Abstract

Purpose

Training of health professionals requires development of interprofessional competencies and assessment of these competencies. No validated tools exist to assess all four competency domains described in the 2011 Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice (the IPEC Report). The purpose of this study was to develop and validate a scale based on the IPEC competency domains that assesses interprofessional attitudes of students in the health professions.

Method

In 2012, a survey tool was developed and administered to 1,549 students from the University of Utah Health Science Center, an academic health center composed of four schools and colleges (Health, Medicine, Nursing, and Pharmacy). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (EFA and CFA) were performed to validate the assessment tool, eliminate redundant questions, and to identify subscales.

Results

The EFA and CFA focused on aligning subscales with IPEC core competencies, and demonstrating good construct validity and internal consistency reliability. A response rate of 45% (n = 701) was obtained. Responses with complete data (n=678) were randomly split into two datasets which were independently analyzed using EFA and CFA. The EFA produced a 27-item scale, with five subscales (Cronbach’s alpha coefficients: 0.62 to 0.92). CFA indicated the content of the five subscales was consistent with the EFA model.

Conclusions

The Interprofessional Attitudes Scale (IPAS) is a novel tool that, compared to previous tools, better reflects current trends in interprofessional competencies. The IPAS should be useful to health sciences educational institutions and others training people to work collaboratively in interprofessional teams.

Introduction

Medical education in the United States has changed dramatically since the 1970s when the newly chartered Institute of Medicine (IOM) identified education of health professionals as one of its six primary areas of concern.1 The roles of the physician and other clinicians have also changed since then, particularly in response to two IOM reports: the 2001 Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century2 and the 2003 Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality.3 These documents identified major problems in the U.S. health care system, including health professionals working in “silos” as opposed to patient-centered teams.2 To overcome these problems and meet the needs of the 21st century health system, the 2003 IOM report identified the ability to deliver patient-centered care as a member of an interdisciplinary team as one of the educational goals for all health professionals.3 Preparing a “collaborative practice-ready health workforce” is also a global goal for interprofessional education (IPE; defined as “when two or more professions learn about, from and with each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes”), as described in a 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) report.4

In response to the need to establish IPE core competencies, the 2011 Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice report (herein referred to as the IPEC Report)5 defined four interprofessional core competency domains: Values/Ethics for Interprofessional Practice, Roles/Responsibilities, Interprofessional Communication, and Teams and Teamwork.5 The IPEC Report also identified “the need for assessment instruments to evaluate interprofessional competencies”5(p.35) as a key challenge to implementing IPE competencies.

There are few standardized, validated instruments for assessing IPE competencies. The Readiness for Interprofessional Learning Scale (RIPLS)6 and the extended RIPLS7 represent two well-established tools for assessing interprofessional attitudes; however, these and other tools were developed before the IPEC Report and do not cover the full range of interprofessional competencies. In this paper, we describe the results of our efforts to develop and validate an interprofessional attitudes scale using items derived from the extended RIPLS7 and additional items to better cover the four IPEC Report core competency domains.5 The questionnaire was administered to a large and diverse group of health professional students in 2012. The survey data were analyzed statistically using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to validate the instrument and establish subscales that correspond to the IPEC core competencies.

Method

In 2012, a questionnaire was developed to assess interprofessional attitudes among health professional students. Respondents were recruited from the four schools and colleges comprising the University of Utah Health Sciences Center (UUHSC). At the time, the IPE curriculum at the UUHSC was undergoing significant changes and expansion, and the questionnaire was used to obtain data regarding students’ attitudes towards interprofessionalism and IPE at an early stage of IPE curricular development.

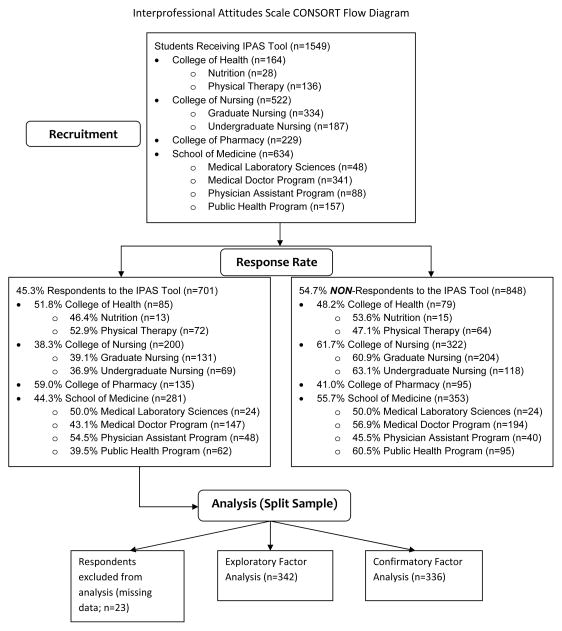

The questionnaire included questions to collect demographic data and 26 items based on the extended RIPLS (five-point Likert scale: 1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree),7 with minor wording modifications (e.g., “health care professionals” was changed to “health professionals/students” or “health sciences students”). The questionnaire also included 16 new items covering competency domains from the IPEC Report that were not covered by the extended RIPLS. Two of the authors (J.N. and D.K.B.) with experience in survey design helped create the survey. Four UUHSC students from different disciplines assessed the questionnaire for content coverage and clarity. The use of the survey was granted exempt status by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board, and the deans of the four UUHSC colleges and schools approved the dissemination of the questionnaire to their respective students. In March 2012, electronic survey invitations were sent by email using Qualtrics (qualtrics.com) to 1,549 UUHSC undergraduate and graduate students in the health care professions (professions targeted are shown in Figure 1). Students from these programs learn and practice in settings that range from a tertiary care medical center to rural health clinics. Invitations made clear the voluntary and anonymous nature of the survey, and included an informed consent document. No incentives for participation were provided. No invalid (i.e., “bounce-back”) email addresses were identified by the survey software. Students had three weeks to complete the survey, and the overall response rate was 45% (701 responses). Figure 1 indicates the numbers of students from each college and school that participated in the survey. The demographics (age, sex, and ethnicity) of the students who participated in the survey were not significantly different from the demographics of the students sent the survey invitations.

Figure 1.

University of Utah Health Sciences Programs Targeted by the Interprofessional Education (IPE) Student Survey in Spring 2012. The survey participants are presented as a CONSORT flow diagram.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 20 and Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) version 20 (IBM, New York, USA) for the EFA and CFA analyses, respectively. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and percentages) were used to describe the demographic characteristics of the sample. A total of 23 responses were excluded from analysis; 7 due to missing data regarding their discipline of study and 16 because their surveys were incomplete and could not be used for the intended EFA and CFA analyses (final sample included 678 students). Due to the large sample size and small number of missing data we chose to utilize list-wise deletion of responses as it would be unlikely that such a small number of deletions would alter outcomes.

To undertake independent EFA and CFA analyses, the total sample was split randomly into two independent subsets: one for the EFA (n = 342), the other for the CFA (n = 336). The numbers in each subset met the criteria of at least 10 subjects per initial item included in the EFA.8

Exploratory factor analysis

An a priori framework was used based on the extended RIPLS7 along with 16 items related to the IPEC Report competencies giving an initial item pool of 42 items. An item analysis was conducted by examining item means, standard deviations, inter-item correlation matrix, and item-total correlations. Structural validity of the scale was then examined using EFA. Because all of the items were associated with interprofessional attitudes, potential factors related to IPE were assumed to be correlated and Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) analysis with Oblimin rotation was conducted with the factor pattern matrix to determine the ‘goodness-of-fit’ of our model. Assumptions regarding matrix identity and sampling adequacy were evaluated using Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test. Items were considered for deletion if their correlations with other items within their potential factor were too high (>|0.80|) or too low (<|0.20|), if they had factor loadings greater than 0.30 on more than one factor, if their Measures of Sampling Adequacy (MSA) values were less than 0.70, or if items were wordy, unclear, or awkward compared to items with similar content. With each item deletion, a new EFA model was generated and evaluated for the best theoretical and statistical fit.

The number of factors to be retained in the final solution was determined by examining the scree plot, then using the “eigenvalues > 1” criterion.8 In order to be retained in the final solution, a factor needed to have at least three items loading greater than 0.30 on that factor with no loadings of those items on other factors. A key criterion was that all items loading on a given factor make intuitive sense as being related statements given our interest in mapping factors to IPEC core competencies. Inter-factor correlations for the final model were examined to determine the extent of correlations among factors.

Internal consistency reliability for each retained factor was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. As this was an initial development of the tool, alpha coefficient values greater than or equal to 0.60 were considered acceptable.9,10

Confirmatory factor analysis

To undertake the CFA, we began with the a priori framework generated by the EFA using data from the other subset of the randomly split sample (n = 336). Both first- and second-order CFA models were examined. A second-order model was used to verify the links between factors and their items identified in the EFA analysis, and to evaluate the extent to which the identified factors represented the overarching construct which we defined as being attitudes toward interprofessional collaboration.

As with the EFA analysis, several criteria were used to determine if an item would be retained in the CFA model. The path coefficients between an item and its predicted subscale from EFA analysis needed to be statistically significant (p < 0.05). Modification indices generated from the structural parameters presented in the CFA analyses were used as guidelines to identify additional statistically significant and theoretically meaningful paths not hypothesized in the EFA analysis. These modification indices are typically used in CFA to provide suggestions for model modifications that are likely to result in a better fit of the model.8,11

The normed χ2 goodness-of-fit test (χ2/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and various incremental (normed fit index [NFI] and comparative fit index [CFI]), predictive (expected cross validation index [ECVI], Akaike information criteria [AIC]), and absolute (goodness-of-fit index [GFI]) fit indices assessed the quality of the model fit to the data.11 A minimum standard of normed χ2 value between 2 and 3, values of at least 0.90 for the incremental and absolute fit indices, and a maximum value of 0.08 for the RMSEA were set.12,13 The hypothesized values for both the ECVI and AIC needed to be smaller than the independence models.11

Upon determining the CFA model and comparing it to our EFA solution, we finalized the number of factors and examined each item that loaded on them. Based on the item loadings and their content, we named the factors, which represent the subscales for the tool.

Results

Sample characteristics

Of the 678 students included in the final analyses, 60.3% (n = 418) were female, 81.7% (n = 550) were Caucasian, 39% (n=271) were from the School of Medicine, and 76% (n=520) had at least one experience in IPE. There were no statistically significant differences in demographics between the EFA and CFA samples (Figure 1, Table 1), nor were there statistically significant differences between the respondents and the cohort of students invited to participate.

Table 2.

Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Interprofessional Attitudes Scale (n = 342)*

| Subscale‡ | Loadings†

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRR | PC | IB | DE | CC | ||

| Eigenvalues | 3.52 | 1.96 | 1.37 | 1.20 | 8.43 | |

| % of Variance | 13.05 | 7.26 | 5.08 | 4.13 | 31.23 | |

|

| ||||||

| Items | M (SD) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| TRR1. Shared learning before graduation will help me become a better team worker. | 3.94 (0.86) | 0.77 | 0.10 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| TRR2. Shared learning will help me think positively about other professionals. | 4.04 (0.84) | 0.76 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

|

| ||||||

| TRR3. Learning with other students will help me become a more effective member of a health care team. | 4.08 (0.74) | 0.76 | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| TRR4. Shared learning with other health sciences students will increase my ability to understand clinical problems. | 4.15 (0.72) | 0.75 | 0.00 | −0.07 | −0.06 | 0.05 |

|

| ||||||

| TRR5. Patients would ultimately benefit if health sciences students worked together to solve patient problems | 4.33 (0.71) | 0.74 | 0.02 | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.03 |

|

| ||||||

| TRR6. Shared learning with other health sciences students will help me communicate better with patients and other professionals. | 4.04 (0.79) | 0.72 | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.16 | −0.04 |

|

| ||||||

| TRR7. I would welcome the opportunity to work on small-group projects with other health sciences students. | 3.68 (1.00) | 0.72 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.06 | 0.08 |

|

| ||||||

| TRR8.§ It is not necessary for health sciences students to learn together. | 3.83 (0.95) | 0.71 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.03 |

|

| ||||||

| TRR9. Shared learning will help me understand my own limitations. | 4.04 (0.79) | 0.63 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| PC1. Establishing trust with my patients is important to me. | 4.66 (0.54) | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.06 |

|

| ||||||

| PC2. It is important for me to communicate compassion to my patients. | 4.59 (0.60) | 0.03 | 0.91 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| PC3. Thinking about the patient as a person is important in getting treatment right. | 4.63 (0.57) | 0.01 | 0.73 | −0.01 | 0.12 | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||

| PC4. In my profession one needs skills in interacting and co-operating with patients. | 4.59 (0.66) | −0.02 | 0.70 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.07 |

|

| ||||||

| PC5. It is important for me to understand the patient’s side of the problem. | 4.56 (0.59) | 0.06 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

|

| ||||||

| IB1. Health professionals/students from other disciplines have prejudices or make assumptions about me because of the discipline I am studying. | 3.53 (0.91) | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

|

| ||||||

| IB2. I have prejudices or make assumptions about health professionals/students from other disciplines. | 2.89 (1.05) | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.60 | −0.11 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| IB3. Prejudices and assumptions about health professionals from other disciplines get in the way of delivery of health care. | 3.71 (0.98) | 0.20 | −0.02 | 0.34 | 0.13 | −0.03 |

|

| ||||||

| DE1. It is important for health professionals to:-Respect the unique cultures, values, roles/responsibilities, and expertise of other health professions. | 4.8 (0.48) | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.88 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| DE2. It is important for health professionals to:-Understand what it takes to effectively communicate across cultures. | 4.76 (0.51) | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 0.75 | 0.11 |

|

| ||||||

| DE3. It is important for health professionals to respect the dignity and privacy of patients while maintaining confidentiality in the delivery of team-based care. | 4.89 (0.33) | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.71 | 0.10 |

|

| ||||||

| DE4. It is important for health professionals to provide excellent treatment to patients regardless of their background e.g. race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, religion, class, national origin, immigration status, or ability. | 4.89 (0.34) | −0.04 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| CC1. It is important for health professionals to work with public health administrators and policy makers to improve delivery of health care. | 4.59 (0.60) | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.88 |

|

| ||||||

| CC2. It is important for health professionals to work on projects to promote community and public health. | 4.60 (0.61) | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.85 |

|

| ||||||

| CC3. It is important for health professionals to work with legislators to develop laws, regulations, and policies that improve health care. | 4.54 (0.67) | −0.04 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.04 | 0.83 |

|

| ||||||

| CC4. It is important for health professionals to work with non-clinicians to deliver more effective health care. | 4.53 (0.64) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.78 |

|

| ||||||

| CC5. It is important for health professionals to focus on populations and communities, in addition to individual patients, to deliver effective health care. | 4.51 (0.63) | 0.06 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.72 |

|

| ||||||

| CC6. It is important for health professionals to be advocates for the health of patients and communities. | 4.71 (0.52) | 0.02 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.16 | 0.69 |

| Subscale | k | M (SD) | Interfactor Correlations (Pearson’s r) (Cronbach’s α)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRR | PC | IB | DE | CC | |||

| TRR | 9 | 4.02 (0.63) | (0.91) | – | – | – | – |

| PC | 5 | 4.60 (0.50) | 0.28## | (0.90) | – | – | – |

| IB | 3 | 3.38 (0.74) | 0.11# | 0.08 | (0.62) | – | – |

| DE | 4 | 4.83 (0.36) | 0.25## | 0.47## | 0.03 | (0.87) | – |

| CC | 6 | 4.58 (0.52) | 0.32## | 0.43## | 0.04 | 0.56## | (0.92) |

Extraction method: Principal Axis Factoring; Rotation method: Oblimin with Kaiser Normalization

Factor loading >0.30 for each item in bold

Subscales: Teamwork, Roles, and Responsibilities (TRR), Patient Centeredness (PC), Interprofessional Biases (IB), Diversity and Ethics (DE), Community Centeredness (CC)

TRR8 item is reverse-coded for a positive correlation with items in factor TRR

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Exploratory factor analysis

The factor structure was analyzed using PAF with an Oblimin rotation. Both the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ2 = 11,515, p < 0.001) and the KMO test (0.92) indicated that the correlation matrix was factorable. The final result of the EFA was a scale that we have named the Interprofessional Attitudes Scale (IPAS). This tool has 27 survey questions (items) that load into five factors (subscales). Each item had factor loadings greater than 0.30 on only one of the five factors (Table 2). Upon examination of their content, these subscales were named: Teamwork, Roles, and Responsibilities (TRR), Patient-Centeredness (PC), Interprofessional Biases (IB), Diversity and Ethics (DE), and Community-Centeredness (CC). These subscales were named based on the relatedness of their items and do not map in a one-to-one manner to the four IPEC Report competency domains. However, each of the four IPEC core competency domains is represented by items in one or more of the IPAS subscales.

Table 3.

Goodness-of-Fit Statistics for Confirmatory Factor Analysis of the Interprofessional Attitudes Scale (n = 336)

| Solution | Result |

|---|---|

| Absolute Fit Indices | |

| χ2 goodness of fit | 724.66* |

| df | 317 |

| Normed χ2 (χ2/df) | 2.29 |

| Root Mean Square Area of Approximation (90% Confidence Interval) | 0.062 (0.056, 0.068) |

| Goodness-of-Fit Index | 0.86 |

|

| |

| Incremental Fit Indices | |

| Normed t Index | 0.88 |

| Comparative t Index | 0.93 |

|

| |

| Predictive Fit Indices | |

| Expected Cross-Validation Index | |

| Hypothesized | 2.53 |

| Saturated | 2.26 |

| Independence | 18.54 |

|

| |

| Akaike Information Criterion | |

| Hypothesized | 846.66 |

| Saturated | 756.00 |

| Independence | 6210.88 |

p < 0.001

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients assessing internal consistency reliability for these five factors ranged between 0.62 and 0.92 (Table 2). The Cronbach’s alpha of 0.62 for Interprofessional Biases is low but not surprising given the few number of items (k = 3) for this subscale.8 We met our assumption that potential factors would be correlated; the inter-subscale correlations ranged from very low (0.03 between Interprofessional Biases and Diversity and Ethics) to medium (0.56 between Diversity and Ethics and Community-Centeredness).

Confirmatory factor analysis

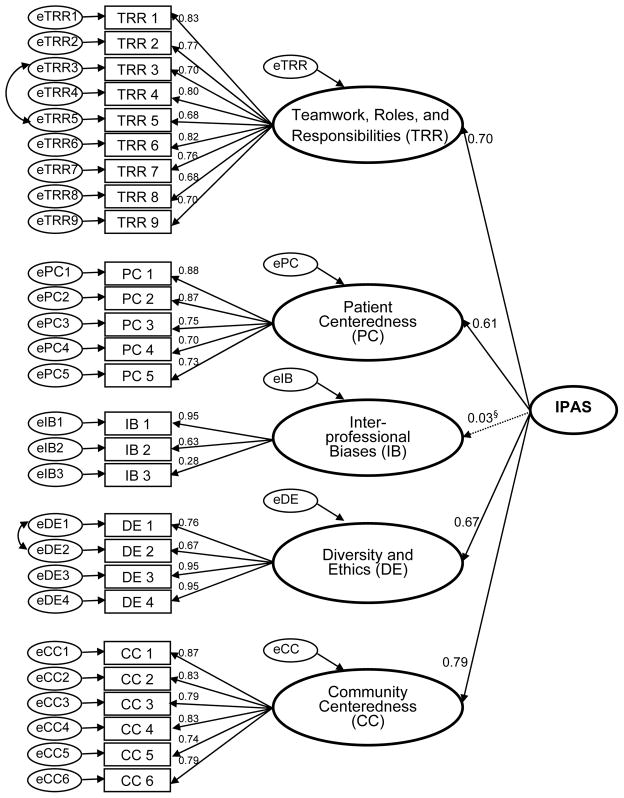

The CFA analyses (AMOS, MLE) indicated all of the items loaded significantly (p < 0.05) on their respective factors specified in the EFA model with standardized regression coefficients ranging from 0.28 to 0.95 (Figure 2). The modification indices indicated that only two minor additions to the resulting model were theoretically meaningful: the correlation between error terms for two items on Teamwork, Roles, and Responsibilities and Diversity and Ethics, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Model. The values presented above the arrows going from the Interprofessional Attitudes Scale (IPAS) to its subscales are path coefficients; they represent the ‘relationship’ between the IPAS and its subscales. Two sets of items, TRR3 and TRR5 and DE1 and DE2, were significantly correlated; these correlations are represented as curved arrows. §The path coefficient for the Interprofessional Biases subscale is low (0.03; p=0.61) indicating this subscale did not load significantly on the IPAS. See text for discussion.

The content of the five subscales was consistent with the EFA model. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were between 0.61 and 0.92. The range of Pearson correlations for these subscales was between −0.04 and 0.56, similar to the result from the EFA model (between 0.03 and 0.56).

Goodness-of-fit statistics

Table 3 reports the second-order goodness-of-fit statistics for the IPAS. The normed χ2 statistic (2.29) indicated a satisfactory fit of the model (desired range of values: 2 – 5). All of the incremental fit indices and GFI (0.86 – 0.93) were very close to or above the target level (0.90). The RMSEA coefficient (0.062, 90% CI: 0.056 – 0.068) was within acceptable limits.

Discussion

Until recently, a paucity of conceptual frameworks and tools existed for assessing IPE outcomes.7,14 The 2011 IPEC Report provided such a framework in the form of interprofessional core competency domains, which we used to develop a tool to assess interprofessional attitudes. Our tool, the Interprofessional Attitudes Scale (IPAS), expands upon RIPLS, one of the most widely used IPE assessment instruments though the reliability of RIPLS’s items and subscales have been challenged.15,16 Analysis using independent EFA and CFA indicate that the IPAS has good construct validity.

Previous work validating the original 19-item RIPLS using factor analysis methods resulted in three subscales, labeled as Teamwork and Collaboration, Professional Identity, and Roles and Responsibilities.6 Nine items from RIPLS, including four items from Teamwork and Collaboration and five items from Professional Identity were retained in IPAS and all loaded into the Teamwork, Roles, and Responsibilities subscale. Analysis of the 23-item extended RIPLS identified three subscales, Teamwork and Collaboration, Sense of Professional Identity, and Patient-Centeredness.7 Fourteen items from the extended RIPLS were retained in IPAS. All five items from the extended RIPLS Patient-Centeredness subscale loaded into the IPAS Patient-Centeredness subscale, and eight items from the Teamwork and Collaboration extended RIPLS subscale loaded into the IPAS Teamwork, Roles, and Responsibilities subscale. Only one item from the extended RIPLS Sense of Professional Identity subscale was retained in IPAS and it loaded into the Teamwork, Roles, and Responsibilities subscale. Three subscales unique to the IPAS have been named Diversity and Ethics, Community-Centeredness, and Interprofessional Biases. None of the RIPLS or extended RIPLS items loaded onto these new subscales. Thus, the IPAS covers a wider range of interprofessional attitudes than RIPLS in a 27-item scale, which most users can complete in less than 10 minutes.

The IPAS is novel because it links assessment of IPE to the IPEC core competencies.7 Further, because most development and testing of IPE instruments to date has occurred outside the U.S., IPAS is useful as a scale developed and validated at a large U.S. academic health center with a range of health professional programs. To make it widely available, IPAS will be submitted to the National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education (NEXUS IPE) [http://nexusipe.org/measurement-instruments]. Use of IPAS could allow establishment of baseline attitudes toward IPE, comparison of attitudes among different groups, tailoring of IPE experiences to specific groups, and development of optimal IPE programs. IPAS could also be used longitudinally for pre- and post-intervention assessment, though valdiation of IPAS for this purpose is needed. Future plans include data collection at both the University of Utah and University of New Mexico to validate IPAS for pre- and post-intervention assessment.

Strengths and limitations

Though the survey data we used had a response rate of 45% (a response rate comparable to previous RIPLS analyses16), the sample size (678 usable responses) was sufficiently large to allow independent EFA and CFA. Moreover the demographics of the responders was representative of the entire student population invited to participate. A potential limitation is that our analysis is based on data from a single educational institution. Although the participants from this institution represent a diversity of health professions, IPE and collaborative practice often involves even greater diversity of professions. Future work will focus on evaluating the IPAS at other institutions and in a broader range of professions including students from mental health professions, social work, speech pathology/disorders, occupational therapy, health promotion, and genetic counseling. While we did not investigate differences among professional groups surveyed, future research using IPAS should focus on attaining sufficient numbers of each profession in the sample so that item and subscale group comparisons can be made. Additionally, IPAS should be evaluated in post-graduate settings (e.g., residents and fellows), among practicing health professionals, and among faculty. Although the survey was administered to a student body that had been exposed to very few formal IPE experiences, the responses to many of the survey items showed very favorable attitudes towards interprofessionalism. This “ceiling effect”, which is also seen in other scales such as the RIPLS and IEPS,17 can make it difficult to detect changes in interprofessional atttitudes in longitudinal studies. This effect suggests that some restructuring of items and response format may be needed to encourage a wider range of responses, such as using a 100-point slider bar instead of a traditional five-level Likert scale.

While our scale was designed to address all four core competencies defined in the IPEC Report, the five subscales that were identified in the statistical analysis do not map directly to those core competencies. To a large degree this reflects the overlapping nature of interprofessional competencies and the difficulty in designing a tool with subscales (based on statistical analyses) that can address specific interprofessional competencies. It is worth noting that the Interprofessional Biases subscale does not correlate with any of the other subscales (Figure 2) indicating that this subscale assesses unique interprofessional attitudes. We chose to keep this subscale in IPAS because attitudes assessed by this subscale impact several core competencies of the IPEC Report such as Roles/Responsibilities, Teams and Teamwork, and Values/Ethics of Interprofessional Practice. Future efforts will focus on refining and developing additional IPAS items to assess the full range of interprofessional competencies described in the IPEC Report.

Lastly, the IPAS was not designed to directly assess interprofessional skills or the impact of IPE on health care delivery. Additional tools that complement the IPAS, such as objective standardized clinical exams and prospective outcomes studies, are needed to fully assess the effectiveness of an IPE program. Ultimately, it will be important to demonstrate a relationship between interprofessional attitudes and higher-order interprofessional outcomes (skills, behaviors, and competencies) that improve collaborative patient-centered care.

Conclusion

IPAS represents a novel scale for the assessment of interprofessional attitudes. Unlike prior scales, it was designed to incorporate the four core competency domains of the recent IPEC Report.5 Thus, IPAS offers a simple IPE assessment tool that reflects current trends in interprofessional competencies and should prove useful to a range of health sciences institutions committed to training students to work in interprofessional teams.

Table 1.

Comparison of Participant Characteristics and Subscales from the Interprofessional Attitudes Scale by Exploratory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (N = 678)

| EFA* n = 342 |

CFA† n = 336 |

Total n = 678 |

χ2test p |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | 0.89 | ||||||

| Male | 134 | 39.2 | 133 | 39.7 | 267 | 39.4 | |

| Female | 208 | 60.8 | 202 | 60.3 | 410 | 60.6 | |

|

| |||||||

| Racial and/or ethnic identity | 0.59‡ | ||||||

| White | 272 | 81.4 | 269 | 83.0 | 541 | 82.2 | |

| Others: | 62 | 18.6 | 55 | 17.0 | 117 | 17.8 | |

| Black | 5 | 1.5 | 5 | 1.5 | 10 | 1.5 | |

| East Asian | 15 | 4.5 | 9 | 2.8 | 24 | 3.6 | |

| Southeast Asian | 10 | 3.0 | 7 | 2.2 | 17 | 2.6 | |

| South Asian | 2 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.9 | 5 | 0.8 | |

| Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.9 | 4 | 0.6 | |

| Native American, Alaska Native | 1 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.5 | |

| Hispanic, Latino/Latina | 13 | 3.9 | 11 | 3.4 | 24 | 3.6 | |

| Middle Eastern, Western Asia | 3 | 0.9 | 4 | 1.2 | 7 | 1.1 | |

| More than one | 12 | 3.6 | 11 | 3.4 | 23 | 3.5 | |

|

| |||||||

| Age | 0.33 | ||||||

| 13–22 | 14 | 4.1 | 7 | 2.1 | 21 | 3.1 | |

| 23–32 | 230 | 67.3 | 239 | 71.3 | 469 | 69.3 | |

| 33–42 | 65 | 19.0 | 54 | 16.1 | 119 | 17.6 | |

| 43–52 | 21 | 6.1 | 23 | 6.9 | 44 | 6.5 | |

| 53–62 | 10 | 2.9 | 12 | 3.6 | 22 | 3.2 | |

| 63–72 | 2 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0.3 | |

|

| |||||||

| Department | 0.92 | ||||||

| College of Health | 43 | 12.6 | 42 | 12.5 | 85 | 12.5 | |

| College of Nursing | 100 | 29.2 | 95 | 28.3 | 195 | 28.8 | |

| College of Pharmacy | 70 | 20.5 | 64 | 19.0 | 134 | 19.8 | |

| School of Medicine | 129 | 37.7 | 135 | 40.2 | 264 | 38.9 | |

|

| |||||||

| How often do you interact with patients during your clinical activities? | |||||||

| Never | 41 | 12.1 | 35 | 10.5 | 76 | 11.3 | 0.56 |

| Less than once a month | 18 | 5.3 | 23 | 6.9 | 41 | 6.1 | |

| Once a month | 8 | 2.4 | 7 | 2.1 | 15 | 2.2 | |

| 2–3 times a month | 36 | 10.7 | 28 | 8.4 | 64 | 9.5 | |

| Once a week | 34 | 10.1 | 33 | 9.9 | 67 | 10.0 | |

| 2–3 times a week | 37 | 10.9 | 52 | 15.6 | 89 | 13.2 | |

| Daily | 164 | 48.5 | 156 | 46.7 | 320 | 47.6 | |

|

| |||||||

| EFA M(SD) |

CFA M(SD) |

Independent Samples Test | |||||

| t | df | p | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Subscales | |||||||

| Teamwork, Roles, and Responsibilities (TRR) | 4.02 (0.63) | 4.03 (0.62) | −0.23 | 676 | 0.82 | ||

| Patient Centeredness (PC) | 4.60 (0.50) | 4.62 (0.46) | −0.50 | 676 | 0.62 | ||

| Interprofessional Biases (IB) | 3.38 (0.74) | 3.34 (0.71) | 0.68 | 676 | 0.50 | ||

| Diversity and Ethics (DE) | 4.83 (0.36) | 4.85 (0.36) | −0.46 | 676 | 0.65 | ||

| Community Centeredness (CC) | 4.58 (0.52) | 4.59 (0.51) | −0.30 | 676 | 0.77 | ||

EFA: Exploratory Factor Analysis

CFA: Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The χ2 test was based on White vs. Others

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: No funding organization(s) or sponsor(s) had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The authors wish to thank students from the UUHSC Health Sciences Student Council who participated in the early phases of survey development and who promoted the survey to their fellow students. Joan G. Carpenter was supported by a National Research Service Award (NRSA) traineeship funded by NIH on training grant T32NR013456, “Interdisciplinary Training in Cancer, Aging and End-of-Life Care” at the University of Utah College of Nursing.

Funding/Support: None

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None

Ethical approval: The IRB at the University of Utah granted this study exempt status on February 3, 2012. The study title is: “Students’ knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of interprofessional issues and education in the University of Utah Health Sciences Center”. The IRB study number is: IRB_00054062.

Disclaimer: None

Previous presentations: A preliminary report of this work was presented in the form of a poster at the 14th Annual International Meeting on Simulation in Healthcare (IMSH) in January 2014 in San Francisco, CA.

Contributor Information

Dr. Jeffrey Norris, Resident Physician, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center, Albuquerque, NM.

Ms. Joan G. Carpenter, PhD candidate, Hartford Center of Geriatric Nursing Excellence, College of Nursing, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, http://www.researchgate.net/profile/Joan_Carpenter/info/.

Ms. Jacqueline Eaton, PhD Candidate, Hartford Center of Geriatric Nursing Excellence, College of Nursing, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT.

Dr. Jia-Wen Guo, Assistant Professor, College of Nursing, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, http://faculty.utah.edu/u0477623-JIA-WEN_GUO/biography/index.hml.

Ms. Madeline Lassche, Instructor (Clinical) and PhD student, College of Nursing, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, http://faculty.utah.edu/u0058317-Madeline_Lassche_MSNEd,_RN/biography/index.hml.

Dr. Marjorie A. Pett, Research Professor, College of Nursing, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, http://faculty.utah.edu/u0027992-MARJORIE_A._PETT/biography/index.hml.

Dr. Donald K. Blumenthal, Associate Professor of Pharmacology & Toxicology, Associate Dean for Interprofessional Education, and Assistant Dean for Assessment, College of Pharmacy, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, http://pharmacy.utah.edu/pharmtox/faculty/blumenthal.html.

References

- 1.National Research Council. To Improve Human Health: A History of the Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Research Council. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Research Council. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Collaborative Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, D.C: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsell G, Bligh J. The development of a questionnaire to assess the readiness of health care students for interprofessional learning (RIPLS) Med Educ. 1999;33(2):95–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1999.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid R, Bruce D, Allstaff K, McLernan D. Validating the readiness for interprofessional learning scale (RIPLS) in the post graduate context: Are health care professionals ready for IPL? Med Educ. 2006;40:415–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pett M, Lackey N, Sullivan J, editors. Making Sense of Factor Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hair J. Multivariate data analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nunnally JC, Bernstein I. Psychometric Theory. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clayton MF, Pett MA. Modeling relationships in clinical research using path analysis Part II: Evaluating the model. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2011;16(1):75–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2010.00272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmines EG, McIver JP. Analyzing models with unobserved variables: Analysis of covariance structures. In: Bohrnstedt GW, Borgatta EF, editors. Social Measurement: Current Issues. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1981. pp. 65–115. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods and Research. 1992;21:230–259. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thannhauser J, Russell-Mayhew S, Scott C. Measures of interprofessional education and collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2010;24(4):336–349. doi: 10.3109/13561820903442903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McFadyen AK, Webster V, Strachan K, Figgins E, Brown H, McKechnie J. The readiness for interprofessional learning scale: A possible more stable sub-scale model for the original version of RIPLS. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(6):595–603. doi: 10.1080/13561820500430157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams B, Brown T, Boyle M. Construct validation of the readiness for interprofessional learning scale: A Rasch and factor analysis. J Interprof Care. 2012;26(4):326–332. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2012.671384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinto A, Lee S, Lombardo S, et al. The impact of structured inter-professional education on health care professional students’ perceptions of collaboration in a clinical setting. Physiother Can. 2012;64(2):145–156. doi: 10.3138/ptc.2010-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]