Abstract

Primordial germ cells (PGCs) share many properties with embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and innately express several key pluripotency-controlling factors, including OCT4, NANOG, and LIN28. Therefore, PGCs may provide a simple and efficient model for studying somatic cell reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), especially in determining the regulatory mechanisms that fundamentally define pluripotency. Here, we report a novel model of PGC reprogramming to generate iPSCs via transfection with SOX2 and OCT4 using integrative lentiviral. We also show the feasibility of using nonintegrative approaches for generating iPSC from PGCs using only these two factors. We show that human PGCs express endogenous levels of KLF4 and C-MYC protein at levels similar to embryonic germ cells (EGCs) but lower levels of SOX2 and OCT4. Transfection with both SOX2 and OCT4 together was required to induce PGCs to a pluripotent state at an efficiency of 1.71%, and the further addition of C-MYC increased the efficiency to 2.33%. Immunohistochemical analyses of the SO-derived PGC-iPSCs revealed that these cells were more similar to ESCs than EGCs regarding both colony morphology and molecular characterization. Although leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) was not required for the generation of PGC-iPSCs like EGCs, the presence of LIF combined with ectopic exposure to C-MYC yielded higher efficiencies. Additionally, the SO-derived PGC-iPSCs exhibited differentiation into representative cell types from all three germ layers in vitro and successfully formed teratomas in vivo. Several lines were generated that were karyotypically stable for up to 24 subcultures. Their derivation efficiency and survival in culture significantly supersedes that of EGCs, demonstrating their utility as a powerful model for studying factors regulating pluripotency in future studies.

Introduction

During embryogenesis, unipotent human primordial germ cells (PGCs) undergo epigenetic reprogramming to establish totipotency at fertilization [1–4]. PGCs can be de-differentiated in vitro under the appropriate cell culture conditions to form embryonic germ cells (EGCs) [5] or from spermatogonial stem cells to form germline stem cells (GSCs). In rare cases, malignant changes in PGCs occur after birth resulting in teratocarcinomas from which pluripotent embryonic carcinoma cells (ECCs) are derived [6]. Like embryonic stem cells (ESCs), stem cells derived from PGCs exhibit the ability to indefinitely self-renew and differentiate into the three somatic germ layers under certain circumstances [7–13]. This is important because PGCs express many of the master regulatory factors that facilitate pluripotency despite the fact that PGCs are committed to produce unipotent cells [14,15]. As such, stem cells derived from PGCs have been used as effective models for identifying key pathways that regulate dedifferentiation and reprogramming [16,17]. Previous studies primarily performed in mouse cells and in human ECCs have shed light on key regulatory pathways governing pluripotency, and importantly have revealed species-specific differences in the reprogramming mechanisms utilized by mouse and human stem cells (for review, see Na et al. [18], Kerr and Cheng [19], and Buecker et al. [20]). The process of regulating pluripotency is an important issue for the study of human development and disease and for developing stem cell-based therapies. For instance, the identification of factors that regulate pluripotency has enabled adult tissue to be reprogrammed into ESC-like stem cells by introducing transcription factors to somatic cells [8,21,22]. Thus, a robust model for studying human PGCs is needed.

To date, the study of stem cells derived from human PGCs is confounded by various limitations. Embryonal carcinoma cells, which are stem cells of teratocarcinomas, exhibit karyotypic abnormal and are potentially malignant [23]. Although ECCs have been recently shown to be reverted to pluripotency via Yamanaka's factors [24], their malignancy along with gross chromosomal abnormalities make it difficult to discern the pathways involved in oncogenesis compared to their pluripotent nature. GSCs, like EGCs, propagate via colonies and maintain primarily stable karyotypes. However, human GSCs and EGCs, unlike their mouse counterparts, are difficult to derive and to maintain over long-term subculture, which has been demonstrated by only a handful of laboratories including our own [25–27]. Furthermore, although human GSCs and EGCs can be differentiated into all three germ layers in vitro [25,28–30], they have not demonstrated the ability to produce teratomas in vivo [25,28–30]. These attributes of human GSCs and EGCs make them more difficult to study and an inefficient model for studying the process of PGC reprogramming.

In light of these challenges, the ability to reprogram PGCs can serve as a simple model for studying the signaling pathways controlling pluripotency. In fact, PGCs innately express several key pluripotency controlling factors such as OCT4, NANOG, and LIN28 and share a similar epigenetic signature as stem cells compared to somatic cells [31–33]. Thus, given the striking molecular similarities that PGCs share with pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), PGCs may provide the simplest model for studying cellular reprogramming. We hypothesized that the reversion of PGCs into the pluripotent state would involve the fewest required steps, comprising only the essential processes and transcription factors. Furthermore, the mechanisms that regulate the conversion of PGCs into a pluripotent ESC-like state may parallel the mechanisms involved in fundamentally defining pluripotency and somatic cellular reprogramming.

The ability of somatic cells to reprogram into a pluripotent state has been established. These cells, known as induced PSCs (iPSCs), are generated by the forced expression of reprogramming factors known to drive pluripotency and self-renewal. Since the development of iPSCs using four reprogramming factors OCT4 (O), SOX2 (S), KLF4 (K), and C-MYC (M), numerous studies have enhanced the generation of iPSCs from somatic cells using small molecules such as miRNAs and epigenetic modulators [9,34]. Despite these recent advances, the efficiency of iPSC generation and the maintenance of genetically stable iPSC lines are still intensely studied, and the mechanisms that regulate reprogramming remain unknown.

Here, we demonstrate that human PGCs can be reprogrammed to pluripotency, creating induced pluripotent genetically engineered EGCs (PGC-iPSCs) with high efficiency. We also determined the minimal requirements converting PGCs to a pluripotent state via lentiviral transfection with only two transcription factors, OCT4 and SOX2. PGC-iPSCs were also derived based on a nonintegrative approach using Sendai virus (SeV) particles containing replication-competent RNAs that encode the reprogramming factors [35]. The derived PGC-iPSCs were more similar morphologically and molecularly to ESCs than EGCs and demonstrated the ability to form teratomas of all three germ layers in vivo, which marks the first such report of human PGC-derived iPSCs to date. Thus, we demonstrate the successful high-efficiency conversion of human PGCs into stable iPSCs, providing an effective, easy method to derive and sustain a PGC-based model for studying the signaling cascades responsible in the OCT4 and SOX2 regulation of reprogramming. We propose that PGC-iPSCs can be used as a powerful model for studying the mechanisms that control reprogramming and provides the first robust model of ESC-like cell lines generated from human germ cells.

Materials and Methods

Tissue collection

Gonadal tissue was acquired from an NIH-funded tissue repository (UW) from the gonadal ridges and mesenteries of 6- to 10-weeks post fertilization human embryos (obtained as a result of therapeutic termination of pregnancy). A small portion of the tissue was frozen in O.C.T. freezing compound (Tissue-Tek) and stored at −80°C for sex determination. Gestational age was estimated from a comparison of anatomical markers including crown-heel and crown-rump measurements, limb and digit formation and also the first day of the last maternal menstrual cycle. Sex was determined by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) using CEP X Spectrum Orange probe fluorescence and CEP Y Spectrum Green (Vysis) according to standard procedures used by our laboratory [36].

PGC isolation and EGC derivation

PGCs were isolated from the embryonic gonads and cultured as previously described [29]. Briefly, dissected gonads were dissociated in trypsin at 37°C for 5 min and PGCs were isolated using magnetic cell sorting technology (MACs). This was performed using indirect labeling of cells with magnetically tagged goat anti-mouse IgM antibodies toward a mouse-anti-SSEA1 antibody (Miltenyi Biotech). The PGCs were incubated with stage-specific embryonic antigen (SSEA1) antibody (1:5 dilution) for 15 min on ice. Afterward, secondary antibody was applied at 1:100 dilution for another 30 min on ice and sorted on magnetic columns, as previously described [37,38]. For EGC derivation, SSEA1+ PGCs were seeded into 12 wells of a 96-well plate with irradiated mouse embryonic feeder cells, SIM 6-thioguanine resistant ouabain (STO) (∼125,000 cells/well; ATCC) [37–39] in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 15% fetal bovine serum, 1,000 units/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), 2 ng/mL fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2) (R&D Systems), and 10 μM Forskolin (Sigma). EGC derivation was performed from 10 different sources of tissue.

Human ESC culture

Human ESCs from the H1 line (Fed ID# 0043; WiCell) were cultured on matrigel (BD Biosciences) in 10-cm cell culture dishes with DMEM/F12-10% knockout serum replacement containing (ESC) media conditioned by mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (MEFs) and supplemented with 4 ng/mL FGF2, as previously described [23]. ESCs were routinely maintained on MEFs mitotically inactivated with 5,000 rads of γ-radiation and passaged every 3–5 days after disaggregation with 1 mg/mL collagenase.

Lentiviral production and iPSC generation

Lentivirus production was performed using Gateway®-compatible cDNAs for SOX2 (S), OCT4 (O), KLF4 (K), and C-MYC (M) (Invitrogen) inserted via recombination with LR Clonase into a modified (attR1, attR2) pLVX-Puro vector (Clontech) using the Gateway recombination system (Invitrogen). Purified, high titer VSV-G pseudotyped lentiviral preps for the expression of each transgene were prepared using standard methods. SSEA1+ PGCs were isolated and cultured for 24 h then transduced with replication-defective recombinant lentivirus for 24 h at multiplicity of infections (MOIs) [40] of 5–10 for each construct in the presence of 6 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma). To study the derivation efficiencies due to various factors, the PGCs were transfected with the following combination of vectors: S, O, SO, SOK, SOM, SK, SM, KM, and SKM.

Colonies were selected 7–10 days after colony formation, which corresponded to ∼14–20 days after viral infection. Clones were generated from single colonies with the appropriate tight and rounded morphology of mouse ESCs as reported using a combination of this morphology criteria and TRA-1-60 live staining [41–44]. After picking iPSCs were maintained in culture in ESC media on irradiated MEFs in the presence of 10 ng/mL FGF2 or in conditioned ESC media on matrigel. Sub-passaging was performed as described for ESCs. Lentiviral transgene expression was confirmed using quantitative real-time (qRT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis with transgene-specific primers.

SeV reprogramming

SeV reprogramming of human PGCs was performed, as previously described [45,46], using a Cytotune reprogramming kit (Lifetech) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The day before transduction, ∼100,000 PGCs were plated in PGCIII medium in a 6-well plate, and on day 0, the cells were incubated with virus at a MOI of 3 for 24 h. Afterward, the media was changed, and the cells fed every other day. By day 10, TRA-1-60+ colonies were mechanically selected and passaged as clumps, as previously described [47]. The cells were then replated onto 0.1% gelatin-coated 60-mm dishes containing mitomycin C-treated MEFs (CF1 mouse strain from Millipore) in ESC medium. Sub-passaging was performed as described for ESCs.

qRT-PCR analysis

RNA was isolated for qRT-PCR using MiniRNeasy kits (Qiagen 74124) with the RNA clean-up protocol and optional on-column DNase treatment. Complementary DNA was generated with SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System RT Kits, following the manufacturer's instructions (INV18080-051). qRT-PCR analysis was performed using ABi7900HT with TaqMan Assay-on-Demand designed oligonucleotides for the detection of OCT4, SOX2, C-MYC, and KLF4, and each sample had a template equivalent to 5 ng of total RNA (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary materials are available online at http://www.liebertpub.com/scd). Quantification was performed using the ΔΔCt method and normalized to β-actin. Each primer set was tested for each of three to five clonal iPSC lines per treatment.

Microarray analysis

To analyze gene expression profiles, the Affymetrix Human U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChip was used. RNA extraction, reverse transcription, cRNA preparation, and chip hybridization were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Affymetrix). In brief, total RNA was extracted from the cultured cells using RNeasy (Qiagen) protocols described below for RT-PCR. Five micrograms of purified RNA were then used as a template for double-stranded cDNA synthesis primed using a T7-(dT)24 oligonucleotide. Double-stranded cDNA was then used as a template for biotin-labeled cRNA preparation using T7 RNA polymerase. Biotinylated cRNA (15 μg) was fragmented at 94°C for 35 min (100 mM Tris-acetate pH 8.2, 500 mM potassium acetate, 150 mM magnesium-acetate), and hybridized to the Affymetrix HG U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChips containing ∼54,000 transcripts for 16 h at 45°C with constant rotation (60 rpm). An Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450 was used to remove the nonhybridized target and to incubate with a streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate to stain the biotinylated cRNA. The staining was amplified using goat IgG as blocking reagent and biotinylated goat anti-streptavidin antibody, followed by a second staining step with a streptavidin-phycoerythrin conjugate. Fluorescence was detected using the Affymetrix G3000 GeneArray Scanner and image analysis of each GeneChip was done through the GeneChip Operating System 1.4 (GCOS) software from Affymetrix, using the standard default settings. Statistical analyses of microarray data were performed using a combination of bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org) and Partek™ software (Version 6.5) (http://www.partek.com). The raw signal values were normalized with quantile normalization method and gene level expression was summarized using the Robust Multi-Array method [48]. A false discovery rate-adjusted P-value cutoff of < 0.0001 was used to obtain the lists of differentially expressed genes. Hierarchical clustering and scatter plot analyses were performed using Spotfire (Version 9.1.1). The analysis was performed twice for each clonal iPSC line tested.

Immunocytochemistry and quantitative analysis

For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min followed by 10 min in 0.3% triton in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Antibodies and the concentrations used are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. Briefly, antibodies were diluted in 15% goat serum in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) and incubated with tissue for 1 h at room temperature (RT). All antibodies were detected using fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution; Millipore) in 15% goat serum in DPBS for 1 h at RT. Cells were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma) to detect nuclei. Negative controls were also performed using the secondary antibodies alone. For fluorescent quantitative analysis, images were imported into Metamorph Imaging Software (Version 7.7). The average fluorescence units were calculated by dividing the total fluorescent intensity by area. Three areas within single colonies or PGC cell clusters were measured per image, and at least six colonies were examined per experimental group. The background fluorescence, measured in an adjacent area containing no cells, was subtracted from each image, as previously described [11].

Karyotyping

Stem cell cultures at passages P20 up to P33 were prepared by passaging a confluent culture in a 60 mm cell culture dish at 50%–70% confluence on the day of sampling. Cells were incubated with 0.02 μg/mL colcemid for 1 h, washed in PBS, trypsinized, and spun down. The pellet was resuspended carefully in hypotonic solution (0.075 M KCl) to obtain a single cell suspension and left at RT for 6 min. After spinning and removing the hypotonic solution, the cells were fixed with 5 mL of ice-cold fixative (methanol:acetic acid in a 3:1 ratio), added drop wise to the suspension, left at RT for 5 min, and spun down. The cells were then dropped onto slides and stained with Giemsa. For each cell line, at least 20–30 metaphases were examined. Only lines exhibiting normal karyotypes were analyzed for this study.

Teratoma formation

Undifferentiated PGC-iPSCs or control group ESCs were prepared as a single cell suspension by collagenase treatment, resuspended in PBS containing 30% Matrigel Basement membrane matrix (BD Bioscience) and 5,000,000 cells were intramuscularly injected into the ventral flanks of 5-week-old nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD-SCID) mice, using a 26.5 gauge needle [49]. Mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions, and observed routinely once a week until tumor growth was observed and then three times a week thereafter. Tumor growth was measured with a caliper. They were sacrificed after tumors were larger than 1.5 cm3 and brain, liver, lungs and spleen of all animals were inspected for tumor invasion. Teratomas were visible in mice studied between 8 and 12 weeks and excised for tissue processing. Six mice were used per cell line (two tumors per mouse). Tumor growth was monitored by measuring tumor diameter and calculating tumor volume using the formula, volume = 4/3π × (diameter/2)3 [50]. Mice were euthanized by injection of 250 μL of a 2.5% stock of Avertin per mouse followed by cervical dislocation of the neck. Tumor samples were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin at 60°C, cut into 10 μM sections, and stained with Hematoxylin and eosin. These experiments were reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-tests were performed to determine statistical significance between groups for all experiments. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

PGC, EGC, and ESC comparisons

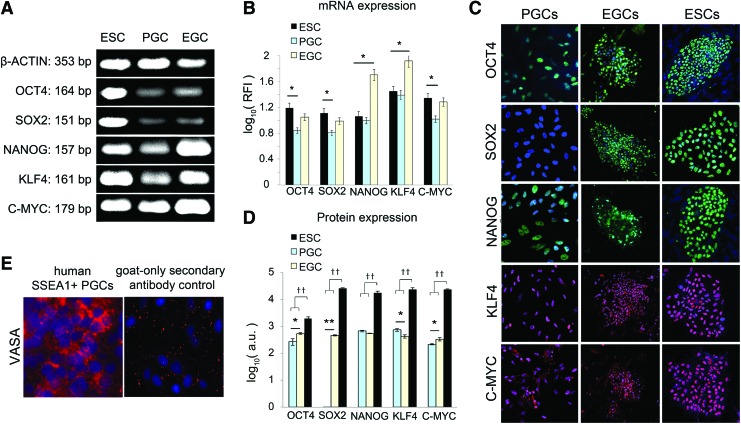

PGCs were isolated as previously described [31] using magnetic-activated cell sorting with antibodies against the germ cell marker SSEA1. After isolation, the PGCs were split into cultures that were used to generate EGCs or were transfected with various combinations of reprogramming factors to generate iPSCs. Previous microarray analyses have suggested that human PGCs express lower levels of OCT4 and SOX2 mRNA compared with EGCs and ESCs [31]. Figure 1A shows single bands from the RT-PCR analysis for OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and C-MYC mRNA expression in representative samples of PGCs, EGCs, and ESCs. Beta-actin was used as a loading control. At least five different lines from PGCs and EGCs were compared by semi-qRT-PCR to the human ESC line. Figure 1B shows that PGCs expressed significantly lower SOX2, OCT4, and C-MYC mRNA levels compared with sEGCs and ESCs. Although, OCT4 mRNA levels were detected in PGCs, OCT4 expression was ∼30% lower in PGCs compared with EGCs and ESCs. PGCs expressed similar levels of KLF4 and NANOG compared to ESCs. Interestingly, EGCs exhibited the highest levels of NANOG and KLF4 mRNA, consistent with our previous report [31].

FIG. 1.

(A) Semi-quantitative reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR analysis of OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF4, and C-MYC expression in representative samples of embryonic stem cells (ESCs), primordial germ cells (PGCs), and embryonic germ cells (EGCs) using β-ACTIN as a loading control. (B) Semi-quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR analysis of OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF4, and C-MYC, reported as the log value of relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) relative to β-ACTIN. PGCs exhibited reduced expression of OCT4 and SOX2 compared to human EGCs and ESCs. *P < 0.05 compared to ESCs (n = 5 sublines per cell type were ran in triplicate). (C) Indirect immunofluorescence staining for the stem cell markers OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF4, and C-MYC showing representative images of PGCs, EGCs, and ESCs. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (D) The average fluorescence units (arbitrary units, a.u.) were calculated by dividing the total fluorescent intensity per area. Three areas within each single colony or PGC cell clusters were measured per image, and at least six colonies were examined for each subline and three sublines were stained per cell type. The protein expression of ESCs was compared to both the PGCs and EGCs (t-test, ††P < 0.01). The protein expressions of PGCs were also compared with EGCs (t-test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (E) Expression of germ cell marker VASA (red) in human SSEA1+ sorted PGCs (left) compared to goat only secondary antibody controls (right) confirm the germ cell origins of the PGCs and EGCs studied in these experiments. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Immunocytochemistry was then utilized to confirm the endogenous protein expression of OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF4, and C-MYC in at least five lines of PGCs, EGCs, and ESCs. Each protein was measured in triplicate for each group from at least five different PGC and EGC lines, and representative immunocytochemistry images are shown in Fig. 1C. The ESCs expressed significantly greater levels of all five proteins that were measured, OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF4, and C-MYC, compared to both ECGs and PGCs (Fig. 1D). The lower protein levels in EGCs compared with ESCs could be explained by the increased heterogeneity of staining within EGC colonies and is likely related to the tendency of human EGCs to lose their pluripotency and spontaneously differentiate in culture. In contrast, the PGCs expressed lower levels of OCT4 and C-MYC compared with EGCs and no detectable level of SOX2. The lack of SOX2 expression was confirmed by western blots (data not shown) and is consistent with previous reports [51]. The PGCs also expressed significantly higher KLF4 compared with EGCs, whereas the expression of NANOG was not significantly different between the PGCs and EGCs.

Of interest is that the mRNA expression (Fig. 1B) was not always consistent with protein expression (Fig. 1D) in PGCs and EGCs. The protein expression of OCT4, SOX2, and C-MYC were consistent with their relative mRNA expression, which followed ESCs > EGCs > PGCs for both mRNA and protein expression. However, EGCs expressed the highest levels of KLF4 and NANOG mRNA expression, yet their protein expression was significantly lower compared to ESCs, suggesting that EGCs differ in their post-transcription regulation of these proteins. Additionally, significant amounts of SOX2 mRNA were measured in the PGCs, but the SOX2 protein was undetectable via both immunocytochemistry and western blot, in agreement with a previous study that reported undetectable SOX2 in human PGCs [51]. Staining for VASA, a germ cell-specific marker found only in immature germ cells, was also performed to confirm the germ cell origin of the PGCs (Fig. 1E).

PGC-iPSC derivation

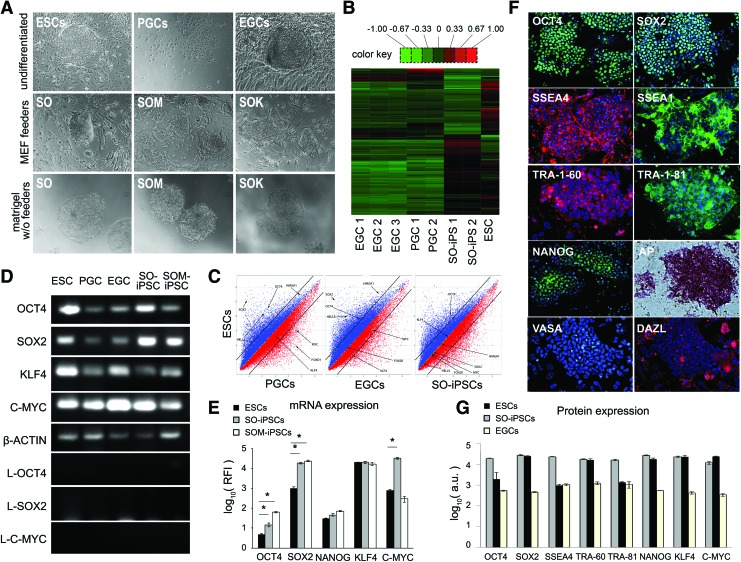

PGCs were transduced with a lentivirus containing the following nine combinations of transcription factors: SOX2 (S); OCT4 (O); SOX2 and OCT4 (SO); SOX2, OCT4, and C-MYC (SOM); SOX2, OCT4, and KLF4 (SOK); SOX2 and KLF4 (SK); SOX2 and C-MYC (SM); KLF4 and C-MYC (KM); or SOX2, KLF4, and C-MYC (SKM). Figure 2A shows representative colony morphologies of the iPSC lines ∼2 months after transduction compared to undifferentiated ESCs, PGCs, and EGCs. Colonies were selected 10 days after colony formation, and lines from single colonies were maintained on feeders. Thus, the PGC-derived iPSC lines were established from cell clumps by selecting individual colonies, not single cells, as demonstrated for mouse ESCs and iPSCs [19]. The iPSC colonies were able to generate embryoid bodies when cultured under nonadherent conditions and survive multiple freeze-thaw cycles (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

(A) Phase contrast images showing colony morphology of undifferentiated human ESCs on mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) feeders, PGCs on matrigel and EGCs on MEF feeders (top row); and single colonies of selected induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) lines (passage 12) transduced by lentivirus containing the genes SO, SOM, or SOK and plated on MEF feeders (middle row) or on matrigel in MEF-conditioned media without feeders (bottom row). S, Sox2; O, Oct4; M, cMyc; K, Klf4. Magnification at 20 × . (B) Heat map of the global gene analysis of EGCs, PGCs, SO-iPSCs, and ESCs relative to β-ACTIN. Hierarchical analysis shows genes that are the topmost differentially expressed among lines (high expression in red, log10 = >1.00; low expression in green; log10 = <− 1.00). (C) Scatter plot analyses from microarray data comparing global gene expression patterns between ESCs versus PGCs, ESCs versus EGCs, and ESCs versus SO-iPSCs (passage 20). Black lines indicate 2-fold changes in gene expression levels between the paired cell types. Genes overexpressed in ESCs are represented in blue and those underrepresented in ESCs are indicated in red. Gene expression levels were normalized using the Robust Multi-Array algorithm. (D) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR of endogenous gene expression in SO-derived and SOM-derived iPSCs (10 weeks after transduction), progenitor PGCs cells, ESCs, and EGCs. Exogenous expression of OCT4, SOX2, and C-MYC generated from lentiviral integration were no longer expressed in the iPSC lines at this time. Representative images from 10 independent clonal sublines from each cell type. (E) qRT-PCR analysis. Expression levels were normalized against β-ACTIN and plotted relative to normal human fibroblasts using the delta delta threshold cycle (Ct) method. Ct values obtained after 40 cycles of amplification for lentivirus integrated genes were not detected. *P < 0.05 compared to ESCs. (n = 3 sublines generated from independent biological samples, performed in technical triplicate). (F) Immunocytochemical analyses of PGC-derived SO-iPSC after 10 weeks. Cells transduced with SOX2 and OCT4 express PSC markers SSEA4 (red), SSEA1 (green), Tra-1-60 (green), Tra-1-81 (green), NANOG (green) AP (purple), and germ cell markers VASA (green) and DAZL (red). Nuclei are stained with DAPI. (G) The average fluorescence units (a.u.) were calculated by dividing the total fluorescent intensity per area. Three areas within each single colony were measured per image, and at least six colonies were examined from three sublines per cell type (t-test, P < 0.05). Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

PGC-iPSC colonies could also be grown on matrigel in the absence of MEF feeders using conditioned media in a fashion similar to traditional ESC cultures. On feeders, the PGC-iPSC colonies displayed a rounded morphology, which is similar to EGCs and mouse ESCs and in contrast to the flat morphology of human ESCs. Controls for iPSC generation included SSEA1neg gonadal cells, which did not produce colonies past 3 weeks. SSEA1+ PGCs that were transfected with only polybrene never produced colonies. Ten days after colony formation, colonies were picked and clonal lines maintained for over 6 months.

Because PGCs are similar to PSCs in key aspects of their stem cell genetic and epigenetic signature, we speculated that upregulating expression of SOX2 and OCT4 would be sufficient in driving PGCs toward a pluripotent state. To test this hypothesis, the efficiencies of reprogramming using the nine different combinations of S, O, K, and M transcription factors in SSEA1+ PGCs were measured (Table 1). The initial efficiency of conversion was determined by the number of colonies produced 14 days after viral transfection. A minimum of 10 lines for each combination were tested. The lowest iPSC efficiencies were observed for all transcription combinations that did not contain both OCT4 and SOX2: S (0.02%), O (0%), SK (0%), SM (0%), KM (0%), and SKM (0%). The efficiency of SO-derived iPSCs was 1.71%, while SOM-derived iPSCs reached the highest derivation efficiency of 2.33%. The efficiency of deriving iPSCs using the SOK combination was only 0.50%, ∼3-fold lower than the SO combination. When PGCs were derived using a nontransgene approach with SeV RNA, the overall efficiency was lower in all groups (Supplementary Fig. S1A). However, the trend remained the same in the efficiencies of derivation such that transiently elevated levels of SOX2 and OCT4 by RNA virus was sufficient to generate stable iPSC colonies after 10 weeks. In addition, SOM RNA transfection did show slightly higher derivation efficiency compared with SO alone, similar to that seen using the lentiviral approach.

Table 1.

Derivation Efficiency of Human iPSCs from PGCs with Various Transcript Factor Combinations Using Lentivirus

| Cell line | No. of initial colonies | Efficiency of 50,000 cells plated (%) |

|---|---|---|

| O | 0 | 0.00 |

| S | 10 ± 2.3 | 0.02 |

| SO | 857 ± 29.5 | 1.71 |

| SOM | 1,165 ± 125 | 2.33 |

| SOK | 252 ± 34 | 0.50 |

| SK | 0 | 0.00 |

| SM | 0 | 0.00 |

| KM | 0 | 0.00 |

| SKM | 0 | 0.00 |

iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cells; PGC, primordial germ cell.

In addition to studying the factors required to derive PGC-iPSCs, the factors influencing their derivation and maintenance in culture were also examined. To dispel concerns of contaminating mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in the iPSC cultures, we examined the ability of the iPSCs and parental PGC populations to grow in the absence of FGF2, as MSCs are known to thrive without this growth factor in culture. Neither the PGCs nor the derived iPSCs were able to survive without FGF2, confirming that the cells were not of MSC origin (data not shown).

Another factor utilized in human EGC derivation and maintenance is LIF. Although LIF is not required in human ESC and iPSC cultures, it has been reported to facilitate human iPSC derivation [52,53]. Thus, we compared the efficiency of deriving PGC-iPSCs in the presence or absence of LIF (Table 2) and found that the presence of LIF, though not required, significantly enhanced the derivation efficiency of SOM-iPSCs. In contrast, derivation efficiency of SO-derived iPSCs was not affected by the presence of LIF. EGCs require LIF for their derivation, and yet are still derived at a much lower efficiency compared with SO-derived iPSCs and SOM-derived iPSCs (20 EGC colonies vs. >100 colonies from the preparation of PGCs), suggesting that LIF alone is not required for PGC reprogramming and reaffirming that the current culture methodologies for EGC derivation are suboptimal for PGC reprogramming.

Table 2.

Derivation of Human iPSCs from PGCs With and Without LIF

| No. of initial colonies | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cell Line | +LIF | −LIF |

| O-iPSCs | 0 | 0 |

| S-iPSCs | 10 | 2 |

| SO-iPSCs | 151 | 149 |

| SOM-iPSCs | 512 | 283a |

| EGCs | 7 | 1 |

Derivation efficiency in the presence (+LIF) or absence (−LIF) of LIF for O-iPSC, S-iPSC, SO-iPSCs, SOM-iPSCs, and EGCs. Ten days after transfection, 25,000 nontransfected PGCs and PGCs transfected with lentiviruses containing SOX2, OCT4, or C-MYC genes were plated onto 24-well tissue culture plates containing subconfluent MEF feeders in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 containing media supplemented with 10 ng/mL FGF2 with and without 1,000 units/mL human LIF. Colonies were counted on day 7. The presence of LIF significantly affected the derivation efficiency of the SOM-iPSC but did not increase the efficiency of the SO-iPSCs.

P < 0.05 between LIF treatments (t-test, n = 3 sublines per cell type were run in triplicate).

EGC, embryonic germ cell; FGF2, fibroblast growth factor-2; LIF, leukemia inhibitory factor; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast.

Microarray analysis

Microarray analyses performed on eight different cell lines demonstrated that the PGC-derived SO-iPSCs were more similar to ESCs than to EGCs in their gene expression profile. The hierarchical analysis of the top most differentially expressed genes in these cell lines revealed a similar pattern of gene expression among the SO-derived iPSC and ESCs, which is distinct from the similar pattern of PGCs and EGCs (Fig. 2B). Thus, PGCs and EGCs in many aspects resemble each other's mRNA profile despite a clear difference in their pluripotent properties and developmental potential. Furthermore, the scatter plot analysis shows that key pluripotency genes, including OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and C-MYC, were more similarly expressed between the SO-derived iPSCs and ESCs (Fig. 2C). Additionally, SO-derived iPSCs and ESCs expressed of other stem cell markers at similar levels, such as HMGA1, HELLS, and FOXD1, compared to PGCs and EGCs, supporting that SO-iPSCs express relevant, pluripotent-required ESC pathways.

Next, RT-PCR was performed to evaluate the levels of endogenous OCT4 and SOX2 mRNA expression in the SO- and SOM-derived iPSCs compared to nontransfected PGCs and ESCs (Fig. 2D). Endogenous expression was measured 10 weeks after transfection. Endogenous OCT4 and SOX2 were elevated in the SO-iPSCs compared with both the PGCs and ESCs. In addition, C-MYC was elevated in the SO-derived iPSCs compared with the nontransfected PGCs, suggesting that c-MYC is involved in the pluripotent state of these cells. We then performed qRT-PCR to elucidate expression differences specifically among pluripotent cells: SO-derived iPSCs, SOM-derived iPSCs, and ESCs (Fig. 2E). The levels of endogenous OCT4 and SOX2 mRNA were significantly lower in the ESCs compared with both SO- and SOM-derived iPSC lines. The mRNA expression levels of KLF4 and NANOG were similar in iPSCs and ESCs. Therefore, PGCs may already possess sufficient expression levels of endogenous KLF4 and NANOG transcripts to undergo reprogramming. Interestingly, the SO-derived iPSCs, which were transfected without cMYC, expressed higher endogenous levels of cMYC than the SOM-derived iPSCs. These results suggest that an optimal stoichiometric dosing of cMYC is required for efficient reprogramming, as the SOM-transduced lines resulted in a higher efficiency of derivation compared with that of SO-derived lines.

Protein expression analysis

An immunocytochemical analysis was performed to determine the expression of PSC marker proteins in the iPSCs. SO-derived iPSCs 10 weeks after viral transduction expressed PSC markers OCT4, SOX2, SSEA4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81, NANOG, and alkaline phosphatase (AP) (Fig. 2F), validating that the two-factor combination of SOX2 and OCT4 is sufficient to promote pluripotency in human PGCs in vitro. Importantly, we have previously reported that human PGCs, unlike PSCs, do not express the TRA antigens until they revert into EGCs. We show that the TRA antigens are also expressed in the iPSCs. In addition, SSEA1 is a marker that, like VASA, is expressed in human PGCs and EGCs but is not expressed by human ESCs. The iPSCs also expressed the markers VASA and DAZL. Thus, the expression of these markers along with SSEA1 in the iPSCs, suggest that some of the characteristics of their germ cell origin remain after reprogramming. Similar expression of these markers were also detected in PGC-iPSCs derived using an SeV-based vector approach (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fluorescence quantification (Fig. 2G) revealed that the majority of the PSC markers, including SOX2, OCT4, TRA-60, NANOG, KLF4, and C-MYC, were expressed at similar levels in the SO-iPSC and ESCs. In contrast, the EGCs expressed lesser amounts of these markers. The reduced levels in the EGCs, especially for OCT4 and SOX2, may be limiting factors in the pluripotent nature of human EGCs, which unlike mouse EGCs demonstrate limited developmental potential. For instance, human EGCs, unlike their mouse counterparts, are unable to form teratomas in vivo, even though they demonstrate the ability to derive cell types of all three germ layers in vitro.

Karyotyping

After 6 months, iPSCs lines derived after transduction with SOX2 and OCT4 expressed normal karyotypes (Supplementary Fig. S2). Previous studies have claimed chromosomal aberrations in human iPSC cultures occurring at relatively high frequencies that may be linked to tumorigenicity [54]. Here, we show that ∼20% of all lines derived were karyotypically abnormal. Although the efficiency of deriving iPSC lines from either male or female PGCs were similar, female-derived lines were two times more likely than male-derived lines to develop an abnormal karyotype (4 out of 10 lines in female SO-derived lines had karyotypic abnormalities compared to 2 out of the 10 ten male SO-derived iPSC lines). These lines were not analyzed for this study.

Differentiation potential and in vivo analysis

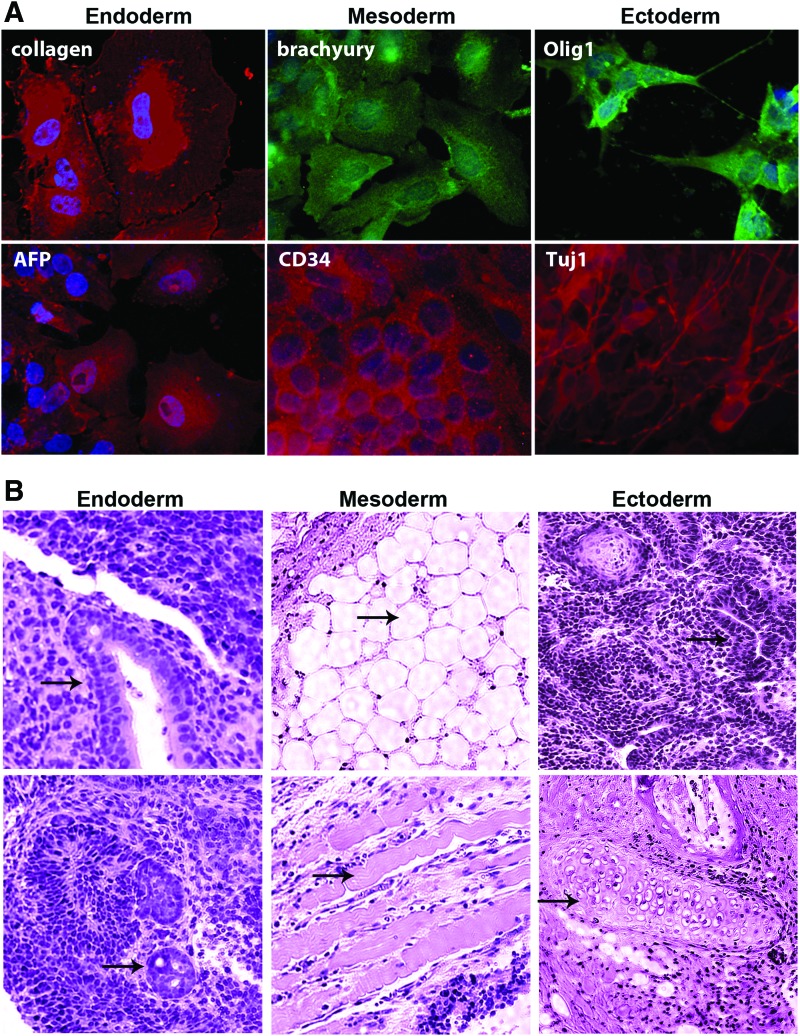

To determine the differentiation potential of the iPSCs, in vitro assays were performed. Immunocytochemical analyses were conducted using markers that distinguish the three germ layers after culturing in conditions that promote ectoderm, endoderm, or mesoderm development (Fig. 3A). The results showed that the iPSCs are capable of differentiating into Olig1+ and Tuj1+ neural cell subtypes, CD34+ and brachyury+ cells of the blood/cardiac or mesoderm lineage, and AFP+ and collagen+ endoderm-like cells. Controls included undifferentiated ESCs and treatment of samples with secondary antibody alone, which revealed either background or significantly lower levels of staining (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

(A) Immunocytochemical analysis confirming protein levels of markers that distinguish cell types of neuroectoderm, endoderm or mesoderm origins in SO-iPSCs. Differentiation was induced in undifferentiated iPSCs via embryoid bodies under conditions that promote differentiation of the specific germ layers. EBs were then disassociated in 1 mg/mL collagenase, plated on matrigel and stained. Under lineage-specific differentiation conditions, SO-iPSC colonies (passage 14/15) expressed collagen and AFP (endoderm), brachyury, and CD34 (mesoderm), and Olig1 and Tuj1 (ectoderm). Nuclei are stained with DAPI. (B) H&E staining of teratomas formed 8–12 weeks after intramuscular injection of 5 million SO-derived or SOM-derived iPSCs into the flanks of nonobese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficient (NOD-SCI) mice. Six inoculations of 5 million cells were performed for each line. PGCs that were expanded in culture and injected into mice did not form teratomas and ESCs served as positive controls. SO-iPSCs or SOM-iPSCs formed tumors in six of six cases and were similar in size to ESC controls (average tumor volume was 1.7 ± 0.3, 1.9 ± 0.4, 1.8 ± 0.4 cm3 for ESC, SO-iPSC, and SOM-iPSC, respectively). Representative images of tumors that developed cell types from all three germ layers are depicted (arrows). Endoderm: gut-like endodermal epithelium (left) and endodermal glandular epithelium (right); mesoderm: adipose tissue (left) and muscle (right); ectoderm: neural tube (left) and ectodermal squamous epithelium (right). No invasion into other organs such as the brain, liver, spleen, and lung were observed in any of the animals studied. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd

Finally, we investigated the in vivo developmental potential of the iPSCs. SO-iPSCs or SOM-iPSCs were implanted into mice, and no difference was observed in their ability to generate tumors. The iPSCs formed teratomas 8–12 weeks after intramuscular injection into NOD-SCI mice. Six inoculations of 5 million cells were performed for each line. In contrast, PGCs that were expanded in culture and injected into mice did not form teratomas. SO-iPSCs or SOM-iPSCs formed tumors in six out six cases and were similar size to ESCs controls (average tumor volume was 1.7 ± 0.3, 1.9 ± 0.4, 1.8 ± 0.4 cm3 for ESC, SO-iPSC, and SOM-iPSC, respectively). The teratomas derived from the iPSCs also contained tissues of all three germ layers, including gut tissue, neural tube adipose tissue, and muscle tissue (Fig. 3B). No invasion into other organs such as the brain, liver, spleen, and lung were observed. These results revealed that the iPSCs derived with OCT4 and SOX2 have multilineage potential in vivo.

Discussion

The popularity of iPSCs is rapidly growing throughout the scientific and medical community due to their highly promising applications in a number of therapies. As a result, efforts toward more efficiently deriving pluripotent cells are increasing. In this regard, identifying a reliable model for efficiently deriving stable iPSCs to critically study the programming factors and mechanisms that take place during and after reprogramming is essential for continued understanding of the complex cellular pathways. It is well known that many types of human somatic cells can give rise to iPSCs by introducing the reprogramming transcription factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and C-MYC [21,55] or OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and LIN28 [56]. Kim et al. first demonstrated that PSCs can be induced from neural progenitor cells with the use of only two of the reprogramming factors: exogenous OCT4 and either KLF4 or C-MYC [57]. Since then, other groups have also reported simplified reprogramming methods with other somatic cells, such as the conversion of human amnion-derived cells [58] and fetal hepatocytes [59] into iPSCs using only three reprogramming factors, OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG.

iPSCs were first derived from PGCs using in vitro culture conditions that mimicked embryonal carcinoma cells. The derivation of mouse EGCs was first reported in the early 1990s [5]. Later, Shamblott et al. successfully induced human EGCs to become pluripotent that were able to derive tissues of all three embryonic germ layers in vitro [29]. However, unlike mouse EGCs, human EGCs exhibit very low derivation efficiencies and are unstable under the current cell culture methods. More recently, PGCs have been induced to become pluripotent EGCs using small molecules TGFβR inhibitor and/or kempaullone [60]. However, the in vivo function of induced pluripotent EGCs has not been successfully demonstrated. Thus, to date, true human iPSCs, which can be defined as cells with the ability to form teratoma composed of all three germ layers in vivo, have never been derived from human PGCs. We show here, through extensive examination, that our reported human PGC-derived iPSCs are more phenotypically similar to ESCs than to EGCs, in particular due to their ability to generate teratomas in vivo.

Derivation of novel PGC-iPSCs using two factors

We show that human PGCs can be efficiently reprogrammed into human iPSCs via lentiviral transfection with only two factors, SOX2 and OCT4. The derivation efficiencies measured for nine combinations of factors (permutations of SOX2, OCT4, KLF4, and C-MYC) revealed that both OCT4 and SOX2 transcription factors are required to promote PGC conversion and that SOX2 (S) or OCT4 (O) alone were insufficient for generating iPSCs. This suggests that PGCs are deficient in their endogenous expression of both SOX2 and OCT4 for the induction of pluripotency, despite their elevated expression of endogenous OCT4. The PGCs transduced with only SOX2, and therefore relying on the endogenous supply of OCT4 to supplement the induction of pluripotency, generated a few colonies that appeared EGC-like but that did not survive more than 3 weeks in culture (data not shown). Others have reported similar results that iPSC colonies develop immediately after transduction with SOX2 but then die within weeks [34,61]. Importantly, we also demonstrate that PGC-iPSCs can be derived using the SeV nonintegrating approach. A comparison of SeV with other integrating methods has shown that this approach is a relatively simple, efficient method for deriving iPSCs from other cell sources with a complete absence of viral sequences at higher passages [62]. Here, we demonstrate for the first time the feasiblity of using SeV reprogramming to generate iPSCs from germ cells. As efficiency was lower than using lentivirus, it is of interest to optimize this protocol in future studies.

Although endogenous OCT4 was indeed measured in the PGCs, it was significantly lower than the endogenous expression of OCT4 in both ESCs and EGCs. Therefore, we hypothesize that the optimal stoichiometric dose of OCT4 for inducing pluripotency is higher than that which the cells endogenously express. The optimal stoichiometry dosing for generating iPSCs from murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) has been previously described [63], in which the authors suggest that high levels of OCT4 expression outweigh modest levels of SOX2 and KLF4 expression as the most critical factor for reprogramming and for achieving a stable pluripotent state. Although we did not study stoichiometry here, our results pertaining to PGCs parallel with this finding in that the addition of OCT4 was required to achieve pluripotency. One intriguing explanation to this finding pertains to the self-regulation of OCT4. Pan et al. discovered that when the expression level of OCT4 rises above a certain level, it represses its own promoter, thereby providing negative feedback for its own expression [64]. This negative feedback loop maintains the steady state expression of OCT4, thus maintaining the cell's ES-like undifferentiated state [50]. This finding could partially explain why erring on the side of higher OCT4 doses, such as in the present study for transfection combinations that included OCT4, yielded PGC to iPSC conversion—striking the correct balance of OCT4 and SOX2 expression in PGCs to sufficiently activate the required pluripotent genes for reprogramming. This is supported by the fact that more than half of the genes bound by OCT4 are also bound by SOX2 suggesting that differences in OCT4 and SOX2 levels must coordinate to control gene transcription [65].

Recent literature strongly suggests that the stoichiometry OCT4 expression may be the critical contributing factor for efficient human iPSC induction from somatic cells. Using human fibroblasts, Sadelain and colleagues defined the optimal stoichiometry of reprogramming factor expression to be highly sensitive to OCT4 dosage and demonstrated the impact that variations in the relative ratios of reprogramming factor expression exert on iPSC induction efficiency [66]. Likewise, our results show that endogenous levels of OCT4 are not sufficient for the efficient reprogramming of human PGCs.

OCT4 is a member of the POU family of transcription factors that is essential for pluripotency and successful reprogramming. For this process, not only does OCT4 control transcriptional machinery, but OCT4 also acts as a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein. For example, OCT4-mutant ESCs with altered nuclear import/export activity display limited potential for cellular reprogramming, suggesting a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling role of OCT4 in somatic cell reprogramming [67]. In mature human oocytes, OCT4 is expressed in the cytoplasm throughout the cleavage stage before compaction, after which OCT4 can be detected in the nucleus throughout the blastocyst and in PGCs at the time of their development in the early fetus [68]. OCT4 expression has also been reported in the adult male testis in the cytoplasm of dark spermatogonial stem cells, which proliferate and initiate lineage-specific differentiation [69]. However, we did not detect differences in the localization of OCT4 staining in the PGCs compared to the PSCs, including iPS-PGCs. This is consistent with other studies that have reported robust nuclear staining of OCT4 in human PGCs and oogonia [36,70]. Nonetheless, future studies should be conducted to determine whether small differences remain in the OCT4 distribution in PGCs and to determine whether PSCs play a role in OCT4 shuttling during PGC reprogramming.

A striking result identified here was the lower reprogramming efficiency of SOK-iPSCs compared to SO-iPSCs, suggesting that KLF4 may impair PGC reprogramming or that KLF4 may require a stringent stoichiometry that was not achieved in the dosage used here. In germ cells, KLF4 is a known differentiation factor. Therefore, overexpression of KLF4 in human germ cells that already express sufficient levels of KLF4 could limit the dedifferentiation of the PGCs into iPSCs or possibly preserve their germ cell identity. Conversely, direct interaction of KLF4 with OCT4 and SOX2 has been suggested as a critical step in somatic cell reprograming to iPSCs [71], and these interactions induce the expression of NANOG [72,73]; how excess amounts of KLF4 affect these interactions remains unknown. Thus, understanding reprogramming factor stoichiometry of KLF4 on PGC reprogramming is an exciting topic that requires future studies to elucidate the role of KLF4 in germ cell pluripotency and the stoichiometric requirements of factor expression during iPSC induction.

Interestingly, we also found that the addition of C-MYC increased reprogramming efficiency. Several roles of C-MYC have been suggested regarding its ability to enhance cellular reprogramming, such as its role in directly activating pluripotent marker genes [74,75] and in promoting the cell cycle via activation of p53 and p21 pathways [76]. Of note, although the reprogramming efficiency was increased in the SOM PGC-iPSCs, the efficiency and proliferation rates of sub-passaging among the SO- and SOM-derived PGC-iPSC lines were similar. These results suggest that MYC did not affect the cell cycle, although further studies are warranted. Another possible reason that MYC increased efficiency of PGC-iPSC is its demonstrated ability to loosen the chromatin structure, which could facilitate the access of other reprogramming factors to their targeted sequences [76], and this may or may not be related to the ability MYC has to inhibit differentiation of PSCs. For example, both C-MYC and N-MYC inhibit the differentiation of mouse ESCs toward the primitive endoderm lineage through the suppression of Gata-6 expression, the master gene [77]. Thus, MYC may play a role in PGC reprogramming by inhibiting differentiation. This possibility is supported by studies that show MYC promotes a more stable pluripotent state with more efficient germline transmission in chimeric mice from iPSCs [74]. Therefore, it is of great interest to determine the role of C-MYC in the reprogramming process in future studies.

As previously discussed, several of the genes expressed in PGCs, such as OCT4, NANOG, and LIN28, are also involved in the somatic cell reprogramming process [56]. Interestingly, Nagamatsu et al. showed that factors that are exclusively expressed by PGCs, such as BLIMP1, PRDM14, and PRMT5, also facilitate somatic cell reprogramming into PSCs [78]. Combinations of BLIMP1, PRDM14, and PRMT5, along with KLF4 and OCT4 induced the generation of iPSC or iPSC-like colonies from fibroblasts. Therefore, as these factors are unique to PGCs, our PGC model for inducing pluripotency described here may be useful for identifying additional factors and mechanisms that could yield even greater efficiency and/or better pluripotency of reprogrammed somatic cells in the future.

We also found that the reprogramming of PGCs does not require LIF for conversion to iPSCs. Although LIF has been shown to facilitate the naïve state of human PSCs, it was not required for either the derivation or maintenance of SO-iPSCs pluripotency, and there was no significant difference in the derivation efficiencies of iPSCs using the SO factors in the presence or absence of LIF. However, the derivation efficiency was significantly increased for SOM-iPSCs in the presence of LIF. These results suggest a cooperative interaction between C-MYC and LIF for inducing human pluripotency. Recent findings generating mouse iPSCs have shown that LIF is responsible for activating AP through C-MYC-dependent mechanisms. This report suggested that LIF functions through C-MYC as a protective factor during the transition from AP-positive colonies to bona fide iPSC cells [79]. Therefore, it may be that the combinatory effect of LIF and overexpressed C-MYC in human PGC-iPSCs promotes more stable colonies during their transition from PGCs to iPSCs. Although human ESCs and iPSCs do not require LIF for their maintenance, it has been shown that LIF can improve iPSC production and enhance the derivation of human ESCs [51,52,80,81]. Therefore, a similar mechanism may be occurring in the PGCs by which LIF and C-MYC together improve iPSC generation efficiency.

PGC-iPSC germ cell phenotype

PGC-iPSCs were found to express SSEA1, similar to EGCs. This finding is not surprising given that iPSCs have been reported by many to retain many epigenetic signatures of their cell of origins [82]. These epigenetic differences are unlikely to be essential features of iPSCs, but rather reflect stochastic variations associated with the technical challenges and passage dependence of achieving complete reprogramming. Therefore, although our PGC-iPSCs expressed the germ cell marker SSEA1, they satisfied the most stringent criteria of pluripotency by forming teratomas, differentiating into representative cell types from all three germ layers in vitro and surviving passages after 6 months in cell culture, a time after which partially reprogrammed cells do not survive or do not maintain pluripotency.

In fact, SSEA1 is expressed in all mouse PSCs, whereas in human cells, it has been reported to be expressed in EGCs and in partially reprogrammed iPSCs [20]. Buecker et al. showed that hLR5-derived human iPSCs, which are dependent on the constitutive ectopic expression of five reprogramming factors OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, C-MYC, and NANOG, demonstrated clonal-like efficiencies and expressed SSEA1 but did not express the other PSC factors. In addition, other studies have shown that SSEA1 is expressed early in the process of deriving mouse iPSCs, before complete reprogramming takes place [22,83]. Specifically, the use of LIF to derive hLR5 was shown to contribute to SSEA1 expression by activating the JAK/STAT pathway. Upon withdrawal of LIF, hLR5 pluripotency was lost and colony phenotype was dramatically changed. Therefore, it was concluded that hLR5 cells were dependent on LIF and that the combination of LIF and SSEA1 expression is characteristic of mouse ESCs or partially reprogrammed human iPSCs. In contrast to hLR5 cells, which are unstable iPSCs and lose their pluripotent integrity upon LIF removal, we show human PGC-iPSCs that express SSEA1 in addition to other pluripotent markers, SSEA4 and TRA antigens even after LIF removal.

Therefore, it is possible that the expression of SSEA1 marks the clonal phenotype of a mouse ESC-like state. However, its relationship to the ground state of PSCs remains unknown. Although it is known that SSEA1 is expressed by human EGCs, studies describing the derivation of human GSCs [25,28] have not reported whether human GSCs express SSEA1, and there is no report that human iPSCs express SSEA1 without LIF dependence. Therefore, it is unclear whether SSEA1 is (i) a remnant of the germ cell identity that is retained in a PSC, (ii) a marker of the mouse naïve state in human iPSCs, or (iii) a marker of partially reprogrammed cells in human iPSCs. Understanding the origin and role of SSEA1 in reprogrammed PGCs is an important area for investigating the factors regulating germ cell pluripotency in future studies.

Finally, although the PGC-derived iPSC colonies exhibited rounded morphologies similar to EGCs, their genetic and protein makeup were more similar to human ESCs. The PGC-derived iPSCs were also more robust to cell culture passages, as ESCs and iPSCs, and they exhibited increased survivability compared to human EGCs. Multiple lines were established, which were karyotypically stable after 20 subcultures. Interestingly, female lines were more likely to become unstable than male lines, consistent with a recent report describing instability of X inactivation in female iPSC lines that were derived from somatic cells [84].

The PGC-derived iPSCs reliably expressed characteristic markers of pluripotent cells, including OCT4, SOX2, SSEA4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1-81, NANOG, and AP. They remained stable over long-term culture, whereas EGCs have been shown to lose their markers of pluripotency and to spontaneously differentiate [30]. Because spontaneous differentiation and poor expansion of EGCs are the two primary complications that commonly arise when culturing these cells [30], our PGC-derived iPSCs represent a highly attractive alternative for studying germ cell reprogramming and pluripotency.

Conclusions

The derivation and maintenance of the two factor SO-iPSCs significantly supersedes that of EGCs in culture. PGC-derived iPSCs therefore provide a powerful model for studying factors regulating germ cell pluripotency and reprogramming. Furthermore, by reprogramming human PGCs into iPSCs using only two factors, pathways involved in this dedifferentiating process can be studied in a more simplified manner. For instance, upregulated expression of C-MYC or KLF4 is known to induce many mechanisms unrelated to pluripotency. Therefore, the ability to generate iPSCs using only OCT4 and SOX2 provides a “reductionist” platform to study how these factors facilitate reprogramming. This simple induction platform combined with the benefits of PGC-derived stem cells identified here, including increased pluripotency, the ability to produce in vivo teratomas, and the capacity for extensive passaging, create a new powerful model for studying reprogramming mechanisms that has never been reported. For example, although it is known that SOX2 and OCT4 cooperatively interact to promote the expression of other pluripotent-related factors such as NANOG [85], ZFP206 [86], and LIN28 [87], the pathways involved in these processes remain unclear, and this model provides a pathway for elucidating such processes.

Thus, our report demonstrates a novel model of deriving robustly efficient iPSCs from human PGCs without the ectopic expression of C-MYC, KLF4, or other small molecules. We show that germ cells can generate iPSCs at efficiencies that allow germ cell reprogramming to be studied. Our simple model eliminates the confounding effects of small molecules while providing unparalleled benefits for studying the pathways involved in reprogramming pathways. Human PGCs can be invaluable for investigating human iPSC reprogramming and a potential source of cells for studying early germ cell biology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was graciously supported by NICHD R21 HD057487 (C.L.K.), Maryland Stem Cell Research Funds 2007-MSCRFE-0210-01 (C.L.K.), and by 2008-MSCRFE-0129-00 (C.L.K.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Seki Y, Hayashi K, Itoh K, Mizugaki M, Saitou M. and Matsui Y. (2005). Extensive and orderly reprogramming of genome-wide chromatin modifications associated with specification and early development of germ cells in mice. Dev Biol 278:440–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gkountela S, Li Z, Vincent JJ, Zhang KX, Chen A, Pellegrini M. and Clark AT. (2012). The ontogeny of cKIT(+) human primordial germ cells proves to be a resource for human germ line reprogramming, imprint erasure and in vitro differentiation. Nat Cell Biol 15:113–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajkova P, Ancelin K, Waldmann T, Lacoste N, Lange UC, Cesari F, Lee C, Almouzni G, Schneider R. and Surani MA. (2008). Chromatin dynamics during epigenetic reprogramming in the mouse germ line. Nature 452:877–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popp C, Dean W, Feng S, Cokus SJ, Andrews S, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE. and Reik W. (2010). Genome-wide erasure of DNA methylation in mouse primordial germ cells is affected by AID deficiency. Nature 463:1101–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urven L, Weng D, Schumaker A, Gearhart J. and McCarrey J. (1993). Differential gene expression in fetal mouse germ cells. Biol Reprod 48:564–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donovan PJ. and de Miguel MP. (2003). Turning germ cells into stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev 13:463–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gearhart J. (1998). New potential for human embryonic stem cells. Science 282:1061–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomson JA. and Odorico JS. (2000). Human embryonic stem cell and embryonic germ cell lines. Trends Biotechnol 18:53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Swelstad BB. and Candace LK. (2009). Current protocols in the generation of pluripotent stem cells: theoretical methodological and clinical considerations. Stem Cell Cloning 2010:13–27 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Miguel MP, Arnalich Montiel F, Lopez Iglesias P, Blazquez Martinez A. and Nistal M. (2009). Epiblast-derived stem cells in embryonic and adult tissues. Int J Dev Biol 53:1529–1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr CL, Shamblott MJ. and Gearhart JD. (2006). Pluripotent stem cells from germ cells. Methods Enzymol 419:400–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byrne JA, Nguyen HN. and Reijo Pera RA. (2009). Enhanced generation of induced pluripotent stem cells from a subpopulation of human fibroblasts. PLoS One 4:e7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stadtfeld M, Maherali N, Borkent M. and Hochedlinger K. (2010). A reprogrammable mouse strain from gene-targeted embryonic stem cells. Nat Methods 7:53–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resnick JL, Bixler LS, Cheng L. and Donovan PJ. (1992). Long-term proliferation of mouse primordial germ cells in culture. Nature 359:550–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durcova-Hills G, Ainscough J. and McLaren A. (2001). Pluripotential stem cells derived from migrating primordial germ cells. Differentiation 68:220–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeom YI, Fuhrmann G, Ovitt CE, Brehm A, Ohbo K, Gross M, Hubner K. and Scholer H. (1996). Germline regulatory element of Oct-4 specific for the totipotent cycle of embryonal cells. Development 122:881–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durcova-Hills G, Adams IR, Barton SC, Surani MA. and McLaren A. (2006). The role of exogenous fibroblast growth factor-2 on the reprogramming of primordial germ cells into pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 24:1441–1449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Na J, Plews J, Li J, Wongtrakoongate P, Tuuri T, Feki A, Andrews PW. and Unger C. (2010). Molecular mechanisms of pluripotency and reprogramming. Stem Cell Res Ther 1:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kerr CL. and Cheng L. (2010). Multiple, interconvertible states of human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6:497–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buecker C, Chen HH, Polo JM, Daheron L, Bu L, Barakat TS, Okwieka P, Porter A, Gribnau J, Hochedlinger K. and Geijsen N. (2010). A murine ESC-like state facilitates transgenesis and homologous recombination in human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6:535–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamanaka S. and Takahashi K. (2006). [Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse fibroblast cultures]. Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso 51:2346–2351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brambrink T, Foreman R, Welstead GG, Lengner CJ, Wernig M, Suh H. and Jaenisch R. (2008). Sequential expression of pluripotency markers during direct reprogramming of mouse somatic cells. Cell Stem Cell 2:151–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaerkady R, Kerr CL, Kandasamy K, Marimuthu A, Gearhart JD. and Pandey A. (2010). Comparative proteomics of human embryonic stem cells and embryonal carcinoma cells. Proteomics 10:1359–1373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sutiwisesak R, Kitiyanant N, Kotchabhakdi N, Felsenfeld G, Andrews PW. and Wongtrakoongate P. (2014). Induced pluripotency enables differentiation of human nullipotent embryonal carcinoma cells N2102Ep. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:2611–2619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kossack N, Meneses J, Shefi S, Nguyen HN, Chavez S, Nicholas C, Gromoll J, Turek PJ. and Reijo-Pera RA. (2009). Isolation and characterization of pluripotent human spermatogonial stem cell-derived cells. Stem Cells 27:138–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guan K, Nayernia K, Maier LS, Wagner S, Dressel R, Lee JH, Nolte J, Wolf F, Li M, Engel W. and Hasenfuss G. (2006). Pluripotency of spermatogonial stem cells from adult mouse testis. Nature 440:1199–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Inoue K, Lee J, Yoshimoto M, Ogonuki N, Miki H, Baba S, Kato T, Kazuki Y, et al. (2004). Generation of pluripotent stem cells from neonatal mouse testis. Cell 119:1001–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conrad S, Renninger M, Hennenlotter J, Wiesner T, Just L, Bonin M, Aicher W, Buhring HJ, Mattheus U, et al. (2008). Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult human testis. Nature 456:344–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shamblott MJ, Axelman J, Wang S, Bugg EM, Littlefield JW, Donovan PJ, Blumenthal PD, Huggins GR. and Gearhart JD. (1998). Derivation of pluripotent stem cells from cultured human primordial germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:13726–13731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turnpenny L, Brickwood S, Spalluto CM, Piper K, Cameron IT, Wilson DI. and Hanley NA. (2003). Derivation of human embryonic germ cells: an alternative source of pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 21:598–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pashai N, Hao H, All A, Gupta S, Chaerkady R, De Los Angeles A, Gearhart JD. and Kerr CL. (2012). Genome-wide profiling of pluripotent cells reveals a unique molecular signature of human embryonic germ cells. PLoS One 7:e39088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saitou M, Kagiwada S. and Kurimoto K. (2012). Epigenetic reprogramming in mouse pre-implantation development and primordial germ cells. Development 139:15–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onyango P, Jiang S, Uejima H, Shamblott MJ, Gearhart JD, Cui H. and Feinberg AP. (2002). Monoallelic expression and methylation of imprinted genes in human and mouse embryonic germ cell lineages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:10599–10604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daley GQ. (2007). Towards the generation of patient-specific pluripotent stem cells for combined gene and cell therapy of hematologic disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program:17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fusaki N, Ban H, Nishiyama A, Saeki K. and Hasegawa M. (2009). Efficient induction of transgene-free human pluripotent stem cells using a vector based on Sendai virus, an RNA virus that does not integrate into the host genome. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 85:348–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerr CL, Hill CM, Blumenthal PD. and Gearhart JD. (2008). Expression of pluripotent stem cell markers in the human fetal ovary. Hum Reprod 23:589–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerr CL, Hill CM, Blumenthal PD. and Gearhart JD. (2008). Expression of pluripotent stem cell markers in the human fetal testis. Stem Cells 26:412–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hiller M, Liu C, Blumenthal P, Gearhart J. and Kerr C. (2011). Bone morphogenetic protein 4 mediates human embryonic germ cell derivation. Stem Cells Dev 20:351–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerr CL, Gearhart JD, Elliott AM. and Donovan PJ. (2006). Embryonic germ cells: when germ cells become stem cells. Semin Reprod Med 24:304–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moisan AE, Foster RA, Betteridge KJ. and Hahnel AC. (2003). Dose-response of RAG2-/-/gammac-/- mice to busulfan in preparation for spermatogonial transplantation. Reproduction 126:205–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dowey SN, Huang X, Chou BK, Ye Z. and Cheng L. (2012). Generation of integration-free human induced pluripotent stem cells from postnatal blood mononuclear cells by plasmid vector expression. Nat Protoc 7:2013–2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mali P, Chou BK, Yen J, Ye Z, Zou J, Dowey S, Brodsky RA, Ohm JE, Yu W, et al. (2010). Butyrate greatly enhances derivation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by promoting epigenetic remodeling and the expression of pluripotency-associated genes. Stem Cells 28:713–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chou BK, Mali P, Huang X, Ye Z, Dowey SN, Resar LM, Zou C, Zhang YA, Tong J. and Cheng L. (2011). Efficient human iPS cell derivation by a non-integrating plasmid from blood cells with unique epigenetic and gene expression signatures. Cell Res 21:518–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan EM, Ratanasirintrawoot S, Park IH, Manos PD, Loh YH, Huo H, Miller JD, Hartung O, Rho J, et al. (2009). Live cell imaging distinguishes bona fide human iPS cells from partially reprogrammed cells. Nat Biotechnol 27:1033–1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lieu PT, Fontes A, Vemuri MC. and MacArthur CC. (2013). Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells with CytoTune, a non-integrating Sendai virus. Methods Mol Biol 997:45–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacArthur CC, Fontes A, Ravinder N, Kuninger D, Kaur J, Bailey M, Taliana A, Vemuri MC. and Lieu PT. (2012). Generation of human-induced pluripotent stem cells by a nonintegrating RNA Sendai virus vector in feeder-free or xeno-free conditions. Stem Cells Int 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manos PD, Ratanasirintrawoot S, Loewer S, Daley GQ. and Schlaeger TM. (2011). Live-cell immunofluorescence staining of human pluripotent stem cells. Curr Protoc Stem Cell Biol Chapter 1:Unit1C.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, Beazer-Barclay YD, Antonellis KJ, Scherf U. and Speed TP. (2003). Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4:249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen G, Ye Z, Yu X, Zou J, Mali P, Brodsky RA. and Cheng L. (2008). Trophoblast differentiation defect in human embryonic stem cells lacking PIG-A and GPI-anchored cell-surface proteins. Cell Stem Cell 2:345–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pan G. and Thomson JA. (2007). Nanog and transcriptional networks in embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Cell Res 17:42–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perrett RM, Turnpenny L, Eckert JJ, O'Shea M, Sonne SB, Cameron IT, Wilson DI, Rajpert-De Meyts E. and Hanley NA. (2008). The early human germ cell lineage does not express SOX2 during in vivo development or upon in vitro culture. Biol Reprod 78:852–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanna J, Cheng AW, Saha K, Kim J, Lengner CJ, Soldner F, Cassady JP, Muffat J, Carey BW. and Jaenisch R. (2010). Human embryonic stem cells with biological and epigenetic characteristics similar to those of mouse ESCs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:9222–9227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oue M, Handa H, Matsuzaki Y, Suzue K, Murakami H. and Hirai H. (2012). The murine stem cell virus promoter drives correlated transgene expression in the leukocytes and cerebellar purkinje cells of transgenic mice. PLoS One 7:e51015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohm JE, Mali P, Van Neste L, Berman DM, Liang L, Pandiyan K, Briggs KJ, Zhang W, Argani P, et al. (2010). Cancer-related epigenome changes associated with reprogramming to induced pluripotent stem cells. Cancer Res 70:7662–7673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park I-H, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA, Lerou PH, Lensch MW. and Daley GQ. (2007). Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature 451:141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, Nie J, Jonsdottir GA, Ruotti V, et al. (2007). Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318:1917–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim JB, Zaehres H, Wu G, Gentile L, Ko K, Sebastiano V, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Ruau D, Han DW, Zenke M. and Scholer HR. (2008). Pluripotent stem cells induced from adult neural stem cells by reprogramming with two factors. Nature 454:646–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao H-x, Li Y, Jin H-f, Xie L, Liu C, Jiang F, Luo Y-n, Yin G-w, Li Y. and Wang J. (2010). Rapid and efficient reprogramming of human amnion-derived cells into pluripotency by three factors OCT4/SOX2/NANOG. Differentiation 80:123–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hansel MC, Gramignoli R, Blake W, Davila J, Skvorak K, Dorko K, Tahan V, Lee BR, Tafaleng E. and Guzman-Lepe J. (2014). Increased reprogramming of human fetal hepatocytes compared with adult hepatocytes in feeder-free conditions. Cell Transplant 23:27–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kimura T, Kaga Y, Sekita Y, Fujikawa K, Nakatani T, Odamoto M, Funaki S, Ikawa M, Abe K. and Nakano T. (2015). Pluripotent stem cells derived from mouse primordial germ cells by small molecule compounds. Stem Cells 33:45–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng AM, Byrom MW, Shelton J. and Ford LP. (2005). Antisense inhibition of human miRNAs and indications for an involvement of miRNA in cell growth and apoptosis. Nucleic Acids Res 33:1290–1297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schlaeger TM, Daheron L, Brickler TR, Entwisle S, Chan K, Cianci A, DeVine A, Ettenger A, Fitzgerald K. and Godfrey M. (2014). A comparison of non-integrating reprogramming methods. Nat Biotechnol 33:58–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tiemann U, Sgodda M, Warlich E, Ballmaier M, Scholer HR, Schambach A. and Cantz T. (2011). Optimal reprogramming factor stoichiometry increases colony numbers and affects molecular characteristics of murine induced pluripotent stem cells. Cytometry A 79:426–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pan G, Li J, Zhou Y, Zheng H. and Pei D. (2006). A negative feedback loop of transcription factors that controls stem cell pluripotency and self-renewal. FASEB J 20:1730–1732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL. and Jenner RG. (2005). Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 122:947–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Papapetrou EP, Tomishima MJ, Chambers SM, Mica Y, Reed E, Menon J, Tabar V, Mo Q, Studer L. and Sadelain M. (2009). Stoichiometric and temporal requirements of Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc expression for efficient human iPSC induction and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:12759–12764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oka M, Moriyama T, Asally M, Kawakami K. and Yoneda Y. (2013). Differential role for transcription factor Oct4 nucleocytoplasmic dynamics in somatic cell reprogramming and self-renewal of embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem 288:15085–15097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cauffman G, Van de Velde H, Liebaers I. and Van Steirteghem A. (2004). Oct-4 mRNA and protein expression during human preimplantation development. Mol Hum Reprod 11:173–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bhartiya D, Kasiviswanathan S, Unni SK, Pethe P, Dhabalia JV, Patwardhan S. and Tongaonkar HB. (2010). Newer insights into premeiotic development of germ cells in adult human testis using Oct-4 as a stem cell marker. J Histochem Cytochem 58:1093–1106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Byskov A, Høyer P, Andersen CY, Kristensen S, Jespersen A. and Møllgård K. (2011). No evidence for the presence of oogonia in the human ovary after their final clearance during the first two years of life. Hum Reprod 26:2129–2139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wei Z, Yang Y, Zhang P, Andrianakos R, Hasegawa K, Lyu J, Chen X, Bai G, Liu C, Pera M. and Lu W. (2009). Klf4 interacts directly with Oct4 and Sox2 to promote reprogramming. Stem Cells 27:2969–2978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chan KK, Zhang J, Chia NY, Chan YS, Sim HS, Tan KS, Oh SK, Ng HH. and Choo AB. (2009). KLF4 and PBX1 directly regulate NANOG expression in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 27:2114–2125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang P, Andrianakos R, Yang Y, Liu C. and Lu W. (2010). Kruppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) prevents embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation by regulating Nanog gene expression. J Biol Chem 285:9180–9189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nakagawa M, Takizawa N, Narita M, Ichisaka T. and Yamanaka S. (2010). Promotion of direct reprogramming by transformation-deficient Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:14152–14157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cartwright P, McLean C, Sheppard A, Rivett D, Jones K. and Dalton S. (2005). LIF/STAT3 controls ES cell self-renewal and pluripotency by a Myc-dependent mechanism. Development 132:885–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Okita K, Matsumura Y, Sato Y, Okada A, Morizane A, Okamoto S, Hong H, Nakagawa M, Tanabe K. and Tezuka K-i. (2011). A more efficient method to generate integration-free human iPS cells. Nat Methods 8:409–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Smith KN, Singh AM. and Dalton S. (2010). Myc represses primitive endoderm differentiation in pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 7:343–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nagamatsu G, Kosaka T, Kawasumi M, Kinoshita T, Takubo K, Akiyama H, Sudo T, Kobayashi T, Oya M. and Suda T. (2011). A germ cell-specific gene, Prmt5, works in somatic cell reprogramming. J Biol Chem 286:10641–10648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu J, Wang F, Tang Z, Zhan Y, Zhang J, Yan Q, Xiong Y, Xie X, Wu J. and Zhang S. (2010). Role of leukaemia inhibitory factor in the induction of pluripotent stem cells in mice. Cell Biol Int 34:791–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]