Abstract

Giant cell tumor of the larynx (GCTL) is a rare entity; only 34 cases have been reported in the literature. We report a case of GCTL in a 46 year-old male presenting clinical, radiographic, histological and therapeutic features. Previously reported cases are also reviewed.

Keywords: Giant cell, Denosumab, Head and neck surgery, Larynx

Introduction

Giant cell tumor of the larynx (GCTL) is a rare entity with 34 cases reported to date. Giant cell tumor (GCT) occurs most frequently in the epiphysis of the long bones of patients in their third decade and has a slight female predilection [1, 2]. GCT of bone is a benign neoplasm with a 25 % rate of recurrence [2]. Six to ten percent of GCTs exhibit malignant features manifesting as high-grade sarcoma occurring at the site of a prior benign GCT or as a sarcoma in juxtaposition to the GCT [2]. No such association has been recorded in the reported cases of GCTL [2, 3].

Case Report

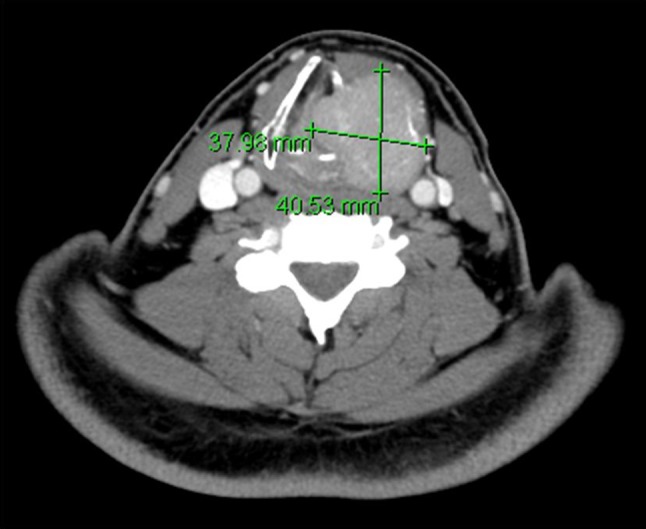

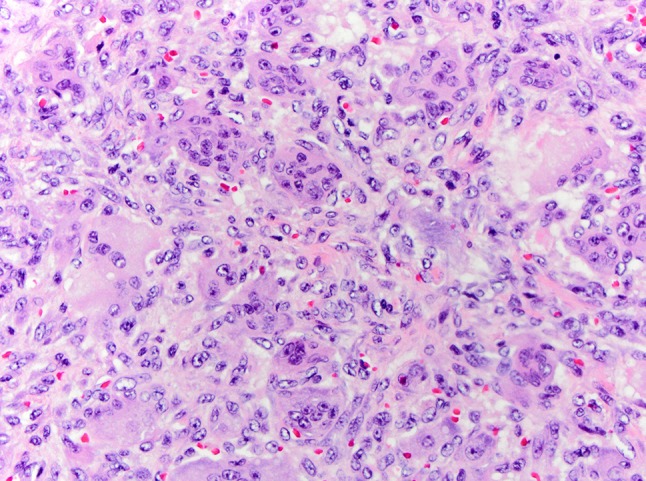

A 46-year-old male was referred to the division of head and neck surgery for evaluation of a left neck mass causing dyspnea. He was otherwise healthy. He denied prior or current tobacco use. A contrast enhanced computerized tomographic scan showed an expansile destructive lesion epicentered on the left thyroid ala with invasion of the overlying strap muscles. The left glottic and supraglottic tissues were involved (Fig. 1). The patient was taken to the operating room for tracheotomy to protect the airway and a subsequent laryngoscopic biopsy was performed. The procedure was tolerated well by the patient and he was discharged without event. Histopathologic review of the material obtained by biopsy revealed only normal laryngeal mucosa. Ten days later the patient underwent an ultrasound-guided trans-cervical core biopsy of the mass. The histopathologic features were interpreted as a giant cell lesion consistent with either a GCT or a giant cell granuloma (GCG) (Fig. 2). Blood chemistry studies demonstrated normal levels of serum calcium. A left hemilaryngectomy with frontolateral extension was planned with the intent of laryngeal preservation. Remaining foci of tumor would be treated with denosumab. Due to strap muscle infiltration by tumor, a supraclavicular pedicle flap was used for reconstruction of the hemilaryngeal defect. Gross examination of the resected specimen revealed a 4.5 × 4.0 × 3.5 cm nodular mass composed of white-tan homogenous, rubbery tissue with a central hemorrhagic focus (Fig. 3). Microscopic examination revealed a cellular neoplasm composed of numerous uniformly distributed osteoclast-like giant cells separated by uniform mononuclear cells whose nuclei resembled those of the giant cells (Fig. 4). The tumor had breached the confines of the bone and cartilage of the thyroid ala and extended into the adjacent soft tissue. Scattered reactive woven bone and occasional mitoses were noted. Microscopic foci of tumor were identified at the margins. Based upon the uniform distribution of the giant cells, a diagnosis of GCT was made. The patient is currently being treated with denosumab.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan demonstrating an expansile destructive lesion epicentered on the left thyroid ala with invasion of the overlying strap muscles and involvement of the left glottic and supraglottic tissues

Fig. 2.

Histopathology hematoxcylin and eosin ×200 original magnification. Core biopsy specimen showing giant cells, a mononuclear population and extravasated erythrocytes

Fig. 3.

Gross specimen. Nodular mass measuring 4.5 × 4.0 × 3.5 cm composed of white-tan homogenous, rubbery tissue with a central hemorrhagic focus

Fig. 4.

Histopathology hematoxcylin and eosin ×400 original magnification. Resection specimen demonstrating numerous uniformly distributed osteoclast-like giant cells separated by mononuclear cells in a vascular stroma

Discussion and Review of the Literature

GCT most commonly occurs in the epiphysis of the long bones, having a predilection for females in their third decade [1, 2]. These tumors are essentially benign, but may be locally aggressive [2]. Significant rates of recurrence have been reported [2]. Histologically, GCTs are composed of a mixture of multinucleated giant cells and mononuclear cells in a fibroblast rich, loose, hemorrhagic, vascular stroma [2]. The nuclei of the giant cells are strikingly similar to those of the monuclear cells [2]. Lau et al. [4] demonstrated that the mononuclear component of GCT expressed alkaline phosphatase and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), markers of osteoblast lineage, while the multinucleate component expressed tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase and vitronectin receptor, markers of osteoclastic lineage.

The head and neck region is an infrequent site for GCTs, which tend to involve the sphenoid, ethmoid and temporal bones [3]. The first case of GCTL was reported by Wesely in 1940 [5–8]. Since then a total of 33 additional cases have been published [3, 5–18].

There is a strong male preponderance (8.5:1) with an average age at diagnosis of 42 years [3, 5–18]. Of the laryngeal structures, the thyroid cartilage is the most common site of origin (21, 60 %), followed by the cricoid cartilage (9, 26 %), the epiglottis (2, 6 %) and the soft tissues of the larynx (2, 6 %) [3, 5–18]. The location of one case was not specified [5–8] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cases of giant cell tumor of the larynx

| Case | Year | Author | Gender | Age (years) | Location | Laterality | Size (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1940 | Wessely | Male | 51 | Cricoid | ||

| 2 | 1951 | Federova | Male | 35 | Thyroid | ||

| 3 | 1952 | Wagemann | Male | 40 | Cricoid | ||

| 4 | 1958 | Perrino | Male | 32 | Cricoid | ||

| 5 | 1966 | Kaliteevskii | Male | 52 | Thyroid | ||

| 6 | 1968 | Pohl | Male | 50 | Thyroid | ||

| 7 | 1969 | Kohn | Male | 50 | Epiglottis | ||

| 8 | 1971 | Rudert | Male | 53 | Thyroid | ||

| 9 | 1973 | Goto | Male | 47 | Thyroid | ||

| 10 | 1975 | Ribari | Male | 35 | Cricoid | “Walnut” | |

| 11 | 1974 | Kotarba | Male | 60 | Epiglottis | ||

| 12 | 1974 | A. Coyas | Male | 67 | Vocal cord | Right | “Hazel nut” and “chick pea” |

| 13 | 1976 | Kubo | Male | 40 | Cricoid | ||

| 14 | 1976 | John Hall-Jones | Male | 26 | Thyroid | Right | 5.5 |

| 15 | 1979 | Tsybyrne | Male | 34 | Thyroid | ||

| 16 | 1988 | Borghese | Male | 28 | Thyroid | ||

| 17 | 1993 | Murrell | Male | 42 | Thyroid | Left | |

| 18 | 1994 | P. C. Martin | Male | 23 | Thyroid | Right | 4 |

| 19 | 1995 | D. M. Thomas | Female | 56 | Cricoid | Bilateral | 2 |

| 20 | 1996 | Jochen A. Werner | Male | 35 | Thyroid | 4.8 | |

| 21 | 2000 | Hinni | Male | 31 | Thyroid | Left | 4 |

| 22 | 2001 | Wieneke | Male | 26 | Thyroid | Right | 4.2* |

| 23 | 2001 | Wieneke | Male | 37 | Thyroid | Left | 4.2* |

| 24 | 2001 | Wieneke | Male | 37 | Cricoid | Right | 4.2* |

| 25 | 2001 | Wieneke | Male | 40 | Thyroid | 4.2* | |

| 26 | 2001 | Wieneke | Male | 44 | Thyroid | Left | 4.2* |

| 27 | 2001 | Wieneke | Female | 53 | Thyroid | 4.2* | |

| 28 | 2001 | Wieneke | Male | 57 | Cricoid | Bilateral | 4.2* |

| 29 | 2001 | Wieneke | Female | 62 | Thyroid | Left | 4.2* |

| 30 | 2003 | Wong | Male | 49 | Thyroid | Left | 4 |

| 31 | 2006 | Nishimura | Male | 31 | Thyroid | Right | 4 |

| 32 | 2011 | Rochanawutanon | Male | 29 | Cricoid ST | Left | 4 |

| 33 | 2013 | C. de la Fouchardiere | Male | 38 | Thyroid | Right | 4 |

| 34 | 2014 | Nota | Male | 59 | Thyroid | Left | 3 |

| 35 | 2015 | Current case | Male | 46 | Thyroid | Left | 4.5 |

* Cases averaged by author

The most commonly reported findings on physical exam were dysphonia (16, 47 %) and a palpable neck mass (15, 44 %). These were followed by respiratory difficulty (6, 18 %) and dysphagia (5, 15 %). Other less common findings included sore throat and changes in vocal cord mobility. Four authors reported normal laboratory values for serum calcium and three reported normal alkaline phosphatase levels, two of which also reported normal levels of parathyroid hormone. In eleven cases a history of tobacco use was elicited and was denied by all [3, 5–18].

The treatment modality was described in 32 of the 34 cases [3, 5–18]. The majority of cases were treated by surgery alone (19, 56 %), ranging from local excision to total laryngectomy. Eight cases were treated by surgery and radiation (24 %), three by radiation alone (9 %) and one case by surgery, radiation and chemo therapy (3 %) [3, 5–18]. Derbel et al. [18] recently reported the use of denosumab following surgery in treating a single case of GCTL (3 %).

In seventeen cases at least one measurement of the tumor was reported clinically, radiographically or by gross examination [3, 5–8, 10, 13, 14, 16–18]. The average dimension was 4.0 cm. The microscopic descriptions were those of classic GCTs consisting of multinucleated giant cells and mononuclear cells with a stroma composed of fibroblasts, marked vascularity, and hemorrhagic foci. While two authors reported thyroid gland displacement by the tumor [10, 18], there were no reports of infiltration of the thyroid gland. Thirty-one cases involved the cartilaginous structures of the larynx, two cases occurred in the soft tissues and one case occurred in an unspecified location [3, 5–18]. It was reported that bone was identified in the microscopic specimens of twelve cases [5–9, 11–14, 16, 18]. This is of interest as aberrations in the maturation and ossification process of cartilaginous structures has been suggested as a possible etiologic factor in the development of giant cell lesions [13]. Mitotic activity was reported in seventeen cases [3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14, 15, 17, 19] but only one of these commented on pleomorphism [9].

A total of 23 cases included follow up information, which ranged from 3 months to 25 years, with an average of 5 years 9 months [3, 4, 7–10, 12–15, 17, 18]. In 22 of these cases, no recurrence or metastasis was reported [3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 12–15, 17, 18]. The case presented by Coyas et al. [9] was reported to have both recurred and metastasized. The initial presentation was that of a soft tissue mass on the right true vocal cord. Radiographic studies showed the tumor to be restricted to the soft tissues of the larynx with no cartilaginous involvement. Following excision, the tumor recurred twice. The patient subsequently underwent radiation therapy after which a tumor of the skin overlying the initial surgical bed developed. The tumor was excised and showed the same giant cell histology as the previously excised lesions. The authors considered this to represent local metastasis [9]. It is likely that the multiple recurrences were related to incomplete excision, rather than metastatic disease [13]. Rochanawutanon et al. [17] also reported of a case of GCTL of the soft tissues. Their case was initially treated by resection and showed no recurrence or metastasis at 11 years [18].

Weineke et al. [3] suggest that GCTL appears to have a less aggressive behavior than its long bone counterpart. Our review of the literature would seem to confirm this view. This, however, may be a reflection of the small number of cases and limited follow-up.

The differential diagnosis for lesions containing numerous osteoclast-like giant cells includes GCT, GCG (also referred to as giant cell reparative granuloma), foreign body giant cell reaction, brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism and giant cell-rich osteosarcoma [3, 13]. In the case of a foreign body giant cell reaction, the distribution of the giant cells would be less regular, their number fewer and they would aggregate around the foreign material. The brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism can appear grossly and microscopically similar to GCT and GCG [20]. It is therefore essential that the patient be evaluated to rule out hyperparathyroidism. In addition to the presence of giant cells, giant cell-rich osteosarcoma should demonstrate the deposition of osteoid in irregular sheets or in a lace-like distribution [22]. Additionally, the osteogenic cells should show some degree of nuclear pleomorphism [22].

As documented in the differential diagnosis of the core biopsy specimen from our patient, the distinction of GCT from GCG can present a challenge to the surgical pathologist. GCG of the head and neck most commonly occurs in the mandible as a central lesion, is more common in females than males and has a predilection for those under 30 years [20]. Both lesions show the presence of numerous giant cells and mononuclear cells, and a stroma rich in fibroblasts and vasculature [3, 19, 20]. GCTs tend to exhibit more uniform distribution of the giant cells as well as giant cells that possess a greater number of nuclei (often exceeding 20) [3]. Thomas et al. [14] reported a giant cell lesion of the larynx that they diagnosed as giant cell reparative granuloma. In their description of the histopathology they mention that areas of the lesion demonstrated features of GCT but the more irregular distribution of giant cells was consistent with giant cell reparative granuloma [14]. Similarly, our case showed somewhat of a bi-phasic pattern.

At least two views concerning the nature of giant cell lesions exist. One posits that GCT and GCG are two distinct entities. GCG occurs in a younger age group (20 vs. 30) and has a lower rate of recurrence (13–35 vs. 60 %) [23]. Furthermore, only isolated cases of metastasis or sarcomatous transformation have been reported with GCG, as opposed to the 6–10 % rate of sarcomatous transformation and 2 % rate of metastasis seen in GCT [23, 24]. Waldron and Shafer [19] point out that these differences may be related to earlier clinical detection and diagnosis in the gnathic locations. They view GCT and GCG as a single entity [19, 20]. Liu et al. [21] provide support for this viewpoint by demonstrating that receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B (RANK) and RANKL (markers of osteoclastic and osteoblastic differentiation) are expressed on lesional cells of both GCT and GCG. Research by Gomes and colleagues indicate these two diseases possess separate molecular profiles. Mutation of the H3F3A gene has been reported in 90 % of GCTs. Gomes et al. [25] evaluated nine cases of GCG for this mutation and found all cases to be negative further supporting the theory that the two entities may indeed be distinct.

Treatment of GCT is an area of continued debate [26]. Localized control can often be achieved by wide resection [26]. Based on our review, wide local resection is a sufficient surgery for GCTL [3, 5–18]. However, this can be problematic in cases where resection may leave a functional deficit or encroach upon vital structures. Some have advocated the use of radiation, but post-radiation sarcoma is of concern [7, 16, 18]. An ideal treatment for GCT has yet to be identified [26, 27].

Presently a multinational clinical trial is being conducted to examine the efficacy of denosumab in the treatment of GCT of bone [27]. Denosumab is a fully-human monoclonal antibody that binds RANKL and inhibits RANK-RANKL interactions [28]. RANK is expressed on the surface of osteoclast precursors. In order to differentiate into osteoclasts, their RANK receptors must interact with RANKL that is expressed on osteoblasts. It is theorized that this interaction is prevented by the presence of denosumab [4, 27, 28]. The most recent data from this trial suggests that denosumab is a viable alternative therapy for GCT of bone when function-sparing surgery is not felt to be possible. While this treatment appears to be effective, 9 % of patients have developed serious adverse side effects in a phase two study. These included hypocalcemia (5 %), osteonecrosis of the jaw (1 %, two of three cases resolved), serious infection (2 %), and a new primary malignancy (1 %) [27]. The use of denosumab should be considered with attention to the renal function of the patient since renal dysfunction increases the risk of hypocalcaemia. Additionally, there have been reports of atypical femoral fractures seen in patients receiving denosumab therapy [29]. However, no causal relationship is known, nor has fracture been documented as a side effect of the medication [29].

Derbel et al. [18] reported their experience in treating a single case of laryngeal GCT with denosumab. Following denosumab treatment, the decision was still made to resect residual tumor by total laryngectomy. Histopathological review of the resection specimen showed a complete absence of giant cells with ossification of the tumor bed [18]. Denosumab therapy was initiated for our patient 2 months following surgery. The patient had no signs of disease recurrence at their 8 months post-surgery follow-up visit.

Conclusions

GCTL is a rare entity with only 34 cases reported in the literature. It has a marked predilection for adult males and most commonly involves the thyroid cartilage. While it appears to respond well to surgical resection, future non-surgical therapies may be considered. We have presented an additional case treated by surgery with adjuvant denosumab treatment, reviewed the literature and discussed the clinical and epidemiological features as well as the differential diagnosis and summary of various treatment modalities.

References

- 1.Dahlin DC, Cupps RE, Johnson EW. Giant-cell tumor: a study of 195 cases. Cancer. 1970;25(5):1061–1070. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197005)25:5<1061::AID-CNCR2820250509>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reid R, Banerjee SS, Sciot R. Giant cell tumours. In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumors. Pathology and genetics of tumors of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. pp. 309–313. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wieneke JA, Gannon FH, Heffner DK, Thompson LD. Giant cell tumor of larynx: a clinicopathologic series of eight cases and review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(12):1209–1215. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lau YS, Sabokbar A, Gibbons C, Giele H, Athanasou N. Phenotypic and molecular studies of giant-cell tumors of bone and soft tissue. Hum Pathol. 2005;36(9):945–954. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Werner JA, Harms D, Beigel A. Giant cell tumor of the larynx: case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 1997;19(2):153–157. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199703)19:2<153::AID-HED12>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong KK, Seikaly H. Giant cell tumour of the larynx: case report and review of the literature. J Otolaryngol. 2004;33(3):195–197. doi: 10.2310/7070.2004.03053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura K, Satoh T, Maesawa C, Ishijima K, Sato H. Giant cell tumor of the larynx: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007;28(6):436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nota J, Okochi Y, Watanabe F, Saiki T. Laryngeal giant cell tumor: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2014;2014:5035947. doi: 10.1155/2014/503497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coyas A, Anastassiades OT, Kyriakos I. Malignant giant cell tumour of the larynx. J Laryngol Otol. 1974;88(8):799–803. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100079378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall-Jones J. Giant cell tumour of the larynx. J Laryngol Otol. 1972;86(04):371–381. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100075393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribari O, Elemer G, Balint A. Laryngeal giant cell tumour. J Laryngol Otol. 1975;89(8):857–861. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100081123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murrell GL, Lantz HJ. Giant cell tumor of the larynx. Ear Nose Throat J. 1993;72(5):360–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin PC, Hoda SA, Pigman HT, Pulitzer DR. Giant cell tumor of the larynx: case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1994;118(8):834–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas DM, Wilkins MJ, Witana JS, Cook T, Jefferis AF, Walsh-Waring GP. Giant cell reparative granuloma of the cricoid cartilage. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109(11):1120–1123. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100132190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iype EM, Abraham EK, Kumar K, Pandey M, Prabhakar J, Ahamed MI, et al. Giant cell tumour of hyoid bone: case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;38(6):610–611. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2000.0483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hinni ML. Giant cell tumor of the larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109(1):63–66. doi: 10.1177/000348940010900112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rochanawutanon M, Praneetvatakul P, Laothamatas J, Sirikulchayanonta V. Extraskeletal giant cell tumor of the larynx: case report and review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2011;90(5):226–230. doi: 10.1177/014556131109000509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Derbel O, Zrounba P, Chassagne-Clément C, Decouvelaere AV, Orlandini F, Duplomb S, et al. An unusual giant cell tumor of the thyroid: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(1):1–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waldron CA, Shafer WG. The central giant cell reparative granuloma of the jaws. An analysis of 38 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45(4):437–447. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/45.4.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 3. St. Louis: Saunders; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu B, Yu SF, Li TJ. Multinucleated giant cell in various forms of giant cell containing lesions of the jaws express features of osteoclasts. J Oral Pathol Med. 2003;32(6):367–375. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2003.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzales AL, Cates JMM. Osteosarcoma: differential diagnostic considerations. Surg Pathol Clin. 2012;5:117–146. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sciubba JJ, Fantasia JE, Kahn LB. Atlas of tumor pathology: tumors and cysts of the jaws. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mintz GA, Abrams AM, Carlsen GD, Melrose RJ, Fister HW. Primary malignant giant cell tumor of the mandible: report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;51(2):164–171. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(81)90035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gomes CC, Diniz MG, Amaral FR, Guimaraes BVA, Gomez RS. The highly prevalent H3F3A mutation in giant cell tumours of bone is not shared by sporadic central giant cell lesions of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014;118:583–585. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H, Wan N, Hu Y. Giant cell tumour of bone: a new evaluating system is necessary. Int Orthop. 2012;36(12):2521–2527. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1664-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chawla S, Henshaw R, Seeger L, Choy E, Blay JY, Ferrari S, et al. Safety and efficacy of denosumab for adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumour of bone: interim analysis of an open-label, parallel-group, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(9):901–908. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70277-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boyce BF, Xing L. Biology of RANK, RANKL, and osteoprotegrin. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(Suppl 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/ar2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bone HG, Chapurlat R, Brandi ML, Brown JP, Czerwinski E, Krieg MA, et al. The effect of three or six years of denosumab exposure in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: results from the FREEDOM extension. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):4483–4492. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]