Abstract

Angioleiomyoma (ALM; synonyms: angiomyoma, vascular leiomyoma) is an uncommon benign tumor of skin and subcutaneous tissue. Most arise in the extremities (90 %). Head and neck ALMs are uncommon (~10 % of all ALMs) and those arising beneath the sinonasal tract mucosa are very rare (<1 %) with 38 cases reported so far. We herein analyzed 16 cases identified from our routine and consultation files. Patients included seven females and nine males aged 25–82 years (mean 58; median 62). Symptoms were intermittent nasal obstruction, sinusitis, recurrent epistaxis, and a slow-growing mass. Fifteen lesions originated within different regions of the nasal cavity and one lesion was detected incidentally in an ethmoid sinus sample. Size range was 6–25 mm (mean 11). Histologically, all lesions were well circumscribed but non-encapsulated and most (12/16) were of the compact solid type superficially mimicking conventional leiomyoma but contained numerous compressed muscular veins. The remainder were of venous (2) and cavernous (2) type. Variable amounts of mature fat were observed in four cases (25 %). Atypia, necrosis, and mitotic activity were absent. Immunohistochemistry showed consistent expression of smooth muscle actin (12/12), h-caldesmon (9/9), muscle-specific actin (4/4), variable expression of desmin (11/14) and CD56 (4/6), and absence of HMB45 expression (0/11). The covering mucosa was ulcerated in 6 cases and showed squamous metaplasia in one case. There were no recurrences after local excision. Submucosal sinonasal ALMs are rare benign tumors similar to their reported cutaneous counterparts with frequent adipocytic differentiation. They should be distinguished from renal-type angiomyolipoma. Simple excision is curative.

Keywords: Angioleiomyoma, Sinonasal tract, Angiomyolipoma, Vascular leiomyoma, Angiomyoma, PEComa, Nasal

Introduction

Mesenchymal tumors of the sinonasal tract are rare. They encompass benign tumors (benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors, angioleiomyoma and hemangiomas), lesions of low-grade or uncertain biological potential (sinonasal hemangio/glomangiopericytoma, solitary fibrous tumor, desmoid fibromatosis, low-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and low-grade sinonasal sarcoma with neural and myogenic features) and frankly malignant aggressive neoplasms (conventional malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma and other rare sarcoma types) [1–5]. Due to the rarity of sinonasal mesenchymal neoplasms, many pathologists are not familiar with their broad phenotypic spectrum.

Angioleiomyoma (ALM; synonyms: angiomyoma, vascular leiomyoma) is an uncommon benign tumor of skin and subcutaneous tissue composed of well differentiated smooth muscle proliferations associated with variable but usually prominent vascular component [6]. The latter may consist of thick-walled collapsed vascular channels (solid type), predominant thick-walled venous vessels with well recognizable lumens within smooth muscle background (venous type), or display ectatic muscular venous channels mimicking venous hemangioma but with variable smooth muscle component in-between (cavernous type) [6]. The majority of lesions originate in the extremities (~90 %), mainly in the lower limbs while ALM of the head and neck region is uncommon (~10 %) [7, 8]. Submucosal ALMs of the sinonasal tract are exceptionally rare. To date, 38 cases have been reported, mostly as single case reports [9–41] (Table 1). In this study, we describe our experience with submucosal ALMs of sinonasal tract and discuss their clinicopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics in light of previously reported cases with special emphasis on the frequent presence of adipocytic differentiation and similarities and differences compared to their cutaneous and soft tissue counterparts.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features of previously reported sinonasal angioleiomyomas including current series (n = 54)

| No. | Author | Age/gender | Site, size cm | Symptoms, duration | Histological pattern | IHC positive markers | IHC negative markers | Associated mucosal changes | Follow up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maesaka et al. [9] | 49 F | Vestibule | Facial pain | Vascular | ND | ND | NS | NR |

| 2 | Ram [10] | 40 M | Right inferior turbinate, 2.5 cm | Nasal obstruction, few mo. | Solid (reported as fibromyoma) | ND | ND | NS | NA |

| 3 | Wolfowitz et al. [11] | 42 F | Inferior turbinate, 1 cm | Recurrent epistaxis | Vascular leiomyoma | ND | ND | Ulceration | NR (30 mo.) |

| 4 | Schwartzman et al. [12] | 57 M | Sinuses | Obstruction, headache | Vascular | ND | ND | NS | NR (36 mo.) |

| 5 | McCafferey et al. [13] | 76 F | Inferior turbinate, 0.5 cm | Epistaxis | Vascular | ND | ND | NS | NA |

| 6 | Dawlatly et al. [14] | 52 M | Right vestibule, 4 cm | Epistaxis, obstruction, 1 year | Solid with fat | ND | ND | None | NR (12 mo.) |

| 7 | Hanna et al. [15] | 64 F | Inferior turbinate, 3 cm | Epistaxis, obstruction, pain, 3 wks | Solid, no fat | ND | ND | None | NR (12 mo.) |

| 8 | Sawada [16] | 41 M | Right nasal cavity/orifice | Mass, slowly growing for years | Solid with fat | ND | ND | Erythema | NR (12 mo.) |

| 9 | Ragbeer et al. [17] | 49 F | Right nasal floor, 1.5 cm | Epistaxis, pain, suppuration | Solid with fat | Desmin, MSA, vimentin | S100 | None | NR (12 mo.) |

| 10 | Harcourt et al. [18] | 55 F | Right ethmoid sinus, 2 cm | Right epiphora, 10 years | Venous, no fat | ND | ND | ND | NR |

| 11 | Khan et al. [19] | 71 F | Left inferior turbinate, 4 cm | Obstruction, 2 years | Solid with fat | NS | NS | NS | NR (12 mo.) |

| 12 | Gatalica et al. [20] | 64 M | Right vestibule, 2 cm | Obstruction, >1 year | Solid with dominant fat | Muscle-specific actin, vimentin | HMB45, desmin | NS | NA |

| 13 | Ardekian et al. [21] | 54 F | Left nasal vestibule and septum, 2 cm | Obstruction, pain and bloody discharge | Solid, no fat | NS | NS | Inflammation | NA |

| 14 | Nall et al. [22] | 43 F | Superior turbinate | Epistaxis, obstruction, facial pain, months | Venous | αSMA | NS | No | NR (21 mo.) |

| 15 | Murono et al. [23] | 69 F | Right inferior turbinate, 2 cm | Epistaxis, 1 year | Solid with fat | Vimentin, αSMA | NS | No | NA |

| 16 | Watanabe et al. [24] | 66 M | Right nasal cavity, 2 cm | Mass, after chemotherapy for Hodgkin lymphoma | Solid with fat | αSMA, MSA, focally desmin | S100, HMB45 | No | NR (24 mo.) |

| 17 | Watanabe et al. [24] | 88 F | Vestibule, 2 cm | Mass | Solid with fat | αSMA, MSA, focally desmin | S100, HMB45 | No | NR (6 mo.) |

| 18 | Marioni et al. [25] | 70 F | Right vestibule, 1.5 cm | Obstruction and epistaxis | Solid-venous, no fat | αSMA, PR | ER | No | NR (3 mo.) |

| 19 | Tardio et al. [26] | 45 M | Right nasal cavity, 1.5 cm | Epistaxis and obstruction, 2 mo. | Solid with fat | αSMA, desmin, MSA | HMB45 | No | NR (1 mo.) |

| 20 | Wang et al. [27] | 70 M | Septum, 1.1 cm | Epistaxis | Solid, no fat | SMA | NS | NS | NR |

| 21 | Wang et al. [27] | 66 F | Inferior turbinate, 0.3 cm | Asymptomatic mass | Venous, with fat | αSMA | NS | NS | NR |

| 22 | Bel Hag Salah et al. [28] | 50 F | Right middle turbinate | Nasal obstruction + rhinorrhea, 5 mo. | Solid, no fat | αSMA, h-caldesmon | NS | NS | NA |

| 23 | Erkilic et al. [29] | 52 M | Left nasal cavity, 3.5 cm | Snoring and obstruction, 20 years | Solid with fat | αSMA | S100, HMB45 | NS | NA |

| 24 | Chen et al. [30] | 88 M | Right inferior turbinate, 1.3 cm | Discharge, hearing impairment | Solid with fat | αSMA, desmin | ER, PR, CD34, EBV ISH | Inflammation | NR (12 mo.) |

| 25 | Meher et al. [31] | 24 F | Right middle turbinate, 2 cm | Epistaxis, 2 mo. | Solid-venous, no fat | NS | NS | NS | NR |

| 26 | Campelo et al. [32] | 44 F | Left turbinate | Recurrent epistaxis (4 years), obstruction (1 year), itching | Solid, no fat | NS | NS | NS | NR (10 mo.) |

| 27 | Vafiadis et al. [33] | 68 M | Right nasal vestibule, 2 cm | Nasal obstruction, >6 years | Solid, no fat glands entrapped | NS | NS | No | NR (24 mo.) |

| 28 | Singh et al. [34] | 31 M | Right nasal cavity septum, 3.2 cm | Nasal obstruction + intermittent epistaxis, 3 years | Solid, no fat | NS | NS | Surface ulceration | NR (18 mo.) |

| 29 | Michael et al. [35] | 34 M | Left nasal cavity inferior turbinate | Nasal obstruction + intermittent epistaxis, 10 years | Venous | αSMA, desmin | NS | NS | NA |

| 30 | He et al. [36] | 58 M | Right inferior turbinate, 2 cm | Recurrent epistaxis and obstruction, 10 years | Solid with fat | PR (20–30 %) | ER, HMB45, EBV | Erosion and inflammation | NR (12 mo.) |

| 31 | Navarro et al. [37] | 62 F | Left septum, 4 cm | Epistaxis, obstruction, pain, mass, 6 years | Solid, no fat | NS | NS | NS | NA |

| 32 | Moreira et al. [38] | 54 M | Left inferior meatus | Recurrent epistaxis, 20 years | Solid with fat | NS | HMB45 | NS | NR |

| 33 | Purohit et al. [39] | 45 M | Septum | Nasal obstruction, 3 years | Solid, no fat | NS | NS | No | NA |

| 34 | Yoon et al. [40] | 64 M | Inferior turbinate, 0.8 cm | Mass | Solid | Actin+ | NS | NS | NR |

| 35 | Yoon et al. [40] | 65 M | Nasal mucosa, 1 cm | Mass | Solid | Actin+ | NS | NS | NR |

| 36 | Yoon et al. [40] | 37 M | Nasal septum, 1 cm | Epistaxis | Cavernous | Actin+ | NS | NS | NR |

| 37 | Yoon et al. [40] | 71 F | Nasal septum, 2 cm | Nasal obstruction | Cavernous | ND | NS | NS | NR |

| 38 | Tseng et al. [41] | 48 F | Right inferior turbinate, 1 cm | Recurrent mucous + bloody discharge, 3 mo. | Solid, no fat | αSMA, PR | ER, S100 | No | NR (48 mo.) |

| 39 | Current study | 73 M | Right lateral nasal wall, 1.4 cm | Intermittent nasal obstruction, 10 years. | Solid with fat (<10 %) | Desmin, αSMA, h-caldesmon | HMB45 | None | NR (52 mo.) |

| 40 | Current study | 82 M | Lower left turbinate, 0.8 cm | Recurrent epistaxis for years | Solid with fat (<10 %) | αSMA, h-caldesmon | HMB45, desmin | Erosion with inflammation | NR (43 mo.) |

| 41 | Current study | 53 M | Left nasal orifice, 0.8 cm | Mass | Venous, no fat | αSMA, h-CD, desmin ± , CD56± | AR, HMB45, D2-40 | Erosion with inflammation | NR (34 mo.) |

| 42 | Current study | 76 F | Right nasal orifice, 0.6 cm | Mass | Solid with fat (40 %) | Desmin, αSMA, h-caldesmon | HMB45, ER, PR, CD56 | None | NR (32 mo) |

| 43 | Current study | 63 M | Right septum, 0.7 cm | Tumor, pyogenic granuloma? | Cavernous with fat (<2 %) | Desmin, αSMA, h-caldesmon | HMB45, CD56, D2-40 | None | NR (31 mo.) |

| 44 | Current study | 25 F | Ethmoidal cells, 0.2 cm | Incidental, recurrent sinusitis | Venous, No fat | Desmin, αSMA, h-caldesmon | HMB45 | None | NR (15 mo.) |

| 45 | Current study | 77 F | Nasal cavity, 0.7 cm | Mass | Solid with fat (<10 %) | αSMA, h-caldesmon, CD56 | Desmin, HMB45 | Erosion with inflammation | NR (211 mo.) |

| 46 | Current study | 62 F | Nasal cavity, 1.5 cm | Mass | Solid, no fat | αSMA, desmin F + , h-caldesmon, CD56 | HMB45 | Ulcerated with inflammation | NR (80 mo.) |

| 47 | Current study | 48 F | Concha, 1.2 cm | Mass | Solid, no fat | αSMA, desmin, h-caldesmon, CD56 | HMB45 | Ulcerated with inflammation | NR (161 mo.) |

| 48 | Current study | 26 M | Right inferior nasal cavity floor, 2.5 cm | Painful mass, increasing in size, 3 mo | Solid, no fat | αSMA, MSA, desmin | S100 protein, pan-cytokeratin, HMB45 | None | NR (108 mo.) |

| 49 | Current study | 55 M | Right septum, 1.0 cm | Multiple polyps, nasal congestion, sneezing, difficulty breathing, pan-sinusitis and anterior septum mass, 1.5 mo. | Solid, no fat | MSA | S100 protein | None | NR (53 mo.) |

| 50 | Current study | 77 F | Right anterior turbinate, 0.9 cm | Epistaxis with friable mass, 9 mo. | Solid, no fat | Desmin | HMB45 | None | NR (46 mo.) |

| 51 | Current study | 51 F | Left nasal polyp, 1.7 cm | Ear pain, cough, foreign-body sensation, nasal obstruction and epistaxis, 8 mo. | Cavernous, no fat | αSMA, desmin | S100 protein, CD34, pan-cytokeratin | Surface ulceration (excoriation) | NR (26 mo.) |

| 52 | Current study | 36 M | Right lateral nasal wall (turbinate), 1.7 cm | Mass at the nasal vestibule, showing recent growth, 8 mo. | Solid, no fat | αSMA, SMMHC | Desmin, S100 protein | None | NR (20 mo.) |

| 53 | Current study | 65 M | Right anterior nasal septum, 1.0 cm | Nasal congestion, with a past history of rhinoplasty and difficulty breathing and epistaxis, 20 mo. | Solid, no fat | MSA | none | Squamous metaplasia | NR (18 mo.) |

| 54 | Current study | 66 M | Right inferior turbinate, 1.2 cm | Right nasal obstruction with epistaxis, 24 mo. | Solid, no fat | MSA, desmin | S100 protein, EBER | Squamous metaplasia | NR (9 mo.) |

F female, M male, MO month, MSA muscle-specific actin, NA not available, NR no recurrence, PR progesterone receptor, SMA smooth muscle actin, SMMHC smooth muscle myosin heavy chain

Materials and Methods

We reviewed our routine and consultation files for lesions coded as angioleiomyoma, angiomyoma, angiomyolipoma and vascular leiomyoma originating in the nose, nasal cavity, or paranasal sinuses. Diagnosis was based on criteria defined for similar lesions in the most recent World Health organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the head and neck and tumors of soft tissue and bone [1, 6]. After review, only tumors arising from the mucosa-lined sinonasal sites (excluding cutaneous lesions) were included in this series. The tumor specimens were fixed in buffered formalin and embedded routinely for light microscopic examination. Immunohistochemical studies were performed on 3–4-µm sections cut from paraffin blocks using a fully automated system (“Benchmark XT System”, Ventana Medical Systems Inc, Tucson, Arizona, USA) using the following antibodies: α-smooth muscle actin (clone 1A4, 1:200, Dako), h-caldesmon (clone h-CD, 1:100, Dako), desmin (clone D33, 1:250, Dako), CD34 (clone QBEnd10, 1:200, Immunotech), CD56 (clone MRQ-42, 1:100, CELL MARQUE), HMB45 (clone HMB45, 1:50, Loxo), and podoplanin (clone D2-40, 1:50, Zytomed).

Results

Clinical Features

Sixteen cases were retrieved from our files (Table 1, Cases 39–54). Patients included seven females and nine males aged 25–82 years (mean 58; median 62). Variable combinations of intermittent nasal obstruction, chronic sinusitis-like symptoms and recurrent epistaxis were the presenting symptoms in eight patients with detailed data, respectively. A painful mass was stated in one case. Other cases either lacked detailed history or a slowly growing mass or nodule was the presenting symptom of the disease. The site was stated within different compartments of the nasal cavity (five in turbinates, four in the nasal cavity unspecified, three from the nasal septum, two in the nasal orifices, and one in the lateral nasal wall). One case (the only sinus-based lesion) was found incidentally in a polyposis specimen from the ethmoid sinus. None of the lesions was multifocal or involved more than one subregion of the sinonasal tract. There was no evidence of associated diseases or similar tumors elsewhere in the body. All lesions were removed via simple complete local excision with free albeit close margins.

At last follow-up (range 9–211 months; mean 58 months), no recurrences were recorded.

Pathological Findings

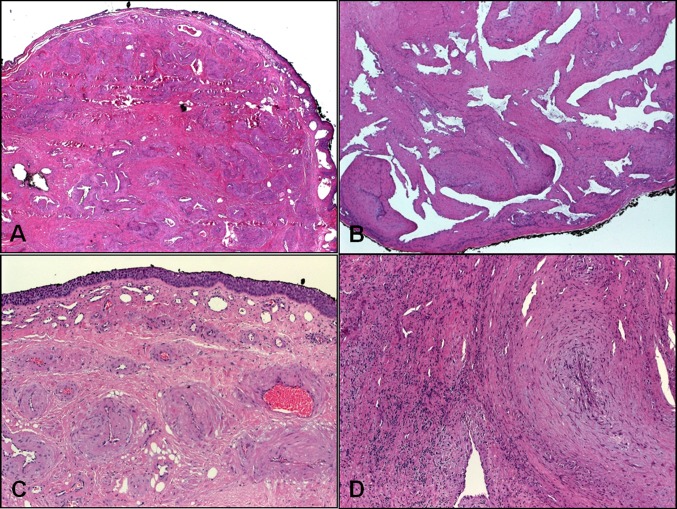

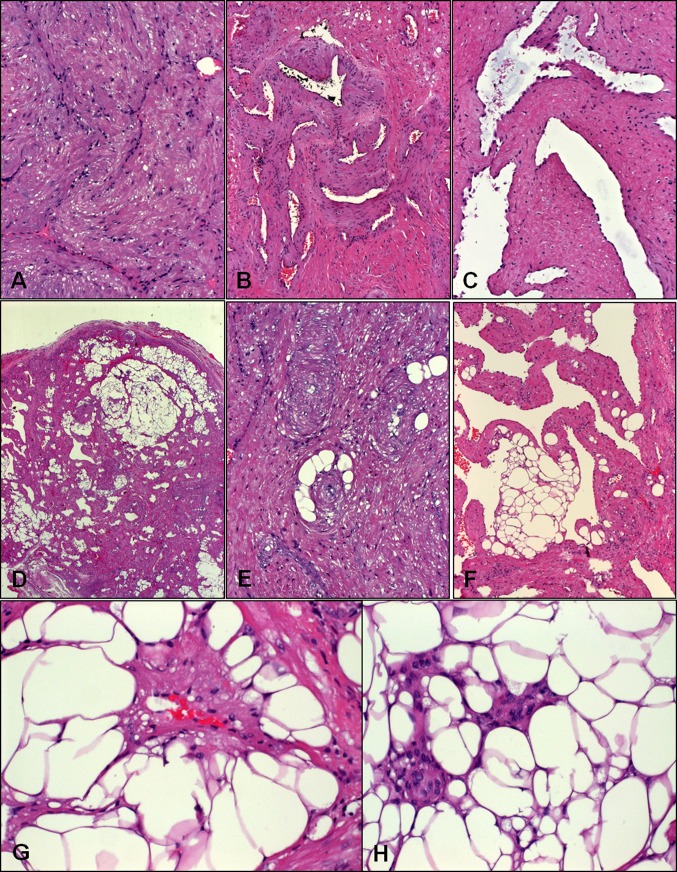

Tumor size ranged from 6 to 25 mm (mean 11) in cases with gross description or as measured from glass slides. Grossly, the lesions were described as tan-whitish with solid whorled cut-surface and firm consistency. Histologically, all lesions were non-encapsulated but well circumscribed (Fig. 1a, b). The tumors were covered by sinonasal mucosa with variable reactive or metaplastic changes (Fig. 1c). Six tumors showed mucosal ulceration/erosion with variable inflammation between the tumor and mucosal surface associated with variable degree of fibromyxoid vascular obliteration (Fig. 1d). The tumors were composed of well differentiated smooth muscle cells having elongated vesicular blunt-ended nuclei with inconspicuous nucleoli and brightly eosinophilic fibrillary cytoplasm without atypia. The cells were arranged in intersecting bundles and whorls encasing or surrounding numerous vascular channels. The smooth musculature of the vessel walls seemed to merge gradually and imperceptibly with the surrounding smooth muscle bundles. There was no cellular pleomorphism and mitotic figures were absent. Twelve of 16 cases showed compact arrangement of the smooth muscle occasionally mimicking leiomyoma but careful assessment revealed the characteristic thick-walled collapsed vascular channels (solid type) (Fig. 2a). Two lesions showed convolutes of thick-walled venous channels closely mimicking venous hemangioma (venous type) (Fig. 2b). Another two cases showed prominent dilated venous vessels within the smooth muscle proliferation corresponding to the cavernous type (Fig. 2c). A variable but generally prominent adipocytic component was appreciated in four cases (25 %). Mature macrovesicular adipocytes were scattered either singly or forming small aggregates and lobules within the lesions. The fatty component ranged from a few cells to 20 % of the lesion (Fig. 3d–h). There were no cytoplasmic vacuoles within the smooth muscle cells or other features suggestive of gradual transition from myogenic to fatty cells. The Elastica stain confirmed the venous nature of the vessels (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 1.

Low-power findings in sinonasal angioleiomyomas. a Compact submucosal growth of haphazardly arranged thick-walled venous vessel with intervening fibromuscular stroma. b This example showed ectatic (cavernous) venous channels with their muscular walls blending with background musculature. c Surface epithelium showed squamoid metaplasia. d Interstitial inflammation with fibromyxoid vascular obliteration in ulcerated lesions may mask the underlying tumor

Fig. 2.

Histological spectrum of sinonasal angioleiomyomas. a Solid type with collapsed vascular channels amid smooth muscle bundles. b Lobule-like convolutes of veins surrounded by smooth muscle stroma. c This lesion showed ectatic vascular channels enclosed within smooth muscle bundles without discernible vascular walls. d Overview of a fat-rich lesion. e This solid lesion contained scattered adipocytes forming ring-like aggregates surrounding vessels. f Cavernous lesion with fatty lobules within vascular walls. g Perivascular “ring-adipocytes” from another case. h This fat-rich lesion showed size variation of adipocytes and can be mistaken for angiomyolipoma or adipocytic neoplasm

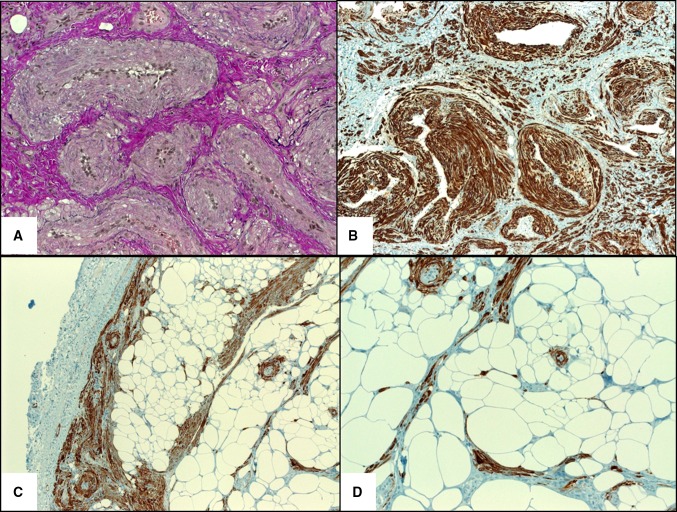

Fig. 3.

a Elastic van Gieson stain highlighting the venous channels. b Strong desmin expression highlighting intervascular smooth muscle bundles. c H-caldesmon showed strong reactivity in muscle cells (note peripheral circumscription). d Higher magnification of h-caldesmon showed scattered isolated smooth muscle cells amid the fatty component

By immunohistochemistry, all cases tested showed strong expression of alpha smooth muscle actin (12/12), h-caldesmon (9/9), muscle-specific actin (4/4) and variable expression of desmin (11/14; diffuse in nine cases, focal in two and negative in three cases). Six cases were tested for CD56: three showed a diffuse reaction, one was focally positive, and two were negative. No correlation between CD56, desmin, and histological pattern was observed for the cases stained for both markers. Two cases stained with D2-40 showed no lymphatic component. The proliferation fraction (Ki-67) was <2 %. None of the 11 cases tested were reactive for HMB45. Selected immunohistochemistry findings are illustrated in Fig. 3b–d.

Discussion

Head and neck angioleiomyoma (ALM) are rare, comprising 8.5 and 13 % of all ALMs in two larger series [7, 8]. ALMs originating from sinonasal mucosa-covered sites are even rarer. They represented 9.5–12.5 % of head and neck and 1 % of all ALMs, respectively [7, 8, 27]. Only a single case of ALM was identified among 331 consecutive benign sinonasal masses (0.3 %) [42]. Since the first description by Maesaka et al. [9], no more than 38 well documented cases have been reported in the English literature, mainly as single case reports [9–41]. Although a female predilection has been suggested [1], review of previously reported cases combined with this clinical series (total: 54; Table 1) showed that both genders are affected equally (28 males and 26 females). Age range of reported cases was 24–88 years (mean 57 years). Mean age is 56 and 55 years for women and men, respectively. The turbinates are affected most frequently, followed by other subregions of the nasal cavity including nasal orifices, septum and lateral nasal wall. The paranasal sinuses were affected in only three cases. Most sinonasal ALMs present as sessile or polypoid well circumscribed but non-encapsulated masses. Their size ranged from 0.2 to 4 cm (mean 1.7 cm). Seven of 45 cases (15 %) with detailed information measured >2 cm. Pain, a characteristic symptom of cutaneous vascular leiomyoma [1, 6, 7] was reported in 5/54 patients with sinonasal tract ALM. Another three patients reported facial pain/headache, among other symptoms.

An infrequent finding in ALMs in general is the observation of a variable clustered or intermingled component of mature adipocytes, which resulted in the use of the alternative term angiomyolipoma for some of previously reported cases [14, 24, 26, 29]. Among ALMs from all sites, a fatty component was observed in 2.8 % of cases [7]. However, review of reported cases and this clinical series (Table 1) showed a higher frequency of fatty component in sinonasal submucosal ALMs compared to their cutaneous counterparts (35 vs. 2.8 %, respectively). Comparing the subcohorts with (n = 19) and without (n = 35) adipocytic differentiation, ALM with fat tends to affect males more frequently than those without fat (63 vs. 46 % males) and to occur at a higher age (65 vs. 52 years for those with and without fat, respectively). Mean size was similar in both subgroups (18 and 16 mm, respectively).

Given that the presence or absence of a fatty component was not mentioned in several of the previously reported cases, it is possible that the frequency of adipocytic differentiation is even higher. None of the cases with available immunohistochemical findings stained for the melanocytic marker HMB45. The histological features were uniformly those of cutaneous-type ALM with or without adipocytic differentiation [43]. Based on these reported cases, sinonasal ALMs with adipocytic differentiation are histologically identical to their cutaneous/soft tissue counterparts and are distinctly different from renal-type angiomyolipoma. The latter can be associated with tuberous sclerosis complex, shows characteristic granular myogenic cells with frequent perivascular aggregates of epithelioid cells, convoluted thick-walled dysplastic vessels and cells with intermediate or transitional features between mature fatty cells and myogenic cells with cytoplasmic vacuoles indicating continuous differentiation. By immunohistochemistry, angiomyolipoma of renal type characteristically co-expresses myogenic and melanocytic markers (mainly HMB45). On the other hand, sinonasal ALM shows a mature smooth muscle phenotype (desmin+/α-SMA+/h-caldesmon+/HMB45−). On critical review of the literature, it is evident that many of the reported sinonasal angiomyolipomas were actually “ALM with adipocytic differentiation” [14, 24, 26, 29], but a few cases of genuine renal-type angiomyolipomas and PEComas have been documented in the sinonasal tract as well [44, 45]. Accordingly, ambiguous and misleading terms such as angiomyolipoma and angiolipoleiomyoma should be abandoned. Instead, the term “angioleiomyoma with adipocytic differentiation” should be used for sinonasal ALMs with fatty component, analogous to their cutaneous and soft tissue counterparts [46]. Some ALMs may show focal perivascular concentric myoid cells closely mimicking myopericytoma [43]. On the other hand, the presence of ALM-like myopericytoma is well appreciated [47]. While most myopericytomas are composed of alpha smooth muscle actin+, h-caldesmon+, desmin-negative perivascular myoid cells, 15–20 % of ALMs are desmin-negative as observed in previous studies [43] and in our current series. These observations suggest the presence of lesions with overlapping features of ALM and myopericytoma, at least in a subset of cases [43, 47]. In our current series, none of the cases showed myopericytoma-like features. Albeit rare, Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)-associated smooth muscle tumors may on occasion closely mimic ALM. These rare lesions are characteristically multifocal involving different organs and affect patients with acquired or congenital immunodeficiency. Definitionally, they harbor EBV, detectable by in situ hybridization methods for EBER [48].

Review of the previous cases showed that some lesions likely represented other entities (excluded in the current review). In particular, sinonasal glomangiopericytoma/hemangiopericytoma was more commonly confused with ALM, given that both lesions strongly express smooth muscle actin. Sinonasal glomangiopericytoma, however, is a cellular neoplasm composed of monomorphic short spindled or ovoid to glomoid cells with distinctive cytoplasm and characteristic pericytomatous vascular pattern. They usually show a characteristic peritheliomatous hyalinization, lacking in ALM. Further, they lack the cytoplasmic eosinophilia and elongated blunt-ended nuclei of mature smooth muscle cells of ALMs and they are negative for h-caldesmon and desmin [3]. Two recent studies showed uniform nuclear expression of β-catenin in sinonasal glomangiopericytoma as a consequence of β-catenin mutations [49, 50].

In summary, we reported 16 new cases and reviewed 38 previously reported cases of submucosal sinonasal angioleiomyomas emphasizing their benign nature, frequent fatty component, similarity to cutaneous angioleiomyoma and distinctness from renal-type angiomyolipoma and equal gender distribution. Awareness of their histological spectrum is necessary to distinguish them from other potentially recurring or locally aggressive neoplasms.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Fanburg-Smith JC, Thompson LDR. Benign soft tissue tumours. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. World Health Organization classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics of head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azani AB, Bishop JA, Thompson LD. Sinonasal tract neurofibroma: a clinicopathologic series of 12 cases with a review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2014 Dec 13 (Epub ahead of print). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Thompson LD, Miettinen M, Wenig BM. Sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic analysis of 104 cases showing perivascular myoid differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:737–749. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis JT, Oliveira AM, Nascimento AG, Schembri-Wismayer D, Moore EA, Olsen KD, Garcia JG, Lonzo ML, Lewis JE. Low-grade sinonasal sarcoma with neural and myogenic features: a clinicopathologic analysis of 28 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:517–525. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182426886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wenig BM. Recently described sinonasal tract lesions/neoplasms: considerations for the new world health organization book. Head Neck Pathol. 2014;8:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0533-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hisaoka M, Quade B. Angioleiomyoma. In: Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F, editors. World Health Organisation classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. pp. 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hachisuga T, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Angioleiomyoma. A clinicopathologic reappraisal of 562 cases. Cancer. 1984;54:126–130. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840701)54:1<126::AID-CNCR2820540125>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y, Li B, Li L, Liu Y, Wang C, Zha L. Angioleiomyomas in the head and neck: a retrospective clinical and immunohistochemical analysis. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:241–247. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maesaka A, Keyaki Y, Nakhashi T, Matsubara F. Nasal angioleiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma. Report of two cases. Otologia. 1966;12:42–47. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ram M. Fibromyoma of posterior end of inferior turbinal. J Laryngol Otol. 1971;85:719–721. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100073990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolfowitz BL, Schmaman A. Smooth-muscle tumours of the upper respiratory tract. S Afr Med J. 1973;47:1189–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwartzman J, Schwartzman J. Leiomyoangioma of paranasal sinuses: case report. Laryngoscope. 1973;83:1856–1858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCaffrey TV, McDonald TJ, Unni KK. Leiomyoma of the nasal cavity. Report of a case. J Laryngol Otol. 1978;92:817–819. doi: 10.1017/S002221510008614X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawlatly EE, Anim JT, El-Hassan AY. Angiomyolipoma of the nasal cavity. J Laryngol Otol. 1988;102:1156–1158. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100107583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanna GS, Akosa AB, Ali MH. Vascular leiomyoma of the inferior turbinate—report of a case and review of the literature. J Laryngol Otol. 1988;102:1159–1160. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100107595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawada Y. Angioleiomyoma of the nasal cavity. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:1100–1101. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90296-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ragbeer MS, Stone J. Vascular leiomyoma of the nasal cavity: report of a case and review of literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990;48:1113–1117. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(90)90300-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harcourt JP, Gallimore AP. Leiomyoma of the paranasal sinuses. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:740–741. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100124302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan MH, Jones AS, Haqqani MT. Angioleiomyoma of the nasal cavity—report of a case and review of the literature. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:244–246. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100126416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gatalica Z, Lowry LD, Petersen RO. Angiomyolipoma of the nasal cavity: case report and review of the literature. Head Neck. 1994;16:278–281. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880160312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ardekian L, Samet N, Talmi YP, Roth Y, Bendet E, Kronenberg J. Vascular leiomyoma of the nasal septum. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:798–800. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(96)70104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nall AV, Stringer SP, Baughman RA. Vascular leiomyoma of the superior turbinate: first reported case. Head Neck. 1997;19:63–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199701)19:1<63::AID-HED12>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murono S, Ohmura T, Sugimori S, Furukawa M. Vascular leiomyoma with abundant adipose cells of the nasal cavity. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:50–53. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(98)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe K, Suzuki T. Mucocutaneous angiomyolipoma. A report of 2 cases arising in the nasal cavity. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1999;123:789–792. doi: 10.5858/1999-123-0789-MA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marioni G, Marchese-Ragona R, Fernandez S, Bruzon J, Marino F, Staffieri A. Progesterone receptor expression in angioleiomyoma of the nasal cavity. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:408–412. doi: 10.1080/00016480260000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tardío JC, Martín-Fragueiro LM. Angiomyolipoma of the nasal cavity. Histopathology. 2002;41:174–175. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01424_4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang CP, Chang YL, Sheen TS. Vascular leiomyoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:661–665. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200404000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bel Haj Salah M, Mekni A, Nouira K, Kharrat S, Bellil K, Bellil S, Haouet S, Chelly I, Kchir N, Zitouna MM. Leiomyoma of the nasal cavity. A case report. Pathologica. 2005;97:376–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erkiliç S, Koçer NE, Mumbuç S, Kanlikama M. Nasal angiomyolipoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:446–448. doi: 10.1080/00016480510029419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen CJ, Lai MT, Chen CY, Fang CL. Vascular leiomyoma of the nasal cavity: case report. Chin Med J. 2007;120:350–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meher R, Varshney S. Leiomyoma of the nose. Singap Med J. 2007;48:e275–e276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campelo VE, Neves MC, Nakanishi M, Voegels RL. Nasal cavity vascular leiomyoma: case report and literature review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;74:147–150. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)30766-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vafiadis M, Kantas I, Panopoulou M, Sivridis E, Exarchakos G. Vascular leiomyoma of the nasal vestibule. Case report and literature review. B-ENT. 2008;4:105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh R, Hazarika P, Balakrishnan R, Gangwar N, Pujary P. Leiomyoma of the nasal septum. Indian J Cancer. 2008;45:173–175. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.44667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michael RC, Shah S. Angioleiomyoma of the nasal cavity. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:386–388. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.55002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He J, Zhao LN, Jiang ZN, Zhang SZ. Angioleiomyoma of the nasal cavity: a rare cause of epistaxis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:663–664. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Navarro Júnior CR, Fonseca AS, Mattos JR, Andrade NA. Angioleiomyoma of the nasal septum. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76:675. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942010000500027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreira MD, Lessa MM, Lima CM, Lessa HA, FonsecaJúnior LE. Angiomyolipoma of the nasal cavity. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2011;77:269. doi: 10.1590/S1808-86942011000200021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purohit GN, Agarwal N, Agarwal R. Leiomyoma arising from septum of nose. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;63(Suppl 1):64–67. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0200-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoon TM, Yang HC, Choi YD, et al. Vascular leiomyoma in the head and neck region. 11-years experience in one institution. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;6:171–175. doi: 10.3342/ceo.2013.6.3.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tseng PY, Lai YS, Chen MK, Shen KH. Progesterone receptor expression in sinonasal leiomyoma: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:1224–1228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nepal A, Chettri ST, Joshi JJ, Karki S. Benign sinonasal masses: a clinicopathological and radiological profile. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2013;11:4–8. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v11i1.11015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsuyama A, Hisaoka M, Hashimoto H. Angioleiomyoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical reappraisal with special reference to the correlation with myopericytoma. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:645–651. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Banerjee SS, Eyden B, Trenholm PW, Sheikh MY, Wakamatsu K, Ancans J, Rosai J. Monotypic angiomyolipoma of the nasal cavity: a heretofore undescribed occurrence. Int J Surg Pathol. 2001;9:309–315. doi: 10.1177/106689690100900410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuroda N, Goda M, Kazakov DV, Hes O, Michal M, Lee GH. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the nasal cavity with TFE3 expression. Pathol Int. 2009;59:769–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beer TW. Cutaneous angiomyolipomas are HMB45 negative, not associated with tuberous sclerosis, and should be considered as angioleiomyomas with fat. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:418–421. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000178007.42139.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mentzel T. Dei Tos AP, Sapi Z, Kutzner H. Myopericytoma of skin and soft tissues: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 54 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:104–113. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000178091.54147.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petersson F, Huang J. Epstein-Barr virus–associated smooth muscle tumor mimicking cutaneous angioleiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:407–409. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181ed5fd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lasota J, Felisiak-Golabek A, Aly FZ, Wang ZF, Thompson LD, Miettinen M. Nuclear expression and gain-of-function β-catenin mutation in glomangiopericytoma (sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma): insight into pathogenesis and a diagnostic marker. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:715–720. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haller F, Bieg M, Moskalev EA, Barthelmeß S, Geddert H, Boltze C, Diessl N, Braumandl K, Brors B, Iro H, Hartmann A, Wiemann S, Agaimy A. Recurrent mutations within the amino-terminal region of β-catenin are probable key molecular driver events in sinonasal hemangiopericytoma. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:563–571. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]