Abstract

Eagle’s Syndrome (ES) refers to a symptomatic anomaly due to elongation of the styloid process or mineralization of the styloid complex. If not diagnosed timely and treated properly, elongation of the styloid process or the hyper-mineralization of the stylohyoid ligament may eventually lead to complete ossification of the stylohyoid complex. Non-specific head and neck symptoms of the ES may pose diagnostic challenges to the clinician. Therefore it is crucial to include ES among differential diagnosis when evaluating patients with similar head and neck symptoms. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, treatment plan should be tailored in accordance with the individual requirements of the case and performed without delay. Both pharmacological and surgical methods have been described for the treatment of the patients with ES. However for those who suffer from persistent symptoms, surgical removal of the elongated styloid process is the treatment of choice and can be done with an intraoral or an extraoral approach. The aim of this work is to present unusual clinical symptoms and radiologic findings of ES due to complete ossification of the stylohyoid complex. The importance of a correct diagnosis and appropriate treatment are highlighted.

Keywords: Eagle’s Syndrome, Ossification, Stylohyoid, Hypoglossal nerve palsy

History

A 48-year-old female patient with non-significant past medical history was referred for evaluation and management of unilateral weakness of her tongue. Among her initial complaints were sharp lancinating pain on swallowing, altered speech, dry mouth, left neck swelling, and intermittent loss of taste.

Radiographic Features

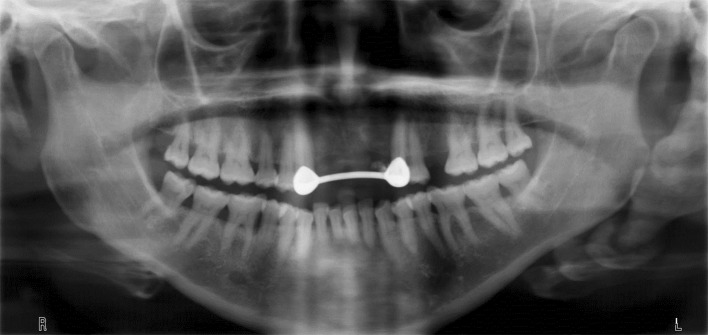

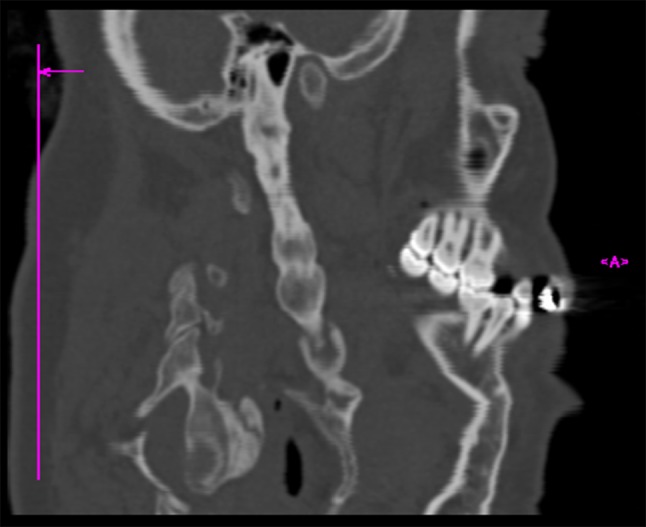

Initial radiographic examination was carried out with a panoramic radiograph, which revealed a voluminous ossified stylohyoid complex on the patient’s left side (Fig. 1). Computerized tomography (CT) imaging was obtained to further evaluate the true dimension and angulation of the calcified tissue. Sagittal view (Fig. 2) and the three-dimensional CT reconstruction (Fig. 3) demonstrated complete ossification of the stylohyoid complex.

Fig. 1.

Panoramic radiograph of the patient showing large ossified stylohyoid complex

Fig. 2.

Sagittal CT view of the head and neck reveals extensively calcified stylohyoid complex

Fig. 3.

Three-dimensional CT reconstruction demonstrates complete ossification of the stylohyoid complex extending from the temporal bone to the hyoid bone

Diagnosis

Clinical examination of the patient revealed a fixated mass, which was firm on palpation in the left submandibular region. Manual palpation of the left tonsillar fossa caused discomfort and confirmed the presence of a solid mass. Marked left sided hemi-atrophy of the tongue with fasciculation, partial deviation on the left, and inability to completely deviate the tongue towards the contralateral side of her mouth indicated palsy of the hypoglossal nerve (Fig. 4). In consideration of the clinical and radiographic findings, the diagnosis of Eagle’s Syndrome (ES) was made.

Fig. 4.

Intraoral view of the patient with marked left sided hemiatrophy and partial deviation of the tongue on the ipsilateral side of the ossified stylohyoid ligament. Note that deviation of the tongue toward the contralateral side of patient’s mouth was not possible

Discussion

ES refers to a symptomatic anomaly due to elongation of the styloid process or mineralization of the styloid complex [1]. The variability in length and direction of the styloid process and styloid chain lead to a wide range of relationships between the chain and neural and vascular elements of the neck such as cranial nerves V, VII, IX, X, internal carotid artery, and jugular vein [2, 3]. Neuropathic and vascular occlusive symptoms present diversely according to the length and width of the styloid process, angle and direction of the curve, and degree of calcification of the stylohyoid ligament. These symptoms include neck or pharyngeal pain, dysphagia, foreign body sensation in the throat, otalgia, tinnitus, and ocular pain.

Although the normal length of the styloid process can range from 1.52 to 5 cm, it is commonly considered as elongated when the length exceeds 3 cm [4–6]. The spatial position of the tip of the process is considered to have utmost pathogenic importance [6, 7]. The etiology remains unclear but theories mainly focus on congenital elongation due to persistence of cartilaginous precursors, post-traumatic scarring and hyperplasia related to previous tonsillectomy [7, 8]. Eagle [7] initially described the “Classic Styloid Syndrome” as a result of tonsillectomy with symptoms like dysphagia, foreign body sensation and vocal changes in rare cases, whereas the carotid artery type of the syndrome, so called “Stylocarotid Syndrome” is caused by pressure of the styloid chain on the external or internal branches of the carotid artery and subsequently presents with different symptoms such as transient ischemic attacks, migraines and other neurologic symptoms [3, 8]. Eagle [7] originally estimated a 4 % incidence of elongated styloid process in the general population, however this remains to be debated, as there is inconsistency in the definition of “elongation” in the literature. ES is more commonly observed in females in the 3rd–5th decades of life [9].

Careful evaluation of the history of present illness and review of systems should be combined with palpation of the anterior pillar region when ES is suspected. Palpation of the styloid process, when elongated, is both possible and a trigger for this particular neuralgia [2]. Care should be given, however, not to cause an iatrogenic fracture of the process that will neither alleviate the symptoms nor help a future resection [5]. Infiltration of local anesthetics in the tonsillar fossa has been reported to aid in diagnosis [10]. The differential diagnosis of ES includes temporomandibular joint disease, migraine headaches, trigeminal, glossopharyngeal and sphenopalatine neuralgias and chronic laryngopharyngeal reflux [1, 11]. The wide range of non-specific symptoms may lead physicians to an inaccurate clinical diagnosis and make the true diagnosis even more challenging [5].

Clinical examination of the patient should be followed with radiologic evaluation, which is comprised of traditional radiographs and CT scans of the neck and skull base. Moon et al. [8] state that the styloid process should be considered as elongated if it attains over one-third of the length of the mandibular ramus in a panoramic view. However, three-dimensional computed tomography is currently regarded as the optimal technique for accurate preoperative diagnosis as well as precise determination of the length and angulation of the styloid process. CT scans not only provide relevant information for diagnosis but are also useful when planning removal.

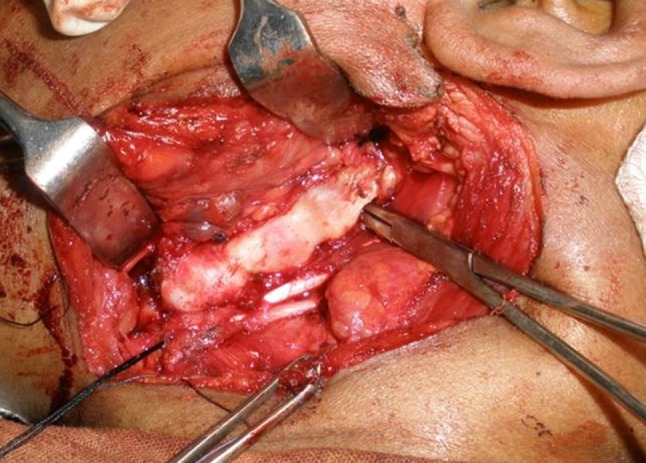

Once diagnosis is confirmed, treatment of ES can be performed with conservative, non-surgical and/or surgical methods. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, neck exercises, steroids, or local anesthetic injections have been previously described for non-surgical management. However, the long-term effectiveness of these approaches still remains controversial. Surgical resection of the elongated process or mineralized stylohyoid complex on the other hand, has generally been accepted as the primary treatment modality, particularly in patients with persistent symptoms following conservative therapy. Two approaches have been described for the surgical removal: transoral and extraoral (transcervical) [12, 13]. Transoral approach is comprised of manually locating the process with palpation of the tonsillar fossa, surgical exposure and dissection, and resection. Although standard tonsillectomy has traditionally been advocated for better exposure, Torres et al. [14] have recently described a tonsil-sparing transoral surgical approach with favorable results. Transoral approach is often warranted for aesthetic concerns and shorter operating time. Extraoral approach is the transcervical approach to the peripharyngeal space [5]. Better exposure of the styloid process and surrounding anatomical structures can be obtained through an aseptic field and provides better access to the process in patients with trismus (Fig. 5). Extraoral approach also facilitates a more complete resection of the styloid process. However, it requires more operative time and usually results in a cervical scar in young patients when the incision cannot be placed in a neck rhytid.

Fig. 5.

Intraoperative view following the exposure of the ossified stylohyoid complex

If not diagnosed timely and treated properly, hyper-mineralization of the stylohyoid ligament may eventually lead to complete ossification of the stylohyoid complex. Consequences in such cases may include sensory and functional disturbances, which lower the quality of life in affected individuals. Therefore, it is crucial to include ES in the differential diagnosis when evaluating patients with similar head and neck symptoms. When suspected, three-dimensional computed tomography imaging enables superior evaluation of ES. Once diagnosis is confirmed, the treatment plan should be tailored in accordance with the individual requirements of the case and performed without delay.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Baur is a paid consultant for Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Checkpoint LLC and Dr. Altay has provided consultancy for Checkpoint Surgical LLC in 2014. Other authors disclose no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations. There was no grant support for this study. The final version of the manuscript has been seen and approved by all authors.

References

- 1.More CB, Asrani MK. Eagle’s syndrome: report of three cases. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;63(4):396–399. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0232-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fusco DJ, Asteraki S, Spetzler RF. Eagle’s syndrome: embryology, anatomy, and clinical management. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2012;154(7):1119–1126. doi: 10.1007/s00701-012-1385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bensoussan Y, Letourneau-Guillon L, Ayad T. A typical presentation of Eagle syndrome with hypoglossal nerve palsy and Horner syndrome. Head Neck. 2014;36(12):E136–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Han MK, Kim do W, Yang JY. Non surgical treatment of Eagle’s syndrome: a case report. Korean J Pain. 2013;26(2):169–172. doi: 10.3344/kjp.2013.26.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendelsohn AH, Berke GS, Chhetri DK. Heterogeneity in the clinical presentation of Eagle’s syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134(3):389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keur JJ, Campbell JP, McCarthy JF, Ralph WJ. The clinical significance of the elongated styloid process. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;61(4):399–404. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(86)90426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eagle WW. Elongated styloid process; symptoms and treatment. AMA Arch Otolaryngol. 1958;67(2):172–176. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1958.00730010178007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moon CS, Lee BS, Kwon YD, Choi BJ, Lee JW, Lee HW, Yun SU, Ohe JY. Eagle’s syndrome: a case report. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;40(1):43–47. doi: 10.5125/jkaoms.2014.40.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murthy PS, Hazarika P, Mathai M, Kumar A, Kamath MP. Elongated styloid process: an overview. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;19(4):230–231. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beder E, Ozgursoy OB. Karatayli Ozgursoy S. Current diagnosis and transoral surgical treatment of Eagle’s syndrome. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(12):1742–1745. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaju PP, Suvarna V, Parikh NJ. Eagle’s syndrome: an enigma to dentists. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2007;19(3):424–429. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strauss M, Zohar Y, Laurian N. Elongated styloid process syndrome: intraoral versus external approach for styloid surgery. Laryngoscope. 1985;95(8):976–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diamond LH, Cottrell DA, Hunter MJ, Papageorge M. Eagle’s syndrome: a report of 4 patients treated using a modified extraoral approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;59(12):1420–1426. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.28276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torres AC, Guerrero JS, Silva HC. A modified transoral approach for carotid artery type Eagle syndrome: technique and outcomes. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2014;123(12):831–4. [DOI] [PubMed]