Abstract

We report a fatal case of necrotizing soft tissues infection caused by an Escherichia coli strain belonging to phylogenetic group C and harbouring numerous virulence factors reported to be part of a pathogenicity island (PAI) such as PAI IIJ96 and conserved virulence plasmidic region.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, immunocompromised host, necrotizing fasciitis, virulence factors

Necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTIs) can be defined as infections of any of the layers within the soft tissue compartment (dermis, subcutaneous tissue, superficial fascia or muscle); they are rare, with about 500 to 1500 cases per year, but are associated with high rate of mortality—between 16% and 24% [1]. NSTIs are classified in three types [2]: type 1 is a polymicrobial infection, type 2 is due to Streptococcus pyogenes or Staphylococcus aureus, sometimes in association, and type 3 is due to Gram-negative bacilli such as Vibrio spp. If Escherichia coli is frequently isolated from type 1 NSTIs or Fournier gangrene, it has been rarely reported in monomicrobial NSTIs [3]. However, E. coli is a versatile pathogen and may cause diverse extraintestinal diseases. This particular capability is associated with the acquisition of virulence attributes not present in commensal strains. These virulence genes may encode adhesins, invasins, siderophores, protectins and toxins which could contribute to the fatal outcome [4].

Here we report a fatal case of NSTI caused by a E. coli strain belonging to the recently described phylogenetic group C [4] and harbouring numerous virulence factors reported to be part of a pathogenicity island (PAI) such as PAI IIJ96 [5] and conserved virulence plasmidic region [4].

A 29-year-old woman was referred to our intensive care unit for septic shock. She had a history of chronic ulcerative pancolitis and autoimmune hepatitis complicated for 10 years by cirrhosis (Child-Pugh C). She was treated with azathioprine and corticosteroids (30 mg per day of prednisone). She consulted at the emergency department for fever and left leg pain during 4 days at home and reported diarrhoea during several days. The patient developed septic shock 10 hours after her admission. her temperature was 39.4°C. Her heart rate was 120 beats per minute; blood pressure was 70/50 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation was 50% with signs of acute respiratory distress. The Glasgow Coma Score was 8 without stiff neck. Clinical examination revealed the presence of a 10 cm long purpuric erythema of the posterior face of the left thigh. Mechanical ventilation was required, associated with large-volume expansion and cathecholaminergic support by adrenaline. Cardiac arrest occurred a few minutes after intubation; the low-flow time was 5 minutes. Biological examinations revealed showed acute renal failure (creatinemia 204 μmol/L), increased creatinine kinase level (930 IU/L), disseminated intravascular coagulation (platelets 40 × 109/L; D-dimer >10 000 ng/L; prothrombin time 17%), leucopenia (3800 cells/mm3), hepatocellular failure (factor V 30%, bilirubin 99 μ/L), lactate level 16 mmol/L and C-reactive protein 13.4 mg/L.

A broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy with piperacillin–tazobactam, vancomycin and amikacin was begun with the addition of clindamycin 2 hours later. Bullae and superficial excoriations appeared and progressed rapidly, as did erythema (Fig. 1). Leg and abdomen computed tomography was performed, which revealed subcutaneous fat infiltration in her two legs, without collection. Given the clinical, biological and radiological elements, a diagnosis of NSTI was made, and the patient underwent surgery 4 hours after her admission to the intensive care unit because of the clinical severity. An extensive debridement of cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues up to fascias was performed, which were not necrotizing, according to the surgeon.

Fig. 1.

Purpuric erythema, with bullae and superficial excoriations.

All bacteriological samples (blood cultures, bullae and surgical tissues) grew a wild-type strain of E. coli. The antibiotic therapy was changed to cefotaxime. Continuous renal replacement therapy was begun to treat anuric renal failure. Continuous bleeding of the surgical wound resulted in haemorrhagic shock requiring massive transfusions, and the disseminated intravascular coagulation got worse.

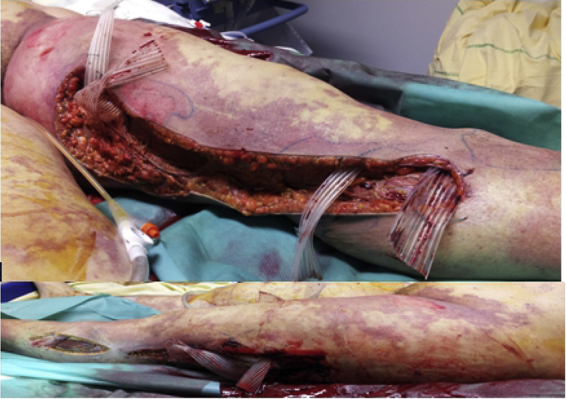

Twenty-four hours after surgery, the skin lesions were extensive, and subcutaneous crackles appeared (Fig. 2). A second surgery debridement was decided on. An extension of soft tissue cellulitis on the whole thigh and the Scarpa area, a lake of bleeding and necrotizing fascia were noted. Unfortunately, the patient died during the surgery.

Fig. 2.

Extensive debridement of cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues up to fascia was performed.

The E. coli strain was further characterized using methods described previously [3], [4]. The strain belonged to the newly described phylogenetic group C, which contains extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli strains [4]. The strain carried genes encoding the siderophores yersiniabactin (fyuA), aerobactin (iucC) and salmochelin (iroN), the toxins hemolysin (hlyC) and cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (cnf1), as well as the adhesin/invasin Hra and the P fimbriae pilin PapC. The four latter genes are known to be characteristic of PAI IIJ96, a major virulence determinant involved in highly sustained level of bacteraemia [5]. Because group C strains may contain a conserved virulence plasmidic region [4], we looked for genes specifically associated to this region (hlyF, ompTp, etsC, iss), and all were positive.

The monomicrobial E. coli NSTIs are exceptional diseases. Li et al. [6] reported only one case of E. coli monomicrobial NSTI among 35 monomicrobial fasciitis caused by Gram-negative bacteria. Eighteen case reports have been published in the literature (Table 1); most of them occurred in immunocompromised or cirrhotic patients [3], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]. Thirteen patients died (72%); all patients developed septic shock before death. Nine patients (50%) had liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh B or C), and 66% died.

Table 1.

Underlying disease and outcome of 18 cases of Escherichia coli necrotizing soft tissue infection published since 1994

| Study | Year | Age (years) | Sex | Underlying disease | Outcome | Genotypic characteristics of strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Castanet [7] | 1992 | 77 | F | Cirrhosis | D | ND |

| 72 | M | Cirrhosis | A | ND | ||

| Corredoira [11] | 1994 | 65 | F | Cirrhosis Child-Pugh C | A | ND |

| 76 | F | Cirrhosis Child-Pugh C | A | ND | ||

| Yoon [9] | 1998 | 56 | M | Cirrhosis | D | ND |

| 60 | M | Cirrhosis | A | ND | ||

| 50 | M | Chronic renal failure | D | ND | ||

| Horowitz [8] | 2004 | 53 | M | Cirrhosis Child-Pugh B, third-degree burns | D | ND |

| 55 | F | Cirrhosis Child-Pugh C | D | ND | ||

| Li [6] | 2006 | 29 | M | Nephritic syndrome | A | ND |

| Grimaldi [3] | 2010 | 83 | M | Aplastic anemia | A | cnf1 positive, phylogenetic group B2 |

| Shaked [10] | 2012 | 52 | F | Cirrhosis | D | ND |

| 61 | M | Cryoglobulinemia, immunosuppressed | D | ND | ||

| 88 | M | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, chronic renal failure | D | ND | ||

| 65 | M | B cell lymphoma, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation | D | cnf1 negative | ||

| 75 | F | B cell lymphoma, treated with chemotherapy | D | cnf1 positive | ||

| 65 | M | B cell lymphoma | D | cnf1 positive | ||

| 91 | M | Multiple myeloma | D | ND |

A, alive; D, dead; ND, not done.

Cirrhosis increases the risk of severe bacterial infections because of a failure of the immune system, including in particular a deficient bactericidal activity of IgM against some strains of Gram-negative bacteria [12], [13]. The prevalence of soft tissue infections in cirrhotic patients is between 2% and 11% [11]. The most common bacteria are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes [13], [14]. The typical skin lesion found for these E. coli infections is bullae, whereas it is present in only 15% of all NSTIs [15].

Although our patient was immunocompromised, her strains harboured numerous virulence factors. The search for 21 virulence factors was performed by PCR using previously published primers and amplification conditions [3]. As previously reported [3], [10], [16], the strain harboured genes characteristic of PAI IIJ96, in particular cnf1. cnf1 has been showed to induce in vivo dermal necrosis in rabbit [17] by trough activation of the RhoGTPases [18]. This toxin was found in the E. coli strain reported by Grimaldi et al. [3] and in 3 out 7 strains reported by Shaked and Samra [10]. The combination of this PAI and the conserved virulence plasmidic region, which have been rarely reported, may explain in part the exceptional severity of our case.

In conclusion, the patient, immunocompromised by both liver cirrhosis (Child-Pugh C) and her treatment (azathioprine, corticosteroids), experienced fatal NSTI caused by a virulent strain of E. coli carrying numerous extraintestinal virulence factors, notably cnf1. Physicians should be aware that E. coli could be responsible for NSTIs, particularly in immunocompromised patients.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Anaya D.A., Dellinger E.P. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:705–710. doi: 10.1086/511638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giuliano A., Lewis F., Hadley K., Blaisdell F.W. Bacteriology of necrotizing fasciitis. Am J Surg. 1977;134:52–57. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(77)90283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimaldi D., Bonacorsi S., Roussel H., Zuber B., Poupet H., Chiche J.D. Unusual ‘flesh-eating’ strain of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3794–3796. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00491-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemaître C., Mahjoub-Messai F., Dupont D., Caro V., Diancourt L., Bingen E. A conserved virulence plasmidic region contributes to the virulence of the multiresistant Escherichia coli meningitis strain S286 belonging to phylogenetic group C. PLoS One. 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houdouin V., Bonacorsi S., Brahimi N., Clermont O., Nassif X., Bingen E. A uropathogenicity island contributes to the pathogenicity of Escherichia coli strains that cause neonatal meningitis. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5865–5869. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5865-5869.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li D.M., Lun L.D., Chen X.R. Necrotising fasciitis with Escherichia coli. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:456. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castanet J., Lacour J.P., Perrin C., Bodokh I., Dor J.F., Ortonne J.P. Escherichia coli cellulitis: two cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:310–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horowitz Y., Sperber A.D., Almog Y. Gram-negative cellulitis complicating cirrhosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:247–250. doi: 10.4065/79.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoon T.Y., Jung S.K., Chang S.H. Cellulitis due to Escherichia coli in three immunocompromised subjects. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:885–888. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaked H., Samra Z. Unusual ‘flesh-eating’ strains of Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:4008–4011. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02316-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corredoira J.M., Ariza J., Pallares R., Carratalá J., Viladrich P.F., Rufí G. Gram-negative bacillary cellulitis in patients with hepatic cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:19–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02026118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachs M.K. Cutaneous cellulitis. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wyke R.J. Problems of bacterial infection in patients with liver disease. Gut. 1987;28:623–641. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.5.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thulstrup A.M., Sorensen H.T., Schonheyder H.C., Moller J.K., Tage-Jensen U. Population-based study of the risk and short-term prognosis for bacteriemia in patients with liver cirrhosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1357–1361. doi: 10.1086/317494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angoules A.G., Kontakis G., Drakoulakis E., Vrentzos G., Granick M.S., Giannoudis P.V. Necrotising fasciitis of upper and lower limb: a systematic review. Injury. 2007;38(Suppl. 5):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petkovsek Z., Elersic K., Gubina M., Zgur-Bertok D., Starcic Erjavec M. Virulence potential of Escherichia coli isolates from skin and soft tissue infections. J Clin Micobiol. 2009;47:1811–1817. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01421-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caprioli A., Falbo V., Roda L.G., Ruggeri F.M., Zona C. Partial purification and characterization of an Escherichia coli toxic factor that induces morphological cell alterations. Infect Immun. 1983;39:1300–1306. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1300-1306.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horiguchi Y. Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factors and Bordetella dermonecrotic toxin: the dermonecrosis-inducing toxins activating Rho small GTPases. Toxicon. 2001;39:1619–1627. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(01)00149-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]