Abstract

Endocarditis due to Legionella spp. is uncommon but presumably underestimated given the prevalence of Legionellae in the environment. We report a first and unusual case of chronic native valve endocarditis due to L. anisa and advocate that the diagnosis of endocarditis be made collaboratively between the cardiologist, surgeon, microbiologist and pathologist.

Keywords: 16S rDNA PCR, diagnosis, endocarditis, histologic analysis, Legionella

Case Report

A 58-year-old woman was hospitalized in April 2014 to undergo aortic valve replacement. Patient history was notable for asthma, type 2 diabetes mellitus and grade II obesity. In 2009 the diagnosis of an atrioventricular block led to the implantation of a single-chamber pacemaker. At that time, minimal aortic and mitral insufficiency were noticed at echocardiography, left ventricular ejection fraction was 65% and there was no heart murmur. Leucocyte count was 10 × 109 cells/L, and the C-reactive protein level was 16 mg/L. In 2012 the patient had a first episode of cardiac decompensation. Moderate aortic and minimal mitral insufficiencies were found, as well as a decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction to 34% with normal coronary arteries. Leucocyte count was 11.1 × 109 cells/L and C-reactive protein was 30 mg/L. Medical treatment for cardiac insufficiency was initiated.

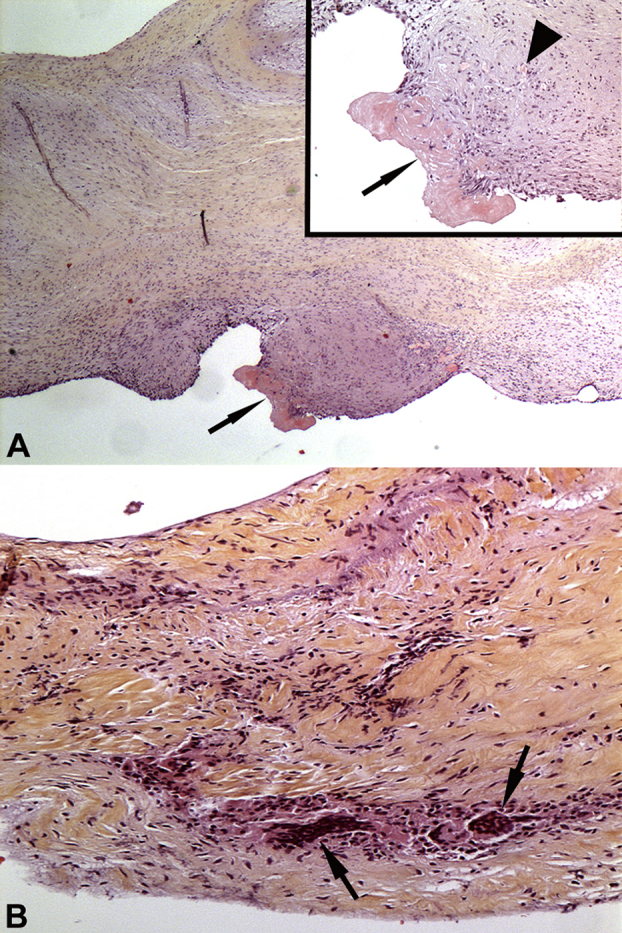

In January 2014, a new episode of cardiac decompensation including acute pulmonary edema led to cardiac resynchronization consisting in the implantation of a new pacemaker, as well as readjustment of the medical treatment. However, major aortic insufficiency triggering repetitive cardiac decompensation episodes led to aortic valve replacement by a bioprosthetic valve 4 months later. During cardiac surgery the operator noticed an abnormal appearance of the aortic valve; however, no vegetation or abscess was apparent. Gram staining of resected valve smears and tissue cultures revealed nothing abnormal. No fever was observed during hospitalization, and no antibiotic therapy was administered. On the basis of the macroscopic aspect of the valve as observed by the surgeon, broad-range 16S rDNA PCR was performed using the kit UMD-SelectNA (Molzym). The analysis was performed under the conditions recommended to avoid contamination with exogenous bacterial DNA; all reagents, including water, were free of DNA. The sequence revealed 100% identity with that of Legionella anisa, a result never obtained in the laboratory with broad-range 16S rDNA PCR (GI 645322215, ATCC 35292). Histologic examination of several sections of the resected aortic valve revealed scar fibrosis with a small vegetation and inflammation with mononuclear and giant cells, consistent with chronic infective endocarditis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Valve sections stained with haematoxylin and eosin. (A) Low-power view of aortic valve showing scar fibrosis. Minute vegetation (arrow) is present at surface. (Inset) Higher-magnification image showing the vegetation (arrow) above scarring tissue with angiogenesis and slight mononuclear cell inflammation (arrowhead). Original magnification, ×2.5; inset, ×10. (B) Valve inflammation with mononuclear and giant cells (arrows). Structure of the valve is disrupted by scar fibrosis. Original magnification, ×10.

At this stage, the patient was extensively questioned and remembered one episode of exacerbated cough a few weeks before the cardiac intervention. According to the medical record, a similar episode occurred in 2009. At a 6-week follow-up visit, the clinical condition of the patient had improved, with the C-reactive protein level persisting at 18 mg/L. Antibiotic treatment with levofloxacin (500 mg per day for 3 weeks) was initiated in consideration of the retrospective diagnosis of chronic infective endocarditis, aortic bioprosthesis implantation and a persisting, although discrete, inflammatory syndrome. At the time of writing, the patient was in good condition.

Discussion

L. anisa, widely spread in the environment in soil and water, was first isolated in 1985 from potable water collected in American hospitals. In susceptible hosts, infection typically occurs by inhalation of contaminated aerosols, as is the case with all Legionella species. In the present case, the source of contamination remains unknown. L. pneumophila is responsible for 90% of documented Legionella infections. The species responsible for the remaining 10%, including L. anisa, are difficult to detect with standard diagnostic methods. Some isolates grow poorly on buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) agar [1], and the sensitivity of serologic methods is inconstant and cross-reactivity may occur [2]. Moreover, if endocarditis is not suspected, incubation times for blood cultures are normally not extended, and BCYE agar is not used for valve tissue cultures.

Twenty-six Legionella species have been reported to be human pathogens, in addition to L. pneumophila [3], [4], but human infections due to non-pneumophila Legionella species are uncommon. Although the virulence properties of L. anisa have been questioned when compared to those of L. pneumophila [5], the former has nonetheless been associated with human disease, including pneumonia [6], pleural infection [7], osteomyelitis [8], mycotic aneurysm [9] and moderately severe Pontiac fever [10].

Extrapulmonary manifestations of Legionella infections are reported, particularly in immunosuppressed patients, and are likely to be the consequence of hematogenous dissemination from the lung, although this is not always proven. Endocarditis due to Legionella spp. is rare and occurs mainly in patients who underwent heart valve replacement, with L. pneumophila, L. micdadei and L. dumoffii being the principal species reported [11], [12]. No respiratory disease was observed in these cases. Only two reports of native valve endocarditis due to Legionella have been published [3], [13]. In the first, L. pneumophila was also isolated from bronchoalveolar fluid, while in the second, pulmonary samples were not tested for the presence of L. cardiaca but chest radiography and computed tomography findings were compatible with pneumonia. It is notable that despite the delay in diagnosis in all cases, all but one [3] evolved favorably.

This report also highlights the fact that histologic analysis of resected heart valves should be performed on several sections, especially in cases of mild chronic endocarditis; in the present case, signs typical of endocarditis were found, but not in all sections.

We consider that L. anisa should be regarded as a potential agent of infective endocarditis, particularly in cases of culture-negative endocarditis with mild symptoms. In the present case, the low virulence attributed to L. anisa may have been responsible for the particularly slow evolution of the disease. It should be kept in mind that Legionella extrapulmonary infection can occur in patients who are not severely immunocompromised.

This report emphasizes the difficulties inherent in diagnosing non-pneumophila extrapulmonary infections. It also stresses the importance of close cooperation between the clinician, surgeon, microbiologist and pathologist in diagnosing endocarditis. Histologic analysis of several sections and molecular analysis should definitely be carried out if any of the specialists involved suspects a heart valve infection.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Lee T.C., Vickers R.M., Yu V.L., Wagener M.M. Growth of 28 Legionella species on selective culture media: a comparative study. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2764–2768. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.10.2764-2768.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raoult D., Casalta J.P., Richet H. Contribution of systematic serological testing in diagnosis of infective endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5238–5242. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5238-5242.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearce M.M., Theodoropoulos N., Noskin G.A. Native valve endocarditis due to a novel strain of Legionella. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:3340–3342. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01066-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muder R.R., Victor L.Y. Infection due to Legionella species other than L. pneumophila. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:990–998. doi: 10.1086/342884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fields B.S., Barbaree J.M., Sanden G.N., Morrill W.E. Virulence of a Legionella anisa strain associated with Pontiac fever: an evaluation using protozoan, cell culture, and guinea pig models. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3139–3142. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.3139-3142.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thacker W.L., Benson R.F., Hawes L., Mayberry W.R., Brenner D.J. Characterization of a Legionella anisa strain isolated from a patient with pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:122–123. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.1.122-123.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bornstein N., Mercatello A., Marmet D., Surgot M., Deveaux Y., Fleurette J. Pleural infection caused by Legionella anisa. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2100–2101. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.9.2100-2101.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanchez M.C., Sebti R., Hassoun P. Osteomyelitis of the patella caused by Legionella anisa. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2791–2793. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03190-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanabe M., Nakajima H., Nakamura A. Mycotic aortic aneurysm associated with Legionella anisa. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2340–2343. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00142-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenstersheib M.D., Miller M., Diggins C. Outbreak of Pontiac fever due to Legionella anisa. Lancet. 1990;336:35–37. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91532-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel M.C., Levi M.H., Mahadevi P., Nana M., Merav A.D., Robbins N. L. micdadei PVE successfully treated with levofloxacin/valve replacement: case report and review of the literature. J Infect. 2005;51:e265–e268. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leggieri N., Gouriet F., Thuny F., Habib G., Raoult D., Casalta J.P. Legionella longbeachae and endocarditis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:95–97. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.110579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samuel V., Bajwa A.A., Cury J.D. First case of Legionella pneumophila native valve endocarditis. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e576–e577. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]