Abstract

We analyzed the occurrence and mechanisms of fusidic acid resistance present in staphylococci isolated from 59 healthy volunteers. The fingers of the volunteers were screened for the presence of staphylococci, and the collected isolates were tested for resistance to fusidic acid. A total of 34 fusidic acid resistant staphylococcal strains (all were coagulase-negative) were isolated from 22 individuals (22/59, 37.3%). Examination of the resistance genes revealed that acquired fusB or fusC was present in Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus capitis subsp. urealyticus, Staphylococcus hominis subsp. hominis, Staphylococcus warneri and Staphylococcus haemolyticus. Resistance islands (RIs) carrying fusB were found in S. epidermidis and S. capitis subsp. urealyticus, while staphylococcal chromosome cassette (SCC)-related structures harboring fusC were found in S. hominis subsp. hominis. Genotypic analysis of S. epidermidis and S. hominis subsp. hominis indicated that the fus elements were disseminated in diverse genetic strain backgrounds. The fusC elements in S. hominis subsp. hominis strains were highly homologous to SCCfusC in the epidemic sequence type (ST) 239/SCCmecIII methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) or the pseudo SCCmec in ST779 MRSA. The presence of acquired fusidic acid resistance genes and their genetic environment in commensal staphylococci suggested that the skin commensal staphylococci may act as reservoir for fusidic acid resistance genes.

Introduction

Fusidic acid is a steroid antibiotic that is used to treat skin infections caused by staphylococci in some countries [1]. The major target of fusidic acid is elongation factor G (EF-G), which is involved in protein synthesis [2–4]. Two major mechanisms of fusidic acid resistance have been reported. One mechanism is alteration of the drug target site, which is due to mutations in fusA (encoding EF-G) or fusE (encoding ribosome protein L6) [2, 5, 6]. The other mechanism is protection of the drug target site, which is mediated by the FusB-family proteins [7–10]. The FusB proteins bind to EF-G on the ribosome, thereby allowing the dissociation of stalled ribosome·EF-G·GDP complexes that form in the presence of fusidic acid [3, 4, 6, 9, 10]. As a result, the ribosome clearance mediated by the FusB-family proteins rescues the stalled translation [6, 9, 10].

The FusB-family proteins are encoded by the fusB, fusC, fusD or fusF gene and usually cause low levels of fusidic acid resistance [7, 8, 11]. The fusB gene has been found in Staphylococcus aureus and other staphylococcal species, either carried on a plasmid [12, 13] or on phage-related resistance islands (RIs) integrated into the chromosome [14–16]. The fusC gene has been found in the staphylococcal chromosome cassette (SCC), such as SCCfusC [17], SCC476 [18], SCCmec N1 [19] and pseudo SCCmec [20]. The fusD and fusF genes are found exclusively in the chromosome of Staphylococcus saprophyticus and Staphylococcus cohnii subsp. urealyticus, respectively, which explains the intrinsic fusidic acid resistance of both organisms [7, 11].

Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS), which constitute a major element of the commensal microflora of human skin, comprise a multitude of species including Staphylococcus capitis, S. cohnii, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Staphylococcus hominis, S. saprophyticus and Staphylococcus warneri [21–23]. CoNS have been identified as playing an important role as reservoirs of gene pools, which can facilitate pathogen infection. For example, S. epidermidis and S. haemolyticus may act as a source of the SCCmec, thereby allowing S. aureus to become methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), which is responsible for several difficult-to-treat infections [24, 25]. As another example, horizontal transfer of the arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME) from S. epidermidis to MRSA USA300 may provide multiple fitness advantages [26].

The rate of resistance to fusidic acid in staphylococci varies in different countries. For S. aureus, fusidic acid resistance rates ranged from 1.4% to 52.5% in European countries [27], 7% in Canada and Australia [28] and <0.35% in the United States [28, 29]. In Asian countries, the fusidic acid-resistant S. aureus rates were relatively low (<10%), except in Kuwait, Pakistan and South Korea [30]. Higher fusidic acid resistance rates in CoNS than in S. aureus has been reported in some European countries (12.5% to 50.0%), the United States (7.2%), Canada (20.0%) and Australia (10.8%) [27, 28]. In Taiwan, the proportion of fusidic acid-resistant S. aureus at the National Taiwan University Hospital ranged from 3 to 6% [13], which is much lower than the resistance rates in S. epidermidis (39 to 46%) [15] or in CoNS (48.9%, data from National Taiwan University). However, it has been reported that the novel SCCfusC has replaced point-mutated fusA as the dominant in fusidic acid resistance mechanism in ST239/SCCmecIII MRSA in Taiwan after 2008 [13, 17]. Sequence homology analysis suggests that part of SCCfusC may originate in S. epidermidis [17]. In contrast, the major resistance determinant of clinical fusidic acid-resistant S. epidermidis in Taiwan was fusB carried by RIs [15, 16].

The topical use of fusidic acid on skin would select for the fusB-family genes in those individuals colonized by S. aureus and CoNS. Analysis of fusidic acid resistance in nasal carriage S. aureus isolated from general medical practice patients with non-infectious conditions in Europe revealed that acquired fusB and fusC were dominant resistant mechanisms [31]. As for CoNS, which are the possible reservoirs for horizontal gene transfer, there have been no reports regarding the fusidic acid resistance determinants or mechanisms in colonizing strains that have not caused diseases in their hosts. Therefore, we examined the fusidic acid resistance genes in colonized staphylococci and compared their genetic environment to those in clinical isolates, and we evaluated the possibility of genetic exchanges between commensal and pathogenic staphylococci.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

A total of 59 healthy, 16- to 18-year-old volunteers with no recent record of hospitalization or diseases from a senior high school in Taipei, Taiwan were enrolled in this study. The isolates were obtained during school hours in August 2010 by drawing the fingers of the right hand (index finger, middle finger and ring finger) with gentle pressure across the surface of mannitol salt agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI). After incubation at 37°C for 24 h, a total of 853 isolates were collected. This study was approved by the National Taiwan University Hospital Institutional Review Board (201307006RIN), waiving the requirement for written informed consent.

Identification and genotyping of fusidic acid-resistant staphylococci

The isolates were first screened by subculturing on Mueller-Hinton II agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, MI) containing 1 μg/ml fusidic acid. The susceptibility of the growing isolates were tested by the agar dilution method, and the minimal inhibition concentration (MIC) values ≧ 2 μg/ml would be interpreted as fusidic acid-resistant. Species identification was performed by Gram staining, the catalase test and the molecular methods described below. The isolates with no characteristics of staphylococci were excluded from this study. Bacterial DNA was purified with a DNA isolation kit (Puregene, Gentra Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following three PCR-based methods were carried out to identify the isolates at the species or subspecies level: (i) dnaJ PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis [32]; (ii) S. epidermidis-specific PCR [33]; (iii) 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The dnaJ PCR-RFLP analysis allows for the differentiation between subspecies pairs of S. capitis, S. cohnii and S. hominis [32].

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as previously described [13]. In brief, The DNA was digested with SmaI (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA) and then was separated using a CHEF-DRIII apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). PFGE was carried out at 200 V and 12°C for 20 h with the pulse times ranging from 5 to 60 s.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by the agar dilution method according to CLSI 2014 guidelines [34]. Bacterial inocula were prepared by direct colony suspension to a turbidity of 0.5 McFarland standards. A bacterial density of 104 CFU/spot was inoculated onto Mueller-Hinton II agar (BBL) with various concentrations of fusidic acid (0.03 to 256 μg/ml) using a Steers replicator, and the plates were incubated at 35°C for 16 to 20 h. S. aureus ATCC 29213 was used as the reference strain. The breakpoint used to indicate fusidic acid resistance was ≧ 2 μg/ml [11, 13, 15, 35], although the breakpoint is defined as > 1 μg/ml by EUCAST [36].

Detection of acquired fusidic acid resistance determinants and their genetic environments

The presence of the acquired fusidic acid resistance determinants fusB, fusC, fusD and fusF was detected by PCR as previously described [11, 13]. The fusB element on plasmids or located in RIs (integrated into groEL, rpsR or smpB) was determined by PCR using the primers listed in Table 1, and the positions of the primers were indicated in S1 Fig. The presence of SCCfusC was detected by PCR using the primer sets listed in Table 1 and the primer sets (B to U) covering almost the entire region as previously described [17]. The schematic diagram of SCCfusC mapping was shown in S2A Fig.

Table 1. Primers used in this study a .

| Primer set | Primer name | Sequence (5'-3') | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection of RI integrated into groEL in S. epidermidis | |||

| a | S. epi groEL 1213-1232F | CTKGAAGAAGGTATYGTTGC | [15] |

| int (I) 109-128F | CGTAAATCAGACGCTAAACA | [15] | |

| b | int (I) 109-128F | CGTAAATCAGACGCTAAACA | [15] |

| int (I) 1139-1122R | CTAAACTTGTGGGAAGCG | [15] | |

| c | fusB531-559F | CGGATGGTCAATATGTAAAAAAAGGTGAC | [13] |

| 185 LA 3R | CTCACAGAGGTTCTATAATGTTGG | [15] | |

| Detection of RI integrated into smpB in S. epidermidis | |||

| d | S.epi ssra407-429 (F) | TCAAGCACTTAAAGAAAAAGCGG | [16] |

| int (III) 175–194F | GACGAGTTAGAGGGTATTGG | [16] | |

| e | int (III) 175–194F | GACGAGTTAGAGGGTATTGG | [16] |

| int (III) 1087–1068R | TACTAGGGTACAAATGACCG | [16] | |

| f | fusB531-559F | CGGATGGTCAATATGTAAAAAAAGGTGAC | [13] |

| S.epi sodium transporter 1146–1168F | TCTCACTATGGATTTAACTTCCG | [16] | |

| Detection of RI integrated into rpsR in S. epidermidis | |||

| g | S epi rpsR 6-24F | AGGTGGACCAAGAAGAGGC | [15] |

| int(II) 541-565F | GCTAAACGTAATAACTATTTAGAAG | [15] | |

| h | int(II) 541-565F | GCTAAACGTAATAACTATTTAGAAG | [15] |

| int 1061-1042R | GTGTGACGTAATGTGTGCGT | [15] | |

| i | fusB531-559F | CGGATGGTCAATATGTAAAAAAAGGTGAC | [13] |

| fusB LA-2R | AATACTCCTGGATGGCGT | [15] | |

| Detection of RI integrated into groEL in S. capatis subsp. urealyticus (primer sets a and b also used) | |||

| j | fusB531-559F | CGGATGGTCAATATGTAAAAAAAGGTGAC | [13] |

| cap-CWA-R | CYTCMTCTTCGTCAGGAT | This study | |

| Sequencing of ScRIfusB (primer sets a, b, and j also used) | |||

| k | 7778 PstI up2F | CGCTGATACCTTTGTTGAAC | This study |

| fusBR | ACAATGAATGCTATCTCGACA | [13] | |

| j | Sepi 2793up2F | AAAGTGCTGTATGGCGTG | This study |

| ri17 284-265R | TCCATAGCATTTAATCCGTG | This study | |

| Detection of the fusB-carrying plasmid pUB101 and its relatives | |||

| m | IS257 518-499R | ATATGACGGTGATCTTGCTC | [13] |

| fusB 283-254R | AGGTAGTTCAAAAG | [13] | |

| n | IS257 33-52F | GGATGTTATCACTGT | [13] |

| fusB 530-558F | CGGATGGTCAATATGTAAAAAAAGGTGAC | [13] | |

| Detection and sequencing SCCfusC | |||

| o | orfX-uF | ACTTCGTCTTCGTCATTGG | This study |

| hsdR_593R | CTCCAATAAAACATTTGTCCC | [17] | |

| p (inverse PCR) | SAS0044dn382R | GGATTCAGAATGGTTTCC | [17] |

| SAS0046_226R | AACCTTCGGTATCATCCG | This study | |

| Sequencing of pseudo SCC and its flanking region | |||

| q (LA PCR) | fusC 162-183F | GGACTTTATTACATCGATTGAC | [13] |

| fusC 572-550R | CTGTCATAACAAATGTAATCTCC | [13] | |

| r (inverse PCR) | 21429-helicase-R | CGGCTTGAAACTGTAACC | This study |

| 21429A-copBR | GTATGACAAGTATCGCAGCG | This study | |

| s (inverse PCR) | copB-F | ATACGAGTTGGTGAAACCTTAC | This study |

| TFGfusC 7914F | TAACGGTCATTTCACTCG | This study | |

| t | MFS-transF | GAACAGATTTAGCAAAGTCAC | This study |

| speG-7F | CTAAGAGCATTAGAGTATAGTG | [17] | |

| u (inverse PCR) | up speG-R | GATTTGTATGAATGGCACTC | This study |

| speG 408R | TGTTTTAAATCCTTGTGACTCG | [17] | |

| v | speGR408R | TGTTTTAAATCCTTGTGACTCG | [17] |

| hominis-afSCC-R | TTCTTCTGAAACTATCTGCTGG | This study | |

Sequencing of the fus elements ScRIfusB, SCCfusC and pseudo SCC

The sequence of ScRIfusB was determined by five PCRs covering the entire region using the primers listed in Table 1 and illustrated in S1D Fig. The sequence of SCCfusC was determined by the 21 primer sets used for PCR mapping, and the extreme right region was determined by inverse PCR as shown in S2A Fig. To determine the sequence of pseudo SCC, general PCR, the LA PCR in vitro cloning kit (Takara Shuzo Co.) or inverse PCR were used as shown in Table 1 and S2B Fig. In brief, PCR primers specific for the known sequence were used, and the PCR product was subsequently sequenced. To obtain the full sequence of the corresponding mobile elements, the fragments were used as probes for Southern blot hybridization to determine a suitable restriction enzyme to use for further cloning. The sequence was collected by aligning and combining the amplification fragments obtained by LA PCR or inverse PCR.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST)

The MLST was analyzed in 14 fusB-positive S. epidermidis strains and 5 fusC-positive S. hominis subsp. hominis strains according to the methods described previously [37, 38]. The new sequence types were deposited in the S. epidermidis and S. hominis MLST databases. The eBURST method was used to infer the evolutionary relatedness of STs (http://www.mlst.net).

Detection of virulence genes associated with invasive infection in S. epidermidis isolates

We detected the icaAB of the ica locus, IS256 and mecA to discriminate between virulent and non-virulent isolates as previously described [16].

Nucleotide sequences

The nucleotide sequences of SCCfusC of S. hominis subsp. hominis TFGsh1, ScRIfusB of S. capitis subsp. urealyticus TFGsc1 and pseudo SCC of S. hominis subsp. hominis TFGsh5-1 have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers AB930126 to AB930128.

Results

Species distribution of fusidic acid-resistant staphylococci from hand skin flora

Among the 853 isolates collected from 59 volunteers, a total of 70 isolates recovered from 22 individuals (22/59 = 37.3%) were found to be fusidic acid-resistant staphylococci (MIC values ≧ 2 μg/ml). The isolates obtained from the same person exhibiting identical PFGE patterns were considered to be the same strain. Therefore, 34 fusidic-acid resistant CoNS strains were obtained, and no fusidic acid-resistant S. aureus was found. Among the 34 fusidic-acid resistant CoNS strains, the most common species was S. epidermidis (14 strains in 38 isolates), followed by S. cohnii subsp. urealyticus (5 strains in 14 isolates), S. hominis subsp. hominis (5 strains in 8 isolates), S. saprophyticus (4 strains/isolates), S. capitis subsp. urealyticus (3 strains/isolates), S. warneri (2 strains/isolates) and S. haemolyticus (1 strains/isolate) (Table 2). Three S. capitis subsp. urealyticus strains isolated from three different individuals were phylogenetically related because the DNA restriction patterns produced by PFGE had less than two-band differences. Among the 22 individuals who harbored fusidic acid-resistant staphylococci, five were colonized by two species, and one was colonized by four species. There were three individuals who were colonized with multiple strains of S. epidermidis, and the strains isolated from the same person displayed very limited differences in the PFGE patterns.

Table 2. Fusidic acid-resistant CoNS found in 22 individuals.

| Individual code | Species | No. of strains (isolates) | Fusidic acid determinant | Location of fus element |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S. epidermidis | 1 (1) | fusB | RI integrated into smpB |

| S. hominis subsp. hominis | 1 (1) | fusC | SCCfusC | |

| 2 | S. cohnii subsp. urealyticus | 1 (1) | fusF | ND a |

| S. saprophyticus | 1 (1) | fusD | ND a | |

| 3 | S. epidermidis | 1 (2) | fusB | RI integrated into groEL |

| 4 | S. warneri | 1 (1) | fusB | Unknown |

| 5 | S. capitis subsp. urealyticus | 1 (1) | fusB | RI integrated into groEL |

| S. cohnii subsp. urealyticus | 1 (10) | fusF | ND a | |

| S. epidermidis | 1 (1) | fusB | RI integrated into groEL | |

| S. warneri | 1 (1) | fusC | Unknown | |

| 6 | S. cohnii subsp. urealyticus | 1 (1) | fusF | ND a |

| S. epidermidis | 3 (4) | fusB | RI integrated into smpB | |

| 7 | S. capitis subsp. urealyticus | 1 (1) | fusB | RI integrated into groEL |

| S. epidermidis | 2 (5) | fusB | RI integrated into smpB | |

| 8 | S. saprophyticus | 1 (1) | fusD | ND a |

| 9 | S. saprophyticus | 1 (1) | fusD | ND a |

| 10 | S. epidermidis | 1 (1) | fusB | Unknown |

| 11 | S. cohnii subsp. urealyticus | 1 (1) | fusF | ND a |

| 12 | S. epidermidis | 2 (8) | fusB | RI integrated into smpB |

| 13 | S. hominis subsp. hominis | 1 (1) | fusC | SCCfusC |

| 14 | S. cohnii subsp. urealyticus | 1 (1) | fusF | ND a |

| 15 | S. hominis subsp. hominis | 1 (2) | fusC | SCCfusC |

| 16 | S. epidermidis | 1 (1) | fusB | Unknown |

| 17 | S. capitis subsp. urealyticus | 1 (1) | fusB | RI integrated into groEL |

| 18 | S. epidermidis | 1 (14) | fusB | RI integrated into smpB |

| 19 | S. epidermidis | 1 (1) | fusB | RI integrated into smpB |

| S. hominis subsp. hominis | 1(1) | fusC | Unknown | |

| 20 | S. hominis subsp. hominis | 1 (3) | fusC | Pseudo SCC |

| 21 | S. haemolyticus | 1 (1) | fusC | Unknown |

| 22 | S. saprophyticus | 1 (1) | fusD | ND a |

Fusidic acid resistance determinants

PCR detection of fusB-type genes (fusB, fusC, fusD and fusF) was performed on the 34 fusidic acid-resistant staphylococci. As shown in Table 2, all S. epidermidis and S. capitis subsp. urealyticus isolates possessed fusB, whereas the S. hominis subsp. hominis and S. haemolyticus isolates carried the fusC gene. S. warneri harbored fusB or fusC. The fusD and fusF genes were found exclusively in S. saprophyticus and S. cohnii subsp. urealyticus strains, respectively.

Genetic environments of fusB

The locations of fusB, which appears to be associated with mobile genetic elements, were examined by PCR based on the known sequences of RIs or plasmids (Table 1). Of the 14 S. epidermidis strains, 12 strains carried fusB by RIs either integrated into groEL (n = 2) or smpB (n = 10) (Table 2). The location of fusB in the remaining two S. epidermidis strains and one S. warneri strain remains unknown.

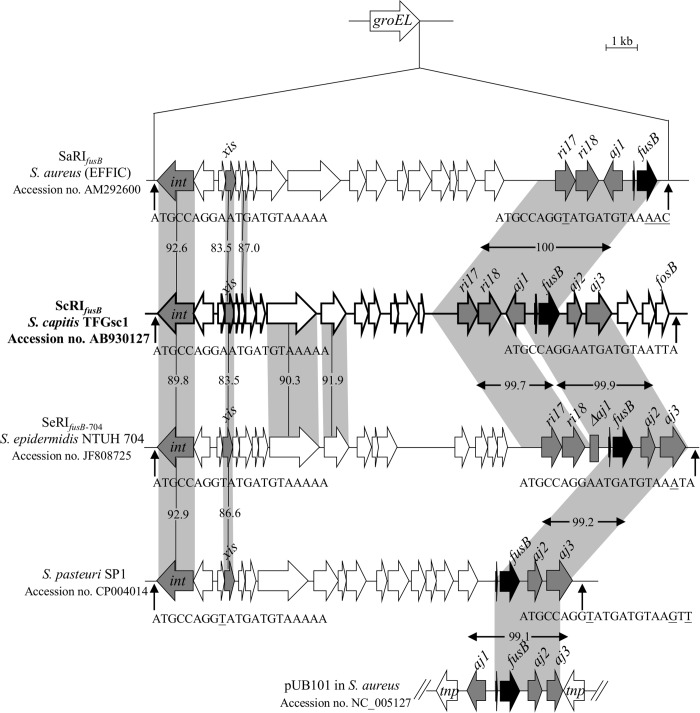

The three S. capitis subsp. urealyticus strains were found to acquire fusB by a RI integration into groEL using PCR primer sets designed in this study (Table 1). Because there is no report on the structure of the fusB element in S. capitis, strain TFGsc1 (isolated from individual No. 5) was subjected to sequencing to confirm the PCR results. Sequence analysis revealed a 16,916-bp RI integrated into groEL, which was referred to as ScRIfusB, where “Sc” signifies “S. capitis”. ScRIfusB had 24 putative open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig 1 and S1 Table). It carried the ri17-ri18-aj1-fusB-aj2-aj3 locus, which is always fragmented in other reported mobile genetic elements, such as SaRIfusB, SeRIfusB-704, RI in S. pasteuri SP1 and pUB101 (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Structure of ScRIfusB in S. capitis subsp. urealyticus TFGsc1.

ScRIfusB was compared to SaRIfusB, SeRIfusB-704, the RI in the S. pasteuri genome (the above RIs are inserted into groEL) and the plasmid pUB101. The ORFs are shown as arrows, and the genes of interest are indicated as grey or black arrows. The homologous regions are shaded, and the numbers in the shadow show the percent homology between the corresponding sequences in comparison to ScRIfusB. The predicted att sites are indicated by vertical arrows. Th divergent nucleotides in the 21-bp att sequences are underlined.

One person (individual No. 5) was colonized by S. capitis subsp. urealyticus and S. epidermidis. Both of the species carried fusB-related RIs with the same integration sites in groEL. To know if horizontal gene transfer has occurred between the two species, the structures of the fusB element in S. epidermidis was further analyzed using the resolved sequence of ScRIfusB (16,916-bp RI) from the S. capitis subsp. urealyticus. However, PCR mapping revealed that the fusB surrounding region in S. epidermidis was different from ScRIfusB, indicating the two species did not share the same mobile genetic structures.

Genotypic analysis of fusidic acid-resistant S. epidermidis

To further understand the genetic relatedness of the 14 fusB-positive S. epidermidis strains, we determined the sequence types by MLST and the presence of genes associated with invasive infections (icaAB, IS256 and mecA) [16]. As shown in Table 3, 7 sequence types were identified and were clustered by eBURST algorithm into three clonal complexes (CCs): CC2 (n = 7), CC365 (n = 4) and a CC with no predicted founder (n = 3). The prevalence of icaAB, IS256 and mecA was low for the 14 S. epidermidis strains. The strains isolated from individual No. 6, 10 and 16 were ST57, but exhibited differences in the virulence gene patterns and the mechanism by which the fusB elements were acquired. The strains isolated from individuals No. 1 and 5 were ST438 and shared identical virulence gene patterns, although they acquired fusB-carrying RIs integrated into different sites. The strain isolated from individual No. 18 was ST-NT2, which is a single locus variant of ST-NT3 found in a strain isolated from individual No. 19. The S. epidermidis strains isolated from the same individual (No. 6, 7 and 12) shared identical genetic patterns within the same person.

Table 3. Genetic characteristics of S. epidermidis carrying fusB elements at different integration sites.

| RI integration site | Individual code | Clonal complex | MLST profile | Genes associated with invasive infections | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| icaAB | IS256 | mecA | ||||

| smpB | 1 | 365 | 438 (3-25-5-5-11-4-11) | - | - | - |

| 6 a | 2 | 57 (1-1-1-1-2-1-1) | - | - | + | |

| 7 a | 2 | 194 (7-1-2-2-4-1-13) | + | - | - | |

| 12 a | NPF c | NT1b (3-16-9-5-3-x1 b -5) | - | - | - | |

| 18 | 365 | NT2b (3-25-5-5-11-x2 b -20) | - | - | - | |

| 19 | 365 | NT3b (3-25-5-5-11-4-20) | - | - | - | |

| groEL | 3 | NPF c | 208 (3-3-13-5-7-4-4) | - | - | - |

| 5 | 365 | 438 (3-25-5-5-11-4-11) | - | - | - | |

| Unknown | 10 | 2 | 57 (1-1-1-1-2-1-1) | - | - | - |

| 16 | 2 | 57 (1-1-1-1-2-1-1) | - | + | + | |

a The multiple strains obtained from the same individual (No. 6, No. 7 or No. 12) display identical patterns in each person.

b Novel allele or ST found in this study. NT3 represents novel combination of known alleles, while NT1 and NT2 represent combinations containing novel allele sequences of tpi. The novel allele sequences and ST have been submitted to the S. epidermidis MLST database (http://sepidermidis.mlst.net). The two novel allele sequences of tpi can be found in S1 Text.

c NPF: the ST-NT1 and ST208 were clustered in a clonal complex with no predicted founder.

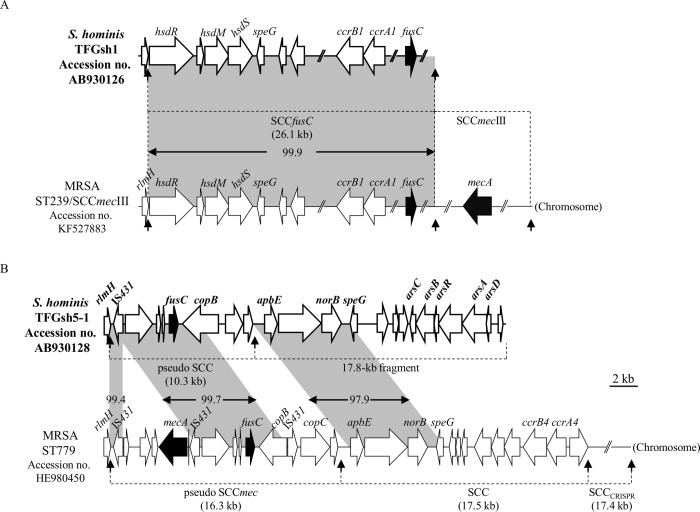

Genetic environments of fusC

A total of 7 fusC-positive strains, including 5 S. hominis subsp. hominis, 1 S. haemolyticus, and 1 S. warneri, were found (Table 2). As fusC was mostly found within the SCC structure in staphylococci [17–20], we first detected the ccr genes (encoding cassette chromosome recombinases) by PCR. Three S. hominis subsp. hominis strains and 1 S. warneri strain were positive for ccrA1B1. Further PCR mapping revealed that all three ccrA1B1-positive S. hominis strains carried SCCfusC. Because the SCCfusC has only been reported in ST239/SCCmecIII MRSA [17], we subsequently determined the sequence of SCCfusC in the S. hominis subsp. hominis strain TFGsh1 to confirm the PCR mapping results. Nucleotide sequence analysis indicated 99.9% similarity (16 bp mismatch) compared to SCCfusC in ST239/SCCmecIII MRSA strain NTUH-4729 (Fig 2A and S2 Table).

Fig 2. Genetic organization of fusC-related elements in S. hominis subsp. hominis.

(A) Schematic maps of SCCfusC in strain TFGsh1 and (B) the composite SCC structure in strain TFGsh5-1 are shown. The ORFs are shown as arrows, and the drug resistance genes fusC and mecA are shown as black arrows. The homologous regions are shaded, and the numbers in the shadow show the percent homology. The att sequence is indicated by vertical arrows.

To determine the location and structure of the fusC element in the other two S. hominis subsp. hominis strains which do not carry known ccrAB or ccrC, the flanking region of fusC in one strain (TFGsh5-1) was cloned and sequencing. The result revealed that fusC in TFGsh5-1was present in a pseudo SCC structure and was inserted at the 3′-end of rlmH (Fig 2B and S3 Table). The pseudo SCC is 10,252-bp in length and consists of 8 ORFs. The IS431-dinA-orf-orf-fusC-copB locus (partial copB because 1 to 575 bp was truncated in ST779 MRSA) showed 99.7% nucleotide sequence similarity to the pseudo SCCmec in ST779 MRSA. A 17.8-kb fragment was found immediately downstream of the pseudo SCC. The region from the second att site to speG showed 97.9% nucleotide sequence similarity to the SCC in ST779 MRSA.

For another fusC-positive, ccr-negative S. hominis subsp. hominis strain in individual No. 19, the dinA-orf-orf-fusC-copB locus was detected, but the chromosome/plasmid location remains unknown because no amplification product could be generated between rlmH and the fusC flanking region.

For fusC-positive S. warneri (n = 1) and S. haemolyticus (n = 1), the genetic environments of fusC were unknown.

Genotyping of fusidic acid-resistant S. hominis subsp. hominis

MLST was carried out to understand the phylogenetic relationships between the five fusidic acid-resistant S. hominis subsp. hominis strains. As shown in Table 4, two SCCfusC-carrying strains isolated from individuals No. 13 and 15 shared the same sequence type. The other strains were of diverse genetic backgrounds.

Table 4. Genotypes of fusC-positive S. hominis subsp. hominis.

| Structure of fusC element | Individual code | MLST profile |

|---|---|---|

| SCCfusC | 1 | 41 a (11 a -2-13-1-6-3) |

| 13 | 42 a (2 a -5-13-4-6-3) | |

| 15 | 42 a (2 a -5-13-4-6-3) | |

| Pseudo SCC | 20 | 44 a (17 a -5-13-4-7-3) |

| Unknown | 19 | 43 a (1 a -3-3-12 a -6-6 a ) |

a Novel allele or ST found in this study.

Discussion

This is the first report to study fusidic acid resistance in staphylococci among the skin flora of healthy volunteers. In this study, we did not find fusidic acid-resistant S. aureus among the skin flora, although we have isolated fusidic acid-susceptible S. aureus (data not shown). The result is in accord with the low resistance rate to fusidic acid in clinical isolates of S. aureus in Taiwan (0 to 6%) [15, 30]. The overall resistance rate of fusidic acid in CoNS from skin flora in the community was 37.3%, which was lower than those isolated from hospitalized patients in Taiwan (48.9%, introduction) but is still higher than CoNS isolated from hospitals in the United States (7.2%), Canada (20.0%), Australia (10.8%) or some European countries (Greece, Israel, Italy, Poland, Spain and Turkey, 12.5% to 32.0%) [27, 28].

In the present study, the breakpoint of 2 μg/ml was used to interpret fusidic acid resistance as we used before [11,13,15], instead of ≥1 μg/ml recommended by the EUCAST [36]. Therefore, the overall fusidic acid resistance rate would probably slightly increase if the EUCAST breakpoint is applied.

The fusidic acid resistance among 34 resistant strains was mostly mediated by fusB and fusC. The fusB genes in the present study were mainly chromosomally encoded within resistance islands (RIs) in specific chromosomal locations, while fusC was carried by different SCC elements, including the previously described SCCfusC and a new pseudo SCC element. The fusB-related RI elements have been reported in S. aureus, S. pasteuri, and S. epidermidis clinical isolates [15,16]. In the present study, we first found that S. capitis subsp. urealyticus carried fusB-RI. Both RIs and pathogenicity islands (PIs) are phage-related chromosomal islands that produce phage-like infectious particles by hijacking the capsids of phages [39]. To date, several PI-related accessory virulence genes have been described, such as tst (encoding toxic shock syndrome toxin) and seb (encoding staphylococcal enterotoxin B). Orthologues of these genes have been reported in different PIs, but most of them are still restricted in the S. aureus genome [39]. Unlike the PI-related virulence genes, the fusB was found not only in the RIs of four different Staphylococcus species but also on a S. aureus-derived plasmid, pUB101 [12, 14–16] (Fig 1). Comparison of the immediate flanking regions of fusB among the different species revealed high sequence similarities (> 99.1%), even though some deletions were observed (Fig 1). The low G + C content (26.6%) of the ScRIfusB ri17-ri18-aj1-fusB-aj2-aj3 locus compared to the S. capitis genome (32.76%) [40] implies that the element may originate in other bacterial species and then disseminate into staphylococci by RIs or plasmids.

We have previously reported a novel emerging SCCfusC in fusidic acid-resistant ST239/SCCmecIII MRSA in Taiwan [17]. In the present study, we unexpectedly found three of five S. hominis strains carried the SCCfusC, and the sequence of SCCfusC in strain TFGsh1 was nearly identical to that in ST239/SCCmecIII MRSA. To date only S. hominis and no other CoNS are known to carry SCCfusC. Thus, the commensal S. hominis may act as an important reservoir for horizontal gene transfer for the dissemination of fusC to ST239/SCCmecIII MRSA in Taiwan, although the origin of SCCfusC remains to be explored.

The other fusC-related structure found in the present study was a pseudo SCC element. The fusC flanking region in the pseudo SCC of S. hominis displayed a high sequence similarity to flanking region of the pseudo SCCmec in ST779 MRSA (Fig 2B) except the lack of a 4.7-kb fragment harboring mecA, which was flanked by IS431 direct repeats. Thus, the S. hominis pseudo SCC may result from replacement of the mecA element by fusC via homologous recombination between the two IS431 elements, which belongs to the IS6 family (e.g., IS431 and IS1216V) [41]. Another IS431 located in right side of the MRSA ST779 pseudo SCCmec, which gave rise to 5′-end truncation of copB, may also lead to differences between pseudo SCC and pseudo SCCmec. In S. hominis strain TFGsh5-1, a 17.8-kb fragment was demarcated from the pseudo SCC by an att sequence (Fig 2B). The 17.8-kb fragment carried virulence-related genes, speG and arsCBRAD, which are usually components of mobile genetic elements but are not present in the core chromosome of S. hominis [26, 42]. Hence, this 17.8-kb fragment behaved just like an SCC, although it did not contain the ccr genes. The mosaic structures of pseudo SCC implied that multiple recombination events have occurred after acquisition of the foreign genetic element into S. hominis or S. aureus.

Multiple S. epidermidis strains isolated from the same person exhibited identical sequence types as well as virulence gene patterns associated with invasive infections (Table 3); only limited differences were observed in the PFGE profiles. They also acquired fusB elements that were integrated into the same site (Table 2). This suggested that these strains may have acquired fusB-carrying RIs once and then undergone evolutionary changes to produce slightly different PFGE patterns in the same host.

Previous studies have shown that the CC2 was the most common S. epidermidis in both hospital (87.3% to 100%) and community (58%) [43–46]. However, prevalence of icaAB, IS256 and mecA in CC2 S. epidermidis isolated from community environment was lower than that in clinical isolates even they shared similar genetic background [44,46]. For the 14 fusB-positive S. epidermidis strains which were CC2 or other minor clonal lineages, the overall prevalence of icaAB, IS256 and mecA was low (Table 3). It implies that the fusB-positive S. epidermidis in skin flora is not originated in hospital.

In conclusion, fusidic acid resistance in commensal staphylococci was found to be mainly mediated by the fusB-family genes. At least four types of mobile genetic elements carrying fusB or fusC were responsible for the fusidic acid resistance in CoNS, suggesting multiple events of horizontal gene transfer have occurred among various species or lineages in community. The structures of the acquired resistance elements were similar to the structures in clinical isolates, implying that commensals may act as reservoir for the pathogens. Furthermore, the high similarities of SCCfusC provide evidence for possible horizontal transfer between commensal S. hominis and ST239/SCCmecIII MRSA.

Supporting Information

Schematic maps of RI in S. epidermidis integrated into groEL (A), smpB (B) and rpsR (C), RI in S. capitis subsp. urealyticus integrated into (D) groEL and plasmid pUB101 (E) are shown. The arrows below the structures indicate PCR primers, which are listed in Table 1.

(PDF)

Schematic maps for SCCfusC (A) and pseudo SCC with its flanking region (B) are shown. The arrows below the structures indicate PCR primers, which are listed in Table 1.

(PDF)

(XLS)

(XLS)

(XLS)

(TXT)

Data Availability

The nucleotide sequences (accession numbers AB930126 to AB930128) have been deposited in the GenBank database and will be available after acceptance.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC 100-2320-B-002-014-MY3) and from Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 103-2320-B-002-056-MY3).

References

- 1. Dobie D, Gray J. Fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus . Arch Dis Child. 2004;89: 74–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Besier S, Ludwig A, Brade V, Wichelhaus TA. Molecular analysis of fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus . Mol Microbiol. 2003;47: 463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borg A, Holm M, Shiroyama I, Hauryliuk V, Pavlov M, Sanyal S, et al. Fusidic acid targets elongation factor G in several stages of translocation on the bacterial ribosome. J Biol Chem. 2015; 290: 3440–3454. 10.1074/jbc.M114.611608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilson DN. Ribosome-targeting antibiotics and mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12: 35–48. 10.1038/nrmicro3155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Norstrom T, Lannergard J, Hughes D. Genetic and phenotypic identification of fusidic acid-resistant mutants with the small-colony-variant phenotype in Staphylococcus aureus . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51: 4438–4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koripella RK, Chen Y, Peisker K, Koh CS, Selmer M, Sanyal S. Mechanism of elongation factor-G-mediated fusidic acid resistance and fitness compensation in Staphylococcus aureus . J Biol Chem. 2012;287: 30257–30267. 10.1074/jbc.M112.378521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Neill AJ, McLaws F, Kahlmeter G, Henriksen AS, Chopra I. Genetic basis of resistance to fusidic acid in staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51: 1737–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Neill AJ, Chopra I. Molecular basis of fusB-mediated resistance to fusidic acid in Staphylococcus aureus . Mol Microbiol. 2006;59: 664–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guo X, Peisker K, Backbro K, Chen Y, Koripella RK, Mandava CS, et al. Structure and function of FusB: an elongation factor G-binding fusidic acid resistance protein active in ribosomal translocation and recycling. Open Biol. 2012;2: 120016 10.1098/rsob.120016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cox G, Thompson GS, Jenkins HT, Peske F, Savelsbergh A, Rodnina MV, et al. Ribosome clearance by FusB-type proteins mediates resistance to the antibiotic fusidic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109: 2102–2107. 10.1073/pnas.1117275109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen HJ, Hung WC, Lin YT, Tsai JC, Chiu HC, Hsueh PR, et al. A novel fusidic acid resistance determinant, fusF, in Staphylococcus cohnii . J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70: 416–419. 10.1093/jac/dku408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Brien FG, Price C, Grubb WB, Gustafson JE. Genetic characterization of the fusidic acid and cadmium resistance determinants of Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pUB101. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;50: 313–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen HJ, Hung WC, Tseng SP, Tsai JC, Hsueh PR, Teng LJ. Fusidic acid resistance determinants in Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54: 4985–4991. 10.1128/AAC.00523-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Neill AJ, Larsen AR, Skov R, Henriksen AS, Chopra I. Characterization of the epidemic European fusidic acid-resistant impetigo clone of Staphylococcus aureus . J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45: 1505–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen HJ, Tsai JC, Hung WC, Tseng SP, Hsueh PR, Teng LJ. Identification of fusB-mediated fusidic acid resistance islands in Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55: 5842–5849. 10.1128/AAC.00592-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen HJ, Chang YC, Tsai JC, Hung WC, Lin YT, You SJ, et al. New Structure of Phage-related Islands Carrying fusB and a Virulence Gene in Fusidic Acid-Resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57: 5737–5739. 10.1128/AAC.01433-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lin YT, Tsai JC, Chen HJ, Hung WC, Hsueh PR, Teng LJ. A Novel Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosomal Element, SCCfusC, Carrying fusC and speG in Fusidic Acid-Resistant Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58: 1224–1227. 10.1128/AAC.01772-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holden MT, Feil EJ, Lindsay JA, Peacock SJ, Day NP, Enright MC, et al. Complete genomes of two clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains: evidence for the rapid evolution of virulence and drug resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101: 9786–9791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ender M, Berger-Bachi B, McCallum N. Variability in SCCmec N1 spreading among injection drug users in Zurich, Switzerland. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7: 62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kinnevey PM, Shore AC, Brennan GI, Sullivan DJ, Ehricht R, Monecke S, et al. Emergence of sequence type 779 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus harboring a novel pseudo staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec)-SCC-SCCCRISPR composite element in Irish hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57: 524–531. 10.1128/AAC.01689-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huebner J, Goldmann DA. Coagulase-negative staphylococci: role as pathogens. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50: 223–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Piette A, Verschraegen G. Role of coagulase-negative staphylococci in human disease. Vet Microbiol. 2009;134: 45–54. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Becker K, Heilmann C, Peters G. Coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27: 870–926. 10.1128/CMR.00109-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berglund C, Soderquist B. The origin of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate at a neonatal ward in Sweden-possible horizontal transfer of a staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec between methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus haemolyticus and Staphylococcus aureus . Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14: 1048–1056. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barbier F, Ruppe E, Hernandez D, Lebeaux D, Francois P, Felix B, et al. Methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci in the community: high homology of SCCmec IVa between Staphylococcus epidermidis and major clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus . J Infect Dis. 2010;202: 270–281. 10.1086/653483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Planet PJ, Larussa SJ, Dana A, Smith H, Xu A, Ryan C, et al. Emergence of the epidemic methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300 coincides with horizontal transfer of the arginine catabolic mobile element and speG-mediated adaptations for survival on skin. MBio. 2013;4: e00889–13. 10.1128/mBio.00889-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Castanheira M, Watters AA, Mendes RE, Farrell DJ, and Jones RN. Occurrence and molecular characterization of fusidic acid resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus spp. from European countries (2008). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65: 1353–1358. 10.1093/jac/dkq094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Castanheira M, Watters AA, Bell JM, Turnidge JD, and Jones RN. Fusidic acid resistance rates and prevalence of resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus spp. isolated in North America and Australia, 2007–2008. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54: 3614–3617. 10.1128/AAC.01390-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jones RN, Mendes RE, Sader HS, and Castanheira M. In vitro antimicrobial findings for fusidic acid tested against contemporary (2008–2009) gram-positive organisms collected in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52 Suppl 7: S477–486. 10.1093/cid/cir163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang JL, Tang HJ, Hsieh PH, Chiu FY, Chen YH, Chang MC, et al. Fusidic acid for the treatment of bone and joint infections caused by meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus . Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012:40:103–107. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. den Heijer CD, van Bijnen EM, Paget WJ, Stobberingh EE. Fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage strains in nine European countries. Future Microbiol. 2014;9: 737–745. 10.2217/fmb.14.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hauschild T, Stepanovic S. Identification of Staphylococcus spp. by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of dnaJ gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46: 3875–3879. 10.1128/JCM.00810-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu D, Swiatlo E, Austin FW, Lawrence ML. Use of a putative transcriptional regulator gene as target for specific identification of Staphylococcus epidermidis . Lett Appl Microbiol. 2006;43: 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute. 2014. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Twenty-fourth informational supplement M100-S24. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA, USA.

- 35. Coutant C, Olden D, Bell J, Turnidge JD. Disk diffusion interpretive criteria for fusidic acid susceptibility testing of staphylococci by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards method. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;25: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters, Version 5.0, 2015. http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/

- 37. Thomas JC, Vargas MR, Miragaia M, Peacock SJ, Archer GL, Enright MC. Improved multilocus sequence typing scheme for Staphylococcus epidermidis . J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:616–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang L, Thomas JC, Miragaia M, Bouchami O, Chaves F, d'Azevedo PA, et al. Multilocus sequence typing and further genetic characterization of the enigmatic pathogen, Staphylococcus hominis . PLoS One. 2013;8:e66496 10.1371/journal.pone.0066496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Novick RP, Christie GE, Penades JR. The phage-related chromosomal islands of Gram-positive bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8: 541–551. 10.1038/nrmicro2393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Qin N, Ding W, Yao J, Su K, Wu L, Li L. Genome sequence of Staphylococcus capitis QN1, which causes infective endocarditis. J Bacteriol. 2012;194: 4469–4470. 10.1128/JB.00827-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mahillon J, Chandler M. Insertion sequences. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62: 725–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yu D, Pi B, Chen Y, Wang Y, Ruan Z, Otto M, et al. Characterization of the staphylococcal cassette chromosome composite island of Staphylococcus haemolyticus SH32, a methicillin-resistant clinical isolate from China. PLoS One 2014;9: e87346 10.1371/journal.pone.0087346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mendes RE, Deshpande LM, Costello AJ, Farrell DJ. Molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus epidermidis clinical isolates from U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012;56: 4656–4661. 10.1128/AAC.00279-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rolo J, de Lencastre H, Miragaia M. Strategies of adaptation of Staphylococcus epidermidis to hospital and community: amplification and diversification of SCCmec . J Antimicrob Chemother 2012;67: 1333–1341. 10.1093/jac/dks068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Iorio NL, Caboclo RF, Azevedo MB, Barcellos AG, Neves FP, Domingues RM, et al. Characteristics related to antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation of widespread methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis ST2 and ST23 lineages in Rio de Janeiro hospitals, Brazil. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012;72: 32–40. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2011.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Du X, Zhu Y, Song Y, Li T, Luo T, Sun G, et al. Molecular analysis of Staphylococcus epidermidis strains isolated from community and hospital environments in China. PLoS One 2013;8: e62742 10.1371/journal.pone.0062742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Schematic maps of RI in S. epidermidis integrated into groEL (A), smpB (B) and rpsR (C), RI in S. capitis subsp. urealyticus integrated into (D) groEL and plasmid pUB101 (E) are shown. The arrows below the structures indicate PCR primers, which are listed in Table 1.

(PDF)

Schematic maps for SCCfusC (A) and pseudo SCC with its flanking region (B) are shown. The arrows below the structures indicate PCR primers, which are listed in Table 1.

(PDF)

(XLS)

(XLS)

(XLS)

(TXT)

Data Availability Statement

The nucleotide sequences (accession numbers AB930126 to AB930128) have been deposited in the GenBank database and will be available after acceptance.