Abstract

Purpose

To assess retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness at term-equivalent age in very preterm (<32 weeks gestational age) versus term-born infant cohorts, and compare very preterm infant RNFL thickness with brain anatomy and neurodevelopment.

Design

Cohort study.

Methods

RNFL was semi-automatically segmented (one eye per infant) in 57 very preterm and 50 term infants with adequate images from bedside portable, handheld spectral domain optical coherence tomography (Bioptigen, Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC) imaging at 37-42 weeks postmenstrual age. Mean RNFL thickness was calculated for the papillomacular bundle (−15° to + 15°) and temporal quadrant (−45° to +45°) relative to the fovea-optic nerve axis. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans clinically obtained in 26 very preterm infants were scored for global structural abnormalities by an expert masked to data except for age. Cognitive, language, and motor skills were assessed with Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development-III (Pearson, San Antonio, TX) in 33 of the very preterm infants at 18-24 months corrected age.

Results

RNFL was thinner for very preterm versus term infants at the papillomacular bundle ([mean ± standard deviation] 61 ± 17 versus 72 ± 13 μm, p<0.001) and temporal quadrant (72 ± 21 versus 82 ± 16 μm, p=0.005). In very preterm infants, thinner papillomacular bundle RNFL correlated with higher global brain MRI lesion burden index (R2=0.35, p=0.001) and lower cognitive (R2=0.18, p=0.01) and motor (R2=0.17, p=0.02) scores. Relationships were similar for temporal quadrant.

Conclusions

Thinner RNFL in very preterm infants relative to term-born infants may relate to brain structure and neurodevelopment.

Introduction

Infants born very preterm (<32 weeks gestational age) have a high rate (50-70%) of poor neurodevelopment.1 Compared to term infants, very preterm infants have smaller total brain volume,2 reduced white matter integrity,3 abnormal visual cortical sensitivity4 and more intraventricular hemorrhages. Worse neurodevelopmental outcomes are found among very preterm infants with unfavorable versus favorable visual status.5 While recent studies in adults have emphasized the impact of retinal abnormalities on the visual pathway,6 the relationship between early retinal and optic nerve microanatomy and brain anatomy or subsequent brain functions is not known in preterm infants.

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) provides high-resolution, in vivo imaging of eye microanatomy, including the layers of the retina such as the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL). The RNFL consists of the unmyelinated ganglion cell axons that form the optic nerve, become myelinated posterior to the lamina cribrosa, and then extend as the optic tract to synapse in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus. Thus, SD-OCT enables non-invasive assessment of central nervous system tissue via the retina, which is an extension of the diencephalon.7 Assessment of RNFL is generally based on segmentation of SD-OCT images to produce an average RNFL thickness. This measurement has been studied extensively in the adult population as a biomarker for glaucoma and optic atrophy. In addition, average RNFL thickness is under investigation as a biomarker for neurodegenerative diseases such as multiple sclerosis,8-10 Alzheimer disease,11 and Parkinson disease,12 under the premise that anatomic abnormalities in the anterior visual pathway correlate with greater central nervous system disease burden. While previous studies in school-aged children demonstrated differences in RNFL thickness by birth parameters,13-17 neither these relationships nor potential correlations between RNFL and neurologic health have been established during the neonatal period.

The introduction of portable, handheld SD-OCT to the nursery allows for non-contact, bedside assessment of the non-sedated, supine infant's retinal microanatomy,18, 19 which provides insight into eye development and maturation.20-26 Correlations have been reported between these retinal and optic nerve metrics of development, and the broader brain health of preterm infants. For example, subclinical macula edema has been identified as an ophthalmologic biomarker of poor neurodevelopment in very preterm infants.24 In another study, Tong et al. utilized SDOCT to reproducibly quantify optic nerve parameters in preterm infants which correlated with both brain pathology and subsequent neurodevelopmental abnormalities.23 Furthermore, average RNFL thickness has been measured reproducibly in healthy, term neonates as another metric of central nervous system tissue.26 In this study we aim to evaluate the relationship of ganglion cell anatomy to brain health and development by assessing RNFL thickness measurements ,and to compare these data to standardized quantification of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain lesion burden27 and neurodevelopmental outcomes28 in very preterm infants.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was approved by the Duke University Health System institutional review board and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and all tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Infants were enrolled from August 2010 to July 2014 with the written consent of a parent or legal guardian. The healthy, term cohort has been previously described.26 Term infants in the newborn nursery were eligible if born between 37 and 42 weeks post-menstrual age and deemed clinically stable to undergo SD-OCT imaging. Very preterm infants at the Duke University intensive care nursery were eligible for SD-OCT imaging following clinically indicated retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) screening examination if deemed clinically stable at the time of eye examination by the intensive care nursery pediatric team. Criteria for ROP screening included: birth at or before 30 weeks post-menstrual age or birth weight at or under 1500 g,29 and at least four weeks of life at the time of first eye exam. All SD-OCT imaging was performed following an age-specific protocol described by Maldonado et al. using a portable, handheld SD-OCT system (either an early research system, the Envisu 2200, or the Envisu 2300, Bioptigen, Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC).18 This protocol obtains volumetric rectangular OCT scans with both A-scans and B-scans 10 μm apart. Demographic information was collected from medical records, including gestational age, birth weight, gender, race, maximum ROP severity (stage), maximum plus disease status (whether or not plus disease was clinically diagnosed), and clinical need for ROP treatment (laser photocoagulation or intravitreal bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor pharmaceutical used off-label for ROP treatment).

One eye per infant was included in this study; all scans obtained from both eyes were considered with whichever eye had the best SD-OCT scan as selected by a trained pediatric SD-OCT grader (A.L.R.) included. The best SD-OCT scans were considered those with minimal eye movement, tilt, and rotation and with optimal alignment and differentiation of retinal layers for RNFL thickness analyses. The best SD-OCT scan captured within the interval of 37 and 42 weeks post-menstrual age (term equivalent age) that contained the optic disc and macula was used for each infant in the primary analysis, while the best scan obtained at 36 weeks post-menstrual age or less was included for a secondary analysis if available.

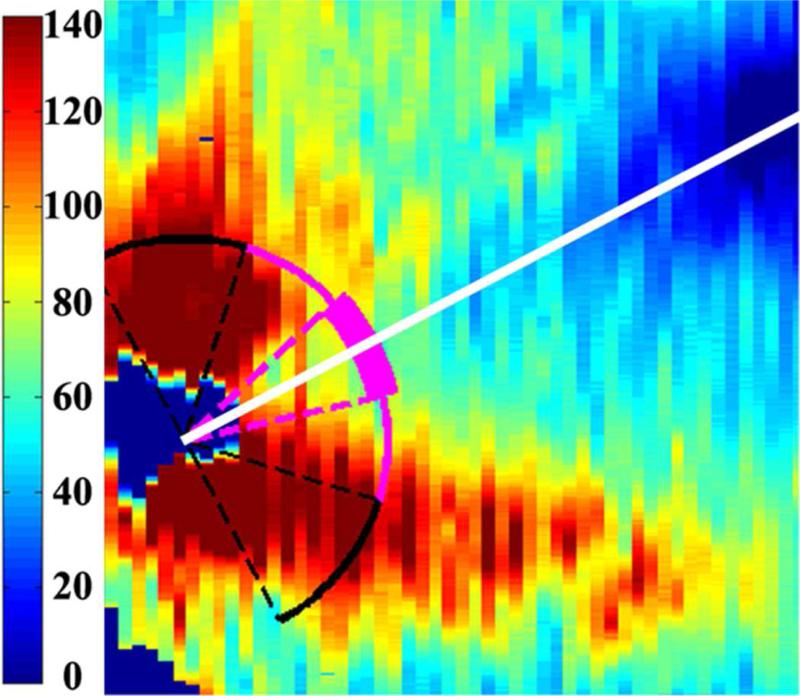

Average RNFL thickness was measured on all SD-OCT scans using a previously described method that utilized several custom MATLAB scripts (Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA).26 To summarize, SD-OCT scans were converted to tagged image file format and registered with ImageJ v 1.43r software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD). The inner and outer boundaries of the RNFL were semi-automatically segmented with a custom script and manually corrected by two trained graders (A.L.R. and M.B.S.). These graders then marked the optic nerve center and fovea on each scan to create an organizing axis. The average RNFL thickness was calculated at a radial distance of 1.5 mm from the optic nerve center across the papillomacular bundle, defined as the arc from −15° to +15° relative to the organizing axis, as well as across the temporal quadrant, defined as the arc from −45° to +45° rela tive to the organizing axis (Figure 1). Average RNFL thickness measurements were required to have a minimum of 90% of the specified arc segmented for inclusion. In two term and one very preterm infant, there was insufficient scan data to measure RNFL across the temporal quadrant. Presence of macular edema as well as quantitative parameters of macular edema severity (central foveal thickness, inner nuclear layer thickness, and the average foveal-to-parafoveal thickness ratio at a 1000 μm distance from the foveal center) were measured using the calipers tool of OsiriX v4.1.12 software (Pixmeo, Bernex, Switzerland)24 for every imaging session obtained on each very preterm infant by two trained graders (A.L.R. and S.M.) masked to RNFL data. The SD-OCT scan with the greatest central foveal thickness was selected as the imaging session representing the greatest edema.

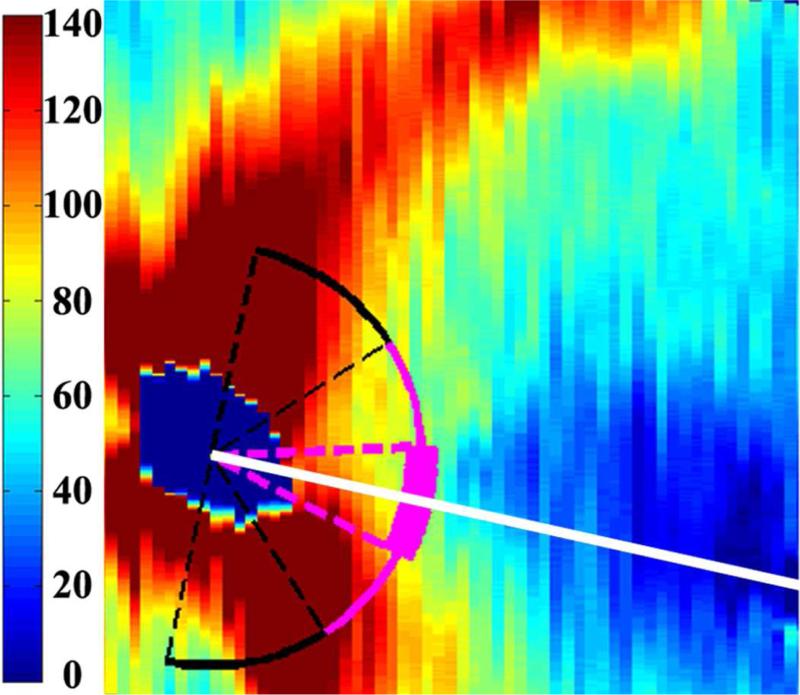

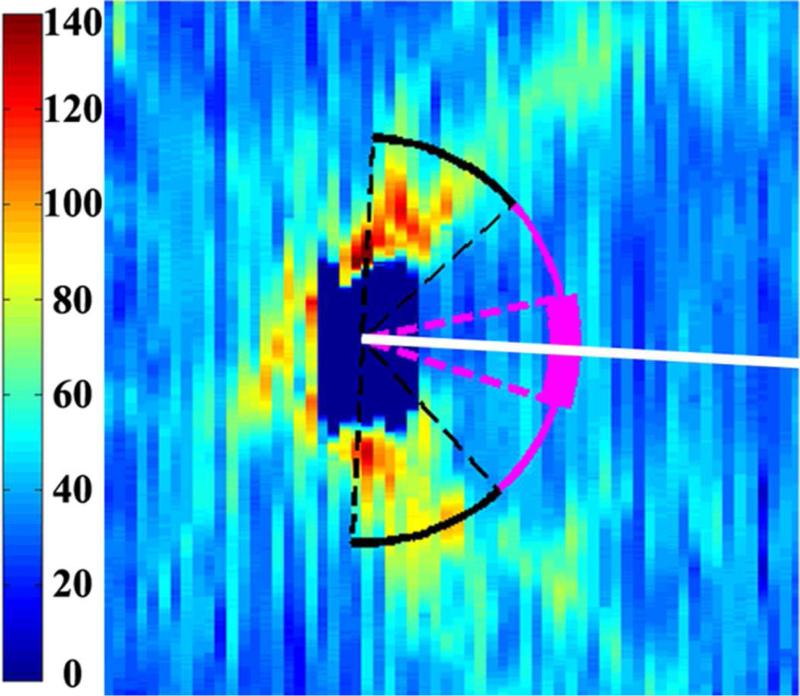

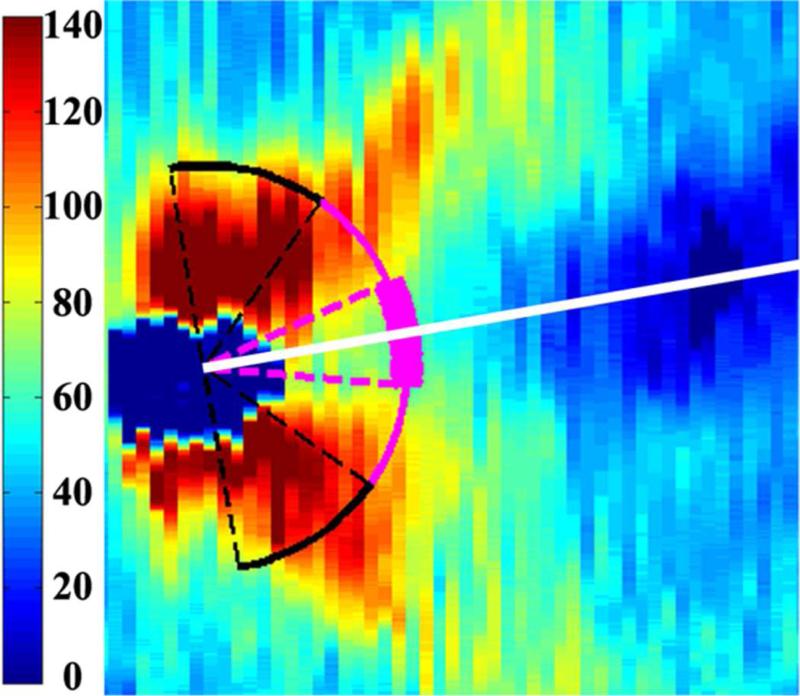

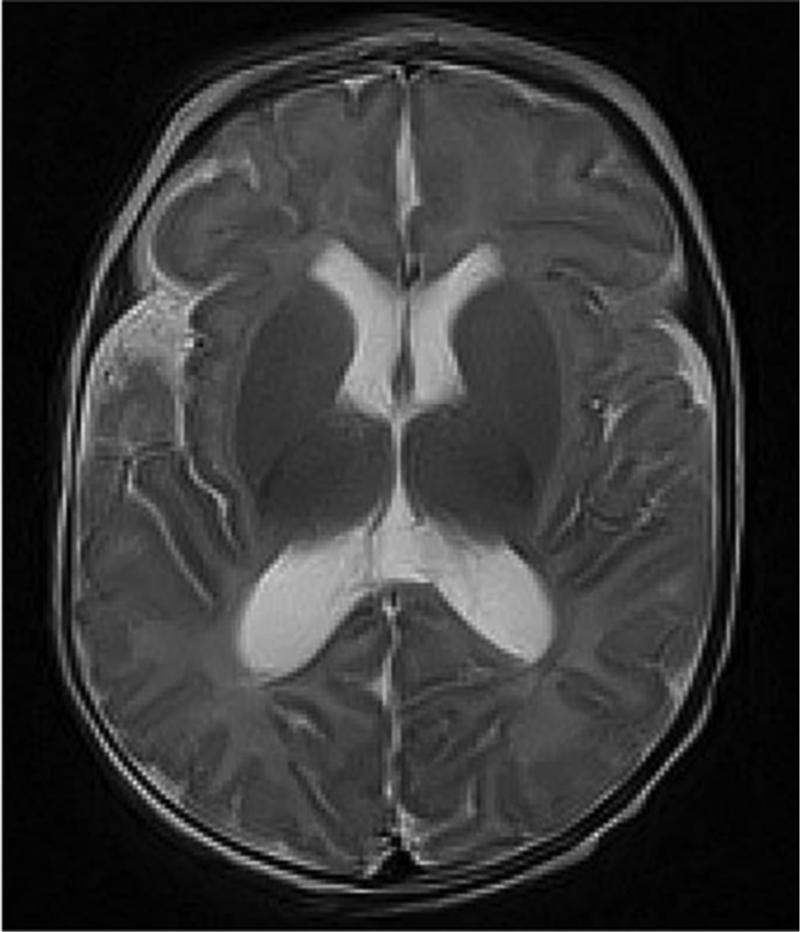

Figure 1.

Retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness maps derived from segmented spectral domain optical coherence tomography scans obtained in the nursery. The thick pink arc corresponds to the papillomacular bundle: arc from −15 to +15 degrees relative to the organizing axis from the optic nerve center to the fovea. The thin pink arc corresponds to the temporal quadrant: arc from −45 to +45 degrees relative to the organizing axis. Left, RNFL thickness map of a healthy, term Hispanic male born and imaged at 39 weeks post-menstrual age. Mean RNFL thickness is 83 μm across the papillomacular bundle and 97 μm across the temporal quadrant. Right, RNFL thickness map of a white male born at 31 weeks gestational age and 1400 g with stage 0 retinopathy of prematurity. Mean RNFL thickness at 39 weeks post-menstrual age is 64 μm across the papillomacular bundle and 78 μm across the temporal quadrant.

Each infant with brain MRI imaging while in the intensive care nursery (near term) had his or her de-identified brain MRI uploaded to a secure server and scored by a Pediatric Neuro-radiologist (J.S.S.) for structural abnormalities using conventional T1- and T2-weighted images. Brain MRI was available for analysis when ordered as clinically indicated by the neonatology team and was not obtained on all very preterm infants. A modification of the brain MRI scoring system developed by Kidokoro et al. was used to generate brain lesion indices.27 The original scoring system was altered by excluding the corpus callosum measurement since it was difficult to perform in our population, and the lateral ventricle measurement was done in the transverse plane since the prescribed coronal views were not available. This provided a cerebral white matter, total cortical grey matter, deep grey matter, and cerebellar lesion burden subscore as well as a total global brain lesion burden index that correlates with the extent of brain injury.

Medical records were reviewed to assess for very preterm infant brain health and systemic health, including inflammation, which might impact neurodevelopment. Systemic health information including diagnoses of hydrocephalus, intraventricular hemorrhage and grade, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotizing enterocolitis, use of postnatal hydrocortisone or dexamethasone, blood or cerebrospinal fluid culture positive sepsis, culture negative sepsis, urinary tract infection, and weight percentile at 36 weeks post-menstrual age on the Fenton Preterm Growth Chart30 were evaluated by neonatologists (C.M.C. and L.E.).

Bayley Scales scores were gathered for all very preterm infants in whom these were available. All very preterm infants from the intensive care nursery were referred to a special infant care follow-up clinic as part of standard intensive care nursery practice. This clinical tool, considered standard of care for neurodevelopmental assessment, provides composite scores in cognitive, language, and motor skills that are standardized to a mean of 100 and standard deviation of 15.28 A licensed psychologist and infant developmental specialist (K.E.G.) certified as a Bayley examiner by the National Institute of Health Neonatal Research Network, assessed the infants using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, Third Edition (Pearson, San Antonio, TX) at 18-24 months corrected age. The examiner was masked to all eye imaging data.

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro v 10 (SAS, Cary, NC). Demographic parameters were compared between term and very preterm infants with two-tailed t-tests for continuous variables and Fisher exact tests for nominal variables. Demographics were compared between very preterm infants who had brain MRI imaging while in the intensive care nurseryversus those who did not have MRI, and between those who underwent Bayley assessment and those who did not but were age-eligible at the time of analysis, using Wilcoxon ranked-sum tests for continuous variables and Fisher exact test for nominal variables.

All analyses involving mean RNFL thickness were performed with both papillomacular bundle and temporal quadrant measurements. Mean RNFL thickness for term versus very preterm infants was compared by a two-tailed t-test. A matched pairs analysis compared mean RNFL thickness for all very preterm infants with an adequate SD-OCT scan at both <37 weeks post-menstrual age and term-equivalent age and was repeated by categorizing the very preterm infants by need for ROP treatment. Gestational age, age at imaging, and birth weight were compared to mean RNFL thickness across all infants and within the very preterm cohort by linear regression. Mean RNFL thickness was compared between maximum ROP stage and plus disease status by Kruskal-Wallis tests, while mean RNFL thickness and need for ROP treatment were compared by a Wilcoxon ranked-sum test. Mean RNFL thickness was compared between very preterm infants with and without macular edema by a two-tailed t-test, and in relation to maximum central foveal thickness, inner nuclear layer thickness, and foveal-to-parafoveal thickness ratio by linear regression. Very preterm infants with previously characterized optic nerve parameters23 had their mean RNFL thickness compared to their cup-to-disc ratio by linear regression.

Mean RNFL thickness intragrader and intergrader reproducibility was assessed across the papillomacular bundle by intraclass correlation coefficients and 95% confidence intervals for 20 randomly selected very preterm infant SD-OCT scans by one (A.L.R.) and two graders (A.L.R. and M.B.S.), respectively. Intravisit reproducibility was also assessed by regarding (A.L.R.) all very preterm infants with more than one adequate SD-OCT scan at the same imaging session. All SD-OCT scans used for reproducibility assessment were resegmented with their optic nerve and fovea remarked by graders masked to initial RNFL thickness measurements. Intragrader, intergrader, and intravisit reproducibility of healthy, full term neonatal RNFL thickness have been previously reported.26

The relationships between mean RNFL thickness and brain lesion indices were assessed by linear regression; cortical and deep grey matter scores were combined for a total grey matter injury subscore. Mean RNFL thickness was compared between the very preterm infants who did versus did not have a clinical MRI obtained and who did versus did not have Bayley Scales follow-up (two-tailed t-test). Mean RNFL thickness was evaluated against the presence of systemic health factors with a Wilcoxon ranked-sum test. Note, with Bonferroni correction a p-value <0.005 is required for statistical significance for this subanalysis. Cognitive, language, and motor Bayley Scales scores were compared to RNFL thickness by linear regression as was global brain MRI lesion burden index versus Bayley Scales scores.

Multivariate analyses were used to assess the contribution of systemic health parameters towards the two outcomes of neurologic health: global brain lesion burden index and Bayley Scales scores. For each analysis, systemic health parameters were gestational age, birth weight, ROP treatment, macular edema, and mean RNFL thickness. Note that the global brain lesion burden index model contained only very preterm infants with MRI obtained in the intensive care nursery while the Bayley Scales model contained those with Bayley Scales follow-up as a toddler. Only significant parameters are included in the reported models. Values shown represent mean ± standard deviation or median (range) unless otherwise specified.

Results

Demographics

Fifty-seven term infants and 134 very preterm infants were enrolled in the prospective SD-OCT imaging study, and parents withdrew one term and three very preterm infants prior to imaging (Figure 2). Fifty of 56 term infants and 57 of 83 very preterm imaged at term-equivalent age had an SD-OCT scan of adequate quality for RNFL analysis. Throughout these results, unless otherwise stated the RNFL measurements are at term-equivalent age. The term infants have been previously described.26 Basic demographic information for both cohorts is found in Table 1. The mean gestational age and birth weight for the term versus very preterm infants were 39.2 ± 1.1 versus 25.9 ± 2.3 weeks post-menstrual aqe (p<0.001) and 3356 ± 458 versus 831 ± 243 grams (p<0.001), respectively. There was no significant difference in the age at SD-OCT imaging or eye laterality between the two groups. There was a lower percentage of males in the term (44%) versus very preterm group (65%, p=0.03). The racial/ethnicity compositions of the two groups differed (p<0.001) due to the higher prevalence of Hispanics in the term (40%) compared to the very preterm group (5%). In addition, 20 (35%) very preterm infants had severe ROP requiring treatment; 18 had laser treatment prior to SD-OCT imaging, while one infant received bevacizumab before imaging and one received bevacizumab after imaging.

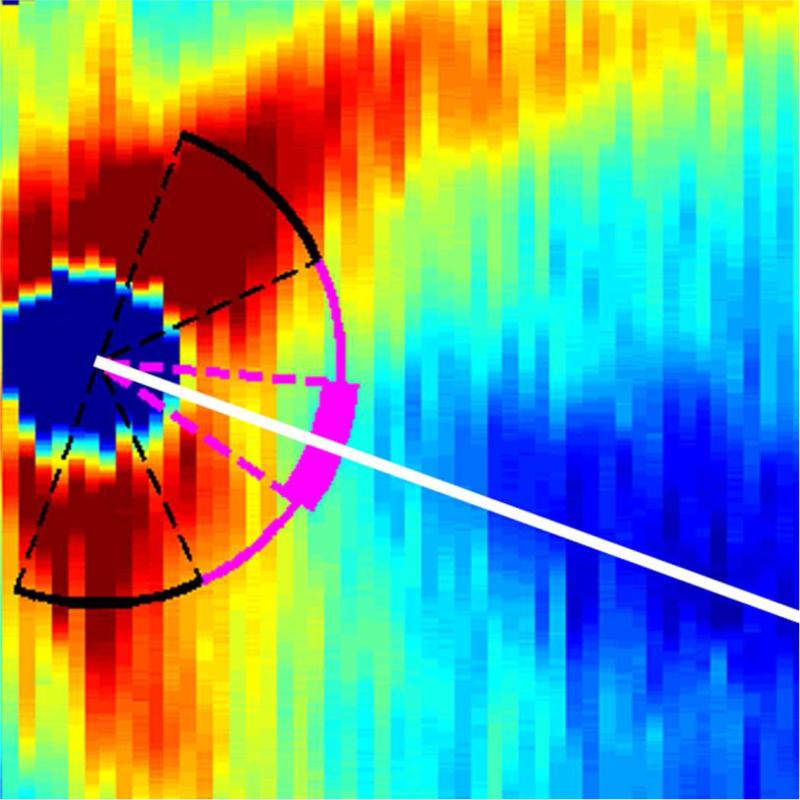

Figure 2.

Infant enrollment and eligibility for analysis. Note that all infants were referred for Bayley Scales assessment while brain magnetic resonance imaging was obtained at the discretion of the neonatology team. As a result, very preterm infants may be included in neither, one, or both secondary analyses.

Table 1.

Basic Demographics of Term and Very Preterm Infants

| Term N=50 | Very Preterm N=57 | P-Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational Age (wks), mean (SD) | 39.2 (1.1) | 25.9 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| Birth Weight (wks), mean (SD) | 3356 (458) | 831 (243) | <0.001 |

| Age at OCT Imaging (wks), mean (SD) | 39.2 (1.1) | 38.8 (1.7) | 0.22 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.03 | ||

| Male | 22 (44) | 37 (65) | |

| Race, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| African-American | 12 (24) | 28 (49) | |

| Caucasian | 18 (36) | 26 (46) | |

| Hispanic | 20 (40) | 3 (5) | |

| Eye, n (%) | 0.85 | ||

| OD | 26 (52) | 31 (54) | |

| Maximum ROP Stage, n (%) | |||

| 0 | --- | 9 (16) | |

| 1 | --- | 5 (9) | |

| 2 | --- | 19 (33) | |

| 3 | --- | 22 (39) | |

| 4 | --- | 2 (3) | |

| Plus Disease, n (%) | |||

| No Plus | --- | 32 (56) | |

| Pre-Plus | --- | 14 (25) | |

| Plus | --- | 11 (19) | |

| ROP Treatment, n (%) | |||

| No Treatment | --- | 37 (65) | |

| Laser Photocoagulation | --- | 18 (32) | |

| Bevacizumab | --- | 2 (3) | |

wks, weeks; SD, standard deviation; OCT, optical coherence tomography; ROP, retinopathy of prematurity

Two-tailed t-test for gestational age, birth weight, and age at imaging; Fisher's exact test for sex, race, and eye

Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness in Term and Very Preterm Infants

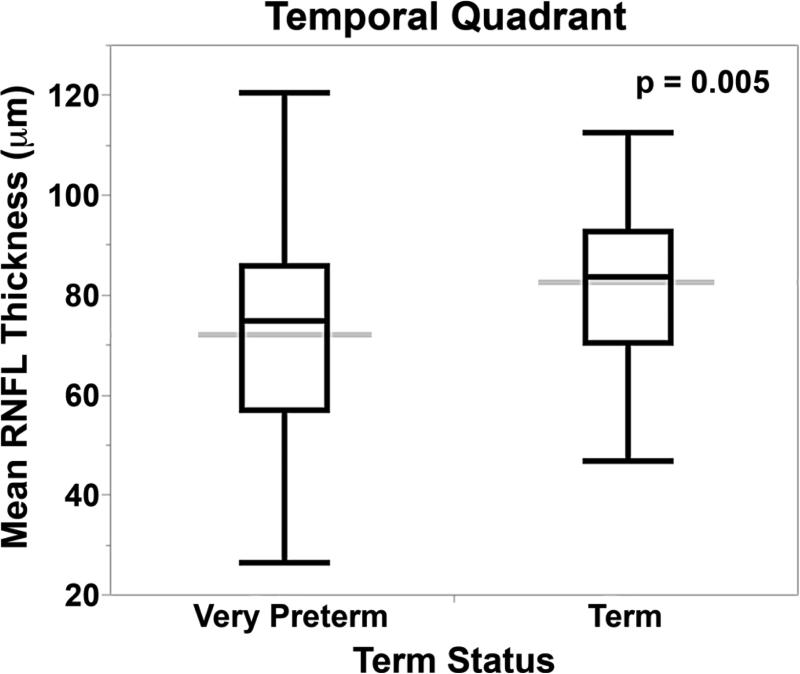

RNFL was thinner for very preterm versus term infants at the papillomacular bundle (61 ± 17 μm versus 72 ± 13, p<0.001) and temporal quadrant (72 ± 21 μm versus 82 ± 16, p=0.005, Figure 3). When considering both term and very preterm infants together, there was a significant but weak relationship between RNFL and both gestational age (papillomacular bundle: R2=0.10, p=0.008; temporal quadrant: R2=0.07, p=0.007) and birth weight (papillomacular bundle: R2=0.10, p=0.001; temporal quadrant: R2=0.08, p=0.003), respectively. Within the very preterm infant cohort, there were no significant differences in mean RNFL thickness across the papillomacular bundle or temporal quadrant by gestational age, age at imaging, birth weight, or ROP severity (data not shown).

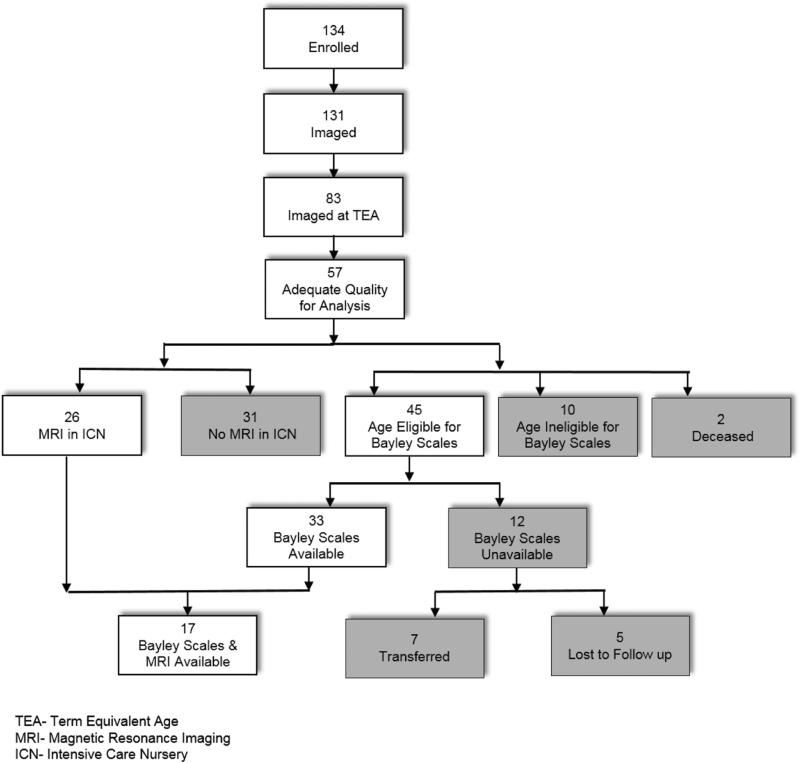

Figure 3.

Mean retinal nerve fiber layer thickness across both the papillomacular bundle and temporal quadrant is thinner in very preterm versus term infants at term-equivalent age. The box and whisker plots represent the median, quartiles, maximums and minimums of each Bayley score for each group. The grey line represents the mean for each group.

Thirty-eight very preterm infants in the current study had their optic nerve parameters previously described.23 These very preterm infants exhibited an inverse correlation between cup-to-disc ratio and mean RNFL thickness across the papillomacular bundle (R2=0.22, p=0.002) and temporal quadrant (R2=0.21, p=0.006). Thirty-seven (65%) very preterm infants had macular edema noted on at least one imaging session but there was no relationship found between mean RNFL thickness across the papillomacular bundle and temporal quadrant by presence of macular edema, or severity of macular edema: maximum central foveal thickness, inner nuclear layer thickness, or foveal-to-parafoveal thickness ratio.

Twenty-seven very preterm infants also had RNFL imaging with SD-OCT at a younger age, <37 weeks post-menstrual age. The mean ages at initial and subsequent (term-equivalent age) SD-OCT imaging were 33.8 ± 1.4 and 38.3 ± 1.6 weeks post-menstrual age, respectively. The mean RNFL thickness measured from initial to subsequent SD-OCT imaging (at term-equivalent age) increased both across the papillomacular bundle as well as the temporal quadrant (mean increases of 15 ± 10 μm (n=27) and 24 ± 15 μm (n=26), respectively, p<0.001 for each). The matched pairs analysis results continued to demonstrate significant thickening from <37 weeks to term-equivalent age when dividing the very preterm infants infants into groups based on need for ROP treatment.

The intraclass correlation coefficient (95% confidence interval) for intergrader, intragrader, and intravisit reproducibilities for very preterm RNFL thickness across the papillomacular bundle were 0.95 (0.87-0.98), 0.95 (0.88-0.98), and 0.92 (0.72-0.98, based on 15 very preterm infants with two reliable SD-OCT scans for RNFL analysis at the same imaging session), respectively.

Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness and Neurologic Health

Twenty-six of the 57 (46%) very preterm infants with full SD-OCT data had a brain MRI ordered in the intensive care nursery and performed at a mean age 44 ± 4 weeks post-menstrual age. Both their gestational age and birth weight were lower than those who did undergo MRI (median age 24 [23-31] versus 26 [24-31] weeks post-menstrual age, respectively, p=0.001; median birth weight 645 [450-1290] versus 940 [580-1400] grams, p<0.001, respectively). There was no significant difference in sex, race/ethnicity, or incidence of ROP requiring treatment between those very preterm infants who did and did not undergo brain MRI. There was a trend towards thinner mean RNFL across the papillomacular bundle in very preterm infants with (57±3.3μm) versus without MRI (66 ± 3 μm, p=0.06) but not across the temporal quadrant (p=0.17).

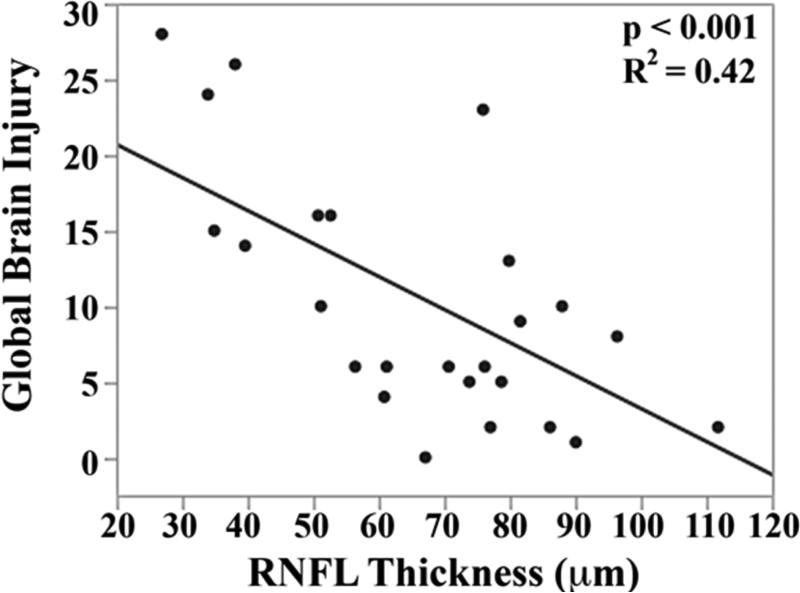

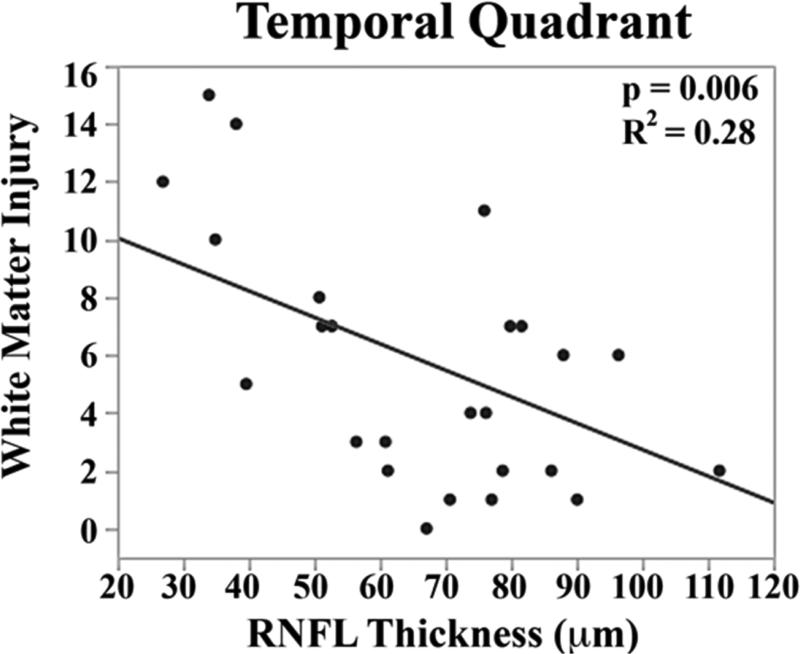

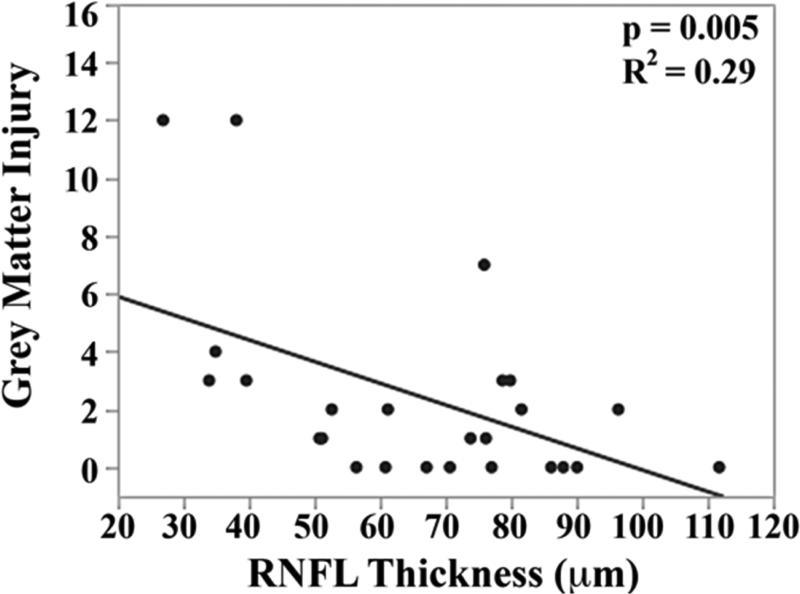

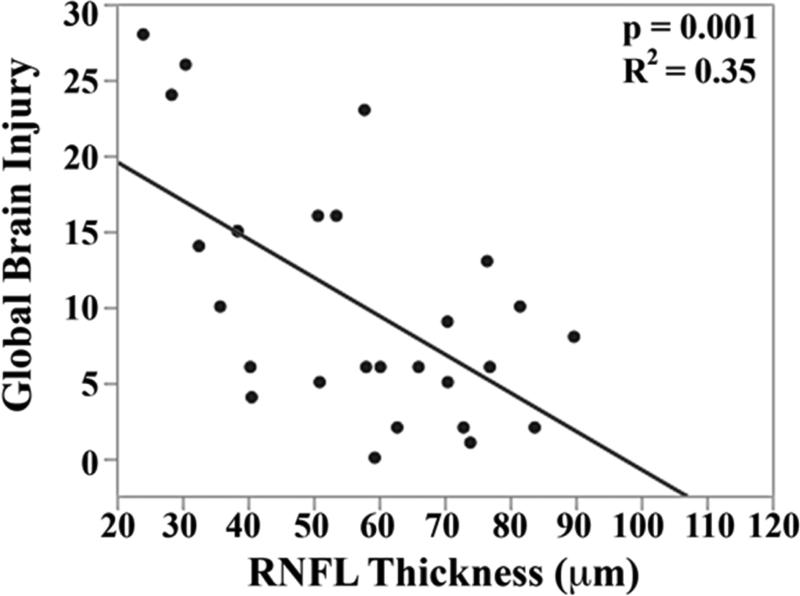

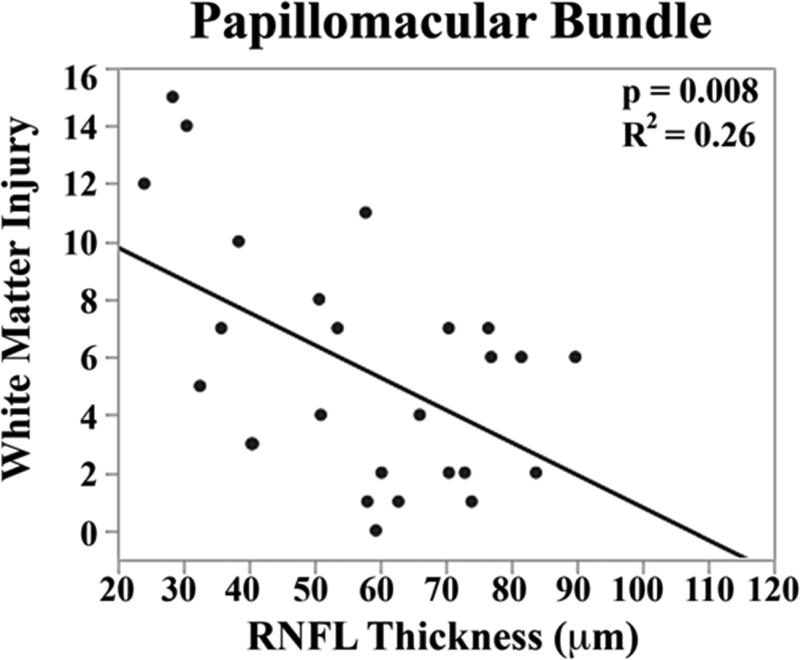

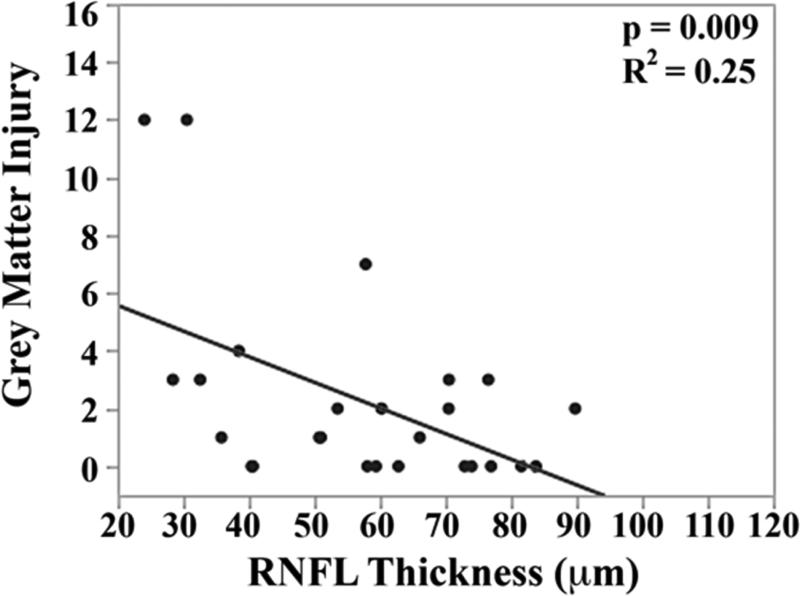

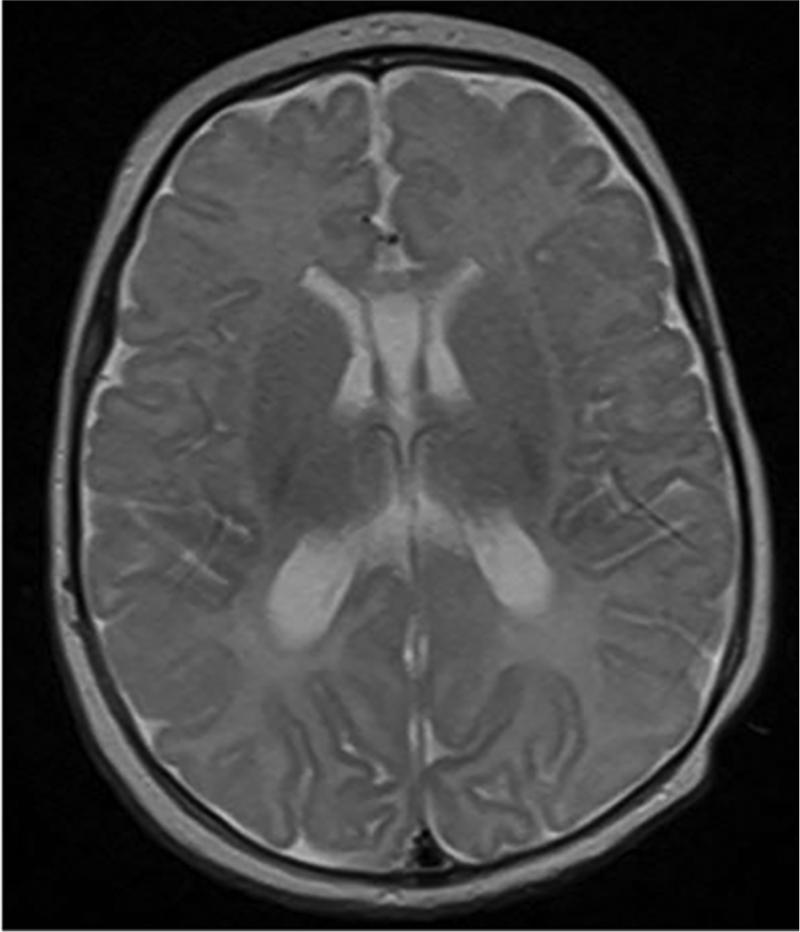

The mean brain injury scores for all very preterm infants with brain MRIs were: global brain MRI lesion burden index of 10 ± 8, regional white matter injury subscore of 6 ± 4, and combined grey matter injury subscore of 2 ± 3. Thinner RNFL correlated with an increase in brain injury on MRI: there was an inverse relationship between mean RNFL thickness across the papillomacular bundle and global brain MRI lesion burden index (p=0.001), regional white matter injury subscore (p=0.008) and combined grey matter injury subscore (p=0.009, Figure 4 top). There was a similar inverse relationship between mean RNFL thickness across the temporal quadrant and global brain injury index (p<0.001), regional white matter injury subscore (p=0.006) and combined grey matter injury subscore (p=0.005, Figure 4 bottom). There was no significant relationship between global, white matter, or grey matter brain lesion indices and any macular edema parameters measured (data not shown). In a multivariate model, when considering mean RNFL across the papillomacular bundle, both RNFL (p<0.001) and birth weight (p=0.03) contributed to global brain lesion burden index (R2=0.47, p<0.001). This relationship was maintained when considering mean RNFL across the temporal quadrant: both RNFL (p<0.001) and birth weight (p=0.02) contributed to global brain lesion burden index (R2=0.55, p<0.001). The present study found no significant relationship between mean RNFL thickness in very preterm infants and systemic factors known to influence health outcomes (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Correlation between mean retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness along the papillomacular bundle, top) and temporal quadrant (bottom) and global brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesion burden index, white matter injury, and grey matter injury for 26 very preterm infants who underwent brain MRI while in the intensive care nursery. Thinner RNFL across either arc (papillomacular bundle or temporal quadrant) correlated with an increase in global brain injury, white matter injury and grey matter injury.

Table 2.

Mean Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness By Systemic Health Factors In Very Preterm Infants

| Papillomacular Bundle | Temporal Quadrant | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | n | Median μm | Range μm | P-Valuea | n | Median μm | Range μm | P-Valuea |

| Hydrocephalus | 0.02 | 0.02 | ||||||

| N | 48 | 65 | 31-90 | 47 | 76 | 35-112 | ||

| Y | 8 | 39 | 24-77 | 8 | 44 | 27-121 | ||

| Culture Positive Sepsis | 0.10 | 0.07 | ||||||

| N | 43 | 65 | 28-90 | 42 | 76 | 34-121 | ||

| Y | 14 | 56 | 24-82 | 14 | 64 | 27-93 | ||

| Culture Negative Sepsis | 0.79 | 0.80 | ||||||

| N | 24 | 64 | 30-89 | 24 | 74 | 37-112 | ||

| Y | 33 | 62 | 24-90 | 32 | 76 | 27-121 | ||

| Urinary Tract Infection | 0.77 | 0.49 | ||||||

| N | 29 | 64 | 30-89 | 28 | 76 | 35-106 | ||

| Y | 28 | 62 | 24-90 | 28 | 73 | 27-121 | ||

| Intraventricular Hemorrhage | 0.30 | 0.14 | ||||||

| Grade 0-2 | 49 | 64 | 28-90 | 48 | 76 | 34-121 | ||

| Grade 3-4 | 7 | 54 | 24-82 | 7 | 53 | 27-88 | ||

| Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia | 0.66 | 0.81 | ||||||

| N | 46 | 64 | 24-90 | 45 | 74 | 27-121 | ||

| Y | 11 | 62 | 28-81 | 11 | 76 | 34-93 | ||

| Postnatal Steroids | 0.65 | 0.52 | ||||||

| N | 19 | 65 | 28-89 | 18 | 77 | 34-106 | ||

| Y | 38 | 62 | 24-90 | 38 | 74 | 27-121 | ||

| Necrotizing Enterocolitis | 0.34 | 0.65 | ||||||

| N | 50 | 63 | 24-90 | 49 | 76 | 27-112 | ||

| Y | 7b | 58 | 30-77 | 7b | 70 | 38-121 | ||

| <5% 36 Week Weightc | 0.25 | 0.36 | ||||||

| N | 18 | 69 | 28-89 | 17 | 78 | 34-121 | ||

| Y | 37 | 60 | 24-90 | 37 | 74 | 27-96 | ||

N, no; Y, yes

P-values calculated with Wilcoxon ranked-sum test. Note with Bonferroni correction a p-value <0.005 is required for statistical significance

Includes one medical necrotizing enterocolitis and six surgical necrotizing enterocolitis cases

Weight at 36 weeks post-menstrual age unavailable for two infants

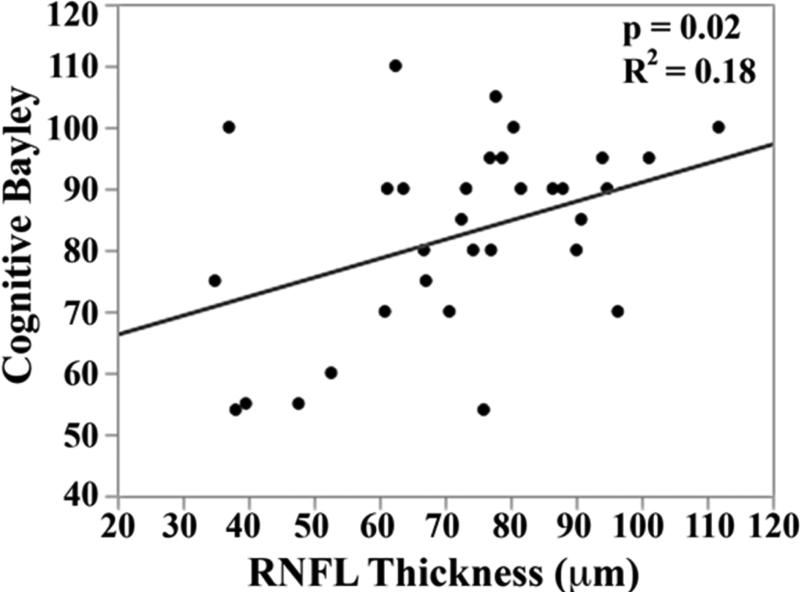

Bayley scores were available for 33 of 45 (73%) age-eligible very preterm infants (Figure 2). For the 33 very preterm infants with Bayley Scales assessment versus those 12 eligible infants who did not have Bayley Scales assessment, there were trends towards lower median gestational age (25 [23-31] versus 27 [23-31] weeks post-menstrual age, respectively, p=0.07) and birth weight (790 [450-1400] versus 990 [635-1360] grams, respectively, p=0.06). There was no significant difference in age at SDOCT imaging, sex, race/ethnicity, eye, ROP severity or mean RNFL thickness across either arc between eligible very preterm infants with and without Bayley Scales assessment.

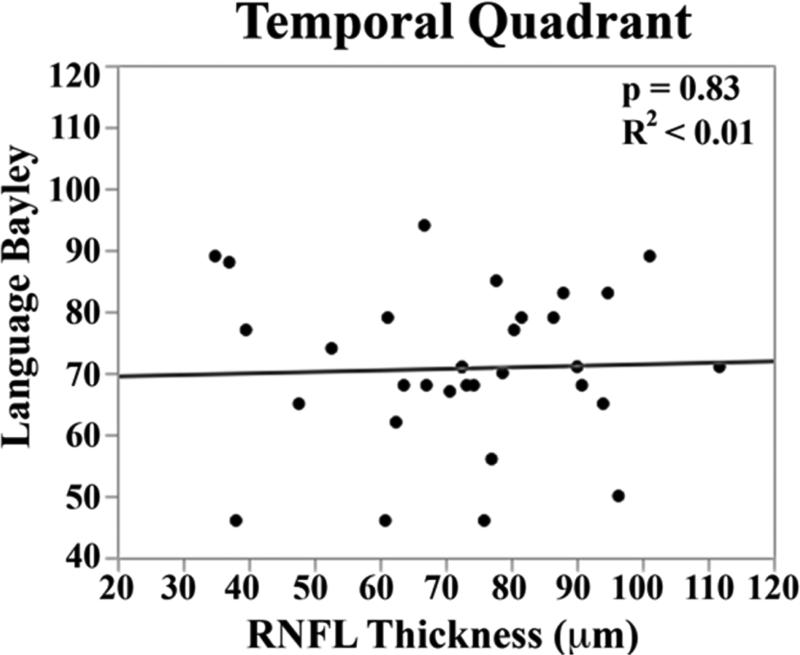

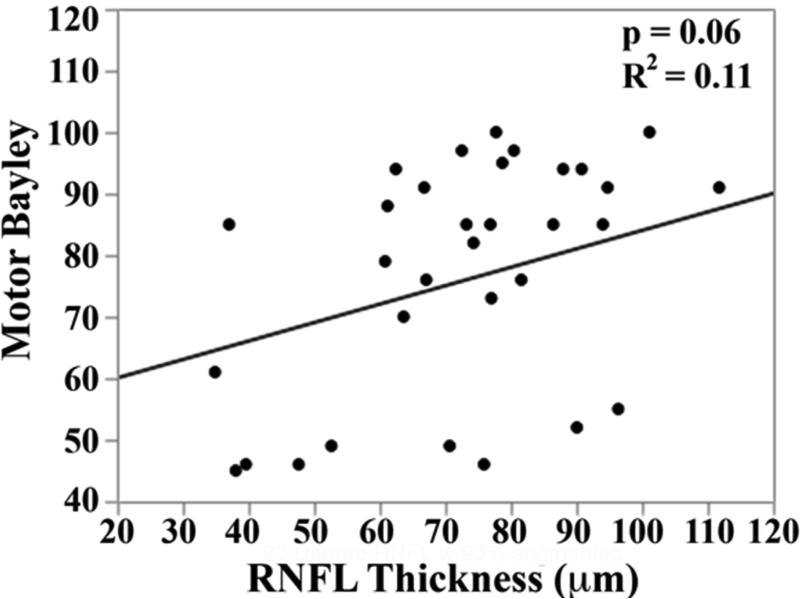

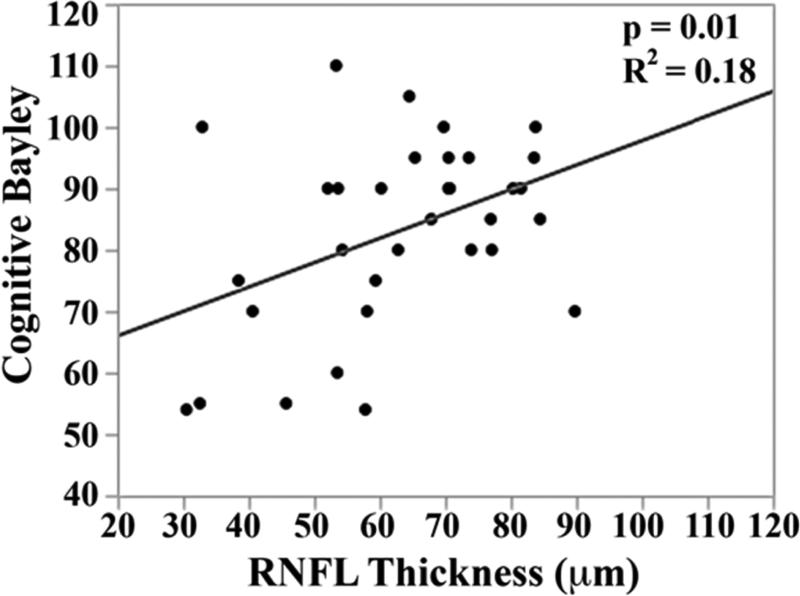

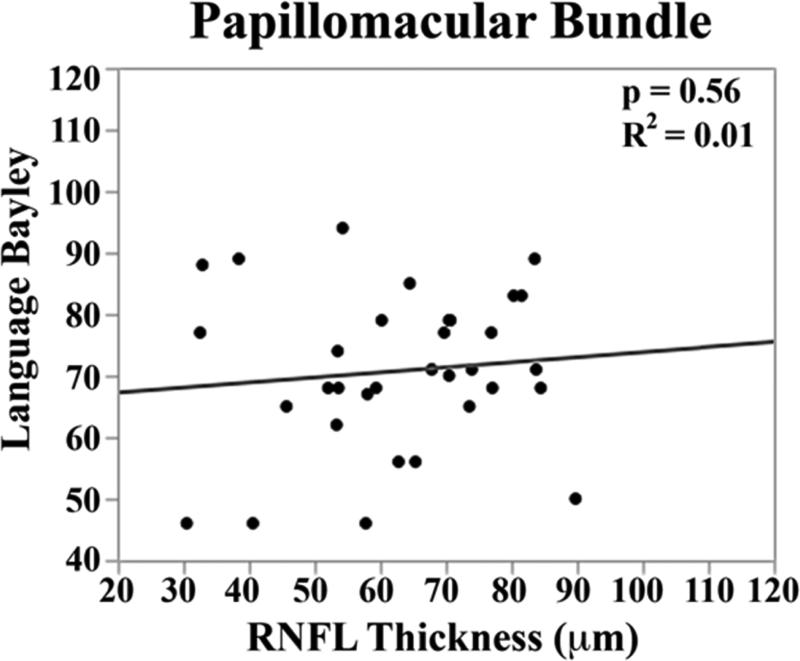

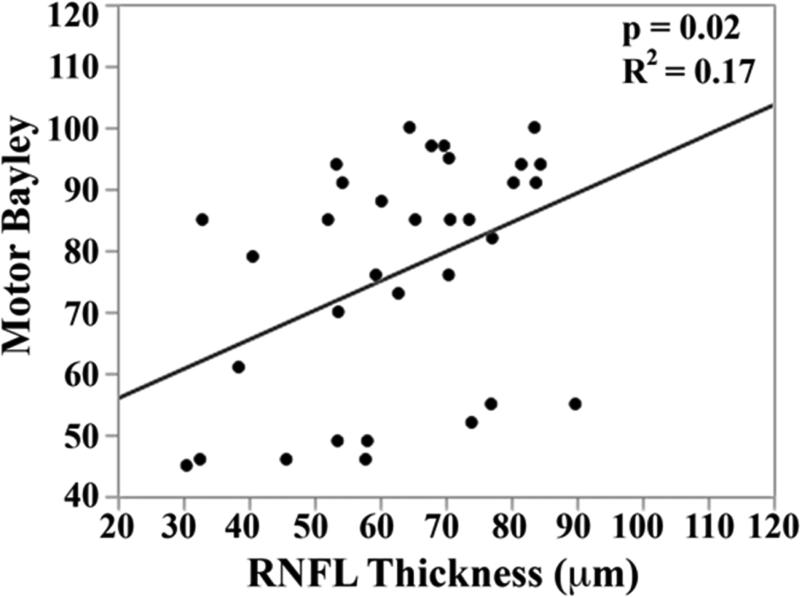

In the univariate analysis, there was a direct relationship between mean RNFL thickness across the papillomacular bundle at term-equivalent age and cognitive (p=0.01) and motor Bayley scores (p=0.02, Figure 5 top). The relationships between mean RNFL thickness and cognitive skills were maintained across the temporal quadrant (p=0.02, Figure 5 bottom). There was a trend towards thinner temporal quadrant RNFL for those with worse motor skills (p=.06). Mean RNFL thickness did not correlate with language Bayley scores across the papillomacular bundle (p=0.56) or temporal quadrant (p=0.83).

Figure 5.

Correlation between mean retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness along the papillomacular bundle, top) and temporal quadrant (bottom) and cognitive, language, and motor skills for 33 very preterm infants assessed at 18-24 months corrected age with the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, 3rd edition. In very preterm infants, thinner RNFL across the papillomacular bundle weakly correlated with poorer cognitive and motor skills as a toddler and across the temporal quadrant weakly correlated with poorer cognitive skills as a toddler.

In the multivariate model, when considering mean RNFL across the papillomacular bundle, both RNFL (p=0.007) and birth weight (p=0.04) contributed to cognitive Bayley scores (R2=0.29, p=0.006). This relationship was maintained when considering mean RNFL across the temporal quadrant: both RNFL (p=0.01) and birth weight (p=0.05) contributed to cognitive Bayley scores (R2=0.28, p=0.008). Within the 17 very preterm infants with both brain MRIs and Bayley Scales follow-up, there was an inverse relationship between near-term global brain injury index and cognitive (R2=0.47, p=0.003) and motor (R2=0.30, p=0.02), but not language skills (R2=0.04, p=0.41).

Discussion

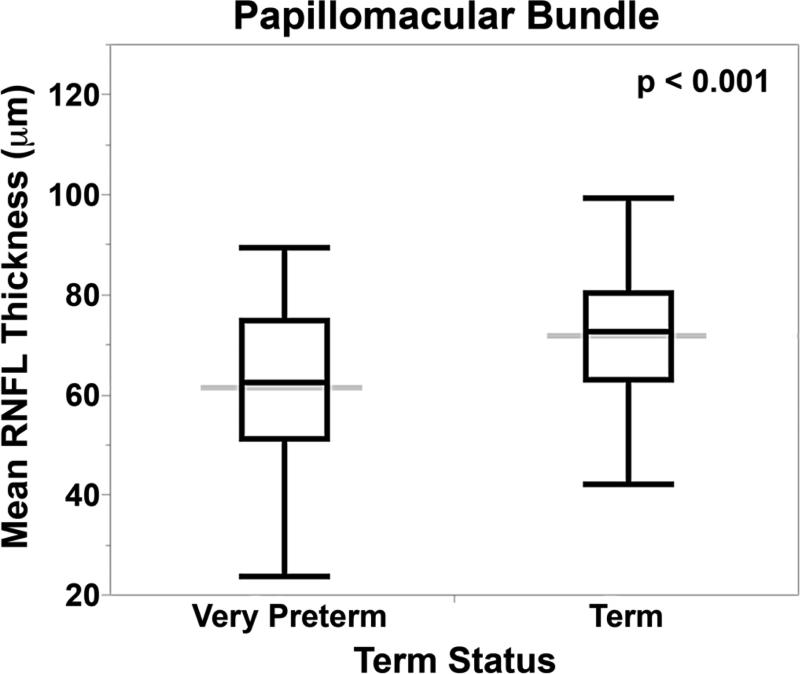

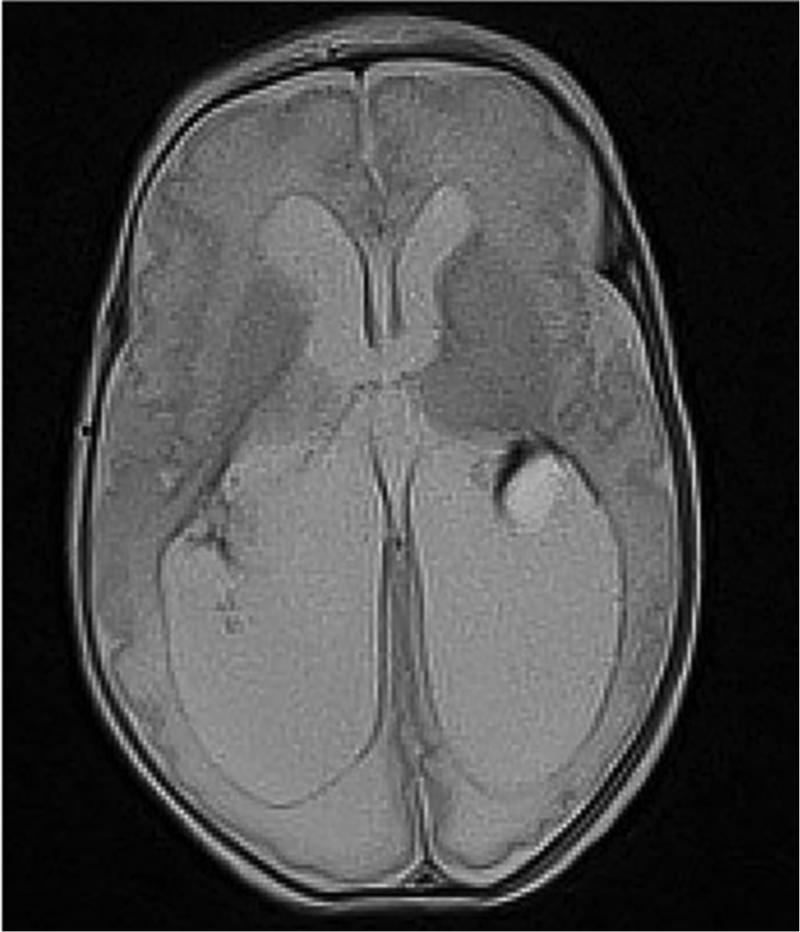

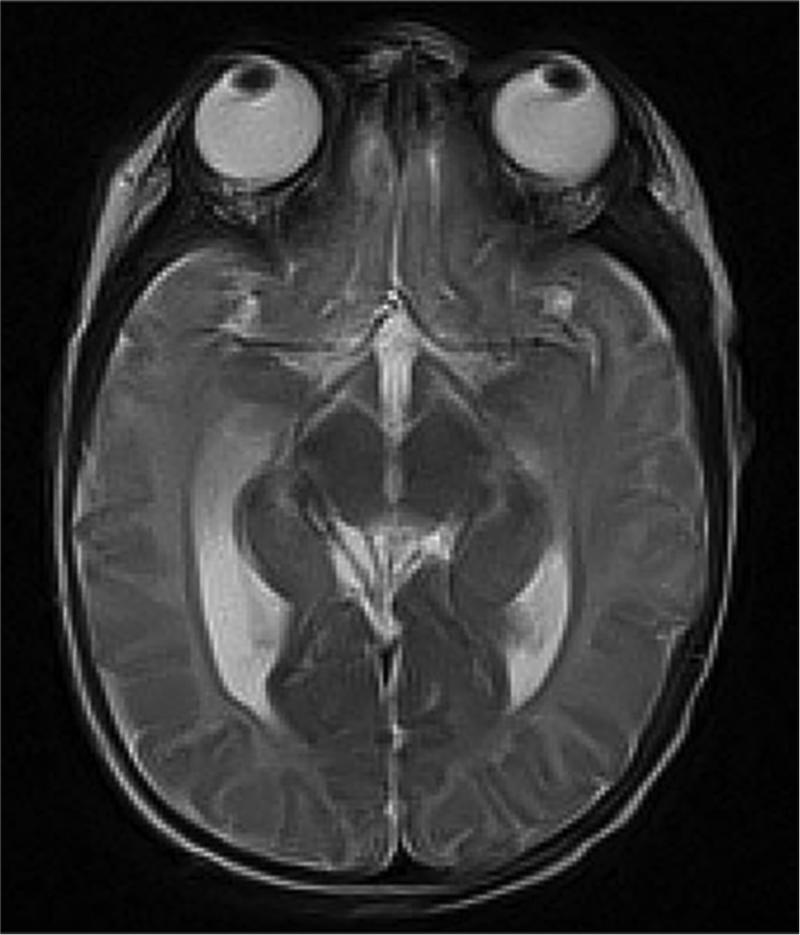

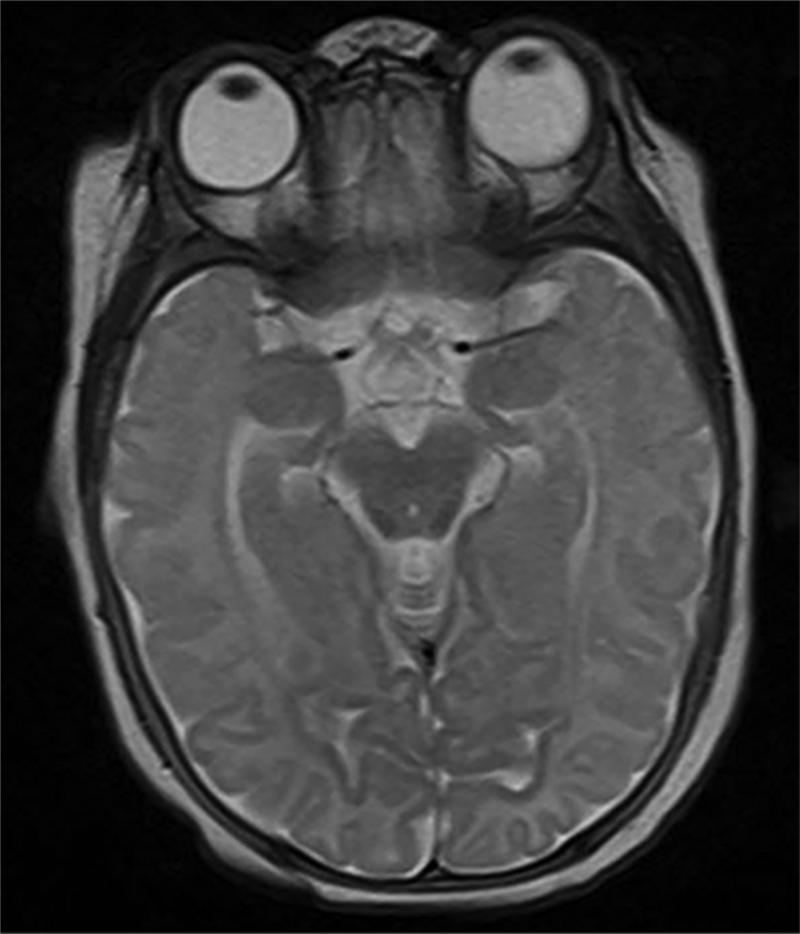

Novel applications of SD-OCT imaging technology and image analysis allow us to assess RNFL thickness in very preterm and term infants in a reproducible manner and over time. Compared to healthy term infants, term-equivalent age very preterm infants have thinner papillomacular bundle and temporal RNFL. In very preterm infants, the RNFL increases in thickness between a young age (30-36 weeks post-menstrual age) and term-equivalent age (37-42 weeks post-menstrual age). Thinner RNFL at term-equivalent age in very preterm infants correlated with greater brain injury burden on near-term MRI (Figure 6), which appears to contribute to worse cognitive and motor skills as a toddler.

Figure 6.

Very preterm infant retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness maps at term equivalent age (left column) and their corresponding near-term T2 weighted brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, middle, right columns). Top, Black female born at 24 weeks gestational age and 640 g who developed plus disease requiring laser treatment. RNFL thickness map at 37 weeks post-menstrual age measures mean RNFL thickness across the papillomacular bundle (thick pink arc) and temporal quadrant (thin pink arc) of 73 and 86 μm, respectively. Brain MRI at 44 weeks post-menstrual shows a near normal global brain with global brain MRI lesion burden index of 2 (due to a white matter subscore of 2). Middle, Black female born at 23 weeks gestational age and 475 g who developed stage 3 retinopathy of prematurity requiring laser treatment. RNFL thickness map at 37 weeks post-menstrual age measures mean RNFL thickness across the papillomacular bundleand temporal quadrants of 51 and 74 μm, respectively. Brain MRI at 46 weeks post-menstrual age had a global brain MRI lesion burden index of 5 (white matter subscore of 4 and grey matter score of 1). The ventricles are mildly enlarged, especially in the occipital lobe area, consistent with mild white matter volume loss. Bottom, White male born at 25 weeks gestational age and 810 g who developed stage 3 retinopathy of prematurity requiring laser treatment. Cognitive, language, and motor Bayley subscores at 18-24 months corrected age were 75, 89, and 61, respectively. RNFL thickness map at 38 weeks post-menstrual age had mean RNFL thicknesses across the papillomacular bundle and temporal quadrants of 35 and 38 μm, respectively. Brain MRI at 36 weeks post-menstrual age had a global brain MRI lesion burden index of 15 (white matter subscore of 10 and grey matter subscore of 4). The ventricles are markedly enlarged, consistent with severe white matter volume loss.

Neonatal retinal and optic nerve microanatomy both differ between term and preterm infants on SD-OCT analyses. Maldonado et al. demonstrated from SD-OCT imaging a dynamic macular layer development and migration after preterm birth.20 The anatomic correlation to the changes in retinal layers by age was subsequently developed from histologic specimens,22, 31 Vajzovic et al. identified a lack of photoreceptor maturation at term-equivalent age in very preterm infants compared to term infants, and this was predominantly driven by photoreceptor immaturity in eyes with macular edema.25 The current study did not identify a relationship between macular edema and RNFL thickness in the papillomacular bundle or temporal quadrant. Tong et al. identified a larger vertical optic nerve cup and cup-to-disc ratio in preterm compared to term infants,23 and this current study demonstrates this difference in neuronal tissue with the more precise measurement of a thinner RNFL in very preterm versus term infants. The increase in RNFL thickness with age possibly represents an increase in the thickness of the ganglion cell axons, which are unmyelinated anterior to the lamina cribrosa. This may be similar and parallel to the increase in the volume of the largely unmyelinated grey matter seen on serial MRI of premature infants in this same time frame.32

Several studies in school-age children have associated thinner RNFL with prematurity13, 16, 17 and lower birth weight.14, 15 Akerblom et al. attributed thinner RNFL thickness by lower gestational age to thinner RNFL in the children with a history of severe ROP.16 Recently, Pueyo et al. found an association between perinatal infections and hypoxic-ischemic events and thinner RNFL measured in school-age children with a history of early prematurity and ROP treatment.17 Across the present study's very preterm and term infants, differences in RNFL thickness--previously reported by term status, gestational age, and birth weight--are now identified during infancy and demonstrate that this is not a later developmental change. In contrast to Akerblom et al.,16 there was no relationship between RNFL thickness and ROP or other systemic health factors (Table 2) within the very preterm cohort. Rather, in this study RNFL thickness appeared to correlate with birthweight, gestational age and MRI abnormality, suggesting that these differences are not a later developmental change. The relationship presently identified between very preterm infant RNFL and MRI may relate to Pueyo et al.'s hypothesis that perinatal events influence neuronal development and maturation observed in the eye.17

Studies in adults suggest that anterior visual pathway abnormalities, specifically, abnormal RNFL thicknesses from OCT, correlate with overall central nervous system health. Thinning of the unmyelinated RNFL tissue is proposed to represent decreased axonal density that correlates with brain atrophy. Gordon-Lipkin et al. found a correlation between brain atrophy on MRI and RNFL thickness in adults with multiple sclerosis, a disease marked by both demyelination and axonal loss.8 Frohman et al also demonstrated correlation of brain MRI, including diffusion tensor imaging parameters, with thinner RNFL in patients with multiple sclerosis versus controls.9 Grazioli et al. related RNFL thinning in adults with multiple sclerosis to MRI parameters and functional disability.10 Similar findings have been reported in individuals with Alzheimer disease11 and Parkinson disease.12 Avery and colleagues demonstrated a correlation between circumpapillary RNFL thinning and vision loss from more localized visual pathway disease, optic pathway glioma, for young children imaged with SD-OCT while under sedation.33

Previous literature in adults suggests that differences in RNFL tissue in the setting of optic neuropathies can be detected and monitored circumpapillary or across the papillomacular bundle.8-10 Circumpapillary RNFL thickness can also be measured reproducibly in sedated children.34 The RNFL temporal to the optic nerve rather than circumpapillary was measured in term infants and this study. This was because SDOCT scans were captured to optimize macular imaging and imaging of the nasal retina in supine neonates is more technically difficult and time consuming in supine, nonsedated infants. One initial concern with expanding the arc of RNFL measurement beyond the papillomacular bundle and towards the vessel arcades in very preterm infants was the possible influence of plus disease on RNFL measures. However, there was no difference noted in the mean incremental increase in RNFL thickness that occurred by enlarging the measured arc from the papillomacular bundle (−15° to +15°) to the temporal quadrant (−45° to +45°) by ROP seve rity or presence versus absence of plus disease. Expanding the region of interest to include the entire temporal quadrant may provide an RNFL thickness average less likely to be influenced by minor variations, and a measure that translates more readily to the clinical setting.35 Using either measure we found a significant relationship in very preterm infants between RNFL and brain injury which then related to neurodevelopment.

MRI-based studies of brain development in at-risk premature newborns during the first few months after birth have begun to show consistent findings and differences at term-equivalent age compared to term infants. 36 Brain MRI studies in individuals with a history of prematurity have reported relationships between white matter injury and neurodevelopment.37-39 Relevant to our work with retinal imaging, Lennartsson et al. reported thinning of RNFL in adults with a history of white matter injury related to premature birth;40 furthermore, RNFL thinning was commensurate with the extent of white matter injury and corresponded to damage in the optic radiations using fiber tractography. The current study suggests that bedside SD-OCT assessment of neonatal RNFL thickness may be a promising biomarker for greater central nervous system injury during the most vulnerable time for brain maldevelopment in at-risk newborns.

RNFL thickness and neonatal macular edema (also known as macular edema of prematurity), are likely to be distinct microanatomic biomarkers of health. The proposed mechanism that connects central nervous system atrophy to RNFL thinning is retrograde trans-synaptic degeneration of ganglion cells.41 Experimental primate models demonstrate uniform, descending axonal degeneration following mechanical injury,42 and this degeneration and/or abnormal development of these structures are likely pathways leading to thinner RNFL and a larger cup-to-disc ratio. On the other hand, neonatal macular edema is not related to the RNFL thinning and may instead reflect vascular endothelial growth factor levels, inflammation or other health issues 21, 24, 43

There are several limitations to this study. Although distribution of gender and race differed between the term and very preterm groups, in a previous analysis RNFL thickness across the papillomacular bundle did not differ by gender or race within the term cohort26 and the difference in RNFL thickness by term status remained significant after correcting for sex and race. Although SD-OCT scans were registered and organized relative to the optic nerve to fovea axis, variability in RNFL measurements due to tilt, or distortion of perivascular tissue may still exist, and image quality could vary by infant and SD-OCT system. Lateral SD-OCT measurements in neonates are based on an age-dependent model described by Maldonado et al.18 Previous research demonstrates no significant relationship between age at imaging and RNFL thickness in term infants imaged at birth26 and the current study again found no relationship between age at imaging over this 37-42 week post-menstrual age time window and RNFL thickness in very preterm infants.

A notable limitation in this study is the inclusion of infants who had either laser (n=18) or bevacizumab (n=2) treatment. The impact of these treatments on RNFL development is unknown. While some SD-OCT scans were obtained after ROP treatment, very preterm infants with and without treatment exhibited similar changes in RNFL thickness from <37 weeks post-menstrual age to term-equivalent age. Further research is needed to establish the effect of laser photocoagulation and bevacizumab on RNFL development. Brain MRIs were available only if deemed clinically indicated by the intensive care nursery team; very preterm infants in this study's cohort who had brain MRI had significantly lower gestational age and birth weight and a trend towards thinner RNFL across the papillomacular bundle than those without brain MRI. Bayley scores were not available on all very preterm infants. There was a trend towards Bayley scores for younger and smaller infants, which suggests a study cohort skewed towards children with more pronounced developmental delays whose families were compliant with routine follow-up.44 We recognize that several systemic health, environmental and socio-economic factors influence neurodevelopmental outcomes, the evaluation of which is beyond the scope of the current study. These limitations of a first in human pilot study point to the importance of a larger study that could support, for example, standardized MRI for all participants and sub group analyses (e.g. with and without ROP treatment).

Despite these limitations, this multidisciplinary study demonstrates the utility of SD-OCT as a research imaging modality that can increase our understanding of eye development and maturation. Mean RNFL thickness measurements can be reproducibly obtained over time in the very preterm population. The anatomic abnormalities detected and monitored in the neural retina appear to reflect the brain as a whole, and likely the visual pathway. Future study will be important to explore these relationship between RNFL thickness, visual pathway development, and functional vision and neurodevelopmental outcomes. These studies could also take advantage of diffusion tensor imaging and resting state functional MRI to explore more nuanced functional and connectivity relationships rather than strictly anatomic correlations.

Acknowledgements

A) Funding/Support: Dr. Toth was supported by The Hartwell Foundation (Memphis, TN), The Andrew Family Charitable Foundation (Framingham, MA), Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY), Grant Number 1UL1RR024128-01 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH, Bethesda, MD), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research (Bethesda, MD). The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (Rockville, MD) of the National Institutes of Health supported both Dr. Shimony under the P30HD062171 to the Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center at Washington University and Drs. Cotten and Gustafson under the 5U10 HD040492-10 to Duke University. Dr. Shimony also received funding from The McDonnell Centers for Systems Neuroscience and Cellular & Molecular Neurobiology (St. Louis, MO). All contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NIH. The sponsors or funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

B) Financial Disclosures: Dr. Toth receives royalties through her university from Alcon and research support from Bioptigen (Research Triangle Park, NC) and Genentech (South San Francisco, CA). She also has unlicensed patents pending in OCT imaging and analysis. Dr. El-Dairi has served as a consultant for Prana Pharmaceuticals (Parkville, Australia). No authors have a proprietary interest in the current study.

C) Other Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Sina Farsiu, PhD (Duke University Eye Center), for use of segmentation software, Sandra S. Stinnett, DrPH (Duke University Eye Center), for statistics consultation, Amy Tong, MD (Duke University Eye Center), and Du Tran-Viet, BS (Duke University Eye Center), for data acquisition, and Vincent Tai, MS (Duke University Eye Center), for assistance with image processing.

Biography

Adam Rothman graduated from Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC after receiving his undergraduate degree summa cum laude from the University of Florida. He will continue his medical training with an ophthalmology residency at Duke University. His research interests include optical coherence tomography imaging and pediatric vitreoretinal diseases.

Adam Rothman graduated from Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC after receiving his undergraduate degree summa cum laude from the University of Florida. He will continue his medical training with an ophthalmology residency at Duke University. His research interests include optical coherence tomography imaging and pediatric vitreoretinal diseases.

Cynthia A. Toth, the Joseph AC Wadsworth Professor of Ophthalmology and Biomedical Engineering at Duke University, Durham, NC, is a clinician-scientist, vitreoretinal surgeon. She directs the Duke Advanced Research in SS/SDOCT Imaging Laboratory. Her translational research interests include ophthalmic diagnostics outside of conventional clinical settings, microsurgical instrumentation, and novel imaging biomarkers to improve the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes for adults and children with vitreoretinal disease.

Cynthia A. Toth, the Joseph AC Wadsworth Professor of Ophthalmology and Biomedical Engineering at Duke University, Durham, NC, is a clinician-scientist, vitreoretinal surgeon. She directs the Duke Advanced Research in SS/SDOCT Imaging Laboratory. Her translational research interests include ophthalmic diagnostics outside of conventional clinical settings, microsurgical instrumentation, and novel imaging biomarkers to improve the diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes for adults and children with vitreoretinal disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Woodward LJ, Clark CA, Bora S, Inder TE. Neonatal white matter abnormalities an important predictor of neurocognitive outcome for very preterm children. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y, Inder TE, Neil JJ, et al. Cortical structural abnormalities in very preterm children at 7years of age. Neuroimage. 2015;109:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pineda RG, Tjoeng TH, Vavasseur C, Kidokoro H, Neil JJ, Inder T. Patterns of altered neurobehavior in preterm infants within the neonatal intensive care unit. J Pediatr. 2013;162(3):470–476. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukherjee P, McKinstry RC. Diffusion tensor imaging and tractography of human brain development. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2006;16(1):19–43, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.nic.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Msall ME, Phelps DL, Hardy RJ, et al. Educational and social competencies at 8 years in children with threshold retinopathy of prematurity in the CRYO-ROP multicenter study. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):790–799. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogawa S, Takemura H, Horiguchi H, et al. White matter consequences of retinal receptor and ganglion cell damage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(10):6976–6986. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simao LM. The contribution of optical coherence tomography in neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2013;24(6):521–527. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon-Lipkin E, Chodkowski B, Reich DS, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer is associated with brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2007;69(16):1603–1609. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000295995.46586.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frohman EM, Dwyer MG, Frohman T, et al. Relationship of optic nerve and brain conventional and non-conventional MRI measures and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness, as assessed by OCT and GDx: a pilot study. J Neurol Sci. 2009;282(1-2):96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grazioli E, Zivadinov R, Weinstock-Guttman B, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness is associated with brain MRI outcomes in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2008;268(1-2):12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paquet C, Boissonnot M, Roger F, Dighiero P, Gil R, Hugon J. Abnormal retinal thickness in patients with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett. 2007;420(2):97–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.02.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Martin E, Satue M, Fuertes I, et al. Ability and reproducibility of Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography to detect retinal nerve fiber layer atrophy in Parkinson's disease. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(10):2161–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang J, Spencer R, Leffler JN, Birch EE. Characteristics of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer in preterm children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(5):850–855. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tariq YM, Pai A, Li H, et al. Association of birth parameters with OCT measured macular and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(3):1709–1715. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang XY, Huynh SC, Rochtchina E, Mitchell P. Influence of birth parameters on peripapillary nerve fiber layer and macular thickness in six-year-old children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(3):505–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akerblom H, Holmstrom G, Eriksson U, Larsson E. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in school-aged prematurely-born children compared to children born at term. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(7):956–960. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-301010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pueyo V, Gonzalez I, Altemir I, et al. Microstructural Changes in the Retina Related to Prematurity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(4):797–802. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maldonado RS, Izatt JA, Sarin N, et al. Optimizing hand-held spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging for neonates, infants, and children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(5):2678–2685. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothman AL, Tran-Viet D, Vajzovic L, et al. Functional outcomes of young infants with and without macular edema. Retina. 2015 Apr 29; doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000579. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000000579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maldonado RS, O'Connell RV, Sarin N, et al. Dynamics of human foveal development after premature birth. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(12):2315–2325. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maldonado RS, O'Connell R, Ascher SB, et al. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomographic assessment of severity of cystoid macular edema in retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(5):569–578. doi: 10.1001/archopthalmol.2011.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vajzovic L, Hendrickson AE, O'Connell RV, et al. Maturation of the human fovea: correlation of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography findings with histology. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(5):779–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong AY, El-Dairi M, Maldonado RS, et al. Evaluation of optic nerve development in preterm and term infants using handheld spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(9):1818–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothman AL, Tran-Viet D, Gustafson KE, et al. Poorer Neurodevelopmental Outcomes Associated with Cystoid Macular Edema Identified in Preterm Infants in the Intensive Care Nursery. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(3):610–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vajzovic L, Rothman AL, Tran-Viet D, Cabrera MT, Freedman SF, Toth CA. Delay in Retinal Photoreceptor Development in Very Preterm Compared to Term Infants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(2):908–913. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-16021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothman AL, Sevilla MB, Freedman SF, et al. Assessment of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in healthy, full-term neonates. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(4):803–811. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kidokoro H, Neil JJ, Inder TE. New MR imaging assessment tool to define brain abnormalities in very preterm infants at term. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(11):2208–2214. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albers CA, Grieve AJ. Review of Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development. J Psychoed Assess. 2007;25(2):180–190. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fierson WM. Screening examination of premature infants for retinopathy of prematurity. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):189–195. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fenton TR, Kim JH. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendrickson A, Possin D, Vajzovic L, Toth CA. Histologic development of the human fovea from midgestation to maturity. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(5):767–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mewes AU, Huppi PS, Als H, et al. Regional brain development in serial magnetic resonance imaging of low-risk preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):23–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Avery RA, Hwang EI, Ishikawa H, et al. Handheld optical coherence tomography during sedation in young children with optic pathway gliomas. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(3):265–271. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.7649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avery RA, Cnaan A, Schuman JS, et al. Reproducibility of Circumpapillary Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Measurements Using Handheld Optical Coherence Tomography in Sedated Children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(4):780–787. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rebolleda G, Sanchez-Sanchez C, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Contreras I, Munoz-Negrete FJ. Papillomacular bundle and inner retinal thicknesses correlate with visual acuity in nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(2):682–692. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hart AR, Whitby EW, Griffiths PD, Smith MF. Magnetic resonance imaging and developmental outcome following preterm birth: review of current evidence. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50(9):655–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwata S, Nakamura T, Hizume E, et al. Qualitative brain MRI at term and cognitive outcomes at 9 years after very preterm birth. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1138–1147. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allin MP, Kontis D, Walshe M, et al. White matter and cognition in adults who were born preterm. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e24525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodward LJ, Anderson PJ, Austin NC, Howard K, Inder TE. Neonatal MRI to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(7):685–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lennartsson F, Nilsson M, Flodmark O, Jacobson L. Damage to the immature optic radiation causes severe reduction of the retinal nerve fibre layer - resulting in predictable visual field defects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(12):8278–8288. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jacobson L, Hellstrom A, Flodmark O. Large cups in normal-sized optic discs: a variant of optic nerve hypoplasia in children with periventricular leukomalacia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(10):1263–1269. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100160433007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quigley HA, Davis EB, Anderson DR. Descending optic nerve degeneration in primates. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1977;16(9):841–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vinekar A, Avadhani K, Sivakumar M, et al. Understanding clinically undetected macular changes in early retinopathy of prematurity on spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(8):5183–5188. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-7155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castro L, Yolton K, Haberman B, et al. Bias in reported neurodevelopmental outcomes among extremely low birth weight survivors. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):404–410. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]