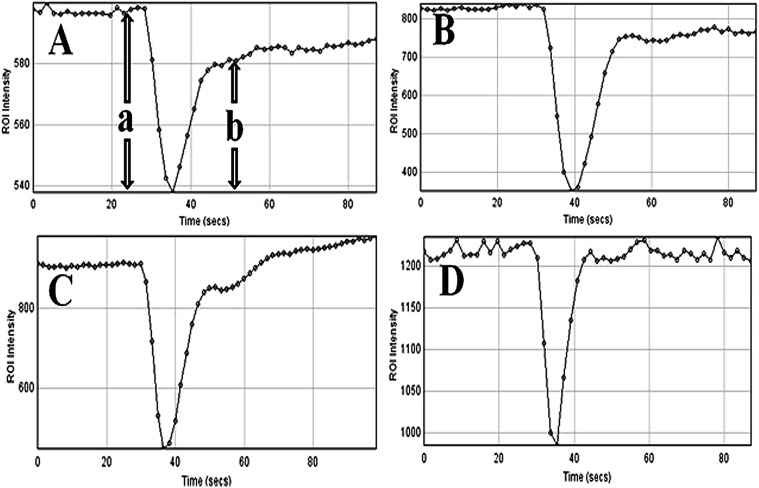

where S1 is the post-contrast T2* weighted signal intensity, S0 is the pre-contrast signal intensity, Smin is the minimum T2* weighted signal intensity, and (S1–Smin) is taken as “b” and (S0–Smin) is taken as “a” so that PSR = b/a (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

The mean signal intensity–time curves for the regions of interest (ROIs) drawn on the solid tumour area of grade IV (A), grade III (B), grade II (C) and grade I (D) glioma using the DSCoMAN plugin of ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

rPSR calculations were reconfirmed using an additional software DSCoMAN plugin (Dynamic Susceptibility Contrast MR Analysis; Daniel P Barboriak Laboratory, Duke University, Durham, NC) installed on ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.46r, Wayne Rasband; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) using T2* weighted DSC perfusion MR images before and after the bolus injection. Both the software obtains the mean signal intensity–time curve for the calculation of PSR over all the time points. The major difference between the two software is that the signal intensity–time curve of the tumour as well as the normal area are visualized and evaluated simultaneously in the case of the Siemens software (Leonardo), whereas they are evaluated separately in the case of DSCoMAN. Similarly, tumour regions having maximum CBV on rCBV maps are identified and ROIs of 5–40 mm diameter were drawn on T2* echoplanar imaging perfusion MR images and the signal intensity–time curve was plotted using the DSCoMAN plugin of the ImageJ software. An experienced neuroradiologist approved the selection of all ROIs. PSR values were calculated from the signal intensity–time curve obtained from the tumour area. For normalization, the ROI was also placed on the contralateral normal-appearing white matter for calculating the relative PSR. Likewise, rPSR for all patients was calculated using the above equation.

Statistical analysis

χ2 analysis was used to find the difference in the age and sex between patient groups. One-way ANOVA and the Bonferroni correction method were performed on patient groups with high-grade gliomas, low-grade gliomas and between each of the grades considered, to evaluate the variation in the rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF values. The Pearson correlation analysis was performed to analyse the correlation among the parameters. In addition to that, box plots were obtained for each of the grades of glioma for the parameters rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF. Additionally, linear discriminant analysis was performed to compare the diagnostic accuracy between rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF values, and a regression analysis was performed with high- and low-grade gliomas as dependent variables and the parameters of perfusion as independent variables. All statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences PC v.17.0 for windows SPSS 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed using MedCalc software (MedCalc trial v. 12.5; MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium) to find out the diagnostic accuracy of the parameters under investigation.

RESULTS

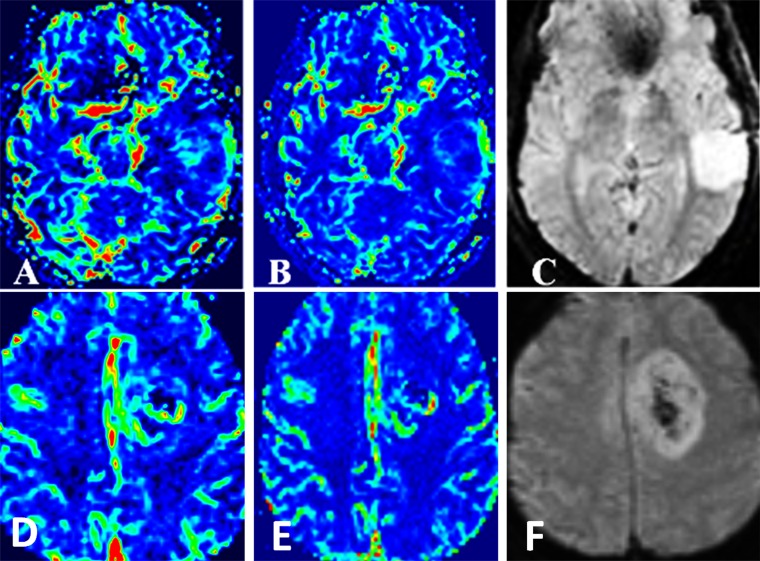

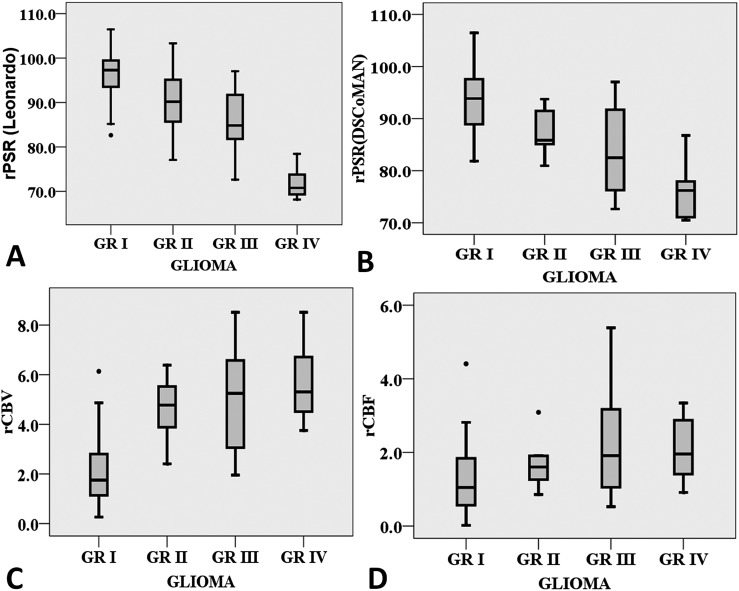

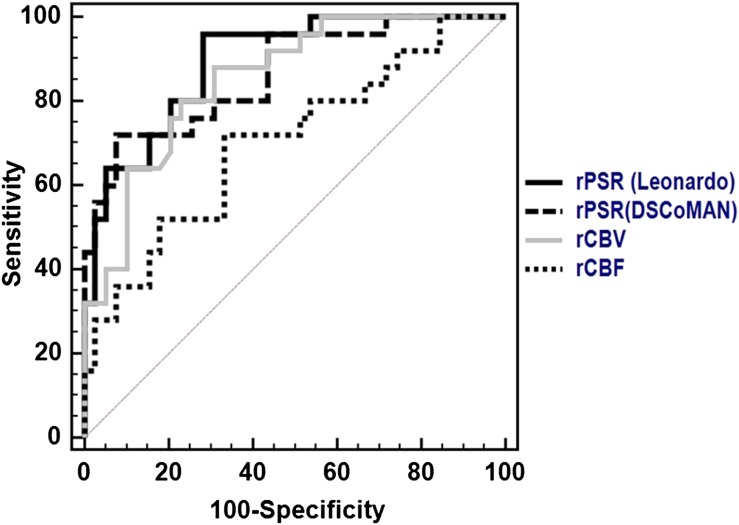

The mean signal intensity–time curves obtained from the Leonardo workstation and the DSCoMAN software are shown in Figures 1A–D and 2A–D, respectively. The unpaired t-test for the difference in patient age was significant with a p-value of 0.016 [low-grade vs high-grade glioma, mean age 38.5 years, range (18–67 years)], and the test for difference in sex was not significant (p = 0.358). The results of the ANOVA performed for rCBV, rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN and rCBF metrics between each of the grades of glioma are given in Table 2. Typical examples of CBV, CBF and T2* DSC perfusion maps of low- and high-grade gliomas used in this study are shown in Figure 3A–F. Box plots and ROC curves of rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF for different grades of glioma are shown in Figures 4 and 5, respectively. The sensitivity, specificity, area under the curve (AUC) and significance obtained for rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF for different grades of glioma are shown in Tables 3–6. Linear discriminant analysis was performed for presenting the difference in diagnostic accuracy of the parameters rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF. Table 7 shows the linear discriminant analysis performed on rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF parameters. The F-test, Wilk's lambda and significance level were obtained for differentiating between low- and high-grade gliomas. In the linear discriminant analysis, Wilk's lambda helps to identify the variables that contribute significantly to the differentiation of low- and high-grade gliomas and shows that it is significant for all the perfusion metrics such as rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF (p ≤ 0.002). Cross-validation using the leave-one-out method in the discriminant analysis resulted in correctly predicting the tumour (low and high grade) in 87.5% of cases, with correct identification of 89.7% of low-grade and 84% of high-grade gliomas. A multiple regression analysis with the various imaging parameters (rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF) as the independent variables and high- and low-grade gliomas as the dependent variables are shown in Supplementary Tables A and B.

Table 2.

Results of one-way ANOVA performed for the relative percentage signal intensity recovery (rPSR) from the Leonardo workstation (rPSRLeonardo) and the DSCoMAN plugin (rPSRDSCoMAN), relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) and relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) metrics between each grade of glioma and the significance observed between them

| Glioma | rPSRLeonardo | rPSRDSCoMAN | rCBV | rCBF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High–low | <0.001a | <0.001a | <0.001a | <0.002a |

| Grades I–II | 0.04 | 0.023 | 0.118 | 0.493 |

| Grades I–III | <0.001a | <0.001a | <0.001a | <0.006a |

| Grades I–IV | <0.001a | <0.001a | <0.001a | 0.016 |

| Grades II–III | 0.131 | 0.183 | 0.354 | 0.197 |

| Grades II–IV | <0.001a | 0.001a | 0.005a | 0.203 |

| Grades III–IV | <0.001a | 0.02 | 0.511 | 0.799 |

| Grade I and low-grade oligoastrocytoma | 0.001a | 0.002a | <0.001a | 0.12 |

| Grade II and low-grade oligoastrocytoma | 0.662 | 0.870 | 0.268 | 0.711 |

| Grade III and low-grade oligoastrocytoma | 0.069 | 0.127 | 0.06 | 0.367 |

| Grade IV and low-grade oligoastrocytoma | 0.001a | 0.001a | 0.020 | 0.365 |

p-values that are significant after Bonferroni correction of corrected alpha = 0.0125.

Figure 3.

Typical examples of cerebral blood volume, cerebral blood flow and T2* perfusion maps of low-grade (A–C) and high-grade gliomas (D–F).

Figure 4.

(A–D) Box plots showing variation of the relative percentage signal intensity recovery (rPSR) from the Leonardo workstation (rPSRLeonardo), the DSCoMAN plugin (rPSRDSCoMAN), relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) and relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF), which indicates the efficiency of grading between low- and high-grade gliomas.

Figure 5.

The receiver operating characteristic curves drawn for the parameters the relative percentage signal intensity recovery (rPSR) from the Leonardo workstation (rPSRLeonardo), the DSCoMAN plugin (rPSRDSCoMAN), relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) and relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) for the analysis between low- and high-grade gliomas.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, area under the curve (AUC) and significance obtained for the relative percentage signal intensity recovery from the Leonardo workstation for different grades of glioma

| Glioma | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High–low | 96 | 71.8 | 0.893 | 0.0001 |

| Grades I–II | 71.4 | 75 | 0.705 | 0.11 |

| Grades I–III | 94.1 | 78.1 | 0.884 | 0.0001 |

| Grades I–IV | 100 | 100 | 0.100 | 0.0001 |

| Grades II–III | 94.4 | 42.9 | 0.690 | 0.151 |

| Grades II–IV | 85.7 | 100 | 0.979 | 0.001 |

| Grades III–IV | 100 | 88.9 | 0.968 | 0.001 |

Table 6.

Sensitivity, specificity, area under the curve (AUC) and significance obtained for the relative cerebral blood flow for different grades of glioma

| Glioma | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High–low | 72.0 | 66.7 | 0.703 | 0.003 |

| Grades I–II | 35.5 | 100.0 | 0.625 | 0.2 |

| Grades I–III | 67.7 | 72.2 | 0.706 | 0.009 |

| Grades I–IV | 67.7 | 71.4 | 0.737 | 0.0198 |

| Grades II–III | 87.5 | 50 | 0.632 | 0.219 |

| Grades II–IV | 87.5 | 57.1 | 0.714 | 0.134 |

| Grades III–IV | 22.2 | 100 | 0.536 | 0.786 |

Table 7.

Results of the linear discriminant analysis performed on the relative percentage signal intensity recovery (rPSR) from the Leonardo workstation (rPSRLeonardo), the DSCoMAN plugin (rPSRDSCoMAN), relative cerebral blood volume (rCBV) and relative cerebral blood flow (rCBF) parameters obtained through dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion MRI

| Parameters | Wilk's lambda | F-test | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| rPSRLeonardo | 0.566 | 47.45 | 0.000 |

| rPSRDSCoMAN | 0.609 | 39.87 | 0.000 |

| rCBV | 0.640 | 34.93 | 0.000 |

| rCBF | 0.854 | 10.60 | 0.002 |

Table 5.

Sensitivity, specificity, area under the curve (AUC) and significance obtained for the relative cerebral blood volume for different grades of glioma

| Glioma | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High–low | 88.0 | 69.2 | 0.852 | 0.001 |

| Grades I–II | 41 | 100 | 0.707 | 0.02 |

| Grades I–III | 80.6 | 83.3 | 0.892 | 0.0001 |

| Grades I–IV | 87.1 | 100 | 0.954 | 0.0001 |

| Grades II–III | 100 | 33.3 | 0.607 | 0.351 |

| Grades II–IV | 75 | 100 | 0.892 | 0.0001 |

| Grades III–IV | 27.8 | 100 | 0.575 | 0.549 |

ROC curve analysis between low- and high-grade gliomas for rPSRLeanardo, rCBV and rCBF yielded 96%, 88% and 72% sensitivity and 71.8%, 69.2% and 66.7% specificity, respectively. Similarly, the AUCs obtained for rPSRLeonardo, rCBV and rCBF are 0.893, 0.852 and 0.702, respectively. The rPSRDSCoMAN yielded 92.3% sensitivity, 72% specificity and AUC = 0.864. The Pearson correlation analysis performed between rPSRLeonardo and rPSRDSCoMAN yielded r = 0.638, p = 0.001 and between rPSRLeonardo and rCBV yielded a correlation coefficient value of r = −0.529, p = 0.001 and between rPSRLeonardo and rCBF, r = −0.239, p = 0.058 and between rCBV and rCBF, the value of r was 0.292, p = 0.018.

In high-grade gliomas, the rCBV ranged from 1.975 to 8.514 with an average of 5.290 ± 1.98 and rPSRLeonardo ranged from 60.90 to 97.03 with an average of 81.37 ± 8.98, whereas the rCBF ranged from 0.526 to 6.623 with an average of 2.439 ± 1.68. Furthermore, the rCBV in low-grade gliomas had an average value of 2.598 ± 1.64, which ranged from 0.261 to 6.385, whereas the rPSRLeonardo ranged from 82.63 to 106.45 with an average value of 94.78 ± 6.57, and rCBF in low-grade gliomas ranged from 0.018 to 4.408 with an average value of 1.378 ± 0.925. High-grade gliomas exhibited significantly higher rCBV and rCBF with respect to low-grade gliomas. Conversely, significantly lower rPSR values were observed in high-grade gliomas.

Evaluation of rPSRDSCoMAN for high-grade gliomas yielded values from 70.48 to 97.04 with an average of 81.41 ± 7.66, whereas the rPSRDSCoMAN in low-grade gliomas ranged from 80.94 to 106.5 with an average value of 92.50 ± 6.28. Bonferroni correction was performed such that the corrected alpha is equal to 0.0125, so that a parameter is significant only if the p-value is <0.0125, and the results are discussed based on the corrected Bonferroni analysis.

DISCUSSION

Results of the present study regarding rPSR, rCBV and rCBF values of different grades of gliomas showed markedly significant variations in some of the metrics, especially in the rPSR. The relationship of rCBV and rCBF between different grades of glioma has been well established by different research groups.6–8,12 But, so far no reports are available that establish the use of a combined parametric approach of rCBV, rPSR and rCBF using the first-pass T2* DSC perfusion for evaluating different grades of glioma. The ANOVA analysis and Bonferroni corrected p-value showed that rPSRLeonardo values are able to differentiate more tumour types (grades I and III, grades I and IV, grades II and IV, grades III and IV, grade I and low-grade oligoastrocytoma, grade IV and low-grade oligoastrocytoma) than rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF. However, the rPSRDSCoMAN was not able to differentiate grades III and IV glioma after Bonferroni correction. The sensitivity and AUC of rPSRLeonardo was slightly higher than that of rPSRDSCoMAN, whereas the specificity of rPSR in differentiating high- and low-grade gliomas obtained by both the software were comparable (Tables 3 and 4). The Pearson correlation coefficient between rPSRLeonardo and rPSRDSCoMAN shows a linear positive relationship. The present study highlights the finding that rPSR gives very good sensitivity and specificity in discriminating high- and low-grade glioma in comparison with rCBV and rCBF values. This is clear from the combined ROC curve analysis and the AUC obtained for rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF values (Figure 5, Tables 3–6). The higher F values and lower Wilk's lambda values indicate efficiency of the parameter rPSRLeonardo in discriminating the grades of the glioma compared with other parameters used in the study (Table 7). Additionally, the regression analysis revealed that the parameters rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN and rCBV are helpful in differentiating low- and high-grade gliomas. The R2 value of 0.604 indicates that approximately 60.4% of the dependent variables such as low- and high-grade gliomas are explained by the regression model using the independent variables rPSRLeonardo, rPSRDSCoMAN, rCBV and rCBF (Supplementary Tables A and B).

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, area under the curve (AUC) and significance obtained for different grades of glioma for the parameter the relative percentage signal intensity recovery from the DSCoMAN plugin

| Glioma | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High–low | 92.3 | 72.0 | 0.864 | 0.0001 |

| Grades I–II | 85.7 | 65.6 | 0.781 | 0.0009 |

| Grades I–III | 94.1 | 65.6 | 0.856 | 0.0001 |

| Grades I–IV | 100 | 87 | 0.973 | 0.0001 |

| Grades II–III | 66.7 | 85.7 | 0.666 | 0.150 |

| Grades II–IV | 100 | 85.7 | 0.918 | 0.001 |

| Grades III–IV | 72.2 | 85.7 | 0.793 | 0.006 |

rCBV values can distinguish between low- and high-grade gliomas with 88% sensitivity and 69.2% specificity. In this study, rCBV showed a significant difference among the different grades such as high- (grades III and IV) and low-grade gliomas (grades I and II), grades I and III, grades I and IV, grades II and IV and between grade I and low-grade oligoastrocytomas after applying the Bonferroni correction method. Inclusion of more oligoastrocytoma cases in the study would have contributed to the slightly lower sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, previous reports observe that the oligodendroglial component shows elevated rCBV owing to the inherent dense network of branching capillaries.3,13

The diagnostic accuracy of rPSRLeonardo to distinguish low- and high-grade gliomas was found to be much higher with 96% sensitivity, 71.8% specificity and AUC 0.893. Since this is the first report on the differentiation of low- and high-grade gliomas using rPSR, it is difficult to compare our study against other results in the literature. Glioblastomas are characterized by arteriovenous shunts, intratumoral bleeding, abnormal vessels, vascular pooling, stasis and mass effect. It has been reported that the presence of the arteriovenous shunts results in full recovery of the signal intensity and will be reflected as a higher value of rPSR.9 But, in our study, we obtained lower rPSR values in glioblastoma. Based on reported studies, we are of the opinion that lower rPSR values in high-grade tumours are owing to vascular pooling, stasis, damage to microvasculature, abnormal vessels, intratumoral bleeding, which in turn lead to leakage of the BBB.9,14–17 Conversely, low-grade tumours exhibit lower vascularity than and have signal intensity recovery almost comparable to a normal parenchyma, which could be the reason for high rPSR values found in such cases.

Owing to their difference in behaviour from the low-grade gliomas such as chicken wire type of hypervascularity, low-grade oligoastrocytomas are of great interest and are included in the study to see the variation of rPSR values in them.13,18 Evidently, rPSRLeonardo could very well distinguish between all grades except between grades I and II glioma, grades II and III glioma, low-grade oligoastrocytoma and grade II glioma and between low-grade oligoastrocytoma and grade III glioma. From these results, it is inferred that there are significant differences in rPSR values of low-grade glioma and low-grade oligoastrocytoma. However, there is no significant difference in the rPSR of low-grade oligoastrocytoma and grade II astrocytoma and also between anaplastic astrocytomas. Since rPSR reflects the alterations in capillary permeability,10 our results indicate that the capillary permeability in low-grade oligoastrocytoma, grade II astrocytoma and anaplastic astrocytoma are comparable.

In the present study, it is observed that rCBV and rPSRDSCoMAN could not differentiate between grades III and IV gliomas, while rPSRLeonardo could differentiate them very well. Based on reports, we believe that the calculation of rCBV in glioblastoma is complicated owing to disruption or leakage of the BBB in the tumour capillaries.10 rCBV is calculated based on the assumption that there is no contrast leakage and recirculation, whereas no such assumptions are made for the calculation of rPSR.13,17 However, Preul et al8 reported a marked difference in the rCBV of grade III glioma and glioblastoma. From the results of the present study, we suggest that rPSR is a potential alternative to rCBV when analysing tumours having disrupted or completely absent BBB. This result agrees well with the results of Cha et al,10 where it is reported that rPSR is influenced by the microvascular leakage and the capillary permeability. Based on the reported studies, our study confirms that the lower the rPSR, the larger will be the permeability and microvascular leakage and the higher will be the malignancy. rPSRLeonardo values are able to differentiate between grades III and IV glioblastoma, which is similar to the results of Lupo et al,4 who observed lower mean percentage recovery values in patients with grade IV gliomas compared with grade III gliomas.

We also considered the role of rCBF in the differentiation of glioma and found that this parameter can also differentiate low- and high-grade gliomas with sensitivity 72% and specificity 66.7%. However, on applying Bonferroni correction, the parameter rCBF could effectively differentiate only grade I and III gliomas among all the groups considered. Nevertheless, against expectation, our study resulted in very low correlation between rCBV and rCBF (r = 0.292). Previous studies of gliomas with positron emission tomography observed that the mean values of CBF in the tumour area are lower than in the contralateral normal area. In the present study, we have observed lower CBF in the tumour area than in the contralateral normal area in a few cases. Based on this observation and the above report, we presume that the reduced CBF values in the tumour region would have resulted in the low correlation between CBF and CBV.19,20 Of course, our study has certain limitations. The manual placement of the ROI for the assessment of different parameters might have influenced the study. Varied sizes of the tumour demanded ROIs of different sizes, and, hence, this could not be avoided. Also, the site of the ROI considered for the evaluation of rPSR, rCBV and rCBF might not exactly match with the site considered for histopathological evaluation. The findings of this study suggest that the DSC perfusion MRI by the combined evaluation of rCBV, rCBF and rPSR metrics may be of value in assessing the haemodynamic characteristics of the tumour. Tumour malignancy can be identified using perfusion metrics of DSC perfusion since rCBV is a marker of tumour angiogenesis, rCBF relates to abnormal blood flow and rPSR relates to tumour microvascular leakiness, which is dependent on vascular permeability and the status of the BBB. Comparing the study on rPSR with the routinely used perfusion parameters, rCBV and rCBF proved our hypothesis that rPSR has the most diagnostic accuracy in differentiating different grades of glioma, especially low- and high-grade gliomas.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we observed that rPSR values have more diagnostic discriminative power than rCBV values, while both parameters have the potential to give different haemodynamic features of glioma. Moreover, it is observed that the rPSR obtained from the perfusion software of the Leonardo workstation (rPSRLeonardo) has shown slightly improved accuracy and differentiated more grades than the rPSR obtained by DSCoMAN software (rPSRDSCoMAN). Future studies with a higher patient population in each of the grades and subtypes of glioma may further improve the results. Understanding the reasons behind the actual changes in rPSR and the multiple competing mechanisms that take place when the contrast agent passes still remains a subject of interest for study.

FUNDING

One of the authors (SKA) has been awarded a grant from the government of Kerala in the form of a fellowship.

Contributor Information

K A Smitha, Email: mithamahesh@gmail.com.

A K Gupta, Email: gupta209@gmail.com.

R S Jayasree, Email: jayashreemenon@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sugahara T, Korogi Y, Kochi M, Ikushima I, Shigematu Y, Hirai T, et al. Usefulness of diffusion-weighted MRI with echo-planar technique in the evaluation of cellularity in gliomas. J Magn Reson Imaging 1999; 9: 53–60. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolecek TA, Propp JM, Stroup NE, Kruchko C. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2005-2009. Neuro Oncol 2012; 14: v1–49. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker C, Baborie A, Crooks D, Wilkins S, Jenkinson MD. Biology, genetics and imaging of glial cell tumours. Br J Radiol 2012; 84: S90–106. doi: 10.1259/bjr/23430927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lupo JM, Cha S, Chang SM, Nelson SJ. Dynamic susceptibility-weighted perfusion imaging of high-grade gliomas: characterization of spatial heterogeneity. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26: 1446–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Essock-Burns E, Lupo JM, Cha S, Polley MY, Butowski NA, Chang SM, et al. Assessment of perfusion MRI-derived parameters in evaluating and predicting response to antiangiogenic therapy in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2011; 13: 119–31. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noq143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakyemez B, Erdogan C, Ercan I, Ergin N, Uysal S, Atahan S. High-grade and low-grade gliomas: differentiation by using perfusion MR imaging. Clin Radiol 2005; 60: 493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2004.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sentürk S, Oğuz KK, Cila A. Dynamic contrast-enhanced susceptibility-weighted perfusion imaging of intracranial tumors: a study using a 3T MR scanner. Diagn Interv Radiol 2009; 15: 3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preul C, Kühn B, Lang EW, Mehdorn HM, Heller M, Link J. Differentiation of cerebral tumors using multi-section echo planar MR perfusion imaging. Eur J Radiol 2003; 48: 244–51. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(03)00050-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinchure S, Thomas B, Wangju S, Jolappara M, Kesavadas C, Kapilamoorthy TR, et al. Mean intensity curve on dynamic contrast-enhanced susceptibility-weighted perfusion MR imaging—review of a new parameter to differentiate intracranial tumors. J Neuroradiol 2011; 38: 199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cha S, Lupo JM, Chen MH, Lamborn KR, McDermott MW, Berger MS, et al. Differentiation of glioblastoma multiforme and single brain metastasis by peak height and percentage of signal intensity recovery derived from dynamic susceptibility-weighted contrast-enhanced perfusion MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 1078–84. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mangla R, Kolar B, Zhu T, Zhong J, Almast J, Ekholm S. Percentage signal recovery derived from MR dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging is useful to differentiate common enhancing malignant lesions of the rrain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 1004–10. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomsen H, Steffensen E, Larsson E-M. Perfusion MRI (dynamic susceptibility contrast imaging) with different measurement approaches for the evaluation of blood flow and blood volume in human gliomas. Acta Radiol 2012; 53: 95–101. doi: 10.1258/ar.2011.110242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cha S. Update on brain tumor imaging: from anatomy to physiology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 475–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masters LT, Pryor JC, Nelson PK. Angiographic findings associated with intra-axial intracranial tumors. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 1996; 6: 739–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osborn AG. Neoplasm mass effects. In: Osborn AG, ed. Diagnostic cerebral angiography. 2nd edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. pp. 313–40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wickborn I. Tumor circulation. In: Newton TH, Potts DG, eds. Radiology of the skull and brain. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1974. pp. 2257–85. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zierler KL. Theoretical basis of indicator-dilution methods for measuring flow and volume. Circ Res 1962; 10: 393–407. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.10.3.393 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cha S, Tihan T, Crawford F, Fischbein NJ, Chang S, Bollen A, et al. Differentiation of low-grade oligodendrogliomas from low-grade astrocytomas by using quantitative blood-volume measurements derived from dynamic susceptibility contrast-enhanced MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26: 266–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito M, Lammertsma AA, Wise RJ, Bernardi S, Frackowiak RS, Heather JD, et al. Measurement of regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen utilisation in patients with cerebral tumours using 15O and positron emission tomography: analytical techniques and preliminary results. Neuroradiology 1982; 23: 63–74. doi: 10.1007/BF00367239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas DGT. The application of positron emission tomography in studies of human cerebral glioma. In: Paoletti PKT, Walker MD, Butti G, Pezzotta S, eds. Neurooncology. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer; 1991. pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]