Abstract

Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) is currently the world’s highest production volume brominated flame retardant. Humans are frequently exposed to TBBPA by the dermal route. In the present study, a parallelogram approach was used to make predictions of internal dose in exposed humans. Human and rat skin samples received 100 nmol of TBBPA/cm2 skin and absorption and penetrance were determined using a flow-through in vitro system. TBBPA-derived [14C]-radioactivity was determined at 6 hour intervals in the media and at 24 hours post-dosing in the skin. The human skin and media contained an average of 3.4% and 0.2% of the total dose at the terminal time point, respectively, while the rat skin and media contained 9.3% and 3.5%, respectively. In the intact rat, 14% of a dermally-administered dose of ~100 nmol/cm2 remained in the skin at the dosing site, with an additional 8% reaching systemic circulation by 24 hours post-dosing. Relative absorption and penetrance was less (10% total) at 24 hours following dermal administration of a ten-fold higher dose (~1,000 nmol/cm2) to rats. However, by 72 hours, 70% of this dose was either absorbed into the dosing-site skin or had reached systemic circulation. It is clear from these results that TBBPA can be absorbed by the skin and dermal contact with TBBPA may represent a small but important route of exposure. Together, these in vitro data in human and rat skin and in vivo data from rats may be used to predict TBBPA absorption in humans following dermal exposure. Based on this parallelogram calculation, up to 6% of dermally applied TBBPA may be bioavailable to humans exposed to TBBPA.

Keywords: dermal bioavailability, brominated flame retardant, Tetrabromobisphenol A, parallelogram method, persistent organic pollutant

Introduction

Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA), the world’s highest production volume brominated flame retardant (BFR) is used primarily in resins of electronic circuit boards via reactive chemical incorporation (1). Non-reactive use of TBBPA as an additive in consumer products may increase as a result of the phase out of polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDEs) flame retardant mixtures (2). Additive use of TBBPA results in greater potential for leaching from products into the environment (3). TBBPA has been identified in occupational, household and environmental dust samples, thus posing a potential risk from dermal, oral, and inhalation exposures, especially among children via hand-to-mouth contact (4, 5). In a two-year oral bioassay by the National Toxicology Program (NTP), TBBPA was shown to induce the formation of highly malignant uterine tumors in Wistar Han rats (6). TBBPA exposures elicited decreased rat serum thyroxine levels in our laboratory (7), in the NTP study (6, 8), and in both a one-generational (9), and two-generational study (10). TBBPA alters the expression of efflux transporters in liver (11, 12), but is not a substrate for these transporters (13). One previous study of human TBBPA in vitro dermal uptake commissioned for Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) listing with the European Union concluded that less than 2% of a 2 mg/cm2 dose of TBBPA was bioavailable, with 0.73% of the dose penetrating the skin and 0.9% of the dose remaining in the skin 24 h after dosing (14).

Previous work has characterized the bioavailability of TBBPA in rodent models to support risk assessment following oral exposure to humans (15–17). The present work provides data to support assessment of risk of dermal exposure of TBBPA to humans. Here, the parallelogram approach (18, 19) has been used to characterize and compare the extent of dermal absorption and penetrance of TBBPA in vivo in rats and in vitro in rat and human skin for prediction of internal dose to humans following dermal exposure to TBBPA.

In vivo studies were conducted using female Wistar Han rats and in vitro studies were conducted using split-thickness skin (e.g., epidermis and upper portion of the dermis) from human donors and female Wistar Han rats exposed to TBBPA in a flow-through system as described below. For the in vitro experiments, the term ‘absorbed’ is used to describe the portion of the applied dose found within the skin and ‘penetrated’ is used to describe chemical that has completely diffused through the skin into the underlying fluid (termed ‘receptor fluid’, analogous to the amount reaching systemic circulation following in vivo exposure) (20). The values for absorption and penetration are combined for an estimation of bioavailability of TBBPA.

Methods & Materials

Chemicals

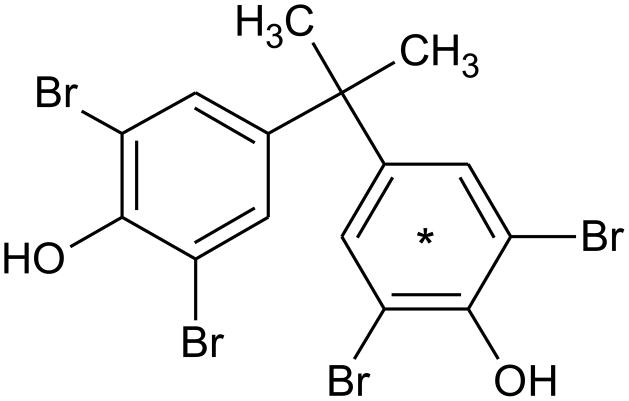

[14C]-labeled TBBPA (ring-labeled; Figure 1, Lot # 3225-235, Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences [Boston, MA], re-purified in 2013 by Moravek Biochemicals [Brea, CA]) used in these studies had a radiochemical purity of >98% (specific activity = 90.3 mCi/mmol) and a chemical purity of >98%, as compared to a TBBPA reference standard (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO). Scintillation cocktails were obtained from MP Biomedicals (Ecolume; Santa Ana, CA), Perkin-Elmer (Ultima Gold & PermaFluor E+; Torrance, CA), or Lablogic Inc., (Flow Logic U; Brandon, FL). All other reagents used in these studies were high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or analytical grade.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of TBBPA, asterisk indicates the location of the radiolabel.

In vitro skin samples

Full-thickness human skin was obtained from the National Disease Research Interchange, (Philadelphia, PA, USA) from three (1 male, 2 female) Caucasian individuals aged 71–77 years old (dorsal/scapular skin, excised ≤ 12 h post-mortem, shipped at 80 °C). The skin was shipped and stored frozen (−80°C) until use. Full-thickness female Wistar Han rat skin (N=4, 10–11 weeks old) was obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC). Twenty-four hours prior to excision, hair on the dorsal surface was clipped; the day of shipment, the rats were humanely euthanized by CO2 inhalation and skin excised. The skin was shipped on dry ice and stored frozen (−80°C) until use. In vitro dermal absorption tests were conducted according to the OECD Test Guideline 428 (21). Human skin was sampled in quadruplicate while rat skin was sampled in triplicate.

In vitro dermal absorption apparatus

A flow-through diffusion cell system (Crown Bio Scientific, Inc., Somerville, NJ, USA) and methodology as described by Bronaugh and Stewart (22) and Bronaugh and Maibach (23) were used. Teflon Flo-Thru diffusion cells with a diffusional area of 0.64 cm2 were used. Each cell was placed in a PosiBloc Diffusion Cell Heater, heated by circulating water at a temperature of 35°C. A peristaltic pump was used to pump receptor fluid at a rate of 1.8 ml/h from a reservoir through Tygon tubing (R-3603, Fisher Scientific Co., Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) to the flow-through cells. Scintillation vials (20 ml) were placed in a fraction collector to collect the receptor fluid. All components of the diffusional apparatus were sterilized with 70% ethanol solution and rinsed with sterile receptor solution before placing the skin samples in the flow-through cells.

Receptor fluid

HEPES-buffered Hanks’ balanced salt solution, pH 7.4, with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), was used as the receptor fluid. This fluid has been shown by Collier et al. (24) to maintain the viability of rat skin for up to 24 h. Components of the fluid were N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES), fetal bovine serum, and gentamicin sulfate, obtained from GIBCO (Grand Island, NY, USA), and disodium hydrogen phosphate and potassium dihydrogen phosphate, purchased from Scientific Products (McGraw Park, IL, USA) and Matheson Coleman and Bell (Norwood, OH, USA), respectively. The receptor fluid was prepared with distilled water and sterilized by filtration (0.2 μm filter, Nalgene disposable filterware, Sybron Corp., Rochester, NY, USA). A 10% solution (v/v) of fetal bovine serum was prepared with the sterile receptor fluid. The receptor fluid was continuously gassed with 100% oxygen throughout the experiment.

In vitro procedures

Human and rat skin experiments were run on separate days. On the day of the experiment, human or rat skin was thawed and dermatomed to approx. 300 μm thicknesses using a Padgett dermatome (Kansas City, MO, USA) and placed in receptor fluid. Four discs were cut from each sample of human skin and 3 from each rat skin with a 0.75-inch diameter bow punch. The thickness of each skin disc was measured along its edge with microcalipers (Model D-1000, The Dyer Co., Lancaster, PA, USA). The mean (± SD) skin thickness of human and rat skin was 294 (± 57) and 244 (± 25) μm, respectively. The discs were mounted epidermal side up in the flow-through system (described above). Once all of the skin discs were mounted, the receptor fluid pump was started. Each skin disc was rinsed with a small volume of distilled water and dried with Kim Wipe® paper three times prior to TBBPA application.

After an equilibration period of 30 min, the integrity of the human skin was tested as follows: [3H]-H2O (1 μCi, 100 μl), obtained from Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA, USA), was applied to the skin with a Pipetman, the pump turned on, and the receptor fluid collected. Residual [3H]-H2O was removed with Kim Wipe® paper 5 min after it was applied to the skin. The skin was rinsed with a small volume of nonradioactive, distilled water and dried with Kim Wipe® paper three times to remove remaining traces of [3H]-H2O. Receptor fluid was collected for an additional 1 h. The collected receptor fluid was mixed with 10 ml of scintillation fluid and analyzed for [3H]-radioactivity in a Beckman Instruments (Fullerton, CA) 6000LL liquid scintillation analyzer. The mean percentage of the dose of [3H]-H2O detected in the receptor fluid for human cadaver skin was less than 0.05%, indicating an intact barrier, analogous to healthy skin.

Human and rat skin discs were treated with 100 nmol/cm2 of [14C]-TBBPA in 10 μl acetone (~1 μCi). The peristaltic pump was started and fractions were collected every 6 h until 24 h post-dosing, when the peristaltic pump was stopped. The epidermal surface (with the cell top in place) was washed six times with 0.5 ml of a mixture of Joy® liquid soap:water (1:1) to remove unabsorbed chemical. The skin wash fractions were pooled into two vials and mixed with scintillation fluid. The cell top and cell body were individually washed three times with 0.5 ml ethanol. The cell top and body washes and the weigh boat used to wash the cell top were put into separate vials. The skins were allowed to dry overnight. The following day, each skin disk was tape stripped 10 times with clear tape. Each tape strip was placed in a separate vial. Skin washes, cell top and body washes, weigh boats, tape strips and receptor fluid were mixed with scintillation fluid and analyzed for radioactivity in the liquid scintillation analyzer. Washed and stripped skin was then chemically solubilized in 1 ml of Soluene 350 (PerkinElmer) overnight in a water bath set at 37°C. Hionic Fluor (PerkinElmer) was added to the dissolved skin solution, and absorbed [14C]-radioactivity was quantified.

Prior to radiochemical-HPLC analyses, 1 mL aliquots of receptor fluid from each sample were subjected to solid phase extraction using Waters Oasis HLB cartridges (3 mg, part no. WAT094225). Briefly, samples were acidified with 100 μL glacial acetic acid, the column was conditioned with 1 mL methanol/water (50:50, v/v), sample loaded and washed with 1 mL 5% methanol in water then finally eluted with 1 mL of 100% methanol. Eluent was evaporated to dryness using a Savant SPD1010 SpeedVac (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA) without heating, reconstituted in 150 μL methanol and injected onto the HPLC (see below for HPLC conditions).

In vivo experiments

In order to link previously published data characterizing the fate of orally-administered TBBPA in the female rat (17) and the in vitro studies described above, two dose levels were selected for in vivo dermal absorption studies: 100 nmol/cm2 (~0.25 mg/kg) and 1,000 nmol/cm2 (~2.5 mg/kg). Female Wistar Han rats (N = 4 rats/dose group, 11 weeks old, approx. 200 g, Charles River, Raleigh NC) were prepared for non-occluded dermal application of TBBPA as described previously (25). Rats were topically dosed with [14C]-labeled TBBPA (100 μCi/kg, 400 μl/kg) in acetone. One day prior to dosing, animals were lightly anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation and the dorsal surface was clipped with an electric clipper to remove hair from the scapular region. Clipped areas were visually inspected for any nicks or cuts. Animals were returned to polycarbonate shoebox cages for recovery from anesthesia. Immediately prior to dosing, animals were again lightly anaesthetized by isoflurane inhalation, the dosing area visually inspected for nicks and a 1 cm2 area marked. Dosing solution was applied inside the marked area using a ball-tipped needle attached to a Hamilton syringe, allowed to dry, and then the dosing site was covered with a non-occlusive steel mesh cap attached with polyacrylate glue to prevent ingestion of the test article. After dosing, animals were placed in plastic Nalgene metabolism cages for collection of feces & urine. Animals were provided rat feed (NIH 31) and tap water for ad libitum consumption.

Feces, urine, and cage rinses were collected and analyzed as described previously by Knudsen et al. (17) at 24 h intervals. Animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation after 24 or 72 h. Following euthanasia, blood was collected by cardiac puncture, dosed skin was excised, and complete necropsies were performed as described previously (17). Skin from the application area was treated in accordance with the OECD 427 method for in vivo testing of chemicals (26). Briefly, the skin was swabbed 10 times using filter paper soaked with acetone, 10 times using a 10% soap solution, and then tape stripped 10 times using clear tape to maximize recovery of the dose remaining on the surface of the skin. Feces were air dried and ground to a powder using a mortar and pestle. Tissues (including skin) and feces were sampled in triplicate (approx. 25 mg/sample), combusted in a Packard (Waltham, MA, USA) 307 Biological Sample Oxidizer, and [14C]-radioactivity content was quantified by liquid scintillation counting (LSC) analysis. Skin swabs and tape strips were analyzed by direct LSC while urine and cage washes were similarly analyzed in triplicate. Data of the combusted tissues and feces, urine, cage washes, skin swabs and tape strips were used to compute an arithmetic sum of residual [14C]-radioactivity. Samples of minced skin and dried feces (~250 mg) were sequentially extracted with 3 × 5 mL toluene, 3 × 5 mL ethyl acetate, and 3 × 5 mL methanol. Supernatants were pooled in glass vials, concentrated to near dryness without heating (Savant SPD1010 SpeedVac), reconstituted in 1 mL methanol and aliquots injected onto the HPLC.

HPLC-radiochemical analyses

The HPLC system used for analysis of receptor fluid (from the in vitro study) and extracts from dosed skin and feces (from the in vivo study) was composed of a Waters (Milford, MA, USA) 2695 Separations Module, Agilent (Santa Clara, CA, USA) Eclipse Plus C18 column (3.5 μm, 4.6 mm×150 mm), and a Waters 996 Photodiode Array with an in-line Packard Radiomatic 500TR Flow Scintillation Analyzer. Mobile phases consisted of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in water (mobile phase A) and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile (mobile phase B). Sample separations were performed using a gradient; initial conditions (60% A) were maintained for 5 min; A was then reduced to 10% over 2 min then to 0% A over 13 min. The column was returned to initial conditions and allowed to equilibrate for 5 min before re-use. Flow rates were 1 ml/min. Instrument control and analysis software were Empower Pro (Waters Corp.) and FLO-ONE for Windows (Packard, v. 3.6). Radiochemical flow cell was 500 μL and scintillant flow rate was 2 mL/min. TBBPA was quantified based on a 5-point calibration curve using UV absorption at 254 nm and radiochemical detection.

Statistical methods

The data were subjected to statistical analysis using paired t-tests or two-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey-Kramer test for pairwise comparisons (GraphPad Prism 6, GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla CA). Values were considered to be significantly different at p < 0.05.

Parallelogram calculation

The principles of the parallelogram approach to the dermal exposure assessments were used to estimate a likely level following in vivo human systemic exposures to a relevant dose of dermally-applied TBBPA (Equation 1) as described by Ross et al (19). Briefly, in vivo human exposure is estimated as a function of in vitro human exposure multiplied by a normalization factor based on the same dose applied to rat skin in vivo and in vitro.

Equation 1.

Estimation of human in vivo systemic exposure relative to the ratio of animal to human absorption (penetrated + absorbed) of dermally applied chemicals

Results

In vitro studies

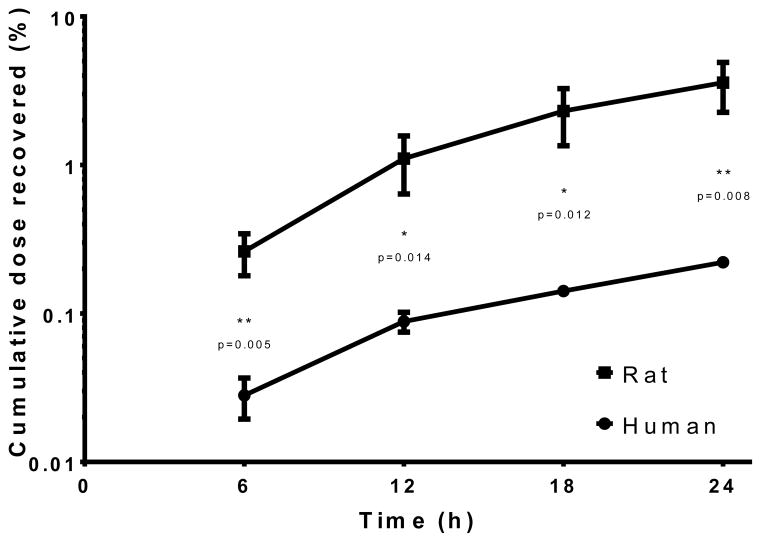

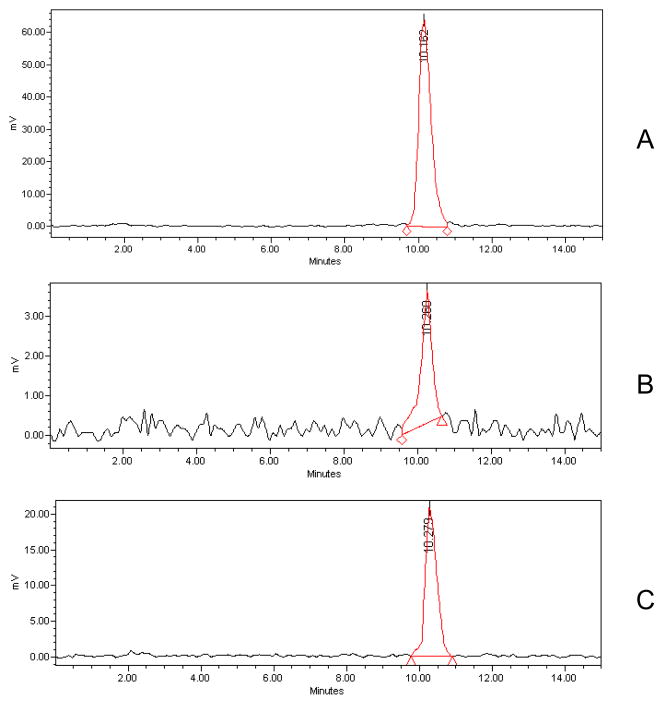

Analysis of the receptor fluid in the in vitro experiments demonstrated penetration of radiolabeled TBBPA (100 nmol/cm2) through both rat and human skin over time (Figure 2). [14C]-TBBPA penetration was significantly lower in human skin (p<0.05) in each 6 hour fraction compared to that in rat skin. 0.2% of the dose applied to human skin was recovered in the receptor fluid whereas approximately 3% of the dose passed through the rat skin in 24 h. The total dose recovery (expressed as percent of administered dose) collected in the receptor fluid, remaining (absorbed) in the skin, and in the wash and tape strips (unabsorbed) is shown in Table 1. Total recoveries were 99%. HPLC-radiometric analyses indicated that all [14C]-radioactivity in the receptor fluid of either the human or rat experiments was recovered as parent TBBPA (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Cumulative total dose recovered in the receptor fluid after a single application of 100 nmol/cm2 [14C]-TBBPA to skin. Penetration was significantly lower in human samples at all time-points evaluated (p<0.05). Data represents mean ± S.D.; N=4 rat; N=3 human.

Table 1.

Recovery of [14C]-radioactivity in various fractions of the in vitro flow-through system at 24 h post-dose.

| Species | Dose (nmol/cm2) | Penetrated (%)(Receptor fluid) | Absorbed (%) (Skin) | Unabsorbed (%)(Washes & strippings) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humana | 100 | 0.2 ± 0.006 | 3.4 ± 1.8 | 95 ± 3 |

| Ratb | 100 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 86 ± 3 |

Mean ± S.D., N = 3, performed in quadruplicate.

Mean ± S.D., N = 4, performed in triplicate.

Figure 3.

Representative HPLC-radiochromatograms of A: TBBPA standard, B: Perfusate from human skin samples, C: Perfusate from rat skin samples.

In vivo studies

In vivo studies were performed to determine the dermal uptake of the TBBPA dose of ~100 or ~1,000 nmol/cm2 over 24 or 72 h. Doses of 100 nmol/cm2 and 1,000 nmol/cm2 behaved similarly in vivo. As observed in the in vitro studies, most of the administered [14C]-radioactivity was recovered unabsorbed from the dosing site within 24 h of administration of 100 nmol/cm2 (Table 2). Continuous exposure over 24 hours to TBBPA resulted in 10–20% of the dose crossing into the skin and systemic circulation at both dose levels. Approximately 14% of the dose was detected in the skin at the dosing site (absorbed) and 8% was present in tissues or excreta (penetrated) for the 100 nmole/cm2 dose group. In this same group, 6% of the dose was recovered in feces with an additional 1–2% found in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract contents at 24 h. Similarly, approx. 5% of the 1,000 nmol/cm2 dose was recovered in feces and GI tract contents. Blood and other tissues contained less than 1% of the administered doses. A summary of the recoveries can be found in Table 3. Lower relative absorption (expressed as a percent of dose) of the 1000 nmol/cm2 dose indicates a saturation of the available pathway(s) across the skin. Despite this apparently lower absorption, the absolute mass that was absorbed increased with dose. This is a relatively frequently observed phenomenon in dermal disposition work (27).

Table 2.

Recovery of [14C]-radioactivity in various fractions of the in vivo system.

| Species | Dose (nmol/cm2) | Exposure (h) | Penetrated (Excreta & tissues, %) | Absorbed (Skin, %) | Unabsorbed (Washes & strippings, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | ~100 | 24 | 7.7 ± 2.4 | 13.6 ± 2.5 | 80 ± 3 |

| Rat | ~1,000 | 24 | 5.3 ± 2.7 | 5.1 ± 3.4 | 85 ± 8 |

| Rat | ~1,000 | 72 | 30 ± 10**** | 40 ± 7.2**** | 30 ± 10**** |

: p<0.0001; amounts of penetrated, absorbed, and unabsorbed dosed at 72 h significantly higher than amounts measured at 24 h for either dose, as determined by 2-way ANOVA. Data presented as mean ± S.D., N=3–4 animals per dose group.

Table 3.

Distribution of [14C]-radioactivity in excreta & tissues (%).

| Species | Dose | Exposure | Matrix | Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (nmol/cm2) | (h) | (%) | ||

| Rat | 100 | 24 | Feces | 6 ± 1.5 |

| Urine | 0.1 ± 0.07 | |||

| Blood | 0.03 ± 0.02 | |||

| Non-GI tissues | 0.3 ± 0.06 | |||

| GI tract tissues | 0.05 ± 0.03 | |||

| GI tract contents | 1.2 ± 0.9 | |||

| Rat | 1,000 | 24 | Feces | 3 ± 0.8 |

| Urine | 0.2 ± 0.3 | |||

| Blood | 0.02 ± 0.004 | |||

| Non-GI tissues | 0.4 ± 0.5 | |||

| GI tract tissues | 0.05 ± 0.03 | |||

| GI tract contents | 1.6 ± 1.3 | |||

| Rat | 1,000 | 72 | Feces | 11 ± 6 |

| Urine | 0.6 ± 0.6 | |||

| Blood | 0.02 ± 0.01 | |||

| Non-GI tissues | 2.8 ± 1.4 | |||

| GI tract tissues | 0.6 ± 0.4 | |||

| GI tract contents | 15 ± 4 |

Data presented as mean ± S.D., N=3–4 animals per study.

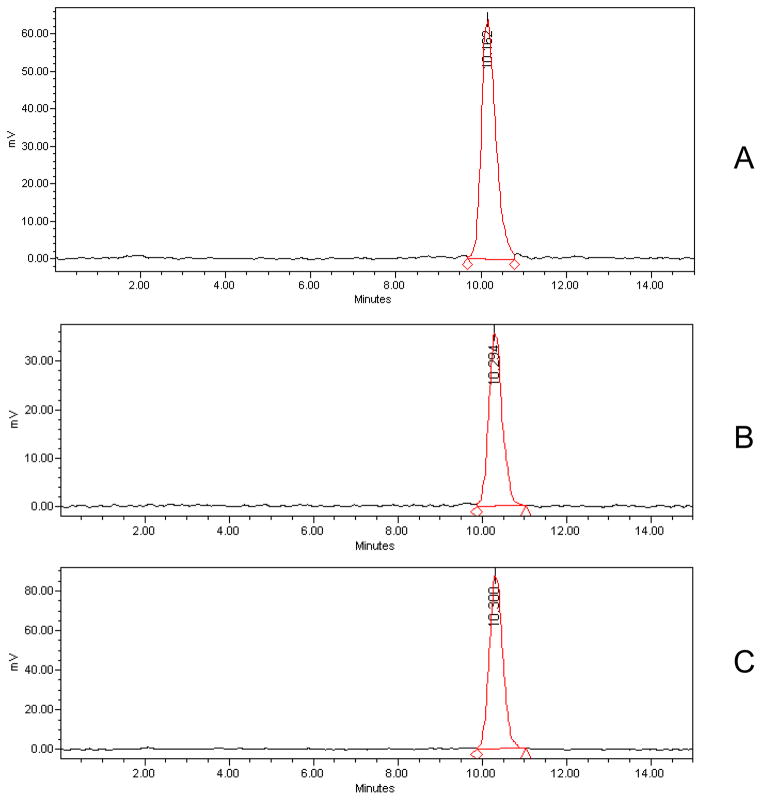

TBBPA was absorbed, distributed, and eliminated via the feces when applied at a dose level of 1,000 nmol/cm2 and left on the skin for 72 h (Table 3). Similar to the roughly linear penetrance of [14C]-TBBPA into the receptor fluid (Figure 2), penetration and absorption, as determined by recovery of [14C]-radioactivity in feces, were continuous between 24 and 72 h (data not shown). By 72 h post-application, feces or GI tract contents contained approx. 30% of the administered [14C]-radioactivity. GI tract tissues contained less than 1% of the dose while ‘non-GI tissues’ contained approx. 3% of the dose, most of which was found in skin collected far from the dosing site (Table 3). HPLC-radiometric analyses of extracts from dosed skin and feces showed all extractable [14C]-radioactivity was recovered as parent (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Representative HPLC radiochromatograms of A: TBBPA standard, B: Extracts of rat skin following 24 h exposure to TBBPA (100 nmol/cm2), C: Extracts of rat feces following 24 h exposure to TBBPA (100 nmol/cm2). HPLC radiochromatograms for the 1,000 nmol/cm2 dose showed only parent TBBPA.

Estimated human bioavailability

Based on the parallelogram calculation, up to 6% of dermally applied TBBPA may be bioavailable to humans exposed to TBBPA.

Discussion

Human exposure to TBBPA via food and dust is a real and persistent issue (28–32). Several studies have illustrated the importance of ingestion of indoor dust as a major pathway for human exposure to TBBPA and other flame retardants (4, 33). However, few have discussed the concomitant dermal exposure to these same flame retardants although there have been repeatedly demonstrated strong positive correlations between flame retardant levels in dust, on hand wipes, and serum concentrations in adults and children (34–36). Despite this, very little is known about the dermal disposition of brominated flame retardants in general (5). The objective of this study was to measure the dermal absorption of TBBPA in rat and human skin to provide a more accurate assessment of bioavailable TBBPA from dermal exposure. Rat skin was more permeable to [14C]-TBBPA than human skin in vitro. Similarly, at 24 h, human skin absorbed and retained much less [14C]-radioactivity than rat skin. [14C]-radioactivity that was absorbed into the skin was recovered as parent TBBPA, as was [14C]-radioactivity recovered in rat feces, which leads to the conclusion that dermally applied TBBPA likely follows similar biotransformation and elimination pathways as those found previously for oral- or intravenous-administered TBBPA in the rat. Biotransformation of orally administered TBBPA is similar in both rats and humans; rats eliminate systemic TBBPA (as glucuronide or sulfate conjugates) exclusively through biliary excretion (15–17), while TBBPA-glucuronide has been measured in human urine (37) although humans likely eliminate conjugated TBBPA via bile as well. Conjugated metabolites are hydrolyzed in the gut, putatively by gut microflora, yielding parent TBBPA. Like previous observations following oral or IV administration, analyses of fecal extracts showed TBBPA is excreted in its unconjugated form after dermal absorption in the rat. In the current study (as seen in Table 3), and consistent with previous studies (15–17), there was minimal retention of absorbed TBBPA in tissues after administration.

These data provided herein are expected to aid in risk assessment for dermal exposures to TBBPA. Over a 24 hour period, the amounts of administered TBBPA that penetrated the human and rat skin in vitro continually increased for all samples, suggesting that duration of exposure increases risk of toxicity. Rat skin is more permeable than human skin for a variety of chemicals (38–40) which may account for the differences in observed penetration and absorption levels of TBBPA by human and rat skin and necessitates the use of a normalizing mechanism to account for differences in dermal uptake between species. Despite species differences in uptake, it is clear that TBBPA can be absorbed by the skin and dermal contact with TBBPA likely plays a small but important route of exposure to humans, e.g., cleaning workers and workers handling electronics equipment (29, 41) but especially small children who are exposed to higher levels of household dust (4). Furthermore, infants and small children may experience an even higher risk for toxic effects of TBBPA owing to the increased surface area to volume ratio, immature detoxification pathways, and rapidly developing nervous systems (42).

The stratum corneum is the primary barrier to dermal absorption. For chemicals such as TBBPA to get through the skin, most, if not all, evidence points to passive diffusion through the stratum corneum, a non-viable layer of the skin. Whether uptake of chemicals into or through viable layers of the epidermis is facilitated by transporters is not clear. Structurally similar brominated flame retardants like the polybrominated diphenyl ether congeners have been most clearly described as substrates for several ‘hepatic’ organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP) family of proteins (43). This includes OATP2B1, a transporter whose expression has been described in liver, spleen, placenta, lung, kidney, heart, ovary, small intestine, brain (44), and most recently, skin (45). Keratinocytes derived from human skin have been reported to express functional OATP transporters, with immune-reactive staining apparent in viable regions of the epidermis (46). Additional studies are needed to determine whether TBBPA is a substrate for this and other transporters expressed in skin.

The non-brominated analog of TBBPA, bisphenol A, has been estimated to have a 24 h dermal bioavailability of approximately 9% (20) and 46% at 72 h (47). In vitro dermal assessments of the decabromodiphenyl oxide (BDE 209) using mouse skin found 2% of a 60 nmol dose was bioavailable (48). One in vivo study of 2,2′,4,4′-tetrabromodiphenyl ether (BDE 47) using female B6C3F1 mice showed less than 10% of a 1 mg/kg dose excreted in urine and feces over 24 h where approx. 77% of the dose was bioavailable (e.g., recovered at the dose site or within tissues & excreta) over 5 days (49).

Systemic quantification of internal TBBPA levels after occupational, consumer, and environmental exposures to dust containing TBBPA likely results from at least two routes, ingestion and dermal contact. We therefore applied the principles of the parallelogram approach to the dermal exposure assessments to estimate a likely level following in vivo human systemic exposures to a relevant dose of dermally-applied TBBPA, as described by Ross et al. (19). Ross et al. (19) reported a conservative estimate of ±3-fold uncertainty for the parallelogram method applied herein. However, as noted by Jung & Maibach (50), this uncertainty factor was primarily driven by two selected agents, fluazifop-butyl (overpredicted absorption) and o-phenylphenol (underpredicted absorption). When the three studies (in vitro human, in vitro rat, in vivo rat) were performed concurrently in the same laboratory, the ratio of predicted to measured human dermal absorption was <1.7-fold and often approached unity. Based on this parallelogram methodology, approx. 6% of dermally applied TBBPA may be bioavailable to humans exposed to TBBPA.

Highlights.

Tetrabromobisphenol A is the brominated flame retardant with highest global production volumes.

Humans are frequently exposed to TBBPA by the dermal route, especially via contaminated dust.

Human and rat skin data were integrated using a parallelogram method to predict human absorption.

TBBPA was dermally absorbed and skin contact may represent a small but important route of exposure.

Up to 6% of dermally applied TBBPA may be bioavailable to humans exposed to TBBPA.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Brenda Edwards, Mr. Vivek Miyani, Mr. Rohil Chekuri, Mr. Ethan Hull, and Mr. Abdella Sadik for technical assistance. This article has been reviewed in accordance with the policy of the National Health and Environmental Effects Research Laboratory, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and approved publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of NIH/NCI.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.BSEF. TBBPA Factsheet. Bromine Science and Environment Forum; 2012. http://wwwbsefcom/uploads/Factsheet_TBBPA_25-10-2012pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Wit CA, Herzke D, Vorkamp K. Brominated flame retardants in the Arctic environment — trends and new candidates. Science of The Total Environment. 2010;408(15):2885–918. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.08.037. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canada. Screening Assessment Report: Phenol, 4,4′-(1-methylethylidene) bis[2,6-dibromo-, Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number 79-94-7; Ethanol, 2,2′-[(1-methylethylidene)bis[(2,6-dibromo-4,1-phenylene)oxy]]bis, Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number 4162-45-2; Benzene, 1,1′-(1-methylethylidene)bis[3,5-dibromo-4-(2-propenyloxy)-, Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number 25327-89-3. Environment Canada, Health Canada; 2013. Found at: http://www.ec.gc.ca/ese-ees/BEE093E4-8387-4790-A9CD-C753B3E5BFAD/FSAR_TBBPA_EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stapleton HM, Allen JG, Kelly SM, Konstantinov A, Klosterhaus S, Watkins D, McClean MD, Webster TF. Alternate and new brominated flame retardants detected in U.S. house dust. Environmental science & technology. 2008;42(18):6910–6. doi: 10.1021/es801070p. Epub 2008/10/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdallah MA, Pawar G, Harrad S. Evaluation of in vitro vs. in vivo methods for assessment of dermal absorption of organic flame retardants: a review. Environment international. 2015;74:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.09.012. Epub 2014/10/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunnick JK, Sanders JM, Kissling GE, Johnson C, Boyle MH, Elmore SA. Environmental Chemical Exposure May Contribute to Uterine Cancer Development: Studies with Tetrabromobisphenol A. Toxicologic pathology. 2014 doi: 10.1177/0192623314557335. Epub 2014/12/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders JM, Coulter SJ, Knudsen GA, Dunnick JK, Birnbaum LS. Disruption of estrogen homeostasis as a mechanism for carcinogenesis in the uterus of Wistar Han rats treated with tetrabromobisphenol A. Toxicol Sci. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2016.03.007. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NTP. TR-587: Technical Report Pathology Tables and Curves for TR-587: Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) National Toxicology Program, Health and Human Services; 2013. Found at: http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/38602. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van der Ven LT, Van de Kuil T, Verhoef A, Verwer CM, Lilienthal H, Leonards PE, Schauer UM, Canton RF, Litens S, De Jong FH, Visser TJ, Dekant W, Stern N, Hakansson H, Slob W, Van den Berg M, Vos JG, Piersma AH. Endocrine effects of tetrabromobisphenol-A (TBBPA) in Wistar rats as tested in a one-generation reproduction study and a subacute toxicity study. Toxicology. 2008;245(1–2):76–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2007.12.009. Epub 2008/02/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cope RB, Kacew S, Dourson M. A reproductive, developmental and neurobehavioral study following oral exposure of tetrabromobisphenol A on Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicology. 2015;329:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2014.12.013. Epub 2014/12/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu F, Pan L, Xiu M, Jin Q, Wang G, Wang C. Bioaccumulation and detoxification responses in the scallop Chlamys farreri exposed to tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) Environmental toxicology and pharmacology. 2015;39(3):997–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2015.03.006. Epub 2015/04/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miao J, Cai Y, Pan L, Li Z. Molecular cloning and characterization of a MXR-related P-glycoprotein cDNA in scallop Chlamys farreri: transcriptional response to benzo(a)pyrene, tetrabromobisphenol A and endosulfan. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety. 2014;110:136–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.08.029. Epub 2014/09/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dankers AC, Roelofs MJ, Piersma AH, Sweep FC, Russel FG, van den Berg M, van Duursen MB, Masereeuw R. Endocrine disruptors differentially target ATP-binding cassette transporters in the blood-testis barrier and affect Leydig cell testosterone secretion in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 2013;136(2):382–91. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft198. Epub 2013/09/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ECHA. 2,2′,6,6′-tetrabromo-4,4′-isopropylidenediphenol, Toxicological Information, Dermal Absorption. European Chemicals Agency; 2005. http://apps.echa.europa.eu/registered/data/dossiers/DISS-9d928727-4180-409d-e044-00144f67d249/AGGR-45b42473-285a-433f-880c-54ef369e6659_DISS-9d928727-4180-409d-e044-00144f67d249.html. cited 2015 2/11/2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakk H, Larsen G, Bergman A, Orn U. Metabolism, excretion and distribution of the flame retardant tetrabromobisphenol-A in conventional and bile-duct cannulated rats. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems. 2000;30(9):881–90. doi: 10.1080/004982500433309. Epub 2000/10/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuester RK, Solyom AM, Rodriguez VP, Sipes IG. The effects of dose, route, and repeated dosing on the disposition and kinetics of tetrabromobisphenol A in male F-344 rats. Toxicol Sci. 2007;96(2):237–45. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm006. Epub 2007/01/20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knudsen GA, Sanders JM, Sadik AM, Birnbaum LS. Disposition and kinetics of tetrabromobisphenol A in female Wistar Han rats. Toxicology Reports. 2014;1(0):214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.03.005. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sobels FH. Some problems associated with the testing for environmental mutagens and a perspective for studies in “comparative mutagenesis”. Mutation research. 1977;46(4):245–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-1161(77)90001-2. Epub 1977/08/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross JH, Reifenrath WG, Driver JH. Estimation of the percutaneous absorption of permethrin in humans using the parallelogram method. Journal of toxicology and environmental health Part A. 2011;74(6):351–63. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2011.534425. Epub 2011/01/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Demierre AL, Peter R, Oberli A, Bourqui-Pittet M. Dermal penetration of bisphenol A in human skin contributes marginally to total exposure. Toxicology letters. 2012;213(3):305–8. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.07.001. Epub 2012/07/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.OECD. Test No. 428: Skin Absorption: In Vitro Method. OECD Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bronaugh RL, Stewart RF. Methods for in vitro percutaneous absorption studies IV: The flow-through diffusion cell. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 1985;74(1):64–7. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600740117. Epub 1985/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bronaugh RL, Maibach HI. In vitro Percutaneous Absorption: Principles, Fundamentals, and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collier SW, Sheikh NM, Sakr A, Lichtin JL, Stewart RF, Bronaugh RL. Maintenance of skin viability during in vitro percutaneous absorption/metabolism studies. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 1989;99(3):522–33. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(89)90159-2. Epub 1989/07/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winter SM, Sipes IG. The disposition of acrylic acid in the male Sprague-Dawley rat following oral or topical administration. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association. 1993;31(9):615–21. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(93)90043-x. Epub 1993/09/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.OECD. Test No. 427: Skin Absorption: In Vivo Method. OECD Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wester RC, Maibach HI. Interrelationships in the dose response of percutaneous absorption. In: Bronaugh RL, Maibach HI, editors. Percutaneous absorption: Mechanisms-Methodology-Drug Delivery. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1985. pp. 347–57. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Abualnaja KO, Asimakopoulos AG, Covaci A, Gevao B, Johnson-Restrepo B, Kumosani TA, Malarvannan G, Minh TB, Moon HB, Nakata H, Sinha RK, Kannan K. A comparative assessment of human exposure to tetrabromobisphenol A and eight bisphenols including bisphenol A via indoor dust ingestion in twelve countries. Environment international. 2015;83:183–91. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.06.015. Epub 2015/07/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deng J, Guo J, Zhou X, Zhou P, Fu X, Zhang W, Lin K. Hazardous substances in indoor dust emitted from waste TV recycling facility. Environmental science and pollution research international. 2014;21(12):7656–67. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2662-9. Epub 2014/03/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang Y, Guan J, Yin J, Shao B, Li H. Urinary levels of bisphenol analogues in residents living near a manufacturing plant in south China. Chemosphere. 2014;112:481–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.05.004. Epub 2014/07/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodson RE, Perovich LJ, Covaci A, Van den Eede N, Ionas AC, Dirtu AC, Brody JG, Rudel RA. After the PBDE phase-out: a broad suite of flame retardants in repeat house dust samples from California. Environmental science & technology. 2012;46(24):13056–66. doi: 10.1021/es303879n. Epub 2012/11/29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.EFSA. EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM): Scientific Opinion on Emerging and Novel Brominated Flame Retardants (BFRs) in Food. EFSA Journal. 2012;10(10):133. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2908. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyce CP, Sonja N, Dodge DG, Pollock MC, Goodman JE. Human exposure to decabromodiphenyl ether, tetrabromobisphenol A, and decabromodiphenyl ethane in indoor dust. JEPS. 2009;3:75–96. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carignan CC, Heiger-Bernays W, McClean MD, Roberts SC, Stapleton HM, Sjodin A, Webster TF. Flame retardant exposure among collegiate United States gymnasts. Environmental science & technology. 2013;47(23):13848–56. doi: 10.1021/es4037868. Epub 2013/11/08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stapleton HM, Misenheimer J, Hoffman K, Webster TF. Flame retardant associations between children’s handwipes and house dust. Chemosphere. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.12.100. Epub 2014/02/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watkins DJ, McClean MD, Fraser AJ, Weinberg J, Stapleton HM, Webster TF. Associations between PBDEs in office air, dust, and surface wipes. Environment international. 2013;59:124–32. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.06.001. Epub 2013/06/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schauer UM, Volkel W, Dekant W. Toxicokinetics of tetrabromobisphenol a in humans and rats after oral administration. Toxicol Sci. 2006;91(1):49–58. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj132. Epub 2006/02/17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Api AM, Ritacco G, Hawkins DR. The fate of dermally applied [14C]d-limonene in rats and humans. International journal of toxicology. 2013;32(2):130–5. doi: 10.1177/1091581813479979. Epub 2013/03/16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moody RP, Nadeau B, Chu I. In vivo and in vitro dermal absorption of benzo[a]pyrene in rat, guinea pig, human and tissue-cultured skin. Journal of dermatological science. 1995;9(1):48–58. doi: 10.1016/0923-1811(94)00356-j. Epub 1995/01/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Ravenzwaay B, Leibold E. A comparison between in vitro rat and human and in vivo rat skin absorption studies. Human & experimental toxicology. 2004;23(9):421–30. doi: 10.1191/0960327104ht471oa. Epub 2004/10/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jakobsson K, Thuresson K, Rylander L, Sjodin A, Hagmar L, Bergman A. Exposure to polybrominated diphenyl ethers and tetrabromobisphenol A among computer technicians. Chemosphere. 2002;46(5):709–16. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(01)00235-1. Epub 2002/05/10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.USEPA; Exposure Assessment Group OoHaEA, editor. Dermal Exposure Assessment: Principles and Applications. Washington, DC: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pacyniak E, Roth M, Hagenbuch B, Guo GL. Mechanism of polybrominated diphenyl ether uptake into the liver: PBDE congeners are substrates of human hepatic OATP transporters. Toxicol Sci. 2010;115(2):344–53. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq059. Epub 2010/02/24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kullak-Ublick GA, Ismair MG, Stieger B, Landmann L, Huber R, Pizzagalli F, Fattinger K, Meier PJ, Hagenbuch B. Organic anion-transporting polypeptide B (OATP-B) and its functional comparison with three other OATPs of human liver. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(2):525–33. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21176. Epub 2001/02/13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fujiwara R, Takenaka S, Hashimoto M, Narawa T, Itoh T. Expression of human solute carrier family transporters in skin: possible contributor to drug-induced skin disorders. Scientific reports. 2014;4:5251. doi: 10.1038/srep05251. Epub 2014/06/12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schiffer R, Neis M, Holler D, Rodriguez F, Geier A, Gartung C, Lammert F, Dreuw A, Zwadlo-Klarwasser G, Merk H, Jugert F, Baron JM. Active influx transport is mediated by members of the organic anion transporting polypeptide family in human epidermal keratinocytes. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2003;120(2):285–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12031.x. Epub 2003/01/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zalko D, Jacques C, Duplan H, Bruel S, Perdu E. Viable skin efficiently absorbs and metabolizes bisphenol A. Chemosphere. 2011;82(3):424–30. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.09.058. Epub 2010/10/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hughes MF, Edwards BC, Mitchell CT, Bhooshan B. In vitro dermal absorption of flame retardant chemicals. Food and chemical toxicology : an international journal published for the British Industrial Biological Research Association. 2001;39(12):1263–70. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(01)00074-6. Epub 2001/11/07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Staskal DF, Diliberto JJ, DeVito MJ, Birnbaum LS. Toxicokinetics of BDE 47 in female mice: effect of dose, route of exposure, and time. Toxicol Sci. 2005;83(2):215–23. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi018. Epub 2004/10/29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jung EC, Maibach HI. Animal models for percutaneous absorption. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2015;35(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/jat.3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]