Abstract

Background

Following reports of increasing emergency department (ED) visits for unsupervised pediatric medication exposures in the 2000s, renewed efforts to improve safety packaging and education were initiated. National data on current trends and implicated medications can help further target interventions.

Methods

We used nationally-representative data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System–Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project (2004–2013) to assess trends in ED visits for unsupervised medication exposures in children aged <6 years. For 2010–2013, we identified the dosage form and prescription status of implicated medications.

Results

Based on 13,268 cases, there were an estimated 640,161 ED visits (95% confidence interval: 512,885–767,436) for unsupervised medication exposures from 2004–2013. From 2004–2010, the number of ED visits for unsupervised exposures increased by an average of 5.7% annually, peaking at 75,842. After 2010, this trend reversed and ED visits decreased by an average of 6.7% annually to 59,092 estimated visits in 2013. From 2010–2013, 91.0% of ED visits for unsupervised exposures involved 1 medication, most commonly an oral prescription solid (45.9%), oral over-the-counter (OTC) solid (22.3%), or oral OTC liquid (12.4%); 9.0% of visits involved >1 medication. Over 260 different prescription solids were implicated; opioids (13.8%) and benzodiazepines (12.7%) were the most commonly implicated classes. Four medications were implicated in 91.2% of OTC liquid exposure visits: acetaminophen (32.9%), cough and cold remedies (27.5%), ibuprofen (15.7%), and diphenhydramine (15.6%).

Conclusions

Targeting prevention efforts based on harm frequency and intervention feasibility can lead to continued reductions in ED visits for pediatric medication exposures.

Keywords: drug packaging, medication safety, pediatric poisoning, unintentional overdose

Unsupervised medication exposures remain a significant but preventable cause of pediatric harm. For decades, the cornerstones of primary prevention have been child-resistant (CR) packaging (required for most medications in the United States)1 and education about safe medication storage. Despite great success in reducing the numbers of pediatric poisoning deaths,2 each year approximately a half million calls are made to poison centers after a young child accesses medication without adult supervision,3–5 and from 2001–2008 the number of pediatric exposure calls that resulted in emergency department (ED) evaluation increased 24–32% depending on medication type.6 Since then, renewed efforts to improve child safety packaging and education were initiated,7, 8 and reducing ED visits for unintentional medication overdoses among young children was adopted as a Healthy People 2020 goal for the nation.9

We used nationally-representative surveillance data to assess trends in ED visits for unsupervised medication exposures among children aged <6 years from 2004–2013. To help target prevention efforts, we characterized the medications implicated in ED visits from 2010–2013 by dosage form and prescription status and identified those most commonly implicated.

METHODS

Data Sources

National estimates of ED visits for unsupervised pediatric medication exposures were based on data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance (NEISS-CADES) project. Initiated in 2004, NEISS-CADES is an active public health surveillance system based on a nationally-representative sample of hospitals with at least 6 beds and a 24-hour ED in the United States and its territories and has been described in detail.10, 11 Briefly, trained abstractors at 57–63 participating hospitals, depending on the year, review the clinical diagnoses and supporting documentation in all ED visit medical records to identify clinician-diagnosed adverse drug events (ADEs) and up to two medications implicated in each adverse event. Abstractors record patient demographics, verbatim clinical diagnoses, information about implicated medications, and discharge disposition. When documented, abstractors also record narrative details, including precipitating circumstances, clinical manifestations, laboratory testing, and treatments administered.

Definitions

Unsupervised exposure cases were defined as ED visits from January 1, 2004 through December 31, 2013 by a child aged <6 years for accessing medication without caregiver permission or oversight, as documented by treating clinicians. Medications included any prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) medication, herbal/dietary supplement, or vaccine. Hospitalizations included inpatient admissions, transfers to other hospitals, and observation admissions.

From 2010–2013, ED visits for unsupervised exposures were categorized by dosage form and prescription status (medication type). Dosage forms were categorized as oral liquids (e.g., suspensions, syrups), oral solids (e.g., tablets, capsules), and non-oral medications (e.g., ointments, inhalers) based on details provided in case narratives or by searching drug databases and manufacturer websites for available dosage forms.12, 13 If medications could have been oral solids or oral liquids (e.g., “ingested acetaminophen”), they were categorized as unspecified oral dosage form. If medications could have been oral or non-oral dosage forms (e.g., “ingested grandma’s meds”), they were categorized as unspecified dosage form.

For this analysis, medications only available by prescription were categorized as prescription and those available only over-the counter were categorized as being available OTC (hereafter “OTC”). Medications available either over-the-counter or by prescription were categorized based on case details such as brand name or dosage strength (e.g., “ibuprofen 800 mg tabs”); in the absence of clarifying details, they were categorized as OTC. Medications described generally (e.g., “eye drops,” “white pill”) were categorized as unspecified prescription status. OTC medications were further categorized as pediatric products, adult/family products, or unspecified age group products based on the product name, dosage form, or narrative details (e.g., “children’s acetaminophen”).

For ED visits without specific documentation of pediatric self-administration, caregiver administration was assumed. These included adverse reactions, allergic reactions, supratherapeutic effects, medication errors, and secondary effects (e.g., choking).

Statistical Analysis

NEISS-CADES cases are weighted based on the inverse probability of selection, adjusted for nonresponse and post-stratified to adjust for the number of annual hospital ED visits.14 National estimates of ED visits and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the SURVEYMEANS procedure in SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute) to account for weighting and complex sample design. Population-based rates were calculated using intercensal estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau.

NEISS-CADES estimates based on <20 cases or total estimates <1200 for the study period are considered statistically unreliable and are not shown. Similarly, estimates with a coefficient of variation greater than 30% are noted.

Trend analyses were conducted using piecewise (segmented) regression with the natural logarithm of the annual national estimate or the estimated annual rate as the dependent variable and year as the independent variable. Joinpoint Regression software (version 4.1.1, National Cancer Institute) was used to identify potential inflection points and to test for significant trends, accounting for variances of estimates.15 Two-sided P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

For detailed analysis of implicated medications (2010–2013), average annual estimates of ED visits for the 4-year period were calculated. Analysis of types of implicated medications (dosage form and prescription status) was limited to visits involving one medication.

RESULTS

Patient and Case Characteristics 2004–2013

Based on 13,268 cases, an estimated 640,161 ED visits (95% CI: 512,885–767,436) were made from 2004–2013 after a child aged <6 years accessed medication without caregiver oversight (Table 1). During this time, there were a similar number of ED visits for ADEs following caregiver administration (623,381; 95% CI: 445,931–800,831) in this age group. Two-thirds of ED visits (69.8%; 95% CI: 68.5% – 71.0%) for unsupervised medication exposure involved 1- or 2-year old children, while most visits for ADEs following caregiver administration involved children aged ≤ 1 year (57.1%; 95% CI: 54.5% – 59.7%). ED visits for unsupervised exposures were 3-times more likely to result in hospitalization (18.5% vs 6.0%) compared with visits for ADEs following caregiver administration. Nearly all unsupervised exposure visits involved oral intake (97.9%; 95% CI: 97.6% – 98.3%).

Table 1.

Number of Cases and National Estimates of Emergency Department Visits for Adverse Drug Events (ADEs) by Children Aged <6 Years, United States, 2004–2013a

| Patient and Case Characteristics | Emergency Department Visits for Unsupervised Medication Exposures | Emergency Department Visits for Caregiver Administration ADEs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Cases | 10-Year National Estimate | Cases | 10-Year National Estimate | |||||

| No. | No. | % | 95% CI | No. | No. | % | 95% CI | |

| Age | ||||||||

| <1 year | 764 | 36,529 | 5.7 | (5.0 – 6.4) | 4,129 | 194,641 | 31.2 | (29.5 – 33.0) |

| 1 year | 4,158 | 202,952 | 31.7 | (30.2 – 33.2) | 3,520 | 161,309 | 25.9 | (24.1 – 27.7) |

| 2 years | 5,016 | 243,598 | 38.1 | (37.0 – 39.1) | 1,612 | 74,104 | 11.9 | (11.2 – 12.6) |

| 3 years | 2,094 | 102,109 | 16.0 | (14.9 – 17.0) | 1,284 | 58,157 | 9.3 | (8.5 – 10.2) |

| 4 years | 874 | 39,535 | 6.2 | (5.6 – 6.7) | 1,655 | 75,448 | 12.1 | (10.8 – 13.4) |

| 5 years | 362 | 15,438 | 2.4 | (2.0 – 2.8) | 1,344 | 59,722 | 9.6 | (8.3 – 10.9) |

|

| ||||||||

| Sexb | ||||||||

| Girls | 6,279 | 304,203 | 47.5 | (46.3 – 48.7) | 6,226 | 291,222 | 46.7 | (45.6 – 47.8) |

| Boys | 6,986 | 335,731 | 52.4 | (51.3 – 53.6) | 7,316 | 332,009 | 53.3 | (52.1 – 54.4) |

|

| ||||||||

| Dispositionc | ||||||||

| Admitted, transferred, or held for observation | 3,530 | 118,739 | 18.5 | (14.1 – 23.0) | 1,634 | 37,672d | 6.0 | (2.7 – 9.4) |

| Treated and released or left against medical advice | 9,735 | 521,314 | 81.4 | (77.0 – 85.9) | 11,908 | 585,693 | 94.0 | (90.6 – 97.3) |

| Total 10-Year Estimate | 13,268 | 640,161 | 100.0 | 13,544 | 623,381 | 100.0 | ||

Estimates based on the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, 2004–2013.

Patient sex was missing for 3 cases involving unsupervised exposure and 2 cases of caregiver administration ADEs.

Disposition was missing for 3 cases involving unsupervised exposure and 2 cases of caregiver administration ADEs.

Coefficient of variation = 31.1%.

Trends 2004–2013

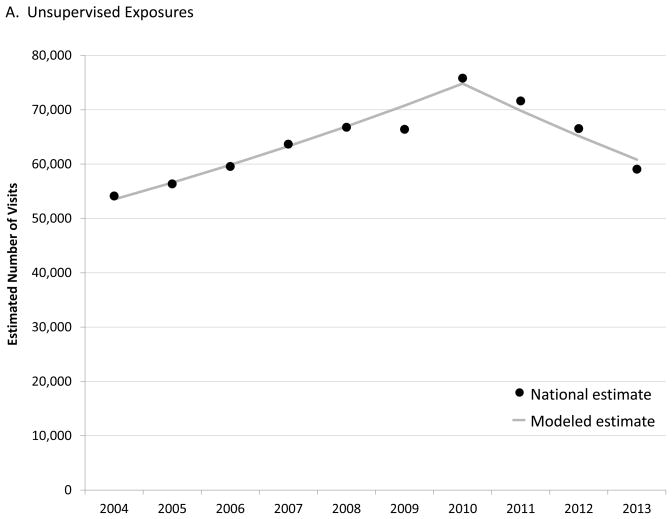

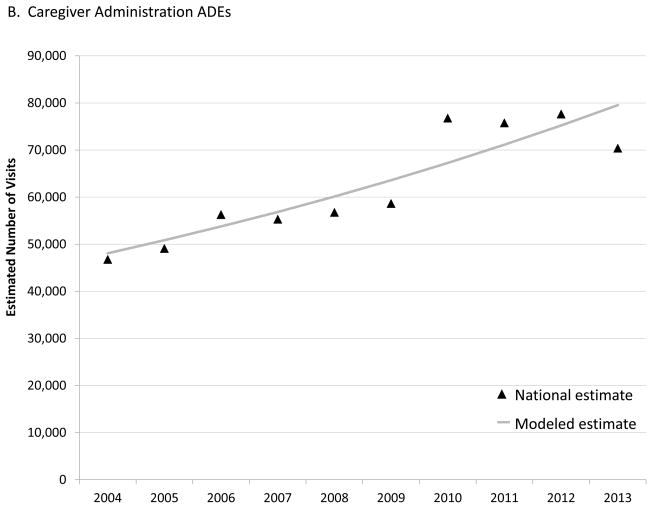

From 2004–2010, the number of estimated ED visits for unsupervised medication exposures among children aged <6 years increased by an annual percentage change (APC) of 5.7% (95% CI: 4.4% – 7.1%), from 54,140 visits (95% CI: 42,277–66,002) in 2004 to 75,842 visits (95% CI: 58,228–93,455) in 2010 (Figure 1A). After 2010, the APC in estimated ED visits for unsupervised exposures significantly decreased by 6.7% (95% CI: −9.9% – −3.3%) each year to 59,092 visits (95% CI: 44,912–73,272) in 2013. In contrast, the number of estimated visits for ADEs following caregiver administration increased over the entire 10-year period with an estimated APC of 5.8% (95% CI: 3.5% – 8.1%), from 46,779 visits (95% CI: 28,818–64,741) in 2004 to 70,390 visits (95% CI: 48,436–92,343) in 2013 (Figure 1B). Population changes did not alter these trends, with the rate of ED visits for unsupervised medication exposures increasing by an APC of 5.2% (95% CI: 4.0% – 6.5%) from 2004 to 2010 then decreasing by 6.2% (95% CI: −9.2% – −3.0%), while the rate of ED visits for ADEs following caregiver administration increased by an APC of 5.6% (95% CI: 3.4% – 7.8%) throughout the period.

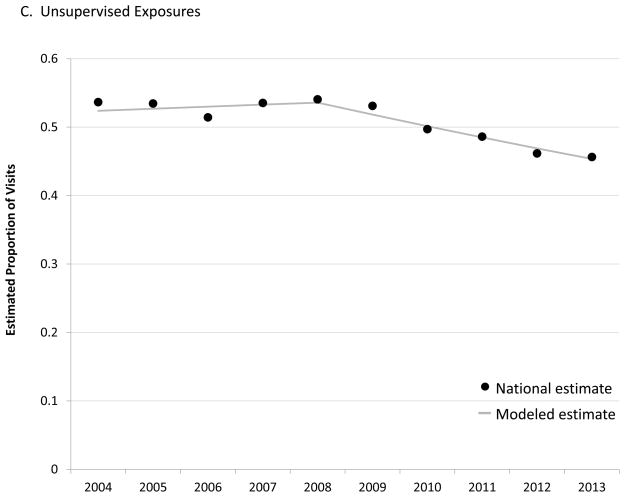

Figure 1.

Trends in Emergency Department (ED) Visits for Adverse Drug Events (ADEs), Children Aged <6 Years, United States, 2004–2013. A, Estimated number of ED visits for unsupervised medication exposures. B, Estimated number of ED visits for caregiver administration ADEs. C, Estimated proportion of ED visits for ADEs attributed to unsupervised exposures.

Most ED visits for ADEs were attributed to unsupervised exposures during the first part of the study period. However, joinpoint regression identified a significant decline in the proportion of visits attributed to unsupervised exposures after 2008, with an APC of −3.3% (95% CI: −4.9% – −1.7%) through 2013 (P <.001) (Figure 1C). In 2013, 45.6% (95% CI: 41.0% – 50.3%) of ED visits for ADEs among children aged <6 years were attributed to unsupervised exposures.

Types of Implicated Medications 2010–2013

Based on 5,524 cases, one medication was accessed in 91.0% (95% CI: 89.7% – 92.3%) of ED visits for unsupervised exposures from 2010–2013. Of visits involving one medication, nearly three-fourths (72.5%) involved an oral solid medication and 15.4% involved an oral liquid medication (Table 2). Approximately half of these visits (51.2%) were attributed to a prescription medication and 43.4% were attributed to an OTC medication. Among the 9.0% of visits (95% CI: 7.7% – 10.3%) for unsupervised exposures attributed to >1 medication, 91.5% (95% CI: 87.2% – 95.8%) involved 2 oral solid medications.

Table 2.

National Estimates of Types of Medications Implicated in Emergency Department Visits for Unsupervised Exposures Involving a Single Medication by Children Aged <6 Years, United States, 2010–2013a

| Medication Type | Emergency Department Visits Annual National Estimate |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | 95% CI | |

| Medication Dosage Form | |||

| Oral Solid (e.g., tablet) | 45,079 | 72.5 | (70.1 – 74.9) |

| Oral Liquid | 9,546 | 15.4 | (13.5 – 17.2) |

| Unspecified Oralb | 2,134 | 3.4 | (2.0 – 4.8) |

| Non-oral Medication | 5,104 | 8.2 | (7.2 – 9.3) |

| Unspecified Dosage Form | 305c | 0.5 | (0.2 – 0.8) |

|

| |||

| Medication Prescription Status | |||

| Prescription | 31,802 | 51.2 | (49.2 – 53.1) |

| Over-the-Counter | 26,967 | 43.4 | (41.6 – 45.2) |

| Unspecified Prescription Status | 3,399 | 5.5 | (4.3 – 6.7) |

Estimates based on the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, 2010–2013.

Unspecified Oral denotes cases in which the child accessed an oral medication, but there was not enough information to determine whether it was an oral liquid or an oral solid dosage form.

Coefficient of variation = 30.6%.

Oral prescription solid medications (45.9%), oral OTC solids (22.3%), and oral OTC liquids (12.4%) accounted for four-fifths of ED visits for unsupervised exposures attributed to one medication (Table 3). Among ED visits for unsupervised exposure to a solid dose medication, twice as many annual visits were attributed to a prescription product as an OTC product ([28,540; 95% CI: 22,517–34,563] vs [13,870; 95% CI: 10,850–16,889]). In contrast, among visits for unsupervised exposure to a liquid medication, an OTC liquid was implicated in 5.3-times as many annual visits as a prescription liquid ([7,736; 95% CI: 6,067–9,405] vs [1,448; 95% CI: 968–1,929]).

Table 3.

Cross-tabulation of Types of Medications Implicated in Emergency Department Visits for Unsupervised Exposures Involving a Single Medication by Children Aged <6 Years, United States, 2010–2013a

| Medication Prescription Status | Medication Dosage Form

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral Solid (e.g., tablets) Annual National Estimate |

Oral Liquid Annual National Estimate |

Unspecified Oralb Annual National Estimate |

Non-oral Medication Annual National Estimate |

|||||||||

| No. | % | 95% CI | No. | % | 95% CI | No. | % | 95% CI | No. | % | 95% CI | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Prescription | 28,540 | 45.9 | (43.9 – 47.9) | 1,448 | 2.3 | (1.6 – 3.0) | 338 | 0.5 | (0.2 – 0.8) | 1,431 | 2.3 | (1.8 – 2.8) |

| Over-the-Counter | 13,870 | 22.3 | (20.3 – 24.3) | 7,736 | 12.4 | (11.0 – 13.9) | 1,763 | 2.8 | (1.6 – 4.1) | 3,536 | 5.7 | (4.9 – 6.5) |

| Unspecified | 2,670 | 4.3 | (3.3 – 5.3) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

Estimates based on the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, 2010–2013. Estimates based on < 20 cases or with a total 4-year estimate <1200 are not shown (--). 29 ED visits involving a medication in which the dosage form was unspecified are not shown.

Unspecified Oral denotes cases in which the child accessed an oral medication, but there was not enough information to determine whether it was an oral liquid or an oral solid dosage form.

Frequently Implicated Medications 2010–2013

Pediatric products were involved in over four-fifths of ED visits for OTC liquid medication exposures (85.2%; 95% CI: 80.3% – 90.1%); whereas adult/family products were involved in over two-thirds of visits for OTC solid medication exposures (70.1%; 95% CI: 66.5% – 73.6%).

Children aged ≤2 years were involved in 79.9% (95% CI: 77.5% – 82.4%) of visits for oral prescription solid medication exposures; children aged ≤1 year were involved in 42.3% (95% CI: 38.9% – 45.7%). Children aged ≤2 years were involved in a similar proportion of visits for oral OTC solid medication exposures (73.4%; 95% CI: 69.9% – 76.9%). However, slightly older children were involved in visits for oral OTC liquid medication exposures, with 60.3% (95% CI: 54.8% – 65.9%) involving children aged ≤2 years.

Over 260 individual medications were implicated in oral prescription solid medication exposure cases. Opioids were the most commonly implicated medication class in ED visits involving prescription solid exposures (4,661 annual visits [13.8%]), with 1,285 buprenorphine-containing product visits (95% CI: 803–1,767), 991 oxycodone-containing product visits (95% CI: 466–1,515), 864 tramadol-containing product visits (95% CI: 507–1,220), and 856 hydrocodone-containing product visits (95% CI: 482–1,230) annually (Table 4). Benzodiazepines were the second most commonly implicated class in ED visits involving prescription solid exposures (4,293 annual visits [12.7%]), with 1,999 clonazepam exposure visits (95% CI: 1,218–2,780) and 905 alprazolam visits (95% CI: 456–1,354) annually. The ten most frequently implicated medications, alone or in combination with others, were involved in 32.2% (95% CI: 28.6% – 35.7%) of visits attributed to prescription solid medication exposures.

Table 4.

National Estimates of Medications Commonly Implicated in Emergency Department Visits for Unsupervised Exposures by Children Aged <6 Years, United States, 2010–2013a

| Most Commonly Implicated Medications | Emergency Department Visits Annual National Estimate |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | 95% CI | |

| Oral Prescription Solid Medications | |||

| Opioid analgesics | 4,661 | 13.8 | (11.8 – 15.8) |

| Benzodiazepines | 4,293 | 12.7 | (10.8 – 14.7) |

| Antidepressants | 3,594 | 10.7 | (8.9 – 12.4) |

| Beta blockers | 2,080 | 6.2 | (5.0 – 7.4) |

| Amphetamine-related stimulants | 1,965 | 5.8 | (4.5 – 7.1) |

| Centrally-acting antiadrenergics | 1,847 | 5.5 | (4.0 – 6.9) |

| Anticonvulsants | 1,715 | 5.1 | (4.0 – 6.2) |

| Oral hypoglycemics | 1,454 | 4.3 | (2.6 – 6.0) |

| Skeletal muscle relaxants | 1,437 | 4.3 | (3.2 – 5.3) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 1,377 | 4.1 | (2.6 – 5.5) |

| Atypical antipsychotics | 1,318 | 3.9 | (2.8 – 5.0) |

| Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors | 1,239 | 3.7 | (2.8 – 4.5) |

|

| |||

| Oral OTC Solid Medications | |||

| Acetaminophen | 3,017 | 19.2 | (15.6 – 22.7) |

| Vitamins/Minerals | 2,687 | 17.1 | (13.9 – 20.3) |

| Ibuprofen | 1,663 | 10.6 | (8.1 – 13.0) |

| Herbals/Alternative therapies | 1,629 | 10.4 | (8.0 – 12.7) |

| Acetaminophen and/or aspirin-containing analgesic combinations | 1,170 | 7.4 | (5.5 – 9.3) |

| Aspirin | 1,021 | 6.5 | (3.8 – 9.2) |

| Diphenhydramine | 906 | 5.8 | (4.0 – 7.5) |

| Second generation antihistamines | 706 | 4.5 | (3.1 – 5.9) |

| Cough and cold remedies | 678 | 4.3 | (2.4 – 6.2) |

| Antiulcer agents | 506 | 3.2 | (1.6 – 4.9) |

|

| |||

| Oral OTC Liquid Medications | |||

| Acetaminophen | 2,607 | 32.9 | (25.6 – 40.1) |

| Cough and cold remedies | 2,182 | 27.5 | (20.2 – 34.9) |

| Ibuprofen | 1,248 | 15.7 | (11.8 – 19.7) |

| Diphenhydramine | 1,235 | 15.6 | (11.4 – 19.8) |

Estimates based on the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance project, 2010–2013. Medications implicated in at least 3% of estimated ED visits for the 3 most commonly implicated dosage form and prescription status combinations are listed.

Vitamins/minerals or herbal/alternative remedies were implicated in one-quarter of visits for OTC solid medication exposures annually (4,206; 95% CI: 3,334–5,077). Analgesic products containing acetaminophen alone or in combination were implicated in another one-quarter of visits for OTC solid medication exposures annually (4,114; 95% CI: 2,832–5,397). The specific ingredients/combinations were not always identified for ED visits attributed to vitamins/minerals; however, at least one-third of these visits involved an iron-containing product (897 annual visits; 95% CI: 536–1,258).

Four medications, alone or in combination with others, were implicated in 91.2% (95% CI: 88.7% – 93.6%) of ED visits for oral OTC liquid exposures, with 2,607 visits (32.9%) involving single-ingredient acetaminophen, 2,182 visits (27.5%) involving cough and cold remedies, 1,248 visits (15.7%) involving single-ingredient ibuprofen, and 1,235 visits (15.6%) involving single-ingredient diphenhydramine annually. Pediatric products were implicated in 86.9% (95% CI: 81.9%–91.9%) of visits involving these 4 OTC liquid medications.

Notably, these 4 medications were also implicated in 39.6% (95% CI: 35.4% – 43.8%) of oral OTC solid exposure visits and 82.5% (95% CI: 75.4% – 89.6%) of visits involving oral OTC medications for which solid or liquid dosage form was unspecified. Unintentional epinephrine autoinjector needle sticks were implicated in one-half of ED visits (751 annual visits; 95% CI: 502–1,000) for non-oral prescription medication exposures, while topical agents were implicated in nearly two-thirds of visits (2,269 annual visits; 95% CI: 1,675–2,864) for non-oral OTC medication exposures.

DISCUSSION

An estimated 640,000 ED visits were made in the United States from 2004–2013 after a child aged <6 years accessed medication without caregiver permission or oversight; nearly 20% resulted in hospitalization. Previous studies reported rising numbers of ED visits and calls to poison centers for pediatric medication exposures throughout the 2000s.6, 16, 17 However, timely, nationally-representative data suggest that ED visits for unsupervised exposures are now decreasing, from a peak of approximately 76,000 estimated ED visits in 2010 to 59,000 visits in 2013.

The 22% decline in estimated number of ED visits for unsupervised medication exposures beginning in 2010 is unlikely surveillance artifact or secular trend in ED utilization. We found that the estimated number of ED visits for ADEs following caregiver administration of medication to children aged <6 years increased through the study period, including 2010–2013 when unsupervised exposures were declining. Although unsupervised exposures are no longer the most common cause of ED visits for ADEs among young children, accounting for 46% of visits in 2013, national data on types of medications implicated in unsupervised exposures will continue to be helpful for targeting interventions and achieving further reductions in ED visits.

Addressing oral liquid medication exposures is a logical next step to continue to reduce pediatric medication exposures because these exposures commonly involve a relatively small number of pediatric OTC products and efficacious interventions are available. Acetaminophen, ibuprofen, diphenhydramine, or cough and cold remedies were implicated in 91% of ED visits for OTC liquid medication exposures, accounting for 7,200 visits annually from 2010–2013 and 87% involved pediatric formulations. While nearly all of these medications require CR packaging,1 like most medications in the United States, they are commonly sold in bottles that require caregivers to immediately and fully re-secure the safety cap after every use. Newer safety packaging that incorporates passive safety features that do not rely solely on active engagement by caregivers (e.g., flow restrictors, unit-dose packaging) has been demonstrated to complement CR packaging by providing a secondary safety barrier or a barrier around each dose.7, 18–20 Efficacy standards for restricted delivery systems such as flow restrictors are being developed,21 and while currently implemented on infants’ and some children’s single-ingredient acetaminophen products,22 a new draft guidance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends expanding use of such container features to prevent or limit pediatric exposures to all OTC pediatric liquid acetaminophen-containing products.23

Although approximately half of ED visits for medication exposures involved prescription solid medications, targeting interventions is more complex since these exposures involve a broader range of products, typically intended for adults, which are often re-packaged at retail pharmacies and are more easily transferred out of CR containers in the home. While just 1 pediatric medication, single-ingredient acetaminophen, was implicated in one-third of ED visits for OTC liquid exposures from 2010–2013, 10 medications combined accounted for one-third of visits for prescription solid exposures. With so many different implicated medications, packaging interventions could be targeted to medications that lead to high rates of pediatric exposure (disproportionate relative to use) and high severity.24 However, because prescription medications in solid dosage form are not likely prescribed to children aged <6 years, interventions to improve child safety should be balanced with usability and adherence by older users.25

Additionally, unlike with liquid medications, adults may leave solid dose medications outside of containers or transfer them to non-child-resistant containers to improve access, portability or adherence. It is notable that 80% of prescription solid exposure visits were made by children aged ≤ 2 years, and 42% were made by those aged ≤ 1 year, well below the youngest participants (aged 3½ years) in Poison Prevention Packaging Act protocol testing.26 It is unlikely that many 2-year-olds, much less 1-year-olds, can open fully-secured CR containers, suggesting they accessed medications from containers that were not fully-secured, medications from containers without CR features (e.g., daily or weekly pill minders), loose pills intentionally left out (e.g., for the next dose) or dropped pills. As with liquid medications, CR unit-dose packaging can prevent or limit pediatric solid medication exposures since the CR protection for each unit remains in place until opened. A recent study of poison centers calls found significantly higher rates of pediatric exposure for buprenorphine/naloxone tablets packaged in multidose bottles compared with buprenorphine/naloxone film packaged in unit-dose pouches, suggesting that differences in packaging may have affected the rates of exposure calls.27 While incorporation of passive protection features in medication packaging may limit solid dosage exposures, additional innovations, and complementary educational messages may be needed to reduce exposures when medications are removed from original packaging.

These findings should be interpreted in the context of the limitations of public health surveillance data. First, because data were collected in an emergency setting, detailed information about medication dosage strength or brand name were not always documented, thus there is potential for misclassification of medication type. Similarly, the specific circumstances surrounding the exposures (e.g., type of container from which medication was accessed) were not always documented, but could help further target interventions.28 Second, trained abstractors report the first 2 implicated medications for each ED visit; if additional medications were involved they were not systematically collected nor analyzed. However, only 9% of cases involved >1 medication, and fewer would involve >2 medications. Third, although the data suggest a decreasing trend in ED visits for unsupervised exposure, analyses were limited to the 10 years for which data were available. Nonetheless, active surveillance is generally preferred to voluntary reporting for monitoring trends and should continue to monitor effects of expanded interventions.29, 30 Fourth, although medication utilization was not assessed, future studies could identify specific medications, with disproportionate rates of unsupervised exposure relative to use and assess medication-specific trends.

CONCLUSION

The observed decline in estimated ED visits for unsupervised exposure cannot be attributed to specific interventions; however it coincides with renewed prevention efforts, including those of the PRevention of Overdoses and Treatment Errors in Children Taskforce (PROTECT) Initiative and partners.8, 22, 31–34 Initiated in 2008, PROTECT is a public-private partnership led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that aims to prevent unsupervised medication exposures by encouraging development and implementation of innovative exposure-limiting packaging (e.g., flow restrictors) and by updating and disseminating evidence-based educational messages on safe use and storage of medications that resonate with new generations of caregivers. To maintain or even accelerate reductions in preventable harm from pediatric medication exposures will require continuing efforts to address the medications that lead to frequent and disproportionate harm, including interventions that balance efficacy and feasibility.

What’s Known on This Subject

Unsupervised medication exposures increased during the previous decade, despite child-resistant packaging and caregiver education. To achieve the Healthy People 2020 objective of reducing emergency department visits for unintentional pediatric medication overdoses, targeted interventions including improved safety packaging may be needed.

What This Study Adds

Since 2010, emergency department visits for unsupervised medication exposures started to decrease. Most visits involved solid dose medications, typically for adult use. Most liquid medication exposure visits involved 4 over-the-counter pediatric products, and may be more readily amenable for interventions.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: No external funding was secured for this study.

We thank Ms Kathleen Rose, RN, BSN (contractor for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and Dr Kelly Weidenbach, DrPH (contractor for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at the time of data collection) and Mr Herman Burney, MS and Mr Ray Colucci, MSN, of the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission for assistance with data collection and processing. We also thank Likang Xu, MD and Andrew I. Geller, MD from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for statistical consultation and thoughtful review of the manuscript, respectively.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ADE

adverse drug event

- APC

annual percentage change

- CI

confidence interval

- CR

child-resistant

- ED

emergency department

- NEISS-CADES

National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance

- OTC

over-the-counter

- PROTECT

PRevention of Overdoses and Treatment Errors in Children Taskforce

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Potential Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributors’ Statement

Maribeth C. Lovegrove: conceptualized and designed the study, conducted the analyses, contributed to interpretation of data, drafted the initial manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Nina J. Weidle: contributed to acquisition and interpretation of data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Daniel S. Budnitz: conceptualized and designed the study, contributed to acquisition and interpretation of data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

References

- 1.16 CFR § 1700.14 Subchapter E—Poison Prevention Packaging Act Of 1970 Regulations, Part 1700—Poison Prevention Packaging. 38 FR 21247, Aug. 7, 1973, as amended at 41 FR 22266, June 2, 1976; 48 FR 57480, Dec. 30, 1983.

- 2.Rodgers GB. The safety effects of child-resistant packaging for oral prescription drugs. Two decades of experience. JAMA. 1996;275(21):1661–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, Rumack BH, Dart RC. 2011 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 29th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2012;50(10):911–1164. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2012.746424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, Bailey JE, Ford M. 2012 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 30th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2013;51(10):949–1229. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.863906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, McMillan N, Ford M. 2013 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 31st Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2014;52(10):1032–1283. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2014.987397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bond GR, Woodward RW, Ho M. The growing impact of pediatric pharmaceutical poisoning. J Pediatr. 2012;160(2):265–270. e261. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budnitz DS, Salis S. Preventing medication overdoses in young children: an opportunity for harm elimination. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):e1597–1599. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agarwal M, Williams J, Tavoulareas D, Studnek JR. A brief educational intervention improves medication safety knowledge in grandparents of young children. AIMS Public Health. 2015;2(1):44–55. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2015.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.HealthyPeople.gov. [Accessed January 20, 2015];Healthy People 2020 Medical Product Safety Objectives. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/medical-product-safety/objectives.

- 10.Jhung MA, Budnitz DS, Mendelsohn AB, Weidenbach KN, Nelson TD, Pollock DA. Evaluation and overview of the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System-Cooperative Adverse Drug Event Surveillance Project (NEISS-CADES) Med Care. 2007;45(10 Supl 2):S96–102. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318041f737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budnitz DS, Pollock DA, Weidenbach KN, Mendelsohn AB, Schroeder TJ, Annest JL. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. 2006;296(15):1858–1866. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Facts & Comparisons®. Wolters Kluwer Health; [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orange Book. Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations. U.S. Food and Drug Administration; [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroeder T, Ault K. [Accessed February 12, 2015];The NEISS sample (design and implementation) 1997 to present. Available at: http://www.cpsc.gov//PageFiles/106617/2001d011-6b6.pdf.

- 15.Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN. Permutation tests for joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med. 2000;19(3):335–351. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<335::aid-sim336>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burghardt LC, Ayers JW, Brownstein JS, Bronstein AC, Ewald MB, Bourgeois FT. Adult prescription drug use and pediatric medication exposures and poisonings. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):18–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spiller HA, Beuhler MC, Ryan ML, Borys DJ, Aleguas A, Bosse GM. Evaluation of changes in poisoning in young children: 2000 to 2010. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(5):635–640. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31828e9d00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC. The last mile: taking the final steps in preventing pediatric pharmaceutical poisonings. J Pediatr. 2012;160(2):190–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lovegrove MC, Hon S, Geller RJ, Rose KO, Hampton LM, Bradley J, et al. Efficacy of flow restrictors in limiting access of liquid medications by young children. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1134–1139. e1131. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoenewald S, Kuffner E. Unit dose packaging may decrease amount of over-the-counter (OTC) medicine ingested following accidental unsupervised ingestions (AUIs) [NACCT abstract 271] Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2010;48:660. [Google Scholar]

- 21.ASTM International. [Accessed March 6, 2015];Flow Control Devices. ASTM Standardization News. 2013 Jul-Aug; Available at: http://www.astm.org/sn/update/liquid-medicine-flow-control-devices-ja13.html.

- 22.Consumer Healthcare Products Association. [Accessed March 6, 2015];OTC industry announces voluntary transition to one concentration of single-ingredient pediatric liquid acetaminophen medicines [press release] 2011 May 4; Available at: http://www.chpa.org/05_04_11_pedacet.aspx.

- 23.US Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed March 6, 2015];Draft guidance for industry: over-the-counter pediatric liquid drug products containing acetaminophen. 2014 Oct; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM417568.pdf.

- 24.Lovegrove MC, Mathew J, Hampp C, Governale L, Wysowski DK, Budnitz DS. Emergency hospitalizations for unsupervised prescription medication ingestions by young children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1009–1016. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nikolaus T, Kruse W, Bach M, Specht-Leible N, Oster P, Schlierf G. Elderly patients’ problems with medication. An in-hospital and follow-up study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;49(4):255–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00226324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.16 CFR § 1700.20 Subchapter E—Poison Prevention Packaging Act Of 1970 Regulations, Part 1700—Poison Prevention Packaging. 38 FR 21247, Aug. 7, 1973, as amended at 60 FR 37735, 37738, July 22, 1995.

- 27.Lavonas EJ, Banner W, Bradt P, Bucher-Bartelson B, Brown KR, Rajan P, et al. Root causes, clinical effects, and outcomes of unintentional exposures to buprenorphine by young children. J Pediatr. 2013;163(5):1377–1383. e1371–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoenewald S, Ross S, Bloom L, Shah M, Lynch J, Lin CL, et al. New insights into root causes of pediatric accidental unsupervised ingestions of over-the-counter medications. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2013;51(10):930–936. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.855314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teutsch SM. Considerations in planning a surveillance system. In: Lee LM, Teutsch SM, Thacker SB, StLouis ME, editors. Principles & practice of public health surveillance. 3. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dal Pan GJ, Lindquist M, Gelperin K. Postmarketing spontaneous pharmacovigilance reporting systems. In: Strom BL, Kimmel SE, Hennessy S, editors. Pharmacoepidemiology. 5. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. pp. 150–151. [Google Scholar]

- 31.UpAndAway.org. [Accessed March 6, 2015];Put your medicines up and away and out of sight. Available at: http://www.upandaway.org/

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed March 9, 2015];The PROTECT Initiative: advancing children’s medication safety. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/MedicationSafety/protect/protect_Initiative.html.

- 33.American Academy of Pediatrics. [Accessed March 23, 2015];Medication Safety (Video) Available at: http://www.healthychildren.org/English/safety-prevention/at-home/medication-safety/Pages/Medication-Safety-Video.aspx.

- 34.Baker J, Mickalide A. Safe storage, safe dosing, safe kids: a report to the nation on safe medication. Washington, DC: Safe Kids Worldwide; Mar, 2012. [Google Scholar]