Abstract

CA125, the most widely used ovarian cancer (OC) biomarker, was first identified approximately thirty-five years ago in an antibody screen against OC antigen. Two decades later, it was cloned and characterized to be a transmembrane mucin, MUC16. Since then several studies have investigated its expression, functional and mechanistic involvement in multiple cancer types. Antibody based therapeutic approaches primarily using antibodies against the tandem repeat domains of MUC16 (for example Oregovomab and Abagovomab) have been the modus operandi for MUC16 targeted therapy, but met with very limited success. In addition, efforts are also made to disrupt the functional co-operation of MUC16 and its interacting partners, for example use of a novel immunoadhesin HN125 to interfere MUC16 binding to mesothelin. Since the identification of CA125 to be MUC16, it is hypothesized to undergo proteolytic cleavage, a process that is considered to be critical in determining the kinetics of MUC16 shedding as well as generation of a cell associated carboxyl-terminal fragment with potential oncogenic functions. In addition to our experimental demonstration of MUC16 cleavage, recent studies have demonstrated the functional importance of carboxyl terminal fragments of MUC16 in multiple tumor types. Here, we provide how our understanding of the basic biological processes involving MUC16 influences our approach towards MUC16 targeted therapy.

Introduction

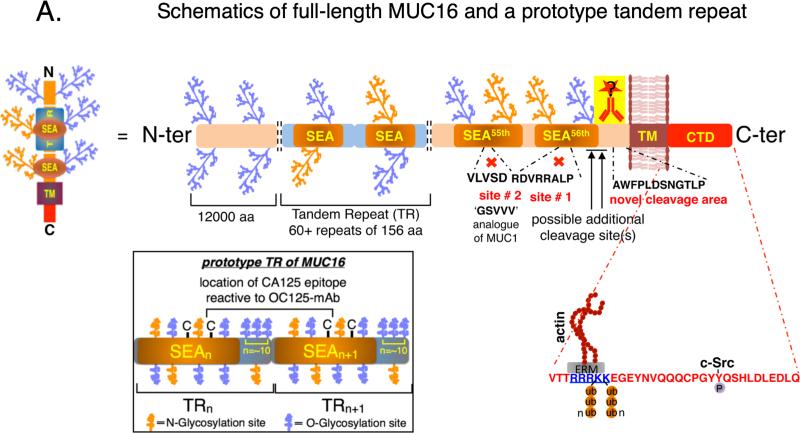

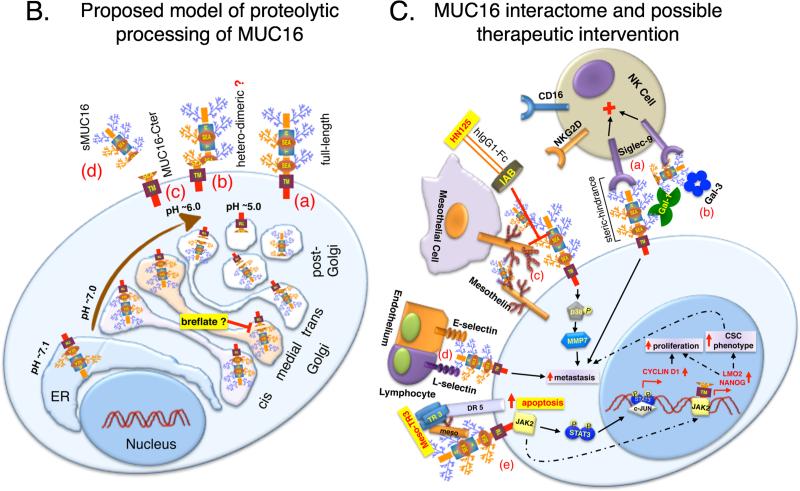

MUC16 is a type-I transmembrane mucin that was cloned and characterized independently by Lloyd and O'Brien in an effort towards biochemical characterization of CA125 (1-3). Based on the sequencing data, MUC16 is an extremely large glycoprotein (22,152 amino acids) with ~12,000 amino acids of heavily O-glycosylated N-terminal region, a tandem repeat region comprising of approximately 60 repeats of 156 amino acids each, a transmembrane domain and a cytoplasmic tail of 32 amino acids (4) (Figure 1A). MUC16 harbors 56 SEA (sea urchin, enterokinase and agrin) domains, the highest among all mucins, and each SEA domain constitutes a major portion (amino acids 1-128) of each tandem repeat (5) (Figure 1A, black outlined box at the bottom left). MUC16 is predicted to undergo cleavage in the penultimate and/or last SEA domain and phosphorylation event(s) in the cytoplasmic tail domain (CTD) is (are) believed to be critical determinants of its cleavage (1, 6-8). Likewise, existence of splice forms without a transmembrane domain resulting in the secretory MUC16 has also been predicted (9). However, proper experimental validation is lacking to support these claims. Although thirty-five years have elapsed since the discovery of CA125 and fourteen years since it was identified to be MUC16, our understanding of the basic biological processes involving MUC16 cleavage, promoter characterization and therefore its regulation, existence of splice variants etc. are still rudimentary. Part of the problems in addressing these issues lies with the enormous size and complexity of this protein and lack of appropriate technical resources (such as antibodies for various regions of MUC16) in addressing these problems. In this review, we focus on how our understanding of some of these basic processes (particularly cleavage) impacts our outlook in exploiting the therapeutic potential of MUC16.

Figure. Implications of basic biological understanding of MUC16 in cancer therapy.

(A) Schematic representation of full-length MUC16 (with particular emphasis on the juxta-membrane ectodomain cleavage) and a prototype tandem repeat. MUC16 is composed of ~22,152 amino acids (aa) with ~12,000aa in the N-terminal domain which is exclusively O-glycosylated. This is followed by 60+ tandem repeats (TRs) of ~156aa each, of which a major part (approximately 1-128aa) is formed by the sea-urchin, enterokinase and agrin (SEA) domain. This TR domain is primarily O-glycosylated, but harbors sites of N-glycosylation too. A more detailed schematic of a prototype tandem repeat domain of MUC16 is illustrated within the box (lower left) with the likely location of the antigenic epitope of CA125 between the two-cysteine residues of the adjacent tandem repeats. Experimental and bioinformatics predictions suggest approximately five O-glycosylation and three N-glycosylation sites within the SEA domain stretch of the TR and approximately ten O-linked glycosylation sites in the linker region. The penultimate (55th, location of site # 2) and last (56th, location of site # 1) SEA domains of MUC16 were proposed to harbor the proteolytic sites for MUC16, however, did not turn out to be the true proteolytic sites in our experimental analyses. Instead, a stretch of 12aa (AWFPLDSNGTLP) proximal to the trnasmembrane (TM) domain was found to be sufficient for proteolytic processing of MUC16. However, it is not absolutely necessary for the cleavage, suggesting possible additional cleavage sites. Previous MUC16-based therapeutic studies using antibodies against the TR region (CA125) of MUC16 were quite unsuccessful. We therefore believe using drug-conjugated antibodies that bind to the juxta membrane ectodomain region of MUC16 (cell-associated MUC16-Cter) will result in better therapeutic efficiency. The positively charged RRRKK (blue colored and underlined) motif in the intracellular juxta-membrane region is shown to interact with ERM (ezrin-radixin-moesin) domain containing proteins, which in-turn can influence the cytoskeletal proteins such as actin. Both the lysines in the RRRKK motif in the cytoplasmic tail domain (CTD) undergo polyubiquitylation (Ub-n) and the designated tyrosine undergoes c-Src mediated phosphorylation. Functional significance of these post-translational modifications is yet to be elucidated.

(B) Proposed model for the proteolytic processing of MUC16. Following transcription, MUC16 protein synthesis is initiated in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER; pH~7.1) along with N-linked glycosylation. Further addition of N-linked and O-linked glycosylation takes place as it progresses through the cis-medial-trans Golgi apparatus. In addition, the juxta-membrane ectodomain cleavage of MUC16 takes place en-route to the plasma membrane in the acidifying Golgi (pH~7.0-6.0)/post-Golgi (pH~5.0) compartment(s). There could be four possibilities as a result (a) if the process of cleavage is not 100% efficient, full-length MUC16 would be present at the cell surface, (b) if the two cleaved fragment remain associated with each other following cleavage, would result in a hetero-dimeric MUC16, (c) the cleaved carboxyl-terminal fragment (MUC16-Cter) remain associated with the cells and, (d) the cleaved N-terminal fragment is secreted (sMUC16) from the cell. Inhibition of MUC16 cleavage can be achieved by the use of drugs such as breflate (pro-drug form of brefeldin-A) that induces fusion of Golgi to the ER.

(C) MUC16 interactome, its influence on oncogenic signaling and possible therapeutic intervention. (a) MUC16–Siglec-9: The inhibitory siglec-9 receptors on the surface of natural killer (NK) cells and monocytes can bind to MUC16 that is either released or attached to the cell surface of tumor cells, thereby exerting an inhibitory signal that protects the tumor cells from the cytotoxic effects of these immune cells. (b) MUC16–Galectin-1/3: MUC16 is believed to act as counter receptors for galectins such as Gal-1 and Gal-3, however, their functional implications in the context of tumorigenesis is yet to be deciphered. (c) MUC16–Mesothelin: N-glycosylation dependent binding of mesothelin expressed on the surface of mesothelial as well as tumor cells with either released or cell surface MUC16 on the tumor cells is believed to be a major mode of MUC16 mediated peritoneal metastasis. Besides, up regulation of MMP7 is yet another mechanism leading to enhanced metastatic propensity mediated by MUC16-mesothelin interaction. Disruption of MUC16-Mesothelin interaction using HN125 immunoadhesin and sensitizing MUC16 expressing cells to Meso-TR3 chimera to induce apoptosis are some of the novel targeting approaches using MUC16. (d) MUC16–Selectins: E-selectins expressed on the surface of endothelial cells and L-selectins on the surface of lymphocytes bind to the sialofucosylated structures on the surface of both N- and O-linked glycans of MUC16 and are proposed to be an important mediator for enhanced metastasis of cells expressing MUC16. (e) MUC16–JAK2: Interaction of MUC16 with cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase JAK2 can either lead to a STAT dependent up regulation of Cyclin-D1 resulting in increased proliferation (solid arrows) and/or a STAT independent (MUC16-Cter mediated) increased nuclear accumulation of JAK2 leading to up regulation of genes such as LMO2 and NANOG resulting in cancer stem cell phenotype and enhanced metastasis (dashed arrows).

MUC16: A historical perspective

In 1981, Robert C. Bast and colleagues developed a monoclonal antibody (i.e. OC125) that was reactive against epithelial ovarian cancer cells and cryopreserved tumor tissues from ovarian cancer patients, but not with the non-malignant tissue samples (10). The antigen that was reactive to this particular antibody was designated as cancer antigen 125, hence the name CA125. Although the antibody was developed with a therapeutic intent to treat the ovarian cancer patients, shedding of the antigen CA125 in to the circulation did not bode well for that purpose. Instead, detection of the antigen CA125 in the circulation was foreseen as an interesting opportunity to monitor the recurrent ovarian cancer and still is the current gold standard marker for recurrent ovarian cancer. Although the potential of using CA125 towards (i) monitoring the response to OC treatment, (ii) recurrence of the disease (OC) following treatment and/or (iii) early detection of the disease was soon realized, its molecular characterization took an overwhelmingly long two decades time till 2001, when Lloyd and O'Brien's groups independently demonstrated that CA125 is indeed a very large membrane bound mucin MUC16 (1-3). Since then, several groups including ours have attempted to characterize MUC16 with respect to its cleavage (11), trafficking (12), regulation of expression (13, 14) and its functional involvement in health and disease (15-21). Recently, Cheon D-J et al., generated and characterized a whole body Muc16 knock out mouse model (22). These mice are viable and fertile with lack of any apparent developmental defects (22) and therefore, can be employed as an interesting tool to address the basic questions related to Muc16/MUC16.

MUC16 Cleavage: A long-standing question

Since the molecular identity of CA125 was revealed to be a single pass transmembrane mucin MUC16 (2, 3), predictions have been made about its possible cleavage in the juxta-membrane SEA domains. Primarily, the PLARRVDR site (site #1) in the last (56th) (1) and DSVLV site (site #2, analogous to GSVVV site on MUC1) on the penultimate (55th) (6) SEA domains were thought to be major proteolytic sites (Figure 1A). However, this remained experimentally untested for more than a decade. Since carboxyl-terminal fragments of transmembrane mucins are hypothesized to be critical in mediating their signaling functions and MUC16 (CA125) being one the most widely used serum biomarker for ovarian cancer (23) and one of the top three frequently mutated gene across many tumor types (24), it is imperative to understand the cleavage of MUC16 if we are to understand its role in tumorigenesis. One of the major hurdles in addressing MUC16 cleavage has been lack of antibodies for the C-terminal region as most of the well characterized antibodies bind to the repetitive epitopes (i.e. CA125) in the tandem repeat region. To circumvent the lack of antibodies for the C-terminal MUC16, we used dual epitope tagging of various lengths of carboxyl-terminal MUC16 fragments to narrow down the potential site of cleavage. We observed that earlier predicted sites #1 and #2 are not essential for MUC16 cleavage, instead a novel stretch of 12 amino acids in the juxta-membrane ectodomain (PLTGNSDLPFWA) was found to be sufficient for MUC16 cleavage (11) (Figure 1A). While this novel stretch of 12 amino acids was found to be sufficient for MUC16 cleavage, it is not an absolute necessity, as deletion of this stretch did not result in complete abrogation of MUC16 cleavage (11). It can thus be speculated that MUC16 cleavage may not be entirely dependent on its primary amino acid sequence. Further, MUC16 cleavage was found to be dependent on the acidic pH of the Golgi and/or post-Golgi compartment (Figure 1B). Using a cytoplasmic tail domain swapped variant (MUC16-CTD was replaced with MUC4-CTD), we ruled out any involvement of intracellular cues along with the previous claims of cytoplasmic serine and/or threonine phosphorylation dependent MUC16 cleavage. In addition, involvement of proteases such as neutrophil elastase and MMP-7 were also ruled out (11).

While ours is the first study to experimentally demonstrate the oft-predicted MUC16 cleavage, several important questions are still needed to be answered. First, what is the exact mechanism of MUC16 cleavage? Is it autopreolteolytic or protease dependent? If protease dependent, what protease(s) is (are) involved in its cleavage? Since MUC16 cleavage takes place in the acidic pH of the Golgi and/or post-Golgi compartment and we have ruled out the possibility of intra-membrane cleavage (cleavage by γ-secretase, rhomboid protease and site-1/site-2 protease), any protease with low optimum pH would be responsible for its cleavage in case of protease dependency. Second, do the cleaved N-terminal and C-terminal fragments heterodimerize and stay on the cell surface or the N-terminal fragment is shed off the surface (generating circulating CA125) and only the MUC16-Cter stays on the surface (Figure 1B)? Third, since MUC16-Cter (without any obvious DNA binding domain) is localized into the nucleus and is found in the chromatin bound fraction, it is imperative to understand the mechanism of its nuclear translocation and chromatin enrichment (the putative nuclear localization sequence RRRKK is not required for nuclear localization)?

Role of MUC16 (MUC16-Cter) in Tumorigenesis and Metastasis

Although CA125 is widely used as the serum biomarker for ovarian cancer and most of the studies have investigated the role of MUC16 in ovarian cancer, recent studies have shown that MUC16 is over expressed in multiple tumor types including breast, pancreatic and colorectal cancer etc (25, 26). In addition, it is found to be one of the top three frequently mutated gene across multiple tumor types (24). Owing to the clinical importance of MUC16 (CA125) as a biomarker, several studies have attempted to address the functional significance of MUC16 in multiple tumor cells primarily using shRNA mediated knockdown approach and have been reviewed elsewhere (17). Due to space constraints, we discuss here the less explored carboxyl-terminal MUC16 and its role in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Since MUC16 was predicted to undergo cleavage in the last and/or penultimate SEA domain, various groups have ectopically expressed different lengths of carboxyl-terminal MUC16 in an attempt to address its functional role. In one of the very first study, Boivin et al., ectopically expressed 283 amino acid long carboxyl-terminal fragment of MUC16 in SKOV3 ovarian cancer cells that resulted in reduced sensitivity of MUC16-Cter expressing cells towards cisplatin by attenuating apoptosis (18). Mechanistically, MUC16-Cter was shown to impart resistance to TRAIL induced apoptosis by reducing the expression of TRAIL receptor-2 (also known as death receptor DR5) and increasing the expression of cellular FLICE inhibitory protein (cFLIP) (19). Subsequently, the same group demonstrated that the 283 amino acids long MUC16-Cter was sufficient to impart enhanced tumorigenic and metastatic properties to SKOV3 cells in vitro and in vivo in a cytoplasmic tail domain (CTD) dependent manner (27). In another recent study Akita et al., demonstrated enhanced migratory potential of breast and colon cancer cells upon ectopic expression of 413 amino acids long MUC16-Cter fragment (20). Finally, MUC16-Cter (283 amino acids) was shown to transform NIH3T3 cells in a CTD dependent manner demonstrating its oncogenic potential (21).

While all the above studies addressed the functional significance of carboxyl-terminal MUC16, none of these studies have attempted to substantiate whether MUC16 indeed undergoes cleavage to generate the MUC16-Cter. Using a dual epitope tagged 114 amino acids long fragment of carboxyl-terminal MUC16 we demonstrated the generation of ~17 kDa MUC16-Cter that was capable of imparting tumorigenic and metastatic phenotypes to pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo (15). Mechanistically, we demonstrated that MUC16-Cter mediated nuclear enrichment of JAK2 leads to up-regulation of stemness specific genes such as LMO2 and NANOG resulting in accumulation of ALDH+ pancreatic cancer stem-like cells (15) (Figure 1C). With experimental demonstration of MUC16 cleavage, further basic understanding of the mechanism(s) of the involvement of MUC16-Cter in tumorigenicity and metastasis would be necessary in order for us to devise therapeutic intervention.

MUC16 as a potential therapeutic target

Owing to the clinical importance of CA125, several studies have attempted to target MUC16 therapeutically, primarily using antibodies directed against the tandem repeat domains of MUC16, where the CA125 epitopes have been hypothesized to reside. Use of antibody based therapeutics such as Oregovomab (a modified murine MAb-B43.13 that binds with high affinity to CA125) (28) and Abagovomab (an anti-idiotypic antibody produced by mouse hybridoma against CA125) (29) in Phase II and III clinical trials against OC patients were met with limited success respectively. One of the major reasons for the failure of these therapies could be attributed to our incomplete understanding of the basic cellular processing of MUC16 such as cleavage (30). Since these antibodies bind to the circulating (or shed) CA125, it is highly likely that these antibodies do not reach cancer cells. In addition, our lack of understanding of the kinetics and dynamics of MUC16 cleavage thwarts our efforts to prevent MUC16 shedding, which in turn reduces the therapeutic efficacy of these antibodies (30). Therefore, antibodies against the carboxyl-terminal portion of MUC16 are urgently required. Dharma Rao et al., generated several monoclonal antibodies targeting the membrane proximal ectodomain and the CTD of MUC16. These antibodies are shown to be effective in multiple applications, therefore, are expected to be useful in diagnostics and therapeutics (31). However, these antibodies are generated assuming cleavage of MUC16 at PLARRVDR site (site #1), 50 residues upstream of the TM domain and therefore may not be very efficient in binding the cell-associated MUC16-Cter (as 12 residues upstream of the TM domain are sufficient for MUC16 cleavage). Therefore in addition to the above-mentioned antibodies, additional antibodies towards carboxyl-terminal MUC16 including the membrane proximal 12 residues (Figure 1A) will be critical for diagnostic and therapeutic targeting using MUC16. The antibodies for the carboxyl-terminal portion of MUC16 that remains associated with the tumor cells can be exploited to design MUC16 based immunotherapeutic modalities such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). For example, adoptive transfer of T-cells transduced with MUC16-Cter specific CAR generated using single chain variable fragment (scFv) from the VH and VL chains of the 4H11 antibody against the juxta-membrane ectodomain of MUC16, CD28 transmembrane and cytoplasmic signaling domain and TCRζ cytoplasmic signaling domain (4H11-28z-MUC-CD) into SCID-Beige mice bearing ovarian tumor was shown to be highly effective in killing MUC16-Cter+ ovarian cancer cells (32). However, further in-depth characterization should be carried out to evaluate the therapeutic potential of immunotherapies based on CAR.

Besides antibody-based therapeutics, approaches that interfere with the cleavage of MUC16 offer promising platforms for MUC16 based therapeutics. Preventing cleavage of MUC16 should be considered an alternative approach to the existing MUC16 based therapeutics for two reasons. First, preventing MUC16 cleavage would increase the cell surface representation of MUC16, which will enhance the efficacy of antibody-based therapeutics such as Oregovomab and Abagovomab. Second, since nuclear localization of MUC16 is cleavage dependent, abrogation of MUC16 cleavage would reduce the nuclear functions of MUC16-Cter. Since cleavage of MUC16 takes place in the Golgi/post-Golgi compartments, use of a pro-drug form of brefeldin-A (Breflate, NSC656202) (33), that induces fusion of Golgi to the endoplasmic reticulum resulting in a rapid and reversible block in the secretory pathway, can be considered an interesting approach to inhibit MUC16 cleavage (Figure 1B). An increased reliance of cancer cells on the secretory pathway than their normal counter parts can be exploited to reduce the toxicity of breflate towards normal cells.

Efforts to disrupt the functional co-operation of MUC16 and its interacting partners are viewed as interesting therapeutic intervention in addition to antibody and cleavage based therapeutics. MUC16 has been shown to interact with galectin-1 (O-glycosylation dependent) (12), galectin-3 (O-glycosylation dependent) (34), siglec-9 (sialic acid dependent) (35), mesothelin (N-glycosylation dependent) (36) and E- and P-selectins (dependent on the sialofucosylated epitopes on both O- and N-glycosylation sites) (37) through the extracellular glycosylated portion and with ezrin/radixin/moesin (ERM) (38), c-Src (20) and JAK2 (possibly by the FERM domain of JAK2, however has not been directly demonstrated) (39) through the intracellular cytoplasmic tail domain. Among all the interacting partners of MUC16 known thus far, mesothelin-MUC16 interaction is the best exploited in terms of therapeutic intervention (40, 41) and therefore are discussed here. N-glycosylation dependent interaction of MUC16 with mesothelin (amino acids 296-359 known as IAB region) expressed on the surface of mesothelial cells of the peritoneal wall is critical in peritoneal metastasis of OC cells (41). Xiang et al., exploited this MUC16-mesothelin interaction by generating a human immunoadhesin where the IAB region of mesothelin was fused with the N-terminal Fc portion of human IgG1 (termed as HN125) (41) (Figure 1C). This novel immunoadhesin HN125 served two purposes: first, it competitively inhibits the interaction of MUC16 on cancer cells with mesothelin on mesothelial cells, and second, upon binding of HN125 with the MUC16 on cancer cells elicits antibody dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC), thereby killing the cancer cells (41). On the similar line of thoughts, Garg et al., generated a meso-TR3 chimera, where the secretory form of mesothelin (devoid of GPI-anchor) was fused on the N-terminal side of TR3 (a genetically fused trimer of TRAIL), a ligand for the activation of death receptor pathway (40). Mesothelin of Meso-TR3 complex provides specificity towards cancer cells that express MUC16 on the cell surface and subsequent interaction of DR3 with the DRs would lead to killing of cancer cells (40) (Figure 1C). Although, HN125 and Meso-DR3 are novel means of targeting MUC16 positive cancer cells, further characterizations using preclinical models would be necessary to validate their therapeutic potential before being tried in clinical trials.

Conclusions and Perspectives

MUC16, besides being the precursor for the most widely used biomarker for recurrent OC CA125, has been found to play active role in tumorigenesis and metastasis of ovarian, pancreatic and breast cancer etc. In addition, we are only beginning to understand the basic biological processes and functions of MUC16 such as cleavage, identification of CA125 epitope on MUC16, mechanistic involvement of MUC16-Cter in tumorigenesis and metastasis etc. However, a thorough and complete understanding of this complex protein in terms of mechanism of cleavage, generation of circulating CA125, nuclear translocation and subsequent gene regulation, identification of protein partners that mediate its functions, effects of post-translational modifications on its functions and stability, promoter characterization and regulation of its expression, identification of splice variants (if exists) and their context of splicing etc. would be required to realize the full potential MUC16 in terms of disease diagnostics and therapeutics.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors on this work, in part, are supported by grants from the Department of Defense BC101014 and NIH (TMEN U54 CA163120, EDRN UO1, CA111294, SPORE P50 CA127297, RO3 CA167342 and RO1 CA183459).

References

- 1.O'Brien TJ, Beard JB, Underwood LJ, Dennis RA, Santin AD, York L. The CA 125 gene: An extracellular superstructure dominated by repeat sequences. Tumour Biol. 2001;22:348–66. doi: 10.1159/000050638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Brien TJ, Beard JB, Underwood LJ, Shigemasa K. The CA 125 gene: A newly discovered extension of the glycosylated N-terminal domain doubles the size of this extracellular superstructure. Tumour Biol. 2002;23:154–69. doi: 10.1159/000064032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin BW, Dnistrian A, Lloyd KO. Ovarian cancer antigen CA125 is encoded by the MUC16 mucin gene. Int J Cancer. 2002;98:737–40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Govindarajan B, Gipson IK. Membrane-tethered mucins have multiple functions on the ocular surface. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:655–63. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcos-Silva L, Narimatsu Y, Halim A, Campos D, Yang Z, Tarp MA, et al. Characterization of binding epitopes of CA125 monoclonal antibodies. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:3349–59. doi: 10.1021/pr500215g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macao B, Johansson DG, Hansson GC, Hard T. Autoproteolysis coupled to protein folding in the SEA domain of the membrane-bound MUC1 mucin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:71–6. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fendrick JL, Konishi I, Geary SM, Parmley TH, Quirk JG, Jr, O'Brien TJ. CA125 phosphorylation is associated with its secretion from the WISH human amnion cell line. Tumour Biol. 1997;18:278–89. doi: 10.1159/000218041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konishi I, Fendrick JL, Parmley TH, Quirk JG, Jr, O'Brien TJ. Epidermal growth factor enhances secretion of the ovarian tumor-associated cancer antigen CA125 from the human amnion WISH cell line. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 1994;1:89–96. doi: 10.1177/107155769400100118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodell CA, Belisle JA, Gubbels JA, Migneault M, Rancourt C, Connor J, et al. Characterization of the tumor marker muc16 (ca125) expressed by murine ovarian tumor cell lines and identification of a panel of cross-reactive monoclonal antibodies. J Ovarian Res. 2009;2:8,2215–2-8. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bast RC, Jr, Feeney M, Lazarus H, Nadler LM, Colvin RB, Knapp RC. Reactivity of a monoclonal antibody with human ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 1981;68:1331–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI110380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Das S, Majhi PD, Al-Mugotir MH, Rachagani S, Sorgen P, Batra SK. Membrane proximal ectodomain cleavage of MUC16 occurs in the acidifying golgi/post-golgi compartments. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9759. doi: 10.1038/srep09759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seelenmeyer C, Wegehingel S, Lechner J, Nickel W. The cancer antigen CA125 represents a novel counter receptor for galectin-1. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1305–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiong L, Woodward AM, Argueso P. Notch signaling modulates MUC16 biosynthesis in an in vitro model of human corneal and conjunctival epithelial cell differentiation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5641–6. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seo KY, Chung SH, Lee JH, Park MY, Kim EK. Regulation of membrane-associated mucins in the human corneal epithelial cells by dexamethasone. Cornea. 2007;26:709–14. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31804f5a09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Das S, Rachagani S, Torres-Gonzalez MP, Lakshmanan I, Majhi PD, Smith LM, et al. Carboxyl-terminal domain of MUC16 imparts tumorigenic and metastatic functions through nuclear translocation of JAK2 to pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:5772–87. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haridas D, Chakraborty S, Ponnusamy MP, Lakshmanan I, Rachagani S, Cruz E, et al. Pathobiological implications of MUC16 expression in pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haridas D, Ponnusamy MP, Chugh S, Lakshmanan I, Seshacharyulu P, Batra SK. MUC16: Molecular analysis and its functional implications in benign and malignant conditions. FASEB J. 2014;28:4183–99. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-257352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boivin M, Lane D, Piche A, Rancourt C. CA125 (MUC16) tumor antigen selectively modulates the sensitivity of ovarian cancer cells to genotoxic drug-induced apoptosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;115:407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matte I, Lane D, Boivin M, Rancourt C, Piche A. MUC16 mucin (CA125) attenuates TRAIL-induced apoptosis by decreasing TRAIL receptor R2 expression and increasing c-FLIP expression. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:234,2407–14-234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akita K, Tanaka M, Tanida S, Mori Y, Toda M, Nakada H. CA125/MUC16 interacts with src family kinases, and over-expression of its C-terminal fragment in human epithelial cancer cells reduces cell-cell adhesion. Eur J Cell Biol. 2013;92:257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giannakouros P, Matte I, Rancourt C, Piche A. Transformation of NIH3T3 mouse fibroblast cells by MUC16 mucin (CA125) is driven by its cytoplasmic tail. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:91–8. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheon DJ, Wang Y, Deng JM, Lu Z, Xiao L, Chen CM, et al. CA125/MUC16 is dispensable for mouse development and reproduction. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mai PL, Wentzensen N, Greene MH. Challenges related to developing serum-based biomarkers for early ovarian cancer detection. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:303–6. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim N, Hong Y, Kwon D, Yoon S. Somatic mutaome profile in human cancer tissues. Genomics Inform. 2013;11:239–44. doi: 10.5808/GI.2013.11.4.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streppel MM, Vincent A, Mukherjee R, Campbell NR, Chen SH, Konstantopoulos K, et al. Mucin 16 (cancer antigen 125) expression in human tissues and cell lines and correlation with clinical outcome in adenocarcinomas of the pancreas, esophagus, stomach, and colon. Hum Pathol. 2012;43:1755–63. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimizu A, Hirono S, Tani M, Kawai M, Okada K, Miyazawa M, et al. Coexpression of MUC16 and mesothelin is related to the invasion process in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:739–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Theriault C, Pinard M, Comamala M, Migneault M, Beaudin J, Matte I, et al. MUC16 (CA125) regulates epithelial ovarian cancer cell growth, tumorigenesis and metastasis. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:434–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berek JS, Taylor PT, Gordon A, Cunningham MJ, Finkler N, Orr J, Jr, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled study of oregovomab for consolidation of clinical remission in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3507–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabbatini P, Harter P, Scambia G, Sehouli J, Meier W, Wimberger P, et al. Abagovomab as maintenance therapy in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: A phase III trial of the AGO OVAR, COGI, GINECO, and GEICO--the MIMOSA study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1554–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Felder M, Kapur A, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Horibata S, Heintz J, Albrecht R, et al. MUC16 (CA125): Tumor biomarker to cancer therapy, a work in progress. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:129,4598–13-129. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-13-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dharma Rao T, Park KJ, Smith-Jones P, Iasonos A, Linkov I, Soslow RA, et al. Novel monoclonal antibodies against the proximal (carboxy-terminal) portions of MUC16. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2010;18:462–72. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3181dbfcd2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chekmasova AA, Rao TD, Nikhamin Y, Park KJ, Levine DA, Spriggs DR, et al. Successful eradication of established peritoneal ovarian tumors in SCID-beige mice following adoptive transfer of T cells genetically targeted to the MUC16 antigen. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3594–606. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carew JS, Nawrocki ST, Krupnik YV, Dunner K, Jr, McConkey DJ, Keating MJ, et al. Targeting endoplasmic reticulum protein transport: A novel strategy to kill malignant B cells and overcome fludarabine resistance in CLL. Blood. 2006;107:222–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Argueso P, Guzman-Aranguez A, Mantelli F, Cao Z, Ricciuto J, Panjwani N. Association of cell surface mucins with galectin-3 contributes to the ocular surface epithelial barrier. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23037–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belisle JA, Horibata S, Jennifer GA, Petrie S, Kapur A, Andre S, et al. Identification of siglec-9 as the receptor for MUC16 on human NK cells, B cells, and monocytes. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:118,4598–9-118. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gubbels JA, Belisle J, Onda M, Rancourt C, Migneault M, Ho M, et al. Mesothelin-MUC16 binding is a high affinity, N-glycan dependent interaction that facilitates peritoneal metastasis of ovarian tumors. Mol Cancer. 2006;5:50. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-5-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen SH, Dallas MR, Balzer EM, Konstantopoulos K. Mucin 16 is a functional selectin ligand on pancreatic cancer cells. FASEB J. 2012;26:1349–59. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-195669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blalock TD, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Tisdale AS, Heimer SR, Gilmore MS, Ramesh V, et al. Functions of MUC16 in corneal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4509–18. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lakshmanan I, Ponnusamy MP, Das S, Chakraborty S, Haridas D, Mukhopadhyay P, et al. MUC16 induced rapid G2/M transition via interactions with JAK2 for increased proliferation and anti-apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:805–17. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garg G, Gibbs J, Belt B, Powell MA, Mutch DG, Goedegebuure P, et al. Novel treatment option for MUC16-positive malignancies with the targeted TRAIL-based fusion protein meso-TR3. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:35,2407–14-35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiang X, Feng M, Felder M, Connor JP, Man YG, Patankar MS, et al. HN125: A novel immunoadhesin targeting MUC16 with potential for cancer therapy. J Cancer. 2011;2:280–91. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]