Abstract

Obesity, a known risk factor for pancreatic cancer, is associated with inflammation and insulin resistance. Proinflammatory prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and elevated insulin-like growth factor type 1 (IGF-1), related to insulin resistance, are shown to play critical roles in pancreatic cancer progression. We aimed to explore a potential cross talk between PGE2 signaling and the IGF-1/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway in pancreatic cancer, which may be a key to unraveling the obesity-cancer link. In PANC-1 human pancreatic cancer cells, we showed that PGE2 stimulated mTORC1 activity independently of Akt, as evaluated by downstream signaling events. Subsequently, using pharmacological and genetic approaches, we demonstrated that PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation is mediated by the EP4/cAMP/PKA pathway, as well as an EP1/Ca2+-dependent pathway. The cooperative roles of the two pathways were supported by the maximal inhibition achieved with the combined pharmacological blockade, and the coexistence of highly expressed EP1 (mediating the Ca2+ response) and EP2 or EP4 (mediating the cAMP/PKA pathway) in PANC-1 cells and in the prostate cancer line PC-3, which also robustly exhibited PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation, as identified from a screen in various cancer cell lines. Importantly, we showed a reinforcing interaction between PGE2 and IGF-1 on mTORC1 signaling, with an increase in IL-23 production as a cellular outcome. Our data reveal a previously unrecognized mechanism of PGE2-stimulated mTORC1 activation mediated by EP4/cAMP/PKA and EP1/Ca2+ signaling, which may be of great importance in elucidating the promoting effects of obesity in pancreatic cancer. Ultimately, a precise understanding of these molecular links may provide novel targets for efficacious interventions devoid of adverse effects.

Keywords: prostaglandin E2, mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1, pancreatic cancer, obesity

obesity is an established risk factor for pancreatic cancer (4), a remarkably aggressive and fatal disease with an overall 5-yr survival rate of only ∼5% (46). Although the link between obesity and cancer is compelling, the mechanisms driving this association remain poorly understood. A number of factors, such as the proinflammatory state associated with excess adiposity, as well as the elevated levels of growth hormones, i.e., insulin and insulin-like growth factor type 1 (IGF-1), are implicated (21). Compensatory high levels of insulin during obesity-associated insulin resistance are known to upregulate hepatic IGF-1 synthesis and suppress IGF-binding protein, leading to increased bioavailable IGF-1 (10). The elevated levels of insulin/IGF-1 may contribute to cancer development by activating insulin and IGF-1 receptors and the downstream phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 (mTORC1) cascade, a key signaling module in the regulation of cell growth and survival (26, 41). In accordance with this notion, type 2 diabetes, hyperinsulinemia, and increased circulating IGF-1 are established risk factors for pancreatic and other types of cancers (17, 48). Additionally, the IGF-1/Akt/mTORC1 pathway has been shown to be important in promoting proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells (45) and, recently, has been implicated in the anticancer effects of caloric restriction and the procancer effects of an obesity-inducing diet on mouse models of pancreatic cancer (28). Triggered by growth factors (e.g., IGF-1), mTORC1 is activated through the canonical PI3K/Akt module and can phosphorylate a number of substrates involved in protein synthesis and cell growth, such as ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein (4E-BP1) (26). Therefore, the insulin/IGF-mTOR axis may, at least in part, account for the link between obesity and pancreatic cancer.

In addition to systemic hormonal changes, increasing attention has focused on the local and systemic effects of inflammation. Obesity is recognized as a chronic inflammatory state, with leukocyte infiltration into adipose and other tissues accompanied by increased local and systemic proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines and prostaglandins (21, 39). Chronic inflammation has long been associated with cancer development and progression (30). Our previous study also showed that oral administration of nimesulide, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, significantly delayed the progression of Kras-driven early pancreatic neoplasia in a conditional mouse model (11). A critical player in the obesity-inflammation-cancer axis is prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a key inflammatory lipid mediator generated by cyclooxygenase enzymes (COX-1 and -2), the best-characterized targets of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (32). Overexpression of COX-2 and elevated levels of PGE2 are often observed in human cancers, including pancreatic cancer, as well as in obese individuals (9, 35, 47, 49). Secreted by tumor cells or infiltrating inflammatory cells, PGE2, through activation of its receptors and downstream signaling, may promote cell proliferation, survival, migration, invasion, angiogenesis, inflammation, and immune evasion (14, 18, 37). PGE2 exerts its biological functions through binding to one of the four subtypes of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), EP1, EP2, EP3, and EP4 (50). Previously, we showed that the growth-promoting effects of PGE2 on pancreatic cancer cells are mediated by EP2 and/or EP4 (12), both of which are coupled with G protein αs (Gαs), which is known to stimulate cAMP formation and, subsequently, activate protein kinase A (PKA) (7).

Overall, the mechanisms underlying obesity-promoted pancreatic cancer are most likely to be multifaceted and interrelated. Links between critical signaling pathways deserve more attention. In particular, a potential cross talk between the PGE2/EP/cAMP and IGF-1/Akt/mTOR pathways in pancreatic cancer has not been explored. It has been demonstrated in other cell systems that cAMP or PKA can lead to activation of mTORC1 (3, 22). Therefore, by activating EP receptors, PGE2 may stimulate mTORC1 and potentiate its growth-promoting action. We have uncovered a novel cross talk between PGE2 signaling and the mTORC1 pathway in pancreatic cancer cells. We further investigated the mechanisms through which PGE2 can stimulate mTORC1 and, potentially, augment the protumorigenic effects of insulin/IGF-1. Since PGE2 signaling and the IGF-1/Akt/mTORC1 pathway are overactivated in obesity-associated cancers, this novel cross talk may be of great importance in elucidating the tumor-promoting effects of obesity and inflammation in pancreatic and other types of cancers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and chemical reagents.

The following primary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA): phosphorylated (Thr389) p70S6K Ab (catalog no. 9205), phosphorylated (Ser235/236) S6 ribosomal protein (S6rp) Ab (catalog no. 2211), phosphorylated (Ser240/244) S6rp MAb (catalog no. 5364), S6rp MAb (catalog no. 2317), phosphorylated (Ser133) cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) MAb (catalog no. 9198), phosphorylated (Ser473) Akt Ab (catalog no. 9271), phosphorylated (Thr308) Akt Ab (catalog no. 9275), Akt Ab (catalog no. 9272), phosphorylated (Thr202/Tyr204) MAPK (Erk1/2) MAb (catalog no. 4370), phosphorylated (Ser380) p90S6K (also known as RSK) MAb (catalog no. 9335), phosphorylated (Thr37/46) 4E-BP1 (236B4) MAb (catalog no. 2855), and GAPDH MAb (catalog no. 2118). PGE2, forskolin, H-89, butaprost, the EP4 agonist CAY10580, the EP2 antagonist PF-04418948, the EP4 antagonist ONO-AE3-208, ionomycin, and BAPTA-AM were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI); rapamycin from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA); EP1 small interfering RNA (siRNA; catalog no. L-005711, ON-TARGETplus human PTGER1 siRNA-SMARTpool) from GE Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO); and recombinant human IGF-1 from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Cell culture and treatments.

The human cancer cell lines AsPC-1, BxPC-3, Capan-2, HPAF-II, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1 (pancreatic cancer), PC-3 (prostate cancer), MCF-7 (breast cancer), and DLD-1 and SW480 (colon cancer) were obtained from the American Tissue Type Culture Collection. MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1× penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and cultured at 37°C and 10% CO2. AsPC-1, BxPC-3, Capan-2, HPAF-II, PC-3, MCF-7, DLD-1, and SW480 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1× penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine (Life Technologies) and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2. For Western blot analysis, cells were seeded in six-well plates. After serum starvation for 18 h, cells were treated as indicated.

Western blotting.

After treatments, cells were harvested and lysed in lysis buffer (1× Tris buffer, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100, and 0.25% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Forty micrograms of proteins [quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific)] were loaded onto 10% Mini-PROTEAN TGX precast gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked and incubated with primary antibodies according to the manufacturer's recommendations. After incubation with secondary antibodies, proteins were detected by ECL reagents (Thermo Scientific) and exposed to CL-XPosure X-ray films (Thermo Scientific).

Intracellular cAMP measurement.

Cells were seeded in six-well plates or 35-mm dishes and then serum-starved. After treatments, cells were lysed in 0.1 M HCl (150 μl per well). The lysates were centrifuged at 1,000 g and 4°C for 10 min. cAMP levels in the cell lysates were then measured by a cAMP enzyme immunoassay kit (Cayman Chemical) following the manufacturer's instructions. cAMP levels were normalized to the protein concentrations of the samples.

Intracellular Ca2+ concentration measurement.

Cells were seeded on coverslips. After serum starvation, the coverslips were incubated with 5 μM fura 2-AM diluted in prewarmed Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) for 1 h at 37°C. Coverslips were then mounted in an experimental chamber (0.5 ml volume) placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (Axio Observer.A1). The chamber was perfused (1 ml/min) at 37°C with buffered HBSS. At selected times, the perfusion fluid was changed to HBSS containing agonists (PGE2). Ratio (340-nm excitation to 380-nm excitation) images were obtained every second by a digital camera (AxioCam MRm) attached to the microscope, which was operated with associated software (AxioVision, all components from Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Intracellular Ca2+ concentration is proportional to the ratio of excitation at 340 nm to excitation at 380 nm. In some experiments, cells were plated onto coverslips that fit inside cuvettes, which in turn were loaded into a temperature-controlled fluorometer (Hitachi). At selected times, agonist was introduced into the cuvette. Ratio values for the entire cuvette were determined as described above.

siRNA transfection.

Cells were seeded in six-well plates and incubated overnight in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% FBS. Transfection of siRNA was carried out on the following day with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent (Life Technologies) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Cells were incubated for an additional 3 days and then serum-starved and stimulated with PGE2.

Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR.

Relative transcript expression levels of EP1, EP2, EP4, and IL-23 were determined by quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) using a SYBR Green-based method. Briefly, the PureLink RNA Mini Kit (Life Technologies) was used to extract total RNA from cells. Reverse transcription was performed with the iScript reverse-transcription supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) using 1 μg of total input RNA. The synthesized cDNA samples were used as templates for the following real-time PCR analysis. All reactions were performed using the Bio-Rad iQ5 system, and the amplifications were done using the iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Gene-specific oligonucleotide primers for EP1, EP2, EP4, and IL-23A (IL-23, α-subunit p19) and internal reference ACTB (β-actin) or RNA18S5 (RNA, 18S ribosomal 5) are as follows: 5′-ACCTTCTTTGGCGGCTCTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAACACCAGCATTGGGCT-3′ (reverse) for EP1 (exons 2 and 3), 5′-GCTCCTTGCCTTTCACGATTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGATGGCAAAGACCCAAGG-3′ (reverse) for EP2 (exons 1 and 2), 5′-CGCTCGTGGTGCGAGTATT-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGGGTCTAGGATGGGGTTC-3′ (reverse) for EP4 (exons 2 and 3), 5′-CACTAGTGGGACACATGGATCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGTGGATCCTTTGCAAGCAG-3′ (reverse) for IL-23A (exons 1 and 2), 5′-GCACAGAGCCTCGCCTTT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TATCATCATCCATGGTGAGCTGG-3′ (reverse) for ACTB (exons 1 and 2), and 5′-AGTCCCTGCCCTTTGTACACA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGATCCGAGGGCCTCACTA-3′ (reverse) for RNA18S5. The relative mRNA transcript levels are calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (29) to determine the fold change in indicated genes normalized to ACTB or RNA18S5.

Cytokine array.

PANC-1 cells were seeded in six-well plates and then serum-starved. Cells were incubated in culture medium (2 ml) with or without PGE2 and IGF-1, alone or in combination. Cell culture supernatants collected after 24 h of incubation were profiled using the Human Cytokine Array Kit, Panel A (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) following the manufacturer's instructions. The membrane-based proteomic array detects relative levels of 36 different cytokines, chemokines, and acute-phase proteins, including complement 5/5a, CD40 ligand, granulocyte colony-stimulation factor, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL) 1/growth regulated oncogene-α, chemokine ligand (CCL) 1/I-309, ICAM-1, IFN-γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-16, IL-17, IL-17E, IL-23, IL-27, IL-32α, CXCL10/inducible protein 10, CXCL11/interferon-inducible T cell α chemoattractant (I-TAC), CCL2/monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), CCL3/macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, CCL4/MIP-1β, CCL5/regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), CCL12/stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1, serpin E1/plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1, TNFα, and triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM)-1. After exposure to horseradish peroxidase substrate as the final step, the array membranes were imaged using a chemiluminescence image analyzer (LAS-4000 mini, Fujifilm Life Sciences, Tokyo, Japan), and the intensity of signals normalized to the references was quantified with Multi Gauge version 3.0 software (Fujifilm Life Sciences).

Statistical analyses.

Values are means ± SD. To determine statistical significance, one-way ANOVA and two-tailed Student's t-tests were performed assuming unequal variances. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

PGE2 activates mTORC1 in human pancreatic cancer cells.

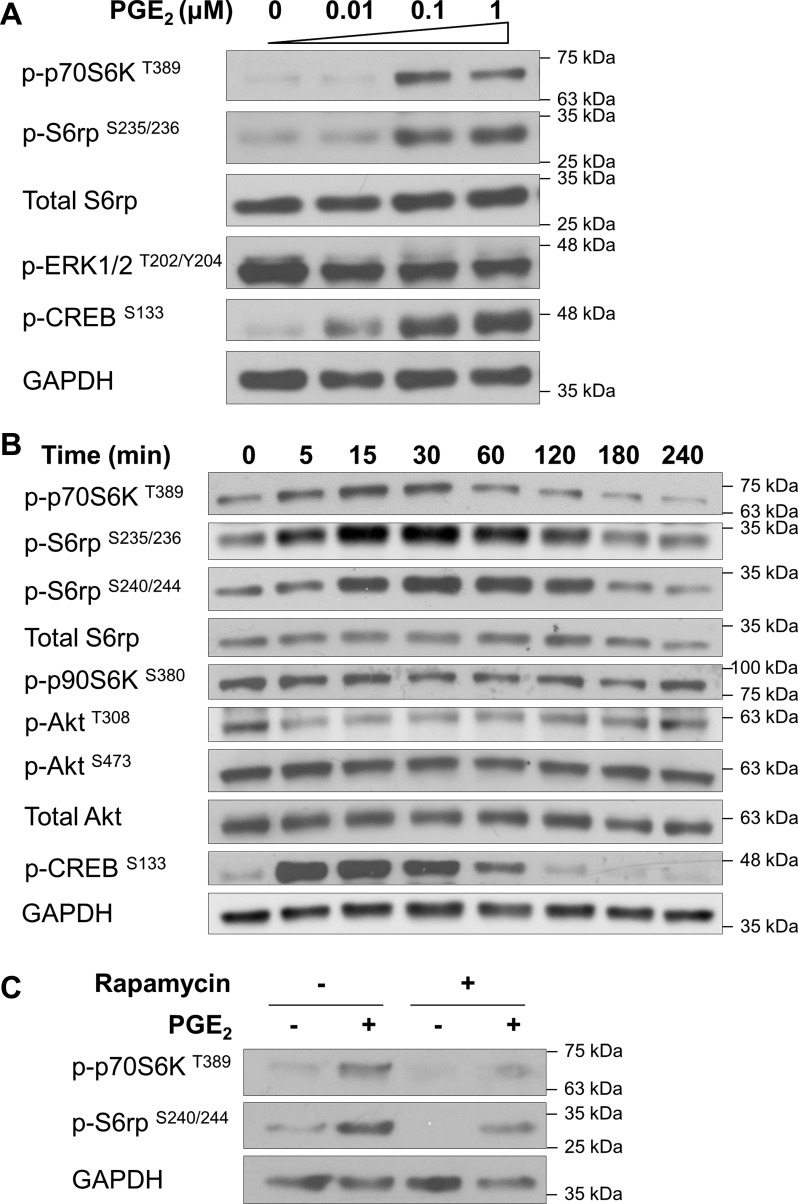

PANC-1 cells have been used extensively as a model system to study the effects of growth factors on the biological behavior of human pancreatic cancer cells. To determine whether PGE2 stimulates mTOR signaling in pancreatic cancer cells, PANC-1 cells were treated with PGE2, and then mTORC1 activation was assessed by Western blot analysis of phosphorylation levels of downstream molecules. As shown in Fig. 1, A and B, PGE2 dose- and time-dependently induced the phosphorylation of S6rp at Ser235/236, which correlated with the increased Thr389 phosphorylation of p70S6K, a major mTORC1 target upstream of S6rp. These effects were robust after 15 min of stimulation and observed at 0.1 μM PGE2.

Fig. 1.

PGE2 activates mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 (mTORC1). PANC-1 cells were incubated with 0–1 μM PGE2 for 15 min (A), incubated with PGE2 (1 μM) for 0–240 min (B), or pretreated with the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin (1 nM) for 30 min and then stimulated with or without PGE2 (1 μM) for 15 min (C). After treatments, cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting with phosphorylated ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p-p70S6K and p-p90S6K), phosphorylated S6 ribosomal protein (p-S6rp) and total S6rp, phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt) and total Akt, and phosphorylated cAMP response element-binding protein (p-CREB). GAPDH was used as a loading control.

Although Ser235/236 phosphorylation of S6rp can also be accomplished by p90S6K independently of mTORC1, p90S6K activation assessed by Ser380 phosphorylation was unchanged in response to PGE2 treatment (Fig. 1B). Also, phosphorylation of ERK, a key regulator of p90S6K, was not increased by PGE2 in these cells (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, phosphorylation of S6rp at Ser240/244, known to be a p70S6K-specific site (1, 44), was markedly induced by treatment with PGE2 (Fig. 1, B and C). Moreover, treatment of PANC-1 cells with 1 nM rapamycin, a potent allosteric inhibitor of mTORC1, suppressed PGE2-induced S6rp phosphorylation (Fig. 1C), corroborating the finding that phosphorylation of S6rp at Ser240/244 in response to PGE2 is mediated by mTORC1. Taken together, these results indicate that PGE2 stimulates mTORC1 activity in pancreatic cancer cells. Interestingly, PGE2 did not increase Akt phosphorylation (Thr308 and Ser473) (Fig. 1B), implying that the cross talk to the mTORC1 cascade is downstream of Akt and does not affect mTORC2 [as judged by phosphorylated (Ser473) Akt]. These findings prompted us to explore the mechanism(s) underlying PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation in pancreatic cancer cells.

PGE2 activates mTORC1 via the EP4/cAMP/PKA pathway.

As a first step to examine the mechanism(s) by which PGE2 induces mTORC1 activation in PANC-1 cells, we determined the effects of PGE2 on intracellular cAMP levels. A representative dose-response curve is shown in Fig. 2A. A half-maximal increase was seen at 0.09 μM, and maximal effects were obtained at ∼1 μM PGE2. Notably, PGE2 was effective at submicromolar concentrations, suggesting that the responses were mediated by specific binding to the EP receptors. We verified that treatment of these cells with PGE2 increased the phosphorylation of CREB (Fig. 1, A and B), which is known to be positively regulated by PKA, the activation of which is dependent on cAMP.

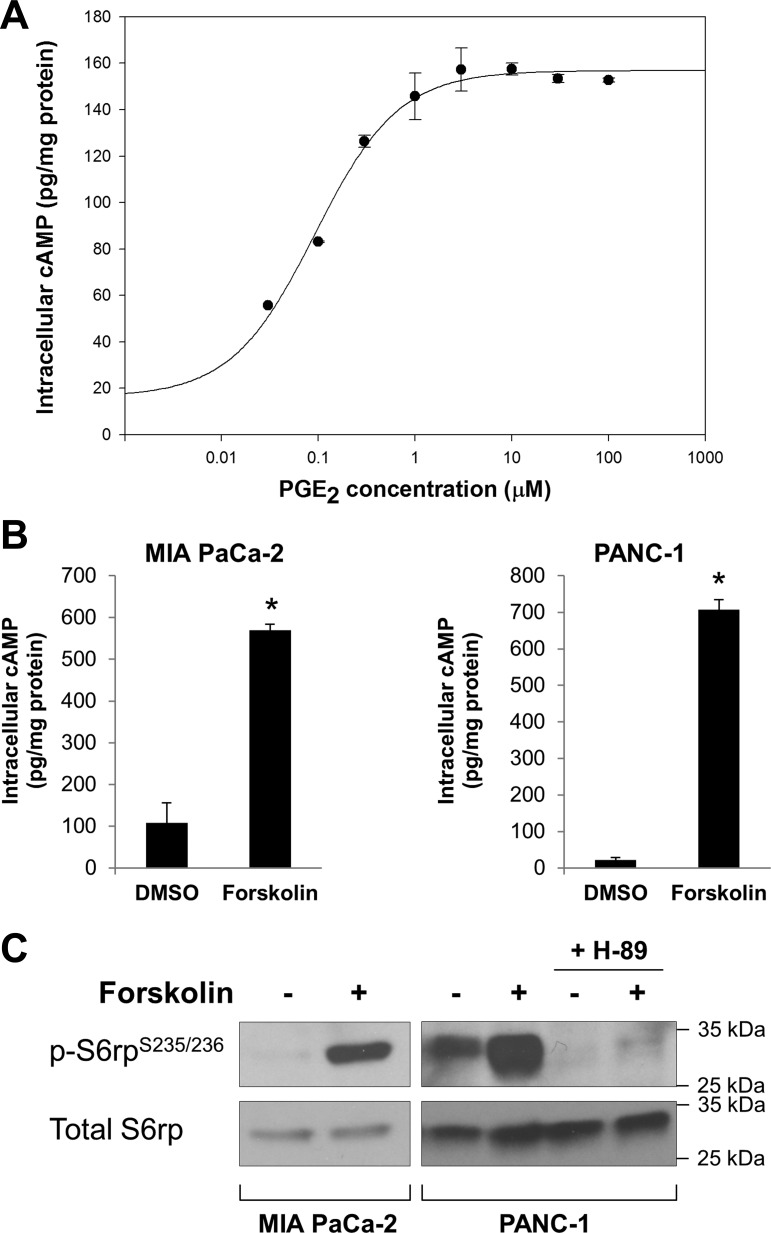

Fig. 2.

Forskolin, a cAMP stimulator, mimics the effects of PGE2. A: dose-response curve of PGE2-mediated cAMP induction. PANC-1 cells were incubated with PGE2 at increasing concentrations (0, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, 3, 10, 30, and 100 μM) for 1 min at 37°C and then lysed in 0.1 N HCl. Intracellular levels of cAMP in the cell lysates were determined by an enzyme immunoassay. All values were normalized to protein concentrations in the cell lysates. B: forskolin increases intracellular levels of cAMP in MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells. Cells were incubated with forskolin (10 μM) for 5 min, and levels of cAMP in the cell lysates were determined. *P < 0.05 (by Student's t-test). C: forskolin stimulates phosphorylation of S6rp in MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells. Cells were treated with forskolin (10 μM) for 2 h, with or without H-89 (a PKA inhibitor). After treatments, cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting with p-S6rp and total S6rp.

Next, we determined whether the elevation of the intracellular levels of cAMP is sufficient to induce mTORC1 activation. Exposure to the adenylate cyclase activator forskolin induced a marked accumulation of cAMP in MIA PaCa-2 and PANC-1 cells (Fig. 2B). Importantly, forskolin mimicked the effect of PGE2 on S6rp phosphorylation in both cell lines (Fig. 2C), supporting the idea that cAMP is involved in this cross talk. Also, the effect of forskolin was blocked in cells preincubated with H-89 (Fig. 2C), a preferential inhibitor of PKA.

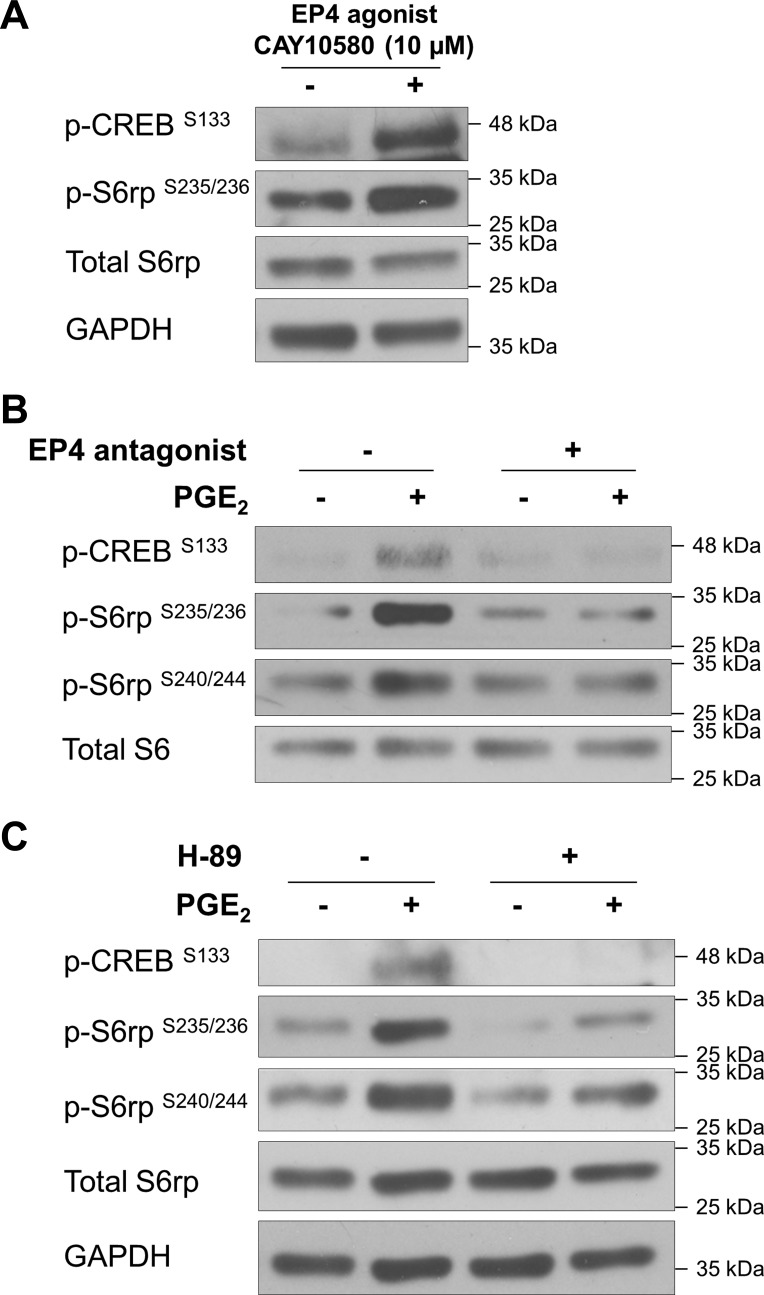

Among the four subtypes of GPCRs for PGE2, EP2 and EP4 are known to couple to Gαs and, thus, are responsible for stimulating cAMP production via activation of adenylate cyclase (50). To determine the contribution of EP2 and EP4, receptor agonists and antagonists were utilized. As shown in Fig. 3A, PGE2-induced cAMP accumulation was blocked by the EP4 antagonist ONO-AE3-208, but not by the EP2 antagonist PF-04418948, in PANC-1 cells. Besides, an EP4 agonist (CAY10580), rather than an EP2 agonist (butaprost), markedly increased cAMP production in these cells (Fig. 3B), indicating the importance of EP4 in mediating cAMP responses in PANC-1 cells.

Fig. 3.

EP4 receptor mediates PGE2-induced cAMP response. A: PANC-1 cells were pretreated with antagonists for EP4 or EP2 (ONO-AE3-208 or PF-04418948, respectively) at 1 and 10 μM for 1 h and stimulated with PGE2 (1 μM) for 1 min, and levels of cAMP in cell lysates were determined. Values are expressed relative to untreated control. *P < 0.05 (by Student's t-test). B: PANC-1 cells were incubated with agonists for EP4 or EP2 (CAY10580 or butaprost, respectively) for 1 min, and levels of cAMP in cell lysates were determined. *P < 0.05 (by Student's t-test).

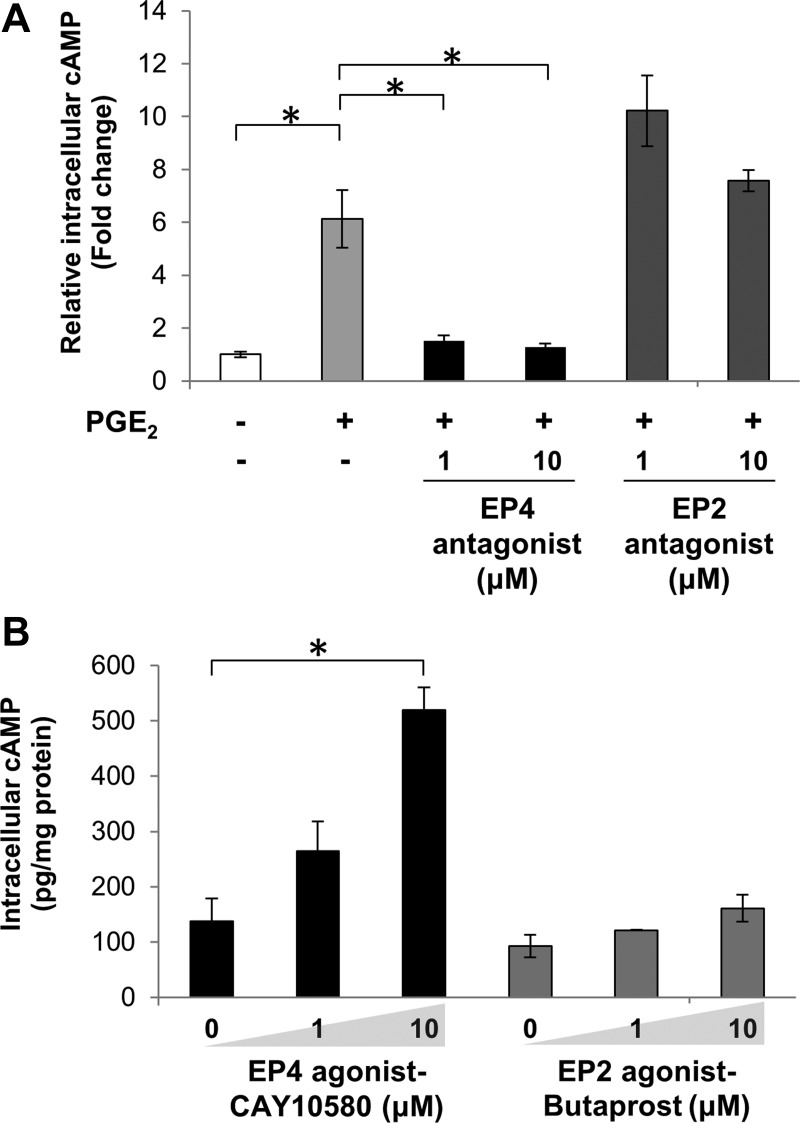

We next used pharmacological approaches to further substantiate a link between cAMP and mTORC1. The EP4 agonist CAY10580 promoted mTORC1 activation, as assessed by S6rp phosphorylation (Fig. 4A). Importantly, PGE2-activated S6rp phosphorylation (at Ser235/236 or Ser240/244) was prevented by the specific EP4 antagonist ONO-AE3-208 (Fig. 4B). These results reinforce the notion that PGE2-induced cAMP accumulation and subsequent responses are mainly mediated by the EP4 receptor in PANC-1 cells.

Fig. 4.

EP4 and PKA are involved in PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation. A: PANC-1 cells were treated with the EP4 agonist CAY10580 (10 μM) for 15 min. B: PANC-1 cells were pretreated with the EP4 antagonist ONO-AE3-208 (1 μM) for 1 h and then stimulated with or without PGE2 for 15 min. C: PANC-1 cells were pretreated with the PKA inhibitor H-89 (5 μM) for 1 h and stimulated with or without PGE2 (1 μM) for 15 min. After treatments, cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control.

The cAMP-dependent PKA is a central target of cAMP. Therefore, we used the PKA inhibitor H-89 to test whether PGE2-stimulated mTORC1 activation is PKA-dependent. Pretreatment of cells with 5 μM H-89 attenuated baseline and PGE2-activated S6rp phosphorylation (Fig. 4C), indicating a role for PKA in the cross talk between PGE2 signaling and the mTORC1 pathway. This finding is in agreement with previous results showing that PGE2-induced activation of p70S6K and S6rp paralleled an increase in the phosphorylation of CREB, a substrate of PKA (Fig. 1).

Ca2+ signaling contributes to PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation.

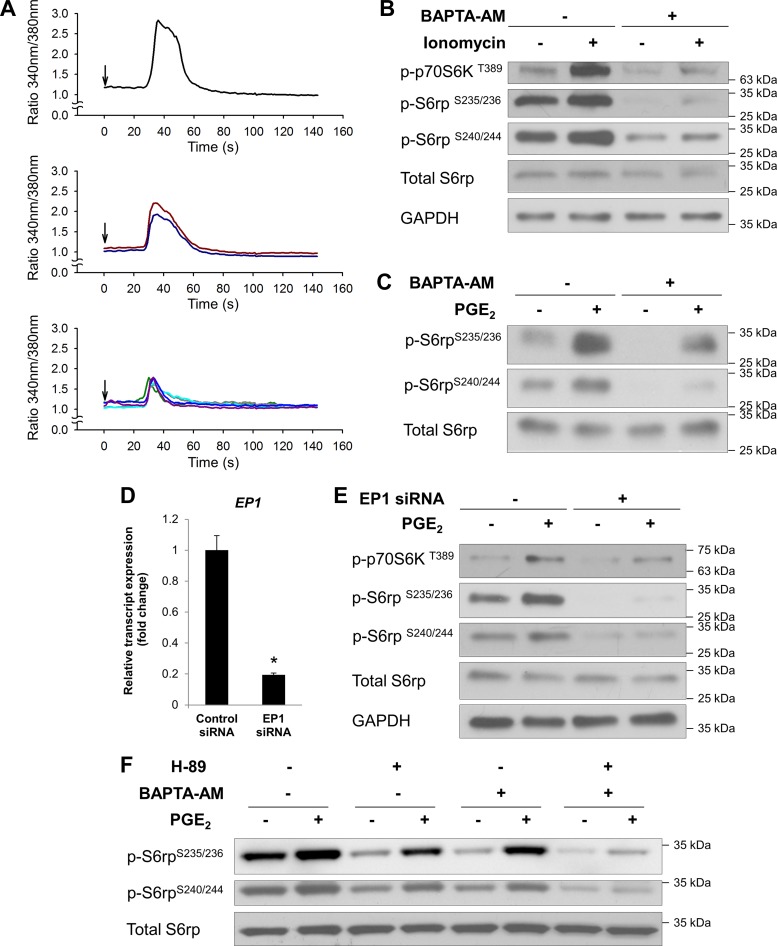

We noticed that treatment with H-89, at a concentration that completely blunted the forskolin-induced S6rp phosphorylation, did not fully inhibit PGE2-induced S6rp phosphorylation (at Ser235/236 or Ser240/244) (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that, besides cAMP, PGE2 may activate an additional pathway leading to mTORC1 activation. Ca2+ signaling has been implicated in the regulation of mTORC1 activation independently of PI3K/Akt (15, 31, 34). Consequently, PGE2 might exert some of its cAMP-independent effects through activation of EP1 receptors, which couple to Gαq and, thereby, promote phospholipase C-mediated formation of diacylglycerol and inositol trisphosphate, second messengers leading to PKC activation and Ca2+ mobilization, respectively (19). Initially, we examined whether PGE2 induces Ca2+ mobilization in PANC-1 cells. In agreement with this hypothesis, we found that addition of PGE2 to fura 2-loaded PANC-1 cells induced a rapid and transient increase in intracellular Ca2+ levels in PANC-1 cells (Fig. 5A). This microscopy-based measurement allowed us to monitor the Ca2+ response in individual cells and revealed that ∼62% of the cells (8 of 13) were responsive to PGE2 to varying extents (see representative traces in Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Ca2+ signaling is involved in PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation. A: PANC-1 cells were loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator fura 2-AM and stimulated with 1 μM PGE2 at the times marked by the arrows. Each trace represents results from a single cell. Top, middle, and bottom: different levels of responses in individual cells. B: PANC-1 cells were preincubated with the cell-permeable Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM (10 μM) for 1 h and then treated with 50 nM ionomycin (an ionophore that raises intracellular Ca2+ levels) for 15 min. C: PANC-1 cells were preincubated with 10 μM BAPTA-AM for 1 h and then stimulated with or without PGE2 (1 μM) for 15 min. After treatments, cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. D: PANC-1 cells were transfected with negative control siRNA or EP1 siRNA. After 4 days of incubation, total RNA was extracted from the cells and subjected to quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) using gene-specific primers for EP1 and ACTB (β-actin), which was used as an internal reference gene to normalize results. *P < 0.05 (by Student's t-test). E: PANC-1 cells were transfected with negative control siRNA or EP1 siRNA and then stimulated with or without PGE2 (1 μM) for 15 min. After treatment, cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as a loading control. F: PANC-1 cells were pretreated with H-89 (5 μM) and BAPTA-AM (10 μM), alone or in combination, and then stimulated with or without PGE2 (1 μM) for 15 min. After treatments, cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies.

Additionally, ionomycin, a Ca2+ ionophore that raises intracellular Ca2+ level, induced phosphorylation of p70S6K and downstream S6rp (Ser235/236 and Ser240/244) in these cells. This effect was markedly suppressed by BAPTA-AM, an intracellular Ca2+ chelator (Fig. 5B). Importantly, ionomycin was used in this experiment at a concentration (50 nM) that elicited an increase in intracellular Ca2+ comparable to that induced by PGE2 (data not shown).

To study the possible role of Ca2+ signaling in PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation, cells were pretreated with BAPTA-AM prior to PGE2 stimulation. As shown in Fig. 5C, phosphorylation (Ser235/236 and Ser240/244) of S6rp was significantly decreased by depletion of intracellular Ca2+. To further confirm that the Gαq-coupled EP1 receptor is involved in PGE2-stimulated mTORC1 activation, we utilized a genetic approach to specifically knock down the EP1 receptor subtype in these cells. Successful gene knockdown was validated by RT-qPCR assessing the levels of EP1 mRNA transcripts in EP1 siRNA-transfected vs. control siRNA-transfected PANC-1 cells (Fig. 5D). As a result, siRNA-mediated knockdown of EP1 blunted the PGE2-induced phosphorylation of p70S6K and S6rp (Ser235/236 or Ser240/244) (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that, besides cAMP/PKA signaling, a Ca2+-dependent pathway contributes to PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation via the EP1 receptor. This finding is reinforced by the data showing that PGE2-stimulated S6rp phosphorylation (Ser235/236 and Ser240/244) was abolished when both cAMP/PKA and Ca2+ signaling were blocked by the combination of H-89 and BAPTA-AM but were only partially inhibited by either treatment alone (Fig. 5F).

PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation requires both cAMP/PKA and Ca2+ pathways.

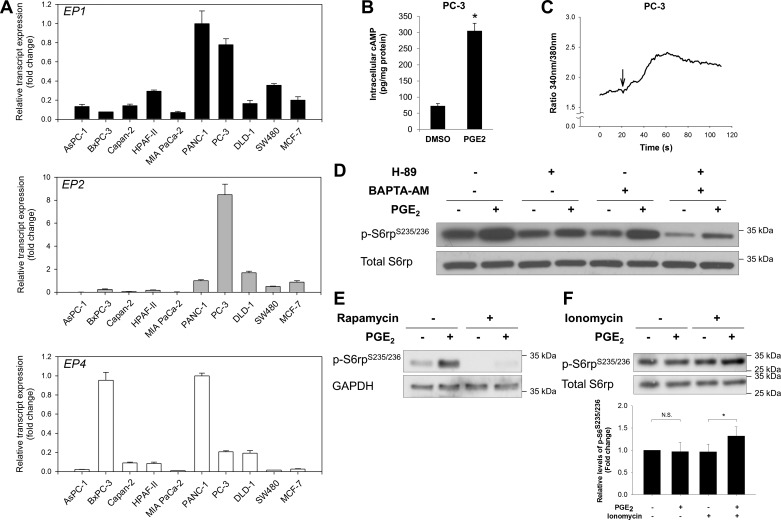

Our data suggest that both cAMP/PKA and Ca2+ pathways are important in mediating PGE2-induced activation of mTORC1. To test whether the effects of PGE2 on mTORC1 activation represent a cell type-specific or a more general phenomenon, we conducted an RT-qPCR screening of EP1, EP2, and EP4 expression in a variety of human cancer cell lines (Fig. 6A) derived from pancreatic (AsPC-1, BxPC-3, Capan-2, HPAF-II, MIA PaCa-2, and PANC-1), prostate (PC-3), breast (MCF-7), and colon (DLD-1 and SW480) cancers, all of which are notably associated with obesity. We found that the responsiveness of mTORC1 activation to PGE2 correlated well with the coexistence of highly expressed EP1 (mediating the Ca2+ response) and EP2 or EP4 (mediating the cAMP response), as exemplified by PANC-1 and PC-3 cells (Fig. 6A). In PC-3 cells, PGE2 robustly stimulated intracellular cAMP (Fig. 6B) and Ca2+ (Fig. 6C) levels and the phosphorylation of S6rp (Fig. 6D). Also, similar to the results in PANC-1 cells, the phosphorylation of S6rp was attenuated by H-89, BAPTA-AM, and rapamycin (Fig. 6, D and E). Furthermore, in BxPC-3 cells expressing abundant EP4 while substantially lacking EP1 transcripts, PGE2-induced phosphorylation (Ser235/236) of S6rp became evident only when intracellular Ca2+ level was increased by ionomycin to mimic EP1 receptor-mediated Ca2+ signaling (Fig. 6F). These findings suggest that PGE2-mediated mTORC1 activation depends on two separate signals, namely, cAMP (mediated by EP2 or EP4) and intracellular Ca2+ (mediated by EP1).

Fig. 6.

A: expression levels of EP1, EP2, and EP4 in a panel of cancer cell lines were determined by RT-qPCR. ACTB was used as an internal reference gene to normalize results. mRNA expression of each gene is presented relative to that of PANC-1 cells (set as 1-fold). B: PC-3 cells were incubated with DMSO or PGE2 (1 μM) for 1 min, and levels of intracellular cAMP in the cell lysates were determined. C: intracellular Ca2+ response to PGE2 in PC-3 cells. Trace represents averaged response of all cells. Arrow marks addition of PGE2. D: PC-3 cells were pretreated with H-89 (5 μM) or BAPTA-AM (10 μM), alone or in combination, and then stimulated with or without PGE2 (1 μM) for 15 min. After treatments, cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. E: PC-3 cells were pretreated with rapamycin (1 nM) for 30 min and then stimulated with or without PGE2 (1 μM) for 15 min. After treatments, cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. F: BxPC-3 cells were treated with PGE2 (10 μM), alone or in combination with ionomycin (500 nM), for 15 min. Top: cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. Bottom: quantitative densitometry of p-S6rp Western blots. Values are expressed relative to untreated control (set as 1-fold). NS, not significant. *P < 0.05 (by paired Student's t-test).

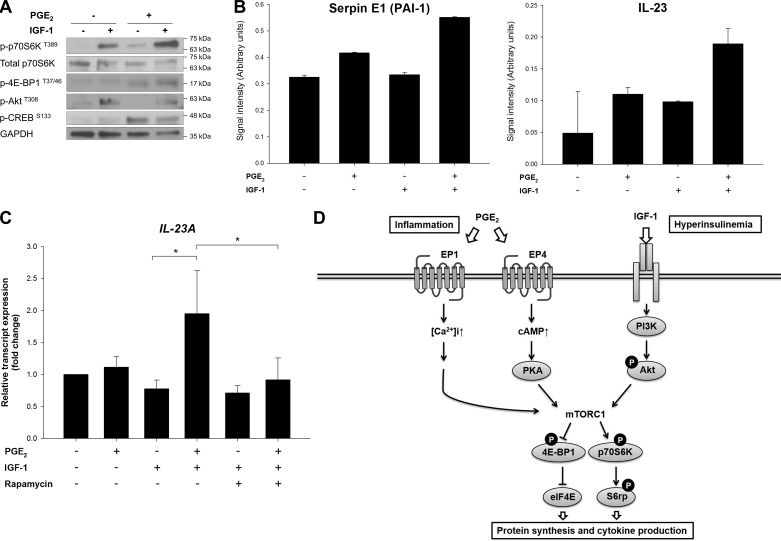

PGE2 potentiates the effect of IGF-1 through mTORC1 activation.

Our data suggest that, in addition to the canonical insulin/IGF-1-mediated signaling, mTORC1 can be coactivated by the inflammatory PGE2 pathway, which might potentiate the effects of insulin (and/or IGF-1). To investigate the interaction between these pathways, cells were treated with PGE2 in combination with IGF-1. As shown in Fig. 7A, PGE2 enhanced the effect of IGF-1 on the phosphorylation of p70S6K and 4E-BP1 downstream of mTORC1, suggesting reinforcement by the cross talk between the two pathways.

Fig. 7.

Potentiating cross talk between PGE2 and IGF-1 signaling pathways through mTORC1. A: PANC-1 cells were stimulated with IGF-1 (10 ng/ml) in the absence or presence of PGE2 (1 μM) for 15 min. After treatments, cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. B: relative levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI)-1 and IL-23 in PANC-1 cell supernatants collected after 24 h of indicated treatments were determined using a cytokine array. Values, expressed as signal intensity (arbitrary units), are averages quantified from duplicated spots on the array membrane. C: after 24 h of treatment with PGE2, IGF-1, and rapamycin, relative transcript expression levels of IL-23 in PANC-1 cells were determined by RT-qPCR. *P < 0.05 (by Student's t-test). D: schematic model showing cross talk between the PGE2 and IGF-1 pathways converging at mTORC1 implicated in obesity-associated tumor promotion. [Ca2+]i, intracellular Ca2+ concentration; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; eIF4E, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E; 4E-BP1, eIF4E-binding protein; p70S6K, ribosomal protein S6 kinase; S6rp, S6 ribosomal protein.

We next investigated phenotypical responses of these signaling events. There is considerable evidence suggesting the contribution of PGE2 to tumor development in many aspects of the immune and inflammation responses (18, 37). Since PGE2 mediates inflammation via cytokine production, we used a human cytokine protein array to measure a panel of cytokines released from PANC-1 cells exposed to PGE2, IGF-1, or the combination of the two stimuli. Among the 36 cytokines, chemokines, and acute-phase proteins, we identified two proteins that were especially upregulated by the combination of PGE2 and IGF-1, PAI-1 (also known as serpin E1), and IL-23, both of which are known to be proinflammatory (Fig. 7B). Further validation by RT-qPCR showed that IL-23 transcription in PANC-1 cells was promoted by treatment for 24 h with PGE2 and IGF-1 in combination, but not PGE2 or IGF-1 alone (Fig. 7C). Importantly, the upregulation of IL-23 expression was inhibited by rapamycin, confirming that IL-23 production is a consequence of the cross talk between PGE2 and IGF-1 signaling converging at mTORC1. Together, our studies reveal a novel cross talk between PGE2 signaling and the IGF-1/mTORC1 pathway (Fig. 7D). By regulating cytokine production, this cross talk may be of importance in amplifying the inflammatory response in the tumor microenvironment.

DISCUSSION

Obesity is a contributing factor in the development of a number of cancers, but the mechanisms driving this association remain unclear. Recent in vivo studies from our group and others strongly support the importance of the inflammatory environment in obesity-promoted pancreatic cancer (5, 40). To further elucidate the molecular mechanisms, we explored a potential link between proinflammatory signaling and hormone/growth factor pathways that are upregulated in obese and insulin-resistant subjects. Specifically, the results presented here identified a signaling cross talk between PGE2 and mTORC1 pathways in pancreatic cancer cells. Our data show that stimulation of PANC-1 cells with PGE2 increased the phosphorylation of molecules downstream of mTORC1, including p70S6K, S6rp, and 4E-BP1, indicating that PGE2 induces activation of mTORC1.

Associated with Gαs, EP2 and EP4 are known to mediate PGE2-induced intracellular cAMP production. Several previous studies linked a cAMP-dependent pathway to the PI3K/Akt/mTORC1 signaling module, but the underlying mechanisms vary among diverse cellular systems, implying cell context-specific processes (2, 3, 22). In epinephrine-stimulated rat skeletal muscle cells, cAMP can activate PI3K/Akt via Epac (exchange protein directly activated by cAMP), thereby augmenting the effect of insulin on PI3K/Akt signaling (2). In PANC-1 cells, however, PGE2/cAMP-induced activation of mTORC1 seems to be independent of PI3/Akt, as phosphorylation of Akt remained unchanged with PGE2 or forskolin stimulation. Also, cAMP-activated Epac is known to activate the Ras-associated protein-1 (Rap1)/B-Raf/ERK cascade (6, 27), which may be an alternative route to mTORC1 activation (33). However, there was no increase in phosphorylated ERK levels upon PGE2 treatment in PANC-1 cells. Subsequently, we showed that the effect of PGE2 or forskolin on mTORC1 activity was attenuated by H-89, suggesting the involvement of PKA, a major target of cAMP. This finding is in agreement with a previous study investigating cAMP-mediated mTORC1 signaling in thyroid cells induced with thyroid-stimulating hormone (51).

On the basis of the studies using agonist/antagonist for EP2 and EP4, our data suggest that, in PANC-1 cells, the PGE2-stimulated cAMP responses are predominantly mediated by EP4. Although the significance of EP4 in vivo remains to be determined, this finding is consistent with the notion that EP4 plays a major role in colorectal carcinogenesis (36, 42) and with a recent study showing that EP4 expression is markedly elevated in human pancreatic tumors compared with adjacent benign pancreatic tissues (13). Also, EP4-mediated mTORC1 activation by PGE2 has been recently demonstrated in colon (8) and prostate (53) cancer cells, reinforcing our findings in pancreatic cancer cells as a common concept, especially in obesity-associated cancers. In those previous reports, however, the significance of cAMP/PKA downstream of EP4 was not delineated. Importantly, in addition to the EP4/cAMP/PKA pathway, we found that PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation is also mediated by a Ca2+-dependent mechanism, which is elicited through the Gαq-coupled EP1 receptor, as supported by our results from the EP1 knockdown experiments. Although the role of EP1 in cancer development is less documented than the role of EP2 or EP4 (16), several studies have identified EP1 as a critical receptor (20, 52, 55). Furthermore, on the basis of the maximal inhibition achieved by the combined blockade of both arms of signaling with H-89 and BAPTA-AM, as well as the concurrence of high levels of EP2/EP4 and EP1 in the cell lines (PANC-1 and PC-3) that prominently displayed PGE2-activated mTORC1 signaling, we discovered the cooperative roles of cAMP/PKA and Ca2+ pathways in PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation. The expression patterns of EP receptors in PANC-1 (high in EP1 and EP4), PC-3 (high in EP1 and EP2), and BxPC-3 (high in EP2 only) cells suggest that, to induce PGE2-mediated mTORC1 activation, the functional integrity of both the EP1/Ca2+ pathway and the cAMP response is critical, and the latter may be evoked through either EP2 or EP4. Collectively, our studies using pharmacological and genetic approaches demonstrate that PGE2-induced mTORC1 activation is mediated by the coordinated operation of the EP4/cAMP/PKA and EP1/Gαq/Ca2+ pathways in PANC-1 cells (Fig. 7D).

Signaling pathways usually interact and cross talk with each other. A precise understanding of these complex networks may reveal critical mechanistic targets for therapeutic intervention devoid of unwanted side effects or resistance. For example, it has been shown in pancreatic cancer cells that the Akt/mTORC1 pathway mediates a cross talk between insulin receptor and GPCR signaling systems, where insulin can potentiate Ca2+ signaling triggered by Gαq-coupled receptor agonists (24). Remarkably, further studies revealed that such cross talk is disrupted by metformin, a widely used antidiabetes drug that negatively regulates mTORC1 through AMP kinase activation, leading to inhibition of pancreatic cancer growth (23). In the present study we have identified a similar, but reverse, cross talk between PGE2-mediated pathways and IGF-1 signaling, converging at mTORC1 and creating a positive reinforcement (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, PGE2 and IGF-1 in combination, but not alone, induced IL-23 mRNA transcription in PANC-1 cells, and this effect was abrogated by the mTORC1 inhibitor rapamycin. This finding highlights the significance of the reinforcing cross talk between PGE2 and IGF-1 signaling through subsequent mTORC1 activation. IL-23, a proinflammatory cytokine, has been shown to promote tumor growth by driving protumorigenic inflammation, as well as impairing T cell-mediated immune surveillance (25, 38). Also, a recent study suggests that PGE2 secreted from breast tumor cells, through cAMP/PKA signaling, induces IL-23 expression in the tumor microenvironment, leading to Th17 cell expansion (43). These novel findings raise the attractive possibility that PGE2 exerts its protumorigenic properties through regulation of proinflammatory cytokine production by augmentation of mTORC1 function, which is already supported by enhanced IGF-1/Akt signaling under certain conditions (e.g., the obese state and neoplasm). Overall, the signaling cross talk identified above would lead to an exacerbated inflammatory tumor microenvironment and, thereby, contribute to cancer development.

It is noteworthy that we also detected PGE2-induced phosphorylation of S6rp in mouse primary PanIN (pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia) cells, which are precancerous cells isolated from the conditional KrasG12D mouse model of pancreatic cancer (data not shown). These findings suggest that the cross talk between PGE2 and mTORC1 is not restricted to cancer cells but is also operational in early stages of pancreatic tumor development. Since both inflammation and insulin/growth hormones are key factors shared by obesity and cancer, this signaling cross talk is highly relevant to obesity-associated cancer, where proinflammatory PGE2 and systemic high levels of IGF-1 are conducive to tumor development. Given the well-known, potentially harmful cardiovascular side effects of COX-2 inhibitors (32) and feedback mechanisms of resistance associated with mTOR inhibitors (54), a deeper understanding of the molecular pathways involved in this link will facilitate the development of novel efficacious interventions while circumventing adverse effects.

In summary, our data link the PGE2 signaling to the IGF-1/Akt/mTORC1 module. The operation of this cross talk strongly supports the hypothesis that inflammation-associated PGE2 can reinforce the tumor-promoting effects of insulin/IGF-1 signaling. Since both pathways are implicated in obesity, as well as in cancer development, this notion may be of importance in elucidating the connection between obesity and enhanced cancer risk. Ultimately, a detailed understanding of these molecular links may provide novel targets for improved interventions for pancreatic cancer in an increasingly obese population.

GRANTS

This research was funded by National Cancer Institute Grant P01 CA-163200 (to G. Eibl), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases-supported CURE: Digestive Diseases Research Core Center Grant P30 DK-41301 (to E. Rozengurt), Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Grants I01BX001473 and R01DK100405 (to E. Rozengurt), and the Hirshberg Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer Research.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.-H.C., S.H.Y., J.S.-S., K.M.H., O.J.H., E.R., and G.E. developed the concept and designed the research; H.-H.C., S.H.Y., C.E.N.C., and A.M. performed the experiments; H.-H.C. and S.H.Y. analyzed the data; H.-H.C., S.H.Y., J.S.-S., E.R., and G.E. interpreted the results of the experiments; H.-H.C. and S.H.Y. prepared the figures; H.-H.C. drafted the manuscript; H.-H.C., S.H.Y., E.R., and G.E. edited and revised the manuscript; H.-H.C., S.H.Y., O.J.H., E.R., and G.E. approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bandi HR, Ferrari S, Krieg J, Meyer HE, Thomas G. Identification of 40S ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation sites in Swiss mouse 3T3 fibroblasts stimulated with serum. J Biol Chem 268: 4530–4533, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baviera AM, Zanon NM, Navegantes LC, Kettelhut IC. Involvement of cAMP/Epac/PI3K-dependent pathway in the antiproteolytic effect of epinephrine on rat skeletal muscle. Mol Cell Endocrinol 315: 104–112, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blancquaert S, Wang L, Paternot S, Coulonval K, Dumont JE, Harris TE, Roger PP. cAMP-dependent activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) in thyroid cells. Implication in mitogenesis and activation of CDK4. Mol Endocrinol 24: 1453–1468, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bracci PM. Obesity and pancreatic cancer: overview of epidemiologic evidence and biologic mechanisms. Mol Carcinog 51: 53–63, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson DW, Hertzer K, Moro A, Donald G, Chang HH, Go VL, Pandol SJ, Lugea A, Gukovskaya AS, Li G, Hines OJ, Rozengurt E, Eibl G. High-fat, high-calorie diet promotes early pancreatic neoplasia in the conditional KrasG12D mouse model. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 6: 1064–1073, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Rooij J, Zwartkruis FJ, Verheijen MH, Cool RH, Nijman SM, Wittinghofer A, Bos JL. Epac is a Rap1 guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor directly activated by cyclic AMP. Nature 396: 474–477, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 7: 79–94, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dufour M, Faes S, Dormond-Meuwly A, Demartines N, Dormond O. PGE2-induced colon cancer growth is mediated by mTORC1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 451: 587–591, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Bayoumy K, Iatropoulos M, Amin S, Hoffmann D, Wynder EL. Increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in rat lung tumors induced by the tobacco-specific nitrosamine 4-(methylnitrosamino)-4-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone: the impact of a high-fat diet. Cancer Res 59: 1400–1403, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frystyk J. Free insulin-like growth factors—measurements and relationships to growth hormone secretion and glucose homeostasis. Growth Horm IGF Res 14: 337–375, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funahashi H, Satake M, Dawson D, Huynh NA, Reber HA, Hines OJ, Eibl G. Delayed progression of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia in a conditional KrasG12D mouse model by a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor. Cancer Res 67: 7068–7071, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Funahashi H, Satake M, Hasan S, Sawai H, Newman RA, Reber HA, Hines OJ, Eibl G. Opposing effects of n-6 and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on pancreatic cancer growth. Pancreas 36: 353–362, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong J, Xie J, Bedolla R, Rivas P, Chakravarthy D, Freeman JW, Reddick R, Kopetz S, Peterson A, Wang H, Fischer SM, Kumar AP. Combined targeting of STAT3/NF-κB/COX-2/EP4 for effective management of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 20: 1259–1273, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenhough A, Smartt HJ, Moore AE, Roberts HR, Williams AC, Paraskeva C, Kaidi A. The COX-2/PGE2 pathway: key roles in the hallmarks of cancer and adaptation to the tumour microenvironment. Carcinogenesis 30: 377–386, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gulati P, Gaspers LD, Dann SG, Joaquin M, Nobukuni T, Natt F, Kozma SC, Thomas AP, Thomas G. Amino acids activate mTOR complex 1 via Ca2+/CaM signaling to hVps34. Cell Metab 7: 456–465, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hull MA, Ko SC, Hawcroft G. Prostaglandin EP receptors: targets for treatment and prevention of colorectal cancer? Mol Cancer Ther 3: 1031–1039, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Barzi F, Woodward M. Type-II diabetes and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Br J Cancer 92: 2076–2083, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalinski P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. J Immunol 188: 21–28, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawahara K, Hohjoh H, Inazumi T, Tsuchiya S, Sugimoto Y. Prostaglandin E-induced inflammation: relevance of prostaglandin E receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1851: 414–421, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawamori T, Uchiya N, Nakatsugi S, Watanabe K, Ohuchida S, Yamamoto H, Maruyama T, Kondo K, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Chemopreventive effects of ONO-8711, a selective prostaglandin E receptor EP1 antagonist, on breast cancer development. Carcinogenesis 22: 2001–2004, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khandekar MJ, Cohen P, Spiegelman BM. Molecular mechanisms of cancer development in obesity. Nat Rev Cancer 11: 886–895, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HW, Ha SH, Lee MN, Huston E, Kim DH, Jang SK, Suh PG, Houslay MD, Ryu SH. Cyclic AMP controls mTOR through regulation of the dynamic interaction between Rheb and phosphodiesterase 4D. Mol Cell Biol 30: 5406–5420, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kisfalvi K, Eibl G, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. Metformin disrupts crosstalk between G protein-coupled receptor and insulin receptor signaling systems and inhibits pancreatic cancer growth. Cancer Res 69: 6539–6545, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kisfalvi K, Rey O, Young SH, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. Insulin potentiates Ca2+ signaling and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis induced by Gq protein-coupled receptor agonists through an mTOR-dependent pathway. Endocrinology 148: 3246–3257, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langowski JL, Zhang X, Wu L, Mattson JD, Chen T, Smith K, Basham B, McClanahan T, Kastelein RA, Oft M. IL-23 promotes tumour incidence and growth. Nature 442: 461–465, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149: 274–293, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laroche-Joubert N, Marsy S, Michelet S, Imbert-Teboul M, Doucet A. Protein kinase A-independent activation of ERK and H,K-ATPase by cAMP in native kidney cells: role of Epac I. J Biol Chem 277: 18598–18604, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lashinger LM, Harrison LM, Rasmussen AJ, Logsdon CD, Fischer SM, McArthur MJ, Hursting S. Dietary energy balance modulation of Kras- and Ink4a/Arf+/−-driven pancreatic cancer: the role of insulin-like growth factor-1. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 6: 1046–1055, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 454: 436–444, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Markova B, Albers C, Breitenbuecher F, Melo JV, Brummendorf TH, Heidel F, Lipka D, Duyster J, Huber C, Fischer T. Novel pathway in Bcr-Abl signal transduction involves Akt-independent, PLC-γ1-driven activation of mTOR/p70S6-kinase pathway. Oncogene 29: 739–751, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marnett LJ. The COXIB experience: a look in the rearview mirror. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 49: 265–290, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendoza MC, Er EE, Blenis J. The Ras-ERK and PI3K-mTOR pathways: cross-talk and compensation. Trends Biochem Sci 36: 320–328, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Michel G, Matthes HW, Hachet-Haas M, El Baghdadi K, de Mey J, Pepperkok R, Simpson JC, Galzi JL, Lecat S. Plasma membrane translocation of REDD1 governed by GPCRs contributes to mTORC1 activation. J Cell Sci 127: 773–787, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris PG, Zhou XK, Milne GL, Goldstein D, Hawks LC, Dang CT, Modi S, Fornier MN, Hudis CA, Dannenberg AJ. Increased levels of urinary PGE-M, a biomarker of inflammation, occur in association with obesity, aging, and lung metastases in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 6: 428–436, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mutoh M, Watanabe K, Kitamura T, Shoji Y, Takahashi M, Kawamori T, Tani K, Kobayashi M, Maruyama T, Kobayashi K, Ohuchida S, Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Involvement of prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP4 in colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 62: 28–32, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakanishi M, Rosenberg DW. Multifaceted roles of PGE2 in inflammation and cancer. Semin Immunopathol 35: 123–137, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ngiow SF, Teng MW, Smyth MJ. A balance of interleukin-12 and -23 in cancer. Trends Immunol 34: 548–555, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osborn O, Olefsky JM. The cellular and signaling networks linking the immune system and metabolism in disease. Nat Med 18: 363–374, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Philip B, Roland CL, Daniluk J, Liu Y, Chatterjee D, Gomez SB, Ji B, Huang H, Wang H, Fleming JB, Logsdon CD, Cruz-Monserrate Z. A high-fat diet activates oncogenic Kras and COX2 to induce development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Gastroenterology 145: 1449–1458, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pollak M. The insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptor family in neoplasia: an update. Nat Rev Cancer 12: 159–169, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pozzi A, Yan X, Macias-Perez I, Wei S, Hata AN, Breyer RM, Morrow JD, Capdevila JH. Colon carcinoma cell growth is associated with prostaglandin E2/EP4 receptor-evoked ERK activation. J Biol Chem 279: 29797–29804, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qian X, Gu L, Ning H, Zhang Y, Hsueh EC, Fu M, Hu X, Wei L, Hoft DF, Liu J. Increased Th17 cells in the tumor microenvironment is mediated by IL-23 via tumor-secreted prostaglandin E2. J Immunol 190: 5894–5902, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roux PP, Shahbazian D, Vu H, Holz MK, Cohen MS, Taunton J, Sonenberg N, Blenis J. RAS/ERK signaling promotes site-specific ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation via RSK and stimulates cap-dependent translation. J Biol Chem 282: 14056–14064, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rozengurt E, Sinnett-Smith J, Kisfalvi K. Crosstalk between insulin/insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors and G protein-coupled receptor signaling systems: a novel target for the antidiabetic drug metformin in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 16: 2505–2511, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 65: 5–29, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh J, Hamid R, Reddy BS. Dietary fat and colon cancer: modulation of cyclooxygenase-2 by types and amount of dietary fat during the postinitiation stage of colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 57: 3465–3470, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Graubard BI, Chari S, Limburg P, Taylor PR, Virtamo J, Albanes D. Insulin, glucose, insulin resistance, and pancreatic cancer in male smokers. JAMA 294: 2872–2878, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Subbaramaiah K, Morris PG, Zhou XK, Morrow M, Du B, Giri D, Kopelovich L, Hudis CA, Dannenberg AJ. Increased levels of COX-2 and prostaglandin E2 contribute to elevated aromatase expression in inflamed breast tissue of obese women. Cancer Discov 2: 356–365, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 50.Sugimoto Y, Narumiya S. Prostaglandin E receptors. J Biol Chem 282: 11613–11617, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suh JM, Song JH, Kim DW, Kim H, Chung HK, Hwang JH, Kim JM, Hwang ES, Chung J, Han JH, Cho BY, Ro HK, Shong M. Regulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Akt/protein kinase B, FRAP/mammalian target of rapamycin, and ribosomal S6 kinase 1 signaling pathways by thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and stimulating type TSH receptor antibodies in the thyroid gland. J Biol Chem 278: 21960–21971, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tober KL, Wilgus TA, Kusewitt DF, Thomas-Ahner JM, Maruyama T, Oberyszyn TM. Importance of the EP1 receptor in cutaneous UVB-induced inflammation and tumor development. J Invest Dermatol 126: 205–211, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vo BT, Morton D Jr, Komaragiri S, Millena AC, Leath C, Khan SA. TGF-β effects on prostate cancer cell migration and invasion are mediated by PGE2 through activation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Endocrinology 154: 1768–1779, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wander SA, Hennessy BT, Slingerland JM. Next-generation mTOR inhibitors in clinical oncology: how pathway complexity informs therapeutic strategy. J Clin Invest 121: 1231–1241, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watanabe K, Kawamori T, Nakatsugi S, Ohta T, Ohuchida S, Yamamoto H, Maruyama T, Kondo K, Ushikubi F, Narumiya S, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Role of the prostaglandin E receptor subtype EP1 in colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 59: 5093–5096, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]