Abstract

Background

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs) serve a significant role in the pathogenesis of a variety of cardiovascular diseases. The transcriptional regulation of miRNAs is poorly understood in cardiac hypertrophy. We investigated whether the expression of miR-133a is epigenetically regulated by Class I and IIb HDACs during hypertrophic remodeling.

Methods and Results

Transverse aortic constriction (TAC) was performed in CD1 mice to induce pressure overload (PO) hypertrophy. Mice were treated with Class I and IIb HDAC inhibitor via drinking water for 2 and 4 weeks post-TAC. miRNA expression was determined by real time PCR. Echocardiography was performed at baseline and post-TAC endpoints for structural and functional assessment. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was used to identify HDACs and transcription factors associated with miR-133a promoter. miR-133a expression was downregulated by 0.7 and 0.5 fold at 2 weeks and 4 weeks post-TAC respectively as compared to vehicle-control (P < 0.05). HDAC inhibition prevented this significant decrease 2 weeks post-TAC and maintained miR-133a expression near vehicle-control levels, which coincided with 1) a decrease in connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) expression, 2) a reduction in cardiac fibrosis and left atrium diameter (marker of end-diastolic pressure) suggesting an improvement in diastolic function. ChIP analysis revealed that HDAC1 and HDAC2 are present on the miR-133a enhancer regions.

Conclusions

The results reveal that HDACs play a role in the regulation of PO-induced miR-133a downregulation. This work is the first to provide insight into an epigenetic-miRNA regulatory pathway in PO-induced cardiac fibrosis.

Keywords: microRNA, epigenetics, hypertrophy/remodeling, transcription regulation, HDAC, miR-133a

The left ventricle (LV) undergoes hypertrophic remodeling in response to chronic PO, a condition initiated by arterial hypertension or aortic stenosis that frequently leads to the development of chronic heart failure1. Although the mechanisms by which PO leads to hypertrophic remodeling have not been completely defined, changes in miRNA expression makes an important contribution2, 3. In particular, miR-133a is abundantly expressed in the heart and plays a critical role in hypertrophy; miR-133a is downregulated in the LV and atria in multiple murine models of cardiac hypertrophy4, 5, in dilated atria from patients with mitral stenosis, and in ventricles from young patients suffering from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy4.

In PO-induced remodeling, the myocardium is subjected to important modifications of the extracellular matrix (ECM) resulting in myocardial fibrosis. Key proteins in this process are serum response factor (SRF), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) and collagen type 1 (COL1a1), all of which are post-transcriptionally regulated by miR-133a6–9. Thus, when miR-133a is downregulated during cardiac hypertrophy and LV dilation, these pro-hypertrophic and pro-fibrotic factors are upregulated and contribute to the progression to heart failure.

Little is known about what regulates the PO-induced downregulation of miR-133a. Here we examine whether epigenetic regulators may play a role in miR-133a expression in PO hypertrophy. Histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and HDACs are the enzymes that carry out the addition and the removal respectively of the acetyl moiety on lysine residues of histone proteins10. HDAC inhibition reduced fibrosis in PO hypertrophy and blocked COL1a1 upregulation11. In addition, HDAC inhibitor treatment of rat neonatal cardiomyocytes upregulated miR-133a expression5. Therefore, we hypothesize that HDACs regulate miR-133a expression during PO hypertrophy and that Class I and IIb HDAC inhibition could attenuate pathological cardiac remodeling and improve cardiac function.

Methods

Transverse Aortic Constriction (TAC)

The methods used to create TAC-induced PO hypertrophy have been described previously12. All CD1 mice were between 11 and 17 wk of age at the time of TAC. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA also known as Vorinostat, cat# S1047, Selleck, Houston, TX) was dissolved in 5 M 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, in the drinking water (75 mg/kg/day)13. Mice were studied 2 weeks (n= 34, out of which 16 received SAHA), or 4 weeks (n= 29, out of which 15 received SAHA) post-TAC. Twenty six mice did not undergo TAC and served as controls (out of 26 mice, 10 received SAHA drug for 2 weeks). Vehicle water consisted of 5M 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, alone. All procedures performed were approved by the Institution Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical University of South Carolina in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines.

HDAC Activity Assay

HDAC activity was measured with the homogenous fluorescence release HDAC deacetylase assay as previously described14. AMC fluorescence was measured using Fluoroskan Ascent from Labsystems at excitation 355/emission 460 and background signals from pre-developed blanks were subtracted. The data were standardized using control, and the absolute deacetylated substrates were calculated based on the standard curve generated by non-acetylated AMC-KGL substrate under the same conditions.

RNA Isolation

Left ventricular myocardial tissue (30 to 50 mg) was place in RNAlater and then homogenized in QIAzol Lysis Reagent and total RNA (including miRNA and small RNA molecules) was purified with the miRNeasy Mini Kit (cat# 217004, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total and small RNA concentration was determined with “Agilent RNA 6000 Nano Kit” on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA).

microRNA Quantification

Using the Taqman microRNA Reverse Transcription Kit and Taqman microRNA Assays (Life Technologies), isolated RNA (10 ng) was reverse transcribed and expression level of mature miR-133a (assay ID: 002246, miR-133a-1 and miR-133a-2 combined) was determined using a CFX96 Real Time System/ C1000 thermal cycler (Biorad, Hercules, CA). The relative expression of miR-133a was calculated and normalized to the small nuclear RNA RNU6B (NC_000010.11, assay ID: 001093) using the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method15. Relative expression intensity values were calculated as 2−ΔCT, in which ΔCT are CT values normalized to the referent control RNU6B.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assays were performed as previously described16 with some modifications. 50 mg of heart tissue from specimen in each group was minced in cold PBS with PMSF, homogenized and cross-linked with formaldehyde (10 minutes). Cross-linking activity was quenched with the addition of glycine for 5 minutes then suspended in SDS lysis buffer and incubated on ice for 30 min. The cell lysates were sonicated for 6 cycles (10 seconds “on” 10 seconds “off”), and the cell debris was spun down. The supernatants were diluted with ChIP dilution buffer on a scale of 1:4 and used immediately for immunoprecipitation. Samples were pre-cleared with 30 µL of ChIP grade protein A/G Plus Agarose beads (Thermo Scientific, 26161) for 30 min at 4C. 10 µL from each IgG sample was saved at 4C for input controls. Antibody of interest was added according to the experimental design at a concentration of 5 µg per sample (Santa Cruz antibodies: HDAC1 (cat# sc7872), HDAC2 (cat# sc7899X), HDAC3 (cat# sc11417), SRF (cat# 13029). The proximal promoter for enhancer regions miR-133a1 and miR-133a2 were PCR amplified from the immunoprecipitated and non-immunoprecipitated (input control) chromatin using sense and antisense primers17 (Supplemental Table). Primers that amplified regions distal to the proximal promoter were also used as negative PCR controls.

Immunoblotting

LV myocardial samples were homogenized in lysis buffer and supernatant and pellet fractions for each sample run on SDS-PAGE and Western blotting was performed using CTGF antibody (1:2500, Abcam, cat# ab6992), acetylated histone H3 (Cell Signaling #9649), histone H3 (Millipore 06-755), acetylated α-Tubulin (Santa Cruz 23950) and α-Tubulin (Sigma, T9026). Band intensity was quantified using ImageJ 1.47t software (NIH, USA, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

Protein samples (5µg) from DCM cells (siRNA experiment) were run on 4–12% bis-tris gel and Western blotting was performed using HDAC2 antibody (Santa Cruz, cat# sc7899) and GAPDH (Fitzgerald Industries International, cat# 10R-G109a).

Echocardiography

Echocardiographic measurements were made using a 40 MHz mechanical scanning transducer (707B) and a Vevo 770 echocardiograph (VisualSonics, Toronto, Canada) as previously described18. LV weight (LVW), LV end-diastolic volume (LV EDV), LV ejection fraction (LV EF), body weight (BW), tibia length (TL) and left atrial (LA) diameter were measured using the American Society of Echocardiography criteria19. LV mass was normalized to body weight. The LA diameter was used to reflect chronic changes in LV diastolic pressure; diameter increases as a function of sustained increased pressure (i.e., an integration of pressure over time)20, 21.

Papillary Muscle Preparation and Passive Stiffness Measurements

Passive myocardium stiffness was assessed using isolated papillary muscles as previously described12, 22–25.

Collagen Content by Light Microscopy

The collagen content of the LV myocardium was determined by light microscopy as previously described12. Briefly, LV sections were stained with picrosirius red (PSR) to detect collagen fibers and were viewed with polarized light under dark field optics to detect birefringence of collagen fibers. Quantitative analysis of PSR-stained images captured with polarized light was performed. Five fields chosen at random from each mouse were scanned with SigmaScan software. Fields with large blood vessels were excluded from the analysis. Areas examined were distributed throughout the myocardium from the subendocardium to the subepicardium and excluded the epicardial surface. Collagen volume fraction was calculated as the area stained by PSR divided by the total area of interest.

Myocardial Fibroblasts Cultures

Primary cultures of myocardial fibroblasts were established from LV myocardial biopsies (2 × 2 mm) from patients (n = 5) with end-stage non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) presenting for heart transplantation and from normal individuals (n=4) using a previously described outgrowth techniques26, 27. The protocols used in this study were reviewed and approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Review Board for Human Research (HR#8076, approval date 12-6-2013) before the initiation of this study. Previous studies have shown that adult myocardial fibroblasts retain pathological phenotype acquired in vivo through early passages in cell cultures26. Cells were treated with HDAC inhibitor SAHA at 10µM concentration for 24hrs with a refresher 1 hr prior to collection.

HDAC2 was silenced in the DCM cells using human HDAC2-siRNA (Life Technology, CA, cat# S6494 and control negative #1) along with lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (cat# 13778-150) and OptiMEM (cat# 11058-021). Once confluent, DCM cells were transfected with HDAC2-siRNA and scramble-siRNA (5uM) for 3 hrs. The media was then replaced with complete fibroblast growth media (PromoCell, cat# C23020) for 2 days. HDAC inhibitor SAHA (10uM) was added to the media 24 hrs and 1 hr prior to lifting cells. Cells were lifted with TripLE, pelleted and collected in sample buffer.

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 6 by GraphPad Software, Inc. was used for statistical analysis. We performed Kolmogorov-Smirnov analysis to test for normality. Additionally, when applicable, we used 1-way ANOVA (with Tukey post-test), 2-way ANOVA (with Bonferroni post-test), non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test (with Dunn’s multiple comparison post-test) for comparison of groups with 5 or less data points and unpaired t-tests when necessary to determine statistical significance. P-values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant. Values for all measurements were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

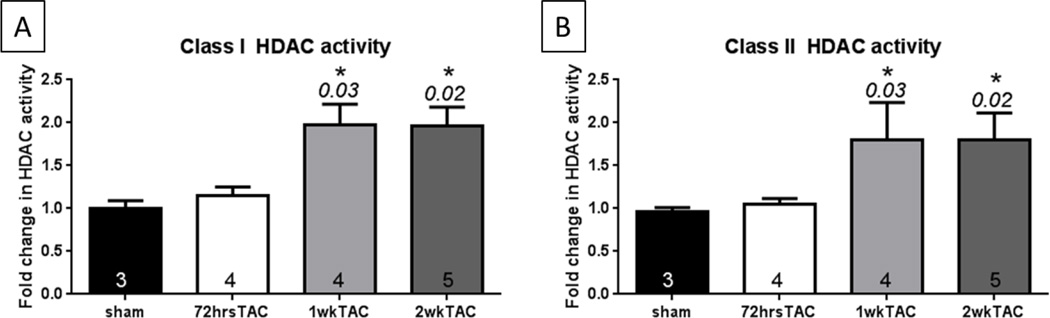

Class I and Class II HDAC activities during PO hypertrophy

The HDAC activity was assessed in homogenized tissue from the LV of outbred CD1 male mice 72 hrs, 1 week and 2 weeks post-TAC. As compared to sham mice, Class I HDAC activity increased by 97% and Class II HDAC activity increased by 79% at 1 week post-TAC (Figure 1A and 1B). Both Class I and Class II HDAC activities remained elevated at 2 weeks post-TAC. At 72 hrs post-TAC, Class I and II HDAC activities remained unchanged.

Figure 1. Levels of Class I and Class II HDAC activity in sham versus PO ventricles.

A) Class I HDAC activity, B) Class II HDAC activity. HDAC activity was analyzed in LV tissue of banded mice 72hrs, 1 week and 2 weeks post-TAC. * P ≤ 0.05 versus sham. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test P value equals 0.0007 and 0.0006 for Class I and Class II HDAC activity respectively. The Dunn’s multiple comparisons test P values are shown on the graph when close to or significant.

Effect of Class I and IIb HDAC inhibition on PO-induced downregulation of miR-133a

The expression of miR-133a was not significantly changed 1week post-TAC and SAHA treatment had no effect on miR-133a levels. miR-133a expression is significantly reduced 2 weeks and 4 weeks post-TAC (Figure 2A). SAHA prevented the PO-induced downregulation of miR-133a at 2 weeks post-TAC. The effect of HDAC inhibition on miR-133a expression is still evident at 4 weeks post-TAC but is not as profound as seen at 2 weeks. These findings suggest that class I and IIb HDACs regulate changes in miR-133a expression during PO-induced cardiac remodeling and fibrosis. miR-133a expression in control mice on vehicle and SAHA for 2 weeks were not significantly different suggesting that class I and IIb HDAC inhibition does not affect endogenous miR-133a expression levels in the normal myocardium. Increased acetylation level of histone H3 and α-tubulin which are known substrates for class I and IIb HDACs demonstrates that SAHA treatment effectively inhibited HDAC activity (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Effect of Class I and IIb HDAC inhibition on miR-133a expression levels, acetylated histone H3 and acetylated α-Tubulin abundance during PO hypertrophy.

A) miR-133a expression levels were quantified by RT-qPCR (normalized to RNU6B). Control mice received vehicle or SAHA for 2 weeks in drinking water. miR-133a expression was significantly downregulated 2 and 4 weeks post-TAC (white bars, * P ≤ 0.05 vs. vehicle-control, determined by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). HDAC inhibition prevented PO-induced miR-133a downregulation 2 weeks post-TAC (# P ≤ 0.05 vs. vehicle 2wkTAC determined by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons post-test). B) Global acetylation of histone H3 and α-tubulin was quantified by Western Blot in homogenized control and banded tissues (treated and untreated), and normalized to total histone H3 and total α-tubulin respectively.

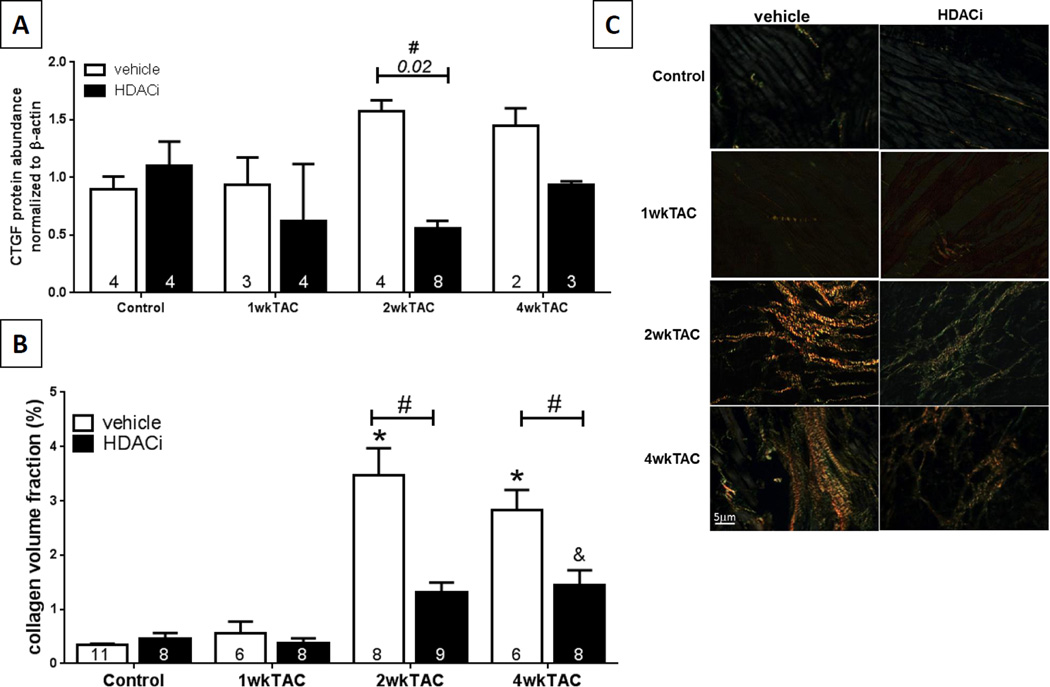

The effect of HDAC inhibition on miR-133a’s fibrotic targets and cardiac fibrosis

Many profibrotic genes are silenced by miR-133a, including CTGF7, 28 and Col1a16. Previous studies have shown that the pathological downregulation of miR-133a expression during PO cardiac remodeling allows CTGF and Col1a1 levels to increase, which contributes to collagen synthesis and fibrosis6, 7. To test if the restoration of miR-133a expression caused by HDAC inhibition impacts the expression of its profibrotic targets and the development of cardiac fibrosis, we measured CTGF protein levels and examined the extent of cardiac fibrosis with collagen volume fraction in the hearts of TAC mice after 1, 2 weeks and 4 weeks of PO cardiac remodeling. CTGF protein abundance was not significantly changed from control mice after 1 week of PO and HDAC inhibition had no significant effect on CTGF protein levels (Figure 3A). CTGF protein abundance increased by 75 % after 2 weeks of PO and 61 % after 4 weeks of PO (Figure 3C). HDAC inhibition prevented the PO-dependent increase in CTGF protein levels compared to vehicle at 2 weeks post-TAC. Although not significant, CTGF levels were still decreased compared to vehicle at 4 weeks post-TAC. Importantly, CTGF protein abundance in the HDACi treated mice after 2 and 4 weeks of PO were not significantly different from control+vehicle, suggesting that class I and IIb HDAC inhibition prevents the PO-dependent increase in CTGF abundance following TAC.

Figure 3. Impact of HDAC inhibition onto miR-133a’s targets and fibrosis.

A) Quantification of CTGF protein abundance (normalized to β-actin) 1, 2 and 4 weeks post-TAC surgery demonstrating the effect of HDAC inhibition on pressure overloaded hearts (# P ≤ 0.05 vs. 2wkTAC+vehicle determined by Kruskal Wallis (P = 0.0194) with Dunn’s multiple comparisons post-test). B) Collagen volume fraction was quantified from PSR-stained LV myocardium under polarized light microscopy. In the vehicle group (white bars), CVF was significantly increased 2 weeks and 4 weeks post-TAC (* P ≤ 0.05 vs. control+vehicle, determined by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). In the HDACi group, 1wkTAC and 2wkTAC are not significantly different from control, but 4wkTAC is (&P ≤ 0.05 vs control+HDACi). HDAC inhibition with SAHA significantly reduced collagen deposition at 2 weeks and 4 weeks post-TAC (# P ≤ 0.05 vs. 2wkTAC+vehicle and 4wkTAC+vehicle determined by 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons post-test). B) Images of PSR-stained LV myocardium under polarized light: larger collagen fibers are bright yellow or orange/red, and the thinner ones are green.

Myocardial interstitial collagen content was quantified using collagen volume fraction from Picrosirius red stained tissue sections. Collagen volume fraction was not changed at 1 week but was significantly increased after both 2 and 4 weeks of PO as compared to control (Figure 3B and 3C). This represents an increase in interstitial insoluble fibrillar collagen content. Inhibition of HDAC activity significantly reduced collagen deposition after 2 weeks and 4 weeks of PO when compared to vehicle alone.

The effect of HDAC inhibition on LV structure and function

To determine if the structure and the function of the myocardium were affected by HDAC inhibition, we examined several structural and functional parameters (Figure 4). The LA diameter (Figure 4A), LVW/BW (Figure 4B), LVW/TL (Figure 4C) and passive stiffness of the LV myocardium (Figure 4F) were significantly increased 2 weeks and 4 weeks post-TAC in vehicle treated mice as compared to baseline. HDAC inhibition significantly decreased the LA diameter (Figure 4A), and normalized the stiffness of myocardium 2 weeks and 4 weeks post-TAC as compared to baseline. However, HDAC inhibition had no effect on cardiac hypertrophy (LVW/BW, LVW/TL) and systolic function of the heart (LV EF in Figure 4D and LV EDV in Figure 4E).

Figure 4. Structural and functional assessment.

A, D, E) The LA diameter, LV EF and LV EDV were obtained based on echocardiograph data. B, C) BW, LVW and TL were measured 2 weeks and 4 weeks post-TAC. F) Passive stiffness of the LV myocardium. * P ≤ 0.05 vs. baseline. # P ≤ 0.05 vs. vehicle within same group.

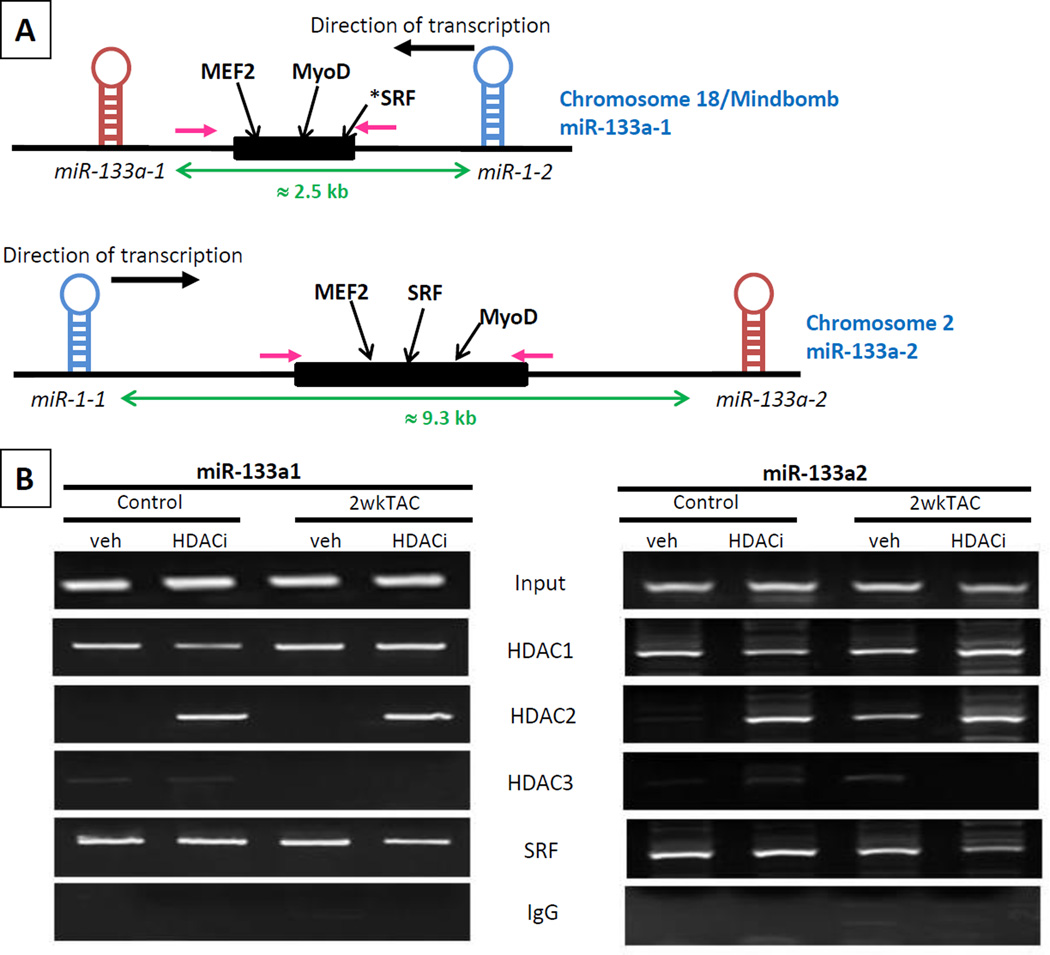

HDAC1 and HDAC2 are associated with miR-133a enhancer regions

miR-133a belongs to the miR-133a/133b family and is associated to the miR-1 family; miR-1-2/133a-1 and miR-1-1/133a-2 originate from bicistronic transcripts on chromosomes 18 and 2 respectively29 (Figure 5A). Enhancers regions have been identified regulating miR-133a-1 and miR-133a-2 expression. On chromosome 2, the intronic region between miR-1-1 and miR-133a-2 stem loops has an intragenic enhancer region regulated by SRF via CArG binding domains30, myocardin (MyoD) via E-box domains17, and myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) via the MEF2 box31. On chromosome 18, the intronic region between miR-133a-1 and miR-1-2 stem loops also has an intragenic enhancer region regulated by MEF2 and MyoD. Although miR-133a-1 and miR-1-2, and miR-133a-2 and miR-1-1 each share a common enhancer region, miR-133a can be differentially regulated from miR-15. Because there is increased evidence for the role of Class I HDACs in cardiac pathologies, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay for HDAC1, 2 and 3 on heart tissues from control and 2 weeks TAC mice32–35. Figure 5B shows that HDAC1 and the transcription factor SRF are present on both enhancer regions in all experimental conditions and that HDAC3 is not associated with either enhancer region under any of the conditions. HDAC2 is not present on either enhancer region in the untreated controls but is recruited to the miR-133a-2 enhancer region in the 2-week PO ventricles. Acetylation of histones is positively correlated with increased transcription. Therefore, if miR-133a transcriptional regulation is mediated primarily by histone acetylation we would predict the enhancer to have less acetylation in PO where miR-133a expression drops. But unexpectedly, histone H3 acetylation is greater in the 2-week post-TAC tissue when compared to control (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 5. miR-133a enhancer regions and regulation.

A) Two bicistronic gene clusters each encoding miR-1-2/133a-1 and miR-1-1/133a-2 located on chromosome 18 and 2 respectively. Cis-regulatory elements that direct muscle-specific expression of each locus are indicated by black boxes and the transcription factors that act through these elements are shown with black arrows. The distance between the two bicistronic miRNAs is shown by green arrows, and the regions targeted by the ChIP primers with pink arrows. * denotes newly identified SRF-binding element. HDAC2 is present on miR-133a enhancer regions in association with the transcription factor SRF. B) Murine ventricular tissue samples were analyzed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) to determine whether endogenous Class I HDACs (HDAC1, HDAC2 and HDAC3) as well as SRF are associated with miR-133a enhancer regions (antibodies for HDACs and SRF from Santa Cruz). A negative control, using rabbit IgG as the precipitating antibody, was run to demonstrate the specificity of the ChIP assay. Input DNA from the samples before immunoprecipitation (IP) is also included as a positive control and loading control. Abbreviations: “veh” for vehicle, and “HDACi” for HDAC inhibitor

Effect of HDAC inhibition on miR-133a expression in cardiac fibroblasts from patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

Given the profound effect of HDAC inhibition on fibrotic gene expression in treated murine hearts and the anti-fibrotic profile of miR-133a, we investigated the effect of HDAC inhibition on miR-133a expression in cardiac fibroblasts isolated from DCM and normal patients. Consistent with our murine data, miR-133a is significantly lower in DCM fibroblasts as compared to normal fibroblasts (Figure 6A). Importantly, HDAC inhibition significantly stimulated miR-133a expression in DCM fibroblasts (Figure 6C) but had no effect on miR-133a expression in the normal fibroblasts (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Levels of miR-133a expression in cardiac fibroblasts from 5 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and 4 normal individuals.

Cells were treated with HDAC inhibitor SAHA at 10 µM for 24hrs. Data analyzed by unpaired t-test. A) Comparison between miR-133a expression level in normal and DCM cell lines (* P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal). B) Fold change in miR-133a expression between normal cells treated with HDAC inhibitor SAHA and untreated (* P ≤ 0.05 vs. normal). C) Fold change in miR-133a expression between DCM cells treated with HDAC inhibitor SAHA and untreated (* P ≤ 0.05 vs. DCM).

Effect of HDAC2 knockdown on miR-133a expression in DCM fibroblasts

Since HDAC2 is recruited to the miR-133a-2 enhancer region in the 2-week PO ventricles, we examined the effect of HDAC2 silencing using HDAC2-siRNA in the DCM cells. HDAC2-siRNA knocked down HDAC2 expression in the DCM cells compared to control siRNA (Figure 7A and 7B). HDAC2 knockdown did not result in the increase of miR-133a expression similar to that observed with HDAC inhibition (control+HDACi). But interestingly, HDAC2 knockdown prevented SAHA stimulated miR-133a expression indicating that although HDAC2 may not be required for miR-133a downregulation in DCM cells, its activity plays a role in the partial restoration of expression seen with HDAC inhibitor treatment.

Figure 7. HDAC2 knockdown by siRNA transfection in DCM fibroblasts.

A) Validation of HDAC2 knockdown: HDAC2 protein abundance normalized to GAPDH in cells transfected with scramble-siRNA, HDAC2-siRNA with and without HDAC inhibitor SAHA (*P ≤ 0.05 vs. control siRNA determined by Kruskal Wallis non-parametric analysis (P = 0.0714) with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. B) Image of HDAC2 Western Blot membrane. C) DCM cells were transfected with HDAC2-siRNA and control scramble-siRNA (5uM for 3 hrs) and treated with HDAC inhibitor SAHA (10uM for 24 hrs). SAHA increased miR-133a expression significantly (P = 0.0184) but HDAC2-siRNA did not, and the effect of SAHA was lost when combined with HDAC2-siRNA. * P ≤ 0.05 vs. control, determined by Kruskal Wallis non-parametric analysis (P = 0.0324) with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. The Dunn’s multiple comparisons test P values are shown on the graph when close to or significant.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the epigenetic regulation of miR-133a in the heart during PO-induced cardiac remodeling and fibrosis. We demonstrated 1) Class I and Class II HDAC activities are increased during PO remodeling. 2) Treatment with the Class I and Class IIb HDAC inhibitor SAHA significantly attenuated the PO-induced decrease in miR-133a expression (after 2 and 4 weeks of PO). 3) HDAC inhibition significantly diminished PO-induced upregulation of CTGF protein abundance and collagen deposition, suggesting that the effect of HDAC inhibition on miR-133a expression is reflected on its downstream fibrotic targets. 4) Importantly, the effect of HDAC inhibition on miR-133a expression is also correlated with a reduction in LA diameter and passive stiffness in TAC mice, suggesting improved diastolic function. 5) HDAC1 and HDAC2 are associated with miR-133a-1 and miR-133a-2 enhancer regions. 6) Consistent with what we see in the murine model, HDAC inhibition increased the depressed expression of miR-133a found in human fibroblast isolated from DCM patients. These data support the hypothesis that acetylation regulates the expression of miR-133a during PO cardiac fibrosis, and it is the first report of the direct association of HDAC1 and HDAC2 with miR-133a promoter by ChIP.

Importance and crosstalk of miRNAs and HDACs

MicroRNAs have been identified as central players in the pathogenesis of various cardiovascular diseases2. MicroRNAs can regulate the expression of many target genes; therefore the change in expression in one miRNA can impact the expression of entire gene networks contributing to complex pathological phenotypes. Recent reports have demonstrated that the expression pattern of many miRNAs shifts at the onset of cardiac diseases. Based on murine hypertrophic models, Van Rooij et al.36 identified 28 differentially expressed miRNAs and many of them were also pathologically regulated in human failing hearts. Of special interest, miR-133a is downregulated in the LV and atria in multiple murine models of PO-induced cardiac remodeling4, 5, is highly expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscle, and is one of the most highly expressed miRNA in cardiomyocytes (although it is also detectable in cardiac fibroblasts). Its expression is decreased as compared to normal in dilated atria from patients with mitral stenosis and in myectomies of ventricles from young patients undergoing curative surgery for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy4.

While the biogenesis of miRNAs is well understood, little is known about the regulation of miRNA expression. Interestingly, the miRNA expression profile from heart failure patients is highly similar to the profile of fetally expressed miRNAs37, in agreement with the reactivation of the fetal gene program during PO-induced cardiac remodeling38. Interestingly, HDAC inhibition suppresses the reactivation of several fetal genes in murine models of cardiac hypertrophy39. Increasing evidence shows that many miRNAs are regulated by epigenetic mechanisms. The majority of these are regulated by DNA methylation but histone modification can induce or suppress miRNA expression. Aberrant histone acetylation has been shown to affect miRNA expression in a variety of cancers including colorectal cancer40. HDAC inhibition alters the expression of miR-15a, miR-16 and miR-29 samples41. The expression of miR-15a/16 is epigenetically silenced in chronic lymphocytic leukemia via the recruitment of HDAC3 to the promoter by MYC42 and NF-B recruitment of HDAC4 silences miR-23 expression in human leukemic Jurkat cells43. Expression of anti-angiogenic miR-17-92 cluster in endothelial cells can be modulated by HDAC944. Not surprisingly, this works both ways. HDACs and HATs are among the targets of miRNAs. HDAC4 is targeted by miR-1-1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells and HDAC1 is regulated by miR-449a in prostate cancer cells45, 46.

Although the interplay between epigenetic regulators and miRNAs is beginning to be worked out in cancer, very little is known about this complex interaction in the heart. One recent paper examining the antagonisms between IP3RII and miR-133a demonstrated that treatment of rat neonatal cardiomyocytes with the pan-HDAC inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) results in the upregulation of miR-133a5. Intrigued by this observation and by studies showing that both restoring miR-133a levels and treatment with HDAC inhibitors suppress pathological cardiac remodeling and myocardial fibrosis, we examined the regulation of miR-133a by HDACs. Here we found that miR-133a is significantly downregulated 2 weeks and 4 weeks post-TAC, in agreement with previous studies, and made the novel discovery that HDAC inhibition prevented the PO-induced downregulation of miR-133a expression. Interestingly, SAHA treatment in animals that did not receive TAC did not result in any increase in the basal level of miR-133a. Drawnel et al.5 found that TSA treatment induced miR-133a expression by 80%. This discrepancy may be due to the difference of an in vitro response in rat neonatal ventricular myocytes verses our study in an in vivo mouse heart. Our results show that HDAC inhibition had an impact only on the pathological expression of miR-133a in the TAC mice and restored basal levels. Importantly, the restoration of miR-133a levels prevented the increase in CTGF protein content and CVF. It is noteworthy that the increase in HDAC activity seen in this study at 1-week post-TAC did not result in the downregulation of miR-133a yet inhibition of HDAC activity at 2 and 4 weeks post-TAC results in restoration of miR-133a to control levels. These data suggest that other factors are also required. Therefore, HDAC activity is required but not sufficient for repression of miR-133a expression. Identification of additional co-repressor(s) and determining the role of class I HDACs in the regulation of miR-133a needs further evaluation. Previous studies have demonstrated that class I and IIb HDACs can mediate the expression of many other genes which contribute to cardiac pathologies39. Therefore, SAHA treatment would be expected to impact the expression of many other genes in addition to miR-133a that contribute in one way or another to PO cardiac remodeling and fibrosis. Identifying these additional targets, which contribute to fibrosis, awaits further evaluation.

HDAC1 and HDAC2 are present on miR-133a enhancer regions

The present study is the first to demonstrate the association of HDAC1 and HDAC2 with the miR-133a-1 and miR-133a-2 enhancer regions. While HDAC1’s association with the miR-133a enhancer regions is similar in the control and pressure overloaded heart, HDAC2 is recruited to the miR-133a-2 enhancer region in the pressure overloaded ventricle. Overexpression of HDAC2 induces hypertrophy35. HDAC2 null mice generated by cardiac-conditional knockout remain susceptible to isoproterenol and PO-induced cardiac hypertrophy47, whereas HDAC2 null mice generated by lacZ insertion resist hypertrophic remodeling induced by PO stress35. Kee et al.48 found that induction of HSP70 in response to exogenous hypertrophic stimuli is a key regulatory mechanism to activate HDAC2 in the early phase of cardiac hypertrophy and concluded that HDAC2 is required for hypertrophic responses in the heart.

In order to better understand the role of HDAC2 in miR-133a regulation in an in vitro setting, we utilized siRNA knockdown in the human DCM cells. HDAC2 knockdown did not result in miR-133a upregulation. These data were not completely unexpected. HDAC1 and HDAC2 are recruited by transcription factors either as homo- or heterodimers or as part of multifactor repressor complexes49. Although HDAC1 and HDAC2 have some distinctive deacetylase targets50, the common theme of many HDAC1/HDAC2 knockdown and knockout studies is redundancy and compensation51–53. In addition HDAC knockdown may exert a completely different effect than inhibiting its catalytic activity54. This may be the case for miR-133a regulation, HDAC1 may be able to compensate for the loss of HDAC2 but in this case inhibition of HDAC activity did not result in the stimulation of miR-133a expression.

We had expected to find a class I HDAC present after TAC and indeed there is more HDAC2 detected on miR-133a-2 enhancer with TAC than in control hearts. But we anticipated that treatment with SAHA would reduce the presence of HDACs on the enhancer chromatin. Our finding that HDAC inhibition enhanced the stabilization of HDAC2 with the miR-133a enhancer chromatin in control and TAC mice was unexpected. Importantly, even though more HDAC2 is present on the miR-133a enhancer, SAHA treatment inhibits the deacetylase activity. This is not the first observation showing that in addition to inhibiting enzymatic activity, HDAC inhibitors can also stabilize HDAC repressor complexes. Nebbioso et. al demonstrated that treatment with the HDAC inhibitor MC1568 stabilizes the interaction of MEF2 with the HDAC4-NCOR-HDAC3 repressor complex55. Both their findings and ours suggest that HDAC inhibitors can impact molecular mechanisms beyond inhibiting catalytic activity. Because SAHA treatment with TAC prevents miR-133a downregulation, we assume that stabilization of the co-repressor complex does not hinder the recruitment of co-activators, such as HATs to the miR-133a enhancer.

Acetylation of lysine residues in the N-termini of histones correlates with increased transcription and heterochromatic regions are generally hypoacetylated. Our data are contrary to simple histone deacetylation as a major factor accounting for the repression of miR-133a expression in PO hypertrophy. It is possible that HDAC2 regulates miR-133a expression by the deacetylation of or interaction with transcription factors, co-activators or co-repressors on the miR-133a enhancer. SRF and MEF2 have been shown to play a role in cardiac expression of miR-133a-1 and miR-133a-230, 31. We identified the presence of an additional SRF binding (CArG) element between miR-1-2 and miR-133a-1 (Figure 5 and Supplemental Figure 2). Both SRF and MEF2 have been shown to undergo acetylation that may affect their activity or interaction with positive or negative cofactors56, 57. HOP is one of SRF’s co-factor that inhibits SRF transcriptional activity by recruiting a co-repressor complex that includes HDAC258. Clearly much work remains to identify the exact mechanism by which HDACs regulate miR-133a expression in PO cardiac remodeling and fibrosis.

In conclusion, this is the first study focused on the complex interaction between miRNAs and epigenetic regulators in heart disease. Certainly, there is a need to better understand the mechanisms of epigenetic regulation of miRNAs. The potential of HDAC inhibitors and other epigenetic drugs to induce or repress the deregulated miRNAs may provide innovative therapies to reset the epigenome in heart disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Amy Bradshaw and Dr. Jessica E Silva for training and use of their facility to embed/process tissue for Picrosirius red staining, polarized imaging and software analysis for collagen volume fraction quantification, and Dr. Paul Nietert for his advices regarding statistical analysis.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01HL094545 (DRM), R56HL123478 (MRZ), R01HL123478 (MRZ), UL1TR000062 (DRM)) through the Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, by Postdoctoral Fellowship (T32HL07260 (LGH)), and by United States Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Reviews (I01 BX002327 (DRM), I01 BX000904 (JAJ), 5101 CX000415-02 and 5101 BX000487-04 (MRZ)) through the Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development, and Clinical Sciences Research and Development Programs.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Leip EP, Beiser A, D’Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Murabito JM, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Lifetime Risk for Developing Congestive Heart Failure: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2002;106:3068–3072. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039105.49749.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Small EM, Frost RJA, Olson EN. MicroRNAs Add a New Dimension to Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2010;121:1022–1032. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.889048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang C. MicroRNAs: role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Clinical Science. 2008;114:699–706. doi: 10.1042/CS20070211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, Bang M-L, Segnalini P, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Elia L, Latronico MVG, Hoydal M, Autore C, Russo MA, Dorn GW, Ellingsen O, Ruiz-Lozano P, Peterson KL, Croce CM, Peschle C, Condorelli G. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nature medicine. 2007;13:613–618. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drawnel FM, Wachten D, Molkentin JD, Maillet M, Aronsen JM, Swift F, Sjaastad I, Liu N, Catalucci D, Mikoshiba K, Hisatsune C, Okkenhaug H, Andrews SR, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Mutual antagonism between IP3RII and miRNA-133a regulates calcium signals and cardiac hypertrophy. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;199:783–798. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201111095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castoldi G, Di Gioia CR, Bombardi C, Catalucci D, Corradi B, Gualazzi MG, Leopizzi M, Mancini M, Zerbini G, Condorelli G, Stella A. MiR-133a regulates collagen 1A1: potential role of miR-133a in myocardial fibrosis in angiotensin II-dependent hypertension. Journal of cellular physiology. 2012;227:850–856. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duisters RF, Tijsen AJ, Schroen B, Leenders JJ, Lentink V, van der Made I, Herias V, van Leeuwen RE, Schellings MW, Barenbrug P, Maessen JG, Heymans S, Pinto YM, Creemers EE. miR-133 and miR-30 Regulate Connective Tissue Growth Factor. Circulation Research. 2009;104:170–178. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu N, Bezprozvannaya S, Williams AH, Qi X, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. microRNA-133a regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and suppresses smooth muscle gene expression in the heart. Genes and Development. 2008;22:3242–3254. doi: 10.1101/gad.1738708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu M, Wang YZ. miR133a suppresses cell proliferation, migration and invasion in human lung cancer by targeting MMP14. Oncology reports. 2013;30:1398–1404. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang XJ, Seto E. HATs and HDACs: from structure, function and regulation to novel strategies for therapy and prevention. Oncogene. 2007;26:5310–5318. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong Y, Tannous P, Lu G, Berenji K, Rothermel BA, Olson EN, Hill JA. Suppression of Class I and II Histone Deacetylases Blunts Pressure-Overload Cardiac Hypertrophy. Circulation. 2006;113:2579–2588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.625467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bradshaw AD, Baicu CF, Rentz TJ, Van Laer AO, Boggs J, Lacy JM, Zile MR. Pressure overload-induced alterations in fibrillar collagen content and myocardial diastolic function: role of secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC) in post-synthetic procollagen processing. Circulation. 2009;119:269–280. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.773424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hockly E, Richon VM, Woodman B, Smith DL, Zhou X, Rosa E, Sathasivam K, Ghazi-Noori S, Mahal A, Lowden PA, Steffan JS, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Lewis CM, Marks PA, Bates GP. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, ameliorates motor deficits in a mouse model of Huntington's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2041–2046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inks ES, Josey BJ, Jesinkey SR, Chou CJ. A novel class of small molecule inhibitors of HDAC6. ACS chemical biology. 2012;7:331–339. doi: 10.1021/cb200134p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramaswami S, Manna S, Juvekar A, Kennedy S, Vancura A, Vancurova I. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Analysis of NFκB Transcriptional Regulation by Nuclear IκBα in Human Macrophages. In: Vancura A, editor. Transcriptional Regulation. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 121–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao PK, Kumar RM, Farkhondeh M, Baskerville S, Lodish HF. Myogenic factors that regulate expression of muscle-specific microRNAs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:8721–8726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602831103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zile MR, Baicu CF, Stroud RE, Van Laer A, Arroyo J, Mukherjee R, Jones JA, Spinale FG. Pressure overload-dependent membrane type 1-matrix metalloproteinase induction: relationship to LV remodeling and fibrosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1429–H1437. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00580.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ Chamber Quantification Writing G, American Society of Echocardiography's G, Standards C and European Association of E. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borlaug BA, Jaber WA, Ommen SR, Lam CS, Redfield MM, Nishimura RA. Diastolic relaxation and compliance reserve during dynamic exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart. 2011;97:964–969. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.212787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam CS, Roger VL, Rodeheffer RJ, Bursi F, Borlaug BA, Ommen SR, Kass DA, Redfield MM. Cardiac structure and ventricular-vascular function in persons with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Circulation. 2007;115:1982–1990. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishibashi Y, Takahashi M, Isomatsu Y, Qiao F, Iijima Y, Shiraishi H, Simsic JM, Baicu CF, Robbins J, Zile MR, Cooper Gt. Role of microtubules versus myosin heavy chain isoforms in contractile dysfunction of hypertrophied murine cardiocytes. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2003;285:H1270–H1285. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00654.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly RP, Ting CT, Yang TM, Liu CP, Maughan WL, Chang MS, Kass DA. Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation. 1992;86:513–521. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Hagaman JR, Smithies O. A noninvasive computerized tail-cuff system for measuring blood pressure in mice. Hypertension. 1995;25:1111–1115. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.5.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim CC, Apstein CS, Colucci WS, Liao R. Impaired cell shortening and relengthening with increased pacing frequency are intrinsic to the senescent mouse cardiomyocyte. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2000;32:2075–2082. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flack EC, Lindsey ML, Squires CE, Kaplan BS, Stroud RE, Clark LL, Escobar PG, Yarbrough WM, Spinale FG. Alterations in cultured myocardial fibroblast function following the development of left ventricular failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:474–483. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spruill LS, Lowry AS, Stroud RE, Squires CE, Mains IM, Flack EC, Beck C, Ikonomidis JS, Crumbley AJ, McDermott PJ, Spinale FG. Membrane-type-1 matrix metalloproteinase transcription and translation in myocardial fibroblasts from patients with normal left ventricular function and from patients with cardiomyopathy. American journal of physiology Cell physiology. 2007;293:C1362–C1373. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00545.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daniels A, van Bilsen M, Goldschmeding R, van der Vusse GJ, van Nieuwenhoven FA. Connective tissue growth factor and cardiac fibrosis. Acta physiologica. 2009;195:321–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2008.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen JF. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nature Genetics. 2006;38:228–233. doi: 10.1038/ng1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao Y, Samal E, Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu N, Williams AH, Kim Y, McAnally J, Bezprozvannaya S, Sutherland LB, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. An intragenic MEF2-dependent enhancer directs muscle-specific expression of microRNAs 1 and 133. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:20844–20849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710558105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cavasin MA, Demos-Davies K, Horn TR, Walker LA, Lemon DD, Birdsey N, Weiser-Evans MC, Harral J, Irwin DC, Anwar A, Yeager ME, Li M, Watson PA, Nemenoff RA, Buttrick PM, Stenmark KR, McKinsey TA. Selective class I histone deacetylase inhibition suppresses hypoxia-induced cardiopulmonary remodeling through an antiproliferative mechanism. Circulation Research. 2012;110:739–748. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mani SK, Kern CB, Addy B, Kasiganesan H, Rivers WT, Oliver RA, Spinale FG, Mukherjee R, Menick DR. Inhibition Of Histone Deacetylase Activity Represses Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Induction And Preserves Cardiac Function Post Myocardial Infarction. Circulation Journal. 2008;118:S-498. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samant SA, Courson DS, Sundaresan NR, Pillai VB, Tan M, Zhao Y, Shroff SG, Rock RS, Gupta MP. HDAC3-dependent reversible lysine acetylation of cardiac myosin heavy chain isoforms modulates their enzymatic and motor activity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:5567–5577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35.Trivedi CM, Luo Y, Yin Z, Zhang M, Zhu W, Wang T, Floss T, Goettlicher M, Noppinger PR, Wurst W, Ferrari VA, Abrams CS, Gruber PJ, Epstein JA. Hdac2 regulates the cardiac hypertrophic response by modulating Gsk3 beta activity. Nature medicine. 2007;13:324–331. doi: 10.1038/nm1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Liu N, Williams AH, McAnally J, Gerard RD, Richardson JA, Olson EN. A signature pattern of stress-responsive microRNAs that can evoke cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18255–18260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608791103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thum T, Galuppo P, Wolf C, Fiedler J, Kneitz S, van Laake LW, Doevendans PA, Mummery CL, Borlak J, Haverich A, Gross C, Engelhardt S, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. MicroRNAs in the human heart: a clue to fetal gene reprogramming in heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:258–267. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.687947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barry SP, Davidson SM, Townsend PA. Molecular regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2008;40:2023–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKinsey TA. Therapeutic potential for HDAC inhibitors in the heart. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2012;52:303–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bandres E, Agirre X, Bitarte N, Ramirez N, Zarate R, Roman-Gomez J, Prosper F, Garcia-Foncillas J. Epigenetic regulation of microRNA expression in colorectal cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2009;125:2737–2743. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sampath D, Liu C, Vasan K, Sulda M, Puduvalli VK, Wierda WG, Keating MJ. Histone deacetylases mediate the silencing of miR-15a, miR-16, and miR-29b in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;119:1162–1172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-351510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang X, Zhao X, Fiskus W, Lin J, Lwin T, Rao R, Zhang Y, Chan JC, Fu K, Marquez VE, Chen-Kiang S, Moscinski LC, Seto E, Dalton WS, Wright KL, Sotomayor E, Bhalla K, Tao J. Coordinated silencing of MYC-mediated miR-29 by HDAC3 and EZH2 as a therapeutic target of histone modification in aggressive B-Cell lymphomas. Cancer cell. 2012;22:506–523. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 43.Rathore MG, Saumet A, Rossi JF, de Bettignies C, Tempe D, Lecellier CH, Villalba M. The NF-kappaB member p65 controls glutamine metabolism through miR-23a. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2012;44:1448–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaluza D, Kroll J, Gesierich S, Manavski Y, Boeckel J-N, Doebele C, Zelent A, Rössig L, Zeiher AM, Augustin HG, Urbich C, Dimmeler S. Histone Deacetylase 9 Promotes Angiogenesis by Targeting the Antiangiogenic MicroRNA-17–92 Cluster in Endothelial Cells. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2013;33:533–543. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Datta J, Kutay H, Nasser MW, Nuovo GJ, Wang B, Majumder S, Liu CG, Volinia S, Croce CM, Schmittgen TD, Ghoshal K, Jacob ST. Methylation mediated silencing of MicroRNA-1 gene and its role in hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5049–5058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 46.Noonan EJ, Place RF, Pookot D, Basak S, Whitson JM, Hirata H, Giardina C, Dahiya R. miR-449a targets HDAC-1 and induces growth arrest in prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2009;28:1714–1724. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montgomery RL, Davis CA, Potthoff MJ, Haberland M, Fielitz J, Qi X, Hill JA, Richardson JA, Olson EN. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 redundantly regulate cardiac morphogenesis, growth, and contractility. Genes & development. 2007;21:1790–1802. doi: 10.1101/gad.1563807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kee HJ, Eom GH, Joung H, Shin S, Kim JR, Cho YK, Choe N, Sim BW, Jo D, Jeong MH, Kim KK, Seo JS, Kook H. Activation of histone deacetylase 2 by inducible heat shock protein 70 in cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2008;103:1259–1269. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000338570.27156.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jepsen K, Rosenfeld MG. Biological roles and mechanistic actions of co-repressor complexes. Journal of cell science. 2002;115:689–698. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lagger S, Meunier D, Mikula M, Brunmeir R, Schlederer M, Artaker M, Pusch O, Egger G, Hagelkruys A, Mikulits W, Weitzer G, Muellner EW, Susani M, Kenner L, Seiser C. Crucial function of histone deacetylase 1 for differentiation of teratomas in mice and humans. The EMBO journal. 2010;29:3992–4007. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jurkin J, Zupkovitz G, Lagger S, Grausenburger R, Hagelkruys A, Kenner L, Seiser C. Distinct and redundant functions of histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2 in proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cell cycle. 2011;10:406–412. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.3.14712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zimmermann S, Kiefer F, Prudenziati M, Spiller C, Hansen J, Floss T, Wurst W, Minucci S, Gottlicher M. Reduced body size and decreased intestinal tumor rates in HDAC2-mutant mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9047–9054. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamaguchi T, Cubizolles F, Zhang Y, Reichert N, Kohler H, Seiser C, Matthias P. Histone deacetylases 1 and 2 act in concert to promote the G1-to-S progression. Genes Dev. 2010;24:455–469. doi: 10.1101/gad.552310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun Z, Feng D, Fang B, Mullican Shannon E, You S-H, Lim H-W, Everett Logan J, Nabel Christopher S, Li Y, Selvakumaran V, Won K-J, Lazar Mitchell A. Deacetylase-Independent Function of HDAC3 in Transcription and Metabolism Requires Nuclear Receptor Corepressor. Molecular Cell. 2013;52:769–782. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nebbioso A, Manzo F, Miceli M, Conte M, Manente L, Baldi A, De Luca A, Rotili D, Valente S, Mai A, Usiello A, Gronemeyer H, Altucci L. Selective class II HDAC inhibitors impair myogenesis by modulating the stability and activity of HDAC-MEF2 complexes. EMBO reports. 2009;10:776–782. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang X, Azhar G, Helms S, Zhong Y, Wei JY. Identification of a subunit of NADH-dehydrogenase as a p49/STRAP-binding protein. BMC cell biology. 2008;9:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao X, Sternsdorf T, Bolger TA, Evans RM, Yao TP. Regulation of MEF2 by histone deacetylase 4- and SIRT1 deacetylase-mediated lysine modifications. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:8456–8464. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.19.8456-8464.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kook H, Lepore JJ, Gitler AD, Lu MM, Wing-Man Yung W, Mackay J, Zhou R, Ferrari V, Gruber P, Epstein JA. Cardiac hypertrophy and histone deacetylase–dependent transcriptional repression mediated by the atypical homeodomain protein Hop. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;112:863–871. doi: 10.1172/JCI19137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.