Abstract

Previous studies have identified the immunological functions of transcription factor B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1 (Blimp-1) in various adaptive immune cell types such as T and B lymphocytes. More recently, it has been shown that Blimp-1 extends its functional roles to dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages, two cell types belonging to the innate immune system. The protein acts as a direct and indirect regulator of target genes by recruiting chromatin modification factors and by regulating microRNA expression, respectively. In DCs, Blimp-1 has been identified as one of the components involved in antigen presentation. Genome-wide association studies identified polymorphisms associated with multiple autoimmune diseases such as system lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease in PRDM1, the gene encoding Blimp-1 protein. In this review, we will discuss the immune regulatory functions of Blimp-1 in DCs with a main focus on the tolerogenic mechanisms of Blimp-1 required to protect against the development of autoimmune diseases.

Keywords: Dendritic cells, Blimp-1, Antigen presentation, SLE

Discovery of Blimp-1

B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1 (Blimp-1) was first identified and characterized in human cDNA clones by Maniatis and colleagues [1] followed by the discovery of murine Blimp-1 by Davis and colleagues three years later [2]. Human PR domain containing 1 with zinc finger domain (PRDM1) (a gene encoding Blimp-1 protein) is located at chromosome 6q21 and contains 789 amino acids. Murine Prdm1 is located at 10qB2 and contains 856 amino acids. Despite the fact that murine Blimp-1 contains 67 additional amino acids at the N-terminus, the human and mouse proteins are highly homologous and are interchangeable in functional assays [3]. Structural analysis clearly shows the similarity between human and mouse Blimp-1 protein; both contain zinc finger DNA-binding domains, a proline-rich region (PR) and an acidic region. Although five zinc finger motifs are implicated in DNA binding, only the first two zinc finger motifs are necessary for recognition of positive regulatory domain I (PRDI) in the IFNβ promoter [4]. The DNA consensus sequence of Blimp-1 was determined and is very similar to that of interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 1 and IRF2 [1, 4, 5]. In fact, Blimp-1 is induced upon virus infection, and Blimp-1 and IRF1/2 compete for binding to the IRF binding site in the IFNβ promoter [5].

The PR domain in Blimp-1 has similarities with the SET domain found in histone methyl transferases (HMT) [6]. Although the PR domain of Blimp-1 does not have HMT activity, Blimp-1 can recruit the G9a HMT to the IFNb promoter as in the osteosarcoma cell line U2OS in which ectopic expression of Blimp-1 represses IFNβ expression through the recruitment of G9a, which induces repressive histone modification at lysine 9 on histone 3 (H3K9) [7]. In primordial germ cells, Blimp-1 complexed with prmt5, an arginine HMT, which catalyzes dimethylation of arginine 3 on H2A and H4 [8]. More recently, Blimp-1 has been shown to regulate gene expression in CD8 T cells by recruitment of G9a and histone deacetylase 2 (HDAC2) [9]. These studies suggest that Blimp-1 acts as a transcriptional repressor of target genes through its recruitment of histone modulating co-repressors to create a more compact chromatin structure.

What induces Blimp-1 expression? Activation of pattern recognition receptors and their respective signaling pathways positively regulates Blimp-1 expression in B and T lymphocytes [1]. This was first demonstrated in viral infection experiments in which Blimp-1 transcription was induced upon Sendai virus infection in the U20S cell line. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is a Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 agonist, is a strong inducer of Blimp-1 expression in splenic B cells and B-1 B cells [10, 11]. TLR9 activation induces Blimp-1 expression in mouse marginal zone (MZ) B cells and B-1 B cells [12] and in human naïve B cells, transitional B cells, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells [13–15]. Several cytokines induce Blimp-1 expression including IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-21 via signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), strongly implicating STAT3 as a direct regulator of Blimp-1 expression [16–19]. Two other transcription factors, interferon responsive factor 4 (IRF4) and activator protein-1 (AP-1), can bind directly to the PRDM1 promoter region and activate its transcription [20–23] (summary Table 1: Signals induce Blimp-1 expression).

Table 1.

Signaling pathways which are positively regulating Blimp-1 expression

| Stimulus | Pathway | Cell type |

|---|---|---|

| Sendai virus (ds RNA virus) | TLR3/RIG-I | U20S cell line |

| LPS | TLR4 | Mouse splenic B cells, B-1 B cells |

| CpG | TLR9 | Mouse marginal zone B cells B-1 B cells, human naive B cells, transitional B cells, CLL B lymphoma |

| IL2a, IL-4, and IL-10 | Stat3 | Mouse CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, mouse splenic B cells |

| IL-6 and IL-21 | Stat3 | Human B cells |

| IRF4 | Mouse B cells and T cells | |

| AP-1 | Raji B lymphoma, mouse splenic B cells |

IL-2 negatively regulates Blimp-1 expression

Blimp-1 as a risk factor in autoimmune diseases

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been used to assay thousands of individuals identifying hundreds of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) associations with over 80 diseases (http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies). Initial GWAS identified approximately 50 gene loci with polymorphisms which predispose to SLE (review in [24]). This study confirmed the genes that were previously identified to be associated with SLE, for example human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules [25, 26]. The identified genes could be grouped into three functional categories: interferon-alpha (IFNα) signaling pathway, lymphocyte activation signaling pathways, and apoptotic cell clearance pathway. Genes belonging to the IFNα signaling pathway include Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 [27], IRF5 [28], signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT4) [29], interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) [30], and tumor necrosis factor-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3) [31]. Genes belonging to lymphocyte activation signaling pathway play roles in regulation and suppression of lymphocyte activation, including protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 22 (PTPN22) [32], programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) [33], LYN [34], and B lymphocyte kinase (BLK) [35, 36]. Polymorphisms in another group of genes are involved in apoptotic cell clearance, including C1q [37], FcgammaRIIA [38], C-reactive protein (CRP) [39], FcRIIB [40, 41], and integrin alpha M (ITGAM) [42, 43].

SNPs in the intergenic region between PRDM1 and autophagy 5(ATG5) have been identified as candidate risk factors for SLE in European ancestry (rs6568431, OR = 1.2, p = 7.12 × 10−10) [44] and in the Chinese Han population (rs548234, OR = 1.25, p = 5.18 9 10−12) [45]. Following the initial association studies, meta-analysis of this region confirmed the association with SLE in the Chinese Han population [46]. As shown in the case of other genes, polymorphisms in Blimp-1 are not restricted to SLE and are associated with other autoimmune diseases as well; for example, SNP rs5458421 has been known to be associated with SLE as well as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [47]. The rs548234 SNP has been shown to increase the expression of ATG5 in B cells in individuals with the homozygous risk (C/C) allele. Due to the role of Blimp-1 in B cell differentiation, many previous studies focused on identifying how Blimp-1 and its SNPs contribute to SLE pathogenesis in B cells. However, it has been shown that Blimp-1 expression in total B cells in blood is extremely low, and its expression is not affected by SNPs. Given the important role of DCs and their function in SLE, we decided to investigate the role of Blimp-1 in DCs. Moreover, causal variants have often been shown to directly regulate gene expression in a cell-type-specific manner; therefore, it might be important to investigate the function of SNP in non-B cells.

Blimp-1 in dendritic cells

Blimp-1 has been well described to function as a master regulator of plasma cell differentiation in B cells and of cytokine expression in CD4+ T cells (reviewed in [48]). An initial study in innate immune cells identified Blimp-1 expression as a lineage determinant for myeloid cells in vitro [49]. In this study, Blimp-1 suppressed granulocyte lineage differentiation and was required for monocyte differentiation. These data prompted investigators to study whether Blimp-1 is a lineage determinant in monocytic cells such as macrophages and DCs in vivo. In fact, following this study, Glimcher and colleagues published that X-box binding protein (XBP)-1 expression is critical for DC differentiation in vivo [50]. XBP-1 deficient mice possessed a reduced number of both cDCs and pDCs at steady state and under TLR-stimulated inflammatory conditions. Although XBP-1 is not a direct target of Blimp-1, expression of XBP-1 showed a correlation with the level of Blimp-1 and is downstream of Blimp-1 in B cells during B cell differentiation [51]. These observations suggest that Blimp-1 might act as a lineage determinant or survival factor for DC differentiation.

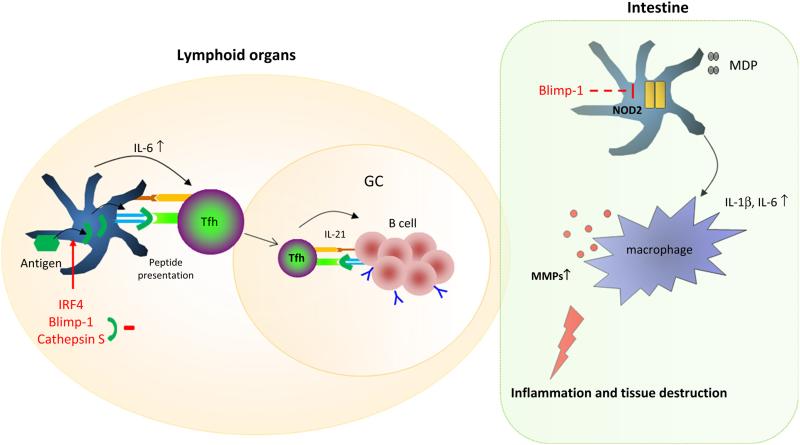

To test whether Blimp-1 expression regulates DC differentiation in vivo, we generated conditional knockout mice in which Blimp-1 is specifically deleted in DCs using a CD11c (a pan DC marker in mice)-dependent CRE system. The CD11c-restricted DC-specific Blimp-1 conditional knockout mice (Blimp-1 CKO mice) are born at Mendelian frequency and indistinguishable in appearance from control mice, showing normal development in their early stages. However, the adult females spontaneously develop a lupus-like phenotype following maturation which includes increased serum immunoglobulin level, increased anti-dsDNA antibodies, splenomegaly, and lymph adenopathy. They also displayed glomerulonephritis, proteinuria without anti-dsDNA IgM antibodies at an age of 10–12 months [52]. Blimp-1-deficient DCs in these mice secreted an increased level of proinflammatory cytokines, noticeably IL-6, following TLR4 stimulation. There are controversial reports as to whether IL-6 is critical for follicular help T (Tfh) cell differentiation [53, 54], but it can function as a major inducer of early differentiation of Bcl-6+ CXCR5+ Tfh cell differentiation [55]. The induction of Bcl6, a master transcription factor for Tfh cell differentiation, by IL-6 and its receptor require both signal transducers, STAT1 and STAT3. In fact, one of the mechanisms of lupus development in Blimp-1 CKO mice was an increased differentiation of follicular helper T cells (Tfh) in the spleen. The increased Tfh cells induced germinal center (GC) formation, contributing to the generation of autoreactive B cells in spleens of Blimp-1 CKO mice. Decreased IL-6 production in Blimp-1 CKO mice can reverse the lupus-like phenotype by reducing Tfh cell frequency, GC formation, and anti-dsDNA antibodies in blood. These data suggest that increased IL-6 production in Blimp-1 deficient DCs is a major pathological mechanism for autoimmune diseases.

We also observed that Blimp-1-deficient DCs show an increased expression of multiple other proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines following LPS stimulation. The induction of a negative regulator of the TLR signaling pathway, suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS-1), was severely decreased. SOCS-1 is regulated indirectly by Blimp-1 through regulation of microRNa Let-7c. In Blimp-1-deficient DCs, an increased level of Let-7c is observed, leading to the downregulation of SOCS-1. Moreover, there was a direct correlation between the level of Blimp-1 and SOCS-1, demonstrated by siRNA and overexpression of Blimp-1 in Blimp-1-deficient DCs [56]. These data suggest that Blimp-1 can regulate cellular function through direct regulation of protein-coding genes and indirectly through regulation of microRNA.

As described in the previous section, PRDM1 has polymorphisms that are associated with SLE. To pursue whether a Blimp-1 polymorphism contributes to the development of SLE, we decided to investigate whether there is different Blimp-1 expression in leukocytes of risk allele carriers and non-risk allele carriers (controls). Interestingly, there was decreased Blimp-1 expression in CD14+ monocyte-derived-DCs (MO-DCs) obtained from SLE risk allele carriers compared to MO-DCs from controls. This phenotype was only observed in young female carriers, not in male carriers or in older female carriers (age over 55 or menopause) [56]. The reduced Blimp-1 phenotype was not observed in total B cells or regulatory T cells (Tregs) from the SLE risk allele carrier group. Therefore, the data suggest that the PRDM1 polymorphism might regulate Blimp-1 expression in a cell-type-dependent manner with a gender bias toward females in which female hormones such as estrogen may play a role in the regulatory mechanisms. Similar to mouse Blimp-1-deficient DCs, in comparison with MO-DCs from the control group, MODCs from SLE risk carriers expressed a higher HLA-DR level and upon TLR4 stimulation secreted an increased level of proinflammatory cytokine IL-6, suggesting that Blimp-1 regulates DC function in human and mice in a comparable manner and that a low Blimp-1 level due to the risk allele in DCs contributes the development of SLE in women.

Blimp-1 in intestinal DCs

Previous studies have identified that Blimp-1 in T cells possesses immune regulatory functions in the development of IBD in an animal model. [57]. However, an analysis of cell-type expression specificity of genes in IBD risk loci found the strongest enrichment in DCs, suggesting that DCs are a critical player for IBD pathogenesis [58]. We demonstrated that Blimp-1 is highly expressed in a subset of DCs found in the intestine: CD11b+ CD103+ double-positive DCs. Moreover, this expression pattern is consistent in mouse and human intestinal DCs, and human circulating DCs [59]. There is a specific reduction of CD11b+ CD103+ DCs in the intestine [not in peripheral lymphoid organs or mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs)] in Blimp-1 CKO, supporting that Blimp-1 plays a critical role in the differentiation or survival of CD11b+ CD103+ intestinal DCs. Moreover, Blimp-1 CKO mice show an increased susceptibility to dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced IBD with high mortality [60]. Blimp-1-deficient DCs secrete increased inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β and IL-6, following muramyl dipeptide (MDP) stimulation. MDP is a ligand of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2), and individuals with a NOD2 mutation are predisposed to IBD development [61]. There was an increased influx of neutrophils and activated macrophages in inflamed colon of Blimp-1 CKO mice compared to control mice. The increased IL-1β and IL-6 induces the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) 7, 8, and 12 in macrophages leading to exacerbated inflammation and tissue damage. This is a novel function of intestinal DCs regulated by Blimp-1 which has implications for human IBD pathogenesis.

Blimp-1 regulates antigen presentation

An earlier study showed that Blimp-1 can regulate antigen presentation in B cells [62]. Blimp-1 can directly suppress class II transactivator (CIITA), the master regulator of MHC II genes. A human homologue of murine Blimp-1, PRDI-BF1, can suppress CIITA in mouse cells, implicating a cross-species regulation. Ectopic expression of Blimp-1 in pre-B cells decreases both endogenous CIITA and CIITA target genes, including invariant chain, H2-DM, and MHC II. Thus, Blimp-1 regulates B cell differentiation and antigen presentation by direct regulation of CIITA expression.

Blimp-1 has also been shown to regulate CIITA expression in human MO-DCs [63]. During the immature state of MO-DCs, the transcriptional activator PU.1 binds to the promoter region of CIITA with the help of Irf8, a critical cofactor for PU.1 binding. During the maturation process, Blimp-1 replaces the PU.1/Irf8 complex and represses the transcription of CIITA by recruiting co-repressor G9a and HDAC2, leading to a closed chromatin configuration. A more recent study demonstrated that Blimp-1 might function in the antigen presentation process in murine CD11b+ DCs [64]. Blimp-1 is highly expressed in CD11b+ DCs but is expressed in low levels in CD8+ DCs and CD11b− DCs. Its expression is correlated with the expression of Irf4 and Cathepsin S (CtsS). Interestingly, Irf4 and Irf8 showed an opposite expression pattern in DC subsets, and CTIIA was shown to not be correlated with either Irf4 or Irf8 in DCs. Irf4 has been identified as a positive regulator of Blimp-1 expression in murine Treg, and Blimp-1 expression is required for IL-10 production in Tregs mainly in mucosal site [65]. The mechanism of Irf4-mediated Blimp-1 expression in DCs has not been investigated yet.

Tfh cells play a key role in immune activation as a key helper T cell type for GC formation. Tight regulation of Tfh development/resolution is critical, and dysregulation of Tfh activity has shown to be closely related with development of SLE. There is a consistent observation that an increased Tfh differentiation correlated with development of a lupus-like phenotype in mice [52, 66]. In human SLE patients, there is an increased frequency of circulating Tfh-like cells in blood [67]. It is well accepted that the interaction with DCs in the T cell zones of lymphoid organs, a fraction of activated CD4+ T cells, committed to Tfh cells upregulating a follicle homing chemokine receptor, CXCR5, and a master transcription factor, Bcl-6, while downregulating CCR7 [68–70]. The signals delivered from the initial interaction with DCs determine Tfh subsets mainly through the combination of cytokines and peptides presented by DCs which govern a signal strength of T cell receptor. Recent data suggest that the development of Tfh cells might differ between mice and human. In humans, TGFb works together with IL-12 and L-23 to promote Tfh differentiation; however, TGFβ signals suppress molecules (Bcl-6, IL-21, and ICOS) in Tfh in mice [53, 71].

To further understand the mechanism of Blimp-1 in antigen presentation in DCs, we investigated whether Blimp-1 can directly regulate expression of CtsS. There is a consensus sequence of Blimp-1 binding motif GAAAGT in the CtsS promoter region in mouse (−30/−25) and human (+1/+6), suggesting that CtsS is a putative target of Blimp-1 in DCs. In fact, there was an increased expression level of CtsS in Blimp-1-deficient murine DCs and Blimp-1 low MO-DCs from SLE risk allele carriers (manuscript in preparation).

CtsS is a lysosomal cysteine protease that is expressed in antigen-presenting cells including B cell, macrophages, and DCs [72]. CtsS participates in the degradation process of invariant chain facilitating peptide loading to MHC II followed by translocation of the peptide/MHC II complex to the cell surface [73]. CtsS also degrades phagocytosed antigens, establishing the pool of peptides presented in MHC II [74]. Since helper T cell differentiation is regulated not only by pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines but also by the strength of T cell receptor binding to MHC II [75], modulation of CtsS by Blimp-1 in DCs may regulate T cell responses, including differentiation of Tfh cells. In fact, CtsS has become a therapeutic target in various inflammatory disorders that are mediated by CD4+ T cells, and inhibition of CtsS has shown to suppress disease severity in various animal models [76–78]. Oral administration of CtsS inhibitor has shown to suppress lupus development in MRL/lpr mouse model [79], leading us to investigate whether Blimp-1 participates in the development of lupus through the regulation of CtsS, thereby modulating the peptide pool which induces preferential differentiation of Tfh cells (summary Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Tissue-dependent role of Blimp-1 in DCs. Altering the levels of Irf4, Blimp-1, and CtsS could change the production of inflammatory cytokines and peptides presented by DCs, modulating T cell differentiation and antigen specificity in lymphoid organs. In the intestine, Blimp-1 regulates NOD2 expression preventing excessive production of IL-1b and IL-6. These cytokines could induce macrophage activation and production of tissue remodeling enzymes, leading to severe tissue damage

Summary and future works

Since the first discovery of Blimp-1, there is increasing appreciation of Blimp-1 as a critical regulator in both human and mouse immune systems. Polymorphisms in Blimp-1 are associated with autoimmune diseases, including SLE, RA, and IBD. Most studies have previously focused on Blimp-1's role in lymphocytes and the adaptive immune response, but it is widely accepted that Blimp-1 plays an important role in innate immune response as well. We have identified an immune tolerogenic function of Blimp-1 in DCs, mainly through the regulation of proinflammatory cytokines and microRNA. Blimp-1 may also participate in the process of antigen presentation in DCs, regulating CIITA and/or CtsS expression.

Important and interesting questions remain to be answered regarding the role of Blimp-1 in DCs. A complete understanding of target molecules in DCs or DC subsets needs to be addressed. It will be of interest to know whether Blimp-1 function is similar or different in DC subsets in lymphoid organs and tissues. So far, studies of Blimp-1 have been performed in murine cDCs and MODCs in human. Based on the broad expression of Blimp-1 in various cell types, it will be critical to understand its role in the spectrum of DC subsets. This will give insight into the various roles that Blimp-1 can play in multiple cell lineages.

Acknowledgments

The author wish to thank Dr. Betty Diamond for providing support and scientific criticisms throughout the project, Dr. Gregersen for guidance for human genetics and human samples, and Sylvia Jones for helping the manuscript. SJ Kim is supported by R01 AR065209 and K01 AR59378.

Biography

Sun Jung Kim

Footnotes

Author has no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Keller AD, Maniatis T. Identification and characterization of a novel repressor of beta-interferon gene expression. Genes Dev. 1991;5(5):868–79. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner CA, Jr, Mack DH, Davis MM. Blimp-1, a novel zinc finger-containing protein that can drive the maturation of B lymphocytes into immunoglobulin-secreting cells. Cell. 1994;77(2):297–306. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90321-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang S. Blimp-1 is the murine homolog of the human transcriptional repressor PRDI-BF1. Cell. 1994;78(1):9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90565-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keller AD, Maniatis T. Only two of the five zinc fingers of the eukaryotic transcriptional repressor PRDI-BF1 are required for sequence-specific DNA binding. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12(5):1940–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo TC, Calame KL. B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein (Blimp)-1, IFN regulatory factor (IRF)-1, and IRF-2 can bind to the same regulatory sites. J Immunol. 2004;173(9):5556–63. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillon SC, Zhang X, Trievel RC, Cheng X. The SET-domain protein superfamily: protein lysine methyltransferases. Genome Biol. 2005;6(8):227. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-227. doi:10.1186/gb-2005-6-8-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gyory I, Wu J, Fejer G, Seto E, Wright KL. PRDI-BF1 recruits the histone H3 methyltransferase G9a in transcriptional silencing. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(3):299–308. doi: 10.1038/ni1046. doi:10.1038/ni1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ancelin K, Lange UC, Hajkova P, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T, et al. Blimp1 associates with Prmt5 and directs histone arginine methylation in mouse germ cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(6):623–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb1413. doi:10.1038/ncb1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin HM, Kapoor VN, Guan T, Kaech SM, Welsh RM, Berg LJ. Epigenetic modifications induced by Blimp-1 Regulate CD8(+) T cell memory progression during acute virus infection. Immunity. 2013;39(4):661–75. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.032. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savitsky D, Calame K. B-1 B lymphocytes require Blimp-1 for immunoglobulin secretion. J Exp Med. 2006;203(10):2305–14. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060411. doi:10.1084/jem.20060411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schliephake DE, Schimpl A. Blimp-1 overcomes the block in IgM secretion in lipopolysaccharide/anti-mu F(ab’)2-co-stimulated B lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26(1):268–71. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260142. doi:10.1002/eji.1830260142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genestier L, Taillardet M, Mondiere P, Gheit H, Bella C, Defrance T. TLR agonists selectively promote terminal plasma cell differentiation of B cell subsets specialized in thymus-independent responses. J Immunol. 2007;178(12):7779–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capolunghi F, Cascioli S, Giorda E, Rosado MM, Plebani A, Auriti C, et al. CpG drives human transitional B cells to terminal differentiation and production of natural antibodies. J Immunol. 2008;180(2):800–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghamlouch H, Ouled-Haddou H, Guyart A, Regnier A, Trudel S, Claisse JF, et al. TLR9 ligand (CpG oligodeoxynucleotide) induces CLL B-cells to differentiate into CD20(+) antibody-secreting cells. Front Immunol. 2014;5:292. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00292. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li FJ, Schreeder DM, Li R, Wu J, Davis RS. FCRL3 promotes TLR9-induced B-cell activation and suppresses plasma cell differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43(11):2980–92. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243068. doi:10.1002/eji.201243068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong D, Malek TR. Cytokine-dependent Blimp-1 expression in activated T cells inhibits IL-2 production. J Immunol. 2007;178(1):242–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen-Kiang S. Regulation of terminal differentiation of human B-cells by IL-6. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;194:189–98. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79275-5_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozaki K, Spolski R, Ettinger R, Kim HP, Wang G, Qi CF, et al. Regulation of B cell differentiation and plasma cell generation by IL-21, a novel inducer of Blimp-1 and Bcl-6. J Immunol. 2004;173(9):5361–71. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rousset F, Garcia E, Defrance T, Peronne C, Vezzio N, Hsu DH, et al. Interleukin 10 is a potent growth and differentiation factor for activated human B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(5):1890–3. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vasanwala FH, Kusam S, Toney LM, Dent AL. Repression of AP-1 function: a mechanism for the regulation of Blimp-1 expression and B lymphocyte differentiation by the B cell lymphoma-6 protooncogene. J Immunol. 2002;169(4):1922–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohkubo Y, Arima M, Arguni E, Okada S, Yamashita K, Asari S, et al. A role for c-fos/activator protein 1 in B lymphocyte terminal differentiation. J Immunol. 2005;174(12):7703–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittrucker HW, Matsuyama T, Grossman A, Kundig TM, Potter J, Shahinian A, et al. Requirement for the transcription factor LSIRF/IRF4 for mature B and T lymphocyte function. Science. 1997;275(5299):540–3. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5299.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sciammas R, Shaffer AL, Schatz JH, Zhao H, Staudt LM, Singh H. Graded expression of interferon regulatory factor-4 coordinates isotype switching with plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2006;25(2):225–36. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.009. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng Y, Tsao BP. Genetic susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus in the genomic era. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6(12):683–92. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.176. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barcellos LF, May SL, Ramsay PP, Quach HL, Lane JA, Nititham J, et al. High-density SNP screening of the major histo-compatibility complex in systemic lupus erythematosus demonstrates strong evidence for independent susceptibility regions. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(10):e1000696. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000696. doi:10.1371/journal. pgen.1000696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rioux JD, Goyette P, Vyse TJ, Hammarstrom L, Fernando MM, Green T, et al. Mapping of multiple susceptibility variants within the MHC region for 7 immune-mediated diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(44):18680–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909307106. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909307106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawasaki A, Furukawa H, Kondo Y, Ito S, Hayashi T, Kusaoi M, et al. TLR7 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the 3’ untranslated region and intron 2 independently contribute to systemic lupus erythematosus in Japanese women: a case-control association study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(2):R41. doi: 10.1186/ar3277. doi:10.1186/ar3277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niewold TB, Kelly JA, Flesch MH, Espinoza LR, Harley JB, Crow MK. Association of the IRF5 risk haplotype with high serum interferon-alpha activity in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(8):2481–7. doi: 10.1002/art.23613. doi:10.1002/art.23613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abelson AK, Delgado-Vega AM, Kozyrev SV, Sanchez E, Velazquez-Cruz R, Eriksson N, et al. STAT4 associates with systemic lupus erythematosus through two independent effects that correlate with gene expression and act additively with IRF5 to increase risk. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(11):1746–53. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.097642. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.097642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob CO, Zhu J, Armstrong DL, Yan M, Han J, Zhou XJ, et al. Identification of IRAK1 as a risk gene with critical role in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(15):6256–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901181106. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901181106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adrianto I, Wen F, Templeton A, Wiley G, King JB, Lessard CJ, et al. Association of a functional variant downstream of TNFAIP3 with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2011;43(3):253–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.766. doi:10.1038/ng.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu H, Cantor RM, Graham DS, Lingren CM, Farwell L, Jager PL, et al. Association analysis of the R620W polymorphism of protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22 in systemic lupus erythematosus families: increased T allele frequency in systemic lupus erythematosus patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(8):2396–402. doi: 10.1002/art.21223. doi:10.1002/art.21223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu JL, Zhang FY, Liang YH, Xiao FL, Zhang SQ, Cheng YL, et al. Association between the PD1.3A/G polymorphism of the PDCD1 gene and systemic lupus erythematosus in European populations: a meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(4):425–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03087.x. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu R, Vidal GS, Kelly JA, Delgado-Vega AM, Howard XK, Macwana SR, et al. Genetic associations of LYN with systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes Immun. 2009;10(5):397–403. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.19. doi:10.1038/gene.2009.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simpfendorfer KR, Olsson LM, Manjarrez Orduno N, Khalili H, Simeone AM, Katz MS, et al. The autoimmunity-associated BLK haplotype exhibits cis-regulatory effects on mRNA and protein expression that are prominently observed in B cells early in development. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(17):3918–25. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds220. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hom G, Graham RR, Modrek B, Taylor KE, Ortmann W, Garnier S, et al. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(9):900–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0707865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Radanova M, Vasilev V, Dimitrov T, Deliyska B, Ikonomov V, Ivanova D. Association of rs172378 C1q gene cluster polymorphism with lupus nephritis in Bulgarian patients. Lupus. 2015;24(3):280–9. doi: 10.1177/0961203314555173. doi:10.1177/0961203314555173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karassa FB, Trikalinos TA, Ioannidis JP. Role of the Fcgamma receptor IIa polymorphism in susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(6):1563–71. doi: 10.1002/art.10306. doi:10.1002/art.10306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jonsen A, Gunnarsson I, Gullstrand B, Svenungsson E, Bengtsson AA, Nived O, et al. Association between SLE nephritis and polymorphic variants of the CRP and FcgammaRIIIa genes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(9):1417–21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem167. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kem167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X, Wu J, Carter RH, Edberg JC, Su K, Cooper GS, et al. A novel polymorphism in the Fcgamma receptor IIB (CD32B) transmembrane region alters receptor signaling. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(11):3242–52. doi: 10.1002/art.11313. doi:10.1002/art.11313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen JY, Wang CM, Ma CC, Luo SF, Edberg JC, Kimberly RP, et al. Association of a transmembrane polymorphism of Fcgamma receptor IIb (FCGR2B) with systemic lupus erythematosus in Taiwanese patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(12):3908–17. doi: 10.1002/art.22220. doi:10.1002/art.22220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fan Y, Li LH, Pan HF, Tao JH, Sun ZQ, Ye DQ. Association of ITGAM polymorphism with systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(3):271–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03776.x. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toller-Kawahisa JE, Vigato-Ferreira IC, Pancoto JA, Mendes-Junior CT, Martinez EZ, Palomino GM, et al. The variant of CD11b, rs1143679 within ITGAM, is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus and clinical manifestations in Brazilian patients. Hum Immunol. 2014;75(2):119–23. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2013.11.013. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gateva V, Sandling JK, Hom G, Taylor KE, Chung SA, Sun X, et al. A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41(11):1228–33. doi: 10.1038/ng.468. doi:10.1038/ng.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Han JW, Zheng HF, Cui Y, Sun LD, Ye DQ, Hu Z, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2009;41(11):1234–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. doi:10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou XJ, Lu XL, Lv JC, Yang HZ, Qin LX, Zhao MH, et al. Genetic association of PRDM1-ATG5 intergenic region and autophagy with systemic lupus erythematosus in a Chinese population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(7):1330–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.140111. doi:10.1136/ard.2010.140111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franke A, McGovern DP, Barrett JC, Wang K, Radford-Smith GL, Ahmad T, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42(12):1118–25. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. doi:10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martins G, Calame K. Regulation and functions of Blimp-1 in T and B lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:133–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090241. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang DH, Angelin-Duclos C, Calame K. BLIMP-1: trigger for differentiation of myeloid lineage. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(2):169–76. doi: 10.1038/77861. doi:10.1038/77861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iwakoshi NN, Pypaert M, Glimcher LH. The transcription factor XBP-1 is essential for the development and survival of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204(10):2267–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070525. doi:10.1084/jem.20070525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shaffer AL, Shapiro-Shelef M, Iwakoshi NN, Lee AH, Qian SB, Zhao H, et al. XBP1, downstream of Blimp-1, expands the secretory apparatus and other organelles, and increases protein synthesis in plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2004;21(1):81–93. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.010. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim SJ, Zou YR, Goldstein J, Reizis B, Diamond B. Tolerogenic function of Blimp-1 in dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208(11):2193–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110658. doi:10.1084/jem.20110658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, Yang XO, Kang HS, Ma L, et al. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29(1):138–49. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poholek AC, Hansen K, Hernandez SG, Eto D, Chandele A, Weinstein JS, et al. In vivo regulation of Bcl6 and T follicular helper cell development. J Immunol. 2010;185(1):313–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904023. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0904023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi YS, Eto D, Yang JA, Lao C, Crotty S. Cutting edge: STAT1 is required for IL-6-mediated Bcl6 induction for early follicular helper cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2013;190(7):3049–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203032. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1203032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim SJ, Gregersen PK, Diamond B. Regulation of dendritic cell activation by microRNA let-7c and BLIMP1. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(2):823–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI64712. doi:10.1172/JCI64712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salehi S, Bankoti R, Benevides L, Willen J, Couse M, Silva JS, et al. B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein-1 contributes to intestinal mucosa homeostasis by limiting the number of IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2012;189(12):5682–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201966. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1201966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491(7422):119–24. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. doi:10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Watchmaker PB, Lahl K, Lee M, Baumjohann D, Morton J, Kim SJ, et al. Comparative transcriptional and functional profiling defines conserved programs of intestinal DC differentiation in humans and mice. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(1):98–108. doi: 10.1038/ni.2768. doi:10.1038/ni.2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim SJ, Goldstein J, Dorso K, Merad M, Mayer L, Crawford JM, et al. Expression of Blimp-1 in dendritic cells modulates the innate inflammatory response in dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis. Mol Med. 2014;20:707–19. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00231. doi:10.2119/molmed.2014.00231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bianchi V, Maconi G, Ardizzone S, Colombo E, Ferrara E, Russo A, et al. Association of NOD2/CARD15 mutations on Crohn's disease phenotype in an Italian population. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19(3):217–23. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000250590.84102.12. doi:10.1097/01.meg.0000250590.84102.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Piskurich JF, Lin KI, Lin Y, Wang Y, Ting JP, Calame K. BLIMP-I mediates extinction of major histocompatibility class II transactivator expression in plasma cells. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(6):526–32. doi: 10.1038/82788. doi:10.1038/82788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Smith MA, Wright G, Wu J, Tailor P, Ozato K, Chen X, et al. Positive regulatory domain I (PRDM1) and IRF8/PU.1 counter-regulate MHC class II transactivator (CIITA) expression during dendritic cell maturation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(10):7893–904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.165431. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.165431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.VanderLugt B, Khan AA, Hackney JA, Agrawal S, Lesch J, Zhou M, et al. Transcriptional programming of dendritic cells for enhanced MHC class II antigen presentation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(2):161–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.2795. doi:10.1038/ni.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cretney E, Xin A, Shi W, Minnich M, Masson F, Miasari M, et al. The transcription factors Blimp-1 and IRF4 jointly control the differentiation and function of effector regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(4):304–11. doi: 10.1038/ni.2006. doi:10.1038/ni.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vinuesa CG, Cook MC, Angelucci C, Athanasopoulos V, Rui L, Hill KM, et al. A RING-type ubiquitin ligase family member required to repress follicular helper T cells and autoimmunity. Nature. 2005;435(7041):452–8. doi: 10.1038/nature03555. doi:10.1038/nature03555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arce E, Jackson DG, Gill MA, Bennett LB, Banchereau J, Pascual V. Increased frequency of pre-germinal center B cells and plasma cell precursors in the blood of children with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2001;167(4):2361–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ansel KM, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Ngo VN, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Cyster JG. In vivo-activated CD4 T cells upregulate CXC chemokine receptor 5 and reprogram their response to lymphoid chemokines. J Exp Med. 1999;190(8):1123–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.8.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kitano M, Moriyama S, Ando Y, Hikida M, Mori Y, Kurosaki T, et al. Bcl6 protein expression shapes pre-germinal center B cell dynamics and follicular helper T cell heterogeneity. Immunity. 2011;34(6):961–72. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.025. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haynes NM, Allen CD, Lesley R, Ansel KM, Killeen N, Cyster JG. Role of CXCR5 and CCR7 in follicular Th cell positioning and appearance of a programmed cell death gene-1high germinal center-associated subpopulation. J Immunol. 2007;179(8):5099–108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmitt N, Liu Y, Bentebibel SE, Munagala I, Bourdery L, Venuprasad K, et al. The cytokine TGF-beta co-opts signaling via STAT3–STAT4 to promote the differentiation of human TFH cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(9):856–65. doi: 10.1038/ni.2947. doi:10.1038/ni.2947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shi GP, Munger JS, Meara JP, Rich DH, Chapman HA. Molecular cloning and expression of human alveolar macrophage cathepsin S, an elastinolytic cysteine protease. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(11):7258–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Riese RJ, Wolf PR, Bromme D, Natkin LR, Villadangos JA, Ploegh HL, et al. Essential role for cathepsin S in MHC class II-associated invariant chain processing and peptide loading. Immunity. 1996;4(4):357–66. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hsieh CS, deRoos P, Honey K, Beers C, Rudensky AY. A role for cathepsin L and cathepsin S in peptide generation for MHC class II presentation. J Immunol. 2002;168(6):2618–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fazilleau N, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Rosen H, McHeyzer-Williams MG. The function of follicular helper T cells is regulated by the strength of T cell antigen receptor binding. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(4):375–84. doi: 10.1038/ni.1704. doi:10.1038/ni.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang H, Kala M, Scott BG, Goluszko E, Chapman HA, Chris-tadoss P. Cathepsin S is required for murine autoimmune myasthenia gravis pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2005;174(3):1729–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakagawa TY, Brissette WH, Lira PD, Griffiths RJ, Petrushova N, Stock J, et al. Impaired invariant chain degradation and antigen presentation and diminished collagen-induced arthritis in cathepsin S null mice. Immunity. 1999;10(2):207–17. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saegusa K, Ishimaru N, Yanagi K, Arakaki R, Ogawa K, Saito I, et al. Cathepsin S inhibitor prevents autoantigen presentation and autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(3):361–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI14682. doi:10.1172/JCI14682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rupanagudi KV, Kulkarni OP, Lichtnekert J, Darisipudi MN, Mulay SR, Schott B, et al. Cathepsin S inhibition suppresses systemic lupus erythematosus and lupus nephritis because cathepsin S is essential for MHC class II-mediated CD4 T cell and B cell priming. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):452–63. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203717. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]