Abstract

Although the importance of large noncoding RNAs is increasingly appreciated, our understanding of their structures and architectural dynamics remains limited. In particular, we know little about RNA folding intermediates and how they facilitate the productive assembly of RNA tertiary structures. Here, we report the crystal structure of an obligate intermediate that is required during the earliest stages of group II intron folding. Comprised of intron domain 1 from the Oceanobacillus iheyensis group II intron (D1, 266 nts), this intermediate retains native-like features but adopts a compact conformation in which the active-site cleft is closed. Transition between this closed and open (native) conformation is achieved through discrete rotations of hinge motifs in two regions of the molecule. The open state is then stabilized by sequential docking of downstream intron domains, suggesting a “first comes, first folds” strategy that may represent a generalizable pathway for assembly of large RNA and ribonucleoprotein structures.

Introduction

It is becoming increasingly clear that most cellular processes involve the coordinated action of large RNA molecules, many of which adopt complex tertiary structures. As our interest in RNA function and RNA nanotechnology grows, it is essential to expand our understanding of RNA assembly mechanisms. There is no single model for RNA architectural assembly, but several major themes have emerged. One of the earliest models involves rapid collapse to a stable, but kinetically trapped, RNA structure that requires subsequent rearrangement by chaperone proteins to adopt the active native state (chaperone-dependent remodeling)1–3. A second model involves autonomous folding of individual RNA subdomains, which subsequently coalesce to form the native structure (direct, multi-step folding)2. A model related to direct, multi-step folding is direct, templated folding, in which one folded RNA domain serves as a scaffold for assembly of the other domains4,5, similar to classical models for the folding of certain proteins6–8. If the template domain is the first to be transcribed (i.e. corresponding to the 5′-region of the molecule), this pathway is particularly effective in ensuring an orderly, sequential process for downstream RNA assembly.

Group II introns are large, multidomain RNA sequences that fold into active structures and catalyze their own excision from flanking RNA, with concomitant splicing of the surrounding exons (self-splicing)9. Once released, these ribozymes can reinsert themselves into new RNA and DNA sequences and new hosts, where they function as genetic parasites10. Given this behavior, one might expect that group II introns would fold with considerable autonomy from host factors. Indeed, studies of a yeast mitochondrial group II intron (ai5γ) have shown that the 5′-end domain (Domain 1, D1) folds first, serving as a template for rapid, faithful assembly of the other five domains (D2-D6)4. The result is a direct, ordered folding pathway for a very large RNA molecule (>400 nucleotides). Such a folding pathway is not idiosyncratic to group II introns and may represent a general strategy that is adopted by other large, multidomain RNAs11.

Structural information on RNA folding intermediates is exceedingly limited12,13 and there is no high-resolution structure of an RNA folding intermediate. As a result, we lack critical information about the assembly mechanisms for multidomain RNAs. To attack this problem, we set out to solve the structure of isolated group II intron D1, and to compare it with D1 of an intact group II intron of known structure14,15.

Results

Rational design of crystallization lattice

Although crystallization strategies for multidomain Oceanobacillus iheyensis (O.i.) group II constructs are now robust and wellestablished14,15, crystallization of isolated O.i. D1 was remarkably difficult. D1 constructs containing the native sequence (with or without the flanking 5′-exon) failed to produce crystals that diffract to better than 3.8 Å resolution. This low resolution, combined with apparent twinning defects, prohibited structure determination. To solve this problem, we explored surface mutations to improve crystal contacts. We noticed that crystallizability was sensitive to the length and composition of the base-paired region in terminal stem-loop c, which suggested the involvement of this stem-loop in crystal packing16. After testing a variety of mutants, we succeeded in obtaining high quality diffraction by substituting the original GCGA tetraloop in stem c (90-93) with a canonical GAAA tetraloop.

This mutant enabled us to solve the structure of isolated O.i. D1, joined to its 5′-exon (construct D1iso, 266 nts, Fig. 1a and Supplementary Results, Supplementary Fig. 1a), at 3.0 Å by single-wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) using an Ir(NH3)63+ derivative (Supplementary Table 1). Crystals belong to the P21 space group, with two similar molecules (D1iso-A and D1iso-B, Supplementary Fig. 1b) forming the asymmetric unit. While both are reported in the accompanying data, only D1iso-A will be discussed in detail (as D1iso). The D1iso-A and D1iso-B from neighboring unit cells interact with each other through a tight interface along the unit cell c axis (Supplementary Fig. 8). D1iso differs from D1 of the full length intron (D1full) by an overall root mean square deviation (RMSD) of about 4.0 Å (4.2 Å for D1iso-A and 4.0 Å D1iso-B), which explains why experimental phase information was necessary for structure determination, and why molecular replacement attempts using either intact D1 or D1 fragments from the full-length intron as the searching models failed17,18.

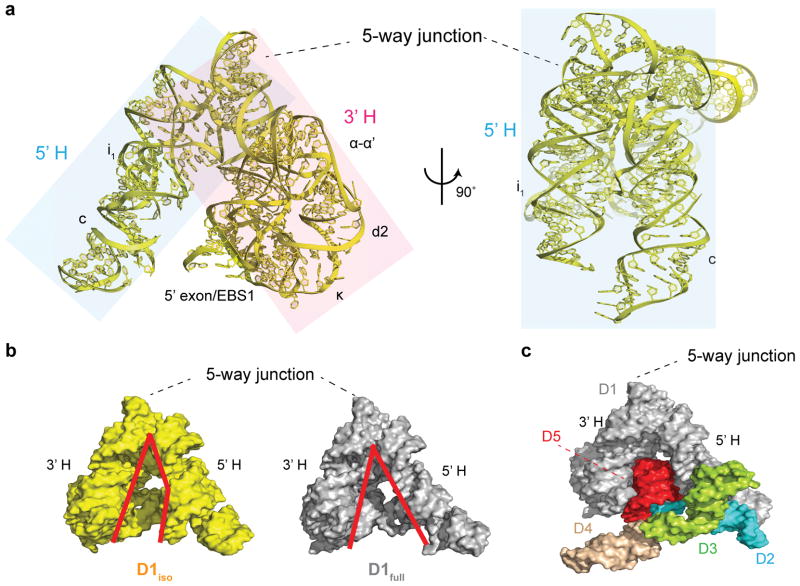

Figure 1.

D1 structure in the presence and absence of downstream domains. (a) Two views of D1iso (yellow) rotated by 90°. The 5′ half (5′H) and the 3′ half (3′H) of the clam-like D1 are shaded in blue and pink. (b) Surface representation of D1iso (yellow) and D1full (gray). The red lines indicate the outline of the cleft between the 5′H and the 3′H of the clam-like D1. (c) The structure of the full-length intron. D1 (D1full), D2, D3, D4 and D5 are colored in gray, blue, green, wheat and red.

Isolated D1 adopts a native-like conformation

Despite the large RMSD, D1iso adopts a native-like structure that is globally similar to D1full (Fig. 1a and Fig. 1b). All secondary structural elements and junction motifs are intact in D1iso, as are known tertiary interactions within D1, including the Z-anchor, T-loop, α-α′ and ω-ω′ (Supplementary Fig. 1a)15. Furthermore, the 5′ exon of D1iso is properly paired with exon binding site 1 (EBS1) (Supplementary Fig. 4a), although the linker between the 5′ exon and the terminal i1 stem is disordered. The fact that EBS1-5′exon duplex can form in the absence of D5 and other catalytic domains indicates that intron recognition of the 5′ exon can occur prior to active site formation. Despite the loss of an extensive molecular interface with D5 and other domains, and despite major differences in crystallization conditions, approximately one third of the structural ions identified in D1full19 are also found in D1iso (Supplementary Fig. 2). Accurate formation of the overall tertiary structure in D1 is consistent with previous studies indicating that D1 can fold properly on its own4,20, and that it can be combined with separate catalytic domains in trans to stimulate catalysis21. These findings are also consistent with folding experiments on D1iso (using both the wild type sequence and the crystallization construct), which reveal similar Mg2+ requirements for global compaction of D1iso and the full-length intron (Supplementary Fig. 3).

A rigid five-way junction provides the framework for D1

Given the architectural similarities between D1iso and D1full, we set out to determine which regions of the structure are most important for dictating the overall shape of D1. The central five-way junction appears to be particularly rigid, as it remains superimposable and constant when comparing D1iso with D1full (Fig. 1b). In D1iso, residues with the lowest crystallographic B-factors are clustered within the five-way junction (Fig. 2a, Fig. 2b and Fig. 2c). Additionally, d12, d13 and ω′ have B-factors that are lower than average, probably because of coaxial stacking (d12 and d13) and ribose zipper (ω′) interactions with the five-way junction (Fig. 2b and Fig. 2c). Since low B-factors are generally attributable to the low mobility and reduced thermo-vibration of the atoms in the crystal22, the observed B-factor distribution pattern suggests that the five-way junction is the most rigid structural element in D1iso, and its stabilization effects appear to radiate outward through strong contacts with adjacent substructures.

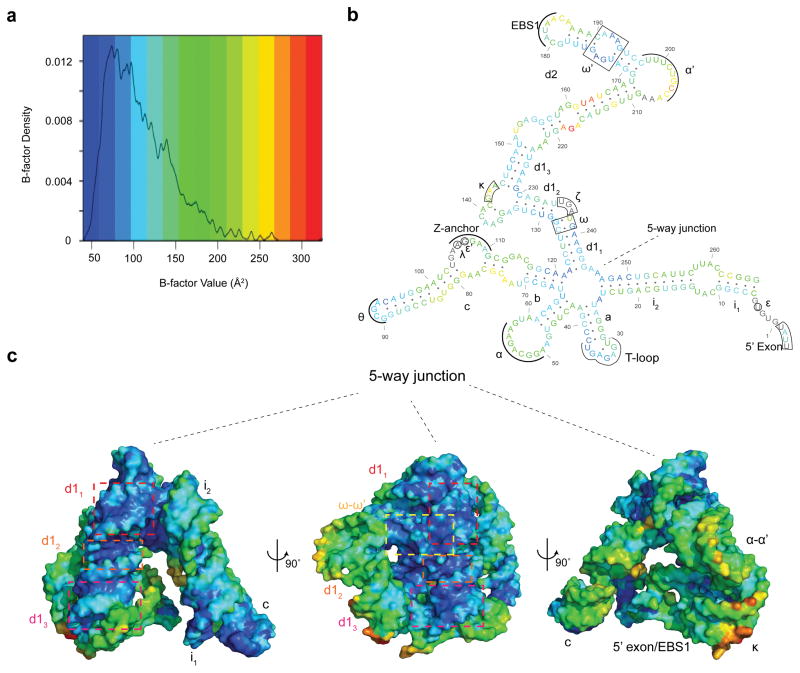

Figure 2.

Crystallographic B-factor distribution in D1iso. (a) Density plot of B-factors in D1iso. The B-factor value (non-normalized) is color-coded by a blue-to-red spectrum. The same spectrum is also used in (b) and (c). (b) Secondary structure color-coded by average B-factor for each residue in D1iso. The residues that are not modeled are colored in gray. (c) D1iso tertiary structure color-coded by atomic B-factors. d11, d12, d13 and ω-ω′ interaction are indicated by red, orange, magenta and yellow boxes.

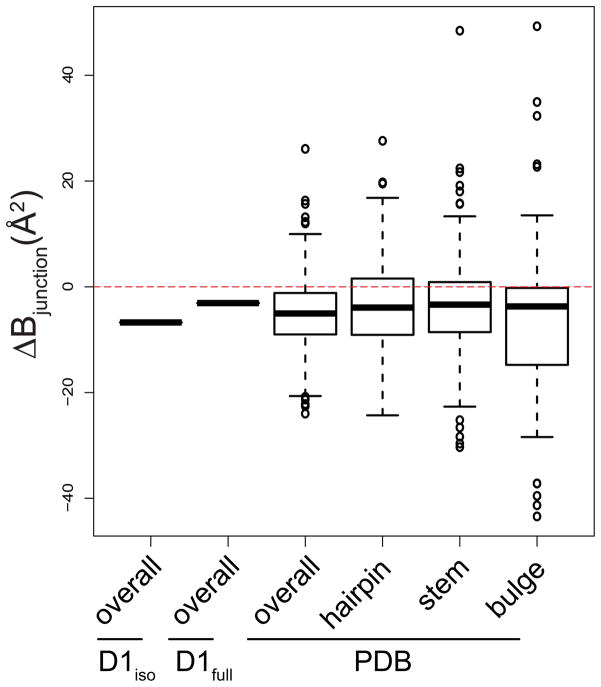

To assess whether junctions are also rigid elements in other RNA structures, we examined the B-factors for all RNA entries present in the protein data bank (PDB) as of October 2014. Specifically, we calculated differences in the average B-factor between nucleotides in junction motifs and other RNA structure motifs, such as stems, hairpins and bulges. Our analysis revealed that RNA junctions (three-way and higher) in about 75 % of the RNA structures display lower B-factors relative to all other RNA motifs that were analyzed (Fig. 3). Thus, RNA junctions may commonly provide a rigid frame for the assembly of tertiary structural units. However, not all RNA junctions are rigid, especially within RNA-protein complexes, which are not included in this analysis. In fact, a recent study on the 30s ribosomal subunit identified a dynamic hinge residue in a three-way junction that mediates head rotation23.

Figure 3.

Box plot showing difference average B-factors between the junction residues (denoted as ΔBjunction, on y-axis) and specific motifs taken from D1iso, D1full and from all RNA entries in PDB (x-axis). “Overall” means ΔBjunction is the difference between junction residues and all residues in a specific structure. “Stem”, “hairpin” and “bulge” means the ΔBjunction is the difference between junction residues and stem, hairpin and bulge residues in a specific structure. The red dashed line indicates zero ΔBjunction value. For the D1iso and D1full group, the thick band indicates a single value. For groups from “PDB”, the thick band indicates the median, the box indicates the upper and lower quantiles, the vertical line indicates the variability, and the individual dots represent outliers.

Isolated D1 is in a compact, closed state

Despite their overall architectural similarities, D1iso adopts a more compact conformation than D1full (Fig. 1b). The clam-like D1 structure is open in D1full, which contains a large opening between the two halves of its structure (5′H and 3′H), where stems i1 and c belong to the 5′H and the rest of the molecule, including α-α′ and κ motifs, belongs to the 3′H (Fig. 1a, Fig 1b and Fig 1c)24. This large opening enables D1full to grasp the D5 hairpin (in red, Fig. 1c), buttressing it with D2-D4, and thereby supporting active-site formation. By contrast, deprived of D2-4, D1iso adopts a closed conformation (Fig. 1b), which effectively blocks the active site and prevents D5 from entering into or even fitting within the central cavity. The closed conformation observed for D1iso may represent a low energy state that is favored in isolation, or D1 may stochastically sample the closed and open states (Supplementary Movie 1). In an attempt to understand any transition between these states, we characterized the exact structural differences between the open and closed states of D1 (Fig. 1b).

Dynamic hinges mediate a transition to the open state

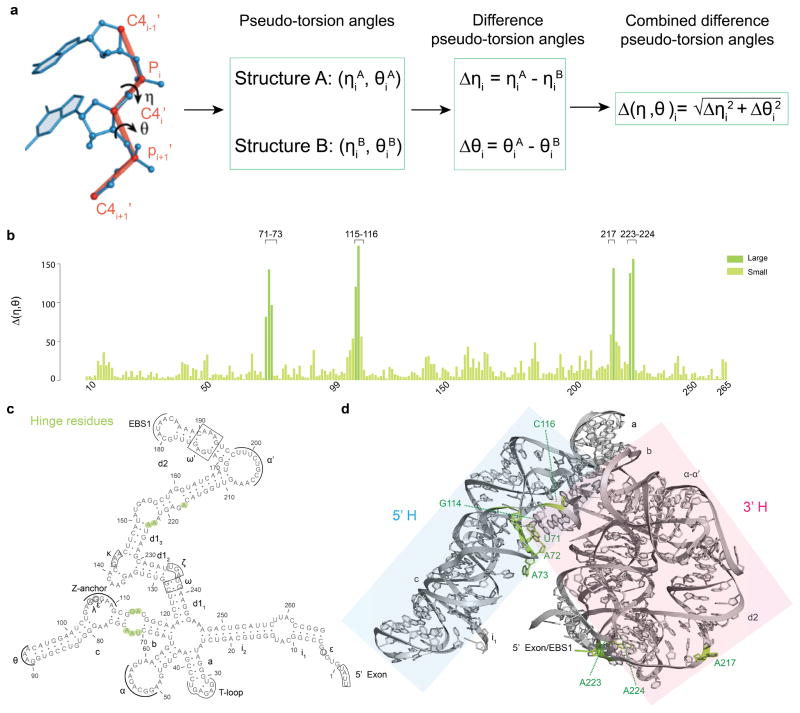

Compression of the D1 structure is mediated, in part, by a ~20° rotation of terminal stem i1 and c toward the inner cavity where D5 binding takes place (Fig. 1c). In addition, the 5′H and 3′H halves of the D1 structure compress through a set of apparent hinge motions. To rigorously identify the position and conformational transitions of rotation points and hinges, we sought an unbiased way to compare structural differences between D1iso and D1full, using a structural analysis method for comparing related RNA molecules of identical sequence. The commonly used RMSD of atomic positions is not suitable for this purpose because it does not provide specific information on domain motions on a global scale, and it does not reveal angular information.

To characterize structural differences between D1iso and D1full, we adapted an alternative computational method that has been successfully employed to identify specific motifs within RNA structures, to quantitatively analyze conformational changes upon ligand binding, and to model RNA into electron density25–27. This approach takes advantage of the fact that local and global RNA structure can be accurately reflected by a string of angular coordinates (called η and θ) that are analogous to dihedral angles φ and ψ in protein structures (Fig. 4a)25. In RNA, the η and θ angles (which describe the angular position of vectors connecting sequential P and C4′ atoms of the RNA backbone) (Fig. 4a) provide a computationally efficient and mathematically discreet way to identify and describe structural differences at specific sites in RNA molecules of any size25–27.

Figure 4.

Difference pseudo-torsion angle (Δ(η,θ)) between D1iso and D1full. (a) Schematic of difference pseudo-torsion angle calculation. The definition of RNA pseudo-torsion angles are shown on the left20, and the procedure of calculating the difference pseudo-torsion angles and the combined difference pseudo-torsion angle is presented as a flow chart. (b) Plot showing Δ(η,θ) values (y-axis) for residues in D1iso (x-axis). The deep green and the light green color indicate two Δ(η,θ) class with large and small values. Because of chain breaks, only residues 7-81, 85-99, 109-137, 141-205, 210-265 are involved in the analysis. (c) Secondary structure showing residues with large Δ(η,θ) (green). (d) Tertiary structure showing residues with large Δ(η,θ) (green). The 5′H and the 3′H are shaded in blue and pink.

We therefore parameterized the structures of D1iso and D1full by creating a string of η and θ coordinates for each molecule. Using this approach, each residue “i” (except for the terminal 5′ and 3′ nucleotides) is described by a characteristic set of (ηi, θi) values (Fig. 4a)25–27. When comparing the structure of two closely related RNA molecules26, for the same residue i, one can calculate the difference in ηi and θi as . Using this simplified, effective and quantitative comparison of the RNA backbone, we rapidly pinpointed the key residues that mediate hinge motions in D1. Specifically, when comparing the η and θ angles from D1iso and D1full, we found large differences in pseudo-torsion angles (Δ(η,θ)) within a few local regions of the D1 structure (Fig. 4b). The nucleotides with the largest Δ(η,θ) values specifically involve 8 of the total 229 residues analyzed (Fig. 4b, Fig. 4c and Fig. 4d), and they occur in both “halves” (5′H and 3′H) of D1. Interestingly, these 10 residues are clustered within specific internal loops, suggesting that the loops function like molecular hinges (Fig. 4c and Fig. 4d). Nucleotides having small Δ(η,θ) values are located within rigid helical stems and junctions (Fig. 4c and Fig. 4d). Taken together, the Δ(η,θ) map reveals a molecular architecture in which rigid rods (the helices) and static junctions are connected by mobile hinges (internal loops) that modulate opening and closing of the D1 structure. Coordinated motion of these hinges may be mediated by the 5′-exon/EBS1 interaction, which spans and connects the 5′H and 3′H portion of the molecule (Fig. 4d, Supplementary Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 4c). This is consistent with experimental data showing that the 5′-exon facilitates group II intron folding28.

There are no changes in base stacking or hydrogen-bonding networks between the open and closed states of D1, implying that any transition between these states (Supplementary Movie 1) is facile and energetically inexpensive. Importantly, none of the hinge residues contain nucleotides that interact with downstream intron domains, indicating that the hinges act specifically to control D1 conformation rather than the docking of other domains. This behavior contrasts with our analysis of the isolated P456 domain of the Tetrahymena thermophila group I intron (Supplementary Fig. 5a)29,30, in which the majority of nucleotides with large Δ(η,θ) values mediate direct interactions with other intron domains (Supplementary Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 5d), consistent with the role of P456 as a component, rather than a template for group I intron folding. Difference pseudotorsion angle analysis on RNA structures is therefore useful for pinpointing and characterizing the mechanical role of flexible elements, such as loops, and revealing different mechanisms by which flexibility can facilitate RNA folding.

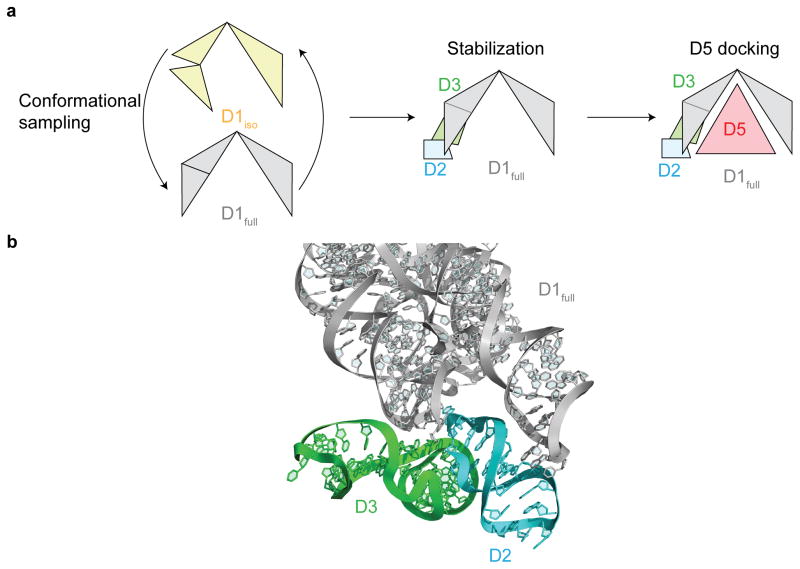

D1 is a template for assembly of the intact intron

The manner in which D1iso rearranges to D1full suggests a specific pathway for intron assembly. While D1 is likely to sample both the closed and open states (Supplementary Movie 1), sequential formation of inter-domain interactions would serve to stabilize and rigidify D1 in the open, functional conformation (Fig. 5a) as suggested by the interactions between D1full with other domains in D1-5 full-length intron structure. Specifically, we know that D2 interacts with D1 stems i1 and c through coaxial stacking and a tetraloop-receptor interaction (Fig. 5b). As a result of these contacts, the relative positions of stems i1 and c become fixed in space and motions of the 5′H hinge region are restricted. D2 therefore is likely to act as a brace that defines specific orientations for the i1 and c helices of D1 (Fig. 5b). D3 is likely to further stabilize the open D1 conformation by interacting with both D1 and D2 (Fig. 5b). Thus, the D1-5 structure suggests that the sequential addition of D2 and D3 traps D1 in the open state and limits the conformations that D4 and D5 have to sample to enter and dock into the intron core (Supplementary Movie 1).

Figure 5.

Group II intron folding assembly pathway. (a) The schematic for group II intron assembly. The D1iso, D1full, D2, D3 and D5 are shown in yellow, gray, cyan, green and red. (b) Interface between D1full (gray), D2 (cyan) and D3 (green) in the full-length intron. D2 interacts with D1full through coaxial stacking and tetraloop-receptor interactions. D3 interacts with D1 and D2 through A-minor interaction, base stacking and ribose zipper.

The final stage of intron assembly occurs when D5 inserts into the cup-like structure that is formed by the open D1 conformation (Supplementary Movie 1). Specific D5 receptors are located inside this D1 scaffold, and these can be classified into two groups. One group involves nucleotides within the κ junction, which adopts a native-like conformation in D1iso (Supplementary Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 6b). Similarity of the κ junction in both D1iso and D1full suggests that this region may interact with D5 through a lock-and-key mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 6b), guiding D5 into position within the D1 cavity (Fig. 1c). The other set of receptors involve the ζ and λ nucleotides, which are located deep within the D1 cavity. The fact that these are disordered in D1iso (Supplementary Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. 7b) suggests that the ζ–ζ′ and λ–λ′ interactions between D1 and D5 involve induced-fit. These observations are consistent with a model in which κ-κ′ fixes the D5 stem at the entrance of the D1 cavity, enabling the rest of D5 to sample the cavity interior and engage the ζ–ζ′ and λ–λ′ interactions. Importantly, all D1 nucleotides that ultimately interact with D5 (κ, ζ and λ) are unbound in D1iso and await interaction with D5 avoiding alternative interactions with non-native partners. In this way, D5 docking is fast and favorable4,5, requiring no rearrangement of interaction networks within D1.

It is important to note that this folding model, while consistent with years of biochemical analysis on the individual intron domains4,20,21,31,32, is inferred through a comparison of the D1iso and D1-5 crystal structures14,15. A direct kinetic analysis of D2 and D3 docking remains an important area of continued investigation.

Discussion

Here we present the first crystal structure of an obligate RNA folding intermediate. To our knowledge, there are only two other RNAs for which the full-length and individual domain structures have been solved: the P456 domain of the Tetrahymena group I intron13,29,30 and the specificity domain of type-A RNase P12,33,34. However, the folding pathways of these two ribozymes involve non-native interactions2,5,35, neither pathway involve structurally-discrete obligate intermediates, and in neither structure does the individual domain template the full-length structure. The group II intron D1 structure is therefore significant because it reveals, for the first time, the physical attributes of a productive RNA folding intermediate and thereby provides insights into the forces that drive a productive folding pathway.

We observe that the D1 intermediate adopts a native-like, but closed conformation. Previous studies of group II intron ai5γ showed that D1 and D135 form compact structures at the same rate and at the same Mg2+ concentration, suggesting that D1 is likely to be a stable, autonomous folding domain4. However, subsequent crystal structures of the full-length intron15,19 revealed that D1 is composed of two “halves”, which tightly clamp catalytic D5 (Fig. 1d and Fig. 5a). These structural observations suggested that the D1 scaffold might be greatly influenced by its contacts with catalytic core domains, which was puzzling for the following reasons. On the one hand, it was difficult to imagine how D1 could be stable enough to hold an open conformation in the absence of interactions from the other domains. On the other hand, if D1 was to adopt a closed conformation before binding of D2-D6, it was equally difficult to understand how it could rapidly transit to the open state and facilitate precise and fast association of D52. Our crystal structure of D1iso and the pseudotorsion angle analysis of its hinge regions now explain this paradox, showing how D1 can fold efficiently and then flex to accommodate binding of the catalytic domain.

The crystal structure of D1iso reveals the specific structural features that enable D1 to function as an on-pathway RNA folding intermediate. First, D1 contains internal loops with sufficient flexibility to function as hinges, allowing rotational movement between adjacent stems. This flexibility allows D1iso to adopt a closed conformation as in the crystal structure. In solution, it is likely that the peripheral end of stem c can stochastically sample a range of angles, enabling D1 to toggle between the closed and open states36,37. There are no major differences in hydrogen bonding or stacking interactions in the two states, suggesting that sampling is energetically inexpensive and can allow fast response to the presence of docking partners such as D5. Second, D1 contains an exceptionally rigid five-way junction at its center. As noted for some other RNA junctions36,38, this five-way junction determines the relative orientation for each of the central stems (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1a), setting the stage for appropriate disposition of tertiary interaction partners and reducing the conformational search space for native partners. Indeed, D1iso confirms biochemical and computational observations that attributed to junctions a primary role in facilitating RNA folding5,39,40. Third, the apparent stability of the κ region, which is almost identical in D1iso and D1full (Supplementary Fig. 6a), is critical because it provides the scaffolding for the entire 3′H, and facilitates presentation of EBS1 to the 5′exon by maintaining the long-range interaction α-α′. Stabilization of the κ conformation is probably supported by long-range interactions involving A137 and A138 (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Fourth and last, nucleotides which form tight interactions with D5, including ζ and λ, do not form alternative interactions within the D1 intermediate, where they are simply disordered. The fact that these receptor nucleotides do not engage in strong intermediate interactions may eliminate the need for energetically costly rearrangements and help facilitate a rapid folding process. In summary, both rigid and flexible regions of the RNA molecule work together, enabling D1iso to coordinate the efficient, accurate assembly of a much larger RNA molecule.

The structure of D1iso provides new physical insights into RNA folding strategies that are coordinated with transcription, since D1 is the first section of the intron that is synthesized. The importance of co-transcriptional RNA folding has been proposed in various contexts and it is a concept that is increasingly appreciated41. Consistent with the importance of co-transcriptional folding, our native purification strategy contributes strongly to the homogeneity of the large RNA molecules we have investigated15,42,43. Indeed the RNA samples we have used for crystallization are prepared by native purification. The D1 crystal structure captures a snapshot along a “first comes, first folds” folding pathway, and reveals how the sequential addition of domains onto a pre-assembled template can guarantee the formation of a functionally active molecule, thus ensuring high fidelity in folding.

The folding pathway described here is not without precedent, as similar mechanisms have been reported in classical examples of protein folding6–8. Investigations of myoglobin44, thioredoxin45, T4 lysozyme46, trp repressor47 and horse heart cytochrome c47, all involve formation of native-like intermediates that serves as templates for faithful assembly of a full-length structure. The pathway reported here is partly exemplified by the folding of myoglobin, which assembles through an on-pathway, native-like intermediate in which a single subdomain forms stable secondary and tertiary structure during the earliest stages of the folding process44,48. During subsequent phases of myoglobin assembly, additional α-helices dock sequentially onto the pre-folded subdomain48. Importantly, the protein cases do not necessarily involve a native-like intermediate that is localized at the N-terminus, and therefore they do not necessarily follow a “first comes, first folds” strategy. It is likely that on-pathway, template intermediates are utilized in both RNA and protein folding, but the way in which they contribute to macromolecular assembly is likely to be context-dependent.

Finally, the crystal contacts within the D1iso lattice are mediated by an unusual motif that is potentially useful for RNA nanotechnology and design. Within the crystal, individual molecules pack against each other through interactions along the unit cell c axis (Supplementary Fig. 8). These are mediated by symmetric tetraloop/receptor interactions and adjacent helices that are formed from palindromic sticky ends that result from preparation of the linearized plasmid template (On-line methods and Supplementary Fig. 8). The combined receptor/duplex motif results in an extended, highly symmetric self-assembly module. RNA and DNA self-assembly is becoming an important area for nanotechnology design, and many motifs have been utilized including kissing loops, tetraloop/receptor interactions49,50. By comparison with existing assembly motifs, the combination of an inter-molecular double helix and symmetric tetraloop/receptor interaction is likely to provide higher affinity and specificity.

In summary, D1iso adopts a compressed, native-like structure that is stabilized by a network of rigid junctions and connecting units. This structure can readily rearrange to the functional native form through the coordinated action of molecular hinges. This conformational rearrangement does not disrupt stacking or bonding networks and is therefore likely to be energetically inexpensive. The open conformation of D1, which is necessary for D5 binding, is rigidified through sequential interactions between D1 and downstream domains, which work together to facilitate a direct, accurate pathway for intron assembly. Given the abundance of large, multidomain RNA molecules in nature and our increasing awareness of their importance, studies of group II intron assembly provide tools and concepts that enrich our physical understanding of the emerging RNA universe.

On-line Methods

Construct description

The DNA template for D1iso is composed of residues 1-266 from the Ocenanobacillus iheyensis (O.i.) group II intron14, joined with a short 5′-exon sequence (5′UUAU3′). The sequence spanning residues 1-265 in the full-length intron was cloned into a plasmid immediately followed by a BamHI restriction site (GGATCC), so that the first residue of the restriction site serves as G266 in the RNA template. To facilitate crystal contacts, the tetraloop GCGA (90-93) was mutated to GAAA. The 5′-exon and the tetraloop mutations were introduced by Quikchange™ site-directed mutagenesis.

The following constructs were used in the RNA folding assay: 1) 5′exon-D1, which contains the wild-type D1 joined to its 5′-exon (the same as D1iso but without the mutations at residues 90-93), 2) 5′exon-D1 (crystallization): the crystallization construction for O.i. D1, i.e. D1iso. 3) 5′exon-D1-5: the crystallization construct for the D1-5 intron14 containing the wild-type D1 joined to its 5′-exon.

RNA purification and crystallization

The DNA template for in vitro transcription was prepared by BamHI digestion overnight at 37°C. The RNA was transcribed in vitro using T7 polymerase and was natively purified as previously described14 with minor modifications. Instead of using a 100 kDa concentrator for buffer exchange, we used 50 kDa concentrator because the molecular weight of D1 is about 88 kDa. Before crystallization, the RNA was concentrated to 80 μM in 5 mM Na-Cacodylate (pH 6.5) and 10 mM MgCl2 (buffer A). The RNA was then diluted by a 1:1 volume ratio with 0.5 mM spermine (in H2O).

The crystallization drop was set up with 1.4 μL of the above RNA-spermine solution and 0.7 μL reservoir solution containing 80 mM NaCl, 24 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 40 mM Na-Cacodylate (pH 7.0), 17% MPD, 8 mM spermine-4HCl (buffer B) using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method at 25 °C. The crystals were harvested 4 days after setting up the drops. When harvesting, 20 μL cryo-protectant containing 80 mM NaCl, 24 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 40 mM Na-Cacodylate (pH 7.0), 17% MPD, 8 mM spermine-4HCl and 30% EG (buffer C) was slowly pipetted into the drops containing crystals. The crystals were then mounted in nylon loops and directly frozen under cold N2(l) stream. For Ir(NH3)63+ derivatives, similar procedures were followed as for the native crystals, except that 5 mM Ir(NH3)6Cl3 (Obiter Research) was added to the cryo-protectant.

Data collection and structure determination

Diffraction data were collected at beamline 24ID-C (NE-CAT) at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne, IL. The data collection strategy and preliminary data processing were done by Rapid Automated Processing of Data (RAPD) software package (https://rapd.nec.aps.anl.gov/rapd/). The final indexing, integration and scaling were done by XDS51 and converted to CCP4 format using POINTLESS followed by AIMLESS in CCP4 suite52. Molecular replacement (MR) using either complete or fragmented D1 from the full-length intron (D1full) as the search model was initially attempted but failed to produce an interpretable electron density map. The structure was finally solved by single wavelength anomalous dispersion (SAD) using Ir(NH3)63+ derivative data, employing a combination of SHELXC/D/E53 and Phaser-EP in PHENIX54. In particular, 10 Ir(NH3)63+ sites were found by SHELXC/D/E, and a total of 52 Ir(NH3)63+ sites including those minor sites with low occupancies were found by Phaser-EP. The density modification was done by RESOLVE in PHENIX with NCS averaging. Although D1full failed to serve as an effective searching model in MR, we were able to place D1full onto the experimental electron density map using MOLREP, and this model was useful for finding the NCS operations. The model was then manually adjusted for regions that did not fit the electron density. The model was first refined with isotropic B-factors for individual atoms using phenix.refine. The Ir(NH3)63+ sites were added after Rfree was less than 30%, guided by the anomalous difference Fourier map. After the convergence of refinement, translation/libration/screw (TLS) combined with isotropic B-factor refinement by phenix.refine was carried out. The TLS groups were identified automatically by phenix.refine. At all stages, the occupancy of the 5′-exon and exon binding site 1 (EBS1), and the f′ and f″ for Ir(NH3)63+ were also subject to refinement.

The model built from the Ir(NH3)63+-SAD data was used as the starting model for refinement of the native dataset that is isomorphous to the Ir(NH3)63+ derivative dataset. The solvent atoms, including the Ir(NH3)63+ sites were removed before refinement. Initially five cycles of rigid body refinement were carried out, treating two molecules as two rigid bodies, using phenix.refine software. Subsequently, the native model was refined in the same way as the derivative structure except that the parameters for Ir(NH3)63+ were not included.

All models have been processed with phenix.erraser to correct potential problematic residues. The riding hydrogens from the phenix.erraser output models were removed and the models were subjected to one more cycle of refinement by phenix.refine to produce PDB files with the correct refinement headers. All the real-space model building and adjustment was done by COOT55 and RCrane25,56.

All crystallographic statistics in Supplementary Table 1 was calculated by phenix.table_one54 except for Rpim, which was reported by AIMLESS52. To decide on the resolution cutoff, we considered three data quality indicators, <I/σ(I)>, Rpim and CC1/2. Using traditional resolution cutoff criteria, where <I/σ(I)> is about 2 and Rpim is about 60 %57, the resolution for the derivative dataset would be 3.05 Å (<I/σ(I)> in the highest resolution shell = 2.22) and the resolution for the native dataset would be 3.0 Å (<I/σ(I)> in the highest resolution shell = 2.43). However, new CC1/2-based resolution cutoff criteria have recently been validated and are being widely used57. By these criteria, the resolution for both data sets should be extended to 2.85 Å; in the highest resolution shell, <I/σ(I)> = 0.64 and CC1/2 = 0.29 for the derivative data set and <I/σ(I)> = 0.66 and CC1/2 = 0.37 for the native data set. Both data sets are complete to 2.85 Å. Nevertheless, we took a conservative approach and reported the derivative data set as 3.0 Å and the native data set as 2.95 Å in Supplementary Table 1.

Overall structural analysis

The isolated D1 structure (D1iso) used for structural analysis is the chain A from the native structure (PDBID:4Y1O). The structure of D1 in the full-length intron (D1full) contains residues -3-266 from the D1-5 structure published previously (PDBID: 4FAQ)14. All structure alignment was done by LSQ (Least-Squares Fitting) superpose in COOT55. All of the root mean square deviation (RMSD) values were calculated by Pymol without allowing removal of non-fitting residues to minimize RMSD. For calculating the simulated annealing omit map, the region of interest was first deleted from the model, and then this partial model was subject to simulated annealing refinement in phenix.refine. All figures containing the models and maps were prepared using Pymol.

Movie preparation

The movie for the structural transition between D1iso and D1full was generated using the Morphing server58. Because the server requires input structures to have exactly the same sequence, the residues that were not modeled in D1iso were filled in manually using COOT55. Steric clashes were first corrected by COOT and RCrane25,56, and the resulting models were fed into phenix.erraser for further polishing. The movie was compiled by Pymol through eMovie plugin. In the movie, the manually added residues were masked to avoid confusion. The 5′-exon was also removed in order to better view the relative size of the D1 cavity.

B-factor analysis

For the B-factor analysis of D1iso, the density plot of the B-factors from D1iso (Fig. 2a) was generated using statistical programming language R. The three dimensional D1iso model, color-coded by atomic B-factor, was generated in Pymol. The secondary structure map (Fig. 2c) was color-coded by the average B-factor of each residue, following the same color-code spectrum for the three dimensional model. Nucleotides involved in crystal contacts, including the terminus of stem i1, the tetraloop θ in stem c and the T-loop in stem a (Fig. 2c), were not considered to be residues important for maintaining the native-like conformation of D1, despite of their low B-factor values.

In order to conduct the B-factor analysis for all RNA structure entries in the protein data bank (PDB), all RNA-only structures (577 in total, up to October, 2014) solved by X-ray crystallography in the PDB were first processed by 3DNA-dssr59 to extract RNA structural elements including junctions, stems, hairpins and bulges. Only 231 out of the 577 RNA structures contain junctions. After removing the RNA structures that were refined with a single overall B-factor, 226 structures with junctions were finally subjected to B-factor analysis. The average B-factors were extracted from each PDB file using a simple home-built script (available upon request) and were normalized to a range of 1–100 using the following equation (equation (1))60:

| (1) |

The difference average B-factors (ΔB̄, see below in equation (2)) are the difference between the normalized average B factors from RNA junction residues (226 structures) and from other RNA structural elements (all residues, stem, hairpin and bulge) for each RNA structure, denoted as ΔB(junction, overall), ΔB(junction, stem), ΔB(junction, hairpin) and ΔB(junction, bulge). All the 226 structures participate in the calculation of ΔB(junction, overall) and ΔB(junction, stem). Because 3DNA-dssr could find hairpin and bulge in only 224 and 100 structures, only 224 and 100 structures participate in the calculation of ΔB(junction, hairpin) and ΔB(junction, bulge) respectively.

| (2) |

The box plot showing the result of B-factor analysis of all RNA structures in the PDB was produced using statistical programming language R (Fig. 3).

Pseudo-torsion angle analysis

Pseudo-torsion angles η and θ are defined as the C4′ (i-1)-P (i)-C4′ (i)-P (i+1) and P (i)-C4′ (i)-P (i+1)-C4′ (i+1) dihedral angles as previously described25,26. The pseudo-torsion angles for the following molecules were calculated with 3DNA-dssr59: 1) Chain A in D1iso (PDBID:4Y1O), 2) D1 in the full-length structure (residue -3-266 in 4FAQ). Individual pseudo-torsion angle differences Δη and Δθ for each residue i were obtained by directly substracting the pseudo-torsion angles in 1) from pseudo-torsion angles in 2), which were then converted into the range of (−180°,180°] according to equations (3)–(4)26:

| (3) |

| (4) |

The overall pseudo-torsion angle difference Δ(η, θ) is the Euclidean distance obtained from the Δη and Δθ values of each residue (equation (5))26:

| (5) |

The procedure of calculating the difference pseudo-torsion angles is briefly summarized in Fig. 3a. Δ(ηi, θi) values were then clustered to two groups (large and small) based on the Jenks natural breaks optimization method in statistical programming language R. This two-group clustering explains 76% variance in all Δ(ηi, θi) values from D1. The plot showing the Δ(ηi, θi) values for each residue was produced with statistical programming language R (Fig. 3b). A similar procedure was followed to calculate the Δ(η, θ) values between the isolated P456 domain (PDBID:1HR2)30 and the P456 domain within the P456:P379 construct from the intact Tetrahymena thermophile group I intron (PDBID:1X8W)29 (Supplementary Fig. 5). The two-group clustering explains 87% variance from all Δ(ηi, θi) values of P456 domain.

RNA folding assay

The RNA folding assay was designed to compare the Mg2+ dependency for global compaction of 5′exon-D1 and 5′exon-D1-5 RNA constructs with minimal modification to the native purification method that was used for crystallization. Therefore, the 5′exon-D1 and 5′exon-D1-5 RNA constructs were body-labeled by α-UT32P and were natively purified as for crystallization with a minor modification. Instead of changing to buffer A, the RNA buffer was exchanged to 5 mM K-MOPS (pH 6.5), 150 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA (buffer D) to unfold the RNA without destroying its secondary structure. The following RNA folding procedure was adapted from previous work4,43. After buffer exchange, for each RNA construct, the RNA was diluted to 50 nM with buffer D. The 50 nM RNA stock was further diluted to 6.25 nM with a buffer containing 50 mM K-HEPES (pH 7.5) and 187.5 mM KCl (buffer F). The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 1 hour, which was then aliquoted into MgCl2 stock (pre-warmed at 37°C briefly) to a final concentration of 5 nM RNA, 40 mM K-HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM KCl and one of the following MgCl2 concentrations: 0, 0.1 mM, 0.15 mM, 0.3 mM, 0.5 mM, 0.8 mM, 1 mM, 1.4 mM, 3 mM, 4 mM, 5 mM, 10 mM. Then the RNA was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes and mixed with pre-warmed loading buffer containing 40% (w/v) sucrose, 0.2% (w/v) xylene cyanol and bromophenol blue, 150 mM KCl and corresponding MgCl2 concentrations. The samples were immediately loaded onto 8% poly-acrylamide gels (acrylamide:bis-acrylamide=29:1) containing 34 mM Tris base, 66 mM HEPES, 15 mM KCl and 2.5 mM MgCl2 (buffer G). Buffer G was also used as the gel running buffer. The gel was run at 4°C for 7 hours. This procedure was repeated 3 times with the same RNA transcript in independent folding experiments (the MgCl2 stock solutions were also diluted independently). All gel quantification analysis was done using the one-dimensional gel quantification software Quantity One® from BioRad.

Because the two constructs have different background compaction levels at zero Mg2+ (0.48 for 5′exon-D1 (crystallization), 0.33 for 5′exon-D1 and 0.12 for 5′exon-D1-5), the folded fraction was normalized based on the following equation (equation (6)):

| (6) |

where y represents the folded RNA fraction, y0 represents the folded RNA fraction when the Mg2+ concentration is zero. A value of one represents the maximum folded RNA fraction. The normalized folded fraction was fit to the Hill equation (equation (7)):

| (7) |

where ynormalized represents the folded RNA fraction after normalization, [Mg]2+ represents the Mg2+ concentration, KMg represents the dissociation constant between Mg2+ and RNA, and h represents Hill coefficient associated with the interactions between Mg2+ and RNA.

The data analysis and figure generation (Supplementary Fig. 2) were done by scientific curve fitting and graphing software GraphPad prism version 6.03 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, www.graphpad.com.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Srinivas Somarowthu for constructive discussions, and Dr. Olga Fedorova, Dr. Srinivas Somarowthu and Dr. Thayne Dickey for reading the manuscript. C.Z. is supported by Gruber Science Fellowship. A.M.P. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator. This work is supported by the National Institute of Health (RO1GM50313) and is based upon research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which are funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P41 GM103403). The Pilatus 6M detector on 24-ID-C beam line is funded by a NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10 RR029205). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

Accession codes:

The Ir(NH3)63+ derivative structure is deposited under the accession number 4Y1N and the native structure is deposited under the accession number 4Y1O in the PDB.

Contributions:

C.Z. designed the constructs and conducted all the experiments, C.Z., K.R.R. and M.M. collected X-ray diffraction data, C.Z., K.R.R. and M.M. solved the structure. C.Z. analyzed the structure. A.M.P and M.M. directed the research. A.M.P and C.Z. wrote the manuscript, and M.M. and K.R.R. contributed to writing.

Competing financial interests:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Treiber DK, Williamson JR. Beyond kinetic traps in RNA folding. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2001;11:309–314. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodson SA. Recent insights on RNA folding mechanisms from catalytic RNA. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2000;57:796–808. doi: 10.1007/s000180050042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sosnick TR, Pan T. RNA folding: models and perspectives. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:309–16. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su LJ, Waldsich C, Pyle AM. An obligate intermediate along the slow folding pathway of a group II intron ribozyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6674–87. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodson SA. Compact intermediates in RNA folding. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:61–77. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryngelson JD, Onuchic JN, Socci ND, Wolynes PG. Funnels, pathways, and the energy landscape of protein folding: a synthesis. Proteins. 1995;21:167–95. doi: 10.1002/prot.340210302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim PS, Baldwin RL. Intermediates in the folding reactions of small proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:631–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Peptide Conformation and Protein-Folding. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 1993;3:60–65. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pyle AM. The tertiary structure of group II introns: implications for biological function and evolution. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;45:215–32. doi: 10.3109/10409231003796523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pyle AM, Lambowitz AM. Group II Introns: Ribozymes That Splice RNA and Invade DNA. In: Gesteland RF, editor. The RNA World. 3. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 2006. pp. 469–505. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pyle AM, Fedorova O, Waldsich C. Folding of group II introns: a model system for large, multidomain RNAs? Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krasilnikov AS, Xiao Y, Pan T, Mondragon A. Basis for structural diversity in homologous RNAs. Science. 2004;306:104–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1101489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cate JH, et al. Crystal structure of a group I ribozyme domain: principles of RNA packing. Science. 1996;273:1678–85. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcia M, Pyle AM. Visualizing group II intron catalysis through the stages of splicing. Cell. 2012;151:497–507. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toor N, Keating KS, Taylor SD, Pyle AM. Crystal structure of a self-spliced group II intron. Science. 2008;320:77–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1153803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coonrod LA, Lohman JR, Berglund JA. Utilizing the GAAA tetraloop/receptor to facilitate crystal packing and determination of the structure of a CUG RNA helix. Biochemistry. 2012;51:8330–7. doi: 10.1021/bi300829w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcia M, et al. Solving nucleic acid structures by molecular replacement: examples from group II intron studies. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2013;69:2174–85. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913013218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson MP, Scott WG. A general method for phasing novel complex RNA crystal structures without heavy-atom derivatives. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2008;D64:738–44. doi: 10.1107/S0907444908011578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcia M, Pyle AM. Principles of ion recognition in RNA: insights from the group II intron structures. RNA. 2014;20:516–27. doi: 10.1261/rna.043414.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qin PZ, Pyle AM. Stopped-flow fluorescence spectroscopy of a group II intron ribozyme reveals that domain 1 is an independent folding unit with a requirement for specific Mg2+ ions in the tertiary structure. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4718–30. doi: 10.1021/bi962665c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michels WJ, Jr, Pyle AM. Conversion of a group II intron into a new multiple-turnover ribozyme that selectively cleaves oligonucleotides: elucidation of reaction mechanism and structure/function relationships. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2965–77. doi: 10.1021/bi00009a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drenth J. Principles of Protein X-Ray Crystallography. Springer; 2007. Theory of X-ray diffraction by a crystal; pp. 81–82. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohan S, Donohue JP, Noller HF. Molecular mechanics of 30S subunit head rotation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:13325–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413731111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toor N, et al. Tertiary architecture of the Oceanobacillus iheyensis group II intron. RNA. 2010;16:57–69. doi: 10.1261/rna.1844010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keating KS, Humphris EL, Pyle AM. A new way to see RNA. Q Rev Biophys. 2011;44:433–66. doi: 10.1017/S0033583511000059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duarte CM, Wadley LM, Pyle AM. RNA structure comparison, motif search and discovery using a reduced representation of RNA conformational space. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4755–61. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duarte CM, Pyle AM. Stepping through an RNA structure: A novel approach to conformational analysis. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:1465–78. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fedorova O, Pyle AM. The brace for a growing scaffold: Mss116 protein promotes RNA folding by stabilizing an early assembly intermediate. J Mol Biol. 2012;422:347–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo F, Gooding AR, Cech TR. Structure of the Tetrahymena ribozyme: base triple sandwich and metal ion at the active site. Mol Cell. 2004;16:351–62. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juneau K, Podell E, Harrington DJ, Cech TR. Structural basis of the enhanced stability of a mutant ribozyme domain and a detailed view of RNA--solvent interactions. Structure. 2001;9:221–31. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00579-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Waldsich C, Pyle AM. A kinetic intermediate that regulates proper folding of a group II intron RNA. J Mol Biol. 2008;375:572–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Konforti BB, Liu Q, Pyle AM. A map of the binding site for catalytic domain 5 in the core of a group II intron ribozyme. EMBO J. 1998;17:7105–17. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torres-Larios A, Swinger KK, Krasilnikov AS, Pan T, Mondragon A. Crystal structure of the RNA component of bacterial ribonuclease P. Nature. 2005;437:584–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baird NJ, Westhof E, Qin H, Pan T, Sosnick TR. Structure of a folding intermediate reveals the interplay between core and peripheral elements in RNA folding. J Mol Biol. 2005;352:712–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan T. Folding of Bacterial RNase P RNA. In: Ribonuclease P, Liu F, Altman S, editors. Protein Reviews. Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bailor MH, Mustoe AM, Brooks CL, 3rd, Al-Hashimi HM. Topological constraints: using RNA secondary structure to model 3D conformation, folding pathways, and dynamic adaptation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2011;21:296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailor MH, Sun X, Al-Hashimi HM. Topology links RNA secondary structure with global conformation, dynamics, and adaptation. Science. 2010;327:202–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1181085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu VB, et al. Do conformational biases of simple helical junctions influence RNA folding stability and specificity? RNA. 2009;15:2195–205. doi: 10.1261/rna.1747509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Behrouzi R, Roh JH, Kilburn D, Briber RM, Woodson SA. Cooperative tertiary interaction network guides RNA folding. Cell. 2012;149:348–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson TH, Tijerina P, Chadee AB, Herschlag D, Russell R. Structural specificity conferred by a group I RNA peripheral element. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:10176–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501498102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan T, Sosnick T. RNA folding during transcription. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:161–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Somarowthu S, et al. HOTAIR Forms an Intricate and Modular Secondary Structure. Mol Cell. 2015;58:353–61. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chillon I, et al. Native Purification and Analysis of Long RNAs. In: Woodson SA, Allain F, editors. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 558. Academic Press; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hughson FM, Wright PE, Baldwin RL. Structural characterization of a partly folded apomyoglobin intermediate. Science. 1990;249:1544–8. doi: 10.1126/science.2218495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhutani N, Udgaonkar JB. Folding subdomains of thioredoxin characterized by native-state hydrogen exchange. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1719–31. doi: 10.1110/ps.0239503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Llinas M, Marqusee S. Subdomain interactions as a determinant in the folding and stability of T4 lysozyme. Protein Sci. 1998;7:96–104. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu LC, Grandori R, Carey J. Autonomous subdomains in protein folding. Protein Sci. 1994;3:369–71. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uzawa T, et al. Hierarchical folding mechanism of apomyoglobin revealed by ultra-fast H/D exchange coupled with 2D NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13859–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804033105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chworos A, et al. Building programmable jigsaw puzzles with RNA. Science. 2004;306:2068–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1104686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Han D, et al. DNA origami with complex curvatures in three-dimensional space. Science. 2011;332:342–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1202998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winn MD, et al. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–42. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheldrick GM. Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E: combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2010;66:479–485. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909038360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Biological Crystallography. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–32. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keating KS, Pyle AM. RCrane: semi-automated RNA model building. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:985–95. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912018549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karplus PA, Diederichs K. Assessing and maximizing data quality in macromolecular crystallography. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;34:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krebs WG, Gerstein M. The morph server: a standardized system for analyzing and visualizing macromolecular motions in a database framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1665–75. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.8.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu XJ, Olson WK. 3DNA: a software package for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5108–21. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schneider B, Gelly JC, de Brevern AG, Cerny J. Local dynamics of proteins and DNA evaluated from crystallographic B factors. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2014;70:2413–9. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714014631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.